Abstract

The main purpose of this study was to evaluate psychometric properties of the Serbian version of the Multidimensional Students’ Life Satisfaction Scale (MSLSS). The research was carried out on a sample of 408 high school students (250 females, 158 males), with the mean age 16.6. The Serbian version of the MSLSS has demonstrated good psychometric properties. The internal consistency coefficients (Cronbach’s α) for the MSLSS domain and total scores were adequate. Support for the validity of the MSLSS was provided by the pattern of correlations with various positive and negative indicators of well-being. However, it has been suggested that shortening the scale from 40 items to 25 items could provide more accurate measure of adolescents’ life satisfaction for the future research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Subjective well-being (SWB) is one of the key indicators of positive functioning and a core component in contemporary models of mental health (Keyes 2006; Vaillant 2003). Researchers distinguish between two components of SWB: affective and cognitive, both including subjective evaluations of one’s life (Diener 2000). Affective component of SWB relates to the balance of pleasant and unpleasant emotions in one’s life, while cognitive component includes satisfaction with life, referring to the global evaluation of a person on how his/her life looks like (Diener et al. 1997). Most authors agree that life satisfaction is a multidimensional construct (Diener et al. 1999), encompassing satisfaction with different domains of life, e.g., satisfaction with family, job, health etc.

In accordance with the distinction on global and domain satisfaction, two types of measures are used for assessment of cognitive component of SWB: global and specific. In adults, most widely used instrument of global life satisfaction is Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS, Diener et al. 1985), while the domain satisfaction measures tend to be designed for specific research purposes (Pavot 2008).

Most research on life satisfaction has been conducted on samples of adults, while assessment of adolescents life satisfaction has received less attention in the literature. Research on life satisfaction among adolescents, and positive mental health generally, were largerly neglected in psychology, until the end of the twentieth century. Due to the domination of medical model (Maddux et al. 2004), mental health studies in adolescents were focused on maladaptive and dysfunctional behaviours, such as violence (e.g., Dryfoos 1990), substance abuse (e.g., Weinberg et al. 1998), suicide and self-harm (Kerfoot 1996), just to name a few.

In line with the research focus on behaviours which impair psychosocial functioning of adolescents, practitioners were occupied with preventive programs and interventions based on risk factors (Park 2004), and empirical studies relied almost exclusively on psychopathological scales. The main limitation of the scales used for assessment of psychopathology is that they say almost nothing about positive aspects of mental health, i.e. they enable us to assess how bad one feels and functions, but they do not allow us to draw conclusions on how good one feels (Bartlett and Coles 1998).

Pathocentric perspective in psychology is well illustrated in the fact that until 1990 s there were no psychometrically sound instruments for the assessment of life satisfaction among the youth (Suldo et al. 2006). Only recently, with the emergence of positive psychology (Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi 2000) it has been recognized that the complete assessment of mental health in adolescents should include positive indicators of well-being. Research consistently show that mental health is more than the absence of mental illness and that well-being measures need to be included as well (Greenspoon and Saklofske 2001; Westerhof and Keyes 2010).

Life satisfaction has been postulated as one of the key elements of positive mental health in children and adolescents. A number of studies have provided support for the importance of life satisfaction in adolescents (Gilman and Huebner 2006; Suldo and Huebner 2006). Low life satisfaction among adolescents has been related to greater suicide risk (Valois et al. 2004), violent behaviors (Valois et al. 2006), substance abuse (Zullig et al. 2001). On the other hand, adolescents reporting very high life satisfaction are shown to display better functioning on a broad range of school, intrapersonal and interpersonal measures, than adolescents with both average and low life satisfaction (for a detailed review see Proctor et al. 2009).

Until recently, assessment of life satisfaction in children and adolescents has been limited to unidimensional measures which provide only global score, such as the Perceived Life Satisfaction Scale (Adelman et al. 1989), the Students’ Life Satisfaction Scale (Huebner 1991) and the Satisfaction with Life Scale adapted for Children (Gadermann et al. 2010). Domain-specific measures provide more sensitive and differentiated assessment of life satisfaction, enable examination of relative importance of each domain for global satisfaction, and make possible research on the correlates, predictors and outcomes of domain-specific life satisfaction.

One of the most frequently used instruments developed to assess the life satisfaction in adolescents is the Multidimensional Students’ Life Satisfaction Scale (MSLSS; Huebner 1994). The MSLSS is an instrument aimed at measuring both overall life satisfaction and satisfaction across five specific domains: family, friends, school, living environment and self.

