Abstract

The AsiaBarometer survey of 1,023 respondents shows Life in Korea is highly modernized and digitalized without being much globalized. Despite the modernization and digitalization of their lifestyles, ordinary citizens still prioritize materialistic values more than post-materialistic values, and they remain least satisfied in the material life sphere. A multivariate analysis of the Korean survey reveals that their positive assessments of their standard of living and marriage are the most powerful influences on the quality of life they experience. Remarkable improvements in the objective conditions of life for the past three decades have failed to transform Korea into a nation of well-being.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The Korean peninsula has been divided into the two ideologically competing halves of North and South Korea since 1945 when it was liberated from Japanese colonial rule. For the past five decades, North Korea has remained an impoverished communist state and closed to the outside world. During the same period, South Korea, in striking contrast, has successfully been transformed into an affluent liberal democracy standing at the forefront of the global movement to develop democracy and capitalism in parallel. This article is intended to examine how socioeconomic modernization, democratization, and globalization have affected South Korea (Korea hereafter) as a place to live and how those changes have affected the quality of life South Korean desire and experience.

1 Introduction: Characteristics of Korean Life

Demographically, Korea is a densely populated country with 48 million people living in the land area of 38,000 square miles. It is also a highly urbanized society with 80% of the population living in urban areas. The annual rate of population growth dropped from 0.8% in 2000 to 0.3% in 2006. Births per woman declined from 1.5 in 2000 to 1.1 in 2006 (World Bank 2007). In 2005, people aged 14 and below accounted for 19% of the population; people aged 15 to 64, for 72%; and people aged 65 and more, for 9% (Korea National Statistical Office 2005). Due to such declines in fertility and mortality rates, Korea is becoming an aging society. Recently, the numbers of migrant workers and mixed marriages have slowly increased. Nonetheless, Korea still remains ethnically and linguistically homogeneous.

Korea is a religiously diverse society. Buddhism, Protestantism, and Catholicism are three major religions in Korea (Korea National Statistical Office 2005). In 2005, 23% of the Korean people were Buddhists; 18%; Protestants; and 11%, Catholics. Meanwhile, 46% of the Korean people profess no religion. Despite its profound impact on every aspect of Korean life, few profess Confucianism.

Economically, it has transformed from one of the world’s poorest countries into an economic powerhouse; half the geographic size of Great Britain, Korea is now the thirteenth largest economy in the world. In 1996 it became the twenty-ninth member country of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the exclusive club of developed countries. Recovering from the economic crisis in 1997, Korea has been on track to resume steady economic growth. Its economy grew at a rate of 8.5% in 2000 and 5.0% in 2006 (World Bank 2007).

Recently, however, income equality has deteriorated. According to the Korea National Statistical Office (2007), the Gini coefficient, a measure of inequality of income distribution with values between 0 (perfect equality) and 1 (perfect inequality), steadily rose from 0.304 in 2003 to 0.313 in 2005 to 0.329 in 2007. Yet the unemployment rate remains stable: it was 3.6% in 2003, 3.7% in 2005, and 3.2% in 2007. The average hours worked per year per employed person in Korea were 2,520 in 2000 and 2,357 in 2006. Among the OECD countries, Korea has the most average hours worked (OECD 2008).

With rising economic affluence, the human condition in Korea has improved significantly. According to the latest Human Development Report (UNDP 2007/8), in 2005 the life expectancy at birth was 77.9 years; the combined primary, secondary, and tertiary gross enrollment ratio was 96%; and GDP per capita measured by purchasing power parity was US$22,029. As a result, Korea received a score of 0.921 on the human development index, ranking twenty-sixth worldwide. The Korean people as a whole live longer and healthier lives and have higher levels of education and a more decent standard of living than the average world citizen.

Politically, Korea transformed its regime into a representative democracy after decades of authoritarian rule, which had often been justified as necessary for national security and economic growth. Its current political regime is characterized by free and fair elections, universal suffrage, multiparty competition, civil and political rights, and a free press. In 2007, Freedom House awarded Korea a combined score of 1.5 on its seven-point political rights and civil liberties scale, which runs from 1 (most free) to 7 (least free) (Freedom House 2007). This combined score places Korea in line with the old liberal democracies in the West.

On the 2007 World Bank Governance Indicators, a scale with scores ranging from −2.5 to +2.5, Korea received positive ratings in 2006 for all six dimensions of governance: voice and accountability (+0.71), political stability (+0.42), government effectiveness (+1.05), regulatory quality (+0.70), rule of law (+0.72), and control of corruption (+0.31) (Kaufman et al. 2007). Although these scores show room for improvement, Korea has clearly come far in terms of democratic strength, effectiveness, and constitutionalism.

Legally, Korea aspires to be a land of equal opportunity. Yet it is still far short of this ideal. According to the Gender Gap Index 2006, which had scores ranging from 0 (inequality) to 1 (equality), Korea ranked ninety-second out of 115 countries, with a score of 0.616 (World Economic Forum 2006). There is notable gender inequality in professional and technical workers, as well as in enrollment in tertiary education. Wider gender inequality exists in terms of political empowerment; for example, those in parliament and ministerial positions are far less likely to be female. In short, Korea remains a male-dominated society.

Technologically, Korea is emerging as a global leader in information and communication technology, and it is one of the most digitalized countries in the world. The number of Internet users per 100 persons increased by nearly twice in just six years, from 40.5 in 2000 to 70.5 in 2006 (World Bank 2007). In 2006, Korea led the OECD in broadband penetration rate, with 29 subscribers per 100 habitants, just behind Denmark (31.9), the Netherlands (31.8), and Iceland (29.7) (OECD 2006). According to the International Telecommunication Union’s Digital Opportunity Index, Korea ranks 1st out of 181 countries, indicating that the Koreans have better access to a variety of digital information than do any other peoples in the world.

These economic, political, and social transformations have altered objective circumstances in which the Korean people live. Objective life circumstances, however, cannot be equated with subjective life experiences (Campbell 1972). Being aware of this, we focus on the quality of life directly experienced by the Korean people. After briefly exploring their lifestyles and value priorities, we focus on their perceptions of quality of life from a number of different perspectives. First, we examine the overall feelings of happiness, enjoyment, and achievement that the Korean people experience. Second, we investigate their feelings of satisfaction and dissatisfaction in a variety of specific life domains. Third, we ascertain the relationships of these specific assessments with global quality of life. Finally, we highlight key findings and explore their theoretical implications.

2 Profile of Respondents

The data used in this paper was pulled from the AsiaBarometer Survey (ABS hereafter) in Korea collected during the months of July and August in 2006. It is a national sample survey of 1,023 adults (aged 20 to 69), who were personally interviewed. Before presenting key findings, we describe the sample in terms of gender, age, marital status, educational attainment, household income, and residential community.

First, half (50%) of our respondents are male and the other half (50%) are female. Second, one-fifth (20%) of the respondents are in their 20s; a quarter (26%), in their 30s; another quarter (24%), in their 40s; less than one-fifth (17%), in their 50s; and about one-tenth (12%), in their 60s.Footnote 1 Notable is that nearly half (46%) are under 40. Third, three-quarters (75%) of the respondents are married; one-fifth (21%), single; and one-twentieth (5%), either divorced, separated, or widowed. Fourth, one-fifth (19%) of the respondents have no high school education; more than two-fifths (43%), a high school education; and two-fifths (38%), a college education. Fourth, half (49%) of the respondents have a household annual income of less than KW 30,000,000; one-third (32%), between KW 30,000,000 and KW 50,000,000; and one-fifth (18%), more than KW 50,000,000 (The average annual exchange rate in 2006 was US$1 equals 1,000 Korean won). Lastly, half (48%) of the respondents live in large cities with a population of at least one million; two-fifths (41%), in small or medium-sized cities; and only one-tenth (11%), in rural areas.

