Abstract

The means, motives, and opportunity of cooperation must be present if organizations are to establish mutual ties. Public benefit and conflict oriented organizations are hypothesized to have stronger motives for cooperation than member benefit and consensus oriented groups, and organizations with broad activity scope are likely to face more opportunities of cooperation than specialized organizations. These hypotheses are strengthened by results from regression analyses. The article further shows a historical decline in both the motives and opportunities for such cooperation in the case of Norway through processes of depoliticization, individualization, and specialization. Thus, here, the preconditions for cooperation within organizational society are gradually deteriorating. Such developments are likely to weaken the interconnectedness of voluntary organizations and the potential micro, meso, and macro benefits of such ties.

Résumé

Les moyens, les motifs et les opportunités de la coopération doivent exister si les organisations établissent des liens mutuels. Le bien public et les organisations orientées vers le conflit ont, par hypothèse, plus de motifs pour la coopération que le bénéfice des membres et les groupes orientés vers le consensus; les organisations dont l’activité est étendue sont susceptibles de trouver davantage de coopération que les organisations spécialisées. Ces hypothèses sont renforcées par les résultats présentés par des analyses régressives. L’article montre de plus un déclin historique quant aux motifs et aux opportunités d’une telle organisation. Dans le cas de Norvège, à travers des processus de dépolitisation, d’individualisation et de spécialisation. Ainsi, ici, les préconditions de coopération au sein de la société organisationnelles sont graduellement détériorées. De tels développements sont susceptibles d’affaiblir l’absence d’interconnexion des organisations volontaires et des bénéfices potentiels micro, méso et macro de telles contraintes.

Zusammenfassung

Mittel, Motive und Gelegenheit zur Kooperation müssen gegeben sein, wenn Organisationen wechselseitige Bindungen aufbauen wollen. Es wird angenommen, dass gemeinnützige und konfliktorientierte Organisationen stärkere Motive für Kooperation haben als mitgliedernützige und konsensorientierte Gruppen und dass Organisationen mit einem breiten Aktivitätsfeld wahrscheinlich mehr Kooperationsmöglichkeiten haben als spezialisierte Organisationen. Diese Hypothesen werden von Resultaten aus Regressionsanalysen gestärkt. Der Artikel zeigt am Beispiel von Norwegen einen Rückgang von Motiven und Gelegenheiten für Kooperation durch Entpolitisierung, Individualisierung und Spezialisierung. Deshalb werden sich auch hier die Voraussetzungen für Kooperation innerhalb einer Organisationsgesellschaft fortschreitend verschlechtern. Solche Entwicklungen werden wahrscheinlich die Vernetzung von Freiwilligenorganisationen und den potentiellen Mikro-, Meso- und Makro-Nutzen solcher Bindungen schwächen.

Resumen

Si las organizaciones pretenden establecer nexos entre sí, es necesario que haya medios, motivos y oportunidades de cooperación. Existe la teoría de que las organizaciones de interés público movidas por los conflictos tienen más motivos para la cooperación que los grupos de intereses personales motivados por los consensos, y que las organizaciones con un ámbito de actividad más amplia tienen más posibilidades de tener más oportunidades de cooperación que las organizaciones especializadas. Estas hipótesis se han visto reforzadas por los resultados de los análisis de regresión. Asimismo, el artículo demuestra una caída histórica tanto en los motivos como en las oportunidades de la cooperación en el caso de Noruega, debido a los procesos de despolitización, individualización y especialización que atraviesa. Ello ha propiciado un deterioro gradual en las condiciones de cooperación dentro de la sociedad organizativa del país nórdico. Es probable que estos desarrollos debiliten la conexión entre las organizaciones voluntarias y los micro-, meso- y macro beneficios potenciales de dichos nexos.

摘要

如果组织之间要建立相互联系,它们必须找到方法、动机和合作的机会。假定那些基于公共利益和冲突的组织具有比基于成员利益和一致意见的团体具有更大的动机来进行合作,同时具有广泛活跃范围的组织很可能比专业化组织面临着更多的合作机会。回归分析也印证了这些假设。本文将通过挪威的例子,采用去政治化、个性化和专业化过程,进一步展示此类合作和动机的历史衰落。因而,这里的组织社会内的合作前提逐渐恶化。这些情况发展下去,将可能削弱志愿组织之间的联系,以及此类联系的潜在微观、细观和宏观效益。

ملخص

الوسائل ، الدوافع ، وفرصة للتعاون يجب ان يكون حاضراً إذا كانت المنظمات سوف تقيم روابط متبادله. النفع العام والمنظمات ذات الإتجاه المتناقض مفترض أن يكون لهما أقوى الدوافع للتعاون عن إستفادة العضو و المجموعات الموجهة نحو توافق الآراء ، والمنظمات التي لديها نشاط واسع النطاق من المرجح ان تواجه مزيداً من الفرص للتعاون عن المنظمات المتخصصه. هذه الفرضيات معززة بالنتائج من تحليل التراجع. المقالة تعرض كذلك الإنخفاض التاريخي في كل من الفرص والدوافع لمثل هذا التعاون فى حالة النرويج من خلال عمليات إزالة الصبغه السياسية ، التفريد ، والتخصص. هكذا ، هنا ، فإن الشروط المسبقة للتعاون داخل المجتمع التنظيمي تتدهور تدريجيا. مثل هذه التطورات من المرجح أن تضعف الترابط بين المنظمات التطوعيه والإحتمال الصغير والمتوسط ، والكلي للإستفادة من هذه الروابط .

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Interorganizational ties cannot be taken for granted; an organization that considers cooperating with another group needs to have the motive, the opportunity, and the means to commit the act. In this article, it is argued that the first and second of these preconditions are increasingly absent in the voluntary sector, and that decreased interorganizational cooperation is likely to ensue. In our analysis of the Norwegian case, we identify three processes in contemporary organizational society which are likely to weaken the preconditions of interorganizational cooperation, namely increasing consensus orientation, member benefit orientation, and specialization. Increasing consensus and member orientation of organizations reduce the utility of other associations as cooperation partners, and specialization reduces the number of potential contact points with other organizations. Unless countered by other trends, the continuation of these developments is likely to weaken the interconnectedness of voluntary organizations.

