Abstract

Social quality has been presented as a theory that can explain economic and social progress of the daily lives of a population. The components of social quality include: socio-economic security, social inclusion, social cohesion and social empowerment. The social quality perspective views people as interacting within collective identities that provide the contexts of self-realisation. The paper tests the social quality theory by focusing on the relationship between social inclusion and social cohesion, the notion of social relations, to socio-economic security using the context of the family as a facilitator of self-realisation. Using data from the Israel Social Survey 2003, six indicators of socio-economic security were analysed. There was a small but positive and significant relationship between social inclusion and socio-economic security. We found no relationship between socio-economic security and social cohesion. These findings tend to undermine those aspects of social quality theory which posit close connections between these elements on a conceptual level.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Social quality is a standard intended to assess both economic and social progress that measures the quality of the daily lives of a population (Beck et al. 2001). Social quality was defined as ‘the extent to which citizens are able to participate in the social and economic life of their communities under conditions which enhance their well-being and individual potential’ (Beck et al. 1997a). The advancement of the social quality theory is a result of concerns as expressed in the European social policy debate. In 1992 the European Commission launched an initiative for a convergence strategy regarding the diversity of social protection systems in the Member States. In 1997 the Commission referred to the emerging consensus that social protection systems, far from being an economic burden, can act as a productive factor that contributes to economic and political stability. It also helps European economies to be more efficient and flexible and, ultimately, to perform better. It was recognised that economic growth on its own cannot solve the unemployment problem (Flynn 1997). In June 1997 the Amsterdam Declaration on the Social Quality of Europe (Amsterdam Declaration on the Social Quality 1997) was published. The Declaration states that the people of Europe cannot “countenance a Europe with large numbers of unemployed, growing numbers of poor people and those who have only limited access to health care and social services”. Rather, the social quality of Europeans should be a paramount policy goal. This is according to the Declaration where citizens have “access to an acceptable level of economic security and of social inclusion, live in cohesive communities and be empowered to develop their full potential.”

The influence of social quality in both academic and policy circles has grown rapidly. This declaration was signed initially by 74 academics from the fields of social policy, sociology, political science, law and economics. By November 1999 the declaration had been signed by 800 European social science academics, and the European Union has actively embraced the concept and has incorporated it into its social reporting. The European Commission’s Directorate General for Employment and Social Affairs chose social quality as one of three priority areas for action in the year 2000. In addition, the primary European Union annual social statistical report, The Social Situation of the European Union 2001, was themed around social quality. Moreover details of the indicators and measurement of social quality, have been calculated for 14 European Member States (van der Maesen et al. 2005).

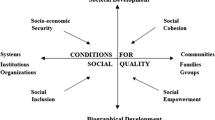

Social quality is presented as a theory intended, through the application of ‘social quality indicators’, to assess both economic and social progress that measures the quality of the daily lives of a population (van der Maesen and Walker 2005). Phillips (2006) states that social quality is to be judged “as a comprehensive, consistent and rational theoretical structure; a construct that encapsulates and explains societal quality of life or, more precisely social quality” (p. 176). The term social quality provides a wider and multidimensional approach to the quality of life than does poverty or social exclusion that have been the main quality-of-life measures used by the European Union and European governments. The social quality perspective views people as ‘social beings’. People as social beings interact with each other. These interactions constitute the collective identities that provide the contexts of self-realisation (van der Maesen and Keizer 2002). Van der Maesen (2002) points out that people interact with each other for their self-realisation in the context of the formation of collective identities such as families, communities and other groups. Social quality is intended to be comprehensive and to encompass both objective and subjective interpretations. The components of social quality as objective factors are: that people need to have access to socio-economic security, they must experience inclusion in political, economic and social systems, that they should be able to live in communities characterised by a sufficient level of cohesion and that they must be empowered to be able to take advantage of opportunities. This paper will test the social quality theory by focusing on the relationship between social inclusion and social cohesion to socio-economic security using the context of the family as a facilitator of self-realisation.

