Abstract

People’s ability to express their voice in different situation is an important facet of their quality of life. This study examines the relationship between social status, cultural characteristics and customers’ voice behavior in multiple cultures. We hypothesized that social status would be positively related to customers’ voice expression. The cultural dimensions of power distance and uncertainty avoidance were expected to affect that behavior and to moderate the status–voicing relationship. Analysis of data concerning 8,479 customers from 12 countries showed that, as expected, customers with high status tended to register more service failures and to complain more frequently than customers of lower social status. All three social status distinctions explored in this study (gender, education, and age) correlated negatively with formal complaint, but only age correlated negatively with informal complaint. In addition, the two cultural dimensions had the expected negative effect on intention to complain, and moderated the relationship between social status and intention to complain. Theoretical contributions and applied implications are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The world is becoming dominated by services, both public and private, that have a major impact on peoples’ quality of life. People depend on services provided by public or private organizations, in areas such as communication (phone, internet, postal), banking, utilities (electricity, gas, water, etc.), and transport (train, bus, subway).Many services are integral to people’s lifestyles, reflecting their specific needs and preferences (Gutek 1995). Examples include: professional services (e.g., health care, higher education, financial advice, and counseling), personal services (e.g., hairdressing) or pleasure and other services (e.g., leisure parks, hospitality, and commercial and retail services).

Accordingly, scholars acknowledge the importance of studying the links between service quality and quality-of-life or wellbeing, because the latter may depend on the processes and outcomes of services that people receive from both public and private providers (Njoh 1994; Ostrom et al. 2010). Dong-Jin and Sirgy (2004) suggested that “quality-of-life marketing” is a new paradigm, following previous paradigms such as relationship marketing. Dagger and Sweeney (2006) maintain that, while it is recognized that marketing is related to quality of life, it is service quality—the standard of service received (Parasuraman et al. 1988)—that has the strongest impact on quality of life. In a study of health services (Dagger and Sweeney 2006), service quality was indeed found to affect customers’ quality-of-life perceptions.

There is growing awareness of the need to ensure that services attain the desired level of quality (Abbate et al. 2001), and service researchers have emphasized the importance of the “service imperative”, i.e., a need to focus on service research and innovation across companies and institutions (Bitner and Brown 2008). Over the last two decades, governments and other stakeholders in the public and private sectors, as well as service providers, have shown increased interest in monitoring the quality of services, and have been seeking to develop indicators that can help in this regard (Morgeson and Petrescu 2011).

At the transnational level, we see evidence of growing interest in service-related indicators in various activities of the European Commission (EC). The EC directorate for Consumers has been developing an agenda focused on consumer empowerment (EC 2012), with scoreboards that help to monitor issues considered important for public policy, such as consumer trust, rights, satisfaction, and voiced expressions of complaints (see: http://ec.europa.eu/consumers). As part of the Eurobarometer survey system, the EC has also developed indices that reflect consumer empowerment and/or satisfaction with various types of services (e.g. EC 2011).

At the national level, governments and industrial associations have developed national indices that reflect consumer attitudes regarding service quality, such as the American Consumer Satisfaction index and the National Customer Satisfaction Barometer in Sweden (Johnson et al. 2001). Efforts to measure satisfaction with services provided by national or local governments are also evident (e.g., Vigoda-Gadot and Mizrahi 2008; Rhys and Van de Walle 2013). Many countries publish annual reports regarding complaints about various types of services, or statistics about the number of appeals to various ombudsman offices or Better Business Bureaus, in order to gauge whether the quality of services provided to the public is improving or not.

These efforts to develop indicators of consumer perceptions or complaints about services at the international or national level appear to be predicated on the assumption that the public has a right to receive good service. A decrease in levels of consumers trust or satisfaction, or an increase in the number of complaints received, are seen as reflecting problems about the efficiency, responsiveness, equity, professionalism, or effectiveness of service providers. Thus, reduced levels of trust or satisfaction, or an increase in complaints can be construed as reflecting on the public’s quality of life.

For indices to be useful, we need to understand what factors affect the public’s willingness to share perceptions or voice complaints regarding services. Rhys and Van de Walle (2013), for example, have analyzed data regarding perceptions of local governments in the UK, and have demonstrated the need to take into account the economic context and social background of respondents in order to understand changes and trends in how citizens perceive the performance of their municipalities. This study is an attempt to understand the influence of national culture and social groups within cultures on customers’ intentions to voice complaints or express dissatisfaction with services.

1.1 Consumer Voice

A major aspect of control over service quality is customers’ voicing of problems and dissatisfaction with service. While service failures are unavoidable, customers’ complaints often contribute to improvement of those services (Kasper et al. 1999; Liao 2007; Maxham and Netemeyer 2002) because they initiate a “service recovery” process (Liao 2007; Maxham and Netemeyer 2002). The link between the inclination to complain and customers’ quality of life is obvious with regard to services such as healthcare, social security, education, and many commercial services, where problems will not be known to the service provider, and rectified, without customers’ voicing their concerns. Complaining about problems encountered in public and commercial services often affects the quality of one’s life due to the many critical outcomes of such complaining behavior, which might be tangible (e.g., redress of the problem, compensation), intangible (e.g., apology, improved sense of justice) or both. Yet, many customers who encounter service problems do not voice their concerns at all, or choose to complain informally, which at times might be less effective than a formal complaint (Goodman 1999). The intention of present study is to understand the differences between customers who complain about service problems and those who do not complain, capturing both formal and informal complaints, and focusing on the effect of social status and cultural values.

