Abstract

The main aim of our research was to describe the comprehensive picture of relationships between identity and well-being with a cross-national perspective. We examined identity considering the interplay of three processes (i.e., commitment, in-depth exploration, and reconsideration of commitment) and we treated well-being as a multidimensional latent variable, whose indicators were subjective well-being, psychological well-being, and social well-being. Participants were 1,086 (60.6 % female) emerging adults from Italy, Poland, and Romania. They completed self-report measures of identity and well-being. We adopted a structural equation modeling approach and we tested associations between identity and well-being for university students (taking into account educational identity) and working emerging adults (considering job identity). For all countries and in both identity domains findings indicated that well-being was consistently associated with high commitment, high in-depth exploration, and low reconsideration of commitment. Implications of these findings are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Along the entire life span identity formation is a core developmental task (Erikson 1950, 1968). Achievement of a firm identity in multiple life domains (e.g., education, work, relationships) leads to stability, security, and therefore lower distress (e.g., Crocetti et al. 2012). Up to now, most research on identity and adjustment has analyzed how identity is related to the absence of well-being, unraveling interrelations between identity and anxiety and depression (for a review, see Kroger and Marcia 2011). In contrast, there is a dearth of studies on how identity is related to positive well-being, such as satisfaction with life (Diener 1984), psychological (Ryff 1989), and social well-being (Keyes 1998).

Thus, in the present study we addressed this shortcoming of the identity literature by examining links between identity processes and a multidimensional conceptualization of well-being. We sought to shed light on these associations in youth from different nations (i.e., Italy, Poland, and Romania). We also paid attention, in each country, to youth from two different groups, university students and young workers, analyzing the identity domain that is related to their societal definition: educational and job identity, respectively.

1.1 Identity

Erikson (1950, 1968) considered development as a series of conflicts individuals face, identity formation being the most prominent task of adolescence, closely linked to future psychosocial development. Marcia (1980) extended Erikson’s psychosocial theory and defined identity as a self-structure, comprised of human drives, ideology, abilities, and life history. Moreover, Marcia (1966) described two key processes for identity formation: exploration and commitment. Exploration is the process of questioning and weighing identity alternatives before making decisions about the values, beliefs, and goals one will pursue. Commitment involves making a relatively firm choice about an identity domain, such as ideology or occupation, and engaging in significant activities geared toward the implementation of that choice. Based on these two dimensions, Marcia (1966) distinguished four identity statuses: achievement (a commitment is made after active exploration), foreclosure (a commitment is made with no prior exploration), moratorium (alternatives are actively explored, though no commitment has been made yet), and diffusion (no engagement in either exploration or commitment).

In the last decade, various extensions of Marcia’s identity status paradigm were proposed (for a review, see Meeus 2011). In particular, Luyckx et al. (2006, 2008) and Meeus, Crocetti and collaborators (Crocetti, Rubini, and Meeus 2008, Meeus et al. 2010) proposed process-oriented models of identity formation. The former model (Luyckx et al. 2008) includes commitment making, identification with commitment, and three processes of exploration (in-breadth, in-depth exploration, and ruminative exploration). The latter model (Crocetti, Rubini, and Meeus 2008b) integrates commitment, in-depth exploration, and reconsideration of commitment. Both models were able not only to individuate the identity statuses originally described by Marcia (1966), but also to differentiate further identity statuses (Crocetti et al. 2008; Crocetti et al. 2012; Luyckx et al. 2005, 2008). A main difference between the two models refers to the domains taken into account. In particular, Luyckx et al.’s (2008) integrative model was used to evaluate identity related to general future plans. The Meeus, Crocetti et al.’s model (Crocetti et al. 2008; Meeus et al. 2010) was employed in studying how individuals deal with identity domains that are relevant for their present experience (e.g., education, work, relationships).

Given this main difference and considering the purpose of our study, we adopted the three-factor model proposed by Meeus et al. (Crocetti et al. 2008; Meeus et al. 2010) as the framework of our investigation. In fact, this model, detailed below, pays attention to identity formation in specific identity domains. Thus, by applying this model, we could focus on the domain of interest for the current research, which is the societal realm. We selected this domain for its key importance for emerging adults, who have to find out which is the role they want to play in society (Arnett 2004). Specifically, we evaluated educational identity for university students and job identity for young workers.

1.2 The Three-Factor Identity Model

This model focuses on the dynamics of identity development throughout time (Crocetti et al. 2008a, b). Three pivotal processes are taken into account. Commitment refers to the choice made in an identity-relevant area and the extent to which one identifies with this choice. In-depth exploration refers to the extent to which one actively deals with commitments, reflects on taken choices, looks for new information, and talks to others about these commitments. Reconsideration of commitment is the comparison between current commitments and other possible alternatives and efforts to change no longer satisfactory commitments. Thus, this approach emphasizes that young people may actively revise and change their commitments.

