Abstract

Besides pure declarative arguments, whose premises and conclusions are declaratives (“you sinned shamelessly; so you sinned”), and pure imperative arguments, whose premises and conclusions are imperatives (“repent quickly; so repent”), there are mixed-premise arguments, whose premises include both imperatives and declaratives (“if you sinned, repent; you sinned; so repent”), and cross-species arguments, whose premises are declaratives and whose conclusions are imperatives (“you must repent; so repent”) or vice versa (“repent; so you can repent”). I propose a general definition of argument validity: an argument is valid exactly if, necessarily, every fact that sustains its premises also sustains its conclusion, where a fact sustains an imperative exactly if it favors the satisfaction over the violation proposition of the imperative, and a fact sustains a declarative exactly if, necessarily, the declarative is true if the fact exists. I argue that this definition yields as special cases the standard definition of validity for pure declarative arguments and my previously defended definition of validity for pure imperative arguments, and that it yields intuitively acceptable results for mixed-premise and cross-species arguments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Consider the following dialogue from Joseph Heller’s novel Catch-22 (1961/1994, pp. 54–55):

“Can’t you ground someone who’s crazy?”

“Oh, sure. I have to. There’s a rule saying I have to ground anyone who’s crazy.” ...

“Is Orr crazy?”

“He sure is,” Doc Daneeka said.

“Can you ground him?”

“I sure can. But first he has to ask me to. That’s part of the rule.” ...

“And then you can ground him?” Yossarian asked.

“No. Then I can’t ground him.”

“You mean there’s a catch?”

“Sure there’s a catch,” Doc Daneeka replied. “Catch-22. Anyone who wants to get out of combat duty isn’t really crazy.”

Here is one way to understand Doc Daneeka’s (implicit) argument:

-

Rule: Ground anyone who is crazy, but if and only if he asks to be grounded.

-

Catch-22: Anyone who asks to be grounded is not crazy.

-

Conclusion: Don’t ground anyone who is crazy.

Does the conclusion follow from the rule and the catch? In other words, is the above argument (deductively) valid? Some people may think so. But the first premise and the conclusion are imperatives, not propositions. If imperatives cannot be true or false, then to say that the above argument is valid is not to say that, necessarily, its conclusion is true if its premises are true. What is it, then, for the above argument and similar ones to be valid? The development of a satisfactory answer to this question is a major object of the present paper. This is not a purely academic question: as I have argued elsewhere (Vranas 2010), inferences with an imperative conclusion and at least one imperative premise occur with some regularity in everyday life.

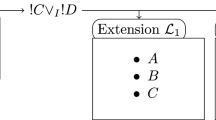

To formulate the above question more precisely, distinguish imperative sentences from what such sentences typically express, namely what I call prescriptions (i.e., commands, requests, instructions, suggestions, etc.). This distinction is analogous to the familiar distinction between declarative sentences and what such sentences typically express, namely propositions. Given that a declarative sentence (like “you will stand guard until midnight”) can express a prescription, and that an imperative sentence (like “marry in haste and repent at leisure”) can express a proposition, I prefer to take the premises and conclusions of arguments to be propositions or prescriptions rather than declarative or imperative sentences (although nothing substantive in this paper hangs on this preference, and my main results can be easily reformulated in terms of sentences). So I define an argument as an ordered pair whose first coordinate is a non-empty set of propositions or prescriptions or both (the premises of the argument) and whose second coordinate is either a proposition or a prescription (the conclusion of the argument). I call an argument declarative exactly if its conclusion is a proposition, and imperative exactly if its conclusion is a prescription. I call an argument (1) pure exactly if its premises and its conclusion are either all propositions or all prescriptions, (2) mixed-premise exactly if its premises include both a proposition and a prescription, and (3) cross-species exactly if either its premises are all propositions and its conclusion is a prescription or its premises are all prescriptions and its conclusion is a proposition. (I call an argument mixed exactly if it is not pure; equivalently, exactly if it is either mixed-premise or cross-species.) Table 1 combines the above distinctions and gives, for each possible combination, an argument that might appear valid (although, as I argue later on, not all arguments in the table are in fact valid).

Given the above terminology, one may ask: what is it for a mixed-premise imperative argument (like the argument in the Catch-22 example) to be valid? In this paper, I answer this question and related ones by proposing a general definition of argument validity: a definition that applies to all kinds of arguments I distinguished above. I argue (§2) that my definition yields as special cases both the standard definition of validity for pure declarative arguments and a definition of validity for pure imperative arguments that I have defended elsewhere (Vranas 2011). Then I argue that my definition yields intuitively acceptable results for cross-species imperative arguments (§3), cross-species declarative arguments (§4), mixed-premise declarative arguments (§5), and mixed-premise imperative arguments (§6). I conclude in §7, and in the Appendix I examine alternative definitions of argument validity.

This paper is a sequel to two other papers (Vranas 2008, 2011) but does not presuppose any familiarity with those papers. For the moment I need only the following definitions from those papers. A prescription is an ordered pair of (logically) incompatible propositions, namely the satisfaction proposition (the first coordinate of the pair) and the violation proposition (the second coordinate of the pair) of the prescription. The disjunction of those two propositions is the context of the prescription; the negation of the context is the avoidance proposition of the prescription. A prescription is unconditional exactly if its avoidance proposition is (logically) impossible (equivalently, its context is necessary; still equivalently, its violation proposition is the negation of its satisfaction proposition), and is conditional exactly if it is not unconditional. A prescription is satisfied, violated, or avoided exactly if, respectively, its satisfaction, violation, or avoidance proposition is true. For example, the prescription (expressed by—addressing to you—the imperative sentence) “if it thunders, dance” is satisfied exactly if it thunders and you dance (regardless of whether you dance because it thunders; see Vranas 2008, p. 534; 2013, p. 2577), is violated exactly if it thunders and you do not dance, and is avoided exactly if it does not thunder. Since this prescription can be avoided, it is conditional; its context is the proposition that it thunders. By contrast, the prescription “dance” is unconditional; it is satisfied exactly if you dance, it is violated exactly if you do not dance, and it cannot be avoided.

2 A general definition of argument validity

2.1 A first desideratum: combining and splitting premises

The task of defining argument validity can be simplified by noting that one need only consider mixed-premise arguments with a single declarative premise and a single imperative premise. This is because one wants a definition of argument validity on which one can combine multiple declarative or multiple imperative premises by conjunction into a single premise and one can split a single premise which is a conjunction of certain conjuncts into multiple premises (the conjuncts) without affecting validity—just as one can do for pure declarative and for pure imperative arguments on standard definitions of validity for such arguments. More formally, it is desirable for a definition of argument validity to have the following consequence (cf. Smart 1984, p. 17):

- (D1):

-

A mixed-premise argument A is valid exactly if the two-premise argument \(A^{\prime }\) is valid whose single declarative premise is the conjunction of the declarative premises of A, whose single imperative premise is the conjunction of the imperative premises of A, and whose conclusion is the conclusion of A.

(For the moment it does not matter how exactly one defines the conjunction of prescriptions; I give my definition in §4.Footnote 1 I see no way to simplify matters even further by conjoining the single declarative with the single imperative premise, because I see no interesting way to define the conjunction of a proposition with a prescription; see Vranas 2008, pp. 543–544.Footnote 2) Similar observations can be made about cross-species (and pure) arguments, whose premises can be combined by conjunction into a single premise because they are either all propositions or all prescriptions. Unless I specify otherwise, in what follows I should be understood as referring only to two-premise mixed-premise arguments, and only to single-premise cross-species and pure arguments.

2.2 A second desideratum: transmission of meriting endorsement

A declarative argument is “fully successful” (i.e., sound) only if its conclusion is true. Similarly, I submit, an imperative argument is fully successful only if its conclusion is supported by reasons: reasons for acting (e.g., if the conclusion is “donate to charities”), reasons for feeling (e.g., if the conclusion is “love your enemies”), reasons for believing (e.g., if the conclusion is “believe whatever the Pope says”), and so on.Footnote 3 To have a uniform terminology for propositions and prescriptions, say that a proposition merits endorsement exactly if it is true, and that a prescription merits endorsement exactly if it is supported by reasons.Footnote 4 (If one finds this terminology objectionably subjective, one is welcome to use a more objective-sounding term; for example, say that a proposition is factual exactly if it is true, and that a prescription is factual exactly if it is supported by reasons.) Then any argument, declarative or imperative, is fully successful only if its conclusion merits endorsement (i.e., is factual). This suggests that it is desirable for a definition of argument validity to have the following consequence:

- (D2):

-

An argument is valid only if, necessarily, if its premises merit endorsement, then its conclusion merits endorsement.Footnote 5

To make this suggestion precise, however, three groups of issues need to be addressed.

