Abstract

Inequality of Opportunity (IO) refers to that inequality stemming from factors, called circumstances, beyond the scope of individual responsibility, such as gender, race, place of birth or socioeconomic background. In general, circumstances do not directly convert into future individual’s income. Indeed, different circumstances in childhood lead to different levels of education and different occupational categories which, in turn, contribute to generate divergent levels of income during adulthood. Using the Intergenerational Transmission modules in 2005 and 2011 from the EU-SILC, we estimate the importance of attained education and occupational category as mediating channels in the generation of IO in 26 European countries. We find that the attained level of education channels up to 30% of total IO, with important differences across Europe. Once attained education is taken into account, occupation explains less than 5% of IO in most countries. Moreover, the importance of education as a channel for IO is negatively correlated both with the share of the population that attains tertiary levels of education and with the importance of government expenditure in education relative to GDP.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

There seems to be a social and academic consensus in considering inequality caused by initial socioeconomic factors as unfair, for it is thought to be out of the responsibility sphere of the individual (Rawls 1971; Sen 1980). In line with this perception, and led by the pioneering interdisciplinary work of Roemer (1993), economists have started in the last two decades to shift the focus from overall inequality to the so-called ‘inequality of opportunity’ (IO), trying precisely to measure the extent of that ‘unfair’ inequality.

Equality of opportunity demands that individual characteristics or ‘circumstances’, upon which the individual has no control (such as race, gender or place of birth) do not have any influence on the outcome (income, wealth or health) obtained by the individual (Fleurbaey 2008). Otherwise, there could be a case for public intervention in order to ‘level the playing field’ (Roemer et al. 2003).Footnote 1 However, as it is emphasised in this paper, the relation between circumstances and outcome is not direct, and there exist channels through which individual circumstances may affect the outcome of interest. Identifying these channels and measuring their relative importance is thus crucial for the design of policies targeted to equalise opportunities.

Up to date, the majority of the literature on IO has focused on the theoretical measurement of IO and the empirical comparison across countries and regions.Footnote 2 Some studies have also analyzed the importance of circumstances on IO. Thus, Ferreira and Gignoux (2011) calculated the circumstance-specific opportunity shares of inequality, Björklund et al. (2012), Jusot et al. (2013) dealt with the correlation between circumstances and effort, while Marrero and Rodríguez (2011) and Deutsch et al. (2017) used the Shapley decomposition to disentangle the impact of circumstances on income and health inequality, respectively. Nevertheless, as far as we are aware, there is no proposal in the literature to measure the channels of transmission of IO, which are factors quite distinct from circumstances. Circumstances are personal traits over which individuals have absolutely no control (race, gender, parental education and occupation, etc.), while channels of transmission are those variables partly under the individual responsibility, but through which IO affects the individual’s final outcomes, such as the individual level of attained education, the quality of the education received, the occupational category, the functioning of the labor market, the influence of social or educational peers, etc.

The question is to what extent these channels connect circumstances and outcome. This paper attempts to cover a relevant gap in the literature proposing a method and estimating the importance of alternative potential mediating channels in the generation of IO. We work with the two most prominent channels, namely, attained education and occupational category. Thus, we propose an approach that decomposes IO into its alternative drivers: the part of IO channeled by individual education, the part conducted by occupational status (once controlled by education), and a residual component which includes any other unobserved channel.

Attained education is a natural candidate for studying the channels of IO. On the one hand, education has widely been recognised as a key element in the economic production function (Becker 1964; Lucas 1988) and in the acquisition and distribution of earnings (Psacharopoulos 1994; Card 1999; Trostel et al. 2002; Lemieux 2006). On the other hand, the educational level of the individual is not completely due to her own responsibility, as parental background has been found to play an important role (Gamboa and Waltenberg 2012; Ferreira and Gignoux 2014), and education is known to also mediate a relevant share of the intergenerational income persistence (Eide and Showalter 1999; Chetty et al. 2014 and Palomino et al. 2017).

The connection between education and circumstances has also appeared in the literature studying the role of education as a source of upward social mobility or ‘fluidity’ (i.e. Breen and Karlson 2013 or Bukodi and Goldthorpe 2016, among many others). This literature tends to discuss the role of education in social mobility in terms of what is called the ‘OED triangle’, that is, the triangle of associations between Origins (i.e., circumstances in our case), Education, and Destinations (i.e., final allocation). Education expansion creates better educational opportunities, which weaken the origin—education association, and at the same time strengthens the education—destination association because the selection in the labour market turns more meritocratic (i.e., education qualification becomes more relevant in the selection process). Both aspects favor upward mobility, and put education as a relevant channel of transmission.Footnote 3

A second and subsequent potential mediator is the occupational category of the individual. Occupation deeply influences the economic achievement of the individual (Sullivan 2010) and, at the same time, may be deeply connected with circumstances like race, gender and family background. Thus, for example, Fuller and Vosko (2008) find that the immigration status, gender, and race significantly influence the chances of having a temporary employment, which is indeed associated with lower rewards, while Pérez-González (2006) observes that the final labor market allocation and the salary are affected by parental connections when looking for a job.

It is then clear that attained education and occupational status are tied to both ends of IO: the initial conditions (circumstances) and the final outcome (income in our case). Different circumstances in childhood lead to different levels of education and different occupational categories, which in turn contribute to generate divergent economic outcomes during adulthood.

