Abstract

Although providing feedback is commonly practiced in education, there is no general agreement regarding what type of feedback is most helpful and why it is helpful. This study examined the relationship between various types of feedback, potential internal mediators, and the likelihood of implementing feedback. Five main predictions were developed from the feedback literature in writing, specifically regarding feedback features (summarization, identifying problems, providing solutions, localization, explanations, scope, praise, and mitigating language) as they relate to potential causal mediators of problem or solution understanding and problem or solution agreement, leading to the final outcome of feedback implementation. To empirically test the proposed feedback model, 1,073 feedback segments from writing assessed by peers was analyzed. Feedback was collected using SWoRD, an online peer review system. Each segment was coded for each of the feedback features, implementation, agreement, and understanding. The correlations between the feedback features, levels of mediating variables, and implementation rates revealed several significant relationships. Understanding was the only significant mediator of implementation. Several feedback features were associated with understanding: including solutions, a summary of the performance, and the location of the problem were associated with increased understanding; and explanations of problems were associated with decreased understanding. Implications of these results are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Although giving feedback is a generally accepted practice in educational settings, specific features of effective feedback, such as the complexity (i.e., more versus less information) and timing (i.e., immediate versus delayed) of feedback, have been largely disputed (see Mory 2004; 1996 for review). Moreover, for a complex task such as writing, the conditions that influence feedback effectiveness are likely to be correspondingly complex. An understanding of the conditions under which writers implement feedback they receive is critical to promoting improved writing. The goal of the present study is to identify some of these conditions, based on the hypothesis that specific mediators allow external features to influence the writer’s implementation of feedback. We are particularly interested in the case of peer feedback. Peers are increasingly used as a source of feedback, both in professional and instructional settings (Toegel and Conger 2003; Haswell 2005). Advice regarding useful peer feedback is particularly lacking.

Beyond the specific focus of feedback in writing, there is a long, more general history of research on feedback. Overall, three broad meanings of feedback have been examined (Kulhavy and Wager 1993). First, in a motivational meaning, some feedback, such as praise, could be considered a motivator that increases a general behavior (e.g., writing or revision activities overall). This piece of the definition came from the research that tried to influence the amount of exerted effort through motivation (Brown 1932; Symonds and Chase 1929). Second, in a reinforcement meaning, feedback may specifically reward or punish very particular prior behaviors (e.g., a particular spelling error or particular approach to a concluding paragraph). This piece of the definition came from the Law of Effect (Thorndike 1927). Third, in an informational meaning, feedback might consist of information used by a learner to change performance in a particular direction (rather than just towards or away from a prior behavior). This piece of the definition came from information-processing theories (Pressey 1926, 1927). In the context of writing, all three elements may be important and will be examined, although the informational element is particularly important and will be examined in the most detail. Note, however that the reinforcement element of writing feedback is more complex than what the behaviorists had originally conceived. For example, comments may not actually reward or punish particular writing behaviors if the author does not agree with the problem assessment.

A distinction between performance and learning should be made for considering the effects of feedback in writing, as well as in other domains. Learning is the knowledge gain observed on transfer tasks (i.e., application questions; new writing assignments). Performance is the knowledge gain observed on repeated tasks (i.e., pre-post multiple-choice questions; multiple drafts of the same writing assignment). Learning and performance can be affected differently by feedback. For example, feedback without explanations can improve performance, but not learning (Chi et al. 1989) and the use of examples can influence whether feedback affects learning or performance or both (Gick and Holyoak 1980; 1983). The focus here is specifically on writing performance. Examining performance is a necessary first step because if effects of performance are not found, effects of transfer are also not likely to be found. For writing, a context in which the effect of feedback on performance or learning has not been rigorously studied, performance is the best place to start. As noted by Newell and Simon (1972), “if performance is not well understood, it is somewhat premature to study learning” (p. 8).

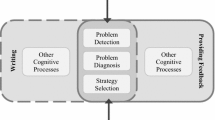

As one goes into a particular domain, more specific types of feedback need to be addressed. Therefore, a specific model of feedback, for the case of writing performance, is being proposed (see Fig. 1). In describing this model, the next section identifies several feedback features relevant to writing whose effects will need to be teased apart in the current study.

Feedback features

The writing education and writing research literatures have discussed a number of feedback features. We examined five of them in the current study: (1) summarization, (2) specificity, (3) explanations, (4) scope, and (5) affective language. These features could be considered psychologically different—summarization, specificity, explanations, and scope are cognitive in nature, while affective language is by definition affective in nature (as indicated by the groupings in Fig. 1). These distinctions between cognition and affect will be important when considering how the mediators influence feedback implementation. Another important point is that the studies of feedback in writing focus on performance defined as writing quality. While writing quality is very important, there is likely to be an intermediate step that leads to writing quality changes: feedback implementation. This measurement of performance was the focus of the current study.

Summaries

Sometimes feedback may include summary statements, which condense and reorganize the information pertaining to a particular behavior into chunks. These statements could focus on various aspects, such as the correct answer, the action taken, or the topic or claim discussed. The following examples illustrate two possibilities in writing:

Topic: “You used the experiences of African Americans, women, and immigrants from Asia as support for your thesis.”

Claim: “Your thesis was that the US became more democratic during the 1865–1924 time period even though it had ups and downs.”

As the complexity of the task increases, as in writing, more memory resources become occupied. Useful summaries provide an organizing schema by chunking information into more manageable components (Bransford et al. 2003). Summary feedback could also be used to help determine whether the actual performance was the same as the intended performance. For example, as a motor skill becomes automatic, a person may not realize that a mistake is being made. Finally, summary feedback could provide an additional opportunity to detect an overlooked mistake.

Receiving summaries has previously been found to benefit performance: when college students received summaries about their writing, they made more substantial revisions (Ferris 1997). Therefore, receiving summaries in feedback is expected to promote more feedback implementations.

Specificity

Feedback specificity refers to the details included in the feedback. Feedback specificity also varies along a continuum that begins with outcome feedback only (whether an action was right or wrong) to highly specific (explicitly identifying problems, their location and providing solutions). Specific comments have been found to be more helpful than general comments in writing tasks (Ferris 1997). Three components of specificity are examined (as indicated by the grouping in Fig. 1): problem identification, providing solutions, and indicating the location of the problem and/or solution. Of course, providing a solution and indicating its location could only occur if a problem existed. However, only explicit problems are analyzed here—a problem could just be implied when giving the solution and location. Looking at problems separately helps to tease apart the individual effects of the remaining components.

Identification of the problem

One component of feedback specificity is identifying the problem. A problem is defined here as a criticism that is explicitly acknowledged. Students have difficulty detecting global problems (Hayes et al. 1987), but even third-graders are able to make global revisions when this type of problem is indicated (Matsumura et al. 2002). Therefore, identifying the problem explicitly may increase feedback implementation. If the problem is not explicitly stated, the writer may not know what the problem actually is. Including a problem in the feedback is expected to increase the likelihood of implementing the feedback.

