Abstract

This article examines the link between regime types, social expenditure, and welfare attitudes. By employing data on 19 countries taken from the World Values Survey, the main aim is to see to what degree the institutions of a country affect the attitudes of its citizens. According to Esping-Andersen (The three worlds of welfare capitalism. Polity Press, Cambridge, 1990) welfare regimes can be classified into Liberal, Conservative, and Social Democratic categories. With this as my point of departure, I put forward two research questions: the first concerns the direct influence of regime type on people’s attitudes; the second seeks to trace the contours of the regime types by arguing that both social expenditure and welfare attitudes are products of a country’s institutional arrangements. These questions are answered through regression modelling and by examining the interplay between welfare attitudes, social expenditure, and welfare regimes. First, we see that there are significant differences in aggregated attitudes between countries belonging to the Liberal and the Conservative regimes, with the former’s citizens holding more rightist views than those of the latter. This is explained by the history and organization of welfare benefits of the two variations of Esping-Andersen’s classification. Second, by graphing welfare attitudes against social expenditure the outline of the three regime types mentioned above may be seen. Similar correspondence is not found with regards to an Eastern European category. All in all, this study renders some support for the regime argument.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The nations in the industrialized world have developed systems for providing their citizens with social security. Following Hobbes’ description of the state of nature, one has seen that the state needs to function as a guarantor for the sick, disabled, elderly, and unemployed. In some countries the welfare state has developed following a trajectory inspired by Locke, that is, that there is an established civil society where people can resolve their conflicts with the aid of the government. In these Liberal welfare regimes the state has a laissez-faire approach to social policy, including income transfer systems that are mostly oriented towards the impediment of poverty. The system has a trust in the self-regulatory mechanisms of the market. Here much of the security is based on privately organized insurance. Other countries have chosen a model where welfare is more tied to institutions in society. They offer more security through their social policies: however, this security is often associated with social-control mechanisms such as the workplace or the family. Further, some countries have a highly interventionist social policy, with strong emphasis on universalism and equality. These regime types promote an equality of services of the highest standard rather than the liberal equality of minimal needs. The term “welfare state” was coined to refer to the Scandinavian countries as early as the 1930s, but first entered into the general discourse following the end of World War II (Kaufmann 2000). It was used to describe the state’s sphere of responsibility concerning education, health, housing, poor relief, social insurance, and public health services (Eikemo and Bambra 2008; Ginsburg 1979). Or, as expressed by Esping-Andersen (1990, pp. 18–19): “state responsibility for securing some basic modicum of welfare for its citizens.” One of the early welfare theorists was Titmuss (1958) who described the British welfare state as a response to natural, psychological, and social dependencies. The industrial society had to care for its people during their childhood, old age, during child-bearing, or when sick and incapacitated. The golden age of welfare lasted from the establishment of these regimes until the economic crisis of the 1970s when the world experienced a period marked by recession and stagflation. This was followed by a welfare state retrenchment characterized by cuts in social expenditure, and reforms including the privatization and marketization of welfare services (Eikemo and Bambra 2008). The wish to reduce the size of public expenditure in many Western industrialized countries led to the renaissance of the market mechanism. However, support for the welfare state has remained strong in the public mind in the majority of OECD countries. People are generally in favor of some sort of safety net arrangements; they reject policies where some fall below the poverty line even though they wish to maximize their own income if one disregards this constraint (Aalberg 2003, p. 43).

In this article I look at two research questions. First, I investigate whether there is a direct influence of regime type on public opinion. My dependent variable is welfare attitudes. These opinions depend on the objective size of welfare spending. However, there is not perfect co-variation between subjective attitudes and objective indicators, as the former are also influenced by people’s basic set of values. Whether or not your value base is left- or right-oriented will influence your perception of what is fair. The results show that there is a significant difference in welfare attitudes between Conservative regimes, which are left-oriented, and the more rightist liberal regimes. The Social Democratic countries place themselves in-between these two. Second, I argue that regime types are decisive for amount of social spending in addition to public attitudes. In order to get a clearer view, one must see these three variables in association with each other. By plotting each country according to their values on social spending as a percentage of GDP and their aggregated welfare attitudes, we are able to see the outline of Esping-Andersen’s (1990) original regime classification. This article builds on previous research (e.g., Blekesaune 2007; Brooks and Manza 2007; Jæger 2006, 2009) and adds another variable, namely social expenditure, into the regime theory equation.

