Abstract

In this research, the relationship between fulfillment of needs, social capital, and sense of community and individual well-being has been explored by testing the perception of sense of community by means of residential satisfaction. The study involves the participations of 677 adults from Mersin, Turkey. A model in which social capital mediates the relationship of fulfillment of needs with sense of community and individual well-being has been validated by path analysis. Accordingly, fulfillment of needs and variables of social capital significantly predict sense of community and individual well-being. The results have been discussed in detail with regard to socio-cultural aspects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Being considered as one of the most significant feature of powerful and efficient societies, sense of community is one of the basic concepts which are particularly emphasized in urban studies and community psychology. As a setting the community, that can stimulate interdependence, mutual commitment and support, has been the focus of field of community psychology. The greatest consensus on the definition of sense of community revolves around perception of belongingness and cohesive feelings of membership or community; particularly the emotional connections or bonds between people based on a shared history, interests or concerns (Long and Perkins 2003). Sarason defines the term of sense of community (SOC) as “the sense that one was part of a readily available, mutually supportive network of relationships” (Sarason 1974, p. 1). SOC mainly refers to an individual’s experience or collective evaluation of community life. People need to feel this community membership and any social change stimulating it as well as increasing the subjective well-being and the quality of social life. The focus is on well-being of the community in the sphere of subjective well-being and quality of life as in urban studies and community psychology. Thanks to various social and subjective indicators, the efforts of assessing life quality of cities have been increasing since the beginning of Social Indicators Movement. (Andrews and Withey 1976; Campbell 1981; Diener and Suh 1997). The degree of well-being of a city or a community can be assessed in terms of cognitive and emotional judgments of citizens. The relationship between cognitive and emotional judgment expressions and various features of the city can be researched. Such studies identify several social and subjective indicators which have an effect on the evaluations of individual and group well-being (Andrews and Withey 1976; Diener 1984; Sirgy 2011; Yetim 2001). The capacity of meeting the needs of the society, the network connections that support these needs; the general sense of community, and social inheritance have an utmost importance in the judgments related to the individual’s positive evaluations about their well-being and flourishing.

One of the basic problems that should be stressed is to identify the factors forming a positive and high SOC. In this respect, McMillan and Chavis (1986) offer a more theoretical and clearer model of SOC which is made up of four elements (i.e., membership, influence, integration and fulfillment of needs, and shared emotional connection). After so many years, the model remains as the primary theoretical anchorage for most of the studies on SOC.

However, the empirical studies conducted on this model have failed to support the model (Chipuer and Pretty 1999; Obst et al. 2002). Some researchers have argued that SOC should be considered as placed on a continuum (negative-neutral-positive) and as simultaneously attached to different community settings (Brodsky and Marx 2001). Finally, Mankowski and Rappaport (1995, 2000) offered that it seems reasonable to consider SOC as a shared narrative. As it can be seen, there is not any consensus on the structure and assessment of SOC in literature whereas there are scales with wide validity and credibility, and strong theoretical basis associated with subjective well-being. Hence, we think that sense of community, city or settlement can be assessed through satisfaction scales, in which people are assessed on their satisfaction evaluations about humanistic (relationships, trust, belonging, interdependence etc.) and objective aspects of their urban or settlement areas. In other words, we suggest that the sense of community, society and city can be expressed with their general and specific well-being evaluations.

1 Antecedents of Sense of Community and Individual Well-Being

It has been suggested that one of the factors affecting SOC is to what extent a society meets the needs of the members of a city (McMillan and Chavis 1986). A city’s capacity of meeting the needs depends on the extent to which it is capable of meeting needs at different levels; one level being low-order (basic needs) needs and another one being high-order (educational, cultural, subjective etc.) needs. Having conducted an international comparison research on meeting needs, Diener and Diener (1995) indicated that wealthier nations appear to possess more resources with which citizens can attain higher order needs. In this research, it has been found that wealthier nations have better education, more civil rights, and more extensive scientific infrastructures. Based on international data, Veenhoven (1993) found that factors such as income, nutrition, equality, freedom, and education can account for 77 % of the variance in national happiness. In their studies based on the international data, Tay and Diener (2011) also found out that the fulfillment of basic needs predict 24 % of the subjective well-being variance. In brief, a society’s capacity of meeting needs of the people living there increases the sense of community of its individuals as well as the perceptions of subjective well-being and flourishing.

The availability of opportunities for individuals who live in the city, to exert control on their lives and to convey their requests and demands to relevant authorities is a rather significant problem. The accessibility of citizens and the community members to the local and general administrators; the ease of meeting of their demands and the implementation and application of citizens’ demands in practice; opportunities for citizens’ collective action as a pressure group; and their being a power in the political area are elements that indicate the quality of powerful and high solidarity societies. Being able to access to the fore-mentioned administrators; making their demands come true; organizing freely; forming a pressure group in elections are also among the social indicators of life quality (Sirgy 2011). These kinds of social indicators are examined within social capital category.

Social capital is a broad concept and there are several definitions of it in the literature (Bourdieu 1986; Coleman 1988; Portes 1998; Putnam 1993). These include various levels of participation and taking responsibilities voluntarily on community issues that generate feelings of community. For example James Coleman (1988) argued that social capital facilitates certain actions of actors within social structure. Pierre Bourdieu (1986) defined social capital as “the sum of the resources, actual or virtual, that accrue to an individual (or a group) by virtue of being enmeshed in a durable network of more or less institutionalized relationships of mutual acquaintance and recognition” (p. 248). Robert Putnam (2000) further specified the definition of social capital, arguing that it “refers to connections among individuals-social networks and norms of reciprocity and trustworthiness that arise from them” (p. 19). For Putnam (1993), (2000)) the concepts of social connectedness and civic engagement (e.g., visiting neighbors, engagement in politics, membership in church-related groups and in civic and fraternal organizations) are the main features of social capital. Paxton (1999) indicated that social capital seems to involve at least two important components: (1) objective associations between individuals (i.e., individuals are tied to each other in social life) and (2) subjective associations (the ties between individuals are trusting and reciprocal). In sum, trust and civicness should be taken into account in the general evaluation of social capital (Fukuyama 2001; Rostila 2011).

In making the trust evaluation, general evaluations as well as dimension-based specific evaluations are appropriate in revealing the net effects of the term, while civicness is an evaluation of social relevance, citizenship, and taking on responsibility for one’s city. As mentioned in the preceding paragraph, active interest of the members of the community is also evaluated as a social indicator in predicting the communal well-being. In this respect, social capital as an additional source and as an element of relationship promotion is expected to have an impact on sense of community perceptions. Uslaner (1999) proposes that social capital helps creating a vibrant community. Pooley et al. (2005) demonstrated the relationship between social capital and SOC as a qualitative relation. In addition, social capital is among the strong determinants of subjective well-being (Bjornskov 2003; Dolan et al. 2008).

