Abstract

In recent years, an increasing number of studies have investigated the well-being of international immigrants in host countries. An important indicator of immigrants’ well-being is job satisfaction. Job satisfaction reflects a pleasant emotional state, in which individuals positively appraise their job or work experience. In this article, we discuss the determinants of immigrants’ job satisfaction, based on research conducted over the past three and a half decades. The determinants observed in the literature can be categorized into work- and non-work-related groups. Work-specific determinants include workplace environments, job characteristics, and work-specific personal factors (e.g., competency-related factors, psychological states, and work-specific demographics). Non-work-specific determinants include general demographics, culture-related factors (e.g., language, cultural traits, and acculturation), and community-related factors. This review demonstrates that past research has made important strides toward our understanding of the influential factors leading to immigrants’ job satisfaction. We call for future research to continue to explore these factors, as well as new factors, given the limited empirical evidence that exists for this population group.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Over the past few decades, many countries that accept immigrants (e.g., the United States of America, Canada, New Zealand, and Australia) have experienced an increase in international migrants (Khawaja et al. 2016), making these countries increasingly culturally diverse. These immigrants have made non-negligible contributions to the economic and societal advancement of their host countries (Lu et al. 2011). An important part of the workforce, immigrants are spread across various industries in which they contribute their experience, knowledge, expertise, and skills (De Haas 2010).

With the increase in the immigrant workforce, researchers have begun to focus on migrant workers’ well-being. In this inquiry, research is largely concentrated on the overall life well-being of immigrants. For example, Findlay and Nowok (2012) investigated the changes in life satisfaction of migrants moving to Britain, and found that immigrants’ satisfaction significantly increased after migration. Schwartz et al. (2013) explored the link between acculturation and immigrants’ well-being among six ethnic groups, and found that effective acculturation had positive correlations with well-being. In addition to general, or life, well-being, there are other domains or sub-domains of well-being that are valued by immigrants. For instance, an individuals’ well-being in the workplace significantly contributes to their general well-being or life satisfaction, considering that a job is an important part of a person’s life (Judge and Watanabe 1993; Rice et al. 1980). Empirical research has shown that immigrants’ job satisfaction is influenced by a number of work and non-work factors (An et al. 2016; Flap and Völker 2001; Gazioglu and Tansel 2006). While existing studies have provided scattered evidence on how immigrants’ job satisfaction is shaped, a comprehensive review that synthesizes the findings on the determinants of job satisfaction among immigrant workers has not yet been observed. The purpose of this article is to review the literature, and provide a brief summary and analysis of the factors contributing to immigrants’ job satisfaction. Such a review is important because it can not only help host countries to optimize their migration frameworks, also assist employers of the host countries in identifying appropriate management practices to improve immigrants’ workplace well-being.

Based on our review, we categorized the factors identified in past research into two major groups: work-related factors and non-work-specific factors. Work-related factors are those aspects directly perceived and developed in the workplace. For example, the work environment, job characteristics, and other work-specific personal factors such as competency, psychological states, and work-related demographics. In comparison, non-work-related factors are those aspects that are beyond work contexts but can affect immigrants’ job satisfaction. These include general personal characteristics, cultural factors, and societal and community factors. In line with best practice (Short 2009), we used Web of Science, Science Direct, Google Scholar, and other related databases to identify peer-reviewed articles with immigrant, migrant, and job satisfaction in their titles, abstracts, and keywords. We restricted our search to articles published between 1980 and 2016 as, from the 1980s, the emergence and development of globalization has meant immigration has become increasingly popular, and scholars have paid more attention to immigrants’ workplace well-being. We organized our review into four main sections. In the next sections, we firstly define job satisfaction and present an overall framework of our review. We then discuss two major groups, work-related and non-work-specific, of the antecedents of immigrants’ job satisfaction. Finally, we conclude this review by highlighting implications, limitations, and future research directions.

2 Job Satisfaction

Job satisfaction has received a lot of research attention, as it is associated with a broad range of issues in the work context (Aziri 2011). Due to its subjective psychological state, there is no unified definition of job satisfaction (Aziri 2011). The definitions vary with the approaches used for analysis. Locke (1976, p. 316) defined job satisfaction as “the pleasurable emotional state resulting from the subjective appraisal of one’s job, as a result of achieving or facilitating the achievement of one’s job values”. Price (2001) defined job satisfaction as an employee’s affective orientation toward their job, and contends that it is a global feeling about the job or an associated series of attitudes about different aspects or facets of the job. These differences in the definition of job satisfaction reflect that the determinants, or sources, of job satisfaction are complex and varied (Judge and Hulin 1993; Quarstein et al. 1992).

Job satisfaction can have an effect on an employee’s performance as well as on organizational outcomes. For example, at the individual level, past research has found that job satisfaction is positively related to an employee’s organizational commitment (Tett and Meyer 1993), trust in the organization (Braun et al. 2013), organizational citizenship behavior (Williams and Anderson 1991), job performance (Fu and Deshpande 2014), and knowledge sharing (Jiang and Hu 2016). It is negatively related to absenteeism (Scott and Taylor 1985), and turnover intention (Tett and Meyer 1993). At the organizational level, individuals’ job satisfaction has been reported to produce a positive influence on organizational performance (Wood et al. 2012). Due to the importance of job satisfaction in fostering positive, and mitigating negative, employee, and organizational outcomes, it would be useful to understand which factors drive employees’ satisfaction at work. Identifying the determinants, or sources, of job satisfaction is valuable, as this information can help managerial practitioners better understand which factors will contribute to a happy workplace (Spector 1997). Different authors start from different perspectives to study how job satisfaction is shaped, produced, or enhanced. With diverse perspectives, past research has discovered a variety of different factors that have been shown to affect job satisfaction (Aziri 2011). In general, the factors that influence job satisfaction, and how their influence is exhibited, may be explained using the following theoretical models, the person effects model, the situation effects model, and the interaction model (Arvey et al. 1991).

The specified person effects model highlights that there are significant associations between personal variables and job satisfaction. The causality of such association is directional, running from personal variables to job satisfaction (Arvey et al. 1991). Generally, individual psychological states and demographics are identified as the personal factors in the research that adopts this model (Arvey et al. 1991). For example, Luthans et al. (2007) illustrated that positive psychological capital is directly related to increased job performance and satisfaction. Similarly, Rhodes (1983) discovered that there is a positive correlation between age and job satisfaction, implying that demographics such as age may affect an individual’s reflection of associated contexts as well their psychological states.

The specified situational effects model emphasizes the relationship between external, situational, or contextual factors, and job satisfaction. These external factors, identified by past research, include work environment or organizational climate, the characteristics of the job, and other environmental characteristics that may or may not be directly related to the workplace (Arvey et al. 1991). For instance, Fu and Deshpande (2014) suggested that the organizational climate significantly and directly affects employees’ job satisfaction. Based on the study’s findings, they concluded that a positive organizational climate leads to an increase in employees’ satisfaction with their jobs, as well as increases in work performance, and organizational commitment. In another study, Baernholdt and Mark (2009) found that an employee’s job satisfaction varies significantly with the characteristics of the job and, particularly, the complexity of the job. Specifically, an increment of work complexity results in decreased job satisfaction. In short, the specified situational effects model demonstrates that situational factors can cause a change in job satisfaction.

The interactional model specifies that personal and situational factors interact and collectively influence job satisfaction. Scholars argue that job satisfaction is shaped by the congruence of personal and environmental factors (Weiss and Adler 1984). Schneider (1987) illustrate that individuals prefer work environments with different characteristics, depending on their personality, to the extent that they actively put themselves into or out of specific job environments until they reach the congruence of personal and environmental variables. The congruence between personal and environmental characteristics leads to person–environment fit. This optimizes work performance, maintains an employees’ tenure with the organization or in the job, and eventually results in a higher level of job satisfaction (Arvey et al. 1991).

