Abstract

Despite growing understanding of resilience as a process associated with both individual capacities and physical and relational resources located in social ecologies, most instruments designed to measure resilience overemphasize individual characteristics without adequately addressing the contextual resources that support resilience processes. Additionally, most resilience studies have focused on children and youth, without significant attention to social ecological factors that promote post-risk adaptation for adults and how this is measured. Consequently, a key issue in the continued study of adult resilience is measurement instrument development. This article details adaptation of the Child and Youth Resilience Measure for use with an adult population. The article draws on data from a mixed methods study exploring the resilience processes of Irish survivors of clerical institutional abuse. The sample included 105 adult survivors (aged 50–99) who completed the RRC-ARM and the Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS) during the first phase of the study. Exploratory factor analysis, Cronbach Alpha and MANOVA were conducted on the data. EFA identified five factors; social/community inclusion, family attachment and supports, spirituality, national and cultural identity, and personal competencies. The RRC-ARM shows good internal reliability and convergent validity with the WEMWBS, with significant differences on scale scores for men and women, as well as place of residence. This exploratory adaptation supports the potential of the RRC-ARM as a measure of social ecological resilience resources for adult populations and may have particular applications with vulnerable communities. Further validation is required in other contexts and specifically with larger samples.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

It is now widely accepted that resilience is associated with individual capacities, relationships and the availability of community resources and opportunities (Luthar et al. 2006; Masten 2014). Despite this move towards a social-ecological understanding of resilience, most tools designed to measure resilience overemphasize individual characteristics without adequately addressing the quality of physical and relational resources located in the social ecology that support resilience processes (Liebenberg et al. 2012). Furthermore, many resilience scales were developed to measure strengths across an entire population, both those at risk and those not at risk, and therefore might be understood as measures of developmental assets—strengths—rather than resilience (Windle et al. 2011).

The current article originates from a research project that set out to explore the social ecological resilience resources of survivors of the Irish clerical institutional childhood abuse (ICA). At the outset of this study, a research advisory panel was recruited to provide advice and guidance during the design stage. Considering the poor mental health outcomes, social isolation and literacy issues of many survivors of ICA (Carr et al. 2010; Commission to Inquire into Child Abuse; CICA 2009), the panel expressed concerns about the length, complexity and language of several common adult resilience measures. An instrument that stood out in terms of relevance was the 28 item Child and Youth Resilience Measure (CYRM-28; Liebenberg et al. 2012; Ungar and Liebenberg 2011). In their review of resilience measures, Windle et al. (2011) highlight the contemporary conceptual framework and cultural sensitivity of the CYRM-28 as one of its strengths. Moreover, this measure was designed with a specific focus on youth ‘at risk’ for poor psychosocial outcomes (Ungar and Liebenberg 2011). At design stage of this study, a separate large scale study had begun adaptation of the CYRM-28 for use with adult groups (May-Chahal et al. 2012). Their adaptation of the CYRM-28 is used in the current study.

With a view to developing an appropriate measure of adult resilience resources that is conceptually focused on the social ecological factors underpinning resilience processes, this article reviews the reliability and validity of the CYRM-28 for use with adult populations who have had persistent high risk/high stress experiences. We begin by reviewing the social ecological understanding of resilience, followed by a brief discussion of concerns in measuring resilience. Next we explain the context of the current study along with the methodological details of the analysis presented here. First an exploratory factor analysis was used to identify sub-scales of the RRC-ARM. We then assessed reliability, floor and ceiling effects, as well as convergent validity with a similar measure; the Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale (WBMWBS; Stewart-Brown and Janmohamed 2008). The latter part of the article describes the results of the analysis regarding the emerging measure: the Resilience Research Centre-Adult Resilience Measure (RRC-ARM; Resilience Research Centre 2013). Where possible, qualitative findings are included to facilitate interpretation and/or affirm findings.

1 What is Resilience?

Traditionally, investigations of individuals who have experienced significant threat or adversity have focused on maladaptive behaviour and those who showed relatively adaptive patterns were afforded little attention. Following Garmezy’s (1974) research, there have been increasing empirical efforts to understand individual variations in response to adversity with a particular focus on positive adaptation. While early efforts focused on personal qualities or traits of “resilient children,” such as autonomy or high self-esteem (see Anthony 1974; Garmezy 1974), research soon expanded to consider the processes underlying pathways to positive adaptation (Egeland et al. 1993; Masten et al. 1990; Masten and Wright 2010), as well as the relational and contextual resources that promote adaptive outcomes (Cicchetti 2010; Cicchetti and Curtis 2006; Masten 2001, 2007; Rutter 1987; Werner 1992; Werner and Smith 1982). Much of this research indicated that there were in fact great consistencies across individual qualities, resources, and relationships—social ecological factors—as predictors of positive outcomes (Bonanno and Diminich 2012), but that there is also a need for a contextually relevant understanding of the processes related to these resilience promoting resources (Wright et al. 2013).

Over the last two decades, studies have affirmed that resilience is not a static state, an outcome or an inherent trait within the individual (see for example Kolar 2011; Masten 2014). Rather, the interactions between an individual’s environment, their social ecology, and an individual’s assets, promote resilience (Masten 2014). Consequently, the focus of empirical work continues to expand from identifying protective factors within and outcomes related to the individual to include an understanding of the underlying mechanisms and processes located in their environment. Additionally, rather than simply studying individual, family, and environmental factors that correlate with better outcomes, researchers are increasingly striving to understand how such factors interact to result in better outcomes (Cowen et al. 1997; Luthar 1999; Munford and Sanders 2015; Rutter 1987). Such attention to underlying mechanisms and interactive processes is viewed as essential for advancing theory and research in the field, as well as for designing appropriate prevention and intervention strategies for individuals facing adversity (Cicchetti and Toth 1991; Luthar 1993; Masten 2014; Rutter 1990).

Although, there remains no universally accepted definition of resilience (Windle 2010), there are several explanations that share in common a number of features all associating resilience with human strengths in interaction with contextual resources, some type of disruption and growth, adaptive coping, and positive outcomes despite and/or following exposure to adversity (e.g., Bonanno et al. 2004; Connor and Davidson 2003; Friborg et al. 2005; Masten 2001; Richardson 2002). In their recent concept-analysis of 2979 relevant studies, Windle et al. (2011) explained resilience “as the process of effectively negotiating, adapting to, or managing significant sources of stress or trauma. Assets and resources within the individual, their life and environment facilitate the capacity for adaptation or bouncing back in the face of adversity. Across the life course, experiences of resilience will vary” (p. 163). This description highlights a key component contained in many others like it: contextually relevant resources, including physical resources, relational supports, and services, are key to the processes that scaffold positive outcomes in the face of significant risks. Furthermore, given this interactive component of resilience, researchers are challenged to no longer see resilience as a static characteristic or trait, but rather as a process that fluctuates over time.

