Abstract

This article assesses how strategies applied by Cambodian NGOs to reduce their dependence on external resources affect the sustainability of their mission, program and funding. At the empirical level, the findings suggest that NGO dependence on foreign aid has mixed effects on the organizations such as unpredictability of funding, goal displacement, reduced organizational autonomy, and top-down accountability. Funding from commercial activities is more predictable and potentially promotes bottom-up accountability and increases organizational autonomy but may conflict with the mission-drift of NGOs. At the theoretical level, this article contributes to resource dependence theory by introducing a perspective from developing countries, which implies large power differentials between international funding agencies and receiving local NGOs. The strategic responses employed by local NGO leaders to reduce external resource dependence entail a paradigm shift from external control to local embeddedness and increased autonomy. The findings have important policy implications regarding the regulation of NGO-related and unrelated business activities.

Résumé

Cet article évalue comment les stratégies mises en œuvre par les ONG cambodgiennes pour réduire leur dépendance aux ressources externes influent sur la pérennité de leur mission, de leur programme et de leur financement. D’un point de vue empirique, nos résultats suggèrent que la dépendance à l’aide étrangère des ONG a divers effets sur ces organisations, comme l’imprévisibilité du financement, la dérive des objectifs, la diminution de l’autonomie organisationnelle et l’apparition d’un système de responsabilité descendante. Le financement par l’activité commerciale est plus prévisible, promeut potentiellement un système de responsabilité ascendante et accroît l’autonomie organisationnelle, mais peut éloigner les ONG de leur mission. D’un point de vue théorique, cet article contribue à la théorie de la dépendance aux ressources (TDR) en introduisant la perspective des pays en voie de développement, qui suppose d’importantes différences de pouvoir entre les organismes de financement et les ONG locales bénéficiaires. Les réponses stratégiques employées par les responsables des NGO locales pour réduire leur dépendance aux ressources externes impliquent un changement de paradigme, le contrôle externe devant céder face à son intégration locale et à une autonomie accrue. Ces résultats ont d’importantes conséquences politiques en termes de réglementation des activités commerciales liées ou non aux ONG.

Zusammenfassung

Dieser Beitrag untersucht, wie sich die Strategien nicht-staatlicher Organisationen in Kambodscha zur Verringerung ihrer Abhängigkeit von externen Ressourcen auf die Nachhaltigkeit ihrer Mission, ihres Programms und ihrer Finanzierung auswirken. Auf empirischer Ebene weisen die Ergebnisse darauf hin, dass die Abhängigkeit der nicht-staatlichen Organisationen von ausländischen Hilfeleistungen diverse Auswirkungen auf die Organisationen haben, zum Beispiel die Unberechenbarkeit der Finanzierung, eine Zielverlagerung, eine geringere organisationale Autonomie und eine Rechenschaft nach dem Top-Down-Prinzip. Eine Finanzierung durch wirtschaftliche Aktivitäten ist berechenbarer, fördert möglicherweise eine Rechenschaft nach dem Bottom-Up-Prinzip und erhöht die organisationale Autonomie, kann jedoch im Konflikt mit dem Abdriften der Mission nicht-staatlicher Organisationen stehen. Auf theoretischer Ebene leistet diese Abhandlung einen Beitrag zur Ressourcenabhängigkeitstheorie, indem eine Perspektive der Entwicklungsländer vorgestellt wird, die große Machtunterschiede zwischen den internationalen Förderorganisationen und den lokalen nicht-staatlichen Organisationen als Mittelempfänger impliziert. Die strategischen Antworten der Führungskräfte lokaler nicht-staatlicher Organisationen zur Reduzierung der Abhängigkeit von externen Ressourcen beinhalten einen Paradigmawechsel von der externen Kontrolle zu lokaler Einbindung und erhöhter Autonomie. Die Ergebnisse haben wichtige politische Implikationen für die Regulierung der mit den nicht-staatlichen Organisationen verbundenen und unverbundenen Geschäftstätigkeiten.

Resumen

El presente artículo evalúa cómo las estrategias aplicadas por las ONG camboyanas para reducir su dependencia de los recursos externos afectan la sostenibilidad de su misión, su programa y su financiación. A nivel empírico, las hallazgos sugieren que la dependencia por parte de las ONG de la ayuda extranjera tiene efectos contradictorios en las organizaciones, tales como la impredecibilidad de la financiación, el desplazamiento de la meta, una autonomía organizativa reducida y una rendición de cuentas de arriba a abajo. La financiación de las actividades comerciales es más predecible y fomenta potencialmente la rendición de cuentas de abajo a arriba y aumenta la autonomía organizativa pero puede entrar en conflicto con la desviación de la misión de las ONG. A nivel teórico, el presente artículo contribuye a la teoría de la dependencia de recursos (RDT, del inglés resource dependence theory) mediante la introducción de una perspectiva desde los países en vías de desarrollo, lo que implica grandes diferenciales de poder entre las agencias de financiación extranjeras y las ONG receptoras locales. Las respuestas estratégicas empleadas por los líderes de las ONG locales para reducir la dependencia de recursos externos conlleva un cambio de paradigma desde el control externo al arraigo social y a un incremento de la autonomía. Los hallazgos tienen implicaciones políticas importantes con respecto a la reglamentación de las actividades comerciales relacionadas y no relacionadas con las ONG.

Chinese

本文对以下课题进行评估:柬埔寨非政府组织(NGO)所应用的旨在减轻其对外部资源的依赖性的策略是如何影响其使命、项目与资助的可持续性的。在实证层面上,我们的研究发现非政府组织对外界援助的依赖性对该种组织有多面的影响,比如资助的不可预知性、目标的移转、组织自治度的降低、自上而下的问责等。来自商业活动的资助的可预知性较高,有促进自下而上的问责的潜力,可增强组织自治权,但却与非政府组织的使命漂移(mission-drift)相冲突。从理论层面上看,本文从发展中国家角度进行介绍,这意味着国际基金资助机构与作为接收方的地方非政府组织之间的巨大权力差异,从而丰富了资源依赖理论(RDT)。地方非政府机构领导为了降低对外部资源的依赖性而所采取的策略性回应措施,导致了思维模式的转移,即从外部控制向本地嵌入(local embeddedness)和加强自治权转移。对于与非政府机构相关的或不相关的商业活动,本研究的结构均具有重要的政策含义。

Arabic

تقوم هذه المقالة بتقييم كيف أن الإستراتيجيات التي تطبقها المنظمات الغير حكومية (NGOs) الكمبودية لتقليل إعتمادها على الموارد الخارجية تؤثر على إستدامة مهمتهم ٬البرامج و التمويل.على المستوى العملي ، تشير النتائج إلى أن إعتماد المنظمات الغير حكومية (NGO) على المساعدات الخارجية له تأثيرات متفاوتة على المنظمات مثل عدم القدرة على التنبؤ بالتمويل، هدف التهجير ، خفض الحكم الذاتي التنظيمي ، و المساءلة الإدارية من أعلى إلى أسفل. التمويل من الأنشطة التجارية أكثر قابلية للتنبؤ وربما يعززالمساءلة من أسفل إلى أعلى ويزيد الإستقلالية التنظيمية ولكن قد تتعارض مع حركة بعثة المنظمات الغير حكومية (NGO). على المستوى النظري ، تسهم هذه المقالة في نظرية تبعية الموارد (RDT) عن طريق إدخال منظور من البلدان النامية ، مما يعني فروق في السلطة كبير بين وكالات التمويل الدولية و المنظمات الغير حكومية (NGO) المحلية التي تحصل على التمويل. ردود الإستراتيجية التي إستخدمها القادة المحليين للمنظمات الغير حكومية (NGOs) للحد من الإعتماد على الموارد الخارجية ينطوي على نقلة نوعية من السيطرة الخارجية للترسيخ المحلي وزيادة الحكم الذاتي. النتائج تنطوي على تنفيذ سياسات هامة بشأن تنظيم الأنشطة التجارية ذات الصلة و غير ذات صلة بالمنظمات الغير حكومية (NGO).

