Abstract

Although numerous studies have demonstrated that social support affects a range of life experiences, only a few have examined the moderators and mediators such as self-esteem. According to self-control theory, self-control represents one’s ability to override or change one’s inner responses, and to interrupt undesired behavioral tendencies and refrain from acting on them. A high level of self-control may help individuals to mediate or moderate negative affect and thus weaken any adverse effects, contributing to their subjective well-being (SWB) in the long run. The current study explored how this interaction may affect the subjective well-being of the Chinese elderly, for whom self-control and social support are especially important life management issues. The study examined whether self-control mediates and moderates the relationship between social support and SWB among the elderly Chinese population. The data were collected from 335 elderly Chinese people (162 females and 173 males) from ten cities in central China, who completed the Chinese Social Support Scale, Trait Self-control Scale, Life Satisfaction Scale and Positive and Negative Affect Scale. The results showed that self-control, social support and SWB were strongly and significantly related. Hierarchical regression analysis showed that self-control partially mediated the influence of social support on SWB. Moreover, self-control moderated the relationship between social support and positive affect, but not life satisfaction and negative affect. These findings imply that self-control is a critical indicator of SWB and can serve as a basis for differentiating between intervention strategies that promote SWB among the elderly by helping them manage positive and negative affect. Future studies should further examine the internal mechanisms by which self-control influences SWB.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

1.1 Subjective Well-Being

Subjective well-being (SWB) is a popular issue in the domain of positive psychology. It reflects individuals’ cognitive judgments of life satisfaction (LS) and affective evaluations characterized by positive affect (PA) and negative affect (NA) (Diener 1984). Studies have shown that many demographic variables such as age, gender and education may be related to SWB. Shmotkin’s (1990) review of SWB studies suggested that its cognitive aspect, or LS, was positively correlated, and that PA and NA were negatively correlated with age. Gender differences in SWB are usually small (Shmotkin 1990). One 30-year study of older Americans’ SWB found that age and sex had no consistent independent relationship with well-being (Larson 1978). Using cross-sectional (N = 516) and longitudinal (N = 203) samples, Kunzmann et al. (2000) concluded that although age per se was not a cause of decline in subjective well-being, health constraints were. In a study using a cross-sectional design involving over 1000 participants, Horley and Lavery (1995) found a positive association between SWB and age. However, given that one longitudinal study found less stability in SWB and age, the authors suggested that the relationship between SWB and age was equivocal. Studies have shown that education is positively correlated with SWB, i.e., higher levels of education usually predict higher levels of SWB. For example, Pinquart and Sörensen (2000) found that although education was positively associated with SWB, income was more strongly correlated with well-being than education. All things considered, it may be necessary when conducting a formal analysis to control age and gender discreetly and to take education into account. Moreover, research has demonstrated that high SWB signifies various positive outcomes such as larger social rewards (Park 2004) and superior work outcomes (Wright and Cropanzano 2000). As a result, the pursuit of well-being is an important goal for people. Lyubomirsky et al. (2005) concluded that the factors influencing an individual’s level of lasting happiness could be divided into three categories: a genetically determined set point for happiness, happiness-relevant circumstantial factors and happiness-relevant activities and practices. This observation frames the theoretical structure of the current study.

1.2 Social Support

This study does not discuss a genetically determined set point, but focuses instead on the circumstantial, activity-based and practice-based factors that influence lasting happiness. Among the circumstantial factors that influence subjective well-being, social support has received widespread attention, resulting in considerable research (Siedlecki et al. 2013). According to Cobb (1976), social support is information leading a person to believe he or she is cared for and loved, esteemed and a member of a network of mutual obligations. Social support encompasses a multitude of social interactions between friends, family members, neighbors and others (Barrera et al. 1981; Sarason et al. 1987). It is a very complex construct comprising many facets such as informative, instrumental and emotional social support (Cohen and Wills 1985) in addition to integrated (or embedded), enacted and perceived support (Barrera 1986).

Since the concept of social support was first proposed in the literature, the classification of subjective social support and objective social support has largely been recognized. Some widely used measurement tools reflect the objective versus subjective classifications of social support. For example, Henderson et al. (1980) argued that the measurement of social interaction should be constructed to inclusively assess the availability and perceived adequacy of a number of social relationship facets. Sarason et al. (1983, 1987) described a measure of social support (the Social Support Questionnaire, or SSQ) that included (a) the perceived number of social supports (objective aspect) and (b) the level of satisfaction with the social support available (subjective aspect). Andrews et al. (1978) established the practical SSQ, which included three dimensions of crisis support: the neighbor, relationship and group involved. Sherbourne and Stewart (1991) described four functional social support scales: emotional/informational, tangible, affectionate and positive social interaction. Reflecting on these studies, Xiao (1994) proposed it important to practically assess objective and subjective social support and established a new scale to measure its use: the Chinese Version Social Support Rating Scale (C-SSRS).

Numerous studies have provided evidence of the significant relationship between social support and SWB (Lu and Hsu 2013; McDonough et al. 2014; Sheldon and Hoon 2007). This relationship has been demonstrated to persist even when control variables such as personality (Diener and Seligman 2002), intelligence (Gallagher and Vella-Brodrick 2008) and many background variables (Landau and Litwin 2001) are taken into account. The relationship between social support and SWB has also been shown to persist regardless of whether the participants are young Chinese college students (Chou 1999); young college students in Iran, Jordan or the United States (Brannan et al. 2013); or older adults (Ferguson and Goodwin 2010). Siedlecki et al. (2013) found enacted and perceived supports to be significant predictors of LS, perceived support to predict NA and family embeddedness to have a particularly unique relationship with PA. Their large sample size, comprising 1,111 individuals between the ages of 18 and 95, further confirmed this relationship.

