Abstract

Why is it that some people respond in a more negative way to procedural injustice than do others, and why is it that some people go on to defy authority while others in the same situation do not? Personality theorists suggest that the psychological effect of a situation depends on how a person interprets the situation and that such differences in interpretation can vary as a function of individual difference factors. For example, affect intensity—one’s predisposition to react more or less emotionally to an event—is one such individual difference factor that has been shown to influence people’s reactions to events. Cross-sectional survey data collected from (a) 652 tax offenders who have been through a serious law enforcement experience (Study 1), and (b) 672 citizens with recent personal contact with a police officer (Study 2), showed that individual differences in ‘affect intensity’ moderate the effect of procedural justice on both affective reactions and compliance behavior. Specifically, perceptions of procedural justice had a greater effect in reducing anger and reports of non-compliance among those lower in affect intensity than those higher in affect intensity. Both methodological and theoretical explanations are offered to explain the results, including the suggestion that emotions of shame may play a role in the observed interaction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A significant body of research has now been published, which shows that perceptions of procedural justice have a positive effect on people’s attitudes and behaviors. For example, people who feel an authority has treated them with dignity, respect, and fairness will be more likely to make positive evaluations about that authority (Sunshine & Tyler, 2003; Murphy, 2005), and will be more likely to comply with that authority’s rules and directives (Tyler, 2006; Tyler & Huo, 2002).

In recent years, procedural justice scholars have started to focus on people’s emotional reactions to perceived justice or injustice in an attempt to better understand reactions to unfairness (see De Cremer & Van den Bos, 2007). A handful of studies have shown that perceptions of procedural justice (or injustice) can lead people to experience the discrete emotions of happiness, joy, pride, guilt, disappointment, anger, frustration, and anxiety (e.g., Krehbiel & Cropanzano, 2000; Weiss, Suckow, & Cropanzano, 1999). An interesting issue that has only just begun to receive attention in the procedural justice literature is the degree to which individual differences in personality can influence reactions to procedural justice or injustice. For example, the emotion literature suggests that people can react more strongly or more mildly to affect-eliciting events (e.g., Diener, Larsen, Levine, & Emmons, 1985). This suggests that reactions to procedural unfairness or fairness may be moderated by the propensity to respond negatively or positively to such experiences. To date, however, only one research program has examined the role of individual differences in ‘affect intensity’ in people’s reactions to procedural fairness (Van den Bos, Maas, Waldring, & Semin, 2003). The aim of this study, therefore, was to extend research in this area.

Procedural Justice and Compliance

Procedural justice scholars have put much effort into trying to explain why people obey the law and comply voluntarily with an authority’s rules and decisions. Procedural justice concerns the perceived fairness of the procedures involved in decision making and the perceived treatment one receives from a decision maker. More specifically, relational models of procedural justice postulate that people’s motivation for compliance extends beyond their concern for favorable outcomes (Tyler, 1989; Lind & Tyler, 1988; Tyler & Lind, 1992). This view recognizes the importance of interpersonal treatment in determining whether people will obey the law (Tyler & Blader, 2003). For example, according to the group value model procedures are evaluated in terms of what they communicate about the relationship between the individual and the authority (Lind & Tyler, 1988; Tyler, 1989; Tyler & Lind, 1992). The model implies that people are in fact interested in the relational aspects of their social interactions and value their long-term relationships with authorities. Tyler and Lind (1992) propose that people will judge procedures as fair when they communicate feelings of self-worth, and indicate a positive, full-status relationship with that authority or institution. Relational aspects of experience include neutrality, lack of bias, honesty, efforts to be fair, politeness, and respect for citizens’ rights. According to Tyler (1990) all of these features of a procedure are conceptually distinct from its outcome, and therefore represent the values that may be used to define procedural fairness.

The positive influence of procedural justice on compliance behavior has been demonstrated across a variety of contexts. For instance, Bies, Martin, and Brockner (1993) examined the influence of procedural justice perceptions on organizational cooperation among layoff victims. They surveyed 147 skilled workers who had received notification of their impending layoff two months earlier, but who still had one month left before termination. Employees who felt they had been treated with respect and dignity (i.e., procedural justice) during the layoff process and felt the layoff process was fair, were more likely to engage in organizational citizenship behaviors up until their termination date. In other words, employees continued to cooperate and assist the organization to improve despite their future unemployment status.

Studies conducted in regulatory settings have also demonstrated that perceptions of procedural justice can lead to compliance with the law (Tyler, 2006; Wenzel, 2002a, b). For example, in an Australian study, Wenzel (2002a) found that procedural justice was important in predicting Australian taxpayers’ compliance behaviors. Utilizing survey data from 2,040 Australian citizens, Wenzel found that taxpayers were more likely to report being compliant when they felt the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) had treated them in a fair and respectful manner. Research conducted in the nursing home industry has also demonstrated that procedural justice judgements play an important role in shaping adherence to laws over time. Braithwaite and Makkai (1994) studied the influence that perceived poor treatment by authorities had on manager’s compliance behaviors by examining 410 nursing homes that were undergoing inspection. Each nursing home manager was awarded a compliance score at an initial inspection and again 18 months later during a follow-up inspection. Braithwaite and Makkai observed that if inspectors were seen to be treating managers with procedural justice (i.e., respectful and trustworthy treatment), nursing homes became more compliant in an assessment two years later. Findings from numerous other studies also demonstrate just how striking the effects of procedural justice are. Not only do they demonstrate that procedural justice is important for gaining long-term compliance behavior, but they also show that the influence of fair treatment extends across a wide variety of contexts and behaviors, including policing (Tyler & Huo, 2002; Sunshine & Tyler, 2003) and legal and regulatory contexts (Lind, Kulik, Ambrose, & de Vera Park, 1993; Lind, Greenberg, Scott, & Welchans, 2000; Murphy, 2004a).

However, while studies such as these have shown that perceptions of procedural justice can go on to affect short-term and long-term compliance behavior in a multitude of different areas, the psychological mechanisms underlying such behavior are not so clear. For example, why is it the case that some people are more likely to perceive procedural injustice than others, why is it that some people respond more negatively to procedural injustice than others, and why is it that some people go on to defy authority while others in the same situation do not? A number of studies have investigated deliberative and motivational processes that guide evaluations of justice, but such studies tend to ignore the feelings that are associated with perceptions of justice (for a similar argument see De Cremer & Van den Bos, 2007). In other words, procedural justice research has tended to ignore the emotions behind defiance and non-compliance. It is therefore proposed here that emotion theories have much to offer to the study of procedural justice.

In the justice literature there has been a debate over whether justice judgments should be thought of as rational–cognitive concepts or as subjective–affective constructs (see Haidt, 2001; Van den Bos, 2003). Proponents of the former view suggest that justice perceptions are the result of moral reasoning, while proponents of the latter view suggest that justice perceptions are the result of how they feel about the events they have encountered. If the justice concept is more subjective–affective in nature, then individual differences in one’s predisposition to react emotionally to an event should play an important moderating role in people’s reactions toward fair and unfair events. Although very few studies have explored the role of emotions in the procedural justice literature, the few that have been conducted tend to show that procedural justice and injustice lead to discrete emotional responses; those who see their experience as procedurally fair tend to display positive emotions such as joy or pride, while those who see an experience as procedurally unfair tend to display negative emotion such as anger.

