Abstract

This study examined gender differences in the influence of marital status and marital quality on life satisfaction. The roles of intergenerational support and perceived socioeconomic status in the relationship between marriage and life satisfaction were also explored. The analysis was conducted with data from the Chinese General Social Survey (CGSS) in 2006, representing 1,317 women and 1,152 men at least 25 years old. Chi-squared tests and logistic regression models were used in this process. Marriage, including marital status and relationship quality, has a protective function for life satisfaction. Marital status is more important for males, but marital quality is more important for females. The moderating roles of intergenerational support and perceived socioeconomic status are gender specific, perhaps due to norms that ascribe different roles to men and women in marriage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Due to higher baby girl mortality and the sustained nationwide abnormal sex ratio at birth, the gender structure in China is out-of-balance. As a consequence, a great number of males can’t find brides when their cohorts enter the marriage market. A prediction based on the census data of 2,000 showed that the number of males squeezed in the marriage market would reach far above 30 million (Klasen and Wink 2002). If the re-marriage market is taken into consideration, surplus males in the marriage market every year will number 1.2 million (Li et al. 2006). In addition, under the rule of marrying up and patriarchal culture, socioeconomic status (SES) is the key for men to get married, and men with higher SES have a broad range for their matching choice. On the contrary, good looks and age rather than SES determine women’s competitiveness in the marriage market, and those women with higher SES who have often devoted themselves to career development and are over a certain age have less chance to find single men better off than they are. As a result, those females in modern cities with higher SES, namely surplus women, are also squeezed in the marriage market, which further increases imbalance in the gender structure (Wei and Zhang 2010). Thus forced singlehood is expected to become a basic feature of social structure in China. What happens to the life satisfaction of these forced bachelors and surplus women? Is the benefit of marriage different for Chinese forced single persons in comparison with voluntarily unmarried people in western countries, and are gender differences due to gender role division and the availability of coping resources?

1.1 Marriage and Psychological Well-Being

Marriage has long been recognized as a fundamental social institution (Burgess and Locke 1945; Goode 1963) that provides important protective barriers against the stressful consequences of external threats (Gove et al. 1983; Umberson 1992; Ross 1995). Efforts to encourage marriage have been supported by research linking it to adult psychological well-being (Musick and Bumpass 2012). In western countries, numerous studies have confirmed that married and cohabiting individuals were more likely to report greater life satisfaction and had lower risk of psychological disorders and depression than their unmarried, divorced, and widowed counterparts (Stack and Eshleman 1998; Di Tella et al. 2003; Soons et al. 2009; Musick and Bumpass 2012).

The marriage ties that serve as sources of social support can also be sources of conflict and distress (Horwitz et al. 1998). It is not marriage per se but good marriage that serves important psychological functions for the partners (Gove et al. 1983). The association between marital quality and psychological distress was broadly examined in different samples of Western societies. Happy marital relationship was found to contribute to better psychological health (Barnett et al. 1994; Kiecolt-Glaser and Newton 2001; Bloch et al. 2010; Braun et al. 2010). Also, the marital happiness trajectory was associated with subsequent changes in both life happiness and depressive symptoms (Kamp Dush et al. 2008; Waite et al. 2009). A few studies also found both marital status and quality were important for maintaining lower ambulatory blood pressure and mental health (Holt-Lunstad et al. 2008; Prigerson et al. 1999). Additionally, people in unhappy marriages were found to have smaller declines in emotional well-being after divorce than those whose marriages were viewed more positively (Johnson and Wu 2002; Williams 2003). However, those who were divorced or separated after unhappy marriages did not improve significantly in psychological well-being (Kalmijn and Monden 2006; Waite et al. 2009). In short, the beneficial effects of marital status and relationship quality have both been confirmed in Western societies, but the joint effects of marital status and quality on life satisfaction are still not clear.

Marriage in China should be a different social institution. China’s collective values differ from the individualism observed in Western developed countries. However, with the rise of modern economies and the associated individualism, sexual relations, cohabitation, and childbearing, which were once confined to marriage, now take place outside of it and have increased dramatically over the past 40 years (Heuveline and Timberlake 2004). Also the rates of self-matching and divorce have increased rapidly in recent decades. Marriage is still almost universal, divorce remains relatively uncommon in China, and being single has more negative social implications in comparison to Western societies. Although the culture of extramarital sex, late marriage and divorce is more open in urban areas, the culture gap for marriage ideology between rural and urban areas is narrowing rapidly due to migration of farmers. Hence, marriage is expected to be more important for Chinese life satisfaction in both rural and urban areas. In China, recent studies confirmed that the psychological well-being of unmarried rural males was significantly lower than that of married males (Li et al. 2009), and happy marital relationship correlated with better psychological well-being of rural women (Chen and Tian 2010). Few studies in China have tested the joint effects of marital status and quality on life satisfaction, which are expected to be strongly beneficial to Chinese adult men and women.