2 Regime Characteristics and the Surrounding Debate

There are several ways in which macro variables like regime type can influence public opinion; for example trough education and socialization, where the individuals are taught to respect the dominant norms and values of society; and also through day-to-day interaction with the institutions of society. The mechanism at play might be through those political parties that have been in power, and thus have been able to influence opinions. Examples are the social democratic parties in the Nordic countries and the conservatives in the United Kingdom. The parties have their programmes, members, and newspapers, which function as channels of influence. In addition, the schools and education institutions have a disciplining effect on the citizen’s attitudes. My point of commencement is the assumption that institutions affect public opinion.Footnote 1 Institutions are described as the “formal rules of the game.” They consist of the organization of rules, customs, and practice that are expressed through a country’s social insurance systems and family law (Ervasti et al. 2008). We should expect to see an isomorphy between structure and values; thus it can be said that regime types influence attitudes. Welfare regimes affect living conditions, social stratification processes, and public attitudes (Jæger 2009). Each country has a set of institutions which are decisive for how their welfare state functions. Different countries can be placed together according to the organization of their welfare policies. According to Esping-Andersen (1990), central to the classification of regimes is the level of decommodification, social stratification, and employment. Decommodification means the rights that diminish people’s status as commodities of the market forces, that is, to what extent the individual’s welfare is dependent upon the market. Social stratification concerns the importance of class structures and divisions in society, and employment has to do with the private–public mix. So Esping-Andersen’s argument was that one could group countries together by looking at the roles of the state, the market, and the family, and their role in providing welfare for its citizens. It is worth to mention that Esping-Andersen based his argument on data from the 1980s—which was the post-golden age of welfare states.

A question that has seen much debate is the one regarding which countries belong in which regime type. Esping-Andersen argues that historical events have lead to the evolution of different regime types. Class mobilization, especially of the working class is considered a milestone in this regard. He presents his three types, namely the Liberal, Conservative, and the Social-Democratic models. Catholic mass parties have been important in continental countries in the postwar period; just as the Social-Democratic parties have inserted influence on the Nordic countries. Left parties’ government participation has overall contributed greatly to the development of welfare states (Korpi 1989). Esping-Andersen’s typology was based on a study of 18 industrial democracies. On his decommodification index, the countries cluster together according to the regime classification. The decommodification index has proved difficult to replicate, yet some scholars have made thorough attempts to do so (e.g., Bambra 2006; Scruggs and Allan 2006, 2008).Footnote 2 Other researchers have produced their own measures related to that of Esping-Andersen. Menahem (2007) presented his “decommodified security ratio,” which he defines as a measure of the social states’ ability to maintain and improve the economic security of the individual. An earlier attempt was made by Osberg and Sharpe (2002). They argue that GDP is a poor indicator of economic well-being. Instead, they presented their “index of economic well-being” which consists of current effective per capita consumption flows, net social accumulation of stocks of productive resources, income distribution, and economic security. Overall, much criticism has been directed towards Esping-Andersen’s decommodification index. However, one must take into account that his classifications are based not only on this index but also by studying the past of the countries making up the Three Worlds of Welfare. The three regime types have followed different historical trajectories which influence its institutions, but which are difficult to intercept statistically.

As already mentioned, many articles have been written relating to the debate following in the wake of Esping-Andersen’s book The Tree Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. Miscellaneous boundaries for the different regime types have been drawn by different researchers and new types have been suggested (e.g., Arts and Gelissen 2002; Bambra 2007a; Bonoli 1997; Castles and Mitchell 1993; Ferrera 1996; Kangas 1994; Leibfried 1992; Wildeboer Schut et al. 2001). Some such as Ferrera (1996) and Leibfried (1992) have argued for the introduction of a Southern Mediterranean regime type; others have divided the Liberal model into two categories (Castles and Mitchell 1993; Kangas 1994). There is consensus that the Social-Democratic regime type is restricted to the Nordic countries with the exception of Iceland. Yet, some questions remain open. As mentioned above, the Liberal regime type has been divided into the Liberal and Radical models. However, considering that the classification represents a simplified way of seeing the welfare regimes of industrialized countries, in this article I will use only one Liberal grouping.

The same argument is invoked with regard to the Conservative regime, which is also retained as a single unit. The aim of using this simplified categorization is to help us see the forest and not just trees. The Netherlands is ranked between the Nordic and the Continental European countries in Esping-Andersen’s index of decommodification. This is a country where Roman Catholicism is the single largest religion, something that has influenced early social policy. It also exhibits corporatist traits which would place it in the Conservative category. Japan and South Korea are two countries separated from the other OECD countries both by geography and culture. The former has been placed in the Conservative category (e.g., by Kangas 1994), considering its score on Esping-Andersen’s (1990) index and the argument that the presence of Confucian teachings in Japanese social policy is comparable to Catholic familiarism. In addition, its social security system is also corporatist (Esping-Andersen 1999). Furthermore, Korpi (1989, p. 321) labels Japan as conservative and patriarchal. Yet, it is also argued that Esping-Andersen incorrectly positioned Japan in the Conservative category (Bambra 2006). However, Esping-Anderson (1999) also proposes the possibility of an East Asian Fourth World which includes both Japan and South Korea. His arguments are that these countries started off with economies differing substantially from that of their European and Antipodean counterparts. Even so, though Esping-Andersen acknowledges that southern European and Asian countries do not fit perfectly into his trichotomy, he stresses the need not to “water down” his original theory. This position is supported by Katrougalos (1996) who argues that the Mediterranean countries are not a distinct group, but rather a subcategory of the Conservative model.