For example, in researching how individuals manage or negotiate cumulative risk exposure, investigators have conducted qualitative studies of positive adaptation among war-affected children, emancipated child labourers (Denov and Maclure 2007; Panter-Brick 2002; Woodhead 2004), and children who have been victims of violence or witnesses to its perpetration (Bolger and Patterson 2003; Holt et al. 2008). These studies demonstrate that resilience is not a permanent feature. It ebbs and flows in response to different sets of circumstances throughout life (Daniel et al. 1999; Thomas and Hall 2008). Furthermore, this process is dependent on varying resources as individuals develop and age, and as contexts evolve (see for example, Bottrell 2009; Theron and Theron 2013).

To date, however, most resilience research has focused on the experiences of children and adolescents (Windle 2010). Far less is known about resilience in adulthood and later life, especially when faced with a prolonged and multiple risk exposures (Rodin and Stewart 2012; Windle et al. 2011). Despite this lack of research on resilience across the life course, we are beginning to understand that outcomes generally worsen as risk factors accumulate and concomitantly, resilience resources and processes become less common (Rodin and Stewart 2012; Rutter 1999), although this is not always the case (Shrira et al. 2010).

There remains however a need for greater understanding of resilience processes in adulthood. Masten and Wright (2010), for example, have questioned the indicators of doing well in adulthood, given the multitude of dimensions adulthood encompasses. Specifically, they ask if an adult “need[s] to be doing well in all major developmental tasks or only some of them? How are these decisions made in studies of resilience, and how has this impacted our study of the phenomena?” (p. 218). They go on to argue that predominant modes of studying adult resilience have rendered a narrow and static understanding of the phenomena amongst adults that belies both the dynamic processes at play as well as the ways in which resilience manifests itself given contextual variation. They conclude that there is a need for research that incorporates “more domains of adaptation” (p. 219) in order to address the shortcomings in our understanding of resilience. The same authors advocate that those working in the field of adult resilience, draw on the wealth of knowledge gleaned from several decades of resilience research with children and youth in understanding adult pathways to positive outcomes.

A key issue in the continued study of adult resilience is how positive adaptation or development post risk exposure is measured in quantitative studies, accounting for all relevant promotive factors (Ahern et al. 2006; Smith et al. 2008). For example, in their review of resilience measures, Windle et al. (2011) retrieved 2979 articles for consideration. From this 17 resilience scales were identified for review. The study found no single measure that could be recommended for studies which run across the lifespan. Of the 17 instruments deemed appropriate for inclusion, the majority (nine) focus on assessing resilience at the level of individual characteristics/resources only. Only five measures examine resilience across multiple personal and contextual levels.

Included in the measures identified as assessing resilience across multiple levels, is the CYRM-28. The CYRM-28 was developed out of a mixed methods study located in 14 sites internationally (see Ungar and Liebenberg 2011). Drawing on qualitative data gathered from youth and adults living in contexts of significant adversity, items were developed to reflect Bronfenbrenner’s (1979) ecological model of development. Subsequent analysis on youth data has highlighted three subscales that reflect core components identified as central to resilience processes (Liebenberg et al. 2012). These include individual resilience resources (i.e. personal skills, social skills, and peer support); relational resources (i.e. physical and psychological support from caregivers); and contextual resources (i.e. sense of belonging, educational adhesion and spirituality). The sub-scales and related items reflect both a social ecological understanding of resilience (Liebenberg et al. 2012), as well as the “short list” of resilience correlates outlined by Wright et al. (2013). Returning to Masten and Wright’s (2010) suggestion that researchers draw on existing understandings of child and youth resilience to further our understanding of adult resilience, both of these frameworks provide a solid structure for assessing an adult measure of resilience, suggesting value in the CYRM-28 as a measure of adult resilience resources.

2 The Context of the Study: Institutional Childhood Abuse and Resilience

Data used in the analysis presented here, comes from a study of institutional childhood abuse (ICA) and resilience in Ireland. Estimates suggest that approximately 170,000 children and young people attended industrial schools and reformatories in Ireland during the years 1930–1970 (CICA 2009). Schools were run in a severe, regimented manner that imposed unreasonable and oppressive discipline on children. Evidence shows that residents of these schools were neglected or maltreated in a range of other ways, including deprivation of family contact, personal identity, secure relationships, affection, approval, and a lack of protection; physical and sexual abuse occurred in many of them, particularly boys’ institutions (CICA 2009, Volume III, para. 6.01).

For the majority, institutional childhood abuse (ICA) in religious settings is associated with impaired psychological development (Carr et al. 2010; Gallagher 2000). Carr et al. (2010) found the prevalence of psychological conditions among adult survivors of ICA to be over 80%, with anxiety, mood and substance use disorders being the most prevalent conditions. In the same study, more than 80% of participants had an insecure adult attachment style, indicative of having problems making and maintaining satisfying intimate relationships. Wolfe et al. (2003) found that 88% of a group of 76 Canadian adult survivors of ICA experienced a psychological disorder at some point in their lives. The same study found unique themes associated with ICA, including loss of trust, shame and humiliation, fear or disrespect of authority, attempts to avoid any reminders of the abuse, and vicarious trauma stemming from disruption to their family and personal relationships.

While these studies highlight the overwhelming negative impact of ICA on adults, they also indicate that a proportion of survivors do not show these signs of maladaptation. In the sudy by Wolfe et al. (2003), 12% were “resilient and showed good adaptation, despite institutional abuse” (Flanagan et al. 2010, p. 56). Working with a sample of 247 adults, Flanagan et al. (2010) found 45 cases did not meet the criteria for common DSM IV axis I or II disorders. According to these authors, the “resilient group was older and of higher socioeconomic status; had suffered less sexual and emotional abuse; experienced less traumatisation and re-enactment on institutional abuse; had fewer trauma symptoms and life problems; had a higher quality of life and global functioning; engaged in less avoidant coping and more resilient survivors had a secure attachment style” (p. 56).

Although these studies present valuable information on pathology and the presence of resilience, they provide less data on the interactional and environmental factors that promote resilience. Moreover, these studies define resilience as the absence of disorder, an approach which has been questioned in the recent literature (Bonanno and Diminich 2012). The study, from which the data in the current article is taken, sought to move beyond an outcome orientated understanding of resilience in the face of ICA. Specifically, the purpose of the original study was to explore the social ecological resilience of Irish survivors of institutional childhood abuse (ICA) using a mixed-methods (quan → qual) design. The first phase entailed quantitative data collection, using a survey which included the adapted version of the CYRM-28; the RRC-ARM. The study also employed a measure of mental well-being: the Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale (WEMWBS; Stewart-Brown and Janmohamed 2008). An advisory committee made up of survivors of ICA (n = 6), together with a group of helping professionals working with survivors of ICA (n = 5) advised on the design and implementation of the study. The RRC-ARM along with two other common adult resilience measures was reviewed by both groups for suitability. All members recommended the RRC-ARM above the other two options. The second phase of the study involved individual qualitative interviews of a sub-sample of participants.

