Abstract

This article illustrates how scenario planning (SP) and scenario analysis as can be conceptualised as practices contributing to an action research (AR) investigation of leadership development. The project described in this article was intended to strengthen leadership capacity in Australia’s rapidly changing aged care and community care sector. A research team comprising academics from three universities and managers from two faith-based not-for-profit organisations providing aged and community care participated in this study. As part of the research, two sets of scenario-based workshops were held: the first, to identify possible futures using SP; and the second, to deal with plausible scenarios these organisations are likely to face with the changes happening in the aged care environment in Australia by using scenario analysis. Although the researchers did not consider a link between practice theory and AR during the SP phase, practice theory became useful during the scenario analysis phase. The article includes a brief literature review followed by a discussion on the relationship between AR and practice theory. The processes used in the two sets of scenario workshops are then described in detail along with the data collected and analysed. The article concludes with some reflections on the use of scenarios in practice as well as an acknowledgment that practice theory would be useful in investigating leadership capability development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

This article is based on two sets of scenario planning (SP) workshops conducted as part of an Australian Research Council (ARC) Linkage Grant for ‘Developing a New Leadership Framework for Not-For-Profit Aged and Community Care Organisations in Australia’, awarded in 2010 to three Australian universities and two major faith-based not-for-profit (NFP) organisations providing aged and community care in Australia. The first set of workshops in 2007 was conducted prior to the award of the ARC grant as a collaborative research effort between one university and one faith-based organisation involved in the subsequent linkage grant. The two sets of workshops had different purposes: the first, to identify possible futures in the Australian aged care sector (SP); and the second to deal with scenarios (scenario analysis) using the future that may occur in the rapidly changing aged and community care sectors in Australia.

The research team for this project had three very experienced action researchers who have a strong interest in the connection between theory and practice. The principal author (an experienced action researcher) became a core researcher for the Centre for Management and Organisation Studies at his university as the research progressed. This put him in contact with organisation studies scholars using practice theory in their research and inspired him to make a link between practice theory and action research (AR) in this research project.

Background

Aged and community care is a growing sector. Many countries are experiencing rapidly ageing populations (OECD 2005). Associated with population ageing is an increasing demand for aged and community care services within the population (Institute of Medicine 2001).

NFP organisations (henceforth NFPs) are major providers of aged and community care in most countries (Weiner et al. 2007). Heightened demand for services, combined with workforce shortages, increasing competition with other providers, reduced government support and complex regulatory requirements are undermining the operational capacity and financial viability of many organisations (Pieteroburgo and Wernet 2010). In order to respond to these challenges, high-quality leadership of aged and community care NFPs is required.

The research project that gave rise to this article began in 2005 as a management development consultancy for Lutheran Community Care (LCC), Queensland. A faith-based Australian NFP, LCC is ‘one of Queensland’s largest providers of aged care, family services, disability services and hospital chaplaincy’ (http://lccqld.org.au/history). It operates more than 30 facilities in urban and regional Queensland and employs more than 1,000 staff and volunteers. It operates retirement villages, nursing homes, community care and day respite.

During the initial consultation at LCC to plan their management development program, the CEO and the consultants felt that the managers also needed leadership skills to deal with the uncertain and rapidly changing environment that they were facing.

It was then decided to apply for a collaborative research grant involving LCC and Southern Cross University (SCU), which several of the authors of this article were associated with. The aim of the research was to develop a new ‘leadership framework for not-for-profit aged and community care organisations in Australia’. A workshop with managers of LCC to discuss their needs for leadership development was planned. In addition, as aged care was undergoing rapid change, due to changes in government regulations as well as the impending retirement of ‘baby boomers’, a ‘scenario planning’ workshop was organised with a diverse sample of relevant stakeholders from government, the community, academics and practitioners. The first project discussed in this article is based on that workshop.

Upon completion of the collaborative research project an application was made for a federally funded research grant to test the leadership framework developed in the first research project. By this time two more universities, the University of Technology Sydney (UTS) and the University of Southern Queensland (USQ) as well as another large NFP faith-based organisation providing aged care and community care, Baptist Community Services (BCS), operating in New South Wales and the Australian Capital Territory, became interested in the research and an Australian Research Council (ARC) grant was applied for and secured in 2010.

‘Baptist Community Services is a leading not-for-profit Christian care organisation that has been serving the aged and people living with disadvantage for the past 65 years’ (http://www.bcs.org.au/AboutBCS.aspx). BCS employs more than 3,600 staff and has 1,000 volunteers. It has more than 160 facilities under two operating divisions—BCS AgeCare and BCS LifeCare.

The ARC submission proposed that the leadership framework developed during the collaborative research project be tested using plausible scenarios that managers of LCC and BCS may have to contend with in the future. The second project discussed in this article is based on the scenario analysis workshops held in 2012.

Brief Literature Review

A brief literature review of SP is provided in this section to support the decision to use scenario-based workshops as an intervention strategy.

Scenario Planning

The SP process used in the first workshop was based on a description in the book The Sixth Sense: Accelerating Organizational Learning with Scenarios (van der Heijden et al. 2002) and the experiences of two facilitators familiar with large group intervention processes, one of whom was also an experienced facilitator of search conferences (SCs). The reason a SP process was preferred over a SC is discussed later in this section.

Ramirez et al. (2008, p. 5) note that ‘scenarios are descriptions of plausible future contexts in which we might find ourselves’, a primary aim of the first project. Other key characteristics of scenarios include their use in the definitions: ‘internally consistent view of the future’, ‘how organisational decisions may be played out in the future’, ‘managing the uncertainties of the future’ (Chermack et al. 2001) and as ‘stories of multiple futures … that are analytically coherent and imaginatively engaging’ (Bishop et al. 2007). Therefore, coherence, consistency and action plans to deal with scenarios are also important aspects of SP.

Schoemaker (1995) points out that scenarios do not actually predict or forecast the future. Instead, they help to challenge the current paradigms of thinking and prepare managers to start paying attention to stories about the future that they might normally overlook. Varum and Melo (2010, p. 356) note that scenarios are more useful as an approach to strategy focused on process rather than for finding an optimal strategy; as a tool to improve decision-making in uncertain conditions; in helping managers to recognise, consider and reflect on situations they are likely to face; and also in helping organisations to avoid tunnel vision. Thus, SP is particularly useful for managers of organisations that face an uncertain and rapidly changing environment, the situation being faced by LCC when the SP was undertaken.