Referring to strength of connections between people and organizations, and the trust in others, social capital’s relevance with fulfillment of needs is one of the foremost controversial issues (Coleman 1988; Putnam 2000). As it is generally identified as additional gain to the individuals’ primary resources; social capital’s being subsequent to meeting needs individually in the causal chain is appropriate. That is, the sources of social capital should be activated according to the rate at which needs are met. We should mention again that social capital comprises social resources that evolve in accessible social networks, civic engagements and social structures characterized by mutual trust. In other words, social capital is to be regarded as social resources accessible through participation in various types of social networks, making possible the achievement of certain ends, returns or benefits that would not be possible in its absence. In this regard, social capital makes it possible to access those resources that can only be acquired through social relationships. Acquiring information about new jobs or employment opportunities or receiving monetary and financial support for buying a house are examples of such resources. Similarly, individuals can voluntarily work for the school council for improving the quality of school education in their own neighborhood or they can make regular donations to the school council. Such voluntary activities help their own children to have better education and at the same time increase the socio-economical value of their living area. To summarize, individuals might rely on social capital to meet certain needs that cannot be otherwise met with personal resources or capabilities. Since social capital is subsequent to personal needs, it is more likely for social capital to mediate the relationship between fulfillment of needs and the outcome variables of sense of community and individual well-being.

The discussions regarding the relations of social capital and fulfillment of needs that have been mentioned so far, do not include any certainty about the causal direction of this relationship. There is not any empirical or certain evidence about the causal link to show whether fulfillment of needs precedes social capital. The reverse is also possible; however, we esteem that fulfillment of needs precedes social capital and social capital should be a mediator variable between the fulfillment of needs and SOC relationship.

The final point to be made is the claim that the evaluations of flourishing and life satisfaction, indicating subjective and psychological well-being are directly linked to this process entirely. That is, the relationship between meeting one’s needs and one’s social capital predicts individual’s well-being as well. We esteem that all variables affecting SOC have an impact on the evaluations of life satisfaction and flourishing. Ryan and Deci (2000) and Ryff (1989) mentioned competence, relatedness and autonomy as universal human needs affecting psychological well-being. We believe that being able to meet one’s needs and having appropriate social capital have an effect on the satisfaction of incentives of autonomy, relatedness and competence. Providing basic, health, social and educational needs emancipates the individual for her/his own motivation. Thus, individuals can shape their own flourishing. Individual’s having a strong trust and commitment to her/his society and neighborhood, and her/his civicness are also directly associated with the satisfaction of his/her relatedness incentives. In sum, fulfilling needs and the extent of social capital correlate with high life satisfaction and flourishing.

2 Socio-Cultural Perspectives on Social Capital

Many social researchers have predicted that one inevitable consequence of modernization is the unlimited growth of individualism, which poses serious threats to the organic unity of individuals and society by paving a road to social atomism, unbounded egoism, and distrust (Etzioni 1993, 1996). On the contrary, findings showed that individualism and modernity appear to be rather firmly associated with an increase of social capital (Allik and Realo 2004; Realo et al. 2008). Paradoxically, in societies where individuals are more autonomous and seemingly liberated from social bonds, the same individuals are also more inclined to form voluntarily associations and trust each other and to have a certain kind of public sprit. Thus, the autonomous and independence of the individual may be perceived as the prerequisites for establishing voluntary associations, trusting relationships, and mutual cooperation with one another. People may be brought by mere self-interest, but in their interaction, something else comes forth that leads not only to higher levels of mutual trust and cooperation but also greater economic prosperity, better health, and democratic life (Beem 1999; Inglehart and Baker 2000; Putnam et al. 1993).

It should be note that participation in many organizations does not threaten but rather encourages individualism (Triandis 1995). On the other hand collectivistic cultures generally promote family life and one in-group identifications. It tends to rule social life by providing the only source of social support, identity, and norms in this cultural structure. Triandis (1995) argued that individuation or the shift toward individualism is a consequence of multiple in-groups (i.e., numerous voluntary associations, civic organizations) that fragment social control over an individual and place more emphasis on personal responsibility. Many studies have shown that collectivism, familialism, and relationism are negatively correlated to social capital (Igarashi et al. 2008; Realo et al. 2008; Yamagashi and Yamagashi 1994). Development and modernization require that the network of trust is extended others outside of the traditional family circle and village. A narrow radius of trust and centrality of the family that are typical features of collectivistic cultures at exclusion of broader society becomes a hindrance to civicness and democratic society.

Positive characteristics such as high economic development levels, individualism and democratic life styles are generally observed in Western societies, and there are high correlations between indices of social capital and subjective well-being as well. People who seek high subjective well-being engage in altruistic and pro-social activities such as volunteering for community and charity groups more frequently than people with low subjective well-being (Tov and Diener 2008; Thoits and Hewitt 2001; Krueger et al. 2001). Moreover people who experience high levels of well-being on average tend to have more trusting, co-operative and pro-peace attitudes, more confidence in the government, and stronger support for democracy (Tov and Diener 2008; Diener and Tov 2007).

3 Why Turkish Culture?

Turkey presents an original and interesting societal structure because of the societal changes it has gone throughout its history, its cultural diversity and experience of modernity. Since the period of the Ottoman Empire, Turkey has chosen Westernization as the direction for progress (Inalcik and Quataert 1994; Mardin 2000). Beginning from the Tanzimat Reform Era and continuing with the foundation of the Turkish Republic, Turkey has been through several developments and improvements in family, education, social life, law, and civil rights, and has adopted Western values in these areas (Mardin 1992). By adopting a multi-party democratic system in 1950, an important step in the direction of the Western life style was taken. Turkey had achieved an important momentum of development by the year 1980; when liberal policies were put into practice. Opening to the global world and removal of obstacles to the free market economy in the country have increased the tendency for individualism as cultural values. After all, Turkey has made great strides in the direction of secularism, freedom of individual enterprise, freedom of thought, and free market economy, and as a result, has adopted a civil and pluralistic democratic social life style (Berkes 1998; Karpat 2000; Mardin 1969; Navaro-Yashin 2002; Ortayli 2007). This rapid development with the perspective of becoming a European Union member continues today.

While Western values and norms are at the center of social change and modernization in Turkey, majority of people have a collectivist background, holding Islamic beliefs and values of agricultural society. However, research shows that collectivist and individualist values (Goregenli 1997), and autonomy and unity go hand in hand in Turkey (Kagitcibasi 2007; Imamoglu 2003), and in some socio-cultural groups even dominance of individualism (Yetim 2003) is observed. For the majority of people in Turkey, individual talent, competence, achievement motivation, autonomy and self-management are central values (Demirutku 2000; Karakitapoglu and Imamoglu 2002; McClelland 1961). Especially the educated middle and upper class individuals, owing to the contribution of their material prosperity and economic development levels, individualistic values are highly shared. In lower-class groups, membership in non-governmental organizations based on informal solidarity networks is quite wide spread (White 1996). On the other hand, with the rising of individualistic values, there is an increasing tendency for individuals to become members of voluntary organizations and non-governmental organizations in order to meet their own interests. Parallel to the rising of religiousness in the world, a variety of religious communities, which emphasize religiousness on the one hand and yet support the secular system in Turkey, have emerged as actors in social life. In recent years, such religious economic pressure groups, and non-governmental organizations supporting women’s rights or the rights of ethnic and cultural groups have started to become more influential in social life (Adas 2006; Yavuz and Esposito 2003). Many researchers (e.g., Kazancigil 1991; Toprak 1996) stressed that Turkey has many free associations which are organized on the basis of shared experience, trust, and the bonds of reciprocity. White (1996) indicated that Turkey has a relatively strong civil society tradition in her region and the major components of this tradition are trust and reciprocity.

