Abstract

Teachers often find themselves in a position in which they need to adapt technology-enhanced materials to meet the needs of their students. As new technologies—especially those not specifically designed for learning—find their way into schools, teachers need to be able to design learning experiences that use these new technologies in their local contexts. We leverage previous work and new analyses of three cases in this area to identify a ‘fingerprint pattern’ of supports for teachers’ designing, investigating research questions: (1) What are common constructs that can be identified as the ‘fingerprint pattern’ of formal programs aimed at supporting teachers as designers of technology-enhanced learning? (2) What types of learning can such programs support? Although design work was diverse, all studies involved technology as a support for teacher learning and design work, and as a component of their designs for learning. Across studies, our supports involved modeling practice, supporting dialogue, scaffolding design process, and design for real-world use. We view these constructs as a ‘fingerprint pattern’ of design courses. Together, these supported teachers’ deeper understanding and adoption of new pedagogical approaches and inclination to adopt a teacher-as-designer professional identity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

The implementation gap between the context in which an innovation is developed and where it is to be implemented represents one of the core challenges facing many efforts to reform educational practices (Supovitz and Weinbaum 2008). A key issue in crossing this gap is the role of the teacher and her/his understanding and implementation of the innovation (Spillane et al. 2002). From the perspective of some researchers, the solution has been to emphasize the fidelity of the initial innovation as it was developed in the laboratory setting (Ruiz-Primo 2006). Others have sought to solve this through a focus on principle-based descriptions (Kali et al. 2009) of how innovations should function in practice. However, from the perspective of the teachers, the issue has been more one of fitting the innovation, as it is understood, into the constraints of their local teaching contexts (e.g., Keys and Bryan 2001). Including teachers in reform efforts can make the new pedagogy more relevant (Hiller 1995). Keys and Bryan (2001) argued that teachers need to be included in the design of reformed instruction ‘because the efficacy of reform efforts rest largely with teachers’ (p. 631). Providing teachers with support not just to fit the innovation into their classroom but to design innovations that bring specific pedagogical approaches into their classrooms opens opportunities for them to develop practical knowledge of the pedagogical approach. How to position and support teachers’ design efforts has been a concern of recent research and is the focus of this paper.

We position designing as a central piece of teacher practice. We refer to teachers as designers of learning experiences to emphasize teacher involvement in designing from pre-instructional designing of lessons, activities, units and learning environments to their design work that continues into the classroom (Schön 1983, 1987, 1992; Minstrell et al. 2011; Cober et al. 2015). Teachers make design decisions within planned activities in response to myriad emergent needs, constraints and affordances (Matuk et al. 2015). We see a spectrum of possible design activities from making adaptations to existing curricula during or prior to instruction, to designing new learning experiences. Not only do we want teachers to have the capacity to make adaptations to curricula that bring new technology-enhanced learning into their classrooms in ways that fit, we also want them to have the capacity to design new technology-enhanced learning experiences.

There are diverse approaches to supporting teachers to be designers of learning experiences. Likewise, there are myriad pedagogical aims and targets of teachers’ designing. For instance, teachers might redesign a lesson plan to align to an instructional reform, or create entire units of study based on extended professional development experiences. To navigate this array, we introduce the metaphor of fingerprints. Fingerprints are unique; they differ in their specific arches, loops and whorls. Yet, fingerprints all possess ridge patterns. Using the metaphor of a fingerprint, we define the uniqueness in terms of contexts of different professional development approaches, which we thus liken to the distinct arches, loops and whorls on each fingerprint. Continuing the metaphor, we define the similarities across contexts—in this case, supports for teacher’s designing—in terms of a ‘fingerprint pattern’. The metaphor of fingerprint highlights a contextualist stance; each person produces a unique fingerprint and similarly each implementation of professional development would produce a unique fingerprint. Yet, across different approaches to supporting teachers as designers, we can identify a common fingerprint pattern.

From teachers as adaptors to designers of learning experiences

Research has investigated ways to involve teachers in making adaptations to curricula as a form of professional development (Fishman et al. 2003; Voogt et al. 2015). Barab and Luehmann (2003) point out the importance of allowing for ‘adaptation for local circumstances’ (p. 464); such adaptations provide a sense of empowerment (Ben-Chaim et al. 1994) and ownership, making the teachers advocates for the reform (Davis and Varma 2008). However, there is contradicting evidence regarding the benefit of adapting existing materials, with confirming (Penuel and Gallagher 2009), as well as challenging findings (Cviko et al. 2012). When teachers adapt existing curricula, their adaptations do not necessarily align to the intent of the original designs (Penuel and Yarnall 2005; Davis and Varma 2008). This lack of alignment, though sometimes referred to negatively, can be quite useful because of the depth of knowledge teachers have about their students and particular contexts. As Keys and Bryan (2001) note, because teachers ‘are accountable for their students’ learning and well-being in the classroom, only they can resolve all of the competing influences on what is enacted in the classroom’ (p. 637); this includes various constraints, such as time and resources. As teachers’ learning is situative and relates to what is happening in the classroom (Putnam and Borko 2000), their adaptations and implementations of curricula are informed by their knowledge of their classroom contexts (Cohen and Hill 2001; Talbert and McLaughlin 1999), by their beliefs about teaching (Brickhouse and Bodner 1992; Hashweh 1996), by their beliefs about the content area (Bryan and Abell 1999; Clandinin and Connelly 1992), and by the degree to which they see the curricula fitting into their classroom (Blumenfeld et al. 2000; Keys and Bryan 2001).

According to Luehmann (2002) support for adapting curricula should include ‘identifying local needs, critiquing the innovation in light of these needs; visualizing possible scenarios of implementation; and finally, making plans or decisions regarding the implementation’ (p. 10); this description of adaptation resonates professional design practice in fields such as architecture and engineering. In such fields, explicit instruction in design process is generally a part of the education and preparation of professionals. Even in such contexts, novice designers need support to identify learners’ needs and envision the use of possible design solutions (Svihla 2010; Svihla et al. 2009). While teacher preparation programs include designing lessons and units, they are commonly framed as planning as opposed to designing, and commonly omit elements of design process, such as assessment of needs. Similarly, it is uncommon for professional development programs to include support for teachers learning how to design (Capps et al. 2012); instead, the focus tends to be on reformed teaching practice/theory (e.g., teaching inquiry science) (Parke and Coble 1997) and specific content (e.g., nature of science, new curricular standards) (Lynch 1997) but usually not explicitly on design processes (Basista and Mathews 2010; Akerson et al. 2007; Blanchard et al. 2008; Johnson 2007; Johnson et al. 2007; Akerson and Hanuscin 2007).

Designing curricula is a complex endeavor that requires professional support. For instance, Lakkala et al. (2005) describe a case in which teachers designed and implemented inquiry units that incorporated ‘collaborative technology to support the sharing of knowledge’ (p. 337); however, they struggled to support their students in collaborative inquiry. Although they intended to encourage their students to engage in inquiry in deliberate, purposeful ways, the teachers ‘did not necessarily know good methods and practices for structuring and scaffolding students’ inquiry efforts,’ (p. 351). This example suggests an important area of focus for professional development, which highlights that design represents an important capacity in the set of skills required for teachers (McKenney et al. 2015). Many approaches to involving teachers as designers are framed as—or function as—professional development (Roschelle and Penuel 2006; Deketelaere and Kelchtermans 1996; Eilks et al. 2004); common structures include co-design and participatory design, both of which place emphasis on developing shared understanding of needs and design goals, as opposed to privileging the needs and goals of researchers (Shrader et al. 2001; Roschelle and Penuel 2006; Ehn 1993; Muller and Kuhn 1993; Voogt et al. 2015). By casting teachers as designers of learning experiences and situating design as a component of teachers’ professional work (Hansen 1998), there is an opportunity for teachers to develop as reflective practitioners (Schön 1987).