Moreover, research revealed that these three processes are associated with people’s self-views, personality traits, and relations to others (Meeus 2011). Commitment was found to be a strong predictor of identity consolidation and was linked to a stable self-concept, extroversion, emotional stability, and warm relations with parents (Crocetti et al. 2008, 2010). In-depth exploration appeared to be a double-edged sword. On the one hand, it was negatively linked to self-concept clarity and emotional stability and positively related to problematic behaviors; on the other hand, it was found to be an adaptive process, being positively related to agreeableness, conscientiousness, and openness to experience (Crocetti et al. 2008, 2010). A recent research (Crocetti et al. 2012) further revealed the bright side of in-depth exploration underscoring that active exploration of current commitments is associated with civic engagement through the mediation of social responsibility. Reconsideration of commitment unequivocally represented the crisis-like process of identity formation. It was negatively associated with agreeableness, conscientiousness, and openness to experience; it was linked to poor family relationships and positively associated with problem behaviors (Crocetti et al. 2008, 2010). Therefore, releasing one’s commitments appears to be intertwined with disequilibrium and distress.

Until now, research on identity and well-being has mainly conceptualized well-being as the absence of anxiety and depressive symptoms (cf. Meeus et al. 1999). Findings have consistently showed that commitment is associated with low anxiety and depression (e.g., Crocetti et al. 2008, 2010, 2009; Luyckx et al. 2006); whereas in-depth exploration (Crocetti et al. 2008, 2010) but especially reconsideration of commitment (Crocetti et al. 2008, 2009, 2010) are associated with internalizing problem behaviors.

However, as the Positive Psychology movement (cf. Seligman 2002; Snyder and Lopez 2002) emphasized, adjustment cannot be merely identified with lack of illness. It also implies a condition of positive well-being and adaptive functioning in the psychological (cf. Ryff 1989) and social domains (Keyes 1998). Therefore, in the present study we unraveled associations between identity processes and positive dimensions of well-being.

1.3 The Multidimensionality of Well-Being

One of the possible differentiations in understanding the construct of well-being refers to two philosophical conceptualizations: hedonic and eudaimonic well-being (for a detailed review, see Ryan and Deci 2001). The former focuses on the attainment of pleasure and avoidance of pain in various aspects of life; high levels of well-being involve increased satisfaction with life and a predominance of positive affect (Diener and Lucas 1999). The latter is organized by the concept of human flourishing, focusing on the development of people’s true potentials; the fulfillment of these potentials leads to high life quality (Ryff 1989, 1995). According to Waterman et al. (2010), the successful coping with identity issues is the resolution that brings one to identification and development of his or her best potentials. Developing those potentials leads to the sense of eudaimonic well-being. Additionally, the social context was also explicitly introduced in the well-being dynamics, in an attempt to capture individual functioning in the society (Keyes 1998). In line with this multidimensional conceptualization (cf. Keyes and Waterman 2003), in this study we considered three dimensions of well-being: subjective (which may be considered as an aspect of hedonic well-being), psychological (eudaimonic facet of well-being), and social well-being. Our choice is based on Keyes’s (2006) argumentation that well-being should be treated as a multidimensional concept. Moreover, as Keyes (2005) argues, well-being can be treated as one latent variable, and Gallagher, Lopez, and Preacher (Gallagher et al. 2009) provided empirical support for this assumption.

Subjective well-being (Diener 1984) refers to people’s evaluation of their own lives, based on general life satisfaction and a sense of fulfillment, but also on the evaluation of various life domains (e.g., marriage, work), and positive or negative emotions (e.g., experience of joy, due to positive assessment of personal experiences). Hence, subjective well-being includes three main components (Diener 1984): positive affect, negative affect, and life satisfaction. In our study, we focused on the aspect of life satisfaction, which refers to the global assessment of a person’s quality of life according to his/her own chosen criteria and standards (Diener 1984; Diener et al. 2003).

Based on Jahoda’s (1958) assumption that health is more than the absence of illness, Ryff (1989) proposed the concept of psychological well-being. According to Ryff’s (1989) conceptualization, six aspects lead to high levels of psychological well-being: self-acceptance (it reflects a positive attitude toward oneself, with integration of personal strengths and limitations), positive relations with others (they refer to warm, trusting interpersonal relations, marked by empathy and love), autonomy (it refers to independence and internal regulation of behavior), environmental mastery (it is the individual’s ability to choose or create an environment suitable for one’s psychical conditions, sense of agency, and competence), and purpose in life (it includes a clear view of one’s life aims and direction), personal growth (it encompasses the need to develop one’s potential, reflecting optimal psychological functioning). These core dimensions jointly contribute to human flourishing (Ryff and Singer 2008).

Keyes (1998) integrated the social context in the conceptualization of well-being, by proposing five main dimensions which define social well-being. They encompass: social integration in one’s community, social acceptance of other people, social contribution brought by oneself to society, social actualization in terms of trust in society’s potential, and social coherence as perceived meaningfulness of the social world. In the terms of Keyes’s theory (Keyes 1998), the essence of social well-being is the evaluation of one’s situation and functioning in society, with social challenges as criteria that people use to assess the quality of their lives.

1.4 Emerging Adulthood in Italy, Poland, and Romania

Although research on identity formation mainly focuses on adolescence, it now seems clear that identity development continues also in the late teens and twenties, when young people make important decisions in several life domains (Arnett 2000; Luyckx et al. 2006). The present research focused on an analysis of the relations between identity formation and well-being in emerging adults.