One group that has clearly been overlooked in much of the literature is that of the former Eastern Bloc states. For the purpose of this article, Eastern Europe is added as a regime category. These countries have a shared history, going from the universalism of the Communist welfare state through a rapid change towards policies more associated with the Liberal welfare regime (Eikemo and Bambra 2008). We are then left with a pentatonic regime classification, rather than the trichotomy suggested by Esping-Andersen, or the quadchotomy proposed by Ferrera. I contribute to the existing debate by including Eastern Europe and the Asian countries in my analysis. The latter are examined both as a separate group, and as a member of the Conservative category. The literature does not give an unambiguous answer to whether or not there is a regime effect on public opinion toward questions of welfare, and it is this question that is addressed using my categorization of welfare regimes. I examine 19 OECD countries where data from the World Values Survey is available.Footnote 3 These are presented in Table 1.

The regime classifications provide us with a tool to examine differences between countries, and functions as the starting point from which to test hypotheses regarding public opinion and the welfare state. I have, based on previous theory, chosen my regime classification, taking into account eastern European and Asian OECD countries by making categories for these.

3 Public Attitudes and the Welfare State

Public opinion is a broad and general term. In this article I am investigating perceptions, that is, how the public actually observes reality. These perceptions are often colored by the individual’s values. For example, a person who has a value system based on an ideal state of equality, he will more often perceive reality as not having reached this state, and thus want more redistributive policies or more state intervention. Attitudes are often rooted in value structures, and the value structures are influenced by national contexts, like regime institutions.

For the purpose of this article leftist attitudes are synonymous with opinions that are pro collectivism, and favorable of state responsibility and equality of incomes. Rightist attitudes, on the other hand, are characterized by a preference for individualistic values and income differences, and a more negative stance towards government intervention. This set of opinions is also called welfare attitudes. Questions about income equality, government responsibility, and whether or not competition is harmful, all pertains to the same concept; how should the money in a society be distributed? In the industrialized countries governments provide economic security for their citizens, and many of them have policies to redistribute incomes toward the poor. These programmes are called welfare state policies (Blekesaune 2007). There is a general acceptance and favorability towards the welfare state in all industrialized countries. Still, there can be institutionally influenced differences between countries in one regime compared to another. The structural differences between the regime types could be reflected in different levels of support for welfare attitudes. Several researchers have tested the regime hypothesis, that is, considering that the different regime types have different histories and institutional arrangements between state, markets, and family, this would lead to systematically variation in support for redistribution or welfare values (Arts and Gelissen 2001; Bean and Papadakis 1998; Blekesaune and Quadagno 2003; Korpi 1980; Linos and West 2003; Svallfors 1997). The welfare regimes consist of formalized social policy arrangements, a shared history of class mobilization, institutionalized solidarity, and social justice beliefs. These factors should be expected to influence public discourse and individual opinion (Mau 2004). Different historic trajectories have provided different regime types, which again shape public attitudes. However, scant evidence has been found to support this hypothesized relationship. Some recent additions to the literature are: Blekesaune (2007) who showed that worsening economic conditions at the country level leads to more demand for government intervention and redistribution of income; Jæger (2006) who provided mixed support for the regime argument; and Jakobsen’s (2010) finding that the link between the size of a country’s public sector and attitudes towards privatization and individual responsibility is conditioned by people’s level of trust in institutions. Brooks and Manza (2007) find that welfare policy preferences are embedded in social factors, in the social realities, and contexts in which individuals are situated. Larsen (2006) also argues that public support reflects welfare provision. I argue that regime characteristics are decisive both for how much a country spends on welfare benefits, and also on people’s welfare attitudes. The existing literature does not unequivocally support a direct link between the frames of reference of the welfare regimes and public attitudes. Yet, my assumption is that there are differences to be found between the Liberal and Conservative regime types. This article differs in two aspects from much of the previous research. First, I use countries as my unit of analysis. Second, I include social expenditure as a variable and investigate its relation with regime types and opinions.

The policies of Sweden, Norway, Denmark, and Finland have been characterized by a willingness to include the old and the child-carers by encouraging full employment of the whole population. These are small, rich, and relatively homogenous countries. With regard to these Social-Democratic nations, support for the welfare state has proven to be robust in Denmark. It has survived economic difficulties and also attacks by bourgeois political rule (Andersen 1999). Sweden went through a period of difficulties in the 1990s when a combination of high unemployment and a major crisis in the banking system led to a large budget deficit peaking in 1994. Even so, support for the Swedish welfare state comes from most segments of its population and not only its working class (Svallfors 1999). In Norway, the welfare state has historically had a strong position in society, something that is also reflected in public attitudes (Andreβ and Heien 2001; Matheson and Wearing 1999). The same is true for Finland (Blomberg and Kroll 1999). In sum, people in the Nordic countries should be expected to hold favorable attitudes toward the welfare state. Some reservation must, however, be granted to the case of Sweden where the level of economic crisis during the 1990s lead the government to retrench the welfare state. In Edlund’s (1999) study of attitudes towards income redistribution, support for redistributive policies was found to be stronger in the United Kingdom than in Sweden.