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

“[Our NGO] only implements projects that donors are interested in funding,” reports a representative of a local nongovernmental organization (NGO) promoting health through media broadcasting in Phnom Penh (NGO7) (See “Appendix” for full list of all interviews underlying this article). This NGO depends almost entirely on Grants from international NGOs (INGOs) and foundations to finance its projects. At times, the difficulties faced by this NGO in mobilizing funding threaten the organization’s survival. Recently, a local business tycoon, sensing an opportunity in their media broadcasting expertise, approached the organization to help them set up a commercial radio station. The NGO would play a key role in running the radio station and generating profit for both for the organization and this tycoon. However, attractive financially, accepting this offer would imply that the NGO might drift away from its social mission and focus on profit making instead. With its survival at stake, the executive director has a tough decision to make. This case epitomizes issues experienced by about 1,350 active NGOs in Cambodia, many of which are local organizations depending on foreign assistance for their survival. This article focuses on the challenges faced by Cambodian NGOs when mobilizing resources and investigates the effects of different resource mobilization strategies.

Understanding the effects of different funding mobilization options on the activities of NGOs is critical because of their key roles in Cambodia’s development. Over the past two decades NGOs have managed about 20 % of the foreign assistance to Cambodia (Council for the Development of Cambodia 2011). NGOs are the most prominent civil society group in Cambodia, a country which “never developed critical civil society beyond religious associations” (e.g., the Buddhist pagoda) (Peou 2007, p. 129). At the same time, these NGOs are almost completely dependent on funding emanating from foreign sources and find their agendas defined by stakeholders outside Cambodia. This foreign-dominated process of development has caused concern among political analysts and scholars alike (Barnes 2006; Hughes and Un 2011; Hughes 2003). The sector’s dependence on international donors has constrained its effectiveness in promoting good governance and “meaningful civic engagement and social accountability” (Malena et al. 2009, p. 8). As elsewhere, NGOs have been limited to carrying out largely service-oriented donor agendas and have not played a role in the public sphere as exponents of local civil society [see for example (Bebbington et al. 2008)].

The dependence of NGOs on international donor funding forms a recurring pattern that can also be found in other Asian countries like the Philippines and Thailand. NGOs and other civil society organizations in Asia enjoyed a peak period of donor funding in the 1990s (Parks 2008) as donor countries were enthusiastic about supporting processes of democratization in Asian countries through the development of a strong civil society (Ottaway and Carothers 2000). However, the funding of NGO-implemented development projects in the region by Western nations diminished and became less predictable in the aftermath of the Asian crisis in the late 1990s.

Cambodian NGOs in particular are facing two major interrelated issues: (1) an almost exclusive dependence on an—often foreign—single source of income and, (2) a lack of organizational autonomy in setting their own agenda and policy priorities. The shortcomings in the current literature on resource dependence and strategic responses is that it mainly focuses on either for-profit firms in general (Casciaro and Piskorski 2005) or nonprofit organizations in developed countries, in particular in the Western world (Batley 2011; Froelich 1999; Mitchell 2012). NGOs in developed countries receive funding from other Western sources, often located in their own country. NGOs in developing countries on the other hand receive funding from external sources, either Western or non-western, reflecting not only the dependence of these NGOs from external sources but also their county’s dependence on foreign powers. The latest article on the funding diversification strategies of NGOs in Cambodia published in this journal (Khieng 2013) falls short of addressing their effects on these NGOs in particular from the perspective of such power differentials. To fill this gap, this article will analyze the effects of strategic funding strategies in response to resource dependence among nonprofit organizations from a developing country perspective. The analysis of NGO dependence on external funding sources, the diversification strategies they use to reduce such dependence and the associated effects of funding strategies applied will offer a better understanding of development practices and contribute to the academic literature on resource dependence. The findings will also have policy implications, particularly for NGO leaders facing vital choices.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows: The next section discusses the establishment and development of local NGOs in Cambodia. Then, in subsequent sections, a review of the relevant literature on resource dependence will be offered culminating in an analytical framework, the methodology will be discussed and the empirical findings will be presented. The article concludes with a discussion on the effects of different strategies, past and future trends as well as implications for the NGO sector in the regional context and key issues for further investigation.

NGOs in Cambodia

Between 1975 and 1979, under the Khmer Rouge regime that caused the death of two million Cambodians due to atrocities, forced labor and starvation, international organizations operating in Cambodia were forced to close their offices and leave the country. Immediately after the collapse of the regime in 1979, several organizations such as UNICEF, World Food Program (WFP), the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), and the International Committee of the Red Cross and Oxfam, resumed operation in Cambodia with the immediate task to provide emergency relief assistance (Barton 2001). By the early 1980s, about two dozen international organizations were in the country to support the rehabilitation process.

Bilateral aid, most of which originated from countries of the former Soviet Union, prevailed but dropped in the late 1980s with the end of the Cold War (Ear 2012). A peace agreement for Cambodia’s various factional groups was effectuated in 1991 as a result of international mediation. Two years later when the United Nations Transitional Authority in Cambodia (UNTAC) assisted the first democratic elections, billions of dollars of international assistance poured into the country. Some authors claim international aid or Official Development Assistance (ODA) for post-conflict Cambodia totaled about US$7 billion between 1992 and 2007 (Hughes 2009). This huge amount got economists concerned about the potential distortion of the economy and the government’s ability to respond to economic problems (Godfrey et al. 2002).

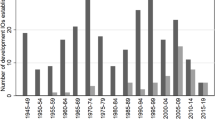

The influx of foreign aid since the 1990s has brought many INGOs to Cambodia and generated an increase in the number of local NGOs (LNGOs) from less than 100 in 1991 to close to 1,000 a decade later (Council for the Development of Cambodia 2006). In 2012 close to 1,400 active NGOs operated in Cambodia (Cooperation Committee for Cambodia 2012). LNGOs have been involved in a wide range of sectors such as health and water sanitation, education, agriculture and advocacy. The boom in LNGOs was supported by UNTAC and INGOs promoting “democracy, human rights, poverty reduction and social development” (Malena et al. 2009, p. 8). However, the growth and consolidation of LNGOs in Cambodia has provoked comments pointing out that LNGO proliferation was more a response to available donor funding or foreign initiatives than “a gradual opening up of democratic space, the natural scaling up of grassroots organizations, the emergence of a culture of volunteerism/social activism or the organized charity of an established middle class” (Malena et al. 2009, p. 8). As many LNGOs did not evolve from the bottom up, these organizations were not based on the real needs of communities (Mansfield and MacLeod 2002; O’Leary 2006). The more so as with the increasing dependence on ODA the process of development in Cambodia is dominated by foreign agencies acting on behalf but in fact beyond the control of local people (Hughes 2004, p. 214). Kheang Un, a Cambodian political scientist, denotes this donor-driven nature of the NGO sector as a “civil society movement without citizens” (Un 2004, p. 272).