Offering a solution

Solutions are another component of feedback specificity. A solution is defined as a comment that explicitly suggests a method to deal with a problem. Solutions provided in feedback, have previously been found to help writing performance with migrant adults studying English as a second language (Bitchener et al. 2005; Sugita 2006). However, when solutions were further divided into two categories, they had different effects on tenth-graders’ performance (Tseng and Tsai 2006). Solutions that provide advice for incompleteness were helpful between first and second drafts, but did not affect performance between second and third drafts. Solutions that directly corrected errors did not affect writing performance between first and second drafts, and hurt performance between second and third drafts. Overall across studies and solution-types, solutions were helpful as long as feedback was provided earlier in a task. Therefore, because the task in the current study only involves feedback between first and second drafts, including solutions is expected to increase feedback implementation.

Localization

A final component of feedback specificity is localization, which refers to pinpointing the source or location of the problem and/or solution. This type of feedback also is typically part of the pragmatic recommendations for appropriate feedback to be provided to college students (Nilson 2003). By specifying the location of a problem, a person gets a second opportunity to detect a problem that may have previously been overlooked. Identifying the location is particularly relevant in lengthy writing assignments where there are many locations in which a problem could occur. If the feedback includes the location of the problem and/or solution, the writer may be more likely to implement the feedback.

Explanations

Again as the complexity of the task increases, feedback that includes explanations may become necessary. Explanations are statements that provide motives or clarification of the feedback’s purpose. For example, a reviewer may suggest, “Delete the second paragraph on the third page”, but without the explanation, “because it interrupts the flow of the paper”, the writer may not take the suggestion because he or she does not know why it is a necessary revision.

The impact of explanations on performance has had a mixed history. While providing explanations to feedback during a 5-min conference with the instructor improved migrant adults’ writing performance (Bitchener et al. 2005), lengthy explanations for errors provided by peers hurt tenth-graders’ performance between writing drafts (Tseng and Tsai 2006). Tseng and Tsai’s finding was particularly surprising because providing explanations is intuitively helpful. One difference between these studies that may account for the surprising result is who provides the explanations. In Tseng and Tsai, students may not be adept in providing helpful explanations. Therefore, because the current study also involves peer review, feedback that includes explanations is expected to be implemented less often.

Scope

The scope of the feedback (i.e., the continuum of levels, ranging from local to global, to which the feedback refers) is likely to affect feedback implementation. A more local level is defined as utilizing a narrow focus during evaluation (e.g., focusing on surface features). A more global level is defined as a holistic examination of the performance or product. The following examples illustrate the differences between local and global feedback:

Local: “You used the incorrect form of ‘there’ on page 3. You need to use ‘their’.”

Global: “All of your arguments need more support.”

Global feedback has been associated with better performance in college students (Olson and Raffeld 1987), and yet local feedback has also been associated with better performance in college students (Lin et al. 2001; Miller 2003). The difference between implementation and quality may be relevant here, with global feedback perhaps having a greater possible effect on overall quality if implemented, but more local feedback being perhaps more likely to be implemented. The current study examined the effects of feedback on implementation, not writing quality. Matsumura et al. (2002) found that the scope of the feedback did not affect whether it was implemented. If third-graders received local feedback, they were more likely to make local revisions. If they received global feedback, they were more likely to make global revisions. However, it is important to note that the participants in that study were third-graders. As a student progresses into college level writing, the global issues may be more likely to be complex. For example, consider how the complexity in organization or connections in content that a third-grade writing assignment that typically consisted of a one paragraph narrative, expository, or personal text (such as a diary entry) differs from the five to eight page paper typically assigned in a college level course. In addition to the length of the assignment differing between younger and older students, the concepts they learn become more complex. The content of third-grade writing assignments focused on information they already know (i.e. What I did for my summer vacation). On the other hand, the content of college writing assignments involve new concepts and how they are related to each other.

As the scope of the feedback increases, the writer is expected to be less able to implement the feedback as a result of the complexity of the global issues.

Affective language

Feedback can consist of criticism, praise, or summary. When criticizing, reviewers may make use of affective language, or statements reflecting emotion, which may influence the implementation of feedback. Affective language in feedback includes praise standing alone, inflammatory language, and mitigating language applied to criticisms/suggestions. Inflammatory language is defined as criticism that is no longer constructive, but instead it is insulting. This type of language will not be considered further because it occurred about 0.5% of the time. While praise and mitigating language are similar, the main difference is that mitigating language also includes some criticism. Mitigation is often used to make the criticisms sound less abrasive. To make this distinction clearer, consider the following examples:

Praise: “The examples you provide make the concepts described clearer.”

Mitigation: “Your main points are very clear, but you should add examples.”

Praise is commonly included as one of the features to be included in feedback (Grimm 1986; Nilson 2003; Saddler and Andrade 2004). Even though some have found that praise helped college students’ writing performance between drafts, this finding seemed to be confounded, as the variable being measured included both praise and mitigating language (Tseng and Tsai 2006). A more typical finding is that praise almost never leads to changes in college students’ writing (Ferris 1997). In general, the effect size of praise is typically quite small (Cohen’s d = 0.09, Kluger and DeNisi 1996). Despite these findings, praise is still commonly highlighted in models of good feedback in educational settings. While praise has not been largely effective in previous research, it is included as a variable of analysis because of the frequent recommendations to include praise in feedback, especially in the writing context. Moreover, undergraduate peers are particularly likely to include praise in their feedback (Cho et al. 2006).

Mitigating language is also a common technique used by reviewers (Neuwirth et al. 1994; Hyland and Hyland 2001). Mitigating language in feedback was previously found to help college students’ writing performance between drafts (Tseng and Tsai 2006). Mitigated suggestions appear to affect the way a writer perceives the reviewer, such that the reviewer is considered to be more likable and have higher personal integrity (Neuwirth et al. 1994), at least in this study of faculty and graduate student reviewers. These attributes may increase the writers’ agreement with the statements made by that reviewer. On the other hand, mitigated suggestions have also confused college students studying English as a second language (Hyland and Hyland 2001). In addition to praise, the mitigated comments can include hedges, personal attribution, and questions. These other types of mitigation could affect performance in ways that contradict the typical results of mitigating feedback research. For example, other types of mitigated feedback such as questions were not found to be effective for college students studying English as a foreign language (Sugita 2006). Questions increased college students’ awareness that a problem may exist, but they were not sure how to revise (Ferris 1997).

Overall, the use of praise and mitigation in the form of compliments may augment a person’s perception of the reviewer and feedback, resulting in implementation of the rest of the feedback. Other forms of mitigation, such as questions or downplaying problems raised, could decrease the likelihood of implementation.

