Abstract

Previous scholarship has highlighted how work–family conflict (work-to-family conflict and family-to-work conflict) and job insecurity interfere with health outcomes. Little work, however, considers how these stressors jointly influence health among workers. Informed by the stress process model, the current study examines whether job insecurity moderates the relationships between work-to-family conflict and family-to-work conflict and two health outcomes: self-reported physical health and poor mental health. The analyses also consider whether a greater moderating role is played by work-to-family conflict or family-to-work conflict. Using data from the 2008 National Study of the Changing Workforce, we also examine if patterns diverge by gender. Our results show that work-to-family conflict and family-to-work conflict have direct effects on poor mental and physical health. Additionally, we find that the negative effect of work-to-family conflict on poor mental and physical health is stronger for those with job insecurity, while no such relationship was found for family-to-work conflict. We found no evidence of significant gender differences in how these relationships operate. Overall, we contribute to the literature by testing the combined effects of both forms of work–family conflict and job insecurity on poor mental and physical health. We also deepen the understanding of the stress process model by highlighting the salience of the anticipatory stressor of job insecurity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Changes in the organization of work and family life over the past several decades have contributed to the prevalence of work–family conflict—work and family influencing one another in negative ways—among workers in the US (e.g., Schieman et al. 2009; Voydanoff 2007). Work–family conflict has been connected to numerous negative outcomes, ranging from decreased marital satisfaction to reduced organizational commitment (e.g., Hill 2005; Voydanoff 2002, 2007), and the effects of such conflict are pernicious enough to interfere with workers’ mental and physical health (e.g., Allen et al. 2000). These patterns have occurred alongside another shift in US society—an increasingly precarious and unstable economic landscape characterized by widespread job insecurity (Kalleberg 2009). The stress process model emphasizes that stressors often combine to influence individual outcomes (Pearlin 1989; Pearlin and Bierman 2013; Pearlin et al. 1981). We know little, however, about how these two stressors—work–family conflict and job insecurity—combine to shape mental and physical health among the working population. Does job insecurity moderate the relationships between work–family conflict and physical and poor mental health, and do these patterns diverge across gender? We augment existing knowledge about the stress process by bringing together two of the most pressing challenges facing contemporary workers in the US—the tendency of family and work roles to conflict with one another, and pervasive job insecurity across the US economy.

Job insecurity refers to “the overall apprehension of the continuing of one’s job” (Keim et al. 2014, p. 269). It is essentially a subjective perception held by individual workers about the instability of their current jobs (Sverke and Hellgren 2002; Sverke et al. 2002). Although not an objective condition, studies have linked feelings of job insecurity to numerous negative outcomes, such as reduced workplace safety, lower job performance, poorer job attitudes, less job satisfaction, and lower levels of life quality (Cheng and Chan 2008; Gilboa et al. 2008; Jiang and Probst 2015; Moen and Yu 2000; Sverke et al. 2002; Wang et al. 2015). Indeed, studies suggest that job insecurity may be as harmful as objectively experienced conditions including job loss and unemployment (Burgard et al. 2009; Kim and von dem Knesebeck 2015).

Feelings of job insecurity tend to be heightened during times of macro-economic distress (Keim et al. 2014), as in the case of the recent global Great Recession (Burgard and Kalousova 2015). Lasting from 2007 to 2009, it was the worst economic downtown experienced by the US since the Great Depression, resulting in a myriad of far-reaching consequences (Grusky et al. 2011), including persistently high unemployment and marked increases in mortgage foreclosures (Schneider 2015). The recession has officially ended, but the current economic climate continues to be characterized by economic uncertainty, with feelings of job insecurity persisting across the social landscape (Brand 2015; Glavin and Schieman 2014; Kalleberg 2009; Western et al. 2012). U.S. society is also characterized by gender expectations that are interwoven into the work–family interface. It is important to explore whether the outcomes of job insecurity vary by gender, as past research suggests that men may experience job insecurity and job loss as particularly burdensome as breadwinning is so closely tied to masculinity (e.g., Demantas and Myers 2015; Frone et al. 1996; Gaunt 2013).

This widespread economic turmoil has brought renewed scholarly attention to untangling the processes by which larger economic conditions influence a variety of outcomes beyond economic loss, including mental and physical health (Brand 2015; Burgard and Kalousova 2015). We add to the burgeoning literature on health outcomes associated with economic recessions by considering whether job insecurity moderates how work–family conflict relates to physical and poor mental health among working adults in the US. We also investigate whether these effects diverge along gender lines. In doing so, we sharpen the understanding of the stress process (Pearlin 1989; Pearlin and Bierman 2013; Pearlin et al. 1981) by considering how the combination of work-to-family conflict and job insecurity are related to poor mental and physical health. We use data from the 2008 National Study of the Changing Workforce that was collected when the Great Recession was in its beginning years.

1 Theoretical Perspective: The Stress Process Model

Our study is informed by the stress process model, which brings together three facets of stress— “the sources of stress, the mediators of stress, and the manifestations of stressFootnote 1” (Pearlin et al. 1981, p. 337; Pearlin and Bierman 2013). Sources of stress encompass both discrete events and continuous or chronic issues (Pearlin et al. 1981, p. 338). Although past investigations of stress have tended to emphasize discrete events, such as divorce, the stress process model also highlights chronic experiences of stress that unfold across time (Pearlin et al. 1981; Pearlin 1989; Pearlin and Bierman 2013). Indeed, there are multiple sources of stress, or “life strains” that are interwoven into daily life that weigh on individuals as they go about their lives. More recent attention has been called to a “life strain”—anticipatory stressors—in which people who have not experienced a particular stressful event, such as job loss, worry that they may in the future (Pearlin and Bierman 2013). All told, various forms of stress may lead to negative outcomes or manifestations of stress (Pearlin et al. 1981).

The stress process model is also attuned to how the larger social environment shapes exposure to and outcomes associated with stress (Pearlin 1989). The structural arrangements of contemporary U.S. society expose many workers to chronic work–family conflict, while widespread economic precariousness (e.g., Kalleberg 2009) means that the anticipatory stressor of job insecurity may arise, potentially intensifying the already negative effects associated with work–family conflict. Indeed, one central idea of the stress process model is that multiple stressors, experienced simultaneously, can have especially detrimental impacts on the well-being of individuals (Pearlin and Bierman 2013; Pearlin et al. 1981). Lastly, the stress process model also highlights how social statuses, such as gender, can shape people’s experiences of stress, with those occupying more marginal statuses often experiencing intensified impacts of stress (Pearlin and Bierman 2013; Pearlin 1989). Here we consider whether gender is important in understanding how the combined effects of work–family conflict and job insecurity predict physical and poor mental health. In our examinations of the joint roles of work–family and job insecurity, we deepen existing knowledge about the stress process.

2 Work–Family Conflict and Health

Work–family conflict is a broad construct referring to the experiences and responsibilities of one domain creating difficulties in the other domain. This study takes a stress process approach (Pearlin 1989; Pearlin and Bierman 2013; Pearlin et al. 1981), conceptualizing work–family conflict as a chronic stressor or “life strain” faced by many workers. Work–family conflict encompasses two main forms of conflict: work-to-family conflict and family-to-work conflict. Work-to-family conflict takes place when demands and negative moods experienced at work spill over into family life, potentially undermining well-being and social relationships (Burley 1995; Frone et al. 1992a, b; Greenhaus and Beutell 1985; Voydanoff 1988, 2002). For example, consider how a difficult interaction with a coworker leaves a working father emotionally drained; when he returns home, he has little energy to interact with his children. On the other hand, family-to-work conflict occurs when demands or negative moods in the family domain lead to negative experiences at work (Bellavia and Frone 2005; Frone et al. 1992a, b; Schieman and Young 2011). A parent taking time off to care for a sick child and thereby delaying an important work project is one example of family-to-work conflict.

