Abstract

Body image comparisons on social networking sites (SNS) have been found to be associated with disordered eating among western young women, however, the inner mechanism driving this association is largely unknown. Based on social comparison, sociocultural, and objectification theories, the present study aimed to investigate the association between body image comparisons on SNS and restrained eating, as well as the mediating role of body shame and the moderating roles of body appreciation and body mass index (BMI) among Chinese young adult women. A sample of 567 Chinese college women were recruited to complete a questionnaire assessing body image comparisons on SNS, body shame, body appreciation, restrained eating, and information about weight and height. Results showed that body image comparisons on SNS were positively associated with restrained eating and that body shame significantly mediated this association. Furthermore, body appreciation and BMI each moderated the association between body shame and restrained eating as well as the association between body image comparisons on SNS and restrained eating. These results not only have theoretical implications, but also provide guidance for prevention interventions targeting negative body image and disordered eating among college women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In recent years, non-clinical restrained eating behavior adopted by worldwide young women in pursuit of slim and thin bodies has gradually been more and more popular. According to a systematic review and meta-analysis by Santos et al. (2017), the prevalence of weight loss attempts among adult women worldwide was 58% and more than two-thirds of participants attempted to lose weight using dieting. A survey of 850 Chinese college women also found that restrained eating is one of the most common means they use to lose weight (Wang et al. 2015). The high prevalence of restrained eating was closely associated with a range of negative outcomes including damaged brain development and mental functioning, depressive symptoms, and eating disorders (Ferreira et al. 2016; Wade et al. 2012). Against this background, research has focused on risk factors contributing to restrained eating to provide effective advice on prevention interventions. Relevant studies found that consumption of media, especially sources that purvey images of ideal slender women, is one of the robust factors contributing to restrained eating (Mclean et al. 2016).

As a basic application and widely used media source in the current internet age, Social Networking Sites (SNS) have been common means for social interaction, communication, and information-sharing. Examples of popular SNS include Facebook and YouTube worldwide, as well as WeChat Moments and Qzone in China. According to a report by the Pew Research Center (2019), SNS have been adopted by more than 70% young Americans aged 18–24, with a majority of users using SNS daily. In China (China Internet Network Information Center 2019), the usage rates of WeChat Moments and Qzone were 83.4% and 58.8% respectively, and the usage rate of young netizens was significantly higher than other groups.

In addition to being a widely used communication platform, SNS also feature user-created content, including appearance-oriented videos and pictures. For example, users can update their profile photos (Cohen et al. 2017) and post selfies (Niu et al. 2020) on SNS, both of which are appearance-focused. Due to this feature, SNS provide a perfect online environment to engage in body image comparisons for young women (Kim and Chock 2015). Relevant studies found that SNS use was associated with negative body image and disordered eating (Morgan et al. 2015; Venus et al. 2018). However, most of these studies have been conducted in western cultures and may lack of relevance to Chinese culture. Thus, in the present study we aimed to investigate the association between body image comparisons on SNS and restrained eating among Chinese college women, as well as identity mediating and moderating mechanisms in this association.

Body Image Comparisons on SNS and Restrained Eating

In accordance with social comparison theory, social comparison is a basic motivation, and upward social comparisons (comparisons with others doing better) may lead to unfavorable results (Festinger 1954; Xing and Yu 2005). Indeed, this pattern is confirmed for body image comparisons (Haferkamp and Krämer 2011). On SNS, a vast number of photos and videos containing body images are shared by users and offer the basis for body image comparisons processes (Wei et al. 2017). However, as a flexible self-presentation platform, SNS allow users to carefully choose and edit the information that they share (Feltman and Szymanski 2018; Krämer and Winter 2008). As a result, the photographs shared by users on SNS are often manipulated using various picture-editing tools (Mclean et al. 2015). In this way users may be overwhelmed by unrealistic beauty ideals posted by others (Bissell and Rask 2010; Fardouly et al. 2015), and comparisons to seemingly thinner or more attractive peers on SNS (i.e., upward comparison) may lead to desires for a thin body and accompanying weight loss behaviors. Indeed, appearance-focused SNS use has been associated with heightened weight and eating concerns (Rodgers and Melioli 2016). A recent experimental study also found that upward body image comparisons on social media were positively associated with the tendency to limit food intake (Fardouly et al. 2017). Based on these findings, we hypothesized that body image comparisons on SNS would be positively correlated with restrained eating (Hypothesis 1).

The Mediating Role of Body Shame

According to sociocultural theory, most women aspire to the thin beauty ideals presented on media despite their unnaturalness and inaccessibility (Tiggemann 2011; Tylka and Subich 2004). These desires result in negative body image and related negative feelings, such as body shame (Holland and Tiggemann 2016). Body shame is the affective component of objectified body consciousness and usually appears when a woman perceives that her body image fails to meet social ideals or standards (Fredrickson and Roberts 1997). According to objectification theory, body shame is usually induced by sociocultural factors, such as the thin ideals on mass media, and through body image comparisons (Fardouly and Vartanian 2016). Comparisons to the idealized photos posted on SNS may make people feel that they do not meet the ideal and thus develop negative evaluations and feelings about their bodies, including body shame (Duarte et al. 2015). In order to achieve these ideals, individuals may take certain measures such as restrained eating (Noll and Fredrickson 2010). Indirect evidence supports the conclusion that body image comparisons make individuals susceptible to negative body image and emotions (Rodgers et al. 2015; Tylka and Sabik 2010). Furthermore, Chinese college women with higher body shame have been found to be more likely to have eating disturbance at one-year follow-up (Jackson and Chen 2015). Relevant studies also showed body shame was positively associated with individual’s dieting and restrained eating behavior (Noll and Fredrickson 2010). Therefore, we hypothesized that body shame would mediate the relationship between body image comparisons on SNS and restrained eating (Hypothesis 2).

