Abstract

Aim

To evaluate the role of low-intensity extra corporeal shock wave therapy (LI-ESWT) in penile rehabilitation (PR) post nerve-sparing radical cystoprostatectomy (NS-RCP).

Materials and methods

This study included 152 sexually active men with muscle invasive bladder cancer. After bilateral NS-RCP with orthotopic diversion by a single expert surgeon between June 2014 and July 2016, 128 patients were available categorized into three groups: LI-ESWT group (42 patients), phosphodiesterase type-5 inhibitors (PDE5i) group (43 patients), and control group (43 patients).

Results

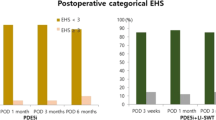

Mean age was 53.2 ± 6.5 years. Mean ± SD follow-up period was 21 ± 8 months. During first follow-up FU1, all patients of the three groups had insufficient erection for vaginal penetration; with decrease of preoperative IIEF-EF mean score from 27.9 to 6.9. Potency recovery rates at 9 months were 76.2%, 79.1%, and 60.5% in LI-ESWT, PDE5i, and control groups, respectively. There was statistically significant increase in IIEF-EF and EHS scores during all follow-up periods in all the study groups (p < 0.001). However, there was no significant difference between the three groups during all follow-up periods. Statistical evaluation showed no significant difference in continence and oncological outcomes during all follow-up points among the three groups (p = 0.55 and 0.07, respectively).

Conclusions

During last follow-up, 16% more patients in LI-ESWT group had recovery of potency as compared to the control group. Although the difference is not statistically significant, but of clinical importance. LI-ESWT is safe as oral PDE5i in penile rehabilitation post nerve-sparing radical cystoprostatectomy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Radical cystoprostatectomy (RCP) remains the gold standard treatment for patients with muscle invasive urothelial carcinoma of the urinary bladder and non-muscle invasive bladder cancer refractory to intravesical therapy [1]. Erectile dysfunction (ED) is an inevitable complication post RCP due to injury of the pelvic plexus or the cavernous nerves during surgery. Incidence of erectile dysfunction following non-nerve-sparing RCP ranges from 90% to 94% [2]. Even in nerve-sparing RCP, some trauma to the nerves, known as neuropraxia, occurs which results in loss of daily and nocturnal erections associated with persistent cavernous hypoxia [3]. The frequency of preservation of potency after nerve-sparing RCP is approximately 60% [4, 5].

The goal of penile rehabilitation (PR) is to regain preoperative erectile function. The optimal penile rehabilitation regimen has not been established [6]. Erectile rehabilitation can take up to 24 months after surgery, according to data presented in the literature [7].

Low-intensity extracorporeal shock wave therapy (LI-ESWT) induces cellular microtrauma, which in turn stimulates the release of angiogenic factors and the subsequent neovascularization of the treated tissue and is used in the management of peripheral neuropathy and in cardiac ischemic tissue. These findings have led to the assumption that if LI-ESWT is applied to the corpora cavernosa, it could improve penile blood flow and endothelial function by stimulating angiogenesis in the penis without any adverse effects [8, 9].

Although several studies showed the value of PR after radical prostatectomy [10], no single study addressed this issue after RCP. Also, no single study evaluated the role of LI-ESWT in PR following RCP. These limitations triggered us to perform a randomized controlled trial (RCT) to evaluate the efficacy of LI-ESWT in penile rehabilitation post nerve-sparing RCP.

Materials and methods

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by our local ethics committee. The study was registered in ClinincalTrial.gov with a registration no NCT02422277. All participants signed a written informed consent before entering the study.