Emerging adulthood spans from the late teens through the twenties (Arnett 2000). It is a developmental time-frame characterized by instability, extensive self-focus, and feeling in-between adolescence and adulthood. It is also the age of great possibilities for personal development and experimentation with new life contexts and life roles (Arnett 2004, 2007). During this period identity issues are crucial (Schwartz et al. 2005), as the perceived instability and increased exploration always involve identity relevant pursuits. These pursuits are not always experienced as enjoyable and sometimes they tend to be associated with decreases in personal well-being (Arnett 2000). Hence, an in-depth examination of the links between identity processes and well-being can shed light on the perceived life quality of emerging adults.

A priority in scholars’ agenda is the understanding of life quality in two groups of emerging adults: university students and young workers. Up to now, most research on young adulthood has mainly relied on university samples, leading to the definition of youth who enter the labor market as a “forgotten half that remains forgotten” (Arnett 2000, p. 476). Given this shortcoming of the literature, in the current study we sought to unravel links between identity and well-being both in university students and young workers, considering for each group the identity domain that is related to their societal definition: educational and job identity, respectively.

Furthermore, interest for international perspectives in identity has received a sharp increase in the last years (e.g., Berman 2011; Schwartz et al. 2012). In this respect, more studies are needed to disentangle whether the pattern of associations between identity and relevant correlates is comparable across various national contexts (Crocetti et al. 2010). In the current study we addressed this issue by examining associations between identity processes and well-being in youth from a Southern European country (i.e., Italy) and two Eastern European countries (i.e., Poland and Romania).

In each of these countries emerging adulthood appears to be the critical time for identity formation. The socio-economical situation particularly contributes to the postponement of important life commitments and the transition into adulthood (Crocetti et al. 2012; Schwartz et al. 2013). It also contributes to the elongation of exploration processes, and often to the disappointment with chosen educational and occupational paths. This dynamics undoubtedly has a great impact on personal well-being.

In Italy, sociological and demographic analyses have highlighted the presence of what has been named a “delay syndrome” (Livi Bacci 2008). This syndrome is characterized by five symptoms: prolongation of education; deferral of entry into the job market combined with high rates of unemployment and low activity rates; tendency to remain in the parental home until the late 20s or 30s; postponement of entry into a committed partnership; and delayed transition to parenthood. This delay syndrome has a strong impact on young people’s lives, by increasing identity instability in adolescence and configuring emerging adulthood as a period for engaging in exploration of identity alternatives (Crocetti et al. 2012). Identity uncertainty and perception of limited external opportunities due to low employment rates might decrease the well-being of Italian emerging adults.

In Poland and Romania access to tertiary education was very limited until the fall of the communist regimes in 1989. As summarized in Table 1, EUROSTAT data (2012) indicate an upsurge in the young population attending university in the last decade, and a massive increase in youth aged 20–24 who graduate from university. This is doubled though by a significant decrease in university graduate employment, especially from 2008 to 2011, with the sharpest trend being observed for Romania (from 84.8 % employment rate in 2008 to 70.1 % in 2011).

The resurgence of higher education in Poland and Romania in the last 20 years can be linked to several factors (Muller and Kogan 2010). On the one hand, global labor market dynamics require high-level, specialized training, which requires extensive schooling. On the other hand, limited access to university studies before 1989 conveyed this type of education a high perceived social status. Also, the structure of secondary education does not fully prepare youth for entering the labor market after high-school graduation and makes further schooling a necessity (Education, Audiovisual and Culture Executive Agency—a P9 Eurydice 2012). Additionally, the unstable socio-economic context conveys university the role of a safe and protective environment for youth development, postponing the transition into adulthood. Most university students are enrolled in full-time programs, are not employed during their studies, and are financially sustained by their families (European Commission, Economic Policy Committee, Quality of Public Finances and the Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs 2010). These factors make emerging adulthood a time of extended identity exploration, in which financial and social responsibilities and pressures are reduced.

Besides overall educational and socio-economic characteristics of Italy, Poland, and Romania, it is also worthwhile considering cultural systems common in these countries. According to Hofstede’s (2001) conceptualization, culture could not exist without comparisons. Hofstede’s categorization of country cultures is based on value preferences. Hofstede proposed six dimensions describing culture (Hofstede 2001; Hofstede et al. 2010): power distance, individualism, masculinity, uncertainty avoidance, pragmatism, and indulgence. According to data presented by Hofstede et al. (2010), Poland, Italy, and Romania can be considered similar in some of Hofstede’s dimensions (e.g., indulgence, uncertainty avoidance, and pragmatism), but different in others (e.g., in the power distance index, Romania scored higher than Poland and Italy, but lower in individualism and masculinity).

1.5 The Current Study

The purpose of this study was to describe the dynamics of relationships between identity and well-being. We examined identity considering the interplay of three processes: commitment, in-depth exploration, and reconsideration of commitment (Crocetti et al. 2008) and, in line with Positive Psychology theory (Seligman 2002; Snyder and Lopez 2002), we treated well-being as a multidimensional latent variable, whose indicators are subjective (Diener et al. 1985), psychological (Ryff 1989), and social (Keyes 1998) well-being. We sought to unravel connections between identity and well-being for university students (taking into account educational identity) and working emerging adults (taking into account job identity), from three different countries: Italy, Poland, and Romania.

We hypothesized that identity processes would be significantly related to positive well-being. First, we expected that a high level of commitment, a dimension positively related to an adaptive personality profile, would lead to increased well-being. Second, a low level of reconsideration, a problematic aspect of identity formation, connected with uncertainty about present commitments and problematic behaviors, should contribute to increased well-being. Since extant results are straightforward in showing that commitment and reconsideration of commitment function as opposite forces, with commitment leading to identity synthesis and reconsideration to identity confusion (Meeus, 2011), we expected that the hypothesized pattern of relationships between these processes and well-being would emerge similarly across nations and occupational groups (i.e., university students and young workers).

