Abstract

This study develops and tests a model of quality of college life (QCL) of students in Korea. In this study, QCL of students is conceptualized in terms of needs satisfaction and affect balance. It has been hypothesized that satisfaction with education services, administrative services, and facilities have a significant impact on QCL, which in turn positively influences identification, positive word of mouth, and overall quality of life. The results of a survey on 228 Korean college students largely support the model. Managerial and policy implications are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Studies on the overall quality of life of university students focus on the subjective well-being of university students. According to the bottom up spill over theory of life satisfaction, student’s overall life is composed of a set of specific life domains including family, friends, religion, college, and among others (Andrew and Withey 1976). This study focuses on satisfaction with the college life domain, or quality of college life.

Recently, Sirgy et al. (2007) reported a study developing a new measure for quality of college life (QCL) of students. Quality of college life (QCL) refers to the overall feeling of satisfaction students experience in college. The study conceptualized the college life domain as a distinctive sub-life domain affecting the overall life domain such as family or work life domain. The study also found that satisfaction with the university’s academic aspects, social aspects, and facilities have a positive influence on QCL of students.

The main purpose of this paper is to extend Sirgy et al.’s (2007) study in the following ways. First, we will conceptualize QCL in terms of the affective component as well as the cognitive component. The QCL in this study will be a composite of various need satisfaction and affect balance that students experience during college life. Second, we want to test the model of QCL in the context of Korean students in order to cross culturally validate the findings of Sirgy et al.’s (2007) study. Third, this study will examine the consequences of QCL including identification and positive word of mouth.

The paper proceeds as follows. We first discuss the consequences of QCL and suggest hypotheses accordingly. We also present the major antecedents to QCL along with the hypothesis. We then discuss the method and study results. Managerial implications are discussed.

Understanding the key factors affecting QCL of students will help university managers allocate resources effectively to maximize QCL. A better understanding of the consequences of QCL will help university administrators emphasize the importance of QCL and help them design effective ways to enhance positive word of mouth, identification, and overall quality of life.

2 Conceptual Development

Figure 1 shows the conceptual model of our study. The model posits students’ satisfaction with education services, administrative services, and facilities has a positive influence on QCL. The model also posits that QCL of students has a positive influence on the student’s identification with the college, intention to generate positive word of mouth, and the overall quality of life (QOL)

Quality of life (QOL) refers to the degree to which an individual judges the overall quality of his or her life as a whole in a favorable way (Venhooven 1984). QOL include both a cognitive evaluation and positive and negative effects (Andrews and Withey 1976). The cognitive component (life satisfaction) refers to the perceived discrepancy between aspiration and achievement, ranging from the perception of fulfillment to that of deprivation (Campbell et al. 1976), while the affective component the pleasantness experienced in feelings, emotions, and moods (Campbell et al. 1976).

2.1 Quality of College Life (QCL)

Quality of life (QOL) is different from Quality of college life (QCL) in that QCL is a sub-domain of QOL (Sirgy et al. 2007). In this study, we conceptualize QCL as the overall feeling of satisfaction students experience with life at college. QCL is the satisfaction within the college life domain, a sub-domain of overall life; and one can argue that QCL vertically spills over to the super-ordinate domain or QOL (Andrews and Withey, 1976).

QOL has been conceptualized as having affective components as well as cognitive components (Argyle 1996; Diener et al. 1995). That is, QOL is conceptualized in terms of satisfaction with life, presence of positive affect and absence of negative affect. Following this, we conceptualize QCL as having two dimensions (e.g., Cha 2003; Sam 2000; Pilcher 1998). That is, QCL is defined as a composite of the cognitive component and affective component and is conceptualized as follows.

-

Quality of college life (QCL)

-

= [cognitive QCL + affective QCL component]/2

-

= [needs satisfaction in college life + (PA-NA)]/2

Where

-

PA = positive affect experienced in the college life domain

-

NA = negative affect experienced in the college life domain

2.1.1 Cognitive QCL

The cognitive component of QCL refers to the global assessment of one’s college life according to one’s chosen criteria (Diener and Emmons 1984). The cognitive affective component of QCL reflects the conceptualization of QCL in terms of satisfaction of human needs (Sirgy 1986). The cognitive component of QCL include satisfaction with health and safety needs, economic and family needs, social needs, esteem needs, self-actualization needs, knowledge needs, and aesthetics needs (Sirgy et al. 2007). These need dimensions are based on the need hierarchy model.