We begin with a description of the four components of social quality. Socio-economic security is then analysed within the context of the other three social quality components: social inclusion, social cohesion and social empowerment in order to clarify the relationship between the components. These three components of social quality have the notion of social relations. It is central to social inclusion which is about access to and integration into institutions and social relations. Social cohesion is societal solidarity or, more prosaically, as having to do with social relations, norms, values and identities and is central to social life because the notions of communities and the social world itself are impossible without social cohesion. Social empowerment is about the enhancement of ability and capabilities by social relations (Phillips 2007). These three components can be seen as independent variables to the social quality component socio-economic security which can be seen as material resources that transcend the purely social.

Next we will describe how people interact with each other for their self-realisation in the context of the formation of collective identities using the nation and community as examples. The description of methodology used will be followed by the statistical results and an analysis of the relationship between socio-economic security and the components social inclusion and social cohesion using the collective identity family as the independent variable.

1.1 The Components of Social Quality

The four components of social quality each of which are conceptualised as a continuum are: social-economic security, social inclusion, social cohesion and social empowerment (Beck et al. 1997a). We will now define and describe these four components. The following definitions are based on the work of the European Thematic Network on Indicators of Social Quality (ENIQ).Footnote 1

Social-economic security is the extent to which people have sufficient resources (material and immaterial) over time in the context of social relations. It refers to the way the essential needs of citizens with respect to their daily existence are addressed by the different systems and structures responsible for welfare provisions. An acceptable minimum of social-economic security provides protection against poverty, unemployment, ill-health and other forms of material deprivation. Macro level domains for this component include: financial resources, housing and environment, health and care, work and education (Keizer 2004). Specimen indicators, at the macro level, for each of the domains for each element of social quality have been provided in the earlier work of Berman and Phillips (2000) and, in more detail, in Phillips and Berman (2000).

Social inclusion is the extent to which people have access to institutions and social relations. It is associated with the principles of equality and equity and the structural causes of their existence. The goal is a basic level of inclusion with help of supportive infrastructures, labour conditions and collective goods in such a way that those mechanisms causing exclusion will be prevented or minimised. This component focuses attention on the structural causes of exclusion. The focal point of inclusion is the access to institutions and social relations. The domains identified for social inclusion includes: citizenship rights, labour market, services (public and private) and social networks (Walker and Wigfield 2004).

Social cohesion is defined as the nature of social relations based on shared identities, values and norms. The component is concerned with the processes that create, defend or demolish social networks and the social infrastructures underpinning these networks. An adequate level of social cohesion is one that enables citizens to exist as social beings (Beck et al. 1997a). On the other hand, anomie is fostered by regional disparities, the suppression of minorities, unequal access to public goods and services and an unequal sharing of economic burdens. Social cohesion is related to both social capital (World Bank 1998) and social integration (Klitgaarde and Fedderke 1995). Its domains include: trust, integrative norms and values, social networks and identity (Berman and Phillips 2004).

Social empowerment refers to the extent to which the personal capabilities of people, and their ability to act are enhanced by social relations (networks and institutions). It is the realisation of human competencies and capabilities, in order, to fully participate in social, economic, political and cultural processes. It primarily concerns enabling people, as citizens, to develop their full potential. Social empowerment is a concept with both active and passive connotations, with active predominating in the sense of self-empowerment, or taking control. Its passive connotation lies in being empowered, thus enabling or facilitating empowerment to take place. Domains of social empowerment include: knowledge base, labour market, openness and supportiveness of institutions, public space and personal relationships (Hermann 2004).

These components are not intended to be mutually exclusive—they often interact with and complement each other—but taken together as the components of social quality they are intended to provide a comprehensive model of the social and economic determinants of citizen well-being.