Emotions and Procedural Justice

Scholars have only just begun to explore the role of emotions in relation to procedural justice (see De Cremer & Van den Bos, 2007). This is despite the fact that there had been numerous calls for such research to be undertaken (e.g., De Cremer & Van den Bos, 2007; Mikula, Scherer, & Athenstaedt, 1998; Weiss et al., 1999). Studying the relationship between emotions and procedural justice is particularly important because having a better understanding of how emotions can influence how people view procedures can help authorities to more effectively respond to and manage defiance and non-compliance.

The majority of studies in this area have tended to examine whether procedural justice goes on to predict different emotional reactions felt by participants. For example, Cropanzano and Folger (1989) found that when unfair outcomes were paired with unfair processes then this went on to produce negative emotions among participants. Similar findings were also obtained by Weiss et al. (1999). Assigning 122 students to conditions crossing either positive or negative outcomes with a procedure that was fair, biased in the participant’s favor, or biased in favor of another, Weiss et al. found that the emotion of happiness was overwhelmingly a function of outcome, with procedural fairness playing little role. Anger was highest when the outcome was unfavorable and the procedure was biased against the participant. Guilt was highest when the outcome was favorable and the procedure was biased in favor of the participant, and pride was highest whenever the outcome was favorable (for similar findings see Hegtvedt & Killian, 1999; Krehbiel & Cropanzano, 2000).

A small number of field studies have also obtained results that were similar to those obtained in the experimental research discussed above. In a study conducted in the health care context, Murphy-Berman, Cross, and Fondacaro (1999) assessed the relationship between individuals’ appraisals of procedural justice following health care treatment decisions. Respondents who felt they had been treated fairly by their health care provider were more likely to report more pride and pleasure as well as less anger as a result of their treatment. In another study, Chebat and Slusarczyk (2005) surveyed consumers who had previously made a complaint against a major Canadian bank. They found that emotions mediated the effect of justice concerns on their loyalty versus exit behavior from the bank. Those who felt they had been treated in a procedurally unfair manner by the bank were more likely to display negative emotions, and those who displayed negative emotions were subsequently less likely to remain loyal to that particular bank (see also VanYperen, Hagedoorn, Zweers, & Postma, 2000; Ball, Klebe-Trevino, & Sims, 1994; Murphy, 2004b; Murphy & Tyler, 2008).

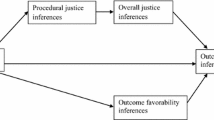

While the studies reported above all obtained significant effects, Van den Bos et al. (2003) argued that it is not uncommon in justice research to find weak or no effects on affective reactions from the experience of fair and unfair events. They suggested that failures to obtain effects might be due to the fact that previous research had failed to consider an important determinant of people’s affective reactions. The emotion literature, for example, has shown that people differ consistently in the typical intensity of their affective responses (Larsen & Diener, 1987; Larsen, Diener, & Emmons, 1986; Larsen, Diener, & Cropanzano, 1987). In other words, “when exposed to affect-eliciting events, certain individuals consistently manifest stronger or more intense affective responses whereas other persons show milder or less intense affective reactions” (Van den Bos et al., 2003, p. 153). Interestingly, research on affect intensity has shown that individual differences generalize over both positive and negative affect domains (Larsen et al., 1987), are stable over time, and consistent across situations (Larsen & Diener, 1987). In reviewing the affect literature, Van den Bos et al. (2003) therefore proposed that individual differences in affect intensity might determine how people react emotionally toward fair and unfair events. If justice judgments are based predominantly on a subjective–affective process, then we might expect that affect intensity would moderate the effect of procedural justice on behavioral and affective reactions.

Brockner et al. (1998, p. 395) further argued: “relatively few studies have investigated the moderating role of theoretically derived, individual difference variables”. Most studies that have addressed moderators of procedural justice effects have tended to examine situational factors such as the favorability of outcomes associated with a given event (e.g., Brockner & Wiesenfeld, 1996). Van den Bos et al. (2003), therefore, suggested that by studying the interaction between personality variables such as affect intensity and situations, justice researchers can generate further insights into how people will react to fairness and unfairness. In a laboratory study, Van den Bos et al. (2003) indeed found evidence to suggest that ‘affect intensity’ does determine how people react to affect-eliciting events. Using a student sample, they found that students high in affect intensity showed stronger affective reactions following the experience of procedural fairness compared to procedural unfairness, while no fairness effects were found for those low in affect intensity.Footnote 1

However, while the Van den Bos et al. (2003) study provides valuable insights into how people may react to fairness and unfairness in a laboratory setting, their findings remain untested in the field. As some scholars argue, processes in laboratory studies may operate quite differently to field settings (e.g., Greenhalgh & Chapman, 1995; Rhoades, Arnold, & Jay, 2001). At the very least, the external validity of such studies, and their generalizability to real world phenomena can be called into question. The aim of this research, therefore, is to extend the work of Van den Bos et al. (2003) by exploring the role that affect intensity has on reactions in real-life settings among people who have had recent experience with a legal authority. Study 1 examined these processes among tax offenders who had been through a serious regulatory enforcement experience, and Study 2 examined these processes among citizens who had recent contact with a police officer.

Study 1—Taxation Context

Using cross-sectional survey data collected from tax offenders who were caught and punished by the Australian Taxation Office (ATO), Study 1 explored the degree to which affect intensity moderates the effect of perceived procedural justice on taxpayers’ affective reactions to their punishment. With emotions likely to be running high in such a situation, studying the effects of an actual regulatory enforcement experience provides a perfect opportunity for studying the relationship between affect intensity and procedural justice perceptions. Given that enforcement experiences are more likely to elicit strong negative as opposed to positive emotions, negative affective reactions in particular were studied. The emotional reaction of anger was chosen because previous justice research has found a strong link between perceptions of procedural unfairness and anger, especially if accompanied by an unfavorable outcome (e.g., Weiss et al., 1999).

Rather than focusing only on how affect intensity and procedural justice variables interact to predict affective reactions, however, this study also explores how affect intensity interacts with perceptions of procedural justice to predict reports of subsequent behavior. Given that a significant body of work has found that perceptions of procedural justice predict compliance behavior, I explored whether individual differences in affect intensity moderated this well-established relationship.Footnote 2 The sample used in Study 1 consists of punished tax offenders. Such a group therefore provides a good sample for exploring compliance behavior in a realistic environment.Footnote 3

Based on previous research, first, it was hypothesized that anger would be higher among those who viewed their enforcement experience to be procedurally unfair and that compliance behavior would be lower among those who viewed their experience to be procedurally unfair. Second, it was hypothesized that those higher in affect intensity would express more anger than those lower in affect intensity, and those higher in affect intensity should be more likely to report higher levels of non-compliant behavior than those low in affect intensity. Third, it was hypothesized that procedural justice would have a greater effect in reducing anger and non-compliance among those taxpayers who were relatively high in affect intensity.

Method

Participants and Procedure

The 652 taxpayers who participated in Study 1 had all been caught by the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) engaging in an illegal form of tax avoidance (for more on this group and their enforcement experience see Murphy, 2003). The names and addresses of 32,493 tax offenders were available for selection from the ATO’s case files. In 2004, a stratified nationwide random sample of 1,250 tax offenders was sent a 28-page survey. The sample was stratified by Australian State and Territory jurisdiction. For example, from the sampling frame available from the ATO, it was found that 42% of the overall population of tax offenders resided in the State of Western Australia. Hence, 42% of the sample was randomly selected from this State, and so on for the remaining Australian States and Territories. Tax offenders were invited to participate in a study that addressed taxpayer views of the ATO and their enforcement processes. Tax offenders were informed that their responses would be anonymous and would not be used against them by the ATO. Using the Dillman Total Design Method (Dillman, 1978), non-respondents were followed up over time using an identification number that was affixed to each survey booklet. For those people who had not returned a completed survey within a given time frame, they were sent a reminder letter encouraging them to participate in the study. A further two reminder mailings were made, and after a period of approximately three months, a total of 652 useable surveys were received. Of the original 1,250 tax offenders who were sent a survey, 146 could not be contacted or indicated they were incapable of completing the survey. After deleting these 146 people from the list of 1,250 tax offenders sampled, the response rate was 59%.