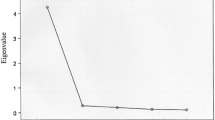

In our review, we have identified two primary groups of factors that influence immigrant workers’ job satisfaction: (1) work-related factors, and (2) non-work-specific factors. Our findings appear to be in alignment with the existing job satisfaction theories and models. Work-related factors include work environment or context, job characteristics, and work-specific personal factors. While work environment and job characteristics can be categorized into the specified situational effects model, work-specific personal factors are in line with the specified personal effects model (Arvey et al. 1991). Non-work-specific factors consist of general demographics, general psychological states, personal cultural attributes, society- or policy-related factors, and community- or living environment-related factors. While general demographics, psychological state, and personal cultural attributes are equivalent to the dispositional or personal factors in the specified person effects model of job satisfaction, the remaining factors accord with the factors reflected in the specified situational model (Arvey et al. 1991). These factors, whether they are work- or non-work-related, can independently influence immigrants’ job satisfaction. They also interact to produce influences, that is, immigrant workers’ job satisfaction can be shaped by the joint effects of work-related factors and non-work-specific factors. In the following sections, we discuss these factors in detail. A summary of the factors is presented in Fig. 1.

3 Work-Related Factors

It is widely known that work-related factors can profoundly influence immigrants’ job satisfaction (Roelen et al. 2008). A review of the literature suggests that these factors can be categorized into three main groups: work environment or context, job characteristics, and work-specific personal factors. Although some scholars view job characteristics as part of the contextual factors (Arvey et al. 1991), in this article, we treat workplace environmental factors and job characteristics as two separate categories. We consider environmental factors as those more related to climate, atmosphere, and management systems, and job characteristics as those more specifically linked to the position that an individual holds in the organization. In this section, we discuss how these factors can shape immigrants’ satisfaction at work.

3.1 Environmental Factors in the Workplace

A significant amount of research indicates that the work environment can play a significant role in developing immigrants’ job satisfaction (Lu et al. 2005; Shalley et al. 2000). A theoretical perspective that may explain the role of the work environment is that, when individuals perceive and interpret information sent by their associated environment, they may develop a variety of psychological states (e.g., feelings and attitudes) (Jones and James 1979; May et al. 2004). Although the work environment may be viewed as an overall system that integrates all contextual characteristics within the organization, empirical studies normally focus on more specific aspects of work environment such as management practices, climate, and social relationships. The importance of this focus is reflected in the practical implications generated from job satisfaction research. For example, when managers have the knowledge of what types of management practices and specific climates (e.g., supportive, discriminative, or fair) can promote or hamper an employee’s satisfaction, they are able to use targeted approaches to achieve managerial goals, such as improved job satisfaction among subordinates (Mosadegh Rad and Yarmohammadian 2006). Below, we review prior research that specifically examines immigrant workers’ job satisfaction, and we discuss in detail how satisfaction can be influenced by environmental factors in the workplace.

The current literature has illustrated that discrimination and unfair treatment at work have negative effects on immigrants’ job satisfaction (Ensher et al. 2001). Work-related discrimination refers to the discrimination against an individual’s characteristics, such as race, ethnicity, age, gender, cultural background, education, and physical abilities (Wadsworth et al. 2007). Studies have shown that such discrimination results in the reduced psychological well-being of the employee, and eventually leads to lower job satisfaction (Roberts et al. 2004; Wadsworth et al. 2007). Past research consistently demonstrates that workplace discrimination is a non-negligible phenomenon for migrants, and that being discriminated against could considerably hinder the development and maintenance of their satisfaction at work. For example, Magee and Umamaheswar (2011) investigated the job satisfaction of 659 Canadian English-speaking workers, including 119 foreign-born migrant workers. They found that 22.7% of foreign-born migrant workers experienced work-related discrimination, and this unpleasant experience dramatically reduced their job satisfaction.

Unfair treatment at work, including distributive injustice, procedural injustice, and interactional injustice (Cojuharenco et al. 2011), are also detrimental to job satisfaction. Distributive injustice arises when outcomes are not distributed fairly. Procedural injustice refers to the unfairness of the procedures used to achieve these outcomes. Interactional injustice is defined as unfairness of interpersonal and informational aspects when interacting with others in the workplace. If an employee notices that resources related to work, such as instruments, are not allocated or distributed equally, or co-workers are verbally abusive, they may consider this a form of discrimination, and this may result in job dissatisfaction. Current research has shown that foreign-born migrant workers who are treated unfairly at work generally have low job satisfaction (Magee and Umamaheswar 2011).

High Performance Work Systems (HPWS) is a range of human resource management practices that are implanted to create an inclusive and responsible environment to empower and motivate employees, with the purpose of improving the organization’s effectiveness (Levine 2001). The literature suggests that HPWS is a significant factor in influencing an employee’s job satisfaction. Research conducted among immigrants demonstrated that HPWS practices were positively related to immigrants’ overall job satisfaction (Chowhan et al. 2016). To a large extent, this is because HPWS can enhance an employees’ motivation, skills, and empowerment. HPWS is likely to be particularly valued by immigrants when they seek further development and opportunities in their working lives (Chowhan et al. 2016).

Workplace support has been confirmed to be an additional environmental factor that can significantly increase migrant workers’ job satisfaction (Hombrados-Mendieta and Cosano-Rivas 2013). Employees may perceive support from the organization, their superior, or their co-workers. Organizational support theory demonstrates that, if employees sense that their organizations care about their well-being, and value their contributions, employees tend to perform better (Yu and Frenkel 2013). An et al. (2016) have observed a strong and positive correlation between perceived organizational support and job satisfaction among immigrant Korean nurses. It is also evident that social support from superiors assists in reducing job dissatisfaction, leading to greater happiness at work (Ko et al. 2015). Similarly, a study conducted in a Singaporean public hospital identified that supportive supervision from managers improved immigrant nurses’ job satisfaction, and decreased their intention to resign (Goh and Lopez 2016). As illustrated by Ko et al. (2015), support from co-workers and colleagues increases immigrants’ job satisfaction by boosting their sense of belonging, and feeling respected. These findings demonstrate that quality work relationships with superiors and co-workers are important in developing and maintaining satisfaction among immigrants, as these relationships may make immigrants feel accepted, included, valued, and respected (Ko et al. 2015).

3.2 Job Characteristics

In addition to the aforementioned environmental factors that are relevant to the workplace climate, atmosphere, culture, or system, the literature has documented other work-specific characteristics that may affect an individual’s job satisfaction (Arvey et al. 1991; Loher et al. 1985). The mechanism of how job characteristics are linked to job satisfaction may be that job characteristics lead employees to perceive meaningfulness in their work, and to gain a sense of responsibility, both of which are potential sources of workplace well-being (Loher et al. 1985). While the effects of job characteristics and the associated mechanisms may be applied widely to various population groups, the evidence implies that, whether or not work-related characteristics affect job satisfaction, and how, can vary according to the workers’ background (i.e., race and birthplace) (Magee and Umamaheswar 2011). Although the antecedents of job satisfaction have been well reflected in the theoretical model (Oldham and Hackman 2005), there are only a limited number of studies that concentrate on factors that foster migrant workers’ job satisfaction. In this section, we delineate the four main factors presented in the current literature: salary, job demands, job control, or autonomy, and learning opportunities in the job position.

Salary is the reward of work duties, responsibilities, and achievements, and it is one of the major factors that influences employees’ job satisfaction (Gazioglu and Tansel 2006). Existing research has found that there is a significant and positive link between wage levels and job satisfaction (French and Lam 1988; Itzhaki et al. 2013). Generally, a higher rate of pay leads to higher job satisfaction. A study that explored job satisfaction among immigrant nurses in Israel and the U.S. showed that the nurses’ job satisfaction was positively correlated with salary. However, the strength of the salary–job satisfaction relationship depends on certain other factors. For example, if there is a massive salary discrepancy between the origin country and the host country, that is, if the salary in the host country is significantly higher than the origin country, immigrant nurses will experience higher job satisfaction (Itzhaki et al. 2013).