Delineating outcomes associated with work–family conflict has been one of the main objectives of work–family scholarship. In terms of health, work-to-family conflict has been empirically linked to reduced physical health, subjective negative health symptoms, poorer mental health, depression, and psychological distress (Grzywacz and Bass 2003; Hammer et al. 2004; Minnotte et al. 2013a; Schieman and Glavin 2011; van Veldhoven and Beijer 2012). Indeed, one comprehensive review of existing scholarship highlighted consistent and negative relationships between work-to-family conflict on one hand and general well-being and health on the other (Allen et al. 2000). Family-to-work conflict, even though examined less frequently than work-to-family conflict, has also been connected to several health outcomes, including poor physical health, increased depression, and worse mental health (e.g., Amstad et al. 2011; Frone et al. 1996; Grzywacz and Bass 2003). We expect to find similar patterns.

3 Job Insecurity, Work–Family Conflict, and Health

The stress process model also calls attention to anticipatory stressors (Pearlin and Bierman 2013). One anticipatory stressor that is especially important during economic downturns and times of precariousness in the labor market is job insecurity (Keim et al. 2014), as it leads to strain and worries about the future that may heighten the impacts of work–family conflict (Höge et al. 2015). Job insecurity may also increase worries in the family realm, such as those concerning how to take care of family members adequately should one’s job be lost, which may intensify the effects of family-to-work conflict. Worries connected to job insecurity center on both the financial constraints job loss would entail and on the loss of the latent benefits of employment, such as social contacts and social status (Elst et al. 2015). Further, “people experiencing perceived job insecurity cannot employ instrumental strategies of coping because of the persistent uncertainty about whether or not the feared employment instability will actually occur” (Burgard et al. 2009, p. 778). The combination of worry and lack of effective coping mechanisms set the stage for intensifying the effects of work–family conflict on health. As such, previous work emphasizes that job insecurity may result in emotional fallout that negatively shapes one’s family life (Menaghan 1991).

As we have seen, the larger macro-economic context has important consequences for the day-to-day experience of family life (Menaghan 1991). Despite this, the linkages between work–family conflict and job insecurity in shaping outcomes have been subject to little empirical scrutiny, as the work–family and job insecurity literatures remain largely separate from one another (Scherer 2009). Indeed, as detailed by Scherer (2009): “relatively little research has been dedicated to the ‘social consequences’ of insecure employment and its specific implications for work-life reconciliation issues” (p. 527). Although Scherer’s work uses the presence of fixed-term employment contracts as an objective indicator of job insecurity rather than the subjective measures used more frequently in the literature, its findings are relevant to the present study. For example, she found that those working in insecure employment situations tended to have higher levels of time strain than those in secure employment situations. Other research in this area suggests a positive relationship between job insecurity and role conflict, including work-to-family conflict (Cooklin et al. 2015; Keim et al. 2014; Låstad et al. 2015; Lawrence et al. 2013; Richter et al. 2010, 2015). Beyond these studies, scholars have considered job insecurity alongside a long list of other variables conceptualized as job demands or stressors, with little emphasis on the special role played by job insecurity during times of economic uncertainty. Such studies have found positive relationships between job insecurity and work-to-family conflict and family-to-work conflict (e.g., Batt and Valcour 2003; Schieman et al. 2009; Jansen et al. 2003; Voydanoff 2005).

Aside from studies considering work–family conflict, job insecurity itself has also been linked to negative health outcomes. For example, Glavin and Schieman (2014) found that job insecurity reduced the potency of perceived control in decreasing distress. In other words, among those who felt that their jobs were threatened, a sense of personal control was not particularly effective in combating feelings of distress. Other studies have found that job insecurity predicts somatic complaints, poorer self-rated general health, poorer mental health and psychological well-being, psychological distress, and emotional exhaustion (De Witte 1999; Fullerton and Anderson 2013; Glavin 2015; Höge et al. 2015; László et al. 2010; McDonough 2000; Piccoli and De Witte 2015). Further, the results of a meta-analysis confirm the negative relationships between job insecurity and physical and mental health (Sverke et al. 2002). Other studies have compared the subjective indicator of job insecurity to more objective experiences, such as job loss or unemployment. In this vein, the effects of job insecurity on self-rated health and depressive symptoms persisted even when periods of actual job loss or unemployment were taken into account (Burgard et al. 2009), and job insecurity was more strongly related to somatic complaints than unemployment (Kim and von dem Knesebeck 2015). These findings emphasize that job insecurity may be as harmful to health as actual job loss and unemployment.

What we know little about, however, is how job insecurity combines with other types of stressors, to impact health outcomes. The stress process model highlights that individuals often experience multiple stressors simultaneously, thereby deepening negative outcomes (e.g., Pearlin and Bierman 2013). Individuals navigating work and family often face the chronic stressor of work–family conflict, which introduces a number of difficulties that workers must navigate. When dealing with the day-to-day reality of work–family conflict, encountering the anticipatory stressor of job insecurity can make the health impacts of work–family conflict even more severe. For example, consider a worker with young children who has been experiencing high levels of work-to-family conflict and family-to-work conflict on a regular basis. Perhaps the company she works for has been undergoing financial issues, leading to the widespread perception that layoffs are imminent. In addition to dealing with the work–family conflict, she now must deal with the anticipatory stressor of job insecurity, which adds a deeper and overwhelming stress about the future to her list of stressors. In other words, job insecurity isn’t just any additional stressor, it’s a particularly strongly felt anticipatory stressor. She might find worries about losing her job looming large in her mind as she goes about her day-to-day tasks and responsibilities, adding another especially worrisome layer of stress to an already stressful environment. Indeed, prior to her company’s economic difficulties she may have felt that she was barely making it work, struggling to deal with the multiple responsibilities interwoven into her daily life. Together, then, job insecurity and work–family conflict combine to create an especially potent set of stressors that we argue will impact her health more deeply than the direct effects of each merely added together. Job insecurity carries with it worries that extend beyond the day-to-day stressors many of us experience. It has the potential to impact the well-being of a family in concrete and disturbing ways. For example, worries about losing one’s housing or having enough money for basic necessities are particularly disturbing and pressing. Combine that with the chronic stressor of work–family conflict and you have an explosive combination of stressors weighing down on individuals. It is the experience of both work–family conflict and job insecurity together, then, that has the potential to multiply the impacts of such stressors. Based on the stress process model perspective, then, we expect that the experience of job insecurity will deepen the negative impacts of work–family conflict on health outcomes. Given this past research, and informed by the stress process model, we propose the following hypotheses:

H 1a

Job insecurity will moderate the relationship between work-to-family conflict and poor mental and physical health, such that the impact of work-to-family conflict on poor mental and physical health will be stronger for those reporting job insecurity.

H 1b

Job insecurity will moderate the relationship between family-to-work conflict and poor mental and physical health, such that the impact of family-to-work conflict on poor mental and physical health will be stronger for those reporting job insecurity.

