Abstract

Income distributions within countries vary tremendously in global comparison. While income inequality is generally higher in the United States than in Europe, extreme differences prevail in Sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America. Income inequality is particularly low in Scandinavia and Central East Europe, but also in Japan. In the last decades, global economic inequality between nation states has been declining while within-nation inequality has been increasing in many regions. The purpose of this paper is to explain the huge international variations in within-country income inequality, focusing upon the role of present-day ethnic diversity and historic ethnic exploitation (slavery)—two aspects rather neglected in most comparative sociological research. Three hypotheses about the origins and factors producing international differences in intra-national patterns of income inequality are formulated and tested on the basis of a newly created aggregate data set of 123 countries. Also a new indicator measuring historic ethnic exploitation on a global scale is introduced. In our empirical analysis, we describe the substantial differences in within-country income inequality on the global scale, and present evidence for the impact of historic and current ethnic structures as well as of political institutional factors both through descriptive and regression analyses. The results support the thesis of an impact of historic ethnic exploitation; it can be reduced by redistributive political institutions (welfare state, federalism, Communist systems). The effect of ethnic heterogeneity can be extinguished fully by these institutions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The purpose of this paper is to explain the huge international differences in income inequality within the countries of the world—a topic which has received surprisingly little attention. A short review of the relevant literature in the social sciences shows three facts. First, intra-national inequalities around the world are pervasive and gaining in weight compared to global inequalities between nations; second, there is a surprising lack of systematic work which considers macro-social and institutional determinants of intra-national inequalities; and third, it is evident that intra-national patterns of economic inequality are closely associated with ethnic differentiations.

As a basis for our own analysis we consider three strands of theoretical arguments. First, we start with a discussion of the concepts of class formation, social stratification and ethnic differentiation arguing that it is their interaction which is crucial for the emergence of economic inequality. Tying in with theorems from collective action approaches, we argue that ethnic heterogeneity and fractionalization are crucial factors in this regard. If in a society many different ethnic groups compete for recognition and resources, it will be harder for them to organize collectively on a class basis and to push forward their interests, particularly in regard to the labour market. Ethnic differentiation and fractionalization within a country make it more difficult for broad class-based organisations to develop. In addition, they reduce the feeling of all members of a society to belong together, and their readiness to accept welfare state programs of economic redistribution. As a consequence, income inequality will be high. Second, following institutional approaches we argue that historic ethnic exploitation, such as peonage, forced labour, and in particular the most extreme form, slavery, made long-lasting imprints on societies. This happened through the establishment of exploitative social and political institutions, which directly and indirectly affected the intra-national distribution of income. In most countries, slavery was connected with a highly unequal land distribution, and centralized, authoritarian political systems. Later on these factors inhibited the development of democracy and welfare state institutions. The consequence is that economic inequality remains extremely high in such societies till today. Third, we include theories and researches from political science which have shown that the degree of economic inequality can substantially be affected by political institutions and measures. Most relevant in this regard are the establishment of democracy, a federal constitution and a welfare state. They all tend to reduce the amount of economic inequality within a society. The same effect can be observed if a society has had a prolonged experience of State Socialism (Communism). The genuine contribution of this paper lies in showing for the first time the effect of the combined effects of ethnic stratification, historic slavery and egalitarian political institutions on economic present-day inequality.

2 State of Research

Theorists of globalization argue that intra-national differences in income today are less important than those at the global level (Beck 2002; Ziegler 2008). This thesis seems plausible given the extreme differences in incomes and standards of living between the North and South (Bourguignon and Morrison 2002; Milanovic 2005; Frazer 2006; Pogge 2007). However, this paper starts from the assumption that the investigation of intra-national differences in the distribution of income continues to be important due to three reasons. First, because between-country income inequality has been increasing from the beginning of industrialization process in the West, but is shrinking since the middle of the twentieth century (Firebaugh 2003); this is due mainly to the catching-up process of developing countries in Asia. On the other hand, economic inequality within nations remained stable or has been increasing in the last decades in many countries around the world (Goesling 2001; Milanovic 2005; Greve 2010) Overall world income inequality (as measured by the GINI coefficient) rose more or less continuously between 1820 and 1950, but levelled off between 1950 and 1990 (Bourguignon and Morrison 2002; Atkinson and Brandolini 2008). Second, intra-national economic inequality is still relevant because it is mainly at the national level where the social, economic and political processes determining income distributions are located (Weiss 1998; Stiglitz 2002; Haller and Hadler 2004/05; Reich 2008; Müller and Schindler 2008). Third, and connected with the second argument, is the fact that income distribution did not change similarly in the different countries of the world. In contrary to widespread assertions it did not increase everywhere but only in specific countries and world regions (e.g. the Anglosaxon and some post-communist countries, China, Israel); in some it even has decreased in the last decades (Frazer 2006, OECD 2008; McCall and Percheski 2010). However, one looks in vain for discussion of the inequality transition [the shift of inequality between nations to that within nations] in the traditional sociological literature on income inequality” wrote G. Firebaugh (2003: 92) in his comprehensive study on the topic. It is also surprising that the enormous differences between the countries in their internal economic inequality have not attracted more interest in the social sciences (see also Bradley et al. 2003: 195; DiPrete 2007).

Income and its distribution should be of central concern for sociology since it is one of the main determinants of life chances in modern societies (Jencks 2002; Pickett and Wilkinson 2009). Sociologists typically try to explain levels of personal or family income by individual or group-level variables, such as age and gender, education and class location, and household composition (McCall and Percheski 2010). They also use income as an independent variable to explain individual opportunities in the life course and over generations and social and political attitudes, health and happiness (For a summary see Kerbo 2012: 21–39). Some authors have applied specific theoretical perspectives, such as the neo-Marxist one (Wright 1985, 1997). Class position, in fact, is correlated significantly with income, but looking at it in isolation from other factors does not explain very much, and it is also not sufficient to explain changes in recent times (Kenworthy 2007). The huge international variations in inequality have also not been a focus of comparative research on stratification and mobility in the Weberian tradition (see e.g. Goldthorpe et al. 1987) which looked more for similarities than for differences across countries (DiPrete 2007). In general, there is a lack of research in sociology concerning income inequality as a macro-societal characteristic on its own and on trends in this regard (see also Neckermann and Torche 2007; Green 2007).

Very few sociological studies have been carried out on intranational economic inequality from a comparative and historical perspective. Gerhard Lenski (1973) investigated the development of systems of stratification through human history; he found a long-term trend toward rising inequality which, however, was reversed during the transition from agrarian to industrial societies; from this time on, inequality began to decrease. Cutright (1967) found a partial confirmation of this theory. Lenski sees the increasing division of labour and the granting of political rights to the people in the course of democratic revolutions as reasons for the trend reversal. Also Hamilton and Hirszowicz (1987) raise the issue of changes of stratification systems since pre-industrial societies but concentrate on differences between capitalist and former state-socialist countries. However, these were not the largest ones in a world-wide comparison; in addition, this distinction has become historically obsolete. State-socialist societies have in fact been able to reduce some inequalities, but new ones have come into existence (Connor 1979; Lane 1982; Voslensky 1984; Szelényi 1998). One general conclusion drawn by Hamilton and Hirszowicz (1987: 276f.) is very relevant in this context namely, that income differences by ethnicity have not disappeared.