1.2 Socio-economic Security and the Other Social Quality Components

In this section we will clarify the relationship between socio-economic security and two components of social quality, social inclusion and social cohesion. We have not included the component social empowerment in our study as there were no appropriate indicators in our data set. But first we need to take a closer look at the component socio-economic security. The ‘socio’ of socio-economic security refers to the social quality concept of ‘the social’, meaning the reciprocal relationship between processes of self-realisation of people and processes leading to the formation of collective identities. ‘Economic’ refers to the Greece word ‘oikos’ or household, meaning to co-operate together in order to cope with daily circumstances. In the social quality approach it refers to looking after oneself, family and relatives, with help of, for example, community groups, the municipality and national institutions (Keizer 2004).

1.2.1 Socio-economic Security and Social Inclusion

The component socio-economic security is about having resources, while inclusion is about the integration in or the access to society and institutions that are ‘actors’ in the field of action for resources. Socio-economic security is the status of having or not having sufficient resources while inclusion is more about the process of gaining resources. Social inclusion is the integration of the social being in systems in our context the family.

1.2.2 Socio-economic Security and Social Cohesion

The relationship between social cohesion and the component of socio-economic security can be hypothesised as follows. High levels of social cohesion resources like trust, social networks, altruism and identity will facilitate and enable the enhancement of socio-economic security by providing the right environment in which they may flourish—classically. One can surmise that it is not easy to maintain socio-economic security in a society where people do not trust each other and have limited and inward-looking associational networks. An aspect of this relationship is the quality of societal norms and values with regard to social relations, especially family and community, as resources for socio-economic security. Family or social networks could be seen as an immaterial resource for facilitating socio-economic security. If ones own resources are not sufficient one can hopefully count on family and friends. In this way social networks are a resource for the mutualising of risks. The inclusion in social networks and the quality of these networks can be seen as a condition for social socio-economic security and social cohesion.

1.2.3 Collective Identities as a Source of Socio-economic Security

Collective identities are the key context in the facilitation of self-realisation in the social quality theory. There are three collective identities, commensurate with the macro, meso and micro classification to be sources of socio-economic security. They are: institutions (political), community/neighbourhood and family. The optimisation of socio-economic security within any one of the collective identities varies according to societal factors.

Social quality has to do with citizens participating in social and economic life through their collective identities. In his discussion of membership of communities Delanty (1998) distinguishes between the ‘Demos’ and the ‘Ethnos’. ‘Demos’ is on a macro-level, including nation-state or society. Membership of the political community is generally defined in relation to the state. The nation-state defines the accessibility to services within the framework of citizenship. Shared objectives create a very particular integrated state.

Baubock (1995) indicates the limitation of the universalism of citizenship as it pertains to a multicultural society. In Western Europe, immigration and the transformation of nations into multiethnic societies challenged the traditions of nations and citizenship (Hefner 1998). The Demos within a society has become unclear. Demos is not universal and social exclusion on the national level has become a social fact.

As well as their association with Demos, individuals can also be part of a cultural community or ‘Ethnos’. The distinctiveness of the ‘Ethnos’ has been emphasised by the postmodern movement. Katsikides (1998) notes that in the late 20th century, postmodernity characterised the features of diversity rather than sameness. Postmodern thought may be characterised as involving plurality, decentralisation, a concern for local and communal relations, collectivity, pragmatism and multiple ways of knowing (Hlynka and Yeaman 1992; McGowan 1991; Smart 1990). Ethnic, religious, regional or linguistic groups for example become the major focus of attention. The universalist and centralist themes of modern society are replaced by an interest in diversity, with a decentralised plurality of democratic, self-managing groups and institutions and social movements (Giddens 1990; Taylor-Gooby 1994).

The relationship between demos and ethnos depends on national policy. In some countries the state encourages communities themselves to provide services that are normally provided by government agencies. In relation to ethnos communities this ranges from, for example the provision of religious denominational schools in the United Kingdom through to virtual self-government of the Walloon and Fleming communities in Belgium. For locality-based communities the obvious example is devolved local government. Such policies ensure that a major aspect of the social quality of community members accrues to them by virtue of their status as community members.