Development of teacher identity as designer

Teachers often struggle to think like designers (Bencze and Hodson 1999; Penuel and Gallagher 2009). For instance, Hoogveld and colleagues (2002) noted that teachers struggle in particular with two design phases: ‘problem analysis and evaluation…they attempt to translate curricular goals directly into concrete lessons and they pay relatively little attention to evaluation’ (p. 291). Teachers involved in designing inquiry curricula tend to view their roles (as defined by Vermunt and Verloop 1999) as diagnostician of learning needs and evaluator of learning; they also tend to rank these designerly roles lower than their more traditional roles, such as teacher-as-monitor of student learning. These findings are important because they highlight that not only do teachers need support to develop teaching skills, but additionally, work may be needed to help them understand the value of aspects of design process and to see themselves as designers.

There are different expectations and workplace norms when a design team involves professional designers, researchers, and teachers (Reiser et al. 2000). Whereas designers may focus on theory-driven or data-driven design decisions, teachers leverage practice-based experiences to make decisions (Roschelle and Penuel 2006). Successful design teams value both sets of expertise (Kali et al. 2011). This stresses the need to carefully design the process in which teachers are supported when involved in design, whether it is individual work or as part of a design team, and take into account also the fact that teachers’ learning is situative, and discursive (Putnam and Borko 2000). The current study seeks to understand how this process can work by juxtaposing three studies that explored different design strategies to support teachers as designers. Similarities were sought regarding general strategies to support design, and characterization of teacher learning was explored in each study, especially with regard to changes in beliefs, understandings, practices and identities as designers of technology-enhanced learning experiences. Based on this characterization we discuss the potential, as well as limitations of supporting teachers as designers of technology-enhanced learning.

Rationale and research purpose

Commonly, when teachers are brought into a design process, it is as co-designers or participatory designers, often with a minor role, modifying or critiquing something well-developed with an experienced designer. In the cases we present, the teachers’ role was more substantive—they were responsible for designing and developing new technology-enhanced learning experiences for their students. To do this, they were supported by learning environments we designed for this purpose in each of the cases; therefore, in each of the cases, we also took upon ourselves a designers’ role in considering ways to support teachers in this complex endeavor.

In each case we created spaces for the teachers to interact with each other as designers, reflecting on and engaging in design practices, such as ideation, needs assessment, iteration, and providing an opportunity to discuss failures as a means of evaluation and improvement. These were designed to assist teachers to think expansively about what is allowable and possible in their particular schools. Their designs stemmed from real needs of their local ‘clients’ and as such, their design work dealt with authentic problems.

Based on a cross-case analysis, our research purpose is to identify a ‘fingerprint pattern’ of common constructs that aim to support teachers as designers of technology-enhanced learning experiences and to connect this to types of learning that such supports can bring about among teachers. Specifically, we sought to answer (1) What are common constructs that can be identified as the ‘fingerprint pattern’ of formal programs aimed at supporting teachers as designers of technology-enhanced learning? (2) What types of learning can such programs support?

Methods

We compare and contrast three cases. Each case was part of a separate research study (Table 1), and though related findings have been published elsewhere, this paper presents previously unpublished data and analysis, including new cross case analysis and reformulation of the cases (Walton 1992). Per recommendations on case study (Hyett et al. 2014), we present our approach to case and data selection, a description of each case and its context and cross-case analysis procedures. We considered our data from a social constructivist stance (Merriam 1998). Our methodological approach uses a qualitative lens, thus considering credibility and trustworthiness (Hyett et al. 2014).

Case selection

As part of our approach, we selected cases prior to deeper cross-case analysis, per recommendations by Merriam (2014): selection involved looking across our larger data sets to identify areas of commonality and delimiting each case to similarly bounded phenomena. For instance, in case 1, video records related to a specific brief design activity on designing learning experiences with immersive, interactive technology (Svihla et al. 2013) were excluded from the current data set because they did not relate directly to our more narrow focus. Because each case involves varied data types and methods, we narrowed our focus to identifying common supports, and the types of learning processes and practices they supported in each study, allowing the particularistic qualities of each case to become more salient. We view the common supports as the ridge patterns in the fingerprint metaphor, and the different features in each of the cases as the specific arches, loops and whorls in this metaphor.

To accomplish this, we first presented our individual studies to one another in both written and oral formats and questioned each other about the roles of technology, the instructional approaches, and the participants. Contrasting the three cases, it was easy to note the differences: the geographic contexts (United States, Canada and Israel), pedagogical settings (professional development, course, program), lengths (weeks to years), and particular instructional foci and grade levels of the enacted designs developed by teachers. Looking more deeply, we realized there were many similarities: a focus on teachers as designers of technology-enhanced learning experiences; teachers designing learning experiences that reflected the pedagogical approaches they were learning about but had not necessarily used; and designing for real world use. This iterative process allowed us to make data selection choices based on relevance to our focus, even across different research methods, much in the way that might be conducted by a mixed methodologist.

We present each of the three cases in turn, describing the particular pedagogical focus, the participants and data sources. The first case presents teachers in a course focused on project-based learning. The second case presents teachers participating in professional development focused on the KBC model. The third case presents a set of three courses in which teachers design, enact and conduct a small-scale design-research about their technology-enhanced module. We then describe our analytical approach for comparing cases.

Case 1. Project-based learning course

Pedagogical approach: project-based learning

Project-Based Learning is an approach that encourages learner-centered instruction guided by a driving question. Project-Based Learning typically involves a real-world context for an extended period of time. This approach is intended to promote the development of coherent understanding. Numerous examples and research articles were included in the course as a means to show the range of possible projects and ways to implement them. For instance, teachers read foundational research on project-based learning (Blumenfeld et al. 1991; Brown and Campione 1994; Krajcik et al. 1998; Marx et al. 1997), recent research (Geier et al. 2008), and worked with resources from various sources (e.g., from Buck Institute for Education, UTeach, New Tech Network).

Participants and timeframes

Participants were in-service teachers enrolled in a Spring 2012 course (n = 9) at a research institution located in the southwest United States. The 16-week course met once a week for two and a half hours each week. The course counted as an advanced instructional strategies requirement in their master’s degree program. The teachers designed 6-week project-based units to teach within their classes, which included a range of subject areas and grade levels (e.g., 3rd grade mathematics, 10th grade history, 6th grade science, etc.). In their projects, teachers were required to include driving questions, plans for independent student research, assessments, and related problem-based lessons. They were also expected to incorporate technology in ways that aligned to project-based learning. For instance, instead of asking their students to simply create a traditional slide presentation for their classmates, they were directed to choose a real audience (e.g., young children, an environmental group, museum visitors) and have their students create a product specifically tailored to that audience (e.g., a public service announcement, a media campaign, an interactive visual display).

Data sources

The teachers completed pre- and post-tests at the beginning and end of the course; the pre/post tests included a challenging design question, as well as questions probing beliefs and knowledge of design and experience designing. For instance, the teachers were asked to ‘Describe an experience you have had in the past—either in or out of school—in which you designed something for someone else to use.’ They also responded to Likert items such as ‘Designing is an important skill for teachers’ (1 = Strongly Disagree; 5 = Strongly Agree). The teachers were asked to respond to questions honestly to support course improvement and were assured that their answers would only be read after course grades were submitted. Artifacts of and reflections about their design processes were collected from two technology tools that supported their design work: (a) edWeb.net provided an open community in which participants posted and reflected on their design work; and (b) a shared GoogleDoc provided a closed space for synchronous collaborative note-taking, resulting in 55 pages of notes. The artifacts and reflections in the current case analysis focus on a needs assessment and teachers’ evaluation of their project designs in light of the needs they identified.