Purpose

Several authors have discussed the purposes of using SP (Mietzner and Reger 2005; Ratcliffe 2002; Neilson and Wagner 2000; Ramirez et al. 2008; Selsky and McCann 2008). These can be summarised as:

-

1.

Present alternative images instead of extrapolating from the past. Challenge assumptions about the ‘official future’.

-

2.

Allow for sharp discontinuities to be evaluated.

-

3.

Make decision-makers question their assumptions.

-

4.

Create a learning organisation by fostering strategic thinking and learning.

-

5.

Create frameworks for a future vision.

-

6.

Establish contexts for planning and decision-making.

-

7.

Understand how the future would look, why it might come about and how this is likely to happen.

-

8.

Outline the actions an organisation can take if certain situations arise.

Selsky and McCann (2008, pp. 170–171) suggest that organisations may face operational, competitive or contextual disruptions. Operational disruptions occur due to normal fluctuations in supply, demand and price that can be taken care of by policies, rules and structures. Competitive disruption can be caused by the market situation affecting competitive advantage and this is usually where strategic planning, manoeuvring, positioning, alliancing and developing new capabilities might be useful. Contextual disruptions are less predictable as they fall under the description of ‘unknown unknowns’ that can have damaging consequences or give rise to potential opportunities. Traditional strategic planning is not useful to face such disruptions. SP was more useful in dealing with contextual disruptions (which LCC was facing when a SP workshop was planned for the first research project).

Typology

Several attempts to create a typology of SP were also found in the literature reviewed. One of the better attempts at typology was by Börjeson et al. (2006) who classified scenarios as predictive, explorative and normative. Predictive scenarios are often used to answer the question, What will happen? Predictive scenarios are usually in the form of forecasts or what-if scenarios. Explorative scenarios are used to figure out, What can happen? This can result in external scenarios that focus on external factors beyond the control of actors involved. They can also lead to strategic scenarios to help formulate policy measures to cope with issues at stake. Normative scenarios usually answer the question, How can a specific target be reached? They result in preserving scenarios to find ways to achieve the target by making changes to the current situation. The SP used at LCC was an exploratory industry scenario with a focus on the future of the aged and community care industry sector.

Theory

Ramirez et al. (2008) state that biologist von Bertalanffy (1950) and psychiatrist Ashby (1960) promoted the idea of systems being open to social psychologists, which later influenced the thinking of strategic planners in organisations to take into account the influences of the environment. The theoretical foundations of SP in organisations can be traced to Causal Textual Theory (CTC) developed by Emery and Trist (1965). The texture was an aid to understand and classify the environmental complexity and uncertainty that were being experienced by many managers at that time and find suitable ways to deal with these. A second important influence on Emery and Trist’s thinking came from Lewin’s work on AR (Lewin 1952) to engage with the social world to understand it better.

Emery and Trist (1965, p. 22) identified four possible links with systems and their environment. They describe it as four sets using the letter L for ‘potential lawful connections’ suffix 1 to refer to the organization and suffix 2 to refer to the environment:

L11 denotes processes within an organization.

L12 and L21 are exchanges between an organization and its environment with L12 linking the organization to its environment and L12 linking the environment to the organization.

L22 refers to processes that link parts of the environment outside the organization.

Emery and Trist (1965, pp. 24–27) then developed causal textures as existing in the ‘real world’ of most organizations (Ramirez et al. 2008, p. 19). These were:

-

1.

Placid Randomized with the most salient connection being L11.

-

2.

Placid clustered with most salient connections being L11 + L21.

-

3.

Disturbed reactive with most salient connections being L11 + L12 + L21.

-

4.

Turbulent fields with the most salient connections being L11 + L12 + L21 + L22.

The Type 4 texture is the most challenging, presenting situations characterised by wicked problems (Rittel and Weber 1973), messes (Ackoff 1979) or meta-problems (Selsky and Parker 2005). According to Ramirez et al. (2008, p. 26) ‘scenarios are considered to be methods to assess the causal texture by considering how L22 forces in the contextual environment interact systemically to affect a set of transactional environment (L12 and L21) possibilities’. To the researchers involved in the project this represented the situation facing the aged care sector in Australia. The use of SP was appropriate to deal with the situation that managers from aged care organisations experience.

Scenario Planning and Search Conference

Jiménez (2008, p. 42) differentiate between SP and SC as follows:

-

1.

SP focuses on one actor (e.g. a company) with the aim of helping this actor best address the turbulence it faces while SC focuses on an issue for which different stakeholders try to find common ground to build a desired future.

-

2.

Construction of scenarios is the visualisation of possible futures according to what we have now and the drivers detected in the environment whereas an SC produces one desired future to be approached gradually over the next 10–15 years.

-

3.

SC is a set of reference projections on what can happen in the future. The product of the SC is the image of a future desired by all the stakeholders present and a set of courses of action that stakeholders will carry out to approach the desired future.

As such, the researchers felt that SP was a more appropriate intervention strategy in LCC even though they were more familiar with conducting SCs.

Moreover, Wilkinson (2008, p. 300) states that ‘The skill of twentieth century leadership is not in knowing more about the future but in being able to enact different realities today. It also involved nurturing a strategic capability to deploy different futures methods’. Thus, it was also useful to use a different methodology to engage leaders at LCC to help with their development as well.

Leadership Development in NFP Organisations

While a great deal of work has been done on developing leadership capability frameworks for the for-profit and public sectors, very little research has been done on such frameworks for the NFP sector. However, there may be useful lessons to be learned from the development of leadership competencies in both the for-profit sector and the public service (APSC 2001). This project was the first study of its kind in Australia to create a leadership capability framework for NFPs. As such, it was expected to help fill a knowledge gap in this area and provide the theoretical underpinnings to provide an evidence base for leadership development in the NFP sector.