We also expect that given that the experience of job insecurity is more closely tied to the work realm that it will more strongly moderate the impacts of work-to-family conflict on health outcomes compared to family-to-work conflict. In other words, while job insecurity likely heightens the impacts of both forms of work–family conflict on health, we expect job insecurity to be especially potent when combined with work-to-family conflict. This is because job insecurity is likely more intricately linked in the worker’s mind with work pressures and strains, and will be especially impactful in terms of how it combines with those stressors. For example, many of the most quickly felt consequences associated with job insecurity, such as pressure to work longer hours or additional work stressors, likely play out in ways that will make the impacts of work-to-family conflict even more striking. These types of additional stressors are not as tightly connected to family-to-work conflict. We reason that the immediate aftermath of job insecurity, then, will likely create scenarios that are especially problematic for how work-to-family conflict combines with job insecurity in predicting health outcomes. This line of reasoning leads to an additional hypothesis about work–family conflict, job insecurity, and health outcomes:

H 1c

The moderating relationship between job insecurity and work-to-family conflict on poor mental and physical health, will be stronger than the moderating relationship between job insecurity and family-to-work conflict on poor mental and physical health.

4 Gender and Job Insecurity, Work–Family Conflict, and Health

The stress process model emphasizes that the likelihood of exposure to stressors, along with the outcomes associated with stressors, are often contingent on social statuses, such as gender (Pearlin and Bierman 2013). Job loss and insecurity interfere with the ability to provide financially for one’s family, which may be especially stressful among men, who have traditionally been expected to serve as primary breadwinners in their families (Richter et al. 2010). Beyond this, holding a job is about more than just money– people draw meaning and a sense of identity from their jobs, and job loss and insecurity may pose threats to how people think of themselves (Brand 2015; Kalleberg 2009; McDonough 2000). Because employment is so closely connected to the achievement of masculinity in contexts like the US, gender likely plays a role in the processes by which job insecurity and work–family conflict influence health. Indeed, social norms continue to stipulate that men should prioritize breadwinning and women should more strongly identify with the family domain (Demantas and Myers 2015; Frone et al. 1996; Gaunt 2013).

Reflecting these patterns, some past scholarship suggests that not only do men tend to experience higher levels of job insecurity than women (Keim et al. 2014), but the impacts of economic insecurity may be particularly pernicious for men’s self-worth and mental health (Menaghan 1991). For example, one study found that unemployed men suffered on a deep emotional level from job loss, as reflected in struggles with feelings of being worthless and the challenges of coming to terms with threats to their identities (Demantas and Myers 2015).

What might this mean for the joint impact of work–family conflict and job insecurity on health outcomes? While few, if any studies, have looked at this particular question, some previous work has emphasized the relationships between gender, job insecurity, and health outcomes. For example, De Witte’s (1999) analysis of employees of a Belgium plant in the metalworking industry found evidence of gender moderating job insecurity’s relationship with well-being, and other work has highlighted job insecurity and unemployment as key explanatory factors for why men experience greater health inequalities tied to socio-economic status compared to women (Matthews et al. 1999). Despite these patterns, there is some evidence that the impacts of job insecurity on health outcomes are similar among men and women (Cheng and Chan 2008; László et al. 2010) or only somewhat unequal, with men experiencing only slightly poorer health outcomes from job insecurity (Kim and von dem Knesebeck 2015). We believe these findings may be due to job insecurity and gender being studied in isolation from work–family conflict. Because of the gendered expectations interwoven into the work–family interface, it may be the specific presence of job insecurity in the face of work–family conflict that illuminates the role of gender. For example, Richter et al. (2010) found that job insecurity only mattered in predicting the work–family conflict of men, not of women, suggesting that “men might still be more sensitive than women to threats to the work role, and even though the family role has grown in importance for men…the work role may still be significant to their identity” (p. 275).

The experience of work–family conflict itself is tinged by gender, as noted by one qualitative study of fathers in Silicon Valley that found men often downplayed work–family conflict because it served as an unwelcome reminder that they were violating masculinity norms that require always being available at work (Cooper 2000). It may be, then, that men experiencing work–family conflict face particularly detrimental outcomes when it combines with job insecurity, because job insecurity serves as an additional threat to their masculinity. In other words, while job insecurity and work–family conflict are stressful to both men and women, when these stressors combine, men face the additional burden of having their masculinity threatened. This added burden, then, may intensify the impacts of work-to-family conflict on poor mental and physical health outcomes among men when job insecurity is present. Taking this background into account, we propose the following hypotheses:

H 2a

The moderating effect of job insecurity on the relationship between work-to-family conflict and poor mental and physical health will be stronger for men than for women.

H 2b

The moderating effect of job insecurity on the relationship between family-to-work conflict and poor mental and physical health will be stronger for men than for women.

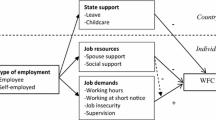

5 Background Variables

The existing literature suggests that it is important to control for several variables when examining the relationships between gender, work–family conflict, job insecurity, and health. As such, this study takes into account social support from family and friends, the presence of preschool children in the household, family income, number of work hours, nonstandard work hours, relationship status, education, race, and age when testing the hypotheses. Social support from family and friends is controlled for because past scholarship suggests that such support might mitigate some of the negative consequences associated with job insecurity and adverse economic events (Keim et al. 2014; Western et al. 2012). We take into account the presence of preschool children because it has been associated with higher levels of work interfering with life, and because working parents must also bear the additional costs of raising children, adding to the worries associated with job insecurity (Moen and Yu 2000).

We consider the number of hours worked because long work hours may operate as a source stress for many workers, and past research has linked work hours to increased psychological distress via increased work-to-family conflict (Cooklin et al. 2015). Work hours may also detract from the time available to engage in self-care activities, thereby potentially worsening health outcomes. The timing of work hours also matters, as working nonstandard shifts can increase psychological distress by making conflict between work and family more likely (Cooklin et al. 2015). Working nonstandard hours has been linked to a number of negative health outcomes, including emotional exhaustion and health problems (e.g., Jamal 2004). Hence, nonstandard work hours are controlled for in the present study.

We also take into account a number of socio-demographic variables, including relationship status, family income, education, race, and age. We control for relationship status because those who are married have another potential worker in the household to rely upon should unexpected job loss occur, thereby potentially buffering negative outcomes associated with job insecurity (Western et al. 2012). Education is considered because work–family conflict (e.g., Schieman and Glavin 2011) and job insecurity (e.g., Elman and O’Rand 2002) vary by educational level. Indeed, education is generally viewed as a protective force against the pitfalls of precarious work (Kalleberg 2009). Moreover, those with higher levels of education experience better physical and mental health outcomes compared to those with less education (e.g., Elo 2009; Ross and Wu 1995). Similarly, we take into account the log of family income because income tends to be positively related to health outcomes (e.g., Elo 2009; Ross and Wu 1995). Indeed, previous work suggests that the challenges associated with navigating the work–family interface vary substantially across the social class spectrum, with low-income families facing especially daunting challenges (e.g., Crouter and Booth 2004). For example, low-income families may face additional stresses, such as fragile child-care networks, scheduling issues, and transitioning from welfare to work, that may interfere with health outcomes.

Previous work has uncovered differing levels of perceived job insecurity among racial groups, with Whites tending to experience less job insecurity than African Americans and Hispanics (Elman and O’Rand 2002; Fullerton and Anderson 2013). Further, there are consistent racial disparities in health outcomes, with research highlighting the disparities in the health of African Americans compared to Whites (e.g., Phelan and Link 2015). Bringing these patterns together, Fullerton and Anderson (2013) emphasized that racial disparities in job insecurity are at least partially responsible for racial inequalities in health outcomes, pointing to the importance of controlling for race. Finally, age is controlled for in this study because workers experience varying levels of work–family conflict and job insecurity across the life course (Buonocore et al. 2015; Keim et al. 2014), and mental and physical health likely vary by age. Some prior research suggests a nonlinear relationship between age and mental health (shown by a U-shaped curve), with negative mental health symptoms declining sharply in early adulthood, leveling off in midlife, and climbing around age 70 (Schieman et al. 2001; Mirowsky and Ross 1992; Miech and Shanahan 2000). Thus, the quadratic term for age is included to test these nonlinear effects. Further, the relationship between job insecurity and poorer health outcomes is stronger among older workers compared to younger workers (Cheng and Chan 2008; Glavin 2015), and older employees experience more negative outcomes in the face of job insecurity, such as low work–family enrichment, reduced vigor, and high work–family conflict, compared to older workers (Mauno et al. 2013; Ruokolainen et al. 2014).