Job demands reflect the level of skill and physical power needed to fulfill the specifications of an occupation, or the requirements of the tasks at work (Itzhaki et al. 2013; Magee and Umamaheswar 2011). Job demands do not necessarily have a negative influence on an individual’s job satisfaction. However, if meeting the job requires great effort, it may turn job demands into job stressors, and ultimately lead to decreased satisfaction at work (Schaufeli and Bakker 2004). This appears to be true in the immigrant context. For instance, empirical research has found that immigrant workers exhibit significantly decreased job satisfaction when job demands arise, and this negative effect of job demands tends to be greater for immigrant workers than it is for their local counterparts (Itzhaki et al. 2013; Magee and Umamaheswar 2011).

Job control is an individual’s ability to exert influence and control over their work environment, such as the initiation, termination, and resumption of a task, to create a more rewarding and less threatening work environment (Ganster 1989; Magee and Umamaheswar 2011). Job autonomy might be seen as a specialized form of job control. It is the freedom that an individual has in choosing what to do in the workplace, and how to do it (Clark 2001). De Lange et al. (2004) found that providing employees control over their job increases their job satisfaction. Specifically, for immigrant workers, studies have identified that immigrant workers with higher job satisfaction usually have more control over their jobs and more autonomy at work (Itzhaki et al. 2013; Ko et al. 2015; Magee and Umamaheswar 2011).

Learning opportunities are when an employer provides employees the chance to learn new knowledge and skills to assist their career development (Acker 2004; Ko et al. 2015). Previous studies verify that professional learning opportunities are an important factor that positively affects job satisfaction. Learning opportunities at work are considered a part of the reward of the job, and may facilitate an employee’s career advancement (Acker 2004; Kraimer et al. 2011). A study on migrant workers in the U.S. discovered that, if the employing organization provides adequate opportunities for learning and career development, immigrant employees feel considerably happier at work (Ko et al. 2015).

3.3 Work-Specific Personal Factors

Work-specific personal factors may not be independent from the work environment and the job properties—given that some personal attributes might be shaped by these two aspects. In view of the literature, we argue that work-related personal factors are the third major category of antecedents of job satisfaction. Work-specific individual factors are the features of the workers themselves. These features affect immigrant workers’ job satisfaction mainly due to their ability to influence the workers’ professional development and workplace performance across different stages (Dugguh and Dennis 2014; Erdogan et al. 2011; Fairbrother and Warn 2003). From the current literature that focuses on migrant workers, we have identified three groups of work-related personal factors that affect job satisfaction.

3.3.1 Competency-Related Factors

Overeducation and overskilling are when workers have educational backgrounds or skills higher than those required in their jobs. The relationship between overeducation or overskilling and job satisfaction among migrant workers is currently inconclusive. McGuinness and Byrne (2014) found that some immigrant workers who were perceived to be overeducated and overskilled for their jobs in the host country experienced low job satisfaction; however, low job satisfaction was not observed in other overeducated or overskilled migrant workers. This may be because, in certain cases, workers who are overeducated or overskilled may be able to complete tasks better and faster than workers without the same or similar levels of education or skills. This may, to some extent, reduce the negative psychological experiences caused by the mismatch between the immigrants’ skills and the job requirements. Therefore, the authors argued that the roles of overeducation and overskilling in affecting job satisfaction are compensated by other factors, such as increased job security, and greater work–life balance (McGuinness and Byrne 2014).

Re-education, or further education, is a person’s choice to undertake education higher than their present qualifications. The need for re-education may be due to an employee having an educational background that is considered to mismatch, or be below, the requirements of their current job. Re-education helps employees to update or refresh the knowledge they already have, as well as gain new knowledge and skills, leading to an increase in job satisfaction through enabling workers to better perform their duties (Chuba 2016; Ong and Shah 2012). This is particularly important for migrant workers who may need to go through different and complex processes to have their prior qualifications and experience recognized in their host country. Re-education may provide migrants with the opportunity to gain necessary skills or qualifications that fit their jobs and careers in the host country. It has been confirmed that re-education and further education are factors that can profoundly affect immigrant workers’ job satisfaction (Chuba 2016; Ong and Shah 2012).

Occupational mobility refers to the ease of switching career fields or jobs (Rooth and Ekberg 2006). As discussed in many prior studies, occupational mobility is a direct factor affecting job satisfaction (Covington-Ward 2016). Indeed, many immigrants consider their first job in their host country as a stepping stone, or transitional job, from which they can further their vocational development (Paul 2011). Being able to move to a new career is crucial for migrants to survive in new work and life environments. Empirically, a study by Covington-Ward (2016) showed that occupational mobility can explain a significant variance in migrants’ job satisfaction.

3.3.2 Work-Related Psychological States

Stress refers to feelings of strain, tension, and pressure (Taylor and Sirois 1995). These feelings can be triggered in employees who experience difficulty in meeting the requirements of their work, or adapting to a new environment (Cohen et al. 2007). A study by Blegen (1993) reveals that stress has a strong, negative association with job satisfaction. Research on migrant workers is in line with empirical evidence observed in general workers, suggesting that perceived stress in the workplace has negative effects on immigrant employees’ job satisfaction (An et al. 2016; Magee and Umamaheswar 2011).

Organizational commitment consists of three dimensions: affective commitment, continuance commitment, and normative commitment (Cohen 2007). Affective commitment captures how much an employee is emotionally attached to an organization. Continuance commitment concerns the costs to an employee associated with leaving the organization. Normative commitment is characterized by an employee’s feeling of obligation to continue their employment (Meyer and Allen 1999). A meta-analysis conducted by Meyer et al. (2002) showed that continuance commitment correlates weakly with job satisfaction and, therefore, they concluded that it is usually not considered a factor that positively contributes to job satisfaction. However, affective and normative commitment have been found to correlate positively with job satisfaction (Meyer et al. 2002). Researchers focusing on the migrant group have also anticipated similar results. As expected, empirical studies have shown that immigrant workers’ job satisfaction is positively related to affective and normative commitment (Cabaj 2008).

3.3.3 Work-Specific Characteristics

Organizational tenure is the length of employment in a particular organization (Ng and Feldman 2010). The tenure within an organization is observed to be associated with increased affective commitment (Cabaj 2008), and might be regarded as a reflection of an employee’s satisfaction in the workplace (Budihardjo 2013). A study on Chinese immigrant workers in Australia identified that an extension of organizational tenure improved their job satisfaction (Lu et al. 2012).

Professional status, or professional level, is the position, rank, or social standing associated with a profession in society (Hoyle 2001). Workers with a higher professional status may have stronger beliefs that their work is important and meaningful and, thus, have a greater tendency to experience job satisfaction (Bloemen 2014; Hoyle 2001; Itzhaki et al. 2013). Several studies report that immigrant workers who are in a high professional status or level are more satisfied with their jobs (Bloemen 2014; Itzhaki et al. 2013).

4 Non-work-Specific Factors

Migration is a considerable move for most migrants—many go through a stressful process of adaptation and experience various challenges (Khawaja et al. 2016), such as acculturation (Berry 2005), underemployment (De Castro et al. 2010), difficulty integrating into the local workforce (Hakak et al. 2010), and over-qualification (Galarneau and Morissette 2009). Within this context, after experiencing difficulties resulting from migration, many immigrants may more easily lower their job expectations, compared to their local counterparts (Ong and Shah 2012). Meanwhile, changing work requirements in the host country’s labor market may also create barriers for new immigrants, causing them to experience lower job satisfaction than local employees (Yap et al. 2014). In this section, we elaborate on non-work-specific factors from three categories: general demographics, culture-related factors, and society- or community-related factors.