Hirschman (1970) suggested that individuals who are dissatisfied with their relationship with an organization can either voice their dissatisfaction, i.e., try to improve the relationship through communicating a complaint or proposing a change; remain silent, i.e. continue the relationship without expressing dissatisfaction; or exit, i.e. withdraw their custom. The latter option is especially relevant in the highly competitive commercial services industry, where dissatisfied customers can easily terminate their relationship with a service provider and choose an available alternative. From the organization’s viewpoint, customer complaints are preferable to their remaining silent, not just because this can eventually lead to improved short-term profits (if service recovery does occur), but also because the analysis of customer complains can contribute to organizational learning and to long-term success (Buttle and Burton 2002; Homburg and Furst 2005; Luria et al. 2009; Schneider and Bowen 1995). The majority of dissatisfied customers, however, choose not to complain even when they believe they would be justified in doing so (Doron et al. 2011).

Our review of prior research on customer complaints shows that the literature so far has focused on the complaining behavior itself, overlooking information-processing aspects that are germane to complaints. The first purpose of the present study is thus to extend understanding of customer voice, as reflected in complaint behavior, by examining two factors that precede actual complaining, but are endemic to complaints, namely: recognition of service problems and intention to complain. We aim to understand whether social variables affect how customers evaluate service, and their intention to voice complaints rather than specific behaviors in reaction to specific failures.

Studies of service complaints have mostly explored individual-level variables (e.g. Voorhees et al. 2006), paying little attention to the wider social context. However, recent studies have demonstrated that voicing is contingent on cultural factors both at the national level (Botero and Van Dyne 2009) and at the level of social status within a national culture (Detert and Burris 2007; LePine and Van Dyne 1998; Miceli et al. 2008). Accordingly, the second purpose of this study is to explore the interactive effect of social status and national culture on these precursors of customers’ voiced complaints.

1.2 Social Status and Voice

Weber (1968) suggested that status is a major aspect of social inequality in contemporary society. In contrast to class, which reflects an array of life chances determined by the location of each individual within the market, status represents the outcome of communal social relationships that give rise to a social estimation of honor (Gane 2005; Weber 1968:932).Specifically, status disparities reflect hierarchical relationships between people (Fisek et al. 1991; Skvoretz and Fararo 1996), arising from a cultural belief that people belonging to one social group are more esteemed than those who belong to another group (Ridgeway and Erickson 2000; Webster and Foschi 1988). Individuals with higher social status are perceived by others and by themselves as having higher efficacy.

Weber (1968) originally illustrated the concept of status by discussing the formation and maintenance of residential and ethnic communities. Later formulations, addressing status inequalities in advanced western societies, identified gender, race, education, age, sexual orientation and physical attractiveness, among others, as important instances of status distinctions (Berger et al. 1980; Ridgeway and Correll 2006; Webster and Hysom 1998). At the core of these distinctions is a cultural perception of group differences in esteem and competence, maintained through behavioral differences that are expressed in interpersonal interactions (Ridgeway and Correll 2006). Such perceptions can induce higher status group members to higher levels of voice behavior than those from lower status groups. We focus on three consequential status distinctions, namely gender, education, and age, while controlling for class position.

Empirical findings support the hypothesis regarding the influence of social status on voicing. Differences in vocal expression have been found between men and women and between older and younger individuals (Gruber et al. 2009; Nardo et al. 2011; Suki 2014). Furthermore, individuals in the higher echelons of organizations are less likely to fear retaliation for “speaking up” (Miceli et al. 2008; Morrison and Rothman 2009) or being more outspoken (Fuller et al. 2006; Islam and Zyphur 2005; Stamper and Van Dyne 2001; Tangirala and Ramanujam 2008). Empirical support for the link between social status and voice in customer services has also been demonstrated in studies of customer sophistication, usually deriving from level of education. Thorelli (1971) suggested that sophisticated individuals complain more because they have more information, while Warland et al. (1975) found that customers from higher-education and occupation groups are more likely to take action when they are dissatisfied than customers of lower status. Andreasen (1985) also found that more sophisticated customers were more likely to recognize a service problem and react to it.

The above review suggests that there is a solid body of findings and supporting theoretical reasoning regarding the link between status and voicing, both in general and in service contexts. However, factors which precede actual complaints, such as intention to complain about a recognized service problem, have not been studied extensively. In line with the above reasoning and empirical findings, we posit our first hypothesis:

H1a

Individuals from higher status groups will report recognizing more service problems than individuals from lower status groups.

H1b

Individuals from higher status groups will report stronger intentions to voice complaints than individuals from lower status groups.

1.3 National Culture and Voice

Current understanding of cross-cultural differences in voice behavior is limited as most of the research to date was conducted in the United States. In contrast, research (e.g., Hofstede 1980) has demonstrated the strong impact of national culture on multiple other behaviors, such as norms about social roles and interpersonal communication (Burgoon et al. 1982; Dickson et al. 2000; Gelfand et al. 2007; Hirokawa and Miyahara 1986; House et al. 1999; Luria et al. 2014). Derived from these theories and findings, we focus in this study on two national cultural dimensions, i.e. power distance (PD) and uncertainty avoidance (UA), examining how these variables may influence identification of service problems and intentions to voice complaints.