This RCT was conducted between June 2014 and July 2016 including 161 potent sexually active males (mean age: 53.2 ± 6.5 years) with muscle invasive bladder cancer. All patients fulfilled the following criteria: all included patients were married, sexually motivated, in a stable relationship (> 6 months) and sexually active without erectogenic aids preoperatively, tumor confined to the bladder (clinically T3 or less), and the urethra and prostate are free of carcinoma. All patients were free from neurological and penile diseases. The following were the exclusion criteria of the study: Men with Peyronie’s disease or diabetes mellitus, inflammation in the shock wave area, evidence of disease failure after surgery, Patients who developed postoperative complications required hospital readmission after surgery which interfered with the process of shock wave therapy, unstable medical, or psychiatric disorder.

Bilateral nerve-sparing RCP with orthotopic diversion (W-pouch) was carried by a single expert surgeon. Bilateral nerve-sparing procedure was successful in 128 patients based on visual intraoperative preservation of intact neurovascular bundles on both sides according to Walsh’s modification to the standard radical cystectomy [11]. All patients were encouraged to resume their sexual activity as early as the first postoperative month.

Specifics of LI-ESWT

Shock waves were delivered to the distal, mid, and proximal penile shaft, and the left and right crura using a specialized focused shock wave probe. Each patient received 12 sessions of penile LI-ESWT (2/week for 3 weeks, then 3 weeks free of treatment, then 2/week for another 3 weeks) by using Dornier Aries device (Dornier MedTech System, GmbH, Wessling, Germany). The 300 shocks at an energy density of 0.09 mJ/mm2 and a frequency of 120 shocks per minute were delivered at each of the 5 treatment points. Each treatment session continued for 15 min. No local or systemic analgesia was needed.

Study design

Randomization process was carried out between 152 patients using a computer-based software in a 1:1:1 ratio. Patients were randomly assigned to the study groups prior to surgery, once the patient signed the informed consent for participation in the study. Patients available for analysis (128 patients) were allocated into three groups (Fig. 1). Shock wave lithotripsy group (42 patients) without any erectogenic agents. Phosphodiesterase type-5 inhibitors (PDE5i) group (43 patients) who received oral sildenafil of 50 mg daily for 6 months only. Control group (43 patients) was followed up only without any therapy.

Follow-up

Patients were assessed before surgery and at 1 (FU1), 3 (FU2), 6 (FU3), and 9-months (FU4) postoperatively. Erection was assessed by International Index of Erectile Function [IIEF-15] questionnaire and erection hardness score (EHS) [12, 13]. Erection hardness score was obtained by asking the patients about response. Penile Doppler ultrasound [PDU] was performed using Toshiba color duplex ultrasound equipment, model SSA-270A with a linear transducer of 7.5 MHz frequency. The patient was lying down in the supine position in a quite warm room. The whole penis was scanned for cavernosal fibrosis or Peyronie’s disease. The test drug was prostaglandin E1, 20 mcg and the patient left in quiet privacy room, and was encouraged for self-stimulation to optimize the effect of injected drug. The penis was scanned for about 20 min, and at 5 min intervals to record the diameters of right and left cavernosal arteries.

Assessment during each visit included history taking including IIEF and EHS questionnaires, PDU, DRE, urine analysis, kidney function tests, abdominopelvic ultrasound and chest X-ray. More over MRI of the abdomen and pelvis were carried out at 6 months. The erectile function (EF) was grouped as no ED (EF domain > 25), mild to moderate ED (EF domain 11–25), and severe ED (EF domain < 11). The patients were followed for a mean ± SD of 21 ± 8 months (range 9–34), with minimum required follow-up of 9 months.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables in the groups were compared using Chi-square test. Continuous variables were compared using Student’s t test. For repeated measures, paired t test and repeated measures ANOVA were used when appropriate. p value < 0.05 was the cut-off for significance of differences between the groups. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software version 20 program (IBM Corporation; Armonk, New York, USA).

Therapeutic goals

Our therapeutic goals were significant increase in IIEF score defined as a 5-point or greater improvement in the IIEF-EF and/or erection sufficient for vaginal penetration (IIEF-EF Score > 25; EHS ≥ 3). The primary outcome variable was 9-month overall sexual function compared to baseline. Secondary outcome variables were 9-month overall urinary function compared to baseline, oncologic outcomes, time to disease recurrence, peri operative outcomes, and complications.