Of the three types of factors that influence an individual’s lasting happiness, intentional activity, which is over and above circumstances such as social support, is arguably the most promising means of altering an individual’s level of happiness. Intentional activity involves discrete actions or practices that people can choose to perform and also take some degree of effort to enact. It is obvious that individuals’ abilities to act intentionally to increase their levels of lasting happiness ultimately depend on their levels of self-control.

1.3 Self-Control

Self-control refers to the process by which individuals consciously decide to take charge of their own behavior and specifically focus on their efforts to change their responses to external events, as opposed to try to change external reality (Rosenbaum 1993, p. 33). This makes sense considering that a meta-analysis involving 9 literature search strategies and 137 distinct personality variables found personality to be an important predictor of SWB (DeNeve and Cooper 1998). The results demonstrated that a number of the traits most closely associated with SWB (e.g., repressive-defensiveness, locus of control-chance, desire for control hardiness) also embodied trait self-control (TSC) to a certain extent. Self-control provides the “human organism” with “the capacity…to override, interrupt, and otherwise alter its own responses,” which Muraven et al. (1998) described as “one of the most dramatic and impressive functions of human selfhood, with broad implications for a wide range of behavior patterns” (p. 774). Not surprisingly, Hofmann et al. (2013) found higher TSC to be related to higher SWB. TSC was also positively correlated with LS and PA and negatively correlated with NA. Rosenbaum (1993) aligned self-control with an individual’s ability to choose and enact. Ross and Van Willigen (1997) showed that by choosing to become educated, individuals were able to decrease their distress, largely by way of paid work and economic resources associated with a high sense of personal control. Thus, self-control has been established as one of the most important factors influencing happiness-relevant activities and practices.

Despite the widespread attention given to self-control, few studies have explored the relationship between self-control and SWB among the elderly. Furthermore, although a great deal of effort has been devoted to exploring the interaction of happiness-related activities and happiness-related circumstances, a more complex picture of the relationship between social support, self-control and SWB has yet to be clearly drawn. A few studies have established a theoretical framework for the ways in which self-control mediates and moderates the influence of social support on SWB. Daniels and Guppy (1994) determined how social support and job control affected participants’ levels of occupational stress and found that individual well-being improved when the participants had perceived job control. Individuals’ experiences of an internal locus of control and job control synergistically buffer the effects of stressors upon their well-being. According to Thoits (1986), without powerful social support, a situation that threatens an individual’s survival or self-regard intensifies his or her anxiety, sadness or despair to such a degree that it can undermine the individual’s sense of self-control and subsequent problem-solving ability. Moreover, higher levels of self-control have been found to mitigate possible adverse effects on aggression in adolescents (Hamama and Ronen-Shenhav 2012). One longitudinal study found that low self-control in childhood predicted disrupted social bonds and criminal behavior enacted later in life. The study also found that “the effect of self-control on crime was largely mediated by social bonds” (Wright et al. 1999, p. 479). Accordingly, self-control may mediate the effect of social support on SWB among older individuals.

Self-control has also been found to act as a moderator for a more positive attitude toward life (Sinha et al. 2002), decreasing the number of social support variables that explain SWB (Zhang and Xing 2007). As an individual’s self-control increases, his or her rate of depression decreases and he or she requires less social support to achieve SWB. Meanwhile, those with lower levels of self-control experience the opposite (Zhang and Xing 2007). Wilcox and Stephen (2013) reported that online social networks enhanced the self-esteem of users who focused on close friends (i.e., those with whom they had strong ties). However, this increase in self-esteem also decreased their self-control. Accordingly, in this study, we expected self-control to moderate the effect of social support (which is at least partially reflected by an individual’s social network) on SWB.

In short, by accounting for the interaction between social support, which reflects people’s status circumstances, and self-control, which reflects the ways in which people choose to respond to their circumstances, we strive to depict a more complex picture of how individual and lasting well-being is both actively and passively affected and attained. The members of our focus population, i.e., the elderly, are not as self-sufficient as they were in their younger years. As they frequently experience the deaths of friends and loved ones, they become more socially isolated than the young (López Ulloa et al. 2013). As a result, social support and self-control may be more important for the elderly and the strength of their interaction may be stronger, particularly because advancing age may compromise not only their physical but also their mental capabilities. At this point, self-control, which is one of the most important factors among happiness-relevant activities and practices, and social support, which is one of the most important factors among happiness-relevant circumstances, become vitally important for improving the SWB of the elderly.

The main goals of the current study were to examine whether self-control plays a moderating and mediating role in the relationship between social support and SWB (LS and PA/NA) among a sample of elderly Chinese people. Based on earlier literature, we tested the following hypotheses: (a) social support is a significant predictor of SWB, and self-control has a significant effect on SWB; (b) self-control mediates the relationship between social support and SWB; and (c) self-control moderates the influence of social support on SWB. We were interested in observing differences in individuals’ SWB when they had the same degree of social support but different self-control characteristics. We were especially curious to discover whether a high level of self-control would magnify the positive effect of social support on SWB and whether a low level of self-control would diminish the positive effect or even lead to a totally negative effect. In general, we expected self-control to play a role in the relationship between social support and SWB. We expected the interaction between social support and self-control to provide an alternative explanation for why SWB does not increase among older people when they receive social support without considering other interactive factors. Should self-control prove to be a critical mediator and moderator of SWB, the results may serve as a basis for interventions that enhance the SWB of elderly Chinese people.