This article reviews the quantitative resilience measure used in this study, assessing the RRC-ARM’s reliability and validity as a measure of resilience resources for adults. Data from this qualitative phase of the study is included in this article to support interpretation of the findings.

3 Methods

3.1 Sample

The sample comprised 105 adult survivors of clerical institutional childhood abuse (ICA). This sample included 52 (50%) men and 49 (47%) women (data was missing for four participants; 3%) and the average age was 66.55 years (SD 7.17; range 50–99; data was missing for four participants; 3%). At the time of the study, 56 (53.3%) participants were residing in the UK and 46 (43.8%) resident in Ireland. One (.95%) participant was resident in Germany and three (2.9%) did not provide information on their country of residence. Of these participants, nine individuals were invited to participate in the qualitative component of the study. Seven of these participants were women, and they ranged in age from 57 to 66. All participants in the qualitative component were living in Britain at the time of the study.

The study employed non-proportionate purposeful sampling together with snowballing techniques. Three agencies that provide specific services for Irish survivors of ICA were involved in the recruitment of participants. All agencies agreed to guidelines in relation to recruitment and administration of the survey. These guidelines outlined key ethical and safeguarding features of the study. For example, in keeping with the practice of other studies with survivors of ICA (e.g. Carr et al. 2010) participants were offered the option of receiving a phone call from the respective agency a few days after completing the survey. This was designed to manage risk and safeguard against re-traumatisation post interview. The survey instrument included a page with details of specific services for survivors of ICA in Ireland and in the UK.

Nested sampling was used to identify participants for the qualitative component of the study. Nested sampling facilitates credible comparisons of two or more members of the same subgroup, wherein one or more members of the subgroup represent a subsample of the full sample (Collins et al. 2007). In the current study, this method was employed to recruit individuals who were deemed to have coped well despite experiencing significant adversity in childhood. To identify participants, three practitioners from specialist services nominated current or previous clients who they deemed to have managed well in spite of the experiences of ICA.

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Dublin City University, prior to commencement of the data collection and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

3.2 Measures

The RRC-ARM is an adapted version of the CYRM-28. The CYRM-28 was designed as part of the International Resilience Project (IRP) in collaboration with 14 communities in 11 countries around the world (Ungar and Liebenberg 2011). A three sub-scale measure reflecting individual, relational and contextual resilience processes has since been validated on a Canadian sample of youth (α = .803; α = .833; α = .794; Liebenberg et al. 2012). A similar four factor structure has also been validated on a New Zealand sample of youth (Social and cultural context: α = .772; Family relationships: α = .805; Individual resources: α = .662; Spiritual and Community resources: α = .746; Sanders et al. 2015).

Items have been adapted for use with adults. The re-wording of the adult version was conducted by May-Chahal et al. (2012) as part of the “Tracking Vulnerability and Resilience: Gambling Careers in the Criminal Justice System” study, at the Department of Applied Social Science, Lancaster University (details of this process are unavailable). The scale is scored by summing responses to each item answered on a five point Likert scale, where 1 = not at all and 5 = all the time. The minimum scale score is 28 and the maximum 140.

The Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS; Stewart-Brown and Janmohamed 2008; α = .89) is a 14-item scale of mental well-being. The scale reviews subjective well-being and psychological functioning. The scale is scored by summing responses to each item answered on a five point Likert scale, where 1 = none of the time and 5 = all of the time. The minimum scale score is 14 and the maximum is 70. WEMWBS has been validated for use in the UK with those aged 16 and above. Validation involved both student (Tennant et al. 2007) and general population samples (Maheswaran et al. 2012). The Cronbach alpha score in this study was .967.

Interviews were guided by the nine catalyst questions used in the research that informed the developed of the CYRM (Ungar and Liebenberg 2005), rephrased for an adult population of ICA survivors. The current study also included a narrative approach to the post-ICA life course of participants, in an effort to discover turning points and related supports.

3.3 Analysis

Because this is the first study investigating the use of the RRC-ARM with adults in Ireland, combined with the sample size (n = 105), only an Explanatory Factor Analysis (EFA) was conducted. Once sub-scales had been identified, we explored the floor and ceiling effects of scores on each of the sub-scales looking at frequency distributions of scores and assessed reliability using Cronbach’s alpha. We then assessed criterion validity of the RRC-ARM total score and respective subscale scores with the Warwick Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS), using Pearson correlation coefficients. Finally, a MANOVA was conducted with the RRC-ARM sub-scales as dependent variables and sex and country of residence as independent variables. This test aimed to investigate expected differences across these groups. Data was analyzed using PASW Statistics 18.

A missing variable analysis was conducted on the full data set. Four participants were removed from the analysis because they had more than 10% missing data. Demographic information for one of the removed participants was missing while the remaining three were all male, aged 69, 77 and 99 respectively. Following this there were less than 4.8% missing data and that missing data were missing completely at random (MCAR; x 2(366) = 510.571, p = .000; Enders 2010).

Cross-tabulations between our demographic variables (sex and age) and scale item response variables showed that while there were no systematic differences in the missing values among the categories of sex, there were in terms of age. We found that participants over the age of 62 were more likely to refuse to answer questions (as reflected in the participants with exceptionally high rates of missing data, removed from the analysis). Since the missingness could be explained by observed information, we could adjust for the missingness through the maximum likelihood imputation method (EM; Enders 2010).

All qualitative interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. Data was then analysed thematically using qualitative data analysis (QDA) software NVivo. Data was analysed deductively focusing on the prevalence of themes across the core domains of the CYRM-28 (individual, relational and contextual). In addition, in order to explore the post-ICA resilient trajectories, the data was analysis inductively across the parent theme of transitions.

4 Results

The EFA conducted on all items of the RRC-ARM used oblique rotation (Direct Oblimin) and the correlation matrix. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure verified the sampling adequacy for the analysis (KMO = .900; Hutcheson and Sofroniou 1999). Bartlett’s test of sphericity, x 2 (378) = 2834.441, p = .000, indicated that correlations between items were sufficiently large for an EFA. An initial analysis was conducted to obtain eigenvalues for each component in the data. Five components had eigenvalues greater than one and in combination explained 75% of the variance. Review of the sort of items in a five factor solution suggested retention of five components, each reflecting aspects of resilience theory (Garmezy 1985; Luthar et al. 2000; Masten and Wright 2010; Rutter 2000). Specifically, item clustering suggested the following themes: Component 1 represents social/community inclusion; Component 2, family attachment and supports; Component 3, spirituality; Component 4, national and cultural identity; and, Component 5, personal skills and competencies. The components explain 53.57%, 7.85%, 5.84%, 4.40%, and 3.67% of the variance, respectively. While a sample of 101 ordinarily necessitates a more restrictive loading criteria of at least .512 to be considered significant (Stevens 2002), given the history of the measure, the theoretical support for the item sort, and strong Cronbach alpha values, this criteria was not used as the ultimate decider. Rather, we used a cut-off criteria of .3. Most items showed a strong loading and loaded onto only a single factor. Table 1 shows the factor loadings of the five-factor solution after rotation.