According to the theory of gender roles, gendered socialization processes encourage women to value highly and identify with the role of wife and mother, and to place a high value on the emotional component of personal relationships (Bernard 1972; Gilligan 1982); as a consequence marriage is expected to be more beneficial for men than for women (Gove et al. 1983; Umberson 1992). Gender difference in these effects has been explored in Western societies (Gove et al. 1983; Umberson 1992; Barnett et al. 1994; Ross 1995). However, more recent studies indicated that marriage seemed to affect the health of men and women similarly (Barnett et al. 1994; Ross 1995; Umberson et al. 2006; Hewitt et al. 2012), but men and women responded to marital transitions with different types of emotional problems (Simon 2002). Some studies even report that the advantages of being married compared being single, divorced or widowed are greater for women than for men (Williams et al. 1992; Marks and Lambert 1998). Such inconsistent findings could reflect demographic and cultural changes in the developed Western societies, which have significantly altered women’s status and roles both within and outside of the family that provided equal advantages to women and men (Williams 2003). In contrast to the increased workforce participation that leads to changes in women’s role and their reduced dependence on a happy marriage in Western countries, women’s increasing level of economic activity in East Asia does not appear to have been accompanied by increases in men’s domestic roles (Tsuya and Bumpass 2004). Especially as China has transitioned to a market-oriented society, women’s status in the urban workplace has deteriorated. Housekeeping remains the primary role of Chinese women (Zuo and Bian 2001), and having a harmonious marital and family life instead of a successful career is still the highest achievement to which women can aspire. Additionally, marriage and children are the keys for men to gain social acceptance, since single men are thought to be a source of trouble to societies in Asian counties. Hence, gender difference in marriage and life satisfaction should be distinguished in China, where women may be more sensitive to negative aspects of relationships than men due to gender-linked roles, motives, and goals (Taylor et al. 2000).

1.2 The Role of Social Support and SES

According to the transactional theory of stress, any life or social event can be potentially stressful; whether or not it actually affects psychological health is a function of the subject’s cognitive appraisal of the event, and the availability of coping resources. If the event is not judged to be threatening or the necessary resources exist to offset the threat, stress will not occur (Lazarus and Folkman 1984). Hence, whether marital loss or conflict as an adverse life event affects psychological health is up to the availability of individual and social coping resources. Individual SES and social networks have been identified as an important protection—or at least a buffer—against stress, helping individuals maintain a generally positive emotional state (Wang 2004). Hence, the negative consequence of forced singlehood and unhappy marriage on life satisfaction could vary depending on the moderating effect of social support and individual SES. In addition, researchers highlight that people who are not married tend to have lower levels of social support and contact (Hurlbert and Acock 1990; Hewitt et al. 2012). In China, forced bachelors also tend to be isolated from society and to stay at the bottom of the social hierarchy, which may contribute to their lower levels of life satisfaction. This suggests that social support and individual SES may have mediating effect on life satisfaction and marriage. Unlike forced bachelors, who usually have lower education and income (Tucker et al. 2005) as well as smaller social networks (Li et al. 2009), surplus women have more social capital than married women in China, which may suggest that the mediating/moderating effect of social support and individual SES may be gender specific.

Social support has long been known to affect the individual’s emotional health and general well-being in a directly beneficial way, or it may have more health-enhancing effects during times of high stress (i.e., buffering/interactive effects) (Dean et al. 1990; Wills 1985; Reinhardt 1996). There is now an extensive literature on the relationship between social support and mental health, mostly confirming the former’s beneficial and/or moderating effects (Berkman et al. 2000; Seeman 2000; Hogan et al. 2002; Escribà-Agüir et al. 2010). Some recent work also addresses the role of social support on the links between marriage and psychological well-being. In western societies, the mediating and moderating effect of friend/relative support and general social support on marital quality or status and psychological distress has been confirmed (Cotten et al. 2003; Hewitt et al. 2012). A study of Chinese elderly adults in cities also revealed that the effect of marital status on depressive symptoms was mediated by family support and moderated by friend support (Zhang and Li 2011). However, the specific supportive role of family, which is more likely than other kinds of social relations to protect psychological health (Thompson and Heller 1990), has not been tested. In China, kin provide more social support than other relationships due to the social interaction pattern of “diversity-orderly structure” which describes the Chinese human relationship based on distance to an individual. Intergenerational support has been identified as the most primary and stable social resource. Its beneficial effect on life satisfaction and mental health of Chinese elderly has been tested in many studies (Krause et al. 1998; Cong and Silverstein 2008; Wang and Li 2011). However, little research has concerned the beneficial or buffer effect of intergenerational support on life satisfaction of unmarried adults.