6 Method

6.1 Sample

This study uses data from the 2008 National Study of the Changing Workforce (NSCW) to address the research questions. This dataset was collected by Harris Interactive, Inc. with a questionnaire that was developed by the Families and Work Institute (Families and Work Institute 2008). Over 3000 interviews (N = 3502) were conducted over the telephone between November 12, 2007 and April 20, 2008, with interviews lasting about 50 min on average. Interviewers used a computer-assisted telephone interviewing (CATI) system to complete the interviews. A random-digit dialing method was utilized, and “Sample eligibility was limited to people who (1) worked at a paid job or operated an income-producing business, (2) were 18 years or older, (3) were employed in the civilian labor force, (4) resided in the contiguous 48 states, and (5) lived in a non-institutional residence—i.e., a household—with a telephone. In households with more than one eligible person, one was randomly selected to be interviewed” (Families and Work Institute 2008, p. 3).

The resulting sample is comprised of 3502 working adults (with an estimated overall response rate of 54.6%), and “2769 are waged and salaried workers who work for someone else, while 733 respondents work for themselves—255 business owners who employ others and 478 independent self-employed workers who do not employ anyone else (Families and Work Institute 2008, p. 5)”. The sample is first “weighted by the number of eligibles in the respondents’ households in relation to the percentage of households in the U.S. population with the same number of eligibles (i.e., number of employed persons 18 and older per household with any employed person 18 or older), eligible men and women in the U.S. population and eligibles with different educational levels in the U.S. population (less than high school/GED, high school/GED, some postsecondary, 4-year college degree, post-graduate degree)” (Families and Work Institute 2008, p. 4). After this weighting, the sample is considered to be representative of the U.S. labor force in terms of a variety of demographic and economic characteristics compared to the Current Population Survey conducted in the same years (Families and Work Institute 2008). 2 The sample is also representative of the labor force on a variety of demographic and economic traits as compared to statistics published on labor-force characteristics in 2008 (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics 2009). This study focuses only on waged and salaried workers who are between 18 and 64 years old, which reduced the sample size to 2594 workers. Of these, there were twenty-seven individuals who were missing information on poor mental health, resulting in a sample size of 2567 for the analyses of poor mental health. Similarly, there were three individuals who were missing information on physical health, which leads to a sample size of 2591 for analyses of this dependent variable.

6.2 Measures

The first part of the study tests the effects of work-to-family conflict and family-to-work conflict on poor mental and physical health. The second part of the study tests whether these effects are moderated by job insecurity. The third part of this study tests whether the moderating effect of job insecurity on poor mental and physical health, if any, is different between men and women.

6.2.1 Dependent Variables: Mental and Physical Health

The measure of poor mental health has been used by previous researchers (e.g., Beutell 2013). This scale was available in the dataset as a standardized score, which was “derived through a principal components analysis of items measuring depression and stress (e.g., “how often did you feel depressed or hopeless in the last month?”)” (Beutell 2013, p. 6). Respondents were asked to indicate how frequently they experienced minor health problems, had sleep problems affecting their job performance, felt nervous or stressed, felt unable to control important things in life, felt unable to overcome difficulties, and experienced depression (α = 0.82). Higher scores on this scale indicate worse mental health.

The single-item measure of physical health has also been used in past research (e.g., Beutell 2013). Respondents were asked, “how would you rate your current state of health,” on a four-point scale (poor, fair, good, or excellent). The distribution of this variable is highly skewed, with only 2% of the sample reporting poor physical health. Therefore, in the present study, we combine those who report poor or fair physical health into one group (coded 1), whereas those who report good or excellent physical health remain in separate categories, which are coded 2 and 3, respectively. Thus, the recoded scale for physical health ranges from 1 to 3.

6.2.2 Main Independent Variables: Work-to-Family Conflict and Family-to-Work Conflict

The first independent variable is work-to-family conflict, which was measured with an index of five items that has been used in previous empirical studies (Hill 2005; Voydanoff 2005). Respondents were asked to give their responses to the following questions: (a) In the past 3 months, how often have you not had enough time for your family or other important people in your life because of your job? (b) In the past 3 months, how often has work kept you from doing as good a job at home as you could? (c) In the past 3 months, how often have you not had the energy to do things with your family or other important people in your life because of your job? (d) In the past 3 months, how often has your job kept you from concentrating on important things in your family or personal life? (e) In the past 3 months, how often have you not been in as good a mood as you would like to be at home because of your job? Responses ranged from 1 = never often to 5 = very often. The responses were summed and averaged to create an index, with higher scores indicating higher levels of work-to-family conflict. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.86, showing high internal reliability.

The second independent variable is family-to-work conflict. Family-to-work conflict was measured with an index of five items that has been used by previous researchers (e.g., Zhao et al. 2011). Respondents were asked the following questions: (a) How often have you not been in as good a mood as you would like to be at work because of your personal or family life? (b) How often has your family or personal life kept you from doing as good a job at work as you could? (c) In the past three months, how often has your family or personal life drained you of the energy you needed to do your job? (d) How often has your family or personal life kept you from concentrating on your job? and (e) How often have you not had enough time for your job because of your family or personal life? Respondents were presented with response categories ranging from 1 = never to 5 = very often. The responses were summed and then averaged to create an index, with higher scores indicating higher levels of family-to-work conflict. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.82, showing high internal reliability.

6.2.3 Moderating Variable: Job Insecurity

Job insecurity was measured by the following question: “How likely is it that during the next couple of years you will lose your present job and have to look for a job with another employer?” This one-item measure has been used by previous studies (e.g., Artz and Kaya 2014). The responses ranged from 1 = very likely to 4 = not at all likely. This item was reverse coded, with higher scores indicating higher levels of job insecurity. This variable is highly skewed; 75% of the sample responded either “not too likely” or “not all likely”, where 25% of the sample responded either “somewhat likely” or “very likely.” This variable was treated as a dummy variable those who responded “not too likely” or “not all likely” are collapsed into one group and coded as 0 (i.e., having no job insecurity), and those who responded “somewhat likely” or “very likely” are collapsed into one group and coded as 1 (i.e., having job insecurity).

6.2.4 Control Variables

This study controls for the following variables: social support from family and friends, presence of preschool children living in the household, gender, log of gross annual family income (due to skewness), work hours, nonstandard work hours, relationship status, education, race, age and age squared (for nonlinear effects).

Social support from family and friends was measured with two items: (1) How much do you agree with the following statement: I have the support I need from my family and friends when I have a personal problem? and (2) How much do you agree with the following statement: I have the financial support I need from my family when I have a money problem? For both questions the response options ranged from 1 (strongly agree) to 4 (strongly disagree), and each item was reverse coded such that higher scores indicate more support. Presence of preschool children was coded such that 0 = no such children present in the household and 1 = at least one child under age 6 in the household. The gender of the respondent is coded as 1 = male and 0 = female.

