Abstract

The overtime changes of life satisfaction have been recognized as an important topic in happiness studies. Unfortunately, most of prior research is confined to Western industrialized countries. A few studies focused on the case of China yet fail to reach a general agreement. This research aims to synthesize multiple national representative samples implemented in China by standardizing the happiness scores. The transformation of datasets yields more observation points and grounds the analysis in much larger samples, which helps to represent a country as vast as China. The analysis shows that in the past two decades, Chinese people has been experiencing a marked decline of life satisfaction, in spite of tremendous economic and societal progress.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

A society’s level of subjective well-being is of more than merely academic interest: it is intimately related to the legitimacy of the socioeconomic and political system….in the long run, if people feel that their lives have gone well under a given regime, it helps endow those institutions with legitimacy. But conversely, if subjective well-being of an entire society falls shapely below its normal baseline, it can destabilize the entire sociopolitical order.

By Inglehart and Klingemann (2000)

1 Background of Research

These days, ‘happiness’Footnote 1 is one of the most topical research subjects in social science and is attracting attentions from a variety of academic disciplines, particularly psychology, economics, sociology, philosophy and political science. As the title of Layard’s (2005) popular book denotes, a new science of happiness has already emerged. Moreover, consistent with the rapid progress in happiness studies within academic circles, the topic has also become a popular one for government policy-makers around the world. With general agreement that ‘quality of life’ cannot simply be equated with GDP and other economic performance indicators, an increasing number of governments (for example, Bhutan, France, Britain and Canada) have committed themselves to measuring happiness and life satisfaction of their people to provide supplementary measures of social progress (Dolan et al. 2011; Helliwell et al. 2012; Stiglitz et al. 2009).

The popularity of the concept of happiness in both theoretical and practical senses can be partially attributed to the groundbreaking work of psychologists, and, to a lesser extent, sociologists and economists. Nevertheless, their vigorous efforts have resulted in happiness now being considered as a measurable concept, and one supported by a set of studies indicating that subjective well-being (SWB) measures contain “substantial amounts of valid variance” (Diener 1984: 551). Firstly, SWB measures have demonstrated temporal stability (Chamberlain and Zika 1992; Costa et al. 1987), indicating that people’s happiness cannot simply be equated with transient moods. Secondly, confidence about the measures also derives from the apparently stable correlation between happiness and a set of other variables which are generally accepted as “objective” measures of well-being, such as marriage, employment and income (See Dolan et al. (2008) for a review).Footnote 2 This line of evidence suggests that human happiness is responsive to the wider societal environment. Thirdly, recent progress in neuroscience has provided evidence on the validity of measures by linking human’s feelings of pleasure with the activities of the brain. More specifically, positive feelings have been found to be related to brain activity in the left side of pre-frontal cortex, whereas negative feelings are now understood to be related to activity in equivalent positions on the right side of brain (Davidson 2000), a finding confirmed by Urry et al. (2004) who reported a correlation of .33 between greater left than right frontal activity and psychological well-being. Taken overall, then, the evidence lends strong support for the argument that happiness should be seen as a scientific and measurable concept and one to be taken seriously.

2 The Easterlin Paradox

Alongside such scientific evidence about happiness, is the social science interest, particularly surrounding what is known as the Easterlin Paradox–the contested relationship between happiness and income–which provides the focus for this article. The Easterlin Paradox, which was first proposed in 1974, and continues to invoke comment and controversy in influential academic journals, basically posits that increases in wealth do not necessarily generate increased happiness. Easterlin, the original proponent of this paradox, together with a number of other social science researchers, have undertaken several follow-up studies which have provided further evidence in support of the proposition (Easterlin 1974, 1995; Easterlin et al. 2010), and their findings have been corroborated by various other scholars who have similarly identified a flat or declining trend in happiness in industrialized countries (Blanchflower and Oswald 2004; Oswald 1997). That is a nil relationship between happiness and income. Through the continual efforts pioneered by Richard Easterlin, such findings has been replicated beyond the well-developed countries, to some transition countries (Easterlin 2009), Latin American countries (Easterlin et al. 2010), as well as China in a recent paper (Easterlin et al. 2012).

Obviously, such a counterintuitive finding runs counter to countless cross-sectional analyses revealing that material wealth did matter in determining self-reported happiness (Appleton and Song 2008; Diener et al. 1993, 1995). Additionally, several other academics (notably, Rutt Veenhoven) have questioned the inference in the paradox that increases in income are unable to engender greater happiness (Hagerty and Veenhoven 2003; Veenhoven and Hagerty 2006). For instance, in a rebuttal of the Easterlin Paradox, Hagerty and Veenhoven (2003) found a positive correlation between national income and happiness. More supportive evidence has been provided by Stevenson and Wolfers’s (2008) time series analysis, who reported a positive link between subjective well-being and GDP per capita. Furthermore, their conclusion has been buttressed by findings detecting a significant influence of income on happiness in a series of panel studies (Di Tella and MacCulloch 2008; Di Tella et al. 2003; Pouwels et al. 2008). A middle ground, on this issue has been provided by Layard (2005), who has argued a more complex relationship between the two variables exists and that beyond a certain level of income further increases in happiness cannot be achieved. Actually, Veenhoven (1991: 10) himself had suggested similarly in rechecking the proof of Easterlin Paradox, which suggested the impact of wealth on happiness is subject to a law of diminishing returns.