The protective role of SES on mental health has been the topic of many studies (Evans and Karowitz 2002; Rosenbaum 2008; Mirowsky and Ross 1998; Taylor and Seeman 1999). Previous research, both in developing and developed countries, has indicated that psychological health problems tend to be more prevalent among those of lower socioeconomic status (Johnson et al. 1999; Ashing-Giwa and Lim 2009; Gilman 2002; Mossakowski 2008; Ardington and Case 2010; Hamad et al. 2008). The mediating or moderating effects of SES on the impact of family structure (Barrett and Turner 2005), adverse events in childhood (Schieman et al. 2006; Mock and Arai 2010), and body mass index (Hu et al. 2012) on adult mental health were also observed in some studies. However, no study has addressed the role of SES on the association between marriage and psychological well-being and its dependence on gender. Emerging research indicates that it is not necessarily poverty itself but adverse changes in socioeconomic status that predict psychological stress (Das et al. 2009). Individuals may assess their economic condition based on changes they have experienced rather than their current income (Yu 2008). However, most previous work concerned the objective and status profile of SES rather than subjective cognition and changes of individual coping resources.

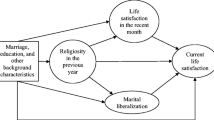

In this study, we use the data from a national sample of Chinese adults to assess the impact of marital status and quality on life satisfaction simultaneously, and further explore the moderating and mediating effect of intergenerational support and individual SES on both marital status and quality. We focus on whether the association between marriage and life satisfaction and the dynamic of intergenerational support and SES for life satisfaction differs between men and women.

2 Data, Variables and Method

2.1 Data

Data for this study come from the 2006 Chinese General Social Survey (CGSS), which is an annual or biannual survey of urban and rural households designed to gather data on social trends and the changing relationship between social structure and quality of life in China. This survey was conducted by Renmin University of China and Hong Kong University of Science and Technology. Using the sampling frame from the fifth census of China and a staged probability proportionate to size (PPS) design, a questionnaire interview was administered covering cities and towns in 28 provinces, municipalities, and autonomous regions. The population originally interviewed was limited to between 18 and 69 years of age. In the present study, to distinguish the singles who are forced bachelors and those who are below the age of marriage, 215 cases were excluded due to missing values or males and females aged less than 25. Only 2,469 valid samples are used for analysis, of which 53.3 % of the respondents are female. Table 1 shows the details.

2.2 Variables and Measurement

2.2.1 Life Satisfaction

Life satisfaction refers to an individual’s personal evaluation of his/her life. In our study, life satisfaction is measured on a five-point scale response to a question of “how do you feel about your life?” Because responses to this question are highly skewed in the two categories of “satisfied” and “unsatisfied”, and only a few responses fall into the other categories, life satisfaction is recoded as dichotomous variable in this study. The responses of “very unsatisfied”, “unsatisfied” and “average” were recorded as poor life satisfaction, and the responses of “satisfied” and “very satisfied” were recorded as good life satisfaction.

2.2.2 Marriage, Intergenerational Support and Perceived SES

Marriage is described by two indexes: marital status and marital quality. Considering the real and potential availability of partners under the gender imbalance in Chinese society, marital status in this study is recorded as singles and couples. Singles includes unmarried, divorced, and widowed, and couples include cohabiting and married. Marital quality is assessed in three dimensions: marital satisfaction, partner change expectation, and marital communication. Marital satisfaction is measured on a five-point scale response to the question, “In general, how satisfied are you with your marital life?” Partner change expectation is measured on a four-point scale response to the question, “If you had the opportunity to choose your partner again, would you choose the same person?” Marital communication is measured on a seven-point scale response to whether “my partner listens to me about my troubles” and “my partner tells me about his/her troubles”. To compare the differences in life satisfaction based on marital quality, the values of three dimensions for marital quality are summed, and recorded as dichotomous based on the median: 0 = low marital quality (value between 4 and 14); 1 = high marital quality (value between 15 and 23).

Intergenerational support is subdivided into financial support, instrumental support and emotional support, and is measured on a seven-point scale. Financial support is based on the frequency of receiving money from parents and adult children separately during the past 12 months. We measure instrumental support with the question, “How often do your parents provide help with housework (such as housecleaning and preparing dinner) and personal care (such as taking care of a baby or the aged)?” and “How often do your adult children provide help with housework (such as housecleaning and preparing dinner) and personal care (such as take care of a baby or the aged)?” Emotional support is measured with the items “How often do your parents listen to you when you want to talk about your worries or ideas?” and “How often do your adult children listen to you when you want to talk about your worries or ideas?”. Forced bachelors may not have their own children, but adoption is a possible choice for them. The supports from parents and children are both included and summed for analysis.

According to the transactional theory of stress, it is the subjective cognition of SES rather than objective SES that predicts psychological well-being. Perceived SES is defined as the perception of individual SES, and is measured with three indexes: SES, changed SES and SES change expectation. SES is assessed with a five-point scale in response to a question of “in your opinion, which socioeconomic status do you belong to”. Changed SES and SES change expectation are measured based on change direction compared with that 3 years ago and 3 years in the future, respectively, in terms of income, property, position, work condition, and socioeconomic status. Response of “decline” is recorded as “1”, responses of “no difference” and “hard to choose” are recorded as “2”, and response of “increase” is recorded as “3”. Values of the five items are summed.