The literature on interorganizational ties emphasizes both meso, micro, and macro benefits of such collaboration. Interorganizational ties are seen as beneficial for voluntary organizations themselves, for the individuals affiliated with such organizations and for society at large.

For organizations, they are hypothesized to increase efficiency, stability, legitimacy, and access to resources (Oliver 1990). These resources include political influence, funding, information sharing, referrals, and reduced transaction costs (Borgatti and Foster 2003; Gulati and Gargiulo 1999; Oliver 1990).

For individuals, interorganizational ties enhance the value of each membership. Individuals access resources through such ties, and organizations act as resource brokers tying individuals to the relevant resources (Small 2006). One of the main resources that is brokered is linking social capital; i.e., “norms of respect and networks of trusting relationships between people who are interacting across explicit, formal or institutionalized power or authority gradients in society” (Szreter and Woolcock 2004, p. 655). The broader and more comprehensive the ties between organizations, the greater the individual access to linking social capital, information, services, and other resources.

For society, more effective organizations mean more effective production of service and interest mediation. For example, collaboration between health care organizations has been shown to reduce people’s problems with access to care (Hendryx et al. 2002). Organizations that cooperate with other organizations are more effective in the mobilization of advocacy than are isolated groups (Andrews and Edwards 2004). Furthermore, social capital theory states that the trust and social networks embedded in such relationships increase a community’s capacity for collective action (Putnam 1993). According to Putnam, this leads to a host of beneficial outcomes, from economic growth to efficient institutions (ibid).

Thus, if the preconditions of interorganizational cooperation are weakened, the consequences transcend the operations of the organizations themselves and enter the core of the role we often attribute to such groups in maintaining democracy and civil society. In the following, we address this decline hypothesis by examining historical shifts in the orientation and activity profiles of local voluntary organizations in Norway and the consequences of these realignments for interorganizational cooperation.

Before turning to the data, we first review the most relevant literature on cooperation between organizations. Second, we present a typology of the relationship between organizations and their environments, and show how the different orientations of organizations have various consequences for how they are likely to relate to other groups. Third, we examine recent trends in Norwegian organizational society. Finally, we explore the empirical link between changing orientation and interorganizational ties and discuss the implications of our findings.

Determinants of Interorganizational Ties

Why do organizations cooperate with each other? Much like a crime investigation, we need to establish the motive, opportunity, and means of collaboration for the act. In order to have motive, the benefits of cooperating with other organizations must outweigh the costs of establishing and maintaining the ties. For there to be opportunity, there has to be natural contact points between organizations, which are likely to increase in number with an organization’s scope of activities. The available means are contingent upon the external or internal constraints limiting the opportunities for interorganizational cooperation. These potential constraints serve as control variables in our analysis and are not given extensive theoretical treatment.

What are the main motives for cooperation? In which cases do the benefits of ties outweigh the costs? Oliver (1990) identifies six determinants of interorganizational cooperation which apply to all types of organizations. First, organizations may cooperate out of necessity, i.e., to comply with legal mandates or requirements. For the population under study, necessity is rarely the cause for cooperation, as there are few legal requirements for local voluntary associations to worry about.Footnote 1

Second, asymmetric motives are related to ambitions to control or access the resources of another institution or organization, usually related to funding or political influence. It implies an asymmetry of power between the parties cooperating. By contrast, reciprocal relationships occur between parties of comparable strength. The motivation of such collaborative efforts is to coordinate the pursuit of common and mutually beneficial goals. Examples of resources emanating from such relationships are access to timely information, learning from the experience of partners or referrals to others in the network (Borgatti and Foster 2003; Gulati and Gargiulo 1999). According to Oliver (1990), such relationships are characterized by balance, harmony, equity, and mutual support, while asymmetric relationships are coercive and conflictual.

Third, considerations of efficiency lead organizations to establish ties to others in order to improve its input/output ratio, or at least appear to be trying to do so to funding third parties which see cooperation as beneficial to output (Wells et al. 2005). Pooling of resources can improve efficiency on many counts. The possibly most important benefit, however, is that cooperation breeds trust between the parties, and trust reduces transaction costs (e.g., need for formal contracts) (Gulati 1995). If the relationship exceeds the dyad in complexity, this trust can become transitive and spread to other potential collaborative partners.

Fourth, stability motives relate to the expectation that ties to other organizations improve resilience and decrease uncertainty in shifting environments. Organizations that cooperate are more likely to survive than those who pursue a life in isolation (Baum and Oliver 1991; Weed 1991; Wollebæk and Selle 2006). Finally, establishing ties to others can be a way to improve legitimacy, i.e., to demonstrate that the activity is natural and relevant. Connecting to a well-known or prestigious organization is a particularly effective strategy for a new actor in a field. Legitimacy concerns are more acute for organizations which are in opposition to established values in the community in which they operate. Oliver (1990) claims that interorganizational relations are most likely to occur in response to explicit institutional and public criticism.

The effect of cooperation is cumulative and is magnified by diversity. The more diverse networks organizations participate in, the more resources they will have access to, and the more attractive they will become as potential partners. Weak and diverse ties broaden an organization’s strategic capacity, ability to carve out the appropriate strategy for success based on a greater pool of accumulated experience, information, and human capital. This enhances adaptability, widens the range of available choices, and broadens the collective action repertoire (Ganz 2000; Granovetter 1973). Breadth improves the efficiency of the network as a social surveillance mechanism, as “any bad behavior by either partner may be reported to common partners, which serves as an effective deterrent for both” (Gulati and Gargiulo 1999, p. 1447). Furthermore, the positive externalities of broad and diverse ties are more prevalent than for ties within cohesive clusters. In complex and cross-cutting networks, the interorganizational ties serve to transmit trust and information. The dissemination of trust is a core element in a community’s stock of social capital, which is an important determinant of the ability of its constituents to undertake spontaneous collective action (Putnam 1993, 2000). Conversely, organizations with few, narrow, and cohesive ties may fall into a path dependent process in which their range of potential partnerships becomes limited, mobilization for shared purposes becomes less effective, and the collaboration has little consequences for others than the organizations involved in the actual collaboration (Andrews and Edwards 2004; Gulati and Gargiulo 1999).