Respondents in the final sample were between 25 and 76 years of age (M = 50.43, SD = 9.00), 83% were male, 46% had received a university education, and their average personal income was approximately AUS$79,000. Using the limited amount of demographic data provided by the ATO (i.e., state of residence and sex), the sample proved to be representative of the overall Australian tax offender population.

Measures

The survey sent to tax offenders contained over 200 questions designed to measure their views on paying taxes, what they thought of the ATO and the tax system, and how they felt about their enforcement experience. Also assessed were self-reported tax behaviors. For the purposes of this study, the following categories of variables from the tax offender survey were of interest: (1) perceptions of procedural justice during the enforcement process, (2) affect intensity, (3) emotions of anger, and (4) self-reported tax compliance behavior. Prior to forming these scales, the items used to construct the scales were subjected to a factor analysis (see Results section below). Table 1 presents the means, standard deviations, and alpha reliability coefficients for each of the scales and bivariate correlations among the scales. The Appendix presents all the items used to construct each scale.

Procedural Justice

Perceptions of procedural justice were measured using eight items adapted from Tyler (1990). For example, ‘The ATO tries to be fair when making their decisions.’ They included Tyler’s three sub-concepts of neutrality, fairness, and respect. Higher scores indicated more likelihood to perceive the ATO as acting in a procedurally fair manner during the enforcement process.

Affect Intensity

Affect intensity was measured using Braithwaite’s (1987) eight-item scale of general emotional arousability. The emotionality scale has been validated on an Australian adult sample and measures the degree to which people respond emotionally or unemotionally to stressful events. For example, ‘I am somewhat emotional.’ Higher scores indicate higher levels of affect intensity.

Affective Reactions of Anger

Respondents completed questions about how they felt in response to having been caught and punished by the ATO. Taxpayer anger in response to the enforcement experience was measured using four items developed by the author. For example, ‘I felt resentful toward the ATO.’ Higher scores indicate greater levels of anger.

Tax Non-Compliance

Taxpayers completed four questions about how they thought their enforcement experience had affected their taxpaying behavior. For example, ‘I now try to avoid paying as much tax as possible.’ Higher scores indicate more self-reported non-compliance.

Results

Factor Analysis

To test for the hypothesized conceptual differentiation between the variables used to construct the scales of interest, a principal-components factor analysis using varimax rotation was performed. The eigenvalues (5.49, 3.70, 2.33, 1.52, 0.90, 0.86, 0.82) and scree plot of this analysis suggested that four factors should be extracted. Inspection of the rotated factor structure (see Table 2) shows that all items loaded clearly and as anticipated onto their respective factors. Factor 1 comprised eight items that measured perceptions of procedural justice, Factor 2 comprised eight items that measured affect intensity, Factor 3 comprised four items that measured self-reported tax non-compliance behavior, and Factor 4 comprised four items that measured feelings of anger.

Bivariate Relationships Among Scale Scores

Table 1 presents the bivariate correlations among scores on all scales measured, and the relationships among scales are all as expected. Procedural justice was negatively related to feelings of anger and to tax non-compliance behavior. In other words, those who felt the ATO was procedurally fair in their dealings with taxpayers were less likely to feel anger and less likely to report having subsequently evaded their taxes as a result. There was also a negative relationship between procedural justice and affect intensity, indicating that those higher in affect intensity were less likely to make positive procedural justice judgments. Affect intensity was also positively related to anger and to tax non-compliance. Those who were higher in affect intensity were more likely to express feelings of anger regarding their enforcement experience, and more likely to report having evaded taxes in subsequent years. Finally, those who felt more anger over their enforcement experience were also more likely to report having evaded their taxes in the years following their enforcement experience.

Regression Analyses

In order to test whether affect intensity moderates the effect of procedural justice on affective reactions and compliance behavior, two separate hierarchical regression analyses were conducted. The first analysis used ‘affect intensity’ and ‘procedural justice’ measures to predict the affective reaction of ‘anger’, and the second used ‘affect intensity’ and ‘procedural justice’ to predict self-reported ‘tax non-compliance’ behavior. All variables were centered prior to analysis.

Predicting Affective Reactions—Anger

As shown in Table 3, both ‘procedural justice’ and ‘affect intensity’ had significant main effects on the affective reaction of ‘anger’, indicating that taxpayers were more likely to be angry when (a) they felt they had been treated in a procedurally unfair manner, and (b) their level of affect intensity was higher. Figure 1a confirms that anger levels for those high in affect intensity were higher overall compared to those who were low in affect intensity. Similarly, anger was lower overall when taxpayers felt the ATO treated them with procedural justice.

Interestingly, and in opposition to Van den Bos et al.’s (2003) findings, a significant interaction between procedural justice and affect intensity indicates that procedural justice was more effective in reducing anger for those low in affect intensity than those high in affect intensity (β = 0.08, p < 0.05). The simple-slope analyses confirmed that procedural justice had a significant influence upon anger levels, but that it had a stronger effect in reducing anger among those lower in affect intensity (β = −0.45, p < 0.001) than for those high in affect intensity (β = −0.30, p < 0.001). These results reveal that individual differences in affect intensity moderate the effect of procedural justice on the affective emotion of anger.

Predicting Self-Reported Tax Non-Compliance Behavior

The second regression analysis tested whether levels of affect intensity moderated the effect of procedural justice on self-reported compliance behavior. Although previous research has examined the role that affect intensity plays on subsequent affective reactions to fairness or unfairness (see Van den Bos et al., 2003), there have been no studies published to date that have examined the influence of affect intensity on self-reported compliance behavior.

The results presented in Table 4 parallel those displayed in Table 3. Procedural justice had a negative effect on tax-evasion behavior, while affect intensity had a positive effect on tax-evasion behavior. Those higher in affect intensity were more likely to report further tax-evasion behavior, and those more likely to perceive the ATO’s treatment of them to be procedurally fair were less likely to report further tax-evasion behavior after their enforcement experience. The interaction between procedural justice and affect intensity on evasion behavior was also significant (β = 0.08, p < 0.05). As shown in Fig. 1b, simple slope analyses showed that procedural justice significantly predicted reductions in non-compliance for taxpayers who were low in affect intensity (β = −0.21 p < 0.001) but did not predict non-compliance behavior for taxpayers who were high in affect intensity (β = −0.05, ns). In other words, compliance was lower among taxpayers who felt that the ATO had treated them fairly compared to when they felt that the ATO had treated them unfairly, but only if they were low in affect intensity. These results reveal that individual differences in affect intensity also moderate the effect of procedural justice on self-reported compliance behavior.

Discussion

In summary, it was found in Study 1 that procedural justice predicted tax offenders’ affective reactions and self-reported compliance behavior. Tax offenders who were more likely to feel the ATO used procedural justice during their enforcement experience were less likely to feel anger and were less likely to report having engaged in further tax-evasion behavior after their enforcement experience. Also as expected, affect intensity played a role in predicting affective reactions and compliance behavior. Those higher in affect intensity were more likely to express anger in response to their enforcement experience and report further tax-evasion after their enforcement experience. Interestingly, affect intensity moderated the effect of procedural justice on taxpayers’ affective reactions. However, it was in the opposite direction to that predicted by Van den Bos et al. (2003), who found that students high in affect intensity showed stronger emotional reactions following the experience of procedural fairness compared to experiences of procedural unfairness. When affect intensity was low, no fairness effects were found. In this study, fairness effects were found to be stronger on both affective reactions and compliance behavior for tax offenders low in affect intensity.