However, the analysis of these two possible channels of IO is not straightforward. First, both channels are closely linked, and the education system is expected to strongly condition the final allocation in the labor market. This problem can be tackled if the analysis method follows the natural order of both factors in the life cycle, considering education as a prior mediator and then measuring the channeling role of the occupational category once the educational level has been accounted for.Footnote 4 A second difficulty that arises in the measurement of these channels is that some relevant educational and occupational aspects are subtle and, therefore, hard to measure. In this respect, school quality, classmates, job connections and access to social networks are elements that stand out. Still, the absence of a complete set of education and occupation variables should make us conscious of the impossibility of measuring their full channeling role—as we will discuss in the results—but it should not prevent us from attempting the analysis.

We exploit the data from the special module on Intergenerational Transmission of Disadvantages contained in the EU-SILC framework in 2011, referring to data from 2010, and we estimate the importance of attained education and occupational category as mediating channels in the generation of IO in 26 European countries.Footnote 5 Individual income is measured as the ‘equivalent household income’, attained education includes the individual level of education attained, and occupational status is measured as the occupational category (details described in Sect. 3). The set of circumstances considered follows Marrero and Rodríguez (2012), and includes parental level of education attained by both father and mother, father’s occupational category (mother’s occupation is not collected in several countries and we drop it), gender, inmigration status and the perceived financial struggle in the household when the respondent was about 14 years old.

Despite that only the level of attained education is used to analyse the role of the education system (there is no information on school quality or school socioeconomic status in EU-SILC), we find education to be a relevant channel of IO, mediating 15% of IO or more in ten European countries (more than 30% of IO in Portugal and Luxembourg). There is not a clear geographical pattern, and the range of the educational channel of IO in Central Europe goes from 8.4% (Germany) to 31.0% (Luxembourg), while it ranges from 7.9% (Estonia) to 24.0% (Hungary) in Eastern Europe.

We do find, however, that the importance of education as a channel for IO is significantly and negatively correlated with the share of the population that attains tertiary levels of education and with the government expenditure in education as a share of GDP. That suggests that, in countries where a greater part of the population can access higher levels of education and the government devoted a higher fraction of resources to education, the connection between background circumstances, levels of education and adult income is weaker.

Our results also indicate that the level of education conditions most of the possible influence of the occupational category, for once the education channel has been discounted, the influence of the occupational channel is associated with only between 1 and 5% of IO in most countries.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows. In Sect. 2, we present the methodology to estimate the channels of IO. Section 3 details our choices and treatment of the EU-SILC database and comments on the results of our primary regressions. Section 4 presents our estimates for IO across Europe, while Sect. 5 displays our findings for the educational and occupational channels. Finally, Sect. 6 concludes.

2 Methodology

The method that we propose to decompose IO by channels of transmission is based on the orthogonality property of OLS. Hence, to be consistent with this proposal, we adopt the ex-ante parametric approach in Ferreira and Gignoux (2011) to measure IO.Footnote 6

The income \(y_{i}\) of the individual \(i \in \{1,\ldots ,N\}\) is assumed to be a function of her effort \(e_i\) and her set of circumstances \(C_i\). Circumstances are assumed to be exogenous by definition, while effort is likely to be influenced, among other factors, by personal circumstances. Accordingly, individual income can be written as \(y_i = f(C_i, e_i(C_i))\). The population is then partitioned into T mutually exclusive and exhaustive types denoted by \(\epsilon = {J_1,\ldots ,J_T}\), where all individuals of a given type t share the same circumstances. Then, within each type, and assuming all circumstances have been accounted for, only effort \(e_i\) would determine the income of each individual i.

Equality of opportunity is achieved when the individual’s income is independent of her circumstances. Strictly speaking, this would demand that the following condition holds true:

where \(F^t(y)\) denotes the income distribution for individuals of type t. In this case, no set of circumstances offers a better opportunity set of incomes than any other. On the contrary, if one distribution dominates the other, this would offer unambiguous evidence against equality of opportunity. Unfortunately, distributions can be significantly different and yet cross each other, in which case it is unclear whether one type is better off than the other. To break potential ties, a practical alternative is to focus on a specific moment of each distribution, such as the mean income.

Among all the possible inequality indices that fulfil the basic principles found in the literature on inequality, only those of the Generalised Entropy class are additively decomposable into a between-group and a within-group component (Bourguignon 1979; Shorrocks 1980).Footnote 7 We use the (MLD) because it belongs to the Generalised Entropy class, has a path-independent decomposition (Foster and Shneyerov 2000), and uses weights based on the groups’ population shares. For an income distribution y, with mean \(\overline{y}\), the MLD is defined as:

The MLD can be decomposed as follows:

where \(p_t\) is the population share of each group t, and \(\overline{y}_t\) is the mean value for each group t. The first term of Eq. (3) represents inequality between groups of the population (types) while the second component represents inequality within those groups. Note that the ‘between’ component of inequality can be interpreted as the inequality of a ‘smoothed distribution’ in which all individuals from each group t (sharing the same circumstances) receive the same income \(y_{i}^{t} = y_{i} \mid C_{i}^{t}\), while the within component would represent the inequality of a ‘standardised distribution’ in which all differences across groups have been eliminated and only differences within groups remain (Checchi and Peragine 2010; Ferreira and Gignoux 2011).