Feedback feature expectations

Based on the findings of previous studies, all of the mentioned variables are expected to influence implementation, although not always in a positive manner. First, some of the feedback features (i.e., summarization, feedback specificity, praise, and mitigation in the form of compliments) are expected to increase feedback implementation. Second, other feedback features (i.e., explanations, greater levels of scope, and mitigation in other forms such as questions and downplaying the problem) are expected to decrease feedback implementation. However, the main assumption of the current study is that none of these feedback features directly affect implementation, but instead do so through internal mediators because of the complex nature of writing performance. The next section describes these mediators.

Probable mediators

Except for possibly reinforcement feedback, feedback on complex behavior such as writing is likely to require some mediator to causally influence revision behavior. Understanding this causal relationship will lead to more robust theories of revision. There are a number of possible causal mediators for feedback-to-revision behaviors (i.e., changes traceable to feedback).

Four previous models offered explanations involving theoretical constructs that are essentially ideas about mediator of the effects of more concrete variables. First, Kluger and DeNisi (1996) argued that only feedback that directs attention to appropriate goals is effective. Similarly, Hattie and Timperly (2007) argued that only feedback at the process level (i.e., processes associated with the task) or self-regulation level (i.e., actions associated with a learning goal) is effective. Bangert-Drowns et al. (1991) argued that only feedback that encourages a reflective process is effective. Finally, Kulhavy and Stock (1989) argued that feedback is only effective when a learner is certain that his or her answer is correct and later finds out it was incorrect. While each of these explanations is plausible, we believe that different mediators may be more important in a writing context.

In contrast to these prior theoretical reviews, we seek to specifically measure mediators rather than posit abstract mediators from patterns of successful feedback features. Attention, self-regulation, and reflection are aggregate constructs (i.e., typically measured with a combination of component measures). We considered the following four reviews that seemed particularly relevant to complex tasks like writing: including understanding feedback (Bransford and Johnson 1972), agreement with feedback (Ilgen et al. 1979), memory load (Hayes 1996; Kellogg 1996; McCutchen 1996), and motivation (Hull 1935; Wallach and Henle 1941; Dweck 1986; Dweck and Leggert 1988). Only two of these factors were measurable using techniques that maintained the naturalistic environment of the current study: understanding feedback and agreement with feedback. Furthermore, memory load and motivation were examined in an unpublished pilot study but were not significantly related to any of the types of feedback or implementation. Therefore, two mediators are the focus of the current study (as indicated in Fig. 1).

Understanding is the ability to explain or know the meaning or cause of something. Understanding has been found to affect many facts of cognition, including memory and problem solving. For example, Bransford and Johnson (1972) showed that when a reader’s rating of understanding of a passage strongly influenced their ability to recall a passage. Similarly, deep understanding of problem statements relates to the ability to recall relevant prior examples (Novick and Holyoak 1991) and solve problems (Chi et al. 1989). Understanding could relate to writing feedback in at least two ways. First, it could relate to the decision to implement a concrete suggestion. Second, it could relate to the ability to instantiate a more abstract suggestion/comment into a particular solution. Therefore, increased understanding is expected to increase one’s likelihood of implementing the feedback (as indicated by the solid line in Fig. 1).

Agreement with the feedback refers to when the feedback message matches the learners’ perception of his or her performance (i.e., agreeing with the given performance assessment or perceiving the given suggestion will improve performance). Even the effect of reinforcement feedback might depend upon agreement with the problem described in the feedback. For example, Ilgen et al. (1979) proposed a four-stage model of feedback in which acceptance of the feedback was one of the first stages. Ilgen et al. examined a number of factors that influence acceptance (e.g., source of feedback, message characteristics, and individual differences). However, they merely theorized the importance of acceptance overall for implementation, rather than empirically investigating its importance. The current study will test whether agreement increases one’s likelihood of implementing feedback (as indicated by the solid line in Fig. 1).

Memory load is another important construct that is frequently mentioned in writing research (Hayes 1996; Kellogg 1996; McCutchen 1996). It is likely to be important for some aspects of the effects of feedback on writing given the high baseline memory workload associated with reading, writing, and revision and the high variability in length, amount, and complexity of feedback in writing. Unfortunately memory load is hard to assess in naturalistic settings because it is usually assessed through dual task methodologies. Moreover, it may be more important for spoken feedback than for written feedback, where re-reading may be used to compensate for overload problems.

Motivation is also frequently mentioned with respect to feedback effects (Hull 1935; Wallach and Henle 1941; Dweck 1986; Dweck and Leggert 1988). It is a complex construct than can be divided into many different elements that might be relevant to feedback implementation, such as learning versus performance motivation (Dweck 1986; Dweck and Leggert 1988), trait-level versus task-level versus state-level motivation (Wigfield and Guthrie 1997), or regulatory focus (Shah and Higgins 1997; Brockner and Higgins 2001). In order to make theoretical progress, motivation would need to be examined at these various levels. However, this level of detail is beyond the scope of the current project, especially given its focus on a naturalistic setting. Moreover, as the results will show, the feedback factors most plausibly connected to motivational effects (e.g., praise), in fact, were not related to implementation, and thus motivation factors may not have been as relevant here.

Prior writing research has not involved examining how various feedback features (as described in an earlier section) affect these potential mediating constructs. Predictions of how the feedback features might be connected to the mediators were inferred from general cognitive research (Ilgen et al. 1979; Chi et al. 1989). Because agreement has an affective component, affective language is expected to affect agreement. Praise and mitigation in the form of compliments are expected to increase one’s agreement with the other feedback (as indicated by the solid line in Fig. 1), while the other types of mitigation are expected to decrease one’s agreement with the other feedback (as indicated by the dotted line in Fig. 1). Because the rest of the features deal with the content of the feedback, these features (i.e., summarization, specificity, explanations, and scope) are expected to most strongly affect one’s understanding of the feedback, if they have any effect at all. While summarization, specificity, and explanations are expected to increase one’s understanding of the feedback, greater levels of scope are expected to decrease one’s understanding.

Feedback model

In sum, integrating previous research leads to the proposed model of feedback in writing performance shown in Fig. 1. The model identifies five important feedback features: summarization, feedback specificity, explanations, scope, and affective language. These features are divided into two groups (cognitive features and affective features) with cognitive features expected to most strongly affect understanding, and affective features expected to most strongly affect agreement. Please note that we do not necessarily consider agreement to be affective, but rather just that it is more influenced by the affective factors. In addition, we hypothesize that the cognitive features can influence agreement, but they do so indirectly through understanding. Through understanding and agreement, the feedback features are expected to affect feedback implementation.

Method

Overview

The purpose of this study was to provide an initial broad test of the proposed model of how different kinds of feedback affected revision behaviors. The general approach was to examine the correlations between feedback features, levels of mediating variables, and feedback implementation rates in a large data set of peer-review feedback and resulting paper revisions from a single course. Choosing a correlational approach enabled the use of a naturalistic environment in which external validity would be high and many factors could be examined at once. The context chosen was writing assessed by peer review because it was a setting where a large amount of feedback is available. Analyses were applied to segmented and coded pieces of feedback to determine statistically significant contributions to the likelihood of feedback implementation.