2.2.1 Reasons and support

What is a reason, and what is it for a reason to support a prescription? I take a (normative and comparative) reason to be a fact that counts in favor of—in short, that favors—some proposition over some other one. For example, a reason for you to repent (rather than not repenting) is a fact that favors the proposition that you repent over the proposition that you do not repent, and a reason for you to marry Hugh rather than Hugo is a fact that favors the proposition that you marry Hugh over the proposition that you marry Hugo. I take a reason to support a prescription exactly if it favors the satisfaction proposition over the violation proposition of the prescription. For example, a reason supports the prescription “if you drink, don’t drive” exactly if it favors the proposition that you drink and do not drive over the proposition that you drink and drive. (Strictly speaking, I distinguish strong from weak support, but I postpone discussing this distinction until §6.1.) The above remarks are not enough to determine whether any given fact is a reason or supports any given prescription; but determining this lies beyond the scope of logic, so in this paper I take the relation of favoring to be primitive. For the moment I only assume that favoring is asymmetric: necessarily, any fact that favors a proposition P over a proposition \(P^{\prime }\) does not also favor \(P^{\prime }\) over P.Footnote 6 (See Vranas 2011, pp. 381–384 for further discussion of the issues in this paragraph.)

2.2.2 Meriting endorsement jointly versus separately

There is a relation—call it guaranteeing—between facts and propositions which is in an important respect analogous to the relation of supporting between facts and prescriptions: a fact guarantees a proposition exactly if, necessarily, the proposition is true if the fact exists (i.e., is a fact).Footnote 7 For example, the fact that Strasbourg is in France and Salzburg is in Austria guarantees the proposition that Strasbourg is in France. Guaranteeing and supporting are in an important respect analogous because, as I will argue, (1) a prescription merits endorsement exactly if it is supported by some fact, and (2) a proposition merits endorsement exactly if it is guaranteed by some fact. Claim (1) holds because, by definition, a prescription merits endorsement exactly if it is supported by reasons, but every reason is a fact and every fact that supports a prescription favors some proposition over some other one (namely the satisfaction proposition over the violation proposition of the prescription) and thus is a reason. Claim (2) holds because a proposition which is guaranteed by some fact is true (i.e., merits endorsement) and, conversely, a true proposition is guaranteed by the fact that it is true: necessarily, the proposition is true if the fact that the proposition is true exists. (I assume that, necessarily, if a proposition is true, then it is a fact that the proposition is true, even if the proposition is necessary. This assumption might be rejected by opponents of “negative facts” (cf. Molnar 2000, pp. 76–80; contrast Barker and Jago 2012) or of facts in general, but these opponents are welcome to replace my talk of facts with talk of true propositions, and thus to take reasons to be true propositions rather than facts.) To have a uniform terminology for propositions and prescriptions, say that a fact sustains a proposition exactly if it guarantees the proposition, and that a fact sustains a prescription exactly if it supports the prescription. Then a proposition or a prescription merits endorsement exactly if it is sustained by some fact. Table 2 recapitulates some major definitions and equivalences for ease of reference.

One might claim that the concept of sustaining is “an objectionable gerrymander—a disjunction of [guaranteeing and supporting] designed to create the illusion that two quite different [concepts] have something in common” (cf. Parsons 2013, p. 81). To support this claim, one might point to disanalogies between supporting and guaranteeing: supporting is contingent (see Vranas 2011, p. 377 n. 8) but guaranteeing is not, supporting (or rather favoring) is primitive but guaranteeing is not, and supporting is normative (since it entails the existence of a reason) but guaranteeing is not. I reply that the concept of meriting endorsement (which corresponds to the concept of sustaining) is arguably not gerrymandered: both for prescriptions and for propositions, meriting endorsement is contingent, non-primitive, and normative (see note 4).Footnote 8 In any case, nothing substantive hangs on my choice to adopt a uniform terminology for propositions and prescriptions; the terminology is primarily intended to yield a compact formulation of my general definition of argument validity (§2.3).

With the concept of sustaining in place, say that a proposition and a prescription (for example, the two premises of a mixed-premise argument) merit endorsement jointly exactly if some fact sustains both the proposition and the prescription, and that they merit endorsement separately exactly if some fact sustains the proposition and some (maybe different) fact sustains the prescription. (To see how a fact can sustain both a proposition and a prescription, consider: the fact that you lied and you promised to apologize guarantees the proposition that you lied and normally supports the prescription “apologize”.) Clearly, meriting endorsement jointly entails meriting endorsement separately. But not vice versa: possibly, the proposition that you have sworn to tell the truth and the prescription “lie” do not merit endorsement jointly (because no fact which guarantees that you have sworn to tell the truth is a reason for you to lie) but do merit endorsement separately (because you have sworn to tell the truth but some fact—which does not guarantee that you have sworn to tell the truth; e.g., the fact that by lying you would avoid punishment—is a reason for you to lie). Now one can distinguish two ways of understanding D2:

- (D2J):

-

An argument is valid only if, necessarily, if its premises merit endorsement jointly, then its conclusion merits endorsement.

- (D2S):

-

An argument is valid only if, necessarily, if its premises merit endorsement separately, then its conclusion merits endorsement.

(D2S entails D2J, given that meriting endorsement jointly entails meriting endorsement separately.) I understand D2 as D2J. To see why, consider the following three arguments:

Argument 1 | Argument 2 | Argument 3 |

|---|---|---|

You did not tell the truth. | Don’t tell the truth. | Don’t tell the truth. |

You told the truth. | Tell the truth. | The fact that you have sworn to tell the truth |

So: You smiled. | So: You smiled. | is a conclusive reason for you to tell the truth. |

So: You smiled. |

All three arguments may appear invalid. But Argument 1 is valid on the standard definition of validity for pure declarative arguments: its premises are inconsistent. It is reasonable to look for a definition of argument validity that yields as a special case the standard definition of validity for pure declarative arguments. This makes it reasonable (though not inevitable) to look for a definition of argument validity on which any argument with inconsistent premises is (trivially) valid: not only arguments with inconsistent declarative premises, like Argument 1, but also arguments with inconsistent imperative premises, like Argument 2, and—I submit—arguments with inconsistent mixed premises, like Argument 3. The claim that the premises of Argument 3 are inconsistent will be defended later on (by arguing that it is impossible for those premises to merit endorsement jointly and that this impossibility amounts to inconsistency; see note 41), but for the moment let me appeal to the intuition (which will be vindicated in §3) that the declarative premise of Argument 3 entails “tell the truth”—which is inconsistent with the imperative premise, namely “don’t tell the truth”. But if Argument 3 is valid (because its premises are inconsistent), then D2S is false: it is possible that the conclusion of Argument 3 does not merit endorsement but the premises merit endorsement separately (though not jointly, as I said), because it is possible that you did not smile but there is both a conclusive reason for you to tell the truth—namely the fact that you have sworn to do so—and a non-conclusive reason for you not to tell the truth. This is why I understand D2 as D2J. I grant that one might reasonably disagree with the above train of thought, but I am in the process of providing a motivation for—not yet a full defense of—my general definition of argument validity.

