Abstract

School attacks against children seriously threaten the belief that the world is a just place, in which good people get rewarded and bad people get punished. However, to what extent and in which way belief in a just world (BJW) plays a role in reaction to school attacks have not been investigated, especially in the Chinese context, in which people are traditionally expected to prize harmony over justice. Two studies examined how Chinese people varying in BJW differ in supporting punishment for the perpetrators of school attacks in China in 2010. In Study 1, general BJW among Chinese adults predicted support for perpetrator punishment, and those who paid more attention to the crime news also reported a higher level of punishment support. Study 2 revealed a similar pattern among Chinese adolescents, whose previously measured higher general BJW predicted increasing support for perpetrator punishment, and this effect was mediated via personal distress. In summary, general just-world belief facilitates punishment support among parents and adolescents in the Chinese context.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Attacks in school settings are some of the most tragic targeted crimes to occur over past decades (Towers, Gomez-Lievano, Khan, Mubayi, & Castillo-Chavez, 2015; Vossekuil, Fein, Reddy, Rorum, & Modzeleski, 2004). In recent years, such tragedies are becoming more prevalent in developing countries, like in China, which is experiencing rapid industrialization and social tensions (Chen & Li, 2016). Since 2010, a spate of fatal attacks on kindergartens or elementary schools, with dozens of people (mostly children) dead and more than one hundred injured, shocked the country and produced a tremendous effect on the public.Footnote 1

Here we argue that justice concerns play a critical role in people’s reactions to school attacks, because such crimes, with children killed or injured, might seriously threaten individuals’ justice beliefs, by providing evidence that the world is not a just place at all. Individuals are motivated to believe in a just world (BJW), in which good people get rewarded and bad people get punished, so encountering evidence that the world is not just can be deeply disturbing (Lerner & Miller, 1978). Thus far, research on strategies for coping with threats to BJW has focused on non-rational reactions to the actor (i.e., perpetrator) of injustice or the recipient (i.e., victim) of injustice and, on occasion, rational compensation for victims. Compared to victim blaming and compensation, however, support for perpetrator punishment draws less moral criticism and recruits less efforts or resources (Hafer & Gosse, 2010; Gerbasi, Zuckerman, & Reis, 1977). Taking school attacks as an example, it is quite unlikely that people react by victim blaming, rather than perpetrator punishment. Nonetheless, just-world believers could view the attacks as less severe and blame the victims (or parents and teachers of the victims) for their carelessness. However, to date there are few empirical studies to examine the effect of BJW on support for perpetrator punishment in reaction to school attacks, especially in the Chinese context.

Justice Motive and Culture

Almost all BJW research is set in a Western context, and it is still unclear how BJW is related to psychological outcomes in other cultures. BJW might matter less among Chinese, because China is traditionally regarded as a collectivist culture in which individuals may be more harmony-focused but less sensitive to justice (Triandis, McCusker, & Hui, 1990). Even so, we do believe that justice concerns matter in China because of the ways that BJW reflects a basic human need to understand and predict one’s world, in both the East and West (Lucas et al., 2015). For example, Chinese have been found to hold a strong BJW, which is consistent with their human-centered cultural traditions that dictate that people should make great efforts and careful planning to confront environmental difficulties and thereby expect to succeed in the world (Cohen, Wu, & Miller, 2016; Wu et al., 2011; for a cross-cultural comparison see: Furnham, 1985, 1993). A recent meta-analysis of BJW in Chinese, covering 36 samples (n = 8396), showed that general just-world belief was prevalent among adolescents, college students, and professional groups, especially among those who have experienced adversities such as natural disasters or economic disadvantages (Wu et al., 2016).

Focusing on support for perpetrator punishment in reaction to school attacks, however, it is still arguable whether the well-established relationship between BJW and punishment is culturally universal (for a review, see: Hafer & Gosse, 2010). This is an intriguing question because recent findings have demonstrated the adaptive and pro-social functions of general BJW among Chinese. For example, Chinese participants with greater general just-world belief reported a higher level of life satisfaction and resilience (Wu et al., 2011, 2013), but a lower intention to aggression following ostracism (Poon & Chen, 2014). However, the same relationship was not found among North Americans (Bègue & Bastounis, 2003; Kaiser, Vick, & Major, 2004) or Western Europeans (Lucas, Young, Zhdanova, & Alexander, 2010; Strelan & Sutton, 2011). That is, previous research suggests a contradiction. On the one hand, pro-social reactions to threatened BJW suggest that Chinese participants might be less punitive. On the other hand, there is still reason to expect that Chinese participants, as members of a collectivist culture, might tend to be punitive and unforgiving (Gollwitzer & Bücklein, 2007). This could occur because the relationship between BJW and punishment is well documented (Hafer & Gosse, 2010). This could also occur because the extraordinary emphasis on achievement and efforts (concepts related to BJW) in Confucianism leads to higher scores on toughness, maliciousness, and punishing inclinations following negative events among Chinese, as compared to North Americans (Stankov, 2010). This suggests the possibility of adaptive functions of general BJW among Chinese, but also raises a question of whether the well-established justice-punishment model could be extended to the Chinese context.