Our sample of respondents appears to match the general population with respect to major characteristics. According to the Population and Housing Census (Korea National Statistical Office 2005), the total population aged 20 to 69 in 2005 stands at 32,269,632. Of this population, 50% are men and 50% are women. Those aged 20 to 29 constitute 23%; those aged 30 to 39, 25%; those aged 40 to 49, 25%; those aged 50 to 59, 16%; and those aged 60 to 69, 11%. Of the population aged 20 to 69, 66% are married; 26% are single; and 8% are either divorced or widowed. Those having a household average monthly income of less than KW 2,500,000 make up 48%; those between KW 2,500,000 and KW 4,000,000, 30%; and those more than KW 4,000,000, 22%. While our sample slightly underrepresented people aged 20 to 29, the unmarried, and high-income people, it largely matched the sub-samples of the total population in terms of gender, age, marital status, and income.

In the ensuing sections these six demographic variables will be used to disaggregate the population in order to discover any differences that might exist among them in terms of lifestyles, value priorities, and quality of life.

3 Lifestyles

For the last four decades or so, Korea has experienced rapid progress in industrialization and urbanization, two key features of modernization. These socioeconomic changes have undoubtedly reshaped the Korean people’s worldviews and ways of life. More recent changes such as democratization, globalization, and digitalization have further challenged traditional values and lifestyles. In this section, we examine how the Korean people live their lives in wake of industrialization, secularization, digitalization, and globalization. After briefly exploring various aspects of domestic life, we identify four lifestyles—modern, religious, digital, and global—and examine whether the prevalence of these lifestyles varies across the different population segments.

3.1 Family Life

As Korea has moved from a rural society to one that is largely urban, its family system has gradually transformed from the extended family to the nuclear family, which typically consists of parents and their children (Yang 2003). It is increasingly less common for urban Koreans to live in households with three generations or for married children to live with their parents.

The 2006 ABS asked respondents to describe their family structure. More than two-thirds (69%) live in a two-generation household with an unmarried child or children. Very few of the respondents, only 4%, live in a two-generation household with a married child or children. One-tenth (11%) live in a household with a married couple only. Another one-tenth (9%) live in a three-generation household. Those living in a single-person household make up 6%. These findings show that the nuclear family is the dominant form of family structure in Korea today.

The 2006 ABS measured family size by asking respondents for the number of persons living in their household. The Korean family has an average of 3.6 persons, largely consisting of the parents and one or two children. Of those living in a two-generation household with an unmarried child or children, 60% have four persons in their households, 27% three persons, and 10% five persons. Families with two children are most common and families with one child are almost three times as common as families with three children.

Apartments, which tend to provide convenient heating, a modern kitchen, easy maintenance, and security, are an increasingly popular type of housing in Korea (Son et al. 2003). Young and old people alike tend to prefer apartments rather than detached houses. According to the Population and Housing Census (Korea National Statistical Office 2005), in 1985 the number of apartments accounted for only 14% of all housing units, but by 2005, it had risen to 53%. Reflecting this trend, the 2006 ABS shows that a majority (59%) of the Korean people live either in terraced houses, units in apartments, or condominium complexes. In contrast, a minority (41%) live in detached or semidetached houses, which used to be the dominant form of housing. The proportion of families residing in their own homes appears to be high despite housing shortages in urban areas. A large majority (79%) live in their own housing units. Only a small minority (21%) lives in rented housing units, and most of these units are rentals with long-term leases rather than monthly payments.

The 2006 ABS asked respondents to select up to two of seven dining styles of eating breakfast and dinner, respectively. For the morning meal, an absolute majority (89%) have home-cooked food. Only a small minority (12%) have instant foods. It is uncommon for ordinary Koreans to buy prepared meals for breakfast (7%). It is also rare for ordinary Koreans to have breakfast in restaurants (5%) or at food stalls (2%). A small minority (8%) tend to skip breakfast.

For the evening meal, nearly everyone (94%) has home-cooked food. A considerable minority (39%) tend to have dinner in restaurants. It is uncommon for ordinary Koreans to buy prepared meals (7%), to eat instant foods (6%) or to eat out at food stalls (2%) for dinner. One of the expected findings is that ordinary Koreans go out for dinner more often than they do for breakfast. Another is that instant foods tend to be served for breakfast rather than for dinner. It seems that young and unmarried people are less likely to eat home-cooked foods than are old and married people. Furthermore, the former are more likely to skip breakfast than are the latter.

The 2006 ABS asked respondents about their favorite food. Not surprisingly, the Korean people’s most favorite food is kimchi (67%). It is followed by sushi (43%), Beijing duck (23%), pizza (21%), sandwiches (15%), dim sum (13%), instant noodles (13%), and hamburgers (12%), in that order. This finding shows that Japanese and Chinese cuisines tend to suit Korean palates more than do Western ones. Despite their popularity among young people, fast foods such as pizza and hamburgers, which are often branded as unhealthy, are generally less popular than Chinese foods, such as Beijing duck and dim sum. Thai, Indian, and Vietnam foods such as tom-yum goong (11%), curry (10%) and pho (9%) are the least popular. Overall, Korean palates still remain partial to East Asian culinary cultures.

3.2 Modern Life

One of the key features of modern industrial societies is their provision of modern conveniences such as electricity, running water, heating and cooling, flush toilet, television, phones, dishwashers, and so forth. Most of these utilities and appliances constitute necessities, not luxuries, without which people cannot live a modern life. To what extent are these modern staples available to ordinary Koreans?

The 2006 ABS asked respondents whether their households have access to the following public utilities: a public water supply, electricity, liquefied petroleum gas or LPG piped gas, fixed-line phone, facsimile, and cable TV. More than nine in ten households have all of these modern conveniences except facsimile. More specifically, nearly every household has access to electricity (100%), gas for cooking (99%), and fixed-line phones (97%). An absolute majority have access to the public water supply (94%), mobile phones (95%), and cable TV (93%). In contrast, only a small minority (10%) has facsimile, which is not considered a household staple in Korea. This finding shows that nearly every household in Korea has the basic necessities for a modern life.

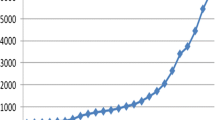

To estimate the level of modern life respondents have attained, we counted the number of public utilities each respondent could access at home and constructed a three-point index. The low level indicates having four utilities or fewer;Footnote 2 the medium level, five utilities; and the high level, six utilities or more. As seen in Fig. 1, only a few (3%) have the use of four utilities or fewer, and a small minority (16%) has five utilities. In contrast, an absolute majority (82%) have the use of six utilities or more. Those living high levels of modern life outnumber those living low levels by a huge margin of 79 percentage points. This finding shows that Korea is unquestionably a developed nation of modern life.

Table 1 shows levels of modern life in major segments of the population. There is no notable difference between men and women or between married and unmarried people. Yet other demographic variables appear to make some difference in levels of modern life. Older people, people with no high school education, and low-income people are the least likely to live a modern life. Expectedly, the larger the community in which people live, the more likely they are to live a modern life. Barely over half (56%) of rural residents live high levels of a modern life, while nine-tenths (90%) of large-city dwellers do. Overall, those who are old, less educated, and/or rural residents are least likely to lead a modern life, while those who are young, better educated, and/or urban residents are most likely to do so.