Only one of the 28 items had multiple loadings: “20. I have opportunities to show others I can act responsibly”, appeared on both Components 1 (.434) and 5 (.550). Because notions of responsibility become more aligned with agency in adulthood, it could be argued that the item is more reflective of individual capacities than contextual opportunities. As such, it was decided to retain the item on Component 5 (Personal skills and competencies) due to its theoretical fit with notions of self-efficacy. Cronbach’s alpha scores demonstrated the reliability of all subscales (see Table 1).

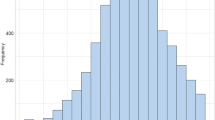

Overall scores on the RRC-ARM ranged from 30 to 136, versus possible scores of 28–140 demonstrating an absence of floor and ceiling effects on the total score. Less than 15% of respondents achieved the lowest or highest possible scores on Components 1 (Social/community inclusion; 5%), 2 (Family attachment and supports; 12%) and 5 (Personal competencies; 10%). By contrast 36% of respondents achieved minimum or maximum supports on Component 3 (Spirituality) and Component 4 (National and Cultural Identity). Interestingly, with regards to Spirituality, results were skewed towards minimum scores, with 58% of respondents scoring five or lower (with a maximum score of 10). Similarly, with regards to identity, 87% of respondents scored six or higher (with a maximum score of 10).

The results in relation to spiritual resources were somewhat expected and mirror previous studies which indicate that adult survivors of clerical ICA do not draw on spiritual or religious resources to promote resilience. For example, in Carr (2009), all participants (n = 247) experienced an increase in spiritual disengagement and only 10.3% reported a relationship with God or spiritual force as the main factor that helped them face life’s challenges. And as a participant in the qualitative component explained:

I’ve never went to church since. I think you’ll find a lot of people who left these places don’t go to church.…I just don’t believe in it. I wish it was true but I don’t believe on fairy tales anymore.

Although the scores on the identity subscale were surprising, these data were also echoed in the qualitative phase of the study with participants reporting strong cultural, and in particular, national identification.

We’re like other Irish people, we’re very interested in Ireland and what goes on, even though we’ve no homes in Ireland… I love Ireland dearly but there’s a certain bit inside me that I don’t love because they never wanted you.

Furthermore, although a new finding in the context of Irish survivors of ICA, studies with South Asian immigrant women who have survived child sexual abuse have pointed to high levels of ethnic identification in the aftermath of this adversity (Singh et al. 2010). Similarly, studies of holocaust survivors have demonstrated high levels of cultural and group affiliation, particularly in those who migrated to Israel in aftermath of WWII (Danieli and Norris 2016).

The RRC-ARM shows strong criterion validity with the WEMWBS. Very large correlations were found between the RRC-ARM total score and the WEMWBS (r = .816, n = 93, p = .000; Cohen 1988). Similar results were found for the WEMWBS and the sense of social/community inclusion sub-scale (r = .788, n = 101, p = .000), and the personal competencies sub-scale (r = .809, n = 101, p = .000). Medium correlations were found with the family attachment and supports sub-scale (r = .644, n = 101, p = .000) and moderate correlations were found between the WEMWBS and the spirituality sub-scale (r = .301, n = 101, p = .002), and the national and cultural identity sub-scale (r = .404, n = 101, p = .000).

The strong scores between WEMWBS and sense of social/community inclusion as well as personal competencies is reflected in the qualitative data. Virtually all respondents gave examples of altruistic behaviour across the lifespan and in particular whilst in institutional care. This altruism drew on their personal competencies but stemmed from and developed and/or augmented their sense of social/community inclusion. Although this altruism did result in risk exposure in some instances, rather than being defined by this exposure, participants described engaging in strategies that aimed to reduce exposure to physical and sexual abuse for others, often more vulnerable children or siblings. In the example below, one participant explained how she had grown up with people depending on her and how helping ‘others to survive’ was a positive coping strategy. In most cases participants described how this type of behaviour had continued post ICA and in most cases transferred to new actors in their life, such as family and friends.

I used to advocate on behalf of my sister, even though she was physically bigger than me. So I was considered a bit outspoken and a bit of a tomboy and what have you. Yes, I took on the role of protector of my sister and protector of my friends. Funny enough that’s never changed, thanks be to God.

Research on Irish emigrants to the UK born between the years of 1920–1960, indicate that relocation to the UK may have bolstered the resilience resources of this group (Delaney et al. 2012). Some have suggested that, of Irish migrants to the UK during this period, females experienced a more resilient post migrant trajectory (Tilki et al. 2009). Furthermore, in her review of the literature on resilience and ICA, Conway (2012) states that “the literature reviewed demonstrated potential differences in how men and women respond to and recover from abuse experiences” (p. 9). With this research in mind, we expected to see differences in resilience scores by sex and by country of residence. As such, a MANOVA was conducted with sex (two levels: male and female) and country of residence (two levels: UK and Ireland), as independent variables and the five sub-scale groupings of RRC-ARM questions as the dependent variables (see Table 2). Using Pillai’s Trace, there was a significant difference between males and females, F(5, 89) = 4.38, p = .001, η 2p = .20, and between those resident in UK and Ireland, F(5, 89) = 5.77, p = .000, η 2p = .25. Both tests demonstrate the strong effect of the independent variables (sex and country of residence) on the total score of the RRC-ARM. Despite these results, there was no significant interaction effect between sex and country of residence on the dependent variable, F(5, 89) = .711, p = .617, η 2p = .038.

When results for the RRC-ARM sub-scales by country of residence were considered separately, using a Bonferroni adjusted a level of .01, the only subscale components to reach statistical significance were personal skills and competencies and family support. The effect size for both subscales are, however, negligible (Cohen 1988). When the results by sex were considered separately only spirituality and social inclusion reached significance. Again, the effect size for both were negligible (Cohen 1988).

Table 3 shows the mean scores and standard deviations for each of the groups. Results show that women score higher than men on all five sub-scales. The differences seen in these scores are significant for social and community inclusion (p = .018), family support (p = .035), and spiritual resources (p = .000). These differences are most significant for spiritual resources (η2 = .189).

This dataset also provided some support for the different levels of social and community inclusion found in the quantitative data. Many female participants described the importance of peer support groups and pointed to the low take up of males in such networks.