Participants & course context

The course chosen was an undergraduate survey course entitled History of the United States, 1865-present, offered in the spring of 2005 at the University of Pittsburgh. As a survey course, it satisfied the university’s history requirement, creating a heterogeneous class of students comprised those students taking it to fulfill the requirement, as well as students directly interested in the course material. By choosing this particular type of class, the demographics of the participants match the proportions of students attending the university. The majority of the participants were male (62%), Caucasian (73%), and most likely between 18 and 21 years of age. Because the setting is an introduction to history class, all of the participants are considered novice writers in this particular genre.

The main goals of the course were to introduce historical argumentation and interpretation, deepen knowledge of modern U.S. history, and sharpen critical reading and writing skills. These goals were accomplished by a combination of lectures, weekly recitations focusing on debating controversial issues, and a peer-reviewed writing assignment.

Forty percent of the students’ grades depended on the performance of their writing assignment, including both writing and reviewing activities. Papers were reviewed and graded, not by the instructor, but rather anonymously by peers who used the “Scaffolded Writing and Rewriting in the Discipline” (SWORD) system (for more details, see Cho and Schunn 2007). Although the feedback came from peers, the students as authors were provided a normal level of incentives to take the feedback seriously (i.e., the papers were graded by the peers alone).

In the system, papers were submitted online by the students and then distributed to six other students to be reviewed by them. Students had two weeks to submit their reviews of six papers based on the guidelines (i.e., prose transparency, logic of the argument, and insight beyond the core readings (see Appendix A for instructions). Students provided comments on how to make improvements on a future draft, as well as ratings on the performance in the current draft (i.e., grades). After receiving the comments, each author rated the helpfulness of each reviewer’s set of comments on their paper as well as giving short explanations of the ratings.

For the purposes of this study, the primary data sources were: (1) the comments provided by the reviewers for how to improve the paper, (2) comments provided by the writers regarding how helpful each reviewer’s feedback was for revision, and (3) the changes made to each paper between first and final drafts.

Selected papers

Students were required to write a six-to-eight page argument-driven essay answering one of the following questions: (1) whether the United States became more democratic, stayed the same, or became less democratic between 1865 and 1924, or (2) examine the meaning of the statement “wars always produce unforeseen consequences” in terms of the Spanish-American-Cuban-Filipino War and/or World War I.

Of the 111 registered students, papers from 50 students were randomly selected to be reviewed by two different experts for the purposes of a different study. This sample was used because the additional expert data helped to further refine the paper selection. Based on the first draft scores, the top 15% were excluded because these students with high scores had less incentive to make changes. Of the remaining 42 papers, only 24 were examined because a sample size of 24 papers times six reviews per paper produced a large data set to code in depth (see Table 1 for descriptive statistics of the papers).

Reviewing prompts

Students were provided guidelines for reviewing (see Appendix A). First the students were given general suggestions on how to review. Then, they were given more specific guidelines, which focused on three dimensions: prose transparency, logic of the argument, and insight beyond core readings. Prose transparency focused on whether the main ideas and transitions between ideas were clear. Logic of the argument focused on whether the paper contained support for main ideas and counter-arguments. Insight focused on whether the paper contained new knowledge or perspectives beyond the given texts and course materials.

The specific reviewing guidelines were intended to draw the students’ attention to global writing issues (Wallace and Hayes 1991). Different reviewing prompts would likely have produced different feedback content. However, regardless of why reviewers choose to provide the observed range of feedback, the current study focuses on the impact of the various forms of feedback that were observed.

Coding process

All of the peers’ comments were compiled (N = 140 reviews × 3 dimensions). Because reviewers often commented on more than one idea (i.e., transitions, examples, wording) in a single dimension, the comments were further segmented to produce a total of 1,073 idea units. An idea unit was defined as contiguous comments referring to a single topic. The length could vary from a few words to several sentences. The segments were then categorized by two independent coders (blind to the hypothesized model) for the various feedback features (see Table 2 for definitions and examples). The inter-rater reliability ranged from moderate to high Kappa values of .51–.92 (Landis and Koch 1977). The coders discussed each disputed item until an agreement was reached.

In order to address the accuracy of the feedback provided by peers, two experts evaluated all of the comments provided to the papers selected for this study. They rated each comment on “the degree of [their] agreement or disagreement about the content of feedback” with 1 indicating strongly disagree, 2–3 average, and 4–5 strongly agree. The average rating for all of the prose and logic feedback was 3.22 with the experts agreeing with over 92% of the feedback.

Types of feedback

Not all codes applied to all segments types. This section describes the hierarchy of which codes applied to various types of feedback. First, all segments were classified into type of feedback (problem/solution, praise, or summary). Then only problem/solution segments were coded for whether a problem and/or solution was provided (problem, solution, or both), the type of affective language used (neutral, compliment, or downplay/question), whether the location could be easily found (localized or not localized), and the scope of the problem/solution (global or local). Then explanations of the problem (present or absent) were coded, but only for segments with explicit problems. In addition, segments with explicit solutions were coded for explanations of the solution (present or absent).

Implementation

Each of the problem/solution segments was also coded on whether or not the feedback was implemented in the revisions. A change-tracking program, like the one found in Microsoft Word, compared the first draft and second draft of each paper and compiled a list of changes. By using the list of changes and referring to the actual papers, each problem/solution segment was coded as implemented or not implemented (Kappa = .69).

Segments that addressed insight could not be coded for implementation. Insight was defined as information beyond the course readings and materials. Since the coders did not attend the class, there was too much ambiguity in what was covered in class. In addition, some segments from the flow and logic dimensions were considered too vague to determine whether it was implemented in the revision. For example, one reviewer pointed out, “The logic of the paper seems to get lost in some of the ideas.” Only 18 segments were considered to be too vague to be coded for implementation.

Back-review coding

Each problem/solution segment was also coded for agreement and understanding using writer’s back-review comments. After submitting their second draft in SWoRD, writers were supposed to remark on how helpful they found the feedback they received. The writer provided one field of comments for all of the feedback provided by one reviewer in one dimension. Most of the time, the writer provided several specific comments for each idea the reviewer provided, whereas sometimes the writer provided a general statement about all of the ideas the reviewer commented on. The coders were careful to line up each specific comment in the back-review with the appropriate feedback segment.

If within these comments the writer explicitly disagreed with the problem or solution, the corresponding problem/solution segment was coded as not-agreed; otherwise, the segment was coded as agreed (for problems Kappa = .74; for solutions Kappa = .56). If within these comments the writer explicitly expressed a misunderstanding about a problem or solution, the corresponding problem/solution segment was coded as not-understood; otherwise, the segment was coded as understood (for problems Kappa = .57; for solutions Kappa = .52). Unfortunately, students did not always do the back-review ratings tasks, and were even more negligent in completing the back-review comments. Thus the effective N for total number of segments for analyses involving understanding or agreement is 150 for problems and 134 for solutions.