2.1.2 Affective QCL

The affective component of QCL reflects the difference between the positive affect and negative affect that have occurred in the past several months’ experience (Bradburn 1969; Diener et al. 1995).

Respondents were asked to answer the overall feeling during the past three to six months in college since experiences during the period give significant influence to one’s perceived well being (Suh et al. 1996). Positive affect (PA) include feelings such as enthusiastic, interested, determined, excited, inspired, alert, active, strong, proud, and attentive. Negative affect (NA) includes feelings such as scared, afraid, upset, distressed, jittery, nervous, ashamed, guilty, irritable, hostile (Brandburn 1969; Diener et al. 1995; Plutchick 2003). Affective component of QCL is calculated as the difference between the PA and NA (Diener et al. 1995).

Studies have shown negative affect, positive affect, and life satisfaction are conceptually distinct and empirically separable (Lucas et al. 1996). We conceptualize QCL as a composite of cognitive and affective component. Specifically, we measured QCL as the degree to which students have a needs satisfaction from their college life domain and the degree to which students experience positive and negative affect in their college life. For affective component, we used the affect balance, the difference between the frequency of positive affect experience and the frequency of negative affect experience (Watson et al. 1988). We focused on the frequency of emotions rather than intensity of emotions, as previous studies have found that frequency of emotional experience is more important than intensity of emotional experience in forming the overall subjective well being (e.g., Diener et al. 1991).

2.2 Quality of College Life and Word of Mouth

Word of mouth is the interpersonal communication among members of the reference group (Assel 2004). Word of mouth communication includes referral behaviors in that people communicate positive or negative things about the product based on their experience. Word of mouth communication is reliable as it is not directly related to the consumer’s self interest (Anderson et al. 1994). Word of mouth is effective in enhancing a firm’s long term financial performance (Reicheld 2003).

This study posits that QCL of students has a positive influence on consumer’s positive word of mouth. When students are satisfied with and are happy about their college life, students are likely to say positive things about the college. In other words, when QCL is high, students are likely to generate positive word of mouth about their college life (Hall and Stamp 2003; Hennig-Thurau et al. 2001; Verhoef, Franses, and Hoekstra 2002). Based on this discussion, we propose the following.

H1

QCL of students has a positive influence on their word of mouth intentions.

2.3 Quality of College Life and Identification

When students have a high QCL, they are likely to identify with their college (Hennig-Thurau et al. 2001). This is because when QCL is high, the students are likely to perceive the college as attractive and thereby identifies with its image (Bhattacharya and Sen 2003; Brewer 1991; Tajfel and Turner 1985).

We posit that when students have a high QCL at the college, they tend to perceive the identity of the college as attractive, which will increase the student’s identification with the college. This perceived identification increases commitment to the university (Hennig-Thurau et al. 2001). Based on this discussion, we propose the following.

H2

QCL of students has a positive influence on their identification with the college.

2.4 Quality of College Life and Quality of Life (QOL)

Quality of Life (QOL) of students refers to overall life satisfaction of students. QOL of students refers to satisfaction and feelings of happiness among students resulting from the range of life domains such as family life, social life, leisure life, financial life, college life, among others (Benjamin 1994).

There have been many studies focusing on QOL of students. Some used satisfaction with life scale (SWLS) among students to measure QOL of students (Sam 2001; Chow 2005). Other studies measured QOL in terms of cognitive and affective components. QOL is conceptualized in terms of satisfaction with life (SWLS) and affect balance, or the difference between positive affect and negative affect (Cha 2003; Sam 2001; Pilcher 1998). It has been found that the overall QOL of students is positively influenced by optimism, self esteem, and feelings of achievement (Chow 2005; Emmons and Diener 1986; Sam 2001; Schmuck et al. 2000).

