Abstract

A number of studies have suggested breastfed infants have improved bonding and attachment or cognitive development outcomes. However, mechanisms by which these differences might develop are poorly understood. We used maternal time use data to examine whether exclusively breastfeeding mothers spend more time in close interactive behaviors with their infants than mothers who have commenced or completed weaning. Mothers (188) participating in a time use survey recorded infant feeding activities for 24 h over a 7 day period using an electronic device. Tracking was conducted at 3, 6, and 9 months postpartum. Data was collected for maternal activities including infant feeding and time spent in emotional care. The mothers of exclusively breastfed infants aged 3–6 months fed them frequently and total time spent in breastfeeding averaged around 17 h a week. Maternal time spent in emotional care was also substantial, and found to correlate positively with time spent breastfeeding. Exclusively breastfed infants received greatest amounts of emotional care from their mother, and exclusively formula fed infants the least. Mixed fed infants received more emotional care time than formula fed infants, but less than fully breastfed infants. These findings may help explain the differential cognitive developmental outcomes reported in the medical literature for breastfed and non breastfed infants.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Breastfeeding is the biological norm for human infants, and is widely recognised to promote appropriate infant health and development. Health authorities consider optimal feeding for infants to be 6 months of exclusive breastfeeding, followed by introduction of appropriate complementary foods, and continued breastfeeding into toddlerhood (National Health and Medical Research Council 2003; WHO 2002; World Health Assembly (Fifty-Fourth) 2001).

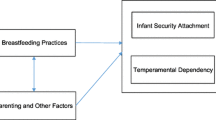

There is now strong evidence of cognitive development effects of 3–6 IQ points for children who were exclusively breastfed for 4 months or more, compared to those exclusively breastfed for less than 3 months (Kramer et al. 2008). Research has also shown a link between breastfeeding and attachment (Britton et al. 2006). Mothers who breastfeed for a longer duration are found to have stronger attachment with their infant, and greater sensitivity towards their infant at 3 months. Infant feeding practices have also been shown to affect longer-term psychosocial development (Fergusson and Woodward 1999).

The biological mechanism behind these effects is unclear. Biochemical components of human milk, such as fatty acids and hormones may have a role in brain development and infant attachment (Oddy 2006). It is difficult in observational studies to establish whether these effects are due to those who sustain breastfeeding being different from those who do not. An alternative possibility is that lactation and breastfeeding alter the behavior of mothers. Evidence from animal and human studies is that lactation hormones increase proximity seeking and maternal behaviors including nurturing of young (Tu et al. 2005; Uvnas-Moberg and Petersson 2005). There is little research assessing concrete patterns of mother-infant interactions (Golding et al. 1997). Using a unique and innovative Australian dataset, we ask whether exclusively breastfeeding mothers spend more time in close interactive behaviors with their infants than mothers who have commenced or completed weaning.

2 Methods, Data and Approach

The Australian Time Use Survey of Australian Mothers (TUSNM) was conducted from April 2005 to April 2006. A nationwide sample of 188 mothers recorded their all their activities, including feeding, over a 7-day period by pressing coded buttons on an electronic TimeCorder® device. Some mothers tracked at different stages, yielding 344 data sets with 2,311 diary days. Activities were based on those used in the Australian Time Use Survey plus additional sub-categories of childcare activity.

We look at maternal time spent in infant feeding and emotional care activity at 3, 6 and 9 months postpartum to see how much time is involved in exclusive breastfeeding, and to find out whether different infant feeding practices are linked to different time investments by mothers in emotional care. First, we examined the frequency and amount of time mothers spent feeding exclusively breastfed infants from 3 to 9 months, and the relationship with other interactive care activities including soothing, holding or cuddling the infant (‘emotional care’). We then compared the results for those infants also fed solids, and for those non-breastfed. Finally, we looked at the broad pattern of time use of new mothers, and compared time spent on total childcare by mothers who are breastfeeding with those who have commenced weaning.

3 Results

Table 1 reports weekly hours of breastfeeding for mothers who were exclusively breastfeeding at 3 or 6 months, and for those mothers breastfeeding with solids at 6 and 9 months. Table 1 shows that time spent breastfeeding is high in the early months, but decreases dramatically over the first nine months of the infant’s life. For optimally breastfeeding mothers, breastfeeding occupies 17 h a week at 3 months, with the infant feeding 7.4 times in a 24-hour period, and a similar time at 6 months. Notably, exclusively breastfeeding mothers who had introduced solids by 6 months were spending substantially less time breastfeeding than the exclusively breastfeeding mothers (11 h) at 6 months. The 9 month old breastfed babies on solids spent a similar number of hours a week breastfeeding to those at 6 months. These results suggest that feeding time and frequency depend on exclusivity of breastfeeding more than on the age of the infant.

Maternal time spent in emotional care correlates strongly with time spent breastfeeding. Total time spent on emotional care by mothers of exclusively breastfed infants is about 11–12 h per week. Infants elicit frequent episodes of emotional care from their mothers (7 times a day), and were cuddled or held for an average of around 15 min on each occasion. This diminished as weaning commenced.