Australia, New Zealand, Canada, the United States, Ireland, and the United Kingdom are often labeled as belonging to the liberal regime type (Esping-Andersen 1990; Ferrera 1996; Wildeboer Schut et al. 2001). These countries have their origin in the British Empire and can thus be denoted as the “Anglo-Saxon” world. With regards to social policy these countries have a tendency to favor programs that interact with the market, something we can expect to be reflected in public attitudes regarding welfare attitudes. The inclination for government to prefer private solutions for social risks along with the strong position of liberalism in these countries implies that public opinion is relatively rightist compared to other regime types. The Conservative regimes are inclined towards maintaining existing social institutions and traditional status differences. Public opinion in these countries can be expected to be less individualistic, due in part to the strong position of the Church, the workplace, and other social arrangements. In the Conservative regime people do not necessarily support “vertical” solidarity (i.e., solidarity with everyone) but rather “horizontal solidarity” (i.e., solidarity with those in similar occupational groups or with the same social status). Since most existing surveys do not make this distinction people in Conservative countries may think about horizontal solidarity when answering questions really tapping vertical solidarity (which can explain their apparently high level of support for, for example, redistribution). In sum, sentiments inside the Conservative regime type could be expected to be more leftist than their Liberal and even their Social-Democratic counterparts. Attitudes in Japan and South Korea are assumed to be influenced by their work ethics as well as by the influence of authoritarian employment practices and the strong position of religion. These factors pull in different directions when it comes to the left–right continuum of welfare attitudes. Thus, these countries can be anticipated to be neither in the leftist nor in the rightist end of the scale, but rather place themselves quite comfortably in the middle as far as attitudes toward competition, equality, and government responsibility are concerned. Eastern Europe is often overlooked in the regime classification debate as it does not fit into Esping-Andersen’s typology. These countries, such as Hungary, Poland, the Czech and the Slovak republics, all have different histories. Yet, their common denominator is that is that they all have undergone rapid economic transformation following the fall of the Iron Curtain. The role of government has decreased and the system of central planning has been dismantled and replaced by marketization and decentralization. We could expect some of the Eastern European countries to experience high levels of support for social policy as a legacy of their communist background. The political changes these states went through were to benefit the former elites (Kluegel and Mason 2004). This might have led the masses to cling onto their old economic attitudes. In other countries, however, one might experience more support for the economic transition and thus their populations will hold more rightist opinions. Both the Czech Republic and Poland bordered the Western world, and pro-liberal sentiments could more easily spread across the borders to these newly democratized countries.

In sum, based on the arguments presented above we could expect attitudes within the Liberal regime type to be rightist compared to the other countries, especially with those belonging to the Conservative category. The Social-Democratic regimes should place themselves in-between the Liberal and the leftist Conservative regimes. However, my research question is of an exploratory nature since it can also be argued that pro-welfare attitudes could be highest in Social Democratic regimes, lowest in Liberal regimes, and somewhere in between in Conservative regimesFootnote 4:

Are there cross-country differences in welfare attitudes depending on regime-characteristics?

4 Social Expenditure

Social expenditure is a measure that is quantifiable, even though it does not necessarily account for the true expense of all social welfare benefits. According to Scruggs and Allan (2006) spending does not give an adequate indication of how the welfare state affects the individual. However, it is regarded as an important instrument of welfare state redistribution (Castles and Obinger 2007). In addition, it can be argued that social expenditure, as well as public attitudes, is determined by the institutional arrangement of the state. By investigating public attitudes alone it may not be easy to see a clear effect of regime types. The same goes for social expenditure; the difference in spending between countries such as the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, and Norway might not be that pronounced. Even so, one can argue that Liberal regimes generally have little social expenditure, and this is combined with rightist welfare opinions. The Conservative regimes, on the other hand, have both higher social spending and also more favorable attitudes towards government intervention and income equality.

The Social-Democratic regime type is a special case. It consists of rich countries where social spending is heavily rooted in history and tradition. But these universal arrangement are based on the individual rather than being dependent on social institutions like the family, church, or the workplace. This, in combination with the retrenchment of the welfare state which was very evident in Sweden in the 1990s, could indicate more individualistic and pro-competition sentiments in the population, at least when juxtaposed with those of the Conservative regimes. Japan and Korea are East Asian countries which to a much lesser extent than other OECD countries have experienced unemployment, and have had strong regulations of their internal labor markets. As already mentioned, Japan resembles the Conservative regimes in many ways. Still, the low social expenditure that follows from full employment is expected to separate these two countries from the rest of the Conservative category.

The last category, Eastern Europe, is more difficult to determine. Countries in this region have gone through a transition period and differ when it comes to market influence both in social expenditure and in public opinion. Welfare regimes can be expected to procreate themselves both when it comes to citizen’s support of it and when it comes to the size of social spending. It is central to see the three variables in relation to each other. I hypothesize that by investigating the variables of public welfare attitudes and social expenditure, this can enable us to see the outline of the different regime types:

By investigating the social expenditure and welfare attitudes of OECD countries are we able to trace the contours of the different regime types?

The welfare state should not be regarded as the sum of social policies, but rather as an intricacy of legal and organizational features that are systematically blended (Arts and Gelissen 2002). It is necessary to take into account the different histories, and welfare regimes should be seen as an independent variable that can explain cross-national variation in public opinion and also in social expenditure. So, by exploring the two latter variables one should be able to find regime characteristics to be present.