It’s only really women at these [peer support] groups. It’s a different ballgame for men, oh my God. The men are really damaged and they’re very angry, the men. But then they had a much harder time.

We see a similar pattern depending on where participants live. Participants in the UK consistently score higher than their counterparts in Ireland. Here, however, significant differences are found only between the two groups with regards to family support (p = .007) and personal skills and competencies (p = .001).

These higher scores may be explained by the qualitative data. For those who migrated to the UK, employment and training opportunties, unavailable in Ireland at time, faciliated the development of personal and skills and competencies. Participants in the qualitative component for example, descibed how migration offered new opportunties and the development of associated skills:

I worked for years in an office all my working life here in England and I learnt a lot…in Ireland I just worked in a house because that’s all I could do…as soon as you got on the plane and came to England the doors were opened for you, which was great

In my first job in England there was things I was very bad at. My English was okay, but my spelling was chronic. My math was shocking… I learned a lot very quickly because you had to keep up. If you didn’t you’d fall behind, and people didn’t want to be carrying you.

Despite differences across the groups in terms of significance, the ways in which resources are reported on holds the same for men and women, as well as location of residence. In all instances, participants report drawing most on their national and cultural identity, followed by their personal competencies.

The qualitative data did however somewhat support the notion of the differing importance of spirituality, with two female participants commenting on the importance of prayers learnt in care in the immediate aftermath of leaving care and of a ‘non – catholic spirituality’ in later life:

I still believe that we’re spiritual beings in some way, not necessarily this Catholic philosophy, but I do believe that at some point there’s some bit of spirituality in your life

And I remember like I would be walking along the streets and I’d be praying and all these prayers that they told us”. Overall however, Spiritual resources are least reported on by all participants.

5 Discussion

Using the framework for assessing the quality of resilience measures as set out by Windle et al. (2011) the RRC-ARM shows strong potential for an adult measure of resilience. First the measure shows good content validity. Despite poor mental health outcomes and literacy levels (CICA 2009), high completion rates of the measure in this study indicates the potential applications of the RRC-ARM with vulnerable adult populations. Furthermore, the advisory group reported good face validity and usability with survivors of ICA, suggesting that in contrast to some longer and more complex measures of resilience, the RRC-ARM may be a good fit for vulnerable adult populations.

Second, the theoretically sound results of the EFA combined with high Cronbach alpha values demonstrated strong internal consistency. The suggested subscales reflect the protective factors consistently identified in resilience research (see Masten and Wright 2010 for a detailed discussion). Specifically, the RRC-ARM contains factors reflective of attachment relationships, most notably with a partner and family (family attachments and supports) as well as social relationships embedded in community (social/community inclusion). Sense of belonging, and understanding of place in the world, is reflected in the national and cultural identity factor. The RRC-ARM also contains a factor reflecting personal agency and mastery—personal skills and competencies. Items such as “Getting qualifications or skills is important to me” and “I try to finish what I start” reflect intrinsic motivation while “I can solve problems without harming myself or others” and “I know my own strengths” reflect self-efficacy. This factor also reflects aspects of self-regulation, as seen in items such as “I know how to behave in different social situations” and previously mentioned items such as “I can solve problems without harming myself or others”. The spirituality factor connects with themes of faith and hope, as well as the capacity to make meaning of events (for example “Spiritual believes are a source of strength for me”) as well as religion as an identified component of resilience (“I participate in organised religious activities). While these five sub-scales reflect resilience resources contained in the literature, it is important to keep in mind that the initial 28 items of the CYRM were developed using qualitative focus groups with children and adults across 14 sites globally (Ungar and Liebenberg 2011). In this way, the original items also have high content validity.

Third, criterion validity has been demonstrated through the high correlations (≥.70) between the RRC-ARM total score and the WEMWBS, as well as two sub-scales of the RRC-ARM (social/community inclusion and personal competencies) and the WEMWBS. The relationship between personal skills and competencies and mental well-being is strongly supported by previous resilience research (Masten 2001; Gilligan 2008) and studies with survivors of ICA show that resilience is associated with less avoidant coping (Flanagan et al. 2010). In terms of social/community inclusion, Gilligan (2008) has found that social inclusion and community support is related to resilience for public care leavers. Some of the weaker correlations were also supported by previous studies. For example, in terms of family support, Flanagan et al. (2010) found that although secure adult romantic relationships were associated with resilience in the aftermath of ICA, marital or parental satisfaction did not promote resilience and there was no significant difference in resilience by marital status. Likewise, as discussed previously, studies have found that spiritual resources are not a source of resilience for adult survivors of ICA (Carr et al. 2010).

The between group differences found using the RRC-ARM mirrored findings in previous studies. Post hoc MANOVA test results showed that females scored significantly higher on the spiritual resource subscale with a moderate effect size. This is supported by studies which show that, in the aftermath of significant adversity, spiritual coping is more prevalent in women (Kremer and Ironson 2014; Wink et al. 2007). Furthermore, females scored significantly higher on the social/community inclusion subscales. This finding is supported by the qualitative data of the study, which highlights the role of peer support networks in promoting resilience for females. This finding is also reflected in studies which indicate that male survivors of ICA may experience higher levels of social isolation (CICA 2010; Higgins 2010). In relation to differences by place of residence, the RRC-ARM showed higher total scores for the emigrant sample. This is in line with differences in mental well-being found on the WEMWBS, with the emigrant sample (M = 45.07, SD 13.37) scoring significantly higher than the Irish based sample (M = 39.00, SD 12.87; t (100) = 2.31, p = .02), although the magnitude of the difference in the means (mean difference = 6.07, 95% CI .87–11.26) was moderate (η2 = .05). These findings are supported by studies which indicate that Irish migrants to the UK, born between 1920 and 1960, “were not only not harmed by going to England but possibly helped” (Delaney et al. 2012, p. 29).

Fourth, construct validity is suggested in these findings from the correlations between the two measures. The strong positive correlation with the WEMWBS is in keeping with numerous studies highlighting the relationship, and overlap, between resilience and mental well-being (Mguni et al. 2011; Miller et al. 1996; Souri and Hasanirad 2011). Furthermore, the factor structure found in this study is supported by previous studies outlining the main factors associated with resilience (Masten and Wright 2010). Additionally, the positive correlations with social/community inclusion, personal skill and competencies and family supports and weak correlation with spirituality, are all in keeping with previous studies (Carr 2009; CICA 2010; Flanagan et al. 2010; Gilligan 2008; Higgins 2010). Finally, the RRM-ARM identified significant, and theoretically expected, differences in resilience by gender and place of residence (Delany et al. 2010; Kremer and Ironson 2014; Tilki et al. 2009; Wink et al. 2007). Along with correlations with the WEMWBS, these differences across the subscales are consistent with recent theories which point to the contextual nature of resilience (Masten 2014; Masten and Wright 2010; Ungar and Liebenberg 2011).