In southern European countries—Greece, Italy, Portugal and Spain, the extended family plays an important role in determining a person’s sense of belonging, and source of socio-economic security. In the Scandinavian countries state institutions play a dominant role in this area (Warman 1998). The community can be seen as a main source of socio-economic security for immigrant populations where altruism and reciprocity exists and there is a high level of trust and community identity (Phillips and Berman 2003). The implications of analysing socio-economic in the context of collective identities are that the articulation of socio-economic security within collective identities and its impact on social quality varies within society over time. Terms such as integration, assimilation and segregation are related to the self-realisation of the individual within the collective identities for socio-economic security on a demos-ethnos level.

In Israel, collective identity dilemmas intersect with issue voting, where religious observance proved a more important socio demographic factor in voter behaviour than ethnicity and income (Shamir and Arian 1999). This relationship between the demos and the ethnos is reflected in the services structure in Israel that, especially with regard to personal and familial issues, reflects religious components much more than the ethnic component. For example marriage and divorce is regulated by religious law, including for those who profess to not adhere to religious decrees. Similarly schooling is state organised and state funded in concordance with the characteristics of many different religious groups, and restricted to students of that group only. Conversely, virtually all state funded services are provided to all, and not restricted by ethnicity. When compared to other European States, altruism is a value that is regarded highly, as is the expectation that the state should intervene to reduce social inequality. To what extent these attitudes translate into behaviour is not clear at this time.

1.3 Social Quality and Collective Identities

There have been a number of studies relating to the various collective identities as the key context in the facilitation of self-realisation in the social quality theory. Berman and Phillips (2000) explored the domains and indicators of social inclusion and exclusion and their interaction at national and community level, within the context of the social quality construct and the notions of Demos and Ethnos. In addition there are a series of papers that developed the concept of social quality on the community level. In a concept paper, Phillips (2001) argued for the concept of community citizenship and showed how this is related to community social quality. Phillips and Berman (2001) operationalised the concept of community social quality level by developing indicators of community. Phillips and Berman (2003) also explored ways in which ethnos communities could enhance their social quality through working with national institutions.

There has been extensive work on indicator development for social quality by the European Foundation on Social Quality. In October 2001 the EFSQ started the European Thematic Network on Indicators of Social Quality (ENIQ). This Network project was funded by the Fifth Framework Programme of DG Research of the EC running from 2001 to 2004. The results of this project were the development of indicators for the four components of social quality on the national level.Footnote 2

It is important to point out that the work done in the area of social quality indicators has been in the area of the conceptualisation of the theory, indicator development and the collection of data. The goal of our paper is to test empirically the social quality theory. We do this by analysing the link between social inclusion and social cohesion to socio-economic security within the framework of collective identities using the family. Basing our analysis on the theoretical foundation of the social quality we chose for the components social inclusion and social cohesion independent variables that are linked to the family as sources of socio-economic security. As noted, social networks in general and family in our context could be seen as an immaterial resource for facilitating socio-economic security. If ones own resources are not sufficient one can hopefully count on family and friends. In this way social networks are a resource for the mitigation of risks. Thus, the inclusion in social networks and the quality of these networks can be seen as a condition for social socio-economic security. Our hypothesis is that the optimisation of socio-economic security will vary according to family social quality factors.