5 Data

The data employed in this analysis are taken from the last four waves of the World Values Survey (1989–1993, 1994–1999, 1999–2004, and 2005–2007). Three questions from the survey have been collapsed, and the country means are used as the dependent variables in country-level regression models. The variables in question all range from 1 to 10, where high values indicate pro-welfare state attitudes, and are income equality, government responsibility, and competition harmful (Table 2).Footnote 5 These provide us with a measure of generalized welfare attitudes. The three variables have a single underlying factor. There are 19 countries where respondents have answered these questions in at least one of the waves of the World Values Survey.Footnote 6 My objective has been to include as many countries as possible in this study. Nevertheless, the ideal situation would be to utilize only one of the waves (preferably the latest), but this would drastically reduce the N in the study. The methods employed in the first part of the analysis are standard OLS regression models, where countries are units and the independent variables are dummy variables denoting the different regime types. I investigate three different regime compositions as explanatory variables. The units of analysis are country means rather than individuals. Numerous studies have already investigated individual level opinion, finding only scant evidence for the regime hypothesis. By looking at aggregated data I hope to shed some new light on the interaction between regimes, opinions, and social expenditure. The sample of respondents within each country is a sample of each population. However, when investigating the aggregated opinions I look at almost the entire population of OECD countries, not merely a sample of it. I am thus generalizing within the stochastic model theory. By following sample theory, when looking at the entire population, one should get perfect predictions. This is where the stochastic model theory becomes useful. In fact, we are generalizing from the observation made, to the process or mechanism that brings about the actual data (Gold 1969, p. 44; Henkel 1976, p. 85). Our starting point is a non-deterministic experiment implying that the results of the experiment will vary, even if we try to keep the conditions surrounding it constant. Thus, the use of confidence intervals and significance levels makes sense, even if we are looking at the entire (or close to entire) population. The lack of statistical significance indicates that the association produced by nature is no more probable than that produced by chance (Gold 1969, p. 44).

To investigate the second research question I employ data on the gross social expenditure as a percentage of GDP obtained from the OECD (2008) where I have calculated the mean value for social expenditure in the 2000s. This is done in order to give a representative picture of the level of government spending on social benefits during the last decade. As already stated, social expenditure by itself is considered to be insufficient as a proxy for welfare regimes. Yet, it can be regarded as being influenced by the type of welfare state in a given country, just as the generalized welfare attitudes can be argued to be an effect of regimes.

6 Results

The regression results are presented in Tables 3, 4, and 5. Table 3 includes four regime types: Esping-Andersen’s three original types plus one comprising the Eastern European countries, as the explanatory variable, and where the Liberal regime type is the constant term. The interpretations of the results are straightforward as it simply shows the difference in welfare attitudes from one regime compared to the reference category. A possible caveat with this analysis is the lack of control variables. Yet as this is a small-N study using country means as the dependent, I argue that this is an acceptable way of approaching my first research question. Considering that all cases are OECD countries, I have not included economic measures in the models.Footnote 7 We see that the mean of welfare attitudes in countries belonging to the Conservative regime type is significantly higher (pro welfare attitudes) than those of the Liberal regimes. The difference between the Liberal countries and the Social-Democratic and the Eastern European is negligible. Japan and South Korea are included in the Conservative category. The Eastern European countries were grouped together based on their shared history of the universal communist welfare state, and the rapid shift towards policies associated with the Liberal regime type.

Table 4 includes the Southern regime type proposed by Ferrera (1996) and others (Bambra 2007b; Bonoli 1997; Leibfried 1992), where the regime lines have been drawn based also on how social benefits are awarded and organized. I have also included an Asian category for Japan and South Korea. We see that the results from Table 3 are confirmed in Table 4. Both Continental and Southern, the two regime types that apart from Japan constitute the Conservative grouping, both have significantly higher or more leftist welfare attitudes than citizens in those countries belonging to the Liberal regime type. Table 5 follows Esping-Andersen’s original classification where Japan is a part of the Conservative regime type and South Korea is taken out of the model. Conservative regimes functions as the reference category.Footnote 8 Also here we see the significant difference between Conservative and Liberal regimes. Countries belonging to the Liberal welfare model have considerably lower score on the dependent variable, namely the mean of welfare attitudes (that is, they are more negative towards income equality and government responsibility, and more pro-competition). Social-Democratic regimes are also more rightist than Conservative regimes, a finding which is significant at the 0.10-level. One explanation of this finding is that we are investigating instrumental rather than final values. The welfare states in the Social-Democratic regimes have solved many of the problems they were supposed to, and have thus reduced the demand for further action (Inglehart 1990). Similar results were found by Jæger (2009), that is, support for redistribution was significantly higher in the Conservative regime than in the Social Democratic regime. In sum, we can conclude that there is some support for regime theory: welfare attitudes are significantly more rightist within the Liberal regime type than in Conservative countries. This is a relatively robust finding, as this postulate has been tested using different variants of the regime classification as the explanatory variable.