The ‘smoothed’ and ‘standardised’ income distributions can be estimated parametrically and non-parametrically, but for the reasons mentioned above we focus on the first approach.Footnote 8 Assuming a log-linear relationship between circumstances and income we estimate the following equation:

The estimated OLS coefficients in the vector \(\hat{\psi }\) are then used to obtain the ‘smoothed income distribution’ in which all individuals belonging to the same type are assigned the same income \(\tilde{\mu }_{i} = \exp [\hat{\psi }^{\top }C_i]\). Then, IO—inequality between types—is computed by applying \(I_{MLD}\) to the ‘smoothed distribution’, \(IO = I_{MLD}(\tilde{\mu })\).

Likewise, the within component is obtained by assigning to all individuals the same average level of the conditioning variables \(\overline{C}\), plus the individual variability not captured by circumstances, \(\tilde{\phi }_{i} = \exp [\hat{\psi }^{T}\overline{C} + \hat{\varepsilon }_{i}]\), where \({\hat{\varepsilon }}_{i} = \ln {y_{i}} - \hat{\psi }^{\top }C_{i}\). Inequality in this distribution (residual inequality) can be expressed as \(RI = I_{MLD} (\tilde{\phi })\), and represents the inequality not explained by the observed set of circumstances.Footnote 9

Finally, using the properties of the MLD index, overall inequality, I, can then be decomposed as:

2.1 The Channels of Transmission

Circumstances do not directly convert into future income or any other considered outcome. There exist observed intermediate variables, like the education or the job category attained by the individual, which are influenced by circumstances and that, in turn, affect individual incomes.

From the calculation of IO, we know that the smoothed distribution \(\tilde{\mu }_{i}\) represents the part of total income for individual i that is explained by her \(C_i\) set of observed circumstances, \(y{_i}^{C}\), and we notate \(\tilde{\mu }_{i} = y{_i}^{C}\). We then postulate that this component is a function of a set of observed intermediate variables \(Z_{i}\), which are the channels of transmission:

The term \(\nu _{i}\) represents unobserved (or not included) mediating variables and a random component of individual income.Footnote 10

We consider the level of attained education as our first channel, i.e., \(Z_i=E_i\) and we assume a log-linear form for Eq. (6):

The OLS estimated coefficients of this regression can be used to obtain an ‘over-smoothed income distribution’ in which all individuals sharing the same level of attained education would get the same circumstance conditional income, i.e., \(y_{i}^{C,{\,}EDU} = exp [\hat{\eta }E_{i}]\). Then, \(y_{i}^{C,{\,}EDU}\) represents the part of the circumstance-conditoned income that is associated with the individual level of education, and thus the MLD of this ‘over-smoothed’ distribution gives us the IO channelled through the attained education, \(IO_{EDU}=I_{MLD}({y}^{C,{\,}EDU})\). Analogously, the MLD of the unexplained part \({\nu }_{i}\) can be interpreted as the part of IO not explained by the individual attained education, \(I_{MLD} y_{i}^{C,{\,} \overline{EDU}} = I_{MLD}(exp{[\hat{\nu }_{i}}])\).Footnote 11

Thus, we achieve the following decomposition of inequality of opportunity:

However, the educational level is not the only possible channel of IO. The component of \(y{_i}^{C}\) not channelled by education, denoted by \(y_{i}^{C,{\,} \overline{EDU}}\) could indeed be transmitted by other variables. A reasonable candidate is the occupational category of the individual -also available in our database for Europe. Different occupational categories may be related to circumstances (e.g. parental occupation) and may also be related to different salaries or economic advantages. As discussed in the introduction, the fact that the attained educational level temporarily precedes the occupational category of the individual justifies the order adopted in our decomposition of IO.

Following the same strategy as for E, we can further decompose \(y_{i}^{C, {\,}\overline{EDU}}\) into a component explained by individual occupation and a component due to other factors. Thus, by estimating the following equation,

where \(O_{i}\) represents the occupational category of the individual i, we can obtain the distribution of \(y_{i}^{C}\) predicted by occupation, once the educational channel has been accounted for: \(y_{i}^{C, {\,}OCC/EDU} = \exp {[\hat{\kappa }O_i]}\). The residual \(y_{i}^{C,{\,} OTH} = \exp [{\hat{\xi {_i}}}]\) represents the part of \(y_{i}^{C}\) channelled through variables other than education and occupation.

Accordingly, we decompose the part of IO not channeled by education, \(IO_{\overline{EDU}}\), into a part channeled by individual occupation \(IO_{OCC}\) and another part explained by other channels \(IO_{OTH}\). Thus, we finally obtain a full (and exact) decomposition of IO that considers the attained education and individual occupation channels,

where the relative share of IO mediated by the level of education is \(IO^{S}_{EDU} = \frac{ IO_{EDU}}{IO}\) and the relative share of IO mediated by occupation equals to \(IO^{S}_{OCC} = \frac{ IO_{OCC}}{IO}\).

This sequential decomposition process could continue and be applied to as many channels as we have information about, as long as the decomposition follows the order in which these channels come into play in the life of the individual. Although it requires the use of the decomposable MLD index, our method achieves a complete decomposition of IO in the considered channels and the residual ‘unchannelled’ IO. Finally, the method proposed here can be also applied to the ex-post method as shown in the "Appendix".

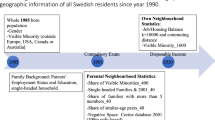

3 Database and Primary Regressions

We use data from the European Statistics of Income and Living Conditions database (EU-SILC), which encompasses homogeneous surveys on living conditions implemented by the national institutes of statistics under the coordination of Eurostat. In its 2011 wave, the living conditions survey included an additional questionnaire aimed to gather information about the economic and social background of the respondents. Thus, the “Intergenerational Transmission of Disadvantages” module in 2011 includes questions about parental education and occupation, and about the financial situation of the household during the respondents’ childhood.Footnote 12 These items upon which the individual has no control are circumstances, which make them suitable for an IO analysis (Roemer 1998). In addition, data collected in the main EU-SILC questionnaire contain information on a wide range of items, including income (our outcome of interest), education and occupation of all individuals in each household, which we consider as possible channels of IO.