In light of these arguments, although Turkey is categorized as a non-Western and Eastern country, it is more likely for it to be categorized with Western societies in terms of social capital. Individuals are expected to use social capital, depicted with the dimensions of interpersonal trust and civicness, in order to achieve sense of community and individual well-being. Similar to Western countries, positive correlations between satisfactions of needs, social capital, sense of community and individual well-being are expected to be obtained. In other words, individuals meet their own needs on the basis of the compliance of the socio-economic and psychological values that the community, the region, or the city provides; and if these efforts are not sufficient for meeting their needs, they might rely on social capital via their social relationships, mutual trust, and civicness to obtain additional resources in Turkey.

4 Purpose of the Current Study

This study aims at analyzing needs fulfillments and social capital variables with regard to their impacts on SOC and individual well-being. In particular, the study tests a model where, social capital mediates the relationship between fulfillment of needs and the subjective well-being variables of sense of community and individual well-being. It is known that variables such as SOC, life satisfaction, and flourishing are studied mostly in Western societies and evidence related to these variables in non-western societies is much lesser (Qingwen et al. 2010). This study was conducted in Mersin, a dynamic city in Turkey—a country being a bridge between the East and the West, and blending the West’s and the East’s cultural values together but categorized like a non-western society and especially like an Eastern society—and shelters diverse people, which is also noteworthy. Mersin as a city provides an appropriate basis for studying the interrelationships between fulfillment of needs, social capital, sense of community, and individual well-being due to its economic and cultural development in recent years, and its multi-cultural, multi-religious and diverse societal structure. The current study propounds the importance of authentic cultures and cultural diversities, rather than creating dichotomist distinctions or generalizations such as Western versus non-Western.

5 An Example of the Formation of a City: Mersin

With its provincial population of 1,667,939; its town center population of 842,230; its foreign trade volume of 20, 9 billion dollars and Turkey’s second biggest free trade area, Mersin is an international port city in terms of its community features (TUIK 2011). Mersin holds 5 % of export and 6 % of import done in the first 3 months of 2012 year in Turkey. Contributing and adding value to Turkey’s economy with its tourism, agriculture, construction, logistics industries, Mersin has been allowing immigrants from the Eastern part of Turkey and has a cultural structure which brings different languages (Turkish, Arabic, Kurdish etc.), religions (Islam, Christian etc.) and cultural identities together. Mersin, with its multi-cultural society, incorporates a high number of civil society organizations. Majority of individuals that have immigrated to Mersin tend to initiate their own enterprises and businesses and contribute to the economic buoyancy of the city (Yetim 2008). As a result, entrepreneurship capacity of the city is exponentially proliferating.

6 Description of Study Variables

Sense of community and individual well-being are known to be influenced by several objective (e.g., city infrastructure, water and air purity, traffic, etc.) and subjective (e.g., mood, joy, personal experience, etc.) variables. The current study focuses on volitional behaviors of individuals and level of fulfillment of their needs. Fulfillment of needs and social capital have been proposed as antecedents of sense of community and individual well-being; and in particular social capital has been tested as a potential mediator of the relationship between fulfillment of needs and subjective well-being variables.

6.1 Fulfillment of Needs

Basic Needs: The degree of individuals’ satisfying their basic needs such as having an income, sheltering, and employment is conceptualized as part of this variable. The adequacy of individuals in meeting these needs is the point to be emphasized in this variable. That is, the opportunities of individuals and competencies at the individual or family level are important rather than evaluating these needs in general.

Educational Needs: The capacity of a society’s meeting its individuals’ and families’ educational needs in their communities and neighborhood has been studied as a part of this variable. In this respect, accessibility to educational sources that is situated in the living environment and quality and desirability, rather than overall number of schools and teacher, has been focused on.

Social Needs: The capacity of a society’s meeting its individuals’ socialization, solidarity, and recreation needs has been studied as a part of this variable. Individuals’ use of and access to these sources are regarded as fundamental aspects here again.

Health Needs: Accessibility to health sources by individuals when needed, rather than the number of beds and doctors in the city’s hospitals, has been studied as a part of this variable.

6.2 Social Capital

In this research, social capital has been conceptualized as having two dimensions: civicness and trust. Civicness includes not only individual’s voluntary participation in nongovernmental organizations in her/his city or residential area but also her/his relationship with local administrators, the capacity of creating a pressure group, and the conduct of voting in local elections.

A general evaluation regarding the community members in terms of trust is not the only thing targeted. It is acknowledged that there are three sub-groups of trust perception as evaluations- a general evaluation, strong ties evaluation, and weak ties evaluation. As part of these three sub dimensions, trust judgments on a number of connection networks such as family, immediate vicinity, nongovernmental organizations, local administrators, local government along with global trust evaluation are conceptualized under a single factor.

6.3 Sense of Community

It is acknowledged that SOC is composed of individuals’ overall and specific residential satisfactions related to their cities. It is predicted that individuals develop a SOC in two different ways, one being general evaluation of their cities and the other one being specific evaluation of various sub domains.

6.4 Individual Well-being: Life Satisfaction and Flourishing

This study also investigates the life satisfaction of individuals and their individual development as output variables. It is known that life satisfaction is a global evaluation of one’s life as a whole. Overall evaluations and judgments of individuals’ on their lives are examined in the scope of this perception. Evaluations and judgments regarding individual development are also included in the scope of flourishing.

This study has focused on the cognitive dimension of individual well-being. Assessment of need satisfaction and social capital requires evaluation, judgment, and decision-making in these subjects. Therefore, assessment of individual well being was also based on one’s evaluation of general and specific aspects of his/her own life.

7 The Proposed Conceptual Model

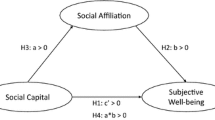

This study aims at investigating whether fulfillments of individuals’ needs and social capital predict individual well-being; as life satisfaction and flourishing; and SOC; as overall and specific residential satisfaction. The model in which the fulfillment of general needs- fulfillments of basic, health, educational and social needs- predict SOC and individual well-being through social capital- civicness and trust- is presented below.

The conceptual model

The conceptual model proposed  .

.

8 Method

In this part, information on the processes of research, features of the study sample, validity and reliability of the scales used, and data analysis is provided.

8.1 Sample

Participants of the study are people living in the city center of Mersin, which has been divided into four counties as Akdeniz, Toroslar, Yenişehir, and Mezitli. The population of the city center of Mersin is 842,230 as of year 2011 (TUIK 2011). The distribution of the population according to county’s magnitude is as follows; Akdeniz 284,333; Toroslar 251,838; Yenişehir 186,967; and Mezitli 119,092. At these rates of distribution, the sample has been determined by virtue of stratified random sampling. Thus, a total of 677 participants including 322 women and 350 men ranging in age from 17 to 78 and residing in the above mentioned four central counties of Mersin have participated in the study. The demographic features of the sample are presented below (Table 1).