Motive, Opportunity, and Means for Cooperation

Can we expect these motivations to be equally present in all types of organizations? Oliver (1990) shows that the contingencies vary by type of relationship and types of actors; an asymmetry-motivation for a voluntary association may be to lobby state regulators, while the same motivation for a joint venture in the private sector is to increase its market power. However, we would venture that not only the type, but also the level of motivation varies with the purpose and activities of the organization.

In the following, we introduce two dimensions on which both the purposes of voluntary associations and the perspectives on the values of such associations differ fundamentally; first, between conflict and consensus orientation and second, between member benefit and public benefit orientation (Wollebæk and Selle 2002).

These perspectives have their corollaries in the literature on voluntary organizations, civil society, and democracy. The difference between a conflict perspective (those who see the politicized elements of the voluntary sector as positive and natural) and a consensus perspective (who see disruption and destruction in the same elements) represents perhaps the most important schism in the contemporary literature (Edwards 2004). The conflict perspective emphasizes the role of organizations as a democratic infrastructure, as mediators of interests, and guarantors of multiplicity of values and preferences. The consensus perspective represents a social rather than political interpretation of voluntary organizations, whose most important contribution to society is to create interpersonal ties free of power and dominance and social integration in local communities.

Public benefit groups serve nonmembers (i.e., “the public”) rather than members, while member benefit groups work exclusively for those affiliated with the group (Smith 1993). Directions that emphasize the value of member benefit group either accentuate the positive externalities of the activities within the group (i.e., the social capital perspective) or legitimate representation of interest vis-à-vis powerful institutions (i.e., pluralism, corporatism).

By combining the two dimensions, we arrive at four outcomes in a 2 × 2 table which summarizes four central perspectives and types of organizations in the literature and the organizational landscape. The resulting typology is summarized in Table 1 (below), with the main societal role the perspective ascribes to organizations and some examples of typical organizations within each type.Footnote 2

In the bottom left corner we find organizations that are both consensus oriented and member benefit. We have labelled these groups service organizations as their main purpose is to supply members with benefits, usually in the form of leisure activities. This is an expanding segment of the voluntary sector in Norway (Wollebæk and Selle 2003, 2004). This type of organizations is particularly strongly valued by the sprawling social capital literature, first and foremost represented by Robert Putnam (1993, 2000). Putnam sees civil society primarily as an arena of face-to-face social interaction and socialization. Democracy is created by the by-products of these processes, namely social networks and interpersonal trust. What the associations do is secondary to the structure of the activity. Non-political leisure associations are often hailed as more productive sources of social capital than more conflict oriented groups, as the networks of the former type tend to be more “horizontal” (i.e., power-free) and cross-cutting with regard to established patterns of loyalty in society.

In the upper left quadrant, we find interest organizations, which are conflict and member benefit oriented. Real world examples of such associations are unions and advocacy groups. This category has increased greatly in size over the past couple of decades. New organizations for sick and disabled persons represent a large proportion of this expansion (Wollebæk and Selle 2002). Interest organizations are ascribed fundamental democratic importance by writers in the pluralist vein, who see such groups as genuine expressions of peoples’ interests and preferences. At the same time, cross-pressures resulting from the overlapping character of organizational memberships serve to moderate views and counter factionalism (e.g., Dahl 1961; Rokkan 1967).

The opposite characteristics apply to the organizations in the bottom right quadrant. Communitarian organizations are both public benefit and consensus oriented. Thus, communitarianism represents a reaction against perspectives (such as pluralism) which place utility maximation and self interest at the core of how we understand human action. The normative communitarian perspective we find in the literature on voluntary organizations, downplays local conflict (Bellah et al. 1985; Etzioni 1988). Instead, focus is directed towards the responsibility of local associations to build good local communities, solve social problems, and secure a sense of belonging. Thus, organizations which not only work for the interests of members, but also take considerable responsibility for the benefit of the public are necessary to fulfil these aims. In the real world, neighbourhood and community associations and humanitarian organizations are the closest approximations of these ideals.

Finally, in the upper right quadrant, we find organizations that are simultaneously conflict and public benefit oriented. This characterizes social movements from the countercultures of the nineteenth century to the environmental movement of the late twentieth century. We have labelled these groups critical organizations, as their primary function is to challenge the established consensus. In this perspective on the role of voluntary organizations, which is largely shared by the social movement literature (Della Porta and Diani 2005; Edwards 2004) along with historical institutionalists such as Skocpol (2003) and public sphere theorists such as Cohen (1998), non-political, often purely local initiatives are insufficient as intermediary structures between the individual and the political system. The main function of voluntary organizations is to express and institutionalize the value pluralism in society. Institutional ties from the individual into the political system are decisive to maintain the linkage between citizen and political system. Furthermore, it is argued that a vital civil society cannot only consist of conflict between interests, but that one also seeks to develop “common interests.”

How are these organizational types likely to relate to their environments? Our hypothesis is that being either conflict or public benefit oriented, or both, increases the utility of cooperation. Returning to the motivations outlined in the previous section, achieving efficiency is clearly a universal aim for most organizations. However, we hypothesize that the other cooperation determinants outlined above––asymmetry, reciprocity, legitimacy, and stability––are to a greater extent present in outward- and conflict-oriented organizations. Conflict oriented organizations (i.e., critical and interest organizations) are more likely to try to exercise power over other institutions and legitimacy concerns are more pressing than for non-controversial organizations. Public benefit organizations (i.e., communitarian and critical organizations) are more likely to be both more open towards and interested in the environment than are member benefit organizations. Member benefit organizations have, according to Smith (1993, p. 66), “a less clear sense of mission since so much of what they do involves internal relationships and not external goals.” Public benefit groups are thus more likely to find common ground with other organizations for cooperative arrangements. The openness in the activities of public benefit groups makes their borders more permeable than organizations benefiting only members. This increases the probability of cooperation (Schermerhorn 1975). Finally, we expect organizations that are neither conflict nor public benefit oriented to place less emphasis on stability and survival than more outward-oriented and ideological groups. We assume that the emotional attachment to an organization which is not tied to any purpose beyond supplying the members with a service in the actual situation is weaker than ties to an organization that aims at improving or changing society or defending the salient interests of members. Thus, a service organization has less inherent value and can easily be replaced by another institution offering a similar activity.