Income distribution is certainly an important question for economics. But also in this discipline, only a few scholars have continuously written on this topic (e.g. Atkinson 1997; Atkinson and Bourguignon 2000; Sen 1973, 2001). Empirical studies about economic inequality focus on the impact of labour markets (Pontusson et al. 2002), of transactions on financial markets (Kus 2012) and of foreign direct investment (Mahutga and Bandelj 2008) on income distribution. These analyses and explanations are sound and relevant but many of them do not include in a systematic way important institutional socio-economic and political frame conditions (see also Lydall 1979; Bunge 1998; Green 2007).

A well-known theory of changes in economic inequality has been developed by the economist Kuznets (1955). He established a connection between the economic transformations occurring in the course of industrialization with changes in income inequality. Early industrialization leads to an increasing inequality due to the shift from agriculture to industry and the migration of population from rural areas to cities offering higher wages. As the urban population and the proportion of people working in industry and services later on increase and come to constitute a majority of the population, income differences decrease. Thus, income inequality in the long run will look like an inverted U-curve increasing first, but later on decreasing. This thesis has been submitted to many empirical tests. While some authors found a confirmation (e.g. Ram 1997; Higgins and Williamson 1999), it was rejected by others on theoretical, methodological and empirical grounds (Bowles 2002; Frazer 2006; Weede 2008; Moller et al. 2009). It was argued that Kuznets himself compared only three countries (Germany, UK, USA) in the period between the late nineteenth and mid-twentieth century; it is rather clear, however, that the levelling off in income inequality between 1914 and 1945 was due to other factors rather than industrialization (such as the world economic crisis of the 1920s/1930s, the world wars, and a restriction of international trade); the “East Asian miracle”, the rapid industrialization and growth of many countries in this region between 1965 and 1990, occurred without a corresponding increase of economic inequality; obviously, the deliberate political measures of the governments of those countries to promote a balanced growth (for instance, through the guaranteeing of high price supports for farm products, high levels of public investment in education etc.) were of decisive importance. Similar problems are connected with the more recent, widely-held view that globalization increases inequality. But globalization is connected with very different effects in different parts of the world; overall, there is no convincing evidence that it increases inequality—rather the reverse may be true (Weede and Tiefenbach 1981; Firebaugh 1999; Weede 2006; Nollmann 2006; Mills 2009).

Political scientists focus on the impact of political systems and their historical development on inequality (Ansell and Samuels 2010); the duration of state socialism (Milanovic 1998); the impact of welfare state arrangements and the power of labour unions. Most of these factors have in fact been confirmed as structures and forces leading to more equality (Korpi and Palme 1998; Alderson and Nielsen 2002; Freeman and Oostendorp 2002; Bradley et al. 2003; Kenworthy and Pontusson 2005).

A few economists and social historians have pointed toward factors which we will consider here to be particularly relevant for income inequality. Glaeser (2005) argued that ethnic heterogeneity impacts inequality both directly, since different ethnicities have different skill levels, and indirectly through political channels, as people seem to be less eager to transfer money to people from a different ethnic group. Particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa, ethnic divisions were often associated in a fatal way with civil wars and delayed economic growth (Easterly and Levine 1997). Several authors have suggested that colonialism and related systems of agricultural exploitation have had a strong effect on the development of institutions unfavourable to equality (Angeles 2007). Exploitative institutions such as colonialism and plantation slavery inhibited the development of voting rights, fair taxation systems, good systems of public schooling, and welfare state programs; thus, they led toward elitist and unequal societies (Sokoloff and Engerman 2000; Acemoglu et al. 2001; de Ferranti et al. 2004). A particularly important factor was the distribution of land in a time, when the majority of the population was still working in agriculture. Ewout Frankema has shown in a recent series of works that the historical, colonial patterns of land distribution in Latin America are decisive determinants of income inequality today (Frankema 2009a, b, 2010). Engerman and Sokoloff argued, in a similar vein, that the altering of the composition of the population in the colonized areas was crucial, namely the implanting of European populations who were greatly advantaged over natives in terms of human capital and legal status (Engerman and Sokoloff 2006).

Our own approach in this paper takes up several of the theses and findings of these authors. It is original, however, in developing a coherent theoretical framework concerning the relation between class formation, social stratification and ethnic differentiation, and their impact on economic inequality. Its focus is on comparisons of present-day patterns of economic inequality between a large number of countries around the world. Some of the most significant changes in patterns of income inequality within specific countries (or groups of countries) are dealt with in a companion publication.Footnote 1 A focus on present-day differences between countries is also justified by the fact that the huge differences in the relative ranking of countries in terms of their internal income inequality have not changed since long (see also Gottschalk and Smeeding 1997; Korzeniewicz and Moran 2009).

3 Theoretical Considerations and Hypotheses

In this section, we first discuss the concept of ethnicity and the interaction of class and ethnic cleavages on economic inequality; then, we introduce the concept of slavery and its relevance for historic and present-day economic inequality; finally, we discuss the relevance of present-day political institutions and their historical development. For each of these aspects, hypotheses are formulated.

3.1 Ethnicity as a Determinant of Socio-economic Inequality

Ethnicity is, like class and stratification, an important and widely-treated topic of sociological research. However, the fact that there exists a very close connection between these two phenomena has rarely been noted and investigated. Some sociological studies on stratification and inequality explicitly exclude ethnic differentiation; classical examples are Sombart (1906) and Schumpeter (1953). If the interaction between the two processes is considered, one of the processes is usually seen as basic, the other as secondary. In Marxist and neo-Marxist works, ethnic-national inequalities are treated as secondary to those of class (e.g. Cox 1959). Conversely, theorists of ethnic group formation consider differentials in the power and privilege of different ethnic groups as the main factor producing inequality; the class conflict is reduced to an eternal race conflict (Gumplowicz 1883). Present-day primordialist and sociobiological theories assume that ethnicity is deeply rooted historically, even biologically (For critical reviews see Dittrich and Radtke 1990; Coates 2004; Law 2010). A systematic focus on international differences and macro-social institutional conditions is missing also in sociological studies which provided many useful hypotheses and empirical material on ethnic stratification within nations (Shibutani and Kwan 1965; Porter 1968).

In this paper, we presuppose a broad definition of ethnicity which includes not only ethnicity in the bio-social sense (common social descent and skin colour, denoted as “race” in American sociology), but also two cultural characteristics, language and religion. Further, we assume that ethnicity has objective and subjective components in all these regards; beliefs and feelings of belonging together are essential for ethnic groups, not only objective characteristics and facts like inheritance, language and religion (Weber 1964/I: 303f.; Shibutani and Kwan 1965: 38ff.; Smith 1987; Anderson 1983). Thus, we define ethnic groups as groups of people within a larger political community (but also groups living in more than one state), which share one or more of these three characteristics and which understand themselves as a community or “we-group” (see also Ringer and Lawless 1989; Waters and Eschbach 1995; Coates 2004; Law 2010). From this point of view, the difference between the bio-social and cultural definition of an ethnic group is relative. Language and religion are learned by humans very early in childhood and people cannot get fully rid of their imprint in later life (for the case of language see Schöpflin 2000; Joseph 2004; Haller 2009). A very close connection between ethnicity, language and religion also exists in institutional-historical terms; a common language or religion is often the main marker of an ethnic group, and religion and languages themselves are highly inter-correlated.