1.3.1 Power Distance (PD)

Hofstede’s (1980) construct of Power Distance (PD) reflects the consequences of power inequality and authority relations in society. Soares et al. (2007) argue that PD influences social relationships and dependencies in family, organizational, and community hierarchies. In high PD societies, people accept the inequalities of treatment and rights in their society. Conversely, members of low PD cultures believe that such inequalities should be minimized (Hofstede 1980; House et al. 2002). Botero and Van Dyne (2009) suggested that PD has special relevance to voice behavior relating to perceptions of inequality of treatment, and found that PD negatively predicts voice in the workplace. Brockner et al. (2001) found that individuals from low PD cultures reacted more strongly than individuals from high PD cultures when they were not allowed to voice their opinions. Not having voice violates cultural norms in low PD cultures. Tyler et al. (2000) reported similar effects in regard to conflict resolution across cultures. With regard to the influence of PD on voicing in service contexts, and based on research indicating negative relationship between PD and perceptions of service quality (Ladhari et al. 2011), we expect that customers from low PD societies will recognize more service problems and be more inclined to complain because they tend to voice dissatisfaction according to their cultural norms. Thus:

H2a

Individuals from lower PD cultures will recognize more service problems than individuals from higher PD cultures.

H2b

Individuals from lower PD cultures will have stronger intentions to complain than individuals from higher PD cultures.

1.3.2 Uncertainty Avoidance (UA)

Individuals in high UA societies tend to rely on rules and procedures in order to increase their sense of predictability and reduce the threat of unknown situations (House et al. 2004; Triandis 1994). Voicing complaint increases uncertainty because it is interpreted as challenging the status quo and violating the standardized service process (Edmondson 1999; Van Dyne et al. 2003). Literature on factors that inhibit complaining (Fornell and Wernerfelt 1988; Goodman 1999) suggested that complaining is viewed by many customers as requiring a great deal of energy and involves uncertainty about the complaint process. In other words, complaining involves violation of customers’ routine behavior, and its outcomes increase uncertainty, so that the safest and thing to do is to refrain from complaining (Singh 1989; Tsai and Su 2009).This effect should be especially strong in cultures with a strong preference for avoiding uncertainty.

We therefore assume that customers in low UA cultures will be more likely to identify service problems and to report them.

H3a

Individuals from lower UA cultures will recognize more service problems than individuals from higher UA cultures.

H3b

Individuals from lower UA cultures are more likely to complain than individuals from higher UA cultures.

1.4 Social Status and National Culture

Because social status groups are nested within national cultures, the two coexist. Research has demonstrated that the effect of social status on evaluation of self- and others’ efficacy depends on the context in which interpersonal communication occurs (Ridgeway and Correll 2006). It is therefore important to explore the possibility that culture plays a moderating role in the effects of status on voice.

The effect of status on behavior depends on the degree of legitimacy granted to unequal distribution of power (Ridgeway 2006). Legitimacy is closely related to PD because countries with higher levels of PD show greater tolerance for unequal distribution of power (Hofstede 1980; House et al. 2002). Power differentials are inherent in customer–organization relationships as customers encountering service problems often have to depend on the service organization’s goodwill to improve service, correct mistakes, or provide compensation. However, individuals in high PD countries may be more willing to accept the superiority of the service organization and thus disregard problems or refrain from complaining. We therefore expect that social status will be more related to customers’ voice in a low PD country than in a high PD country.

The prediction regarding the moderating effect of UA is based on the effect of complaining on the customer’s relationship with the service provider. While individuals in high UA cultures prefer a high level of predictability of future events, a complaint increases the degree of uncertainty in interaction with the service provider. This suggests that complaint will be associated with more undesirable consequences among individuals in high UA societies, who will be more inclined to overlook service problems or decide not to complain than individuals in low UA societies. We therefore expect that social status will be more related to customers’ voice in a low UA country than in a high UA country.

Thus:

H4a

Status will have a stronger influence on recognition of service problems in lower PD cultures than in high PD cultures.

H4b

Status will have a stronger influence on intentions to voice complaints in lower PD cultures than in high PD cultures.

H5a

Status will have a stronger effect on recognition of service problems in lower UA cultures than in high UA cultures.

H5b

Status will have a stronger effect on intentions to voice complaints in lower UA cultures than in high UA cultures.

2 Method

2.1 Data Source and Sample

Data were drawn from the Fall 2003 Eurobarometer 60.0. Established in 1973, the Eurobarometer provides high-quality data for the purpose of multinational comparative research. Surveys are conducted on behalf of the European Commission and are carried out twice a year by national institutes associated with the European Opinion Research Group. Each survey addresses a specific range of topics. The standard Eurobarometer 60.0 used for this paper (see European Commission 2012) focused, among other things, on consumer rights, and sheds light on aspects of customer-complaint intentions and behaviors across cultures.

Eurobarometer employs a multi-stage sampling design. Primary sampling units (PSU’s) are selected from each of the administrative regions in every country, with selection proportional to population size. A cluster of addresses is then selected from each sampled PSU. Within each cluster, addresses are chosen by standard random sampling. Survey data are collected from face-to-face interviews with representative national samples of residents 15 years and older.

For the purpose of the present study we used Eurobarometer data from 12 countries that also participated in the Hofstede et al. (2010) cultural survey, so that all the information was available for analysis from Austria, Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Great Britain, Greece, Ireland, Italy, The Netherlands, Spain and Sweden. Individual cases lacking any of the three dependent variables were excluded from the analysis. The resulting samples ranged from 532 in Great Britain to 856 in Sweden. All national samples were combined into a unified data set, N = 8,479 cases.

2.2 Measures

Descriptive statistics for all dependent variables appear in Table 1, and a summary of the measures in Appendix 1. Problem recognition was measured with a dummy variable (yes = 1), i.e. the response to the question: “Did you ever have to complain to a salesperson, retailer or service provider?” As Table 1 shows, problem recognition was highest in Austria at 54 % and lowest in The Netherlands at 23 %. Intention to complain was measured with a dummy variable (yes = 1) recording the response to: “When you had to complain/if you had to complain about a product or a service, did you complain/would you complain to the salesperson, retailer or service provider?” Responses to this question varied cross-nationally from 36 % in Belgium to 64 % in Ireland. Based on information about distinctions between informal and formal complaining, previous research (Gal and Doron 2007; Voorhees et al. 2006), and questions about the way of complaining, we categorized intentions to complain informally “in person” or “by telephone”, and intentions to complain formally “by post/fax” or “by email”—the latter classified as formal complaint.