The choice of partners is likely to differ. Conflict oriented organizations are likely to seek out partnerships with organizations with which they share a common cause in order to enhance legitimacy or bargaining position. Being public benefit is likely to have a positive effect on broader collaboration, and draw on all organizations that can contribute to community development. Thus, we expect both conflict orientation and public benefit orientation to be positively related to the propensity to cooperate. Conflict orientation is expected to have a positive effect on cooperation with similar actors, while public benefit orientation should affect cooperation with dissimilar actors positively.

Above, we have considered how variations in orientation towards the environment are likely to affect the propensity to cooperate. Now, what about the second precondition of cooperation, opportunity? We hypothesize that the probability of cooperation increases with the number of potential contact points between organizations, which is a function of the organization’s activity scope. Furthermore, more diverse and complex organizations will tend to need more resources than organizations with narrower scope, and will consequently have more incentive to establish ties to other organizations (Aiken and Hage 1968).

A third distinction therefore needs to be introduced, namely between generalist and specialist organizations. Specialized organizations are expected to be less likely to cooperate than are organizations with a broader activity scope (Wells et al. 2005). The specialization dimension cuts across the dimensions above, although it is empirically related to the member benefit–public benefit distinction: the “common good” is a broader goal than the benefit of members, and public benefit organizations will therefore tend to be active in a broader array of fields than member benefit groups.

Finally, there are also variations in the means available to establish cooperation. Large organizations have more resources to spare and cooperation is likely to be less costly for them. The main costs of cooperation are loss of autonomy and use of scarce resources on maintaining the tie (Schermerhorn 1975). Large organizations are expected to bear these costs better than smaller groups (Aiken and Hage 1968). In order to achieve legitimacy the largest and most visible organizations may also be the most attractive cooperation partners. A certain level of formalization can be seen as a prerequisite for all other cooperation than the most non-committal relationships. Organizational age may also increase the probability of cooperation, as old associations have demonstrated stability and reliability and have had more time to accumulate ties. Being part of a national federation may also increase the propensity to cooperate as national relationships are replicated at the local level. Moreover, we expect that interorganizational cooperation is more common in smaller than in larger communities, as interpersonal contacts are likely to be more pervasive in small-scale settings thus facilitating interorganizational ties.

The above factors will serve as control variables when we explore the relationship between orientation, activity scope, and cooperation. Before moving on to the multivariate analyses, we present some findings to support the contention that the Norwegian voluntary sector is moving towards privatization (from public to member benefit), depoliticization (from conflict to consensus orientation), and specialization (from broad to narrow purposes and activities). First, however, a brief presentation of the data and methods is in order.

Data and Methods

We use data from mailed questionnaires of local chapters of voluntary associations in the Hordaland region, Norway (pop. 452,000), which was undertaken in 1999–2000 (N = 4,137).Footnote 3 The questionnaires were mailed to all organizations that were registered in a comprehensive census of all associations in the area. Some 60% responded to the questionnaires in the 28 rural municipalities covered by the census, and 45% in the only city in the area (Bergen, pop. 242,000). The associations under study are active within a wide range of fields, such as economy (e.g., unions), politics, sports, language, alcohol abstention, mission, children’s associations, music and arts, social and humanitarian work, culture and leisure, and neighbourhood activities.

The independent variables are public benefit (versus member benefit) orientation, conflict (versus consensus) orientation, and scope of activity. The public-member benefit and conflict-consensus distinctions are operationalized using two ten-point scales for both dimensions. Public-member benefit is measured by relative agreement/disagreement with the following conflicting statements: (1) Most of the organization’s activities are open to members only versus most of the organization’s activities are open to all; (2) The organization works primarily for the benefit of its members versus the organization works primarily for the benefit of the local community. Agreement with the latter alternatives is interpreted as public benefit orientation. Conflict-consensus orientation is similarly operationalized by the following two statements: (1) It is not important for us to convince others of our values versus it is very important to us to convince others of our values; (2) We are not in opposition to dominant attitudes in society versus we are in opposition to dominant attitudes in society. Agreement with the latter alternatives is interpreted as conflict orientation. The specialist–generalist dimension is represented by an additive index based on the number of a theoretical maximum of 12 different activities the association carried out over the past year. The activities include open meetings, courses or study groups, cultural activities, bazaar or bingo, dances, discos and concerts, fundraising for other purposes than the organization itself, social gatherings for members, social gatherings from other than members, issued newsletter, voluntary communal work (dugnad), and a maximum of two “other activities”-slots left for the organizations to fill out.Footnote 4 The control variables are size, formalization, organizational age, hierarchical structure, and community size. The coding of these variables is given in a separate appendix (Appendix 1).

Cooperation with other organizations was defined in the questionnaire as “cooperating with another organization in the local community on carrying out activities or initiatives in the local community.” The associations were asked to specify the name of the organization(s) they cooperated with and the type of activity or initiative. The coding of the dependent variables was based on these responses. We use three dummy variables representing whether the organization cooperated with others or not, cooperation with an organization of similar type (based on a 15-category typology of organizational purpose), and cooperation with an organization of dissimilar type. We also use a variable representing the total number of cooperative relations (the maximum number of either issues or organizations). We used the logarithm of this variable (+1) in order to normalize the distribution.

The analyses proceed using multivariate regressions (logistic regression of dummy variables and OLS regression of number of cooperative relations). In the regression analyses we use substitution of means if values are missing on one independent variable. If two or more variables are missing, the organization is excluded from the analysis.