4.1 General Demographics Factors

Immigrants’ demographic characteristics, such as age, gender, cultural background, race, and length of time in the host country, have been widely studied in relation to their satisfaction at work (Mok and Finley 1986). For instance, in a study of seven groups of immigrants who originated from countries other than Canada, Magee and Umamaheswar (2011) found that job satisfaction levels were significantly influenced by the cultural background of the immigrants’ home countries. Immigrants from different countries may choose different reference systems to assess their job satisfaction levels, and this is consistent with social comparison theory (Deaux 2000; Tajfel 1981). This also suggests that immigrants from diverse backgrounds who are engaged in the same occupation or profession may have differing levels of job satisfaction. Ko et al. (2015) examined immigrant background status as a boundary condition moderating the relationship between job conditions and job satisfaction among immigrants in the U.S. Itzhaki et al. (2013) found that personal variables have different effects on immigrants’ perceptions of job satisfaction among former Soviet Union-registered nurses in Israel and Filipino-registered nurses in the U.S. Townsend et al. (2014) found that skilled migrants in Australia experienced underemployment or mismatches between their jobs and their qualifications that could also be sources of low job satisfaction.

Previous research on migrants’ well-being has shown that the length of residency in the host country has a positive effect on life satisfaction, and also has a positive influence on immigrants’ desired psychological states (Khawaja et al. 2016). This phenomenon could be explained by the fact that, the longer the duration of stay in the host country, the better adaptation migrants could achieve, through learning the language, acculturating to norms and values, and integrating well into local life (De Castro et al. 2008). For example, Kifle et al. (2016) revealed that the magnitude score of satisfaction for immigrants in Australia could be improved by extending their length of stay. New immigrants have lower job satisfaction, but the satisfaction score gap between immigrants and local workers lessens over time. Similar results have been found among migrant dentists in Australia (Balasubramanian et al. 2016). It is also reported that immigrants may have to spend more than 10 years in the host country to narrow the job satisfaction gap (Yap et al. 2014).

Age and years of residency in the host country are significant predictors of overall job satisfaction, evidenced by their correlations with job satisfaction shown in empirical studies (Ea et al. 2008). Studies have found that older immigrants tended to have high job satisfaction. A major reason for this tendency is that the initial adverse scenarios (e.g., language barrier, underemployment, overqualification) experienced by immigrants can be reduced, or alleviated, over time through the immigrants’ progressive adaptation to the host society (Chuba 2016). This is also consistent with previous research that found that job satisfaction significantly improved with the increase in age of immigrants (Fugl-Meyer et al. 2002).

Gender difference also plays an important role in influencing migrant workers’ job satisfaction. For example, Au et al. (1998) found that Chinese male restaurant workers in New York reported a higher level of job satisfaction compared to their female counterparts. Ong and Shah (2012) illustrated that gender is an important consideration when differentiating local and immigrant workers, in terms of the relationship between language proficiency and job satisfaction. A further indicator in the literature is that males and females have different work expectations, career goals, and roles. For example, studies have found that, compared to males, female immigrants perceive higher depression due to their multiple roles at work and at home (Remennick 2005). Another study demonstrated that the gender–job satisfaction paradox exists in the labor market due to the restrictive access for females or males in some occupations (Kaiser 2007).

4.2 Culture-Related Factors

During the process of adapting to their host countries, international immigrants may encounter many culture-related barriers that arise from language, values, and acculturation strategy. Language is a typical indication of cultural identification (Lee 2002), and studies have been conducted on its influence on immigrants’ job satisfaction (Bloemen 2013; Hakak et al. 2010; Pottie et al. 2008). Research has found that immigrants who cannot speak the language of the host country tend to have lower job satisfaction (Bloemen 2014). An individual’s values, beliefs, and other traits that are closely related to their cultural background, may also be contributing factors when immigrants subjectively appraise their jobs (e.g., whether they are satisfied or not), given that variations in cultural traits may lead immigrants to value different aspects of a job (Kirkman and Shapiro 2001). Further, in the acculturation process, the interaction between the heritage culture and the receiving culture may lead to unpleasant outcomes, such as misunderstanding, discrimination, and conflict that can cause health and psychosocial problems among immigrants, including low job satisfaction (Schwartz et al. 2010). We discuss each of these three factors below.

4.2.1 Language Skills

An inability to speak the language of the host country is an obvious barrier for migrants seeking jobs (Kossoudji 1988). Immigrants who lack local language proficiency may feel isolated, and find it difficult to expand their social network, as they are unable to effectively communicate with local residents. Insufficient language skills can also lead to difficulty for immigrants in re-establishing their careers in the host country. A study by Hakak et al. (2010) of Latin Americans in Canada, found that speaking English as a second language was a constraint for non-native speakers that affected their confidence in the workplace. Conversely, a high level of proficiency in the local language can positively contribute to immigrant workers’ job satisfaction. Green et al. (2007) found that immigrants from English-speaking backgrounds earn higher salaries or income, compared to migrants from non-English-speaking backgrounds, and income is a critical contributor of job satisfaction (Judge et al. 2010). The literature has also shown that employers in host countries prefer to hire, or give preferential treatment to, immigrant workers with higher levels of local language skills (Hainmueller and Hopkins 2015). These immigrants may then experience more positive job outcomes (e.g., immigrants with better language skills may be more satisfied at work). These findings suggest that language skills are a non-negligible determinant of immigrants’ job satisfaction.

4.2.2 Cultural Traits

Most immigrants moving to new host countries are motivated by better life or work opportunities. The diverse cultural backgrounds of their home countries have shaped immigrants’ values and work expectations, and these are critical factors in driving their career development paths (Brown 2002). According to Brown (2002), cultural values not only play a significant role in an individual’s career choice and job satisfaction, they also interact with other factors, such as gender, self-efficacy, and social support, to influence work-related outcomes. For example, immigrants from different cultural backgrounds have distinct job expectations, job-seeking attitudes, and work behaviors. This view is supported by findings that immigrants from developing Southeast Asia, who have poor education levels or English-speaking skills, may choose low-skilled jobs but have higher job satisfaction compared with highly skilled migrants (Townsend et al. 2014).

4.2.3 Acculturation

When immigrants move to their host countries, they often experience a series of complex changes they must adapt to in their new lives. Research on various immigrant groups has found that, while some individuals adapt very well to their host society, others encounter many difficulties (Berry 1992; Cerdin et al. 2014). Conflict between a person’s traditional culture and the mainstream host culture is a major challenge, forcing immigrants to choose suitable strategies to conquer the difficulties that are caused by such conflicts (Lu et al. 2011).

Acculturation has been used to describe the adjustment process of becoming culturally and psychologically involved in intercultural contact (Berry et al. 2006). According to the framework of acculturation (Berry 2001), there are four aspects of acculturation strategies that immigrants can apply when settling in the host society. These strategies include assimilation, integration, separation, and marginalization (Berry 1997). Assimilation strategy fosters an individual’s openness to encompass the host culture instead of maintaining their own heritage. Conversely, separation strategy is applied when individuals insist on holding onto their traditional culture, and refuse to engage with the mainstream culture. Integration strategy provides the option for individuals to absorb their new host culture as well as maintain their own culture. Finally, marginalization concerns a point when individuals lose interest in either retaining their original culture or accepting the host culture. Immigrants from different backgrounds have distinct preferences in their selection of acculturation strategies during the process of adaptation to their host countries. For example, Chinese immigrants in Australia prefer to retain their traditional culture rather than embrace the culture of their host country (Lu et al. 2011).

Previous studies that examine the influence of acculturation on job-related outcomes among various immigrant groups reveal that acculturation has a positive effect on job satisfaction. For example, Au et al. (1998) found that acculturation was positively related to job satisfaction among Chinese immigrants in the U.S. In another study, Valdivia and Flores (2012) found that Anglo-American acculturation had a positive affect on job satisfaction among Latin American immigrants in the U.S. Similarly, Ea et al. (2008) reported that, acculturation to the host culture among registered nurses with a Filipino background in the U.S., had a positive correlation with job satisfaction. These findings are in accordance with the argument of Kifle et al. (2016) that immigrants’ lack of assimilation with Australian culture leads to a lower level of job satisfaction.

These studies are all focused on the effect of a single acculturation strategy, such as assimilation or integration, on job satisfaction. The acculturation process reflects the interaction between the original and the host cultures. Immigrants may utilize different strategies during the course of adaptation. For example, some immigrants may not be willing to interact with mainstream cultures when they perceive prejudice or discrimination. After a longer period living in the host country, immigrants may be more interested in learning the norms and traditions of the local society (Berry 2001).