The Moderating Roles of Body Appreciation and BMI

Although body image comparisons on SNS may induce restrained eating through body shame, it is possible that not all users are equally influenced. A model of differential susceptibility to media effects proposes that dispositional susceptibility is an important factor affecting the media-use-and-effects relationship (Valkenburg and Peter 2013), and media effects can be enhanced or reduced by users’ dispositional traits, such as appearance-focused cognitive distortions (Ridolfi et al. 2011) and body appreciation. Body appreciation refers to valuing the features, functions, and health of the body (Tylka and Wood-Barcalow 2015b), including favorable opinions, acceptance, respect, and protection of the body by rejecting unrealistic body images portrayed in the media (Avalos et al. 2005).

Previous research found that body appreciation was associated with a wide range of positive indices including self-esteem (Avalos et al. 2005), adaptive coping (Lobera and Ríos 2011), optimism (Dalley and Vidal 2013) and intuitive eating—a flexible and positive eating pattern negatively related to eating disorders (Luo et al. 2019). In addition, an identified characteristic of body appreciation is “protective filtering” (Wood-Barcalow et al. 2010, p. 109), which can prevent the negative effects induced by viewing thin-idealized media (Halliwell 2013). People with high level of body appreciation are expected to buffer the negative influences of harmful appearance messages on body image by engaging in protective filtering (Andrew et al. 2015; Tylka 2011). In addition, body appreciation includes caring for the body’s needs and focusing on the body’s functions and health (Homan and Tylka 2018), suggesting that individuals who have a high level of body appreciation may take care of their body and eat based on inner hunger cues rather than adopt maladaptive eating behaviors.

Although the risk-buffer role of body appreciation has been proposed for several years, empirical research is still lacking (Tylka 2011), especially in Chinese culture. To address this gap, in the present study we investigated whether body appreciation could moderate the relationship between body image comparisons on SNS and restrained eating as well as the mediating role of body shame among Chinese college women. We hypothesized that body appreciation would moderate the associations between body image comparisons on SNS and body shame (Hypothesis 3a), between body shame and restrained eating (Hypothesis 3b), and between body image comparisons on SNS and restrained eating (Hypothesis 3c); specifically, we predicted that these associations would be attenuated among individuals with higher body appreciation.

In addition, as an index of an individual’s body size, body mass index (BMI) is another important factor influencing eating pathology in young women (Burnette et al. 2018). It has been suggested that there is a visual attentional bias to appearance-related information among individuals with higher level of BMI (Roefs et al. 2008). Specifically, there may be a pattern whereby relatively more attention is paid to others’ attractive body parts and relatively less attention is paid to one’s own attractive body parts. Therefore, we expect that people with higher level of BMI would be more likely to engage in body image comparisons (Gao et al. 2013; Glauert et al. 2010) and thereby possibly increasing their susceptibility to eating disorders (Jansen et al. 2005).

Furthermore, research has showed that individuals with higher BMI experienced more negative body image such as body dissatisfaction and related negative emotions such as distress, anxiety, and depression due to their perceived failure to meet societal ideals (Jeffers et al. 2013; Kelly et al. 2011). These higher weight individuals also received significantly more negative weight and shape-related comments (Herbozo et al. 2013; Stevens et al. 2018), which are associated with more weight and eating concerns (Herbozo et al. 2013). Based on these findings, we hypothesized that BMI would moderate the relationship between body image comparisons on SNS and restrained eating (Hypothesis 4a), as well as the relationship between body shame and restrained eating (Hypothesis 4b). Specifically, we hypothesized that these associations would be stronger among individuals with higher BMI.

The Current Study

In conclusion, drawing on social comparison, sociocultural, and objectification theories, we investigated the relationship between body image comparisons on SNS and restrained eating among Chinese college women, as well as the mediating role of body shame and the moderating roles of body appreciation and BMI. Our study not only can help to understand the impact of the use of social networking sites on individuals’ psychosocial development, but also may provide advice about how to use SNS reasonably and how to derail the occurrence of health-compromising eating behaviors for female college students. Moreover, our investigation of body appreciation will help inform future therapeutic interventions for body image disturbance and eating disorders from the perspective of positive psychology.

Method

Participants

Participants were recruited from two universities in central China through convenience sampling. A total of 838 college women participated in the present study voluntarily. In order to improve the integrity and validity of the collected questionnaires, surveys with incomplete demographic information (age, height or weight; n = 224) or in which more than 30% of the survey items were not answered (n = 1) or involved repeated, regular (Li and Liu 2006; Wang et al. 2020), or extreme responses (n = 46; the z-scores fall outside 3 standard deviations of the mean; Zhang and Xu 2009) were removed. The final usable sample was composed of 567 college women with ages ranging from 17 to 23 years-old (M = 19.97, SD = 1.37).

Procedure and Measures

Before data collection, the study was approved by the Academic Committee for Scientific Research at the university of the authors. At the beginning of the survey, all participants signed informed consent explaining the principles of their voluntarily participation (participants were informed that their responses would be anonymous and that they can withdraw this participation at any time). Then, the pencil-and-paper survey was administered in classrooms and conducted in Mandarin. During the assessment, participants provided demographic information and completed the survey instruments independently; they were encouraged to respond to each item carefully. After the assessment, questionnaires were taken back on the spot, and each participant received a small gift as reward.

Body Image Comparisons on SNS

The Chinese version of body image comparisons on SNS was adopted to measure participants’ tendency to compare their body image to others on SNS (Fardouly and Vartanian 2015; Wei et al. 2017). Participants were asked to respond on a 5-point scale from 1 (definitely disagree) to 5 (definitely agree) on each of the following three items: “When using SNS, I compare my physical appearance to that of others”; “When using SNS, I compare how I am dressed to how other users are dressed”; and “When using SNS, I compare my figure to that of others.” Responses were averaged, with higher scores indicating higher body image comparisons tendency on SNS. This scale has been successfully used with Chinese samples and was found to have good construct validity and internal consistency with a Cronbach’s alpha of .89 among adolescents (Wei et al. 2017). In the current study, the Cronbach’s alpha for the scale was .91.