We conceptualized QCL as a composite of the overall satisfaction and affective balance with college life. Based on the bottom-up spillover theory, therefore one can argue that QCL vertically spills over to the super-ordinate life domain or QOL (Andrews and Withey 1976). Based on this discussion, we propose the following.

H3

QCL of students has a positive influence on their overall quality of life (QOL).

2.5 Satisfaction with College Services and QCL

Satisfaction within a life domain is influenced by satisfaction with various services. For example, satisfaction with community is influenced by satisfaction with various services provided by the community (Sirgy et al. 2000). Satisfaction with college life is also influenced by the various services provided by the university (Sirgy et al. 2007).

We posit that QCL is influenced by various aspects of college services. The college services can be classified in terms of education services (professors and lecture), administrative services (services from supporting staff), facilities services (classrooms and other facilities) (Astin 1993; Chadwick and Ward 1987; Pate 1990; Simpson and Siguaw 2000).

Based on the bottom-up spillover theory of life satisfaction, Sirgy et al. (2007) found that satisfaction with academic aspects, social aspects, and facilities have a significant influence on QCL of students. That is, QCL as a life domain is influenced by the satisfaction with specific sub-domains. Based on this discussion, we propose the following.

H4

College Service dimensions have a positive impact on Quality of College Life.

H4a

Satisfaction with education services will have a positive impact on QCL.

H4b

Satisfaction with administrative services will have a positive impact on QCL

H4c

Facilities satisfaction will have a positive impact on QCL.

3 Method

3.1 Sampling

In order to test the model of this study, we conducted a survey with undergraduate college students attending business courses in Korea. We randomly selected 269 respondents from the student directory and finally received 228 complete and usable data. The respondents were mostly in their twenties and were comprised of 128 men (56.1%) and 110 women (45.9%). In addition, more than 99% of the respondents have at least one year experience in college, and 53.8% more than two years.

3.2 Measurement

3.2.1 Quality of College Life

Quality of College Life (QCL) was defined as the overall feeling of satisfaction students experience with life at the college (Sirgy et al. 2007, p. 346). In this study, QCL is conceptualized and measured by a composite of cognitive QCL (needs satisfaction in college) and affective QCL (positive and negative affect in college). Specifically, we developed a measurement for cognitive QCL adapting from Sirgy et al. (2001)’s Quality of Work Life measurement. Cognitive QCL scale is conceptualized as a summation of satisfaction of seven needs categories: (1) health and safety needs, (2) economic and family needs, (3) social needs, (4) esteem needs, (5) actualization needs, (6) knowledge needs, and (7) aesthetics needs (see Appendix for the scale items).

Affective QCL is measured using the Intensity and Time Affect Scale (Diener, Smith, and Fugita 1995). In the scale respondents are asked to comment on the overall feelings they experienced during the past three to six months of college life. This is because one’s perceived well-being is significantly influenced by recent experiences within a six month time frame. (Suh et al. 1996). This scale was designed to tap “the extent to which students experience eight kinds of positive emotions and sixteen negative ones.” A seven-point Likert scale (1 = Never to 7 = Always) was used. Previous studies found that the positive affect and negative affect have a low correlation and have independent influence on overall quality of life (Bradburn 1969). Affective QCL is measured by subtracting negative affect from positive affect.

3.2.2 Satisfaction with College Services

Satisfaction with college services is conceptualized as having three sub domains: educational service, administrative service, and facilities. The measures of satisfaction with college services were adapted from previous studies (Astin 1993; Simpson and Siguaw 2000; Whang 2000).

Satisfaction with educational services is composed of satisfaction with courses, instructors, and overall educational services. The measurement items for this construct include “I am satisfied with the education services being provided by my university/college.” The scale was found to be reliable (α = 0.893, ρ = 0.905). The results of confirmatory factor analysis for education services scale indicate that this scale provided a good fit to the data [χ2 = 9.603 P = .00, df = 4, GFI = 0.983, CFI = 0.992, NFI = 0.986, RMSEA = 0.082].