2.2.3 Socio-Demographic Factors

The socio-demographic variables of education, income, age and Hukou are controlled in the analysis. Education is measured as the highest level of education achieved. Considering that there are few cases for some of the options, twenty-three categories are merged into five, namely informal education, primary school, junior high school, senior high school or technical secondary school, and junior college and above. Income is measured by the total amount of earnings last year, including bonuses, subsidies and dividends, and converted with ln + 1. Age is assessed as a continuous variable. Hukou is coded as dichotomous variable: 0 = “rural”, 1 = “urban”.

2.3 Analytic Strategy

We first compare the difference in life satisfaction between singles and couples, and between subgroups of couples based on marital quality in men and women separately, by Chi-squared test. Logistic regression is used to analyze the relationship between marital status and life satisfaction, as well the moderating role of intergenerational support and perceived SES, since life satisfaction is recoded as a dichotomous variable. Limiting the analysis to couples, correlations in marital quality, intergenerational support, perceived SES, and life satisfaction are tested. Analyses are conducted in male and female samples separately, to identify whether there are gender differences.

Analysis proceeded in three stages: First, we estimated a baseline model of the association between marriage and life satisfaction, including control variables (Model 1). In the second stage, the main effects of intergenerational support and perceived SES and their mediating effects were examined with equations for each set of variables (Models 2 and 4), and then with both sets in Models 6. In the third stage, the main effect and moderating effect of intergenerational support and perceived SES were examined. Each set was tested separately in Model 3 and Model 5, then both sets in our final models (Model 7). All analyses are conducted using SPSS 16.0 software.

3 Results

3.1 Differences in Life Satisfaction Based on Marital Status

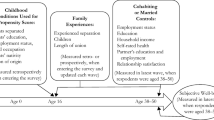

Figure 1 shows that both in male (F = 134.579; P < 0.000) and female samples (F = 101.014; P < 0.000), the difference in life satisfaction between singles and couples is significant. The percentage of people with good life satisfaction in couples is far greater than in singles.

To determine whether the difference in life satisfaction disparity was due to age differences between singles and couples, the two groups are further subdivided into five categories based on age: 1 = 25–29; 2 = 30–39; 3 = 40–49; 4 = 50–59; 5 = 60–69. As Fig. 2 shows, health disparity between the two groups varies greatly with age and depends on gender. For females, the gap in life satisfaction between the two groups is greatest at stage 2. However, the gap becomes narrower with increasing age. For males, only 30 % of single males have good life satisfaction before age 60, and the gap between the two groups of males narrows from stage 4.

3.2 Difference in Life Satisfaction Based on Marital Quality

As Fig. 3 shows, the percentage of people with good life satisfaction in the group with good marital quality is higher than that in the group with poor marital quality. The difference is significant in both males (F = 419.399; P < 0.000) and females (F = 76.141; P < 0.000), and the gap is higher in females. Comparing the life satisfaction between singles and the subgroup with poor marital quality, we find there is a significant difference between genders: the percentage of single women with good life satisfaction is higher than that of married women with poor marital quality, while the percentage of single men with good life satisfaction is even lower than that of men with poor marital quality.

3.3 Marital Status and Life Satisfaction

Tables 2 and 3 show the results of logistic regression for marital status and life satisfaction in males and females separately. There was a significant association between marital status and life satisfaction for women and men, and the effect size is bigger for men. The mediating effect of intergenerational support and individual SES for marital status and life satisfaction is not significant, and perceived SES explained more of the difference in life satisfaction than intergenerational support. However, the moderating effect is only significant for women.

As Table 2 shows, married or cohabiting women were more likely to have good life satisfaction than single women, controlling for individual socio-demographic factors (Model 1). The influence of marital status on life satisfaction had no significant decline after the variables intergenerational support (Model 2) and perceived SES (Model 4) were added separately, which means that marital status has a direct impact on life satisfaction, independent of intergenerational support and perceived SES. Women with more financial support were more likely to have good life satisfaction, and there was a negative association between emotional support and life satisfaction. In addition, SES and changed SES were positively correlated with life satisfaction for women. In Model 6, intergenerational support and perceived SES were tested together. The influence of financial support, SES and changed SES on life satisfaction remains significant.

In Model 3, the main effect of financial support on life satisfaction for women was significant and the coefficient for interaction with financial support was only marginally significant, while the coefficient for marital status was no longer statistically significant. Thus single women with more financial support are more likely to have bad life satisfaction. In Model 5, findings are similar for the role of SES change expectation; that is, single women with better SES change expectation are more likely to have bad life satisfaction. Additionally, the main effects of SES and changed SES remained significant. In our final model, the main effects of financial support, emotional support, SES and changed SES on life satisfaction remained statistically significant for women, the moderating effect of financial support on life satisfaction was no longer statistically significant, and the correlation between interaction of SES change expectation and life satisfaction for women became statistically significant.