3.3 Religious Life

Another key feature of modern industrial societies is cultural secularization. This process leads to the erosion of religious practices and the loss of identification with religious institutions. To what extent are ordinary Koreans detached from religious practices and affiliation?

The 2006 ABS asked respondents whether they belong to any particular religion. More than half (56%) identify with some religion, either Catholicism (8%), Protestantism (25%), or Buddhisism (22%). People who have no religious affiliation constitute a plurality of two-fifths (43%). Those who have a religious affiliation outnumber those who do not by a small margin of 13 percentage points. The 2006 ABS also asked respondents how often they pray or meditate. One-third (32%) said that they pray or meditate “daily” or “weekly.” In contrast, nearly two-thirds (63%) said that they pray or meditate “on special occasions” or “never.” Those who rarely practice one of these religious rites outnumbered those who regularly practice at least one by a large margin of 31 percentage points. Insofar as religious affiliation is concerned, religious people are more numerous than secular people. In contrast, when two popular religious practices are the measures of religiosity, secular people are more numerous than religious people.

To estimate the extent to which the Korean people live a religious life, we counted the number of pro-religious answers each respondent gave and constructed a three-point index. The low level indicates no pro-religious responses; the medium level, one; and the high level, two. As reported in Fig. 1, three-tenths (29%) of respondents lead highly religious lives; and one-third (32%) live somewhat religious lives. People whose lives include little or no religion constitute a plurality of two-fifths (40%). Those who are for the most part nonreligious outnumber the highly religious by a margin of 11 percentage points. This finding shows that Korea is a nation of neither the religious nor the nonreligious.

Table 1 shows the levels of religious life in major segments of the population. First, women are more likely to be highly religious than are men (39% vs. 19%). People who are mostly or totally nonreligious constitute the largest plurality of men. In contrast, the highly religious form the largest group of women. Second, age makes a difference. The age group with the highest proportion of highly religious members is the 40-to-59 age group, while the age group with the highest proportion of non- or barely religious members is the 20-to-39 group. Among young people, the most common level of religious life is low (45.1%); among middle-aged people, the high and low levels are roughly equal (34.4% and 36.1%, respectively); and among the oldest group, the most common level is somewhat religious. Third, married people are slightly more likely to be highly religious than unmarried people. Yet, the non- or barely religious constitute the largest plurality of both married and unmarried people. Fourth, there is little difference among the different education groups in terms of their members’ religiosity; however, each advancement in education level does bring a slight increase in the percentage of highly religious people and a slight decrease in the percentage of somewhat religious people. Fifth, there is little difference between income groups or between rural and urban residents. Overall, those who are middle-aged and/or female are the most likely to be highly religious, while those who are unmarried, young, and/or male are the least likely to be so.

3.4 Digital Life

Korea, like many other developed countries, is experiencing a revolution in information and communication technology (ICT). This advancement could have huge effects on all kinds of social interactions in every realm of human life. To what extent is exposure to digitalization impacting ordinary Koreans’ lives?

The 2006 ABS asked respondents how often they use Internet browsing, computer email, and mobile phone messaging. The Korean people as a whole use these digital media to a great extent. First, half (49%) say they use Internet browsing “almost everyday;” and one-seventh (14%), “several times a week.” Considering these responses together reveals that nearly two-thirds are regular users of Internet browsing. Second, three-tenths (29%) say they use computer emails “almost everyday;” and one-seventh (14%), “several times a week.” Considering these responses together reveals that more than two-fifths are regular users of computer emails. Third, more than half (52%) say they read or write messages by mobile phones “almost everyday;” and one-seventh (15%), “several times a week.” Considering these responses together reveals that two-thirds are regular users of mobile phone messaging. Daily life without digital media seems farfetched in Korea today.

To estimate the extent to which the Korean people live a digital life, we totaled the number of “almost everyday” or “several times a week” responses each respondent gave and constructed a three-point index. The low level indicates regular use of no digital media, and the high level indicates regular use of two or three. As shown in Fig. 1, nearly three-fifths (58%) regularly use two or three digital media; one-sixth (17%), only one; and one-quarter (25%), none.

Table 1 shows the levels of digital life in major segments of the population. First, there is no notable difference between men and women. Those living highly digitalized lives constitute the largest proportion of both gender groups. Second, there are huge age differences. More than four-fifths (83%) of young people live highly digitalized lives, compared to less than one-tenth (8%) of older people. Those living highly digitalized lives form a large majority (83%) of the youngest group, while those experiencing low levels of digital life form a large majority (80%) of the oldest. Middle-aged people, on the other hand, are more evenly split, with 44% experiencing a high level of digital life; 24%, a middle level; and 32%, a low level. Third, unmarried people are more likely to live highly digitalized lives than are married people, perhaps because the former tend to be younger than the latter. Even so, those living high levels of digital life constitute majorities of both unmarried and married people.

Fourth, there are huge differences between the two extreme educational groups. Nearly nine-tenths (88%) of those with a college education live highly digitalized lives, compared to less than one-tenth (8%) of those with no high school education. Those experiencing high levels of digital life constitute a large majority of the most educated, while those experiencing low levels of digital life constitute a large majority of the least educated. Fifth, the most affluent are more likely to live a digital life than are the least affluent. Three-quarters (74%) of high-income people live highly digitalized lives, compared to two-fifths (43%) of low-income people. Low-income people are divided fairly evenly into the two extreme categories of digital life: high, 43%, and low, 38%. In contrast, those experiencing high levels of digital life constitute majorities of both high-income and middle-income people. Lastly, urban residents are more likely to live a digital life than are rural residents. Only one-quarter (26%) of rural residents live highly digitalized lives as compared to a large majority (60% for large-city dwellers and 63% for other city dwellers) of urban residents. Overall, those who are young, better educated, more affluent, and/or urban residents are more likely to use digital media for information and communication than are those who are old, poorly educated, less affluent, and/or rural residents.

3.5 Global Life

Globalization involves movements of ideas, images, and people across national boundaries; hence a global life reflects high levels of exposure to or experience of global cultural flow (Berger 2002). To what extent are Koreans exposed to forces of globalization?

To measure the levels of global life, we selected three questions from the 2006 ABS. The first asked respondents to rate their ability to speak English, the most important asset for non-English speaking people to live a global life. The second asked respondents how often they travel internationally, and the third asked how often they watch foreign TV programs.

First, only less than one-fifth (17%) said they can speak English “fluently” or “well enough to get by in daily life.” More than four-fifths (83%) said that they speak it “very little” or “not at all.” An overwhelming majority of the Korean people apparently lack the key skill needed for living a global life. Second, only a few (6%) said that they traveled abroad at least three times in the past three years. An absolute majority of the Korean people have not traveled or rarely traveled internationally in the last three years. Third, about one-third (35%) said that they often watch foreign-produced TV programs. Hence, a large majority has had no or little exposure to foreign cultures or lifestyles through mass media.