4.3 Society- and Community-Related Factors

Social network refers to individuals’ interpersonal relations, consisting of social interactions and access to resources (Sparrowe et al. 2001). Apart from seeking information and advice from colleagues—the social support in the workplace discussed earlier in this paper—individuals can obtain support or resources through interactions with social networks outside work contexts. These include family members, friends, neighbours, acquaintances, and significant others (Cross and Cummings 2004; Hakak et al. 2010). Social networks can enhance an immigrant’s sense of belonging and feeling of being respected, through bridging individuals with relatively remote relations (e.g., acquaintances, but not close friends), and bonding more proximal relations (e.g., friendship and family ties). Social networks have been identified as an important determinant of high performance in the workplace (Mehra et al. 2001; Morrison 2002), a potential source of job satisfaction. However, in a broader career or professional context, beyond the immediate work context, immigrants can find it difficult to establish local professional networks in the host country, and this may limit their sources for job opportunities (Hakak et al. 2010). Social networks can provide useful information and support that may help to relieve stress during the job-seeking process, in turn, affecting immigrants’ satisfaction at work and in their careers.

There are many other factors that may affect job satisfaction among immigrants. For instance, general attitudes toward immigrants in host countries can shape their psychological feelings, including job satisfaction. Immigrants may perceive acceptance, appreciation, or concern, all of which are correlated to immigrants’ integration into the diverse domains of local society, including the work domain (Esses et al. 2006). Research has found that prejudice and discrimination inside and outside the workplace can negatively affect immigrant workers’ happiness at work (Hakak et al. 2010). Immigrants also reported that local employers might lack trust in the qualifications immigrants had gained overseas (Townsend et al. 2014). Indeed, studies have shown that discrimination against job applications lodged by migrants is common in many host countries such as the U.S., Canada, Germany, Australia, and Austria (Dancygier and Laitin 2014; Weichselbaumer 2016). From a broader perspective, this may imply that such discrimination may have an early effect on immigrants’ satisfaction with their job application, while further investigation is warranted to explore whether the discrimination experienced by successful immigrant applicants is related to their job satisfaction after entering the organization. Overall, the celebration and acceptance of diversity, and openness to immigrants in the host country, will lead immigrants to experience higher levels of job and life satisfaction (Ward and Masgoret 2008).

5 Potential Interactions

This review has illustrated that a number of work-related factors and non-work-specific factors are responsible for the variation in immigrant workers’ job satisfaction. Although we might imagine work-specific factors are more proximal to a person’s job, given the special circumstances immigrants are confronted with, we argue that both work-related factors and non-work-specific factors tend to be equally important in determining immigrant workers’ job satisfaction. From the person–environment perspective, researchers have warned that it is unwise to conclude whether one type of factor is more important than the other (Pervin 1987). Person–environment congruence is achieved through the interaction between personal factors and environmental factors, and is an ideal state that human beings generally want to pursue (Arvey et al. 1991). As mentioned earlier, individuals often purposefully choose the work environment that best represents the attributes and characteristics that are the same or similar to their own, to proactively improve their happiness at work (Weiss and Adler 1984). As a result, the main form of interaction of the factors influencing job satisfaction, as discussed by Arvey et al. (1991), is through achieving congruence. However, as migration to another county is a significant life event, it may cause many maladjustments due to the initial mismatch between personal and environmental or situational factors that can lower an immigrant’s level of happiness (Al-Baldawi 2002; Kamal et al. 2013).

The way in which job satisfaction can be shaped through person–environment interaction has been studied extensively in the general population. However, among immigrant workers, this area has not received much attention. In alignment with the interaction model of Arvey et al. (1991), we have highlighted some of the factors that may interact to promote immigrants’ job satisfaction. First, the interaction between work-related situational factors and personal factors may influence job satisfaction. For example, when positive job characteristics (e.g., Judge et al. 2000; Loher et al. 1985) or a positive work environment (e.g., Arvey et al. 1989; Baernholdt and Mark 2009; Begat et al. 2005) are accompanied by the qualifications or skills that can be applied to the workplace, immigrants may experience increased job satisfaction (e.g., Allen and Van der Velden 2001; Vieira 2005). Second, in a non-work setting, personal and situational factors may interact to influence job satisfaction. For instance, when immigrants’ cultural backgrounds or values are better aligned with those endorsed in the local social environment, we may expect immigrant workers to have a heightened level of job satisfaction, as the special status of immigrants may cause them to psychologically link their experiences in the community to those in the workplace (Adams et al. 1996; Brown 2002). Third, non-work personal factors and work-related situational factors may jointly produce influence (Roelen et al. 2008; Smerek and Peterson 2007). Whether or not an immigrant’s job satisfaction is influenced by inadequate language skills—a general personal factor not specific to the work context—may be dependent on their job responsibilities and duties. When the job requires no, or very limited, interpersonal communication using the specified language, an immigrant’s job satisfaction may not be affected by poor language skills. Conversely, if an immigrant is required to communicate extensively using the specified language, the lack of language skills may be a problem that causes job dissatisfaction. Fourth, the interaction between a work-related personal factor and a non-work situational factor may exert influence on job satisfaction (Flap and Völker 2001; Harris et al. 2007). For example, an immigrant’s perception that they are overqualified for the job, a work-related personal factor, may lead them to feel dissatisfied when performing tasks. However, if the host country initiates new policies to introduce more immigrants, the existing immigrants’ dissatisfaction may decrease to some extent, as they may realize that the job market will become more competitive, and they may be uncertain that they will find a better job. In line with the interaction model of Arvey et al. (1991), these potential interactions may lead to a change in job satisfaction among immigrants. The structural interactions elaborated above may provide useful guidelines to future research regarding the development of theoretical framework of job satisfaction. Future research may focus on the joint influences of the determinants discussed in this study to gain further insights into the nature of job satisfaction, and as an extension, of other subjective reactions to the job. When person–environment congruence is reached, we observe increased job satisfaction. Adversely, if there is person–environment incongruence, this will result in decreased job satisfaction. Given that these interaction effects on job satisfaction are based on the theoretical perspective, future research is needed to test these effects using immigrant samples.

6 Implications, Limitations, and Future Research

This article contributes to our understanding of the factors that shape immigrants’ job satisfaction, including work-related and non-work-specific factors, as well as interactional perspectives. The relatively comprehensive picture we have depicted for the determinants of immigrants’ satisfaction at work offers useful information for organizations, communities, and migration policy-makers in host countries. It is important that employers understand the work-related factors that affect the job satisfaction of employees with an immigration background. The growing number of immigrants, especially skilled migrant workers, has accounted for a big part of the labor force in many traditional immigration countries (Yap et al. 2014). Many of these immigrants are likely to have higher education levels compared to their local counterparts, and have higher expectations of career development and workplace well-being. However, skilled immigrants often encounter barriers to fulfilling their expertise and utilizing their capabilities when they enter the local labor market. Being aware of the influential factors of job satisfaction enables employers to create fair and equitable work environments, which will benefit both organizations and employees as job satisfaction can also increase task performance and prevent turnover intention (Gazioglu and Tansel 2006; Ng and Feldman 2010).

Additionally, the findings we have synthesized in this article offer valuable implications for community management. Research has identified that non-work-specific factors (e.g., social or community support, cultural traits, and acculturation) have significant correlations with immigrants’ job satisfaction. Understanding which factors contribute to the job satisfaction of immigrants is critical for establishing healthy communities that involve immigrants (Valdivia and Flores 2012). It is practical that host communities focus their efforts on the development of a peaceful and friendly multicultural environment, and provide support and help for immigrants to adapt. Such an environment has positive effects on immigrants’ life well-being, and has been found to contribute significantly to workplace well-being, such as job satisfaction (Judge and Watanabe 1993; Loscocco and Roschelle 1991).