8.2 Measures

8.2.1 General Needs Scale

The scale has been developed by researchers in order to evaluate the degree of individuals’ meeting their basic, health, social, educational needs. General Needs Scale assessed with a 5-point (1: Totally disagree—5: Totally agree) Likert-type scale is composed of 17 items. There are 6 items concerning the basic needs in the scale. There are phrases such as “I can find a job easily in the city that I live in”, “I can buy a house easily in the city that I live in” and “I can utilize public transportation service easily and seamlessly in the area that I live in” as examples of these items. There are 4 items concerning health needs in the scale. These are like “I can access to paramedics (doctor, psychologist, nurse, midwife, etc.) easily in the vicinity that I live in”, “I can utilize ambulance service without any delay in case of emergencies in the city that I live in”, “Health screening and hygiene services are provided regularly in the vicinity that I live in.” There are three items concerning educational needs in the scale. These are like “I can school my child easily in the vicinity or neighborhood that I live in”, “I can get education in the universities and academies easily in the city I live in or my children can”, “I can get additional training support (courses, summer camp, etc.) for my child from local and institutional training institutions when required.” There are 4 items concerning social needs in the scale. These are, “I can have access to cultural activities of the city as museum, theatre, concert easily”, “There are places where I can have fun with my friends in my city, and I can utilize them easily”, “There are places as greenery space and parks in the vicinity that I live in, and I can utilize them easily”, “There are places where I can do exercise in the vicinity that I live in, and I can utilize them easily”. In order to test the validity of the scale and determine its factor structure, principle component analysis with Varimax rotation has been conducted. The results indicated a 4-factor structure. Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin value which is obtained from KMO Bartlett test was found as .75. This indicates that the variance explanation of factors is sufficient. Accordingly, first factor (health) by itself explained 23.21 % of the total variance, second factor (social) by itself explained 18.09 % of the total variance, third factor (basic needs) by itself explained 15.81 % of the total variance, and forth factor (education) by itself explained 14.85 % of the total variance; all factors explaining 71.98 % of the total variance. As the first factor, health factor has .66; as the second factor, social factor has .75; as the third factor, basic needs factor has .68; as the forth factor, education factor has .72 Cronbach’s Alpha value. These findings indicate that General Needs Scale ensures reliability and validity.

8.2.2 Civicness Scale

The scale has been developed by the researchers in order to evaluate the degree of civicness of individuals. Civicness Scale included a 5-point Likert-type scale (1:Totally disagree—5: Totally agree) and was composed of 6 items. Items are “I can access to local administrators easily when needed”, “I can put my petition into process in relevant authority easily when required”, “I donate money to various charities” “I volunteer for organizations as association, union which attracts my attention”, “I vote regularly in general and local elections”, “I read local newspapers, and I watch local television channels regularly.” In order to test the validity of the scale, principle component analysis with Varimax rotation has been conducted. As a result, all of the 6 items gathered under a single factor and this factor explained 59 % of the total variance. In the analysis that has been conducted to evaluate the scale’s reliability, a Cronbach’s Alpha value of .76 has been found.

8.2.3 Trust Scale

The scale has been developed by the researchers in order to evaluate the degree of confidence of individuals towards people who are around them. The scale is composed of items that are able to assess strong and weak ties, and overall aspect of trust. Trust Scale is composed of 10 items assessed on a 5-point Likert type scale (1: Totally disagree—5: Totally agree). Phrases such as “I generally trust people”, “I trust my family”, “I trust people from Mersin”, “I trust nongovernmental organizations in Mersin”, “I trust local administrators in Mersin” can be given as examples. In order to test the factorial structure of the scale, principle component analysis with Varimax rotation has been conducted. Ten items loaded under a single dimension, and it has been observed that a single factor explained 58 % of the total variance. The internal consistency of the Trust Scale was .82. These results indicate that Trust Scale is valid and reliable.

8.2.4 Sense of Community

In this research, SOC has been evaluated by using Residential Life Satisfaction Scale. Residential Life Satisfaction Scale has been developed by Bilgin (1995) in order to evaluate individual’s overall and specific residential satisfaction. Residential Life Satisfaction Scale is totally composed of 15 items of which 10 items evaluate special residential satisfaction and 5 items evaluate overall residential satisfaction based on a 7-point Likert type (1: Totally disagree—7: Totally agree) evaluation. “My city is similar to my ideal city in many aspects”, “My city has most of the important things that a person would want”, “I think my city is better than other similar cities in Turkey” can be given as examples of overall residential satisfaction items. “I feel as a part of this city”, “I think that my city is well-ordered and organized” “I feel safe in my city” are examples of the specific residential satisfaction part of the scale. In order to test structure validity of the scale and to determine the factor structure, principle component analysis with Varimax rotation has been conducted by using a sample of 150 adults. The results indicated a 2-factor structure. Accordingly, the first factor (overall residential satisfaction) explained 26.09 % of the total variance, whereas the second factor (specific residential satisfaction) explained 25.74 % of total variance, and the both factors together explained 51.83 % of the total variance. Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin value which is obtained from KMO Bartlett test was found .90. This indicates that the variance explanation of factors is sufficient. In order to obtain the convergent validity of Residential Life Satisfaction Scale, a correlation analysis between the average score of this scale and the average score of Satisfaction with Life Scale has been conducted. A moderate correlation value of .54 between the two scales has been found. The reliability value of the scale is .86 Cronbach’s Alpha (.87 for overall and .84 for special). These results indicate that the scale is valid and reliable.

8.2.5 Flourishig Scale

We used the Flourishing Scale developed by Diener et al. (2010). Flourishing Scale is composed of 8 items assessed on a 7-point Likert type (1: Totally disagree—7: Totally agree) scale. Diener et al. (2010) has found that temporal stability of the scale is .71 and Cronbach’s Alpha is .87. They also found that flourishing scale correlated strongly with the summed scores for other psychological well-being scales (r = .78 and .73). Telef (2011) adapted this scale into Turkish and found that flourishing scale’s temporal stability is .86 and Cronbach’s Alpha is .80. In his study, Telef (2011) also found some support for its validity. He has found that the only one factor explains 41.9 % of the total variance in his confirmatory factor analysis, factor loadings of items varying from .54 to .76. His confirmatory factor analysis showed that the goodness of fit index values were RMSEA = 0.08; SRMR = 0.04; GFI = 0.96; NFI = 0.94; RFI = 0.092; CFI = 0.95; and IFI = 0.95. In the relevant study, the scale has been found to highly correlate with other psychological well-being scales. The reliability of this scale has been found to be .75 (Cronbach’s Alpha value) in our study.