To estimate the extent to which the Korean people live a global life, we totaled the number of positive responses each respondent gave and constructed a three-point index. The low level indicates no positive response, and the high level indicates two or three positive responses. As shown in Fig. 1, only one-tenth (11%) live highly globalized lives; one-third (35%) live somewhat globalized lives, and more than half (54%), live non- or barely globalized lives. Those who fall in the low category outnumber those who fall in the high by a large margin of 47 percentage points. This finding shows that the extent of globalization among the Korean people is extremely limited.

Table 1 shows the levels of global life in major segments of the population. First, there is no notable difference between men and women; those who experience low levels of globalization constitute majorities of both gender groups. Second, there is some age difference. About one-seventh (15%) of young people have high levels of global life, compared to only a few (3%) older people. Third, unmarried people are more likely to experience high levels of globalization than are married people, although the difference is not large. Fourth, there is a striking difference between the two extreme educational groups. Nearly one-quarter (23%) of those with a college education experience high levels of global life, compared to only a few (2%) of those with no high school education. Fifth, there is a notable difference between the rich and poor. About one-fifth (20%) of high-income people experience high levels of global life, compared to just under one-tenth (9%) of low-income people.

Lastly, urban residents are more likely to be highly globalized than are rural residents, although the difference is not large. These findings show that those who are young, better educated, and/or more affluent are more likely to speak English, travel abroad regularly, and frequently watch foreign TV programs than are those who are old, poorly educated, and/or less affluent. It is worth noting that the difference between the two extreme educational groups is greater than the difference between the two extreme income groups (21% vs. 12%). This finding suggests that education is more strongly linked to globalization.

On the whole, nearly every Korean lives a modern life by utilizing basic modern conveniences. A majority of the Korean people live a digital life through a variety of information and communication technology. Yet an overwhelming majority has yet to experience globalization, and despite cultural modernization, religion continues to play a key role in the lives of a substantial minority of Koreans.

4 Value Priorities

Value priorities refer to the resources and experiences that people consider important to living a good life. Thus, an examination of Koreans’ value priorities—which life circumstances they consider most important, how satisfied or dissatisfied they are with those life circumstances, and how value priorities and satisfaction levels vary across population segments—will reveal much about the quality of life in Korea.

4.1 Important Life Circumstances

The 2006 ABS asked respondents to choose five out of 25 life circumstances that are important to them. Those life circumstances were (1) having enough to eat, (2) having a comfortable home, (3) being healthy, (4) having access to good medical care, (5) being able to live without fear of crime, (6) having a job, (7) having access to higher education, (8) owning lots of nice things, (9) earning a high income, (10) spending time with family, (11) being on good terms with others, (12) being successful at work, (13) being famous, (14) enjoying a pastime, (15) appreciating art and culture, (16) dressing up, (17) winning over others, (18) expressing one’s personality or using one’s talents, (19) contributing to the local community or to society, (20) being devout, (21) raising children, (22) freedom of expression and association, (23) living in a country with a good government, (24) having a pleasant community in which to live, and (25) having a safe and clean environment. These life circumstances are associated with a variety of human needs, including basic survival, achievement, and self-actualization.

Table 2 shows which life circumstances the Korean people tend to value. An overwhelming majority (89%) chose good health as one of their top five priorities. Health remains the No.1 concern for the Korean people, despite lengthening lifespans. About half (47%) chose housing as one of their five. Although far behind health, housing is the second most common concern among Koreans, even though there have been great improvements in housing as of late. Perhaps Koreans are focused on housing because of a recent jump in housing prices, especially in urban areas. Economic affluence and spending time with family are the third and fourth most common concerns, respectively. About two-fifths (42%) chose each of these. The fifth and sixth concerns, raising children and having a job, were also a near tie, with both garnering mentions from three-tenths (31%) of respondents. It is notable that leisure is considered less important than employment. Only one-fifth (22%) chose enjoying a pastime as one of their top five priorities. The least prioritized values include freedom of expression and association, dressing up, winning over others, owning lots of nice things, and contributing to the local community or society. Only a few (3% or less) chose each of these as one of their top five priorities.

These findings indicate that the Korean people tend to prioritize values that are connected to physiological needs, safety needs, or the need for belonging, and they tend to downplay values tied either to the need for self-esteem or the need for self-actualization. Hence, materialism appears to be the dominant force of Korean culture; it is hardly a nation of post-materialists.

Table 3 shows how various population segments are alike and how they differ in the prioritization of their values. In every segment, good health is the most prioritized value, and in ten of the 16 segments, it is followed by housing. Gender clearly plays a role in the prioritization of values. Men, who are typically their families’ breadwinners, prioritize values associated with the need for having, while women, who are typically the homemakers, value those associated with the need for relating. Age seems to make less difference, as all of the age groups place health, housing, income, and family in their top four slots, though in different orders. Having a job rounds out the top five list of people aged 20 to 39, while people aged 40 to 59, the group likely to live with unmarried children, instead value raising children. Older people, who are likely to experience an “empty nest,” care more about having enough food, access to medical care, and employment, which create a three-way tie for their fifth slot. The oldest group is also the population segment most interested in health, with 97% of them including it in their top five priorities.

Married people care more about housing and family than do unmarried people, who place greater emphasis on income and employment. People with little education are far less likely to prioritize housing and more likely to care about health than are those with a high school or college education, but otherwise, the education groups are quite similar. As one might expect, low- and middle-income people are much more likely to prioritize income than are high-income people. All of the income groups emphasize family; however, the low- and middle-groups also emphasize child-raising, while the high-income group instead emphasizes having a job.

Lastly, there is a striking finding associated with community. While housing is the second most common concern among all city residents, it does not appear in the top five lists of rural residents at all. Rural residents are the only population segment not to include housing as a top five priority. Also noteworthy is that rural residents were much more likely to be concerned about health and having a job than were their city counterparts, while residents of large cities were far less likely to be concerned about family life than were residents of medium- and small-sized communities. These findings show that what Koreans value depends a great deal on the circumstance in which they live.

4.2 Needs for Having, Relating and Being

Allardt (1976) classified human needs or values into three types under the headings of having, loving or relating, and being (Campbell 1981). The need for having is associated with “those material conditions which are necessary for survival and for avoidance of misery.” The material conditions include economic resources, housing conditions, employment, health, and so forth. Second, the need for loving or relating is “the need to relate to other people and to form social identities.” Life circumstances associated with this need type include attachment to family and local community, friendships, interactions with associational members, and so forth. Lastly, the need for being is “the need for integration into society and to live in harmony with nature.” Life circumstances related to this need type include taking part in leisure activities, a meaningful work life, opportunities to enjoy nature, self-empowerment, and political participation.

To estimate the extent to which the Korean people are oriented either toward the need for having, the need for relating, or the need for being, we constructed three indexes. To measure the need for having, we totaled the number of value priorities each respondent selected from the following: (1) having enough to eat, (2) having a comfortable home, (3) being healthy, (4) having a job, and (5) earning a high income. To measure the need for relating, we totaled the number of value priorities each respondent selected from the following: (1) spending time with family, (2) raising children, (3) being on good terms with others, (4) contributing to the local community or to society, and (5) having a pleasant community in which to live. To measure the need for being, we totaled the number of value priorities each respondent selected from the following: (1) enjoying a pastime, (2) appreciating art and culture, (3) expressing one’s personality or using one’s talent, (4) freedom of expression and association, and (5) having a safe and clean environment. Because few respondents chose either four or five priorities from any one category, after making these totals, we converted each six-point index into a four-point index by collapsing the top three scores into one category.