Annual household income was measured by asking for the respondents’ and their spouses’ (if married) total income from all sources before taxes last year (logged income due to skewness). The variable work hours was measured by asking the respondent to report the number of usual hours worked per week. The variable nonstandard work hours was coded such that 0 = respondent worked a regular daytime schedule and 1 = the respondent’s shift differs from a regular daytime schedule. Relationship status was coded as 1 for respondents who are currently married and 0 otherwise. Age was measured in years. The quadratic term for age was also included to test the nonlinear effect. Education was measured by a series of dummy variables: high school graduate or less (reference category), some college, college degree, and postgraduate degree. Race was also measured with a series of dummy variables, with the categories of self-identified as White (reference category), self-identified as Black, or self-identified as another race.

6.3 Analytical Strategy

To analyze the research questions, we used Stata 13.0 statistical software, and employed multiple imputation to handle missing data. The first dependent variable, poor mental health, is an interval measure. Therefore, ordinary least squares regression (OLS) is used. Because physical health is an ordered categorical variable this study uses ordered logistic regression. Due to potential issues of multicollinearity between work-to-family and family–work conflict, these variables are analyzed in separate models. In the first step, the model tests the effects of work-to-family conflict and family-to-work conflict on poor mental and physical health including the control variables (Models 1 and 4, respectively). Models 2 and 5 test Hypotheses 1a–1c, showing whether job insecurity moderates the effects of work-to-family and family-to-work conflict on poor mental and physical health respectively. Next, this paper tests whether the moderating effect of job insecurity on the relationship between work-to-family (and family-to-work) conflict and poor mental (and physical health) differs between men and women. Models 3 and 6 include the three-way interactions between gender, work-to-family (family-to-work) conflict and job insecurity. Models 3 and 6 test Hypothesis 2a and 2b. At each step, the total variance in poor mental and physical health is estimated by R2.

For the missing data in the models, this study employed the multiple imputation method (Allison 2002). The imputation models included all the variables in the analyses. After multiple imputation analyses, the cases that were missing information on both poor mental and physical health were deleted. We use an approach called multiple imputation, then deletion (MID), in which all cases are used for imputation, but then those with missing values on the dependent variable are excluded from the analyses (von Hippel 2007). This is advantageous because it leads to more accurate estimates of the standard error (von Hippel 2007, p. 85).

7 Results

7.1 Descriptive Results

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics for the variables used in this study. The poor mental health scale has an average of −0.35 (ranging from −1.57 to 3.04) and the physical health scale has an average of 2.10 (ranging from 1 to 3), suggesting respondents, on average, have good mental and physical health. On the work-to-family conflict scale, the sample scored an average of 2.57 (ranging from 1 to 5), and an average of 2.11 (ranging from 1 to 5) on family-to-work conflict. Around 25% of the respondents reported job insecurity. The average score for social support was 2.95 (ranging from 1 to 4), suggesting that the average respondent reported moderately high levels of social support. The sample is 83% White, 9% Black, and 8% of respondents identify as belonging to another race. On average, the respondents in the sample are 45 years of age, with about 60% of the sample being married. Around 54% of the sample has at least a Bachelor’s Degree, and 19% of the sample has at least one preschool child living in the household. Around 46% of the sample is male, and 54% is female. On average, those in the sample work 41 h per week, and around 22% of the respondents work nonstandard hours.

7.2 Ordinary Least Squares Regression Results

Ordinary least squares regression analyses were used to test the predictors of poor mental health. Table 2 shows the results. The results of the first model (Model 1) suggest that those who experience more work-to-family conflict have worse mental health after taking into consideration the control variables (b = 0.506, p < .001). Job insecurity is also associated with worse mental health (b = 0.185, p < .001). Model 2 tests the moderating effect of job insecurity by adding an interaction term between work-to-family conflict and job insecurity to the model. The significant interaction term (b = 0.078, p < .05) indicates that the negative impact of work-to-family conflict on poor mental health is stronger for those workers with job insecurity. Thus, Hypothesis 1a, which predicts a stronger effect of work-to-family conflict on poor mental health for those reporting job insecurity, is supported. Model 3 tests whether the moderating effect of job insecurity on the relationship between work-to-family conflict and poor mental health differs between men and women. The nonsignificant three-way interaction (b = −0.026, p > 0.10) indicates that this moderating effect does not differ between men and women. Thus, Hypothesis 2a is not supported.

The findings for Model 4 suggest that those who experience more family-to-work conflict have worse mental health, after taking into account control variables (b = 0.615, p < .001). The findings also suggest that those with job insecurity have worse mental health (b = 0.281, p < .001). Model 5 adds the interaction term between family-to-work conflict and job insecurity. The interaction term is not significant. Thus, Hypothesis 1b, which predicts a stronger effect of family-to-work conflict on poor mental health for those with job insecurity, is not supported. Given that the interaction between family-to-work conflict and job insecurity is not significant in predicting poor mental health (while the corresponding interaction between work-to-family conflict and job insecurity is significant), Hypothesis 1c suggesting a stronger interaction between work-to-family conflict and job insecurity, is supported. Model 6 tests whether the moderating effect of job insecurity on the relationship between family-to-work conflict and poor mental health differs between men and women. The nonsignificant three-way interaction (b = −0.064, p > 0.10) indicates that this moderating effect does not differ between men and women. Thus, Hypothesis 2b is not supported.

7.3 Ordered Logistic Regression Results

Ordered logistic regression analyses are used to test the predictors of physical health. Table 3 shows the results. The results of the first model (Model 1) suggest that those who experience more work-to-family conflict have worse physical health after taking the control variables into account (b = −0.455, p < .001). Model 2 tests the moderating effect of job insecurity. An interaction term between work-to-family conflict and job insecurity is added to the model. The significant interaction term (b = −0.191, p < .05) indicates that the negative impact of work-to-family conflict on physical health is stronger for those workers with job insecurity. Thus, Hypothesis 1a, which predicts a stronger effect of work-to-family conflict on physical health for those reporting job insecurity, is supported. Model 3 tests whether the moderating effect of job insecurity on the relationship between work-to-family conflict and physical health differs between men and women. The nonsignificant three-way interaction (b = 0.181, p > 0.10) indicates that this moderating effect does not differ between men and women. Thus, Hypothesis 2a is not supported.

The findings for Model 4 suggest that those who experience more family-to-work conflict have worse physical health after taking the control variables into consideration (b = −0.454, p < .001). Those with job insecurity have worse physical health (b = −0.207, p < .05). Model 5 adds the interaction term between family-to-work conflict and job insecurity to the analysis. The interaction term is not significant. Thus, Hypothesis 1b, which predicts a stronger effect of family-to-work conflict on physical health for those reporting job insecurity, is not supported. Given that the interaction between family-to-work conflict and job insecurity is not significant in predicting physical health (while the corresponding interaction between work-to-family conflict and job insecurity is significant), Hypothesis 1c suggesting a stronger interaction between work-to-family conflict and job insecurity, is supported. Model 6 tests whether the moderating effect of job insecurity on the relationship between family-to-work conflict and physical health differs between men and women. The nonsignificant three-way interaction (b = 0.272, p > 0.10) indicates that this moderating effect does not differ between men and women, and Hypothesis 2b is not supported.

To allow for fuller interpretation of the two significant interaction effects, we produced the interaction plots depicted in Figs. 1 and 2. Figures 1 and 2 show the relationships between work-to-family conflict and mental (and physical) health for those with job insecurity and no job insecurity respectively. As seen in Fig. 1, higher work-to-family conflict is associated with greater mental health problems and this positive effect (as reflected in the upward direction of the line) is stronger for those with job insecurity. Figure 2 shows that higher work-to-family conflict is associated with worse physical health and this negative effect (as reflected in the downward direction of the line) is stronger for those with job insecurity.

