Abstract

The positive relationship between trust and happiness has been demonstrated by the literature. However, it is not clear how much this relationship depends on environmental conditions. The Great East Japan Earthquake of 2011 is considered one of the most catastrophic events in human history. This disaster caused not only physical damage for Japanese people, but also perceived damage. Using individual-level panel data from Japan covering the period 2009–2012, this paper attempts to probe how the relationship between trust and happiness was influenced by the Great East Japan Earthquake by comparing the same individuals before and after the earthquake. A fixed-effects estimation showed that there is a statistically well-determined positive relationship between trust and happiness and this relationship was strengthened by disaster, especially for residents in the damaged area. We argue that social trust is a substitute for formal institutions and markets, which mitigates the effect of disaster-related shock on psychological conditions such as happiness. Therefore, a trustful society is invulnerable to a gigantic disaster.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

It has become increasingly difficult for researchers to ignore the wealth of benefits that social capital, which can be defined broadly as a combination of social trust, interpersonal networks, and community participation, has on personal well-being (Putnam 1993, 2000). While its benefits for an individual’s health status have been well described by the framework of social supports in the health literature (e.g., Kawachi et al. 1997, 1999, 2007), in theory the relationship between social capital and an individual’s overall evaluation of quality of life [or subjective well-being (SWB) in general] is not as well developed.

For example, it is less well known in the literature that the relationship between trust and SWB might be context specific. Helliwell (2011) notes that crises can improve both trust and SWB when initial values of trust are sufficiently high, e.g., Minamata in Japan (Kusago 2011), and Aceh in Indonesia (Deshmukh 2009). On the other hand, crises can reduce both trust and happiness when initial values of trust are low, e.g., Jaffna in Sri Lanka (Deshmukh 2009). The relationship between trust and happiness might also depend on the level of law and order in a given society. Even if people do not trust each other, markets can still function well by themselves, as long as the public authority and law and order are reliable. However, if law and order break down, people in a low-trust society will likely avoid making any transactions in the market in fear of being cheated out of their investment. In such a society, people will also be more likely to resort to dishonest behaviors or illegal activities, such as looting or robbery, which might have a significantly negative externality on people’s happiness. The implication of this behavior is that trust may play a very important role in reducing any potential negative externalities on people’s happiness that might arise when formal laws are not functioning well.

In 2010, after the Great Haiti Earthquake, “a crowd beat a suspected thief to death and dragged his body through the streets” (Aldrich 2012:24).Footnote 1 This shows that a society lacking in trust tends to be ruled by violence and terror. This distrust could be considered a secondary tragedy for the Haitian population. The Great Haiti Earthquake showed us that distrustful human relations have the potential to magnify people’s negative individual experiences following a disaster. In 2005, after Hurricane Katrina in the United States, cooperative behavior was not observed and uprisings and stealing were rampant and prevalent (Kawachi 2013:15–16). In contrast with the Great Haiti Earthquake and Hurricane Katrina, disturbances did not arise immediately after the Great East Japan Earthquake, and there is evidence that the Japanese people were “weathering the storm” with great patience (Ono 2012; Kawachi 2013). We can argue that the Great East Japan Earthquake provides one of the most interesting case studies of trust and happiness in recent times.Footnote 2

Many studies have found a positive relationship between social capital and different measures of SWB (e.g., Putnam 2000; Bjørnskov 2003, 2006; Helliwell 2003, 2006a, b; Powdthavee 2008; Helliwell and Wang 2011; Kuroki 2011).Footnote 3 However, the majority of these studies are based on cross-sectional data sets obtained from countries during a relatively stable time period. To the best of our knowledge, virtually none of these papers studied the relationship between trust and SWB during an emergency.

On the other hand, studies on the psychological impact of disasters found that natural disasters had a sizable effect on measures of SWB, including happiness and life satisfaction (e.g., Carroll et al. 2009; Luechinger and Saschkly 2009; Becchetti and Castriota 2010).Footnote 4 Researchers have attempted to investigate the psychological impact of the Great East Japan Earthquake on the Japanese people (Ishino et al. 2011; Hanaoka et al. 2014; Uchida et al. 2014) and also on the German people’s perception of disaster (Goebel et al. 2013). However, these works do not consider how trust was related to SWB by comparing trust before and after the disaster. Our novel contribution is to make it evident that social trust plays a significant role in moderating people’s SWB following an unexpected, devastating shock.Footnote 5

We structure our paper as follows: Sect. 2 is an overview of the Fukushima accident. Section 3 explains the data used in this paper and proposes testable hypotheses and a method. Section 4 reports the estimation results. Section 5 concludes.

2 Overview of the Great East Japan Earthquake

A devastating earthquake hit Japan on March 11, 2011, which caused a tsunami and triggered a nuclear accident at Fukushima. The Great East Japan Earthquake is considered one of the most catastrophic events in human history. The earthquake occurred off the coast of Japan and its magnitude was estimated as 9.0 (Daily Yomiuri 2011a), which was the fourth largest recorded earthquake in history.