Case 2. Knowledge building professional development

Pedagogical approach: knowledge building communities (KBC) model

The KBC model (Scardamalia 2002) is a collaborative approach that engages students in knowledge construction with the support of an online knowledge forum (KF) database where ideas can be shared, critiqued and improved. At the time of the data collection for this study, the approach had been in development for well over a decade and was being expressed via a set of twelve core design principles. Principles for the KBC model are expressed in terms of their socio-cognitive dynamic and technological dynamic. Socio-cognitive dynamics focus on the group and individual processes used to support the KBC model while technological dynamics focus on the features of KF that support group knowledge building. Although participants were encouraged to consider all twelve principles, as the study progressed, focus fell on several of the principles including Rise Above, Improvable Ideas and Epistemic Agency (see example in Fig. 1).

Rise above and improvable ideas are principles named in Scardamalia’s 2002 article that outlined twelve core principles for the Knowledge Building Communities approach

Participants and timeframes

The agenda for the original study was to explore how teachers come to understand the core principles of the KBC model as they engage in designing their implementation of the KBC model in their classrooms and how participation in a local design study group might facilitate this process. Work for the design study groups involved adapting the KBC model to the local contextual constraints of the classrooms while continually expanding the teachers’ understanding of the KBC model. Participants included five (n = 5) in-service teachers and their five classes of elementary students (n = 79) at two different elementary school sites (grades 3 to 6) in Canada. School sites were convenience samples based on teachers’ interest in implementing the technology-supported KBC model (Scardamalia 2002). At each school site, design study groups were formed consisting of two or three teachers and one university researcher (one of the authors of the current paper). The inclusion of the university researcher in the design study group meetings was to ensure that the core principles of the KBC model would be included in the discourse of the groups. The timing and frequency of the study group meetings varied across the two school sites (i.e. monthly vs. weekly) with the monthly study group meeting four times and the weekly study group meeting six times. At both sites the study group meetings were held after school and were generally one hour in length.

Data sources

Pre and post interviews held with each teacher focused on (a) perceived understanding of the core principles of the KBC model, (b) expectations about needing to design adaptations to ensure successful implementation of the KBC model in their classroom, and (c) experience working in collaborative professional development situations. As part of the initial interview, the teachers were also asked about the KBC principles that were going to be a focus for the design of their classroom implementation of the KBC model. Data also included post interviews with the teachers, transcripts of the design study group meetings, teachers’ ratings of their perceived understanding of the core KBC principles, and teacher activity in the collaborative online Knowledge Forum database. Teachers designed for a range of subjects including earth science and ancient civilizations.

Case 3. Teachers as design-researchers program

Pedagogical approach: teachers as design-researchers

The teachers as design-researchers (TaDR) program consists of a set of three semester-long courses designed for in-service teachers pursuing a non-thesis master’s degree in educational technology at the University of Haifa in Israel. The three courses were designed and taught by two of the authors of this paper in the past three years. The TaDR program involves teachers in the design and development of a technology-enhanced learning environment and a small-scale design study that explores the learning afforded by the environment (Sagy and Kali 2014). All courses in the program were based on learning environments designing with Google-Sites that embedded Google Docs. These served as spaces for the teachers to collaboratively build artifacts, provide feedback to each other, and document their design and enactment processes. The first course supported teachers in designing and developing a technology-enhanced learning environment for their own learners (approximately 8 two-hour sessions of learner interaction). The second course focused on enactment and data collection. The third course focused on data analysis and academic writing. We explain our design for supporting teachers in each of these courses below.

Participants and timeframe

Participants included three cohorts of in-service teachers (n = 52) enrolled in the (TaDR) program between the years 2010–2014 (Table 2). The term ‘teachers’ is used broadly in this case to include not only K-12 settings, but also informal and industry settings.

Data sources

Teachers completed a questionnaire at the beginning and final stages of their studies (pre and post) that consisted of 17 Likert type items and one open-ended question regarding the relevancy of various constructs to their professional development.

We focus here on findings based on the open-ended question that referred specifically to the way teachers view the constructs ‘design’ and ‘design-research’ as relevant for their professional development. Note that in order to minimize biases of desirability, the questionnaires were given by a post-doctoral fellow who was not a formal member of the staff. Students were also informed that the answers would not affect their grades in any way.

Preliminary analysis

Each case involved prior analysis. In case 1, qualitative data were initially coded using a previously-developed scheme focused on design (Svihla et al. 2014) and for alignment to Project-Based Learning. In case 2, the researcher transcribed and coded all of the interview and meeting data using a priori codes from the KBC principles but then narrowed the focus of this analysis down to those meetings where participants identified significant changes had occurred. In Case 3, the analysis of teachers’ answers was based on Chi’s (1997) approach for quantification of qualitative data. Using a rubric developed for this study, each answer was assigned a value between (−1) and (+1) for each of the constructs (referred to as their professional development relevance index, Table 3). Since no significant difference was found between cohorts, the analysis in case 3 was based on (unpaired) pre-post comparisons of the whole dataset.

Cross case analysis

As suggested by others, and with the fingerprint metaphor in mind, we explored our cases by seeking commonalities and particularities across them (Stake 2008), using a constant comparative method (Glaser 1965). We compared the set of supports for teachers’ designing in each case. We began with broad categories (technology used to support participant learning, technology participants used for their designs, design tools/processes used, role of design) and created word clouds of our individual preliminary case reports. Together, these led to a set of analytical guiding questions: (1) How familiar were your participant teachers with the technologies? (2) How familiar were your participant teachers with the pedagogy? How open were they to it? (3) How tightly coupled were the pedagogy and technology? (4) What was the role of collaboration—both in reference to the technology and the pedagogy (and teachers’ understanding of how to enact collaborative learning?) (5) In what ways do you see epistemology being useful here? Epistemology of what, specifically? (6) In terms of how we worked with teachers, what cultural beliefs did we wish to instill? (7) In terms of how we worked with teachers, what practices did we wish to instill? (8) In terms of how we worked with teachers, what socio-techno-spatial relations did we leverage/focus on/address? and (9) In terms of how we worked with teachers, how did we leverage/focus on/address interaction with the “outside world”?

We identified related outcomes for the teachers, then sought evidence for their origins; for instance, we sought outcomes related to identity development and beliefs. By comparing findings from each case, we were able to triangulate across qualitative and quantitative approaches (Creswell and Clark 2007), identifying the types of learning fostered by the fingerprint pattern of supports found across cases. It is important to note that we did not seek to assess the quality of the technology-enhanced materials designed and developed by the teachers. Rather, we sought to characterize the teachers’ learning, as we describe below. Cases 1 and 2 include primarily qualitative data whereas Case 3 includes both qualitative and quantitative data, the latter of which were analyzed statistically (Chi 1997). Qualitative analysis focused on codes related to the target pedagogical approach and demonstration of designerly actions.

We aimed for a heuristic quality to our cross-case analysis (Merriam 2014), seeking a fingerprint pattern of supports for teachers’ designing. To enhance credibility, each author independently reviewed each case, challenging inferences and assertions through comments and conversation.

Findings

We first present findings from our analysis of our approaches to supporting teacher as designers of technology-enhanced learning. We then explore the types of learning the courses supported.

Findings: what are common constructs that can be identified as the ‘fingerprint pattern’ of formal programs aimed at supporting teachers as designers of technology-enhanced learning?