Our particular set of circumstances, which is very similar to the one used in Marrero and Rodríguez (2012), comprises the highest level of parental education attained from both father and mother, father’s occupational category (mother’s occupation is missing in several countries, and we dropped it from the set of circumstances) and the perceived financial struggle in the household when the respondent was about 14 years old. The educational level is categorised in four categories: ‘No education’, ‘Low education’ (International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) levels 0, 1 and 2), ‘Middle Education’ (ISCED levels 3 and 4) and ‘High Education’ (ISCED levels 5 and 6). The occupation of the father corresponds to the broad one-digit groups from the International Standard Classification of Occupation (ISCO-88).Footnote 13

The 2011 module included two questions referring to the financial strains perceived by the respondent during childhood, addressing the difficulty to ‘make ends meet’ and the ‘financial situation of the household’. For comparability reasons with the 2005 module we chose to include only the latter question and also recoded the answers in five categories instead of six like in the 2005 questionnaire.Footnote 14 Finally, we complete our set of circumstances with two other individual variables from the main survey questionnaire: gender of the individual and the country of birth (local, from another EU country or from another country outside the EU).

We use “equivalent disposable household income” as the proxy for the economic advantage of the individual. Our sample is restricted to only household heads, the head being the person of the household with the highest individual labour income.Footnote 15 In order to exclude incomes obtained at the tails of the life-income cycle, and to include cohorts with the highest proportion of employed individuals (Ferreira and Gignoux 2011), only household heads within the 30–50 years of age range are kept. We removed extreme outlier observations of equivalent income.Footnote 16 Descriptive statistics for income and all parental and individual variables in each country and wave are presented in Appendix Table 3.

In general, our descriptive statistics find differences in average equivalent income similar in rank to the ones found in national accounts statistics (i.e. using GDP per capita), with Luxembourg and Norway on top of the list. Nordic and central European countries show higher shares of parents with high levels of education, a pattern that also occurs when we look at the educational level of the respondent. Note also that, in all countries, the share of individuals with high education is greater than the share of parents with high education; the opposite occurs when we look at the shares of the individuals with the lowest educational level. Moreover, Nordic and central countries tend to show higher shares of parents and individuals with professional, managerial or technical occupational categories.Footnote 17

4 Inequality of Opportunity in Europe

Our homogeneous set of circumstances allows for a cross-country comparison of inequality and inequality of opportunity, and we find that our baseline results and ranking of countries for IO are consistent with previous works (Marrero and Rodríguez 2012 for the 2005 wave and Brzezinski 2015 for the 2011 wave). There are only minor differences in the values of particular countries due to different database decisions. Also note that -compared to the previous works on IO for Europe- we add Cyprus, Iceland and Luxembourg to the sample of countries. Standard errors for the inequality indices were calculated by bootstrapping with 1000 replicates.

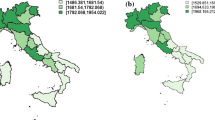

Going from the bottom to the top in the IO ranking (see Table 1 and Fig. 1), Nordic countries are placed at the lower end, although Iceland -which could have been specially affected by the financial crisis- is a ‘Nordic outlier’ in 2011. Among the Central European countries (we include here Ireland and the UK for simplicity), Germany and the Netherlands have lower IO levels (comparable to those of the Nordic countries) while France, Austria and the UK have higher IO ranking positions, just above Slovenia, Slovakia and the Czech Republic. Further up we find a mixed group that includes Belgium, Ireland, Italy and most of the other East European countries (Estonia, Hungary, Poland, Latvia and Lithuania), with Spain and Cyprus having the highest IO in this group; finally, Luxembourg, Greece and Portugal occupy the top of the IO ranking, having the most uneven ‘playing’ field for people with different circumstances, according to our results. If we compare inequality and IO rankings, we can see that the Baltic republics rank better in terms of IO than in terms of sheer inequality, while the opposite occurs for Belgium and, specially, for Luxembourg.

5 The Mediating Role of Education and Occupation

We turn now to the analysis of the educational and occupational channels of IO obtained by applying the method presented in Sect. 2 to our sample of 26 European countries. The last two columns in Table 1 show the percentage of IO associated with individual education and occupation. Relative to total IO, the level of education attained by the individual plays a relevant channeling role, mediating about one third of IO in Portugal and Luxembourg, almost one quarter in Greece and Hungary, and more than 20% in Italy and Poland. Most of the other countries are in the 8–20% range, with the Nordic countries—except Norway—showing the lowest share of IO channelled through education (see Table 1 and Fig. 2). It is interesting to note that the level of education also seems to account for a similar share of the intergenerational income elasticity (IGE). Eide and Showalter (1999) and Palomino et al. (2017) find that controlling for education the value of IGE decreases by around 30% using OLS, while Blanden et al. (2014) find a decrease close to 50%.