The Japanese disaster was particularly damaging because the earthquake also caused a devastating tsunami. The powerful tsunami waves pushed water up to heights of more than 20 m in some coastal areas of the northeastern coast of Japan (Daily Yomiuri 2011b).Footnote 6 Many people who were living on or nearby the coastal areas were unable to escape the tsunami and approximately 16,000 people died (National Police Agency 2014). In addition, residents in the prefectures of Iwate, Miyagi, and Fukushima, which are coastal prefectures located in Japan’s northeast regions, all experienced the destructive force of the earthquake and tsunami, and survived to find untold damage.Footnote 7 In the current study, we focus our attention on these three prefectures. Before the disaster, these areas were experiencing depopulation and their populations were in decline, with the exception of Sendai in Miyagi prefecture.Footnote 8 Before the disaster, in 2008–2009, the population decreased by 8.7, 6.0, and 0.7 % in Iwate, Fukushima, and Miyagi prefectures, respectively.Footnote 9

Although the victims of the disaster had to experience many difficulties during the emergency, most people were patient and did not resort to any unlawful behaviors in any significant way. Looting and robbery were not observed in the stricken area (Ono 2012). In addition, instead of creating more turmoil and/or resorting to rioting, altruistic behavior towards the victims of the disaster was common in Japan during the aftermath. The victims of the disaster assisted each other and helped whenever they could (Kawachi 2013:15–16).Footnote 10 Prior to the Great East Japan Earthquake, in 1995, the Great Hanshin–Awaji Earthquake hit Japan and caused catastrophic damage. A large number of young people volunteered to help in the rescue and cleanup in Kobe, which was hit directly by the earthquake. The Great Hanshin–Awaji Earthquake greatly motivated people to volunteer (Yamamura 2014). A similar phenomenon was observed following the Great East Japan Earthquake. For example, 13-year-old boys performed volunteer work in the stricken area with their fathers and “in the car on our way home, the boys all told that they wanted to volunteer again in Tohoku” (Matsutani 2011).

3 Data and Hypothesis

3.1 Data

The Survey of Life Satisfaction and Preferences provided our data set. As part of the Global Center of Excellence (GCOE) program, Human Behavior and Socioeconomic Dynamics performed by Osaka University, the data were purposefully compiled to scrutinize individual subjective perceptions from a socioeconomics perspective. Hereafter, these data are called GCOE data.

Since 2004, the panel survey has been conducted annually to cover all parts of Japan. The collection of data is based on the random-sampling method. Respondents are male and female adults aged between 20 and 69 years. The data provided information regarding basic socioeconomic individual characteristics such as age, sex, household income, family members, degree of generalized trust, degree of happiness, and residential place. New respondents were added to the survey waves in 2004, 2006, and 2009. Questions concerning the key variables such as generalized trust and happiness were only included in the questionnaire during the 2010–2013 surveys. Therefore, data used in this paper covered only 4 years (2010–2013). The survey was conducted from January to February each year. Therefore, the 2011 data had already been collected when the Great East Japan Earthquake occurred on March 11. Therefore, the data from 2010 and 2011 can be defined as predisaster data while the data from 2012 and 2013 can be defined as postdisaster data.

Previous studies on the relationship between trust and happiness were not based on individual-level panel data (e.g., Bjørnskov 2003, 2006; Helliwell 2003, 2006a, b; Ram 2009; Kuroki 2011). It is crucial to eliminate the individual time-invariant traits and follow the same individuals to scrutinize how SWB is determined (Powdthavee 2010:49–73). The advantage of the GCOE panel data is that it allows us to follow the same individuals and account for the individual fixed effects in the analysis of the relationship between trust and happiness. Hence, this paper is anticipated to provide a robustness check of previous works in the literature.

Table 1 presents the definition of the variables used in this paper, as well as their mean values during the period 2010–2013. It also presents t-tests on the differences in the means between residents in the damaged area and those in other areas. The key variables are Happiness, Trust, After disaster, and Damaged.

Individual happiness levels were elicited using the following question, “How would you rate your current level of happiness?” Responses were scored on an 11-point Likert scale, which is used to measure the degree of happiness from 0 (very unhappy) to 10 (very happy). To identify the trust level of respondents, respondents were asked, “In general, are most people trustworthy?” Their responses were scored on a 5-point Likert scale from one (completely disagree) to five (completely agree).

The mean Happiness in the damaged area was 6.32 compared with 6.48 recorded in other areas. We can reject the null hypothesis that the two means are the same at the 1 % level, which suggests that, on average, residents in the damaged area reported a 0.16-point lower happiness level on the 11-point scale compared with residents in other areas. However, there was no statistical significance even though the mean value for Trust in the residents from the damaged area is slightly larger than for other areas. That is, the trust level of residents in the damaged area was almost equivalent to that of residents in other areas.