Inevitably, the controversy surrounding the happiness-income paradox is of more than academic interest given its significant policy implications. For instance, if economic growth fails to improve people’s happiness beyond a certain income threshold, it might seem pointless for governments of wealthier societies to continue the pursuit of economic advance. Indeed, the happiness-income paradox has provided a challenge to the long-held assumption that economic growth necessarily links with well-being, suggesting the need to think differently about how we define and measure economic and social progress. Given the potentially enormous policy significance here, and continuing debate about the Easterlin paradox, new studies would surely be helpful in providing greater certainty and confidence about how economic growth affects the state of wellbeing of societies. Accordingly, this article makes a further contribution to the subject by mapping the time trend of happiness in the fast developing country of China.

3 Life Satisfaction: The Chinese Experience

China has experienced tremendous economic growth in the past three decades. Some economic indicators, like GDP growth, foreign trade volume, etc., are frequently cited as indicative of, the tremendous achievements of this country since the initiation of a market-based economy in 1978. Since then, have come more than three decades of rapid growth in which the living standards of most Chinese people have improved enormously. According to the National Bureau of Statistics of China, the disposable income (per capita) of urban residents has increased from 1,510 RMB in 1990–19,109 RMB in 2010 while the net income of rural residents has risen nearly nine-fold (National Bureau of Statistics of China 2011). In addition to the economic progress, China has also experienced exceptional performance on a wide range of social indicators; notably poverty reduction, school enrollment rates, and life expectancy. In fact, China’s Human Development Index has risen from 0.404 in 1980–0.630 in 2011(UNDP 2011), which again indicates remarkable improvement in quality of life in the country.

However, such overall statistics cannot conceal various disturbing social problems that appear to have accompanied the progress. Deterioration of environment, an expanding wealth gap, and increasing instances of social conflict, to name just three, perhaps suggest an unbalanced development of Chinese society and raise questions about the appropriateness of measuring progress simply in terms of national economic indicators. Instead, as Campbell et al. (1976) have argued, given that the way in which citizen perceive their situation is critical to their assessment of quality of life, it is important also to take note of relevant ‘subjective’ indicators as a basis for informing policy making. Furthermore, using life satisfaction indicators as supplementary measures of social progress has the benefit of providing a direct measure of quality of life (Diener and Suh 1997). In short, the argument is that a combination of objective and subjective indicators provides a more complete picture of the functioning of a society over time.

4 Does More Money Buy Chinese People More Happiness?

What is the evidence from China regarding the relationship between economic growth and happiness? In fact, most published research on the Easterlin Paradox has focused on developed countries, particularly the US, while to date there has been a paucity of studies on this issue in China. Indeed, previous studies based on China have been limited to cross-sectional analyses which revealed little of the time trend in happiness in the country (Davey and Rato 2012). Meanwhile, the contradictory conclusions on the gradient of income and happiness make it impossible to infer the correlation of these two variables in China based on previous studies (Easterlin et al. 2010; Stevenson and Wolfers 2008).

However, in recent years, a number of new studies have concentrated on the Easterlin Paradox in China and the subject has attracted much scholarly attention. Kahneman and Krueger’s (2006) work is one such study that has examined how life satisfaction has changed overtime in China. Based on a Gallup Poll report, the authors noted a mild decrease in the percentage of people expressing satisfaction with their life and an increasing percentage of ‘dissatisfied’ respondents. Indeed, they found there to be no increase in reported life satisfaction in China between 1994 and 2005. Other researchers have drawn more negative conclusions. Based on Ruut Veenhoven’s World Database of Happiness, Inglehart et al., for example, showed the level of happiness in China to be decreasing, with a trend-line based on three data points (Inglehart et al. 2008a). Similarly, Brockmann et al. (2009) noted a general decline in life satisfaction in the country during the 1990s and found that the trend held true for different social groups as well. They summarized the overall trend of life satisfaction in China as one that “fell considerably” and viewed it as something of a “puzzle”.

However, a more recent study conducted by Easterlin and his associates (2012) reached a rather different conclusion. Based on a combination of six datasets covering China, they found that changes in life satisfaction followed a U-shaped curve with a trough occurring around the years 2000–2005. Accordingly, they concluded that the trajectory of life satisfaction in China was generally comparable with other countries in transition, particularly in Eastern Europe; that is, with life satisfaction declining initially in the transition before making recovery.