One possible explanation for the unexpected interaction effect reported in Study 1 is that the tax offenders studied had all been punished for their involvement in illegal activity. Such an experience can be extremely stressful and humiliating, and may affect responses differently to those observed in the Van den Bos et al. study. In the Van den Bos et al. (2003) study none of the participants were asked to imagine themselves in an enforcement experience with a legal authority. The act of punishment may therefore be a pre-condition for the interaction effect observed in Study 1. Before speculating about this possibility any further, however, it would seem prudent to examine whether a similar interaction effect could be replicated in a group of people who have had a recent experience with a legal authority, but who have not been punished.

Study 2—Policing Context

The findings of Study 1 indicate that affect intensity moderates the relationship between procedural justice and both affective reactions and compliance behavior, but in the opposite direction to that expected. Study 2 was conducted to ascertain whether a similar finding could also be found in a law enforcement context where people had not been punished during their encounter with the legal authority. Specifically, in Study 2 people with recent routine contact with a police officer were surveyed about their experience.

Method

Participants and Procedure

In 2007, 5,700 surveys were posted to a stratified random sample of Australian citizens. The sample was again stratified by State and Territory jurisdiction. The aim of the survey was to gauge public views about policing in Australia. Participants were chosen from the publicly available electoral roll (all Australian citizens over the age of 18 years). Non-respondents were followed up three times, after which a total of 2,120 completed surveys were returned. After taking into account out-of-scope participants (i.e., those who had moved address or died since the electoral roll was last updated; N = 438), an adjusted response rate of 40% was obtained. Respondents in the final sample were between 14 and 98 years of age (M = 51.48, SD = 16.17),Footnote 4 46% were male, 71% identified their main ethnic or national group background to be Australian, 72% of respondents were married, and 60% had attained a tertiary qualification. The average family income was reported to be AUS$79,120 (SD = $53,510). Using 2006 Australian Census data, the sample was found to be broadly representative of the overall Australian population. However, like many mail surveys, older and more educated people tended to be over-represented. Men were also slightly under-represented in the survey relative to population data.

Among the 2,120 respondents were 876 who indicated they had been approached by a police officer at least once in the year prior to completing the survey. This contact could include random breath testing, being issued a traffic infringement notice, or being asked for information, to name a few. For 204 of these 876 citizens, the nature of the police contact involved an enforcement experience (e.g., traffic violation, speeding offence). These 204 citizens were therefore excluded from the analysis, leaving a total of 672 citizens as the target sample.

Across both Study 1 and Study 2, therefore, all respondents had had direct contact with a legal authority. In Study 1, however, respondents had been punished by the legal authority, while in Study 2 they had not. If it is the case that punishment is a pre-condition to obtaining the unexpected interaction effect in Study 1, then in Study 2 one would expect to find the opposite interaction effect to that obtained in Study 1.

Measures

Specific issues of interest to the 18-page policing survey were (1) citizens’ self reported willingness to cooperate with police, (2) their sense of obligation to obey the law, (3) the postures they adopt toward authority and the law, (4) perceptions of the legitimacy of policing in Australia (5) perceptions of fairness in Australia's law enforcement system, (6) satisfaction with police services, and (7) experiences with crime, fear of crime, and policing in Australia. For the purposes of Study 2, only questions measuring perceptions of procedural justice during a recent encounter with a police officer, affect intensity, emotions of anger, and self-reported compliance behavior were of interest. Again, a factor analysis was conducted before these scales were constructed (see Results section below). Table 5 presents the means, standard deviations, Cronbach alpha reliability coefficients, and bivariate correlations among each of the scales used in Study 2. As can be seen in Table 5, the variables used yielded reliable scales, and all bivariate correlations among the scales replicated those relationships obtained in Study 1.

Procedural Justice

In Study 2, the procedural justice scale was constructed using four items. For example, ‘Thinking about your most recent contact with police, were the police polite, respectful and courteous?’. Higher scores indicated that survey participants were more likely to believe that they had been treated with procedural justice by the police officer they had contact with.

Affect Intensity

To ensure consistency between Study 1 and Study 2, affect intensity was again measured in Study 2 using Braithwaite’s (1987) eight-item scale of emotional arousability (see Appendix). As a result of the factor analysis, however, only six of the original eight items were used in Study 2. Higher scores indicate higher levels of affect intensity.

Affective Reactions of Anger

Respondents were asked a series of questions to ascertain whether their recent contact with the police caused them any anger. Anger was measured using five items. For example, ‘When you think about the way you were treated during your most recent contact with police, do you feel angry?’ Higher scores indicate greater levels of anger with their police experience.

Defiance

Compliance in the policing context was measured using a two-item defiance scale. For example, ‘I don’t care if I’m not doing the right thing by police’. Those scoring higher on this scale were more defiant toward the police.

Results

The same procedures used in Study 1 were again followed in Study 2 to examine whether Study 1 findings could be replicated in a different law enforcement context. All variables were again centered prior to analysis.

Factor Analysis

A principal-components factor analysis using varimax rotation was first conducted in Study 2 to test for the assumed conceptual differentiation between all variables used. Like in Study 1, the eigenvalues (6.00, 2.62, 1.30, 1.15, 0.98, 0.82, 0.72) and scree plot of this analysis again suggested that four factors should be extracted.Footnote 5 Inspection of the rotated factor structure (see Table 6) shows that all items loaded clearly and as anticipated onto their respective factors. Factor 1 comprised five items that measured feelings of anger, Factor 2 comprised six items that measured affect intensity, Factor 3 comprised four items that measured perceptions of procedural justice, and Factor 4 comprised two items that measured defiance toward the police.

Regression Analyses

Predicting Affective Reactions—Anger

Replicating Study 1, Table 7 shows that ‘procedural justice’ and ‘affect intensity’ independently predicted the affective reaction of ‘anger’. Citizens who reported a recent encounter with the police were more likely to be angry with the police when they felt that the police had not treated them with procedural justice, and citizens higher in affect intensity were also more likely to feel angry about their treatment. As shown in Fig. 2a, anger levels for those high in affect intensity were higher overall compared with those who were low in affect intensity. Anger was also lower overall when citizens felt the police treated them with procedural justice. Of interest, however, were the results of the interaction between affect intensity and procedural justice on the affective reaction of anger. Here, the interaction term was not significant. Hence, the results obtained in Study 1 were not replicated in Study 2, at least for the affective reaction of anger.

However, this failure to find a significant interaction in Study 2 can be quite easily explained. As can be seen in Fig. 2a, anger levels among those citizens low in affect intensity were particularly low, even when they perceived treatment by the police officer to be procedurally unfair. It is therefore possible that a floor effect could have masked a stronger effect for procedural justice for this particular group of citizens. The policing context examined elicited less extreme affective responses, thereby making a significant interaction effect between affect intensity and procedural justice on anger less likely.

Predicting Compliance Behavior—Defiance

The final regression analysis tested whether levels of affect intensity moderated the effect of procedural justice on compliance behavior, as it did in the taxation context reported in Study 1. Compliance behavior in Study 2 was measured as self-reported defiance toward police.