In sum, justice may be a fundamental motive in human lives and may lead to harsh attitudes under conditions where justice seems threatened, but there is no or very little empirical evidence to help establish the connection between justice beliefs and punishment in the Chinese context, in which general BJW may serve adaptive and even pro-social functions. So, it is worthwhile to examine individual differences in BJW and its relationship to support for perpetrator punishment among Chinese participants.

Individual Differences in Just-World Beliefs and Punishment

Not all individuals have the same level or type of justice motive, even within the same culture. As previous research suggests, humans vary considerably in their endorsement of BJW and its function (Rubin & Peplau, 1975; Schmitt, 1998). In particular, general BJW (referring to the belief that others are treated fairly) is related to harsh social attitudes such as victim blaming and revenge, because BJW for others leads to justification of the suffering of others and retribution of justice; in contrast, personal BJW (referring to the belief that oneself is treated fairly) is related to subjective well-being and pro-social behaviors, because BJW for oneself enables the individual to pursue life goals and self-regulation (Strelan & Sutton, 2011; Sutton & Douglas, 2005; Sutton & Winnard, 2007). Individuals with high general BJW tend to favor punishment, such as penalty toward delinquents, whereas those with high personal BJW tend to forgive (Bègue & Bastounis, 2003; Lucas et al., 2010; Strelan & Sutton, 2011).

Following the above theories and studies, our current aim is to explore the extent to which justice motives, especially general BJW, relate to how people endorse punishment for perpetrators of school attacks. There are two reasons that individuals with stronger general beliefs in a just world might be expected to show higher tendency to support punishment: (a) general just-world believers believe that they live in a just place, which is threatened by unjust events; and (b) they tend to favor justice restoring or retributive outcomes of injustice, and the main strategy is to punish the perpetrators who violate justice norms. A vast body of literature has demonstrated the effect of individual differences in general BJW on punitive, or anti-defendant, attitudes in matters of criminal justice (Darley, 2002; Mohr & Luscri, 1995; for a review, see: Hafer & Gosse, 2010). In a recent study conducted in the Chinese context, where family harmony is extremely valued, stronger BJW was also found to lead to higher punitive attitudes toward corruption committed by either families or peers (Bai, Liu, & Kou, 2014). In the case of violent crimes, individuals with stronger general BJW were found to be more likely to render guilty verdicts in trials of battered women who killed their abusers (Schuller, Smith, & Olson, 1994) and to exhibit a stronger desire for revenge after the September 11 attacks, even among those that were thousands of miles away from Ground Zero (Kaiser et al., 2004). However, there is no evidence regarding whether general BJW predicts support for perpetrator punishment after school attacks, suggesting more work in this area is needed.

The Present Research

The main research question of the present project is how individual differences in justice beliefs relate to support for perpetrator punishment in reaction to school attacks. We chose to examine this phenomenon among Chinese because, as a cultural group, they consistently display a robust tendency to endorse general BJW but the effect of their general BJW on harsh attitudes remains unclear (Wu et al., 2011, 2013).

Next we consider a possible mediator of effects of BJW on punishment. It has been well established that BJW is threatened by a crime, which could result in distress. Distress could then influence the endorsement of retribution, because viewing crime news offers evidence that the world is not stable or orderly (Lerner, 1980). For example, distress about attacks and victimization was found to serve as common emotional responses to justice threats, especially among just-world believers, resulting in a higher tendency for revenge (Kaiser et al., 2004; McCullough, Bellah, Kilpatrick, & Johnson, 2001).

Two studies examined the link between justice beliefs and perpetrator punishment, among Chinese adults and adolescents who were exposed to targeted crime news about school attacks. The first study examined the relationship between general BJW and perpetrator punishment, and then the second study tested if psychological distress played a mediation role in this justice-punishment model. We hypothesized that general BJW would motivate the Chinese adults (Study 1) and adolescents (Study 2) via psychological distress to favor the endorsement of punishment.

Study 1

The first study was based on series of school attacks in 2010. Although the state media released few facts on the incident and even deleted forum entries on the internet for fear of copycat crimes and mass panic, some news agencies worked with education departments and research institutions, making parents and children aware and training them to manage the threats and to prevent future attacks.Footnote 2 The research was conducted along with the distribution of a newspaper, namely Chinese Students’ Health—Pupils Weekly that was mainly for the parents of elementary school students in China.

We exposed the parents to the crime news about the school attacks and investigated their BJW and support for perpetrator punishment. We also took into consideration victim blaming and examined whether there were BJW effects on victim blaming as well as perpetrator punishment. BJW was considered with two levels: general BJW (referring to the belief that others are treated fairly), which previously has been related to harsh attitudes such justifying the suffering of others, and personal BJW (referring to the belief that oneself is treated fairly), which previously has been related to subjective well-being and forgiveness (Strelan & Sutton, 2011; Sutton & Douglas, 2005). Our hypotheses were that:

H1

The stronger general BJW the adult participants have, the more they will endorse perpetrator punishment in response to school attacks; but there will be no significant relationship of personal BJW with perpetrator punishment.