Across cases, we identified four main constructs used, albeit in different settings, as a ‘fingerprint pattern’ of supports for teachers’ designing. These constructs are (a) modeling practice in our own teaching and design; (b) supporting dialogue between teachers in their design process; (c) scaffolding design process; and (d) design for real-world use. All four constructs are well known to support learning; here, we consider their particular combination as a key contributor to teacher learning processes and practices related specifically to teachers as designers of technology enhanced learning. We describe here how each construct is expressed in each of the cases, and then describe how the set of constructs supported teacher learning in each case.

Case 1. Project-based learning course

Modeling practice in our own teaching and design

Project-based instruction was modeled throughout the course, beginning with a project launch activity leading into a driving question: How could you prepare diverse students for the workplace and for literate participation in society? Pedagogical practices related to project-based learning were focused on, including developing a stance of learning with students, asking generative questions, asking students to ask their own questions, allowing students to pursue their own ways to answer those questions, and allowing students to struggle rather than intervening at the first sign of difficulty.

Supporting dialogue between teachers in their design process

Dialogue in class was used to elicit and refine teachers’ design ideas. Class sessions included discussion about course readings, design process and project-based learning. The teachers gave each other feedback on their designs during class.

Scaffolding design process

The teachers were scaffolded in their design process by using design tools/processes adapted from professional design practice. The teachers read about design problems and process (Jonassen 2000; Dorst and Cross 2001). They participated in ideation sessions and conducted a needs assessment. Needs assessment is a common component of design process in fields such as engineering. The goal of the needs assessment was to help them consider how to design projects that prepared their students for the real world. They interviewed members of the workplace, asking questions such as ‘What does school need to do to prepare students for the workplace?’ ‘How can the class I teach better prepare students for their futures?’ ‘What skills do you think students most need to learn in school?’ They transcribed their interviews and identified needs, and then ranked these based on their prominence across their interviews. They did the same for their own beliefs, and for those as found in a data set given to them relating the needs as expressed by students at a project-based school, resulting in identified needs as follows: collaboration, problem solving, communication, active learning, professionalism, and authenticity. The teachers later revisited these as a means to evaluate the projects they were designing.

Design for real-world use

The teachers were encouraged to design projects to use in their classrooms. This real-world design approach was also reflected in the pedagogical practices of project-based instruction because it places an emphasis on being public and spilling out of the classroom; this commonly occurs, for instance, by inviting professionals into the class to judge performance or by presenting to a community group. One way the course spilled out of the classroom was through the edWeb.net learning management system, a public community that anyone could join (during the class, teachers from several countries did join); teachers’ reflections and designs were available to this public audience.

Case 2. Knowledge building professional development

Modeling practice in our own teaching and design

The university researcher who participated in design study group meetings was experienced in the implementation of the KBC model (Scardamalia 2002) and therefore offered embedded support and modeling of the KBC approach to the teachers through relating descriptive accounts during the meetings. Each design study group used the online KF database to support their design work and as such experienced engagement as a knowledge building community. This modeled both the potential use of the KF database and how to interact as a knowledge building community.

Supporting dialogue between teachers in their design process

The teachers were supported through dialogue during design study group meetings that served as the primary setting for supporting the teachers’ design efforts. A set of story types emerged as significant segments of discourse. In addition the group utilized the KF database as a means of discussing their design work in between meetings.

Scaffolding design process

Both school sites began with a design conjecture meeting and concluded with a retrospective meeting. During the design conjecture meeting the teachers identified KBC principles that were to be the focus of their designing, they expressed to the group their initial understanding of the principle and included how they thought the principle could be better instantiated in their classroom design. For instance, the principle of Rise Above was identified as a concern for one of the study groups and the discussion during the design conjecture meeting centered on what they could do to change their classroom and the KF database in order to improve their implementation of Rise Above in support of the overall KBC model.

Design for real-world use

Although there was explicit focus on the KBC principles, the teachers’ design work was grounded in the reality of their own classroom where problems and potential solutions to the implementation of the KBC model could be cast against the contextual constraints of the classroom (i.e. curriculum, time and student abilities). Beyond the socio-cognitive and technological aspects of the core KBC principles there was considerable context-specific related designing that was needed at both of the school sites. For instance a student with no functional English came into the one of the classrooms and the design of the KF database was altered to accommodate his communications needs (i.e. increased support for pictorial representations).

Case 3. Teachers as design-researchers program

Modeling practice in our own teaching and design

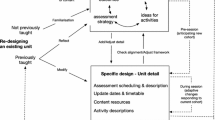

In each of the courses, the instructors modeled the roles teachers were expected to adopt (Fig. 2): (a) teacher-as-mentor, (b) teacher-as-designer, and (c) teacher-as-design-researcher. The teacher-as-mentor role was modeled by conducting all TaDR courses using a design studio approach. In this approach, learners accomplish much of the work during class meetings, while instructors provide feedback, and encourage discussion within and between teams (Kali and Ronen-Fuhrmann 2011). The teacher-as-designer role was modeled by using the Google Sites platform designed by the instructors for each of the courses, which provided teachers with examples of how this platform can be used to design socio-constructivist learning. The teacher-as-design-researcher role was modeled by collecting data from the teachers regarding their attitudes toward “design” and “design” research throughout the TaDR program. Using these data, instructors illustrated various analyses techniques in course 3—with real and relevant data.

Supporting dialogue between teachers in their design process

Small groups of two to three teams followed each other’s projects closely, providing ongoing feedback and support through the design and development (course 1) and the enactment and data collection stages (course 2). For instance, activities in course 2 included whole-class and group-sessions in which teams shared oral and written feedback regarding (a) their enactment experiences (challenges as well as success stories) and (b) their data collection process. In the last stage (course 3), teachers provided peer-feedback to each other on their in-progress data analysis and written reports.

Scaffolding design process

The design process (course 1) was based on a teaching model (Kali and Ronen-Fuhrmann 2011) that integrates the studio approach described above, online resources such as the Design Principles Database (Kali 2006) and common design stages such as conducting needs and content analyses, brainstorming ideas for activities and creating scenarios.

Design for real-world use

Teachers’ enactments and data collection took place in the real world (course 2).

Findings: what types of learning can such experiences support?

We report findings from each case related to what our studies say about teachers’ learning, especially with regard to changes in beliefs, understandings, practices and identities as designers of technology-enhanced learning experiences. We then tie these cases together through discussion.

Case 1. Project-based learning course

Over the course of the semester, the teachers developed as designers; specifically, they developed a more nuanced understanding of the utility of needs-based design. On the pre-test, in response to the question about past design experiences, most included specific references to single types of ‘customers’ (e.g., students or substitute teachers) but only vague references to customer needs, with the most specific being ‘groups can work on their own with no help from the teacher.’ On the post-test, most referenced multiple customers (e.g., students and substitute teachers), and considered their needs from customer perspectives (‘I have to put myself in the position of a stranger [a substitute teacher, a new student, a visitor] coming into a classroom and not knowing any of the daily routines’). They revisited the collective needs they had previously identified as a means to evaluate the projects they were designing. They overwhelmingly reported including opportunities for students to engage in activities to support the development of each skill, and this was also visible in their designs.

On both the pre- and post-tests, teachers reported that design was relevant to their practice. This belief is visible through their descriptions of design process, in which seven of the nine teachers referenced lesson planning (pre-test). For example, one teacher wrote ‘Steps involving designing include: 1. Look at the concepts that students need to cover within the specific time that you are working with. 2. Plan various lesson plans based on whatever concepts you would like students to understand at the end of the unit. 3. Plan various activities that students can participate so they’re engaged and working with the material that was taught. 4. Assess the students to see what information was obtained and what information needs to be reviewed.’