This article has a number of restrictions. First, due to the limited research that has investigated facets of immigrant workers’ job satisfaction, we were unable to conduct a more comprehensive and extensive analysis of how the influential factors (e.g., pay, work conditions, and job duties) could affect different dimensions of job satisfaction. Second, existing research that has investigated person–environment fit mainly focuses on general workers, and only a few studies are specifically conducted on immigrant workers. Consequently, we could not explore further the interactions between personal and environmental factors, and how the interactions influence migrants’ job satisfaction. The proposed interactions in this article were mostly driven by theoretical and conceptual inferences. Third, there has been little research to investigate self-employed immigrants’ satisfaction with their own jobs (e.g., private business) in the host countries. As a result, we could not expand further on exactly which work-related factors drive immigrants’ job satisfaction. Fourth, participants taking part in past research mostly migrated from developing countries to developed countries. Few studies have researched immigrant workers that move from developed countries to developing countries. This phenomenon existing in the literature has prevented us from drawing a solid conclusion, particularly regarding the influence of societal or other non-work-related situational factors on immigrants’ job satisfaction.

Due to these shortcomings in the current area, there are still a number of opportunities for future research. For example, because of the limited research on self-employed immigrants, it would be valuable to explore the reasons that motivate immigrants who do not have self-employment experience to start their own business in their host countries, and whether or not, and why, they are satisfied or dissatisfied in their current business. In addition, most of the studies on acculturation were focused on the unidirectional assimilation of the minority (immigrants) by the majority (local residents). In fact, some organizations are hiring more immigrant workers than local workers, and many local residents are working for companies operated by immigrants (Åslund et al. 2014). In these circumstances, it may be worth exploring the reverse direction of acculturation and its relationship with job satisfaction status. Further, it would be useful to investigate the job satisfaction of immigrant workers who migrate from developed countries to developing countries, considering this phenomenon is rarely documented in current literature. Finally, since a limited number of studies have emphasized how the fit between the person and the environment shapes migrant workers’ job satisfaction, future research may devote more efforts to expanding our knowledge in this area.

References

Acker, G. M. (2004). The effect of organizational conditions (role conflict, role ambiguity, opportunities for professional development, and social support) on job satisfaction and intention to leave among social workers in mental health care. Community Mental Health Journal, 40(1), 65–73.

Adams, G. A., King, L. A., & King, D. W. (1996). Relationships of job and family involvement, family social support, and work–family conflict with job and life satisfaction. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81(4), 411–420.

Al-Baldawi, R. (2002). Migration-related stress and psychosomatic consequences. Paper presented at the international congress series (Vol. 1241, pp. 271–278). doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0531-5131(02)00649-0.

Allen, J., & Van der Velden, R. (2001). Educational mismatches versus skill mismatches: Effects on wages, job satisfaction, and on-the-job search. Oxford Economic Papers, 53(3), 434–452.

An, J. Y., Cha, S., Moon, H., Ruggiero, J. S., & Jang, H. (2016). Factors affecting job satisfaction of immigrant Korean nurses. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 27(2), 126–135.

Arvey, R. D., Bouchard, T. J., Segal, N. L., & Abraham, L. M. (1989). Job satisfaction: Environmental and genetic components. Journal of Applied Psychology, 74(2), 187–192.

Arvey, R. D., Carter, G. W., & Buerkley, D. K. (1991). Job satisfaction: Dispositional and situational influences. In C. L. Cooper & I. T. Robertson (Eds.), International review of industrial and organizational psychology (Vol. 6, pp. 359–383). New York, NY: Wiley.

Åslund, O., Hensvik, L., & Skans, O. N. (2014). Seeking similarity: How immigrants and natives manage in the labor market. Journal of Labor Economics, 32(3), 405–441.

Au, A., Garey, J., Bermas, N., & Chan, M. (1998). The relationship between acculturation and job satisfaction among Chinese immigrants in the New York city restaurant business. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 17(1), 11–21.

Aziri, B. (2011). Job satisfaction: A literature review. Management Research and Practice, 3(4), 77–86.

Baernholdt, M., & Mark, B. A. (2009). The nurse work environment, job satisfaction and turnover rates in rural and urban nursing units. Journal of Nursing Management, 17(8), 994–1001.

Balasubramanian, M., Spencer, A. J., Short, S. D., Watkins, K., Chrisopoulos, S., & Brennan, D. S. (2016). Job satisfaction among ‘migrant dentists’ in Australia: Implications for dentist migration and workforce policy. Australian Dental Journal, 61(2), 174–182.

Begat, I., Ellefsen, B., & Severinsson, E. (2005). Nurses’ satisfaction with their work environment and the outcomes of clinical nursing supervision on nurses’ experiences of well-being—A Norwegian study. Journal of Nursing Management, 13(3), 221–230.

Berry, J. W. (1992). Acculturation and adaptation in a new society. International Migration, 30(s1), 69–85.

Berry, J. W. (1997). Immigration, acculturation, and adaptation. Applied Psychology, 46(1), 5–34.

Berry, J. W. (2001). A psychology of immigration. Journal of Social Issues, 57(3), 615–631.

Berry, J. W. (2005). Acculturation: Living successfully in two cultures. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 29(6), 697–712.

Berry, J. W., Phinney, J. S., Sam, D. L., & Vedder, P. (2006). Immigrant youth: Acculturation, identity, and adaptation. Applied Psychology, 55(3), 303–332.

Blegen, M. A. (1993). Nurses’ job satisfaction: A meta-analysis of related variables. Nursing Research, 42(1), 36–41.

Bloemen, H. (2013). Language proficiency of migrants: The relation with job satisfaction and matching. St. Louis: Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis. Retrieved from https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.lib.rmit.edu.au/docview/1698648485?accountid=13552.

Bloemen, H. (2014). Language proficiency of migrants: The relation with job satisfaction and skill matching. Tinbergen Institute Discussion Paper 14-148/V. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2523933, doi:10.2139/ssrn.2523933.

Braun, S., Peus, C., Weisweiler, S., & Frey, D. (2013). Transformational leadership, job satisfaction, and team performance: A multilevel mediation model of trust. The Leadership Quarterly, 24(1), 270–283.

Brown, D. (2002). The role of work and cultural values in occupational choice, satisfaction, and success: A theoretical statement. Journal of Counseling and Development, 80(1), 48–56.

Budihardjo, A. (2013). The relationship between job satisfaction, affective commitment, organizational learning climate and corporate performance. GSTF Business Review (GBR), 2(4), 58–64.

Cabaj, J. (2008). Job satisfaction, turnover intentions, and organizational commitment in immigrant and non-immigrant groups. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global.

Cerdin, J.-L., Diné, M. A., & Brewster, C. (2014). Qualified immigrants’ success: Exploring the motivation to migrate and to integrate. Journal of International Business Studies, 45(2), 151–168.

Chowhan, J., Zeytinoglu, I. U., & Cooke, G. B. (2016). Immigrants and job satisfaction: Do high performance work systems play a role? Economic and Industrial Democracy, 37(4), 690–715.

Chuba, B. (2016). Perceptions of job satisfaction and over-qualification among African immigrants in Alberta, Canada (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/openview/94a390b560ff776c90f8755bcadbfc3b/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y.

Clark, S. C. (2001). Work cultures and work/family balance. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 58(3), 348–365.

Cohen, A. (2007). Commitment before and after: An evaluation and reconceptualization of organizational commitment. Human Resource Management Review, 17(3), 336–354.

Cohen, S., Janicki-Deverts, D., & Miller, G. E. (2007). Psychological stress and disease. Jama, 298(14), 1685–1687.

Cojuharenco, I., Patient, D., & Bashshur, M. R. (2011). Seeing the “forest” or the “trees” of organizational justice: Effects of temporal perspective on employee concerns about unfair treatment at work. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 116(1), 17–31.

Covington-Ward, Y. (2016). African immigrants in low-wage direct health care: Motivations, job satisfaction, and occupational mobility. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 19(3), 709–715.

Cross, R., & Cummings, J. N. (2004). Tie and network correlates of individual performance in knowledge-intensive work. Academy of Management Journal, 47(6), 928–937.

Dancygier, R. M., & Laitin, D. D. (2014). Immigration into Europe: Economic discrimination, violence, and public policy. Annual Review of Political Science, 17, 43–64.