H2

Although general BJW was related to victim blaming in some previous findings, we hypothesized that a similar pattern would not be evident in the present study, because of the severe nature of the school attacks in which many children were killed.

Participants

Two hundred and forty-three parents were recruited in elementary schools during the distribution of Chinese Students’ Health—Pupils Weekly. Seven of them failed to complete the study, resulting in 236 valid cases (140 females, 59.3%; 90 males, 38.1%; 6 missing, 2.6%), whose ages ranged from 30 to 59 years (M = 37.86, SD = 3.85). Among them, 52 reported an elementary level of education (22.0%), 71 secondary education (30.1%), 103 college or higher (43.6%), and 10 did not provide this information (4.2%). In addition, 145 of the participants (61.4%) were from Beijing (“no hit area,” in which there was no school attacks in 2010) and 92 (38.6%) from Shandong (“hit area,” in which there was a school attack in 2010 in which five children were attacked just half a month before the survey was conducted).

Materials and Procedure

The study included three sections: (1) participants completed BJW scales, then (2) they were asked to read crime news about school attacks, and lastly (3) they filled out a questionnaire regarding support for perpetrator punishment and victim blaming.

General BJW was measured with the validated Chinese version (Wu et al., 2011) of Dalbert’s (1999) 6 items for general BJW (e.g., “I believe that, by and large, people get what they deserve”; α = .78) and 7 items for personal BJW (e.g., “I believe that I usually get what I deserve”; α = .77). Participants responded from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree), and higher scores meant stronger just-world beliefs.

Exposure to Crime News

Crime news including six brief stories (about 400 words totally) related to series of school attacks (e.g., a man attacked young kids of elementary schools and kindergartens) were presented in the Chinese Students’ Health—Pupils Weekly. Participants were asked to read the crime news and then to participate in an attention check task, by answering one question: “how many school attacks happened in elementary schools?” There were four elementary schools and two kindergartens in the present news stories. In China, elementary school is part of the 9-year compulsory education system (state owned and funded), while kindergarten is part of the preschool education system (usually privately run). It should be easy for the participants (pupils’ parents) to notice the difference in the number of kindergartens and elementary schools when reading the news stories. If the participants did not read all the news stories carefully or even skipped this section entirely, however, they could think all the events happened in elementary schools and then give a wrong number of elementary schools. Therefore, the right answer (“four”) was used to identify whether the participant was attending to these news stories, and the 50 participants who failed were identified as not really paying attention to the crime news.

Dependent Measures

The participants were asked how much they endorsed three statements about perpetrator punishment (e.g., “the perpetrators should be sentenced to death”; “the perpetrators should be punished as soon as possible”; “We must strongly condemn the perpetrators without any concerns”). The participants responded from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely). With an acceptable reliability (α = .65), we aggregated the three items to get a general index of perpetrator punishment. This reliability was relatively low, possibly because the participants’ education ranged from elementary to college levels. There were also two statements which blamed victims for their carelessness and wrongdoing, such as “the parents behaved carelessly and lacked awareness of how to protect their children” and “the parents (including the local officers) offended the killer before (so the killer selectively attacked the school that their offspring studied in).” The reliability of victim blaming items was very low (α = .44), perhaps because most of the victims had no specific relationship with the perpetrators in the six school attacks and the wrongdoing item made the participants confused. Therefore, only the carelessness item was included in the following analysis.

Participants were also asked to answer several demographic questions, including their birth year, sex, and education level. The study was completed in the classroom or at participants’ home. A consent form was obtained for the participants, and a gift was offered as reward (e.g., 4 issues of Pupils Weekly). The participants were debriefed after all the tasks were completed. For example, we told them that the school attacks (presented in the crime news) happened far away from their campus, and the murderer was arrested. They were also reassured that both public and campus security systems were nationally consolidated recently, and the campus was safe right now. This helped release any distress people may have felt when exposed to school attacks. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Institute of Psychology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (No. H10007).

Results

As shown in Table 1, support for perpetrator punishment was found to significantly correlate with general BJW, but not with personal BJW. Victim blaming was not significantly related to general BJW or personal BJW. In addition, there was no significant difference in general or personal BJW among those paying or not paying attention to the crime news (coded as 1 = yes, 0 = no). However, those paying attention to the crime news and those with a higher level of education reported greater perpetrator punishment, and those living in Beijing (coded as 0 = Beijing/no hit area, 1 = Shandong/hit area) reported greater victim blaming. Given that education, region, and attention played a considerable role in response to school attacks, all demographic variables as well as the attention check and victim blaming were included in the multivariate regression analysis. On support for perpetrator punishment, only attention revealed a significant prediction effect, whereas age, sex, education, region, and victim blaming did not.