2 Methods

2.1 Participants

The participants consisted of 335 older Chinese people from 10 cities in central China, including Hunan and other provinces. These cities were a convenience sample that resulted from researchers being introduced to MBA and EMBA students in each city. There were approximately 20–50 participants in each city. The participants consisted of 162 women and 173 men. Their ages varied from 55 (the age of retirement for Chinese women) to 93, with an average age of 70.355 (SD = 7.353). They were all retiredFootnote 1 and had worked as civil servants and staff members of public business organizations before retirement. Only 1.5 % (n = 5) of the participants were identified as having higher than a university level education, 18.8 % (n = 63) were identified as having below a primary school education, 34.6 % (n = 116) were identified as having a junior high or middle school education and 45.1 % (n = 151) were identified as having almost a high school education. Furthermore, 0.6 % (n = 2) of the sample participants were single, 86.6 % (n = 290) were married to a living spouse and 11.0 % (n = 37) were divorced or their spouse had passed away. Six participants (1.8 %) did not answer the question.

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 Social Support

Xiao (1994) developed the Chinese Social Support Rating Scale (C-SSRS) based on China’s unique cultural background. The scale includes 10 items that evaluate three dimensions: subjective social support, objective social support and the utilization of social support. The following is a sample item used in the current study: “I receive support and care from family members (couples/lovers, parents, children, brothers and sisters, other family members).” The participants responded on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“not at all”) to 4 (“very much”) with the exception of items 6 and 7, for which they selected one source of social support (which counted as one score). We added up the C-SSRS scores. Higher mean total scores implied more perceived social support, objective social support and better use of social support. Xiao (1994) showed that the test–retest α coefficient of C-SSRS was 0.92 at an interval of 2 months and a significantly negative predictor of SCL-90. The C-SSRS has been proven to cumulatively explain 55.84 % of variance. According to exploratory factor analysis (EFA) results among 268 community residents, Cronbach’s α coefficient for the C-SSRS was 0.69 and that for all three sub-dimensions was above 0.83. The correlations of dimension-scale and dimensions–dimensions were distributed from 0.72 to 0.84 and from 0.45 to 0.66, respectively (Liu et al. 2008). The confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) results demonstrated a good fit for the scale among 943 college students: RMSEA = 0.06, NFI = 0.93, NNFI = 0.93, CFI = 0.92, GFI = 0.92 (Tu and Guo 2011). In the current study, Cronbach’s α coefficient for the C-SSRS was almost 0.72.

2.2.2 Self-Control

We adapted the Chinese Self-Control Scale (C-SCS) for cultural conditions in China from an English-language version developed by Tangney, Baumeister and Boone (2004). The scale consists of 5 dimensions and 19 items designed to assess impulse control (6 items), healthy habits (3 items), temptation avoidance (4 items), work concentration (3 items) and entertainment-harming resistance (3 items). The following sample item was included in the current study: “I am good at resisting temptation.” Each item was scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“not at all like me”) to 5 (“very much like me”). Tan and Guo (2008) identified five dimensions of self-control that cumulatively explained 53.70 % of the variance via EFA among 280 college students. Cronbach’s α coefficient for the C-SCS was 0.86, and that for all five of the sub-dimensions was above 0.60. The test–retest α coefficient of C-SCS was 0.85 at an interval of 1 month, and the item-scale correlation was distributed from 0.33 to 0.56. CFA results demonstrated a good fit for the scale among 240 college students: RMSEA = 0.05, GFI = 0.91, IFI = 0.93, NNFI = 0.91, and CFI = 0.93. Moreover, the correlations between the C-SCS and Life Satisfaction Scale and between the C-SCS and General Health Questionnaire were significant at 0.16 and 0.32, respectively (Tan and Guo 2008). In the current study, a mean total score was calculated for the total scale (Cronbach’s α = 0.756), with higher scores implying better self-control.

2.2.3 Subjective Well-Being

Self-rated LS was assessed according to four items based on the following statement taken from the Satisfaction with Life Scale developed by Diener, Emmons, Larsen and Griffin (1985): “I am satisfied with my life.” In the current study, the participants responded to three of the items on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“not at all”) to 5 (“extremely”). These three items indicated domain satisfaction with mental health, physical health and relationships. The following sample item was included: “To what extent do you feel satisfied with your mental health/physical health/relationship situation?” Cronbach’s α coefficient for the three items was equal to 0.742. The participants also responded to the following item using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (“not at all”) to 5 (“very”): “In all, to what extent do you feel satisfied with your life?” This item indicated a general/global level of satisfaction and was used to measure general LS. A grand averageFootnote 2 was calculated from the mean score of the three items and the mean score of the fourth item, with higher scores implying that the participants felt happier and more satisfied. Cronbach’s α coefficient for the two items was equal to 0.535.