De Castro, A., Gee, G. C., & Takeuchi, D. T. (2008). Job-related stress and chronic health conditions among Filipino immigrants. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 10(6), 551–558.

De Castro, A., Rue, T., & Takeuchi, D. T. (2010). Associations of employment frustration with self-rated physical and mental health among Asian American immigrants in the US labor force. Public Health Nursing, 27(6), 492–503.

De Haas, H. (2010). Migration and development: A theoretical perspective. International Migration Review, 44(1), 227–264.

De Lange, A. H., Taris, T. W., Kompier, M. A., Houtman, I. L., & Bongers, P. M. (2004). The relationships between work characteristics and mental health: Examining normal, reversed and reciprocal relationships in a 4-wave study. Work and Stress, 18(2), 149–166.

Deaux, K. (2000). Surveying the landscape of immigration: Social psychological perspectives. Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology, 10(5), 421–431.

Dugguh, S. I., & Dennis, A. (2014). Job satisfaction theories: Traceability to employee performance in organizations. Journal of Business and Management, 16(5), 11–18.

Ea, E. E., Griffin, M. Q., L’eplattenier, N., & Fitzpatrick, J. J. (2008). Job satisfaction and acculturation among Filipino registered nurses. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 40(1), 46–51.

Ensher, E. A., Grant-Vallone, E. J., & Donaldson, S. I. (2001). Effects of perceived discrimation on job satisfaction, organizational commitment, organizational citizenship behavior, and grievances. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 12(1), 53–72.

Erdogan, B., Bauer, T. N., Peiro, J., & Truxillo, D. M. (2011). Overqualified employees: Making the best of a potentially bad situation for individuals and organizations. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 4(2), 215–232.

Esses, V. M., Wagner, U., Wolf, C., Preiser, M., & Wilbur, C. J. (2006). Perceptions of national identity and attitudes toward immigrants and immigration in Canada and Germany. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 30(6), 653–669.

Fairbrother, K., & Warn, J. (2003). Workplace dimensions, stress and job satisfaction. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 18(1), 8–21.

Findlay, A. M., & Nowok, B. (2012). The uneven impact of different life domains on the wellbeing of migrants. Centre for population change working paper No. 26.

Flap, H., & Völker, B. (2001). Goal specific social capital and job satisfaction: Effects of different types of networks on instrumental and social aspects of work. Social Networks, 23(4), 297–320.

French, C., & Lam, Y. (1988). Migration and job satisfaction—A logistic regression analysis of satisfaction of Filipina domestic workers in Hong Kong. Social Indicators Research, 20(1), 79–90.

Fu, W., & Deshpande, S. P. (2014). The impact of caring climate, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment on job performance of employees in a China’s insurance company. Journal of Business Ethics, 124(2), 339–349.

Fugl-Meyer, A. R., Melin, R., & Fugl-Meyer, K. S. (2002). Life satisfaction in 18-to 64-year-old Swedes: In relation to gender, age, partner and immigrant status. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine, 34(5), 239–246.

Galarneau, D., & Morissette, R. (2009). Immigrants’ education and required job skills. Perspectives on Labour and Income, 21(1), 5–18.

Ganster, D. (1989). Measurement of worker control. Final report to the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Contract No. 88-187.

Gazioglu, S., & Tansel, A. (2006). Job satisfaction in Britain: Individual and job related factors. Applied Economics, 38(10), 1163–1171.

Goh, Y. S., & Lopez, V. (2016). Job satisfaction, work environment and intention to leave among migrant nurses working in a publicly funded tertiary hospital. Journal of Nursing Management, 24(7), 893–901.

Green, C., Kler, P., & Leeves, G. (2007). Immigrant overeducation: Evidence from recent arrivals to Australia. Economics of Education Review, 26(4), 420–432.

Hainmueller, J., & Hopkins, D. J. (2015). The hidden American immigration consensus: A conjoint analysis of attitudes toward immigrants. American Journal of Political Science, 59(3), 529–548.

Hakak, L. T., Holzinger, I., & Zikic, J. (2010). Barriers and paths to success: Latin American MBAs’ views of employment in Canada. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 25(2), 159–176.

Harris, J. I., Winskowski, A. M., & Engdahl, B. E. (2007). Types of workplace social support in the prediction of job satisfaction. The Career Development Quarterly, 56(2), 150–156.

Hombrados-Mendieta, I., & Cosano-Rivas, F. (2013). Burnout, workplace support, job satisfaction and life satisfaction among social workers in Spain: A structural equation model. International Social Work, 56(2), 228–246.

Hoyle, E. (2001). Teaching prestige, status and esteem. Educational Management and Administration, 29(2), 139–152.

Itzhaki, M., Ea, E., Ehrenfeld, M., & Fitzpatrick, J. (2013). Job satisfaction among immigrant nurses in Israel and the United States of America. International Nursing Review, 60(1), 122–128.

Jiang, Z., & Hu, X. (2016). Knowledge sharing and life satisfaction: The roles of colleague relationships and gender. Social Indicators Research, 126(1), 379–394.

Jones, A. P., & James, L. R. (1979). Psychological climate: Dimensions and relationships of individual and aggregated work environment perceptions. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 23(2), 201–250.

Judge, T. A., Bono, J. E., & Locke, E. A. (2000). Personality and job satisfaction: The mediating role of job characteristics. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(2), 237–249.

Judge, T. A., & Hulin, C. L. (1993). Job satisfaction as a reflection of disposition: A multiple source causal analysis. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 56(3), 388–421.

Judge, T. A., Piccolo, R. F., Podsakoff, N. P., Shaw, J. C., & Rich, B. L. (2010). The relationship between pay and job satisfaction: A meta-analysis of the literature. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 77(2), 157–167.

Judge, T. A., & Watanabe, S. (1993). Another look at the job satisfaction-life satisfaction relationship. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78(6), 939–948.

Kaiser, L. C. (2007). Gender-job satisfaction differences across Europe: An indicator for labour market modernization. International Journal of Manpower, 28(1), 75–94.

Kamal, M. M., Hassan, A. E., Alam, M. S., & Islam, M. S. (2013). Labor migration to the Middle-East and maladjustment with social environment: A study in a rural village in Bangladesh. Asian Social Science, 9(11), 174–188.

Khawaja, N. G., Yang, S., & Cockshaw, W. (2016). Taiwanese migrants in Australia: An investigation of their acculturation and wellbeing. Journal of Pacific Rim Psychology, 10(e4), 1–10.

Kifle, T., Kler, P., & Shankar, S. (2016). Immigrant job satisfaction: The Australian experience. International Journal of Manpower, 37(1), 99–114.

Kirkman, B. L., & Shapiro, D. L. (2001). The impact of cultural values on job satisfaction and organizational commitment in self-managing work teams: The mediating role of employee resistance. Academy of Management Journal, 44(3), 557–569.

Ko, J., Frey, J. J., Osteen, P., & Ahn, H. (2015). Moderating effects of immigrant status on determinants of job satisfaction: Implications for occupational health. Journal of Career Development, 42(5), 396–411.

Kossoudji, S. A. (1988). English language ability and the labor market opportunities of Hispanic and East Asian immigrant men. Journal of Labor Economics, 6(2), 205–228.

Kraimer, M. L., Seibert, S. E., Wayne, S. J., Liden, R. C., & Bravo, J. (2011). Antecedents and outcomes of organizational support for development: The critical role of career opportunities. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(3), 485–500.

Lee, J. S. (2002). The Korean language in America: The role of cultural identity in heritage language learning. Language Culture and Curriculum, 15(2), 117–133.

Levine, D. I. (2001). [Review of the book Manufacturing advantage: Why high-performance work systems pay off by E. Appelbaum, T. Bailey, P. Berg,& A.L. Kalleberg]. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 55(1), 175–176.

Locke, E. (1976). The nature and causes of job satisfaction. In M. Dunnette (Ed.), Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology (pp. 1297–1349). Chicago, IL: Rand McNally.