Although most studies using the MSLSS have been conducted on US and English speaking adolescents (Greenspoon and Saklofske 1998; Huebner 1994; Huebner et al. 1998), recently the MSLSS has been validated in a several non-western countries: Korea (Park et al. 2004), Turkey (Irmak and Kuruuzum 2009) and Iran (Hatami et al. 2010). Need for cross-cultural validation of instruments aimed at assessing life satisfaction stems from the fact that specific cultural and societal factors have an important role in determining one’s life satisfaction (Schimmack et al. 2002; Suh and Koo 2008). The sine qua non for comparable measures in studying life satisfaction in different countries is to test equivalence in factor structure and validity of that measure across samples from various cultural contexts.

The results of the above-mentioned studies have supported the five-factor structure of the MSLSS and proved this instrument to be a reliable and valid measure of adolescents’ life satisfaction in different cultures and societies. However, the CFA model fit indices were found to vary considerably across the samples in previous research. Some studies provided good fit indices for the 5-factor model (e.g., Gilman et al. 2000; Irmak and Kuruuzum 2009; Park et al. 2004), whereas others yielded fit indices that did not fall within the acceptable boundaries (e.g., Greenspoon and Saklofske 1998; Hatami et al. 2010; Sawatzky et al. 2009).

The majority of these studies have examined psychometric properties of the MSLSS in countries with high level of development (e.g., Canada, USA, Spain). On the other hand, research on the validity of the MSLSS among adolescents from developing and transition countries are largely lacking.

1.1 The Present Study

The main aim of this study was to evaluate psychometric properties of the Serbian version of the MSLSS. We have analyzed internal consistency, factor structure, convergent and discriminant validity of the MSLSS in a sample of Serbian high school students.

2 Methods

2.1 Participants and Procedure

The sample consisted of 408 high school students (250 females, 158 males), from five secondary schools in Serbia. The mean age of the participants was 16.6 (SD = 0.88) with a range of 15–19. The measures were administered to participants who agreed to complete the study on voluntary basis, in the classroom, during the last week of the first term. It took them on average 30 min to complete the questionnaires.

2.2 Instruments

The Multidimensional Students’ Life Satisfaction Scale (MSLSS; Huebner 1994) is a 40-item self-report instrument designed to measure satisfaction across five life domains: Family (e.g., “I like spending time with my parents”), Friends (e.g., “My friends are nice to me”), School (e.g., “I like being in school”), Living environment (e.g., “There are lots of fun things to do where I live”), and Self (e.g., “I am a nice person”). Participants provided their responses using a 6-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree).

The MSLSS was translated into Serbian by the first author, and back-translated into English by a bilingual English teacher. The back-translated version was then sent to the original author, who confirmed its accuracy.

The Serbian Inventory of Affect based on the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule-X (SIAB-PANAS; Novovic and Mihic 2008) is a Serbian translation and adaptation of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule-X (PANAS-X; Watson and Clark 1994). The scale demonstrated excellent psychometric properties in previous research (Novovic et al. 2008). In the current research, we used the short form to measure Positive affect (α = 0.78) and Negative affect (α = 0.81), with ten items each. Participants were asked to rate how they feel in general, using 5-point scale from 1 (never or almost never) to 5 (always or almost always).

Global life satisfaction was assessed with a single question: All things considered, how satisfied are you with your life? The responses ranged from 1 (not at all satisfied) to 5 (absolutely satisfied).

Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES; Rosenberg 1965) was used to assess global self-esteem (α = 0.86). RSES consists of 10 items (e.g., “I feel that I have a number of good qualities”), rated on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Expectations about the future and general sense of optimism was measured with the Serbian version of the Life Orientation Test-Revised (LOT-R; Scheier et al. 1994). The LOT-R consists of 10 items (4 filler items), rated across a five point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to five (strongly agree). Three items are positively worded (e.g., “In uncertain times, I usually expect the best”) and three are negatively worded (e.g., “I hardly ever expect things to go my way”). Cronbach’s alpha in the current sample was 0.73.

Sense of loneliness was measured with the Serbian translation of the De Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale (DJGLS; De Jong Gierveld and Kamphuis 1985). The DJGLS consists of 11 items, measuring two aspects of loneliness: social (e.g., “I can call on my friends whenever I need them”) and emotional (e.g., “I miss having people around me”). Items are rated across a three point scale (“yes”, “more or less” and “no”). The scale showed good reliability and validity in previous research (De Jong Gierveld and Van Tilburg 1999). Cronbach’s alpha in the current sample was 0.77.