The mean value for Income for residents in the damaged area was 5.93 million yen, which was significantly less than for those in other areas. The variable Family for residents in the damaged area was 4.40, which was significantly larger than for residents in other areas (4.02). In the dataset, residential places were scaled into the classifications of large-sized city, medium-sized city, small city, and village (or town).Footnote 11 Dummies for these were constructed, with the exception of large-sized city because a large-sized city was defined as the reference group in this paper. Mean values for dummies of Medium city, Small city, and Village for residents in the damaged area were 0.32, 0.29, and 0.12, respectively. We can interpret this as an indication that when the sample was restricted to the damaged area, 32, 29, and 12 % of respondents resided in the medium-sized city, small city, and village (or town), respectively. However, the mean values for Medium city, Small city, and Village for residents in other areas were 0.42, 0.22, and 0.08, respectively. Respondents in the damaged area were more likely to reside in a small city or village (or town) than in other areas. These values show that the damaged areas can be characterized as having lower income, larger family size, and less urbanization.

3.2 Hypotheses

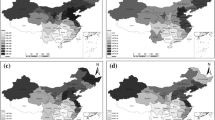

Using the GCOE data, Fig. 1 shows the mean values of Trust and Happiness in each prefecture to illustrate the association between trust and happiness. A cursory examination of Fig. 1 reveals a positive association, which is in line with existing works (e.g., Bjørnskov 2003; Kuroki 2011). Figure 2 illustrates the change in happiness level based on a subsample of residents of the damaged area and of other areas. During the study period, the happiness level of residents in the damaged area was smaller than that of other areas. This might reflect that most of the damaged areas, with the exception of Sendai in Miyagi prefecture, had already experienced a declining population prior to the disaster. It can be clearly seen that the happiness level in the damaged area was lowered in 2012, i.e., after the disaster, compared with the happiness level measured in January or February of 2011, i.e., before the disaster. By 2013, the happiness level in the damaged area increased to a level almost equivalent to the level before the disaster. These findings imply that the disaster had a detrimental effect on happiness levels, but that the effect is not persistent. Despite the enormous material damage caused by the disaster, people affected by the disaster had almost adapted completely to their situation 2 years afterward. In comparison, the happiness level in other areas was maintained at almost the same level during this period. It seems that the disaster had not significantly influenced the happiness level of people who resided in other areas that were not directly affected by the disaster.

Figure 3 demonstrates the change in Trust based on the subsample of residents from the damaged area and the sample of residents in other areas. The level of trust increased for residents in the damaged area from 2010 to 2011, i.e., the period prior to the disaster. From 2011 to 2012, the level of trust declined, which possibly reflected the effect of the disaster. That is, the natural disaster decreased the level of trust, which is incongruent with the findings by Toya and Skidmore (2012). This may partly be because Toya and Skidmore (2012) used cross-country data instead of individual-level data. In 2013, the trust level had recovered to a level almost equivalent to that before the disaster. We argue that these findings show that the trust level is stable unless a disaster occurs. However, the level of trust of the residents in other areas was lower than that of residents in the damaged area before the disaster. However, trust in other areas had caught up with the level of trust in the damaged area following the disaster. Overall, the levels of trust in other areas increased consistently during this period.

Following existing works (Bjørnskov 2003, 2006; Helliwell 2003, 2006a, b; Kuroki 2011), we postulate Hypothesis 1:

Hypothesis 1

Trust is positively associated with happiness.

The importance of social trust is expected to be of significant importance in the period following a natural disaster (Toya and Skidmore 2012). People are very uneasy after a disaster. In this situation, trust is thought to alleviate their uneasiness. However, the relation between unexpected events and trust (and SWB) is thought to be more conditional. Helliwell et al. (2014) argued that the economic crisis has been shown to have very large and enduring effects in countries with low initial social capital (Italy, Greece, Spain, and Portugal), but smaller and ephemeral effects in countries with higher levels of social capital, even if they were initially hit as hard or harder by the crisis. The economies of Ireland and Iceland are obvious examples of these effects, which we hypothesize to be the case for Japan. Therefore, we provide Hypothesis 2:

Hypothesis 2

The positive relationship between trust and happiness is stronger after a disaster than before a disaster if the initial trust level is sufficiently high.

Damage from the disaster is likely to be significantly different between the areas where the earthquake and tsunami directly hit and more distant places. Markets and formal institutions are less likely to function well in the damaged areas. In this situation, trust plays an important role in maintaining order and preventing the population from rioting. During a great emergency and more serious situation, the ability to maintain law and order is crucial in keeping people’s mental conditions stable. Therefore, we propose Hypothesis 3, which we hypothesize to be the case for Japan:

Hypothesis 3

Trust is more strongly related to happiness in the damaged area after the disaster than before the disaster if the initial trust level is sufficiently high.