As inferred from the above discussion, there has been little general consensus regarding the trend in happiness in China. However, methodological deficiencies have been a significant problem for the studies to date. Unlike in the US and many European countries, where citizens’ happiness has been investigated on a regular basis, there have been no on-going datasets in China covering extended time periods. Consequently, research conclusions to date have had to rely heavily on single sources, many of which have been based on fairly limited observations by which to pinpoint changes in life satisfaction over time. As Bjørnskov et al. (2008: 322) have pointed out, in analyzing the trend of happiness, missing observations in data would introduce uncertainty and instability to results. Therefore, it is unreliable to base conclusions on a single dataset without taking into account other data available. To be fair, Easterlin et al. (2012) have made considerable progress in this regard by using several different datasets. However, the conclusions derived from each such dataset have proved somewhat contradictory, and this has prevented the authors from producing a consistent picture (See Fig. 1).

The trend of life satisfaction in China. Source Easterlin et al. (2012)

The challenge for our own research, then, was to alleviate the problem of insufficient observation points and in this way generate more comprehensive and coherent conclusions about the time trend of life satisfaction. To this end, a series of different datasets containing happiness items were synthesized into a single set by standardizing the average scores from each. In this respect, the key objective for our study was to identify the overall trend in life satisfaction in China over the past two decades through analysis of a combination of datasets, and with the results so derived then being plotted against indices of economic growth to see the extent of statistical correlation. In this way we aimed to test the core element of the Easterlin Paradox in the context of China.

5 Methods and Data Sources

5.1 The Transformation Procedure

As indicated, several datasets were used in this study for exploring the time trend in life satisfaction in China. However, a limitation here was that the particular wordings of the questions on which these were based varied somewhat from one to another, as did the response options and the time horizons. Two strategies for dealing with such variances adopted in previous studies have been either to rely on just a single dataset or to present the analyses separately–neither being without problems. With the former strategy, a key limitation would be that no single dataset could reliably be representative of a country as large as China, given the relative smallness of sample size. As for the latter strategy, while it would offer some advantages over the former one in terms of larger sample size, the presentation of separate analyses would obviously represent a significant shortcoming, as we have seen in Easterlin et al.’ (2012) analysis, where the conflicting trends derived from different datasets make it difficult to reach an unequivocal conclusion. For these reasons, the approach adopted in our study involved splicing different datasets together by standardizing their different measures of subjective well-being, and so minimizing the problem of incomparability while maximizing the opportunity for a more comprehensive form of analysis.

Essentially, the goal of standardization is to apply a uniform metric to ensure comparability between the average happiness scores in each dataset. Several commonly used metrics referred to in the literature, have involved means (Brockmann et al. 2009), population proportions (Kahneman and Krueger 2006) and ordered probit (Stevenson and Wolfers 2008). The latter authors (2008: 75–78) also compared the pros and cons of different metrics but found that choice in this respect had little influence on the results. In our own research, the particular metric used was the Percentage of Scale Maximum (PSM), as proposed by Cummins (1995). PSM is computed by the following formula:

Note: PSM is the abbreviation of Percentage of Scale Maximum. MO is the mean on original scale. V1 denotes the lowest possible score on original scale, whereas Vh represents the highest possible score on original scale.

The reasons for this choice of metric were as follows. First, PSM has a larger range (from 0 to 100), so could be expected to capture more variation in happiness measures thus making it more sensitive. Second, it would be more readily interpretable; the higher the score, the happier the state, and vice versa. Third, PSM would help to standardize for differences in the response options of the surveys underlying the various datasets. Here, it is pertinent to note that this is the approach advocated by Veenhoven (1993) and also the one applied in the study by Miller and Miller (1991) of citizens’ evaluation of public services.

Although the standardization process in this research assumed the cardinality of responses, which was not necessarily the case as Veenhoven (2009: 46) has pointed out, it should be noted that a considerable body of other research has argued persuasively the cardinal nature of happiness measures (Ng 1996, 1997). In any event, it is reassuring to note that analyses based on both cardinal and ordinal assumptions produced identical results when happiness or life satisfaction was regressed on a set of predictors (Blanchflower and Oswald 2004; Ferrer-i-Carbonell and Frijters 2004; Frey and Stutzer 2002).

5.2 The Datasets

To achieve a balance between maximization of observationsFootnote 3 and the quality of data (e.g. representativeness), a number of secondary datasets were employed in this research. These were: four waves of the World Values Survey (WVS), four waves of the China General Social Survey (CGSS), three waves of the Asianbarometer survey (AB), four waves of the Pew Global Attitudes surveys (Pew), the China HorizonFootnote 4 survey and the China Household Income Project (CHIP). In addition, through the supporting information offered by Easterlin and his colleages (2012), the results of Gallup surveys covering China in the period from 1997 to 2011 were also included in the analysis.

The combination of these various datasets provided a sizeable sample and one covering a time span of some twenty years (well beyond that covered by any single dataset), and thus served to strengthen the validity of the conclusions. Of particular significance in this context was the lengthy time period (i.e. more than 10 years), which was considered as especially relevant in exploring the happiness-income paradox (Easterlin et al. 2010). The key criterion used in selecting the datasets was that each should be designed to provide a nationally representative sample.Footnote 5 While most of the chosen datasets had already individually been the subject of scholarly analysis, a particularly significant step forward in our research lay in its combination of available datasets for the conduct of an altogether large-scale investigation.