The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS; Zimet et al. 1988) consists of 12 items, aimed at measuring perceived social support. The MSPSS encompasses three subscales: family support (e.g., “My family really tries to help me”), friends support (e.g., “I can talk about my problems with my friend”) and significant other support (e.g., “I have a special person who is real source of comfort to me”). The responses to each of the twelve items range from 1 (strongly disagree), to 5 (strongly agree). In a current study, we used only the total score (α = 0.88).

The Serbian version of the Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-21; Lovibond and Lovibond 1995) was used to assess negative affective states. The DASS-21 consists of 21 items and includes three subscales: depression (e.g., “I found it difficult to work up the initiative to do things”), anxiety (e.g., “I felt I was close to panic”) and stress (e.g., “I found myself getting agitated”). Responses are rated on a 4-point scale, from 0 (did not apply to me at all) to 3 (applied to me very much, or most of the time). The DASS-21 has been widely used and showed good psychometric properties both in adult and adolescent samples (e.g., Henry and Crawford 2005; Szabo 2010). In the present study, Cronbach’s alphas for the depression, anxiety and stress subscales were 0.87, 0.82, 0.86, respectively.

3 Results

3.1 Reliability and Exploratory Analysis

Results showed that both the subscales of the MSLSS and the total score had adequate reliability (Table 1). The internal consistency coefficients (Cronbach’s α) for the Family, Friends, School, Life environment and Self satisfaction subscales of the MSLSS were 0.88, 0.88, 0.84, 0.78 and 0.78, respectively. The reliability of the MSLSS total score was α = 0.90.

By comparing means and standard deviations of the MSLSS domains, we found the highest satisfaction in Friendship dimension, followed by Self and Family dimensions, and comparatively the lowest in School dimension (Table 1).

Item-total correlations were computed for each item on each of the subscales, and further indicated good reliability for all five subscales. Item-total correlations were substantial for most of the items (in the range of 0.27–0.75). Interestingly, the reversed items with negative connotation showed the lowest of these correlations.

3.2 Principle Component Analyses

The results of principle component analysis (PCA) of the entire item pool did not exactly follow the expected latent structure of the scale. Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure of sampling adequacy (KMO = 0.87) and significant Bartlett’s test of sphericity (Chi square = 6802.19, p < 0.001) indicated that correlation matrix was adequate for performing the PCA. By using a promax rotation with Kaiser normalization and Guttmann-Kaiser criterion for predicting the number of components (Yeomans and Golder 1982), we found the 9-component solution explaining 61.53% of total variance. The structure of components suggested that we succeeded in fully replicating only the Family and Friendship dimensions, while other dimensions did not seem to follow the original model (Table 2).

At this point of the analyses, we decided to repeat the PCA, excluding these items that confound the originally expected latent structure of the scale. For this purpose, we combined two exclusion criteria. The first was lower item-total correlation with the original subscale (Table 1), and the second was higher loading on the principal component other than theoretically expected (Table 2). Also, these circumstances reached out an opportunity to reduce all of the subscales to 5 items, which could provide a possibility of comparing the subscale sums without previous standardization.

After reducing the scale to 25-item solution, we repeated the PCA by subjecting the correlation matrix to a promax rotation with Kaiser normalization. Again, the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure of sampling adequacy (KMO = 0.85) and significant Bartlett’s test of sphericity (Chi square = 4,155.06, p < 0.001) indicated that the correlation matrix was adequate for performing the analysis. Based on the Guttmann-Kaiser criterion as well as the examination of the scree test, this time the 5-factor solution appeared to fit the data best by explaining 59.97% of total variance. As shown in Table 3, the originally expected factor structure was replicated perfectly. Notably, the School component had the lowest correlations with the other components (Table 4).

After this reduction, an additional analysis was performed in order to reassess the subscales reliability. As can be seen from the results (Table 1), reliability coefficients of the subscales slightly deteriorated, but not significantly.