Body Shame

The body shame subscale of the Chinese version (Chen 2014) of the Objectified Body Consciousness Scale (OBCS; Mckinley and Hyde 1996) was used to assess the level of shame perceived by a person when the body does not conform to cultural standards (e.g., “When I can’t control my weight, I feel like something must be wrong with me”). Participants were asked to respond on a 7-point scale (1 = definitely disagree, 7 = definitely agree) on each of the eight items. Responses across items were averaged, with higher scores indicating higher body shame. The measure has been successfully used with Chinese samples and was found to have good construct validity and internal consistency with a Cronbach’s alpha of .82 among undergraduate students (Jackson and Chen 2015; Wang et al. 2020). The Cronbach’s alpha for the subscale in the current study was .73.

Body Appreciation

The Body Appreciation Scale-2 (Tylka and Wood-Barcalow 2015a) was used to assess individuals’ acceptance of, favorable opinions toward, and respect for their bodies (e.g., “I respect my body”). Participants indicated their agreement with 10 statements on a 5-point scale from 1 (never) to 5 (always). Item responses were averaged, with higher scores indicating greater body appreciation. We conducted a Confirmatory Factor Analysis because a Chinses version of the scale was not available, although the scale has been used with Chinese female adolescents and has shown adequate internal consistency (α = .89; Luo et al. 2019). The results of the CFA showed that this one-factor measure had good fit: χ2/df = 3.29, RMSEA = .06, CFI = .99, TLI = .97, SRMR = .03. The Cronbach’s alpha for the present sample was .92.

Body Mass Index

Participants’ BMI was calculated by using the eq. BMI = weight (kg)/height (m)2 based on participants’ current height and weight as reported by them. In the present study, the BMI of participants ranged from 15.21 to 28.93 (M = 19.83, SD = 2.03). According to Chinese BMI cut-offs, 159 (28%) participants were underweight (BMI < 18.5), 396 (70%) were normal weight (18.5–24) and 12 (2%) were overweight or obese (BMI ≥ 24).

Restrained Eating

The Restrained Eating subscale of the Chinese version (Kong 2012) of the Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire (DEBQ) was used to assess restrained eating (e.g., “Do you deliberately eat less in order to not become heavier?”). Participants rated each of the 10 items on a 5-point scale from 1 (never) to 5 (very often). Item responses were averaged, with higher scores indicating a greater degree of food restriction. This scale has been used with Chinese samples and was found to have good construct validity and internal consistency with a Cronbach’s alpha of .86 among college women (Niu et al. 2020). The Cronbach’s alpha for the present study was .92.

Covariates

The present study controlled for age, year in college, and the number of friends on SNS in the statistical analyses due to the fact that these variables could impact the relationship between SNS use and body image and disordered eating outcomes (Holland and Tiggemann 2016). All these covariates were reported directly by participants.

Statistical Analyses

SPSS 23.0 was used for data analyses in the present study. Before the analyses, series mean substitution was conducted to estimate occasional missing data points from individual measures (<2% missing data for per scale). In the preliminary analyses, descriptive statistics and correlation analysis were calculated with SPSS. Then, the PROCESS macro for SPSS (Model 67) suggested by Hayes (2013) was adopted to test complex models containing mediating and moderating effects, using bootstrapping techniques with 5000 bootstrap samples to calculate confidence intervals. (An effect is significant when 0 is not included in the 95% bias-corrected confidence interval.)

Results

Preliminary Analyses

We first conducted a correlation analysis among the variables, and the means, standard deviations, and correlation coefficients for all study variables are presented in Table 1. As can be seen, body image comparisons on SNS, body shame, and restrained eating were positively correlated with each other; body appreciation was negatively correlated with body image comparisons on SNS, body shame, BMI, and restrained eating; BMI was positively correlated with body shame, body appreciation, and restrained eating. Importantly, Hypothesis 1, which predicted a positive correlation between body image comparisons and restrained eating, was supported.

Testing for the Proposed Model

Next, we used the PROCESS macro for SPSS (Model 67, which fit the hypothesized model) to test the mediating role of body shame as well as the moderating roles of body appreciation and BMI. Regression analysis held body image comparisons on SNS as the independent variable, restrained eating as the dependent variable, body shame as the mediator, and both body appreciation and BMI as moderators. The two moderators were explored independently. Specifically, we estimated the moderating effect of body appreciation in the association between body image comparisons on SNS and body shame, the association between body shame and restrained eating, as well as the association between body image comparisons on SNS and restrained eating; the moderating effect of BMI in the association between body shame and restrained eating and the association between body image comparisons on SNS and restrained eating were also examined.

As shown in Fig. 1, body image comparisons on SNS were positively associated with body shame (b = .32, p < .001) and restrained eating (b = .16, p < .001), and body shame was also positively associated with restrained eating (b = .24, p < .001). These results indicate that body shame mediated the relationship between body image comparisons on SNS and restrained eating. Therefore, Hypothesis 2 was supported.

Results of the hypothesized model in which the direct relationship between body image comparisons on SNS and restrained eating is mediated by body shame as well as moderated by BMI. Additionally, BMI and body appreciation moderated the link between body shame and restrained eating. Solid lines indicate significant pathways; dashed grey lines, nonsignificant ones. **p < .01. ***p < .001

In addition, as shown in Fig. 1, the interaction between body image comparisons on SNS and body appreciation on body shame was not significant (b = −.04, p = .55), which suggests that the relationship between body image comparisons on SNS and body shame was not moderated by body appreciation. Thus, Hypothesis 3a was not supported. The interaction between body image comparisons on SNS and body appreciation on restrained eating also was not significant (b = .04, p = .52), indicating that the relationship between body image comparisons on SNS and restrained eating was not moderated by body appreciation. Therefore, Hypothesis 3c was not supported in that high levels of body image comparisons on SNS was related to more restrained eating independent of women’s levels of body appreciation.