To what extent do the Korean people prioritize the need for having, the need for relating, and the need for being? As shown in Fig. 2, two-fifths (42%) chose three or more value priorities associated with the need for having, while only a few (2%) chose none of them. Combining the top two categories shows that an overwhelmingly majority (82%) are oriented toward the need for having. In contrast, a very small percentage (6%) chose three or more value priorities associated with the need for relating, while a quarter (27%) chose none of them. Combining the top two categories reveals that only a minority (34%) are oriented toward the need for relating. Lastly, nearly no one (1%) chose three or more value priorities associated with the need for being, while half (50%) chose none of them. Combining the top two categories shows that only a tiny minority (10%) are oriented toward the need for being. These findings demonstrate that the need for having dominates Korean people’s values, while the need for being is hardly prioritized at all.

Table 4 shows how various population segments are alike and different in the types of values they prioritize. There are no notable demographic differences in the need for having; in all of the population subsets, those highly oriented toward the need for having constitute pluralities. In contrast, some differences concerning the need for relating do exist among various population segments. For instance, women, middle-aged people, and the married are more oriented toward the need for relating than are their counterparts. Nonetheless, those minimally oriented toward the need for relating constitute a plurality of every segment of the population. Lastly, some differences concerning the need for being exist among some segments of the population. For instance, young people, the unmarried, and those with a college education are more oriented toward the need of being than are their counterparts. Nonetheless, those with no need for being constitute either a majority or a plurality of every segment of the population.

On the whole, despite the fact that average Koreans are better fed, better housed, have a longer life expectancy, and are more affluent than ever before, their most cherished values are still tied up with meeting such basic needs as having enough to eat and having a comfortable home. Few strive for such non-material goals as achieving a sense of belonging and self-actualization. For the Korean people, survival and security remain of the utmost concern, while personal growth and harmony with nature are hardly concerns at all. It is notable that companionship and solidarity are valued less than are survival and security but more than are personal growth and harmony with nature. The majority of the Korean people are still pursuing materialist and acquisitive goals rather than post-materialist and self-expressive goals, and this prioritization of values is different from what is found in some Western post-industrial countries (Inglehart and Welzel 2005; Mitchell 1983). Evidently, Korea’s penchant for materialism goes deeper than the country’s economy.

5 Global Assessment of Life Quality

In this section, we examine the feelings Korean people have about the quality of their lives. We consider quality of life as a multidimensional phenomenon and focus on two dimensions, namely affective and cognitive. We accept the conventional understanding that feelings of happiness and enjoyment constitute the affective or hedonic dimension of life quality, while feelings of achievement and satisfaction, its cognitive dimension (Campbell 1981; Andrews 1986; Diener et al. 1999; Shin and Rutkowski 2003). Because the 2006 ABS has no question asking respondents about their overall satisfaction with life, we measure global quality of life as the extent to which feelings of happiness, enjoyment, and achievement are experienced.

5.1 Happiness

Feelings of happiness contribute to the affective dimension of life quality. Unlike feelings of satisfaction or achievement, however, feelings of happiness are distinguished by “the spontaneous feelings of pleasure” (Campbell 1981). They are likely to fluctuate even over a short period of time. In order to estimate the general levels of happiness among the Korean people, the 2006 ABS asked respondents a simple and straightforward question with five verbal response categories: “All things considered, would you say you are: (1) very happy, (2) quite happy, (3) neither happy nor unhappy, (4) not too happy, or (5) very unhappy?”

The Korean people tended to describe their lives as happy rather than unhappy. Of the five response categories, “quite happy” was the most frequent choice, selected by more than two-fifths (44%) of respondents. It was followed by “neither happy nor unhappy” (30%), “not too happy” (13%), “very happy” (12%) and “very unhappy” (1%). Combining the two positive responses reveals that more than half (56%) describe themselves as more or less happy (see Fig. 3). Those who live an unhappy life, on the other hand, constitute a small minority of only one-seventh (14%), which means happy respondents are four times as numerous as unhappy ones. While this undoubtedly speaks well of life quality in Korea, it is notable that people who are “neither happy nor unhappy” constitute a considerable minority. Even so, we must conclude feelings of happiness prevail over feelings of unhappiness in Korea today.

Which segments of the population are the most and least happy with their lives? Table 5 reports the percentages expressing happiness in major segments of the population. The percentages experiencing happiness vary significantly depending on life circumstances. First, women are more likely to report happiness than men, who belong to one of the few groups where a majority is not experiencing happiness. Second, increasing age is accompanied by steady declines in the proportion of those reporting happiness. Two-thirds of those in their 20s and 30s report happiness, as compared to one-third of those in their 60s. It is worth noting that two-thirds of older people are failing to experience happiness. Third, married people are not any happier than unmarried people; both are more likely than not to be happy. Fourth, of all the population groups, the one with the smallest proportion of happy people is the less-than-high-school-education group, while the group with the second-largest proportion of happy people was the college-educated group. Only one-third of the least educated people experience happiness, while two-thirds of the most educated people do. Fifth, higher income is related to greater happiness. The more money people make, the happier they are with their lives. The most affluent segment of the population is the happiest group of all, and the poorest segment is among the least happy groups. Lastly, the community in which people live has practically no influence on their level of happiness. According to these findings, the experience of happiness among the Korean people is related to their command of socioeconomic resources.

On the whole, old people, those with no high school education, and those with a low income are the least happy people in Korea, while young people, those with a college education, and those with a high-income are the most happy. Hence, in Korea today, a young, well-educated, and well-paid person would seem to have the greatest chance of happiness.

5.2 Enjoyment

Feelings of enjoyment constitute another affective dimension of life quality. They reflect positive experiences, which are related to general happiness with life. In order to estimate the general levels of enjoyment among the Korean people, the 2006 ABS asked: “How often do you feel you are really enjoying life these days: often, sometimes, rarely, or never?”

The Korean people tended to describe their lives as enjoyable rather than unenjoyable. Of the four response categories, “sometimes” was the most frequent choice, selected by more than half (52%) of respondents. This response was followed by “rarely” (28%), “often” (17%), and “never” (3%), in that order. Combining the two positive responses reveals that more than two-thirds (69%) of respondents reported experiencing some degree of enjoyment in their lives (See Fig. 3), which is even greater than the proportion that reported feelings of happiness. Those living an enjoyable life outnumbered those living an unenjoyable life by a sizable margin of 38 percentage points. This finding indicates that feelings of enjoyment are prevalent among the Korean people.

Which segments of the population experience the most and least enjoyment in their lives? Table 5 also presents the percentages expressing positive ratings of enjoyment in major segments of the population. The percentages experiencing enjoyment vary significantly depending on people’s life circumstances. First, women and men are both more likely than not to experience enjoyment, but women are even more likely to than are men. Second, increases in age are tied to decreases in enjoyment. Apparently, as people grow older, their life circumstances change to reduce their levels of enjoyment. Third, marital status makes no notable difference in enjoyment; those living an enjoyable life constitute majorities of both married and unmarried people. Fourth, education has a tremendous impact on enjoyment. Of all the population groups, the least educated had the smallest proportion of members experiencing enjoyment (48%), while the most educated all but tied with the 20 to 39 age group for the greatest proportion of members experiencing enjoyment (78%). Fifth, a higher income contributes to greater enjoyment. Of the income groups, the most and least affluent constitute, respectively, the groups most and least likely to experience enjoyment. Lastly, city dwellers are more likely to experience enjoyment than are rural residents.