3.3 Confirmatory Factor Analyses

In order to evaluate fit indices of our newly proposed model, as well as to compare these indices with the original 40-item scale model, we performed two confirmatory factor analyses. For this purpose, the SEPATH module of STATISTICA 7.1 was used and the model parameters were computed by using maximum likelihood discrepancy function. Comparison of several absolute fit indices, χ², comparative fit index (CFI), goodness of fit index (GFI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) and root mean square standardized residual (RMSSR) were used, as well as adjusted goodness of fit index (AGFI) and χ²/df ratio, due to the sample size. As a measure of incremental fit, we used normed fit index (NFI).

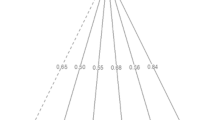

As we can see in Table 5, results in all measures suggest an improvement of fit with the item reduction. Although some of them (χ²/df) are rather acceptable for the both of the models, indices suggest that 25-item solution is much closer in meeting the conventional criteria for acceptability (Chau 1997; Hu and Bentler 1999). Figure 1 shows the factor loadings, estimated error variances and correlations between dimensions of the 25-item version of the MSLSS.

3.4 Convergent and Discriminant Validity

Convergent validity of the MSLSS was examined by computing correlations between the MSLSS (subscales and total score) and various positive and negative indicators of mental health (Table 6). Measures of subjective well-being (global life satisfaction, positive and negative affect), intrapersonal (self-esteem and optimism), interpersonal (loneliness and social support) and distress variables (depression, anxiety and stress) were included.

Both the MSLSS subscales and the total score were found to be significantly associated with all the well-being indicators. The Family satisfaction subscale had the highest correlation with perceived social support (r = 0.52). Friends satisfaction had the strongest association with the measures of interpersonal functioning, i.e. moderate positive correlation with perceived social support (r = 0.65) and moderate negative correlation with loneliness (r = −0.62). School satisfaction was most strongly associated with positive affect and global life satisfaction (r = 0.41 for both), while Living environment had the highest correlation with global life satisfaction (r = 0.40). As expected, a moderate positive correlation between Self satisfaction and self-esteem was found (r = 0.58). The total MSLSS score had the strongest associations with global life satisfaction and social support (r = 0.64 for both).

The lowest correlations were obtained between the MSLSS subscales and measures of emotional distress, supporting discriminant validity of the MSLSS.

The correlations between the MSLSS and demographic variables (age and gender) were low or non-significant. Younger students reported somewhat higher global life satisfaction (r = −0.13, p < 0.05) and higher satisfaction with family (r = −0.10, p < 0.05), friends (r = −0.12, p < 0.05) and living environment (r = −0.12, p < 0.05). There were no significant gender differences in the MSLSS scores, except for friends satisfaction, with girls reporting higher satisfaction than boys (t(1, 386) = −3.11, p < 0.01).

4 Discussion

The purpose of this study was to investigate the psychometric properties of the Serbian version of the MSLSS in a sample of high school students. The MSLSS displayed good reliability, five-factor structure was supported by means of CFA, and the MSLSS subscales showed adequate convergent and discriminant validity.

Mean scores on the MSLSS indicated that Serbian adolescents had positive reports of life satisfaction, which is in accordance with previous research in various countries showing that mean levels of life satisfaction among adolescents are above average (Gilman et al. 2008). Results showed that adolescents in this study had the highest satisfaction with friends and self, and that they were least satisfied with school. The mean levels of domain satisfactions are comparable to those reported in previous studies (e.g., Huebner et al. 2000), but school satisfaction in our sample is slightly lower (M = 3.48) than those obtained in most of the studies across different nations.

Correlations with demographic variables (age, gender) were low and mostly non-significant. Weak relationship between demographics and life satisfaction is consistent with previous research using the MSLSS (Huebner 2004). Single gender difference was observed in the MSLSS scores, with girls reporting higher satisfaction with friends, which is in accordance with the previous research (Gilman et al. 2000).

Reliability of the MSLSS was found to be adequate in both 40-item and 25-item variation. On the other hand, the principal component analysis failed to replicate the 5-component model of the original intention (Huebner et al. 1998) and subsequent findings (Greenspoon and Saklofske 1998), and provided a 9-component model. After inspecting item-total correlation data for each item, as well as component loadings, we found it useful to shorten the scale, leaving out the confounding items. After selecting 25 most representative items from the original pool, repeated analysis fully succeeded in replicating the originally intended model. The results of confirmatory factor analysis, showing the improvement of fit indices, provided additional arguments for reduction of the item pool to 25. On the other hand, the 5-factor solution for the 40 items model yielded poor fit indices (NFI = 0.71, CFI = 0.79, GFI = 0.77, AGFI = 0.74, RMSEA = 0.072), similar to those obtained in the studies conducted by Greenspoon and Saklofske (1998) and Sawatzky et al. (2009), with fit indices below the recommended levels.