The collaborative notes and reading reflections indicate changes in their beliefs about project-based instruction across the 16 weeks of class meetings. At the first class meeting, all of the teachers were open to the idea of project-based instruction, but most had only passing familiarity with problem-based learning or using collaboration strategies to support it. About half of the teachers cited that they wanted to make learning meaningful (collaborative notes, 1/18/2012) as their reason for enrolling in the course. As one teacher explained, ‘Google just isn’t enough anymore when looking for new ideas’ (collaborative notes, 1/18/2012). Most of the teachers also explained that they enrolled in the class because they wanted to learn to do ‘hands on’ activities; interestingly, few of the teachers cited this as a need when conducting their needs assessment three weeks later, instead focusing on problem solving and collaboration. It is unclear what specifically precipitated this early shift, though the readings, discussion, and needs assessment activity were intended to draw their focus to real world contexts.

The teachers questioned the feasibility of a project-based approach. For instance, halfway through the semester, they read an article in which the teacher spends several class periods allowing students to grapple with how to treat missing data (O’Connor et al. 1998); in response, the teachers raised questions about time and tradeoffs with coverage (collaborative notes, 3/21/2012), ‘How much time can you realistically devote to a learning experience like the one described in the chapter? How much time is too much? You still have to cover content at some point.’ In the same class session, they also struggled with meaningfulness (‘What kind of answers should we give students when they say: ‘why do I have to learn this?’ ‘Why will this be useful in my future?’’) and authenticity, (‘How do you get the student who always fights what you are trying to do and not being interested just to be difficult, to really get into a project and have it become authentic for them?’). At this point in the semester, they appeared to view authenticity as something that could be layered onto a project, or that students might be tricked into. As a foil to this, the open, online community in which they posted their design work and reflections was discussed. The teachers commented that though they sometimes felt uncomfortable with this, it pushed them to submit work of which they were proud.

By the end of the semester, both the projects they designed (see examples in Table 4) and the collaborative notes, which reflect in-class discussion, show that the teachers had developed a deeper understanding of project-based instruction (collaborative notes, 4/18/2012 & 4/25/2012). All students created units that were aligned to PBL principles from course readings, such as providing context, being standards-based and supporting collaboration (Singer et al. 2000).

They tied their plans for implementing projects to (a) a deeper understanding of learning; (b) confidence in their ability to change their own instruction; and (c) a willingness to advocate for project based learning (collaborative notes, 4/18/2012 & 4/25/2012). For instance, one teacher explained, ‘I am confident that I could design a project for a class and explain why the usefulness of PBL is better than worksheets or repetition.’ Another teacher explained, ‘I started just thinking there has to be more for my Science class because I was following someone else’s curriculum… Now I have more confidence in changing and shaking things up a bit. I try new things with the students and I see that they really respond to new ideas, especially if they pertain to projects. This class has helped me to be creative and really think about the way my students learn.’

Case 2. Knowledge building professional development

The KBC model has Knowledge Building Discourse as one of the core principles. Discourse in the study groups often took the form of knowledge building and on several occasions during the study was identified as such by the participating teachers. Use of the online KF database for the teachers’ design work was more difficult compared to getting the teachers to discuss their design issues face-to-face. Groups at both sites reported that they collaborated less in the online KF database because of their expectation that their issues could be dealt with at upcoming face-to-face study group meetings. The teachers often brought forward the contextual constraints while the university researcher often told stories of use related to previous implementations of the KBC model. The stories told were coded as global—stories about how others had addressed a design problem in the past, projective—stories about how a specific design problem could be addressed in the current situation, and contextual—stories about the local context (e.g., students, technology and schedule). Along with general questions that sought information (e.g., about the context), a separate class of questions—generative design questions (Eris 2003) were also coded; these questions asked about possible ways of addressing the design dilemmas that were identified during the design study group meetings. Both the teachers and the university researcher offered projective stories. For illustrative purposes, the focus here is on the functioning of the study group at Site II and the changes that occurred for the participants at that site.

A pattern of discourse was identified that included the KBC principles and the contextual constraints often leading to a commitment to try something out in the classroom by one or more of the teachers; this is a pattern that was repeatedly found in the discourse of the study group at Site I and emerged over the course of the six study group meetings at Site II. Kelly and Alice at Site II specifically noted the discourse in the fourth meeting as being pivotal to changes that they made both to their classroom practices and to their beliefs about the KBC model.

Throughout the series of study group meetings, the teachers at Site II focused their attention on design problems related to the identified KBC principles (e.g. How to encourage the right (KB) discourse). As was the case at Site I, contextual constraints related to the implementation of the KBC model were identified and these were also engaged as design problems. In the case of Site II these included, for example, the abilities of the elementary students to view their ideas as improvable and to find ways to deal with the availability of computers in the school. At several points in the meeting and interview transcripts it is clear that two of the teachers at Site II (Alice and Kelly) viewed the contextual constraints as limiting their ability to implement the KBC model in the manner that they understood the KBC principles were directing them to do. These issues were discussed during the design study group meetings and then these two teachers each committed to make a change in their classroom implementation that they reported back to the group at the following meeting. The other teacher, Chris, did not anticipate contextual constraints and was much more focused on the use of the KF database as a way of supporting her existing practices. Repeatedly in the transcripts, Chris focused her attention away from the KBC principles and instead toward the KF software. However, Alice and Kelly framed the conversation in terms of the KBC principles and the local contextual constraints they had identified (Reeve 2012).

Teachers who experimented with their classroom designs and made adaptations also modified their beliefs; they were able to design an implementation that was more favorable to the KBC model. From the post interviews and class database results it is clear that Kelly and Alice engaged in practices that led them to modify their underlying understanding of the KBC model and the associated principles. However, Chris focused less on the KBC principles and managed only to assimilate surface features of the approach into her beliefs and practices. Specifically, Chris framed the problem not in terms of designing with the KBC principles and contextual constraints but instead she focused on the surface issues of using the KF software to support her existing teaching practices. As such her underlying beliefs remained mostly unchanged at the end of the study. Finally, both teachers at Site I engaged in principle-focused meeting discourse and committed to engage in classroom experimentation regarding their concerns about their designs. At Site I both the teachers reported a deeper understanding of the Rise Above principle after their active attempts to improve the role of this principle in their classroom implementation of the KBC model.

Case 3. Teachers as design-researchers program

Figure 3 shows teachers’ views about the relevance of design and design-research to their professional development based on the open-ended question on the questionnaire. The figure illustrates that at preliminary stages of their participation in the program, teachers tended to value design much more than design-research as a potential contributor to their professional development. At preliminary stages, significant differences were found between the way they viewed the relevancy of ‘design’ skills compared to the way they viewed ‘design-research’ skills to their practice (t(58) = 3.22, p < 0.005). These views changed dramatically towards the end of the program, with a significant rise in the way they viewed the relevancy of ‘design-research’ skills to their practice (t(60) = 3.66, p < 0.001).

The contents of the answers indicate that at early stages of their participation in the program, teachers tended to view design research as an activity totally unrelated to their everyday professional practices—an activity which is conducted mainly in the ivory tower of academia. For instance, one teacher explained, ‘Since this is a new field, it is important that researchers will find out how people learn in an environment that integrates technology.’ In fact, some teachers even viewed design research and teaching as competing enterprises. These views changed dramatically towards the end of the program. In the post questionnaires teachers’ explanations reveal the major change in their perceptions towards the relevance of design-research for their practice and professional development. We also identified many instances that suggested a change in teachers professional identity as expressed in the following excerpt ‘This program provided me with a lifelong moral, that a good teacher must be a researcher. As a teacher-researcher I was able to see things that I wasn’t able to see before as a teacher’.