The bottom of Table 1 shows comparable data for ‘emotional care’ activity among breastfed infants aged 3–9 months. This also shows a pattern of high time use, and reduced maternal time commitment once the infant has ended the exclusive breastfeeding phase.

Again, the total time and frequency of emotional care appears to be a function of exclusivity of breastfeeding rather than of age. Breastfeeding infants receiving solids at 6 or 9 months received less emotional care time than exclusively breastfed infants, but more than non-breastfed infants. The formula-fed infants on solids and aged 3–9 months received an average of 3.8 h of emotional care time a week (n = 23) compared to 7.0 h (n = 183) among breastfeeding infants on solids (not presented). This relationship also holds for each age group of infants.

The evident synchrony in the timing of breastfeeding and emotional care during the day suggests a relationship between these activities—although the causal direction is not clear. Breastfeeding may encourage more emotional care, or alternatively, providing more emotional care time may increase the likelihood of a mother optimally breastfeeding throughout the infant’s first 9 months. This is supported by the correlation plot of total weekly time spent in breastfeeding and in emotional care shown in Fig. 1.

Table 2 shows time spent in all interactive feeding activities plus emotional care time. Prior to weaning from exclusive breastfeeding, around 28–29 h a week of maternal time is spent on highly interactive feeding and emotional care time. As evident in Table 2, introducing solid foods or formula substantially reduces the breastfeeding mother’s time spent on interactive feeding and emotional care. The more substitute foods are introduced, the less time the mother spends on interactive feeding or emotional care activity. Older, breastfed infants on solids experience less interactive time with their mother (17–19 h) than exclusively breastfed infants. Exclusively formula feeding babies on solids have the least interactive feeding or emotional care time with their mother (9–12 h).

It is possible that other forms of interactive childcare substitute for breastfeeding or other interactive feeding or emotional care activity. However, Table 2 shows that the differences arising from feeding and emotional care activity are not compensated by other interactive childcare. Breastfeeding mothers spent more time on childcare than non-breastfeeding mothers, mainly due to additional feeding time and emotional care time. The less exclusive the breastfeeding, and the older the infant, the less time spent on childcare.

4 Discussion and Conclusions

Maternal contact with the infant in the early postnatal period is important in developing the mother–child relationship, providing the opportunity for the infant to shape maternal behaviour and interactions with the mother, with implications for developmental outcomes. Breastfeeding obviously demands a degree of maternal-infant proximity and maternal investment that is not necessary for formula feeding. We suggest that contact and time with the mother as the infant becomes older may also be important to the formation of attachment, and to cognitive development through physiological and psychological mechanisms. The dynamic development of maternal style and attachment in interaction with the baby may be an important mediating factor in the neurological and cognitive development disadvantage of infants who are not breastfed. This finding warrants further investigation comparing larger populations of exclusively breastfed and exclusively formula fed infants than was possible in this study. Paid employment may impact on available time for emotional care of infants, and so may the presence of other young children. This too is an important area for future research.

References

Britton, J. R., Britton, H. L., & Gronwaldt, V. (2006). Breastfeeding, sensitivity, and attachment. Pediatrics, 118, e1436–e1443.

Fergusson, D. M., & Woodward, L. J. (1999). Breast feeding and later psychosocial adjustment. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology, 13, 144–157.

Golding, J., Rogers, I. S., & Emmett, P. M. (1997). Association between breast feeding, child development and behaviour. Early Human Development, 49(Suppl), S175–S184.

Kramer, M. S., Aboud, F., Mironova, E., et al. (2008). Breastfeeding and child cognitive development: New evidence from a large randomized trial. Archives of General Psychiatry, 65, 578–584.

National Health and Medical Research Council. (2003). Dietary guidelines for children and adolescents in Australia incorporating the infant feeding guidelines for health workers. Canberra: National Health and Medical Research Council.

Oddy, W. H. (2006). Fatty acid nutrition, immune and mental health development from infancy through childhood. In J. D. Huang (Ed.), Frontiers in nutrition research. New York: Nova Science Publishers.

Tu, M. T., Lupien, S. J., & Walker, C. D. (2005). Measuring stress responses in postpartum mothers: perspectives from studies in human and animal populations. Stress, 8, 19–34.

Uvnas-Moberg, K., & Petersson, M. (2005). Oxytocin, a mediator of anti-stress, well-being, social interaction, growth and healing. Z Psychosom Med Psychother, 51, 57–80.

World Health Assembly (Fifty-Fourth) (2001) Infant and young child nutrition: Resolution 54.2 Geneva, May, 2001.

WHO. (2002). Infant and young child nutrition global strategy on infant and young child feeding. Geneva: World Health Organization.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Smith, J.P., Ellwood, M. Feeding Patterns and Emotional Care in Breastfed Infants. Soc Indic Res 101, 227–231 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-010-9657-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-010-9657-9