However, it is noticeable that most of the confounding items were the negatively worded ones. Although recoded in the input matrix, the parameters of these items across the analyses seemed to differ from the usual trend. This might be due to the effect of item wording (Schweizer and Schreiner 2010) and the combination of negatively and positively worded items, which can result in lower internal consistency (Barnette 2000), or more likely due to the influence of negative affect, causing unnecessary involvement of other constructs in explaining the total variance. Sawatzky et al. (2009) also reported severe problems with adolescents’ response consistencies to negatively worded MSLSS items, which led them to exclusion of all negatively worded and some positively worded items and abridgement of the scale to the 18-item solution with acceptable fit indices. The similar problem was found in Turkish validation study, although the authors found negatively worded items unsuitable due to culture-specific features of the collectivistic Turkish society in comparison with individualistic societies (Irmak and Kuruuzum 2009).

On the other hand, we must not neglect the fact that seven excluded items are originally located in the last 11 items of the scale, so it could be argued that the reasons for inconsistence of data could be simply the weakening of attention or amusement during the scale administration. Having in mind that the systematic influence of the scale position has been controlled by randomizing the order in which the instruments were administered, as well as the fact that the item-total correlations for other instruments did not vary in the same manner as for the MSLSS, we should focus on the fact that the 40-item MSLSS scale has been the longest in our research material. Although we have not foreseen this possibility while designing our research, this finding opened up a practical issue of the length of the instrument in research with children and adolescents. Even though shortening the scale could be a potential solution to this problem, before recommending such a drastic measure, we find that it could be useful for future research to divide the MSLSS scale into two equal parts and insert the instrument used to measures the different construct between them, in order to prevent this kind of influence.

The validity of the MSLSS domain and total scores was determined by examining associations with various positive and negative indicators of well-being. Correlations between the MSLSS and other mental health measures were low to moderate, suggesting that they measure related, but distinct aspects of well-being. Each of the MSLSS specific domains subscales had the highest correlations with measures of similar constructs (e.g., Self satisfaction with self-esteem, both Family and Friends satisfaction with perceived social support), providing additional evidence for convergent validity. Discriminant validity of the MSLSS subscales was supported by the low correlations obtained between domain specific satisfaction scores and distress variables (depression, anxiety, and stress). The pattern of correlations with the DASS-21 subscales is comparable to the findings of previous studies examining relations between distress symptoms and life satisfaction in high school students (e.g., Fouladchang et al. 2010).

There are several limitations to the current study that need to be mentioned. The main weakness of this research refers to generalizability of the findings. The sample consisted of students from only one province (AP Vojvodina) which is considered to be the most developed region of the Republic of Serbia, but covers only about one quarter of the total population of Serbia. Additionally, only three types of high schools were included in the research: school of economics, grammar and medical school. Future research should examine life satisfaction among adolescents in less developed regions, encompass other types of schools (e.g., technical) and include measures of socioeconomic status.

In summary, the Serbian version of the MSLSS has demonstrated good psychometric properties, providing further evidence of the cross-cultural utility of the MSLSS for the purpose of assessing life satisfaction among children and adolescents. However, it has been suggested that shortening the scale from 40 items to 25 items could provide a more accurate measure of adolescents’ life satisfaction for the future research.

References

Adelman, H. S., Taylor, L., & Nelson, P. (1989). Minors’ dissatisfaction with their life circumstances. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 20, 135–147.

Barnette, J. J. (2000). Effects of stem and Likert response option reversals on survey internal consistency: If you feel the need, there is a better alternative to using those negatively worded stems. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 60, 361–370.

Bartlett, C. J., & Coles, E. C. (1998). Psychological health and wellbeing: Why and how should public health specialists measure it ? Part 1: Rationale and methods of the investigation, and review of psychiatric epidemiology. Journal of Public Health Medicine, 20, 281–287.

Chau, P. Y. K. (1997). Reexamining a model for evaluating information center success using a structural equation modeling approach. Decision Sciences, 28, 309–334.

De Jong Gierveld, J., & Kamphuis, F. H. (1985). The development of a Rasch-type loneliness scale. Applied Psychological Measurement, 9(3), 289–299.