Satisfaction with administrative services (α = 0.816, ρ = 0.831) is composed of satisfaction with core administrative services, peripheral administrative services, service provider’s attitude, and overall administrative services. The measurement items for this construct include “Administrative services provided by my university/college are helpful to my life as a student.” The administrative services scale provided a good fit to the data [χ2 = 8.789, P = .00, df = 6, GFI = 0.988, CFI = 0.992, NFI = 0.977, RMSEA = 0.043].

Satisfaction with facilities (α = 0.856, ρ = 0.866) is composed of satisfaction with educational facilities, social activity related facilities, convenience facilities, campus environment, and overall facilities. The measurement items for this construct include “Facilities of my university/college are well structured” (1 = not at all satisfied to 7 = very much satisfied). The facilities scale provided a good fit to the data [χ2 = 11.454, P = .00, d.f = 8, GFI = 0.986, CFI = 0.994, NFI = 0.982, RMSEA = 0.096].

The measurement model for the satisfaction with college services is conceptualized and tested as a formative model as shown in Fig. 2. The results are summarized in Tables 1–3.

3.2.3 Word of Mouth

Word of Mouth (α = 0.923, ρ = 0.920) was measured using three indicators adapted from Arnett et al. (2003). The items include (1) I usually talk about my university/college favorably, (2) I often bring out the positive aspects about my university/college during conversations with friends, (3) I usually try to give positive comments on my university/college (1 = strongly agree to 7 = strongly disagree).

3.2.4 Identification

Identification with college/university (α = 0.840, ρ = 0.903) was measured with six indicators adapted from Mael and Ashforth (1992). Items include (1) I feel uncomfortable when I hear bad things about my university/college from other people, (2) I am curious about the way other people think about my university/college, (3) I’d rather call it ‘my university/college’ instead of its official name, (4) Success of my university/college goes together with my personal achievement, (5) I feel appraised when I hear good things about my university/college from other people, (6) I feel ashamed when I hear negative news from the multimedia (1 = strongly agree to 7 = strongly disagree).

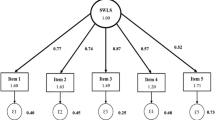

3.2.5 Quality of Life

Quality of Life (α = 0.851, ρ = 0.922) was measured with five indicators adopted from SWLS (Satisfaction with Life Scale) by Diener et al. (1985). Items include (1) my life is close to my ideal life in general, (2) Various conditions that construct my life are very good overall, (3) I am satisfied with my current life, (4) I’ve been achieving important things throughout my life so far, and (5) If I were to be born again, I would maintain my current life style (1 = strongly agree to 7 = strongly disagree).

3.3 Construct validation

To ensure the reliability and uni-dimensionality of construct measurement, we first conducted within construct confirmatory analyses to purify the items. All of the measurement items are uni-dimensional and the model provided a good fit to the data. After deleting one item from identification measure due to large error covariance, we conducted across construct confirmatory factor analyses.

The fit indices for the across construct confirmatory factor analysis indicated that the model provided a good fit to the data (χ2 = 379.450, P = .00, df = 231, CFI = 0.913, GFI = 0.834, NFI = 0.823, RMSEA = 0.05). We viewed the above model as adequate in spite of the significant chi-square statistics, given its strict assumptions and sensitivity to the sample size (Bagozzi et al. 1991). The results of reliability and validity tests are summarized in Table 4.

The CFA results indicate that all items are significantly loaded to their hypothesized factors (ranging from 0.639 to 0.927) without high cross loadings, indicating the convergent validity of measurement items (Anderson and Gerbing 1988). We assessed the internal validity of all measures by computing Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability (ranging from 0.696 to 0.922) for each construct comprising multiple indicators. All the results are exceeding recommended guidelines, both 0.7 (Nunnally 1978), confirming the internal validity of given constructs.

Discriminant validity was tested in the following ways. First, we examined the confidence interval of latent factor correlations and found that none of the 95% confidence intervals of the latent factor correlation matrix contained a value of 1.0. Second, we conducted a series of Chi-square difference tests for each pair of constructs between the constrained model and the unconstrained model. In all cases, the unconstrained model provided a significantly better fit to the data than did the constrained model (P < .01). Third, the phi matrix indicated that the variance of underlying constructs was higher than the correlations between constructs. All these results supported the convergent and discriminant validity of the measures used in the study (Table 5).