8.2.6 The Satisfaction with Life Scale

The satisfaction with life scale (SWLS) is developed by Diener et al. (1985). SWLS is a self-report measure composed of 5 Likert type items assessed on a scale ranging from (1) not appropriate at all to (7) appropriate exactly. Diener and his colleagues found the reliability of the scale as .87 in the original study. They obtained criterion-related validity as .82 (Pavot et al. 1991). The reliability of the scale has been found to be high (Cronbach’s Alpha = .86) by Yetim (1993, 2003), adapting the scale to Turkish. Çetinkaya (2004) has found the convergence validity of the Satisfaction with Life Scale for two separate scales as .33 and .40. The results indicate that the Satisfaction with Life Scale has high reliability and moderate validity from the point of individuals in our country. The reliability of this scale is .88 in the current study.

9 Findings

In this section, the correlation coefficients between study variables and statistical findings on the tested model are presented. As can be seen in the correlation table (Table 2), the correlation coefficients among all of the variables are statistically significant. Fulfillments of need variables have significant relationships among themselves. For example, fulfillment of health needs correlate with fulfillments of social needs at the level of .30; fulfillments of basic needs at the level of .32; fulfillments of educational needs at the level of .32. Fulfillments of social needs correlate with fulfillments of basic needs approximately at the level of .26; fulfillments of educational needs approximately at the level of .35. The significant relationship between fulfillments of basic needs and fulfillments of educational needs is at the level of .24.

The correlations between fulfillment of needs variables and variables of social capital are significant. Civicness correlate with fulfillments of health needs approximately at the level of .27; fulfillments of social needs approximately at the level of .27; fulfillments of basic needs approximately at the level of .19; and fulfillments of educational needs at the level of .24. The correlation coefficient of trust with fulfillments of health needs is at the level of .20; with fulfillments of social needs is at the level of .25; with fulfillments of basic needs is at the level of .17; and with fulfillments of educational needs is at the level of.18.

There are moderate but significant correlations between fulfillments of need variables and SOC variables. The correlation of special residential satisfaction with fulfillments of health needs is.34; with fulfillments of social needs is .30; with fulfillments of basic needs is .42; and with educational needs is at the level of .38. As it has been found, the correlation coefficient of overall residential satisfaction with fulfillments of health needs is .29; with fulfillments of social needs is .39; with fulfillments of basic needs is .40; and with fulfillments of educational needs is approximately .35. The correlation coefficients that have been found between variables of fulfillments of needs and individual well-being are significant. Accordingly, the correlation coefficient of flourishing with fulfillments of health needs is approximately at the level of .28; with fulfillments of social needs is approximately at the level of .29; with fulfillments of basic needs is approximately at the level of .27; and with fulfillments of educational needs is approximately at the level of .23. The correlation coefficient of life satisfaction with fulfillments of health needs is approximately at the level of .27; with fulfillments of social needs is at the level of .22; with fulfillments of basic needs is at the level of .16; and with fulfillments of educational needs is at the level of .28. Variables of social capital (civicness and trust) have moderate significant correlation (.35) between themselves. Civicness has significant correlation coefficients with variables of SOC. Accordingly, the correlation coefficient of civicness with special residential satisfaction is .24; with overall residential satisfaction is .25. The correlations between trust and variables of SOC are moderate. Accordingly, the correlation coefficient of trust with special residential satisfaction is approximately .39; with overall residential satisfaction is approximately .33. The correlation coefficients that have been found between variables of social capital and individual well-being are moderate. The significant correlation coefficient of civicness with flourishing is approximately .37, with life satisfaction is .38; and the significant correlation coefficient between trust and flourishing is .37, the significant correlation coefficient between trust and life satisfaction is .36.

The correlation coefficients between variables of SOC and individual well-being are moderate and significant. Accordingly, the correlation of special residential satisfaction with flourishing is .39, with life satisfaction is .38, whereas the correlation of overall residential satisfaction with flourishing is approximately .42, with life satisfaction is approximately .38. The correlation coefficient between special residential satisfaction and overall residential satisfaction has been obtained to be high (.71) and the correlation coefficient between flourishing and life satisfaction has been obtained to be moderate (.59).

10 Analysis of the Model: Structural Equation Modeling

In order to test the model proposed, structural equation modeling technique has been carried out by using Lisrel 8.51 program. There are some methods to test structural equation modeling. (1) Being an original equation model, path analysis which focuses on the relationships between observed variables, is one of the methods. (2) Confirmatory factor analysis, identified as a latent variable, is another method to be used in testing factor loading of items. (3) Structural equation modeling combines path analysis and factor analysis. This technique points out the relationship among latent structures, generally focusing on the analysis (Tabachnick and Fidell 2001).

For testing the relationships among the variables in a structural equation model, a two-step procedure is followed as suggested by Anderson and Gerbing (1988). In the first step, a measurement model is estimated, which excludes the paths/relationships between the latent variables. The measurement model is informative for assessing the measurement properties of the indicators and for examining how well the latent constructs are assessed by the observed indicators. In the second step, the relationships between the latent variables are also included in the model, and the strength of the relationships is tested.

Structural equation modeling has certain fit statistics showing the extent to which the data fits with the tested model. Given in the end of the analysis output, fit statistics are required to be above or below certain values. The basic fit statistic is the Chi square. In order for a model to be acceptable, it is required for the Chi square value not to be significant, because in structural equation studies, a difference between data and theoretical expectations is required. Therefore, H0 and H1 hypotheses are stated in an opposite way of conventional analysis in structural equation modeling. The increase in Chi square value, points at devolving of model fit. In other words, when Chi square value increases, it indicates that the fit of the data to the model proposed is not good. Many fit statistics have been produced except Chi square. Among the most commonly used ones are RMSEA, GFI, AGFI, and CFI. RMSEA is root mean square of error approximation. RMSEA values below .05 indicate a good fit; an RMSEA values between .05 and .08 indicate a moderate fit whereas any value above .10 indicate poor fit. The other fit indices are GFI (goodness of fix index), AGFI (adjusted goodness of fix index), CFI (comparative fix index). All of these values range from 0 and 1.0. The values above .90 indicate an acceptable goodness of fix value; the values above .95 also indicate a good goodness of fix (Tabachnick and Fidell 2001).

Following Anderson and Gerbing’s (1988) suggestions, the measurement model including “general needs”, “social capital”, “sense of community”, and “individual well-being” as latent variables has been tested first. It is assumed that the latent variable of “general needs” is composed of fulfillments of basic, health, social, and education needs, and our model proposes that the latent variable of fulfillment of needs predicts the latent variable of “social capital” composed of civicness and trust variables. Moreover, the variable of “social capital” predicts the latent variable of “sense of community” composed of special and overall residential satisfaction and the latent variable of “individual well-being” composed of life satisfaction and flourishing variables. Fit indices for the measurement model has revealed satisfactory fit with the data, therefore the structural model has been tested in the second step with the inclusion of relationship paths between the latent variables under investigation. The structural model was a full mediation model, where social capital mediated the relationship between fulfillment of needs and the outcome variables of sense of community and individual well-being. The resulting goodness of fit statistics for the structural model reveal that our model has adjusted to the data very well (χ2 (31) = 74.38, p = .000, χ2/df = 2.39, AGFI = 0.946, GFI = 0.973, CFI = 0.965, AIC = 122.328, RMSEA = 0.055). The results of the analysis indicate that there is a positive and direct relationship (β = 0.70, t = 8.43, p < .01) between general needs and social capital. They also indicate the existence of a positive and direct relationship between social capital and sense of community (β = .83, t = 8.72, p < .01), and between social capital and individual well-being (β = 0.87, t = 9.17, p < .01). The relevant values are presented in Fig. 1.