De Jong Gierveld, J., & Van Tilburg, T. G. (1999). Manual of the Loneliness Scale. Amsterdam: Vrije Universiteit, Department of Social Research Methodology.

Diener, E. (2000). Subjective well-being: The science of happiness, and a proposal for a national index. American Psychologist, 55, 34–43.

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The Satisfaction with Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 71–75.

Diener, E., Suh, E. M., Lucas, R. E., & Smith, H. E. (1999). Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125, 276–302.

Diener, E., Suh, E., & Oishi, S. (1997). Recent findings on subjective well-being. Indian Journal of Clinical Psychology, 24, 25–41.

Dryfoos, J. G. (1990). Adolescents at risk: Prevalence and prevention. New York: Oxford University Press.

Fouladchang, M., Kohgard, A., & Salah, V. (2010). A study of psychological health among students of gifted and nongifted high schools. Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences, 5, 1220–1225.

Gadermann, A. M., Schonert-Reichl, K. A., & Zumbo, B. D. (2010). Investigating validity evidence of the Satisfaction with Life Scale adapted for Children. Social Indicators Research, 96, 229–247.

Gilman, R. S., & Huebner, E. S. (2006). Characteristics of adolescents who report very high life satisfaction. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 35(3), 311–319.

Gilman, R., Huebner, E. S., & Laughlin, J. (2000). A first study of the Multidimensional Students’ Life Satisfaction Scale with adolescents. Social Indicators Research, 52, 135–160.

Gilman, R., Huebner, E. S., Tian, L., Park, N., Schiff, M., Sverko, D., et al. (2008). Cross-national adolescent multidimensional life satisfaction reports: Analyses of Mean Scores and response style differences. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 37, 142–154.

Greenspoon, P. J., & Saklofske, D. H. (1998). Confirmatory factor analysis of the Multidimensional Students’ Life Satisfaction Scale. Personality and Individual Differences, 25, 965–971.

Greenspoon, P. J., & Saklofske, D. H. (2001). Toward an integration of subjective wellbeing and psychopathology. Social Indicators Research, 54, 81–108.

Hatami, G., Motamed, N., & Ashrafzadeh, M. (2010). Confirmatory factor analysis of Persian adaptation of Multidimensional Students’ Life Satisfaction Scale (MSLSS). Social Indicators Research, 98, 265–271.

Henry, J. D., & Crawford, J. R. (2005). The short-form version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21): construct validity and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 44, 227–239.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indices in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modelling, 6, 1–55.

Huebner, E. S. (1991). Initial development of the Students’ Life Satisfaction Scale. School Psychology International, 12, 231–240.

Huebner, E. S. (1994). Preliminary development and validation of a multidimensional life satisfaction scale for children. Psychological Assessment, 6, 149–158.

Huebner, E. S. (2004). Research on assessment of life satisfaction of children and adolescents. Social Indicators Research, 66, 3–33.

Huebner, E. S., Drane, W., & Valois, R. F. (2000). Levels of demographic correlates of adolescent life satisfaction reports. School Psychology Quarterly, 21, 281–292.

Huebner, E. S., Laughlin, J. E., Ash, C., & Gilman, R. (1998). Development of a new measure of children’s psychological well-being: Further validation of the Multidimensional Students’ Life Satisfaction Scale. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 16, 118–134.

Irmak, S., & Kuruuzum, A. (2009). Turkish validity examination of the Multidimensional Students’ Life Satisfaction Scale. Social Indicators Research, 92, 13–23.

Kerfoot, M. (1996). Suicide and deliberate self-harm in children and adolescents: A research update. Children and Society, 10, 236–241.

Keyes, C. L. M. (2006). Subjective well-being in mental health and human development research worldwide: An introduction. Social Indicators Research, 77, 1–10.

Lovibond, S. H., & Lovibond, P. F. (1995). Manual for the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (2nd ed.). Sydney: Psychology Foundation.

Maddux, J. E., Snyder, C. R., & Lopez, S. J. (2004). Toward a positive clinical psychology: Deconstructing the illness ideology and constructing an ideology of human strengths and potential. In P. A. Linley & S. Joseph (Eds.), Positive psychology in practice (pp. 320–334). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Novovic, Z., & Mihic, Lj. (2008). Srpski inventar afekata baziran na positive and negative affect schedule-X (SIAB-PANAS). Novi Sad: University of Novi Sad. Unpublished manuscript.