Our findings show a relative contribution of individual education to IO smaller than what is found for social class mobility. Breen and Karlson (2013) find a mediating role for the UK around 50% in class mobility for cohorts born between 1925 and 1954, with no significant changes overtime.Footnote 18 Our results are more in line with what Rothstein (2017) finds for income mobility. Building on the estimates of Chetty et al. (2014) across 216 different US commuting zones, he estimates that the different educational skills of the students account for 12% of the variation in IGE.Footnote 19

The other potential candidate to channel IO present in the EU-SILC database is the occupational category of the individual. We find that, once we take into account the educational channel, the share of IO channelled by the occupational category is relatively small in most countries, representing only between 1 and 5% in most countries, and around 8% in Cyprus and Austria (Table 1), although no geographical pattern is observed.

Combined, the occupational category and the educational level explain up to 35% of IO in some countries (Portugal and Luxembourg). Although it represents an important share -and could explain part of the unfortunate lead that Portugal, Greece and Luxembourg have in the IO levels- we must acknowledge that there is still an important part of IO not associated with either of these two factors. According to our estimates, in most countries more than 70% of IO is mediated by unobserved factors other than the educational level and educational category. As pointed out by other studies, school quality, peer effects or parental connections could be some of the most relevant mediators channeling that part of IO still unexplained by our limited set of variables. In that line, Chetty et al. (2014) find, for example, that rank intergenerational mobility is related to the quality of the schools in different geographical areas in the U.S. As richer databases become available, we believe our strategy could be applied to the exploration of other potentially important mediators.

5.1 The Educational IO Channel and the Expansion of Higher Education

The measured educational channel raises a further question: which features of the educational system are associated with the role of education in the transmission of opportunities? A straightforward candidate can be found in the average levels of education attained at each country. We perform a descriptive cross-correlation analysis, comparing the access to different levels of education of the population and the channelling role of education (Table 2). Figure 3 shows that EU countries with a larger share of population attaining higher (tertiary) education tend to have a more limited share of IO mediated by the educational channel. The correlation turns positive when we consider the percentage of the population attaining only the lowest levels of education (Fig. 4).

We also find a significant negative correlation between the mediating role of education in IO and the government expenditure in education in the previous years as a share of GDP (Table 2). Data for government expenditure in education as a share of GDP have been obtained from the UNESCO database (http://data.uis.unesco.org/) and have been averaged over the years 1999–2009. The association occurs both when we consider overall expenditure in all levels of education (Fig. 5) and specific expenditure in tertiary education (Fig. 6). It appears that when more public resources are devoted to education, the educational level loses importance as a connection between circumstances and income; the playing field is now more equal for all.

Indirectly, the IO channelling role of education might shed some light on the ongoing debate about the effect of educational investment on economic growth. This effect has traditionally been attributed to direct increases in skills (and productivity) and to positive social externalities of education (Angrist and Krueger 1991; Card 1999 or Krueger and Lindahl 2001). Since IO has recently been found to be negative for growth (Marrero and Rodríguez 2013, 2017; Bradbury and Triest 2016; Teyssier 2017), our results add a third possible connection between education and growth, the one that takes place via a decrease in IO. However, we leave the exploration of this avenue for future research.

6 Concluding Remarks

In this paper we aim to disentangle the channels through which different circumstances convert into different outcomes. We present a method to decompose ex-ante inequality of opportunity into its educational and occupational channels. This method can also be applied to the ex-post approach, and to other potential transmission channels (e.g. education quality or work connections) if appropriate data were available.

Our proposed method computes circumstance-conditioned income (the ‘smoothed’ income distribution) and successively decomposes it into orthogonal mediating components, following the natural order in which these mediators come into play: first attained education and then occupational category. Then, by using the decomposable MLD index, total inequality of the smoothed distribution is partitioned into different shares of IO explained by the considered channels.

Applying this methodology to data from 26 European countries, we find four prime results. First, a relevant share of IO is channelled through the different levels of attained education. This share accounts to one third of IO in Portugal and Luxembourg, almost one fourth in Greece and Hungary, and more than one fifth in Italy and Poland. Second, once the educational channel is taken into account, the importance of the occupational channel is reduced, channelling less than 5% of IO in most European countries. Third, although particular countries suffered significant changes over time, no general pattern of change in the shares of IO channelled by education and occupation was found. Four, there is a negative correlation between the IO share channelled by education and the share of the population with higher education. This suggests that if more people achieve higher education levels, the IO share channelled through attained education decreases. Moreover, we find a negative correlation between government expenditure in education and the mediating role of the educational level in IO, which points to the key role of public investment in providing opportunities.

These findings are relevant to practitioners and policymakers for two main reasons. On the one hand, we provide some empirical evidence of what before was only an intuition, i.e., that a significant share of IO derives from the different levels of education achieved by individuals from different backgrounds. Our results indicate that income acquisition opportunities are more effectively equalised by facilitating access to the educational system to those individuals with bad circumstances, than by improving the functioning of the labour market. On the other hand, the important share of IO still unexplained by our two observed channels indicates that other channels such as quality of education, classroom peers, job connections or social networks are worth exploring. We believe that our method provides a useful tool for future analysis of these potential channels.

Notes

As we discuss in the results section, using income instead of social class as the socioeconomic ‘destination’ variable seems to find a relevant but somewhat smaller role of education mediating the O-D connection.

Note that a particular education decision could be partly dependent on a current occupation, which allows the individual to afford that education, for example. But the subsequent final occupation achieved—and the eventual income generated—will be conditioned to the educational level previously acquired.

As a robustness check, we also carry out the analysis using the Intergenerational Transmission of Poverty module from EU-SILC 2005, finding that our main results are comparable, and that there is no clear trend of change in the mediating role of education or occupation between the two waves analyzed.