The current funding availability for NGOs in Cambodia differs significantly from the heydays of Cambodia as a donor darling. Besides the economic downturn and political development in donor countries, other major challenges in resource mobilization include changing development priorities of donors, their demand for measurable impacts and funding for short-term projects instead of programs. These constraints are preceded by the donors’ concerns about the effectiveness and efficiency of NGO contributions to concrete institutional reforms and the strengthening of civil society. Fluctuations in NGO funding are associated with economic growth in the recipient countries as perceived by donor communities, which applies in particular to Cambodia (Parks 2008). The nearly double-digit growth in gross-domestic product (GDP) for almost a decade (1998–2007) and the increase in income per capita from US$310 to US$550 during this period made Cambodia one of the world’s best performing economies (World Bank 2009). As a consequence, some donors suggested that the needs in Cambodia and the region were not as acute as in other developing countries, in particular in Africa (Parks 2008).

While the supply of donor funding is decreasing, the demand for such funding has been growing among Cambodian NGOs due to their sheer number. The competition for scant resources has resulted in the demise of a number of LNGOs while some INGOs have relocated out of Cambodia. As a recent NGO census (Cooperation Committee for Cambodia 2012) reveals, only 1,350 out of the over 3,000 NGOs in official registration lists of the government agencies are still active.

The sources of revenue among NGOs in Cambodia have become more diverse over the last 5 years. The results from a recent survey among NGOs reveal rather compelling evidence of funding diversification: the percentage of NGOs which reported generating revenue from self-financing activities rose from 6 % in 2006 to 21 % in 2011 (Khieng 2013). In the same period, government support through Grants and contracts increased slightly. The number of NGOs receiving external funding from overseas dropped by 16 % in 5 years. As NGOs have become increasingly dependent on multiple funding sources, they are currently facing new challenges emerging from this diversification as will be discussed below. Before doing so, a review of relevant literature on resource dependence and its effects on NGOs is presented in the next section.

Resource Dependence and Strategic Responses: A Literature Review

Among the authors addressing resource dependence theory (RDT), the contribution by Pfeffer and Salancik (1978, 2003) and Karen Froelich (1999) stand out. Pfeffer and Salancik’s approach offers a combined “account of power within organizations with a theory of how organizations seek to manage their environment” (Davis and Cobb 2010, p. 22). Resources which NGOs are dependent on can be tangible or intangible assets that are used to plan and implement their strategies (Barney and Arikan 2001). Those resources extend beyond funding to include human resources, technology, legitimacy and networks. Pfeffer and Salancik (1978) define dependence as “the product of the importance of a given input or output to the organization and the extent to which it is controlled by relatively few organizations” (p. 237). There are three assumptions in RDT: (a) social context matters; (b) organizations develop strategies to retain their autonomy and goals; and (c) power is important for making sense of why organizations behave and act in certain ways (Davis and Cobb 2010).

External environments matter because, according to Pfeffer and Salancik (2003), organizations depend on their external environments and, if those environments are not dependable (e.g., the resource is unstable), problems arise. Changes in the environments create a challenge for the survival of organizations or force them to adjust their activities. These responses also include seeking alternative sources of income. The extent to which organizations depend on a resource accounts for their vulnerability to external impacts that emanate from other actors in their environment.

Another key implication of RDT is that the more NGOs depend on other organizations, the more important the external organizations are to the operation and survival of NGOs. The more important these external organizations are to LNGOs, the more likely these organizations have a say in the LNGOs’ affairs. Such external control potentially threatens the LNGO’s independence, authenticity, and innovative potential. In addition, the shortage of resources results in NGOs competing for common resources (Hessels and Terjesen 2010). They then face external control by other organizations coexisting in the shared environment, especially when they can no longer depend on this environment (Pfeffer and Salancik 1978). However, Mitchell (2012) proposes that NGOs are important parts of the civil society sector and their autonomy vis-à-vis donor organizations is vital.

The RDT has proven to be a very useful instrument for understanding shifts in NGO funding strategies, but it alone is inadequate to explain “conditions under which NGOs surrender organizational control to donors” (Mitchell 2012, p. 3). This shortfall may be due to its overemphasis of the roles of the external environment, its under-appreciation of NGO autonomy and the strategic capacity of NGOs in responding to their environment in the real world (Gerstbauer 2010; Mitchell 2012). To address resource dependence, recent research indicates that diversification is the most common strategic response among NGOs (Mitchell 2012). Davis and Cobb (2010) revisiting RDT suggest that “if dependence comes from relying on a sole-source supplier, then an obvious solution is to find and maintain alternatives” (p. 24).

Empirical evidence from a study of NGOs by Mitchell (2012) proposes that there are three main strategic responses to resource dependence: adaptation, avoidance and shaping (Table 1). Adaptation involves specific strategies such as alignment, subcontracting or perseverance, whichever case would result in NGOs facing the greatest exposure to external control as the exclusive dependence on one source is enforced. NGOs adopting strategies for avoidance, which includes diversification of funding sources, funding liberation, geostrategic arbitrage, specialization and selectivity, are less subject to external control as the exclusive dependence on one source is alleviated. Donor education and compromise form strategies for shaping. This last group of strategic responses represents NGO bargaining power to reject or reverse external control.Footnote 1

In Froelich’s seminal work on funding strategies, the effects of each strategy are analyzed in terms of three main categories of resource diversification strategies for non-profit organizations and NGOs, namely private contribution, government funding, and commercial activity (Froelich 1999). In particular, the effects include revenue volatility, goal displacement effects, process effects, and structure effects (Table 2).

According to Froelich, contributions from donations and Grants (membership fees included), particularly foundation Grants, are not only unpredictable and unstable but also come with sets of conditions (or ‘strings’) that can affect goals and missions of recipient NGOs. For instance, NGOs may have to adjust or align their goals or program priorities to meet the requirements of funding agencies or individual donors, a goal displacement effect. Support from institutional donors is associated with structural change and process effects on non-profit organizations, where “over time, professionalized form of administration emerged and non-profit organizations have increasingly come to resemble for-profit corporations” (Froelich 1999, p. 253).

In diversifying their sources of revenue, NGOs mobilize funding from the government. Such funding may be more predictable and stable. However, there are potential negative effects such as compromising organizational autonomy and program flexibility (Cooley and Ron 2002) as well as vulnerability to economic crisis (Feiock and Jang 2009). If competing for government funding, NGOs have to adjust their goals to align with the requirements of Grants and contracts. NGOs receiving funding from government may find their ability to influence policy making negatively affected as they may come to be viewed as “subordinate instruments” (Mitchell 2012). Additionally, NGOs face potential change in their internal structure and management processes affecting their eligibility for other Grants and donations. Froelich describes the ensuing dynamics as “government-driven professionalization, bureaucratization, and loss of administrative autonomy” of non-profit organizations (Froelich 1999, p. 256).

Besides vying for government funding, NGOs are increasingly involved in different types of income earning activities (Froelich 1999; Hughes and Luksetich 2004; Khieng 2013; Viravaidya and Hayssen 2001; Weisbrod 2000; Young and Salamon 2002). Earned-income or commercial activities may involve “revenue-financed, cost-recovery, or fee-for-service programing within an NGO” (Mitchell 2012, p. 12). According to Froelich, earned-income or commercial activities show moderate volatility, partly due to the possible failure of the venture. Such self-financing activities not only minimize the likelihood of goal displacement but also promote the organization’s flexibility and autonomy vis-à-vis the other two forms of funding strategies. Froelich (1999) rejects the “calls of alarm over commercial strategies” as exaggerated as each of the three funding strategies has its pros and cons (p. 261). The commercialization of services provides NGOs with less restraint revenues and greater flexibility, thereby reducing NGOs’ dependence on external sources and control. Yet, when NGOs are engaged in businesses that are not central or even related to their mission, they could face the issue of mission-drift (Mitchell 2012).