Novovic, Z., Mihic, Lj., Tovilovic, S., & Jovanovic, V. (2008). Relations among positive and negative affect, dysphoria and anxiety. Psihologija, 41(4), 413–435.

Park, N. (2004). The role of subjective well-being in positive youth development. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 591(1), 25–39.

Park, N., Huebner, E. S., Laughlin, J. E., Valois, R. F., & Gilman, R. (2004). A cross-cultural comparison of the dimensions of child and adolescent life satisfaction reports. Social Indicators Research, 66, 61–79.

Pavot, W. (2008). The assessment of subjective well-being: Successes and shortfalls. In M. Eid & R. Larson (Eds.), The science of subjective well-being (pp. 124–140). New York: The Guilford Press.

Proctor, C. L., Linley, P. A., & Maltby, J. (2009). Youth life satisfaction: A review of the literature. Journal of Happiness Studies, 10(5), 583–630.

Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Sawatzky, R., Ratner, P. A., Johnson, J. L., Kopec, J. A., & Zumbo, B. D. (2009). Sample heterogeneity and the measurement structure of the Multidimensional Students’ Life Satisfaction Scale. Social Indicators Research, 94, 273–296.

Scheier, M. F., Carver, C. S., & Bridges, M. W. (1994). Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): A re-evaluation of the Life Orientation Test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67, 1063–1078.

Schimmack, U., Radhakrishnan, P., Oishi, S., Dzokoto, V., & Ahadi, S. (2002). Culture, personality, and subjective well-being: Integrating process models of life-satisfaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82, 582–593.

Schweizer, K., & Schreiner, M. (2010). Avoiding the effect of item wording by means of bipolar instead of unipolar items: an application to social optimism. European Journal of Personality, 24, 137–150.

Seligman, M. E. P., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive Psychology: An introduction. American Psychologist, 55(1), 5–14.

Suh, E. M., & Koo, J. (2008). Comparing subjective well-being across cultures and nations: The “what” and “why” questions. In M. Eid & R. J. Larsen (Eds.), The science of subjective well-being (pp. 414–427). New York: The Guilford Press.

Suldo, S. M., & Huebner, E. S. (2006). Is extremely high life satisfaction during adolescence advantageous? Social Indicators Research, 78, 179–203.

Suldo, S. M., Riley, K., & Shaffer, E. S. (2006). Academic correlates of children and adolescents’ life satisfaction. School Psychology International, 27(5), 567–582.

Szabo, M. (2010). The short version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21): Factor structure in a young adolescent sample. Journal of Adolescence, 33, 1–8.

Vaillant, G. E. (2003). Mental health. American Journal of Psychiatry, 160, 1373–1384.

Valois, R. F., Paxton, R. J., Zullig, K. J., & Huebner, E. S. (2006). Life satisfaction and violent behaviors among middle school students. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 15, 695–707.

Valois, R. F., Zullig, K. J., Huebner, E. S., & Drane, J. W. (2004). Life satisfaction and suicide among high school adolescents. Social Indicators Research, 66, 81–105.

Watson, D., & Clark, L. A. (1994). The PANAS-X: Manual for the positive and negative affect schedule-expanded form. Iowa City: University of Iowa.

Weinberg, N. Z., Rahdert, E., Colliver, J. D., & Glantz, M. D. (1998). Adolescent substance abuse: A review of the past 10 years. Journal of American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 37, 252–261.

Westerhof, G. J., & Keyes, C. L. M. (2010). Mental illness and mental health: The two continua model across the lifespan. Journal of Adult Development, 17, 110–119.

Yeomans, K. A., & Golder, P. A. (1982). The Guttman-Kaiser criterion as a predictor of the number of common factors. The Statistician, 31, 221–229.

Zimet, G. D., Dahlem, N. W., Zimet, S. G., & Farley, G. K. (1988). The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. Journal of Personality Assessment, 52, 30–41.

Zullig, K. J., Valois, R. F., Huebner, E. S., Oeltmann, J. E., & Drane, J. W. (2001). Relationship between selected substance abuse behaviors and adolescent self-perceptions of life satisfaction. Journal of Adolescent Health, 29(4), 279–288.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jovanovic, V., Zuljevic, D. Psychometric Evaluation of the Serbian Version of the Multidimensional Students’ Life Satisfaction Scale. Soc Indic Res 110, 55–69 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-011-9916-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-011-9916-4