Next, through hierarchical regression models, we examined the effect of general BJW on support for perpetrator punishment by controlling for the above confounding factors in the first model. Because those who paid more attention to the crime stories endorsed stronger punishment, it is important to test whether the relationship between general BJW and perpetrator punishment depends upon whether participants read the crime stories closely. Therefore, we included the interaction between the attention check and general BJW in the regression equation. On perpetrator punishment, as shown in Table 2, the effect of general (but not personal) BJW remained significant, while the effect of all the other variables and the interaction between general BJW and attention were not significant. Similarly, we also examined the interaction effect between personal BJW and attention on perpetrator punishment, with personal and general BJW and other demographic variables included. The effect of general (but not personal) BJW was significant (β = .19, t = 2.30, p < .05), while the effect of all the other variables and the interaction between personal BJW and attention (β = −.48, t = −1.41, p = .16) was not significant.

Discussion

Supporting the hypotheses, the present findings are consistent with prior findings, in which general BJW but not personal BJW predicts harsh attitudes toward individuals (Strelan & Sutton, 2011; Sutton & Douglas, 2005). Furthermore, the effect of general BJW on support for perpetrator punishment remained significant, after controlling for the age, sex, education, region, and attention paid to the crime news. Nonetheless, general BJW failed to predict victim blaming, possibly because the victims in school attacks were children (who were too vulnerable to be blamed). Therefore, we chose to focus on general BJW and perpetrator punishment in the second study.

In addition, those who paid attention to the crime news reported a higher tendency for perpetrator punishment, although this effect was not significant when general BJW and the general BJW× attention interaction term were entered in the model and the interaction effect between general BJW (or personal BJW) and attention on perpetrator punishment was not significant. This study was conducted after the five school attacks happened, and almost all the participants (elementary students’ parents) had gotten some information about school attacks (though maybe not details) in campus safety education programs. That is, the participants may have known about the school attacks mentioned in the research materials, although some of them were identified as not paying attention to the crime news (as shown in the present study). The absence of a statistically significant interaction between general BJW and attention indicates that the relationship between general BJW and punishment support was not shaped by how closely participants read the crime stories. Furthermore, we found that attention (to the crime news) was positively related to education level and to perpetrator punishment, suggesting that those who failed the attention check might underestimate the severity of the tragedies because of their lower literacy. In sum, attention played a considerable role in reactions to the school attacks, and the relationship between general BJW and punishment was similar for those who paid attention and those who did not. Therefore, those failing attention check should not be excluded from data analysis, but responses to the attention check item needed to be taken into account theoretically and analytically.

Study 2

The second study employed adolescent participants to replicate the relationship of general BJW to punishment as found in Study 1. General BJW is sometimes seen as more important in adolescence than in adulthood, because adolescents have not developed a sophisticated world view and a just world protects them from the dampening of future confidence and life stability (Callan, Harvey, Dawtry, & Sutton, 2013; Oppenheimer, 2006; Sutton & Winnard, 2007; Wu et al., 2013). Another reason why we chose adolescents as our target participants was that they were often the direct victims in school attacks (as in Study 1), so that the education departments launched prevention and awareness programs about campus safety education to train students and employees to evaluate and respond to target crimes properly (taking the US Department of Education as a sample, see: http://www2.ed.gov/admins/lead/safety/campus.html).

By using a similar paradigm as in Study 1, the second study examined the relationship of Chinese adolescents’ support for perpetrator punishment to their previously measured general BJW. Hoping to substantiate a possible mediator between justice beliefs and punishment, we further take into consideration participants’ distress. However, distress could be derived from two different processes (Eisenberg et al., 1989). One is individuals’ empathy or sympathy (e.g., the tendency to feel concerned or sorry for needy others), and another is personal distress (feeling scared or anxious in the face of others’ suffering), both of which could work in encountering injustice and endorsing retributions. While empathy leads to moral reactions on behalf of victims, such as punishment for perpetrators (Raney, 2005; Zillmann, 1995), personal distress is more related to self-focused and less benign attitudes (Eisenberg, 2010). When observing others’ suffering, for example, higher empathizers show a lower threshold for incidents of injustice, experience stronger outrage, and have more motives to reestablish justice on behalf of victims (Schmitt et al., 2005). In the case of personal distress, participants more frequently exposed to crime were found to report a higher level of fear, and fear of crime was positively related to punitive attitudes and negatively to estimations of police effectiveness, while supporting the death penalty and stiffer sentences but opposing parole (Dowler, 2003).

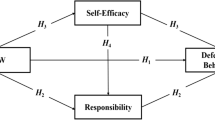

H3

BJW would predict greater support for perpetrator punishment in response to school attacks.

H4

Personal distress would mediate the effect of general BJW on support for perpetrator punishment.

H5

Similarly, empathy would mediate the effect of general BJW on support for perpetrator punishment.