4 Results

We tested the proposed conceptual model (Fig. 1) using structural equations modeling. The empirical estimates for the “main effects” model are shown in Table 6. The result shows the coefficients and fit statistics and indicates a good fit to the data (χ2 = 42.326, ff = 493, P = .00; GFI = .826; CFI = .913; NFI = .821; RMSEA = .056; RMR = .093).

H1 posits that QCL has a significant influence on students’ intention for positive word of mouth. The results indicate that QCL does have a positive influence on positive word of mouth intention (estimate = 0.495, P < .050), supporting H1.

H2 states that QCL has a significant influence on students’ identification with the university. The results indicate that QCL has a significant influence on identification with college (estimate = 0.304, P < .05). The results support H2.

H3 deals with the bottom up spill over from QCL to overall QOL. In particular, H3 posits that QCL has a positive influence on their overall quality of life (QOL). The results show that QCL does indeed have a positive influence on overall quality of life (estimate = 0.594, P < .05). The results provide support for H3.

H4 is about the factors affecting QCL. H4 specifically states that satisfaction with various college services has a positive impact on QCL. The results indicate that QCL is significantly influenced by satisfaction with educational services (estimate = 0.345, P < .05) and satisfaction with facilities (estimate = 0.426, P < .05). Yet, satisfaction with administrative services did not have a significant influence on QCL (estimate = 0.032, P > .05). The results provide support for H4a and H4c, but not for H4b. The lack of support for H4b (administrative services) is that students have limited interaction with administrative staff and thus consider this factor less important in determining their QCL. All the results are summarized in Table 7.

5 Discussion

5.1 Summary of Findings

In this paper, we measured the QCL construct as a combination of cognitive QCL and affective QCL, and this new measure was proved to be better than the cognitive measurement-only model through our data. We tested the effects of QCL on students’ attitude towards their own college and categorized the type of college services as key determinants of QCL: education service, administrative service, and facilities. It has been found that QCL has a positive impact on identification with college, positive word-of-mouth, and overall quality of life. We also found that students’ satisfaction on education service and facilities has positive influences on QCL while the impact of administrative service satisfaction shows no significance.

5.2 Managerial Implications

The findings of this study provide college administrators with the following managerial implications. First, it has been found that QCL is significantly influenced by satisfaction of educational services and facilities. Satisfaction with administrative services has a limited impact on QCL. The finding suggests that it is necessary for universities to put higher priority on enhancing educational services and maintaining high quality facilities. The findings indicate that QCL is heavily influenced by services that students interact with more often.

Second, this study also suggests some practical ways to enhance satisfaction with university services. With regard to ways to enhance satisfaction with educational services, we found that satisfaction is more influenced by satisfaction with the quality of class materials than satisfaction with instructors. We found that satisfaction with administrative services is significantly influenced by satisfaction with administrative service provider’s attitude domain and satisfaction with core administrative services. With respect to satisfaction with facilities, we found that facility satisfaction is significantly influenced by satisfaction with educational facilities, social activity facilities, convenience facilities, and campus environment.

Third, the study’s findings indicate that QCL has a positive impact on identification with college, positive word-of-mouth and overall quality of life (QOL). Creating a positive word of mouth through high QCL is very important considering the intangible nature of educational services.

Fourth, it has been found that QCL has a positive influence on the students’ identification with the university. When students truly internalize the norms of the university, they come to identify themselves with the university. The feelings of identification are likely to initiate their intention to make donations in the future (Callero 1985).

Fifth, this study found that QCL has a significant influence on one’s overall QOL. Various experiences from the college life domain are summarized in QCL, which in turn vertically spills over to the overall quality of life (Sirgy et al. 2007).

5.3 Limitations and Direction for Future Research

Despite the merits, the study has the following limitations. First, this study used a convenient sample. Future studies should use a more representative sample.