Results

Data analysis levels

Statistical analyses can be done at the segment level, the dimension level (i.e., all segments for one writer from one reviewer in one dimension combined), or the review level (i.e., all segments for one writer from one reviewer combined). The selected level of analysis was the smallest logical level possible for all variables involved in order to produce maximum statistical power and to focus upon most direct causal connections (i.e., specific feedback to specific implementations). For example, analyzing the effect of solution on the understanding of the problem is at the segment level because individual solution segments can be coded for problem understanding. By contrast, analyzing the effect of summary on the understanding of the problem must be at the review level because the reviewing instructions asked reviewers to place an overall summary in one of the reviewing dimensions. A summary has no direct problem to be addressed, but instead potentially has a broad impact across reviewing dimensions.

While many analyses were conducted, only the results that were significant at p < .05 will be discussed in text. All inferential statistics are reported in the tables rather than in text for ease of reading.

Feedback features to implementation

To begin with the simplest explanations possible, the associations between each feedback feature and performance, (i.e. the implementation rate) were examined at the segment level (except for praise, which was at the dimension level, and summarization, which was at the feedback level) to determine whether statistically significant relationships existed. As prior research has found relationships between each of the examined feedback features and performance, any of the feedback features could have a significant relationship with implementation. However, only one of the ten examined features was found to have a statistically significant relationship (see Table 3). A writer was 10% more likely to make changes when a solution was offered than when it was not offered. Note that there was not even a trend of a positive effect for the other variables. With a large N for each feature, weak statistical power is not a likely explanation for the lack of significant effects of the other variables. In other words, even with a larger N, the effects might have reached statistical significance, but would remain semantically weak, at least individually.

That these factors do not have a strong individual direct connection to implementation, however, does not necessarily imply that these factors are irrelevant to implementation. These factors could each be connected to relevant mediators,Footnote 1 which are then connected to implementation. Mediated relationships tend to be weak, even when the relationships between the mediators and other variables are of moderate strength. For example, if A–B is r = .4 and B–C is r = .4 as well, then a purely mediated A to C relationship would only be a very weak r = .16 (.4 × .4).

Mediators to implementation

Next, the associations between the mediators and implementation rate were examined—if the selected mediators do not connect to implementation rate, they are not relevant as mediators. These analyses were done at the segment level. Increased understanding and agreement were expected to increase the amount of feedback implemented. Because both understanding and agreement could connect to either the identified problems or provided solutions, four possible mediators were actually examined: understanding of the problem, understanding of the solution, agreement with the problem, and agreement with the solution.

Neither agreement with the problem nor agreement with the solution was significantly related to implementation (see Table 4). Also, understanding of the solution was not significantly related to implementation. The lack of relationship was not a result of floor or ceiling effects, as all the mediators had mean rates far from zero or one. Understanding of the problem did have a significant relationship. A writer was 23% more likely to implement the feedback if he or she understood the problem.

However, because the effective N for these analyses are lower and because all four variables had a positive, if not statistically significant, relationship to implementation, this data does not completely rule out mediational roles of the three non-significant variables. With more confidence, we know that understanding of the problem was the most important factor.

Feedback features to mediator

In order to more completely understand the relationship of feedback features to implementation, the relationship between the features and the probable mediator of problem understanding was examined next (see Table 5). Recall that the affective feedback features (i.e., praise, mitigation in the form of a compliment, and mitigation in the form of questions or downplay) were expected to affect agreement. However, agreement was not significantly related to implementation, resulting in agreement not being a possible mediator in this model. Therefore, the relationship between the affective feedback features and agreement was not analyzed.

Two relationships between the cognitive feedback features and understanding were expected. Specifically, summarization, identifying problems, providing solutions, and localization were expected to increase understanding. Explanations and greater levels of scope were expected to decrease understanding. The rate of understanding the problem was analyzed as a function of the presence/absence of each feedback feature, except identifying the problem because understanding the problem was dependent on identifying the problem.

Summarization (analyzed at the feedback level), providing solutions and localization (analyzed at the segment level) were significantly related to problem understanding. A writer was 16% more likely to understand the problem if a summary was included, 14% more likely if a solution was provided, and 24% more likely if a location to the problem and/or solution was provided. Between explanation of the problem and explanation of the solution, explanation of the problem was significantly related to problem understanding. Interestingly, the relationship was in a negative direction: A writer was 17% more likely to misunderstand the problem if an explanation to the problem was provided. Finally, greater levels of scope were not significantly related to problem understanding. Summarization, solution, localization, and explanations to problems are likely to be independent factors affecting understanding of the problem because none of these feedback features were significantly correlated with each other (see Table 6).

Potential confounding variables

The correlation between implementation rate and first draft score was examined to test for an obvious potential third variable confounding factor: students with higher first draft scores might decide to make fewer changes because they are already satisfied with their grade, and writers of stronger papers might be more likely to receive certain kinds of comments, understand feedback, etc. In order to use an unbiased first draft score, two experts graded all of the papers on the same 7-point scale that was used in class. The experts were fairly reliable (r(50) = .45). There was only a very small correlation between first draft score and implementation rate overall (r(328) = −.06, n.s.), and even the highest first draft score observed did not have a significantly lower implementation rate than all of the other first draft scores combined. Intuitively, the very highest quality papers were not selected for analysis, and thus the correlation with paper quality that one would expect might specifically involve that extreme.

Correlations between feedback features and first draft score were also examined. The presence of solutions was correlated with the first draft score, r(636) = .13, p < .01. Because it was only a small correlation and the first draft score is not correlated with implementation, a third-variable relationship with overall paper quality is not likely the reason for the relationship between presence of solutions and implementation rate.

Correlations between mediators and first draft score were examined to rule out overall performance as a potential confounding variable in the analyses involving the mediators. Understanding the problem was only marginally correlated with the first draft score (see Table 7). Therefore, it is unlikely that the relationship between understanding the problem and implementation is due to confounding effects of paper quality. The significant (and fairly strong) correlations of first draft score with the other three variables is not relevant to the discussion of confounds because those variables were not otherwise connected in the revised model. However, the presence of the various strong correlations in Table 7 provides some cross validation evidence that these measures are not simply noise.

General discussion

A revised model of feedback in writing revisions

The obtained results provided new information about the effectiveness of feedback features on writing performance (see Fig. 2). Only one internal mediator was found to significantly effect implementation: feedback was more likely to be implemented if the problem being described was understood. In turn, four feedback features were found to affect problem understanding: a writer was more likely to understand the problem if a solution was offered, the location of the problem/solution was given, or the feedback included a summary; but the writer was more likely to misunderstand the problem if an explanation for that problem is included.