Participants

One hundred and thirty-four Chinese adolescents were recruited during a psychological program about campus safety education in Beijing (69 females, 51.5%; 65 males, 48.5%), with ages ranging from 12 to 14 (M = 13.24, SD = .46).

Materials and Procedure

The second study consisted of three sessions: (1) participants completed BJW and empathy scales, then, (2) eight months later they were exposed to crime news, and lastly (3) they were asked to fill out a questionnaire about personal distress and support for perpetrator punishment.

The same scale of general BJW (α = .79) was used as in Study 1. Additionally, a Chinese version of the empathy scale (Chen, 2007, see also: Davis, 1983) was administered with 22 items (e.g., “I often have tender, concerned feelings for people less fortunate than me,” 0 = does not describe me well, 4 = describes me very well). The scale displayed good reliability (α = .86), and higher scores reflected higher levels of empathy.

Exposure to Crime News

Participants were asked to read crime news including five stories about school attacks (similar to those in Study 1). Then, they took part in an attention check, by answering two questions which helped identify whether they were paying close attention to the news stories: (a) how many school attacks happened recently; (b) how many children died in these school attacks. There were five school attacks, in which nine kids and two adults died. Therefore, the right answers (“five” school attacks and “nine” children dead) were used to identify whether the participants paid attention to the crime news, and as described above, 29 of them failed the attention check. Considering the possible role of attention as in Study 1, the attention variable was coded (1 = yes, 0 = no) and was included in the following analyses.

Dependent Measures

Three items were used to measure personal distress (“I felt very apprehensive when thinking about these tragedies”; “the school attacks scared me”; “I felt threatened after these school attacks happened”; α = .68), and then participants were asked how much they favored the three punitive statements (α = .81) as in Study 1. Responses ranged from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely), and the aggregation of the relevant items led to the indexes of personal distress and perpetrator punishment, respectively.

Also, participants were asked to answer several demographic questions, including their birth year and biological sex. The study was completed in the classroom. The consent form was obtained from the participants and their guardians, and a gift was offered as reward (4 issues of Middle School Students Weekly). The participants were debriefed after all the tasks were completed as in Study 1. In addition, we had a professional consultant to work together with us and answer whatever questions the adolescent participants raised, and made sure each participant felt relaxed at the end. This protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Institute of Psychology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (No. H10007).

Results and Discussion

As shown in Table 3, correlational analysis revealed that among the Chinese adolescents, general BJW (measured 8 months prior) correlated with empathy, and with perpetrator punishment and personal distress when exposed to the crime news about school attacks. In addition, support for perpetrator punishment was related to personal distress, but not to empathy, age, or sex (0 = male, 1 = female). Furthermore, there was no significant difference in general BJW, support for perpetrator punishment, personal distress, empathy, age, or sex, among those paying or not paying attention to the crime news (1 = yes, 0 = no).

Next, we tested via the mediation model (Hayes, 2013) in which personal distress or empathy could explain the effect of general BJW on perpetrator punishment. We regarded general BJW as the independent variable, punishment as the dependent variable, personal distress as the potential mediator, and sex, age, attention, and empathy as covariates. The results revealed that general BJW was significantly related to personal distress (B = .22, SE = .09, p < .05) and that personal distress (B = .35, SE = .10, p < .01) was significantly related to punishment support. Further, general BJW revealed a significant total effect (B = .30, SE = .10, p < .01) and a significant direct effect (B = .22, SE = .09, p < .05) on punishment support. As shown in Fig. 1, we found a significant indirect effect of general BJW on punishment support, B = .08, SE = .05, 95% CI [.01, .20]. Since this confidence interval excluded zero, this result supported our claim that the relationship between general BJW and punishment was significantly mediated by personal distress. We ran a similar model in which we regarded general BJW as the independent variable, punishment as the dependent variable, empathy as the potential mediator, and sex, age, attention, and personal distress as covariates. The results revealed no significant indirect effect of general BJW on punishment support via empathy, B = .01, SE = .02, 95% CI [−.03, .06], which did not support our hypothesis that the relationship between general BJW and punishment was significantly mediated by empathy.Footnote 3

Consistent with hypothesis H3, these results replicated the finding in Study 1, in which general BJW predicted the support for perpetrator punishment in school attacks. However, there was no significant difference in perpetrator punishment and personal distress among those who paid or not to the crime news, possibly because those who did not pay attention to the crime news had already learned the information about school attacks in the psychological program about campus safety education. Further, personal distress (not empathy) mediated the prediction of general BJW to support for perpetrator punishment, while controlling for age, sex, attention paid to the crime news, and empathy. Hypothesis H4, but not H5, was supported.