Existing research on resource dependency and strategic responses is mainly based on data from for-profit firms (Casciaro and Piskorski 2005; Dieleman and Boddewyn 2012) or Western contexts (Froelich 1999; Mitchell 2012). First, strategic responses (buffering, merger, or acquisition) applied by private companies may not be applicable to the non-for-profit firms, simply because of their nonprofit legal status and the lack of shareholders.

Second, non-profit organizations in such developed country context are endorsed with generous funding opportunities, subsidies and support from their local institutional donors and government. In contrast, non-profit organizations in developing countries (as in the case of Cambodia) face persistent funding challenges. Because local resources, particularly Grants and donations are relatively scarce, most of these organizations are forced to depend dominantly on funding by Western-based donor organizations. Consequently, the funding strategies in response to resource dependence may vary significantly among organizations located in developed and developing countries, and so may the effects emanating from these strategies. Therefore, an analysis has to acknowledge the embeddedness of findings in their social context. At the same time, the dependency on foreign agencies underpins the inequality between international donors and recipient NGOs in developing countries (Mitchell 2012). Therefore, the dimension of power within this social context has to be part and parcel of such an analysis (Davis and Cobb 2010).

This study aims to contribute to the debate on resource dependence and funding strategies in particular from a developing country perspective. In order to assess how different strategies for addressing funding challenges—such as targeting Grants and donations, seeking government funding and generating earned income—affect the mission, program and financial sustainability of local Cambodian NGOs, we use Froehlich’s four key variables as a framework for the analysis of our data: funding volatility, goal displacement effects, process effects and structure effects. These key variables will be assesses within the social context of heavily aid-dependent Cambodia.

Research Methodology and Data Analysis

The empirical research underlying this article applied both qualitative and qualitative methods, a mixed method using sequential explanatory approach (Creswell 2009); or what Teddlie and Tashakkori (2009) term a sequential mixed design with a focus on qualitative data. The data collection was divided into three main phases: consultation workshops, quantitative survey and key participant interviews. Secondary data including organizational documents (NGO reports, websites, and financial statements) were collected before, during and after visits to NGOs. Data collection was carried out between November 2011 and May 2012.

Two workshops were held with key representatives from civil society organizations, academic institutions and development researchers in Phnom Penh. The proceedings of the consultation workshops contributed to generating topics for the survey. The quantitative survey was conducted face-to-face with the representatives holding the most senior position possible in the NGOs, which included the founders, executive directors, or managers. The survey served two purposes: (a) to define the NGOs’ resource mobilization strategies; and (b) to identify sample NGOs for the qualitative phase. The survey was conducted in five regions across Cambodia (Table 3). The sample comprised of 688 randomly selected NGOs with 312 NGOs that participated in the survey accruing to a 45 % response rate. The random selection method implies that the survey data is only representative of the NGOs in the five regions. However, the data potentially have a wider generalizability for the NGO sector in Cambodia for two reasons. First, these five regions have the largest number of NGOs. Second, the participating NGOs have programs covering all regions (25 provinces and cities) of Cambodia.

Of the 312 NGOs, we selected 43 LNGOs for further key participant interviews. The selection was based on the organizations’ reported income earning strategies, regional representation, and sectors in which they engaged. Similar to the survey, the participants in these interviews were most senior members of the NGOs such as founders, executive directors, business or senior managers. During the key participant interviews, the focus was on key topics emerging from the survey findings. Discussions involved the clarification of information provided in the survey, seeking elaboration and explanation of resource mobilization trends and challenges, income earning activities, effects of different funding sources on the NGOs. Key characteristics, including the sectors, sizes, funding sources, geographical distribution, status, and years of establishment of the NGOs in the survey are presented in Table 4.

In terms of data analysis, the quantitative data from the survey was processed by statistical software STATA. Key descriptive statistics such as main strategies for resource mobilization, share of funding sources, trends of funding, and main sectors of the NGOs were generated and analyzed. These key statistics were used to generate topics for the key participant interviews and to select NGOs for the key participant interviews.

The qualitative data from the 43 key participant interviews were transcribed and then coded using Computer Assisted Qualitative Data Analysis (CAQDAS), Nvivo 9. The analysis of the qualitative data followed an inductive approach of thematic coding. The first round of the coding process generated 24 themes (parent nodes), the second round of coding generated an additional pool of 108 nodes (child nodes), and the third round of coding resulted in 68 nodes (child nodes), with 200 nodes consisting of 1,680 references. After the three-level coding processes, relevant key quotes from the interviews were extracted. Queries and models on funding sources and effects were also generated from the qualitative data using Nvivo.

Several measures were taken to warrant research integrity and ethical standard. We used two forms of informed consent to provide information to all participants in both the survey and informant interviews on the research’s background, aim, anonymity, and confidentiality as well as to request permission to tape record. We also informed our participants that research findings would be shared with them as soon as they are publicly available.

Key Findings

Effects of Grants and Donations

Foundation Grants and overseas donations are the largest source of revenue for NGOs in Cambodia, accounting for about 75 % of their total annual budget. Such heavy reliance on foreign assistance, particularly institutional Grants, raises some serious issues. First, the fluctuation of donor money reduces the ability to sustain both activities and benefits to communities. The vulnerability of NGO funding due to external impacts such as the global economic crisis has sparked concerns among NGO representatives. The effects of Grants and donations include the pressure to align with donor priorities and missions. Below, these issues will be addressed.

There are many cases where the NGO missions have essentially drifted during struggles for survival. These NGOs are willing to engage in projects of any kind that could sustain their survival, even if the new engagement involves stepping out of their own expertise and mission, as is illustrated by the example of the earlier cited NGO operating in the health sector:

…the mission and vision of [our NGO] was mainly related to health, but because there was not enough donors funding available in health, [our NGO] have had to diversify not only out of health but in some cases out of media into something entirely new areas. For example, the promotion of reproductive health at the community level, which would not initially be something [our NGO] would do because it’s not media related. Another example would be, we have done some proposals on good governance, which is not health related at all, but because of the lack of funding available for projects that do relate exactly to the mission and vision, it’s diversification! [laughed]…At [our NGO], it is a completely different approach: we only do want the donors want (NGO7).

Outside of the capital city of Phnom Penh, the funding situation for NGOs gets even worse. The bargaining power of smaller and rural-based NGOs is limited as resources are scant and demand is high. The top-down approach to development characteristic of donor-driven projects detrimentally affects the effectiveness of their projects for target communities.

Without considering or consulting with local people, foreign donors’ one-size-fits-all development paradigm has raised many questions about the effectiveness of foreign aid and development in Cambodia. The amount of Grants that “leaks” back to donor countries through the employment of foreign technical advisors and procurements of specific products from these countries has raised the concern of practitioners as well as top government officials.

Another group of NGOs are reluctant to submit to coercion from donors to implement programs beyond their scope. As their first priority, these NGOs seek funding for programs that are in line with their own mission. However, when facing desperate circumstances, they are willing to negotiate with donors the specific programs they want to pursue, which may lead to a compromise between the donors and recipient NGOs.

Other NGOs describe similar processes when mobilizing donor funding for their projects. “So far we have worked based on our mission. We develop our project ideas first and then we find donors later on,” said a leader of an NGO providing vocational training and helping women generate income (NGO29). Another interviewee from an NGO working with the poor and vulnerable people in Phnom Penh describes a similar process: “Some projects are implemented upon request from donors if we believe that they are aware of the real situation on the ground. Some others are decided and approved by our board before we start seeking for funding” (NGO30). In line with this, another NGO administrator stresses that sometimes they respond to a request for proposal that matches with what the NGO does and “won’t change what we do based on the availability of money” (NGO22).