Membership in a clearly defined ethnic group is associated with strong feelings and loyalties in a similar vein as it is the case in kinship groups (Van den Berghe 1978; Horowitz 1985; Smith 1987; Dittrich and Radtke 1990: 261; Ringer and Lawless 1989: 3; Hagendoorn 1993). Ethnic groups are not per se differentiated from each other in vertical terms; they are inclusive social categories comprising people of all social strata. However, when ethnic groups within a society are distinguished from each other also in levels of education, occupational distributions and social prestige, an ethnic stratification emerges. In the extreme case, clearly recognizable “ethclasses” evolve. In such societies, discrimination and racism from the side of stronger and privileged groups strengthens existing ethnic differentiations. A high level of internal ethnic differentiation in a society has significant consequences. Several studies show that the degree of social integration is lower, and social problems are more frequent in ethnically differentiated neighbourhoods and societies (Alesina and La Ferrera 2005; Putnam 2007).

Ethnic diversity is a central feature of most present-day societies around the world; only about one fourth to one third of all independent nation states can be considered as being ethnically homogeneous; all others contain sizable ethnic subgroups, some even hundreds of them (Levinson 1998; Fearon 1998; Vanhanen 1999; Alesina et al. 2003). Looking at Table 1, it is evident that ethnic differentiation and income inequality are closely correlated. Most European states are characterized by relatively low degrees of inequality, and show high relatively high levels of ethnic homogeneity, while the reverse—high degrees of ethnic heterogeneity and high economic inequality—can be observed in most Sub-Saharan African and Latin American countries.

3.2 The Interaction Effect of Ethnic Differentiation, Class Formation and Social Stratification on Economic Inequality

In the sociological tradition of Marx and Weber, class relations and social stratification are the central processes producing and reproducing socio-economic inequality (Weber 1964/I: 223–225; Giddens 1973; Wright 1985; Goldthorpe et al. 1987). In most western societies, class conflict has been institutionalized in the form of regular negotiations between employers and workers; their relations can be characterized as antagonistic cooperation (Marshall 1950; Dahrendorf 1959). A society can be considered more or less as a “class society”; such a society presupposes a considerable degree of class consciousness and class organization but rather a moderate level of income inequality. One further reason for this fact—besides the greater strength of the working and lower classes—is that in an ethnically homogeneous society, it will also be easier to develop a strong welfare state since all citizens are considered as belonging to one and the same “societal community”. Research has shown that class stratification still is an important basic determinant of many aspects of life in all developed societies (Kerbo 2012); this thesis is corroborated by the recent increase of income inequality in many Western countries (Goldthorpe and Marshall 1992; Bouffartigue 2004; OECD 2008).

Closely related to, but distinct from class formation is the process of social stratification. The formation of social strata—Ständebildung as it was called, in Weber’s historical sociology (Weber 1964)—includes the tendency of social groups to establish distinctions between them and other groups in terms of honor and prestige. To think and to act in terms of social hierarchies is a characteristic of all human societies (Ossowski 1972; Schwartz 1981). The main processes whereby a system of social stratification reproduces itself are homogenous marriage patterns producing a specific family status and the intergenerational transmission of status group membership (Schumpeter 1953; Weber 1964; Haller 1981, 1983). The process of stratification is also closely connected with processes of social inclusion and exclusion, degradation and discrimination (Sennet and Cobb 1972; Archibald 1976; Neckel 1991; de Botton 2004).

We assume that class formation and social stratification are closely related to processes of ethnic differentiation in ethnically heterogeneous societies. In order to grasp the interaction between these three processes more clearly, we employ ideas from collective action theory. An ethnic group comes into existence only if it recognizes itself as a group with a specific name and is recognized as such by others. Cultural, political and military leaders play a significant role in this process; they often use the ethnic card in order to win supporters and gain power (Smith 1987; Haller 1992; Scheff 1994; Guibernau 1996; Eder et al. 2002; Wimmer 2012). Identity-based conflicts resulting from ethnic cleavages often are more difficult to resolve than class conflicts mainly based on material interests (Williams 1994). In fact, ethnic and ethnic-national conflicts are present in many societies around the world; they account for some of the most bloody and long-term incidents of collective violence and civil war since 1945 (Gurr 1993; Vanhanen 1999; Lake and Rothchild 1998; Cordell and Wolff 2010; Mann 2005). It is plausible that a close relationship exists between class and stratification structures and ethnic differentiation. If specific social classes are homogeneous in ethnic terms, it will be easier for them to develop a consciousness of their common interests, to organize themselves collectively and to act in a concerted way. This is typically so in the case of the upper classes (For the case of the USA see Baltzell 1958). Conversely, ethnic differentiation will be a handicap for the development of class consciousness and action (Bonacich 1980). This will be particularly so in the lower classes. They are much larger in numbers than the upper classes, the probability of internal heterogeneity is higher and the development of a common consciousness is more difficult for them (Offe and Wiesenthal 1980). All this will be reinforced in the situation of a working class which is internally divided by ethnic lines. In such a case, collective organization will pass over from strategies of usurpation to strategies of social exclusion (Parkin 1979), that is, fights for the creation and preservation of privileges of certain groups within the working class.

Also social stratification and ethnic differentiation interact closely. It is a definitional characteristic of both social strata and ethnic groups that they reproduce themselves through intergenerational transmission and homogamous or endogamous marriage patterns. Ethnic differentiations involve processes of dissociation creating social distance to others (Shibutani and Kwan 1965: 42; Haller 1983: 103–105; Fearon 1998; Wimmer 2012). The relations between ethnic groups per se are not structured in a hierarchical way. However, there exists a communicative and social distance between ethnic groups, based on different languages, religious world-views and life-styles; this distance reduces feelings of togetherness and reciprocal solidarity. Now, if (vertical) social stratification and (horizontal) ethnic differentiation coincide, class and ethnic group membership will strengthen each other and—in the extreme form—constitute more or less clearly defined “ethclasses” (Marger 1978). At the same time, the distance between the different groups and strata will be pronounced particularly. The feelings of distance are strengthened by emotions like envy and status anxiety (Schoeck 1966; de Botton 2004). Members of middle and higher strata and privileged ethnic groups may fear that economic crises, immigration and/or demographic shifts will threaten their status (Stryker 1980; Gerhards 1988; Kemper and Collins 1990).

Out of these considerations, the following hypothesis is proposed on the basis of collective action theory related to ethnoclass formation:

Hypothesis 1

Inequality of income will be more moderate in ethnically homogeneous societies than in ethnically heterogeneous societies because the collective organizations of the working and middle classes are both able to pursue their interests in an effective way and a high level of social and cultural integration is conducive to political redistribution measures.

3.3 The Institution of Slavery and its Long-Term Effects

Slavery may be defined as a system or institution in which human beings (the slaves) are treated and used by other people (their masters) as their property and forced to work and to perform any kind of service for them. They are deprived of their free will, thus bereaved of personal autonomy and dignity, the central element of human beings and the basis for self-consciousness and happiness (Honneth and Joas 1980; Taylor 1992; Sen 2001; Haller and Hadler 2004). They have no control over their own life, cannot decide about their work, and often have no right to marry and to establish a family. In most cases, the slave status is passed on over generations (Miers and Kopytoff 1977: 3–4; Bley et al. 1991: 3; Berlin 2003). Two elements were essential for slavery. Violence and the destruction of social identity by bereaving persons of their kinship (Meillassoux 1975; Bley et al. 1991: 15; Pfaff-Giesberg 1955: 15−18). In fact, slaves were sold and bought on markets like cattle (Grant 2010: 92−93). The institution of slavery was connected with extreme forms of exploitation, the suffering of hundreds of millions of people, the displacing, expulsion and extermination of whole tribes and peoples, the disruption of couples and families, and the abuse and exploitation of men, women and children. Extended slavery existed since the antiquity far into the twentieth century and on all continents (Dal Lago and Katsari 2008; Grant 2010).