Descriptive statistics for all independent variables appear in Table 1. Social Status was measured on the basis of three self-report indicators:

- Gender:

-

Females were considered as low status group (yes = 1). As documented in Table 1, the proportion of females in the various countries is fairly similar, around 50 %.

- Education:

-

A dummy variable (yes = 1) captured individuals whose formal education had ended before the age of 16. Greater cross-national variation is evident in the proportion of individuals with low levels of education, ranging from 10 % in Denmark to 39 % in Greece.

- Age:

-

Elderly customers were considered as a low-status group (we obtained similar results when we used 65 or 75 as the cutoff point). The proportion of elderly individuals was the lowest in Austria, Great Britain, Ireland and The Netherlands at 16 %, and highest in Greece at 27 %.

The Eurobarometer included basic data on educational attainments, but did not include information on other instances of social status, occupational groupings or organizational roles. We controlled for household income to account for discrepancies across social groups in rates of service utilization. Household income was measured with a dummy variable (yes = 1) indicating whether respondents’ household income was in the lower quartile of gross monthly income in each country, because we did not have a cross-nationally comparable continuous income variable (e.g., Giordano and Lindstorm 2010; Iceland et al. 2005; Vannssche et al. 2013).

Concerning country, scores for two culture dimensions were drawn from Hofstede, Hofstede et al. (2010). PD is the degree to which less powerful members of a society take for granted that power distribution is in equal. The scale varies from 11 in Austria, signifying relatively equal distribution of power, to 68 in France. UA is the degree to which members of a society feel uncomfortable with uncertainty and ambiguity. Marked cross-national variation exists in this dimension, with Greece scoring the highest and Denmark the lowest.

2.3 Analysis

We adopted a broad comparative perspective in order to understand national and group level (status group) effects on perceptions of service and intentions to complain. The data consisted of individuals nested within 12 European countries. Taking advantage of this nested structure, we employed a multilevel mixed-effects logistic regression model (see Raudenbush and Bryk 2002) that is specifically appropriate when the data structure includes two or more nested levels and the dependent variable is binary (Gou and Zhao 2000). In particular, we estimated a multilevel model with a Bernoulli distribution, where the “success” probability (e.g., the probability of reporting an intention to complain) is determined by the logistic cumulative distribution function.(Details of the model are available from the authors). The model allows for estimating both random effects (e.g. the mean country log odds of voicing a service complaint) and fixed effects (e.g. the effect of power distance on the mean country log odds of voicing a service complaint). Two levels were estimated simultaneously, one of individuals within countries, and the other of differences across countries. The individual level approach addresses Hypothesis 1, which focuses on the association between status and propensity to complain, while the country level allows examining Hypotheses 2–5, which focus on effects of two cultural dimensions on likelihood of voicing complaint and the status slope. It is important to note that by estimating a country-level random intercept, we allow for country differences in the average propensity to complain. In the cross-cultural comparison, we compare frequency of intentions to voice complaint per nationality or social-status group within a nationality, rather than number of complaints per individual. This is in order to understand whether individuals in certain groups—culture, social status, etc. are more prone to complain than in other groups, and whether they tend to complain formally or informally.

3 Results

As in the literature, behavioral intentions for informal complaints were more frequent than those for formal complaints in all the countries in the sample (See Table 1). Results of the multilevel mixed-effects logistic regression models, which were designed to test our hypotheses relating to intention to voice complaints, are presented in Tables 2 and 3. H1 suggests that customers with higher status will recognize more service problems (H1a) and have stronger intentions to voice complaints (H1b). As Tables 2 and 3 indicate, there was general support for this hypothesis. Specifically, less-educated respondents and elderly individuals reported less likelihood of recognizing service problems (H1a) and fewer intentions to voice complaints (H1b). However, the effect of gender on both dimensions is dissimilar. To illustrate the effects of gender, age and education on both dimensions, Fig. 1 presents the predicted probabilities derived from Model 1 in Tables 2 and 3. For education and age, differences in expected probability are about .15 higher (at about .4) for individuals from higher status groups. A non-significant difference is observed between males and females.

H2 to H3 focused on the effect of national culture on problem recognition and intention to complain. We found customers from lower PD cultures have a higher likelihood of intention to complain (H2b) and of recognizing services failures (H2a), as hypothesized in H2. In support of H3, we found that customers in lower UA cultures reported higher intention to complain (H3b) and had higher likelihood of recognizing service failures (H3a).

We also hypothesized that culture moderates the relationships between social status and problem recognition and between status and intention to complain. Supporting H4, we found a stronger relationship between status and intentions to complain (H4b) in low PD cultures for age and for education, but not for gender. There was no moderating effect of PD on the effect of social status on problem recognition (H4a). In accordance with H5, there was a moderating effect of UA on the association of age and education with intention to complain (H5b), and on association of age with problem recognition (H5a).

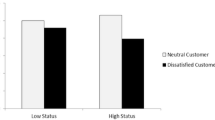

The findings reported in Tables 2 and 3 are illustrated in Fig. 2. The figure distinguishes between countries with more than a standard deviation above the median (i.e. high) and those with a low score (more than a standard deviation below the median) for each cultural dimension. Figure 2 demonstrates the moderating effect of PD on the association between status and intention to complain (H4b), showing that mean probability of intention to complain is higher in countries with low PD. Figure 2 also indicate that there are larger status differences in probability of intention to complain in low PD countries. Finally, Fig. 2 illustrates the moderating effect of UA on the association between status and intention to complain (H5b), i.e. that low UA countries have a higher mean-probability of intention to complain than high UA countries. Furthermore, the status distinction in the probability of intention to complain (between older and younger groups in this case) is much higher in low UA countries.