While many local NGOs are willing to do what it takes to get funding critical for their continued operation, some NGO directors indicated that they strictly adhere to their mission. These leaders have a strong belief in their approach of addressing development issues and would not hesitate to turn away any funding opportunity that potentially compromises this mission. A few of these directors feel obliged to persuade their donors to respect and subscribe to their NGO’s mission. A director of a health NGO tries to achieve this by presenting to their potential donor empirical evidence from various surveys and evaluation reports in order to convince them that he would achieve the result as envisioned by the donors despite his diverging approach (NGO34). In case of donors failing to respect their NGO’s mission, some directors would turn down donor funding.

In terms of flexibility, NGO directors view funding from Grants and donations as too rigid and insufficient to cover program administration expenses. Some NGOs receive no funding whatsoever to help with administration costs, while others receive as little as 5–7 % of total costs. Donations from private individuals are more flexible than Grants from institutional donors, though this usually adds to the burden of reporting requirements. As it takes a large number of small donors to fund one project NGOs usually end up using income from other sources or financial reserves to pay administration and operation costs not covered by donors.

Effects of Earned-Income Activities

One in four NGOs in our survey depends partly on revenues from sales of goods and services. However, the total contribution from such activities is relatively small compared to the total annual budget of NGOs in Cambodia. The concepts of “earned-income activities,” “commercial activities,” “entrepreneurial activities,” “business activities” or “social entrepreneurship” are still relatively new and can be controversial for some. Yet, data from NGOs engaging in such activities suggest overall positive effects on the organization and projects. For some NGOs, such earned-income activities are critical not only for their financial stability but also for their independence, community ownership and program sustainability.

If [we] want to make [our NGO] stronger and protected for future [economic] crisis, we have to develop our own income. So [our NGO] is safe today and was able to face the crisis because 50 % of the budget is coming from our own income. If it had not been the case and we were 100 % dependent on donors, maybe today we die (NGO33).

For many NGOs in the study, engaging in some type of business activity related to their mission, one of the additional advantages is the flexibility of the revenues earned. These are the most commonly cited positive effects by NGO leaders and business organizations. This type of resources has also resolved one of the major constraints associated with foundation Grants that restrict NGOs from spending on administration, staff salaries or staff capacity building. As one of our key interviewees aptly commented: “It [revenue from Grants] is easier to get, but harder to spend” while “[earned-income] is harder to get, but easier to spend” (NGO2 & NGO4).

Other effects of earned income are less visible. Though spending earned income comes with less administrative hassle, the approval of any request for expenditure still has to go through their board of directors or management team (depending on the amount). To them, this process promotes “local decision-making” and “ownership of projects” (NGO23, NGO24). Two other local NGOs engaging in education and training compare and contrast the same programs before and after introducing fees for their courses. When the program was free because of donor support, attendance and perception of quality of the courses was low. When fees were introduced, the course attendance and participation improved dramatically and the perception of the program quality became more positive (NGO4 & NGO19). In addition, a few NGO directors mention an increased capacity in (financial) management and administration and improved transparency in decision-making and finance as the effects of earned-income projects (NGO33). Overall, earned income turns into a favorite funding source for NGOs because it enables them to both achieve their mission and generate some income.

Despite of the positive effects discussed earlier, earned income generates social and ethical dilemmas, competition with private sectors and loss of priority of achieving mission. For instance, an NGO in Phnom Penh runs a non-profit restaurant with the purpose to help reintegrate disadvantaged youth into the workforce and society. For this purpose, they train youth on the job. At one point, the NGO was so focused on earning an income from the restaurant that they did not reintegrate one single trainee into society over a one-year period. This NGO lost track of its objective because:

Doing your business is exposing you to more and more outside pressure that is very difficult to step back. And at one point you have to consider whether you want to do it or not. And if you do it too fast, it’s going to be against your main objectives (NGO26).

One of the NGOs in the study is a well-established Cambodia-based organization that operates in multiple countries. Its revenues from earned-income activities are large enough to cover all its operational expenses. This organization is able to allocate the rest of its external resources (e.g., Grants and overseas donations) to increase impacts to its beneficiaries through employment and university scholarships for disabled youth. However, according to its representative, the challenge is to balance moneymaking and social service provision, a double mission that is difficult to achieve (NGO13).

Effects of Government Funding

The share of government Grants and contracts is the smallest among the three main funding sources for NGOs in Cambodia. “We wish there were government Grants”, many of our participants moaned. Only a few NGOs report receiving direct government Grants and contracts while others obtain different types of support including donations or free property leases (e.g., a piece of land for office or school), and tax exemptions for their businesses or imported goods. Although the number of NGOs in this category is small, the findings reveal some adverse effects of government funding. A couple of NGOs receiving government contracts seem to have been established solely for this very purpose. Government contracts are awarded through an annual or biannual bidding process and are mainly for implementing, for example, rural development or agricultural training projects funded by international development agencies and distributed through government agencies. Government contracts are the sole source of revenue for their organizations. They do not usually have any physical office or contract staff and, in case they do, it would be on a temporary basis during a limited period of the project life cycle. When their project finishes, the founders and “staff” transfer to other jobs and the NGOs become inactive but retains their official registration status. As the next phase of calls for bidding arrives, this funding cycle starts again. Not surprisingly, some of the founders of these particular NGOs are senior civil servants in sub-national government institutions (NGO4).

The nature of government contracts implies that eligible NGOs do not get to choose the types of project they pursue. A director of an NGO in Kampong Cham talking about how his organization mobilized government funding says, “At the end of the year, they will announce new projects and then we will contact them [to apply through bidding proposal]. We use to write proposals for Grants but we never receive any” (NGO28). Therefore, these NGOs assume the character of private consultancy firms pursuing projects from sub-national governments with the main objective of making some profit for their directors and members. As one of their directors states: “[After project costs], we have about 40 % of the budget left for sharing among us and for a small amount reserved for future use” (NGO31).

The aforementioned effects are associated with only those NGOs that receive direct financial support from the government such as through Grants and contracts. Many NGOs in this study that report receiving tax exemptions and in-kind donations do not experience any particular effects as a results of receiving such support. Many NGO leaders only wish for more government funding. The lack of government funding not only poses a challenge to NGO funding mobilization, but it also constrains their effective partnership with government institutions (NGO7).

Discussion

This section discusses the effects of the three main resource mobilization strategies of selected Cambodian NGOs, namely revenue volatility, goal displacement effects, process and structure effects. Analysing the empirical findings against the background of Froelich’s framework, the empirical findings are partially aligning with and partially diverting from this framework. Each indicator is evaluated against the existing framework. The indicators are rated high, moderate or low based on the authors’ judgement and analysis of the interview data. Therefore, the evaluation may be subjective but nonetheless useful as it identifies the similar and diverting ways in which resource mobilization strategies affect the key indicators in a developing context.

Revenue Volatility

Revenue volatility is measured by the annual variation in predictability and stability of income sources. The volatility of a revenue source determines the expected level of the source’s stability and reliability. The flow of a low-volatile source of revenue is more stable, reliable and easily predictable. In contrast, high-volatile revenue sources make NGO leaders face many uncertainties and fluctuations regarding the volume and flow of the source. A source of revenue with moderate volatility provides a revenue flow that is adequate at times but not always reliable.