One of the feedback features also directly affected implementation (i.e., not through one of the tested mediators): feedback was more likely to be implemented if a solution was provided. This direct relationship was statistically significant, whereas the connection through problem understanding was only marginally significant. Note that problem understanding is different than solution understanding. While it seems unlikely that one could implement a solution if it was not understood (i.e. without solution understanding), it is possible that one could implement a solution without understanding why it fixed the problem (i.e. without problem understanding). Doing so, however, could lead to problems because if one does not understand the problem, one could implement it unsuccessfully.

These results provide some insight into a mediator that connects to feedback implementation. Problem understanding is a generally important factor in task performance; here evidence in a new domain was found to support how important understanding is in performance. Why is problem understanding so important overall to performance? When one gains an understanding while performing a task, that person has accessed or developed his or her mental model of the task (Kieras and Bovair 1984). Having a mental model increases one’s ability to act in that situation by connecting to high level plans and a concrete solution associated with the situation. This setting focused mostly on high-level problems; if low-level feedback was examined, understanding might not be as important.

Surprisingly, agreement was not a significant mediator. In this particular setting, there may not have been a wide range of strongly agree to strongly disagree; more strongly felt agreement/disagreement levels might play a more important role. It is also possible that novice writers may not be confident enough in their own ability to decide with which feedback to agree, resulting in passively implementing everything they understood.

It is worth noting that no feedback features were strongly associated with implementation on their own, and even the strongest connection of a moderator to implementation was only a Δ of 23%. Clearly some other factors must be at play in determining whether a piece of feedback is implemented or not (e.g., perhaps writing goals, motivation levels, and memory load). Moreover, the stronger connections to implementation from mediators than from raw feedback features highlight the value/need of a model with focal moderators. The strong connections of feedback features to the identified mediator further show that more surface features of feedback continue to have an important role in models of feedback.

The results also provided additional support for which feedback features possibly affect revision behaviors and why. Solutions, summarization, localization, and explanations were found to be the features most relevant to feedback implementation as a result of their influence on understanding. The rest of this section considers why these features are connected to understanding.

Previous research has found explicitly provided solutions to be an effective feature of feedback (Bitchener et al. 2005; Sugita 2006; Tseng and Tsai 2006), although it has not specifically highlighted its role on problem understanding. Regarding the role of providing solutions on problem understanding, for a novice writer, there may not be enough information if only the problem was identified. The writer may not understand that the problem exists because they do not see what was missing. Providing a solution introduces possible missing aspects. For example, a writer may not understand a problem identified in the feedback, such as an unclear description of a difficult concept (e.g., E = mc2) because he or she may think that the problem was a result of the concept being difficult rather than the writing being unclear. However, by suggesting an alternative way of describing the concept, the writer might be more likely to understand why their writing was unclear.

Very little prior research in writing dealt with the influence of receiving summaries on performance. Therefore, the evidence regarding the importance of summaries was an especially novel addition to the literature. Why should summaries affect problem understanding? Summaries likely increased a writer’s understanding of the problem by first enabling the writer to put the reader’s overall text comprehension into perspective, and then using that perspective as a context for the rest of the feedback. For example, a writer might receive feedback indicating that not all hypotheses included the predicted direction of the effect. After reviewing all of his or her hypotheses and finding directions for each, the writer might not understand the problem. A summary provided by the reviewer may reveal that the reader has misidentified some hypotheses. The writer would now be able to put the feedback into context and better understand the problem.

Prior writing research has not specifically examined the advantages of providing the location to problems and/or solutions within feedback, so these results were also novel. Focusing on the relationship between providing locations and problem understanding, feedback on writing is likely to be ambiguous because it tends to be fairly short. Providing the location of a problem and/or solution could increase understanding of the problem by resolving the possible ambiguity of the feedback. For example, feedback might state that there were problematic transitions. After reviewing the first several transitions and finding no problems, the writer may not understand the problem because the actual problematic transitions occurred later in the paper. By providing a location in which the problem occurred, the writer could develop a better understanding of the problem.

Finally, the results of the current study regarding the negative effect of explanations to problems replicate Tseng and Tsai’s (2006) findings. They also found that explanations, contrary to intuition, hurt writing performance. As both their study and the current study involved feedback provided by novice writers, it is possible that the students were unable to provide explanations that were clear. Unclear explanations from peers may have effectively decreased understanding. By contrast, Bitchner et al. (2005) found that students’ writing performance improved when receiving explanations from an instructor.

In the broader space of feedback, research has indicated that information at a higher-level is more important than focusing on local issues, and affective language is not very important for performance (Kluger and DeNisi 1996). Researchers have claimed that other aspects of feedback are most important, such as goals (Kluger and DeNisi 1996; Hattie and Timperley 2007) and reflection (Bangert-Drowns et al. 1991). The current model is not necessarily in conflict with those claims: these aspects may be important because they lead to a better understanding of the problem.

Implications for practice

These results regarding the role of feedback features on feedback implementation could be applied to a large variety of settings, such as various education settings, performance evaluation in the workplace, and athletics. Problem understanding appears to be especially important in improving performance. Feedback should include a summary of the performance, specific instances in which the problematic behavior occurred, and suggestions in how to improve performance. The summary would indicate which behaviors the manager is evaluating and provide the context for the feedback. The specific instances should resolve any ambiguities regarding whether the behavior was actually problematic, as it is likely that the behavior being evaluated occurred frequently and was not always problematic. Finally, the suggestions could indicate to the employee what was missing in his or her behavior.

In an effort to help students perform their best, educators should take note of the types of feedback that affected writing performance the most. Feedback should begin with a summary of the students’ performance. Including summaries in feedback is common even among professionals; most journals ask reviewers to include a summary of the paper (Sternberg 2002; Roediger 2007). Feedback should also be fairly specific when referring to global issues. When describing a problem in the students’ performance, the location at which the problem occurred should also be noted. Also, the feedback should not stop at the indication of a problem, but should also include a potential solution to the problem. Finally, who is providing the feedback should be considered before including explanations. If the feedback comes from the instructor, the explanations may help. However, if the feedback is to be provided by peers, including explanations to problems currently appears unhelpful.

Limitations

There were a few methodological issues that should be considered. First, one of the variable’s inter-rater reliability was moderate rather than high (explanation of the solution, .51). No conclusions regarding the explanation of the solution were drawn. If future studies improve the coding of a solution’s explanations such that the reliability would be greater, it is possible that the explanation to the solution become more important.

Although there was initially a lot of data being examined (1,073 feedback segments), the actually number of segments available for certain analyses was drastically reduced. This reduction occurred because that not all writers provided a back-review, so those corresponding feedback segments could not be coded for agreement and understanding. A further constraint was whether the feedback included a problem or solution (i.e. if a segment did not include a problem, then the agreement with the problem or understanding of the problem could not be addressed). Finally, some of the implementable segments could not be coded for implementation because they were either about insight or vague (see Method for further explanation). This reduction in the number of segments greatly reduces the power of the analyses.