Discussion

In an era in which teachers are increasingly adopting the role of designer as part of their practice (Laurillard 2012) it is imperative that they also develop a professional identity that will encourage them and provide them with tools to analyze how their designing impacts learners. Therefore, it is important to understand ways to support teacher-designer’s learning—the development of design identities, practices, understandings and beliefs. Our designs for teachers provided opportunities for the teachers to learn about design processes, to develop identities as designers, and to apply designing within practice. As described above, the ‘fingerprint pattern’ we identified by contrasting and comparing three very different cases consists of supporting teachers to design through (a) modeling practice, (b) supporting dialogue, (c) scaffolding design process, and (d) asking teachers to design for real-world use; fingerprints, while unique in their specific arches, loops and whorls, all possess ridge patterns. The metaphor of a fingerprint pattern aided us to consider both the uniqueness of each setting while still identifying similar ‘ridge patterns’—in this case, supports for teacher’s designing (Fig. 4).

Modeling practice

Our pedagogical agendas, although guided by different specific theoretical frameworks or approaches (e.g., KBC model), were in many ways quite similar; all brought a focus on authenticity, generativity and learner-centeredness. Technology was used as a tool to push the agenda forward and not as the main goal. We modeled learner-centered practice and encouraged use of technologies in learner-centered ways.

Supporting dialogue

Across cases, we supported dialogue within the teacher community, viewing its crucial role in learning as suggested by Putnam and Borko (2000). By modeling dialogue in our supports for teacher learning, we hoped teachers would take it up in their designs for their own students.

Scaffolding design process

In the Knowledge Building professional development case (case 2) and the TaDR program (case 3), there was also a focus on design principles, finding that design principles did not serve as sufficient guidance on their own. In the project-based course (case 1), specific design tools (e.g., needs assessment) scaffolded teachers’ design work, supporting them to develop connections between the research they were reading and the designing they were doing for their own classrooms.

Design for real-world use

Across cases, we maintained a commitment to designing for particular contexts and testing these designs in the world. Asking teachers to design for their classrooms respects their knowledge of context as well as the situative aspect of their learning (Putnam and Borko 2000). In professional design contexts, designs are iteratively improved and evaluated against identified needs. In our approach, teachers prototyped their designs, evaluated their designs, and tested their designs in the world.

With these supports, our collective findings show that we encouraged the evolution of teachers’ beliefs, practices, understandings and professional identities. Across cases, the teachers began with teacher-centered practices, though they were inclined toward learner-centered practices. Engaging teachers as designers introduced a change in the way teachers viewed themselves. We specifically found two major changes: (a) a deep understanding of the student-centered pedagogies and belief in the merits of such pedagogies; and (b) change in the professional identity of teachers. These outcomes relate to teachers who are improved designers, whether evidenced through changes in their discourse around designing, or understanding of place of design in their work. They indicate success in advancing teachers’ work as designers; the learning we observed was designerly.

Deep understanding of pedagogy

In case 1, teachers in the Project-Based Learning course designed project-based units that evidenced understanding of the pedagogical approach as deeper and more complex than simply ‘hands-on’. A single semester is a relatively short period of time to see lasting change, but the findings show that by using design tools and processes and engaging in discussion, the teachers developed a much more student-centered stance in their designs by the end of the semester. In case 2, teachers in the Knowledge Building professional development program engaged in collaborative professional inquiry regarding the design of their classroom instantiations of the KBC model. Direct focus on designing during study group meetings contributed to changes in teachers’ understandings about the underlying pedagogical approach and related classroom practices. Findings show that due to the intervention, Site I teachers were more open to exploring the aspects of the pedagogy that they had not previously been able to find a way to implement and as such, reported changes in their understanding of the underlying principles. Two of the Site II teachers (Alice and Kelly) deepened their understanding of the pedagogy as defined through the principles through participation in the design study group meetings and through their efforts to experiment with the model in the reality of their local classroom context.

Professional identity

In case 1, teachers began with limited understanding of design process and design tools and gradually developed designerly ways of thinking as they took up identities as designers. In case 2, teachers developed patterns of discourse that focus around design problems and contextual constraints related to implementation. These discussions lead to experimenting in the classroom and reporting back to the group to get feedback and experiment again. By understanding identity as constructed through talk and interaction (Fina 2012; Holland et al. 1998), we see these changes in discourse as evidence of development of their professional identities as designers. In case 3, the participation in the TaDR program changed the way teachers perceived their professional identity. The dramatic rise in teachers’ views regarding the relevance of design-research to their everyday professional indicates that the TaDR approach was effective. By modeling and gradually involving teachers in the three roles (mentor, designer, and design-researcher) throughout the three courses, the teachers not only developed the skills required to conduct a small-scale design-research, but also adopted a professional identity in which design-research plays a critical role.

We began by positioning designing as a central piece of teacher practice, from pre-instructional designing to designing that continues into the classroom (Schön 1983, 1987, 1992; Minstrell et al. 2011). This stance underscores the importance of understanding how to support teachers to not only make adaptations to curricula but also to design new technology-enhanced learning experiences. Our cross-case analysis shows that across our studies, teachers were provided with an opportunity to take a designer’s role, and this made visible the types of learning from design courses: shifting in their beliefs, deeper understandings, and development of professional identities and practices. This study indicates that although our three interventions were very different, they all succeeded in helping teachers develop as designers of technology-enhanced learning.

Teacher-designed materials might not be as polished as those developed by teams of researchers and curriculum/instructional designers. In particular, how teachers frame the problem is not always in our control, and in cases, can lead to implementations or designs that differ from what we envisioned. For instance, one of the teachers in case 2 framed the problem using surface features rather than the KBC principles and contextual constraints. We’re not expecting teachers to develop all the technology-enhanced learning experiences for their students, of course. But since they are developing some of these experiences (Laurillard 2012) it’s important to characterize main constructs of the supports that they get, and the types of learning that these supports encourage. We believe that the identified ‘fingerprint pattern’—the combination of modeling practice, supporting dialogue, scaffolding design process, and real-world design—is important to this success. We view this ‘fingerprint pattern’ as integral to successful designing by teachers when the pedagogical approach or technology they are designing for is relatively new or complex. However, we also acknowledge the limitations endemic to working with teachers who may be particularly invested in innovative approaches to instruction. Our findings should be transferrable to other settings in which participation is elective, but future work should investigate the degree to which our findings are applicable for teachers who are participating in professional development by mandate, rather than by choice. For instance, in the current reforms under way in the US related to the Common Core State Standards, there is a high degree of resistance related to a variety of factors; this resistance could prevent teachers from learning about a pedagogical approach through dialogue, and could lead them to engage in designing in superficial ways. Under such conditions, we would not expect to see professional identity development. Thus, in mandated professional development, we suspect there could be additional supports needed.

Professional development commonly involves modeling practice and supporting dialogue, and to a lesser degree, designing for real world use. By also scaffolding design process, there is potential for different types of dialogue focused more on how to design for learning and greater access to teachers’ understanding of the particular pedagogical approach. Future research could investigate the types of dialogue when design process is or is not scaffolded, and when design work is or is not intended to be used in the real world.

By better understanding how to support teachers to be designers, we address the implementation gap between the context in which an innovation is developed and where it is to be implemented (Supovitz and Weinbaum 2008). Looking across three very different settings allowed us to characterize a ‘fingerprint pattern’ of supports that can foster deeper learning of educational innovations and shifts in professional identities. As previously noted, the former is a key concern for crossing the implementation gap (Spillane et al. 2002), and the latter addresses many of the challenges noted in common approaches to designing with teachers in which they hold a relatively minor role (Bencze and Hodson 1999; Penuel and Gallagher 2009).