2 Method

The questions that were used to examine the social quality theory were part of the Israel Social Survey 2003. This annual cross sectional survey (N = 7,212) is conducted by the Israel National Bureau of Statistics and weighted to represent the Israel adult population (age 20–75+). The method of data collection is by personal household interviews. The respondents were a stratified pre-selected sample from the population registry (Kamen 2002). The dependent variable, social-economic security was the composite of following variables: (a) income security which consisted of a six-item scale that assessed the respondents satisfaction with his or hers current economic situation with items such as “Are you satisfied with your ability to meet all monthly household expenses?”. Respondents were asked to rate their satisfaction with each item, using a 5-point scale ranging from (1) very satisfied to (5) not satisfied at all. (b) Housing conditions referred to the satisfaction with physical and environmental aspects of the dwelling and was assessed on a seven-item scale with items such as “are you satisfied with the warmth of the apartment during the winter”? Respondents were asked to rate their satisfaction with each item, using a five-point scale ranging from (1) very satisfied to (5) not satisfied at all. (c) Housing payments was a three-item, 4-point scale that dealt with the ability of the respondent to meet housing related expenses such as mortgage and heating. (d) Health was assessed on a seven-item scale that referred to the degree by which health deficiencies negatively impacted on daily life, and the ability to pay for medical treatment. Respondents were asked to rate their agreement with each item, using a 5-point scale ranging from (1) strongly agree to (5) strongly disagree. (e) Work conditions depict the satisfaction of the respondent with his or hers workload and the physical conditions of the workplace such as exposure to noise or dust. Respondents were asked to rate their satisfaction with ten items, using a 5-point scale ranging from (1) very satisfied to (5) not satisfied at all. (f) Access to paid employment is the second, three-item, 4-point, work related scale. It assesses the extent by which respondents were employed in the past e.g. “what was your main activity over the last 12 months”. The first independent variable was social inclusion as depicted by familial and friends’ relationships. This six-item scale included items on the satisfaction of the respondent with the nature and frequency of contact with family and friends “are you satisfied with the frequency you talk with family members who do not live with you?” Respondents were asked to rate their satisfaction with each item, using a 4-point scale ranging from (1) very satisfied to (4) not satisfied at all.

Berman and Phillips (2004) use altruism as an indicator to operationalise social cohesion. Lockwood (1999) refers to altruism and ‘other-regarding’ behaviour as central to the development of social capital towards being positively useful as a ‘social glue’ enabling society to operate effectively. We consider altruism an important indicator of integrative social norms and are central to normative integration. The act of altruism in its truest sense, of giving to strangers with no consideration of reciprocity, was identified in Titmuss’ (1971) classic study of blood donors, as an indicator of ‘the good society’. We will use altruism as our indicator of social cohesion, the second independent variable. We use altruism within the family setting, i.e. a three-item scale assessing whether or not respondents helped dependent parents financially, with personal care, and in daily activities such as shopping, cleaning and cooking. We acknowledge that our use of altruism within a family context is a very narrow conceptualisation of altruism as it is kindness to kin rather than to friends, neighbours or strangers.

To create the composite variables with a minimum loss of information we utilised principal components analysis, which creates linear composites of the original items. To ascertain the communality of the new variables only the first factor was included in the study (see Table 1).

3 Results

The first step in the examination of the relationship between social inclusion and social cohesion, and the (dependent) variables was the calculation of Pearson’s coefficients (see Table 2).

The correlations between social inclusion and the dependent variables were significant. Less so were the correlations between social cohesion and the dependent variables. This was the first indication that social inclusion was the more significant component. We then performed canonical analysis to ascertain the linear combinations between these two sets of variables, in order to maximise the Pearson’s coefficient of correlation. This resulted in the relatively weak canonical correlation Pearson coefficient of 0.35, which is in line with our previous findings. The next step was performed to combine the six component independent variables into a single one: social economic status (SES).Footnote 3 Principal component analysis of these six variables resulted in the first factor, with the first eigenvalue of 2.43 that explains 40.5% of the variance. The regressions equation (without intercept) is as follows:

The two regression coefficients are significant and account for about 10% (R 2 = 0.1088) of the variance F(2,7210) = 440.32, P < 0.0001. Given the large number of observations, and although weak, this result is acceptable. Consistent with our earlier findings regarding the relative strength of association between SES and the independent variables, the Pearson’s correlation coefficient between SES and social inclusion was a relatively strong r = −0.31, and between SES and social cohesion a relatively weak r = 0.05. To assess the differences between the relationship between the dependent and independent variables, we utilised a series of univariate ANOVAs. The independent variables and SES were transformed into discrete values, where positive was high and negative low (see Tables 3 and 4).

The table shows that in almost all cases the differences between the high and low groups are significant. However, with respect to social inclusion, the difference was much larger than with regard to social cohesion, save health where the differences were non significant. Finally we used multiple analyses of variance to ascertain the relationship/difference between the six independent variables and social inclusion and social cohesion (see Table 5).