In brief, the experience of enjoyment among the Korean people is related to their gender, their possession of socioeconomic resources, their life-cycle stage, and where they live. These findings show that old people, those with no high school education, those with a low-income, and those who live in rural areas are least likely to experience enjoyment. On the other hand, young people, those with a college education, those with a high-income, and those who live in urban areas are most likely to experience enjoyment. As in the case of happiness, it would seem that a young, well-educated, and well-paid person would have the greatest chance for an enjoyable life in Korea today.

5.3 Achievement

Feelings of achievement contribute to the cognitive dimension of life quality. Like feelings of satisfaction, feelings of achievement imply an act of judgment, a comparison of where people find themselves to where they want to find themselves. Hence, feelings of achievement tend to be more stable than feelings of happiness or enjoyment, which tend to fluctuate in response to fleeting moods (Campbell 1981). In order to estimate the general levels of achievement among the Korean people, the 2006 ABS asked: “To what extent do you feel you are achieving what you want out of your life: a great deal, some, very little, or none?”

The Korean people appear to be divided in their assessment of achievement in life. Only a few (4%) reported a great deal of achievement, and less than half (47%) some achievement. Similarly, less than half (45%) reported very little achievement, and a few (4%) no achievement (See Fig. 3). Those giving negative responses are as common as those giving positive responses. This finding shows that feelings of achievement are not dominant among the Korean people.

Which segments of the population feel the most and least accomplished? Table 5 presents the percentages reporting positive ratings of achievement in major segments of the population. The proportions experiencing achievement vary significantly depending on people’s life circumstances. First, there is practically no difference between men and women; both are about as likely as not to report feeling accomplished. Second, while young and middle-aged people are both about as likely as not to report feeling accomplished (54% and 50%, respectively), older people are considerably less likely to feel positive about their achievements (37%). Third, there is no notable difference between married and unmarried people. Fourth, education again makes a big difference. Of all the population groups, the one with the smallest proportion of members experiencing achievement is the least educated group (32%), while the most educated group had the second-largest proportion of such members (57%). Fifth, higher income is related to greater feelings of achievement. Of all the population segments, the most affluent group has the greatest proportion of members experiencing achievement (64%), while the accomplished proportion for the least affluent group is among the smallest. Lastly, urban residents are slightly more likely to report the experience of achievement than are rural residents.

In brief, as in the case of happiness and enjoyment, the experience of achievement among the Korean people is related to their possession of socioeconomic resources as well as their life-cycle stage. The findings show that old people, those with no high school education, and those with a low-income are the least likely to feel accomplished. In contrast, young people, those with a college education, and those with a high-income have the most fulfilling life. As in the case of happiness and enjoyment, a young, well-educated, and well-paid person would seem to have the greatest chance of feeling accomplished in Korea today.

The experiences of happiness, achievement, and enjoyment are connected in Korea; Koreans who describe their lives as happy also tend to report experiencing achievement and enjoyment. The correlation between happiness and enjoyment is very strong (r = 0.68), which one might expect considering both are measures of affective life quality. Not as strong but still significant are the correlations between achievement and happiness and between achievement and enjoyment, which are roughly equal (r = 0.47). These correlations show that the affective quality of life is closely related to its cognitive quality. Contrasting the three dimensions reveals that achievement is the weakest dimension of life quality in Korea, while enjoyment is the most robust. In Korea today, the cognitive quality of well-being falls short of its affective quality.

5.4 Overall Quality of Life

What proportion of the population is simultaneously experiencing feelings of happiness, enjoyment, and achievement? What proportion fails to experience any of them? Which segments of the population fully experience these feelings to a greater and lesser extent? By counting the number of positive feelings individual respondents gave, we constructed a four-point index to examine the patterns of overall life quality. The lowest score of 0 represents no positive ratings, and thus indicates the least desirable pattern of life, while the highest score of 3 represents all positive ratings, and thus indicates the most desirable pattern of life.

As shown in the last four columns of Table 5, about one-third (36%) appears to live the most desirable pattern of life by reporting the full experience of happiness, enjoyment, and achievement. In contrast, about one-quarter (23%) appears to live the least desirable pattern of life by reporting no experience of happiness, enjoyment, and achievement. Another one-quarter (25%) reported experiencing two of them, and one-seventh (15%), only one of them. These findings show that a majority of the Korean people are not thoroughly positive in their evaluations of their life quality. In the eyes of ordinary people, life in Korea has yet to achieve all-around desirability.

Which segments of the population tend to experience the most desirable and least desirable patterns of life? As shown in the same columns of Table 5, the proportions experiencing feelings of happiness, enjoyment, and achievement vary significantly depending on people’s life circumstances. First, there is little difference between men and women; for both groups, the proportion experiencing a fully desirable life is greater than any other proportion. Second, the older people are, the less likely they are to be thoroughly positive in their quality of life assessments. The proportion of such positive respondents steadily declines from 42% of those aged 20 to 39 through 34% of those aged 40 to 59 to 21% of those aged 60 to 69. It is worth noting that those experiencing none of the feelings constitute the largest group of older people. Third, there is little difference between married and unmarried people; the thoroughly positive constitute the largest groups of both married and unmarried people.

Fourth, the more educated people are, the more likely they are to be thoroughly positive. One-fifth (20%) of people with no high school education is so, as compared to more than two-fifths (43%) of college graduates. Those experiencing a fully desirable life constitute the largest group of the most educated. In contrast, those experiencing a fully undesirable life constitute the largest group of the least educated. Fifth, higher income is positively linked to greater life quality. The proportion of thoroughly positive respondents rises from 29% of low-income people through 40% of middle-income people to 48% of high-income people. Low-income people are about as likely to be thoroughly negative as thoroughly positive about their quality of life. Three-tenths (31%) report a fully undesirable life, and another three-tenths (29%) report a thoroughly desirable one. In contrast, the thoroughly positive by far form the largest group of high-income people. Lastly, there is not much difference between rural and urban residents. Yet those experiencing a fully desirable life constitute the largest group only of urban residents. Among rural residents, those experiencing none of the feelings are as numerous as those experiencing all the feelings.

On the whole, the most desirable pattern of life is most common among those who are young, highly educated and/or earn a high income. Those who are old, uneducated and/or earn low-incomes tend to live the least desirable pattern of life. These findings show that life circumstances associated with age, education, and income have the greatest influence on whether individuals will experience the most or least desirable patterns of life in Korea. All of the findings indicate that those who are young, well-educated, and well-paid have a good chance of living the most desirable pattern of life in Korea today.

6 Specific Assessments of Life Quality

In this section, we examine how the Korean people feel about a variety of specific life domains. Which aspects of life do Koreans find most and least satisfying? By comparing the levels of satisfaction and dissatisfaction across specific life domains, we try to identify the best and worst aspects of Korean life.

6.1 Life Domains

The 2006 ABS asked respondents how satisfied or dissatisfied they were with each of the following aspects of life: (1) housing, (2) friendships, (3) marriage, (4) standard of living, (5) household income, (6) health, (7) education, (8) job, (9) neighbors, (10) public safety, (11) the environmental condition, (12) the social welfare system, (13) the democratic system, (14) family life, (15) leisure, and (16) spiritual life. These life aspects by no means encompass all of the concerns of the Korean people, but they do provide a broad sample. Moreover, they include the ones that the Korean people consider important to their lives (see Table 2). They encompass both materialistic and non-materialistic aspects of life, as well as private and public spheres of life. To ascertain how satisfied the Korean people are with their life quality, the 2006 ABS used a five-point verbal scale, which runs from −2 (very dissatisfied) through 0 (neither satisfied nor dissatisfied) to 2 (very satisfied).