Such an exploitative social system cannot have other than a profound impact on society, as well as on the masters and slaves themselves. We can speak of a “slave holding society” if this institution pervaded society as a whole and was essential for its functioning over time. Societies of this sort existed far into the Modern Age on two (sub-) continents, in Sub-Saharan Africa and in America. In close connection with the rise of capitalism between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries, these two continents became closely interwoven by the Atlantic triangular trade. European manufactured goods (textiles, arms) and “luxury” products (alcohol and glitter) were brought by ships to west Africa; from there, the ships were re-charged with slaves; in this so-called “middle passage”, about 12 million slaves were transported to the Americas and sold there; finally, the ships brought back raw materials (e.g. silver) and agricultural products (e.g., sugar, coffee, tobacco) to Europe. Slave hunting in Sub-Saharan Africa destroyed the political communities and societies existing there and depopulated large areas, and in the Americas new types of exploitative slave-holding emerged which had never existed before on earth (Wallerstein 1974; Berlin 2003; Engerman and Sokoloff 2006; Frankema 2009a, 2010). The negative consequences of slavery on society have been well recognized by political thinkers in the early modern age, such as Charles Montesquieu (1689–1755), Thomas Jefferson (1743–1826), the third president of the United States, and Alexis de Tocqueville (1976 [1835]; see also Pfaff-Giesberg 1955: 74; Illife 1997: 172ff.; Engerman et al. 2001; Schmitt 2008: 11). Given the pervasive impact of slavery on the social, economic and political structure of a society, it is obvious that its effects did not disappear after only one century which corresponds to three of four generations; important events and experiences make a long-lasting imprint on societies (Assmann 1992; Eyerman 2001).

In addition, historical research indicates that the liberation of slaves was no definite break with the former state but led “to a transformation of the dependence band, rather than to its complete elimination.” A quick look on three concrete historic cases can illustrate the logic of this process (Pétré-Grenouilleau 2008). In South Africa, from 1809 on, children and youth continued to be held in bondage by their masters on exploitative work contracts, interpreted as “apprenticeship” (Bley et al. 1991: 147−159). Later on, black people were liberated, but their freedom concerning place of living, types of work were restricted in many ways. In1910 a unique system of segregation and exploitation, Apartheid, was established as the law; it lasted till the 1990s. Also in the US-South, in the first decade after liberation, the new rights of the blacks were not taken seriously; many of them worked as share crappers on small pieces of land and fell into a kind of bondage to the owners (Temperley 1977: 123ff). Later on, an informal terror of radical, right-wing enemies of abolition organized themselves, for instance, in the Southern Ku-Klux-Klan (Eyerman 2001: 33ff.). From 1876 on, the Jim-Crow Laws prescribed a formal separation between whites and blacks in public institutions and spaces under the embellishing label separate but equal; some of them were effective till 1964. Their consequence was a clear discrimination of blacks. They were provided with inferior public facilities and services; pushed aside into urban ghettos; their employment and occupational opportunities worsened as a consequence of residential segregation; and their suffrage was undermined by restrictive measures (Blassingame 1972; Temperley 1977; Meuschel 1981; Massey and Denton 1990; Massey 2009). The effects of slavery and racial segregation on the collective memory among African-Americans were pervasive (Eyerman 2001).

In Latin America, particularly in Brazil, a strict separation between whites, blacks and coloured people was impossible given the fact that the whites were only a small minority so that close relations were unavoidable, including widespread miscegenation. Here, the specific idea of a harmonious co-existence, even an active intermixing between the races was developed whose outcome, the mestizos and mulattos, would be a new kind of man, the typical Brazilian (Hofbauer 1995: 78ff.; de Holanda 2009). In official political ideology, this position asserted itself in the concept of racial democracy. Nevertheless, the former slaves were largely left to themselves, lost security and means of living. On the countryside, they fell into poverty; in the towns they concentrated in the favelas. They were excluded from education, social and cultural life and became object of racist prejudices and actions; in the growing industry, immigrant workers were preferred to them. A vicious circle unfolded between the legacy from the slave huts and the exclusion of blacks and mulattos from new forms of work in the industrial society (Schmitt 2008: 59).

A third form of aftereffects of slavery can be found in Sub-Saharan Africa, north of the Republic of South Africa. This whole area was affected in an extremely negative way by slavery. Between the twelfth and nineteenth centuries 12 million of people or more were captured as slaves by Europeans and even more by Arabs (N’Diaye 2010). The consequences was a depletion of large areas of people; the rise of aggressive African regimes which cooperated in manhunt for slavery, and the break-up of social bounds and a decline of inherit social customs and relations (Meillasoux 1975, Miers and Kopytoff 1977; Bley et al. 1991; Illife 1997; Berlin 2003; Dal Lago and Katsari 2008). The emergence of aggressive war-lords and authoritarian corrupt political leaders in the new independent African states from the 1960s on must also be seen as a consequence of this dire heritage (see also Easterly and Levine 1997).

Out of these considerations, the following hypothesis is proposed, relating to the effects of institution of slavery:

Hypothesis 2

Economic inequality in a society will be the higher today, the more extensive and exploitative the institution of slavery has been in historical times.

3.4 The Relevance of Modern Political Institutions

In the first section, we have mentioned authors who see the political system as an important determinant of economic inequality. In this political-institutional perspective four aspects of a political system are relevant. The democratic character of a political system, the kind of its constitution (centralist or federal), a history of Communism, and the level of welfare state spending.

The basic principle of democracy is to establish equality between all citizens concerning access to political offices and power and to provide them with influence on the substantive direction of politics. Every citizen has one and only one vote; thus, also members of the less privileged classes and strata can bring their interests to bear in politics (Graubard 1973; Rubinson and Quinlan 1977). Democracy, furthermore, is important because it is closely related with “good governance”, the quality of societal and political institutions (Kerbo 2006: 35ff.). It is indicated by the rule of law, efficient and responsible public administrations, stability of governments, and the absence of clientelism, corruption, and misuse of public resources (Rodrik and Subramanian 2003). An important aspect of democratic systems in regard to income inequality is the possibility to establish independent interest organizations, particularly unions and political parties. Thus, democracy constitutes a decisive institutional mechanism leading toward greater equality. Classical social and political theorists such as Montesquieu and de Tocqueville used the concepts of democracy and equality almost interchangeably. Older cross-sectional studies on the relations between democratic government and equality, however, did not found unequivocal support for a close connection (Weede and Tiefenbach 1981; Hughes 1997). However, by controlling for the length of the democratic experience of countries, Muller (1988) could establish a strong relationship. A significant effect has also been shown for one important characteristic of democratic societies, the existence of independent unions (Freeman and Oostendorp 2002). Seen from a world-historical perspective the positive relation between democracy and equality seems clearly and unequivocally positive (see also de Tocqueville 1945 [1835]; Lenski 1973; Rubinson and Quinlan 1977). We expect ethnic differentiation and democracy to be interacting towards income inequality. A democratic constitution will reduce inequality in ethnically heterogeneous nations since ethnic subgroups then have a better chance to organize themselves. In addition, it is a matter of fact that in democracies violent ethnic conflicts are less frequent than in non-democratic states (Powell 1982; Gurr 1993; Stavenhagen 1996; Schlenker-Fischer 2009).