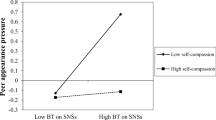

In contrast, the interaction between body shame and body appreciation on restrained eating was significant (b = −.17, p < .01), indicating that the relationship between body shame and restrained eating was moderated by body appreciation. We used simple slope tests to analyze the relationship between body shame and restrained eating separately for higher (+1 SD) and lower (−1 SD) body appreciation (see Fig. 2). For women with lower body appreciation, the relationship between body shame and restrained eating was significant (bsimple = .36, SE = .06, t = 6.29, p < .001, 95% CI [.24, .48]); for women with higher body appreciation, the relationship between body shame and restrained eating was not significant (bsimple = .12, SE = .07, t = 1.74, p = .08, 95% CI [−.02, .26]). Thus, Hypothesis 3b was supported.

Moderating effect of body appreciation on the relationship between body shame and restrained eating. For both body shame and body appreciation, low is defined as one SD below the mean and high as one SD above the mean. The solid black slope is significant (p < .05) whereas the dashed grey slope is not, indicating that higher body shame is associated with more restrained eating only among women low in body appreciation. a Body shame as a predictor b body image comparisons (BICs) on SNS as a predictor

Additionally, as Fig. 1 illustrates, the interaction between body shame and BMI on restrained eating was significant (b = −.06, p < .01), indicating that the relationship between body shame and restrained eating was moderated by BMI. The interaction between body image comparisons on SNS and BMI on restrained eating was also significant (b = .07, p < .001), showing that the relationship between body image comparisons on SNS and restrained eating was moderated by BMI. We again used simple slope tests to analyze the relationship between body shame and restrained eating as well as the relationship between body image comparisons on SNS and restrained eating separately for higher (+1 SD) and lower (−1 SD) BMI (see Fig. 3). As shown in Fig. 3a, although both slopes were significant, the relationship between body shame and restrained eating was stronger at lower BMI (bsimple = .37, SE = .07, t = 5.57, p < .001, 95% CI [.23, .51]) than at higher BMI (bsimple = .11, SE = .05, t = 2.10, p = .04, 95% CI [.01, .21]). This is contrary to the moderation’s direction of BMI in Hypothesis 4a which predicted that the association between body shame and restrained eating would be stronger among individuals with higher BMI. Therefore, Hypothesis 4a was not supported; rather, the reverse prediction was found. As shown in Fig. 3b, for women with higher BMI, the association between body image comparisons on SNS and restrained eating was significant (bsimple = .31, SE = .05, t = 5.75, p < .001, 95% CI [.21, .41]); for women with lower BMI, the association between body image comparisons on SNS and restrained eating was not significant (bsimple = .01, SE = .05, t = .24, p = .81, 95% [−.09, .11]). Thus, Hypothesis 4b was supported in that the association between higher body image comparisons on SNS and higher restrained eating held among heavier, but not thinner, women.

The moderating effect of BMI on the relationships between a body shame and b body image comparisons (BICs) on SNS with restrained eating. For both predictors and BMI, low is defined as one SD below the mean and high as one SD above the mean. Black slopes, whether solid or dashed, are significant (p < .05); the single grey dashed slope is not

Discussion

As hypothesized, we found that body image comparisons on SNS were positively associated with restrained eating and that body shame mediated this association. Similarly, as hypothesized, we found that body appreciation buffered the relationship between body shame and restrained eating. Additionally, we found the relationship between body shame and restrained eating was stronger among women with lower BMI, which is inconsistent with our hypothesis; however, the relationship between body image comparisons on SNS and restrained eating was stronger among women with higher BMI, which is consistent with our hypothesis.

First, the positive association between body image comparisons on SNS and restrained eating among Chinese college women was in line with findings of previous research in western culture (Fardouly et al. 2017). SNS is a flexible self-presentation platform where users can control how to present themselves (Krämer and Winter 2008). At the same time, because of “positive bias,” people are likely to present more attractive self-images (Wang and Ma 2019). Coupled with the widespread popularity of various beauty apps on mobiles, it is quite common to beautify and carefully select images before posting on SNS (Gioia et al. 2020; Mclean et al. 2015). These images are usually featured as unrealistically thin and flawless, and these features may reinforce social standards of female attractiveness (Mabe et al. 2014). Therefore, comparisons with these unrealistic ideals may induce social pressure, motivating women to become thin and attractive (Fox and Vendemia 2016). Restrained eating thereby is used as a means for women to lose weight or improve appearance under social pressure.

Second, the present study revealed the mediating role of body shame in the association between body image comparisons on SNS and restrained eating, indicating that body shame is a proximal factor affecting disordered eating behaviors. This is consistent with previous findings that body shame is a strong predictor of eating disturbance (Mustapic et al. 2017). This finding also suggests that body image comparisons on SNS are closely correlated with body shame. According to social comparison theory, body image comparisons provide information for women to evaluate their physical appearance (Festinger 1954). Meanwhile, as we mentioned earlier, the ideal images posted on SNS further reinforce the social standard of women’s body image (Mabe et al. 2014). Therefore, comparing with the unrealistic images on SNS may not only induce negative evaluation of one’s own body (Perloff 2014), but also cause women to feel that they fail to meet the social standard. These can lead to negative body image and feelings about self, that is, body shame (Monks et al. 2020), which then leads to disordered eating, including restrained eating (Davies et al. 2020).