For each domain, Table 6 provides the complete distribution of respondents across the scale’s five points. It also provides a number of summary statistics including the mean ratings, and the PDI values, which measure the direction and magnitude of the difference between those who are satisfied and dissatisfied in each life domain.

A comparison of the mean ratings reveals that the social welfare system is the only domain falling below the midpoint (0) on the five-point scale. The mean ratings of the democratic system and household income are right at the midpoint. Those of the remaining life domains are above it. The domains with mean ratings that are considerably higher than the midpoint include friendship (0.8), marriage (0.7), and family life (0.6). Nonetheless, their mean ratings are still far lower than the highest score of 2. This finding indicates that at the level of specific life domains, the quality of life in Korea has much room for improvement.

As the PDI values indicate, in every life domain except one, the satisfied are more common than the dissatisfied. The only exception is the social welfare system. The preponderance of satisfaction over dissatisfaction varies a great deal across life domains. Friendship (+64) has the highest PDI value in favor of satisfaction. It is followed by marriage (+56), family life (+56), and neighbors (+51). In contrast, the social welfare system (−18) has the lowest value. It is followed by household income (+3), the democratic system (+4), and leisure (+8). The Korean people as a whole tend to be more satisfied with interpersonal domains than with any other aspect of life. Moreover, they tend to be least satisfied with public conditions of life.

Table 7 shows which life domains different segments of the population find most and least satisfying. First, men are most satisfied with marriage, while women are with friendship. Men and women alike are most dissatisfied with the social welfare system. Second, young and middle-aged people are most satisfied with friendship and most dissatisfied with the social welfare system. In contrast, older people are most satisfied with neighbors and most dissatisfied with income. Third, married and unmarried people alike are most satisfied with friendship and most dissatisfied with the social welfare system. Fourth, people with no high school education are most satisfied with neighbors and most dissatisfied with education. In contrast, people with a high school education are most satisfied with friendship, while people with a college education, marriage. Yet both of them are most dissatisfied with the social welfare system. Fifth, low- and middle-income people are most satisfied with friendship, while high-income people, marriage. Yet, among all income groups the social welfare system is the most dissatisfying domain.

Lastly, rural residents are most satisfied with neighbors and most dissatisfied with income. In contrast, city dwellers are most satisfied with friendship and most dissatisfied with the social welfare system. It is worth noting that the social welfare system is the most dissatisfying domain in thirteen of the eighteen population segments considered. On the other hand, friendship is the most satisfying domain in ten of the eighteen population segments. In the eyes of the Korean people, the country’s meager social welfare system constitutes the area of life most in need of improvement.

How many life domains do the Korean people find satisfying and dissatisfying? To address these questions, we counted the number of domains each respondent rated positively and negatively. As presented in the fourth and fifth columns of Table 7, the Korean people are, on average, satisfied with 6.6 of 16 domains and dissatisfied with 2.6 domains.

The number of domains satisfied and dissatisfied varies considerably across the various population segments. First, men and women do not differ in how many domains they find either satisfying or dissatisfying. Second, young people and old people do not differ in how many domains they find satisfying, but the former tend to experience dissatisfaction in fewer domains than the latter (2.4 vs. 3.4). Third, married people and unmarried people do not differ in the number of domains they find either satisfying or dissatisfying. Fourth, the most educated tend to experience satisfaction in more domains (7.4 vs. 5.8) and dissatisfaction in fewer domains (2.0 vs. 3.8) than do the least-educated. Fifth, high-income people tend to experience satisfaction in far more domains (8.6 vs. 5.6) and dissatisfaction in far fewer domains (1.5 vs. 3.4) than do low-income people. Lastly, rural residents and urban residents do not differ in the number of domains they find either satisfying or dissatisfying. These findings demonstrate that socioeconomic resources matter for the quality of life Koreans experience at the level of specific life domains.

The last two columns of Table 7 display the percentages of those who have more satisfying than dissatisfying domains and of those who have more dissatisfying than satisfying domains. A large majority (72%) of the Korean people have more satisfying than dissatisfying domains. In contrast, only one-quarter (25%) have more dissatisfying than satisfying domains.

The percentages of those having more satisfying than dissatisfying domains vary across the different population segments. There is little difference either between men and women, married and unmarried, or rural residents and urban residents. In contrast, while four-fifths (79%) of people with a college education have more satisfying than dissatisfying domains, just three-fifths (61%) of people with no high school education do. Similarly, nearly nine-tenths (86%) of high-income people have more satisfying than dissatisfying domains, while just six-tenths (62%) of low-income people do.

Likewise, the percentages of those having more dissatisfying than satisfying domains vary across the different population segments. There is not much difference between men and women, married and unmarried people, or rural and urban residents. In contrast, while one-third (37%) of people with no high school education has more dissatisfying than satisfying domains, only a sixth (17%) of people with a college education does. Similarly, one-third (34%) of low-income people has more dissatisfying than satisfying domains, while only one-eighth (12%) of high-income people does. This finding again illustrates the importance of socioeconomic resources for the quality of Korean life at the level of specific life domains.

6.2 Life Spheres

The domains of life do not exist independently of each other. Some domains are more closely related to each other than are others. To explore how the Korean people distinguish life spheres, we performed factor analysis on the entire set of 16 life domains and estimated the proximity of their relations. Table 8 shows that the 16 domains are grouped into three clusters. A large cluster of eight domains including income, standard of living, education, job, health, leisure, housing, and spiritual life displays primary loading on the first factor, meaning they are most related to the personal sphere of life. Domains in this sphere are associated with what an individual person holds and does, and they include both material and non-material aspects of life.

A smaller cluster of four domains, including the social welfare system, the democratic system, public safety, and the environment, displays primary loading on the second factor, meaning they are most related to the public sphere of life. Domains in this sphere are primarily associated with conditions of community or national life.

The final cluster of four domains including neighbors, friendships, marriage, and family life displays primary loading on the third factor, meaning they are most associated with the interpersonal life sphere. Domains in this sphere involve a variety of intimate human contacts. It is notable that spiritual life has substantial loading on the third factor, while marriage and family life have substantial loading on the first factor. These findings suggest that marriage and family life are also associated with the personal sphere, while spiritual life, the interpersonal sphere. In brief, the Korean people tend to distinguish their various life aspects into three broad spheres: personal, interpersonal, and public.

In which life spheres do the Korean people fare better? All the domains associated with the interpersonal sphere are rated positively, and their PDI values are all above +50% (see Table 6). In contrast, there is no notable pattern of satisfaction or dissatisfaction in the personal and the public spheres. All of the domains associated with the personal sphere are rated positively, but their PDI values vary greatly from a low of +3 to a high of +42. In the personal sphere, material life domains tend to be less satisfying than nonmaterial life domains. In the public sphere, two domains are rated positively, while one, negatively. Their PDI values vary greatly from a low of −18 to +21. Overall, of the three life spheres, the Korean people find themselves most satisfied in the interpersonal sphere and least satisfied in the public sphere.