Results

Mean age was 53.2 ± 6.5 years with mean ± SD follow-up period of 21 ± 8 months (range 9–34). There were no statistically significant differences regarding preoperative patients’ demographic data and tumor criteria among the three groups (Tables 1, 2) and baseline IIEF/EHS values in the three study groups (Table 3). At FU1, all patients of the three groups had an insufficient erection for vaginal penetration (EHS ≤ 2), with the decrease of preoperative IIEF-EF mean score from 27.9 ± 0.7 to 6.9 ± 0.7 and EHS mean score from 3.9 ± 0.3 to 1.9 ± 0.3.

In the three groups, statistical evaluation showed significant increase in total IIEF score, orgasm, desire, intercourse satisfaction, overall satisfaction domains scores, and EHS from FU1 to FU2, FU3, and FU4 (p < 0.001 for all check points) (Table 4). PDU values in the control group showed that the PSV values were comparable on both sides with nearly normal values without significant changes throughout the whole follow-up period. In contrast, the EDV showed initial increase than significant decrease of values (p < 0.001) (Table 5).

Potency recovery rates at FU2 were 45.2%, 55.8%, and 34.9% in LI-ESWT, PDE5i, and control groups, respectively, while potency recovery rates at FU4 were 76.2%, 79.1%, and 60.5% in LI-ESWT, PDE5i, and control group, respectively. Statistical evaluation showed no significant difference in potency recovery rates during the follow-up periods among the groups, regarding IIEF and EHS (p = 0.08 and 0.12, respectively at last follow-up).

There was no significant difference in all domains of IIEF score during the follow-up periods among the groups which is calculated by repeated measure ANOVA test (Fig. 2) (Table 4): For IIEF score (p value = 0.13); for IIEF-EF domain (p value = 0.14); for intercourse satisfaction domain (p value = 0.21); for orgasm domain (p value = 0.93); for desire domain (p value = 0.86); for overall satisfaction domain (p value = 0.07). Comparison between groups regarding IIEF domains showed that all domains improved in all cases along all-time points of follow-up regardless of the groups, with highly significant values (p value < 0.0001 for all points). Also there was no significant difference in EHS during the follow-up periods among the three groups (Fig. 3) (Table 6).

Overall comparisons among the three groups according to penile duplex ultrasound over 3, 6, and 9 months of follow-up, showed no significant difference in EDV during the follow-up periods (p value at last follow-up: right EDV = 0.12, left EDV = 0.29). Also, PSV did not exhibit any significant changes over the time among the study groups (p value at last follow-up: right PSV = 0.8, left PSV = 0.92).

The low-intensity shock wave energy used in this study was not associated with any pain or side effects such as ecchymosis or hematuria.

Discussion

As with other pelvic surgeries, RCP is associated with substantial changes in sexual function. Erectile dysfunction is a well-reported adverse outcome of RCP. However, postoperative ED has received considerable attention after radical prostatectomy, but research focused on the sexual function outcomes of cystectomy has been relatively limited to date [14].

The incidence of preservation of potency after nerve-sparing RCP ranges from 14 to 55% in experienced hands [5, 15]. In our study, rate of erectile function preservation after 9 months was 60% without any medical aid. Potency recovery in our study may be slightly higher than other nerve-sparing cystectomy series due to younger age of the patients (mean age 53 ± 6 years) and all the surgeries were carried out by a single highly expert surgeon [A.M] in doing cystectomy.

ED post RCP can be caused by cavernous nerve trauma, insufficient arterial inflow, hypoxia-related, and neuropraxia-associated damage to erectile tissue resulting in veno-occlusive dysfunction. Also, a small group of men has psychogenic ED [16]. Recovery of potency after RCP does not uniformly occur in all cases, several predictors have been identified including younger age at surgery, better erectile function preoperatively, erectile hemodynamic changes after surgery, and the extent of NVB preservation [17].