The broadly used Gini coefficient is not additively decomposable. In the case that type income ranges overlap, which occurs in our case, this measure is decomposable in three terms: a between-group component, a within-group component and a residual. The problem here is how to assign the last term to the between-group and within-group components.

Additionally, the parametric approach allows us to take full advantage of the high number of circumstances in the EU-SILC database, since non-parametric estimates are inaccurate when observations in some of the types are scarce.

Note that \(\tilde{\phi }^{i} = \exp [\hat{\psi }^{\top }\overline{C} + \hat{\varepsilon }_{i}]\) is equivalent to: \(\exp [\hat{\psi }^{\top }\overline{C}] \cdot \exp [\hat{\varepsilon }_{i}]\). Applying MLD to this last expression, and given that \(\exp [\hat{\psi }^{\top }\overline{C}]\) is constant, it is true—recall that the MLD index is scale invariant—that \(I_{MLD}(\tilde{\phi }) = I_{MLD}(\exp {[\hat{\varepsilon }_{i}}])\). Thus, in a parametric framework using the MLD inequality measure, the within inequality component boils down to the MLD of the distribution of the residual term from the parametric regression.

Analogously, it could be argued that effort, or at least part of it, is transformed into income through a set of mediating factors H. Thus, we could express the component of income not explained by observed circumstances (from Eq. 4) as \(y^{\overline{C}}_{i} = \exp {[\varepsilon _{i}]} = f(H_{i}, \Omega _{i})\), where \(H_{i}\) collects observed mediators between effort and income, and \(\Omega _{i}\) includes the effect on income of unobserved mediators and a random component. Unfortunately, \(\varepsilon _{i}\) includes the effect of not only effort but also unobserved circumstances. We are then unable to isolate the effect of effort, unless effort variables are explicitly considered in Eq. (4).

Note that this expression is precisely equivalent to a standardised distribution obtained by applying \(\hat{\eta }\) to a constant average level of attained education \(\overline{E}\) and adding the residual term. Because both distributions differ only in a change of scale, it is true that \(I_{MLD} y_{i}^{C, \overline{EDU}} = I_{MLD}(\exp {[\hat{\eta }\overline{E} + \hat{\nu }_{i}]}) = I_{MLD}(\exp {[\hat{\nu }_{i}}])\). Hence, \(I_{MLD} y_{i}^{C,{\,} \overline{EDU}}\) can be interpreted as the part of IO not explained by individual differences in the education level.

For the sake of robustness, we also use the analogous “Intergenerational Transmission of Poverty” module from the EU-SILC 2005 wave. See Online Appendix.

Categories include: managerial, professional, technician, clerical, sales, skilled agricultural, craft trade, machine operation, elementary occupation and armed/military occupation. Note that we have also included ‘unemployed’ as occupational category for those individuals who were unemployed, not disabled to work nor retired, and for which the occupational category was not coded.

See Online Appendix for more details on the choices made to make the data from both waves homogeneous.

The equivalence scale used by Eurostat is \(1 + 0.5 * (HM_{14} -1) + 0.3 * HM_{13}\), where \(HM_{14}\) refers to the individuals in the house who are fourteen or older, while \(HM_{13}\) refers to the individuals in the house who are thirteen or younger. Although we considered using individual labour income as the proxy variable for the economic advantage—and not just to determine the household head—we found impossible to obtain that variable homogeneously among countries —some countries provide only gross income while others provide only the net measure—and therefore discarded that option. Again for the sake of comparability, income from 2010 (2011 wave) has been converted to 2004 (2005 wave) terms using the Harmonised Consumer Price Index published by Eurostat. Note that in the EU-SILC waves respondents report data from the previous year.

We calculated the adjusted box-plot for each country and wave, accounting for skewness and using the parameter 3 to exclude observations placed more than three quartiles below or above the adjusted interquartile range (see Hubert and Vandervieren 2008).

The coefficients from regressing income on circumstances for each country and wave in order to obtain the \(y{_i}^{C}\) ‘smoothed distribution’ (Eq. 4) are available in the Online Appendix. This Appendix also displays the estimated coefficients in the IO channels regressions for each educational level and each occupational category of the individual (for all countries in both waves) and the descriptive statistics for the 2005 wave.

Recall that our result for the UK in 2011 (individuals born between 1950 and 1980) is that education mediates around 10% of inequality of opportunity.

The discrepancy in the mediating role of individual education in class versus income mobility surely deserves further research. Possible explanations could lie in the relatively low contribution of education inequality to income inequality (about 20% in the U.S. according to Breen and Chung 2015), the different return to skills that individuals obtain (Rothstein 2017), or the increase in between-firms inequality in workers income (Song et al. 2015)

Note that, in the absence of any objective measure of effort (as it is usually the case) estimates are obtained under the assumption that all individuals in the same income quantile at different types belong to the same tranche and thus exert the same level of effort.

References

Angrist, J. D., & Krueger, A. B. (1991). Does compulsory school attendance affect schooling and earnings? Quarterly Journal of Economics, 106(4), 979–1014.

Becker, G. S. (1964). Human capital: A theoretical and empirical analysis, with special reference to education (2009th ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Björklund, A., Jäntti, M., & Roemer, J. E. (2012). Equality of opportunity and the distribution of long-run income in Sweden. Social Choice and Welfare, 39(2), 675–696.

Blanden, J., Haveman, R., Smeeding, T., & Wilson, K. (2014). Intergenerational mobility in the United States and Great Britain: A comparative study of parent–child pathways. Review of Income and Wealth, 60(3), 425–449.