Increasing Member Orientation, Depoliticization, and Specialization

Several recent studies from all the Nordic countries have shown that broadly based ideological and public benefit organizations are losing ground (Ibsen 2006; Jeppsson-Grassman and Svedberg 1999; Siisiäinen 2006; Wijkström 1997; Wollebæk and Selle 2002). Below, we briefly document this development based on the responses to the 2000 survey. In the absence of comparable questions going back in time, we use the founding year of the organizations existing in 2000 as a proxy for historical development.Footnote 5

Figure 1 illustrates the historical movement from conflict and public benefit orientation towards consensus and member benefit orientation as a diagonal movement from the upper right corner of the figure towards the bottom left. The second half of the nineteenth century was dominated by the (most often) public benefit and conflict oriented early social movements. There is a shift downwards in the figure (towards consensus orientation) until 1945, as the innovation in organizational society increasingly took place within social and humanitarian organizations and the first organizations for young people (the Worldly Youth League), which are both predominantly communitarian in character. In the first two decades after the Second World War, the humanitarian organizations are still growing significantly and reach their zenith around 1965. At the same time, organized leisure activities, both for adults and children, represent the main areas of growth within organizational society. In the pre-war era, organizations for sports, culture, and leisure were almost only found in the larger cities; by 1970, they were omnipresent. From 1970 towards 2000, there is a minor shift towards public benefit orientation, which is related to the proliferation of local community and cultural heritage groups. On the consensus–conflict dimension, the level of conflict orientation has remained at an all-time low since 1990.

Obviously, there are great variations within each period, and the movement in the figure ignores several important developments which run counter to the main picture. For example, we have witnessed extensive proliferation within one conflict oriented organization type during the 1980s and 1990s, namely organizations for the sick and disabled. There has also been some innovation within the “critical” category, as the environmental movement and other “new social movements” experienced a short period of growth in the 1970s and 1980s. While politically important, these developments are far too small in terms of number of members and organizational entities to offset the main picture; a historical movement of the point of gravitation in the Norwegian voluntary sector from critical organizations, via communitarian organizations, towards the service organizations of the postwar era.

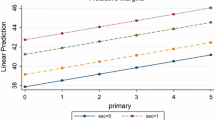

Figure 2 displays the number of activities organized by the local voluntary associations in our survey, by year of founding. The figure shows an ongoing process of specialization since around 1910.

Activity profile is a more fluid measure than basic orientation towards the outside world, and it is not unlikely that organizations narrow or broaden their scope of activities over time. Likewise, a broad spectrum of activities has been shown to be a survival advantage (Wollebæk and Selle 2006), and we may therefore be dealing with a preselection of older, broadly oriented organizations, while their more specialized counterparts disband earlier.

While this is undoubtedly to some extent true, it seems improbable that this should account for the clear trend throughout the twentieth century. Furthermore, other, more anecdotal evidence of the specialization process is also available. Figure 3 shows the proportion of sports and musical associations with only one sport/genre specified in the name of the association, by year of founding. Here, the findings are comparable with the same organizational census which was undertaken in 1980.

The well-aligned lines in the figures show that premature disbanding of specialized organizations cannot account for the specialization tendency we observe when using year of founding as a proxy for historical development; if this were the case, the line for 1980 should be well above the line for 2000. If anything, the recently founded specialized musical associations fared better with regard to survival than their generalist counterparts. Within both fields, there is an undisputable tendency towards specialization. The earliest sports associations offered more than one sport almost without exception, while almost none of the most recent foundings do the same. Among musical associations, most groups founded prior to 1940 named themselves “musical associations,” “choir,” etcetera. By the end of the century, almost half specify which genre of music they perform, such as gospel, traditional folk music, chamber music, rock, and so on.

To what extent does the development since 2000 conform to the trends outlined above? No more recent organizational censuses that can shed light on this question exist.Footnote 6 However, individual level data from the Norwegian section of The Johns Hopkins Comparative Nonprofit Sector Project do not indicate any reversal of the trends above. The proportion of volunteer hours allocated to consensus and member oriented activities, most prominently cultural and leisure, increased slightly from 1997 to 2004 (52–54%). There was a slight decrease within political, humanitarian, and environmental activities (11–10%) and a sharp drop in volunteering for religious purposes (11–6%) (Sivesind 2007). Thus, there are no signs of discontinuation of depoliticization and member orientation, while no recent data exist that allow us to assess whether organizational life has become more or less specialized since 2000.

Consequences for Interorganizational Cooperation

Thus, an undisputable historical shift from public benefit to member orientation, from conflict to consensus orientation, and from general towards specialized purposes and activities, has occurred in Norwegian organizational society. Which consequences does this development have for the interconnectedness of voluntary associations?

Table 2 (below) shows regression analyses of the three measures of cooperation. With few exceptions, the results conform to our expectations. First and foremost, the variables representing motive and opportunity of cooperation have effects in the expected direction. Public benefit organizations are more likely to cooperate than are member benefit groups, and conflict oriented associations are more likely to enter such relationships than are consensus oriented associations. Furthermore, we find the expected tendency of public benefit groups to cooperate more broadly, and seek out cooperation partners of different types from their own. By contrast, conflict oriented groups are more likely to forge partnerships with groups of similar purpose. The impacts of the two dimensions on the total number of relations are of the same magnitude.

The impact of activity scope, the variable capturing opportunities of collaboration, is even stronger. Interestingly, the activity scope has a stronger effect on ties to dissimilar organizations, which indicates that such ties are often the results of organizations venturing beyond their well-defined niche. While the results from the logistic regression indicate that one step on the ten-point scale in the direction of public benefit increases the likelihood of cooperation with 1.3% points and one additional step towards conflict orientation makes cooperation 1.6% points more likely, the addition of one activity increases the probability with 4.6% points. In total, the probability of an organization with little motive and opportunity to cooperate (consensus oriented, member benefit, and only one activity) is 26%, while an organization with the opposite characteristics (conflict oriented, public benefit, and twelve activities) is 90%, all else being equal.Footnote 7

With regard to control variables, which here represent the means of cooperation, the effects of formalization and hierarchical structures conform to expectations. However, some control variables display unexpected effects. Size measured as the logarithm of group size has a negative effect on the likelihood of cooperation, especially with organizations of similar types. This supports theories emphasizing cooperation as a result of resource scarcity (Schermerhorn 1975). Large and stronger organizations seem to have a less acute need for cooperative ties. The orientation variables cancel out the effect of organizational age, which correlated positively with all measures of cooperation but one (see Appendix 2). Community size had the expected negative effect on cooperation between different organizations and the number of ties, but an unexpected positive impact on ties between similar groups. The reason is most likely that in large scale communities, the number of organizations carrying out similar activities is likely to be higher than in the smallest municipalities, in which only a handful, if any potential partners with similar purposes exist.