3.3 Method

Our purpose is to examine the effect of disaster and trust in 2011 on the level of happiness in the Japanese people. First, we compared the residents living in other areas with the residents residing in the prefectures that had been directly hit by the earthquake in 2011. We focused on the effect of levels of trust.Footnote 12

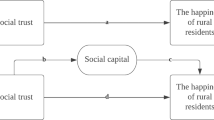

To test Hypothesis 1, the estimated function takes the following form:

where Happiness itp represents the dependent variable in individual i, year t, and prefecture p. k i represents time-invariant individual-level fixed effects. Time-invariant features such as schooling years and gender dummy are completely captured by k i and are not included as independent variables. The regression parameters are denoted by α. Y is the vector of the individual-level control variables, which capture the influence of the various respondents’ individual characteristics. Its vector of the regression parameters is denoted as B. The error term is denoted by u. After disaster takes 1 when observations are collected in 2011 or 2012, otherwise 0. If the disaster decreases happiness level, the predicted sign of After disaster is negative. Then, Trust is expected to show a positive sign if Hypothesis 1 is supported.

To examine Hypothesis 2, the function form is described below:

If the coefficient After disaster t × Trust has a positive sign, trust is more positive and strongly related to happiness after the disaster than before the disaster. Therefore, from Hypothesis 2, Disaster t × Trust is expected to show a positive sign.

To examine Hypothesis 3, the function form is described below:

If the coefficient of After disaster t ×Trust × Damaged takes a positive sign, then this would imply that the positive relationship between trust and happiness for those who had suffered from the natural disaster is enhanced. Hence, from Hypothesis 3, the sign of the coefficient of After disaster t × Trust × Damaged is predicted to be positive. For the control variables, household income was included to examine the effect of income on happiness levels. In the fixed effects model employed in this paper, the variation of income for the same individual is captured during the period 2010–2013. Apart from the income level as an independent variable to control factors related to happiness levels, this work also incorporates respondent ages, dummies for marital status, number of family members (Family), and dummies for residential places. The effect of age on happiness was found to be nonlinear (e.g., Clark and Oswald 1996; Blanchflower and Oswald 2004; Kuroki 2011). Therefore, with the aim of testing the nonlinear effect of age, in addition to Age, Age squared is included. Marital status is known to affect happiness levels (e.g., Oswald and Powdthavee 2008; Powdthavee 2008; Clark et al. 2008; Frijters et al. 2011). Therefore, three dummies (Unmarried, Divorced, and Widow) are included to capture marital status when currently married people are used as the reference group. As mentioned earlier, the damaged area is mainly a small-scale rural and depopulated place. However, the damaged area also includes Sendai, which is the most urbanized city in northeastern Japan. This variation in residential places should be controlled for. This work includes three dummies for residential place (Medium city, Small city, and Village) when the large-sized city is used as the reference group. In addition, eight occupation dummies (agriculture, fishery, constructing, or education), and seven residence dummies (private rented house, public rented house, company-owned house, or apartment house) are included.

4 Results

Tables 2, 3 and 4 report the estimates obtained from the fixed effects model. Table 2 shows the results where the interaction term is not included and Hypothesis 1 is examined. Table 3 presents the results of the model where the interaction term, After disaster t × Trust, is included to examine Hypothesis 2. Table 4 presents the results of the model where the interaction term between three variables, Disaster t × Trust × Damaged, is included to test Hypothesis 3.

Table 2 shows that the after-disaster dummy (covering the period 2012–2013) has a positive sign in all regression equations, which is consistent with previous work exploring the effect of the Great East Japan Earthquake (Ishino et al. 2011; Uchida et al. 2014). However, After disaster was not statistically significant, which shows that there is no statistical difference in happiness levels before and after the disaster. Consistent with our prediction, the coefficient of Trust yields a positive sign and was statistically significant at the 1 % level in all columns. Hypothesis 1 is strongly supported. Income yields a positive sign and is statistically significant at the 1 % level, which is consistent with our prediction. In the result shown in column (4) of Table 2, the absolute value of the coefficient of Trust is 0.09, which indicates that trust increases by 1 point, leading to an increase in happiness by 0.09 points on the 11-point Likert scale. However, the absolute value of the coefficient of Income is 0.014, which implies that household income increases by one million yen, leading to an increase in happiness by 0.014 points on the 11-point Likert scale. Therefore, the effect of a 1-point increase in Trust on the 5-point Likert scale is almost equivalent to an increase in 6.4 million yen (US $80,000).Footnote 13 Based on the whole GCOE data sample, the average household income is around 6.3 million yen. Therefore, the effect of a 1-point increase in Trust on the 5-point Likert scale is considered to be approximately equivalent to the average annual income in Japan. This is an exceedingly large value, which seems to reflect the estimation bias of income effects. Therefore, its effect is thought to decrease drastically after correcting for the bias (Powdthavee 2010:86–91).Footnote 14 Instead of household income, let us consider the effect of trust by using a marital status dummy (Unmarried). The coefficient’s absolute value of Unmarried is 0.35 and its sign is negative, which means that unmarried people’s happiness levels were lower by 0.35 points than for married people. Therefore, a 4-point increase in Trust compensates for the gap in happiness between married and unmarried people.Footnote 15