Another methodological consideration is that the current study was only correlational. Therefore, no conclusions about the causal relationships between the feedback features, mediators, and implementation can be made. Future studies should involve manipulating the feedback features in order to verify the causal effects they have on understanding, agreement, and implementation.

Future directions

In addition to addressing the limitations of this study, there are several other possible future directions. First, one could reconsider the mediator variables. In order to keep the current study’s environment to be as naturalistic as possible, we measured agreement and understanding using the back-reviews that the students needed to complete as part of their assignment. Future studies could have students give a rating on a Likert-type scale for each understanding and agreement. In addition, future studies could have a rating be given to each feedback segment. Doing so could allow for a more fine-grained analysis of the relationship between the various levels of understanding or agreement and implementation. Finally, future studies may want to examine other possible mediators, such as memory load and motivation.

It was very surprising to find that explanations to problems were associated with a lack of understanding the problem. Previous research has suggested that there may be a difference in explanations provided by novices and experts (Tseng and Tsai 2006; Bitchner et al. 2005). Future studies should examine this possible difference by comparing writing performance of those receiving feedback with explanations from peers versus instructors. Also, one could compare qualitative differences in novice and expert explanations to determine why certain explanations hurt and how improvements to explanations could be made such that students are able to provide helpful explanations.

Future research should also consider different contexts. The current study was done with university level participants in a domain that involves a lot of writing. Future studies could consider other age ranges, such as high school or middle school students. The level of language skill could also be considered, such as those for whom English is their second language or those who have learning disabilities. Finally, other domains should be considered, such as domains where writing is not usually the focus (i.e. physics or engineering).

Finally, one should consider examining the effects of the various feedback features on learning. The feedback features that we found to be related to increased problem understanding and increased implementation may not change performance in a transfer task. It is also possible that the features not found to be significantly related to problem understanding or implementation may be more useful for transfer tasks. Since this study provides some initial insight on performance differences associated with different types of feedback in writing, one would be able to approach examining learning differences with some necessary foundational information.

Summary

The current study advances our knowledge about understanding’s relationship with performance and the types of feedback that could increase one’s understanding. Similar to other research involving understanding, the current study provides additional support that understanding is important in changing performance. Knowing which feedback features to include in order to increase understanding and which feedback features to avoid because they might decrease understanding is also important because understanding is so important for improving performance.

Notes

We use the term mediator because the variables of understanding and agreement are thought to mediate between external features and implementation. However, we cannot apply formal mediation statistical tests on this dataset because of the reduced Ns associated with the mediating variables. We do note, however, that the correlation found from external features to mediator variables as well mediators to implementation are always stronger than the direct “correlation” between external features and implementation, and thus mediation relationships are quite consistent with the statistical patterns in the data.

References

Bangert-Drowns, R. L., Kulik, C. C., Kulik, J. A., & Morgan, M. T. (1991). The instruction effect of feedback in test-like events. Review of Educational Research, 61(2), 218–238.

Bitchener, J., Young, S., & Cameron, D. (2005). The effect of different types of corrective feedback on ESL student writing. Journal of Second Language Writing, 14, 191–205.

Bransford, J. D., Brown, A. L., & Cocking, R. R. (Eds.) (2003). How people learn: Brain, mind, experience, and school. Washington DC: National Academy Press.

Bransford, J. D., & Johnson, M. K. (1972). Contextual prerequisites for understanding: Some investigations of comprehension and recall. Journal of verbal learning and verbal behavior, 11, 717–726.

Brockner, J., & Higgins, E. T. (2001). Regulatory foccus theory: Implications for the study of emotions at work. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 86(1), 35–66.

Brown, F. J. (1932). Knowledge of results as an incentive in school room practice. Journal of Educational Psychology, 23(7), 532–552.

Chi, M. T. H., Bassok, M., Lewis, M. W., Reimann, P., & Glaser, R. (1989). Self-Explanations: How students study and use examples in learning to solve problems. Cognitive Science, 13, 145–182.

Cho, K., & Schunn, C. D. (2007). Scaffolded Writing and Rewriting in the Discipline: A web-based reciprocal peer review system. Computers & Education, 48(3), 409–426.

Cho, K., Schunn, C. D., & Charney, D. (2006). Commenting on writing: Typology and perceived helpfulness of comments from novice peer reviewers and subject matter experts. Written Communication, 23(3), 260–294.

Dweck, C. S. (1986). Motivational processes affecting learning. American Psychologist, 41(10), 1040–1048.

Dweck, C. S., & Leggert, E. L. (1988). A social-cognitive approach to motivation and personality. Psychological Review, 95(2), 256–273.

Ferris, D. R. (1997). The influence of teacher commentary on student revision. TESOL Quarterly, 31(2), 315–339.

Gick, M. L., & Holyoak, K. J. (1980). Analogical problem solving. Cognitive Psychology, 12, 306–355.

Gick, M. L., & Holyoak, K. J. (1983). Schema induction and analogical transfer. Cognitive Psychology, 15, 1–38.

Grimm, N. (1986). Improving students’ responses to their peers’ essays. College Composition and Communication, 37(1), 91–94.

Haswell, R. H. (2005). NCTE/CCCC’s recent war on scholarship. Written Communication, 22(2), 198–223.

Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 81–112.

Hayes, J. R. (1996). A new framework for understanding cognition and affect in writing. In L. W. Gregg, & E. R. Steinberg (Eds.), The science of writing (pp. 1–27). Mahwah, New Jersey: Erlbaum.

Hayes, J. R., Flower, L., Schriver, K. A., Stratman, J., & Carey, L. (1987). Cognitive processes in revision. In S. Rosenberg (Ed.), Advances in applied psycholinguistics, Volume II: Reading, writing, and language processing (pp. 176–240). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Hull, C. L. (1935). Thorndike’s fundamentals of learning. Psychological Bulletin, 32, 807–823.

Hyland, F., & Hyland, K. (2001). Sugaring the pill Praise and criticism in written feedback, Jouranl of Second Language Writing, 10, 185–212.

Ilgen, D. R., Fisher, C. D., & Taylor, M. S. (1979). Consequences of individual feedback on behavior in organizations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 64(4), 349–371.

Kellogg, R. T. (1996). A model of working memory in writing. In L. W. Gregg, & E. R. Steinberg (Eds.), The science of writing (pp. 57–71). Mahwah, New Jersey: Erlbaum.

Kieras, D. E., & Bovair, S. (1984). The role of a mental model in learning to operate a devise. Cognitive Science, 8, 255–273.

Kluger, A. N., & DeNisi, A. (1996). The effects of feedback interventions on performance: A historical review, a meta-analysis, and a preliminary feedback intervention theory. Psychological Bulletin, 119(2), 254–284.

Kulhavy, R. W., & Stock, W. A. (1989). Feedback in written instruction: The place of response certitude. Educational Psychology Review, 1(4), 279–308.