The findings confirm that NGOs depending on Grants and donations face high revenue volatility. However, there is little evidence supporting the volatility of funding from government grants and contracts and earned-income. Government funding has moderate volatility due to two main reasons: (a) the government funding to NGOs is actually financed by international donor agencies; and (b) there is virtually no government support for civil society organizations. Therefore, NGO funding is affected when donor agencies change development priority or cut funding to the Cambodian government.

NGO revenues from earned-income or commercial activities are the least volatile among the three major funding sources. This low volatility is based on the observation that none of the NGOs engaged in such activities reported any particular failure as suggested by Froelich. On the contrary, NGOs are increasingly dependent on their earned income as discussed earlier. However, it is worth recalling that for many NGOs in the study, earned-income activities are very often a sideline of their overall program and total revenue. Many of the programs are not fully self-sufficient because they are partly subsidized by donor funding. This may account for a lower risk of failure.

Goal Displacement Effects

Different revenue strategies have different effects on an NGO’s goal. When a particular strategy has a strong effect on the goal displacement, NGOs are easily distracted from their missions. However, a low goal displacement effect of a revenue source contributes to an NGO’s ability to fulfill their mission. A source of income that affects NGOs’ goals moderately has the potential to create goal displacement if not properly managed by NGO leaders.

A number of NGO directors in our sample who receive funding from Grants and donations indicate that at various instances community members and local authorities have been consulted during the process of defining and finding a bottom-up approach to solve problems in their communities. Overall, it is fair to conclude that NGO dependence on grants and donations results in moderate goal displacement effects.

NGOs receiving financial support from the government are subject to strong goal displacement effects. For a few of the NGOs in this group that are established to bid for government contracts, the effects are strong. Effects on the goals are less noticeable among NGOs who receive government grants and depend on other sources of funding such as donations. For the majority of NGOs in this study accepting nonfinancial support such as tax exemption, in-kind donations or free leases of property from the government, there is not any apparent effect on the goals and mission of the organizations.

Revenues from commercial activities enable NGOs to align their program close to their mission and promote organizational autonomy and independence of external control. This less constrained source of funding is most preferred by NGO leaders because of its flexibility. However, this very flexibility may be cause for concern. The core issue is the potential for goal displacement, which manifests itself when “the profit distribution constraint” is broken, or in other words, when an organization’s economic value outweighs its social value. This occurs in particular when an NGO fails to make any positive changes to the lives of the target group or community. This is the case for a few NGOs who reported losing priority on their social programs while concentrating on making money. Therefore, effects of earned income on the goals and mission of NGOs are rated as moderate.

Process and Structure Effects

Structural change and process effects on non-profit organizations occur when NGOs managers adapt their organizational and administrative structure to meet donors’ requirements. Low effects on the process and structure of NGOs as a result of adopting a particular funding strategy do not pose serious risks to the organizations. However, high effects will result in the internal process and structure becoming more aligned to for-profit firms (e.g., through commercialization) or government agencies (e.g., through government contracts). Moderate effects imply NGOs are more likely to manage any structural and process changes to retain their status and legitimacy.

The effects of foundation grants on NGO processes include formalization, where internal processes in the organizations evolve to conform to different requirements and regulations of donors. In this case, some NGOs have multiple administration and finance standards, which make their leaders and staff struggle with complex and fragmented processes. Individual donations affect NGO processes, as managers have to cope with sending separate reports to the numerous individual donors. There is no apparent effect of corporate contributions to NGO structure and processes, partly because this source of revenue is still relatively small. For example, reporting usually is not a requirement for NGOs who received corporate funding.

Government funding as a source of income also spawns processes of formalization and standardization in NGOs. Receiving government grants and contracts implies that strict standards and formal regulations have to be followed in terms of reporting and accounting requirements. These processes set off by government funding affect the structure of recipient NGOs—an effect Froelich (1999, p. 260) terms professionalized bureaucracy. The current study identifies at least two structural effects. On the one hand, the structure and behavior of NGOs that receive most or all funding from the government reflect that of a government agency. On the other hand, when NGOs are established in order to contribute to the personal profit of their founders by obtaining government contracts, their internal process and structure are similar to the for-profit firms as discussed by Salamon and Anheier (1992), Weisbrod (2000) and Young and Salamon (2002). Dependence on government funding, especially government contracts, may constrain an NGO’s (effective) engagement in political advocacy.

Some of the most pronounced findings pertain to the effects of earned-income activities on the process and structure of NGOs. The leaders of NGOs that are engaged in restaurants and handicraft retail perceive a marked improvement in transparency in accounting and decision-making processes. Such practices also promote “more rational accountability” and a “cost-benefit mentality” (Froelich 1999, p. 259). As some NGOs become increasingly commercialized, there is evidence of change in the organizational structure such as the hiring of business personnel (business manager, marketing staff, and other staff with business skills and background) and the establishment of for-profit sister organizations (commercial or social enterprise). The board of directors as an exponent of the governance structure, plays a more important role in overseeing NGO finances and managing possible conflicts of interest and mission drift. The structural effects of engaging in business activities are predominantly the professionalization of NGO administration (Table 5). These positive effects of earned-income activities on the process and structure of NGOs are relatively consistent with the writings of Hughes and Luksetich (2004), Mitchell (2012), and Weisbrod (2000).

Comparing our findings to Froehlich’s framework, our rating of the effects of resource mobilization strategies among NGOs shows some divergence, particularly on the revenue volatility and goal displacement effects of government funding and earned income (Table 5). On the one hand, our findings suggest that revenue from government sources is less unpredictable than Froelich’s suggestion. On the other hand, we have found that earned income is more stable but has higher risk of goal displacement.

We believe these variations are related to the specific social context in which our study is embedded. As pointed out earlier, most of the studies available—including Froehlich’s conceptual work—address NGO funding strategies in a developed Western context, whereas our study deals with NGOs in a developing country depending on donor agencies located in developed countries, both Western and non-Western. The ensuing large power differential accounts for the contrasting local funding opportunities for NGOs in developed and developing countries. As discussed earlier, the abundance of institutional and government grants available to NGOs and the relative autonomy of the NGOs in developed countries make these organizations less dependent on external funding sources. Conversely, NGOs in Cambodia are fundamentally depending on international funding sources. We suspect this dependency and the limited government support create large power imbalances between donor and recipient NGOs. Lastly, while Cambodian NGO leaders are excited about the potential of earned revenue because of its low volatility, the effect of such income on mission drift is stronger than in developed countries due to the weak governance and management system that afflict Cambodian NGOs.

In addition, the effects of various resource mobilization strategies adopted by Cambodian NGOs are more mixed and complicated than in the case of developed countries. For example, Froehlich’s argument that funding from commercial activities is more volatile than donor funding contrasts with the Cambodian situation characterized by donors’ funding cuts and rapid shifts in donor assistance from one recipient country to another. Likewise, Froehlich’s conclusion that commercial income is weakly associated with goal displacement does not apply to the Cambodian situation where commercialisation may either over-prioritize or jeopardize an NGO’s social mission.

Our study contributes to RDT in several key areas. First, this study is among the few to investigate the effects of NGO strategic responses to funding challenges from a developing country perspective. As noted above, the rather divergent context and power differentials within which NGOs in developing countries operate account for different effects of funding strategies. Second, this research adds empirical data on resource dependence among NGOs. In this respect, the findings clarify the ambiguity and the cross-country variation of effects of funding strategies used by non-profit organizations (as compared to the widely discussed effects of response strategies used by for-profit firms).