With the exception of the WVS, all of the datasets used focused either on respondents’ “happiness” or their “life satisfaction”, and there is solid evidence to suggest that these notions capture different dimensions of the concept of subjective well-being–the former being more to do with one’s on-line mood; the latter being more about the gap between aspirations and reality (Diener et al. 1999). In addition to these measures (i.e. happiness and life satisfaction), the Cantril scale (10 points) was used in the Gallup and Pew surveys to gauge respondents’ subjective well-being, and was treated as a further measure in its own right. Initially, all three measures were analyzed separately to assess the extent to which they might be considered as mutually supportive.

6 Time Series Comparisons Based on Standardized Scores

The particular scales used by the different surveys for measuring subjective well-being were grouped into three categories, as indicated–the happiness measure, the life satisfaction measure and Cantril’s ladder of life. The standardization procedure described above was then applied to compute PSM scores for each dataset on a comparable basis (where two or more surveys had been conducted in a given year, the mean PSM was computed). In the paragraphs below we present the findings for the three categories separately and then, finally, with the three in combination.

6.1 Happiness Scores

The happiness scores were generated from AB, CGSS and WVS datasets over a time period from 1990 to 2008. Each of these datasets contained a specific question asking participants about their happiness.

As can be seen from Fig. 2, the main message from this analysis is that happiness in China in this period showed a slight downward trend, albeit with signs of improvement in later years. However, while the regression line used to fit the datasets attracted a negative coefficient (b = −0.075), it was found not to be statistically significant (p > .1).

6.2 Life Satisfaction Scores

To examine the trend in life satisfaction, we used the following three datasets: WVS, Gallup and China Horizon–albeit each with their own response categorizations (WCS having a 0–10 scale, Gallup having a 1–4 scale, and China Horizon a 1–5 scale). Figure 3 displays the result. (Where it can be seen there were more observations than the “happiness” measure).

Again, a negative trend is apparent, with the starting point for Chinese life satisfaction registering at 69.89 and then successive scores failing to achieve or exceed this level. Again, the regression coefficient obtained was negative (b = −0.178), but also failed to reach the conventional significance level of 5 %, although the size of the negative coefficient (compared with that for happiness), suggested that life satisfaction in China has been experiencing a more salient decline.

6.3 Cantril’s Ladder of Life

Among the available datasets, only Gallup and Pew used a ‘ladder of life’ to gauge the happiness of Chinese people and, unfortunately, the span of time covered was limited to post 2000 (in contrast with the happiness and the life satisfaction measures). Nevertheless, in this period at least, as Fig. 4 shows, the trend in self-perception of well-being among the Chinese people appears to have been downwards. The regression coefficient here was −0.218 (p > .1), indicating that in respect of Cantril’s ladder of life, subjective well-being in China also experienced a descending trend.

6.4 The Overall Trend of Subjective Well-Being in China

By grouping the similar measures of SWB into the three categories we were able to generate more coherent and straightforward results. Although the three types of measure were somewhat different from one another, they did show a fairly consistent negative trend in subjective well-being. To fulfill the key aim of this research, the next task involved combining the datasets together to provide an overall view of subjective well-being in China.Footnote 6

In this respect, as Fig. 5 shows, another negative trend was apparent, this one being steeper than those for the three individual categories respectively.

Indeed, the computed regression line registered a much larger coefficient (b = − 0.505), indicating a more marked decline in subjective well-being. Meanwhile, probably due to the larger number of observations, the obtained t statistic (t = − 4.10) of the time variable was large enough to reject the null hypothesis (p < .01). In summary, the evidence presented in the separate and the combined trend in happiness lends support to an overall conclusion that happiness among the Chinese people has indeed been declining over the past two decades.

7 The Relationship Between Happiness and Economic Growth

From this conclusion, our next step was to examine the relationship between happiness and economic growth. To this end, the happiness scoresFootnote 7 of given time points were taken as proxies for subjective well-being in each year, while the key indicator of economic performance used was China’s annual GDP per capita (as has commonly been used in the literature). Also in line with other published research in this context, bivariate correlation was employed to examine the extent of association between happiness and material wealth.

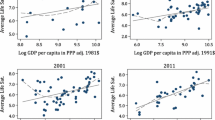

Figure 6 presents a striking contrast in the trends of these respective variables. While the trend in GDP per capita is shown to have risen steeply, that for happiness displays a much flatter pattern, indeed, one that is marginally downwards. The key message, then, is that, in spite of the substantial growth in terms of GDP per head, happiness among Chinese people has shown no corresponding increase. Happiness scores were also plotted against GDP per capita over the same period t (see Fig. 7).

The trend of Ln GDP per capita and happiness. The data of GDP per capita was drawn from China Statistical Year Book (2011)

As can be seen, the trend in happiness was negatively related with the logarithm of GDP per capita. Contrary to what might perhaps be expected, economic growth has so far failed to lift the overall level of happiness among the Chinese people. Moreover, regressing happiness scores on GDP per capita (again on a logarithmic scale) also confirmed the conclusion from Fig. 6, that GDP per capita attracted a significant negative coefficient (b = − 3.10, p < .01). The clear statistical significance is especially noteworthy given that there were only 16 data points in this analysis. In statistical terms at least, then, GDP per capita would seem to be a depressor of happiness.