7 Determinants of Global Quality of Life

7.1 Bivariate Analysis

Satisfaction or dissatisfaction with specific life domains is likely to influence global quality of life. Because some life domains are more central than others, however, assessments of specific life domains are expected to have varying levels of influence on global quality of life. In this section, we compare the extent to which each of the 16 domains surveyed is linked to global assessment of life quality. Which life domains are most and least related to feelings of happiness, enjoyment, and achievement, as well as their composite index of overall quality of life?Footnote 3

Table 9 presents simple correlation coefficients. Comparing the magnitude of coefficients across the domains, we identify those life domains which contribute most to global quality of life. In the case of happiness, standard of living has the strongest relationship. It is followed by marriage, household income, family life, and spiritual life, in that order. This pattern of relationships is also found in the case of enjoyment. The pattern is somewhat different in the case of achievement. Standard of living again has the strongest relationship, but it is followed by household income, marriage, job, housing, and family life, in that order. One of the notable findings is that standard of living is consistently the domain most strongly related to both the affective and cognitive quality of life. It is also notable that spiritual life is more strongly related to the affective quality, while job and housing are more strongly related to the cognitive quality.

When the three feelings of life quality are considered together, standard of living stands out as the most powerful influence on the overall quality of life. Other notable influences include marriage, household income, family life, and spiritual life. These findings show that the overall quality of life in Korea depends far more on the gratification of the need for having and the need for relating than on the need for being. It also shows that the personal and interpersonal spheres of life contribute most to the overall quality of Korean life, while the public sphere contributes the least. The closer and more immediate the life domains are to a person’s daily life, the larger their contributions are to his or her experience of life quality. The farther and more remote the life domains are to a person’s daily life, the smaller their contributions are to his or her experience of life quality (Park and Shin 2005).

7.2 Multivariate Analysis

In this section we use three clusters of control variables—demographics, lifestyles, and value priorities—to examine the effects satisfaction levels with life domains have on global quality of life. We perform OLS on these variables and estimate the independent effects of individual life domains and their clusters on the three measures of global life quality—happiness, enjoyment, and achievement—as well as their composite index.

Table 10 presents the results of analysis for an entire sample, and Table 11 for a subsample of the married.Footnote 4 Both tables report two statistics—beta and R 2—resulting from the multiple regression analyses. Comparing the magnitude of beta or standardized regression coefficients across the four clusters of independent variables, we identify those clusters or variables that independently contribute to global life quality.

We begin with the entire sample. First, we look at satisfaction with life domains. In the case of happiness, satisfaction levels with some life domains have significant effects. Housing has the most powerful positive influence. Next to this domain are spiritual life, standard of living, public safety, family life, and health, in that order. It seems odd that environment has strong, but negative effects, after other variables are controlled. Second, we look at demographic variables. Being female instead of male or married instead of unmarried contributes to happiness. As people get older, they are less likely to be happy. Socioeconomic resources such as education and income have no effects after other variables are controlled. The type of residential community has no effects. Third, we look at lifestyles. Living a digital life contributes to happiness. Yet other lifestyle factors, such as being modern, religious or globalized, make no contribution to happiness. Lastly, we look at value priorities. None of the value priorities has significant effects. This entire set of four clusters of variables accounts for one-third (35%) of the variance in happiness.

For enjoyment, we again begin with satisfaction with life domains and again find some significant effects. Standard of living has the most powerful influence. It is followed by spiritual life, public safety, and health, in that order. Again, environment has significant but negative effects after other variables are held constant. Second, we look at demographic variables and find being female instead of male contributes to enjoyment. As people get older, they are less likely to have an enjoyable life. Socioeconomic resources such as education and income have no independent effects after other variables are controlled. Where people live makes no contribution to enjoyment. Third we look at lifestyles. Only two lifestyle types, digital and religious, contribute to enjoyment. Lastly, we look at value priorities and find no significant effects. This entire set of four clusters of variables accounts for one-third (34%) of the variance in enjoyment.

For achievement, we once again begin with satisfaction levels for life domains and find a few significant effects. Standard of living has the most powerful influence. It is followed by housing and having a job. None of the remaining domains has significant effects. This finding suggests that only the material life domains contribute to achievement. Noteworthy is that none of the five demographic variables, four lifestyles, or three value priorities makes any contribution to enjoyment. This entire set of four clusters of variables accounts for three-tenths (30%) of the variance in achievement.

The last column of Table 10 shows the effects of the independent variables on the composite index of overall life quality. First, of the 16 life domains considered, standard of living has the most powerful effect. It is followed by spiritual life, housing, public safety, leisure, and family life, in that order. Again, environment has significant but negative effects. Second, only two demographic variables have significant effects. Being married instead of unmarried contributes to a better overall life quality. Age has negative effects, indicating that young people are more likely to experience greater well-being than are older people. Yet socioeconomic resources have no significant effects when other variables are held constant. Third, two lifestyles, being religious and digitally connected, contribute to the overall life quality. None of the value priorities have significant effects. This entire set of four clusters of variables accounts for more than two-fifths (43%) of the variance in the overall quality of life.

As the analysis displays, among the Korean people as a whole, standard of living is consistently a powerful predictor of global quality of life. One of the notable findings is that the importance of life domains varies across the different dimensions of life quality. For instance, spiritual life, health, and public safety matter for the affective quality of life but not the cognitive quality. In contrast, having a job matters for the cognitive quality of life and not the affective quality. Yet standard of living and housing matter for the affective as well as the cognitive quality. Another notable finding is that environment has negative effects on the affective quality but not the cognitive quality. Also striking is that the level of education or income Koreans have has no independent influence on any dimension of their life quality. Gender, age, and marital status have an influence on the affective quality but not the cognitive quality. Two lifestyle types, being digitally connected and being religious, contribute to the affective quality.

Now we turn to the results of our analysis for the married sub-sample, as presented in Table 11. First, we look at satisfaction with life domains. In the case of happiness, satisfaction levels for some life domains have significant effects. Marriage has the most powerful influence. Next to this domain are standard of living, housing, public safety, family life, and spiritual life, in that order. It is intriguing that environment and education have significant but negative effects after other variables are controlled. Second, we look at demographic variables and find being female rather than male contributes to happiness. As people grow older, they are less likely to experience happiness. Socioeconomic resources such as education and income have no significant effects after other variables are controlled. Where people live makes no contribution to happiness. Third, we look at lifestyles. A digital life contributes to happiness while other lifestyle characteristics—being modern, religious, or globalized—do not. Lastly, we look at value priorities and find no significant effects. This entire set of four clusters of variables accounts for one-third (37%) of the variance in happiness.

For enjoyment, we again begin with satisfaction levels for life domains and again find some significant effects. Marriage has the most powerful influence. It is closely followed by standard of living. Next to these domains are the social welfare system and public safety. Again, the environment has significant but negative effects. Second, we look at demographic variables and find being female instead of male contributes to enjoyment. In contrast, neither educational attainment nor income levels have significant effects. Neither do age nor residential community Third, we look at lifestyle types. Only digitalization makes a contribution to enjoyment. Lastly, we examine value priorities and again find no significant effects. This entire set of four clusters of variables accounts for two-fifths (39%) of the variance in enjoyment.

For achievement, we again begin with satisfaction levels for life domains and find only a few have significant effects. Standard of living has the most powerful influence. It is followed by marriage, housing, and job, in that order. It seems odd that health has significant but negative effects on achievement. This finding suggests that satisfaction in material life domains contributes to achievement. It is noteworthy that none of the demographic variables, lifestyles, and value priorities has significant effects. This entire set of four clusters of variables accounts for one-third (33%) of the variance in achievement.