Replicating Study 1, procedural justice was negatively related to defiance behavior, and affect intensity was positively related to defiance behavior (see Table 8). As shown in Fig. 2b, those higher in affect intensity were more likely to report defiant behavior, and those more likely to perceive their treatment by a police officer to be procedurally fair were less likely to report being defiant toward police.

The relationship between procedural justice and affect intensity also replicated Study 1 findings. Specifically, the interaction between these two variables on compliance behavior was also significant in the same direction observed in Study 1 (β = 0.09, p < 0.05). Exploring this interaction effect further, simple slope analyses showed that procedural justice more strongly predicted defiance reduction toward police for those low in affect intensity (β = −0.38, p < 0.001) than for those high in affect intensity (β = −0.22, p < 0.001). In other words, defiance was lower among citizens low in affect intensity when they felt the police treated them fairly compared to when they felt the police treated them unfairly.Footnote 6

Discussion

In general, the results of Study 2 replicate those obtained in Study 1. The interaction effect in Study 2 is particularly important as it replicates the unexpected interaction effect obtained in Study 1. It also demonstrates that the finding is robust (at least when predicting compliance behavior) across different contexts and situations. In particular, the findings obtained in Study 2 suggest that the act of punishment experienced by taxpayers in Study 1 was unlikely to be responsible for the unexpected interaction effect. Perhaps the finding has more to do with participants being exposed to a regulatory encounter, rather than an enforcement encounter per se. This suggestion of course should be tested empirically in future research.

General Discussion

To date, there have been few empirical studies that have explored either the role of emotion in the formation of procedural justice judgments or in emotional reactions to procedural injustice. Even rarer are procedural justice studies that explore the moderating role of individual difference variables on subsequent reactions and behaviors. The aim of this study, therefore, was to explore the role that individual differences in ‘affect intensity’ played in producing different reactions to procedural justice and injustice.

Preceding this research, only one study to my knowledge has been published which specifically investigated the interaction between affect intensity and procedural justice on affective reactions. In that study, Van den Bos et al. (2003) found that students’ level of affect intensity moderated the effect of procedural justice on affective reactions. Those students high in affect intensity showed stronger affective reactions following the experience of procedural fairness compared to unfairness, whereas students low in affect intensity showed no fairness effects. This study aimed to replicate these findings in two field-settings. This study also sought to extend Van den Bos et al.’s study by examining the interaction between perceptions of procedural justice and affect intensity on self-reported compliance behavior.

Summary of Results

In summary, it was found that procedural justice predicted both affective reactions and self-reported compliance behavior. Those who were more likely to feel the authority (ATO or police) were procedurally fair during their encounters with the respondents were less likely to feel anger, and were also less likely to report being non-compliant. It was also found that affect intensity played a role in predicting affective reactions and compliance behavior. Tax offenders higher in affect intensity were more likely to express anger in response to their enforcement experience, and were also more likely to report further evading their taxes after their enforcement experience. Citizens higher in affect intensity were more likely to express anger in response to their encounter with a police officer, and were also more likely to report higher levels of defiance toward police. More importantly, in Study 1 affect intensity was found to moderate the relation between procedural justice and taxpayers’ affective reactions. However, the relation was in the opposite direction to that predicted. Whereas overall affective reactions were more extreme among those high in affect intensity, procedural justice more strongly predicted anger reduction for those low in affect intensity compared with those high in affect intensity. In both Study 1 and Study 2, affect intensity interacted with procedural justice to more strongly predict self-reported compliance behavior among those low in affect intensity than high in affect intensity.

If we relate these findings back to previous research we can draw some interesting comparisons. We can see that three of the major findings support claims that have been made in earlier procedural justice research. For example, a number of studies have found procedural justice to have a significant effect on discrete emotions. In general, it has been found that people experiencing procedural justice are more likely to experience the emotions of happiness, joy, pride, and guilt, whereas people experiencing procedural injustice are more likely to experience the emotions of disappointment, anger, frustration, and anxiety (e.g., Hegtvedt & Killian, 1999; Krehbiel & Cropanzano, 2000; Weiss et al., 1999). The findings of this study replicate these prior emotion studies by showing that respondents in both Study 1 and Study 2 were more likely to experience anger if they believed the authority (ATO or police, respectively) acted in a procedurally unfair manner during their encounter. Second, the commonly observed relationship between procedural justice and compliance behavior (e.g., Tyler, 2006; Braithwaite & Makkai, 1994) was also replicated in this study. Tax offenders who felt the ATO used procedural fairness during their enforcement experience were less likely to report further non-compliance following their enforcement experience, and citizens who felt the police treated them fairly were less likely to report defiance toward the police. Third, as discussed in the Introduction, the affect literature has revealed that certain people consistently react more strongly or display more intense emotional responses to affect-eliciting events (e.g., Larsen & Diener, 1987; Larsen et al., 1986, 1987). This study also showed support for this contention. Those people found to be higher in affect intensity were more likely to express stronger feelings of anger, and they were more likely to report engaging in further forms of non-compliance or defiance.

Where the findings of this study differed from previous research, however, was in the direction of the interaction effect observed between procedural justice and affect intensity variables. Van den Bos et al. (2003) observed an interaction between these two variables on student-affective reactions. Specifically, they found that students high in affect intensity showed stronger emotional reactions following the experience of procedural fairness compared to experiences of procedural unfairness. When affect intensity was low, no fairness effects were found. In this study, fairness effects were found to be stronger on both affective reactions (Study 1) and compliance behavior (Study 1 and Study 2) for those who were low in affect intensity than for those high in affect intensity. These findings are important because they suggest that more needs to be done to tease apart the conditions under which affect intensity moderates the effect of procedural justice on both emotional reactions and compliance behavior.

Possible Explanations for the Conflicting Interaction Effects

How might the conflicting interaction results between this study and the Van den Bos et al. (2003) study be explained? The first possible explanation is a methodological one. The difference in results could simply reflect the fact that the affect intensity measures were different between the two studies. In the Van den Bos et al. (2003) study, affect intensity was measured using a well-established affect intensity scale developed by Larsen et al. (1986). Respondents in the Van den Bos study were asked to respond to a 40-item questionnaire, which was designed to measure a person’s predisposition to react emotionally to typical life situations. The measure used in this study, in contrast, comprised items that were originally developed by Braithwaite (1987) to assess a person’s degree of general emotional arousability. In this study, participants were specifically asked to indicate how they would react in response to a stressful situation. Those who indicated that they would be more likely to react in a calm and collected manner were more likely to be positively influenced by procedural justice. Those who indicated that they were more likely to react emotionally to a stressful situation tended to be less influenced by fair treatment. Perhaps the interaction effects in this study may have been different had the affect intensity scale been the same as that used in the Van den Bos et al.’s (2003) study, although a theoretical explanation for why this might occur remains unclear.

A second possible explanation for the conflicting results obtained between this study and the Van den Bos et al. (2003) study is related to the methodological approach adopted by each study. In this study, a non-experimental approach was adopted, whereas in Van den Bos et al.’s (2003) research program an experimental methodology was adopted. As highlighted earlier in the Introduction, researchers have noted that processes in laboratory studies may operate differently to field settings (Greenhalgh & Chapman, 1995; Rhoades et al., 2001). It has also been noted by several researchers that experimentalists and non-experimentalists frequently detect different interaction effects in studies designed to investigate the same subset of variables (see McClelland & Judd, 1993; Brown & Lord, 1999). The most common criticism levelled against experimental research is that the populations most typically utilized are students, and that such studies therefore lack external validity (and the Van den Bos et al. study is no exception here). My point here is not to suggest that one method is inherently superior to the other, but rather this difference in methodology could offer a suitable explanation for the conflicting results.