In this article, ‘leadership’ is defined as a capability that goes beyond the standard parameters of operational management to include a strategic capacity and difficult-to-define attributes such as innovation and vision, as well as a justified confidence in using these attributes in an organisational role. Capability is defined as mastery over a range of tasks or functions acquired through experience (professional and personal) and training (formal and informal). The term ‘capability’ is differentiated from ‘competency’, which is seen as an ability to undertake a range of tasks or functions. In this sense, capability can be seen as a meta-competency that integrates the relevant competencies, experience and knowledge into a coherent set of behaviours.

There appears to be a lack of research in Australia on leadership capability development in the aged and community care sectors among NFPs. A review of articles from 1998 to 2005 in the journal Nonprofit Management and Leadership found that the majority of articles dealing with leadership focused on leadership at the board or governance level, although Alexander et al. (2001) propose a leadership model for a community care network that is collaborative and not based on authority and hierarchy. None of the articles reviewed discussed a leadership framework for NFPs, leadership competency and capability, or leadership requirements of Senior Operational Managers working in NFPs.

Therefore, it was felt that there was a need to investigate leadership capability development in the NFP sector, focusing on organisations involved in aged and community care. The results of such a study were expected to contribute to knowledge that would be beneficial to all NFPs providing services to the public in an environment where both the private and public sectors also play a role in Australian society.

Research Questions

The main research question for this project was:

What is an appropriate leadership capability framework for NFPs in the aged and community care sectors in Australia?

To answer the main research question, the following corollary questions needed to be addressed and these were the basis for the SP workshop:

-

1.

What are the challenges faced by senior managers of NFPs in Australia?

-

2.

What are the competencies required by senior managers in NFPs in Australia to address these challenges?

-

3.

What are the leadership capabilities expected of senior managers in NFPs in Australia to address these challenges?

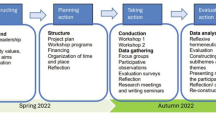

In order to investigate these questions, a research project was designed in three phases using AR as a meta-methodology (Dick 2002). The design changed as the steering committee set up to evaluate the progress and outcomes from each stage of the research reflected on ways to move forward with the research to deliver the benefits that stakeholders (the two partner organisations) wanted. Table 1 shows how the research cycles changed during the research.

The scope of this article is limited to the two SP workshops used in the pilot project and the two scenario analysis workshops used in the ARC project, as a reconceptualisation of what was done in these workshops. While both projects used several methods to carry out the research, the underlying philosophy for both was AR. In other words, AR was used as a meta-methodology in both projects. Provision was made in both projects to reflect on the research from time to time, with a view to modifying the research process based on what was found in the previous step of the research.

Practice Theory

Kemmis (2009) links AR to practice theory, noting that Schatzki (2012) defines practice as ‘an open-ended, spatially–temporally dispersed nexus of doings and sayings’. Kemmis adds that (Kemmis 2009, pp. 463–464) ‘Action research happens in sayings, doings and relatings—both in the conduct of AR itself and in the justification of AR’. He also classifies AR as technical—for improving control over outcomes, practical—to educate and enlighten practitioners; and critical—to emancipate people and groups. In the research project, our intention in conducting scenario analyses was mainly a form of practical AR although also contributing to critical AR.

Corradi et al. (2010) state that one way practice could be conceptualised is ‘as what people do’. This concept has been used by organisational researchers in strategy research (Jarzabkowski et al. 2007; Kornberger and Clegg 2011; Whittington 2003). Corradi et al. (2010, p. 272) elaborate further that the practice perspective ‘seeks to identify the strategic activities reiterated in time by the diverse actors interacting in an organisation’.

The philosophical approach to practice entails the premise that social reality is fundamentally made up of practices, i.e. rather than seeing the social world as external to human agents or as socially constructed by them, this approach sees it as being brought into reality through everyday activity. Orlikowski (2002, p. 252) states that ‘knowing is an ongoing social accomplishment, constituted and reconstituted in everyday practice’. This corresponds with the notion of ‘knowing-in-action’ proposed by prominent action researchers like Schön (1983). While some action researchers like Kemmis (2009) have suggested links between AR and practice theory, others feel that AR is not being seriously considered by management researchers to investigate practices. According to Coghlan (2012, p. 79), ‘In the context of management and organisation studies the potential of AR has not been fully realized as organisational scholarly research that both produce robust and actionable knowledge [sic]’.

Vaara and Whittington (2012, p. 1), who have provided a comprehensive review of studies of strategy-as-practice, state that these studies have ‘provided important insights into the tools and methods of strategy-making (practices), how strategy work takes place (praxis) and the role and identity of the actors involved (practitioners)’. Their review lists several examples of studies of practice at NFPs and two examples of applying AR to study practice. The first is a study by Heracleous and Jacobs (2008), who investigated the process of strategy making by crafting embodied metaphors at a workshop where participants used physical artefacts to create and interpret strategy at the same time. The second study is by Eppler and Platts (2009), who investigated visualisation methods used in five organisations for understanding and generating strategy. SP also uses visualisation methods to make sense of the large amount of information presented to the participants in a SP workshop and often used in formulating future strategies.

Although the ‘practice lens’ has been used prominently in strategy research there is a call for leadership researchers to use it to study leadership and challenge the competency paradigm that has dominated the study of leadership (Carroll et al. 2008). Although the research project described in this article has differentiated between ‘competency’ (knowledge and skills leaders possess) and ‘capability’ (what leaders do when using their competencies), using a practice lens is an interesting idea, further explored in this article while describing the scenario analysis phase of the project.

The practices used in the leadership development project could be depicted as three interlinked sets of practices investigated in an AR intervention using the model proposed by Cronholm and Goldkuhl (2004, p. 54) as shown in Fig. 1.

Three interlinked practices (developed for this article based on Cronholm and Goldkuhl 2004, p. 54)

The three interlinked practices in the overall leadership development research project are:

-

1.

Investigation of the leadership development research practice assigned to the research team by the funders of the research project—the ARC and the two NFPs (LCC and BCS).

-

2.

The use of SP to identify possible future of the aged care scenarios in Australia for LCC by the consultants and stakeholders that became the seed for the ARC linkage grant.

-

3.

The use of scenario analysis by the research team from the three universities (SCU, UTS and USQ) and the managers of the two NFPs (LCC and BCS).