The results of marital status for men are presented in Table 3. Married or cohabiting men were also more likely to have good life satisfaction than single men (Model 1). The coefficient for marital status remains significant and even increased after intergenerational support (Model 2) and perceived SES (Model 4) were added separately; that is, marital status had a direct impact on male life satisfaction independent of intergenerational support and perceived SES. There was a negative association at a marginally significant level between emotional support and life satisfaction for men (Model 2), and the influence was not significant in Model 6. SES and changed SES were positively correlated with male life satisfaction, and their coefficients increased in Model 6.

In Models 3 and 7, there were no statistically significant associations between intergenerational support and male life satisfaction, or between its interaction and life satisfaction. In Models 5 and 7, only the main effects of SES and changed SES on male life satisfaction were statistically significant. Intergenerational support and perceived SES explained no difference in male life satisfaction between singles and couples.

3.4 Marital Quality and Life Satisfaction

We limit the sample to couples, and divide them into three groups: cohabiting with marriage, cohabiting without marriage, and separated. The correlation of marital quality and life satisfaction is analyzed, controlling for marital status and individual objective SES. As Tables 4 and 5 show, the effect of marital quality on psychological well-being is greater for women than for men. There is a gender difference in the effects of intergenerational support and perceived SES on life satisfaction.

As Table 4 showed, women with high marital quality were more likely to have good life satisfaction than those with low marital quality (Model 1), and this was also true for Models 2 and 4; that is, the correlation between marital quality and life satisfaction was independent of intergenerational support and individual perceived SES. Financial support, SES, and changed SES were positively correlated with female life satisfaction. In Model 6, only the coefficient of financial support became marginally significant.

In Model 3, marital quality and financial support were positively correlated with life satisfaction, and there was a negative association between their interaction and life satisfaction, implying that financial support can partly compensate for the negative effect of low marital quality on female life satisfaction. In Model 5, the main effects of marital quality and SES were statistically significant, and their interaction was negatively correlated with female life satisfaction; that is, SES partly buffered the negative effect of lower marital quality. Findings were similar for our final model.

The results of marital quality for men are presented in Table 5. Men with high marital quality were also more likely to have good life satisfaction (Model 1). In Models 2 and 4, the coefficients of marital quality showed no significant decrease, so there were no significant mediating effects of intergenerational support and perceived SES. SES and changed SES were positively correlated with life satisfaction for men, and there was no significant association between intergenerational support and male life satisfaction. Findings were similar for Model 6.

In Models 3 and 5, marital quality no longer had a statistically significant effect on life satisfaction. Emotional support was negatively correlated with life satisfaction for men, and there was a positive association between the interaction of emotional support and life satisfaction. Emotional support explained most, although not all, of the difference in life satisfaction between those with high and low marital quality. There was a positive association between SES and life satisfaction for men, and the interaction of SES was negatively correlated with life satisfaction at a marginally significant level, suggesting that male SES buffered most of the negative effect of low marital quality for psychological well-being. Findings were similar for Model 7.

4 Conclusion and Discussion

The first objective of this study was to assess the difference in life satisfaction between groups based on marital status and quality, in order to understand more about the role of marriage in Chinese culture. Our comparative and regression analyses consistently showed that the life satisfaction of married or cohabiting men and women was better than that of single men and women, and men and women with high marital quality were more likely to have good life satisfaction than those with low marital quality. However, single women were more likely to have good life satisfaction than married women with low marital quality, and single men were more likely to have bad life satisfaction than married men with low marital quality. These findings reveal joint effects of marital status and quality and gender difference in the institution of marriage in Chinese culture. Marriage per se still serves as an important protection against the stressful consequences of external threats in developing China, especially for adult men. Our study also indicated that the disparity in life satisfaction between singles and couples was most serious at the ages 30–49, and this disparity narrowed rapidly after age 50. Undoubtedly, the forced bachelors especially the surplus men, will face more psychological depress under the gender imbalance that exists in China.

The second objective was to explore the mediating and moderating effect of intergenerational support and individual SES on marriage and mental health. Our results suggested that there was no significant mediating effect of intergenerational support and perceived SES, and their moderating effect was significant. However their moderating effect was gender-dependent. The association between marital status and life satisfaction was moderated by financial support and SES change expectation for women; the negative psychological effect of being a single female was strengthened instead of buffered by financial support and SES change expectation. The association of marital quality and life satisfaction was also moderated by financial support and perceived SES. Some of the negative psychological effect of low marital quality on females may be buffered by increased financial support and higher SES. In males, the moderating effects of intergenerational support and perceived SES on marital status and life satisfaction were not significant, and the association between marital quality and life satisfaction was moderated by emotional support and perceived SES, where more emotional support was more likely to improve life satisfaction for men with high marital quality, but most of the negative effect of low marital quality was buffered by high SES. These gender differences further confirm that marriage has different functions for men and women in China. In addition to women being more emotionally invested in marriage than men (Gove et al. 1983), marriage is also a very important way for women to acquire economic resources in China. To avoid the loss of their economic resources, married women may choose keep their marriage, even with low marital quality, while single women acquiring economic resources by themselves have to face more difficulty in the marriage market. In contrast, marriage is dependent on men’s SES rather than a way to acquire economic resources. Marriage may be more likely to represent a social contract and identity for men, which can offer them a sense of permanence, belonging and purpose (Waite and Gallagher 2000), and provide them an opportunity to gain social acceptance. These findings indicate that intergenerational support and perceived SES can only buffer the negative effect of low life satisfaction on married people, and traditional gender role norms are the greatest obstacle to improve life satisfaction of surplus men and women.