Conclusion

Most of the literature regards interorganizational ties as positive and important, both to organizations, individuals, and society at large. For such ties to emerge, however, organizations need to have the motive, the opportunity, and the means to create them. We have argued that the motive depends at least in part on organizations’ basic orientation towards their environment; public benefit groups are more likely to find common ground with other organizations than are member benefit associations, and conflict oriented organizations are more likely to have use for alliances with like-minded actors than are consensus oriented groups. Opportunity is contingent upon the range of fields in which the organizations are active, as broad activity scope increases the number of potential contact points with other organizations, increasing the need for coordination and pooling of resources.

The recent developments in the sector indicate a weakening of the preconditions of cooperation. We have documented that there is a historical movement in the point of gravity in the sector, from the critical organizations of the late nineteenth century towards the communitarian organizations of the interwar period and the service organizations of the postwar era. These organization types are all valued by different theoretical approaches. The critical organizations are seen as crucial by social movement and public sphere theorists for their direct and external effects on democracy. Communitarian organizations are seen as important for building cohesive communities and solving problems locally that civil structures are better able to deal with than the public sector. Service organizations are seen as important by some writers in the emerging social capital tradition, especially Putnam, who regard the ties emanating from organizational activity as the pivotal contribution of voluntary organizations to the maintenance and development of democracy.

Our findings question some of the assumptions of Putnam and others, as we have shown that the non-political, leisure service oriented organizations seem largely self-sufficient and less interested in cooperating with other groups than critical, service, and interest organizations. This brings into question the existence of the prime mechanism through which these organizations are thought to foster social capital, namely through the development of trust in social networks. We do not address the degree to which such organizations can develop important social networks internally through face-to-face contact between members, although some studies indicate that their contribution even in this regard is fairly marginal (Ødegård 2006; Wollebæk and Selle 2002, 2007). Thus, our results are a cautionary note to those who argue that democracy can be revitalized through constructing non-political, “horizontal” service organizations.

The findings implicate that if the development continues, organizational society is likely to become increasingly decoupled. Organizations are turning away from the public sphere towards catering for the interests of their members, they are to a lesser mobilizing for a cause they may share with other groups, and they are offering a more limited range of activities. Thus, while the volume of organized activity seems to remain stable (Sivesind et al. 2002; Wollebæk and Selle 2002; Wollebæk et al. 2000), it takes place within an increasingly fragmented organizational society.

There is an “if” of considerable size here, however. First, Fig. 1 indicates a minor communitarian turn over the past two decades. New cultural heritage groups and area associations have been established with purposes that are more likely to benefit from interorganizational ties than the association types that proliferated between 1945 and 1980. So far, however, while heritage associations cooperate very broadly with other associations in their local community, area associations cooperate markedly less.Footnote 8 Instead, they are overrepresented with regard to links to municipal authorities.Footnote 9 Second, it is obviously impossible to foresee future developments. We cannot rule out the reemergence of conflict oriented, public benefit organizations with broad activity scopes. What we can conclude, however, is that the organization types that have held organizational society together––first and foremost the social and humanitarian organizations and the social movements––are almost universally in decline, and that new actors have yet to replace them.

How generalizable are these results? Clearly, they are not idiosyncratic to the Norwegian case. Over time, movements with political and/or ideological purposes have been weakened, while leisure oriented organizations and interest groups have become more dominant in all the countries with encompassing universal welfare states and a history of strong membership-based mass movements, often subsumed under the heading of social democratic civil society models (Janoski 1998). This includes Sweden (Jeppsson-Grassman and Svedberg 1999; Vogel et al. 2003), Finland (Siisiäinen 2006), Denmark (Ibsen 2006) and The Netherlands (Dekker 2004). The recent power and democracy audits in the three Scandinavian countries show very similar recent developments in their respective organizational societies, even though this is interpreted as decline by the Norwegians, renewal by the Danes and a little bit of both by the Swedes (Amnå 2006; Andersen 2006; Østerud et al. 2003).

To a somewhat greater extent than in Norway, however, the depoliticization and member orientation have been countered by the rise of new social movements such as environmental and internationally oriented organizations in other “social democratic” civil societies. However, these organizations are so far limited in size and have proliferated more in terms of nominal membership than volunteers or local chapters (Amnå 2006; Dekker 2004; Wollebæk and Selle 2008). Such organizations have been less successful in Norway, possibly because their concerns were integrated into the political programmes of political parties and public bureaucracies at an early stage (Grendstad et al. 2006). However, while the overall development is perhaps more crystallized in Norway, it is reasonable to hypothesize that the thrust of the argument is valid in comparable organizational societies that have taken a similar course.

If the results above do indicate increasing decoupling of voluntary organizations, the greatest loss is probably not on the part of the organizations themselves. Parallel with the decline in interorganizational ties, we see a tendency towards strengthening of ties between growing organization types and actors within the public and private sector, who control the resources of greatest relevance to specialized, inward oriented groups (i.e., funding and sponsorships). Thus, emerging organization types are behaving rationally and choosing cooperation partners according to their needs. Potentially more serious effects pertain to the externalities of cooperation. A likely outcome is a gradual weakening of the ability of organizations to create and institutionalize social capital and to mobilize for collective action. This reduces the value of each organizational membership and the importance of voluntary associations for social integration and democracy.

Notes

One relatively common example of such collaboration does exist: land owners’ associations are often given the responsibility for the regulation of hunting and fishing rights, and frequently cooperate with the local hunting and fishing association to this end.