We measured the PA and NA of SWB using a Chinese Version (Huang and Yang 2003) of the Positive Affect and Negative Affect Scale (PANAS; Watson et al. 1988). The PANAS consists of 20 descriptive words, 10 of which assess PA (e.g., “joyful”) and the rest of which assess NA (e.g., “sad”). The participants were instructed to indicate the extent to which they generally felt each affect word using a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (“not at all or very slightly”) to 5 (“extremely”). PA and NA were calculated separately, with higher scores implying that the participants felt more of that affect. The two-factor dimensionality of positive affect (PA) and negative affect (NA) was validated across 201 Chinese and 321 US college students by EFA, which accounted for 51.3 and 44.3 % of common variance. Furthermore, Chinese PA and NA subscales were verified to show a relatively high reliability of internal consistency compared with the English-language version among US college students (Zhang et al. 2004). Cronbach’s α coefficients for PA and NA were 0.85 and 0.83, respectively, and the test–retest α coefficient for PA was the same (equal to 0.47) as that for NA. All of the correlations between NA and SCL-90 were significant (equaling 0.65) among the 372 community residents (Huang and Yang 2003). We calculated two mean total scores for the two total scales (NA and PA). Cronbach’s α coefficients for the PA and NA scales were 0.710 and 0.705, respectively. PA showed no significant negative correlation with NA (r = −0.019, p > 0.05).

2.3 Procedure

All of the participants were contacted through the individuals in charge of the communities in each city. After giving their preliminary agreement to participate, they were administered a set of questionnaires in a meeting room used for community activities. The questionnaires took about 25 min to complete. The participants were not required to write their names or other personal information on the measures, and were assured of the confidentiality of their responses. Of the 400 questionnaires distributed, 335 valid questionnaires were returned after incomplete and missing questionnaires were excluded, representing a return rate of 83.75 %.

2.4 Data Analysis

First, we generated preliminary means, standard deviations and a correlation matrix to explore the associations between the variables. Second, we analyzed self-control as a mediator based on a four-step analysis model derived from Kinney (2006). We added the fifth step, the Sobel test (Sobel 1982), using the bootstrapping method suggested by Preacher and Hayes (2004). This bootstrapping method allowed us to test for the significance (or lack thereof) of an indirect effect. We tested three mediation models, each of which included social support as the predictor and self-control as the mediator. The dependent variables of the model included Positive Affect, Negative Affect, and Life Satisfaction. For each of the models, the five steps indicated mediation.

Finally, we tested the moderating effects of self-control on the relationship between social support and SWB. To do so, we executed hierarchical regression procedures as recommended by Baron and Kenny (1986). Before testing the moderating effects, we standardized the two predictor variables (social support and self-control) to decrease the problems associated with multicollinearity between an interaction term and the main effects (Frazier et al. 2004). We performed three hierarchical multiple regression analyses for each of the three dependent variables: Life Satisfaction, Positive Affect and Negative Affect. In each hierarchical regression model, the order of variables entry was as follows. At Step 1, the control variables (Age, Gender and Educational level) were entered into the regression equation. At Step 2, the predictor variable and the moderator variable (Social support and Self-control) were entered into the regression equation. At Step 3, the interaction of social support × self-control was added. A significant change in R 2, which was reflected by T coefficients of the interactional term, indicated a significant moderator effect.

3 Results

Social Support was significantly positively correlated with Life Satisfaction, Positive Affect, and Self-control, and significantly negatively correlated with Negative Affect. Self-control was significantly positively correlated with Life Satisfaction and Positive Affect, while significantly negatively correlated with Negative Affect (Table 1).

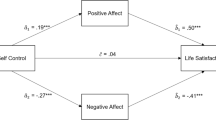

The data in Table 1 demonstrate the associations found during Steps 1 and 2 of mediation analysis. Table 2 presents Steps 3, 4, and 5 of mediation analysis, including the multivariate analysis results and the significant levels of the Sobel test. The results show that Self-control partially mediated the relationships between Social Support and each of the three sub-dimensions, Positive Affect, Negative Affect as well as Life Satisfaction (see Fig. 1). For each model, the Sobel test, which used the bootstrapping method, also indicated significant mediation without “0” included within the 95 % confidence intervals (Table 3).

In terms of the predictors of Life satisfaction, the results show that the main effects of Social support (β = 0.114, p < 0.05) and Self-control (β = 0.136, p < 0.05) were significant. However, the interaction between Social support and Self-control (β = 0.023, p > 0.05) was not significant. In terms of the predictors of Negative affect, Self-control (β = −0.331, p < 0.001) was significant and Social support (β = −0.071, p > 0.05) was not. Higher Self-control values indicated lower Negative affect values. However, the interaction effect between Social support and Self-control (β = 0.010, p > 0.05) was not significant.

The results demonstrate that Social support (β = 0.346, p < 0.001) and Self-control (β = 0.134, p < 0.01) significantly predicted Positive affect. Higher Self-control and Social support levels indicated higher Positive affect. The interaction effect between Social support and Self-control (β = 0.176, p < 0.001) was also strongly significant. The results imply that Self-control moderated the relationship between Social support and Positive affect. We provide a line chart consistent with the steps suggested by Aiken and West (1991) to show the interaction effect for Positive affect more intuitively. This line chart shows the regression of Positive affect on Social support at high (one standard deviation above the mean) and low (one standard deviation below the mean) levels of Self-control (see Fig. 2). As Fig. 2 shows, there was a significant positive relationship between Social support and Positive affect at a high level of Self-control (β = 0.781, p < 0.001) when the educational level condition was controlled. In contrast, the relationship between Social support and Positive affect was much weaker (β = 0.310, p < 0.001) at a low level of global Self-control when the educational level condition was controlled. The predictive effect of Social support on Positive affect was stronger among participants with high rather than low levels of Self-control.