To triangulate and further validate these findings, an alternative indicator of individual wealth was examined in a similar bivariate analysis. Here the volume of personal savings per capita was used as a proxy for spending money in people’s pockets and, as with preceding analysis, this measure was plotted against overall happiness scores, with Fig. 8 summarizing the result.

In fact, an almost identical result was revealed: with income (personal savings) and happiness again negatively associated overtime. Having more money in the pocket again seems not to have made the Chinese people happier. Ordinary least squares (OLS) regression was also performed to measure the relationship between the two variables. This yielded a negative coefficient (b = − 2.60), which also proved to be statistically significant at the 1 % level. As such, the findings here of a negative relationship between wealth and happiness are in contrast with those derived from the various cross-sectional studies that reported happiness to be positively associated with income (Appleton and Song 2008; Knight and Gunatilaka 2011) .Footnote 8

8 Concluding Discussion

With the remarkable economic growth of China over the past thirty years, that has brought unprecedented increases in material wealth for so many of its people, one might have expected at least some corresponding increase in levels of happiness. However, the conclusion from this research is that such an expectation has been unfulfilled. Indeed, the finding of a negative correlation between happiness and economic growth casts doubt on the presumption that such enhanced personal wealth and the improvements in living standards have been sufficient to bring about increased happiness, at least in the Chinese context. Beyond this overarching finding, two other key conclusions from our research can be summarized as follows.

First, in terms of absolute levels, happiness in China has to date registered a decidedly low score. In surveys in Northwest European countries, more than 90 % of respondents have been found to feel happy and satisfied with their lives (Inglehart and Klingemann 2000: 170), while in China, the corresponding figure was only 62.5 % on average.Footnote 9 Moreover, this percentage is lower than in many other less developed countries, such as Egypt, Brazil, Mexico and Thailand, where more than 80 % of respondents reported positive feelings (Diener and Diener 1996: 181). Taking the data on subjective well-being (Fig. 5) as a proxy for happiness in China, the average PSM score was 59.4; far lower than the “gold standard” for subjective well-being, as computed by Cummins (1995). In fact, according to the recently published The World Happiness Report, levels of happiness in China were lower than various other and (culturally quite similar) South East Asian countries (Helliwell et al. 2012).

Second, in addition to the low level of happiness relative to other countries, as our analysis has shown, China has been experiencing a decline in happiness levels overtime. Indeed, based on the three categories of measures of subjective well-being and the combined measure, our research has provided strong evidence of growing unhappiness over the past two decades, despite the increase in wealth. In short, it is reasonable to conclude that the happiness-income paradox proposed by Easterlin holds true in China. In this respect, our finding is consistent with that of Brockmann et al. (2009), but at odds with that of Stevenson and Wolfer (2008), who estimated a positive correlation between income and happiness. In fact, as indicated, Easterlin and his colleagues suggested a U-shaped pattern to the relationship, but our research does not support this, instead identifying among some fluctuations, an overall declining trend in happiness in China, at least over the most recent two decades. Moreover, if this trend were to continue, there would seem to be every prospect of a widening gap between happiness in China and in most other countries, given that elsewhere, the available evidence suggests rising levels of happiness (Inglehart et al. 2008b).

In some of the literature, decreasing levels of happiness have been triangulated with the suicide rate and increases in the incidence of mental illness, two variables that have been suggested as objective indicators of unhappiness (Helliwell and Huang 2008; Layard 2005). In the context of China, the growth of unhappiness might perhaps be compared with the amount of petitioning Beijing. Despite the absence of definitive statistics on such activity in the period covered by our analysis, there is general recognition of a marked increase in the number of petitioners who “come to the capital to seek redress of grievances derived from their dealings with local authorities” (Li et al. 2012: 317). In essence, petitioning is an activity through which individuals express their dissatisfaction, so any growth in such activity might be viewed as an indication of increasing unhappiness in the country.

Without doubt, a finding suggesting a decline in happiness levels has many significant policy implications. As the quotation at the head of this article suggests, life satisfaction has a close connection with people’s confidence in their country’s political regimes. Inglehart and his colleagues, for example, have argued that changes in subjective well-being can undermine a political regime (Inglehart and Klingemann 2000: 177; Inglehart 1997: 166–215), because if people perceive their quality of life to be declining, they are likely to blame the political regime. This argument, and particularly the decline in life satisfaction, has been applied to help understand the collapse of the former Soviet Union and of regime change in a number of other countries, where a decline in life satisfaction has preceded the fall of the regime (Inglehart and Klingemann 2000: 176–177). Accordingly, no political/administrative regime can sensibly afford to neglect the state of happiness among its people.