2.2.3 Meriting pro tanto versus all-things-considered endorsement

I said that an imperative argument is fully successful only if its conclusion is supported by reasons, and in §2.2.2 I (tacitly) understood the claim that a prescription is supported by reasons as the claim that the prescription is supported by some reason, namely that it merits pro tanto (i.e., prima facie) endorsement. But one might argue that being supported by some reason does not amount to much; for example, convincing you that there is some reason for you to smother a crying baby with a pillow (e.g., the fact that this would eliminate the annoyance of the baby’s cries) is by no means enough to convince you to smother the baby with a pillow. The point is that (the support provided by) a reason may be very weak, and may be defeated by other reasons. (If a fact supports a prescription, say that another fact defeats—i.e., is a defeater of—this support exactly if the conjunction of the two facts—understood as the fact that exists at all and only those possible worlds at which the two facts both existFootnote 9—does not support the prescription; cf. Pollock 1970, p. 73; 1974, pp. 41–42; 1987, p. 484.) So one might argue that an imperative argument is fully successful only if its conclusion merits all-things-considered endorsement, namely the conclusion is undefeatedly supported by some fact (or reason): there is a fact whose conjunction with any fact supports the conclusion (equivalently: some fact supports the conclusion, and no fact defeats this support).Footnote 10 (My talk of “conclusive” reasons in §2.2.2 can be made precise now: say that a fact conclusively—or indefeasibly—supports a prescription exactly if, necessarily, if the fact exists then it undefeatedly supports the prescription.) To have a uniform terminology for propositions and prescriptions, say that a proposition merits pro tanto endorsement exactly if it is guaranteed by some fact, and that a proposition merits all-things-considered endorsement exactly if it is undefeatedly guaranteed by some fact: there is a fact whose conjunction with any fact guarantees the proposition. But for propositions this is a distinction without a difference: a fact guarantees a proposition exactly if it undefeatedly guarantees the proposition. Now one can distinguish two ways of understanding D2J:

- (D2JP):

-

An argument is valid only if, necessarily, if its premises merit pro tanto endorsement jointly, then its conclusion merits pro tanto endorsement. Equivalently: an argument is valid only if, necessarily, if some fact sustains every premise of the argument, then some fact sustains the conclusion of the argument.

- (D2JA):

-

An argument is valid only if, necessarily, if its premises merit all-things-considered endorsement jointly, then its conclusion merits all-things-considered endorsement. Equivalently: an argument is valid only if, necessarily, if some fact undefeatedly sustains (i.e., its conjunction with any fact sustains) every premise of the argument, then some fact undefeatedly sustains the conclusion of the argument.Footnote 11

In §2.2.2 I understood D2J as D2JP, but the above considerations suggest that it is also desirable for a definition of argument validity to have D2JA as a consequence.Footnote 12 In fact, the definition of argument validity I am about to propose has both D2JP and D2JA as consequences.

2.3 The General Definition

Here is the fundamental idea of this paper:

General Definition of Argument Validity. An argument is (deductively) valid—i.e., its premises entail its conclusion; equivalently, its conclusion follows from its premises—exactly if, necessarily, every fact that sustains every premise of the argument also sustains the conclusion of the argument.Footnote 13

(Strictly speaking, this definition applies only to two-premise mixed-premise arguments, and to single-premise pure and cross-species arguments; to get a complete definition, add D1 (§2.1) for mixed-premise arguments, and similar claims for pure and cross-species arguments.)

In support of the General Definition, I will argue that (1) it has both D2JP and D2JA as consequences, and (2) it yields as special cases both the standard definition of validity for pure declarative arguments and a definition of validity for pure imperative arguments that I have defended elsewhere.

-

(1)

To see that the General Definition has both D2JP and D2JA as consequences, take any valid argument. (a) Necessarily, if some fact sustains every premise of the argument, then—by the General Definition—that fact (and thus some fact) sustains the conclusion of the argument; so D2JP holds. (b) Necessarily, if some fact undefeatedly sustains every premise of the argument, then the conjunction of that fact with any fact sustains every premise and thus—by the General Definition—sustains the conclusion of the argument, and then that fact (and thus some fact) undefeatedly sustains the conclusion; so D2JA holds.Footnote 14

-

(2)

Given that to sustain a proposition is to guarantee it and to sustain a prescription is to support it (see Table 2), the General Definition yields as special cases the following definitions:

Definition 1

A pure declarative argument is valid exactly if, necessarily, every fact that guarantees the premise of the argument also guarantees the conclusion of the argument.

Definition 2

A pure imperative argument is valid exactly if, necessarily, every fact that supports the premise of the argument also supports the conclusion of the argument.

(a) The standard definition of validity for (single-premise) pure declarative arguments says that a pure declarative argument is valid exactly if, necessarily, if its premise is true, then its conclusion is also true. To see that this definition is equivalent to Definition 1, take any argument. Suppose that, (i) necessarily, every fact that guarantees the premise of the argument also guarantees the conclusion. Then, necessarily, if the premise is true, then the fact that the premise is true guarantees the premise and thus—by (i)—also guarantees the conclusion, so the conclusion is true. Conversely, suppose that, (ii) necessarily, if the premise is true, then the conclusion is also true. Then, necessarily, if a given fact guarantees the premise, then, necessarily, if the fact exists then the premise and thus—by (ii)—also the conclusion is true, so the fact also guarantees the conclusion.Footnote 15 (b) The definition of validity for (single-premise) pure imperative arguments that I have extensively defended elsewhere (Vranas 2011) says that a pure imperative argument is valid exactly if, necessarily, every reason that supports the premise of the argument also supports the conclusion of the argument. It is easy to see that this definition is equivalent to Definition 2, by recalling that every reason is a fact and every fact that supports a prescription is a reason.

Given the above results, the General Definition looks quite promising. But is the definition usable? In other words, can one use the definition to decide whether specific arguments—for example, the argument from “repent” to “you can repent”—are valid? In the next four sections, I address this question for cross-species imperative arguments (§3), cross-species declarative arguments (§4), mixed-premise declarative arguments (§5), and mixed-premise imperative arguments (§6). In the process of doing so, I also provide further support for the General Definition, by arguing that it yields intuitively acceptable results concerning the validity of specific arguments.

3 Cross-species imperative arguments

Recall that a cross-species imperative argument is an argument whose premise is a proposition and whose conclusion is a prescription (see Table 1); for example, the argument from “you must repent” to “repent”. Given that to sustain a proposition is to guarantee it and to sustain a prescription is to support it (see Table 2), the General Definition yields as a special case:

Definition 3

A cross-species imperative argument is valid exactly if, necessarily, every fact that guarantees the (declarative) premise of the argument supports the (imperative) conclusion of the argument.

Say that an argument A is equivalent to an argument \(A^{\prime }\) as a shorthand for saying that the claim that argument A is valid is equivalent to the claim that argument \(A^{\prime }\) is valid. Definition 3 is rendered usable by the following theorem:

Equivalence Theorem 1

(1) The cross-species imperative argument from the proposition P to the prescription \(I^{\prime }\) is equivalent to the pure declarative argument from P to the proposition that some fact whose existence follows from P undefeatedly supports \(I^{\prime }.\) (2) Equivalently, P entails \(I^{\prime }\) exactly if P entails that the fact that P is true undefeatedly supports \(I^{\prime }.\)

Proof

(a) Suppose that, necessarily, every fact that guarantees P supports \(I^{\prime }.\) Then, necessarily, if P is true, then the fact—call it \(f_{P}\)—that P is true (and thus some fact whose existence follows from P) undefeatedly supports \(I^{\prime }\): the conjunction of \(f_{P}\) with any fact supports \(I^{\prime }\) because it guarantees P (since, necessarily, if the conjunction exists then \(f_{P}\) exists and thus P is true). (b) Conversely, suppose that, necessarily, if P is true, then some fact f whose existence follows from P (for example, the fact that P is true) undefeatedly supports \(I^{\prime }.\) Then, necessarily, if a given fact g guarantees P, then g supports \(I^{\prime }\) because (i) the conjunction of f with g supports \(I^{\prime }\) (since f undefeatedly supports \(I^{\prime }\)) but (ii) this conjunction is just g (since, necessarily, g exists exactly if f and g both exist; this is so because, necessarily, if g exists then P is true and thus f exists).

A first consequence of the theorem (or directly of Definition 3) is that, as expected (see §2.2.2), an impossible proposition entails any prescription. A second—and more interesting—consequence of the theorem is that (as one can show), for any f, the argument from the proposition that f is a fact which undefeatedly supports \(I^{\prime }\) to the prescription \(I^{\prime }\) is valid. For example, the following argument is valid:

Argument 4

-

The fact that you have sworn to tell the truth is an undefeated reason

-

for you to tell the truth (i.e., undefeatedly supports “tell the truth”).

-

So: Tell the truth.