Loher, B. T., Noe, R. A., Moeller, N. L., & Fitzgerald, M. P. (1985). A meta-analysis of the relation of job characteristics to job satisfaction. Journal of Applied Psychology, 70(2), 280–289.

Loscocco, K. A., & Roschelle, A. R. (1991). Influences on the quality of work and nonwork life: Two decades in review. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 39(2), 182–225.

Lu, Y., Samaratunge, R., & Härtel, C. E. (2011). Acculturation strategies among professional Chinese immigrants in the Australian workplace. Asia Pacific Journal of Human Resources, 49(1), 71–87.

Lu, Y., Samaratunge, R., & Härtel, C. E. (2012). The relationship between acculturation strategy and job satisfaction for professional Chinese immigrants in the Australian workplace. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 36(5), 669–681.

Lu, H., While, A. E., & Barriball, K. L. (2005). Job satisfaction among nurses: A literature review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 42(2), 211–227.

Luthans, F., Avolio, B. J., Avey, J. B., & Norman, S. M. (2007). Positive psychological capital: Measurement and relationship with performance and satisfaction. Personnel Psychology, 60(3), 541–572.

Magee, W., & Umamaheswar, J. (2011). Immigrant group differences in job satisfaction. Race and Social Problems, 3(4), 252–265.

May, D. R., Gilson, R. L., & Harter, L. M. (2004). The psychological conditions of meaningfulness, safety and availability and the engagement of the human spirit at work. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 77(1), 11–37.

McGuinness, S., & Byrne, D. (2014). Examining the relationships between labour market mismatches, earnings and job satisfaction among immigrant graduates in Europe. IZA Discussion Paper No. 8440. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2502300.

Mehra, A., Kilduff, M., & Brass, D. J. (2001). The social networks of high and low self-monitors: Implications for workplace performance. Administrative Science Quarterly, 46(1), 121–146.

Meyer, J. P., & Allen, N. J. (1999). Commitment in the workplace: Theory, research, and application. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Meyer, J. P., Stanley, D. J., Herscovitch, L., & Topolnytsky, L. (2002). Affective, continuance, and normative commitment to the organization: A meta-analysis of antecedents, correlates, and consequences. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 61(1), 20–52.

Mohammad Mosadegh Rad, A., & Hossein Yarmohammadian, M. (2006). A study of relationship between managers’ leadership style and employees’ job satisfaction. Leadership in Health Services, 19(2), 11–28.

Mok, C., & Finley, D. (1986). Job satisfaction and its relationship to demographics and turnover of hotel food-service workers in Hong Kong. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 5(2), 71–78.

Morrison, E. W. (2002). Newcomers’ relationships: The role of social network ties during socialization. Academy of Management Journal, 45(6), 1149–1160.

Ng, T. W., & Feldman, D. C. (2010). Organizational tenure and job performance. Journal of Management, 36(5), 1220–1250.

Oldham, G. R., & Hackman, J. R. (2005). How job characteristics theory happened. In K. G. Smith & M. A. Hitt (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of management theory: The process of theory development (pp. 151–170). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Ong, R., & Shah, S. (2012). Job security satisfaction in Australia: Do migrant characteristics and gender matter? Australian Journal of Labour Economics, 15(2), 123–139.

Paul, A. M. (2011). Stepwise international migration: A multistage migration pattern for the aspiring migrant. American Journal of Sociology, 116(6), 1842–1886.

Pervin, L. A. (1987). Person-environment congruence in the light of the person-situation controversy. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 31(3), 222–230.

Pottie, K., Ng, E., Spitzer, D., Mohammed, A., & Glazier, R. (2008). Language proficiency, gender and self-reported health: An analysis of the first two waves of the longitudinal survey of immigrants to Canada. Canadian Journal of Public Health/Revue Canadienne de Sante’e Publique, 99(6), 505–510.

Price, J. L. (2001). Reflections on the determinants of voluntary turnover. International Journal of Manpower, 22(7), 600–624.

Quarstein, V. A., McAfee, R. B., & Glassman, M. (1992). The situational occurrences theory of job satisfaction. Human Relations, 45(8), 859–873.

Remennick, L. (2005). Immigration, gender, and psychosocial adjustment: A study of 150 immigrant couples in Israel. Sex Roles, 53(11–12), 847–863.

Rhodes, S. R. (1983). Age-related differences in work attitudes and behavior: A review and conceptual analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 93(2), 328–367.

Rice, R. W., Near, J. P., & Hunt, R. G. (1980). The job-satisfaction/life-satisfaction relationship: A review of empirical research. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 1(1), 37–64.

Roberts, R. K., Swanson, N. G., & Murphy, L. R. (2004). Discrimination and occupational mental health. Journal of Mental Health, 13(2), 129–142.

Roelen, C. A., Koopmans, P., & Groothoff, J. (2008). Which work factors determine job satisfaction? Work, 30(4), 433–439.

Rooth, D. O., & Ekberg, J. (2006). Occupational mobility for immigrants in Sweden. International Migration, 44(2), 57–77.

Schaufeli, W. B., & Bakker, A. B. (2004). Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi-sample study. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 25(3), 293–315.

Schneider, B. (1987). E = f (P, B): The road to a radical approach to person-environment fit. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 31(3), 353–361.

Schwartz, S. J., Unger, J. B., Zamboanga, B. L., & Szapocznik, J. (2010). Rethinking the concept of acculturation: Implications for theory and research. American Psychologist, 65(4), 237.

Schwartz, S. J., Waterman, A. S., Umaña-Taylor, A. J., Lee, R. M., Kim, S. Y., Vazsonyi, A. T., et al. (2013). Acculturation and well-being among college students from immigrant families. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 69(4), 298–318.

Scott, K. D., & Taylor, G. S. (1985). An examination of conflicting findings on the relationship between job satisfaction and absenteeism: A meta-analysis. Academy of Management Journal, 28(3), 599–612.

Shalley, C. E., Gilson, L. L., & Blum, T. C. (2000). Matching creativity requirements and the work environment: Effects on satisfaction and intentions to leave. Academy of Management Journal, 43(2), 215–223.

Short, J. (2009). The art of writing a review article. Journal of Management, 35(6), 1312–1317.

Smerek, R. E., & Peterson, M. (2007). Examining Herzberg’s theory: Improving job satisfaction among non-academic employees at a university. Research in Higher Education, 48(2), 229–250.

Sparrowe, R. T., Liden, R. C., Wayne, S. J., & Kraimer, M. L. (2001). Social networks and the performance of individuals and groups. Academy of Management Journal, 44(2), 316–325.

Spector, P. E. (1997). Job satisfaction: Application, assessment, causes, and consequences. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Tajfel, H. (1981). Human groups and social categories: Studies in social psychology. Cambridge: CUP Archive.

Taylor, S. E., & Sirois, F. M. (1995). Health psychology. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Tett, R. P., & Meyer, J. P. (1993). Job satisfaction, organizational commitment, turnover intention, and turnover: Path analyses based on meta-analytic findings. Personnel Psychology, 46(2), 259–293.

Townsend, R., Pascal, J., & Delves, M. (2014). South East Asian migrant experiences in regional Victoria: Exploring well-being. Journal of Sociology, 50(4), 601–615.

Valdivia, C., & Flores, L. Y. (2012). Factors affecting the job satisfaction of Latino/a immigrants in the Midwest. Journal of Career Development, 39(1), 31–49.

Vieira, J. A. C. (2005). Skill mismatches and job satisfaction. Economics Letters, 89(1), 39–47.

Wadsworth, E., Dhillon, K., Shaw, C., Bhui, K., Stansfeld, S., & Smith, A. (2007). Racial discrimination, ethnicity and work stress. Occupational Medicine, 57(1), 18–24.

Ward, C., & Masgoret, A. M. (2008). Attitudes toward immigrants, immigration, and multiculturalism in New Zealand: A social psychological analysis. International Migration Review, 42(1), 227–248.

Weichselbaumer, D. (2016). Discrimination against migrant job applicants in Austria: An experimental study. German Economic Review, 18(2), 237–265.