Predicted probabilities of intention to voice complaints. Note: PD power distance, UA uncertainty avoidance. Sources: Level-1—Eurobarometer 60.0 (2003). Level-2—Hofstede et al. (2010). Note: Probabilities derived from models 3 and 4 in Table 3. Models additionally control for gender, education and household income. High PD indicates scores a standard deviation higher than Level-2 mean. Low PD indicates scores a standard deviation lower than Level-2 mean. High UA—indicates scores a standard deviation higher than Level-2 mean. Low UA—indicates scores a standard deviation lower than Level-2 mean

The results were augmented by three separate checks that support their stability. Apart from the scales developed by Hofstede et al. (2010) that are commonly used, others have recently been developed. To check the sensitivity of our findings to the chosen measures, we repeated our analysis, using PD and UA scores for each country based on scales developed within the GLOBE project (House et al. 2004). These results were largely consistent with those reported above.

To further examine the link between status indicators and voicing intentions, we estimated two models in which composite measures of status were used, and counted the number of low-status occurrences per individual. In this model, the composite measure included occurrences related to education and age, but not to gender.

Results indicate that social status has negative association with problem-recognition, for both the first model (b = −.274, p < .001) and the second model (b = −.488, p < .001), further supporting H1. Similar results were obtained in the two models predicting intention to complain (Model 1—b = −.432, p < .001; Model 2—b = −.769, p < .001). We also found that, when the composite measure was based on education and gender, both PD and UA had a moderating effect on the association between social status and intention to complain (supporting H4 and H5) but not on the association between social status and problem recognition. When the composite measure included gender, the PD and UA had no moderating effect on the association between social status and intention to complain.

It seemed important to elicit whether intentions to raise voice are affected by differences between countries, of e.g. general level of service, or consumer behaviors and skills. Since there are no comparable data on general customer-satisfaction levels across all countries, we used data published by the European Commission, namely the Eurobarometer 73.2/3, conducted in 2010. It provides comparative data on consumer empowerment in all EU countries (see Nardo et al. 2011), using a composite index that includes consumer skills, awareness of consumer legislation, and consumer engagement with service providers. We estimated the models while controlling country-level scores for consumer empowerment scores as reported in Nardo et al. (2011: 33). The results resemble those in Tables 2 and 3.

To better understand the effect of social status and PD and UA on intention to complain, we conducted an additional analysis to distinguish between informal and formal complaining as discrete dependent variables. We found that most customers prefer to complain informally (85.56 %), and only 13.33 % complain formally. We found support for the direct effect of social status on formal complaining in all social-status measures (See Table 4); female customers tend to complain less than male customers, customers with low education tend to complain less than customers with high education, and elderly customers tend to complain less than other customers. We only found support for the direct effect of elderly customers on informal complaining, and none for the two other status groups (gender and education). Elderly customers complain informally less than other customers. We found no support for direct effects of formal or informal complaining (see Table 5), or for interaction between the two cultural dimensions and social status measures. An exception to this is the interaction between power distance and education in predicting formal complaining. We found that there are larger status differences in probability of intention to formally complain in low PD countries.

4 Discussion

This study was motivated by the need to extend existing knowledge regarding factors that underlie customer voice behavior and thus contribute to the literature on the use of indicators regarding citizens’ perceptions of the quality of services to the public. It was designed to test the relationship between social status and dimensions of national culture with two precursors of voicing of service complaints, i.e. recognition of service problems, and intention to complain. It presents a different perspective than the individual level perspective most of the studies on voicing complains commonly take. This study examines macro level social influences of large groups (status groups, nationalities) on voicing complaints. We took advantage of a unique Eurobarometer dataset that enables multi-national comparisons on a scale not usually available in behavioral research.

Our findings indicate that individuals from higher social-status groups recognize more service problems and have stronger intentions to complain (we found support for two social status variables—education and age; but not for gender). We also found that individuals from low PD and UA cultures recognize more service problems and have more intention of voicing service complaints. Lastly, we found an interaction between social status (based on age and education) and two dimensions of national culture (PD and UA) in predicting intent to voice complaints, and an interaction between UA and age in predicting problem recognition. These results demonstrate that the effect of social status on the propensity to complain is neither universal nor identical across cultures. We found significant correlation between social status and propensity to voice complaints only in low PD and UA cultures. This suggests that UA and PD are boundary conditions of the link between social status and propensity to voice complaints.

There is an interesting comparison between formal and informal complaints. First, our results, presented in Table 4, like those of previous research, demonstrate higher frequency of informal voicing of complaints to front-line employees (Gal and Doron 2007; Voorhees et al. 2006). We also demonstrated the universal tendency for informal complaint across the 12 countries in our sample. We agree with Voorhees et al. (2006) that service organizations should develop methods for harvesting and analyzing the information available to front-line service employees in regard to informal complaints. This is important because studies have shown that front-line employees are often unwilling to report complaints to management (Luria et al. 2009). Cultural dimensions did not seem to moderate the relationship between social status and intent to complain (both formal complaint and informal complaint). We found that elderly people complain more formally but no effect was found in regard to education or gender on informal complaining, though all measures of status (age, education and gender) were related directly with formal complaining. It is possible that issues such as fear of retaliation (Miceli et al. 2008; Morrison and Rothman 2009) are stronger in cases of formal complaint, when people have to identify themselves. In the case of informal complaints the complaining is less prominent and the complaint is “concealed” in the service process.