During the recovery period of potency, patients are advised to regain erections pharmacologically and resume sexual activity shortly after surgery. The early return to regular sexual activity may improve subjects’ self- body image and self-esteem and avoid a possible long-term adverse effect of sexual activity cessation on the patient and his partner’s relationship. Moreover, early treatment to achieve erection has been shown to improve long-term erectile function recovery of spontaneous erections or response to treatment by minimizing penile structural changes [18].

The aim of any protocol of penile rehabilitation is to prevent the smooth muscle, endothelial, and neural structural alterations, so that early return of preoperative EF can be maximized. Studies reported that early erectile rehabilitation brings forward the natural healing time of potency and maintain non-drug-aided erection [19].

The most common protocol for penile rehabilitation in clinical use involves regular dosage with the PDE5i (sildenafil, vardenafil, or tadalafil). Several clinical studies suggest a potential role for PDE5i provided early after surgery in contributing to the recovery of EF after radical prostatectomy [20, 21].

Other methods of penile rehabilitation after RP included intracavernosal injection and vacuum erection device [22]. Despite excellent results, with previous methods, they were not used routinely as erectile rehabilitation because of the introduction of PDE5 inhibitors and their relative ease of use compared with them.

Penile extracorporeal low-intensity shock wave therapy (LI-ESWT) has recently emerged as a novel and promising modality in the treatment of ED. Unlike other current treatment options for ED, all of which are palliative in nature, LI-ESWT is unique in that it aims to restore the erectile mechanism in order to enable natural or spontaneous erections [23].

In a series of clinical trials, including randomized double-blind sham-controlled studies, LI-ESWT has been shown to have a substantial effect on penile hemodynamics and erectile function in patients with vasculogenic ED without any adverse effects [24,25,26,27]. Different LI-ESWT setup parameters, such as number of pulses, and different treatment protocols, including treatment frequency and length of course, resulted in differences in reported efficacy [28]. Major differences were identified in the randomized controlled trials (RCTs): (1) The energy flux density (EFD) varied from 0.09 to 0.25 mJ/mm2; (2) the number of shock wave pulses of each treatment was between 1500 and 5000; (3) the treatment course of most studies was between 6 and 9 weeks.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first randomized controlled study that evaluated the use of LI-ESWT as a penile rehabilitation method after NS-RCP and compared it with the use of oral PDE5i. We found that all patients suffered from ED during FU1. Potency recovery rates at FU2 were 45.2%, 55.8%, and 34.9% in LI-ESWL, PDE5i, and control group, respectively, while potency recovery rates at FU3, 4 were 76.2%, 79.1%, and 60.5% in LI-ESWT, PDE5i, and control group, respectively. Although there was obvious improvement in erectile function recoverability with use of LI-ESWL and PDE5i, statistical evaluation showed no significant difference in potency recovery rates during the follow-up periods among the 3 groups; this may be explained by the small number of patients in each group. Compared with the control group, the percentage improvement of potency recovery rate was comparable among LI-ESWT group (16%) and PDE5i group (19%) at the last time of follow-up. So, LI-ESWT could be an alternative to PDE5i if there are contraindications. Statistical evaluation showed also no significant difference in oncological or continence outcomes among study groups.

Bannowsky et al. [29], at 52 weeks after nerve-sparing RP, 47% of men taking sildenafil (25 mg) were able to maintain erections sufficient for intercourse, compared to 28% in control group (p < 0.001). Pavlovich et al. [30], randomized 100 men who had undergone nerve-sparing RP into nightly sildenafil group and on-demand placebo group. No significant differences were found in EF between treatments at any time-point after RP.

Finally, we acknowledge that our study suffered from some limitations including small number of patients that might induce type II statistical error and short period of follow-up. Also, the lack of blinding which could have been accounted for if the PDE5i group obtained sham shocks and the LI-ESWT group took placebo pills. Lastly, psychiatric evaluation for our patients was not done. Further studies are warranted to ascertain our results and to evaluate the long-term outcome of erectile function after stoppage of LI-ESWT.