Bourguignon, F. (1979). Decomposable income inequality measures. Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society, 47(4), 901–920.

Bradbury, K., & Triest, R. K. (2016). Inequality of opportunity and aggregate economic performance. RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences, 2(2), 178–201.

Breen, R., & Chung, I. (2015). Income inequality and education. Sociological. Science, 2, 454–477.

Breen, R., & Karlson, K. B. (2013). Education and social mobility: New analytical approaches. European Sociological Review, 30(1), 107–118.

Brunori, P., Peragine, V., & Serlenga, L. (2016). Upward and downward bias when measuring inequality of opportunity. ECINEQ WP 2016-406.

Brzezinski, M. (2015). Inequality of opportunity in Europe before and after the Great Recession. University of Warsaw-working papers, No. 2/2015 (150).

Bukodi, E., & Goldthorpe, J. H. (2016). Educational attainment-relative or absolute-as a mediator of intergenerational class mobility in Britain. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 43, 5–15.

Card, D. (1999). The causal effect of education on earnings. Handbook of Labor Economics, 3, 1801–1863.

Checchi, D., & Peragine, V. (2010). Inequality of opportunity in Italy. The Journal of Economic Inequality, 8(4), 429–450.

Chetty, R., Hendren, N., Kline, P., & Saez, E. (2014). Where is the land of opportunity? The geography of intergenerational mobility in the United States. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 129(4), 1553–1623.

Deutsch, J., Alperin, M. N. P., & Silber, J. (2018). Using the Shapley decomposition to disentangle the impact of circumstances and efforts on health inequality. Social Indicators Research, 138(2), 523–543.

Eide, E. R., & Showalter, M. H. (1999). Factors affecting the transmission of earnings across generations: A quantile regression approach. Journal of Human Resources, 34(1), 253–267.

Ferreira, F. H., & Gignoux, J. (2011). The measurement of inequality of opportunity: Theory and an application to Latin America. Review of Income and Wealth, 57(4), 622–657.

Ferreira, F. H., & Gignoux, J. (2014). The measurement of educational inequality: Achievement and opportunity. The World Bank Economic Review, 28(2), 210–246.

Fleurbaey, M. (2008). Fairness, responsibility, and welfare. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Foster, J. E., & Shneyerov, A. A. (2000). Path independent inequality measures. Journal of Economic Theory, 91(2), 199–222.

Fuller, S., & Vosko, L. F. (2008). Temporary employment and social inequality in Canada: Exploring intersections of gender, race and immigration status. Social Indicators Research, 88(1), 31–50.

Gamboa, L. F., & Waltenberg, F. D. (2012). Inequality of opportunity for educational achievement in Latin America: Evidence from PISA 2006–2009. Economics of Education Review, 31(5), 694–708.

Hubert, M., & Vandervieren, E. (2008). An adjusted boxplot for skewed distributions. Computational Statistics and Data Analysis, 52(12), 5186–5201.

Jusot, F., Tubeuf, S., & Trannoy, A. (2013). Circumstances and efforts: How important is their correlation for the measurement of inequality of opportunity in health? Health Economics, 22(12), 1470–1495.

Krueger, A. B., & Lindahl, M. (2001). Education for growth: Why and for whom? Journal of Economic Literature, 39(4), 1101–1136.

Lefranc, A., Pistolesi, N., & Trannoy, A. (2008). Inequality of opportunities vs. inequality of outcomes: Are western societies all alike? Review of Income and Wealth, 54(4), 513–546.

Lemieux, T. (2006). The “Mincer equation” thirty years after schooling, experience, and earnings. Berlin: Springer.

Li Donni, P., Rodríguez, J. G., & Rosa Dias, P. (2015). Empirical definition of social types in the analysis of inequality of opportunity: A latent classes approach. Social Choice and Welfare, 44(3), 673–701.

Lucas, R. E. (1988). On the mechanics of economic development. Journal of Monetary Economics, 22(1), 3–42.

Marrero, G. A., & Rodríguez, J. G. (2011). Inequality of opportunity in the United States: Trends and decomposition. Inequality of opportunity: Theory and measurement, chapter 9 (pp. 217–246). Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Marrero, G. A., & Rodríguez, J. G. (2012). Inequality of opportunity in Europe. Review of Income and Wealth, 58(4), 597–621.

Marrero, G. A., & Rodríguez, J. G. (2013). Inequality of opportunity and growth. Journal of Development Economics, 104, 107–122.

Marrero, G. A., & Rodríguez, J. G. (2016). Inequality ... of opportunity and economic performance. Chapter in the Special Issue Economic Mobility, edited by the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis and the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (pp. 385–419). https://www.stlouisfed.org/community-development/publications/economic-mobility

Marrero, G. A., Rodríguez, J. G., & Van der Weide, R. (2016). Unequal opportunity, unequal growth. World bank policy research working paper (No.7853).

Palomino, J. C., Marrero, G. A., & Rodríguez, J. G. (2018). One size doesn’t fit all: A quantile analysis of intergenerational income mobility in the US (1980–2010). The Journal of Economic Inequality, 16(3), 347–367. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10888-017-9372-8.

Pérez-González, F. (2006). Inherited control and firm performance. The American Economic Review, 96(5), 1559–1588.

Psacharopoulos, G. (1994). Returns to investment in education: A global update. World Development, 22(9), 1325–1343.

Rawls, J. (1971). A Theory of Justice. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Rodríguez, J. G. (2008). Partial equality-of-opportunity orderings. Social Choice and Welfare, 31(3), 435–456.