Indeed, according to the theorem, the validity of Argument 4 is equivalent to the validity of the pure declarative argument from the premise P of Argument 4 to the proposition that some fact whose existence follows from P undefeatedly supports “tell the truth”. But this pure declarative argument is valid: necessarily, if P is true, then some fact whose existence follows from P, namely the fact that you have sworn to tell the truth, undefeatedly supports “tell the truth”. By the way, I can now vindicate an intuition to which I appealed in §2.2.2, namely the intuition that the proposition \(P^{*}\) that the fact that you have sworn to tell the truth is a conclusive reason for you to tell the truth entails “tell the truth”: since \(P^{*}\) entails P and P entails “tell the truth”, \(P^{*}\) entails “tell the truth” (by the transitivity of entailment, which follows from the General Definition).

A third consequence of the theorem is that a necessary condition for a cross-species imperative argument to be valid is that its premise entail that its conclusion is undefeatedly supported by some fact. For example, the following three arguments violate this necessary condition and thus are not valid:

Argument 5 | Argument 6 | Argument 7 |

|---|---|---|

You will | The fact that you have sworn to tell the truth | There is a reason for |

tell the truth. | is a reason for you to tell the truth. | you to tell the truth. |

So: Tell the truth. | So: Tell the truth. | So: Tell the truth. |

Indeed, the premise of Argument 5 does not entail that there is any reason for you to tell the truth, and the premise of Argument 6 (similarly for Argument 7) does not entail that there is an undefeated reason for you to tell the truth: possibly, the fact that you have sworn to tell the truth is a reason for you to tell the truth, but this reason—and every other reason there is for you to tell the truth—is defeated by some fact.Footnote 16 It is widely accepted in the literature that arguments like Argument 5 are not valid.Footnote 17 To see that the result that Argument 7 (similarly for Argument 6) is not valid is intuitively acceptable, compare Argument 7 with the following argument:

Argument 8

-

There is a defeated reason for you to tell the truth, and

-

there is an undefeated reason for you not to tell the truth.

-

So: Tell the truth.

The premise of Argument 8 entails the premise of Argument 7, and the two arguments have the same conclusion. Therefore, if Argument 7 is valid, Argument 8 is also valid (by the transitivity of entailment). Since this relation between the two arguments is intuitively clear, if Argument 8 is intuitively not valid, then Argument 7 is intuitively not valid either. But Argument 8 is intuitively not valid. So Argument 7 is intuitively not valid either. (This is a claim about tutored intuitions; I am not denying that some people may have the raw—i.e., untutored—intuition that Argument 7 is valid.) Now compare Argument 7 with the following argument:

Argument 9

-

There is an undefeated reason for you to tell the truth.

-

So: Tell the truth.

Given that (as I said), for any f, the argument from the proposition that f is a fact which undefeatedly supports \(I^{\prime }\) to the prescription \(I^{\prime }\) is valid, it is natural to expect the argument from the proposition that there is a fact which undefeatedly supports \(I^{\prime }\) to the prescription \(I^{\prime }\) to be valid, and thus it is natural to expect Argument 9 to be valid (although Argument 7 is not; cf. Castañeda 1975, pp. 258, 304). (Compare: Argument 4 is valid although Argument 6 is not.) Indeed, by the second part of the theorem, Argument 9 is valid: necessarily, the fact that there is an undefeated reason for you to tell the truth is an undefeated reason for you to tell the truth. I am assuming here that, necessarily, if it is a fact that some reason undefeatedly supports a given prescription, then that fact undefeatedly supports the prescription. (This is at bottom an assumption about the relation of favoring, like my previously made—see §2.2.1—assumption that favoring is asymmetric.) I find the assumption plausible; but it might be considered controversial,Footnote 18 so I do not rely on it in the rest of this paper. Let me just note that, if the assumption is true, then the previously mentioned necessary condition for a cross-species imperative argument to be valid is also sufficient: if P entails that some fact undefeatedly supports \(I^{\prime }\) (which is what the condition amounts to) and the proposition that some fact undefeatedly supports \(I^{\prime }\) entails \(I^{\prime }\) (which is what the assumption amounts to), then P entails \(I^{\prime }\) (by the transitivity of entailment). Therefore, if the assumption is true, P entails \(I^{\prime }\) exactly if P entails that some fact undefeatedly supports \(I^{\prime }.\) Footnote 19

It might be thought that the validity of (for example) Argument 4 refutes what Rescher (1966, p. 74) calls “Poincaré’s Principle”, namely the “rule” that Hare (1952, p. 30) attributes to Poincaré (1913, p. 225) and formulates as follows: “No imperative conclusion can be validly drawn from a set of premisses which does not contain at least one imperative” (Hare 1952, p. 28).Footnote 20 Although Hare defends this rule (1952, p. 32), strictly speaking he is not committed to the above formulation (1977, p. 468; 1979, p. 161 n. 1): he (at least implicitly) restricts the rule to consistent sets of premises—a restriction also adopted by Bergström (1962, p. 44), Espersen (1967, p. 99), Gensler (1990, p. 209), and Lemmon (1965, p. 69)—and to conclusions that are not what Hare calls “hypothetical” imperatives (1952, pp. 32–38) and do not contain any logical connectives (1977, pp. 468–469). (Argument 4 satisfies these conditions.) Hare also claims, however, that “‘ought’-sentences, at any rate in some of their uses, do entail imperatives” (1952, p. 164); for example, “I ought to do X”, used to make a “value-judgement”, entails “let me do X” (1952, pp. 168–169). But this creates a puzzle: since “I ought to do X” is not imperative, doesn’t the claim that it entails “let me do X” contradict (even the restricted version of) Hare’s rule (i.e., Poincaré’s Principle)? No: Hare in effect notes the puzzle, and replies that there is no contradiction because “I ought to do X” is “evaluative” and not “equivalent to a series of indicative sentences” (1952, p. 171). This suggests that, strictly speaking, Hare endorses something like the following variant of Poincaré’s Principle: no imperative conclusion can be validly drawn from a consistent set of non-evaluative (more generally, non-normative) non-imperative premises.Footnote 21 This variant of Poincaré’s Principle need not be false if Argument 4 is valid: the premise of that argument is normative.

For another consequence of Equivalence Theorem 1, consider the following two arguments:

Argument 10 | Argument 11 |

|---|---|

Antarctica is the coldest continent. | Antarctica is the coldest continent. |

So: Either go to Antarctica | So: Either go to Antarctica |

or don’t go to Antarctica. | or don’t go to the coldest continent. |

To refute Poincaré’s Principle, Geach (1958, pp. 55–56) argues that (a variant of) Argument 11 is valid.Footnote 22 (Following Geach, note that the conclusion of Argument 11—unlike the conclusion of Argument 10—is not “vacuous”: it is not necessarily satisfied, because it is violated for example at some possible world at which the coldest continent is Europe rather than Antarctica and you go to Europe.) According to Equivalence Theorem 1, however, neither Argument 10 nor Argument 11 is valid: both arguments violate the previously mentioned necessary condition for a cross-species imperative argument to be valid, namely the condition that the premise of the argument entail that the conclusion is undefeatedly supported by some fact. Indeed, the proposition that Antarctica is the coldest continent does not entail that any fact supports any prescription (because it is possible that Antarctica is the coldest continent but no fact is a reason), and thus does not entail that any fact undefeatedly supports the conclusion of Argument 10 (similarly for Argument 11).

One might claim that Argument 10 is valid because “either go to Antarctica or don’t go to Antarctica” is analogous to a declarative tautology and thus follows from any premises (cf. Lemmon 1965, p. 57), just as “go to Antarctica and don’t go to Antarctica” is analogous to a declarative contradiction and thus entails any conclusion. In reply, note first that the prescription “go to Antarctica and don’t go to Antarctica” is analogous to a declarative contradiction (which is necessarily false) not only in the sense that it is necessarily violated, but also in the sense that (as it is plausible to assume; see Vranas 2011, pp. 433–434), necessarily, no fact supports it (which yields, by the General Definition, the result that this prescription entails any conclusion). By contrast, the prescription “either go to Antarctica or don’t go to Antarctica” is analogous to a declarative tautology (which is necessarily true) in the sense that it is necessarily satisfied but not in the sense that, necessarily, every fact supports it (which would yield, by the General Definition, the result that this prescription follows from any premises): the claim that, necessarily, every fact supports a given prescription is false because it entails that, necessarily, every fact is a reason. Some people might defend the weaker claim (which I reject; cf. Vranas 2011, pp. 406–407) that, necessarily, every reason (i.e., every fact which is a reason) supports “either go to Antarctica or don’t go to Antarctica”; but this weaker claim poses no problem for the reasoning in the previous paragraph to the effect that Argument 10 is not valid. Note finally that, for the sake of having a unified account of validity, one has reason to accept the verdicts of the General Definition on practically useless arguments like Argument 10 if the verdicts of the definition on more useful arguments are intuitively acceptable.