There are no floor and ceiling effects for the RRC-ARM total score, and three of the five sub-scales. With regards to spirituality, previous research has demonstrated the negative impact of ICA on adult relations (CICA 2009). Furthermore, other studies have pointed to loss of religious faith in the aftermath of ICA, with anger and disillusionment towards the Church perpetuating into adulthood (Conway 2012; Wolfe et al. 2003). The results of the RRM-ARM demonstrated consistency with these findings, with the overall sample scoring lowest on spiritual subscale. With regards to overreliance on national and cultural identity, some researchers have suggested that expressions of ethnic pride and a sense of belonging to an ethnic group can enhance resilience (Castro et al. 2009). In the qualitative phase of the current study, the emigrant sample pointed to an identification with an Irish identity, evidenced by statements such as ‘we’re very interested in Ireland’ and ‘we love Ireland dearly’. While many participants pointed to a connection with Ireland, they also described conflict surrounding their ethnic identity and feelings of marginalisation and rejection. Importantly, cultural and national identification did not translate into engagement in cultural networks and the associated supports and resources, with many participants choosing to exclude themselves from cultural activities that reminded them of their childhood. This may explain why, although participants scored highly on this subscale, this domain did not correlate significantly positively with mental well-being.

6 Limitations

The most notable limitation of this study is the small sample size. Despite this, several observations give credence to this initial exploratory work. Following on the work of authors such as Arrindell and van der Ende (1985), as well as Guadagnoli and Velicer (1988) has demonstrated that both absolute sample size and absolute magnitude of factor loadings should be considered in determining reliable factor loadings. Specifically factors of four or more loadings greater than .6 can be considered reliable, regardless of sample size. Three of the five components in this study have four or more loadings, and only four of these loadings are smaller than six. In the case of the two factors that have only two items each, all four items load above .787. Furthermore, MacCallum et al. (1999) have argued the value of reviewing communalities when dealing with smaller sample sizes. They explain that for samples smaller than 100, communalities above .6 reflect sample adequacy. Only one of the 28 items falls below this mark (i.e. “I have opportunities to be useful in life”; .472). Given the sample size, however, we have also been unable to confirm the factor structure of the RRC-ARM using confirmatory factor analysis.

In the absence of test–retest data we have been unable to assess reproducibility (agreement and reliability). Similarly, in the absence of longitudinal data, we have not been able to determine responsiveness.

While a MANOVA has been used to explore group differences in scale and sub-scale scores, this has been done without prior multi-group analysis testing for invariance in the factor structure of the RRC-ARM.

As a result of low participation of males in the qualitative component (n = 2), this data was relatively ‘silent’ (Farmer 2006) on the different factors influencing resilience by sex.

Finally, as this data is taken from an existing study focused on the substantive issue of the resilience processes of ICA adults in Ireland, we have also been unable to include additional measures of wellbeing and resilience with which to assess for validity. It would be valuable for these issues to be addressed in future research.

7 Conclusion

Despite theoretical advances to our understanding the construct of resilience, validated assessments that allow for rigorous review of resilience processes, particularly with adult populations, are still not well developed (Masten 2007; Windle et al. 2011). This article details the initial exploratory adaptation of the CYRM-28 for use with adult populations. The RRC-ARM showed theoretically sound sort of items in the EFA, good internal reliability and converged strongly with a well validated measure (WEMWBS) of a construct highly associated with resilience. Along with the construct validity demonstrated in this study, the findings point to content validity as one of the strengths of the RRM-ARM. Studies have found that, as a result of giving evidence at highly charged commissions, Irish survivors of ICA are at risk of research fatigue and re-traumatisation during the research process (Moore et al. 2015; O’Riordan and Arensman 2007). The RRC-ARM was designed with ‘at risk’ populations in mind and, as such, the majority the questions are positively framed. The high completion rate and good face validity in the current study underscore the potential of this measure for use with vulnerable communities. Consequently, the RRC-ARM presents as a potentially sound measure of social ecological resilience in adult populations. Considering the sample size in the current study, and the unique nature of the adversity under examination, we recommend further studies with larger sample sizes and research populations that have experienced more replicable risks.

References

Ahern, N., Kiehl, E., Lou Sole, M., & Byers, J. (2006). A review of instruments measuring resilience. Issues in Comprehensive Pediatric Nursing. doi:10.1080/01460860600677643.

Anthony, E. (1974). The syndrome of the psychologically vulnerable child. In E. J. Anthony & C. Koupernik (Eds.), The Child in His Family (1st ed., pp. 3–10). New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

Arrindell, W. A., & Van der Ende, J. (1985). An empirical test of the utility of the observer-to-variables ratio in factor and components analysis. Applied Psychological Measurement, 9, 165–178.

Bolger, K., & Patterson, C. (2003). Sequelae of child maltreatment: Vulnerability and resilience. In S. S. Luthar (Ed.), Resilience and vulnerability: Adaptation in the context of childhood adversity (pp. 156–182). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Bonanno, G., & Diminich, E. (2012). Annual Research Review: Positive adjustment to adversity—trajectories of minimal-impact resilience and emergent resilience. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. doi:10.1111/jcpp.12021.

Bonanno, G., Papa, A., Lalande, K., Westphal, M., & Coifman, K. (2004). The importance of being flexible. Psychological Science. doi:10.1111/j.0956-7976.2004.00705.x.

Bottrell, D. (2009). Understanding ‘marginal’ perspectives: Towards a social theory of resilience. Qualitative Social Work Research & Practice. doi:10.1177/1473325009337840.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Carr, A. (2009). The psychological adjustment of adult survivors of institutional abuse in Ireland. Report submitted to the Commission to Inquire into Child Abuse (Chapter Three). Commission to Inquire into Child Abuse Report (The Ryan Report). Dublin: Government of Ireland.

Carr, A., Dooley, B., Fitzpatrick, M., Flanagan, E., Flanagan-Howard, R., Tierney, K., et al. (2010). Adult adjustment of survivors of institutional child abuse in Ireland. Child Abuse and Neglect. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.11.003.

Castro, F. G., Stein, J. A., & Bentler, P. M. (2009). Ethnic pride, traditional family values, and acculturation in early cigarette and alcohol use among Latino adolescents. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 30(3), 265–292.

Cicchetti, D. (2010). Resilience under conditions of extreme stress: A multilevel perspective. World Psychiatry, 9, 145–154.

Cicchetti, D., & Curtis, W. J. (2006). The developing brain and neural plasticity: Implications for normality, psychopathology and resilience. In D. Cicchetti & D. Cohen (Eds.), Developmental psychopathology: Vol. 2 Developmental Neuroscience (2nd ed., pp. 1–64). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Press.