A second rel evant factor is the centralistic or federal structure of the political system. Federalism represents a horizontal division of power between the central state authorities and regional-territorial sub-units (Scott 2011). In a federal system, local or provincial governments can decide autonomously about political issues. Since many ethnic-national groups are concentrated on certain territories, federalism will often de facto be an instrument for their autonomy. We expect, therefore, that economic and social inequality will be lower in nation states with a federal constitution than in those with a centralized constitution (see also Kößler and Schiel 1995).

A third aspect of the political system with significant effects on economic equality was the establishment of Communist regimes in Russia in 1917, in China in the 1940s, and in Eastern Europe and a few other countries in the early 1950s. By abolishing private ownership of land and means of industrial production, socializing of money and banking services, establishing a system of planned economy, guaranteeing full employment, and providing comprehensive public education, health services and housing comprehensive equality was established, although standards of living began to ley behind western countries due to lack of competition and reduced capacity of innovation (Lenski 1978; Connor 1979; Weede and Tiefenbach 1981; Lane 1982; Szelényi 1998). In addition, the members of the leading Communist Nomenclatura established themselves as a “new class” with many privileges (Djilas 1957; Konrad and Szelenyi 1978). Given the fact that Communist regimes lasted for half a century (in the Soviet Union over eighty years), the principle of equality has been deeply rooted in society, outlasting even the collapse of the system in 1989/90 (Riedl and Haller 2014). However, the fast transition from autocracies to democracies, oligarchic or new autocratic systems and from planned to free market economies, led to an increase of objective inequality, particularly in Russia and China.

A fourth aspect of the political system affecting the distribution of incomes in western, capitalist societies is the welfare state. Its aim is to provide political force to the idea of “social equality”—one of the three fundamental forms of citizens’ rights according to Marshall (1950; see also Stephens 1979; Korpi 1983; Alber 1987; Boix 2003; Kuhnle 2004; DiPrete 2007). Two dimensions are relevant in this regard. The character of the welfare state and the extension of its transfers and services. The first dimension concerns the question if welfare state provisions are seen more as subsidiary elements, supplementing individual efforts only in cases of specific proven need, or if they are seen as basic rights to which every citizen is entitled in specific life circumstances. The first type (represented by the USA) is called a liberal or marginal welfare state; the second (represented mainly by Scandinavian states) a universalistic or social-democratic welfare state (Esping-Andersen 1990). It is obvious that a universal welfare state will provide more services and transfer payments to the citizens than the first (see also Lee 2005). However, the difference between these types of welfare states in the advanced western societies is small compared to those between all of them and the marginal public benefits and services in most poor countries of the global South. In Sub-Saharan Africa, Pakistan and Bangladesh, social security expenditures constitute only 2–4 % of GDP, in India and China 4–6 %, but in the USA and Japan 15–20 % and in Europe 15–30 % (ILO 2010). Thus, it can be expected that the strong welfare state in advanced societies is a decisive factor contributing to socio-economic equality.

Ethnic differentiation can prove important in this context. It can be expected that it is easier to develop an extended welfare state in ethnically homogeneous nation states because it presupposes a feeling of togetherness and solidarity in the whole population. The development of such welfare states will be furthered significantly by strong unions based on a coherent working class. In ethnically heterogeneous countries, e.g. the US, there is less support for public provision of welfare (Glaeser 2005; Alesina and Glaeser 2005) because people are “less willing to support transfers to those who are ethnically different, or because ethnic differences provide a means of demonizing policies that help the poor” (Glaeser 2005: 8). Out of these considerations based on characteristics of the political system and institutions, we propose the following, third general hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3

Societies which are democratic, have a federal constitution and an extended welfare state, and societies with a history of Communism, will exhibit a lower level of economic inequality than societies without these characteristics. The inequality-increasing effect of ethnic heterogeneity will also be diminished in such societies.

4 Data, Variables and Methods of Analysis

The basis of our analysis is a newly created dataset which includes 123 countries of the world for which reliable data on income distribution and its potential impact factors were available. Despite the cross-sectional data used, our analysis offers four significant advances compared to the studies quoted in the foregoing section: (1) It includes a much larger set of countries than most prior studies, covering most major macro-regions around the world; (2) it makes use of a new, reliable measure of income inequality (Solt 2009); (3) it includes a new index developed in order to record the historical experiences of slavery; and (4) it tests the effects of these dimensions related to ethnicity together with political institutional variables. The variables used are described in the following; an overview on them is given in Table 2.

The dependent variable is the GINI coefficient of income distribution, the most frequently used indicator for economic inequality. It gives a general indication of the amount of income inequality within a country and varies (in principle) between the lowest value 0 and the highest value 100. The World Institute for Development Economic Research of the UN University (UNU-WIDER 2008) provides a large collection of data for about 150 countries across different periods. We used the improved version of this data-set from F. Solt (2009) capturing the distribution of disposable household income. In order to balance out short-term variations, we calculated mean values for the years 2000 to 2005 for each of the 123 countries. The GINI coefficient is closely connected with measures of inequality focussing upon the proportion of income which the different groups of a population receive, as measured by income deciles (see Table 3).

Ethnic differentiation was captured by an index of Ethnic Fractionalization (EF) developed by James D. Fearon (2003). He defines ethnic fractionalization as “the probability that two individuals selected at random from a country will be from different ethnic groups. If the population shares of the ethnic groups in a country are denoted p1, p2, p3…, pn, then fractionalization is \(F = 1 - \sum\nolimits_{i}^{n} {pi^{2} }\)” (Fearon 2003: 208). If a country is perfectly homogeneous, it will be 0, if there are two groups one of which is 95 % and the other 5 % of the population, the value will be 0.10; if the two groups each amount to 50 % of the population the value will be 0.10; if there are three groups, each of 33 %, the index is 0.67, and so forth. This index has the advantage that it covers not only the number of groups but also their population shares. Certainly, ethnic diversity may lead to conflicts more often if a few strong ethnic groups compete with each other, if one large group dominates many small others, than if many small ethnic groups co-exist in a country (Alesina et al. 2003; Fearon 2003). This aspect is not captured by this measure of ethnic fractionalization. In our first regression analysis, however, we introduce also an indicator for ethnic conflict (EC). Data used to measure this dimension were taken from Tatu Vanhanen (1999). It is based on two sub-indicators. The degree of institutionalization of ethnic conflict (existence of ethnic parties and other organisations) and the violence of ethnic conflicts (including rebellions, ethnic guerrilla and civil wars). The index EC covers the period 1990–1996 and varies from 0 in Iceland, Luxembourg and South Korea to 140 in Croatia, Burundi and Guatemala.