As for other control variables, the signs of the Age and Age squared coefficients are negative and positive, which suggests a U-shaped relationship between happiness and age. Furthermore, they are statistically significant in columns (3) and (4). This indicated that the relationship between age and happiness is U-shaped, as often found in the happiness literature (Clark and Oswald 1996; Blanchflower and Oswald 2004; Kuroki 2011). With respect to marital status, the coefficient of Unmarried, Divorced, and Widow has the negative sign in all estimations. They are almost statistically significant, which is in line with previous work (e.g., Oswald and Powdthavee 2008; Powdthavee 2008; Clark et al. 2008; Frijters et al. 2011).Footnote 16 Turning to scales of residential area, Medium city, Small city, and Village show positive signs, with the exception of Small city. However, these dummy variables are not statistically significant in any column, thus suggesting that there are statistically insignificant differences in the happiness levels between scales of residential place. Eight occupation dummies and seven residence dummies are included in the specification presented in column (4). None show statistical significance; therefore, happiness levels do not differ between occupations and types of residence although this is not reported in Table 2.

We now focus on the interaction term between the After disaster dummy and degree of Trust in Table 3. The sign of After disaster × Trust is negative albeit statistically insignificant, which is not consistent with Hypothesis 2. Conversely, Trust shows a positive sign and is statistically significant at the 1 % level. Therefore, the relationship between trust and happiness does not change after the disaster in Japan although trust is positively related to happiness.

Table 4 shows that the interaction term After disaster × Trust × Damaged produces a positive sign and is statistically significant across all columns. The positive relationship between trust and happiness is stronger for residents in the damaged areas than in other areas following the disaster. This strongly supports Hypothesis 3. Apart from this, it is interesting to observe that the coefficient After disaster × Damaged is negative and statistically significant across all columns. The happiness level for residents in the damaged area declined directly after the disaster, which is in line with Fig. 2. Furthermore, considering the results of After disaster in Table 2 and After disaster × Damaged leads us to claim that the disaster reduced the happiness levels in the damaged area, but did not change it throughout Japan. Trust continues to show a significant positive sign in columns (1)–(4). The discussions of the results shown in Tables 2, 3 and 4 strongly support Hypotheses 1 and 3.

In discussing the economic significance derived from the results shown in Table 4, we now turn to the absolute values of the coefficients of interaction terms presented in column (4). The absolute value of the coefficient of After disaster × Trust × Damaged is 0.36, while that of After disaster × Damaged is 1.30. These observations can be interpreted as follows. Compared with other areas after the disaster, the happiness level of residents in the damaged area is 1.30 points smaller when the effect of trust is not considered. The value of the coefficient of Income is 0.014 even though it was not reported in Table 4. That is, it requires around 93 million yen (US $1.2 million) to compensate for the negative effect of the psychological damage caused by the disaster, which is considered to be gigantic. However, as mentioned earlier, it should be noted that the estimated amount of compensation might have been overestimated because of the endogeneity bias in the income coefficient (Powdthavee 2010).

An increase in trust by 1 point on the 5-point Likert scale leads to an increase in happiness by 0.36 points. This means that a 1-point increase of trust for residents of damaged areas reduces the gap of happiness levels from residents of other areas by 0.36 points. Therefore, the happiness level of residents in the damaged area is 0.22 points smaller than those in other areas if the trust level is 3. However, the happiness level of residents in the damaged area is 0.14 points larger than those in other areas if the trust level is 4. That is, the happiness level of residents in the damaged areas is possibly higher than other areas if their trust level is 4 or 5. Therefore, the effect of trust is sizable on SWB and becomes crucial as a remedy for an unpredictable, gigantic shock such as a disaster.

5 Conclusion

The outcome of unexpected terror has drawn the attention of researchers. Its psychological impact on SWB has been increasingly explored in empirical works on natural disasters (Carroll et al. 2009; Luechinger and Saschkly 2009) and terrorism (Metcalfe et al. 2011). Social trust is known to be positively associated with life satisfaction (Bjørnskov 2003). The effectiveness of social trust possibly depends on the situation. For instance, formal institutions and markets do not function well immediately after an unexpected, devastating event. In this case, trust towards others appears to become more important for avoiding chaos and turmoil. The role of social trust in the chaotic situation after a disaster is worth analyzing because distrust deteriorates the situation and in turn reduces social welfare. However, existing works do not probe how and the extent to which the relationship between trust and happiness changes after the disastrous event.