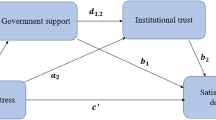

The second research question asked is whether one by looking at both social expenditure and public opinion of the OECD countries are able to see the outlines of Esping-Andersen’s three worlds. Regime type was expected to be an underlying cause of both variables. The graph presented in Fig. 1 consists of a macro indicator (Y) and the same measure of aggregated public opinion (X) that was used as the dependent in the regression models. When examining this we discover five things. First, the Liberal countries are grouped together in the left-hand corner with low social expenditure as well as little support for the generalized welfare opinions. Second, citizens of the Conservative regime type are on average more in favor of income equality, government responsibility, and less pro-competition than their Liberal counterparts (these differences were found to be statistically significant, see Tables 3, 4, and 5). We also see that the amount of money (in percentage of total GDP) spent on welfare arrangements vary widely between these countries. Japan is located close to the other Conservative regimes, at least when public attitudes are concerned. Third, Social-Democratic regimes are characterized by relatively high social spending, yet also by somewhat rightist attitudes. This is especially true for Sweden. Forth, Eastern European countries are in the middle category with regards to government expenditure, yet are scattered all over the diagram when it comes to welfare attitudes. Hungary places itself as the country most in favor of equality, government intervention, and the view that competition is harmful. Fifth, South Korea is an outlier when it comes to social spending, but its population has on average centrist welfare attitudes close to the average. Based on these findings we can draw lines tracing Esping-Andersen’s three original regimes. Eastern Europe is more difficult to classify based on the two variables in question. Figure 1 does not in itself represent a statistical test but is rather a visualization of the regime classification according to public attitudes and social expenditure. One can say that the image presented is hardly surprising as social expenditure is a part of the definition of regimes. We must also notice that the intra-group variation is almost as large as the between group variation. Even so, regimes consist of more than just social spending, and at least some extent of support is granted to the regime argument; we are able to trace the outlines of three of the regime types by investigating social expenditure and welfare attitudes.

7 Conclusion

The objective of this article is to contribute to the ongoing regime debate as well as to the study of public opinion. In order to do so I have examined the relationship between attitudes, welfare spending, and regime types. This is achieved through country level-regression models and a visual exposition of the three variables under scrutiny. To summarize, the two research questions presented in this article both pertained to regime influence on public opinion. The point of departure was Esping-Andersen’s (1990) regime classifications and an assumption that institutions influence public attitudes. Each country has a history giving them a set of institutions that imbues their societies. Countries can thus be grouped into Liberal, Conservative, Social-Democratic, and possibly Eastern European and Asian regime types. The regimes actualize themselves in public spending on welfare benefits, but the influence of institutional arrangements also reaches the public discourse. There is a debate regarding where to draw the outlines of the different regimes. My response to this was to test different variants of the regime classification. The first research question was a test of the direct effect of regimes on public opinion. I found countries that belong to the Liberal regime category to hold significantly more rightist views than those belonging to the Conservative regimes. This finding was robust as it was repeated in different models featuring various operationalizations of the Conservative category. The Social-Democratic countries were generally located in-between the other two mentioned. This finding can be explained by looking at the history of and the present institutional arrangements of the different regimes. Liberal countries have a tendency to favor private solutions for social risks, and also have a strong tradition for liberalism. The Conservative regime type, on the other hand, has less emphasis on individualistic values. These continental regimes place more weight on social institutions such as the church, family, and workplace. Thus attitudes tend to be less individualistic. The Social-Democratic regime type is universalistic, yet individualistic in its nature. It has been called a blend of liberalism and socialism, and with regards to welfare attitudes the countries in the category are located in-between those of the Liberal and Conservative regimes.

As for the second research question, there is a lack of previous studies investigating both social expenditure and welfare attitudes as dependent of regime characteristics. Most studies treat social expenditure as an indicator of regime types and not as an outcome.Footnote 9 I have tried to fill this gap in the literature, and by doing so, rendering some support to Esping-Andersen’s (1990, 1999) theory. I believe the findings in this article have implications both regarding to public opinion and welfare regime research. First, we see that the institutional arrangements of a country can play a part in forming the opinions of its citizens. Countries with a Liberal welfare organization produce values that are significantly different from that of Conservative countries. Second, by plotting countries according to their welfare attitudes and social spending, we can view the contour of three of the welfare regimes. The Eastern European countries, on the other hand, do not group together in the graph. This could be due to the differences in their proximity to Western Europe. We see this in the results for the Czech Republic and Poland which are located at the pro-competition end of the scale, while the Slovak Republic and especially Hungary score high on welfare attitudes. South Koreans spend little on social benefits partly because they are blessed with low unemployment and make use of a private employment insurance system. Efforts to test the regime hypothesis on public opinion alone have given mixed results. By including social spending into the equation I hope to have provided the reader with a more nuanced picture: that is, we can identify welfare regimes by seeing the interplay between social expenditure and welfare attitudes. Lastly, I must emphasize that this has been a country-level study with the employment of aggregated individual data. Future research would be advised to investigate individual level attitudes and how these are influenced by both macro- and micro-level factors.