The impact of intergenerational support and perceived SES on life satisfaction, and how these differ between genders, was also explored. Women with more financial support, higher SES and the upward mobility of SES were more likely to have good life satisfaction in general, and higher SES and upward mobility of SES were also associated with good life satisfaction for men. This implies that financial support is more important for women than for men in maintaining good life satisfaction. However, perception of individual SES was a more powerful predictor of life satisfaction for men and women.

Among the limitations of this study is the use of cross-sectional data. The lack of longitudinal data makes it difficult to determine the causal relationship between marriage, social support, individual capital, and life satisfaction. A surprising finding is that emotional support correlates negatively with life satisfaction. A possible explanation is that people with more psychological difficulties are more likely to communicate with their parents or children. Further longitudinal data are necessary to explore this relationship. In addition, whether marriage has a selective effect for life satisfaction, so that people with worse life satisfaction are more likely to have marital difficulties or be single, is hard to test with cross-sectional data. However, as Pearlin and Johnson (1977) noted, the selection interpretation is generally made by investigators studying subjects with severe impairments. Also, Gove et al. (1981) strongly suggested that social selection is not a key determinant of the relationship between marital status and psychological well-being in a normal population. In addition, sex life is a part of marriage that maybe causally related to life satisfaction, especially for males, and this could be an important direction for future research.

References

Ardington, C., & Case, A. (2010). Interactions between mental health and socioeconomic status in the South African national income dynamics study. Studies in Economics and Econometrics, 34(3), 69–85.

Ashing-Giwa, K. T., & Lim, J. W. (2009). Examining the impact of socioeconomic status and socioecologic stress on physical and mental health quality of life among breast cancer survivors. Oncology Nursing Forum, 36(1), 79–88.

Barnett, R. C., Brennan, R. T., Raudenbush, S. W., & Marshall, N. L. (1994). Gender and the relationship between marital-role quality and psychological distress: A study of women and men in dual-earner couples. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 18, 105–127.

Barrett, A. E., & Turner, R. J. (2005). Family structure and mental health: The mediating effects of socioeconomic status, family process, and social stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 46(2), 156–169.

Berkman, L. F., Glass, T., Brissette, I., & Seeman, T. E. (2000). From social integration to health: Durkheim in the new millennium. Social Science and Medicine, 51, 843–857.

Bernard, J. (1972). The future of marriage. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Bloch, J. R., Webb, D. A., Matthew, L., Dennis, E. F., Bennett, I. M., & Culhane, J. F. (2010). Beyond marital status: The quality of the mother–father relationship and its influence on reproductive health behaviors and outcomes among unmarried low income pregnant women. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 14(5), 726–734.

Braun, M., Mura, K., Peter-Wight, M., Hornung, R., & Scholz, U. (2010). Toward a better understanding of psychological well-being in dementia caregivers: The link between marital communication and depression. Family Process, 49(2), 85–203.

Burgess, E. W., & Locke, H. J. (1945). The family: From institution to companionship. New York: American.

Chen, H., & Tian, X. (2010). Research on the relationship between marital quality and psychological well-being of new countryside women. Modern Preventive Medicine, 37(22), 4269–4270/4272. In Chinese.

Cong, Z., & Silverstein, M. (2008). Intergenerational time-for-money exchanges in rural China: Does reciprocity reduce depressive symptoms o f older grandparents? Research in Human Development, 5, 6–25.

Cotten, S. R., Burton Russell, P. D., & Rushing, B. (2003). The mediating effects of attachment to social structure and psychosocial resources on the relationship between marital quality and psychological distress. Journal of Family Issues, 24(4), 547–577.

Das, J., Do, Q., Friedman, J., & McKenzie, D. (2009). Mental health patterns and consequence: Results from survey data in five developing countries. The World Bank Economic Review, 23(1), 31–55.

Dean, A., Kolody, B., & Wood, P. (1990). Effects of social support from various sources on depression in elderly persons. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 31(2), 148–161.

Di Tella, R., MacCulloch, R., & Oswald, A. J. (2003). The macroeconomics of happiness. Review of Economics and Statistics, 85, 809–827.

Escribà-Agüir, V., Ruiz-Pérez, I., Montero-Piñar, M. I., Vives-Cases, C., Plazaola-Castaño, J., & Martín-Baena, D. (2010). Partner violence and psychological well-being: Buffer or indirect effect of social support. Psychosomatic Medicine, 72(4), 383–389.