4 Cross-species declarative arguments

Recall that a cross-species declarative argument is an argument whose premise is a prescription and whose conclusion is a proposition (see Table 1); for example, the argument from “repent” to “you can repent”. Given that to sustain a proposition is to guarantee it and to sustain a prescription is to support it (see Table 2), the General Definition yields as a special case:

Definition 4

A cross-species declarative argument is valid exactly if, necessarily, every fact that supports the (imperative) premise of the argument guarantees the (declarative) conclusion of the argument.

This definition is rendered usable by the following theorem:

Equivalence Theorem 2

The cross-species declarative argument from the prescription I to the proposition \(P^{\prime }\) is equivalent to the pure declarative argument from the proposition that some fact f is such that possibly f supports I to the proposition \(P^{\prime }.\) (In other words: \(P^{\prime }\) follows from I exactly if \(P^{\prime }\) follows from the proposition that there is a fact which possibly—i.e., at some possible world—supports I.)

Proof

(a) Suppose that, necessarily (i.e., at everyFootnote 23 possible world), every fact that supports I guarantees \(P^{\prime }.\) Take any possible world w at which some fact f possibly supports I. Then, at some possible world \(w^{\prime },\,f\) supports I and thus—by the supposition—guarantees \(P^{\prime };\) i.e., at \(w^{\prime }\)—and thus also at w—it is necessary that, if f exists, then \(P^{\prime }\) is true. Since f exists at w, \(P^{\prime }\) is true at w. (b) Conversely, suppose that, necessarily, if some fact possibly supports I, then \(P^{\prime }\) is true. Take any possible world w. If a fact f supports I at w, then f guarantees \(P^{\prime }\) at w because, necessarily, if f exists, then f (and thus some fact) possibly supports I (since f supports I at w) and thus—by the supposition—\(P^{\prime }\) is true.

A first consequence of the theorem (or directly of Definition 4) is that a necessary proposition follows from any prescription. A second consequence of the theorem is that the following argument is valid:

Argument 12

-

Marry me.

-

So: Possibly, there is a reason for you to marry me

-

(i.e., possibly, some fact supports “marry me”).

Indeed, the proposition that some fact possibly supports “marry me” entails that, possibly, something—i.e., some fact (see note 7)—supports “marry me”. The result that Argument 12 is valid is intuitively acceptable because either (1) the conclusion of Argument 12 is true, and then it is necessary (assuming that whatever is possible is necessarily possible) and thus it follows from any prescription (by the—intuitively acceptable—previous consequence of the theorem), or (2) the conclusion of Argument 12 is false, in other words it is necessary that no fact supports the prescription “marry me”, and then this prescription entails any proposition (see the last paragraph of §3).

A third consequence of the theorem is that neither of the following two arguments is valid:

Argument 13 | Argument 14 |

|---|---|

Marry me. | Marry me. |

So: You will marry me. | So: There is a reason for you to marry me. |

Indeed, the proposition that some fact possibly supports “marry me” entails neither that you will marry me nor that some fact supports “marry me” (i.e., that there is a reason for you to marry me). Note that, necessarily, if the premise of Argument 14 merits pro tanto or all-things-considered endorsement (i.e., if some fact supports or undefeatedly supports “marry me”), then so does the conclusion (i.e., it is true). So the fact that Argument 14 is not valid shows that transmission of meriting pro tanto and of meriting all-things-considered endorsement from the premises to the conclusion of an argument is not sufficient for the argument to be valid (recall that it is necessary: see D2JP and D2JA in §2.2.3).

It is widely accepted in the literature that arguments like Argument 13 are not valid;Footnote 24 intuitively, there is no necessary connection between a prescription and the proposition that the prescription is satisfied (except in special cases: “either run or don’t run” does entail the necessary proposition that either you will run or you will not run). Similarly, I submit, the result that Argument 14 is not valid is intuitively acceptable (cf. Clark-Younger and Girard 2013) because, intuitively, there is no necessary connection between a prescription and the proposition that the prescription is supported by some fact (except in special cases). In response one might note that there is a necessary connection between a proposition P and the proposition that P is true, and might argue by analogy that (Argument 14 is valid because) there is also a necessary connection between a prescription I and the proposition that I is supported by some fact. I reply that, if the analogy works, then I and the proposition that I is supported by some fact entail each other (since P and the proposition that P is true entail each other), and then not only Argument 14 but also its converse argument (namely the argument from “there is a reason for you to marry me” to “marry me”) is valid. But the converse argument is not valid (see the discussion of Argument 7 in §3), so the analogy fails.Footnote 25

A fourth consequence of the theorem is that the following argument is valid:

Argument 15

-

Marry me.

-

So: Some fact is possibly a reason for you to marry me.

Indeed, the proposition that some fact possibly supports “marry me” just is—and thus trivially entails—the conclusion of Argument 15. I find the result that Argument 15 is valid intuitively acceptable. But even if one disagrees, for the sake of having a unified account of validity one has reason to accept the verdict of the General Definition (or Definition 4) on this argument if one agrees with me that the verdicts of the definition on the previous three arguments are intuitively acceptable.Footnote 26

For further consequences of the theorem, consider the following three arguments:

Argument 16 | Argument 17 | Argument 18 |

|---|---|---|

Marry me. | Marry me. | Marry me. |

So: It is possible for | So: Possibly, you | So: You can |

you to marry me. | can marry me. | marry me. |

If it is true (as I implicitly assumed in the last paragraph of §3) that, necessarily, a necessarily violated prescription—like “go to Antarctica and don’t go to Antarctica”—is necessarily not supported by any fact,Footnote 27 then the conclusion of Argument 12 entails the conclusion of Argument 16: necessarily, if it is possible that some fact supports “marry me” (i.e., if the conclusion of Argument 12 is true), then—by the above assumption—the prescription “marry me” is not necessarily violated, so it is possible for you to marry me (i.e., the conclusion of Argument 16 is true).Footnote 28 But then, given that Argument 12 is valid, Argument 16 is also valid (by the transitivity of entailment, given that the two arguments have the same premise). Similarly, if it is true (as some people might assume; see Vranas 2007 for a defense of the assumption) that, necessarily, there is a reason for you to marry me only if you can marry me, the conclusion of Argument 12 entails the conclusion of Argument 17, and then Argument 17 is also valid. By contrast, Argument 18 is not valid (pace Rescher 1966, pp. 94–95) because the proposition that some fact possibly supports “marry me” does not entail that you can marry me: possibly, you cannot marry me (because I am already married and neither polygamy nor remarriage is available) but some fact (namely the fact that we love each other) is possibly a reason for you to marry me (it would be such a reason if I were not already married).Footnote 29 My claim that “marry me” does not entail “you can marry me” (i.e., that Argument 18 is not valid) is compatible with the claim that “there is an undefeated reason for you to marry me” entails both “marry me” (see Argument 9) and “you can marry me”.