The study also enriches the application of RDT by emphasises the influence of the external environment (Pfeffer and Salancik 1978, 2003) on NGOs who are heavily dependent on external resources from foundation grants and donations. Changes in donor priorities, unleashed by global economic downturn, and competition among peer NGOs have negative effects on the effectiveness and survival of NGOs in Cambodia. In turn, these challenges have encouraged NGO leaders to diversify their organization’s revenue sources, particularly into a variety of commercial ventures as evident in many NGOs in the study. Conversely, external impacts emanating from other revenue-providing organizations may have negative consequences: NGOs may not be able to initiate innovative programs and may thus lose their autonomy and mission (Mitchell 2012). On the other hand, self-generated sources of revenue enable NGOs to stay focused on their mission, retaining autonomy and independence.

The effectiveness of each of the three main funding mobilization strategies may vary according to the sectors NGOs are engaged in and their local political and social context. From this specific study of NGOs in Cambodia, it can be inferred that commercial activities, especially those closely related to the core mission of NGOs, could be an effective strategy in reducing dependence on external control. Related business activities are effective for several factors mentioned earlier. Summatively, these include a sense of local ownership through a bottom-up approach of development projects; an improved staff capacity, transparency and organizational governance in general; and wider and sustainable impacts of development projects to beneficiaries.

Apart from commercial activities, NGOs will still depend on foundation grants and donations despite the potential (negative) effects from such dependence. The willingness and capability of NGO leaders to manage such dependence and the associated effects is vital to the effectiveness of their work. Government funding, especially in the form of government contracts, is the least effective resource mobilization strategy. Our findings show that NGOs in a contract-driven partnership with government lose control of their own affairs and turn into a government division.

Conclusion and Future Research

Funding diversification strategies affect NGOs in Cambodia in different ways. The findings of this study confirm some while contradicts other effects of the strategies as described in the existing literature, in particular concerning revenue volatility, goal displacement effects, process, and structure effects. While previous research is based analyzing data from the perspective of developed—and in particular Western countries—this article provides empirical evidence of strategic responses by NGOs in developing and aid-dependent country. The variations as presented from such context contribute to a fuller understanding and application of existing frameworks beyond a Western context. The application of RDT in our study contributes to extending and enriching the theory further by providing an analysis of the strategic responses to resource dependence among non-profit organizations, especially those located in developing nations.

However, the extent to which the effects are felt by NGOs differs according to the sectors in which they engage and the criticality of the funding source. Another salient finding of this study is the emergence of earned-income activities—the commercial turn—among NGOs and, therefore, their reduced external dependence. Yet, the potential positive effects of NGO commercial engagement must be balanced with social and ethical issues such as mission-drift, conflicts of interest and loss of NGO identify. The commercial turn among Cambodian NGOs—while reflecting a process observed among many non-profit organizations in both developing and developed countries—has implications that are far exceeding the domain of revenue diversification. In Cambodia, the commercial turn implies also a paradigm shift. Local NGOs that are used to operating in an externally controlled environment come to experience increased responsibility and accountability vis-à-vis their beneficiaries. Overall, this transformation marks a shift from foreign-dominated to locally embedded processes of development.

Future research will have to address the question whether NGO engagement in commercial activities results in the demise of non-profit organizations. If this is the case, what will then be the character of the ensuing commercial ventures? Will these ventures subscribe to an entrepreneurial or business model? Or will these ventures adopt the social approach resulting in social enterprises to emerge? What will be the impact of social entrepreneurship on developing economies such as Cambodia?

The implications of this study for policy making in Cambodia are twofold. The Cambodian government may well consider the allocation of funding to non-profit organizations that can supplement government public services as well as ensure NGO key roles in strengthening civil society development. This may apply in particular to pro-government NGOs as youth organizations registered under NGO law. Another implication pertains to the regulation of commercial activities, particularly those not related to the mission of the NGOs. As the draft law on NGOs and associations is being introduced, policy makers must take into consideration the increased scope and scale of commercial activities among these non-profit organizations in order to avoid mission drift and to enforce the rules and regulations of non-distribution of profit earned from such activities. The latter is a prerequisite to prevent corruption from taking hold of NGOs.

Notes

Other strategic responses found in the literature include adoptive strategies (Dieleman and Boddewyn 2012), constraint absorption (e.g., merger, acquisition or long-term contracts) (Casciaro and Piskorski 2005), buffering techniques (e.g., through organizational structuring) (Scott 2003; Thompson 2011), domination strategies to restructure the resource environment, or employing resources other than revenues (network, technology and human resources). However, these strategies were identified in the empirical context of for-profit firms rather than non-for-profit or hybrid not-profit-for-profit organizations as in the case of this article.

References

Barnes, C. (2006). Agents for Change: Civil Society Roles in Preventing War & Building Peace. European Centre for Conflict Prevention. Retrieved from http://www.operationspaix.net/DATA/DOCUMENT/5509~v~Agents_for_Change__Civil_Society_Roles_in_Preventing_War___Building_Peace.pdf.

Barney, J. B., & Arikan, A. M. (2001). The resource-based view: Origins and implications. The Blackwell Handbook of Strategic Management, 124–188.

Barton, M. (2001). Empowering a New Civil Society (Pact’s Cambodia Community Outreach Project), p. 47. Phnom Penh, Cambodia: Pact Cambodia. Retrieved from http://www.pactcambodia.org/Publications/NGO_Training/empowering_a_new_civil_society.pdf.

Batley, R. (2011). Structures and strategies in relationships between non-government service providers and governments. Public Administration and Development, 31(4), 306–319. doi:10.1002/pad.606.

Bebbington, A., Hickey, S., & Mitlin, D. C. (2008). Can NGOs make a difference? The challenge of development alternatives. London: Zed Books.

Casciaro, T., & Piskorski, M. J. (2005). Power imbalance, mutual dependence, and constraint absorption: A closer look at resource dependence theory. Administrative Science Quarterly, 50(2), 167–199.

Cooley, A., & Ron, J. (2002). The NGO scramble: Organizational insecurity and the political economy of transnational action. International Security, 27(1), 5–39.

Cooperation Committee for Cambodia. (2012). CSO Contributions to the Development of Cambodia (Development Report). Phnom Penh, Cambodia: Cooperation Committee for Cambodia. Retrieved from http://www.ccc-cambodia.org/downloads/publication/CCC-CSO%20Contributions%20Report.pdf.

Council for the Development of Cambodia. (2006). Report on mapping survey of NGO presence and activity in Cambodia (p. 63). Phnom Penh, Cambodia: Council for Development of Cambodia.

Council for the Development of Cambodia. (2011). Cambodia Development Effectiveness Report 2011, p. 47. Phnom Penh, Cambodia: Council for Development of Cambodia. Retrieved from http://www.cdc-crdb.gov.kh/cdc/aid_management/DER%202011%20FINAL%20(31%20Oct%202011).pdf.

Creswell, J. W. (2009). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Sage Publications, Inc.

Davis, G. F., & Cobb, J. A. (2010). Resource dependence theory: Past and future. Research in the Sociology of Organizations, 28, 21–42. doi:10.1108/S0733-558X(2010)0000028006.

Dieleman, M., & Boddewyn, J. J. (2012). Using organization structure to buffer political ties in emerging markets: A case study. Organization Studies, 33(1), 71–95.

Ear, S. (2012). Aid dependence in Cambodia: How foreign assistance undermines democracy. Columbia: Columbia University Press.

Feiock, R. C., & Jang, H. S. (2009). Nonprofits as local government service contractors. Public Administration Review, 69(4), 668–680. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6210.2009.02016.x.

Froelich, K. A. (1999). Diversification of revenue strategies: Evolving resource dependence in nonprofit organizations. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 28(3), 246–268. doi:10.1177/0899764099283002.