General Discussion

The present research examined the effect of general BJW on support for perpetrator punishment, among Chinese participants exposed to crime news about school attacks. Consistent with previous theorizing about justice motive and culture, the current results demonstrate a correlation of general BJW with punishment support in response to school attacks among Chinese parents (Study 1), and the relation of the previously measured general BJW (eight months prior) on punishment support among Chinese adolescents (Study 2). Focusing on school attacks, Study 1 found that justice motives, specifically general (not personal) BJW, correlated with support for perpetrator punishment but not with victim blaming, and Study 2 replicated this effect and found that personal distress (not empathy) mediated the effect of justice beliefs on perpetrator punishment.

The findings about general BJW and punishment support extend what is known about the effect of justice motives on punitive attitudes. This is consistent with the well-established theory that perpetrator punishment is one of the main strategies to cope with justice-related threats (Hafer & Gosse, 2010), which in this case we applied to the context of school attacks in China. By considering BJW as a fundamental motive in human lives (Lerner & Miller, 1978), the present research not only helps examine whether or not social justice notions could contribute to perpetrator punishment in reactions to targeted crimes, but also provides evidence for an affective mechanism about how justice notions facilitate support for perpetrator punishment, via personal distress (Zillmann, Taylor, & Lewis, 1998). Empathy was not significantly related to perpetrator punishment, possibly because empathy is actually multifaceted, including concerned feelings and personal distress in face of others’ sufferings (Davis, 1983). It is concerned feelings, but not personal distress, that seems to lead to other-focus and pro-social behaviors, and personal distress, but not concerned feelings, that may lead to self-focus and retribution (Eisenberg et al., 1989). Personal distress more likely mediated the relationship between general BJW and punishment in response to school attacks, also because the nature of such crime (e.g., random targets) recruited personal distress and uncertainty, rather than concerned feelings.

Furthermore, this justice-punishment relation, shown among Chinese, helps clarify that retributive justice may be culturally universal under justice-threatening conditions. While above we questioned whether justice concerns would be salient in a collectivist culture, there might even be reason to think such a relation might be more powerful in collectivist cultural contexts (Gollwitzer & Bücklein, 2007). General BJW does appear to be adaptive and serve pro-social functions in Chinese culture (Poon & Chen, 2014; Wu et al., 2011, 2013, 2016).

There are still two issues worthy of further examination. First, the robust general BJW and support for perpetrator punishment among Chinese may be deeply influenced by their cultural heritage. According to Confucians’ moral principles, injury should be returned for injury so that the people are warned to refrain from wrongdoing, just as kindness should be returned for kindness so that people are stimulated to be kind (see Li Ji or The Classic of Rites, translated by James Legge). That is, Chinese have been taught over centuries to be punitive toward moral deviators by acting for retributive justice (zhi). It is quite possible that the current Chinese participants who support punishment principle are doing so to sustain social harmony in a Confucian way within a large and populous society. The dynamics could be different in small communities in which there are numerous reputational and educational mechanisms to achieve the same outcomes, other than through the individuals’ just-world beliefs (Henrich et al., 2010; Wenzel & Thielmann, 2006). Therefore, an important question for future research is to test whether endorsement of Confucianism moderates the link between BJW and punishment support. We would expect that stronger endorsement of Confucianism would predict a larger link between BJW and favoring punishment, among Chinese.

Second, the connection of general BJW with support for perpetrator punishment can be accounted for in part by the overlap between BJW and political ideologies such as right-wing authoritarianism (Connors & Heaven, 1987; Lambert, Burroughs, & Nguyen, 1999). However, some researchers have documented that the justice-punishment link is still robust when controlling for right-wing ideology (Bègue & Bastounis, 2003). Another possibility is that support for perpetrator punishment among Chinese is not only an instantiation of BJW (Lerner, 2003; Lerner, Goldberg, & Tetlock, 1998), but also a deliberate impression management strategy, which is sensible given that Chinese people live in a tight and hierarchical society (Gelfand et al., 2011). In future directions, therefore, the roles of authoritarianism, cultural tightness, social distance, and impression management should be considered (Benabou & Tirole, 2006; Kaiser et al., 2004; Wang, Xia, Meloni, Zhou, & Moreno, 2013).

Taken together, general just-world belief, which serves as a fundamental motive and is prevalent in the Confucian-influenced China, facilitates punishment support in response to targeted school attacks. Furthermore, considering that numerous features of justice and culture can be manipulated, future research should continue to investigate the causes and consequences of justice beliefs in different contexts, as we have begun to do in this paper.

Notes

For more information about school attacks in China, see the BBC news, 'Social tensions' behind China school attacks, see: http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/asia–pacific/8681873.stm.

As research consultants of these news agencies, we were invited to evaluate parents’ and children’ psychological outcomes in response to such crime news.

Given that empathy was not significantly correlated with perpetrator punishment (as shown in Table 3), the model regarding personal distress as the potential mediator of the relationship between empathy and punishment support was not considered.

References

Bai, B., Liu, X., & Kou, Y. (2014). Belief in a just world lowers perceived intention of corruption: The mediating role of perceived punishment. PLoS ONE, 9, e97075.