Third, in light of findings pointing out the bright side of in-depth exploration (Crocetti et al. 2008, 2010, 2012) we hypothesized that the role of this process for increased well-being would also be positive. As in-depth exploration was positively linked to volunteering and political participation through the mediation of social responsibility and also to agreeableness, conscientiousness, and openness to experience, we expected that for the emerging adults in our study this identity process would be associated with increased well-being. We expected that this pattern of results would emerge in all national contexts under investigation, both for university students and workers.

2 Methods

2.1 Participants and Procedure

The participants were 1,086 (60.6 % females) young adults from three countries: Italy (N = 365; 49 % females, M age = 21.04, SD age = 1.73); Poland (N = 404; 78 % females, M age = 21.76, SD age = 1.78); and Romania (N = 317; 52 % females, M age = 22.2, SD age = 1.72). In each national sample, there was a balance of university students and employed participants (i.e., Italian sample: 42.2 % of participants were students and 57.8 % were employed; Polish sample: 51 % of the respondents were students and 49 % employed; Romanian sample: 53 % of the participants were students and 47 % employed). University students enrolled in various courses (e.g., finance and management, psychology, computer studies, law, humanities, arts) were contacted in university buildings and workers were contacted in various work contexts (e.g., factories, offices, etc.) by a researcher or a researcher’s assistant. They were informed about the research, and asked if they wished to participate in it. The researchers obtained permission for conducting the research from university teachers and students and, at the workplaces, from workers. Participants completed the study measures as an anonymous self-report questionnaire. Cases of refusal to participate in the study were sparse (<5 %).

2.2 Measures

2.2.1 Identity

We used the Utrecht-Management of Identity Commitments Scale (U-MICS; Crocetti et al. 2008). The U-MICS consists of 13 items with the following response options: 1—completely untrue, 2—untrue, 3—sometimes true/sometimes not, 4—true, 5—completely true. The U-MICS was specified for educational identity in the university student sample and job identity in the worker sample. Items assess three factors: commitment (5 items; e.g., “My education/work gives me security in life”), in-depth exploration (5 items; e.g., “I try to find out a lot about my education/work”), and reconsideration of commitment (3 items; e.g., “I often think it would be better to try to find a different education/work”).

2.2.2 Well-being

In this study, well-being was treated as an endogenous latent variable with the following indicators: satisfaction with life, psychological well-being, and social well-being.

The Satisfaction With Life Scale (SWLS; Diener et al. 1985) focuses on assessment of global life satisfaction. The SWLS is composed of five items, rated on a 5-point scale. The response options were: 1—strongly disagree, 2—disagree, 3—neither agree nor disagree, 4—agree, 5—strongly agree. Sample items are: “In most ways my life is close to my ideal”; “So far I have gotten the important things I want in life”.

The brief version of Psychological Well-Being Scale (PWB; Ryff and Keyes 1995) is an 18-item questionnaire composed of six 3-item subscales that assess the dimensions of psychological well-being (Ryff 1989): autonomy (e.g., “I have confidence in my opinions, even if they are contrary to the general consensus”), environmental mastery (e.g., “I am quite good at managing the many responsibilities of my daily life”), personal growth (e.g., “I think it is important to have new experiences that challenge how you think about yourself and the world”), positive relations with others (e.g., “People would describe me as a giving person, willing to share my time with others”), purpose in life (e.g., “I have a sense of direction and purpose in life”), and self-acceptance (e.g., “I like most aspects of my personality”). The response scale was a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree)—the same as in SWLS. In this study we used the general score from the questionnaire.

The Social Well-Being Scale (SWB; Keyes 1998) is a 35-item scale, consisting of five sub-scales: social integration (e.g., “You feel like you’re an important part of your community”), social acceptance (e.g., “You believe that people are kind”), social contribution (e.g., “You think you have something valuable to give to the world”), social actualization (e.g., “You think the world is becoming a better place for everyone”), and social coherence (e.g., “You think it’s worthwhile to understand the world you live in”). Response options span from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), the same as in SWLS and PWB. A general score from the questionnaire was employed in this study.

All measures applied in presented study are available on request from first author of this article.

3 Results

3.1 Preliminary Results

As a preliminary step, we examined bivariate correlations between identity processes and well-being. Results (see Table 2) indicated that commitment and in-depth exploration were positively related to well-being, while reconsideration of commitment was negatively linked to well-being across samples and occupational groups.

3.2 Establishment of Measurement Invariance

According to cross-national research requirements (e.g., Davidov et al. 2014), before verifying the main study hypotheses, we tested measurement invariance of the identity and well-being measurement models across the Italian, Polish, and Romanian samples. We performed multigroup Confirmatory Factor Analyses (CFA) in AMOS 20.0. We sought to establish metric invariance, since it is required for examining associations among variables across different national groups (Vandenberg and Lance 2000).