The study has several limitations. First, the dependent and social-status variables were measured from the same source. However, representative samples across 12 countries provide a broad database that reduces the impact of common-source error. The study was also limited to European countries which, although diverse, may not allow for generalization to other national contexts due to possible differences in expectations regarding service quality (Ladhari et al. 2011). Additionally, in the period since collection of the original data, general expectations regarding service quality may have changed. These limitations indicate a need for follow-up with multinational studies, to provide more detailed information about a broader range of dependent variables such as actual complaining, reasons for not complaining (Doron et al. 2011), and satisfaction with handling of complaints. Furthermore, this study does not distinguish between voicing complaints in the private and the public sector. Future studies that focus on actual complaining can also differentiate the actual complaining per sector and find out if differences do exist between the private and public sector in voicing complaints. If comparable data on customer satisfaction or service quality levels across countries become available in the future, they can help to further refine results such as those presented in the present study and provide a control for a separate source of variability across countries that may influence voice-related behaviors.

Moreover, due to data limitations related to the use of an existing data source, both education and income were operationalized as binary variables distinguishing between individuals with lower status and all other persons. We hope that future surveys of customer voicing will also employ cross-national comparisons of education and income. The international standard classification of education—ISCED (UNESCO 2012)—can be deployed for measurement of education. A comparable income measure is needed to account for both cross-national differences in income dispersion (our current measure) and purchasing-power parities, which we were unable to account for in our analysis. Finally, data constraints limited the scope of individual level information included in our models. Hence, our findings on the impact of age and education may be understood as reflecting demographic effects rather than revealing the impact of social status. Future research incorporating richer individual-level information is desirable.

Sources such as the Eurobarometer have numerous advantages for the study of social voicing when associated with availability of nationally representative samples and uniform and comparable sampling and instruments across national groups, However, such broad data sources also impose restrictions that can be ameliorated by careful design of additional studies that, while possibly being smaller in scope, will achieve the necessary level of detail for fuller understanding of social voicing and complaining behavior.

5 Conclusions

Our findings are applicable to service organizations because many of them are global, serving customers from a variety of cultures and social groups. A model frequently discussed in the field of global management is that of cultural fit (Aycan et al. 1999; Mendonca and Kanungo 1994; Aycan et al. 2000). It suggests that management practices should be a function of internal organizational characteristics and external environment, including their socio-cultural aspects. Better understanding of the effects of service practices demands a wider perspective that includes the social environment.

It is possible that customers from low social-status groups and/or high PD/UA cultures should be encouraged to voice their complaints. Bitner and Brown (2008) suggested that in order to improve quality of life through services “there is a need for services focused on the world’s poor, those who cannot afford the luxuries that many of us consider necessities today” (p. 44). Our results concerning social status demonstrate that there is also a need to focus on how individuals from low status groups use existing services. It is possible that by empowering these groups to voice their needs they may eventually be able to improve their quality of life based on existing services. Social studies (see review in Narayan-Parker 2002) have already demonstrated the effect of empowerment on poor communities in relation to voicing (e.g. organizing a collective voice). Perhaps, if low-status groups voice their comments in the service context (without being organized), this will improve their quality of life.

Furthermore, service organizations and national or international bodies that use statistics about complaints should not assume that better service is received according to lower rates of complaint. This study demonstrates that these may be affected by beliefs regarding Power Distance and Uncertainty Avoidance. We also demonstrate that use of social indicators reflecting consumer perceptions or satisfaction with services may need statistical correction (see also Rhys and Van de Walle 2013) in order to better compare and understand underlying problems concerning quality of such services.

References

Abbate, R., Giambalvo, O., & Milito, A. M. (2001). Service and life quality: The case of Palermo. Social Indicators Research, 54, 275–308.

Andreasen, A. (1985). Consumer responses to dissatisfaction in loose monopolies. Journal of Consumer Research, 12, 135–141.

Aycan, Z., Kanungo, R., Mendonca, M., Yu, K., Deller, J., Stahl, G., & Kurshid, A. (2000). Impact of culture on human resource management practices: A 10-country comparison. Applied Psychology, 49(1), 192–221.

Aycan, Z., Kanungo, R. N., & Sinha, J. B. (1999). Organizational culture and human resource management practices: The model of culture fit. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 30(4), 501–526.

Berger, J., Rosenholtz, J. S., & Zelditch, M., Jr. (1980). Status organizing process. Annual Review of Sociology, 6, 479–508.

Bitner, M. J., & Brown, S. W. (2008). The service imperative. Business Horizons, 51, 39–46.

Botero, I. C., & Van Dyne, L. (2009). Employee voice behavior interactive effects of LMX and power distance in the United States and Colombia. Management Communication Quarterly, 23(1), 84–104.

Brockner, J., Ackerman, G., & Fairchild, G. (2001). When do elements of procedural fairness make a difference? A classification of moderating influences. In Cropanzano, R., & Greenberg, J. (Eds.), Advances in organizational justice (pp. 179–2012). Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Burgoon, M., Dillard, J. P., Doran, N. E., & Milller, M. D. (1982). Cultural and situational influences on the process of persuasive strategy selection. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 6(1), 85–100.

Buttle, F., & Burton, J. (2002). Does service failure influence customer loyalty? Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 1(3), 217–227.

Dagger, T. S., & Sweeney, J. C. (2006). The effect of service evaluations on behavioral intentions and quality of life. Journal of Service Research, 9(1), 3–18.

Detert, J. R., & Burris, E. R. (2007). Leadership behavior and employee voice: Is the door really open? Academy of Management Journal, 50, 869–884.