To deal with the relationship between trust and happiness after the disaster, this paper used individual-level panel data from Japan, which covered the period before and after the Great East Japan Earthquake. By employing fixed effects estimations, we found that there is a positive relationship between trust and happiness and this relationship is strengthened for residents in the damaged area. This finding implies that social trust plays a greater role in increasing happiness during a chaotic situation than in a time of peace. We therefore derived the argument that social trust is a substitute for formal institutions and markets to mitigate the shock of disaster on psychological conditions such as happiness. Therefore, trust makes communities much more resilient, more capable of cooperation during the recovery process, and consequently much more able to sustain and build happiness.

Of course, there is an endogenous bias when trust is included as an independent variable and so causality is ambiguous. Before the disaster, trust and happiness levels differed between residents in the damaged area and other areas. It is more appropriate to conduct an examination in the case that these values of residents living in the damaged area are almost the same as those of residents living in other areas before the disaster. To examine this issue in much more detail, it is important to use instrumental variables to solve the endogenous bias. This is difficult because it is hard to identify an appropriate set of instruments for people’s trust levels. Furthermore, conditions before the event should be similar between the damaged areas and other areas. Therefore, conducting experiments in similar situations before a disastrous event will be valuable (Becchetti et al. 2012). These are outstanding issues to be addressed by future research.

Notes

In some situations, crowding may produce positive emotions, but exposure to crowding has been shown to be detrimental to well-being (Novelli et al. 2013). There are myths about disasters that say collective behavior in emergencies is maladaptive, irrational, and even pathological (Drury et al. 2013a). Whether the myth is true has not been examined sufficiently. In responses to emergency situations, it is important to consider whether crowd behavior leads to mass panic or collective resilience (Drury et al. 2013a, b).

We are not the first group of economists to study the impact of natural disasters. Several economists have investigated the impact of disasters on modern society (e.g., Skidmore and Toya 2002; Anbarci et al. 2005; Eisensee and Strömberg 2007; Kellenberg and Mobarak 2008; Becchetti and Castriota 2010; Sawada and Shimizutani 2007, 2008, 2011). Some economists have noted that social capital played a crucial role in mitigating damage or recovering from the disaster (Yamamura 2010; Aldrich 2012).

Ram (2009) did not find a significant association between trust and happiness.

An unexpected catastrophe such as a terrorist attack was also found to result in higher levels of mental distress (Metcalfe et al. 2011). The suicide rate is considered an objective variable for capturing the degree of life satisfaction in society. Matsubayashi et al. (Matsubayashi et al. 2013) examined the relationship between disaster and suicide rates.

Ono (2012) pointed out that interpersonal networks are effective and play an important role in deterring rioting and turmoil in the stricken areas affected by the Great East Japan Earthquake.

A Japanese prefecture is almost the equivalent of a state in the United States or a province in Canada. There are 47 prefectures in Japan.

Sendai is regarded as the most urbanized city in northeastern Japan and has a population of over a million people.

The data are available from the website of the Statistics Bureau of the Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications. http://www.e-stat.go.jp/SG1/estat/NewList.do?tid=000000090001 (accessed on June 9, 2014).

In preparation for events such as mass decontamination, it is important to facilitate clear communication with members of the public (Carter et al. 2013).

The GCOE data provide information about the name of the prefecture and the size of the local government where the respondents resided. A prefecture consists of local governments, including many cities, towns, and villages.

It should be noted that this paper checks only the correlation between trust and happiness although there seems to be reverse causality and therefore endogenous bias. The instrumental variables must be used to control for this bias (Kuroki 2011). However, this is beyond the scope of this paper because the appropriate instruments cannot be obtained.

Evaluation in US dollars is calculated based on the average foreign exchange rate in 2011. This method was also applied in the other parts to evaluate the effect of trust.

Analysis using US data found that life events such as being widowed or marital separation would make it necessary to provide an individual with US $100,000 extra per annum (Blanchflower and Oswald 2004:1373).

In monetary terms, approximately US $300,000 compensates for the gap in happiness between married and unmarried people, which is equivalent to the UK (Powdthavee Powdthavee 2010:88).

References

Aldrich, D. P. (2012). Building resilience: Social capital in post-disaster recovery. Chicago: University Chicago Press.

Anbarci, N., Escaleras, M., & Register, C. (2005). Earthquake fatalities: The interaction nature and political economy. Journal of Public Economics, 89(9–10), 1907–1933.

Becchetti, L., & Castriota, S. (2010). The effects of a calamity on income and wellbeing of poor microfinance borrowers: The case of the 2004 tsunami shock. Journal of Development Studies, 46(2), 211–233.

Becchetti, L., Castriota, S., & Conzo, P. (2012). Calamity, aid and indirect reciprocity: The long run impact of tsunami. CEIS Tor Vergata University, Research Paper no. 239.

Bjørnskov, C. (2003). The happy few: Cross-country evidence on social capital and life satisfaction. Kyklos, 56(1), 3–16.