SP Workshops

A criticism of leadership capability frameworks that were reviewed in the literature is that they are based on what leaders are doing now rather than what they are expected to do in the future. This was particularly significant for NFPs as they are increasingly taking on roles that used to be the responsibility of the public sector, and are also facing increased regulation and public scrutiny. Therefore, the first step in this research was to hold two workshops using SP to envision and study possible futures for NFPs over the next 10 years (Schoemaker 1995):

-

1.

Workshop 1 involved a wide sample of stakeholders.

-

2.

Workshop 2 involved a more focused sample of stakeholders, and focused on the competencies and capabilities that leaders might require to deal with the impact of scenarios developed in the first workshop.

Both workshops were facilitated by an experienced consultant familiar with conducting future-planning processes. Prior to each workshop, the facilitator used a modified, two-stage, email-based Delphi process to obtain and prioritise relevant data about the sector and its environment.

For Workshop 1, participants were asked to complete an online questionnaire about the external and internal factors that might affect the NFP aged and community care sector in the future. This was done in order to generate a broad picture of the current environment of the NFP sector. Responses to the questionnaire were collated and returned (unedited and unattributed) to the participants for prioritisation.

In this, second, prioritisation stage, the same method was used for each workshop; each participant was given ten votes for each category and asked to indicate how many votes they wished to place on a particular item. In this way, participants were able to indicate the degree of importance of the issue for them. The prioritised responses were then tabulated and presented at the workshop. Participants used this information to develop possible scenarios which NFPs may face over the next 10 years.

For Workshop 2, a new group of participants also completed an online questionnaire in which they were asked to match specific capabilities required of leaders in each of the possible future scenarios developed in Workshop 1. Participants were advised that while all of the scenarios did not have equal probability of occurring, they were all possible and so leaders of NFPs must be able to respond effectively to any of these scenarios. This was done in order to generate a comprehensive list of capabilities that would enable an NFP aged and community care leader to operate effectively in any situation. That is, by preparing for the worst, NFPs are preparing for all possible situations.

Responses to the questionnaire were again collated and returned (unedited and unattributed) to the participants for prioritisation. The prioritised responses were then tabulated and presented at the workshop.

Data Analysis

Qualitative data obtained from the workshops and interviews were recorded (with permission of the participants) and transcribed, themes were analysed and these contributed to the development of the draft framework.

Framework Development

Data from the workshops and interviews, in conjunction with an updated and revised literature review, were used to develop the first draft of a leadership capability framework, which was the major outcome of the pilot study.

Results

Workshop 1

The goal of the first workshop was to develop possible future scenarios facing the NFP aged and community care sector in the next 5–10 years, using the factors identified from the Delphi process that was conducted prior to the workshop (29 people participated in this component). In the Delphi process, participants were asked to consider the following issues that may shape the future of NFPs:

-

1.

Main factors outside the aged and community care sector that are most likely to influence its viability and direction over the next 10 years.

-

2.

Main factors within the aged and community care sector that are most likely to influence its viability and direction over the next 10 years.

-

3.

The major impacts of these internal and external factors on the aged and community care sector.

Several external and internal factors were identified by the participants at the workshop. After analysing the external and internal factors recorded at the workshop, the following were summarised as the factors that had major impacts on the industry. The results from the workshop are reported in Table 2.

A face-to-face workshop was then held with the majority of the participants who took part in the Delphi process. Participants’ roles included minister of religion, academic expert, aged or community care practitioner, CEO, board member, general manager and director of nursing.

The participants collectively developed four possible scenarios for the NFP aged and community care sector for the next 10 years. Possible future scenarios identified were (the metaphors in parentheses are often used in SP to visualise the scenario):

-

Business as usual (steady as she goes)—This scenario was based on an organisation that did nothing to accommodate current and future sector change. In this scenario, NFPs would be forced to provide fewer services due to a reduction in staffing levels and increased costs. The quality of services would also be affected by workforce shortages and rising costs. This scenario entailed a loss of clients due to poor services and poor public image. Inevitably, under this scenario, NFPs would have difficulty providing any service at all, have difficulty meeting workers’ entitlements (superannuation etc.) and would eventually collapse under the weight of increased accreditation and reporting requirements that they would not be able to meet. This scenario was regarded by all as not a real option.

-

Globalisation (winds of change)—This scenario entailed an increasing incursion into the NFP aged and community care sector by for-profit organisations (including from outside Australia) and a resultant decrease or shift in client base for NFPs. This scenario also included changing government funding models under the influence of large for-profit groups and an eventual drop in competition (once NFPs began to disappear and a small number of for-profits remained). This scenario featured reduced community involvement, rigid working conditions for staff and a shift from a market-driven model to a provider-driven model.

-

Whole-of-sector change (turbulent waters)—This scenario featured the currently occurring whole-of-sector change. In this scenario, NFPs would be required to accommodate dramatic changes to funding models, staffing models and service delivery models as a result of regulatory change, shifts in demography and changing client attitudes.

-

Natural disaster or crisis (tsunami)—This scenario featured an unpredictable natural disaster such as a pandemic (e.g. avian influenza) or a tsunami. In this scenario, NFPs’ ability to plan and prepare was featured as well as a need for NFPs to go back to basics (core clinical services). This scenario emphasised the need for leadership in times of crisis (and the reality that such leadership may emerge from anywhere in the organisation and not just from the top), the need for emergency management, the intervention of governmental agencies to establish priorities and manage vacancies and the sudden and dramatic change in community expectations and needs that would result from such a disaster.

An underlying principle of the scenario-building workshop (Workshop 1) was that if NFPs prepare for a small number of reasonably difficult possible scenarios then, in effect, they are preparing to deal, generally, with the unexpected.

Workshop 2

The purpose of the second workshop was to assess the possible impacts of the four future scenarios on NFPs in the aged and community care sector and to identify leadership capabilities that may be required to deal with those impacts.

The 19 participants included board members, CEO, general managers, directors of nursing and an academic.

Using the prioritised results from the second Delphi questionnaire as points for discussion, the participants collectively developed a lengthy list of possible capabilities and competencies required of leaders for each future scenario for the NFP aged and community care sector for the next 10 years.