Notes

It can also be argued that the causation goes the other way. For example, the egalitarian economic and societal structure, history, and values of the Nordic countries laid the foundation of the modern welfare state. In addition, countries have different cultures external experiences, and even public preferences. Even so, my argument is that the relationship between institutions and modern day attitudes is to a large degree one where the former influences the latter.

A replication using data from 1998 to 99 was made by Bambra who questions the existence of the Three Worlds of Welfare. Similar conclusions were drawn by Scruggs and Allan.

More information about the WVS can be found at http://www.worldvaluessurvey.org. These datasets are made available through the Norwegian Social Science Data Services (NSD). Neither Ronald Inglehart, WVS nor NSD are responsible for the analysis or interpretations made in this article.

See Jæger (2009) for a discussion on regime ranking.

The population is randomly drawn individuals from the countries listed in Table 2. The exact wording of the questions used in the analysis is as follows: Incomes should be made more equal versus We need larger income differences as incentives for individual effort; The government should take more responsibility to ensure that everyone is provided for versus People should take more responsibility to provide for themselves; and Competition is good. It stimulates people to work hard and develop new ideas versus Competition is harmful. It brings out the worst in people.

The questions that make up the index were not available in the first wave of the World Values Survey. I only investigate high-income economies, with the exception of Poland which is included due to their presence in the Eastern European category.

Models including the Human Development Indicator (HDI) (UNDP 2007) as a control are presented in the Appendix. The effect of regime type does not differ significantly from the main models when including this variable, except for Model 4. Here the effect of Continental regime is close to significant and Southern regime is not significant. This is not unsuspected, as these latter only consist of two countries. Altogether, the results are robust.

This is done in order to see if there were any significant differences between the Conservative and the Social-Democratic models.

See Brooks and Manza (2006) for a discussion about the feedback between attitudes, policies, and expenditure.

References

Aalberg, T. (2003). Achieving justice: Comparative public opinions on income distribution. Boston, MA: Brill Leiden.

Andersen, J. G. (1999). Changing labour markets, new social divisions and welfare state support: Denmark in the 1990s. In S. Svallfors & P. Taylor-Gooby (Eds.), The end of the welfare state? Responses to state retrenchment (pp. 13–33). London: Routledge.

Andreβ, H.-J., & Heien, T. (2001). Four worlds of welfare state attitudes? A comparison of Germany, Norway, and the United States. European Sociological Review, 17(4), 337–356.

Arts, W., & Gelissen, J. (2001). Welfare states, solidarity and justice principles: Does the type really matter? Acta Sociologica, 44(4), 283–299.

Arts, W., & Gelissen, J. (2002). Three worlds of welfare capitalism or more? A state-of-the-art report. Journal of European Social Policy, 12(2), 137–158.

Bambra, C. (2006). Decommodification and the worlds of welfare revisited. Journal of European Social Policy, 16(1), 73–80.

Bambra, C. (2007a). ‘Sifting the wheat from the chaff’: A two-dimensional discriminant analysis of welfare state regime theory. Social Policy and Administration, 41(1), 1–28.

Bambra, C. (2007b). Defamilisation and welfare state regimes: A cluster analysis. International Journal of Social Welfare, 16(4), 326–338.

Bean, C., & Papadakis, E. (1998). A comparison of mass attitudes towards the welfare states in different institutional regimes, 1985–1990. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 10(3), 211–236.

Blekesaune, M. (2007). Economic conditions and public attitudes to welfare policies. European Sociological Review, 23(3), 393–403.

Blekesaune, M., & Quadagno, J. (2003). Public attitudes toward welfare state policies: A comparative analysis of 24 nations. European Sociological Review, 19(5), 415–427.

Blomberg, H., & Kroll, C. (1999). Who wants to preserve the ‘Scandinavian service state’? Attitudes to welfare services among citizens and local government elites in Finland 1992–96. In S. Svallfors & P. Taylor-Gooby (Eds.), The end of the welfare state? Responses to state retrenchment (pp. 52–56). London: Routledge.

Bonoli, G. (1997). Classifying welfare states: A two-dimension approach. Journal of Social Policy, 26(3), 351–372.

Brooks, C., & Manza, J. (2006). Social policy responsiveness in developed democracies. American Sociological Review, 71(3), 474–494.

Brooks, C., & Manza, J. (2007). Why welfare states persist: The importance of public opinion in democracies. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Castles, F. G., & Mitchell, D. (1993). Worlds of welfare and families of nations. In F. G. Castles (Ed.), Families of nations: Patterns of public policy in western democracies (pp. 93–128). Aldershot: Dartmouth.

Castles, F. G., & Obinger, H. (2007). Social expenditure and the politics of redistribution. Journal of European Social Policy, 17(3), 206–222.

Edlund, J. (1999). Progressive taxation farewell? Attitudes to income redistribution and taxation in Sweden, Great Britain and the United States. In S. Svallfors & P. Taylor-Gooby (Eds.), The end of the welfare state? Responses to state retrenchment (pp. 106–134). London: Routledge.

Eikemo, T. A., & Bambra, C. (2008). The welfare state: A glossary for public health. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 62(1), 3–6.