Additionally a partial mediation model was also tested in order to identify the exact nature of the mediation. This partial mediation included fulfillment of general needs as having direct effects on social capital, sense of community and individual well-being, and social capital having direct effects on sense of community and individual well-being. Resulting fit indices of the partial model indicated satisfactory fit with the data and a small improvement (decrease) in the Chi square value, therefore a Chi square difference test was carried out in order for testing whether the identified mediation was full or partial. The difference in Chi square (0.07) was smaller than the critical value (3.84), and thus was found to be nonsignificant (p > .05).

Overall, these findings indicated support for the proposition of our study concerning the meditational role of social capital in the relationship between general needs and well-being indicators. Moreover, social capital was found to act as a full mediator. The fit indices for the measurement and structural models are summarized in Table 3.

In order to assess if a direct effects model can explain the relationships between the study variables to the same extent as in the mediation model a supplementary analysis was conducted. For this purpose, a final model was tested where fulfillment of needs have direct effects on social capital, sense of community and individual well-being. However, there was a decline in the resulting fit indices, indicating a moderate fit with the data (χ2 (32) = 111.50, p = .00, χ2/df = 3.48, AGFI = 0.92, GFI = 0.96, CFI = 0.97, AIC = 157.50, RMSEA = 0.073). This supplementary analysis also pointed out that the meditational model identified in the current study provided a better account of the nature of associations between the study variables.

11 Discussion

This study focused on analyzing the relationships among fulfillment of needs, social capital, sense of community, and individual well-being in a cultural, non-Western and original context. The model proposed in this study, in which fulfillments of needs predict the sense of community and individual well-being through social capital, has been validated. Among competing structural equation models, the full mediation model was found to have best fit with the data, pointing out social capital as fully mediating the relationship between fulfillment of needs and subjective well-being. These results indicate that fulfillment of needs within the context of Mersin precedes social capital, and social capital predicts sense of community and individual well-being to a significant extent.

The structural equation model revealed a significant and strong relationship between needs and social capital. Hence, we can remark that social capital functions as an additional source in individual’s fulfillments of needs. Individuals consult their social capital so as to let up their bothers in meeting their basic, health, educational and social needs in their own neighborhood through civicness and trust. For example, a social campaign against the in coordination in meeting health services can be launched with other citizens; a pressure on local administrators can be applied or non-governmental organizations can be activated. Based on mutual trust relationships and through collective actions, individuals can create new socialization areas in the city and such areas can contribute to satisfaction of social needs. All of these activities make social capital as civicness essential. Trust plays a key role in fulfillments of needs. Trusting relevant institutions and administrators, and the city in general is highly important in the perception of satisfaction. In summary, as an additional source, trust relationship and positive connections that an individual establishes with her/his community, contributes to fulfillment of needs. Sirgy (2011) indicates that high or low level of fulfillment of need leads to human development, and human development leads to life quality. We think that human development should include social flourishing, positive connections with community. It seems necessary that capacity of meeting needs of a community’s citizens should be in the background of individuals’ trust in their family, relatives, neighbors, citizens, and non-governmental organizations. In other words, the sources that increase the capacity of meeting needs individually and as a group, feed with social relationship of individuals and sense of trust obtained from these relationship. The findings obtained support the existence of this socio-cultural environment. Consequently, the pattern of relationships between general need fulfillment, social capital, sense of community, and individual well being that have been identified for Mersin are parallel to those in developed Western countries, despite the authentic and original aspects of the economic and cultural structure of this city. Future studies on social capital structures peculiar to Turkey, such as informal civic associations, reciprocal trust relations, religion-oriented mass organizations, women’s organizations (Toprak 1996; White 1996), and their relations with needs fulfillment and subjective well-being are needed. The present study is encouraging for future studies as a pioneer in portraying the current state of affairs with regard to the topic of interest.

Social capital has been found to predict sense of community intensely (.83). In other words, sources of social capital (civicness and trust) predict their special and overall residential satisfactions. Hence, the individuals living in Mersin who think themselves as a part of their city and evaluate their city positively with its special and general aspects, appear to have the capacity of financial, social, administrative relationships and these individuals are those that are better able to meets their needs. The people living in Mersin, trust other citizens and institutions more; and make their trust relationships into resources; and have more weak and strong connections. These findings correspond with most of the findings in literature. For example, Hudson (2006) has found evidence between trust in institutions and people’s well-being. Moreover, Leung et al. (2011) points out to a strong connection between sense of community and sources of social capital including trust and connections. Our study has been the first to present these associations among these variables in a country like Turkey, having original values of non-Western societies.

Social capital was found to predict individual well-being (.87) intensely. Individuals having higher levels of social capital also had higher life satisfaction and flourishing levels. Besides, the social capital which these individuals form in this city not only contributes to fulfillment of needs, but also reveals civicness and sense of trust. This study verifies previous findings about the relationship between meeting needs and well-being (Diener and Diener 1995; Tay and Diener 2011; Veenhoven 1993), and the findings related to positive connection between social capital and well-being (Bjornskov 2003; Diener and Tov 2007; Dolan et al. 2008). The reason why this study is original is that, civicness, democratic behaviors and sense of trust of individuals in their informal and formal connections both serves as a mediator in meeting needs by themselves and can predict subjective and psychological well-being in a non-Western cultural context. As mentioned briefly, Turkey is the only Muslim-majority society in her neighborhood to have a democracy tradition, and citizens that can form a pressure group, and individuals that have determination for implementation of their own demands. The improvement of democracy in Turkey has made breakthroughs related to civil society recently. These breakthroughs considerably contribute to improving her own democracy as well as having a powerful and sensitive civil society. Furthermore, perspective of Turkey in EU membership has had an accelerating effect on these developments. Turkey is an economically developing country. As it is mentioned before, Mersin is a city making a significant contribution to this development. All of these economic development and democratic breakthroughs give rise to the extension of freedoms and individual rights besides individualist values in socio-cultural values. It is mentioned that rates of individualistic and collectivist values are equal, and even the individualistic values have been shown to be dominant in some studies in the literature, especially in middle and upper class societies in Turkey, that used to have a history of collectivist tendency as the dominant culture (Yetim 2003). The findings obtained in the current study indicate that some collectivistic values such as reciprocal relations, informal associations are also important in the trust of individuals in civicness and societies. A city like Mersin where various ethnic, religious and cultural groups live together, these diverse communities are involved in civil life with their collective identities and take part in activities on behalf of their own groups. In conclusion, individuals in Mersin, which has been developing rapidly and has diversifying and increasing resources, make their chance of meeting their needs possible through individualistic and some collective connections; the individualistic and some of collective connections possessed strengthen the sense of trust in the society. All of these features predict both sense of community and individual well-being. In summary, these improvements related to Turkey and Mersin can be said to make the findings obtained meaningful. Reconsidering the tested model within the scope of ethnic and religious groups makes it possible to talk clearer about the subject.