A third possible explanation for the conflicting results comes from observing the pattern of findings from previous procedural justice research focused on alternative individual difference factors. Brockner et al. (1998) found that individual differences in self-esteem moderated the impact of procedural justice on individuals’ reactions. They found that procedural justice was more strongly related to reactions of people who were high in self-esteem than of people low in self-esteem. However, in drawing conclusions about their study, Brockner et al. (1998) were careful not to suggest that people high in self-esteem would be more influenced than people low in self-esteem by all aspects of procedural fairness. They used the results of an unpublished study that had revealed the opposite interaction effect to make this claim (for the now published version of that article see Vermunt et al., 2001). Vermunt et al. (2001) found that procedural fairness information was more strongly related to the reactions of people low in self-esteem. A suggestion made by Brockner et al. (1998) to explain the discrepancy between the two studies was that the procedural information studied in the Vermunt et al. study did not pertain to voice. Rather, it referred to interactional justice: the perceived quality of the interpersonal treatment the participants had received. Participants in the Vermunt et al. study had recently been arrested and were being detained in police stations or jails. While under detention, they were asked to rate the extent to which they had been treated with respect and consideration by their custodial officer (a more comparable context to this study). Procedural justice in the Brockner et al. (1998) study, however, was operationalized as the degree of voice participants were given in decision-making processes (voice versus no-voice).

In the Van den Bos et al. (2003) study—on which this study is based—procedural justice was also operationalized as the degree of voice provided to the participant. Participants in the former study either received or did not receive an opportunity to voice their opinion about a decision made by the experimenter. In the case of the present study, the procedural information studied was more similar to that measured by the Vermunt et al. (2001) study. In Study 1, taxpayers were asked to rate the interpersonal treatment they had received from the ATO during their enforcement experience, and in Study 2, citizens were asked to rate the treatment they received from a police officer during a routine encounter. Given the same conflicting pattern of results were observed across both the self-esteem and the affect intensity studies, there may perhaps be something special about allowing people voice in a decision process that particularly affects people high in affect intensity. Other procedural fairness factors besides voice (e.g., interactional justice factors), in contrast, may be more likely to affect people low in affect intensity. Of course, this claim would have to be tested empirically in future research to see whether it holds up across different studies using different individual difference and procedural justice variables.

Although the three suggestions proposed above may provide an explanation for the conflicting results between studies, they are not able to provide a theoretical justification for why those low in affect intensity might be more affected by interpersonal forms of procedural justice than those high in affect intensity? I would like to put forth a possible suggestion. Buss and Plomin (1984) suggest that highly emotional people are more likely to become distressed when confronted with emotional stimuli, and that they react with higher levels of emotional arousal. The findings of this study support this. Those higher in affect intensity reported being angrier about their experiences with authority than those lower in affect intensity. It might therefore be expected that a person high in affect intensity (i.e., someone who is highly emotional) might be harder to soothe when distressed. This follows that procedural justice may be less effective in stabilizing the emotions or behaviors of people who are highly emotional. Further empirical evidence to support this suggestion comes from a study conducted in the nursing home context by Makkai and Braithwaite (1994). Using the same affect intensity scale as this study, Makkai and Braithwaite found that deterrence-based strategies used by nursing home inspectors were only effective in encouraging future compliance among nursing home managers who were low in affect intensity. Deterrence was less effective for those high in affect intensity.Footnote 7 Such a finding parallels those obtained in this study, and also contradicts those obtained by Van den Bos et al. (2003).

The common feature between this study and the Makkai and Braithwaite study is that all participants in both studies had had an encounter with a legal authority. In contrast, in the Van den Bos et al. (2003) study, the authority was an experimenter in a first-year psychology study. Makkai and Braithwaite explained their pattern of results using Scheff and Retzinger’s (1991) theory of emotions. Scheff and Retzinger argue that certain people respond more negatively to experiences that elicit shame. They argue that feelings of shame can be transformed into rage or defiance, particularly when shame is not acknowledged appropriately. Makkai and Braithwaite argue that encounters with legal authorities are particularly likely to elicit feelings of shame. Makkai and Braithwaite (1994, p. 364) further suggest that the affect intensity measure used in their study—as well as was also used in this study—would “most likely be interpreted by Scheff and Retzinger as evincing a propensity to bypass shame instead of acknowledging shame and dealing with it”. In other words, they argue that those who score high on the affect intensity measure are those who are more likely to read encounters with legal authorities to be shameful in nature. Given their inability to bypass these feelings of shame adequately, as a coping mechanism, they transform their feelings into anger and defiance. In line with Buss and Plomin (1984), Makkai and Braithwaite (1994) see such people as being extremely difficult to deal with in a regulatory environment (another suggestion that procedural justice may prove less effective in soothing those high in affect intensity). I suggest that an encounter with a legal authority, even if that encounter does not result in enforcement action, can lead people high in affect intensity to experience greater feelings of humiliation and shame than those low in affect intensity in response to their encounter. This could be a valid reason for why this study, as well as the Makkai and Braithwaite study, produced the pattern of results that they did. Perhaps there is something unusual about encounters with legal authorities that elicit greater feelings of shame than encounters with other types of authorities. In the case of the taxation study reported in Study 1, all participants had been punished by the tax authority. Hence, it is not difficult to see that such a situation is likely to elicit shame (see Murphy & Harris, 2007). In the case of the policing study reported in Study 2, however, it is also proposed that such an encounter can elicit feelings of shame, especially for those high in affect intensity. For example, we all know the unpleasant feelings we experience when being approached by a police officer, even if we have done nothing wrong. We worry about what others may think seeing a police officer approach us, or whether those driving by during a routine random breath test may wonder whether we have been pulled over for a traffic violation. So in summary, coupled with the findings from the Makkai and Braithwaite study, and the suggestions made by Buss and Plomin (1984), findings from this study suggest that highly emotional people might be fundamentally more difficult to manage in a regulatory system because they are always more likely to interpret encounters with regulatory authority in a somewhat negative light.

Implications for Procedural Justice Theory and Research

The findings of this study have several implications for procedural justice research. First, they show that individual difference variables can be important for predicting how people may react to various situations. In the case of this study, the individual difference variable of affect intensity was shown to play an important role in people’s reactions to perceived injustice. In fact, it was shown that people’s affective reactions, as well as their compliance behavior, following fair or unfair events can be moderated by people’s propensity to react strongly or mildly toward affect-eliciting events. Such findings are important because they show that investigating the role of individual difference variables in the social justice literature can throw further insights into people’s reactions to justice and injustice.

Second, and perhaps more importantly, the findings of this study lend support to the view that procedural justice may be somewhat subjective in nature. Take for example, the way the ATO generally deals with taxpayers. The ATO generally uses an automated lettering system to communicate and gain compliance from non-compliant taxpayers. These letters are generally produced using a letter template and are constructed in such a way so that the messages contained within them are kept consistent across all taxpayers who receive them. All taxpayers involved in this study would therefore have received similarly worded letters informing them that their tax deductions relating to their involvement in tax avoidance schemes had been disallowed under the anti-avoidance provisions of the Australian Income Tax Assessment Act, and that they were required to repay their tax with interest and penalties within two weeks of the date of notice (hence, it can be assumed that the type of treatment taxpayers received over their non-compliance was kept relatively constant).Footnote 8 Yet the findings show that some of these taxpayers reacted more negatively to the enforcement process than did others. As was discussed briefly in the Introduction, there is a debate in the justice literature over whether a justice judgment should be conceived of as a judgment that is the result of a rational–cognitive process, or alternatively, as a subjective–affective process. It was suggested that if a judgement about procedural justice involves a subjective–affective process then it should be the case that affect intensity plays a moderating role in people’s reactions toward fair and unfair events. This study indeed found evidence to suggest that affect intensity moderates the effects of procedural justice on both affective reactions and compliance behavior. Some other research has also hinted at the subjective quality of procedural justice. Using an experimental technique, Van den Bos (2003) found that students who had been put into a positive mood prior to making procedural justice judgments were significantly more likely to judge the way in which they had been treated by the experimenter to be procedurally fair. Those in negative moods were in turn consistently more likely to judge their treatment by the experimenter to be procedurally unfair.