Turning to the control variables, the following variables are consistently significant across all models in predicting poor mental health and physical health: social support, family income, education and age. Overall, this study finds that more social support and higher family income are both associated with better mental and physical health. In addition, those with higher education report better mental and physical health. Finally, the significant coefficient for the quadratic term for age suggests that there is a nonlinear effect of age on poor mental and physical health.

Overall, our results suggest that respondents with higher levels of work-to-family conflict and family-to-work conflict report worse mental and physical health. The negative effects of work-to-family conflict on mental and physical health are both found to be stronger among those with job insecurity. We found no evidence of significant gender differences in how work-to-family (and family-to-work) conflict and job insecurity jointly predict poor mental and physical health.

8 Discussion

Using data from just under 2600 workers from the National Study of the Changing Workforce (NSCW), this study tested whether job insecurity moderates the effects of work-to-family conflict and family-to-work conflict on poor mental and physical health. Additionally, this study examined whether these moderating effects of job insecurity differ between men and women. As hypothesized, this study finds that the negative effect of work-to-family conflict on poor mental and physical health is stronger for those with job insecurity. We found no evidence of significant gender differences in the joint impacts of work–family conflict and job insecurity on poor mental and physical health.

All in all, our findings highlight that both forms of work–family conflict, along with job insecurity, shape poor mental and physical health, thereby adding to existing understandings of the stress process (Pearlin 1989; Pearlin and Bierman 2013; Pearlin et al. 1981). At a basic level, the findings about the direct relationships between work-to-family conflict and family-to-work conflict and health outcomes confirm those from past research (e.g., Allen et al. 2000), emphasizing the concrete health costs associated with work–family conflict. Given the precariousness and economic insecurity pervasive across the US economy (Kalleberg 2009), we add to the literature by considering the moderating role of job insecurity. Whereas previous research has tended to include job insecurity as one of many job demands or stressors (Batt and Valcour 2003; Jansen et al. 2003; Schieman et al. 2009; Voydanoff 2005), we bring it to the forefront, and find that it does, indeed, intensify the effects of work-to-family conflict on health outcomes.

The pernicious nature of the anticipatory stressor of job insecurity in making the negative health outcomes associated with work-to-family conflict worse needs to be further emphasized in future work informed by the stress process model. By doing so, we will deepen our understanding of the stressors associated with potential job loss, which impact workers in dynamic ways. The evidence from this study suggests that while job insecurity moderated the relationships between work-to-family conflict and health outcomes, it did not appear to play a similar role for family-to-work conflict. Why might this be the case? The most likely explanation is that job insecurity is likely blamed on the workplace and the larger macro-economic situation, so it intensifies negativity that spills from work to family rather than from family to work. For example, workers may be called upon or feel pressure to work longer hours to keep their jobs in such an atmosphere, while they feel no such similar pressure to increase work time within the family realm. Worries about job loss combining with the chronic stressor of work-to-family conflict, then, may leave workers drained and exhausted. It may also be that feelings of job insecurity are more likely to surface in the workplace, thereby influencing stress transfer from work to family rather than vice versa. A related explanation is that job insecurity might moderate how family-to-work conflict relates to outcomes other than mental and physical health, such as relationship satisfaction or parenting quality.

In contrast to our expectations, we found no evidence of significant gender differences in the combined impacts of work–family conflict and job insecurity on poor mental and physical health. This finding echoes past research that suggests few or no gender differences in how job insecurity impacts health outcomes (Cheng and Chan 2008). However, this finding contrasts with past research that emphasized the strongly negative mental health effects accruing to men upon job loss and unemployment (e.g., Demantas and Myers 2015; Legerski and Cornwall 2010). Why do our findings differ? It may be the case that the additional stress of job insecurity threatening masculinity only occurs when actual job loss takes place. Perhaps in the face of job insecurity men can find ways to cope with the situation that actually enhance their masculinity, such as working extra hard or putting in long hours to try to hold onto their jobs. In this way, then, they might not experience the extra burden posed by having their masculinity threatened; hence, the similar outcomes for men and women. It may also be the case that these relationships may depend on gender role orientations or ideologies, which we were unable to take into account. Past research, for example, suggests that work–family conflict often has differential impacts on outcomes based on the extent of gender traditionalism or gender egalitarianism embraced by men and women (e.g., Livingston and Judge 2008; Minnotte et al. 2010, 2013b). Another potential explanation for these findings lies in the path-breaking work of Robin W. Simon (e.g., 1995) whose work underscored the different meanings that men and women bring to paid work. In particular, her work suggested that men experience fewer mental health detriments stemming from multiple roles and issues of work–family conflict because women face greater feelings of guilt associated with the perceived inability to fulfil familial and caregiving duties (Simon 1995). Similarly, work by Williams (2001) suggests that both men and women face negative consequences from work–family conflict, but the reasons underlying the negative consequences may differ. In terms of our findings, Simon’s work (1995), combined with that of other scholars mentioned previously (e.g., Demantas and Myers 2015; Legerski and Cornwall 2010; Williams 2001), suggests that both men and women may be equally likely to be distressed by issues like job insecurity, but the reasons underlying the distress differs. We are hopeful that future work will further address how the stressors underlying job insecurity might diverge by gender.

There are several limitations of this research. The main limitation of this study resulted from its cross-sectional nature, which prevents inferring causality between variables. In the future, researchers may measure both forms of work–family conflict and health outcomes (mental and physical health) at different points in time, to demonstrate a causal relationship between the variables. Second, without longitudinal data, the long-term impact of work–family conflict and job insecurity on health outcomes cannot be explored. Third, physical health and job insecurity were both measured with one item. This might have created issues in terms of reliability, and likely introduced measurement error into the analyses.

Nevertheless, this study makes several contributions. First, this study makes a significant contribution to the work–family literature and our understanding of the stress process by empirically testing the moderating effect of job insecurity on the relationship between work–family conflict and health outcomes, and by testing whether this moderating effect varies between men and women. Second, while prior work has begun to delve into the relationships between job insecurity and work–family conflict in specialized populations (e.g., Cheng et al. 2014; Cooklin et al. 2015), this study uses a sample that includes workers across various occupations and life stages. Altogether, by bringing together scholarship on work-to-family conflict and job insecurity, we are able to enhance understandings of men and women’s mental and physical health during times of widespread job insecurity in the US labor force.

In conclusion, informed by the stress process model, and building on scholarship that emphasizes the economic precariousness and pervasive job insecurity across the US (e.g., Kalleberg 2009), our study finds that work-to-family conflict and job insecurity work together jointly to influence poor mental health and physical health among US workers. In terms of further investigating how macro-economic conditions shape the work–family interface, there are several promising avenues for future research. Research that nests workers within couples to see how each partner’s job insecurity comes into play would be particularly illuminating, because the economic situation of the partner may impact how threatening job insecurity may be to the financial well-being of the family. Likewise, comparative research considering how different family types respond to job insecurity and work–family conflict can help us to further understand the unique challenges and privileges various family formations face. The present study failed to find a moderating relationship between family-to-work conflict, job insecurity, and poor mental health and physical health, so it might also be informative to examine outcomes beyond health, such as relationship quality or parenting quality, to clarify whether and how these variables might operate together to shape outcomes. Future work would also benefit from a closer analysis of how these relationships may vary across life stages. This is especially important because prior work suggests that the work–family interface might be differentially experienced across generations (e.g., Beutell 2013), and the impacts of job insecurity might be especially detrimental to older workers (e.g., Glavin 2015). Previous work also points to the role of age in shaping health outcomes (e.g., Schieman et al. 2001; Mirowsky and Ross 1992; Miech and Shanahan 2000), and future work would do well to further explore the non-linear impact of age on a variety of health-related outcomes. Taken together, such future work will help paint a more dynamic and complex picture of how the larger macro-economic landscape shapes the lives of workers across the work–family interface.