In order to meet the challenges associated with the possible future scenarios, questionnaire respondents were asked what they thought were the main and additional competencies needed by NFP aged and community care managers. Table 3 presents the competencies as prioritised by participants of Workshop 2.

Overwhelmingly, participants selected personal qualities, particularly values, as the main attributes for leadership capability. The qualities selected are shown in Table 4.

It was proposed that this list of capabilities/competencies and attributes will enable leaders of NFPs to respond effectively to any of the possible scenarios. These capabilities are very similar to those later identified in the in-depth interviews, showing an alignment between the data collected by the two methods (workshops/interviews).

Scenario Analysis as Practice in Leadership Research

Wilson (2000, p. 23) states that ‘although developing coherent, imaginative and useful scenarios is certainly important, translating the implications of the scenarios into executive decisions, and ultimately, into strategic action was the ultimate reason and justification for the exercise’. Therefore, the research team asked managers at LCC and BCS to work with plausible scenarios towards the end of the ARC research project. These scenarios were built with the help of one of the authors of this article, who was familiar with the changes to the aged care sector being proposed by the Productivity Commission Report into aged care in Australia (Productivity Commission 2011). The general managers at LCC and BCS were well aware of the critical changes that could occur in their organisations as a consequence of the implementation of that report and their perspectives were also incorporated. At the end of the scenario, the participating managers were asked to comment upon the leadership framework that was developed during the first project.

Scenario analysis was also undertaken to enhance organisational learning. Stauffer (2002, p. 5) quotes Gage about the value of using scenarios as ‘team members still learn a lot about each other, how they might react under different extreme circumstances. That way each member is less likely to be thrown for a loop by the later crisis behaviour of another member. The process itself builds mutual trust. You work better together and tend to be more open and less guarded’.

Scenario-based Workshop 2 (Scenario Analysis)

This section describes the process and results of four facilitated sessions to elicit information from managers about the leadership skills, qualities and capabilities required in faith-based NPOs. The sessions were scenario-based. There were four groups in all, two at BCS and two at LCC, (n = 11, 14, 14 and 11, respectively). The participants were managers drawn from different parts of the two services.

Process

The purpose of these workshops was to provide data to be triangulated with other data collected as part of the overall study. To improve the triangulation, the process was designed to increase the differences between this data set and the previous data. The scenarios were specific and realistic rather than abstract, and future oriented rather than past or present oriented. The scenarios were, therefore, chosen by managers from the two services to reflect actual challenges to be faced in the near future. The scenarios used are described in the Appendix.

The workshop process used was designed to capitalise on these differences by encouraging realistic immersion in the scenarios by the participants. To achieve this, participants were asked to imagine, as vividly as they could, that they were part of BCS or LCC leadership, with responsibility for acting on the scenario. They were given time to read the scenario, without discussion. To make it easier for all to contribute to the small group in which they would work, they were encouraged to write their comments on the scenario sheet. Small groups of three or four participants, chosen to maximise the diversity within each group, were then set up.

The groups then worked through the following steps:

-

1.

They were asked, ‘As leader, in guiding your organisation through the change process, what would be your most important goals? What actions would you take to pursue those goals?’

-

2.

Each group reported on the most important goals they would pursue, and the most important actions they would take to pursue those goals. Participants were encouraged to take notes on goals and actions in other groups’ reports that they agreed were important.

-

3.

They were then asked, ‘What skills, qualities and capabilities would you require to be able to take those actions? What difficulties would you expect to face in carrying out those actions? What further skills, qualities and capabilities would you require to overcome those difficulties?’

-

4.

‘Skills, qualities and capabilities’ were collected publicly on an electronic whiteboard.

In addition, all sessions were recorded in their entirety on a digital recorder to allow the results to be later checked against the recorded data.

Identified Skills, Qualities and Capabilities

To collate these raw data, they were grouped by the facilitator into closely related clusters. The importance of each cluster was then estimated, taking into account how many workshops mentioned them, and how early in a workshop they were mentioned. Obviously, this is an interpretive task. Other people would most likely collate the items somewhat differently. In the interests of transparency, each interpretation is illustrated by a list of the items on which it is based. The collated results follow.

-

1.

Effective leaders are seen, above all, as good communicators who are both people oriented (team and individual) and action oriented The desired communication is two-way, consensual, respectful and people oriented. It is with the board and outside the organisation as well as within the organisation. It includes skills at negotiation and conflict management and an ability to provide mentoring and counselling. Leaders work in a team environment characterised by trust and diversity and balance their people orientation with a tenacious focus on strategic action and vision-driven results, aware of their faith.

-

2.

Personal qualities of leaders Leaders bring personal characteristics similar to those sometimes labelled ‘emotional intelligence’. Qualities include resilience, integrity, courage and flexibility.

-

3.

Leaders engage inspiringly with change Acting with passion, leaders engage with change innovatively, while tempered by realism and understanding. They do this in ways that motivate and inspire others.

-

4.

Leaders have a broad skills set Among other skills, they are consistent and discerning and aware of the tensions between market and mission, courage and service. They equip effective people while encouraging them to think differently.

Reflections

The purpose of the SP workshops in the first stage of the research was to open the eyes of the managers in LCC to look at how the future of aged and community care would appear from the perspective of a wide variety of stakeholders so that they could think about their own leadership capabilities required in the future.

Following are the reflections on the SP workshops by the authors who were present at the time:

-

1.

Valuable insights were gained into the different priorities and perspectives of the various roles within the organisation e.g. the pastors had a different priority list to the directors of nursing.

-

2.

The process was very effective in raising emerging issues in the industry and generating the scenarios, so satisfied the aim of the workshops.

-

3.

A modified version of SP, combining elements of a SC, worked well for the purpose. The SP was certainly a better option than a SC.

-

4.

In considering multiple and different futures, leaders are also considering at least indirectly how they might deal with other futures not predicted. Leaders prepared to deal with multiple futures are more flexible, and therefore better prepared for the unexpected.

-

5.

SP is a way of building resilience and flexibility into corporate or community strategy. At times of rapid change like the present, this is valuable (and perhaps crucial).

-

6.

The hesitance for the religious leaders to consider the worst case scenarios was interesting and showed the different values that the managers held.