The second assumption I stated in the previous paragraph (namely the assumption that, necessarily, there is a reason for you to marry me only if you can marry me) is controversial. Moreover, one might take the proposition that there is a reason for you to marry me only if you can marry me to be conceptually but not logically necessary, and thus one might take Argument 17 to be conceptually valid (like the argument from “this is a yellow shirt” to “this is a colored shirt”) but not logically valid (unlike the argument from “this is a yellow shirt” to “this is a shirt”). One might thus object to my project in this paper that it is not an investigation into logical validity and thus is not important for logic. I reply that this objection “proves too much”. A deontic logician may well assume (as an axiom) that whatever is obligatory is permissible, and an epistemic logician may well assume that whatever is known is true; these assumptions may be conceptually but not logically necessary, but it does not follow that the projects of these logicians are unimportant for logic.Footnote 30

The validity of Argument 12 (and of Argument 15) refutes what Rescher (1966, pp. 72–73) calls “Hare’s Thesis”, namely the “rule” that Hare formulates as follows: “No indicative conclusion can be validly drawn from a set of premisses which cannot be validly drawn from the indicatives among them alone” (Hare 1952, p. 28).Footnote 31 Hare’s Thesis is widely rejected in the literature, but the two frequently discussed kinds of alleged counterexamples to it are very different from Argument 12 (and from Argument 15) and—as I will argue—do not succeed. First, some people (Castañeda 1960a, p. 48; 1963, pp. 228–229; 1974, p. 130; Rescher 1966, pp. 92–95) claim that arguments like the one from “marry Dan’s only daughter” to “Dan has only one daughter” are valid. But the sentence “marry Dan’s only daughter” can be understood in (at least) two ways, corresponding to the following two arguments:

Argument 19 | Argument 20 |

|---|---|

Dan has only one daughter; | Let it be the case that: Dan has only one daughter, |

(let it be the case that you) marry her. | and you marry her. |

So: Dan has only one daughter. | So: Dan has only one daughter. |

The intuition that Argument 19 is valid may be compelling (and I vindicate it below), but it should be intuitively clear that Argument 20 is not valid: intuitively, even if the premise of Argument 20 entails “let it be the case that Dan has only one daughter”, it does not entail “Dan has only one daughter”. Indeed, it is a consequence of Equivalence Theorem 2 that Argument 20 is not valid: the proposition that some fact is possibly a reason for Dan to have only one daughter and for you to marry her (i.e., that some fact possibly favors the proposition that Dan has only one daughter and you marry her over the negation of that proposition) does not entail that Dan has only one daughter. But what about Argument 19, which arguably corresponds to a more typical way of understanding the sentence “marry Dan’s only daughter”? Following Rescher (1966, p. 92; cf. Duncan-Jones 1952, p. 197), one might suggest that the composite sentence “Dan has only one daughter; marry her” expresses a “meshed composite” of a proposition and a prescription. But if this is understood as the suggestion that the composite sentence expresses an entity of a third kind, distinct both from propositions and from prescriptions, I reply that I do not see what such a kind of entity would be. (Moreover, let us not multiply kinds of entities beyond necessity.) I suggest instead that the composite sentence expresses both a proposition (namely the proposition that Dan has only one daughter) and a prescription (namely either (1) the premise of Argument 20 or, if the composite sentence expresses a prescription which is neither satisfied nor violated if Dan does not have only one daughter, (2) the prescription expressed by “if Dan has only one daughter, marry her”Footnote 32). But then Argument 19 is a mixed-premise (rather than a cross-species) declarative argument (see Table 1); its conclusion is identical with—and thus trivially follows from—its declarative premise, so its validity (which is an immediate consequence of the General Definition) does not refute Hare’s Thesis.Footnote 33 I conclude that the first frequently discussed kind of alleged counterexample to Hare’s Thesis does not succeed.

The second frequently discussed kind of alleged—but, as I will argue, also unsuccessful—counterexample to Hare’s Thesis is exemplified by an argument proposed by Castañeda (1960a, pp. 48–49; 1974, pp. 130–131):Footnote 34

Argument 21

-

If he comes, leave the files open.

-

Do not leave the files open.

-

So: He will not come [or: he does not come].

To defend his claim that Argument 21 is valid, Castañeda considers a scenario in which a boss first tells his secretary to leave the files open if a certain person comes to inspect them, but then, after speaking with someone on the phone, says to his secretary: “Well, Emily, don’t leave the files open, after all” (1960a, p. 49; 1974, p. 131). According to Lemmon, however, the secretary “may [not] infer that the other person will not come; rather surely she may hope that he will not come (because if he does then she certainly cannot obey her boss’s orders)—or she may conclude from her knowledge of her boss that he does not think the other person will come” (1965, p. 64). In reply, Espersen (1967, p. 97; cf. Harrison 1991, pp. 111–112) grants that “he will not come” does not follow from the fact that the boss has issued the two orders, but notes that similarly “he will not come” does not follow from the fact that a given person has expressed the propositions “if he comes, the files will be open” and “the files will not be open” (although it does follow from the propositions themselves). I take Espersen’s point to be that to ask whether Argument 21 is valid is to ask whether “he will not come” follows from the prescriptions which are the premises of the argument, not whether it follows from the fact that a given person has expressed those prescriptions (cf. Duncan-Jones 1952, p. 200). Appreciating this point, however, casts doubt on the relevance of Castañeda’s scenario: in that scenario the secretary may infer “he will not come” from the premise that the boss has issued the two orders together with the (implicit) premise that the boss would not do so if the other person were coming (cf. Duncan-Jones 1952, p. 200; Zellner 1971, pp. 97–98), but how does the scenario show that the secretary may infer “he will not come” from the boss’s orders themselves?

To cast further doubt on the relevance of Castañeda’s scenario, consider a modified scenario in which the boss first tells his secretary not to leave the files open, but then, after speaking with someone on the phone, tells his secretary to leave the files open after all if a certain person comes to inspect them. Intuitively, in this modified scenario the secretary may not infer that the other person will not come. But whether an argument is valid cannot depend on the order in which its premises are uttered (except if one considers dynamic concepts of validity, which lie beyond the scope of this paper). Castañeda might respond that in the modified scenario it is natural to understand the boss’s second order as canceling the first; he specifies that his own scenario is not to be understood in this way (1960a, p. 48; 1974, pp. 130–131; cf. Geach 1958, p. 52). Still, our intuitions are suspicious if they are influenced by the order in which the premises are uttered. To avoid such influences, and also for the reason I gave in §2.1, I propose to consider the conjunction of the premises of Argument 21. Here is the definition of imperative conjunction that I have defended elsewhere (Vranas 2008, pp. 538–541):

Definition 5

The conjunction of given prescriptions (the conjuncts) is the prescription whose context is the disjunction of the contexts of the conjuncts and whose violation proposition is the disjunction of the violation propositions of the conjuncts.

Using this definition, one can show that the conjunction of the premises of Argument 21 is the premise of the following argument,Footnote 35 so that Argument 21 is valid exactly if the following argument is (see D1 in §2.1):

Argument 22

-

Let it be the case that: he does not come, and you do not leave the files open.

-

So: He will not come [or: he does not come].

But it is a consequence of Equivalence Theorem 2 that Argument 22 is not valid (see the reasoning I gave for Argument 20), and indeed it should be intuitively clear that Argument 22 is not valid: intuitively, even if the premise of Argument 22 entails “let it be the case that he does not come”, it does not entail “he does not come”. I conclude that Hare’s Thesis is not refuted by any of the frequently discussed alleged counterexamples to it—although, as I said, it is refuted by the validity of Argument 12 (and of Argument 15).Footnote 36

5 Mixed-premise declarative arguments

Recall that a mixed-premise declarative argument is an argument whose premises are a prescription and a proposition and whose conclusion is a proposition (see Table 1); for example, the argument from “if you sinned, repent” and “you sinned” to “you will repent”. Given that to sustain a proposition is to guarantee it and to sustain a prescription is to support it (see Table 2), the General Definition yields as a special case:

Definition 6

A mixed-premise declarative argument is valid exactly if, necessarily, every fact that both supports the imperative premise and guarantees the declarative premise of the argument guarantees the (declarative) conclusion of the argument.