In line with our earlier findings the relationship between the six independent variables and social inclusion is stronger than the relationship between the six independent variables and social cohesion.

4 Discussion

As noted there are links between the four components of social quality. But, the social quality theory does not indicate the direction of those links. It is hypothesised that the greater the altruism in a society, the more social cohesion, and this should lead to enhanced social quality. Our results found that there is not necessarily a positive relationship between these social quality components.

The regressions equation showed that the greater the altruism in a family there is lower socio-economic security in that family. There is a weak relationship (close to 0 intercorrelation, Table 2) between socio-economic security (income, employment security, housing conditions and payments and health) with social cohesion variable, altruism. A report on employment and caregiving (Employment and caregiving: is there a balance? 1997) found that multiple role demands often take their toll on work related responsibilities. Some of the effects on employment and trying to find a balance are: absenteeism, tardiness, work interruptions, missed advancement opportunities and increased job stress. Other consequences that might affect work are physical fatigue, depression, decreased quality of care, interruptions during the work day related to the caregiving role, emotional upsets and taking time off.

4.1 Income and Employment

Castillo and Carter (2002) found that that high levels of altruism and trust depress livelihood generation in rural communities. Families are paying a price to care for aging parents. This includes straining finances. It is also hurting businesses as workers interrupt their workday, call in sick or quit their jobs to tend to their parents (Donnelly and Bouffard 2004). It is employed women who start caregiving that are more likely to leave the labour force (Pavalko and Henderson 2006). In a Human Resources report (Employees taking care of parents increasingly utilize work hours to fulfill role; impacting company costs 2006) it was reported that employees are more and more taking time from their jobs to perform caregiving tasks for parents.

4.2 Health

Elderly caregiving spouses who report experiencing strain are at greater risk of death than elderly spouses who are not caregivers (Schulz and Beach 1999). Gallant and Connell (1998) state, that caregivers are at risk of having negative health behaviour. This finding is supported in a Health Link report (Studies point out risk of depression high among caregivers 2004). It was reported that studies point out risk of depression high among caregivers. Nearly one-third of those who care for terminally ill loved ones at home may suffer from depression. Ansorge (2006) states, that caregivers often neglect their health. Many caregivers are at high risk of exhaustion and depression, poor eating and exercise habits and increased use of medications and alcohol.

Social quality has been presented as a theory (Beck et al. 1997b). The social quality theory implies that through the application of ‘social quality indicators’ of its components we can assess both economic and social progress that measures the level of the daily lives of a population. The social quality theory states that “the social” is manifested within the framework of collective identities. We have analysed the relationship between the social quality components social inclusion and social cohesion with socio-economic security within the collective identity, the family. Our analysis demonstrates that there is reasonable but positive significant relationship between social inclusion and socio-economic security. Berman and Phillips (2004) hypothesise that resources associated with social cohesion will facilitate and enable the enhancement of socio-economic security by providing the right environment in which they may flourish. They conclude that according to social quality theory socio-economic security will be maintained where people trust each other and where there are strong associational networks. We found no internal consistency among two social quality components, socio-economic security and social cohesion.

Social quality literature has informed us that there is a blurred area between the different components of social quality (Berman and Phillips 2004). This observation queries social quality theory on a conceptual level. Our study takes one step forward in the study of social quality theory. We found that there is an inconsistency between the relationship of two social quality components, social cohesion and socio-economic security. These findings are a first step in analyzing the use of social quality as a theoretical concept.

Notes

See: Journal of Social Quality (2005), 5/1&2

See the rightmost column in Table 2.

References

Amsterdam Declaration on Social Quality. (1997). Retrieved May 8, 2007, from European Foundation on Social Quality web site: http://www.socialquality.org/site/index.html

Ansorge, R. (2006). WebMD medical news. Retrieved from http://www.webmd.com/content/Article/127/116843.htm

Baubock, R. (1995). Social and cultural integration in civil society. Paper presented at the meeting on Integration and Pluralism on Societies of Immigration, Jerusalem, Israel.