4 Discussion

4.1 Self-Control as a Mediator and a Moderator

The findings of this study demonstrate the important role that self-control plays in the relationship between social support and SWB among a sample of elderly Chinese people, for whom self-control had a significant correlation with SWB and especially with NA. These results are in line with the previous finding of a significant relationship between self-control and SWB (De Ridder et al. 2012; Funder and Block 1989; Funder et al. 1983). Even when gender, age, educational level and social support were controlled for, we found self-control to be a very significant predictor (mediator and moderator) of the affective components of SWB. This result is partially consistent with earlier findings (Muraven et al. 1998).

There are several explanations for these results. The majority of elderly Chinese people have exited the labor market. This change in circumstance narrows their interpersonal circles and decreases their income to a fixed pension. However, this change enables the elderly to focus on a few new relationships and strengthen their current relationships. Because they are no longer the main providers for their families, they have more opportunities to spend time and relatively more money on activities that contribute to their SWB. They are also able to devote their attention selectively to positive things (López Ulloa et al. 2013). However, positive, selective attention and active participation may be considered prerequisite conditions for higher levels of self-control. As a result, self-control is a barometer of subjective well-being among the elderly, and a higher level of self-control effectively predicts a higher level of SWB.

The study’s most important result is its demonstration that self-control mediates the relationship between social support and SWB, especially in terms of NA and PA. The participants with high levels of social support were likely to engage in higher levels of self-control, which in turn increased their LS and PA and greatly decreased their NA. The results are consistent with a study conducted by Hofmann et al. (2013), who found a higher level of self-control to be related to a higher level of SWB, positively correlated with LS and PA and negatively correlated with NA. The authors also found self-control to have a robust and important role in SWB based on samples of participants drawn from different cultures and age groups. Furthermore, their study observed self-control to have the strongest mediating role in the relationship between social support and NA. Self-control theory accounts for this result (Karoly 1995). In self-control theory, self-control is identified as the ability to override or change one’s inner responses (such as NA) and interrupt undesired behavioral tendencies (such as impulses) and refrain from acting on them. Self-control helps to control one’s NA and weakens any adverse effects, thereby contributing to proper behavior in the long run and indirectly enhancing the individual’s LS.

However, the mediating effect of self-control on the relationship between social support and LS (see Table 2) should be interpreted with considerable caution. In this study, although zero is included in the 95 % confidence interval and the indirect effect was indeed significantly different from zero at p < 0.05 (two tailed), the absolute value of the mediated effect was very small (equal to 0.002), indicating that the mediating role of self-control in the relationship between social support and LS was extremely weak. This might have been caused by the survey method we used. It is impossible to control every variable using the survey method in one investigation, especially those variables that affect the relationship between social support and self-control. A few studies have demonstrated that several factors may affect the relationship between social support and self-control, such as self-esteem (Wilcox and Stephen 2013) and self-efficacy (Gao et al. 2013). The intertwined relationship between social support and self-control provides another explanation. For the elderly, a lower level of self-control may stem from a higher level of social support from family members, and a higher level of self-control may hinder social support from family members. As a result, despite the very different relationships between social support and self-control, their influence on LS may remain very weak.

In this study, self-control surprisingly moderated the influence of social support on PA but not on NA or LS. When the elderly Chinese participants reported a higher level of self-control, those who also indicated a high level of social support reported higher PA scores than those with a low level of social support. However, the groups with high and low levels of social support exhibited no differences in LS when they were confronted with either low or high levels of self-control. This surprising finding is probably related to the characteristics of the elderly Chinese population’s living environment. In a collectivist cultural context, personal relationships have been found to be less voluntary and support is likely to be sought more cautiously (Kim et al. 2006). Social support from family members has been shown to contribute more to LS among the elderly Chinese than other kinds of support (Chou and Chi 1999; Yeung and Fung 2007). However, family support often declines as one’s wealth increases. Families in which three or even four generations used to live together have quickly broken up. Family members are usually scattered across the country and even the world. Hence, elderly people who experience frequent or long-term NA do not always receive the careful responses from family members they might have once received. In such a circumstance, self-control plays a unique regulatory role in supporting the ability of elderly people to cope with life events and emotional problems. However, for those elderly Chinese people with the lower and lowest levels of self-control, simple social support from family members may easily turn into psychological and physical dependence. This can further decrease elderly individuals’ levels of self-control and further increase their levels of NA, which may in turn damage their SWB.

The results demonstrate that although increasing self-control magnifies the positive effect of social support on PA, it cannot significantly weaken the negative effect of social support on NA. This may reflect an interaction between the nature of affect and the content of self-control. Although it is clearly unnecessary for people to resist PA, it is necessary for them to regulate NA. However, the C-SCS used in the study was not specifically designed to assess the ways in which individuals attempt to regulate or cope with their NA, but to assess impulse control (Tangney et al. 2004). Furthermore, literature has had relatively little to say about impulse control among the elderly and has instead focused more on impulse control among young children (Sagiv et al. 2012; Sharkey et al. 2012). Impulse control may be more closely related to behavior and less connected to emotion. Future studies that measure self-control according to indicators of emotion regulation such as the Negative Mood Regulation Expectancies Scale (Catanzaro and Mearns 1990; Mearns et al. 2013) or Self-Regulation of Withholding Negative Emotions Scale (Kim et al. 2002) may find that increasing self-control greatly weakens the negative effect of social support on NA, i.e., that emotional self-control significantly moderates the negative effect of social support on NA. Finally, our results may imply that different personality variables influence the cognitive (LS) and affective (NA, PA) evaluation factors of SWB to varying degrees.