Conclusions

After NS-RCP, spontaneous recoverability of erectile function is expected in approximately 60% of patients within the first year without penile rehabilitation. The use of LI-ESWT or oral PDE5i in penile rehabilitation post NS-RCP improved EF slightly compared to control group. Although the difference is not statistically significant, but may be of clinical importance. Also, statistical non-significance may be due to a small number of patients that induced type II statistical error. The use of LI-ESWT was safe as oral PDE5i. So, LI-ESWT could be an alternative especially if there are contraindications to PDE5i. Finally, a large-scale study is warranted to ascertain our results to determine the value of LI-ESWT as a treatment modality in ED post NS-RCP.

References

Khosravi-Shahi P, Cabezón-Gutiérrez L (2012) Selective organ preservation in muscle-invasive bladder cancer: Review of the literature. Surg Oncol 21:e17–e22

Henningsohn L, Steven K, Kallestrup EB, Steineck G (2002) Distressful symptoms and well-being after radical cystectomy and orthotopic bladder substitution compared with a matched control population. J Urol 168(74):168–175; (discussion 174–175).

Mullerad M, Donohue JF, Li PS, Scardino PT, Mulhall JP (2006) Functional sequelae of cavernous nerve injury in the rat: is there model dependency? J Sex Med 3:77–83

Stein JP, Skinner DG (2003) Results with radical cystectomy for treating bladder cancer: a “reference standard” for high-grade, invasive bladder cancer. BJU Int 92:12–17

Zippe CD, Raina R, Massanyi EZ et al (2004) Sexual function aftermale radical cystectomy in a sexually active population. Urology 64:682–685

Mulhall J (2009) The role and structure of a postradical prostatectomy penile rehabilitation program. Curr Urol Rep 10:219–225

Brock G, Motorsi F, Costa P, Shah N, Martinez-Jabaloyas JM, Hammerer P et al (2015) Effect of Tadalafil once daily on penile length loss and morning erections in patients after bilateral nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy: results from a randomized controlled trial. Urology 85(5):1090–1096

Lei H, Liu J, Li H, Wang L, Xu Y, Tian W et al (2013) Low-intensity shock wave therapy and its application to erectile dysfunction. World J Mens Health 31:208–214

Qureshi AA, Ross KM, Ogawa R, Orgill DP (2011) Shock wave therapy in wound healing. Plast Reconstr Surg 128:721e–727e

Clavell-Hernández J, Wang (2017) R.The controversy surrounding penile rehabilitation after radical prostatectomy. Transl Androl Urol 6(1):2–11

Schlegel PN, Walsh PC (1987) Neuroanatomical approach to radical cystoprostatectomy with preservation of sexual function. J Urol 138(6):1402–1406

Rosen RC, Riley A, Wagner G, Osterloh IH, Kirkpatrick J, Mishra A (1997) The international index of erectile function (IIEF): a multidimensional scale for assessment of erectile dysfunction. Urology 49(6):822–830

Mulhall JP, Goldstein I, Bushmakin AG, Cappelleri JC, Hvidsten K (2007) Validation of the erection hardness score. J Sex Med 4:1626–1634

Colombo R, Bertini R, Salonia A, Naspro R, Ghezzi M, Mazzoccoli B et al (2004) Overall clinical outcomes after nerve and seminal sparing radical cystectomy for the treatment of organ confined bladder cancer. J Urol 171(5):1819–1822

Hernández V, Espinos EL, Dunn J, MacLennan S, Lam T, Yuan Y et al. (2017) Oncological and functional outcomes of sexual function–preserving cystectomy compared with standard radical cystectomy in men: a systematic review. Urol Oncol 35(9):e1–e13

Hatzimouratidis K, Burnett AL, Hatzichristou D, McCullough AR, Montorsi F, Mulhall JP (2009) Phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors in postprostatectomy erectile dysfunction: a critical analysis of the basic science rationale and clinical application. Euro Urol 55(2):334–347