Beck, W., van der Maesen, L., Thomése, F., & Walker, A. (2001). Social quality: A vision for Europe. The Hague: Kluwer International.

Beck W., van der Maesen L., & Walker A. (Eds.) (1997a). The social quality of Europe. The Hague: Kluwer International.

Beck, W., van der Maesen, L., & Walker, A. (1997b). Social quality: From issue to concept. In W. Beck, L. van der Maesen, & A. Walker (Eds.), The social quality of Europe (pp. 263–297). The Hague: Kluwer Law International.

Berman, Y., & Phillips, D. (2000). Indicators of social quality and social exclusion at national and community level. Social Indicators Research, 50, 329–350.

Berman, Y., & Phillips, D. (2004). Indicators for social cohesion. Retrieved May 8, 2007, from European Foundation on Social Quality web site: http://www.socialquality.org/site/ima/Indicators-June-2004.pdf

Castillo, M., & Carter, M. R. (2002). The economic impacts of altruism, trust and reciprocity: An experimental approach to social capital. Retrieved May 8, 2007, from http://www.csae.ox.ac.uk/conferences/2002-UPaGiSSA/papers/Castillo-csae2002.pdf

Delanty, G. (1998). Social theory and European transformation: Is there a European society? Sociological Research Online, 3, Retrieved May 8, 2007, from http://www.socresonline.org.uk/3/1/1.html

Donnelly, F. X., & Bouffard, K. (2004). Families pay the price to care for aging parents. The Detroit News, Retrieved May 8, 2007, from http://detnews.com/2004/specialreport/0402/01/a01-51842.htm

Employees taking care of parents increasingly utilize work hours to fulfill role; impacting company costs. (2006). Managing your HR. Retrieved May 8, 2007, from http://www.managingyourhr.com/articles/07-06/8.shtml

Employment and caregiving: Is there a balance? (1997). Senior series SS-119–97. Retrieved on May 8, 2007, from The Ohio State University Extension web site: http://ohioline.osu.edu/ss-fact/pdf/0119.pdf#search = %22Caregiving%20and%20Employment%22

Flynn, P. (1997, November). Modernising and improving social protection in Europe. Paper presented to the Commission proposals to the Special Jobs Summit, European Commission, Brussels.

Gallant, M. P., & Connell, C. M. (1998). The stress process among dementia spouse caregivers: Are caregivers at risk for negative health behavior change? Research on Aging, 20, 267–297. Retrieved May 8, 2007, from http://roa.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/20/3/267

Giddens, A. (1990). The consequences of modernity. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Hefner, R. W. (1998). Civil society: Cultural possibility of a modern ideal. Society, 35, 16–27.

Hermann, P. (2004). Empowerment. Retrieved on May 8, 2007, form European Foundation on Social Quality web site: http://www.socialquality.org/site/ima/Empowerment-febr-2004.pdf

Hlynka, D., & Yeaman, A. R. J. (1992). Postmodern educational technology, ERIC Digest. Retrieved May 8, 2007, from http://www.csu.edu.au/research/sda/Reports/pmarticle.html

Kamen, C. S. (2002).”Quality of life” research at the Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. Social Indicators Research, 58, 141–162.

Katsikides, S. (1998). Sociological context and information technology. International Review of Sociology, 8, 34–49.

Keizer, M. (2004). Social quality and the component of socio-economic security. Retrieved on May 8, 2007, form European Foundation on Social Quality web site: http://www.socialquality.org/site/ima/Socio-Economic-Febr-2004.pdf

Klitgaarde, R., & Fedderke, J. (1995). Social integration and disintegration: An exploratory analysis of cross-country data. World Development, 23, 357–369.

Lockwood, D. (1999). Civic integration and social cohesion. In I. Gough, &G. Olofsson (Eds.), Capitalism and social cohesion (pp. 63–83). Basingstoke: Macmillan.