Bègue, L., & Bastounis, M. (2003). Two spheres of belief in justice: Extensive support for the bidimensional model of belief in a just world. Journal of Personality, 71, 435–463.

Benabou, R., & Tirole, J. (2006). Belief in a just world and redistributive politics. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 121, 699–746.

Callan, M. J., Harvey, A. J., Dawtry, R. J., & Sutton, R. M. (2013). Through the looking glass: Focusing on long-term goals increases immanent justice reasoning. British Journal of Social Psychology, 52, 377–385.

Chen, J. (2007). The relationship among empathy, its arousal mechanisms, and empathic outcomes. Beijing: Institute of Psychology, Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Chen, T., & Li, Y. (2016). Campus security: Situations, crux, and policy. Educational Research and Experiment, 35, 15–20. (in Chinese).

Cohen, A. B., Wu, M. S., & Miller, J. (2016). Religion and culture: Individualism and collectivism in the east and west. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 47, 1236–1249.

Connors, J., & Heaven, P. C. (1987). Authoritarianism and just world beliefs. The Journal of Social Psychology, 127, 345–346.

Dalbert, C. (1999). The world is more just for me than generally: About the personal belief in a just world scale’s validity. Social Justice Research, 12, 79–98.

Darley, J. M. (2002). Just punishments: Research on retributional justice. In M. Ross & D. T. Miller (Eds.), The justice motive in everyday life (pp. 314–333). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Davis, M. H. (1983). Measuring individual-differences in empathy: Evidence for a multidimensional approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 44, 113–126.

Dowler, K. (2003). Media consumption and public attitudes toward crime and justice: The relationship between fear of crime, punitive attitudes, and perceived police effectiveness. Journal of Criminal Justice and Popular Culture, 10, 109–126.

Eisenberg, N. (2010). Emotion, regulation, and moral development. Annual Review of Psychology, 51, 655–697.

Eisenberg, N., Fabes, R. A., Miller, P. A., Fultz, J., Mathy, R. M., Shell, R., et al. (1989). The relations of sympathy and personal distress to prosocial behavior: A multimethod study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 5, 55–66.

Furnham, A. (1985). Just world beliefs in an unjust society: A cross cultural comparison. European Journal of Social Psychology 15, 363–366.

Furnham, A. (1993). Just world beliefs in twelve societies. The Journal of Social Psychology, 133, 317–329.

Gelfand, M. J., Raver, J. L., Nishii, L., Leslie, L. M., Lun, J., Lim, B. C., et al. (2011). Differences between tight and loose cultures: A 33-nation study. Science, 332, 1100–1104.

Gerbasi, K. C., Zuckerman, M., & Reis, H. T. (1977). Justice needs a new blindfold: A review of mock jury research. Psychological Bulletin, 84, 323–345.

Gollwitzer, M., & Bücklein, K. (2007). Are “we” more punitive than “me”? Self-construal styles, justice-related attitudes, and punitive judgments. Social Justice Research, 20, 457–478.

Hafer, C. L., & Gosse, L. (2010). Preserving the belief in a just world: When and for whom are different strategies preferred? In D. R. Bobocel, A. C. Kay, M. P. Zanna, & J. M. Olson (Eds.), The psychology of justice and legitimacy: The Ontario symposium (Vol. 11, pp. 79–102). New York: Psychology Press.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York: Guilford Press.

Henrich, J., Ensminger, J., McElreath, R., Barr, A., Barrett, C., Bolyanatz, A., et al. (2010). Markets, religion, community size, and the evolution of fairness and punishment. Science, 327, 1480–1484.

Kaiser, C., Vick, S., & Major, B. (2004). A prospective investigation of the relationship between just-world beliefs and the desire for revenge after September 11, 2001. Psychological Science, 15, 503–506.

Lambert, A., Burroughs, T., & Nguyen, T. (1999). Perceptions of risk and the buffering hypothesis: The role of just world beliefs and right-wing authoritarianism. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 25, 643–656.

Lerner, M. (1980). The belief in a just world: A fundamental delusion. New York: Plenum Press.

Lerner, M. J. (2003). The justice motive: Where social psychologists found it, how they lost it, and why they may not find it again. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 7, 388–399.

Lerner, J. S., Goldberg, J., & Tetlock, P. (1998). Sober second thoughts: The effects of accountability, anger, and authoritarianism on attributions of responsibility. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 24, 563–574.

Lerner, M., & Miller, D. (1978). Just world research and the attribution process: Looking back and ahead. Psychological Bulletin, 85, 1030–1051.

Lucas, T., Kamble, S. V., Wu, M. S., Zhdanova, L., & Wendorf, C. A. (2015). Distributive and procedural justice for self and others: Measurement invariance and links to life satisfaction in four cultures. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 47, 234–248.

Lucas, T., Young, J. D., Zhdanova, L., & Alexander, S. (2010). Self and other justice beliefs, impulsivity, rumination, and forgiveness: Justice beliefs can both prevent and promote forgiveness. Personality and Individual Differences, 49, 851–856.