Evans, G. W., & Karowitz, E. (2002). Socioeconomic status and health: The potential role of environmental risk exposure. Annual Review of Public Health, 23, 303–331.

Gilligan, C. (1982). In a different voice: Psychological theory and women’s development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Gilman, S. E. (2002). Commentary: Childhood socioeconomic status, life course pathways and adult mental health. International Journal of Epidemiology, 31(2), 403–404.

Goode, W. J. (1963). World revolution and family patterns. New York: The Free Press.

Gove, W. R., Hughes, M., & Style, C. B. (1983). Does marriage have positive effects on the psychological well-being of an individual? Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24, 122–131.

Gove, W.R., Style, C.B., & Hughes, M. (1981). The function of marriage for the individual: A theoretical discussion and empirical evaluation. Presented at the annual meeting of the American Sociological Association, Toronto.

Hamad, R., Fernald, L. C., Karlan, D. S., & Zinman, J. (2008). Social and economic correlates of depressive symptoms and perceived stress in South African adults. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 62(6), 538–544.

Heuveline, P., & Timberlake, J. M. (2004). The role of cohabitation in family formation: The United States in comparative perspective. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66, 1214–1230.

Hewitt, B., Turrell, G., & Giskes, K. (2012). Marital loss, mental health and the role of perceived social support: Findings from six-waves of an Australian population based panel study. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 66(4), 308–314.

Hogan, B. E., Linden, W., & Najarian, B. (2002). Social support interventions. Do they work? Clinical Psychology Review, 22, 381–440.

Holt-Lunstad, J., Birmingham, W., & Jones, B. Q. (2008). Is there something unique about marriage? The relative impact of marital status, relationship quality, and network social support on ambulatory blood pressure and mental health. Annual Behavior Medicine, 35, 239–244.

Horwitz, A. V., McLaughlin, J., & White, H. R. (1998). How the negative and positive aspects of partner relationships affect the psychological well-being of young married people. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 39, 124–136.

Hu, H. Y., Wu, C. Y., Chou, Y. J., & Huang, N. (2012). Body mass index and mental health problems in general adults: Disparity in gender and socioeconomic status. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2012.01.007.

Hurlbert, J. S., & Acock, A. C. (1990). The effects of marital status on the form and composition of social networks. Social Science Quarterly, 71, 163–174.

Johnson, J. G., Cohen, P., Dohrenwend, B. P., Link, B. G., & Brook, J. S. (1999). A longitudinal investigation of social causation and social selection processes involved in the association between socioeconomic status and psychiatric disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 108, 490–499.

Johnson, D. R., & Wu, J. (2002). An empirical test of crisis, social selection, and role explanations of the relationship between marital disruption and psychological distress: A pooled time-series analysis of four-wave panel data. Journal of Marriage and Family, 64, 211–224.

Kalmijn, M., & Monden, W. S. (2006). Are the negative effects of divorce on well-being dependent on marital quality? Journal of marriage and Family, 68, 1197–1213.

Kamp Dush, C. M., Taylor, M. G., & Kroeger, R. A. (2008). Marital happiness and psychological well-being across the life course. Family Relations, 57, 211–226.

Kiecolt-Glaser, J. K., & Newton, T. (2001). Marriage and health: His and hers. Psychological Bulletin, 127, 472–503.

Klasen, S., & Wink, C. (2002). A turning point in gender bias in mortality? An update on the number of missing women. Population and Development Review, 28(2), 285–312.

Krause, N., Liang, J., & Gu, S. (1998). Financial strain, received support, anticipated support, and depressive symptoms in the People s’ Republic of China. Psychology and Aging, 13, 58–68.

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer.

Li, S., Jiang, Q., Attane, I., & Feldman, M. (2006). Son preference and the marriage squeeze in China: An integrated analysis of the first marriage and remarriage market. Population & Economics, 6, 1–8. In Chinese.

Li, Y., Li, S., & Peng, Y. (2009). A comparison of psychological well-being between forced bachelors and married male. Population and Development, 15(4), 2–12. In Chinese.

Marks, N. F., & Lambert, J. K. (1998). Marital status continuity and change among young and midlife adults: Longitudinal effects on psychological well-being. Journal of Family Issues, 19, 652–687.

Mirowsky, J., & Ross, C. E. (1998). Education, personal control, lifestyle and health: A human capital hypothesis. Research on Aging, 20, 415–449.

Mock, S. E., & Arai, S. M. (2010). Childhood trauma and chronic illness in adulthood: Mental health and socioeconomic status as explanatory factors and buffers. Frontiers in Psychology. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2010.00246.

Mossakowski, K. N. (2008). Dissecting the influence of race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status on mental health in young adulthood. Research on Aging, 30(6), 649–671.

Musick, K., & Bumpass, L. (2012). Reexamining the case for marriage: Union formation and changes in well-being. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74(1), 1–18.

Pearlin, L., & Johnson, J. (1977). Marital status, life strains and depression. American Sociological Review, 42, 704–715.