Specifically in a Chinese context, despite great success in increasing levels of material wealth, the market economy appears not to have guaranteed improvement in the individual’s sense of well-being, with our correlation analyses, confirming in quantitative terms that money in China has not brought about extra happiness, at least to date. This is particularly ironic given the growth of belief in recent years in market ideology and market-based reforms within the country. Overall, the findings of our research suggest a pressing need for reflection upon, and answers to be sought to, the following two key questions, (a) why has strong economic performance failed to make people happier? and (b) precisely what circumstances might be responsible for the deterioration in self-assessed happiness?

It must be acknowledged that the limitations of the research described in this paper need to be borne in mind in interpreting the results and in any consideration of their implications. In this respect, for example, as Easterlin et al. (2012) have pointed out in their own analysis of a similar dataset, the majority of surveys fail to include the floating population, whose average happiness levels tend to be lower (Knight and Gunatilaka 2010) and, as a result, the under-representativeness of these people may introduce bias into the findings.

At the same time, it must be emphasized that the pooling of different datasets is rarely straightforward because of the need to standardize the different measures. Moreover, compared with many long term and regularly-collected datasets, particularly in the US and European countries, data on life satisfaction or happiness in China has generally been collected by scholars and academic organizations, often with more limited financial resources and different priorities, making for fragmentation, lack of standardization and difficulties of comparability. For such reasons, our results should be treated as preliminary and indicative of the generalized picture in China rather than as definitive or necessarily applicable to all contexts or social groups within the country. To better capture the patterns and trends of happiness in China, a larger scale survey, and for a more extended period, would be welcome in confirming and developing the findings summarized here.

Notes

In this research, happiness, life satisfaction and subjective well-being are used interchangeably, also note that Easterlin Paradox and happiness-income paradox are viewed as synonyms.

Perhaps the most reassuring evidence of the validity of such subjective data is that happiness models share a similar equation across a set of countries and over time. See Di Tella and MacCulloch (2008) for more details.

Given most of surveys were conducted after 2000, we also consulted authoritative experts in the field of happiness in China for any unnoticed datasets, and the consulting confirmed our own search.

Note that there are two differences between our use of Horizon’s data with Easterlin et al. (2012). Firstly, they used the results of urban sample, while we took the whole sample. Meanwhile, consulting the Horizon Company, we analyzed the survey results after 2000.

Note although all the surveys listed in the table purported to get a national representative sample, with the exception of CGSS, the sample was disproportionately urban residents. Descriptions of datasets in details are put in “Appendix”.

We use the same happiness scores by synthesizing three types of measure, as the data presented in Fig. 5.

It was unnecessary to do more bivariate analyses with additional economic indicators because China generally performs well with regard to a wide range of measure.

We calculated the raw average based on WVS, Pew and CGSS which individual responses are available.

References

Appleton, S., & Song, L. (2008). Life satisfaction in urban China: Components and determinants. World Development, 36, 2325–2340.

Bjørnskov, C., Gupta, N., & Pedersen, P. (2008). Analysing trends in subjective well-being in 15 European countries, 1973–2002. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9, 317–330.

Blanchflower, D. G., & Oswald, A. J. (2004). Well-being over time in Britain and the USA. Journal of Public Economics, 88, 1359–1386.

Brockmann, H., Delhey, J., Welzel, C., & Yuan, H. (2009). The China puzzle: Falling happiness in a rising economy. Journal of Happiness Studies, 10, 387–405.

Campbell, A., Converse, P. E., & Rodgers, W. L. (1976). The quality of American life: Perceptions, evaluations, and satisfactions. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Chamberlain, K., & Zika, S. (1992). Stability and change in subjective well-being over short time periods. Social Indicators Research, 26, 101–117.

China, National Bureau of Statistics of. (2011). Per capita annual income and engel’s coefficient of urban and rural households. http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/ndsj/2011/indexch.htm 2012/06/15.

Costa, P. T., McCrae, R. R., & Zonderman, A. B. (1987). Environmental and dispositional influences on well-being: Longitudinal follow-up of an American national sample. British Journal of Psychology, 78, 299–306.

Cummins, R. A. (1995). On the trail of the gold standard for subjective well-being. Social Indicators Research, 35, 179–200.

Davey, G., & Rato, R. (2012). Subjective wellbeing in China: A review. Journal of Happiness Studies, 13, 333–346.

Davidson, R. J. (2000). Affective style, psychopathology, and resilience: Brain mechanisms and plasticity. The American psychologist, 55, 1196–1214.

Di Tella, R., & MacCulloch, R. (2008). Gross national happiness as an answer to the Easterlin Paradox? Journal of Development Economics, 86, 22–42.

Di Tella, R., MacCulloch, R. J., & Oswald, A. J. (2003). The macroeconomics of happiness. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 85, 809–827.

Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 95, 542–575.

Diener, E., & Diener, C. (1996). Most people are happy. Psychological Science, 7, 181–185.

Diener, E., Diener, M., & Diener, C. (1995). Factors predicting the subjective well-being of nations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69, 851–864.

Diener, E., Sandvik, E., Seidlitz, L., & Diener, M. (1993). The relationship between income and subjective well-being: Relative or absolute? Social Indicators Research, 28, 195–223.