The SP workshop relied upon the opinions of a few selected stakeholders on the possible scenarios as it was held in one city in Australia. While this was useful to get LCC’s managers to think differently the research team felt that the diversity of stakeholders present was not sufficient and therefore they had to follow this up with interviews in other cities of Australia to supplement the findings which was then used to develop a new framework for leadership development. The SP workshops also did not use a great deal of data and simulations due to limited resources (materials and budget) and relied on national statistics that were available.

The scenario analysis workshops had two purposes. One was to gather the opinions of the managers on the leadership capabilities that would be required to handle ‘realistic’ scenarios that were presented to them. The second purpose was to get their response on a leadership framework for NFP organisations that were developed during the first project.

The authors of the article who were present during the scenario analysis workshops had the following reflections:

-

1.

Compared with traditional SP, the scenarios used in these workshops were in the present or immediate future. They required immediate response.

-

2.

The purpose was not to influence planning. Each scenario was to act as a catalyst for participants to think about the nature of required leadership in their organisation.

-

3.

The scenarios were used to add to the quality of the conclusions we were trying to draw from our research program.

-

4.

The instructions given to participants set out to encourage people to treat the scenarios as real issues and to identify the actions that would be needed. The actions then became the evidence on which they would draw to define the requisite leadership capabilities.

-

5.

Participants were asked to consider what difficulties they would encounter in taking those actions, to increase the ‘realism’ of the exercise. The difficulties then became a further catalyst for thinking about the specific nature of leadership.

-

6.

There was great enthusiasm for the task in evidence among the participants.

-

7.

In line with our findings to date, communication in all its forms was almost universally seen as the most important leadership capability.

-

8.

The personal qualities of resilience, integrity, flexibility and courage were also highly regarded.

-

9.

The ability to passionately embrace change and the importance of having a broad skills set were the remaining areas highlighted in this workshop.

-

10.

There was much learning across a diverse sample of managers in the organisations.

-

11.

It was interesting to observe that after taking some time to settle down, the managers enthusiastically embraced the challenge of working on the scenarios.

The scenario analysis workshops were generally very productive but the researchers felt that in some of the workshops the presence of senior management could have inhibited middle managers to freely express their thoughts. The researchers did not have control over the selection of the sample of managers participating in the workshops and had to rely on the organisations to invite people based on the criteria provided. While the presence of religious leaders at the scenario workshops was observed to make a difference at the SP workshops this was not very evident at the scenario analysis workshops. Both the faith-based organisations have managers who operate in the aged and community care operations. The scenarios that were analysed focused on aged care issues and the managers who managed the community care operations would have found it difficult to contribute to the analysis even though the organisations want to practise job rotation between managers operating in the different areas.

Conclusions

The SP workshops helped to achieve the following results that were also pointed out in the literature.

Futures were predicted for the aged care industry instead of relying on what had happened in the past. It was realised that the industry is getting ready for a disruptive change that will affect the way business is conducted by LCC. There were challenges about the ‘official future’ while developing the alternate scenarios. The two workshops helped managers of LCC to think strategically by learning together to deal with the scenarios predicted by the stakeholders and to develop frameworks for a future vision for the organisation. Some thought was given to imagining how the future would look, how it might come about and how this was likely to happen.

Some purposes that were not found in the literature were also served, such as getting consensus around diverse views that existed in the organisation about the future. In an indirect way, this helped to question some of the assumptions managers held about the future as external stakeholders were also present. The workshops themselves served as a way of developing the managers who attended them. This confirmed the view that SP could lead to organisational learning.

The second set of workshops to carry out scenario analysis certainly served to highlight what the managers of the two organisations said, did and how they related while tackling the scenarios. To this extent, it also demonstrated the AR methodology used in this research to capture the ‘sayings, doings and relatings’ between the authors, who are researchers in this project, as well as the managers who are co-researchers in the process.

The scenario analysis workshops also provided an opportunity for mangers to come to terms with the complexities of the tasks given to them in analysing the scenarios as a group as well as to consider the environmental issues related to the scenarios. One of the authors observed that these workshops could have served to provide the ‘requisite complexity’ to the managers present. This resonates with the findings of Hannah et al. (2011, p. 231), who state that in leadership development ‘individual complexity must be requisite to the task and relevant groups or networks, and collective complexity must be matched to group tasks and organisational environments’.

The two sets of workshops—SP and scenario analysis—have provided the researchers in the project some valuable feedback about the capabilities required by leaders in NFP faith-based organisations.

The use of scenarios in different modes has certainly been useful in leadership research in practice. While practice theory was not explicitly used in the SP it became evident that the ‘practice lens’ was valuable in retrospectively looking at the ‘sayings, doings and relatings’ at the scenario analysis workshops. The authors agree with Carroll et al. (2008) that using a ‘practice lens’ would be very valuable in the ongoing research activities for this project.

References

Ackoff R (1979) The art of problem solving. Wiley, New York

Alexander JA, Comfort ME, Weiner BJ, Bogue R (2001) Leadership in collaborative community health partnerships. Nonprofit Manag Leadersh 12(2):159–175

APSC (2001) Senior leadership capability framework. Australian Public Service Commission, Canberra. http://www.apsc.gov.au/selc/index.html. Accessed 15 June 2006

Ashby WR (1960) Design for a brain: the origin of adaptive behaviour, 2nd edn. Chapman & Hall, London

Bishop P, Hines A, Collins T (2007) The current state of scenario development: an overview of techniques. Foresight 9:1–25

Börjeson L, Höjer M, Dreborg K-H, Ekvall T, Finnveden G (2006) Scenario types and techniques. Futures 38:723–739

Carroll B, Levy L, Richmond D (2008) Leadership as practice: challenging the competency paradigm. Leadership 4:363–379

Chermack TJ, Lynham SA, Ruona WEA (2001) A review of scenario planning literature. Future Res Q 17(2):7–31

Coghlan D (2012) Action research: exploring perspectives on a philosophy of practical knowing. Acad Manag Ann 5:53–87

Corradi G, Gheradi S, Verzelloni L (2010) Through the practice lens: where is the bandwagon of practice-based studies heading? Manag Learn 41:265–283

Cronholm S, Goldkuhl G (2004) Conceptualising participatory action research: three different practise. Electron J Bus Res Methods 2:47–58