Prigerson, H. G., Maciejewski, P. K., & Rosenheck, R. A. (1999). The effects of marital dissolution and marital quality on health and health service use among women. Medical Care, 37(9), 858–873.

Reinhardt, J. P. (1996). The importance of friendship and family support in adaptation to chronic vision impairment. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences, 5, 268–278.

Rosenbaum, E. (2008). Racial/ethnic differences in asthma prevalence: The role of housing and neighborhood environment. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 49, 131–145.

Ross, C. E. (1995). Reconceptualizing marital status as a continuum of social attachment. Journal of Marriage and Family, 57, 129–140.

Schieman, S., Pudrovska, T., Pearlin, L. I., & Ellison, C. G. (2006). The sense of divine control and psychological distress: Variations across race and socioeconomic status. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 45(4), 529–549.

Seeman, T. E. (2000). Health promoting effects of friends and family on health outcomes in older adults. American Journal of Health Promotion, 14, 362–370.

Simon, R. W. (2002). Revisiting the relationships among gender, marital status and mental health. American Journal of Sociology, 107(4), 1065–1096.

Soons, J. P. M., Liefbroer, A. C., & Kalmijn, M. (2009). The long-term consequences of relationship formation for subjective well-being. Journal of Marriage and Family, 71(5), 1254–1270.

Stack, S., & Eshleman, J. R. (1998). Marital status and happiness: A 17 nation study. Journal of Marriage and Family, 60, 527–536.

Taylor, S. E., Klein, L. C., Lewis, B. P., Gruenewald, T. L., Gurung, R. A. R., & Updegraff, J. A. (2000). Biobehavioral responses to stress in females: Tend-and-befriend, not Fight-or-flight. Psychological Review, 107, 411–429.

Taylor, S. E., & Seeman, T. E. (1999). Psychosocial resources and the SES-health relationship. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 896, 210–225.

Thompson, M. G., & Heller, K. (1990). Facets of support related to well-being: Quantitative social isolation and perceived family support in a sample of elderly women. Psychological Aging, 5, 535–544.

Tsuya, N., & Bumpass, L. (2004). Marriage, work and family life in comparative perspective: Japan. South Korea & the United States: University of Hawaii Press.

Tucker, J. D., Henderson, G. E., Wang, T. F., et al. (2005). Surplus men, sex work, and the spread of HIV in China. AIDS, 19(6), 539–547.

Umberson, D. (1992). Gender, marital status and the social control of health behavior. Social Science and Medicine, 34, 907–917.

Umberson, D., Williams, K., Powers, D. A., Liu, H., & Needham, B. (2006). You make me sick: Marital quality and health over the life course. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 47(1), 1–16.

Waite, L., & Gallagher, M. (2000). A case for marriage. New York: Doubleday.

Waite, L. J., Luo, Y., & Lewin, A. C. (2009). Marital happiness and marital stability: Consequences for psychological well-being. Social Science Research, 38, 201–212.

Wang, Y. (2004). An introduction of the theory and researches of social support. Psychological Science, 27(5), 1175–1177. In Chinese.

Wang, P., & Li, S. (2011). A longitudinal study of the dynamic effect of intergenerational support on life satisfaction of rural elderly. Population Research, 35(1), 44–52. In Chinese.

Wei, T., & Zhang, G. (2010). Surplus women of cities in modern society. China Youth Study, 5, 22–24. In Chinese.

Williams, K. (2003). Has the future of marriage arrived? A contemporary examination of gender, marriage and psychological well-being. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 44, 470–487.

Williams, D. R., Takeuchi, D. T., & Adair, R. K. (1992). Marital status and psychiatric disorders among blacks and whites. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 33, 140–157.

Wills, T. A. (1985). Supportive functions of interpersonal relationships. In S. Cohen & S. L. Syme (Eds.), Social support and health (pp. 61–82). New York: Academic Press.

Yu, W. (2008). The psychological cost of market transition: Mental health disparities in reform-era China. Social Problems, 55(3), 347–369.

Zhang, B., & Li, J. (2011). Gender and marital status differences in depressive symptoms among elderly adults: The roles of family support and friend support. Aging Mental Health, 15(7), 844–854.

Zuo, J., & Bian, Y. (2001). Gender resource, division of housework, and perceived fairness: A case in urban China. Journal of Marriage and Family, 63, 1122–1133.

Acknowledgments

The data used in this study were from the Chinese General Social Survey (CGSS) carried out in 2006, sponsored by the China Social Science Foundation. The data was originally collected by Renmin University of China and Hong Kong University of Science and Technology. We appreciate the assistance in providing data by the institutes. The research findings are the product of the researcher. Neither the original collectors of the data nor the Archive bear any responsibility for the analyses or interpretations presented here. In addition, this work was supported by National Social Science Foundation of China (08&ZD048).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, H., Li, S. & Feldman, M.W. Gender in Marriage and Life Satisfaction Under Gender Imbalance in China: The Role of Intergenerational Support and SES. Soc Indic Res 114, 915–933 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-012-0180-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-012-0180-z