References

Akerson, V. L., & Hanuscin, D. L. (2007). Teaching nature of science through inquiry: Results of a 3-year professional development program. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 44(5), 653–680.

Akerson, V. L., Hanson, D. L., & Cullen, T. A. (2007). The influence of guided inquiry and explicit instruction on K–6 teachers’ views of nature of science. Journal of Science Teacher Education, 18(5), 751–772.

Barab, S. A., & Luehmann, A. L. (2003). Building sustainable science curriculum: Acknowledging and accommodating local adaptation. Science Education, 87(4), 454–467.

Basista, B., & Mathews, S. (2010). Integrated science and mathematics professional development programs. School Science and Mathematics, 102(7), 359–370.

Ben-Chaim, D., Joffe, N., & Zoller, U. (1994). Empowerment of elementary school teachers to implement science curriculum reforms. School Science and Mathematics, 94(7), 356–366.

Bencze, L., & Hodson, D. (1999). Changing practice by changing practice: Toward more authentic science and science curriculum development. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 36(5), 521–539.

Blanchard, M. R., Southerland, S. A., & Granger, E. M. (2008). No silver bullet for inquiry: Making sense of teacher change following an inquiry-based research experience for teachers. Science Education, 93(2), 322–360.

Blumenfeld, P. C., Soloway, E., Marx, R. W., Krajcik, J. S., Guzdial, M., & Palincsar, A. S. (1991). Motivating project-based learning: Sustaining the doing, supporting the learning. Educational Psychologist, 26(3), 369–398.

Blumenfeld, P. C., Fishman, B. J., Krajcik, J. S., Marx, R. W., & Soloway, E. (2000). Creating usable innovations in systemic reform: Scaling up technology-embedded project-based science in urban schools. Educational Psychologist, 35(3), 149–164.

Brickhouse, N., & Bodner, G. M. (1992). The beginning science teacher: Classroom narratives of convictions and constraints. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 29(5), 471–485.

Brown, A. L., & Campione, J. C. (1994). Guided discovery in a community of learners. In K. McGilly (Ed.), Classroom lessons: Integrating cognitive theory and classroom practice (pp. 229–270). Cambridge: MIT Press/Bradford Books.

Bryan, L. A., & Abell, S. K. (1999). Development of professional knowledge in learning to teach elementary science. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 36(2), 121–139.

Capps, D. K., Crawford, B. A., & Constas, M. A. (2012). A Review of empirical literature on inquiry professional development: Alignment with best practices and a critique of the findings. Journal of Science Teacher Education, 23, 1–28.

Chi, M. T. H. (1997). Quantifying Qualitative analyses of verbal data: A practical guide. The Journal of the Learning Sciences, 6(3), 271–315.

Clandinin, D. J., & Connelly, F. M. (1992). Teacher as curriculum maker. In P. W. Jackson (Ed.), Handbook of research on curriculum (pp. 363–401). New York: Macmillan.

Cober, R., Tan, E., Slotta, J., So, H. J., & Könings, K. D. (2015). Teachers as participatory designers: Two case studies with technology-enhanced learning environments. Instructional Science. doi:10.1007/s11251-014-9339-0.

Cohen, D. K., & Hill, H. C. (2001). Learning policy: When state education reform works. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Creswell, J., & Clark, V. (2007). Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications Inc.

Cviko, A., McKenney, S., & Voogt, J. (2012). Teachers as (re-) designers of an ICT-rich learning environment for early literacy.

Davis, E. A., & Varma, K. (2008). Supporting teachers in productive adaptation. In Y. Kali, M. C. Linn, M. Koppal, & J. Roseman (Eds.), Designing coherent science education: Implications for curriculum, instruction, and policy (pp. 94–122). NY: Teachers College Press.

Deketelaere, A., & Kelchtermans, G. (1996). Collaborative curriculum development: An encounter of different professional knowledge systems. Teachers and Teaching, 2(1), 71–85. doi:10.1080/1354060960020106.

Dorst, K., & Cross, N. (2001). Creativity in the design process: Co-evolution of problem-solution. Design Studies, 22(5), 425–437.

Ehn, P. (1993). Scandinavian design: On participation and skill (pp. 41–77). Participatory design: Principles and practices.

Eilks, I., Parchmann, I., Gräsel, C., & Ralle, B. (2004). Changing teachers’ attitudes and professional skills by involving teachers into projects of curriculum innovation in Germany. In B. Ralle & I. Eilks (Eds.), Quality in practice oriented research in science education (pp. 29–40). Aachen: Shaker.

Eris, O. (2003). Asking generative design questions: a fundamental cognitive mechanism in design thinking. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Engineering Design. Stockholm.

Fina, A. D. (2012). Discourse and identity. In C. A. Chapelle (Ed.), The encyclopedia of applied linguistics. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Fishman, B., Marx, R., Best, S., & Tal, R. (2003). Linking teacher and student learning to improve professional development in systemic reform. Teaching and Teacher Education, 19(6), 643–658.

Geier, R., Blumenfeld, P. C., Marx, R. W., Krajcik, J. S., Fishman, B., Soloway, E., et al. (2008). Standardized test outcomes for students engaged in inquiry-based science curricula in the context of urban reform. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 45(8), 922–939.

Glaser, B. G. (1965). The constant comparative method of qualitative analysis. Social Problems, 12, 436–445.

Hansen, S. E. (1998). Preparing student teachers for curriculum-making. Journal of curriculum studies, 30(2), 165–179.

Hashweh, M. Z. (1996). Effects of science teachers’ epistemological beliefs in teaching. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 33(1), 47–63.

Hiller, N. A. (1995). The battle to reform science education: Notes from the trenches. Theory into Practice, 43(1), 60–65.

Holland, D., Lachicotte, W., Skinner, D., & Cain, C. (1998). Identity and agency in cultural worlds. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ Press.

Hoogveld, A. W. M., Paas, F., Jochems, W. M. G., & Van Merrienboer, J. J. G. (2002). Exploring teachers’ instructional design practices from a systems design perspective. Instructional Science, 30(4), 291–305.

Hyett, N., Kenny, A., & Virginia Dickson-Swift, D. (2014). Methodology or method? A critical review of qualitative case study reports. International journal of qualitative studies on health and well-being, 9, 23606.

Johnson, C. C. (2007). Whole-school collaborative sustained professional development and science teacher change: Signs of progress. Journal of Science Teacher Education, 18(4), 629–661.

Johnson, C. C., Kahle, J. B., & Fargo, J. D. (2007). A study of the effect of sustained, whole-school professional development on student achievement in science. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 44(6), 775–786.

Jonassen, D. H. (2000). Toward a design theory of problem solving. Educational Technology Research and Development, 48(4), 63–85.

Kali, Y. (2006). Collaborative knowledge building using the design principles database. International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 1(2), 187–201. doi:10.1007/s11412-006-8993-x.

Kali, Y., & Ronen-Fuhrmann, T. (2011). Teaching to design educational technologies. International Journal of Learning Technology, 6(1), 4–23.

Kali, Y., Levin-Peled, R., & Dori, Y. J. (2009). The role of design-principles in designing courses that promote collaborative learning in higher-education. Computers in Human Behavior, 25(5), 1067–1078.