Dick B (2002) Postgraduate programs using action research. Learn Org 9(4):159–170

Emery F, Trist E (1965) The causal texture of organizational environments. Hum Relat 18:21–32

Eppler MJ, Platts KW (2009) Visual strategizing: the systematic use of visualization in the strategic planning process. Long Range Plan 42:42–74

Hannah ST, Lord RG, Pearce CL (2011) Leadership and collective requisite complexity. Org Psychol Rev 1:215–238

Heracleous L, Jacobs CD (2008) Crafting strategy: the role of embodied metaphors. Long Range Plan 41:309–325

Institute of Medicine (2001) Improving the quality of long-term care. National Academy of Science, Washington, DC

Jarzabkowski P, Balogun J, Seidl D (2007) Strategizing: the challenges of the practice perspective. Hum Relat 60:5–27

Jiménez J (2008) How do scenario practices and search conferences complement each other? In: Ramirez R et al (eds) Business planning in turbulent times: new methods for applying scenarios. Earthscan, London, pp 17–30

Kemmis S (2009) Action research as a practice-based practice. Educ Action Res 17:463–474

Kornberger M, Clegg S (2011) Strategy as performative practice: the case of Sydney 2030. Strateg Org 9:136–162

Lewin K (1952) Field theory in social science: selected theoretical papers. Tavistock, London

Mietzner D, Reger G (2005) Advantages and disadvantages of scenario approaches of strategic foresight. Int J Technol Intell Plan 1:220–238

Neilson RE, Wagner CJ (2000) Strategic scenario planning at CA International, 12 Jan/Feb 2000

OECD (2005) OECD factbook: an essential tool for following world economic, social and environmental trends. OECD, Paris

Orlikowski WJ (2002) Knowing in practice: enacting a collective capability in distributed organizing. Org Sci 13:249–273

Pieteroburgo J, Wernet S (2010) Merging missions and methods: a study of restructuring and adaptation in non-profit healthcare organisations. J Healthc Leadersh 10:69–81

Productivity Commission (2011) Caring for older Australians: draft inquiry report. Productivity Commission, Canberra

Ramirez R, Selsky JW, van der Heidjen K (2008) Business planning for turbulent times: new methods for applying scenarios. Earthscan, London

Ratcliffe J (2002) Scenario planning: an evaluation of practice. School of Construction and Property Management, University of Salford, Salford

Rittel H, Weber M (1973) Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sci 4:155–169

Schatzki T (2012) A primer on practices: theory and research. In: Higgs J et al. (eds) Practice-based education. http://www.csu.edu.au/research/ripple/publications/publications/Schatzki-110721-Primer-on-Practices.pdf. Accessed 12 Jan 2012

Schoemaker PJH (1995) Scenario planning: a tool for strategic thinking. Sloan Manag Rev 36(2):25–40

Schön D (1983) The reflective practitioner: how professionals think in action. Basic Books, New York

Selsky JW, McCann JE (2008) Managing disruptive change and turbulence through continuous change thinking and scenarios. In: Ramirez R et al (eds) Business planning in turbulent times: new methods for applying scenarios. Earthscan, London, pp 167–186

Selsky J, Parker B (2005) Cross-sector partnerships to address social issues: challenges to theory and practice. J Manag 31:849–873

Stauffer D (2002) Five reasons why you still need scenario planning. Harvard Management Update, pp 3–5

Vaara E, Whittington R (2012) Strategy-as-practice: taking social practices seriously. Acad Manag Ann 1–52

van der Heijden K, Burt G, Cairns G, Wright G (2002) The sixth sense: accelerating organizational learning with scenarios. John Wiley, Chichester

Varum CA, Melo C (2010) Directions in scenario planning literature—a review of the past decades. Futures 42:355–369

Von Bertalanffy KL (1950) An outline of general system theory. Br J Philos Sci 1:134–165

Weiner J, Tilly J, Howe A, Doyle C, Cuellar A, Campbell J, Ikegami N (2007) Quality assurance for long-term care: the experiences of England, Australia, Germany and Japan. Public Policy Institute, http://www.theceal.org/downloads/CEAL_1183152108.pdf. Accessed 16 Jan 2012

Whittington R (2003) The work of strategizing and organizing: for a practice perspective. Strateg Org 1:117–125

Wilkinson A (2008) Postscript. In: Ramirez R et al (eds) Business planning in turbulent times: new methods for applying scenarios. Earthscan, London, pp 295–304

Wilson I (2000) From scenario thinking to strategic action. Technol Forecast Soc Chang 65:23–29

Acknowledgments

The study to which this paper relates was funded by a grant from the Australian Research Council’s Linkages Program. The research team included researchers from Southern Cross University (SCU), the University of Technology Sydney (UTS), University of Southern Queensland (USQ) and Industry Partners Lutheran Community Care (LCC) and Baptist Community Services (BCS). An earlier developmental version of this paper was presented at the 12th EURAM conference, 6th–8th June, Rotterdam to seek feedback. The authors thank the anonymous reviewers of the conference and Systemic Practice and Action Research for their valuable comments that has helped in improving this article. Permission has been obtained by EURAM to publish this paper in this journal.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Sample Scenarios

Appendix: Sample Scenarios

BCS, Morning Session, Scenario

Recruitment and Retention of Staff

The Federal Government has just handed down its Budget for 2011 and its major focus is on job creation with significant funding going to training of the long-term unemployed, persons with a disability and young people. Your organisation has the opportunity to be involved in providing cadetships and training programs to boost staffing levels and skill mix in your facilities. In light of these training opportunities your organisation has decided to review its processes for recruitment, selection and retention of staff. You have been given the opportunity to participate in this process and have been encouraged to bring innovative and new ideas to the table. Your employer would like the focus of this review to include planning and solutions in the medium and long term that respond to predicted future increases in clients requiring care due to population ageing and increasing rates of disability and chronic disease.BCS, afternoon session, scenario

It is 1 July 2012.

Following an extensive investigation of options for aged care reform and the development of a new industry blue-print by the Productivity Commission, the minority Federal Government developed legislation to enact the key components of the Commission’s findings.