Measuring the historical importance of slavery was the most challenging task of our work. Most studies about slavery are usually focussing on specific countries or continents and none of them includes an overall quantitative measure. Thus, a new index for the measurement of the historical importance of slavery and similar forms of ethnic exploitation was developed, called “historical ethno-class exploitation”. These data were collected from a wide variety of sources, including handbook and encyclopaedia articles; historical, anthropological and sociological works on slavery in whole continents and single countries.Footnote 2 Since many of the present-day countries around the world did not exist in the nineteenth century, they received the value of the larger state or empire of which they then were a part (e.g. many African states) or that of similar countries in the region (e.g. Middle East Arab-Muslim countries, Central-Asian republics). The index “Historical Ethnio-class Exploitation” (EE) was constructed out of the following three sub-indices:

-

(a)

The existence of slavery or comparable forms of exploitation (such as serfdom or peonage) in a country and the time of its abolition by law. With this dimension, we want to capture the existence and historical proximity of these forms of exploitation in a country. Five categories were distinguished: 0 (No slavery or abolition of it before 1800); 1 (Abolition between 1800 and 1849); 2 (Abolition between 1850 and 1899); 3 (Abolition between 1900 and 1949); 4 (Abolition 1950 and later). These data were not difficult to obtain since the abolishment of slavery occurred usually through an official decree or law. Slavery was abolished on the territory of most European States before 1800, although the imperialistic nations continued with the slave trade around the world (the British Empire till 1807, France and other countries till 1848); it persisted in the form of serfdom in East Europe (Moldavia, Walachia, Russia) till the mid-nineteenth century. In Latin America, slavery was abolished in the first half of the nineteenth century (in Brazil only in 1888), in the southern states of the USA in 1865. In most African nations, slavery was abolished between the mid-nineteenth and mid-twentieth centuries, similarly to East Asia. The latest to abolish slavery were some Arab-Islamic states in North Africa (Mali, Mauritania) and the Near East (Saudi Arabia and United Arab Emirates 1962/64). This concerns to the fact that slave trade and exploitation in this region were lasting for over a millennium.

-

(b)

The quantitative weight of slavery and similar forms of exploitation in a country. This dimension was measured by the proportion of the enslaved people among the whole population around 1850. Since most historical sources only provide estimates but not exact proportions in this regard, the percentages were reduced to categorical variables as follows: 0 (0 %); 1 (1–15 %); 2 (16–35 %); 3 (36–45 %); 4 (46–60 %); 5 (61 % and more). The highest proportions of enslaved people were living in some Sub-Saharan African countries (over 60 % in Namibia, Lesotho), very high proportions also in Latin Amerika (Bolivia, Peru etc. 46 % and more, Brazil 31–45 %) and some Arab-Islamic states (Saudi Arabia etc.)

-

(c)

In different societies and regions, different forms or types of slavery in terms of its exploitative character were practised. Here, we distinguished four categories: 0: No exploitation;

-

1.

Serfdom, peonage and similar forms of enforced labour. In these relations, exploitation was practised by binding the rural population to their land and constraining them to work for the landlord. Exploitation, however, was restricted in two regards: (a) not the whole labour power of a person had to be provided to the landlord and the serfs; to work only a part of the year for the landlord; (b) only certain members of a family or village had to contribute labour power. This form was practised mostly in Europe and abolished in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries (in Russia only in 1861).

-

2.

Apartheid, a comprehensive legal, political and socio-economic discrimination and exploitation; it existed in extensive form in South Africa and, to a weaker degree, in the US-South.

-

3.

Extrusive slavery; here, slaves were made within the own society or, when imported from other societies, were integrated into the destination society. Thus, they were better integrated into society.

-

4.

Intrusive slavery, the most exploitative and cruel form of exploitation. Here, slaves were imported from other countries or continents and used mainly as labour power. Due to their complete uprooting from their native lands and societies, the slaves had little power to escape or to organize and protest against their exploitation.

-

1.

The resulting summary index “Historical Ethno-class Exploitation” (EE) varies between 0 and 13 (practically, the maximal value was 11) and provides a plausible ranking. Many European countries have the value 0; on top are African and Latin American countries (Lesotho, Namibia and South Africa with the value 11, Jamaica and Swaziland 10, Brazil and other Latin American and African countries 9) (Table 5 of “Appendix” presents the figures for all countries).

Five variables were included to capture the history and character of the political system of a country:

-

1.

Tradition resp. degree of democracy Here, we used the data set developed in the Polity IV Project (Marshall et al. 2010). A country’s democratic tradition is measured by the number of years between 1960 and 2010 in which it was democratic or autocratic. The available data consist of a ten-point-scale. Due to violations of the assumption of linearity and problems with multicollinearity with the variable including extended categories, we dichotomized this variable into non-democratic (1–6) and democratic (7–10) countries. We have to keep in mind, however, that this strategy might lead to an underestimation of this effect.

-

2.

Federalism We adopted data from the Polity IV Project (Marshall et al. 2010) measuring the existence or absence of elections at the level of sub-state administrative-political units (local or regional). Its categories are: (0) no elections at sub-state level; (1) executives of sub-unit are appointed by central government, legislative body is elected; (2) both executive and legislative body in sub-state units are elected.

-

3.

Communism The principle of equality is inherent to socialist political systems. Therefore, we assume that in state-socialist countries income inequality is lower and that it is also lower in former state-socialist countries because the ideal of equity is still more present in collective conscience and in social reality, as outlined before. Data was taken from a set developed by the Harvard School of Public Health, Boston/Massachusetts (Govindaraj and Rannan-Eliya 1994); the variable distinguishes two categories: 0 no Communist past, 1 Communist past or present.

-

4.

Social spending This variable gives information about the extensiveness of a country’s welfare state which might redistribute income and reduce economic inequality. It was measured by the percentage of public social security expenditure (excluding health) as a percentage of GDP per capita. The data, referring to 2000 (in some cases more recent years), were taken from the World Social Security Report 2010/11, published by the International Labour Organization, Geneva 2010. It varies from 010 (Uganda) to 22.2 (Sweden).

In addition to these variables, we included the following two intervening variables as control variables. Land inequality: Inequality in terms of the land distribution represents a key component of wealth and means of production. The distribution of land tenure today depends on the historically developed rights and opportunities to acquire, inherit and accumulate land property as well as on the level of development of the agricultural economies; it is also closely related to the existence of historical slavery. Since reliable data for land distribution are not available for a large number of countries, we used as a proxy for it the index “Proportion of family farms in percent of all agriculturally used area, compiled by Vanhanen (2003) as part of his index of Power Resources.

-

Gross domestic product per capita (GDP per capita) The relevance of this indicator follows from the famous Kuznets thesis which states that the historical development of economic inequality follows an inverted U-curve. It is primarily a control variable in our analysis, since a cross-section of countries with differing levels of GDP per capita cannot substitute a dynamic analysis of changes through time. In order to grasp the thesis of the U-curve, we introduced the logarithmic value of GDP per capita as a linear and as a quadratic term.

The hypotheses of this paper are assessed by multiple regression analysis testing first for the effects of ethnic fractionalization, and ethnic conflict controlling for GDP per capita. This model tests Hypothesis 1, deduced from collective action theory which incorporates the effects of ethnic heterogeneity and its interaction with class formation and social stratification, at least in an indirect way.Footnote 3 In the second model, we include our new index of historical ethno-class exploitation; thus, this model tests our second hypothesis, related to the effect of exploitative social-structural institutions on income inequality. In the final model, the political system variables are controlled for. Thus, here we carry out a comprehensive simultaneous test of all three relevant structural and institutional factors which has never been done in a similar way before. We use robust regression analysis in order to assess the explanatory power of our main independent variables, relating to ethnic fractionalization (EF), historical ethno-class exploitation (EE) and the political system variables in a reliable way. A modern MM-estimator in the MASS-package for R is used in order to account for outlier cases, which is important given the restricted size of our sample (Alesina and Glaeser 2005, 2002). A serious methodological problem in these analyses was the fact that most independent variables were inter-correlated thus leading to problems of multicollinearity. The respective data are presented in Table 3. We can see that particularly the correlations between GDP per capita and some of the political system variables (Democratic Tradition and Social Spending) are rather high (0.66 and 0.73 respectively). Therefore, we excluded GDP p.c. from model III. In this final model the VIF values (Variance Inflation Factors) were between 2 and 2.5 for the effects of Social Security expenditure, Democratic Tradition and Ethno-class Exploitation and the tolerance for these effects varied between 0.4 and 0.46; these are values just acceptable from the statistical point of view.