In order to reach this aim, we first tested configural invariance, which requires that the same number of factors and pattern (or configuration) of fixed and freely estimated parameters hold across groups. Second, we tested metric invariance, which entails equivalence of factor loadings and indicates that respondents across groups attribute the same meaning to the latent construct of interest. We compared the configural and metric invariance models relying on the criteria proposed by Chen (2007), according to which metric noninvariance is indicated by a model difference larger than −.010 in Comparative Fit Index (CFI), supplemented by a change larger than .015 in Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA).

For the identity measurement model, we tested for both educational and occupational identity, a model with three latent variables: identity commitment (with five observed indicators), in-depth exploration (with five observed indicators), and reconsideration of commitment (with three observed indicators). In line with results of the validation study of the U-MICS across countries (Crocetti and Meeus 2014) correlations between three pairs of error terms (U-MICS1 and U-MICS4; U-MICS4 and U-MICS5; and U-MICS9 and U-MICS10) were allowed. For the well-being measurement model, we tested a model with three latent variables: satisfaction with life (with five observed indicators), psychological well-being (with observed indicators created using parceling), and social well-being (the same as in PWB).

Results of model comparisons are reported in Table 3. As can be seen, metric invariance was established both for identity (educational and occupational) and well-being. Taken together, these results allowed us to carry out the comparisons for the relations between identity dimensions and well-being across the Italian, Polish, and Romanian sample.

Using the results of metric invariant models, we computed composite reliabilities, using the formula ρc = (Σλ1) 2/[(Σλ1) 2 + (Σε1)] (Bagozzi 1994, p. 324), where ρc is the composite reliability, λ the factor loadings, and ε the error variance. Results, as well as average variance of the latent factors, are reported in Table 4.

3.3 Path Analytic Model

The main aim of this study was to describe the complete picture of relationships between the three identity dimensions (commitment, in-depth exploration, and reconsideration of commitment) and well-being. To examine these relationships we used structural equation modeling in AMOS 20.0 program. We tested two models, one for students and one for young workers. In these models identity dimensions were treated as exogenous latent variables explaining overall well-being.

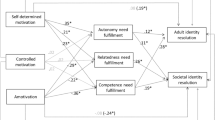

In Fig. 1, we present the model and results for the whole sample (separately for educational and occupational identity): factor loadings, correlations between latent factors, path coefficients, and percentage of explained well-being variance. For the model with educational identity the model fit coefficients were: χ2 = 730.77, df = 95, CFI = .919, RMSEA (90 % CI) = .077 (.072–.082). For the model with occupational identity the model fit coefficients were: χ2 = 871.91, df = 95, CFI = .920, RMSEA (90 % CI) = .085 (.080–.090). Thus, both models fit the data adequately. Results indicated that for both educational and occupational identity commitment and in-depth exploration were positively related to well-being, whereas reconsideration of commitment was negatively linked to well-being. All these paths were statistically significant, with the one between commitment and well-being being the strongest.

Finally, we tested if the national context was a moderator of these relationships. Thus, we performed multigroup analysis, separately for educational and occupational domains. We compared two models: one with all coefficients unconstrained, and one with path coefficients from identity dimensions to well-being constrained to be equal across countries. According to Saris et al. (2009), χ2 could be affected by sample size, so it should not be used as the only indicator for model comparisons. In line of this consideration, we compared these models on the basis of ΔCFI and ΔRMSEA rather than Δχ2 although we report all the coefficients below.

For the educational model without path coefficients constrained, we obtained CFI = .905, RMSEA = .048, χ2 = 1042.524, df = 285. In the model with path coefficients constrained to be equal across national samples, we obtained CFI = .901, RMSEA = .049, χ2 = 1079.932, and df = 291. Thus, the ΔCFI = .004 and ΔRMSEA = .001 suggest that the equivalence of the two models.

For the occupational model without path coefficients constrained, we obtained CFI = .890, RMSEA = .059 χ2 = 1547.278, df = 285. For the model with path coefficients constrained to be equal across national samples, we obtained CFI = .891, RMSEA = .059, χ2 = 1562.136, and df = 291.The ΔCFI = .001 and ΔRMSEA = .000 indicate the equivalence of these two models. Therefore, for both educational and occupational identity, the national context was not a moderator of the relationships between identity processes and well-being.

4 Discussion

This study sought to examine linkages among three processes of identity formation (i.e., commitment, in-depth exploration, and reconsideration of commitment; Crocetti et al. 2008) and positive well-being, analyzed as a multidimensional latent variable whose indicators were subjective well-being (Diener 1984), psychological well-being (Ryff 1989), and social well-being (Keyes 1998). We provided an original contribution to the literature by: (a) focusing on positive well-being (instead of investigating links to depression and anxiety as commonly done in the identity literature; cf. Kroger and Marcia 2011); (b) considering two identity domains (i.e., educational and job identity) relevant for two distinct groups of emerging adults (i.e., university students and young workers); and (c) testing interconnections between identity and well-being in three national contexts (i.e., Italy, Poland, and Romania).

4.1 Identity as a Resource for Positive Well-Being

In this study, we found that identity processes were meaningfully related to positive well-being. In particular, commitment was positively related to well-being, whereas reconsideration of commitment was negatively linked to it. In line with the proposed hypotheses, we found that, while commitment provides a sense of security and stability that enhances well-being (Berzonsky 2003), reconsideration of commitment is a troublesome aspect of identity formation, which leads to decreased well-being (Meeus 2011).