A more detailed presentation of the typology is given in Wollebæk and Selle (2002).

For the sake of simplicity, we use 2000 as the year of study in the following.

“Dugnad” is a Norwegian concept covering time-limited, voluntary, unpaid, communal work, and does not have a direct equivalent in the English language. It was voted the “most typically Norwegian word” by the television show Typisk norsk [Typically Norwegian] in 2004.

This is not a perfect method, as we cannot know with any certainty if the organizations have changed over time, or if the organizations that have disbanded have very different characteristics from those that survived. However, we believe our analyses are sound for two reasons. First, the basic characteristics of organizations, such as purpose and orientation, are imprinted in them at a very early stage and are unlikely to change radically (Hannan and Freeman 1984). Second, the developments we describe are in alignment with what can be learned from other sources (see Selle and Øymyr 1995; Wollebæk and Selle 2002 and 2004 for more detailed overviews of the historical developments). We are thus confident that the trends we describe in this section are real developments and not an artifact of the limitations of available data.

A full update of the organizational data used in this article is planned for 2009.

Other variables in the regression are ascribed mean values in this calculation.

Some 27% of cultural heritage associations cooperated with organizations of other types, while 18% cooperated with associations of same types. Ten percent of area associations cooperated with other groups of same type, and 10% with associations of different types. The percentages for the sample as a whole are 18% and 19%.

Some 24% of area associations cooperated with municipal authorities, compared to 18% of all associations.

References

Aiken, M., & Hage, J. (1968). Organizational interdependence and intra-organizational structure. American Sociological Review, 33(6), 912–930.

Amnå, E. (2006). Still a trustworthy ally? Civil society and the transformation of Scandinavian democracy. Journal of Civil Society, 2(1), 1–20.

Andersen, J. G. (2006). Political power and democracy in Denmark: Decline of democracy or change in democracy. Journal of European Public Policy, 13(4), 569–586.

Andrews, K. T., & Edwards, B. (2004). Advocacy organizations in the US political process. Annual Review of Sociology, 30, 479–506.

Baum, J. A. C., & Oliver, C. (1991). Institutional linkages and organizational mortality. Administrative Science Quarterly, 36(2), 187–218.

Bellah, R. N., Madsen, R., & Sullivan, W. M. (1985). Habits of the heart: Individualism and commitment in American life. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Borgatti, S. O., & Foster, P. C. (2003). The network paradigm in organizational research: A review and typology. Journal of Management, 29(6), 991–1013.

Cohen, J. (1998). American civil society talk. Report From the Institute of Philosophy and Public Affairs, 18(3), 14–20.

Dahl, R. A. (1961). Who governs? Democracy and power in an American city. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Dekker, P. (2004). The sphere of voluntary associations and the ideals of civil society: A West-European perspective. Korea Observer, 35(3), 391–415.

Della Porta, D., & Diani, M. (2005). Social movements: An introduction. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

Edwards, M. (2004). Civil society. Cambridge: Polity.

Etzioni, A. (1988). The moral dimension: Toward a new economics. New York: Free Press.

Ganz, M. (2000). Resources and resourcefulness: Strategic capacity in the unionization of California agriculture, 1959–1966. American Journal of Sociology, 105(4), 1003–1062.

Granovetter, M. (1973). The strength of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology, 78, 1360–1380.

Grendstad, G., Selle, P., Strømsnes, K., & Bortne, Ø. (2006). Unique environmentalism: A comparative perspective. New York: Springer.

Gulati, R. (1995). Does familiarity breed trust? The implications of repaired ties for contractual choice in alliances. Academy of Management Journal, 38, 85–112.

Gulati, R., & Gargiulo, M. (1999). Where do interorganizational networks come from? American Journal of Sociology, 104(5), 1439–1493.

Hannan, M. T., & Freeman, J. (1984). Structural inertia and organizational change. American Sociological Review, 49, 149–164.

Hendryx, M. S., Ahern, M. M., Lovrich, N. P., & Curdy, A. H. (2002). Access to health care and community social capital. Health Services Research, 37(1), 87–103.

Ibsen, B. (2006). Foreningslivet i Danmark. In T. P. Boje & B. Ibsen (Eds.), Volunteering and Nonprofit in Denmark—Volume, Organization, Economy and Employment (Frivillighed og nonprofit i Danmark––omfang, organisation, økonomi og beskæftigelse) (pp. 41–96). København: Socialforskningsinstituttet.

Janoski, T. (1998). Citizenship and civil society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Jeppsson-Grassman, E., & Svedberg, L. (1999). The shapes of citizenship: Efforts within and outside associational life (Medborgarskapets gestaltningar: insatser i och utanför föreningslivet). In E. Amnå (Ed.), Civilsamhället SOU 1999:84 (pp. 121–180). Stockholm: Fritzes.

Ødegård, G. (2006). Ungdom og demokratiskolering, Vedlegg 2 i NOU 2006:13. Oslo: Barne og familiedepartementet.

Oliver, C. (1990). Determinants of interorganizational relationships: Integration and future directions. Academy of Management Review, 15(2), 241–265.

Østerud, Ø., Selle, P., & Engelstad, F. (2003). The power and the democracy: A final report from the research project power and democracy (Makten og demokratiet: en sluttbok fra Makt- og demokratiutredningen). Oslo: Gyldendal akademisk.

Putnam, R. D. (1993). Making democracy work: Civic traditions in modern Italy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Rokkan, S. (1967). Geography, religion and social class: Crosscutting cleavages in Norwegian politics. In S. M. Lipset & S. Rokkan (Eds.), Party systems and voter alignments (pp. 367–444). New York: The Free Press.

Schermerhorn, J. R. (1975). Determinants of interorganizational cooperation. Academy of Management Journal, 18(4), 846–856.

Selle, P., & Øymyr, B. (1995). Frivillig organisering og demokrati: det frivillige organisasjonssamfunnet endrar seg 1940–1990. Oslo: Det Norske Samlaget.