4.2 Implications

This study may reinforce the crucial roles that social support and self-control play in strategies developed to promote SWB among the elderly. However, it remains unclear how those working with the elderly may promote PA and lessen NA. Improving self-control can magnify the contribution that social support makes to PA, an effect that researchers sometimes refer to as the “icing on the cake.” However, improved self-control does not significantly weaken the potential of social support to decrease NA. Thus, although it may be practically useful to enhance the elderly’s PA by promoting their self-control, regardless of whether they have low or high levels of social support, improved self-control will not alleviate their NA. We could also provide the elderly with affect-regulation training (Cloitre et al. 2002; Wadlinger and Isaacowitz 2011), especially in terms of how they regulate NA (Aldao et al. 2010; Koole et al. 2011) as they negotiate between social support and self-control in attempting to achieve SWB.

4.3 Limitations

The study has several limitations that should be addressed. First, although it demonstrates the mediating and moderating effects of self-control, other mediators and moderators must be identified and tested. For example, Mui (1999) found that elderly Chinese Americans who lived alone and were dissatisfied with the help they received from family members were more likely to be depressed. The selection and optimization of life management strategies moderates the link between financial strain and LS (Chou and Chi 2002). Second, because the study adopted a cross-sectional design, it was difficult to make cause-effect inferences. Therefore, our results must be tested further via longitudinal or experimental studies. Third, we collected our data using the self-report method, which might have threatened the study’s internal validity. In future studies, using multiple methods for assessment (e.g., couples report) and a handgrip procedure (e.g., a handgrip measure for self-control) (Muraven et al. 1998, 1999) should contribute greatly to the validity of the research.

This study highlights the importance of self-control among the elderly. It finds that self-control significantly mediates and moderates the relationship between social support and SWB (especially for NA) among the elderly Chinese population. Considering the probable mechanisms identified by this study, we propose that those working with the Chinese elderly should design psychological interventions to promote their self-control ability. Future studies should continue to carefully examine the mechanisms and conditions that influence the effect of self-control on SWB among the elderly.

Notes

According to Chinese labor law, women can retire at age 55 and men can retire at age 60 only if they continued to work in the 10 years preceding their application for retirement. Most people “retire” before the official age of retirement under the current law for a number of reasons, including suffering a serious illness, becoming bored with their work, losing their position due to personnel system reform or caring for their grandchildren. Therefore, it may be more accurate to say that the majority of the elderly in China have exited the labor market.

There are two methods for giving weights. In the current study, the first method involved the four items having different weights. (The three items that represented the domain subject’s well-being were given a weight of 1, and the fourth item that represented the global subject’s well-being was given a weight of 3.) The other method involved the four items having the same weights. Clarifying this question would have simplified the complicated relationship between the global and domain subjects’ well-being. A few studies have shown both a close correlation and a substantial difference between global and domain subjects’ well-being, which the results obtained by reanalyzing the EFA data in the current study also support. Moreover, we reanalyzed the data giving all four of the items the same weights. The results demonstrated unchanged parameter significance and only rather weak changes in parameter values at the second and third place after the decimal point. Thus, choosing which weighting method to use appears to be a theoretical rather than methodological or statistical issue.

References

Aiken, L., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Aldao, A., Nolen-Hoeksema, S., & Schweizer, S. (2010). Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(2), 217–237.

Andrews, G., Tennant, C., Hewson, D. M., & Vaillant, G. E. (1978). Life event stress, social support, coping style, and risk of psychological impairment. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 166(5), 307–316.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator–mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51(6), 1173–1182.

Barrera, M. (1986). Distinctions between social support concepts, measures, and models. American Journal of Community Psychology, 14(4), 413–445.

Barrera, M., Sandler, I. N., & Ramsay, T. B. (1981). Preliminary development of a scale of social support: Studies on college students. American Journal of Community Psychology, 9(4), 435–447.

Brannan, D., Biswas-Diener, R., Mohr, C. D., Mortazavi, S., & Stein, N. (2013). Friends and family: A cross-cultural investigation of social support and subjective well-being among college students. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 8(1), 65–75.

Catanzaro, S. J., & Mearns, J. (1990). Measuring generalized expectancies for negative mood regulation: Initial scale development and implications. Journal of Personality Assessment, 54(3–4), 546–563.

Chou, K. L. (1999). Social support and subjective well-being among Hong Kong Chinese young adults. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 160(3), 319–331.

Chou, K. L., & Chi, I. (1999). Determinants of life satisfaction in Hong Kong Chinese elderly: A longitudinal study. Aging & Mental Health, 3(4), 328–335.

Chou, K. L., & Chi, I. (2002). Financial strain and life satisfaction in Hong Kong elderly Chinese: Moderating effect of life management strategies including selection, optimization, and compensation. Aging & Mental Health, 6(2), 172–177.

Cloitre, M., Koenen, K. C., Cohen, L. R., & Han, H. (2002). Skills training in affective and interpersonal regulation followed by exposure: A phase-based treatment for PTSD related to childhood abuse. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70(5), 1067–1074.

Cobb, S. (1976). Presidential address: Social support as a moderator of life stress. Psychosomatic Medicine, 38(5), 300–314.

Cohen, S., & Wills, T. A. (1985). Stress, social support and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98(2), 310–357.