Additionally, we also brought forward that in-depth exploration was positively associated with well-being. So, this study shed further light on the double-edged nature of in-depth exploration. As previous research revealed (Crocetti et al. 2008, 2010), in-depth exploration has both a dark side, due to its links to low self-concept clarity, depressive and anxiety symptoms, as well as a bright side, being associated with adaptive personality traits, such as agreeableness, conscientiousness, openness to experience, with an information-oriented identity style, and with civic engagement, civic efficacy, aspirations for community contributions, and social responsibility (Crocetti et al. 2012, 2009; Zimmerman et al. 2012). The current study further adds to this picture, by revealing interconnections between in-depth exploration and positive well-being. Interestingly, results showing that in-depth exploration is positively related to both negative (i.e., anxiety and depression) and positive (i.e., satisfaction with life, psychological, and social well-being) facets of well-being further confirm the distinction between mental health problems and positive dimensions of well-being. In fact, these dimensions represent distinct aspects, as properly emphasized by the Positive Psychology Movement (cf. Seligman 2002; Snyder and Lopez 2002).

4.2 Identity and Well-Being across National and Occupational Groups of Emerging Adults

In this study, we sought to further advance the literature on identity and well-being across three national (i.e., Italian, Polish, and Romanian) groups of emerging adults. Doing so, we aimed at further clarifying linkages between identity and relevant correlates from a cross-cultural perspective (Berman 2011; Schwartz et al. 2012). Interestingly, findings indicated that the national context was not a significant moderator of the associations between identity processes and positive well-being. Thus, the pattern of associations described above was consistent in the Southern and Eastern European youth samples under investigation.

Additionally, we examined the associations between identity and well-being in two occupational groups, represented by university students and young workers from the three participating countries. In this way, we sought to shed further light on identity factors related to differences in adjustment of emerging adults considering not only youth who receive university education but also those who entered the labor market after completing their high school diploma (see Arnett, 2000 for a discussion of the importance of studying this latter group). Results indicated that, in both groups, commitment and in-depth exploration were positively linked to well-being, whereas reconsideration of commitment was negatively related to it.

So, the overall pattern of associations was consistent across the two occupational groups. However, it is worth noting that the percentage of variance of well-being explained by identity processes was larger in the university student group (29 vs. 14 %). This difference is due to the fact that the association between commitment and well-being was stronger in the student sample (see Fig. 1). This finding is consistent with a prior study (Crocetti et al. 2013) that showed that educational commitment (in that case, more than interpersonal commitment) was related to multiple functions served by identity (Adams and Marshall 1996; Serafini and Adams 2002). Indeed, educational commitment was strongly related to a sense of structure with which to understand self-relevant information; to a consolidated future orientation and a sense of continuity among past, present, and future; to an organized set of goals to strive for; and to a sense of personal control, free will, or agency that enables active self-regulation in the process of setting and achieving goals, moving toward future plans, and processing experiences in ways that are self-relevant (Crocetti et al. 2013).

4.3 Limitations of the Study and Suggestions for Further Research

The present study is one of the few attempts to fully understand the links between identity formation and positive well-being in a cross-national context. However, it should also be considered in light of some limitations. First, the use of cross-sectional data does not allow predictions on the longitudinal directionality of relations between identity and well-being. Identity and well-being may reinforce each other in a reciprocal relationship. For this reason, future research into this issue should take into account a longitudinal approach to fully understand these links over time.

Second, the domain-specific approach to identity does not convey a comprehensive picture of identity processes at this age (Goossens 2001). We assessed only one identity domain in each group, whereas developing identity in one domain may not mean achieving identity in another (e.g., in the relational identity domain; Luyckx et al. 2014). Thus, future studies should consider more domains at the same time.

One more possible limitation is the fact that in our study we did not control for the effect of other factors (e.g., income level, physical health, achievements), which could be relevant predictors of well-being. In further research these factors should be examined together with identity in order to highlight the unique contribution provided by identity resources.

The last limitation concerns the fact that country comparisons should be considered with caution given the sizes of the participating national samples. Undoubtedly, future studies on larger samples are required.

5 Conclusion

Summing up, the results of this study highlight that creating one’s identity through firm commitments and active exploration leads to increased positive well-being. In contrast, uncertainty about current commitments, as indicated by high levels of reconsideration of commitment, is associated with decreased well-being. This pattern of relationships has been found to be consistent across national (Italian, Polish, and Romanian) and occupational (university students and young workers) groups of emerging adults. Without doubt, additional longitudinal research in other national contexts is necessary for further disentangling interconnections between identity and positive well-being.

References

Adams, G. R., & Marshall, S. (1996). A developmental social psychology of identity: Understanding the person in context. Journal of Adolescence, 19, 1–14.

Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55, 469–480.

Arnett, J. J. (2004). Emerging adulthood: The winding road from the late teens through the twenties. Oxford: University Press.

Arnett, J. J. (2007). Suffering, selfish, slackers? Myth and reality about emerging adults. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 36, 23–29.

Bagozzi, R. P. (1994). Structural equation models in marketing research: Basic principles. In R. P. Bagozzi (Ed.), Principles of marketing research (pp. 317–385). Oxford: Blackwell.

Berman, S. L. (2011). International perspectives on identity development.Child and Youth Care Forum, 40(1), 1-5.

Berzonsky, M. D. (2003). Identity style and well-being: Does commitment matter? Identity: An international Journal of Theory and Research, 3, 131–142.