Dickson, M. W., Aditya, R. N., & Chhokar, J. S. (2000). Definition and interpretation in cross-cultural organizational culture research: Some pointers from the GLOBE research program. In N. Ashkanasy, C. Wilderom, & M. F. Peterson (Eds.), Handbook of organizational culture and climate (pp. 447–464). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Dong-Jin, L., & Sirgy, M. J. (2004). Quality-of-life marketing: proposed antecedents and consequences. Journal of Macromarketing, 24(1), 44–58.

Doron, I., Gal, I., Shavit, M., & Weisberg-Yosub, P. (2011). Unheard voices: Complaint patterns of older persons in the healthcare system. European Journal of Aging, 8, 63–71.

Edmondson, A. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44, 350–383.

European Commission. (2011). The Consumer Empowerment Index. Retrieved 15 June, 2014: http://ec.europa.eu/consumers/consumer_empowerment/docs/JRC_report_consumer_empowerment_en.pdf.

European Commission. (2012). A European Consumer Agenda—Boosting confidence and growth COM(2012) 225 final. Retrieved 15 June, 2014 from: http://ec.europa.eu/consumers/archive/strategy/docs/consumer_agenda_2012_en.pdf.

Fisek, M. H., Berger, J., & Norman, R. Z. (1991). Participation in heterogeneous and homogeneous groups: A theoretical integration. American Journal of Sociology, 97(1), 114–142.

Fornell, C., & Wernerfelt, B. (1988). A model for customer complaint management. Marketing Science, 7(3), 287–298.

Fuller, J. B., Marler, L. E., & Hester, K. (2006). Promoting felt responsibility for constructive change and proactive behavior: Exploring aspects of an elaborated model of work design. Journal of OrganizationalBehavior, 27, 1089–1120.

Gal, I., & Doron, I. (2007). Informal complaints on health services: Hidden patterns, hidden potentials. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19(3), 158–163.

Gane, N. (2005). Max Weber as a social theorist: ‘Class, status, party’. European Journal of Social Theory, 8(2), 211–226.

Gelfand, M. J., Erez, M., & Aycan, Z. (2007). Cross-cultural organizational behavior. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 479–514.

Giordano, G. N., & Lindstorm, M. (2010). The impact of changes in different aspects of social capital and maternal conditions on self-rated health over time: A longitudinal cohort study. Social Science Medicine, 70, 700–710.

Goodman, J. (1999). Basic facts on customer complaint behavior and the impact of service on the bottom line. Competitive Advantage, 9(1), 1–5.

Gou, G., & Zhao, H. (2000). Multilevel modeling for binary data. Annual Review of Sociology., 26, 441–462.

Gruber, T., Szmigin, I., & Voss, R. (2009). Handling customer complaints effectively: A comparison of the value maps of female and male complainants. Managing Service Quality, 19(6), 636–656.

Gutek, B. A. (1995). The dynamics of service: Reflections on the changing nature of customer/provider interactions. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Hirokawa, G., & Miyahara, A. (1986). A comparison of influence strategies utilized by managers in American and Japanese organizations. Communication Quarterly, 34, 250–265.

Hirschman, A. O. (1970). Exit, voice, and loyalty. Responses to decline in firms, organizations and states. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture’s consequences: International differences in work-related values. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G. J., & Minkov, M. (2010). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind (Rev 3 ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Homburg, C., & Furst, A. (2005). How organizational complaint handling drives customer loyalty: An analysis of the mechanistic and the organic approach. Journal of Marketing, 69, 95–114.

House, R. J., Hanges, P. J., Javidan, M., Dorfman, P., & Gupta, V. (2004). Culture, leadership, and organizations: The GLOBE Study of 62 Societies. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

House, R. J., Hanges, P. J., Ruiz-Quintanilla, S. A., Dorfman, P. W., Javidan, M., Dickson, M., & Gupta, V. (1999). Cultural influences on leadership: Project globe. In W. Mobley, J. Gessner, & V. Arnold (Eds.), Advances in Global Leadership, 1 (pp. 171–233). Stanford, CT: JAI Press.

House, R. J., Javidan, M., Hanges, P. J., & Dorfman, P. W. (2002). Understanding cultures and implicit leadership theories across the globe: An introduction to project GLOBE. Journal of World Business, 37, 3–10.

Iceland, J., Sharpe, C., & Steinmetz, E. (2005). Class differences in African American residential patterns in US metropolitan areas: 1990–2000. Social Science Research, 34, 252–266.

Islam, G., & Zyphur, M. J. (2005). Power, voice, and hierarchy: Exploring the antecedents of speaking up in groups. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 9(2), 93–103.

Johnson, M. D., Gustafsson, A., Andreassen, T. W., Lervik, L., & Cha, J. (2001). The evolution and future of national customer satisfaction index models. Journal of economic Psychology, 22(2), 217–245.

Kasper, H., van Helsdingen, P., & De Vries, W. (1999). Services marketing management: An international perspective. New York: Wiley.

Ladhari, R., Pons, F., Bressolles, G., & Zins, M. (2011). Culture and personal values: How they influence perceived service quality. Journal of Business Research, 64, 951–957.

LePine, J. A., & Van Dyne, L. (1998). Predicting voice behavior in work groups. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83, 853–868.

Liao, H. (2007). Do It right this time: The role of employee service recovery performance in customer-perceived justice and customer loyalty after service failures. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(2), 475–789.

Luria, G., Cnaan, R. A., & Boehm, A. (2014). National culture and prosocial behaviors: Results from 66 countries. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 1–25. doi:10.1177/0899764014554456.

Luria, G., Gal, I., & Yagil, D. (2009). Employees willingness to report service complaints. Journal of Service Research, 12(2), 156–174.

Maxham, J. G., & Netemeyer, R. G. (2002).A longitudinal study of complaining customers’ evaluation of multiple service failures and recovery efforts. Journal of Marketing, 66, 57–71.