Daniels, K., & Guppy, A. (1994). Occupational stress, social support, job control, and psychological well-being. Human Relations, 47(12), 1523–1544.

De Ridder, D., Lensvelt-Mulders, G., Finkenauer, C. F., Stok, M., & Baumeister, R. F. (2012). Taking stock of self-control: A meta-analysis of how trait self-control relates to a wide range of behaviors. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 16(1), 76–99.

DeNeve, K. M., & Cooper, H. (1998). The happy personality: A meta-analysis of 137 personality traits and subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 124(2), 197–229.

Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 95(3), 542–575.

Diener, E. D., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The Satisfaction with Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75.

Diener, E., & Seligman, M. E. (2002). Very happy people. Psychological Science, 13(1), 81–84.

Ferguson, S. J., & Goodwin, A. D. (2010). Optimism and well-being in older adults: The mediating role of social support and perceived control. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 71(1), 43–68.

Frazier, P. A., Tix, A. P., & Barron, K. E. (2004). Testing moderator and mediator effects in counseling psychology research. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 51(1), 115–134.

Funder, D. C., & Block, J. (1989). The role of ego-control, ego-resiliency, and IQ in delay of gratification in adolescence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(6), 1041–1050.

Funder, D. C., Block, J. H., & Block, J. (1983). Delay of gratification: Some longitudinal personality correlates. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 44(6), 1198–1213.

Gallagher, E. N., & Vella-Brodrick, D. A. (2008). Social support and emotional intelligence as predictors of subjective well-being. Personality and Individual Differences, 44(7), 1551–1561.

Gao, J., Wang, J., Zheng, P., Haardörfer, R., Kegler, M. C., Zhu, Y., & Fu, H. (2013). Effects of self-care, self-efficacy, social support on glycemic control in adults with type 2 diabetes. BMC Family Practice, 14(1), 66.

Hamama, L., & Ronen-Shenhav, A. (2012). Self-control, social support, and aggression among adolescents in divorced and two-parent families. Children and Youth Services Review, 34(5), 1042–1049.

Henderson, S., Duncan-Jones, P., Byrne, D. G., & Scott, R. (1980). Measuring social relationships the interview schedule for social interaction. Psychological Medicine, 10(4), 723–734.

Hofmann, W., Luhmann, M., Fisher, R. R., Vohs, K. D., & Baumeister, R. F. (2013). Yes, but are they happy? Effects of trait self-control on affective well-being and life satisfaction. Journal of Personality, 82(4), 265–277.

Horley, J., & Lavery, J. J. (1995). Subjective well-being and age. Social Indicators Research, 34(2), 275–282.

Huang, L., & Yang, T. Z. (2003). Applicability of the Positive and Negative Affect Scale in Chinese. Chinese Mental Health Journal, 17(1), 54–56.

Karoly, P. (1995). Self-control theory. In W. T. O’Donohue & L. E. Krasner (Eds.), Theories of behavior therapy: Exploring behavior change (pp. 259–285). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Kim, Y., Deci, E. L., & Zuckerman, M. (2002). The development of the self-regulation of withholding negative emotions questionnaire. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 62(2), 316–336.

Kim, H. S., Sherman, D. K., Ko, D., & Taylor, S. E. (2006). Pursuit of comfort and pursuit of harmony: Culture, relationships, and social support seeking. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 32(12), 1595–1607.

Kinney, D. A. (2006). Mediation. Retrieved October 21, 2013 from http://www.davidakenny.net/cm/mediate.htm.

Koole, S. L., van Dillen, L. F., & Sheppes, G. (2011). The self-regulation of emotion. In K. Vohs & R. Baumeister (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation: Research, theory, and applications (pp. 22–40). New York: Guilford Press.

Kunzmann, U., Little, T. D., & Smith, J. (2000). Is age-related stability of subjective well-being a paradox? Cross-sectional and longitudinal evidence from the Berlin Aging Study. Psychology and Aging, 15(3), 511–526.

Landau, R., & Litwin, H. (2001). Subjective well-being among the old–old: The role of health, personality and social support. International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 52(4), 265–280.

Larson, R. (1978). Thirty years of research on the subjective well-being of older Americans. Journal of Gerontology, 33(1), 109–125.

Liu, J. W., Li, F. Y., & Lian, Y. L. (2008). Investigation of reliability and validity of the social support scale. Journal of Xinjiang Medical University, 31(1), 1–3.

López Ulloa, B. F., Møller, V., & Sousa-Poza, A. (2013). How does subjective well-being evolve with age? A literature review. Journal of Population Ageing, 6(3), 227–246.

Lu, F. J., & Hsu, Y. (2013). Injured athletes’ rehabilitation beliefs and subjective well-being: The contribution of hope and social support. Journal of Athletic Training, 48(1), 92–98.

Lyubomirsky, S., Sheldon, K. M., & Schkade, D. (2005). Pursuing happiness: The architecture of sustainable change. Review of General Psychology, 9(2), 111–131.

McDonough, M. H., Sabiston, C. M., & Wrosch, C. (2014). Predicting changes in posttraumatic growth and subjective well-being among breast cancer survivors: The role of social support and stress. Psycho-Oncology, 23(1), 114–120.

Mearns, J., Park, J. H., & Catanzaro, S. J. (2013). Developing a Korean language measure of generalized expectancies for negative mood regulation. Journal of Asia Pacific Counseling, 3(1), 90–91.