Gerstbauer, L. C. (2010). The whole story of NGO mandate change: The peace building work of World Vision, Catholic Relief Services, and Mennonite Central Committee. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 39(5), 844–865. doi:10.1177/0899764009339864.

Godfrey, M., Sophal, C., Kato, T., Vou Piseth, L., Dorina, P., Saravy, T., et al. (2002). Technical assistance and capacity development in an aid-dependent economy: The experience of Cambodia. World Development, 30(3), 355–373.

Hessels, J., & Terjesen, S. (2010). Resource dependency and institutional theory perspectives on direct and indirect export choices. Small Business Economics, 34(2), 203–220. doi:10.1007/s11187-008-9156-4.

Hughes, C. (2003). The political economy of the Cambodian transition (1st ed.). London: Routledge.

Hughes, C. (2004). The political economy of the Cambodian transition. Taylor & Francis.

Hughes, C. (2009). Dependent communities: Aid and politics in Cambodia and East Timor. Ithaca, NY: SEAP Publications.

Hughes, P., & Luksetich, W. (2004). Nonprofit arts organizations: Do funding sources influence spending patterns? Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 33(2), 203–220. doi:10.1177/0899764004263320.

Hughes, C., & Un, K. (2011). Cambodia’s economic transformation. Copenhagen: NIAS Press.

Khieng, S. (2013). Funding mobilization strategies of nongovernmental organizations in Cambodia. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 1–24. doi:10.1007/s11266-013-9400-7.

Malena, C., Chhim, K., Hak, S., Heang, P., Chhort, B., Sou, K., … Heng, K. (2009). Linking Citizens and the State: An Assessment of Civil Society Contributions to Good Governance in Cambodia. World Bank Cambodia Country Office.

Mansfield, C., & MacLeod, K. (2002). Advocacy in Cambodia: Increasing democratic space. Phnom Penh: Pact Cambodia.

Mitchell, G. (2012). Strategic responses to resource dependence among transnational NGOs Registered in the United States. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 1–25. doi:10.1007/s11266-012-9329-2.

O’Leary, M. (2006). The influence of values on development practice: A study of Cambodian development practitioners in non-government organisations in Cambodia. Retrieved from http://arrow.latrobe.edu.au:8080/vital/access/manager/Repository/latrobe:19647;jsessionid=9262CBDA1A09BD14363A21FB9E825E1E.

Ottaway, M., & Carothers, T. (2000). Civil society aid and democracy promotion: Funding virtue. Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Parks, T. (2008). The rise and fall of donor funding for advocacy NGOs: Understanding the impact. Development in Practice, 18(2), 213. doi:10.1080/09614520801899036.

Peou, S. (2007). International Democracy Assistance for Peacebuilding. Palgrave Macmillan. Retrieved from http://www.bn.com/w/international-democracy-assistance-for-peacebuilding-sorpong-peou/1113304794.

Pfeffer, J., & Salancik, G. R. (1978). The External Control of Organizations: A Resource Dependence Perspective. SSRN eLibrary. Retrieved from http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1496213.

Pfeffer, J., & Salancik, G. (2003). The external control of organizations: A resource dependence perspective (1st ed.). Stanford, CA: Stanford Business Books.

Salamon, L. M., & Anheier, H. K. (1992). In search of the non-profit sector I: The question of definitions. Voluntas: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 3(2), 125–151. doi:10.1007/BF01397770.

Scott, W. R. (2003). Organizations: rational, natural, and open systems. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Teddlie, C., & Tashakkori, A. (2009). Foundations of mixed methods research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Thompson, J. D. (2011). Organizations in action: Social science bases of administrative theory. Piscataway, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

Un, K. (2004). Democratization without consolidation: The case of Cambodia, 1993–2004. Northern Illinois University, Illinois. Retrieved from http://commons.lib.niu.edu/handle/10843/11406.

Viravaidya, M., & Hayssen, J. (2001). Strategies to strengthen NGO capacity in resource mobilization through business activities. Retrieved August, 8, 2006.

Weisbrod, B. (2000). To profit or not to profit: The commercial transformation of the nonprofit sector. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

World Bank. (2009). Cambodia: Sustaining Rapid Growth in a Challenging Environment: Country Economic Memorandum. Phnom Penh, Cambodia. Retrieved from https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/3142.

Young, D. R., & Salamon, L. M. (2002). Commercialization, social ventures, and for-profit competition. In L. M. Salamon (Ed.), The State of America’s Nonprofit Sector Project, 2002. Washington, DC: Brookings. Retrieved from http://www.aspeninstitute.org/policy-work/nonprofit-philanthropy/archives/nonprofit-philanthropy-7.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The authors are indebted to Willemijn Verkoren, Mr Sivhuoch Ou and two anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments on earlier versions of this article. This project is funded by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO).

Appendix: List of NGOs that Participated in In-Depth Interviews

Appendix: List of NGOs that Participated in In-Depth Interviews

NGO code | Positions of NGO representatives | Date of interview |

|---|---|---|

NGO1 | Executive director | 12-Mar-2012 |

NGO2 | Director | 23-Apr-2012 |

NGO3 | Program manager | 12-Mar-2012 |

NGO4 | Executive director | 12-May-2012 |

NGO5 | Director | 12-Mar-2012 |

NGO6 | Executive director | 9-Apr-2012 |

NGO7 | Program advisor | 26-Mar-2012 |

NGO8 | Executive director | 26-Apr-2012 |

NGO9 | Executive director | 9-Apr-2012 |

NGO10 | Executive director | 11-May-2012 |

NGO11 | Executive director | 24-Apr-2012 |

NGO12 | Country representative | 13-Mar-2012 |

NGO13 | Country director | 1-Nov-2011 |

NGO14 | President | 20-Mar-2012 |

NGO15 | Executive director | 23-Mar-2012 |

NGO16 | Executive director | 6-Mar-2012 |

NGO17 | Executive director | 25-Apr-2012 |

NGO18 | Executive director | 15-Mar-2012 |

NGO19 | Executive director | 10-May-2012 |

NGO20 | Director | 2-Mar-2012 |

NGO21 | President/Founder | 26-Mar-2012 |

NGO22 | Executive director | 19-Mar-2012 |

NGO23 | Executive director | 24-Apr-2012 |

NGO24 | Founder/Executive director | 21-Mar-2012 |

NGO25 | Country representative | 25-Feb-2012 |

NGO26 | Advisor | 9-Mar-2012 |

NGO27 | Director | 10-May-2012 |

NGO28 | Executive director | 27-Apr-2012 |

NGO29 | (1) Executive director; (2) Monitoring and Evaluation Officer | 26-Apr-2012 |

NGO30 | (1) Office Manager; (2) Accounting officer | 29-Mar-2012 |

NGO31 | Director | 16-Mar-2012 |

NGO32 | School director | 11-May-2012 |

NGO33 | Business director | 21-Apr-2012 |

NGO34 | Executive director | 30-Mar-2012 |

NGO35 | Executive director | 16-Mar-2012 |

NGO36 | Director | 5-Mar-2012 |

NGO37 | Director | 23-Apr-2012 |

NGO38 | (1) Executive director; (2) Administration officer | 2-Mar-2012 |

NGO39 | Business manager | 24-Apr-2012 |

NGO40 | Executive director | 26-Apr-2012 |

NGO41 | Executive director | 27-Apr-2012 |

NGO42 | Executive director | 15-Mar-2012 |

NGO43 | Executive director | 19-Mar-2012 |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Khieng, S., Dahles, H. Resource Dependence and Effects of Funding Diversification Strategies Among NGOs in Cambodia. Voluntas 26, 1412–1437 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-014-9485-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-014-9485-7