In light of the study findings, it can be said that fulfillment of general needs increases the likelihood of increased levels of social capital, which in turn results in increased levels of flourishing and well-being. In this process, social capital might be serving as an effective tool in generating new opportunities for individuals to further meeting their psychological needs such as autonomy, relatedness, and competence. Hence, future studies are needed to actually measure psychological need satisfaction that results from social capital. Our study was the first to demonstrate the mediating role played by social capital. Moreover, it proved that the pattern of relationships among subjective well being and its antecedents are also valid within the authentic cultural context of Mersin.

In this study sense of community was assessed through residential satisfaction. A self-report scale, in which various features of society and habitat as well as general sentiment concerning society and habitat are judged, has turned out to be an appropriate scale for assessing sense of community among various scaling types. It has been found that sense of community measured in this study and in this state has been predicted intensely by the fulfillment of needs and social capital. This study should be retested in similar or different cultures and contexts with the same rational and method or improved ones, which is crucially important for making generalization of the findings.

Besides its strengths, this study is not without limitations. Since the study findings were based on cross-sectional data, we cannot conclude any cause-and-effect associations between the study variables. Therefore, the pattern of associations with respect to the placing of the variables (general needs—social capital—well-being) in the pseudo-causal chain was rather derived from logical and rational inference. A second limitation of the study is concerned with the self-report nature of the data. All of the data on different variables were collected from the same source and thorough a questionnaire package. Therefore, some part of the relationships between the study variables might be due to common method variance.

With regard to the correlations among study variables, particular pairs of variables had significant but weak correlations, which need to be further explored. For example, weak correlations have been observed between civicness and basic needs fulfillment (r: .19), trust and fulfillment of basic needs (r: .17) and fulfillment of educational needs (r: .18). This indicates significant but weaker than expected relationships between fulfillment of needs and individuals indicators of social capital. It might be the case that individuals rely on personal resources, rather than civicness and trust, for meeting basic and educational needs. On the other hand, one potential explanation for these weak correlations might be due to the structure of the scales used in the study. The general needs scale, civicness scale, and trust scale were newly developed for the purposes of this study. This might be suggested as the third limitation of the present study. While our scales have proved to have high internal consistencies, they have not been used in any other studies and they need to be further tested in other cultures future studies.

In our study individual and psychological well-being has been predicted intensely by fulfillment of needs and variables of social capital. In particular, social capital was found to fully mediate the influences of general need fulfillment on subjective well-being. In other words, individuals that meet their low and high needs in their neighborhood were more likely to trust their neighborhood and establish positive networks with this neighborhood, and in turn they made better psychological adjustments and had much more opportunities as they get support in the satisfaction of the incentives of competence, autonomy and relatedness. These individuals enjoy life satisfaction in general. The point to be emphasized is that these findings are significant in a cultural structure like Turkey, hosting collectivist and individualistic values together and this should be tested in other cultural structures in future studies.

References

Adas, E. B. (2006). The making of entrepreneurial Islam and the Islamic spirit of capitalism. Journal for Cultural Research, 10, 113–137.

Allik, J., & Realo, A. (2004). Individualism-collectivism and social capital. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 35, 29–50.

Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103, 411–423.

Andrews, F. M., & Withey, S. B. (1976). Social indicators of well-being. New York: Plenum Press.

Beem, C. (1999). The necessity of politics: Reclaiming American public life. Chicago, IL: Chicago University Press.

Berkes, N. (1998). The development of secularism in Turkey. New York: Routledge.

Bilgin, N. (1995). Sosyal psikolojide yöntem ve pratik çalışmalar. Istanbul: Sistem Yayıncılık.

Bjornskov, C. (2003). The happy few: Cross-country evidence on social capital and life satisfaction. Kylos, 56, 3–16.

Bourdieu, P. (1986). The forms of capital. In G. Richardson (Ed.), Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of eduction (pp. 241–258). New York: Greenwood.

Brodsky, A. E., & Marx, C. M. (2001). Layers of identity: Multiple psychological sense of community within a community setting. Journal of Community Psychology, 29, 161–178.

Campbell, A. (1981). The sense of well-being in America. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Çetinkaya, H. (2004). Beden İmgesi, Beden Organlarından Memnuniyet, Benlik Saygısı, Yaşam Doyumu ve Sosyal Karşılaştırma Düzeyinin Demografik Değişkenlere Göre Farklılaşması, Mersin Üniversitesi, Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü, Yayınlanmamış Yüksek Lisans Tezi (Differences of body image, satisfaction, self esteem, life satisfaction, and social comparison variables according to some demographic variables). Unpublished master’s thesis, Mersin University, Mersin.

Chipuer, H. M., & Pretty, G. M. (1999). A review of sense of community index: Current uses, factor structure, reliability, and further development. Journal of Community Psychology, 27, 643–658.

Coleman, J. S. (1988). Social capital in the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology, 94, 95–120.

Demirutku, K. (2000). Influence of motivational profile on organizational commitment and job satisfaction: A cultural exploration. Unpublished master’s thesis, Middle East Technical University, Ankara.

Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 95, 542–575.

Diener, E., & Diener, C. (1995). The wealth of nations revisited: Income and quality of life. Social Indicators Research, 36, 275–286.

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 71–75.

Diener, E., & Suh, E. (1997). Measuring quality of life: Economic, social, and subjective indicators. Social Indicators Research, 40, 189–216.

Diener, E., & Tov, W. (2007). Subjective well-being and peace. Journal of Social Issues, 63, 421–440.

Diener, E., Wirtz, D., Tov, W., Kim-Prieto, C., Choi, D., Oishi, S., et al. (2010). New well-being measures: Short scales to assess flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Social Indicators Research, 97, 143–156.

Dolan, P., Peasgood, T., & White, M. (2008). Do we really konow what makes us happy? A review of the economic literature on the factors associated with subjective well-being. Journal of Economical Psychology, 29, 94–122.

Etzioni, A. (1993). The sprit of community. The reinvention of American society. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Etzioni, A. (1996). The new golden rule: Community and morality in a democratic society. New York: Basic Books.

Fukuyama, F. (2001). Social capital, civil society and development. Third World Quarterly, 22, 7–20.

Goregenli, M. (1997). Individualist-collectivist tendencies in a Turkish sample. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 28, 787–794.

Hudson, J. (2006). Institutional trust and subjective well being across the EU. Kylos, 59, 43–62.

Igarashi, T., Kashima, Y., Kashima, E. S., Farsides, T., Kim, U., Strack, F., et al. (2008). Culture, trust, and social networks. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 11, 88–101.

Imamoglu, E. O. (2003). Individuation and relatedness: Not opposing, but distinct and complementary. Genetic, Social, and General Psychology Monographs, 129, 367–402.