The following theorem has a proof similar to my proof in §4 of Equivalence Theorem 2:

Equivalence Theorem 3

(1) The mixed-premise declarative argument from the prescription I and the proposition P to the proposition \(P^{\prime }\) is equivalent to the pure declarative argument from the proposition that some fact which guarantees P possibly supports I to the proposition \(P^{\prime }.\) (2) Equivalently, \(P^{\prime }\) follows from I and P exactly if \(P^{\prime }\) follows from the proposition that there is a fact which possibly both guarantees P and supports I.Footnote 37

Although this theorem is of interest, I do not use it in what follows; instead I use Definition 6 directly. Given the mixed-premise declarative argument from the prescription I and the proposition P to the proposition \(P^{\prime },\) say that its pure subargument is the argument from P to \(P^{\prime },\) and say that its cross-species subargument is the argument from I to \(P^{\prime }.\) A first consequence of Definition 6 (in conjunction with Definitions 1 and 4) is that a mixed-premise declarative argument is valid if its pure subargument or its cross-species subargument is valid. For example, the following two arguments are valid:

Argument 23 | Argument 24 |

|---|---|

Repent. | Repent. |

Felicity and Letitia are nuns. | Felicity and Letitia are nuns. |

So: Letitia is a nun. | So: Possibly, there is a reason for you to repent. |

A second consequence of Definition 6 is that the following two arguments are valid:

Argument 25 | Argument 26 |

|---|---|

Repent. | Either repent or undo the past. |

If it is possible for you to repent, | It is impossible for you to |

then you will repent. | undo the past. |

So: You will repent. | So: It is possible for you to repent. |

Indeed, necessarily, every fact that supports “repent” guarantees that it is possible for you to repent (see the discussion of Argument 16 in §4), so every fact that both supports “repent” and guarantees that you will repent if it is possible for you to repent guarantees both that (1) it is possible for you to repent and that (2) you will repent if it is possible for you to repent, and thus also guarantees that (3) you will repent—and Argument 25 is valid.Footnote 38 (Similarly for Argument 26.)

A third (and very useful) consequence of Definition 6 is that the mixed-premise declarative argument from I and P to \(P^{\prime }\) is not valid if the following proposition is possible: some fact which supports I guarantees both P and the negation of \(P^{\prime }.\) Indeed, if that proposition is possible, then it is possible that some fact which both supports I and guarantees P does not guarantee \(P^{\prime }\) (since, necessarily, every fact that guarantees the negation of \(P^{\prime }\) does not guarantee \(P^{\prime }\)), and then (by Definition 6) I and P do not jointly entail \(P^{\prime }.\) For example, the following argument is not valid:

Argument 27

-

If you sinned, repent.

-

You sinned.

-

So: You will repent.

Indeed, it is possible that the fact that (1) you have promised that, if you sinned, you will repent but (2) you sinned and yet you will not repent—which, by (2), guarantees both that you sinned (namely P) and that you will not repent (namely the negation of \(P^{\prime }\))—supports, in virtue of (1), “if you sinned, repent” (namely I): there may be a reason for you to keep your promise even if you are going to break it. I trust that the result that Argument 27 is not valid is intuitively acceptable.

A fourth consequence of Definition 6 is that a mixed-premise declarative argument is valid if, necessarily, no fact both supports the imperative premise and guarantees the declarative premise of the argument. In other words, a mixed-premise declarative argument is valid if its premises are inconsistent as per the following definition:

Definition 7

A proposition and a prescription are (jointly) inconsistent—i.e., the proposition is inconsistent with the prescription; in other words, the prescription is inconsistent with the proposition—exactly if, necessarily, no fact both guarantees the proposition and supports the prescription (i.e., it is impossible for the proposition and the prescription to merit endorsement jointly; see §2.2.2), and are (jointly) consistent otherwise.Footnote 39

Here are five (neither mutually exclusive nor collectively exhaustive) cases in which a proposition P and a prescription I are inconsistent. Case 1 P is impossible. In this case, necessarily, no fact guarantees P; so, necessarily, no fact both guarantees P and supports I. Case 2 I is necessarily violated. In this case, necessarily, no fact supports I (given my standing assumption that, necessarily, a necessarily violated prescription is necessarily not supported by any fact);Footnote 40 so, necessarily, no fact both guarantees P and supports I. Case 3 I entails the negation of P. In this case, necessarily, every fact that supports I guarantees the negation of P and thus does not guarantee P (since, necessarily, every fact that guarantees the negation of P does not guarantee P); so, necessarily, no fact both guarantees P and supports I. Case 4 P entails the negation of I, defined (see Vranas 2008, p. 536) as the prescription whose satisfaction proposition is the violation proposition of I and whose violation proposition is the satisfaction proposition of I (for example, the negation of “hide” is “don’t hide”, and the negation of “if there is a tornado, hide” is “if there is a tornado, don’t hide”). In this case, necessarily, every fact that guarantees P supports the negation of I and thus does not support I (since, necessarily, every fact that supports the negation of I does not support I, given that favoring is asymmetric);Footnote 41 so, necessarily, no fact both guarantees P and supports I. Case 5 P entails that no fact supports I. In this case, necessarily, no fact both guarantees P and supports I. Indeed, if one assumes for reductio that at some possible world some fact f both guarantees P and supports I, then at that world it is the case both that no fact supports I (this follows from P) and that f is a fact that supports I—a contradiction. I take it that in all five cases there is intuitively an incompatibility between the proposition and the prescription, and the desire to unify these cases motivates Definition 7.Footnote 42 The premises of the following three (trivially) valid arguments exemplify cases 3, 4, and 5, respectively:Footnote 43

Argument 28 | Argument 29 | Argument 30 |

|---|---|---|

Repent. | Repent. | Repent. |

It is impossible | The fact that you have sworn not to repent | There is no reason |

for you to repent. | is a conclusive reason for you not to repent. | for you to repent. |

So: Letitia is a nun. | So: Letitia is a nun. | So: Letitia is a nun. |

One might conjecture that, if a proposition and a prescription are inconsistent, then either the prescription entails the negation of the proposition or the proposition entails the negation of the prescription (or both). This is indeed so in the first four cases above, but some examples of the fifth case falsify the conjecture: “there is no reason for you to repent” and “repent” are inconsistent, but “repent” does not entail “there is a reason for you to repent” (see Argument 14) and “there is no reason for you to repent” does not entail “don’t repent” (because “there is no reason for you to repent” does not entail that there is any reason for you not to repent; see §3). (See Vranas 2011, p. 445 n. 75 for the failure of a comparable conjecture—and of its converse—concerning inconsistent prescriptions.) By contrast, it has in effect already been shown that the converse of the above conjecture is true: if I entails the negation of P or P entails the negation of I, then P and I are inconsistent (see cases 3 and 4 above).Footnote 44

Finally, a fifth consequence of Definition 6 is the following restricted version of Hare’s Thesis (see §4): if it is possible that the fact that P is true supports I, then \(P^{\prime }\) follows from I and P only if \(P^{\prime }\) follows from P alone (I show this in note 45).Footnote 45 For example, since it is possible that the fact that you have promised to repent supports “repent”, a proposition follows from “repent” and “you have promised to repent” only if it follows from “you have promised to repent” alone.

6 Mixed-premise imperative arguments

Recall that a mixed-premise imperative argument is an argument whose premises are a prescription and a proposition and whose conclusion is a prescription (see Table 1); for example, the argument from “if you sinned, repent” and “you sinned” to “repent”. Given that to sustain a proposition is to guarantee it and to sustain a prescription is to support it (see Table 2), the General Definition yields as a special case:

Definition 8

A mixed-premise imperative argument is valid exactly if, necessarily, every fact that both supports the imperative premise and guarantees the declarative premise of the argument supports the (imperative) conclusion of the argument.

I conjecture that there is no useful equivalence theorem for mixed-premise imperative arguments, but I will render Definition 8 usable by providing several sufficient conditions (§6.1) and—indirectly—a necessary condition (§6.2) for a mixed-premise imperative argument to be valid.

6.1 Valid mixed-premise imperative arguments

Given the mixed-premise imperative argument from the prescription I and the proposition P to the prescription \(I^{\prime },\) say that its pure subargument is the argument from I to \(I^{\prime },\) and say that its cross-species subargument is the argument from P to \(I^{\prime }.\) A first consequence of Definition 8 (in conjunction with Definitions 2 and 3) is that a mixed-premise imperative argument is valid if its pure subargument or its cross-species subargument is valid. A second consequence of Definition 8 (in conjunction with Definition 7) is that a mixed-premise imperative argument is valid if its premises are inconsistent. A third—and more interesting—consequence of Definition 8 is that the mixed-premise imperative argument from I and P to \(I^{\prime }\) is valid if P entails that every fact that supports I also supports \(I^{\prime }.\) Indeed, if P entails that every fact that supports I also supports \(I^{\prime },\) then, necessarily, if f is any fact that both supports I and guarantees P, then P is true and thus every fact that supports I also supports \(I^{\prime },\) so f supports \(I^{\prime }\) (since f supports I). For example, the following two arguments are valid:

Argument 31 | Argument 32 |

|---|---|

Disarm the bomb. | Disarm the bomb. |

“Disarm the bomb” entails | Every reason for you to disarm the bomb |

“cut the wire”. | is a reason for you to cut the wire. |

So: Cut the wire. | So: Cut the wire. |

Indeed, by Definition 2 the declarative premise of Argument 31 entails the proposition that every fact that supports “disarm the bomb” also supports “cut the wire”, and that proposition is equivalent to the declarative premise of Argument 32. Similarly, if the proposition that you can disarm the bomb only if you cut the wire entails that every reason for you to disarm the bomb is a reason for you to cut the wire (contrast Kolodny 2011), then the following argument is also valid:

Argument 33

-

Disarm the bomb.