Third, our results partially revealed the moderating role of body appreciation in that body appreciation only moderated the association between body shame and restrained eating. Specifically, the relationship between body shame and restrained eating was stronger among women with lower body appreciation and not significant among women with higher body appreciation. Namely, body appreciation played a buffering role in the relationship between body shame and restrained eating. This buffering role may be explained by two possible reasons. On the one hand, women with a positive body image may pay more attention to their bodies’ functionality and health. They do not base their self-worth on appearance and are not preoccupied with appearance-fixing behaviors (Tylka and Wood-Barcalow 2015b). Thus, women with higher body appreciation may be more likely to engage in self-care behaviors, such as moderate exercise, adaptive stress-release (jogging, journaling), and eating based on inner hunger cues (Wood-Barcalow et al. 2010), rather than maladaptive behaviors (e.g., restrained eating), even when experiencing body shame. On the other hand, the gratitude model of body appreciation acknowledges that body appreciation can be essentially thought as a form of gratitude which can recognize and amplify the good in one’s body (Homan and Tylka 2018). It thereby makes individuals focus on positive internal characteristics and loosen concerns with outward appearance or the approval of other people (Homan and Tylka 2018). As a result, women with high body appreciation are less likely to seek conformity to ideal body image standards and thus less likely to engage in restrained eating behavior.

Furthermore, our results found that body appreciation failed to moderate the relationship between body image comparisons on SNS and body shame as well as the relationship between body image comparisons on SNS and restrained eating. The reasons may be as follows. On the one hand, internet information is archived. When browsing SNS, individuals can repeatedly view the “attractive” images of other users, which makes the “threat” brought by the ideals on SNS repetitive and continuous (Lian et al. 2017). In other words, the outcomes brought by body image comparisons on SNS can be strong. On the other hand, it may also indicate that women with high body appreciation are aware of the unreality of the ideals in media and are less inclined to compare their bodies with others (Andrew et al. 2015; Halliwell 2013). Therefore, the buffering role of body appreciation on the associations between body image comparisons on SNS and body shame, restrained eating was disappeared.

Finally, BMI was found to moderate the relationship between body shame and restrained eating as well as the relationship between body image comparisons on SNS and restrained eating. Notably, contrary to our hypothesis, the association between body shame and restrained eating was stronger among women with lower BMI and weaker among women with higher BMI. One possible reason may be that because women with higher BMI usually have a more negative body image (Mintem et al. 2015), they may be less sensitive to body shame. Therefore, for women with higher BMI, the relationship between body shame and its harmful consequences was weaker. In contrast, women with lower BMI may be more sensitive to body-relevant negative feelings and more vulnerable to its negative consequences. In addition, underweight women with low BMI were found to have lower ideal weight and ideal BMI (Ohara et al. 2014). Therefore, for women with lower BMI, the relationship between body shame and restrained eating was stronger.

In addition, consistent with our hypothesis, the association between body image comparisons on SNS and restrained eating was stronger among women with higher BMI. Studies have shown that there is attentional bias with increasing BMI (within the normal range), that is, people with higher BMI attended relatively more to their self-identified most unattractive body part as well as others’ most attractive body parts (Roefs et al. 2008). This focus may contribute to body image comparisons and their outcomes (e.g., disordered eating). Furthermore, relevant empirical studies found that weight misperception is common among female adolescents in Eastern and Western countries (Fan et al. 2014; Mase et al. 2013). Notably, normal-weight young women are more likely to have faulty perceptions of being overweight (Lo et al. 2011; Wang et al. 2018) so that they then are more susceptible to experiencing potentially harmful eating behavior (Robinson et al. 2018). One point to note in the present study is that the weight of women with higher BMI was still within the normal range. As a result, due to overweight misperception, they may be at a heightened risk of weight-loss via restrained eating after comparing with the thinner ideals on SNS.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

The current study should be considered in the light of several limitations. First, our data were cross-sectional so that we cannot draw causal conclusions. In the future, longitudinal or experimental studies should be designed to further investigate causality. Second, the participants in our study were largely thin and normal-weight women, with too few overweight or obese women. This limitation reminds us to be more cautious when drawing and extending conclusions of our study, especially when it comes to the moderating role of BMI. Future studies can investigate more overweight or obese women for a more complete exploration. Additionally, the questionnaire of body image comparisons on SNS used in our study did not clearly indicate the direction of comparison (upward comparison). In future studies, it may be possible to design a questionnaire that can distinguish the direction of body image comparisons on SNS to comprehensively investigate the effect of body image comparisons on SNS.

Practice Implications

The present study constructed a mixed model with body shame as a mediator, and body appreciation and BMI as moderators, to clarify the association between body image comparisons on SNS and restrained eating. The findings can help to understand the complicated effect of SNS use on negative body image and disordered eating. Significant practical implications can also be obtained from the research results. First, it is of great importance to guide college women to use new media like SNS reasonably and appropriately. Because social comparison is spontaneous and unintentional (Gilbert et al. 1995), it may be difficult for people to control the impulse to compare with others. However, educators can tell college women the secrets behind body image comparisons on SNS. For example, much information presented on SNS is likely to be selected and beautified, and those slim and beautiful images to which we compared ourselves are probably taken through BeautyCam (a widely used application for enhancing photos). Moreover, our study indicates that body appreciation can buffer the relationship between body shame and restrained eating. Intervention measures may focus on cultivating individuals’ body appreciation to prevent disordered eating. For instance, society and educators can encourage college women to pay attention to their internal qualities rather than their external characteristics such as appearance and weight.

Conclusions

The present study revealed the positive relationship between body image comparisons on SNS and restrained eating among Chinese college women, as well as the mediating role of body shame in this association. The findings indicate that body shame is of great value for explaining the relationship between body image comparisons on SNS and restrained eating. The findings also revealed that body appreciation can buffer the relationship between body shame and restrained eating, which has some implications for prevention interventions. Furthermore, the moderating effect of BMI indicated that both thinner and heavier (within a normal weight range) young women are vulnerable to developing restrained eating, but through different mechanisms.

References

Andrew, R., Tiggemann, M., & Clark, L. (2015). The protective role of body appreciation against media-induced body dissatisfaction. Body Image, 15, 98–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2015.07.005.

Avalos, L., Tylka, T. L., & Wood-Barcalow, N. (2005). The body appreciation scale: Development and psychometric evaluation. Body Image, 2(3), 285–297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2005.06.002.