Inalcik, H., & Quataert, D. (Eds.). (1994). An economic and social history of the Ottoman Empire, 1300–1914. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Inglehart, R., & Baker, W. E. (2000). Modernization, cultural change, and the persistence of traditional values. American Sociological Review, 65, 19–51.

Kagitcibasi, C. (2007). Family, self, and human development across cultures. Theory and applications. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Karakitapoglu, Z. A., & Imamoglu, E. O. (2002). Value domains of Turkish adults and university students. The Journal of Social Psychology, 142, 333–351.

Karpat, K. H. (Ed.). (2000). Ottoman past and today’s Turkey. Leiden: Brill.

Kazancigil, A. (1991). Democracy in Muslim lands: Turkey in comparative perspective. International Social Science Journal, 128, 343–360.

Krueger, R. F., Hicks, B. M., & McGue, M. (2001). Altruism and antisocial behavior: Independent tendencies, unique personality correlates, distinct etiologies. Psychological Science, 12, 397–402.

Leung, A., Kier, C., Fung, T., & Fung, L. (2011). Searching for happiness: The importance of social capital. Journal of Happiness Studies, 12, 443–462.

Long, A. D., & Perkins, D. D. (2003). Confimatory factor analysis of the sense of community index and development of a brief SCI. Journal of Community Psychology, 31, 279–296.

Mankowski, E., & Rappaport, J. (1995). Stories, identity, and psychological sense of community. In Wyer, Jr R. S. (Ed.), Knowledge and memory, the real story. Advances in social cognition, pp. 211–226. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Mankowski, E., & Rappaport, J. (2000). Narrative concepts and analysis in spritually-based communities. Journal of Community Psychology, 28, 479–493.

Mardin, S. (1969). Power, civil society and culture in the Ottoman Empire. Comparative Studies in Society and History, 11, 258–281.

Mardin, S. (1992). Turk modernleşmesi (Turkish modernization). Istanbul: Iletisim.

Mardin, S. (2000). The genesis of Young Ottoman thought: A study in the modernization of Turkish political ideals. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

McClelland, D. (1961). The achieving society. Princeton, NJ: D.Van Nostrand Company.

McMillan, D., & Chavis, D. M. (1986). Sense of community: A definition and a theory. Journal of Community Psychology, 14, 6–23.

Navaro-Yashin, Y. (2002). The market commodities: Secularism, Islamism, commodities. In D. Kandiyoti & A. Saktanber (Eds.), Fragments of culture (pp. 221–253). New Brunswich, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Obst, P., Smith, S. G., & Zinkiewicz, L. (2002). An exploration of sense of community, part 3: Dimensions and predictors of psychological sense of community in geographical communities. Journal of Community Psychology, 30, 119–133.

Ortayli, I. (2007). Batililasma yolunda (On the road of Westernization). Istanbul: Merkez Kitapcilik.

Pavot, W., Diener, E., Colvin, C. R., & Sandvik, E. (1991). Further validation of the satisfaction with life scale : Evidence for the cross-method convergence of well-being measures. Journal of Personality Assessment, 57, 149–161.

Paxton, P. (1999). Is social capital declining in the United States? A multiple indicator assessment. American Journal of Sociology, 105, 88–127.

Pooley, J. A., Cohen, L., & Pike, L. T. (2005). Can sense of community inform social capital? The Social Science Journal, 42, 71–79.

Portes, A. (1998). Social capital: Its origins and applications in modern sociology. Annual Review of Sociology, 24, 1–25.

Putnam, R. D. (1993). The prosperous community: Social capital and public life. American Prospect, 13, 35–42.

Putnam, R. (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Putnam, R., Leonardo, R., & Nanetti, R. (1993). Making democracy work: Civic traditions in modern Italy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Qingwen, X., Perkins, D. D., & Chow, J. C.-C. (2010). Sense of community, neighboring, and social capital as predictors of local political participation in China. American Journal of Community Psychology, 45, 259–271.

Realo, A., Annik, J., & Greenfield, B. (2008). Radius of trust: Social capital in relation to familism and institutional collectivism. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 39, 447–462.

Rostila, M. (2011). The facets of social capital. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 41, 308–326.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classical definitions and new directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25, 54–67.

Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness is everything or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 1069–1081.

Sarason, S. B. (1974). The psychological sense of community: Prospects for a community psychology. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Sirgy, M. J. (2011). Theoretical perspectives guiding QOL indicator projects. Social Indicators Research, 103, 1–22.

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2001). Using multivariate statistics (4th ed.). Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Tay, L., & Diener, E. (2011). Needs and subjective well-being around the World. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101, 354–365.

Telef, B. B. (2011). The validity and reliability of the Turkish version of psychological well-being. Paper presented at the National Congress of Counseling and Guidance, October, 3–5, Selcuk-Izmir, Turkey.

Thoits, P. A., & Hewitt, L. N. (2001). Volunteer work and well-being. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 42, 115–131.

Toprak, B. (1996). Civil society in Turkey. In A. R. Norton (Ed.), Civil society in the Middle East (Vol. 2, pp. 87–118). Leiden: Brill.

Tov, W., & Diener, E. (2008). The well-being of nations: Linking together trust, cooperation, and democracy. In B. A. Sullivan, M. Snyder, & J. L. Sullivan (Eds.), Cooperation: The political psychology of effective human interaction (pp. 323–342). Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

Triandis, H. C. (1995). Individualism and collectivism. Boulder, CO: Westview.

Turkish Statistical Institute-TUIK. (2011). Address based population registration system results. Ankara: TUIK Publication.

Uslaner, E. M. (1999). Democracy and social capital. In M. E. Warren (Ed.), Democracy and trust (pp. 121–150). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Veenhoven, R. (1993). Happiness in nations: Subjective appreciation of life in 56 nations 1946–1992. Rotterdam: RISBO.

White, J. B. (1996). Civic culture and Islam in urban Turkey. In C. Hann & E. Dunn (Eds.), Civil society: Challenging western models (pp. 141–163). London: Routledge.

Yamagashi, T., & Yamagashi, M. (1994). Trust and commitment in the United States and Japan. Motivation and Emotion, 18, 129–166.

Yavuz, M. H., & Esposito, J. L. (Eds.). (2003). Turkish Islam and the secular state. The Gulen Movement. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press.

Yetim, U. (1993). Life satisfaction: A study based on the organization of personal projects. Social Indicators Research, 29, 277–289.

Yetim, U. (2001). The happiness scenes: From society to individual (in Turkish). İstanbul: Baglam.

Yetim, U. (2003). The impacts of individualism/collectivism, self-esteem and feeling of mastery on life satisfaction among the Turkish university students and academicians. Social Indicators Research, 61, 297–317.

Yetim, N. (2008). Social capital in female entrepreneurship. International Sociology, 23, 864–885.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yetim, N., Yetim, Ü. Sense of Community and Individual Well-Being: A Research on Fulfillment of Needs and Social Capital in the Turkish Community. Soc Indic Res 115, 93–115 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-012-0210-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-012-0210-x