Diener, E., & Suh, E. (1997). Measuring quality of life: Economic, social, and subjective indicators. Social Indicators Research, 40, 189–216.

Diener, E., Suh, E. M., Lucas, R. E., & Smith, H. L. (1999). Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125, 276–302.

Dolan, P., Layard, R., Metcalfe, R., & ONS. (2011). Measuring subjective well-being for public policy: Recommnendations on measures.

Dolan, P., Peasgood, T., & White, M. (2008). Do we really know what makes us happy? A review of the economic literature on the factors associated with subjective well-being. Journal of Economic Psychology, 29, 94–122.

Easterlin, R. (1974). Does economic growth improve the human lot? Some empirical evidence. In P. A. David & M. W. Reder (Eds.), Nations and household in economic growth: Essays in honour of moses: New York and London: Academic Press.

Easterlin, R. (1995). Will raising the incomes of all increase the happiness of all? Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 27, 35–47.

Easterlin, R. (2009). Lost in transition: Life satisfaction on the road to capitalism. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 71, 130–145.

Easterlin, R., McVey, L. A., Switek, M., Sawangfa, O., & Zweig, J. S. (2010). The happiness–income paradox revisited. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107, 22463–22468.

Easterlin, R., Morgan, R., Switek, M., & Wang, F. (2012). China’s life satisfaction, 1990–2010. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(25), 1–6.

Ferrer-i-Carbonell, A., & Frijters, P. (2004). How important is methodology for the estimates of the determinants of happiness? The Economic Journal, 114, 641–659.

Frey, B. S., & Stutzer, A. (2002). Happiness and economics: How the economy and institutions affect human well-being. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Hagerty, M. R., & Veenhoven, R. (2003). Wealth and happiness revisited—Growing national income does go with greater happiness. Social Indicators Research, 64, 1–27.

Helliwell, J. F., & Huang, H. (2008). How’s your government? International evidence linking good government and well-being. British Journal of Political Science, 38, 595–619.

Helliwell, J., Layard, R., & Sachs, J. (2012). World happiness report. Earth Institute.

Inglehart, R. (1997). Modernization and postmodernization: Cultural, economic, and political change in 43 societies. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Inglehart, R., Foa, R., Peterson, C., & Welzel, C. (2008a). Development, freedom, and rising happiness: A global perspective (1981–2007). Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3, 264–285.

Inglehart, R., Foa, R., & Welzel, C. (2008a). Happiness trends in 24 countries, 1946–2006. In World values survey, vol. 2012.

Inglehart, R., & Klingemann, H.-D. (2000). Genes, culture, democracy, and happiness. In E. Diener & E. Suh (Eds.), Culture and subjective well-being (pp. 165–184). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Kahneman, D., & Krueger, A. B. (2006). Developments in the measurement of subjective well-being. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 20, 3–24.

Knight, J., & Gunatilaka, R. (2010). Great expectations? The subjective well-being of rural–urban migrants in China. World Development, 38, 113–124.

Knight, J., & Gunatilaka, R. (2011). Does economic growth raise happiness in China? Oxford Development Studies, 39, 1–24.

Lane, R. (2001). The loss of happiness in market democracies. New Haven, London: Yale University Press.

Layard, R. (2005). Happiness: Lessons from a new science. New York: Penguin Books.

Li, L., Liu, M., & O’Brien, K. J. (2012). Petitioning Beijing: The high tide of 2003–2006. The China Quarterly FirstView: 1–22.

Miller, T. I., & Miller, M. A. (1991). Standards of excellence: US residents’ evaluations of local government services. Public Administration Review, 51, 503–514.

Ng, Y.-K. (1996). Happiness surveys: Some comparability issues and an exploratory survey based on just perceivable increments. Social Indicators Research, 38, 1–27.

Ng, Y.-K. (1997). A case for happiness, cardinalism, and interpersonal comparability. The Economic Journal, 107, 1848–1858.

Oswald, A. J. (1997). Happiness and economic performance. The Economic Journal, 107, 1815–1831.

Pouwels, B., Siegers, J., & Vlasblom, J. D. (2008). Income, working hours, and happiness. Economics Letters, 99, 72–74.

Stevenson, B., & Wolfers, J. (2008). Economic growth and subjective well-being: Reassessing the Easterlin paradox. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 1,1–87.

Stiglitz, J. E., Sen, A., & Fitoussi, J-P. (2009). Report by the commission on the measurement of economic performance and social progress. Paris.

UNDP. (2011). International human development indicators. vol. 2012.

Urry, H. L., Nitschke, J. B., Dolski, I., Jackson, D. C., Dalton, K. M., Mueller, C. J., et al. (2004). Making a life worth living: Neural correlates of well-being. Psychological Science, 15, 367–372.

Veenhoven, R. (1991). Is happiness relative? Social Indicators Research, 24, 1–34.

Veenhoven, R. (1993). Happiness in nations: Subjective appreciation of life in 56 nations 1946–1992. http://www2.eur.nl/fsw/research/veenhoven/Pub1990s/93b-con.html 2012/05/28.