Kali, Y., Markauskaite, L., Goodyear, P., & Ward, M.-H. (2011). Bridging multiple expertise in collaborative design for technology-enhanced learning. In H. Spada, G. Stahl, N. Miyake, & N. Law (Eds.), Proceedings of the computer supported collaborative learning (CSCL) conference (pp. 831–835). Hong Kong: International Society of the Learning Sciences.

Keys, C. W., & Bryan, L. A. (2001). Co-constructing inquiry-based science with teachers: Essential research for lasting reform. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 38(6), 631–645.

Krajcik, J. S., Blumenfeld, P. C., Marx, R., Bass, K., Fredricks, J., & Soloway, E. (1998). Inquiry in project-based science classrooms: Initial attempts by middle school students. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 7(3), 313–350.

Lakkala, M., Lallimo, J., & Hakkarainen, K. (2005). Teachers’ pedagogical designs for technology-supported collective inquiry: A national case study. Computers & Education, 45(3), 337–356.

Laurillard, D. (2012). Teaching as a design science: Building pedagogical patterns for learning and technology. London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group. 258.

Luehmann, A. L. (2002). Understanding the appraisal and customization process of secondary science teachers. Paper presented at the Annual meeting of the American Educational Research Association, New Orleans.

Lynch, S. (1997). Novice teachers’ encounter with national science education reform: Entanglements or intelligent interconnections? Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 34(1), 3–17.

Marx, R. W., Blumenfeld, P. C., Krajcik, J. S., & Soloway, E. (1997). Enacting project-based science. The Elementary School Journal, 97, 341–358.

Matuk, C. F., Linn, M. C., & Eylon, B. S. (2015). Technology to support teachers using evidence from student work to customize technology-enhanced inquiry units. Instructional Science. doi:10.1007/s11251-014-9338-1.

McKenney, S., Kali, Y., Markauskaite, L., & Voogt, J. (2015). Teacher design knowledge for technology enhanced learning: An ecological framework for investigating assets and needs. Instructional Science. doi:10.1007/s11251-014-9337-2.

Merriam, S. B. (1998). Qualitative research and case study applications in education. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Merriam, S. B. (2014). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation. San Francisco: Wiley & Sons.

Minstrell, J., Anderson, R., & Li, M. (2011). Building on learner thinking: A framework for assessment in instruction. Commissioned paper for the Committee on Highly Successful STEM Schools or Programs for K-12 STEM Education.

Muller, M. J., & Kuhn, S. (1993). Participatory design. Communications of the ACM, 36(6), 24–28.

O’Connor, M. C., Godfrey, L., & Moses, R. P. (1998). The missing data point: Negotiating purposes in classroom mathematics and science. In J. Greeno & S. Goldman (Eds.), Thinking practices in mathematics and science learning (pp. 89–125). Mahwah: Erlbaum.

Parke, H. M., & Coble, C. R. (1997). Teachers designing curriculum as professional development: A model for transformational science teaching. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 34(8), 773–789.

Penuel, W. R., & Yarnall, L. (2005). Designing handheld software to support classroom assessment: Analysis of conditions for teacher adoption. The Journal of Technology, Learning and Assessment, 3(5), 3–45.

Penuel, W. R., & Gallagher, L. P. (2009). Preparing teachers to design instruction for deep understanding in middle school earth science. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 18(4), 461–508.

Putnam, R. T., & Borko, H. (2000). What do new views of knowledge and thinking have to say about research on teacher learning? Educational Researcher, 29(1), 4–15.

Reeve, R. (2012). Supporting the implementation of the knowledge building communities model: Analysis of principle-based study group interactions. Paper presented at the American Educational Research Association, Vancouver.

Reiser, B. J., Spillane, J. P., Steinmuller, F., Sorsa, D., Carney, K., & Kyza, E. (2000). Investigating the mutual adaptation process in teachers’ design of technology-infused curricula. In B. Fishman & S. O’Connor-Divelbiss (Eds.), Proceedings of the fourth international conference of the learning sciences (pp. 342–349). Mahwah: Erlbaum.

Roschelle, J., & Penuel, W. R. (2006). Co-design of innovations with teachers: Definition and dynamics. In S. Barab, K. E. Hay, & D. T. Hickey (Eds.), Proceedings of the 7th international conference on learning sciences (pp. 606–612). Bloomington: International Society of the Learning Sciences.

Ruiz-Primo, M. A. (2006). A multi-method and multi-source approach for studying fidelity of implementation. CSE Report 677: Regents of the University of California.

Scardamalia, M. (2002). Collective cognitive responsibility for the advancement of knowledge. In B. Smith (Ed.), Liberal education in a knowledge society (pp. 67–98). Chicago: Open Court.

Sagy, O., & Kali, Y. (2014). Teachers as Design-Researchers. Paper presented at the American Educational Research Association (AERA) conference, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Schön, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. New York: Basic Books.

Schön, D. A. (1987). Educating the reflective practitioner. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Schön, D. A. (1992). Designing as reflective conversation with the materials of a design situation. Research in Engineering Design, 3(3), 131–147.

Shrader, G., Williams, K., Lachance-Whitcomb, J., Finn, L. E., & Gomez, L. (2001). Participatory design of science curricula: The case for research for practice. Paper presented at the American Educational Researchers’ Association, Seattle, WA.

Singer, J., Marx, R., Krajcik, J. S., & Clay Chambers, J. (2000). Constructing extended inquiry projects: Curriculum materials for science education reform. Educational Psychologist, 35(3), 165–178.

Spillane, J. P., Reiser, B. J., & Reimer, T. (2002). Policy implementation and cognition: Reframing and refocusing implementation research. Review of Educational Research, 72(3), 387–431.

Stake, R. E. (2008). Case studies. In N. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Strategies of qualitative inquiry (pp. 119–150). Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Supovitz, J. A., & Weinbaum, E. H. (2008). The implementation gap: Understanding reform in high schools. New York: Teachers College Press.

Svihla, V., Petrosino, A. J., Martin, T., & Diller, K. R. (2009). Learning to design: Interactions that promote innovation. In W. Aung, K.-S. Kim, J. Mecsi, J. Moscinski, & I. Rouse (Eds.), Innovations 2009: World innovations in engineering education and research (pp. 375–391). Arlington: International Network for Engineering Education and Research.

Svihla, V. (2010). Collaboration as a dimension of design innovation. CoDesign, 6(4), 245–262.

Svihla, V., Kvam, N., Dahlgren, M., Bowles, J., & Kniss, J. (2013). We can’t just go shooting asteroids like space cowboys: The role of narrative in immersive, interactive simulations for learning. In C. C. Williams, A. Ochsner, J. Dietmeier, & C. A. Steinkuehler (Eds.), Proceedings of games, learning, society 9. Madison: ETC Press.

Svihla, V., Knottenbelt, S., & Buntjer, J. (2014). Problem framing: Learning through designerly practices. Paper presented at the AERA, Philadelphia, PA, April 3–7.

Talbert, J. E., & McLaughlin, M. W. (1999). Assessing the school environment: Embedded contexts and bottom-up research strategies. In S. L. Friedman & T. D. Wachs (Eds.), Measuring environment across the life span: Emerging methods and concepts (Vol. xvii, pp. 197–227). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Vermunt, J. D., & Verloop, N. (1999). Congruence and friction between learning and teaching. Learning and Instruction, 9(3), 257–280.

Voogt, J., Laferrière, T., Breuleux, A., Itow, R. C., Hickey, D. T., & McKenney, S. (2015). Collaborative design as a form of professional development. Instructional Science. doi:10.1007/s11251-014-9340-7.

Walton, J. (1992). Making the theoretical case. In C. Ragin & H. Becker (Eds.), What is a case? Exploring the foundations of social inquiry (pp. 121–138). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Acknowledgments