Related to this issue, the results of this study suggest that procedural justice (at least when operationalized as interactional justice) may be less effective in shaping reactions and behaviors among certain types of people. The procedural justice literature argues that authorities will be particularly effective in shaping behavior if they use strategies that are seen to be procedurally fair (e.g., Tyler & Huo, 2002). The findings of this study, however, suggest that it may not be this simple. Whereas the results of this study show that affective reactions and behaviors are, in general, positively shaped by fair treatment, it was found that people high in affect intensity were less affected by procedural justice than people low in affect intensity. Personality theorists suggest that the psychological effect of a situation depends on how a person interprets the situation and that such differences in interpretation can vary as a function of individual difference factors (Mischel, 1973; Shoda & Mischel, 1993). Taken together, this therefore suggests that authorities need to consider carefully how their specific enforcement strategies may be interpreted by different groups of people if they wish to more successfully shape reactions to their procedures.

Strengths and Limitations of This Study

A major strength of this study is that it is one of the only two studies to provide evidence to show that individual differences in affect intensity can moderate the effect of procedural justice on people’s affective reactions. As outlined previously, Van den Bos et al. (2003) were the first to systematically examine whether affect intensity interacted with procedural justice to have an effect on affective reactions. However, they failed to ascertain whether the interaction could also be extended to behavioral reactions. This study, therefore, advances previous research by also showing how affect intensity moderates the effect of procedural justice on subsequent compliance behavior. It did so in two field settings (taxation and policing).

This study, however, has several important limitations that should be noted. First, there are limitations related to the use of cross-sectional survey data. As is the case with all cross-sectional survey studies, the causal relationships between variables of interest are possibly obscured. Only correlational relationships between variables of interest can be ascertained. Second, it is also important to note that a self-report measure of compliance was used in both Study 1 and Study 2. A method that relies on the honesty of the surveyed participants to disclose dishonest behavior is obviously vulnerable to a challenge to its validity. However, participants were made aware their responses would be kept confidential, and a strong tradition of research in criminology supports the validity of using self-report data in such circumstances (Maxfield & Babbie, 2008; Thornberry & Krohn, 2000). Third, the affect intensity variable was different from that which has been used in previous justice research. This may have affected the results. Future research should therefore attempt to examine these issues in a field context using the traditional measure of affect intensity. Fourth, the taxpayers used in this study had all been subjected to an enforcement experience. As noted in the Introduction, enforcement experiences are more likely than not to raise negative sentiments and reactions. Further, all tax offenders involved had received a significant monetary penalty. This study therefore assessed a negative affect-eliciting situation. In Study 2, all the citizens had a personal encounter with a police officer. For many, even a non-enforcement encounter with a legal authority can be intimidating. Future research may therefore want to explore whether the relationships obtained in this study can be replicated across a context where the people involved felt happy about an outcome or situation (i.e., a positive affect-eliciting situation), and where the authority may not necessarily be a regulatory authority.

Conclusion

Although several limitations have been identified, these do not detract from the importance of the findings from this study. The findings from this study evidently have a number of important implications for justice research and regulatory policy. This study has advanced the literature on procedural justice by demonstrating that individual difference variables can moderate the effect of procedural justice on affective reactions and behaviors. Specifically, procedural justice was found to have a greater effect in reducing anger and non-compliance levels among those lower in affect intensity compared to those higher in affect intensity. These findings are particularly important because they suggest a subjective–affective process may be involved in the formation of procedural justice judgments. When trying to explain why some people react more positively or negatively to procedural justice than others, researchers might therefore benefit by further considering individual differences in affect intensity.

Notes

This result was replicated in a second study substituting distributive justice in the place of procedural justice (see Van den Bos et al., 2003).

Although a few studies have explored the impact that affect intensity has on self-reported behavior (see for example, Rhoades et al., 2001), as far as I am aware, no one has yet examined this relationship in the context of procedural justice. Van den Bos et al. (2003) examined affective reactions, not compliance behavior.

Of course, it should be kept in mind that due to the cross-sectional nature of the data used in this study, it is unclear whether procedural justice perceptions cause subsequent behavioral reactions, or whether perceptions of procedural injustice may be used as excuses for people to rationalize their reactions or behaviors.

Only one respondent was younger than 18 years of age, which indicates that this respondent completed a survey that was not addressed to them personally.

Note that two items from the affect intensity scale were removed prior to running this final analysis, as their inclusion in the original analysis resulted in five factors being extracted.

It should be noted that an additional set of regression analyses were conducted on the 204 citizens excluded from Study 2. When this group was included in the overall analysis, it was found that the pattern of results replicated those of the 672 citizens reported in Study 2, and all relationships were in the direction expected. When the 204 citizens were considered alone, however, neither of the interactions reached significance, although the relationships were still in the direction expected. Hence, one can be confident in concluding that a ‘punishment’ experience does not significantly qualify the different pattern of results obtained in this study from those obtained by Van den Bos et al. (2003).

Procedural justice, like deterrence, can be used by authorities as a regulatory tool to manage compliance behavior.

Of course, it is less clear whether the treatment people receive from personal encounters with police is as consistent as the taxation example.

References

Ball, G. A., Klebe-Trevino, L., & Sims, H. P. (1994). Just and unjust punishment: Influences on subordinate performance and citizenship. Academy of Management Journal, 37(2), 299–322.

Bies, R., Martin, C., & Brockner, J. (1993). Just laid off, but still a “good citizen”: Only if the process is fair. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 6, 227–248.

Braithwaite, J., & Makkai, T. (1994). Trust and compliance. Policing and Society, 4, 1–12.

Braithwaite, V. (1987). The scale of emotional arousability: Bridging the gap between the neuroticism construct and its measurement. Psychological Medicine, 17, 217–225.

Brockner, J., Heuer, L., Siegel, P. A., Wiesenfeld, B., Martin, C., Grover, S., et al. (1998). The moderating effect of self-esteem in reaction to voice: Converging evidence from five studies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75, 394–407.

Brockner, J., & Wiesenfeld, B. M. (1996). An integrative framework for explaining reactions to decisions: Interactive effects of outcomes and procedures. Psychological Bulletin, 120, 189–208.

Brown, D. J., & Lord, R. G. (1999). The utility of experimental research in the study of transformational/charismatic leadership. Leadership Quarterly, 10, 531–539.

Buss, A., & Plomin, R. (1984). Temperament: Early developing personality traits. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Chebat, J. C., & Slusarczyk, W. (2005). How emotions mediate the effect of perceived justice on loyalty in service recovery situations: An empirical study. Journal of Business Research, 58, 664–673.

Cropanzano, R., & Folger, R. (1989). Referent cognitions and task decision autonomy: Beyond equity theory. Journal of Applied Psychology, 74(2), 293–299.

De Cremer, D., & Van den Bos, K. (2007). Justice and feelings: Toward a new era in justice research. Social Justice Research, 20, 1–9.