Cicchetti, D., & Toth, S. (1991). The making of a developmental psychopathologist. In J. Cantor, C. Spiker, & L. Lipsitt (Eds.), Child behavior and development: Training for diversity (pp. 34–72). Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, N.J.: L. Erlbaum Associates.

Collins, K., Onwuegbuzie, A., & Jiao, Q. (2007). A mixed methods investigation of mixed methods sampling designs in social and health science research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 1(3), 267–294. doi:10.1177/1558689807299526.

Commission to Inquire into Child Abuse. (2009). Report of the Commission to Inquire into Child Abuse. Dublin: Stationary Office. Retrieved from http://www.childabusecommission.com/rpt/pdfs/.

Connor, K., & Davidson, J. (2003). Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depression and Anxiety. doi:10.1002/da.10113.

Conway, E. (2012). Uncertain legacies: Resilience and institutional abuse. Scottish Government Social Research. Retrieved from http://dera.ioe.ac.uk/15021/1/00395793.pdf.

Cowen, E., Work, W., & Wyman, P. (1997). The Rochester Child Resilience Project (RCRP): Facts found, lessons learned, future directions divined. In S. S. Luthar, J. A. Burack, D. Cicchetti, & J. R. Weisz (Eds.), Developmental psychopathology: Perspectives on adjustment, risk, and disorder (pp. 527–547). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Danieli, Y., & Norris, F. (2016). A Multidimensional Exploration of the Effects of Identity Ruptures is Israeli and North America Holocaust Survivors. Kavod; Honoring Aging Survivors, 6, n. pag.

Delaney, L., Fernihough, A., & Smith, J. (2012). Exporting poor health: The Irish in England. SSRN. doi:10.2139/ssrn.1923987.

Denov, M., & Maclure, R. (2007). Turnings and epiphanies: Militarization, life histories, and the making and unmaking of two child soldiers in Sierra Leone. Journal of Youth Studies. doi:10.1080/13676260601120187.

Egeland, B., Carlson, E., & Sroufe, L. A. (1993). Resilience as process. Educational Leadership, 37, 15–24.

Enders, C. (2010). Applied missing data analysis. New York, NY: The Guildford Press.

Farmer, T. (2006). Developing and implementing a triangulation protocol for qualitative health research. Qualitative Health Research, 16(3), 377–394. doi:10.1177/1049732305285708.

Flanagan, E., Carr, A., Dooley, B., Shevlin, R., Tierney, T., White, K., et al. (2010). Profiles of resilient survivors of institutional abuse in Ireland. International Journal of Child & Family Welfare, 12(2–3), 56–73.

Friborg, O., Barlaug, D., Martinussen, M., Rosenvinge, J. H., & Hjemdal, O. (2005). Resilience in relation to personality and intelligence. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. doi:10.1002/mpr.15.

Gallagher, B. (2000). Ritual, and child sexual abuse, but not ritual child sexual abuse. Child Abuse Review. doi:10.1002/1099-0852(200009/10)9.

Garmezy, N. (1974). The study of competence in children at risk for severe psychopathology. In E. J. Anthony & C. Koupernik (Eds.), The child in his family: Children at psychiatric risk (pp. 77–97). New York, NY: Wiley.

Garmezy, N. (1985). Stress-resistant children: The search for protective factors. In A. Davids (Ed.), Recent research in developmental psychopathology (pp. 213–233). Elmsford, NY: Pergamon Press.

Gilligan, R. (2008). Promoting resilience in young people in Long term care; the relevance of roles and relationships in the domains of recreation and work. Journal of Social Work Practice. doi:10.1080/02650530701872330.

Guadagnoli, E., & Velicer, F. (1988). Relation to sample size to the stability of component patterns. Psychological Bulletin. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.103.2.265.

Higgins, M. (2010). Developing a Profile of Survivors of abuse in Irish Religious Institutions. Dublin: The Saint Stephens Green Trust. Retrieved from http://www.ssgt.ie/files/developing_a_socio_economic_profile_of_survivors_o.pdf.

Holt, S., Buckley, H., & Whelan, S. (2008). The impact of exposure to domestic violence on children and young people: A review of the literature. Child Abuse and Neglect. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.02.004.

Hutcheson, G., & Sofroniou, N. (1999). The multivariate social scientist: Introductory statistics using generalized linear models. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Kolar, K. (2011). Resilience: Revisiting the concept and its utility for social research. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. doi:10.1007/s11469-011-9329-2.

Kremer, H., & Ironson, G. (2014). Longitudinal spiritual coping with trauma in people with HIV: Implications for health care. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. doi:10.1089/apc.2013.0280.

Liebenberg, L., Ungar, M., & Van de Vijver, F. (2012). Validation of the child and youth resilience measure-28 (CYRM-28) among Canadian youth. Research on Social Work Practice. doi:10.1177/1049731511428619.

Luthar, S. (1993). Annotation: Methodological and conceptual issues in the study of resilience. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 34, 441–453.

Luthar, S. (1999). Poverty and children’s adjustment. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Luthar, S., Cicchetti, D., & Becker, B. (2000). Research on resilience: Response to commentaries. Child Development. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00168.

Luthar, S., Sawyer, J., & Brown, P. (2006). Conceptual issues in studies of resilience: Past, present, and future research. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. doi:10.1196/annals.1376.009.

MacCallum, R. C., Widaman, K. F., Zhang, S., & Hong, S. (1999). Sample size in factor analysis: The role of model error. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 36(4), 611–637.

Maheswaran, H., Weich, S., Powell, J., & Stewart-Brown, S. (2012). Evaluating the responsiveness of the Wariwck Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale (WEMWBS): Group and individual level analysis. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 10(1), 156.

Masten, A. (2001). Ordinary magic: Resilience processes in development. American Psychologist. doi:10.1037//0003-066x.56.3.227.

Masten, A. (2007). Resilience in developing systems: Progress and promise as the fourth wave rises. Development and Psychopathology, 19, 921–930.

Masten, A. (2014). Ordinary magic: Resilience in development. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Masten, A., Best, K. M., & Garmezy, N. (1990). Resilience and development: Contributions from the study of children who overcome adversity. Development and Psychopathology, 2, 425–444.

Masten, A. S., & Wright, M. O. D. (2010). Resilience over the lifespan: Developmental perspectives on resistance, recovery, and transformation. In J. W. Reich, A. J. Zautra, & J. S. Hall (Eds.), Handbook of adult resilience (pp. 213–237). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

May-Chahal, C., Wilson, A., Humphreys, L., & Anderson, J. (2012). Promoting an evidence-informed approach to addressing problem gambling in UK prison populations. The Howard Journal of Criminal Justice. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2311.2012.00723.x.