Bissell, K., & Rask, A. (2010). Real women on real beauty: Self-discrepancy, internalisation of the thin ideal, and perceptions of attractiveness and thinness in Dove’s campaign for real beauty. International Journal of Advertising, 29(4), 643–668. https://doi.org/10.2501/s0265048710201385.

Burnette, C. B., Simpson, C. C., & Mazzeo, S. E. (2018). Relation of BMI and weight suppression to eating pathology in undergraduates. Eating Behaviors, 30, 16–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2018.05.003.

Chen, G. Q. (2014). Analysis and research on the influence factors of objectification on sports participation. Master’s thesis, Guangxi University for Nationalities (In Chinese).

China Internet Network Information Center. (2019). The 42th China statistical report on Internet development. Retrieved from http://cnnic.cn/gywm/xwzx/rdxw/20172017_7056/201902/W020190228474508417254.pdf (In Chinese).

Cohen, R., Newton-John, T., & Slater, A. (2017). The relationship between Facebook, and Instagram appearance-focused activities and body image concerns in young women. Body Image, 23, 183–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2017.10.002.

Dalley, S. E., & Vidal, J. (2013). Optimism and positive body image in women: The mediating role of the feared fat self. Personality and Individual Differences, 55(5), 465–468. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2013.04.006.

Davies, A. E., Burnette, C. B. & Mazzeo, S. E. (2020). Testing a moderated mediation model of objectification theory among black women in the United States: The role of protective factors. Sex Roles. Advanced online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-020-01151-z.

Duarte, C., Pinto-Gouveia, J., Ferreira, C., & Batista, D. (2015). Body image as a source of shame: A new measure for the assessment of the multifaceted nature of body image shame. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 22(6), 656–666. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.1925.

Fan, M., Jin, Y., & Khubchandani, J. (2014). Overweight misperception among adolescents in the United States. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 29(6), 536–546. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2014.07.009.

Fardouly, J., & Vartanian, L. R. (2015). Negative comparisons about one’s appearance mediate the relationship between Facebook usage and body image concerns. Body Image, 12, 82–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2014.10.004.

Fardouly, J., & Vartanian, L. R. (2016). Social media and body image concerns: Current research and future directions. Current Opinion in Psychology, 9, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.09.005.

Fardouly, J., Diedrichs, P. C., Vartanian, L. R., & Halliwell, E. (2015). Social comparisons on social media: The impact of Facebook on young women's body image concerns and mood. Body Image, 13, 38–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2014.12.002.

Fardouly, J., Pinkus, R. T., & Vartanian, L. R. (2017). The impact of appearance comparisons made through social media, traditional media, and in person in women’s everyday lives. Body Image, 20, 31–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2016.11.002.

Feltman, C. E., & Szymanski, D. M. (2018). Instagram use and self-objectification: The roles of internalization, comparison, appearance commentary, and feminism. Sex Roles, 78, 311–324. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-017-0796-1.

Ferreira, C., Trindade, I. A., & Martinho, A. (2016). Explaining rigid dieting in normal-weight women: The key role of body image inflexibility. Eating and Weight Disorders, 21(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-015-0188-x.

Festinger, L. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations, 7(7), 117–140. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872675400700202.

Fox, J., & Vendemia, M. A. (2016). Selective self-presentation and social comparison through photographs on social networking sites. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 19(10), 593–600. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2016.0248.

Fredrickson, B. L., & Roberts, T. A. (1997). Objectification theory: Toward understanding women’s lived experiences and mental health risks. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21(2), 173–206. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997.tb00108.x.

Gao, X., Li, X., Yang, X., Wang, Y., Jackson, T., & Chen, H. (2013). I can’t stop looking at them: Interactive effects of body mass index and weight dissatisfaction on attention towards body shape photographs. Body Image, 10(2), 191–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2012.12.005.

Gilbert, D. T., Giesler, R. B., & Morris, K. A. (1995). When comparisons arise. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(2), 227–236. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.69.2.227.

Gioia, F., Griffiths, M. D., & Boursier, V. (2020). Adolescents’ body shame and social networking sites: The mediating effect of body image control in photos. Sex Roles. Advanced online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-020-01142-0.

Glauert, R., Rhodes, G., Fink, B., & Grammer, K. (2010). Body dissatisfaction and attentional bias to thin bodies. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 43(1), 42–49. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20663.

Haferkamp, N., & Krämer, N. C. (2011). Social comparison 2.0: Examining the effects of online profiles on social-networking sites. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 14(5), 309–314. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2010.0120.

Halliwell, E. (2013). The impact of thin idealized media images on body satisfaction: Does body appreciation protect women from negative effects? Body Image, 10(4), 509–514. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2013.07.004.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). PROCESS: a versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling [White paper]. Retrieved from http://www.afhayes.com/public/process2012.pdf.

Herbozo, S., Menzel, J. E., & Thompson, J. K. (2013). Differences in appearance-related commentary, body dissatisfaction, and eating disturbance among college women of varying weight groups. Eating Behaviors, 14(2), 204–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2013.01.013.

Holland, G., & Tiggemann, M. (2016). A systematic review of the impact of the use of social networking sites on body image and disordered eating outcomes. Body Image, 17, 100–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2016.02.008.

Homan, K. J., & Tylka, T. L. (2018). Development and exploration of the gratitude model of body appreciation in women. Body Image, 25, 14–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2018.01.008.

Jackson, T., & Chen, H. (2015). Features of objectified body consciousness and sociocultural perspectives as risk factors for disordered eating among late-adolescent women and men. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 62(4), 741–752. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000096.

Jansen, A., Nederkoorn, C., & Mulkens, S. (2005). Selective visual attention for ugly and beautiful body parts in eating disorders. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 43(2), 183–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2004.01.003.

Jeffers, A. J., Cotter, E. W., Snipes, D. J., & Benotsch, E. G. (2013). BMI and depressive symptoms: The role of media pressures. Eating Behaviors, 14(4), 468–471. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2013.08.007.