Siisiäinen, M. (2006). The annual varve of 1997––new associations in Jyväskylä at the end of the 3rd Millennium. Paper presented at the European Voluntary Association Network (EVA) seminar “Nordic civicness revisited in the age of associations,” Tallinn.

Sivesind, K. H. (2007). Frivillig sektor i Norge 1997–2004. Frivillig arbeid, medlemskap, sysselsetting og økonomi (No. 2007:10). Oslo: Institutt for samfunnsforskning.

Sivesind, K. H., Lorentzen, H., Selle, P., & Wollebæk, D. (2002). The voluntary sector in Norway: Composition, changes, and causes. Oslo Report/Institute for Social Research, 2002, 2.

Skocpol, T. (2003). Diminished democracy. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

Small, M. L. (2006). Neighborhood institutions as resource brokers: Childcare centers, interorganizational ties, and resource access among the poor. Social Problems, 53(2), 274–292.

Smith, D. H. (1993). Public benefit and member benefit nonprofit, voluntary groups. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 22(1), 53–68.

Szreter, S., & Woolcock, M. (2004). Health by association? Social capital, social theory, and the political economy of public health. International Journal of Epidemiology, 33(4), 650–667.

Vogel, J., Amnå, E., Munck, I., & Häll, L. (2003). Föreningslivet i Sverige: välfärd, socialt kapital. Statistiska centralbyrån (SCB), demokratiskola, Stockholm.

Weed, F. J. (1991). Organizational mortality in the anti-drunk driving movement: Failure among local MADD chapters. Social Forces, 69(3), 851–868.

Wells, R., Lemak, C. H., & D’Aunno, T. A. (2005). Factors associated with interorganizational relationships among outpatient drug treatment organizations 1990–2000. Health Services Research, 40(5), 1356–1378.

Wijkström, F. (1997). The Swedish nonprofit sector in international comparison. Annals of Public and Cooperative Economics, 68(4), 625–663.

Wollebæk, D., & Selle, P. (2002). The new organization society: Democracy in transition (Det nye organisasjonssamfunnet: demokrati i omforming). Fagbokforlaget, Bergen.

Wollebæk, D., & Selle, P. (2003). Generations and organisational change. In P. Dekker & L. Halman (Eds.), The values of volunteering: Cross-cultural perspectives (pp. 161–178). Kluwer: New York.

Wollebæk, D., & Selle, P. (2004). The role of women in the transformation of the organizational society in Norway. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 33, 120S–144S.

Wollebæk, D., & Selle, P. (2006). Explaining survival and growth in local voluntary associations. Paper presented at the annual ARNOVA conference, Chicago, IL.

Wollebæk, D., & Selle, P. (2007). The origins of social capital: Socialisation and institutionalisation approaches compared. Journal of Civil Society, 3(1), 1–14.

Wollebæk, D., & Selle, P. (2008). The social democratic model. In B. Jobert & B. Kohler-Koch (Eds.), Use and misuse of civil society: From protest to governance (pp. 47–69). London: Routledge.

Wollebæk, D., Selle, P., & Lorentzen, H. (2000). Voluntary work. Social integration, democracy, and economy (Frivillig innsats. Sosial integrasjon, demokrati og økonomi). Bergen: Fagbokforl.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank Per Selle, Karl Henrik Sivesind, and colleagues at the Department of Comparative Politics, University of Bergen and Institute for Social Research, Oslo, for valuable comments on previous drafts.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendices

Appendix 1: List of variables and coding

Organizational age | Logarithm of organizational age in 1980. The logarithmic transformation is used in order to normalize the distribution and because the addition of one unit is probably more consequential towards the bottom end of the distribution. |

Members | Logarithm of individual members in 1980. The logarithmic transformation is used in order to normalize the distribution and because the addition of one unit is probably more consequential towards the bottom end of the distribution. |

Public benefit | Organization type generally works for the benefit of other than members of the organization. Coding based on average scores on two ten-point scales in 2000 survey for each detailed subtype (55 organization types) to which the target organization belongs, as well as a qualitative reassessment of the classification, which led to the reclassification of one organization type. |

Conflict oriented | Organization type is generally in opposition to dominant values in society and tries to convince others of their beliefs. Coding based on average scores on two ten-point scales in 2000 survey for each detailed subtype (55 organization types) to which the target organization belongs, as well as a qualitative reassessment of the classification, which led to the reclassification of one organization type. The combination of public benefit and conflict orientation, and their negative counterparts member benefit and consensus orientation, results in four types of organizations: service (private benefit and consensus orientation), interest (private/conflict), communitarian (public/consensus), and critical (public/conflict). |

Formalization | Additive index of existence of four characteristics of degree of formalization: written minutes from meetings, list of members, balance sheets, yearly reports. |

Turnover | Total annual expenditures in 1999. |

Organizational hierarchy | Additive index of affiliation with regional and national organizations, each level counting one point. |

Community size | Population of municipality in which organization is active (2000). |

Activity scope | Additive index of 12 different activities, each counting one point on index if carried out in past year: open meetings, courses or study groups, cultural activities, bazaar or bingo, dances, discos and concerts, fundraising for other purposes than the organization itself, social gatherings for members, social gatherings from other than members, issued newsletter, voluntary communal work (dugnad), and a maximum of two “other activities”-slots left for the organizations to fill out. |

Appendix 2: Bivariate correlations

Cooperation with… | Number of relations†† | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

All organizations | Org. of similar type | Org. of different types | ||

Public benefit | .12** | .01 | .17** | .17** |

Conflict oriented | .10** | .08** | .08** | .13** |

Activity scope | .24** | .12** | .17** | .28** |

Members†† | .02 | .02 | .02 | .03 |

Turnover† | .10** | .08** | .04 | .11** |

Formalization | .12** | .09** | .06** | .14** |

Age† | .09** | .09** | −.01 | .07** |

Hierarchical structure | .11** | .12** | .05* | .11** |

Community size† | −.01 | .06** | -.07** | −.08** |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wollebæk, D. The Decoupling of Organizational Society: The Case of Norwegian Voluntary Organizations. Voluntas 19, 351–371 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-008-9070-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-008-9070-z