5 Empirical Results

In this section, we present our empirical results in three steps. First, we give a descriptive overview on income inequality and our main ethnic structural characteristics, historic ethnic exploitation and present-day ethnic differentiation. Second, we describe in more detail the correlations of the selected ethnic-structural and political-institutional factors with the level of income inequality. Third, we present the findings from robust regression analysis which allows us to test our hypotheses.

5.1 Descriptive Analysis

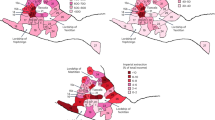

The degree of within-country income inequality for all countries where data is available is depicted in Fig. 1a and Table 1. They provide a general overview, clearly indicating the distinct role of Europe in terms of its low level of income inequality compared to the clustered centers of extreme global within-country inequality in Latin America and Sub-Saharan Africa. Figure 1a also shows that countries where no data on income inequality is available—and where incomes are presumably highly unequal as well—are not randomly distributed but located almost exclusively in Africa and the Middle East. Table 1 allows a more detailed country by country inspection of within-nation income inequality, distinguishing between income inequality in West and East Europe, the Americas, Africa and Asia. One can see that in West and East Europe, about half of the countries have rather low Gini values (between 24 and 30). Scandinavian countries like Sweden and Denmark are the most equal worldwide, while Portugal is the most unequal in terms of income distribution within West Europe and Turkey in East Europe. It is no incidence that in historical times in both these countries considerable numbers of slaves were used (The other imperialist nations practiced slavery only in their colonies). Income inequality in the former Soviet countries of Eastern Europe varies considerably more, ranging from 25 in the Czech and Slovak Republics to about 40 in Russia and Georgia. Latin American and Caribbean countries have the highest median values (between 49 and 60) but there exists a clear distinction between the bulk of highly unequal Latin American countries with Bolivia, Haiti and Brazil on top, and the somewhat less unequal North American countries USA and Canada. The latter two, however, are quite distant from each other. Canada has a similar rather low economic inequality as many west European countries. Compared to Latin America, African countries show a slightly lower median value (about 43) but also feature some of the most extreme cases of income inequality. Namibia with an extremely high GINI of 74 is on top of all countries, but also the republic of South Africa and its neighbor countries score very high (GINI’s 58–63). On the other side, two African countries (Ethiopia and Ruanda) are rather equal (Gini’s about 30) and also most North African Arab countries show moderate levels of inequality. Asia, again, shows quite a different picture. The most unequal country Malaysia is comparable to the less unequal Latin American and African countries but Japan with a surprising low GINI of about 25 belongs to the most equal countries worldwide. All other Asian countries are distributed between these two extremes, with China in the upper and India in the lower group. Thus, at least half of all Asian countries rank below the United States; even India which is interculturally highly differentiated in ethnic terms has a relatively low value of 33. Thus, they can be considered as being fairly equal—at least in global comparison.

Figure 1b, c indicate the geographic patterns of income inequality on a global scale as well as the distribution of historic ethnic exploitation and present-day ethnic fractionalization. It is obvious that both are quite associated with the distribution of historic ethnic exploitation and present-day ethnic fractionalization. Historic ethnic exploitation—most pronounced for example in Brazil, Central America and West Africa, and ethnic fractionalization, most prominent in all Sub-Saharan-African countries, coincide with unequal or even highly unequal income distribution in many world regions. Countries like India, Bangladesh and Kazakhstan or Uzbekistan deviate from this pattern insofar as they score high on one or both ethnic variables but are comparatively equal in terms of the distribution of income. Social security spending—an essential political institutional characteristic—is highest in Europe; moderate public protection expenditures between 5 and 15 % exist in the Americas but they are very low throughout Africa and Southeast Asia with spending levels well below the 5 % margin. A different picture emerges when we look at land inequality. Here Latin America and former Soviet countries are consistently more unequal than most African countries with the exception of South Africa and again most of Western Europe. In conclusion, although several characteristics described above do co-occur in many countries, some of them also form different groups of constellations. Whereas most characteristics combine advantageously in Western Europe, Latin American countries are often characterized by high levels of historic ethnic exploitation, and more pronounced land inequality while African countries are more ethnically fractionalized but less prone to highly unequal land distributions.

Turning from concrete maps to the scatterplots of Fig. 2a–f, we can see that the positive correlations of historic (r = 0.56Footnote 4) and contemporary ethnic structures (r = 0.39) with income inequality are indeed present on a global scale. South Africa, Namibia and Zimbabwe are paradigmatic cases, where high levels of income inequality go hand in hand with a dire history of ethnic exploitation and a high degree of present-day ethnic fractionalization. In contrast, there is no clear association of income inequality with the degree of ethnic conflicts (Fig. 2c).

If we look at Fig. 2d–f, it becomes clear that structural factors like economic prosperity (GDP per capita) and land distribution as well as political-institutional factors are also related to the level of income inequality. In fact, these characteristics tend to cluster in many countries. The level of social security spending (Fig. 2d) measuring the strength of public welfare programs is strongly negatively correlated with income inequality (r = −0.60), i.e. the higher public spending, the lower income inequality. West and East European countries which enjoy a comparatively equal income distribution spend on average between 13 and 19 % of their gross domestic product on social protection, while average public spending amounts to only about 7 % in the Americas and Oceania, 3.7 % in Asia and 2 % in all of Africa. Economic prosperity (Fig. 2e) and land distribution (Fig. 2f) show u-shaped relations with inequality. Income inequality tends to be lower both in poor and in rich countries and in countries of equal and unequal land distribution; the correlations however, are not high and the patterns of co-distribution not very clear. There are many exceptions. Countries like Pakistan or Ethiopia represent economically poor and rather equal countries, while South Africa ranks among the wealthier nations but is highly unequal in terms of its income distribution. In case of land inequality and income inequality, the history of Communism seems to intervene with the result of less inequality. Most times when arable land is distributed highly unequal among the population, a highly unequal income distribution follows in a more or less linear fashion. In many post-Communist East European and Asian countries (e.g. Hungary, Czech Republic, Azerbaijan, Belarus or Kyrgyzstan) however, income distribution is still comparatively even in comparison to the rather unequal land distribution. In case of land inequality, the history of Communism (countries with such a past are shown as black starlets in Fig. 2f) makes it look like a curvilinear association with income inequality, while actually a linear relationship becomes apparent when we control for Communism (r = 0.48). Therefore, most times when arable land is distributed highly unequally among the population, income is distributed unequal as well.

5.2 Robust Regression Analysis

In order to give the reader a possibility to evaluate our findings as much as possible, we present in Table 3 the Pearson correlation coefficients between all variables entered into the regression analysis. Three results from this Table may be relevant here. In addition, two other measures of income inequality have been included, the proportion of total income-going to the population in the 40 % lower income deciles, and the proportion going to the highest 10 % income receivers.

The following findings from this Table may be relevant here. First, we can see that the three indicators for income inequality are correlated strongly (0.80 to 0.94) with each other, thus confirming the reliability of the GINI coefficient as a measure of income inequality. Second, we can observe rather strong associations between income inequality (GINI) and our central variables, ethnic fractionalization and historic ethnic exploitation. Third, it is obvious that income distribution is strongly associated with Social Spending, thus indicating the central role of politics in this regard. Fourth, there exist also quite substantial correlations between GDP per capita on one side and Ethnic Exploitation as well as two political variables (Democratic Tradition and Social Spending). This fact constitutes a certain problem for regression analysis; we will come back to it below.