Roemer, J. E. (1993). A pragmatic approach to responsibility for the egalitarian planner. Philosophy and Public Affairs, 20, 146–166.

Roemer, J. E. (1998). Equality of opportunity. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Roemer, J. E., Aaberge, R., Colombino, U., Fritzell, J., Jenkins, S. P., Lefranc, A., et al. (2003). To what extent do fiscal regimes equalize opportunities for income acquisition among citizens? Journal of Public Economics, 87(3), 539–565.

Rosa Dias, P. (2009). Inequality of opportunity in health: Evidence from a UK cohort study. Health Economics, 18(9), 1057–1074.

Rothstein, J. (2017). Inequality of educational opportunity? schools as mediators of the intergenerational transmission of income. Washington Center for Equitable Growth, Working papers series.

Sen, A. (1980). Equality of what? In S. McMurrin (Ed.), Tanner lectures on human values (Vol. 1). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Shorrocks, A. F. (1980). The class of additively decomposable inequality measures. Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society, 48(3), 613–625.

Song, J., Price, D. J., Guvenen, F., Bloom, N., & Von Wachter, T. (2015). Firming up inequality. National Bureau of Economic Research: Technical report.

Sullivan, P. (2010). Empirical evidence on occupation and industry specific human capital. Labour Economics, 17(3), 567–580.

Teyssier, G. (2017). Inequality of opportunity: New measurement methodology and impact on growth. Working Paper presented at the 7th ECINEQ Meeting (NYC).

Trostel, P., Walker, I., & Woolley, P. (2002). Estimates of the economic return to schooling for 28 countries. Labour Economics, 9(1), 1–16.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the editor and two anonymous referees, as well as Eduardo Gonzalo-Almorox, Gabriela Sicilia, and the participants at the 34th IARIW conference in Dresden and at the 28th EALE conference in Ghent for valuable comments and suggestions. The authors acknowledge the financial support of the Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad of Spain (Palomino and Rodríguez through project ECO2016-76506-C4-1-R and Marrero through project ECO2016-76818- C3-2-P), from Comunidad de Madrid (Spain) under project S2015/HUM-3416-DEPOPORCM. Marrero also thanks the support provided by the María Rosa Alonso Research Program, financed by the Cabildo Insular de Tenerife (Spain). The authors are also grateful for microdata access provided by the European Commission (Eurostat) through the research project 221/2014-EU-SILC. The usual disclaimer applies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendix I: Decomposing Ex-post IO Channels

Appendix I: Decomposing Ex-post IO Channels

1.1 The Hybrid Ex Post-Ex Ante Method

Our strategy could potentially be applied to the version of the ex-post approach proposed by Checchi and Peragine (2010). This approach partitions the population in p tranches (groups of people belonging to different types but exerting the same level of effort), and then re-scales each tranche distribution in such a way that all tranches have the same mean as the overall distribution (see Checchi and Peragine 2010, p. 436):

where \(y_i^{W}\) is the re-scaled income of individual i belonging to tranche p. \({\overline{Y}}\) and \(\overline{y}^{p}\) are the overall mean and the p tranche mean, respectively. The complete re-scaled distribution \(y^{W}\)thus eliminates all differences between tranches (effort) and retains only differences due to circumstances, which makes it equivalent to our smoothed distribution and \(y^{W} = y^{C}\).Footnote 20

Based on that distribution, the second step of our methodology could be applied, and the role of the channeling variables could be measured just as described in section 2.2. This would formally be a hybrid method in which \(y^{C} = y \mid C\) is estimated ex-post (i.e. assuming that people with the same level of effort belonging to different types should have the same mean income), but the channeling role of the education (or other mediating factors) is estimated ex-ante, ie., assuming groups of people with different levels of education should have the same mean ‘circumstance conditioned income’ and measuring the educational IO channel as the deviation from that assumption.

1.2 The Ex-post Decomposition

Alternatively, the above mentioned ex-post method could be adapted and used again to partition \(y^{W}\) in tranches using the individual education level information. A tranche f would in this case be a group of people having different levels of education but exerting the same level of effort (proxied again by the division in deciles, percentiles, etc.). Each tranche distribution would then be re-scaled again so all tranches have the same overall mean (implying that all effort differences have been equalised and that differences can only be attributed to the different level of education).

where \(y_i^{W-EDU}\) is the re-scaled circumstance condition income \(y{_i}^{C} = y{_i}^{W}\) of individual i belonging to tranche f. \(\overline{Y^{W}}\) and \(\overline{{y^W}}^{f}\) are the overall mean and the f tranche mean, respectively. Thus, the inequality of this twice re-scaled distribution would be the part of IO channelled by education.

If we intend to analyse the channeling role of a second variable once education has been taken into account, we will use the re-scaled distribution \(y^{W}\) that retained only differences due to circumstances, and will transform it in such a way that all types (made according to the levels of the first channel considered) belonging to the same tranche have the same mean. This way we eliminate the differences attributable to the first channel (e.g. education). Secondly, we would proceed to re-scale once again this very new distribution in the way described in the paragraph above, using in this case the new channeling variable (eg. occupation). The inequality of this last distribution would be the component of IO channelled by occupation once education has been accounted for.

See Table 3.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Palomino, J.C., Marrero, G.A. & Rodríguez, J.G. Channels of Inequality of Opportunity: The Role of Education and Occupation in Europe. Soc Indic Res 143, 1045–1074 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-018-2008-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-018-2008-y