Veenhoven, R. (2009). The international scale interval study: Improving the comparability of responses to survey questions about happiness. Quality of life and the millennium challenge. In V. Møller & D. Huschkapp (Eds.), Social indicators research series (Vol. 35, pp. 45–58). Netherlands: Springer.

Veenhoven, R., & Hagerty, M. (2006). Rising happiness in nations 1946–2004: A reply to easterlin. Social Indicators Research, 79, 421–436.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Jiayuan Li is a Doctoral Researcher and John W Raine is his supervisor in the Institute of Local Government Studies, University of Birmingham, UK. This research was conducted as part of Jiayuan Li’s doctoral thesis. The authors would like to thank Professor Tony Bovaird, John Knight and Andrew Oswald and the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments on earlier versions of this article.

Appendix

Appendix

This appendix provides a brief introduction regarding the issues of research designs of each dataset used in this research. For the relevant details of the surveys conducted by Gallup, please refer to the supporting information of Easterlin et al. (2012).

-

1.

China General Social Survey (CGSS)

Title

China General Social Survey

Years of survey

2003, 2005, 2006, 2008

Sample frames

Male and female, age 18–69

Used items

The question asked in the surveys reads: Generally speaking, how do you feel about the life you lead? You feel about your life as very unhappy, unhappy, so–so or happy or very happy? The response options are very happy, quite happy, so–so and unhappy. In the third wave of CGSS, there is a question asking respondents about their satisfaction with life, which is phrased as, Overall, do you feel satisfied with your current living condition? The options range from 1 to 5, with 1 indicates very satisfied and 5 indicates very unsatisfied. The coding is reversed to make the response the higher score means more satisfied

Sampling methods

Multi-stage stratified sampling

Size of sample

5,894–11,000 respondents each survey

Data collection method

Face to face interview

-

2.

Asian Barometer Survey

Title

The Asian Barometer Survey

Years of survey

2003, 2004, 2006, 2008

Sample frames

Male and female aged 20–69

Used items

The question reads: All things considered, would you say that you are happy these days? Very happy, quite happy, neither happy nor unhappy, not too happy and very unhappy

Sampling methods

Multi-stage stratified sampling

Size of sample

800–2,000 respondents each survey

Data collection method

Face to face interview

-

3.

Chinese Household Income Project (2002)

Title

Chinese Household Income Project

Years of survey

2002

Sample frames

Resident population of the People’s Republic of China

Used items

The question asked in both the rural and the urban surveys reads, Generally speaking, how happy are you these days? Very happy, happy, so–so, not happy, and not at all happy

Sampling methods

Two-stage stratified systematic random sampling

Size of sample

16,035 respondents

Data collection method

Face to face interview

-

4.

World Values Survey

Title

World Values Survey

Years of survey

1990, 1995, 2001, 2007

Sample frames

Male and female, 18 and more years

Used items

Two standardized “happiness” and “life satisfaction” questions have been asked in each survey. Respondents’ happiness was elicited by their responses to the question: Taking all things together, would you say you are very happy, quite happy, not very happy or not at all happy. For life satisfaction, participants were asked, All things considered, how satisfied are you with your life as a whole these days? The response is an interval scale rating from 1 (dissatisfied) to 10 (satisfied)

Sampling methods

Multi-stage stratified random sampling

Size of sample

1,000–2,000 respondents each survey

Data collection method

Face to face interview

-

5.

China Horizon

Title | China Horizon |

|---|---|

Years of survey | 2000–2011 |

Sample frames | In rural area, male and female age from 16 to 60, in urban area, both sexes, aged from 18 to 60 |

Used items | The question reads: Generally speaking, are you satisfied with your current life: very satisfied, fairly satisfied, average, fairly dissatisfied, or very dissatisfied? |

Sampling methods | Multi-stage stratified random sampling |

Size of sample | 45,710 respondents (Total sample from 2000 to 2010) |

Data collection method | Face to face interview |

-

6.

Pew Global Attitudes Project

Title | Pew Global Attitudes Project |

|---|---|

Years of survey | 2002, 2005, 2007 2009, 2010 |

Sample frames | Male and female, age 18–60 |

Used items | In 2002, 2005, 2007, 2010, the question reads, Here is a ladder representing the “ladder of life.” Let’s suppose the top of the ladder represents the best possible life for you; and the bottom, the worst possible life for you. On which step of the ladder do you feel you personally stand at the present time? Response options range from 0 to 10. In 2009, the question reads: Please tell me how satisfied you are with your life overall—would you say you are very satisfied, somewhat satisfied, somewhat dissatisfied, or very dissatisfied? Very satisfied, Somewhat satisfied, Somewhat dissatisfied, Very dissatisfied |

Sampling methods | Probability sampling |

Size of sample | 2,191–3,262 respondents each survey |

Data collection method | Face to face interview |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Li, J., Raine, J.W. The Time Trend of Life Satisfaction in China. Soc Indic Res 116, 409–427 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-013-0300-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-013-0300-4