Notes

The stress process model also highlights mediators of stress, such as social support or coping strategies, that buffer the impacts of stress (Pearlin et al. 1981). Although an important part of the stress process, we do not focus on mediators of stress here. Instead, we consider how two sources of stress combine to impact the manifestations of stress.

References

Allen, T. D., Herst, D. E. L., Bruck, C. S., & Sutton, M. (2000). Consequences associated with work-to-family conflict: A review and agenda for future research. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5, 278–308.

Allison, P. D. (2002). Missing data. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Amstad, F. T., Meier, L. L., Fasel, U., Elfering, A., & Semmer, N. K. (2011). A meta-analysis of work–family conflict and various outcomes with a special emphasis on cross-domain versus matching-domain relations. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 16, 151–169.

Artz, B., & Kaya, I. (2014). The impact of job security on job satisfaction in economic contractions versus expansions. Applied Economics, 46, 2873–2890.

Batt, R., & Valcour, P. M. (2003). Human resources practices as predictors of work–family outcomes and employee turnover. Industrial Relations, 42, 189–220.

Bellavia, G., & Frone, M. R. (2005). Work–family conflict. In J. Barling, E. K. Kelloway, & M. R. Frone (Eds.), Handbook of work stress (pp. 113–147). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Beutell, N. J. (2013). Generational differences in work–family conflict and synergy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 10, 2544–2559.

Brand, J. E. (2015). The far-reaching impact of job loss and unemployment. Annual Review of Sociology, 41, 359–375.

Buonocore, F., Russo, M., & Ferrara, M. (2015). Work–family conflict and job insecurity: Are workers from different generations experiencing true differences? Community, Work, & Family, 18, 299–316.

Burgard, S. A., Brand, J. E., & House, J. S. (2009). Perceived job insecurity and worker health in the United States. Social Science and Medicine, 69, 777–785.

Burgard, S. A., & Kalousova, L. (2015). Effects of the Great Recession: Health and well-being. Annual Review of Sociology, 41, 181–201.

Burley, K. A. (1995). Family variables as the mediators of the relationship between work–family conflict and marital adjustment among dual-career men and women. The Journal of Social Psychology, 135, 483–497.

Cheng, G. H.-L., & Chan, D. K.-S. (2008). Who suffers more from job insecurity? A meta-analytic review. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 57, 272–303.

Cheng, T., Mauno, S., & Lee, C. (2014). Do job control, support, and optimism help job insecure employees? A three-waive study of buffering effects on job satisfaction, vigor and work–family enrichment. Social Indicators Research, 118, 1269–1291.

Cooklin, A. R., Giallo, R., Strazdins, L., Martin, A., Leach, L. S., & Nicholson, J. M. (2015). What matters for working fathers? Job characteristics, work–family conflict and enrichment, and fathers’ postpartum mental health in an Australian cohort. Social Science and Medicine, 146, 214–222.

Cooper, M. (2000). Being the “go-to-guy”: Fatherhood, masculinity, and the organization of work in Silicon Valley. Qualitative Sociology, 23, 379–405.

Crouter, A. C., & Booth, A. (2004). Work–family challenges for low-income parents and their children. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

De Witte, H. (1999). Job insecurity and psychological well-being: Review of the literature and exploration of some unresolved issues. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 8, 155–177.

Demantas, I., & Myers, K. (2015). ‘Step up and be a man in a different manner’: Unemployed men reframing masculinity. The Sociological Quarterly, 56, 640–664.

Elman, C., & O’Rand, A. M. (2002). Perceived job insecurity and entry into work-related education and training among adult workers. Social Science Research, 31, 49–76.

Elo, I. T. (2009). Social class differentials in health and mortality: Patterns and explanations in comparative perspective. Annual Review of Sociology, 35, 553–572.

Elst, T. V., Näswall, K., Bernhard-Oettel, C., & De Witte, H. (2015). The effect of job insecurity on employee health complaints: A within-person analysis of the explanatory role of threats to the manifest and latent benefits of work. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. doi:10.1037/a0039140.

Families and Work Institute. (2008). National study of the changing workforce guide to public use files. New York, NY: Families and Work Institute.

Frone, M. R., Russell, M., & Barnes, G. M. (1996). Work–family conflict, gender, and health-related outcomes: A study of employed parents in two community samples. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 1, 57–69.

Frone, M. R., Russell, M., & Cooper, M. L. (1992a). Prevalence of work–family conflict: Are work and family boundaries asymmetrically permeable? Journal of Organizational Behavior, 13, 723–729.

Frone, M. R., Russell, M., & Cooper, M. L. (1992b). Antecedents and outcomes of work–family conflict: Testing a model of the work–family interface. Journal of Applied Psychology, 77, 65–78.

Fullerton, A. S., & Anderson, K. F. (2013). The role of job insecurity in explanations of racial health inequalities. Sociological Forum, 28, 308–325.

Gaunt, R. (2013). Breadwinning moms, caregiving dads: Double standards in social judgments of gender norm violators. Journal of Family Issues, 34, 3–24.

Gilboa, S., Shirom, A., Fried, Y., & Cooper, C. (2008). A meta-analysis of work demand stressors and job performance: Examining main and moderating effects. Personnel Psychology, 61, 227–271.

Glavin, P. (2015). Perceived job insecurity and health: Do duration and timing matter? The Sociological Quarterly, 56, 300–328.

Glavin, P., & Schieman, S. (2014). Control in the face of uncertainty: Is job insecurity a challenge to the mental health benefits of control beliefs. Social Psychology Quarterly, 77, 319–343.

Greenhaus, J. H., & Beutell, N. J. (1985). Sources of conflict between work and family roles. The Academy of Management Review, 10, 76–88.

Grusky, D., Western, B., & Wimer, C. (2011). The consequences of the Great Recession. In D. Grusky, B. Western, & C. Wimer (Eds.), The Great Recession (pp. 3–21). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Grzywacz, J. G., & Bass, B. L. (2003). Work, family, and mental health: Testing different models of work–family fit. Journal of Marriage and Family, 65, 248–262.

Hammer, T. H., Saksvik, P. O., Nytrø, K., Torvatn, H., & Bayazit, M. (2004). Expanding the psychosocial work environment: Workplace norms and work–family conflict as correlates of stress and health. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 9, 83–97.

Hill, E. J. (2005). Work–family facilitation and conflict, working fathers and working mothers, work–family stressors and support. Journal of Family Issues, 26, 793–819.

Höge, T., Sora, B., Weber, W. G., Peiró, J. M., & Caballer, A. (2015). Job insecurity, worries about the future, and somatic complaints in two economic and cultural contexts: A study in Spain and Austria. International Journal of Stress Management, 22, 223–242.

Jamal, M. (2004). Burnout, stress and health of employees on non-standard work schedules: A study of Canadian workers. Stress and Health, 20, 113–119.

Jansen, N. W. H., Kant, I., Kristensen, T. S., & Nijhuis, F. J. N. (2003). Antecedents and consequences of work–family conflict: A prospective cohort study. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 45, 479–491.

Jiang, L., & Probst, T. M. (2015). A multilevel examination of affective job insecurity climate on safety outcomes. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. doi:10.1037/ocp0000014.

Kalleberg, A. L. (2009). Precarious work, insecure workers: Employment relations in transition. American Sociological Review, 74, 1–22.

Keim, A. C., Landis, R. S., Pierce, C. A., & Earnest, D. R. (2014). Why do employees worry about their jobs? A meta-analytic review of predictors of job insecurity. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 19, 269–290.