Regrettably, the legislation did not pass the House of Representatives when it went to the vote in June because the opposition and some independents voted against it. Several issues key to the reform package had become divided along party lines including:

-

The plan to abolish Residential Aged Care bed licences and restrictions on the number of community care packages after 2017 and the opening of the market to competition from any eligible provider. The need for aged care recipients to contribute more to the cost of their care and accommodation (except supported residents)

-

Allowing accommodation bonds for all Residential Aged Care and removal of the distinction between high and low care.

-

The reverse mortgage proposal was labelled “A great big new death tax”.

Due to the failure of these reforms, the existing weaknesses of the aged care system will only get worse:

-

It is increasingly uneconomic to build new high care beds or to replace or upgrade ageing buildings used for high care—services already lose more than $18 per day on average for every high care bed they have (with the exception of ‘extra services’ beds)

-

Government funding has not kept up with increases in costs, especially labour and energy costs, for many years and more than 70 % of services nationally are now operating in deficit

-

The demand for low care has been dropping because of the increased availability of in-the-home support. Not only are vacancy rates increasing but the amount held in accommodation bonds is reducing fairly rapidly.

-

The availability of Community Care packages to address the rapidly growing and higher care needs of the ageing Australian community will remain constrained and unable to meet demand.

-

The funding (both government and private) that would have enabled the payment of more competitive wages to care staff will not become available.

Incidentally, a medium sized for-profit aged care provider in Victoria has recently appointed administrators because of trading difficulties. The administrators have declared the services to be unviable and are now seeking to sell the assets which include some services on valuable inner-city land.

You are part of the executive management team of a medium sized faith-based aged care provider in NSW. How will you respond to the circumstances in which the industry now finds itself? LCC, morning session, scenario

In 2011 the Productivity Commission released a detailed options paper for redesigning Australia’s aged care system to ensure it can meet the challenges facing it in the coming decades.

The Australia Government, in its consideration of the Productivity Commission’s recommendations, endorsed some but not all of the options that were proposed. The reforms that were endorsed include the following:

-

1.

Changes to regulatory restrictions on community care packages and residential aged care bed licenses:

-

a.

Removing restrictions on the number of community care packages and residential bed licenses;

-

b.

Removing the distinction between residential high care and low care places;

-

a.

-

2.

Changes to regulatory restrictions on residential accommodation payments:

-

a.

Introducing accommodation bonds for all residential care that are uncapped and reflect the standard of the accommodation;

-

a.

-

3.

Changes to co-contributions across community and residential care:

-

a.

Co-contribution rate set by government;

-

b.

Means testing co-contributions according to the ability of the client to pay;

-

c.

Placing a lifetime limit on co-contributions so that excessive costs of care cannot totally consume an older person’s accumulated wealth—the limit determined by an independent regulatory commission;

-

a.

-

4.

Provision of residential care to those of limited means:

Providers required to make available at proportion of their accommodation to supported residents;

This obligation will be tradable between providers within the same region;

-

5.

Introduction of a single gateway into the aged care system

-

a.

The establishment of an Australian Seniors Gateway Agency that provides information, assessment, care coordination and carer referral services delivered via regional networks;

-

a.

-

6.

Consumer choice

-

a.

Individuals can choose which approved provider or providers they wish to access in order to obtain the specific services that the Gateway Agency decides they are entitled to;

-

b.

Block funding of programs will be replaced with funding according to consumer entitlement at the individual level;

-

a.

-

7.

Housing regulation

-

a.

De-coupling of regulation of retirement villages and other specific retirement living options from regulation of aged care;

-

a.

-

8.

Workforce

-

a.

Promotion of skills development of aged care workforce through expansion of courses to provide aged care workers at all levels with the skills they need.

-

a.

Key recommendations that were not endorsed included the following:

-

Increased remuneration for the paid aged care workforce;

-

Establishment of an Australian Pensioners Bond scheme to allow age pensioners to contribute proceeds from the sale of their primary residence, exempt from the assets test and income deeming rate, and able to be drawn upon to fund living expenses and care costs;

-

Establishment of an Australian Government backed equity release scheme to assist older Australians to meet their aged care costs whilst retaining their primary residence; and

-

Increased subsidy for approved basic standard of residential care accommodation.

As a leader in your organisation, you are responsible for guiding the organisation through this change process.

LCC, Afternoon Session, Scenario

(Note that this is similar, though not identical, to the second BCS scenario.)

It is 1 July 2012.

Following an extensive investigation of options for aged care reform and the development of a new industry blue-print by the Productivity Commission, the minority Federal Government developed legislation to enact the key components of the Commission’s findings.

Regrettably, the legislation did not pass the House of Representatives when it went to the vote in June because the opposition and some independents voted against it. Several issues key to the reform package had become divided along party lines including:

-

The plan to abolish bed licences in residential aged care after 2017 and the opening of the market to competition from any eligible provider

-

The need for aged care recipients to contribute more to the cost of their care and accommodation (except supported residents).

-

The abolition of accommodation bonds and their replacement by periodic payments.

-

The reverse mortgage proposal was labelling “A great big new death tax”.

Due to the failure of these reforms, the existing weaknesses of the aged care system will only get worse:

-

It is increasingly uneconomic to build new high care beds or to replace or upgrade ageing buildings used for high care—services already lose more than $18 per day on average for every high care bed they have (with the exception of ‘extra services’ beds).

-

Government funding has not kept up with increases in costs, especially labour and energy costs, for many years and more than 70 % of services nationally are now operating in deficit.

-

The demand for low care has been dropping because of the increased availability of in-the-home support. Not only are vacancy rates increasing but the amount held in accommodation bonds is reducing fairly rapidly.

Incidentally, a medium sized for-profit aged care provider in Victoria has recently appointed administrators because of trading difficulties. The administrators have declared the services to be unviable and are now seeking to sell the assets which include some services on valuable inner-city land.

You are part of the executive management team of a medium sized faith-based aged care provider in Queensland. How will you respond to the circumstances in which the industry now finds itself?

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sankaran, S., Dick, B., Shaw, K. et al. Application of Scenario-based Approaches in Leadership Research: An Action Research Intervention as Three Sets of Interlinked Practices. Syst Pract Action Res 27, 551–573 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11213-013-9308-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11213-013-9308-6