Chen, F. (2007). Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling, 14, 464–504.

Crocetti, E., Jahromi, P., & Meeus, W. (2012a). Identity and civic engagement in adolescence. Journal of Adolescence, 35, 521–532.

Crocetti, E., Klimstra, T., Keijsers, L., Hale, W. W, I. I. I., & Meeus, W. (2009a). Anxiety trajectory classes and identity development in adolescence: A five-wave longitudinal study. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38, 839–849.

Crocetti, E., & Meeus, W. (2014). Identity statuses: Advantages of a person-centered approach. In K. C. McLean & M. Syed (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of identity development. New York: Oxford University Press.

Crocetti, E., Rabaglietti, E., & Sica, L. L. (2012b). Personal identity in Italy. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 138, 87–102.

Crocetti, E., Rubini, M., Berzonsky, M. D., & Meeus, W. (2009b). The identity style inventory: Validation in Italian adolescents and college students. Journal of Adolescence, 32, 425–433.

Crocetti, E., Rubini, M., Luyckx, K., & Meeus, W. (2008a). Identity formation in early and middle adolescents from various ethnic groups: From three dimensions to five statuses. Journal of Adolescence, 37, 983–996.

Crocetti, E., Rubini, M., & Meeus, W. (2008b). Capturing the dynamics of identity formation in various ethnic groups: Development and validation of three-dimensional model. Journal of Adolescence, 31, 207–222.

Crocetti, E., Schwartz, S. J., Fermani, A., Klimstra, T., & Meeus, W. (2012c). A cross-national study of identity status in Dutch and Italian adolescents: Status distributions and correlates. European Psychologist, 17, 171–181.

Crocetti, E., Schwartz, S. J., Fermani, A., & Meeus, W. (2010). The Utrecht-management of identity commitments Scale (U-MICS): Italian validation and cross-national comparisons. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 26, 172–186.

Crocetti, E., Scrignaro, M., Sica, L. S., & Magrin, M. E. (2012d). Correlates of identity configurations: Three studies with adolescent and emerging adult cohorts. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 41, 732–748.

Crocetti, E., Sica, L. S., Schwartz, S. J., Serafini, T., & Meeus, W. (2013). Identity styles, processes, statuses, and functions: Making connections among identity dimensions. European Review of Applied Psychology, 63, 1–13.

Davidov, E., Cieciuch, J., Meuleman, B., Schmidt, P., & Billiet, J. (2014). Measurement equivalence in cross-national research. Annual Review of Sociology, 40. (in press).

Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 95, 542–575.

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 71–75.

Diener, E., & Lucas, R. (1999). Personality and subjective well-being. In D. Kahneman, E. Diener, & N. Schwarz (Eds.), Well-being: The foundations of hedonic psychology (pp. 213–229). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Diener, E., Oishi, S., & Lucas, R. E. (2003). Personality, culture, and subjective well-being: Emotional and cognitive evaluations of life. Annual Review of Psychology, 54, 403–425.

Education, Audiovisual and Culture Executive Agency—P9 Eurydice. (2012). Key Data on Education in Europe 2012, available online at http://eacea.ec.europa.eu/education/eurydice/documents/key_data_series/134EN.pdf.

Erikson, E. H. (1950). Childhood and society. New York: Norton.

Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis. New York: Norton.

European Commission, Economic Policy Committee (Quality of Public Finances) and the Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs. (2010). Efficiency and effectiveness of public expenditure on tertiary education in the EU. In European Economy. Occasional Papers 2010 series, available online at http://europa.eu/epc/pdf/country_fiches_-_ecofin_final_en.pdf.

EUROSTAT. (2012). Education and training 2012 Databases, available online at http://epp.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/portal/page/portal/education/data/database.

Gallagher, M. W., Lopez, S. J., & Preacher, K. J. (2009). The hierarchical structure of well-being. Journal of Personality, 77, 1025–1049.

Goossens, L. (2001). Global versus domain-specific statuses in identity research: A comparison of two self-report measures. Journal of Adolescence, 24, 681–699.

Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviours, institutions, and organizations across nations. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G. J., & Minkov, M. (2010). Cultures and organizations: Software of the mind. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Jahoda, M. (1958). Current concepts of positive mental health. New York: Basic Books.

Keyes, C. L. M. (1998). Social well-being. Social Psychology Quarterly, 61, 121–140.

Keyes, C. L. M. (2005). Mental illness and/or mental health? Investigating axioms of the complete state model of health. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73, 539–548.

Keyes, C. L. M. (2006). Subjective well-being in mental health and human development research worldwide: An introduction. Social Indicators Research, 77, 1–10.

Keyes, C. L. M., & Waterman, M. B. (2003). Dimensions of well-being and mental health in adulthood. In M. H. Bornstein, L. Davidson, C. L. M. Keyes, & K. A. Moore (Eds.), Well-being. Positive development across the life course (pp. 477–497). London: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Kroger, J., & Marcia, J. E. (2011). The identity statuses: Origins, meanings, and interpretations. In S. J. Schwartz, K. Luyckx, & V. L. Vignoles (Eds.), Handbook of identity theory and research (pp. 31–53). New York: Springer.

Livi Bacci, M. (2008). Avanti giovani, alla riscossa [Go ahead young people, to the rescue!]. Bologna, Italy: il Mulino.