Kelly, S. J., Daniel, M., Dal Grande, E., & Taylor, A. (2011). Mental ill-health across the continuum of body mass index. BMC Public Health, 11(1), 765–775. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-765.

Kim, J. W., & Chock, T. M. (2015). Body image 2.0: Associations between social grooming on Facebook and body image concerns. Computers in Human Behavior, 48, 331–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.01.009.

Kong, F. C. (2012). The neural mechanisms in attentional bias on food cues for restraint eaters. Doctoral dissertation, Southwest University (In Chinese).

Krämer, N. C., & Winter, S. (2008). Impression management 2.0: The relationship of self-esteem, extraversion, self-efficacy, and self-presentation within social networking sites. Journal of Media Psychology, 20(3), 106–116. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-1105.20.3.106.

Li, Y., & Liu, H. S. (2006). Common problems and solutions in questionnaire survey. Educational Research and Experiment, 2, 61–64 http://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTotal-YJSY200602014.htm (In Chinese).

Lian, S. L., Sun, X. J., Niu, G. F., & Zhou, Z. K. (2017). Upward social comparison on SNS and depression: A moderated mediation model and gender difference. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 49(7), 941–952. https://doi.org/10.3724/SP.J.1041.2017.00941 (In Chinese).

Lo, W. S., Ho, S. Y., Mak, K. K., Lai, H. K., Lai, Y. K., & Lam, T. H. (2011). Weight misperception and psychosocial health in normal weight Chinese adolescents. International Journal of Pediatric Obesity, 6, 381–389. https://doi.org/10.3109/17477166.2010.514342.

Lobera, I. J., & Ríos, P. B. (2011). Spanish version of the body appreciation scale (BAS) for adolescents. Spanish Journal of Psychology, 14(1), 411–420. https://doi.org/10.5209/rev_SJOP.2011.v14.n1.37.

Luo, Y. J., Niu, G. F., Kong, F. C., & Chen, H. (2019). Online interpersonal sexual objectification experiences and Chinese adolescent girls' intuitive eating: The role of broad conceptualization of beauty and body appreciation. Eating Behaviors, 33, 55–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2019.03.004.

Mabe, A. G., Forney, K. J., & Keel, P. K. (2014). Do you “like” my photo? Facebook use maintains eating disorder risk. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 47(5), 516–523. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22254.

Mase, T., Miyawaki, C., Kouda, K., Fujita, Y., Ohara, K., & Nakamura, H. (2013). Relationship of a desire of thinness and eating behavior among Japanese underweight female students. Eating and Weight Disorders, 18(2), 125–132. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-013-0019-x.

McKinley, N. M., & Hyde, J. S. (1996). The objectified body consciousness scale: Development and validation. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 20(2), 181–215. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1996.tb00467.x.

Mclean, S. A., Paxton, S. J., & Wertheim, E. H. (2016). The role of media literacy in body dissatisfaction and disordered eating: A systematic review. Body Image, 19, 9–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2016.08.002.

Mclean, S. A., Paxton, S. J., Wertheim, E. H., & Masters, J. (2015). Photoshopping the selfie: Self photo editing and photo investment are associated with body dissatisfaction in adolescent girls. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 48(8), 1132–1140. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22449.

Mintem, G. C., Gigante, D. P., & Horta, B. L. (2015). Change in body weight and body image in young adults: A longitudinal study. BMC Public Health, 15(1), 222–228. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-1579-7.

Monks, H., Costello, L., Dare, J.& Boyd, E. R. (2020). “We’re continually comparing ourselves to something”: Navigating body image, media, and social media ideals at the nexus of appearance, health, and wellness. Sex Roles. Advanced online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-020-01162-w.

Morgan, M., et al. (2015). Facebook use and disordered eating in college-aged women. Journal of Adolescent Health, 57(2), 157–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.04.026.

Mustapic, J., Marcinko, D., & Vargek, P. (2017). Body shame and disordered eating in adolescents. Current Psychology, 36(3), 447–452. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-016-9433-3.

Niu, G., Sun, L., Liu, Q., Chai, H., Sun, X., & Zhou, Z. (2020). Selfie-posting and young adult women's restrained eating: The role of commentary on appearance and self-objectification. Sex Roles, 82(3), 232–240. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-019-01045-9.

Noll, S. M., & Fredrickson, B. L. (2010). A mediational model linking self-objectification, body shame, and disordered eating. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 22(4), 623–636. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1998.tb00181.x.

Ohara, K., Kato, Y., Mase, T., Kouda, K., Miyawaki, C., Fujita, Y., … Nakamura, H. (2014). Eating behavior and perception of body shape in Japanese university students. Eating and Weight Disorders, 19, 461–468. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-014-0130-7.

Perloff, R. M. (2014). Social media effects on young women’s body image concerns: Theoretical perspectives and an agenda for research. Sex Roles, 71(11–12), 363–377. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-014-0384-6.

Pew Research Center. (2019). Share of U.S. adults using social media, including Facebook, is mostly unchanged since 2018. Retrieved from https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/04/10/share-of-u-s-adults-using-social-media-including-facebook-is-mostly-unchanged-since-2018/.

Ridolfi, D. R., Myers, T. A., Crowther, J. H., & Ciesla, J. A. (2011). Do appearance focused cognitive distortions moderate the relationship between social comparisons to peers and media images and body image disturbance? Sex Roles, 65(7–8), 491–505. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-011-9961-0.

Robinson, E., Sutin, A. R., & Daly, M. (2018). Self-perceived overweight, weight loss attempts, and weight gain: Evidence from two large, longitudinal cohorts. Health Psychology, 37(10), 940–947. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000659.

Rodgers, R. F., & Melioli, T. (2016). The relationship between body image concerns, eating disorders and internet use, part I: A review of empirical support. Adolescent Research Review, 1(2), 95–119. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-015-0016-6.