Kulhavy, R. W., & Wager, W. (1993). Feedback in programmed instruction: Historical context and implications for practice. In J. V. Dempsey, & G. C. Sales (Eds.), Interactive instruction and feedback (pp. 3–20). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Educational Technology.

Landis, J. R., Koch, G. G. (1977). The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics, 33(1), 159–174.

Lin, S. S. J., Liu, E. Z. F., & Yuan, S. M. (2001). Web-based peer assessment: Feedback for students with various thinking-styles. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 17(4), 420–432.

Matsumura, L. C., Patthey-Chavez, G. G., Valdes, R., & Garnier, H. (2002). Teacher feedback, writing assignment quality, and third-grade students’ revision in lower- and higher-achieving urban schools. The Elementary School Journal, 103(1), 3–25.

McCutchen, D. (1996). A capacity theory of writing: Working memory in composition. Educational Psychological Review, 8(3), 299–325.

Miller, P. J. (2003). The effect of scoring criteria specificity on peer and self-assessment. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 28(4), 383–394.

Mory, E. H. (1996). Feedback research. In D.H. Jonassen (Ed.), Handbook of research for educational communications and technology (pp. 919–956). New York: Simon & Schuster Macmillan.

Mory, E. H. (2004). Feedback research revisited. In D.H. Jonassen (Ed.), Handbook of research for educational communications and technology Second Edition (pp. 745–783). Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Neuwirth, C. M., Chandhok, R., Charney, D., Wojahn, P., & Kim, L. (1994). Distributed Collaborative writing: A comparison of spoken and written modalities for reviewing and revising documents. Proceedings of the Computer-Human Interaction ‘94 Conference, April 24–28, 1994, Boston Massachusetts (pp. 51–57). New York: Association for Computing Machinery.

Newell, A., & Simon, H. A. (1972). Human problem solving. Englewoods Clis, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Nilson, L. B. (2003). Improving student peer feedback. College Teaching, 51(1), 34–38.

Novick, L. R., & Holyoak, K. J. (1991). Mathematical problem solving by analogy. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 17(3), 398–415.

Olson, M. W., & Raffeld, P. (1987). The effects of written comments on the quality of student compositions and the learning of content. Reading Psychology: An International Quarterly, 8, 273–293.

Pressey, S. L. (1926). A simple device which gives tests and scores—and teaches. School and Society, 23, 373–376.

Pressey, S. L. (1927). A machine for automatic teaching of drill material. School and Society, 25, 549–552.

Roediger, H. L. (2007). Twelve Tips for Reviewers. APS Observer, 20(4), 41–43.

Saddler, B., & Andrade, H. (2004). The writing rubric. Educational Leadership, 62(2), 48–52.

Shah, J., & Higgins, E. T. (1997). Expectancy X value effects: Regulatory focus as determinant of magnitude and direction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73(3), 447–458.

Sternberg, R. J. (2002). On civility in reviewing. APS Observer, 15(1).

Sugita, Y. (2006). The impact of teachers’ comment types on students’ revision. ELT Journal, 60(1), 34–41.

Symonds, P. M., & Chase, D. H. (1929). Practice vs. motivation. Journal of Educational Psychology, 20(1), 19–35.

Thorndike, E. L. (1927). The law of effect. American Journal of Psychology, 39(1/4), 212–222.

Toegel, G., & Conger, J. A. (2003). 360-degree assessment: Time for Reinvention. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 2(3), 297–311.

Tseng, S.-C., & Tsai, C.-C. (2006). On-line peer assessment and the role of the peer feedback: A study of high school computer course. Computers & Education.

Wallace, D. L., & Hayes, J. R. (1991). Redefining revision for freshman. Research in the Teaching of English, 25, 54–66.

Wallach, H., & Henle, M. (1941). An experimental analysis of the Law of Effect. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 28, 340–349.

Wigfield, A., & Guthrie, J. T. (1997). Relations of children’s motivation for reading and the amount of breadth of their reading. Journal of Educational Psychology, 89(3), 420–432.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by A.W. Mellon Foundation. Thanks to Danikka Kopas, Jennifer Papuga, and Brandi Melot for all their time coding data. Also thanks to Lelyn Saner, Elisabeth Ploran, Chuck Perfetti, Micki Chi, Michal Balass, Emily Merz, and Destiny Miller for their comments on earlier drafts.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix A: Reviewing guidelines

Appendix A: Reviewing guidelines

General reviewing guidelines

There are two very important parts to giving good feedback. First, give very specific comments rather than vague comments: Point to exact page numbers and paragraphs that were problematic; give examples of general problems that you found; be clear about what exactly the problem was; explain why it was a problem, etc. Second, make your comments helpful. The goal is not to punish the writer for making mistakes. Instead your goal is to help the writer improve his or her paper. You should point out problems where they occur. But don’t stop there. Explain why they are problems and give some clear advice on how to fix the problems. Also keep your tone professional. No personal attacks. Everyone makes mistakes. Everyone can improve writing.

Prose transparency

Did the writing flow smoothly so you could follow the main argument? This dimension is not about low level writing problems, like typos and simple grammar problems, unless those problems are so bad that it makes it hard to follow the argument. Instead this dimension is about whether you easily understood what each of the arguments was and the ordering of the points made sense to you. Can you find the main points? Are the transitions from one point to the next harsh, or do they transition naturally?

Your comments: First summarize what you perceived as the main points being made so that the writer can see whether the readers can follow the paper’s arguments. Then make specific comments about what problems you had in understanding the arguments and following the flow across arguments. Be sure to give specific advice for how to fix the problems and praise-oriented advice for strength that made the writing good.

Logic of the argument

This dimension is about the logic of the argument being made. Did the author just make some claims, or did the author provide some supporting arguments or evidence for those claims? Did the supporting arguments logically support the claims being made or were they irrelevant to the claim being made or contradictory to the claim being made? Did the author consider obvious counter-arguments, or were they ignored?

Your comments: Provide specific comments about the logic of the author’s argument. If points were just made without support, describe which ones they were. If the support provided doesn’t make logical sense, explain what that is. If some obvious counter-argument was not considered, explain what that counter-argument is. Then give potential fixes to these problems if you can think of any. This might involve suggesting that the author change their argument.

Insight beyond core readings

This dimension concerns the extent to which new knowledge is introduced by a writer. Did the author just summarize what everybody in the class would already know from coming to class and doing the assigned readings, or did the author tell you something new?

Your comments: First summarize what you think the main insights were of this paper. What did you learn if anything? Listing this clearly will give the author clear feedback about the main point of writing a paper: to teach the reader something. If you think the main points were all taken from the readings or represent what everyone in the class would already know, then explain where you think those points were taken or what points would be obvious to everyone. Remember that not all points in the paper need to be novel, because some of the points need to be made just to support the main argument.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nelson, M.M., Schunn, C.D. The nature of feedback: how different types of peer feedback affect writing performance. Instr Sci 37, 375–401 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11251-008-9053-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11251-008-9053-x