Luyckx, K., Goossens, L., & Soenens, B. (2006a). A developmental contextual perspective on identity construction in emerging adulthood: Change dynamics in commitment formation and commitment evaluation. Developmental Psychology, 42, 366–380.

Luyckx, K., Goossens, L., Soenens, B., & Beyers, W. (2006b). Unpacking commitment and exploration: Preliminary validation of an integrative model of late adolescent identity formation. Journal of Adolescence, 29, 361–378.

Luyckx, K., Goossens, L., Soenens, B., Beyers, W., & Vansteenkiste, M. (2005). Identity statuses based on four rather than two identity dimensions: Extending and refining Marcia’s paradigm. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 34, 605–618.

Luyckx, K., Schwartz, S., Berzonsky, M., Soenens, B., Vansteenkiste, M., Smits, I., et al. (2008). Capturing ruminative exploration: Extending the four dimensional model of identity formation in late adolescence. Journal of Research in Personality, 42, 58–82.

Luyckx, K., Seiffge-Krenke, I., Schwartz, S. J., Crocetti, E., & Klimstra, T. A. (2014). Identity configurations across love and work in emerging adults in romantic relationships. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 35, 192–203.

Marcia, J. E. (1966). Development and validation of ego-identity status. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 3, 551–558.

Marcia, J. E. (1980). Identity in adolescence. In J. Andelson (Ed.), Handbook of adolescent psychology. New York: Wiley.

Meeus, W. (2011). The study of adolescent identity formation 2000–2010: A review of longitudinal research. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21, 75–94.

Meeus, W., Iedema, J., Helsen, M., & Vollebergh, W. (1999). Patterns of adolescent identity development: Review of literature and longitudinal analysis. Developmental Review, 19, 419–461.

Meeus, W., Van de Schoot, R., Keijsers, L., Schwartz, S., & Branje, S. (2010). On the progression and stability of adolescent identity formation: A five-wave longitudinal study in early-to-middle and middle-to-late adolescence. Child Development, 81, 1565–1581.

Muller, W., & Kogan, I. (2010). Education. In S. Immerfall & G. Therborn (Eds.), Handbook of European societies: Social transformations in the 21st century (pp. 217–290). New York: Springer.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2001). On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 141–166.

Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 1069–1081.

Ryff, C. D. (1995). Psychological well-being in adult life. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 4, 99–104.

Ryff, C. D., & Keyes, C. L. (1995). The structure of psychological well-being revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69, 719–727.

Ryff, C. D., & Singer, B. (2008). Know thyself and become what you are: A eudaimonic approach to psychological well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9, 13–39.

Saris, W. E., Satorra, A., & van der Veld, W. (2009). Testing structural equation models or detection of misspecifications? Structural Equation Modeling, 16, 561–582.

Schwartz, S. J., Côté, J. E., & Arnett, J. J. (2005). Identity and agency in emerging adulthood. Two developmental routes in the individualization process. Youth & Society, 37, 201–229.

Schwartz, S. J., Zamboanga, B. L., Luyckx, K., Meca, A., & Ritchie, R. A. (2013). Identity in emerging adulthood: Reviewing the field and looking forward. Emerging Adulthood, 1, 96–113.

Schwartz, S. J., Zamboanga, B. L., Meca, A., & Ritchie, R. A. (2012). Identity around the world: An overview. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 138, 1–18.

Seligman, M. E. P. (2002). Authentic happiness: Using the new positive psychology to realize your potential for lasting fulfillment. New York: Free Press/Simon and Schuster.

Serafini, T. E., & Adams, G. R. (2002). Functions of identity: Scale construction and validation. Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research, 2, 361–389.

Snyder, C. R., & Lopez, S. J. (2002). Handbook of positive psychology. New York: Oxford University Press.

Vandenberg, R. J., & Lance, C. E. (2000). A review and synthesis of the measurement invariance literature: Suggestions, practices and recommendations for organizational research. Organizational Research Methods, 3, 4–69.

Waterman, A. S., Schwartz, S. J., Zamboanga, B. L., Ravert, R. D., Williams, M. K., Agoha, V. B., et al. (2010). The Questionnaire for Eudaimonic well-being: Psychometric properties, demographic comparisons, and evidence of validity. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 5, 41–61.

Zimmerman, G., Mahaim, E. B., Mantzouranis, G., Genoud, P. A., & Crocetti, E. (2012). Brief report: The identity style inventory (ISI-3) and the Utrecht-Management of Identity Commitments Scale (U-MICS)—Factor structure, reliability, and convergent validity in French-speaking university students. Journal of Adolescence, 35, 461–465.

Acknowledgments

Dominika Karaś was supported by Grants (UMO-2012/07/N/HS6/02015) from the Polish National Science Centre. Jan Cieciuch was supported by Grants (DEC-2011/01/D/HS6/04077) from the Polish National Science Centre. Oana Negru was supported by Grant PD412/2010 from the Romanian National University Research Council (CNCSIS). Elisabetta Crocetti was supported by a Marie Curie fellowship (FP7-PEOPLE-2010-IEF).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Karaś, D., Cieciuch, J., Negru, O. et al. Relationships Between Identity and Well-Being in Italian, Polish, and Romanian Emerging Adults. Soc Indic Res 121, 727–743 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-014-0668-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-014-0668-9