Rodgers, R. F., McLean, S. A., & Paxton, S. J. (2015). Longitudinal relationships among internalization of the media ideal, peer social comparison, and body dissatisfaction: Implications for the tripartite influence model. Developmental Psychology, 51(5), 706–713. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000013.

Roefs, A., Jansen, A., Moresi, S., Willems, P., van Grootel, S., & van der Borgh, A. (2008). Looking good. BMI, attractiveness bias and visual attention. Appetite, 51(3), 552–555. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2008.04.008.

Santos, I., Sniehotta, F. F., Marques, M. M., Carraa, E. V., & Teixeira, P. J. (2017). Prevalence of personal weight control attempts in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obesity Reviews, 18(1), 32–50. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12466.

Stevens, S. D., Herbozo, S., & Martinez, S. N. (2018). Weight stigma, depression, and negative appearance commentary: Exploring BMI as a moderator. Stigma and Health, 3(2), 108–115. https://doi.org/10.1037/sah0000081.

Tiggemann, M. (2011). Sociocultural perspectives on human appearance and body image. In T. F. Cash & L. Smolak (Eds.), Body image: A handbook of science, practice, and prevention (pp. 12–19). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Tylka, T. L. (2011). Positive psychology perspectives on body image. In T. F. Cash & L. Smolak (Eds.), Body image: A handbook of science, practice, and prevention (pp. 56–64). New York: Guilford Press.

Tylka, T. L., & Sabik, N. J. (2010). Integrating social comparison theory and self-esteem within objectification theory to predict women’s disordered eating. Sex Roles, 63(1–2), 18–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-010-9785-3.

Tylka, T. L., & Subich, L. M. (2004). Examining a multidimensional model of eating disorder symptomatology among college women. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 51(3), 314–328. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.51.3.314.

Tylka, T. L., & Wood-Barcalow, N. L. (2015a). The body appreciation Scale-2: Item refinement and psychometric evaluation. Body Image, 12, 53–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2014.09.006.

Tylka, T. L., & Wood-Barcalow, N. L. (2015b). What is and what is not positive body image? Conceptual foundations and construct definition. Body Image, 14, 118–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2015.04.001.

Valkenburg, P. M., & Peter, J. (2013). The differential susceptibility to media effects model. Journal of Communication, 63(2), 221–243. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12024.

Venus, J. S., Ehri, R., & Aziz, M. (2018). Dieting 2.0!: Moderating effects of Instagrammers' body image and Instafame on other Instagrammers' dieting intention. Computers in Human Behavior, 87, 224–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.06.001.

Wade, T. D., Wilksch, S. M., & Lee, C. (2012). A longitudinal investigation of the impact of disordered eating on young women’s quality of life. Health Psychology, 31(3), 352–359. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025956.

Wang, S. Z, & Ma, H. Y. (2019). Positive bias in social networking site from the view of motivation. Journal of Huazhong University of Science and Technology (SheHui Kexueban), 33(03), 127-138. https://doi.org/10.19648/j.cnki.jhustss1980.2019.03.15 (In Chinese).

Wang, X. Y., Qi, Q. R., Lu, X. C., & Sun, S. X. (2015). Perception of obesity and weight reduction behaviors among undergraduates. Chinese Journal of School Health, 36(1), 54–60. https://doi.org/10.16835/j.cnki.1000-9817.2015.01.016 (In Chinese).

Wang, Y., Liu, H. J., Wu, F. Y., Yang, X. D., Yue, M. J., Pang, Y. X., … Zhang, X. M. (2018). The association between BMI and body weight perception among children and adolescents in Jilin City, China. PLoS One, 13(3), e0194237. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0194237.

Wang, Y., Wang, X., Yang, J., Zeng, P., & Lei, L. (2020). Body talk on social networking sites, body surveillance, and body shame among young adults: The roles of self-compassion and gender. Sex Roles, 6, 731–742. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-019-01084-2.

Wei, Q., Sun, X. J., Lian, S. L., & Song, Y. H. (2017). The effect of using social networking sites on body image satisfaction: The mediating role of body image comparison and the moderating role of self-objectification. Journal of Psychological Science, 40(4), 920–926. https://doi.org/10.16719/j.cnki.1671-6981.20170422 (In Chinese).

Wood-Barcalow, N. L., Tylka, T. L., & Augustus-Horvath, C. L. (2010). “But I like my body”: Positive body image characteristics and a holistic model for young-adult women. Body Image, 7(2), 106–116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2010.01.001.

Xing, S. F., & Yu, G. L. (2005). A review on research of social comparison. Advances in Psychological Science, 13(1), 78–84. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1671-3710.2005.01.012 (In Chinese).

Zhang, H. C., & Xu, J. P. (2009). Modern psychology and educational statistics (3rd ed.). Beijing: Normal University Press (In Chinese).

Acknowledgements

Gengfeng Niu and Xiaojun Sun should be listed as co-corresponding authors; E-mail addresses: niugf123@163.com (G. Niu); sunxiaojun@mail.ccnu.edu.cn (X. Sun).

Author Contributions Statement

Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing - Original Draft: Liangshuang Yao; Writing – Review and Editing: Gengfeng Niu; Conceptualization, Editing and Supervision: Xiaojun Sun.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Funds of China [Project No. 31872781], Fok Ying Tung Education Foundation [No. 161075], MOE (Ministry of Education in China) Project of Humanities and Social Sciences [No.19YJC190019], Collaborative Innovation Center of Assessment toward Basic Education Quality at Beijing Normal University [No. 2020–04-012-BZPK01; 2020-04-013-BZPK01)] and Graduate Education Innovation Funding at Central China Normal University [No. 2019CXZZ115]. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

All ethical guidelines for human subjects’ research were followed.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 23 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yao, L., Niu, G. & Sun, X. Body Image Comparisons on Social Networking Sites and Chinese Female College Students’ Restrained Eating: The Roles of Body Shame, Body Appreciation, and Body Mass Index. Sex Roles 84, 465–476 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-020-01179-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-020-01179-1