Table 4 reports the findings of the multivariate linear regression analysis for 123 countries; it includes three different models. They have been established following our three basic theoretical frameworks and hypotheses developed before. In the basic model (I) only the variables related to the ethnic structure (ethnic fractionalization and conflict) are included controlling only for GDP per capita. Thus, this model tests Hypothesis 1 stating that in ethnic heterogeneous countries particularly the lower socioeconomic classes have more difficulty to organize themselves and to fight for their interests; as a consequence, economic inequality will be higher in such societies. Findings show that this is indeed the case. Strong ethnic fractionalization leads to higher economic inequality. Thus, the results support Hypothesis 1. However, there is no verifiable association between the degree of ethnic conflicts and income inequality which corresponds to the descriptive analysis shown in Fig. 2.

Does this result change if we introduce Historical Ethnic Exploitation; thus, the institutional perspective? Findings in Model II show that this additional variable has a strong and significant effect, leading toward higher income inequality. However, the effect of ethnic fractionalization does not disappear. What is remarkable, however, is that the effect of GDP per capita becomes significantly weaker in Model II. Thus, we can say that the association between level of socio-economic development and income inequality, as shown descriptively in Fig. 2e, to a considerable degree is only a spurious correlation. Latin American countries like Brazil, Mexico and Chile or the Republic of South Africa with a GPD p.c. of 5000 to 8000 US-Dollars do not have an extreme high level of inequality (GINI 46 to 49) because they are on an intermediate level of development but because they practiced slavery and the exploitative institutions of colonialism. This is proved by the fact that countries on similar levels of development, like Hungary and Poland, or Algeria and Lebanon, exhibit rather moderate levels of inequality (GINI 27–34).

In Model III we introduce also the effects of institutional-political variables, as formulated in Hypothesis 3. Here, we control also for land inequality which by several authors was considered as an important concomitant of the colonial made of production and exploitation. All these variables turn out to carry major explanatory power for today’s income inequality. Particularly inequality of land distribution exerts a significant and strong effect, reducing but not erasing fully that of Historic Ethnic Exploitation. Among the political factors, two stand out as particularly strong determinants of income distribution. The one is a country’s State Socialist past or present which is clearly associated with its level of income inequality (b = −0.31). On the average the Gini-coefficient in Communist countries is about 7 points lower than in countries lacking experience with such a system. The level of Social Spending also shows a clear pattern (b = −0.32), as every additional percentage point of the GDP spent on social security lowers the Gini-coefficient significantly by 0.09 points. In short, an experience of Communism and extensive social spending are highly important for a country to be equal in terms of the distribution of incomes. Furthermore, a country’s federalist constitution slightly reduces inequality (b = −0.10). In contrast to that, there is no verifiable effect from democracy, which means that in democratic countries income inequality need not necessarily be lower than in autocratic countries. Two explanations can be given for this result. First, it can be due to the fact that the impact of democracy is captured by other variables, such as the strength of the welfare state; in part, it could also be a consequence of our method of reducing this dimension to a dichotomous variable. However, a look at the industrial countries shows several inconsistent cases in the relation democracy-inequality (e.g. the democratic USA with a rather high level of inequality; long lasting authoritarian regimes but high economic equality). A second explanation of the weak association between democracy and inequality can be that the distribution of income is a very long-term phenomenon, “the result of cumulative actions for centuries or longer” (Rodrik and Subramanian 2003: 33) which cannot easily be changed by shorter-term shifts in political systems and policies. Thus our Hypothesis 3 relating to the effects of the political system and institutions has been supported fully.

When controlling for characteristics of the political system, the effect of ethnic fractionalization disappears, whereas a country’s history of ethnic exploitation retains its significant predictive value though it is reduced from 0.23 to 0.15. In other words, the amount of social spending—the welfare state—and redistribution of land seem to be able to cancel out the inequality-producing affect of ethnic fractionalization and also reduce significantly the impact of a history of ethnic exploitation on today’s inequality. Nevertheless they cannot totally eliminate the deep imprint on society of a history of slavery and Apartheid.

Thus, Hypothesis 2 about the relevance of a country’s history of ethnic exploitation is supported by empirical evidence, even after controlling for the political variables.

6 Summary and Outlook

The aim of our paper was to explain economic inequality within the present-day nation states. This topic has received less attention than that of global inequality, that is, differences between states in spite of the fact that global inequality has been decreasing in recent decades while intra-national inequality is increasing in many states around the world.

Our descriptive analysis first of all showed extreme differences between the countries and macro-regions of the world in regard to intra-national economic inequality. Particularly Europe exhibits a low level of income inequality, in contrast to Latin-America and Sub-Saharan Africa where incomes are distributed in a highly unequal manner. African countries show a lower average level of income inequality than Latin America but a larger variation between the countries. Particularly all countries in Southern Africa exhibit extremely high levels of economic inequality. Most Asian countries can be considered as fairly equal in global comparison, although there are also several highly unequal cases. Further, it is evident that in Latin America high levels of historic ethnic exploitation, less distinct ethnic fractionalization but more pronounced land inequality go hand in hand, while African countries are more ethnically fractionalized but less prone to highly unequal land distributions. In contrast all these characteristics combine advantageously in Western European countries. Overall, no distinct and one-dimensional pattern could be identified. The distribution of land is also highly unequal in post-socialist countries where income inequality is low; the amount of social spending is lowest in highly unequal Africa but also in South-East Asia, a region of rather low income inequality in global comparison. Thus, from our descriptive analysis it becomes obvious that several characteristics do co-occur in many countries; however they also form different groups of constellations.

The results of our robust regression analysis for 123 countries indicate that ethnic fractionalization and a history of ethnic exploitation were and still are significant forces in the production of economic inequality as proposed in Hypotheses 1 and 2. In terms of a country’s economic development the data seem to be consistent with the Kuznets’ thesis that the association between GDP and Gini exhibits an inverted U-curve. However, although economic development might reduce the effect of ethnic fractionalization, the effect of historic ethnic exploitation (slavery) does not disappear. In Hypothesis 3 we took into account political system factors which could reduce inequality and lead toward more equality. In this regard, three characteristics of political institutions have emerged as being crucial. The system of Communism, welfare state redistribution, and a federal constitution. As expected, a history of Communism is associated with lower income inequalities today. The same is true for social spending; also a well-developed welfare state is able to cancel out the effect of ethnic heterogeneity and also to diminish the effect of a history of ethnoclass exploitation on income inequality within a country.

We think that our findings imply some significant consequences for research on international inequality differences within countries. First, it is evident that neither a class theory nor a theory of ethnic differentiation and conflict alone are able to explain the huge international differences in intra-nation inequality. This can be achieved only by a theory which focuses on the intersection between these two processes. Second, a comprehensive social theory of economic inequality must come up with the fact that different causal mechanisms lead to equality and/or to inequality in different countries and macro-regions of the world. This thesis corresponds to the fact that—contrary to widespread assertions—there is no general increase of inequality around the world. From this perspective it becomes evident why very general theories of changes of income distribution must fail. Third, it is evident that specific historical-institutional factors (like land distribution or slavery) have repercussions till today; thus, also theories of inequality based on class and ethnic differentiations must be grounded historically.