McGowan, J. (1991). Postmodernism and its critics. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Pavalko, E. K., & Henderson, K. A. (2006). Caring for family and working for pay: Do workplace policies ease the burden? Retrieved May 8, 2007, from http://www.bcfwp.org/Conference_papers/PavalkoPaper.pdf#search = %22Caregiving%20and%20employment%3A%20the%20impact%20of%20workplace%22

Phillips, D. (2001). Social capital, social cohesion and social quality. Paper presented at the European Sociological Association Conference, Social Policy Network, Helsinki.

Phillips, D. (2006). Quality of life: Concept, policy and practice. London: Routledge.

Phillips, D. (2007). Social cohesion and the sustainable welfare society. Paper presented at the Second Asian Conference on Social Quality and Sustainable Welfare Societies, National Taiwan University.

Phillips, D., & Berman, Y. (2000). Indicators of community social quality. Paper presented at The International Society for Quality of Life Studies Conference, Gerona, Spain.

Phillips, D., & Berman, Y. (2001). Social quality: Definitional, conceptual and operational issues. In W. Beck, L. van der Maesen, & A. Walker (Eds.), Social quality: A vision for Europe (pp. 125–145). The Hague: Kluwer Law International.

Phillips, D., & Berman, Y. (2003), Social quality and ethnos communities: Concepts and indicators. Community Development Journal, 38, 344–357.

Schulz, R., & Beach, S. R. (1999). Caregiving as a risk factor for mortality: The caregiver health effects study. The Journal of the American Medical Association, 282, 2215–2219.

Shamir, M., & Arian, A. (1999). Collective identity and electoral competition in Israel. The American Political Science Review, 93, 265–277.

Smart, B. (1990). On the disorder of things: Sociology, postmodernity and the ‘end of the social’. Sociology, 24, 397–416.

Studies point out risk of depression high among caregivers. (2004). Health link: Mental health. Retrieved May 8, 2007, from http://www.ynhh.org/healthlink/mentalhealth/mentalhealth_3_04.html

Taylor-Gooby, P. (1994). Postmodernism and social policy: A great leap backwards? Journal of Social Policy, 23, 384–404.

Titmuss, R. (1971). The gift relationship: From human blood to social policy. New York: Vintage Books.

van der Maesen, L. J. G. (2002). Social quality, social services and indicators: A new European perspective? Paper presented at the Conference on Indicators and Quality of Social Services in a European context, German Observatory for the Development of Social Services in Europe, Berlin.

van der Maesen, L. J. G., & Keizer, M. (2002). From theory to practice. ENIQ working document no. 4. Retrieved on May 8, 2007, form European Foundation on Social Quality web site: http://www.socialquality.nl/site/ima/Working_Paper_1.pdf

van der Maesen, L. J. G., & Walker, A. (2005). Indicators of social quality: Outcomes of the European Scientific Network. The European Journal of Social Quality, 5, 8–24.

van der Maesen, L., Walker, A., & Keizer, M. (2005). European network indicators social quality: Final report. Retrieved on May 8, 2007, form European Foundation on Social Quality web site: http://www.socialquality.nl/site/ima/FinalReportENIQ.pdf

Walker, A., & Wigfield, A. (2004). The social inclusion component of social quality. Retrieved on May 8, 2007, form European Foundation on Social Quality web site: http://www.socialquality.nl/site/ima/Social-Inclusion-febr-2004.pdf

Warman, A. (1998). Family obligations in Europe: An exploration of family/state boundaries. Social Work in Europe, 5, 48–55.

World Bank (1998). The initiative on defining, monitoring and measuring social capital: Overview and program description. Retrieved on May 8, 2007, form Social Development Family: Environmentally and Socially Sustainable Development Network, World Bank web site: http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTSOCIALCAPITAL/Resources/Social-Capital-Initiative-Working-Paper-Series/SCI-WPS-01.pdf

Acknowledgement

The authors are most grateful to Mr David Phillips of the Department of Sociological Studies of the University of Sheffield for reading this paper and making valuable comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Monnickendam, M., Berman, Y. An Empirical Analysis of the Interrelationship between Components of the Social Quality Theoretical Construct. Soc Indic Res 86, 525–538 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-007-9189-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-007-9189-0