Kim, T. J., & von dem Knesebeck, O. (2015). Is an insecure job better for health than having no job at all? A systematic review of studies investigating the health-related risks of both job insecurity and unemployment. BMC Public Health, 15, 1–9.

Låstad, L., Berntson, E., Näswall, K., Lindfors, P., & Sverke, M. (2015). Measuring quantitative and qualitative aspects of the job insecurity climate. Career Development International, 20, 202–217.

László, K. D., Pikhart, H., Kopp, M. S., Bobak, M., Pajak, A., Malyutina, S., et al. (2010). Job insecurity and health: A study of 16 European countries. Social Science and Medicine, 70, 867–874.

Lawrence, E. R., Halbesleben, J. R. B., & Paustian-Underdahl, S. C. (2013). The influence of workplace injuries on work–family conflict: Job and financial insecurity as mechanisms. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 18, 371–383.

Legerski, E. M., & Cornwall, M. (2010). Working-class job loss, gender, and the negotiation of household labor. Gender & Society, 24, 447–474.

Livingston, B. A., & Judge, T. A. (2008). Emotional responses to work–family conflict: An examination of gender role orientation among working men and women. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93, 207–216.

Matthews, S., Manor, O., & Power, C. (1999). Social inequalities in health: Are there gender differences? Social Science and Medicine, 48, 49–60.

Mauno, S., Ruokolainen, M., & Kinnunen, U. (2013). Does aging make employees more resilient to job stress? Age as a moderator in the job stressor-well-being relationship in three Finnish occupational samples. Aging and Mental Health, 17, 411–422.

McDonough, P. (2000). Job insecurity and health. International Journal of Health Services, 30, 453–476.

Menaghan, E. G. (1991). Work experiences and family interaction processes: The long reach of the job? Annual Review of Sociology, 17, 419–444.

Miech, R. A., & Shanahan, M. J. (2000). Socioeconomic status and depression over the life course. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 41, 62–76.

Minnotte, K. L., Gravelle, M. & Minnotte, M. C. (2013a). Workplace characteristics, work-to-life conflict, and psychological distress among medical workers. The Social Science Journal, 50, 408–417.

Minnotte, K.L., Minnotte, M.C., Pedersen, D.E., Mannon, S.E. & Kiger, G. (2010). His and her perspectives: Gender ideology, work-to-family conflict, and marital satisfaction. Sex Roles, 63, 425–438.

Minnotte, K. L., Minnotte, M. C., & Pedersen, D. E. (2013b). Marital Satisfaction among dual-earner couples: Gender ideologies and family to work conflict. Family Relations, 62(4), 686–698.

Mirowsky, J., & Ross, C. E. (1992). Age and depression. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 33, 187–205.

Moen, P., & Yu, Y. (2000). Effective work/life strategies: Working couples, work conditions, gender, and life quality. Social Problems, 47, 291–326.

Pearlin, L. I. (1989). The sociological study of stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 30, 241–256.

Pearlin, L. I., & Bierman, A. (2013). Current and future directions in research into the stress process. In C. S. Aneshensel, J. C. Phelan, & A. Bierman (Eds.), Handbook of the sociology of mental health (pp. 325–340). Dordrecht: Springer.

Pearlin, L. I., Lieberman, M. A., Menaghan, E. G., & Mullan, J. T. (1981). The stress process. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 22, 337–356.

Phelan, J. C., & Link, B. G. (2015). Is racism a fundamental cause of inequalities in health? Annual Review of Sociology, 41, 311–330.

Piccoli, B., & De Witte, H. (2015). Job insecurity and emotional exhaustion: Testing psychological contract breach versus distributive injustice as indicators of lack of reciprocity. Work & Stress, 29, 246–264.

Richter, A., Näswall, K., Lindfors, P., & Sverke, M. (2015). Job insecurity and work–family conflict in teachers in Sweden: Examining their relations with longitudinal cross-lagged modeling. Psych Journal, 4, 98–111.

Richter, A., Näswall, K., & Sverke, M. (2010). Job insecurity and its relation to work–family conflict: Mediation with a longitudinal data set. Economic and Industrial Democracy, 31, 265–280.

Ross, C. E., & Wu, C. (1995). The links between education and health. American Sociological Review, 60, 719–745.

Ruokolainen, M., Mauno, S., & Cheng, T. (2014). Are the most dedicated nurses more vulnerable to job insecurity? Age-specific analyses on family-related outcomes. Journal of Nursing Management, 22, 1042–1053.

Scherer, S. (2009). The social consequences of insecure jobs. Social Indicators Research, 93, 527–547.

Schieman, S., & Glavin, P. (2011). Education and work–family conflict: Explanations, contingencies, and mental health consequences. Social Forces, 89, 1341–1362.

Schieman, S., Glavin, P., & Milkie, M. A. (2009). When work interferes with life: Work-nonwork interference and the influence of work-related demands and resources. American Sociological Review, 74, 966–988.

Schieman, S., Van Gundy, K., & Taylor, J. (2001). Status, role, and resource explanations for age patterns in psychological distress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 42, 80–96.

Schieman, S., & Young, M. (2011). Economic hardship and family-to-work conflict: The importance of gender and work conditions. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 32, 46–61.

Schneider, D. (2015). The great recession, fertility, and uncertainty: Evidence from the United States. Journal of Marriage and Family, 77, 1144–1156.

Simon, R. W. (1995). Gender, multiple roles, role meaning, and mental health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 36, 182–194.

Sverke, M., & Hellgren, J. (2002). The nature of job insecurity: Understanding employment uncertainty on the brink of a new millennium. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 51, 23–42.

Sverke, M., Hellgren, J., & Näswall, K. (2002). No security: A meta-analysis and review of job insecurity and its consequences. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 7, 242–264.

United States Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2009). Labor force characteristics by race and ethnicity, 2008. Washington, DC: Author. http://digitalcommons.ilr.cornell.edu/key_workplace/686.

van Veldhoven, M. J. P. M., & Beijer, S. E. (2012). Workload, work-to-family conflict, and health: Gender differences and the influence of private life context. Journal of Social Issues, 68, 665–683.

von Hippel, P. T. (2007). Regression with missing Ys: An improved strategy for analyzing multiply imputed data. Sociological Methodology, 37, 83–117.

Voydanoff, P. (1988). Work-role characteristics, family structure demands, and work–family conflict. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 50, 749–761.

Voydanoff, P. (2002). Linkages between the work–family interface and work, family, and individual outcomes. Journal of Family Issues, 23, 138–164.

Voydanoff, P. (2005). Work demands and work-to-family conflict and family-to-work conflict: Direct and indirect relationships. Journal of Family Issues, 26, 707–726.

Voydanoff, P. (2007). Work, family, and community: Exploring interconnections. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Wang, H., Lu, C., & Sui, O. (2015). Job insecurity and job performance: The moderating role of organizational justice and the mediating role of work engagement. Journal of Applied Psychology, 110, 1249–1258.

Western, B., Bloome, D., Sosnaud, B., & Tach, L. (2012). Economic insecurity and social stratification. Annual Review of Sociology, 38, 341–359.

Williams, J. (2001). Unbending gender: Why family and work conflict and what to do about it. New York: Oxford University Press.

Zhao, X., Qu, H., & Ghiselli, R. (2011). Examining the relationship of work–family conflict to job and life satisfaction: A case of hotel sales managers. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 30, 46–54.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Minnotte, K.L., Yucel, D. Work–Family Conflict, Job Insecurity, and Health Outcomes Among US Workers. Soc Indic Res 139, 517–540 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-017-1716-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-017-1716-z