Mui, A. C. (1999). Living alone and depression among older Chinese immigrants. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 30(3–4), 147–166.

Muraven, M., Baumeister, R. F., & Tice, D. M. (1999). Longitudinal improvement of self-regulation through practice: Building self-control strength through repeated exercise. Journal of Social Psychology, 139(4), 446–457.

Muraven, M., Tice, D. M., & Baumeister, R. F. (1998). Self-control as a limited resource: Regulatory depletion patterns. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(3), 774–789.

Park, N. (2004). The role of subjective well-being in positive youth development. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 591(1), 25–39.

Pinquart, M., & Sörensen, S. (2000). Influences of socioeconomic status, social network, and competence on subjective well-being in later life: A meta-analysis. Psychology and Aging, 15(2), 187–224.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2004). SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, 36(4), 717–731.

Rosenbaum, M. (1993). The three functions of self-control behavior: Redressive, reformative and experiential. Journal of Work and Stress, 7(1), 33–46.

Ross, C. E., & Van Willigen, M. (1997). Education and the subjective quality of life. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 38(3), 275–297.

Sagiv, S. K., Thurston, S. W., Bellinger, D. C., Altshul, L. M., & Korrick, S. A. (2012). Neuropsychological measures of attention and impulse control among 8-year-old children exposed prenatally to organochlorines. Environmental Health Perspectives, 120(6), 904–909.

Sarason, I. G., Levine, H. M., Basham, R. B., & Sarason, B. R. (1983). Assessing social support: The social support questionnaire. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 44(1), 127–139.

Sarason, I. G., Sarason, B. R., Shearin, E. N., & Pierce, G. R. (1987). A brief measure of social support: Practical and theoretical implications. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 4(4), 497–510.

Sharkey, P. T., Tirado-Strayer, N., Papachristos, A. V., & Raver, C. C. (2012). The effect of local violence on children’s attention and impulse control. American Journal of Public Health, 102(12), 2287–2293.

Sheldon, K. M., & Hoon, T. H. (2007). The multiple determination of well-being: Independent effects of positive traits, needs, goals, selves, social supports, and cultural contexts. Journal of Happiness Studies, 8(4), 565–592.

Sherbourne, C. D., & Stewart, A. L. (1991). The MOS social support survey. Social Science and Medicine, 32(6), 705–714.

Shmotkin, D. (1990). Subjective well-being as a function of age and gender: A multivariate look for differentiated trends. Social Indicators Research, 23(3), 201–230.

Siedlecki, K. L., Salthouse, T. A., Oishi, S., & Jeswani, S. (2013). The relationship between social support and subjective well-being across age. Social Indicators Research, 117(2), 561–576.

Sinha, S. P., Nayyar, P., & Sinha, S. P. (2002). Social support and self-control as variables in attitude toward life and perceived control among older people in India. The Journal of Social Psychology, 142(4), 527–540.

Sobel, M. E. (1982). Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. Sociological Methodology, 13(1982), 290–312.

Tan, S. H., & Guo, Y. Y. (2008). Revision of Self-control Scale for Chinese college students. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 16(5), 468–470.

Tangney, J. P., Baumeister, R. F., & Boone, A. L. (2004). High self-control predicts good adjustment, less pathology, better grades, and interpersonal success. Journal of Personality, 72(2), 271–324.

Thoits, P. A. (1986). Social support as coping assistance. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 54(4), 416–423.

Tu, Y. J., & Guo, Y. Y. (2011). The influence of life-events on negative emotions: Social support as a moderator and coping style as a mediator. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 19(5), 652–655.

Wadlinger, H. A., & Isaacowitz, D. M. (2011). Fixing our focus: Training attention to regulate emotion. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 15(1), 75–102.

Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 1063–1070.

Wilcox, K., & Stephen, A. T. (2013). Are close friends the enemy? Online social networks, self-esteem, and self-control. Journal of Consumer Research, 40(1), 90–103.

Wright, B. R. E., Caspi, A., Moffitt, T. E., & Silva, P. A. (1999). Low self-control, social bonds, and crime: Social causation, social selection, or both? Criminology, 37(3), 479–514.

Wright, T. A., & Cropanzano, R. (2000). Psychological well-being and job satisfaction as predictors of job performance. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5(1), 84–94.

Xiao, S. Y. (1994). Theoretical basis and research applications of Social Support Scale. Journal of Clinical Psychological Medicine, 4(2), 98–100.

Yeung, G. T., & Fung, H. H. (2007). Social support and life satisfaction among Hong Kong Chinese older adults: Family first? European Journal of Ageing, 4(4), 219–227.

Zhang, W. D., Diao, J., & Schick, C. J. (2004). The cross-cultural measurement of positive and negative affect examining the dimensionality of PANAS. Chinese Psychological Science, 27(1), 77–79.

Zhang, Y., & Xing, Z. J. (2007). A review on the research of the influence of social support on subjective well-being. Psychological Science, 30(6), 1436–1438.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by New Century Talent Supporting Project NCET-10-0370 by China Ministry of Education, Soft Science Major Project 2012ZK1003 in Hunan province, The Natural Science Foundation 13JJ3051 in Hunan province and The Social Science Foundation 12YBA065 in Hunan province. The authors would also like to thank the two anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful and stimulating comments on earlier versions of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tu, Y., Yang, Z. Self-Control as Mediator and Moderator of the Relationship Between Social Support and Subjective Well-Being Among the Chinese Elderly. Soc Indic Res 126, 813–828 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-0911-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-0911-z