Second, the data in this study is collected in Korea, a collectivistic culture. Studies have found that people in collectivistic cultures have an interdependent self concept and have a higher level of social support (Diener et al. 2000). While an independent self concept is emphasized in the individualistic society, collective aspects of self are emphasized in the collectivistic society (Markus and Kitayama 1991; Triandis 1989). Future studies should examine whether the findings on the outcomes of QCL can be applied to other individualistic cultures.

Third, this study measured QCL as a composite of cognitive component (need satisfaction) and affective component (PA-NA). In doing so, we did not use the weight or importance of each component in forming QCL. Future should examine the underlying conditions (groups or situations) where a component becomes more important than the other.

Fourth, this study focused on the identification with college, positive word-of-mouth, and overall QOL as consequences of QCL. Other variables, such as donation intentions or emotional attachment to college can be of the possible additional attitudinal consequences of this study. Future studies can extend the conceptual model of this study by incorporating these variables.

Fifth, the conceptual model of this study is largely based on the bottom up spill over theory of life satisfaction (Andrews and Withey 1976). With a top down approach to life satisfaction, one can argue that one’s QCL is influenced by such personality variables such as optimism (Scheier et al. 1994), extraversion, neuroticism, openness, agreeableness, consciousness (Costa and McCare 1985), and self esteem (Diener and Diener 1995). Future studies should examine the role of these personality factors in QCL.

Despite the above limitations, we believe this study represents an important step towards our understanding on QCL and its consequences. It is hoped that future studies will be directed towards a better understanding on measurement of QCL and its antecedents and consequences.

References

Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommendation of two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411–423.

Anderson, E. W., Fornell, C., & Lehman, D. (1994). Customer satisfaction, market share, and profitability: Findings from Sweden. Journal of Marketing, 58, 53–66.

Andrews, F. M., & Withey, S. B. (1976). Social indicators of well-being: America’s perception of quality of life. New York: Plenum Press.

Argyle, M. (1996). Subjective well being. In A. Offer (Ed.), Pursuit of the quality of life (pp. 18–45). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Arnett, D. B., German, S. D., & Hunt, S. D. (2003). The identity salience model of relationship marketing success: The case of nonprofit marketing. Journal of Marketing, 67(2), 89–105.

Assael, H. (2004). Consumer behavior, a strategic approach. New York: Houghton Mifflin.

Astin, A. (1993). What matters in colleges? Four critical years revisited. San Francisco: Josssey-Bass Publishers.

Bagozzi, R. P., Yi, Y., & Phillips, L. W. (1991). Assessing construct validity in organizational research. Administrative Science Quarterly, 36(3), 421–458.

Benjamin, M. (1994). The quality of student life: Toward a coherent conceptualization. Social Indicators Research, 31, 205–264.

Brandburn, M. (1969). The structure of psychological well being. Chicago: Adline.

Bhattacharya, C. B., & Sen, S. (2003). Consumer-company identification: A framework for understanding customer’s relationships with companies. Journal of Marketing, 67(April), 76–88.

Brewer, M. B. (1991). The social self: On being the same and different at the same time. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 17(5), 475–482.

Callero, P. L. (1985). Role-identity salience. Social Psychology Quarterly, 48(3), 203–215.

Campbell, A. C., Philip, E. C., & Rodgers, W. L. (1976). The quality of American life. New York: The Russell Sage Foundation.

Cha, K. H. (2003). Subjective well-being among college students. Social Indicators Research, 62, 455–477.

Chadwick, K., & Ward, J. (1987). Determinants of consumer satisfaction with education: Implications for college and university administrators. College and University, 62, 236–246.

Chow, H. P. H. (2005). Life satisfaction among university students in a canadian prairie city: A multivariate analysis. Social Indicators Research, 70, 139–150.

Costa, P. T., Jr., & McCrae, R. R. (1985). The NEO personality inventory. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 71–75.

Diener, E., & Emmons, R. A. (1984). The independence of positive and negative affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 47, 1105–1117.

Diener, E., & Diener, M. (1995). Cross cultural correlates of life satisfaction and self esteem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68, 653–663.