Bjørnskov, C. (2006). The multiple facets of social capital. European Journal of Political Economy, 22(1), 22–40.

Blanchflower, D. G., & Oswald, A. (2004). Well-Being over time in Britain and the USA. Journal of Public Economics, 88(7–8), 1359–1386.

Carroll, N., Frijters, P., & Shields, M. (2009). Quantifying the costs of drought: New evidence from life satisfaction data. Journal of Population Economics, 22(2), 445–461.

Carter, H., Drury, J., Rubin, J., Williams, R., & Amlot, R. (2013). Communication during mass casualty decontamination: Highlighting the gaps. International Journal of Emergency Services, 2(1), 29–48.

Clark, A., Diener, E., Georgellis, Y., & Lucas, R. E. (2008). Lags and leads in life satisfaction: A test of the baseline hypothesis. The Economic Journal, 118(529), F222–F2243.

Clark, A., & Oswald, A. (1996). Satisfaction and comparison income. Journal of Public Economics, 61(3), 359–381.

Daily Yomiuri. (2011a). 2000 missing in 2 towns: Magnitude of Friday’s quake revised upward to 9.0. March 14, 2011. Daily Yomiuri.

Daily Yomiuri. (2011b). Tsunami topped 15 meters on Sanriku coast. Daily Yomiuri. March 19, 2011.

Deshmukh, Y. (2009). The “hikmah” of peace and the PWI. Impact of natural disasters on the QOL in conflict-prone areas: A study of the Tsunami-hit transitional societies of Aceh (Indonesia) and Jaffna (Sri Lanka). Florence, ISQOLS World Congress.

Drury, J., Novelli, D., & Stott, C. (2013a). Psychological disaster myths in the perception and management of mass emergencies. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 43(11), 2259–2270.

Drury, J., Novelli, D., & Stott, C. (2013b). Representing crowd behavior in emergency planning guidance: ‘mass panic’ or collective resilience? Resilience: International Policies. Practices and Discourses, 1(1), 18–37.

Eisensee, T., & Strömberg, D. (2007). News droughts, news floods, and U.S. disaster relief. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 122(2), 693–728.

Frijters, P., Johnston, D. W., & Shields, M. A. (2011). Life satisfaction dynamics with quarterly life event data. Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 113(1), 190–211.

Goebel, J., Krekel, C., Tiefenbach, T., & Ziebarth, N. R. (2013). Natural disaster, policy action, and mental well-being: the case of Fukushima. IZA Discussion Papers no. 7691.

Hammer, J. (2011). Inside the danger zone. April 11, 2011. Newsweek, pp. 28–31.

Hanaoka, C., Shigeoka, H., & Watanabe, Y. (2014). Do risk preferences change? Evidence from panel data before and after the great east Japan earthquake. Mimeo.

Helliwell, J. F. (2003). How’s life? Combining individual and national variables to explain subjective well-being. Economic Modelling, 20(2), 331–360.

Helliwell, J. F. (2006a). Well-Being and social capital: Does suicide pose a puzzle? Social Indicator Research, 81(3), 455–496.

Helliwell, J. F. (2006b). Well-being, social capital and public policy: What’s new? The Economic Journal, 116(510), C34–C45.

Helliwell, J. F. (2011). How can subjective well-being be improved? In F. Gorbet & A. Sharpe (Eds.), New directions for intelligent government in Canada (pp. 283–304). Centre for the Study of Living Standards: Ottawa.

Helliwell, J. F., Huang, H., & Wang, S. (2014). Social capital and well-being in time of crisis. Journal of Happiness Studies, 15, 145–162.

Helliwell, J. F., & Wang, S. (2011). Trust and well-being. International Journal of Well-being, 1(1), 42–78.

Ishino, T., Ogaki, M., Kamesaka, A., & Murai, S. (2011). Effect of the great East Japan disaster on happiness. Keio/Kyoto Global COE Discussion Paper Series, DP2011-38.

Kawachi, I. (2013). Can we reduce disparity of life? Inochi no Kakusa wa Tomerareruka. Tokyo: Shogakkan Press. (in Japanese).

Kawachi, I., Kennedy, B. P., Lochner, K., & Glass, R. (1999). Social capital and self-related health: A contextual analysis. American Journal of Public Health, 89(9), 1187–1193.

Kawachi, I., Kennedy, B. P., Lochner, K., & Prothrow-stith, D. (1997). Social capital, income inequality, and mortality. American Journal of Public Health, 87(9), 1491–1498.

Kawachi, I., Subramanian, S. V., & Kim, D. (Eds.). (2007). Social capital and health. New York: Springer.

Kellenberg, D. K., & Mobarak, A. M. (2008). Does rising income increase or decrease damage risk from natural disasters? Journal of Urban Economics, 63(3), 788–802.

Kuroki, M. (2011). Does social trust increase individual happiness in Japan? Japanese Economic Review, 62(4), 444–459.