Mulhall JP, Parker M, Waters BW, Flanigan R (2010) The timing of penile rehabilitation after bilateral nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy affects the recovery of erectile function. BJU Int 105(1):37–41

Hekal IA, El-Bahnasawy MS, Mosbah A, El-Assmy A, Shaaban A (2009) Recoverability of erectile function in post-radical cystectomy patients: subjective and objective evaluations. Eur Urol 55(2):275–283

Mulhall JP (2008) Penile rehabilitation following radical prostatectomy. Curr Opin Urol 18(6):613–620

Nehra A, Grantmyre J, Nadel A, Thibonnier M, Brock G (2005) Vardenafil improved patient satisfaction with erectile hardness, orgasmic function and sexual experience in men with erectile dysfunction following nerve sparing radical prostatectomy. J Urol 173(6):2067–2071

Montorsi F, Brock G, Stolzenburg JU, Mulhall J, Moncada I, Patel HR et al (2014) Effects of tadalafil treatment of erectile function recovery following bilateral nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy: a randomized placebo-controlled study (REACTT). Eur Urol 65(3):587–596

Raina R, Agarwal A, Ausmundson S, Lakin M, Nandipati KC, Montague DK et al (2006) Early use of vacuum constriction device following radical prostatectomy facilitates early sexual activity and potentially earlier return of erectile function. Int J Impot Res 18(1):77–81

Vardi Y, Appel B, Jacob G, Massarwi O, Gruenwald I (2010) Can low-intensity extracorporeal shockwave therapy improve erectile function? A 6-month follow-up pilot study in patients with organic erectile dysfunction. Eur Urol 58(2):243–248

Vardi Y, Appel B, Kilchevsky A, Gruenwald I (2012) Does low intensity extracorporeal shock wave therapy have a physiological effect on erectile function? Short-term results of a randomized, double-blind, sham controlled study. J Urol 187(5):1769–1775

Gruenwald I, Appel B, Vardi Y (2012) Low-intensity extracorporeal shock wave therapy: a novel effective treatment for erectile dysfunction in severe ED patients who respond poorly to PDE5 inhibitor therapy. J Sex Med 9(1):259–264

Olsen AB, Persiani M, Boie S, Hanna M, Lund L (2015) Can low-intensity extracorporeal shockwave therapy improve erectile dysfunction? A prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled study. Scand J Urol 49(4):329–333

Kitrey ND, Gruenwald I, Appel B, Shechter A, Massarwa O, Vardi Y (2016) Penile low intensity shock wave treatment is able to shift PDE5i nonresponders to responders: a double-blind, sham controlled study. J Urol 195(5):1550–1555

Lu Z, Lin G, Reed-Maldonado A, Wang C, Lee YC, Lue TF (2017) Low-intensity extracorporeal shock wave treatment improves erectile function: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Urol 71(2):223–233

Bannowsky A, Schulze H, Van Der Horst C, Hautmann S, Junemann KP (2008) Recovery of erectile function after nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy: Improvement with nightly low-dose sildenafil. BJU Int 101(10):1279–1283

Pavlovich CP, Levinson AW, Su LM, Mettee LZ, Feng Z, Bivalacqua TJ et al (2013) Nightly vs. on-demand sildenafil for penile rehabilitation after minimally invasive nerve-sparing radical prostatectomy: results of a randomized double-blind trial with placebo. BJU Int 112(6):844–851

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Tamer S. Zewin, Ahmed El-Assmy, Ahmed M. Harraz, Mahmoud Bazeed, Ahmed A. Shokeir, Khaled Sheir, and Ahmed Mosbah declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zewin, T.S., El-Assmy, A., Harraz, A.M. et al. Efficacy and safety of low-intensity shock wave therapy in penile rehabilitation post nerve-sparing radical cystoprostatectomy: a randomized controlled trial. Int Urol Nephrol 50, 2007–2014 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11255-018-1987-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11255-018-1987-6