Mendonca, M., & Kanungo, R. N. (1994). Managing human resources the issue of cultural fit. Journal of Management Inquiry, 3(2), 189–205.

Miceli, M. P., Near, J. P., & Dworkin, T. M. (2008). Whistle-Blowing in Organizations. New York: Psychology/Taylor & Francis.

Morgeson, F. V., & Petrescu, C. (2011). Do they all perform alike? An examination of perceived performance, citizen satisfaction and trust with US federal agencies. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 77(3), 451–479.

Morrison, E. W., & Rothman, N. B. (2009). Silence and the dynamic of power. In J. Greenberg, M. S. Edwards (Eds.), Voice and silence in organizations (pp. 111–133). UK: Emerald Group Publishing.

Narayan-Parker, D. (Ed.). (2002). Empowerment and poverty reduction: A sourcebook. USA: World Bank Publications.

Nardo, M., Loi, M., Rosat, R., & Manca A. (2011). The consumer empowerment index: A measure of skills, awareness and engagement of European consumers. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. Retrieved June 20, 2014: http://ec.europa.eu/consumers/consumer_empowerment/docs/JRC_report_consumer_empowerment_en.pdf.

Njoh, A. j. (1994). A client-satisfaction-based model of urban public service delivery organizational effectiveness. Social Indicators Research, 32, 263–296.

Ostrom, A. L., Bitner, M. J., Brown, S. W., Burkhard, K. A., Goul, M., Smith-Daniels, V., & Rabinovich, E. (2010). Moving forward and making a difference: Research priorities for the science of service. Journal of Service Research, 13(1), 4–36.

Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V. A., & Berry, L. L. (1988). SERVQUAL: A multiple-item scale for measuring consumers perceptions of service quality. Journal of Retailing, 64(1), 12–37.

Raudenbush, S. W., & Bryk, A. S. (2002). Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Rhys, A., & Van de Walle, S. (2013). New public management and citizens’ perceptions of local service efficiency, responsiveness, equity and effectiveness. Public Management Review, 15(5), 762–783. doi:10.1080/14719037.2012.7257.

Ridgeway, G. (2006). Assessing the effect of race bias in post-traffic stop outcomes using propensity scores. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 22, 1–29.

Ridgeway, C. L., & Correll, S. J. (2006). Consensus and the creation of status beliefs. Social Forces, 85(1), 431–453.

Ridgeway, C. L., & Erickson, K. G. (2000). Creating and spreading status beliefs. American Journal of Sociology, 106(3), 579–615.

Schneider, B., & Bowen, D. (1995). Winning the service game. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Singh, J. (1989). Determinants of consumers decisions to seek third party redress: An empirical study of dissatisfied patients. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 23(4), 329–363.

Skvoretz, J., & Fararo, T. J. (1996). Status and participation in task groups: A dynamic network model. American Journal of Sociology, 101, 1366–1414.

Soares, M., Farhangmehr, M., & Shoham, A. (2007). Hofstede’s dimensions of culture in international marketing studies. Journal of Business Research, 60, 277–284.

Stamper, C. L., & Van Dyne, L. (2001). Work status and organizational citizenship behavior: A field study of restaurant employees. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 22(5), 517–536.

Suki, N. M. (2014). Moderating role of gender in the relationship between hotel service quality dimensions and tourist satisfaction. Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality & Tourism, 15(1), 44–62.

Tangirala, S., & Ramanujam, R. (2008). Exploring non-linearity in employee voice: The effects of personal control and organizational identification. Academy of Management Journal, 51(6), 1189–1203.

Thorelli, H. B. (1971). Concentration of information power among consumers. Journal of Marketing Research, 8, 427–432.

Triandis, H. C. (1994). Culture and social behavior. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Tsai, C. T., & Su, C. S. (2009). Service failures and recovery strategies of chain restaurants in Taiwan. Service Industries Journal, 29(12), 1779–1796.

Tyler, T. R., Lind, E. A., & Huo, Y. J. (2000). Cultural values and authority relations: The psychology of conflict resolution across cultures. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 6(4), 1138.

UNESCO. (2012). International Standard Classification of Education—ISCED 2011. Montreal: UNESCO Institute for Statistics.

Van Dyne, L., Ang, S., & Botero, I. C. (2003). Conceptualizing employee silence and employee voice as multidimensional constructs. Journal of Management Studies, 40(6), 1359–1392.

Vannssche, S., Swicegood, G., & Matthijs, K. (2013). Marriage and children as a key to happiness? Cross-national differences in the effect marital status and children on well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 14, 501–524.

Vigoda-Gadot, E., & Mizrahi, S. (2008). Public sector management and the democratic ethos: A 5-year study of key relationships in Israel. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 18, 79–107.

Voorhees, C. M., Brady, M. K., & Horowitz, D. M. (2006). A Voice from the silent asses: An exploratory and comparative analysis of noncomplainers. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 34(4), 514–527.

Warland, R. H., Herrman, R. O., & Willits, J. (1975). Dissatisfied consumers: Who gets upset and who takes action. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 6, 148–163.

Weber, M. (1968). Economy and society. New York: Bedminster Press.

Webster, M. J., & Foschi, M. (1988). Over- view of status generalization. In M. Webster Jr., & M. Foschi (Eds.). New theory and research. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Webster, M. J., & Hysom, S. J. (1998). Creating status characteristics. American Sociological Review, 63(3), 351–378.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

See Table 6.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Luria, G., Levanon, A., Yagil, D. et al. Status, National Culture and Customers’ Propensity to Complain. Soc Indic Res 126, 309–330 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-0884-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-0884-y