McCullough, M. E., Bellah, C. G., Kilpatrick, S. D., & Johnson, J. L. (2001). Vengefulness: Relationships with forgiveness, rumination, well-being, and the Big Five. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27, 601–610.

Mohr, P. B., & Luscri, G. (1995). Blame and punishment: Attitudes to juvenile and criminal offending. Psychological Reports, 77, 1091–1096.

Oppenheimer, L. (2006). The belief in a just world and subjective perceptions of society: A developmental perspective. Journal of Adolescence, 29, 655–669.

Poon, K.-T., & Chen, Z. (2014). When justice surrenders: The effect of just-world beliefs on aggression following ostracism. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 52, 101–112.

Raney, A. A. (2005). Punishing media criminals and moral judgment: The impact on enjoyment. Media Psychology, 7, 145–163.

Rubin, Z., & Peplau, L. A. (1975). Who believes in a just world? Journal of Social Issues, 31, 65–89.

Schmitt, M. J. (1998). Methodological strategies in research to validate measures of belief in a just world. In L. Montada & M. J. Lerner (Eds.), Responses to victimizations and belief in a just world (pp. 187–216). New York: Plenum.

Schmitt, M., Gollwitzer, M., Maes, J., & Arbach, D. (2005). Justice sensitivity: Assessment and location in the personality space. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 21, 202–211.

Schuller, R. A., Smith, V. L., & Olson, J. M. (1994). Juror’s decisions in trial of battered women who kill: The role of prior beliefs and expert testimony. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 24, 316–337.

Stankov, L. (2010). Unforgiving Confucian culture: A breeding ground for high academic achievement, test anxiety and self-doubt? Learning and Individual Differences, 20, 555–563.

Strelan, P., & Sutton, R. M. (2011). When just-world beliefs promote and when they inhibit forgiveness. Personality and Individual Differences, 50, 163–168.

Sutton, R., & Douglas, K. (2005). Justice for all, or just for me? More evidence of the importance of the self-other distinction in just-world beliefs. Personality and Individual Differences, 39, 637–645.

Sutton, R., & Winnard, E. (2007). Looking ahead through lenses of justice: The relevance of just-world beliefs to intentions and confidence in the future. British Journal of Social Psychology, 46, 649–666.

Towers, S., Gomez-Lievano, A., Khan, M., Mubayi, A., & Castillo-Chavez, C. (2015). Contagion in mass killings and school shootings. PLoS ONE, 10, e0117259.

Triandis, H. C., McCusker, C., & Hui, C. H. (1990). Multimethod probes of individualism and collectivism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59, 1006–1020.

Vossekuil, B., Fein, R. A., Reddy, M., Rorum, R., & Modzeleski, W. (2004). The final report and findings of the safe school initiative: Implications for the prevention from school attacks in the United States. Washington, DC: United States Secret Service and United States Department of Education.

Wang, Z., Xia, C.-Y., Meloni, S., Zhou, C.-S., & Moreno, Y. (2013). Impact of social punishment on cooperative behavior in complex networks. Scientific Reports, 3, srep03055.

Wenzel, M., & Thielmann, I. (2006). Why we punish in the name of justice: Just desert versus value restoration and the role of social identity. Social Justice Research, 19, 450–470.

Wu, M. S., Pan, X., Wang, P., Li, H., & Nudelman, G. (2016). Research bias in justice motive: A meta-analysis of belief in a just world among Chinese (in Chinese). Chinese Social Psychology Review, 11, 162–178.

Wu, M. S., Sutton, R. M., Yan, X., Zhou, C., Chen, Y., Zhu, Z., et al. (2013). Time frame and justice motive: Future perspective moderates the adaptive function of general belief in a just world. PLoS ONE, 8, e80668.

Wu, M. S., Yan, X., Zhou, C., Chen, Y., Li, J., Shen, X., et al. (2011). General belief in a just world and resilience: Evidence from a collectivistic culture. European Journal of Personality, 25, 431–442.

Zillmann, D. (1995). Mechanisms of emotional involvement with drama. Poetics, 23, 33–51.

Zillmann, D., Taylor, K., & Lewis, K. (1998). News as nonfiction theater: How dispositions toward the public cast of characters affect reactions. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 42, 153–169.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to Drs. Christine Ma-Kellams, Qihao Ji, Juan Li, and David Wulff for their comments on the early drafts. We are thankful to Miss Xiangqin Shen, Miss Junyan Li, Miss Yanqing Ji, and volunteers for their help with data collection and coding.

Funding

The completion of this research was partially supported by a grant from Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities in China (No. 20720151116) and by a program for Innovative Research Team of Xiamen University (No. 20720171005).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wu, M.S., Cohen, A.B. Justice Concerns After School Attacks: Belief in a Just World and Support for Perpetrator Punishment Among Chinese Adults and Adolescents. Soc Just Res 30, 221–237 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-017-0286-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-017-0286-1