-

You can disarm the bomb only if you cut the wire.

-

So: Cut the wire.Footnote 46

The following theorem provides another sufficient condition for a mixed-premise imperative argument to be valid:

Theorem 4

The mixed-premise imperative argument from the prescription I and the proposition P to the prescription \(I^{\prime }\) is valid if P entails some prescription \(I^{*}\) such that, necessarily, every fact that supports both I and \(I^{*}\) also supports \(I^{\prime }.\)

Proof

Suppose that, (1) necessarily, every fact that guarantees P supports \(I^{*},\) and that, (2) necessarily, every fact that supports both I and \(I^{*}\) also supports \(I^{\prime }.\) Then, necessarily, every fact that both supports I and guarantees P supports both I and—by (1)—\(I^{*},\) and thus—by (2)—also supports \(I^{\prime }.\)

The sufficient condition for validity provided by Theorem 4 is trivially satisfied if P entails \(I^{\prime }\) (i.e., if the cross-species subargument of the mixed-premise imperative argument is valid). Before I apply Theorem 4 to a more interesting case, I need to go over a distinction between strong and weak support that I have introduced elsewhere (Vranas 2011, pp. 384–390). Suppose it is a fact that you have promised to resign today. This fact is both a reason for you to resign today and a reason for you to resign. But it supports the prescriptions “resign today” and “resign” in different ways: it favors every proposition which entails that you resign today (and thus that your promise is not broken) over every proposition which entails that you do not resign today (and thus that your promise is broken), but it does not favor every proposition which entails that you resign over every proposition which entails that you do not resign (because, for example, it does not favor the proposition that you resign next year over the proposition that you do not resign: both propositions entail that your promise is broken). This example (in conjunction with other considerations; see Vranas 2011, pp. 384–390) motivates the following definition:

Definition 9

A fact (1) strongly supports a prescription exactly if it favors every proposition which entails the satisfaction proposition of the prescription over every proposition which entails the violation proposition of the prescription, and (2) weakly supports a prescription I exactly if it strongly supports some prescription \(I^{*}\) whose satisfaction proposition entails the satisfaction proposition of I and whose context is the same as the context of I.Footnote 47

The distinction between strong and weak support did not matter in this paper so far (with a single exception: see note 41), but it does matter from now on. Note that the concepts I have defined in terms of support—namely the concepts of sustaining, being a reason for, meriting endorsement, being valid, entailing, following from, and being consistent—can be understood either in terms of strong support or in terms of weak support. In particular, define (for prescriptions) strong sustaining as strong support and weak sustaining as weak support (for propositions, define both strong and weak sustaining as guaranteeing; see Table 2), and say that an argument is (1) s / s valid exactly if, necessarily, every fact that strongly sustains every premise of the argument also strongly sustains the conclusion of the argument, and is (2) w / w valid exactly if, necessarily, every fact that weakly sustains every premise of the argument also weakly sustains the conclusion of the argument.Footnote 48 To simplify the exposition, I will continue to talk about support and validity simpliciter; whenever in the remainder of this section (including §6.2) I do this, I should be understood as talking about weak support and w / w validity (and similarly for sustaining etc.). In fact, from now on I use the more precise terminology only in some notes (never in the text).

The following theorem complements Theorem 4:

Theorem 5

Let C, \(C^{*},\) and \(C^{\prime }\) be the contexts and V, \(V^{*},\) and \(V^{\prime }\) be the violation propositions of the prescriptions I, \(I^{*},\) and \(I^{\prime },\) respectively, and suppose that C entails \(C^{*}\) or \(C^{*}\) entails C. Then (1) and (2) are equivalent:

-

(1)

Necessarily, every fact that supports both I and \(I^{*}\) also supports \(I^{\prime }.\)

-

(2)

\(C^{\prime }\) entails the disjunction of C and \(C^{*},\) and \(V^{\prime }\) entails the disjunction of V and \(V^{*}.\) Footnote 49

One can now show that the following argument is valid:

Argument 34

-

If you promise to marry him, marry him. \(({ I})\)

-

The fact that he is already married is an undefeated reason for you not to marry him. \(({ P})\)

-

So: Don’t promise to marry him. \((I^{\prime })\)

Indeed, the sufficient condition for validity provided by Theorem 4 is satisfied: P entails the prescription \((I^{*})\) “don’t marry him” (see §3), and (1) above (in Theorem 5) holds because (2) holds. Claim (2) holds because (a) the context of \(I^{\prime }\) entails the disjunction of the contexts of I and \(I^{*}\) (because the context of \(I^{*}\) is necessary), and (b) the violation proposition of \(I^{\prime },\) namely the proposition that you promise to marry him, entails that you marry him or you promise to marry him, which is equivalent to the disjunction of the violation propositions of I and \(I^{*}\) (namely of the propositions (i) that you promise to marry him but you do not marry him and (ii) that you marry him).

6.2 Invalid mixed-premise imperative arguments

The following theorem enables one to show that certain mixed-premise imperative arguments are not valid:

Theorem 6

If \(I^{\prime }\) is unconditional and P is consistent with the proposition that some fact undefeatedly supports \( I \& \sim I^{\prime }\) (i.e., the conjunction of I with the negation of \(I^{\prime }),\) then the mixed-premise imperative argument from I and P to \(I^{\prime }\) is not valid.Footnote 50

A first consequence of Theorem 6 is that the following argument is not valid (cf. Parsons 2013, p. 88):

Argument 35

-

Either marry him or dump him. (I)

-

You are not going to marry him. (P)

-

So: Dump him. \((I^{\prime })\)

Indeed, \(I^{\prime }\) is unconditional, and the proposition that some fact undefeatedly supports “marry him and don’t dump him” (which is \( I \& \sim I^{\prime },\) as one can show by using Definition 5) does not entail that you are going to marry him (people do not always do what there is an undefeated reason for them to do) and thus is consistent with P.Footnote 51 To see that the result that Argument 35 is not validFootnote 52 is intuitively acceptable, compare Argument 35 with the following two arguments:

Argument 36 | Argument 37 |

|---|---|

Either marry him or dump him. | Either marry him or dump him. |

You are not going to marry him, | You are not going to marry him, |

and you are not going to dump him. | and you are not going to dump him. |

So: Dump him. | So: Marry him. |

One gets an argument equivalent (see §2.1) to Argument 36 by adding to the premises of Argument 35 a declarative premise (“you are not going to dump him”). But adding declarative premises preserves validity. Therefore, if Argument 35 is valid, Argument 36 is also valid. Moreover, if Argument 36 is valid, Argument 37 is also valid (by symmetry). Since these relations between the three arguments are intuitively clear, if Argument 36 or Argument 37 is intuitively not valid, then Argument 35 is intuitively not valid either. But it should be intuitively clear that neither Argument 36 nor Argument 37 is valid: intuitively, from “do X or Y” and “you are not going to do X or Y” neither “do X” nor “do Y” follows. So Argument 35 is intuitively not valid either.Footnote 53

The reasoning in the previous paragraph relied on the claim that adding declarative premises preserves validity. This claim—call it Declarative Monotonicity—is a consequence of the General Definition and is intuitively acceptable, but might be rejected by proponents of non-monotonic pure declarative logics. I reply that my project in this paper is to defend a definition of deductive validity that yields as a special case the standard (monotonic) definition of validity for pure declarative arguments; defending that standard definition lies beyond the scope of this paper. So in this paper I assume that Declarative Monotonicity holds.Footnote 54

A second consequence of Theorem 6 is that the following argument is not valid:

Argument 38

-

If you drink (at the party), don’t drive (after the party). (I)

-

You are going to drink (at the party). (P)

-

So: Don’t drive (after the party). \((I^{\prime })\)