Mguni, N., Bacon, N., & Brown, J. (2011). The well-being and Resilience Paradox. London: The Young Foundation. Retrieved from http://youngfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/The-Wellbeing-and-Resilience-Paradox.pdf.

Miller, D., Manne, S., Taylor, K., Keates, J., & Dougherty, J. (1996). Psychological distress and well-being in advanced cancer: The effects of optimism and coping. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings. doi:10.1007/bf01996132.

Moore, J., Thornton, C., & Hughes, M. (2015). On the road to resilience: The help-seeking experiences of Irish emigrant survivors of institutional abuse. Child Abuse Review. doi:10.1002/car.2415.

Munford, R., & Sanders, J. (2015). Young people’s search for agency: Making sense of their experiences and taking control. Qualitative Social Work. doi:10.1177/1473325014565149.

O’Riordan, M., & Arensman, E. (2007). Institutional child sexual abuse and suicidal behaviour: Outcomes of a literature review, consultation meetings and a qualitative study. Dublin: National Suicide Research Foundation. Retrieved from http://nsrf.ie/wp-content/uploads/reports/InstitutionalChildSexualNov07.pdf.

Panter-Brick, C. (2002). Street children, human rights, and public health: A critique and future directions. Annual Review of Anthropology. doi:10.1146/annurev.anthro.31.040402.085359.

Resilience Research Centre. (2013). User’s manual for the Resilience Research Centre-Adult Resilience Measure (RRC-ARM). Halifax, CA: Dalhousie University.

Richardson, G. (2002). The metatheory of resilience and resiliency. Journal of Clinical Psychology. doi:10.1002/jclp.10020.

Rodin, D., & Stewart, D. (2012). Resilience in elderly survivors of child maltreatment. SAGE Open. doi:10.1177/2158244012450293.

Rutter, M. (1987). Psychosocial resilience and protective mechanisms. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 57, 316–331.

Rutter, M. (1990). Psychosocial resilience and protective mechanisms. In J. Rolf, A. S. Masten, D. Cicchetti, K. H. Nuechterlein, & S. Weintraub (Eds.), Risk and protective factors in the development of psychopathology (pp. 181–214). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Rutter, M. (1999). Social context: Meanings, measures and mechanisms. European Review. doi:10.1017/s106279870000380x.

Rutter, M. (2000). Children in substitute care: Some conceptual considerations and research implications. Children and Youth Services Review. doi:10.1016/s0190-7409(00)00116-x.

Sanders, J., Munford, R., Thimasarn-Anwar, T., & Liebenberg, L. (2015). Validation of the Child and Youth Resilience Measure (CYRM-28) on a sample of at-risk New Zealand Youth. Research on Social Work Practice. doi:10.1177/1049731515614102.

Shrira, A., Palgi, Y., Ben-Ezra, M., & Shmotkin, D. (2010). Do Holocaust survivors show increased vulnerability or resilience to post-Holocaust cumulative adversity? Journal of Traumatic Stress. doi:10.1002/jts.20524.

Singh, A., Hays, D., Chung, Y., & Watson, L. (2010). South Asian immigrant women who have survived child sexual abuse: Resilience and healing. Violence Against Women. doi:10.1177/1077801210363976.

Smith, B., Dalen, J., Wiggins, K., Tooley, E., Christopher, P., & Bernard, J. (2008). The brief resilience scale: Assessing the ability to bounce back. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. doi:10.1080/10705500802222972.

Souri, H., & Hasanirad, T. (2011). Relationship between resilience, optimism and psychological well-being in students of medicine. Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences, 30, 1541–1544.

Stevens, J. (2002). Applied multivariate statistics for the social sciences. New York, NY: Routledge.

Stewart-Brown, S., & Janmohamed, K. (2008). The Warwick and Edinburgh Mental Well Being Scale; User Guide. Warwick: Warwick University. Retrieved from http://www.cppconsortium.nhs.uk/admin/files/1343987601WEMWBS%20User%20Guide%20Version%201%20June%202008.pdf.

Tennant, R., Hiller, L., Fishwick, R., Platt, S., Joseph, S., Weich, S., et al. (2007). The Warwick–Edinburgh mental well-being scale (WEMWBS): Development and UK validation. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 5(1), 63.

Theron, L., & Theron, A. (2013). Positive adjustment to poverty: How family communities encourage resilience in traditional African contexts. Culture & Psychology, 19(3), 391–413.

Thomas, S., & Hall, J. (2008). Life trajectories of female child abuse survivors thriving in adulthood. Qualitative Health Research, 18(2), 149–166. doi:10.1177/1049732307312201.

Tilki, M., Ryan, L., D’Angelo, A., & Sales, R. (2009). The Forgotten Irish. London. Middlesex University. Retrieved from https://eprints.mdx.ac.uk/6350/1/Tilki-Forgotten_Irish.pdf.

Ungar, M., & Liebenberg, L. (2005). The International Resilience Project: A mixed-methods approach to the study of resilience across cultures. In M. Ungar (Ed.), Handbook for working with children and youth: Pathways to resilience across cultures and contexts (pp. 211–226). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Ungar, M., & Liebenberg, L. (2011). Assessing resilience across cultures using mixed methods: Construction of the child and youth resilience measure. Journal of Mixed Methods Research. doi:10.1177/1558689811400607.

Werner, E. (1992). The children of Kauai: Resiliency and recovery in adolescence and adulthood1. Journal of Adolescent Health, 13(4), 262–268.

Werner, E., & Smith, R. (1982). Vulnerable but invincible: A study of resilient children. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Windle, G. (2010). What is resilience? A review and concept analysis. Reviews in Clinical Gerontology, 21(2), 152–169. doi:10.1017/s0959259810000420.

Windle, G., Bennett, K., & Noyes, J. (2011). A methodological review of resilience measurement scales. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 9(1), 8.

Wink, P., Ciciolla, L., Dillon, M., & Tracy, A. (2007). Religiousness, spiritual seeking, and personality: Findings from a longitudinal study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(5), 1051–1070.

Wolfe, D., Jaffe, P., Jette, J., & Poisson, S. (2003). The impact of child abuse in community institutions and organizations: Advancing professional and scientific understanding. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10(2), 179–191.

Woodhead, M. (2004). Psychosocial impacts of child work: A framework for research, monitoring and intervention. The International Journal of Children’s Rights, 12, 321–377.

Wright, M. O. D., Masten, A. S., & Narayan, A. J. (2013). Resilience processes in development: Four waves of research on positive adaptation in the context of adversity. In S. Goldstein & R. B. Brooks (Eds.), Handbook of resilience in children (pp. 15–37). New York, NY: Springer.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Liebenberg, L., Moore, J.C. A Social Ecological Measure of Resilience for Adults: The RRC-ARM. Soc Indic Res 136, 1–19 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-016-1523-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-016-1523-y