Diener, E., Sandvik, E., & Pavot, W. (1991). Happiness is the frequency, not the intensity, of positive versus negative affect. In F. Strack, M. Argyle, & N. Schwarz (Eds.), Subjective well being (pp. 119–139). Oxford UK: Pergamon.

Diener, E., Smith, H., & Fujita, F. (1995). The personality structure of affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69, 130–141.

Diener, E., Scollon, N., Oishi, S., Dzokoto, V., & Suh, E. (2000). Positivity and the construction of life satisfaction judgment: Global happiness is not the sum of its parts. Journal of Happiness Studies, 1, 159–176.

Emmons, R. A., & Diener, E. (1986). Influence of impulsivity and sociability on positive and negative affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 50, 1211–1215.

Hennig-Thurau, T., Langer, M. F., & Hansen, U. (2001). Modeling and managing student loyalty––An approach based on the concept of relationship Quality. Journal of Services Research, 3(4), 331–344.

Hall, D., & Stamp, J. (2003). Meaningful marketing. New York: Dug Hall.

Lucas, R., Diener, E., & Suh, E. (1996). Discriminant validity of subjective well being measures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71, 616–628.

Mael, F., & Ashforth, B. E. (1992). Alumni and their alma mater: A partial test of the reformulated model of organizational identification. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 13, 103–123.

Markus, H., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review, 98, 244–253.

Nunnally, J. C. (1978). Psychometric theory. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Pate, W. S., Jr. (1990). Modeling consumer satisfaction, determinants of satisfaction. The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Pilcher, J. J. (1998). Affective and daily event predictors of life satisfaction in college students. Social Indicators Research, 43(3), 291–306.

Plutchick, R. (2003). Emotions and life: Perspectives from psychology, biology, and evolution. American Psychological Association.

Reichheld, F. F. (2003). The one number you need to grow. Harvard Business Review, 81(12) 46–54, 124.

Sam, D. L. (2001). Satisfaction with life among international students: An exploratory study. Social Indicators Research, 53, 315–337.

Scheier, M. F., Carver, C. S., & Bridges, M. W. (1994). Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self mastery, and self esteem)’: A reevaluation of the life orientation test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67, 1063–1078.

Schmuck, P., Kasser, T., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). Intrinsic and extrinsic goals: Their structure and relationship to well-being in German and U. S. college students. Social Indicators Research, 50, 225–241.

Simpson, P. M., & Siguaw, J. A. (2000). Student evaluations of teaching: An exploratory study of the faculty response. Journal of Marketing Education, 22(3), 199–213.

Sirgy, M. J. (1986). A quality of life theory derived from Maslow’s development perspective: ‘Quality’ is related to progressive satisfaction of a hierarchy of needs, lower order and higher. American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 45, 329–432.

Sirgy, M. J., Rahtz, D., Cicic, M., & Underwood, R. (2000). A method for assessing residents’ satisfaction with community-based services: A quality-of-life perspective. Social Indicators Research, 49, 279–316.

Sirgy, M. J., Grezeskowiak, S., & Rahtz, D. (2007). Quality of college life (QCL) of students: Developing and validating a measure of well being. Social Indicators Research, 80, 343–360.

Suh, E., Diener, E., & Fujita, F. (1996). Events and subjective well being: Only recent events matter. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(5), 1091–1102.

Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1985). The social identity theory of ingroup behavior. In S. Worchel & W. G. Austin (Eds.), Psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 6–24). Chicago: Nelson Hall.

Triandis, H. C. (1989). The self and social behavior in differing cultural context. Psychological Review, 96, 506–520.

Venhooven, R. (1984). Conditions of happiness. Dordrecht: D. Reidel.

Verhoef, P. C., Franses, P. H., & Hoekstra, J. C. (2002). The effect of relational constructs on consumer referrals and number of services purchased from a multiservice provider: Does age of relationship matter? Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 30(3), 202–216.

Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scale. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 1063–1070.

Whang, H. Y. (2000). Study on education service satisfaction determinants. The Korea University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yu, GH., Lee, DJ. A Model of Quality of College Life (QCL) of Students in Korea. Soc Indic Res 87, 269–285 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-007-9172-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-007-9172-9