Ervasti, H., Fridberg, T., Hjerm, M., Kangas, O., & Ringdal, K. (2008). The Nordic model. In H. Ervasti, T. Fridberg, M. Hjerm, & K. Ringdal (Eds.), Nordic social attitudes in a European perspective (pp. 1–21). Cheltenham: Elgar.

Esping-Andersen, G. (1990). The three worlds of welfare capitalism. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Esping-Andersen, G. (1999). Social foundations of postindustrial economies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ferrera, M. (1996). The southern model of welfare in social Europe. Journal of European Social Policy, 6(1), 17–37.

Ginsburg, N. (1979). Class, capital and social policy. London: Macmillan.

Gold, D. (1969). Statistical tests and substantive significance. American Sociologist, 4(1), 42–46.

Henkel, R. E. (1976). Tests of significance. Beverly Hills: Sage.

Inglehart, R. (1990). Culture shift in advanced industrial society. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Jæger, M. M. (2006). Welfare regimes and attitudes towards redistribution: The regime hypothesis revisited. European Sociological Review, 22(2), 157–170.

Jæger, M. M. (2009). United but divided: Welfare regimes and the level and variance in public support for redistribution. European Sociological Review, 25(6), 723–737.

Jakobsen, T. G. (2010). Public versus private: The conditional effect of state policy and institutional trust on mass opinion. European Sociological Review, 26(3), 307–318.

Kangas, O. (1994). The politics of social security: On regressions, qualitative comparisons and cluster analysis. In T. Janoski & A. M. Hicks (Eds.), The comparative political economy of the welfare state (pp. 346–364). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Katrougalos, G. S. (1996). The South European welfare model: The Greek welfare state in search of an identity. Journal of European Social Policy, 6(1), 39–60.

Kaufmann, F.-X. (2000). Towards a theory of the welfare state. European Review, 8(3), 291–312.

Kluegel, J. R., & Mason, D. S. (2004). Fairness matters: Social justice and political legitimacy in post-Communist Europe. Europe-Asia Studies, 56(6), 813–834.

Korpi, W. (1980). Social policy and distributional conflict in the capitalist democracies: A preliminary comparative framework. West European Politics, 3(3), 296–316.

Korpi, W. (1989). Power, politics, and state autonomy in the development of social citizenship: Social rights during sickness in eighteen OECD countries since 1930. American Sociological Review, 54(3), 309–328.

Larsen, C. A. (2006). The institutional logic of welfare attitudes: How welfare regimes influence public support. Aldershot: Ashgate.

Leibfried, S. (1992). Towards a European welfare state? On integrating poverty regimes into the European community. In Z. Ferge & M. West (Eds.), Social policy in a changing Europe (pp. 245–279). Frankfurt am Main: Campus Verlag.

Linos, K., & West, M. (2003). Self-interest, social beliefs, and attitudes to redistribution. European Sociological Review, 19(4), 393–409.

Matheson, G., & Wearing, M. (1999). Within and without: Labour force status and political views in four welfare states. In S. Svallfors & P. Taylor-Gooby (Eds.), The end of the welfare state? Responses to state retrenchment (pp. 135–160). London: Routledge.

Mau, S. (2004). Welfare regimes and the norms of social exchange. Current Sociology, 52(1), 53–74.

Menahem, G. (2007). The decommodified security ratio: A tool for assessing European social protection systems. International Social Security Review, 60(4), 69–103.

OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development). (2008). Social expenditure database. Available at www.oecd.org/els/social/expenditure.

Osberg, L., & Sharpe, A. (2002). An index of economic well-being for selected OECD countries. Review of Income and Wealth, 48(3), 24–62.

Scruggs, L. A., & Allan, J. P. (2006). Welfare-state decommodification in 18 OECD countries: A replication and revision. Journal of European Social Policy, 16(1), 55–72.

Scruggs, L. A., & Allan, J. P. (2008). Social stratification and welfare regimes for the twenty-first Century: Revisiting the three worlds of welfare capitalism. World Politics, 60(4), 642–664.

Svallfors, S. (1997). Worlds of welfare and attitudes to redistribution: A comparison of eight Western nations. European Sociological Review, 13(3), 233–304.

Svallfors, S. (1999). The middle class and welfare state retrenchment: Attitudes to Swedish welfare policies. In S. Svallfors & P. Taylor-Gooby (Eds.), The end of the welfare state? Responses to state retrenchment (pp. 34–51). London: Routledge.

Titmuss, R. M. (1958). Essays on ‘the welfare state’. London: George Allen & Unwin.

UNDP (United Nations Development Program). (2007). Human development indices. Available at: http://hdr.undp.org/en/statistics/.

Wildeboer Schut, J.-M., Vrooman, C., & de Beer, P. (2001). On worlds of welfare: Institutions and their effects in 11 welfare states. Walferdange: LIS.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Ola Listhaug, Jon S. E. Jakobsen, Audun Fladmoe, Tor-Eirik Olsen, John G. Taylor, and the anonymous referee for valuable input in the process of writing this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jakobsen, T.G. Welfare Attitudes and Social Expenditure: Do Regimes Shape Public Opinion?. Soc Indic Res 101, 323–340 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-010-9666-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-010-9666-8