Kusago, T. (2011). A sustainable well-being initiative: Social divisions and the recovery process in Minamata, Japan. Community Quality of Life Indicators: Best Cases, 3, 97–111.

Luechinger, S., & Saschkly, P. A. (2009). Valuing flood disasters using the life satisfaction approach. Journal of Public Economics, 93(3–4), 620–633.

Matsubayashi, T., Sawada, Y., & Ueda, M. (2013). Natural disasters and suicide: Evidence from Japan. Social Science & Medicine, 82, 126–133.

Matsutani, M. (2011). Volunteering with three teens in Tohoku. July 17, 2011. The Japan Times.

Metcalfe, R., Powdthavee, N., & Dolan, P. (2011). Destruction and distress: Using a quasi-experiment to show the effects of the September 11 attacks on mental well-being in the United Kingdom. The Economic Journal, 121(550), F81–F103.

National Police Agency. (2014). The damage of the Great East Japan Earthquake (Higashi Nihon Daishinsai no Higaijokyo) (in Japanese). Accessed on June 15, 2014, from http://www.npa.go.jp/archive/keibi/biki/higaijokyo.pdf

Novelli, D., Drury, J., Reicher, S., & Stott, C. (2013). Crowdedness mediates the effect of social identification on positive emotion in a crowd: A survey of two crowd events. PLoS ONE, 8(11), 1.

Ono, H. (2012). The reason that disturbance does not arise after the disaster in Japan: Consideration from the angle of network theory (in Japanese) (Nihon dewa naze shinsaigo ni bodo ga okinai noka: netwaork riron karano ichi-kosatsu). Keizai Seminar, 2–3, 75–79.

Oswald, A., & Powdthavee, N. (2008). Death, happiness, and the calculation of compensatory damages. Journal of Legal Studies, 37(S2), S217–S252.

Powdthavee, N. (2008). Putting a price tag on friends, relatives and neighbours: Using surveys of life satisfaction to value social relations. Journal of Socio-Economics, 37(4), 1459–1480.

Powdthavee, N. (2010). The happiness equation: The surprising economics of our most valuable asset. London: Icon Books.

Putnam, R. (1993). Making democracy work: Civic traditions in modern Italy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Putnam, R. (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. New York: A Touchstone Book.

Ram, R. (2009). Social capital and happiness: Additional cross-country evidence. Journal of Happiness Studies, 11(4), 409–418.

Sawada, Y., & Shimizutani, S. (2007). Consumption insurance against natural disasters: Evidence from the Great Hanshin-Awaji (Kobe) earthquake. Applied Economics Letters, 14(4), 303–306.

Sawada, Y., & Shimizutani, S. (2008). How do people cope with natural disasters? Evidence from the Great Hanshin-Awaji (Kobe) Earthquake in 1995. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 40(2–3), 463–488.

Sawada, Y., & Shimizutani, S. (2011). Changes in durable stocks, portfolio allocation, and consumption expenditure in the aftermath of the Kobe Earthquake. Review of Economics of the Household, 9(4), 429–443.

Skidmore, M., & Toya, H. (2002). Do natural disasters promote long-run growth? Economic Inquiry, 40(4), 664–687.

Tanikawa, H., Managi, S., & Lwin, C. M. (2014). Estimates of lost material stock of buildings and roads due to the Great East Japan Earthquake and tsunami. Journal of Industrial Ecology, 18(2), 421–431.

Toya, H., & Skidmore, M. (2012). Do natural disasters enhance societal trust? CESifo Working Papers, no. 3905.

Uchida, Y., Takahashi, Y., & Kawahara, K. (2014). Changes in hedonic and eudaimonic well-being after a severe nationwide disaster: The case of the Great East Japan Earthquake. Journal of Happiness Studies, 15(1), 207–221.

Yamamura, E. (2010). Effects of interactions among social capital, income and learning from experiences of natural disasters: A case study from Japan. Regional Studies, 44(8), 1019–1032.

Yamamura, E. (2014). Natural disasters and social capital formation: The impact of the Great Hanshin-Awaji earthquake. Papers in Regional Science (forthcoming).

Acknowledgments

This research uses microdata from the Preference Parameters Study of Osaka University’s twenty-first Century GCOE program, Behavioral Macrodynamics based on Surveys and Experiments, and its GCOE project, Human Behavior and Socioeconomic Dynamics. We acknowledge the contribution from the program and project contributors: Yoshiro Tsutsui, Fumio Ohtake, and Shinsuke Ikeda. The first author gratefully acknowledges financial support in the form of research grants from the Japan Center for Economic Research as well as the Japanese Society for the Promotion of Science (Foundation C 20368971). The first author also wishes to acknowledge the financial support of the Kikawada Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yamamura, E., Tsutsui, Y., Yamane, C. et al. Trust and Happiness: Comparative Study Before and After the Great East Japan Earthquake. Soc Indic Res 123, 919–935 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-014-0767-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-014-0767-7