Diener, E., Larsen, R. J., Levine, S., & Emmons, R. A. (1985). Intensity and frequency: Dimensions underlying positive and negative effect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 48, 1253–1265.

Dillman, D. A. (1978). Mail and telephone surveys: The total design method. New York: John Wiley.

Greenhalgh, L., & Chapman, D. I. (1995). Joint decision making: The inseparability of relationships and negotiation. In R. M. Kramer & D. M. Messick (Eds.), Negotiation as a social process: New trends in theory and research (pp. 166–185). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Haidt, J. (2001). The emotional dog and its rational tail: A social institutionist approach to moral judgment. Psychological Review, 108, 814–834.

Hegtvedt, K. A., & Killian, C. (1999). Fairness and emotions: Reactions to the process and outcomes of negotiations. Social Forces, 78(1), 269–303.

Krehbiel, P. J., & Cropanzano, R. (2000). Procedural justice, outcome favorability and emotion. Social Justice Research, 13, 339–360.

Larsen, R. J., & Diener, E. (1987). Affect intensity as an individual difference characteristic: A review. Journal of Research in Personality, 21, 1–39.

Larsen, R. J., Diener, E., & Cropanzano, R. S. (1987). Cognitive operations associated with individual differences in affect intensity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53, 767–774.

Larsen, R. J., Diener, E., & Emmons, R. (1986). Affect intensity and reactions to daily life events. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 803–814.

Lind, E. A., Greenberg, J., Scott, K. S., & Welchans, T. D. (2000). The winding road from employee to complainant: Situational and psychological determinants of wrongful termination claims. Administrative Science Quarterly, 45, 557–590.

Lind, E. A., Kulik, C. T., Ambrose, M., & a Park, M. (1993). Individual and corporate dispute resolution: Using procedural fairness as a decision heuristic. Administrative Science Quarterly, 38, 224–251.

Lind, E., & Tyler, T. (1988). The social psychology of procedural justice. New York: Plenum.

Makkai, T., & Braithwaite, J. (1994). The dialectics of corporate deterrence. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 31, 347–373.

Maxfield, M. G., & Babbie, E. (2008). Research methods for criminal justice and criminology (5th ed.). Belmont, CA: Thomson Wadsworth.

McClelland, G. H., & Judd, C. M. (1993). Statistical difficulties of detecting interactions and moderator effects. Psychological Bulletin, 114, 376–390.

Mikula, G., Scherer, K. R., & Athenstaedt, U. (1998). The role of injustice in the elicitation of differential emotional reactions. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 24, 769–783.

Mischel, W. (1973). Toward a cognitive social learning reconceptualization of personality. Psychological Review, 80, 252–283.

Murphy, K. (2003). Procedural justice and tax compliance. Australian Journal of Social Issues, 38, 379–408.

Murphy, K. (2004a). The role of trust in nurturing compliance: A study of accused tax avoiders. Law and Human Behavior, 28(2), 187–209.

Murphy, K. (2004b). Procedural justice, emotions, and resistance to authority: An empirical study. Paper presented at the International Institute for the Sociology of Law’s: Emotions, Crime and Justice Conference, Onati, Spain, 13–14 September 2004.

Murphy, K. (2005). Regulating more effectively: The relationship between procedural justice, legitimacy and tax non-compliance. Journal of Law and Society, 32(4), 562–589.

Murphy, K., & Harris, N. (2007). Shaming, shame and recidivism: A test of reintegrative shaming theory in the white collar crime context. British Journal of Criminology, 47, 900–917.

Murphy, K., & Tyler, T. R. (2008). Procedural justice and compliance behavior: The mediating role of emotions. European Journal of Social Psychology, 38, 652–668.

Murphy-Berman, V., Cross, T., & Fondacaro, M. (1999). Fairness and health care decision making: Testing the group value model of procedural justice. Social Justice Research, 12(2), 117–129.

Rhoades, J. A., Arnold, J., & Jay, C. (2001). The role of affective traits and affective states in disputants’ motivation and behavior during episodes of organizational conflict. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 22, 329–345.

Scheff, T., & Retzinger, S. (1991). Emotions and violence: Shame and rage in destructive conflicts. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books.

Shoda, Y., & Mischel, W. (1993). Cognitive social approach to dispositional inferences: What if the perceiver is a cognitive social theorist? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 19, 574–586.

Sunshine, J., & Tyler, T. R. (2003). The role of procedural justice and legitimacy in shaping public support for policing. Law and Society Review, 37(3), 513–547.

Thornberry, T. P., & Krohn, M. D. (2000). The self-report method for measuring delinquency and crime. In D. Duffee (Ed.), Measurement and analysis of crime and justice: criminal justice 2000 (Vol. 4). Washington, DC: US Department of Justice.

Tyler, T. R. (1989). The psychology of procedural justice: A test of the group-value model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 830–838.

Tyler, T. R. (1990). Why people obey the law. New Haven, CT: Yale University.

Tyler, T. R. (2006). Why people obey the law. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Tyler, T. R., & Blader, S. (2003). Procedural justice, social identity, and cooperative behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 7, 349–361.

Tyler, T. R., & Huo, Y. J. (2002). Trust in the Law: Encouraging public cooperation with the police and courts. New York: Russell Sage.

Tyler, T. R., & Lind, E. (1992). A relational model of authority in groups. In M. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (pp. 115–191). New York: Academic Press.

Van den Bos, K. (2003). On the subjective quality of social justice: The role of affect as information in the psychology of justice judgments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85, 482–498.

Van den Bos, K., Maas, M., Waldring, I. E., & Semin, G. R. (2003). Toward understanding the psychology of reactions to perceived fairness: The role of affect intensity. Social Justice Research, 16(2), 151–168.

VanYperen, N. W., Hagedoorn, M., Zweers, M., & Postma, S. (2000). Injustice and employees’ destructive responses: The mediating role of state negative affect. Social Justice Research, 13(3), 291–312.

Vermunt, R., Blaauw, E., van Knippenberg, D., & van Knippenberg, B. (2001). Self-esteem and outcome fairness: Differential importance of procedural and outcome considerations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 621–628.

Weiss, H. M., Suckow, K., & Cropanzano, R. (1999). Effects of justice conditions on discrete emotions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 84, 786–794.

Wenzel, M. (2002a). The impact of outcome orientation and justice concerns on tax compliance: The role of taxpayers’ identity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 629–645.

Wenzel, M. (2002b). Principles of procedural fairness in reminder letters: A field-experiment. Centre for Tax System Integrity Working Paper No. 42. Canberra: The Australian National University.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the following three grants from the Australian Research Council: DP0666337; DP0987792; LP0346987.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix

Contained in the Appendix is a complete list of the measures used in the analyses of this article. Items are listed in order of Study. It also details the original scale formats, and the recoding of data if applicable (reverse scoring indicated with the letter r).

Study 1—Taxation Context

Procedural Justice

Items measured on a 1 = ‘strongly disagree’ to 5 = ‘strongly agree’ scale.

Below are a number of general statements that describe the way people may see the ATO. Circle the number closest to your view:

-

The ATO gives equal consideration to the views of all Australians.

-

The ATO respects the individual’s rights as a citizen.

-

The ATO considers the concerns of average citizens when making decisions.

-

The ATO is concerned about protecting the average citizen’s rights.

-

The ATO cares about the position of taxpayers.

-

The ATO tries to be fair when making their decisions.

-

The ATO gets the kind of information it needs to make informed decisions.

-

The ATO is generally honest in the way it deals with people.

Affect Intensity

Items measured on a 1 = ‘this is very unlike me’ to 5 = ‘this is very like me’ scale.