Abstract

This study examined experiences of external and internalized heterosexism and sexism and their links to coping styles and psychological distress among 473 sexual minority women. Using an online sample of United States lesbian and bisexual women, the findings indicated that many participants experienced heterosexist and sexist events at least once during the past 6 months, and a number of participants indicated some level of internalized oppression. Supporting an additive multiple oppression perspective, the results revealed that when examined concurrently heterosexist events, sexist events, internalized heterosexism, and internalized sexism were unique predictors of psychological distress. In addition, suppressive coping and reactive coping, considered to be maladaptive coping strategies, mediated the external heterosexism-distress, internalized heterosexism-distress, and internalized sexism-distress links but did not mediate the external sexism-distress link. Reflective coping, considered to be an adaptive coping strategy, did not mediate the relations between external and internalized heterosexism and sexism and psychological distress. Finally, the variables in the model accounted for 54 % of the variance in psychological distress scores. These findings suggest that maladaptive but not adaptive coping strategies help explain the relationship between various oppressive experiences and psychological distress.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Feminist and gender researchers have a long history of being interested in women’s experiences of oppression, both external and internalized, and how they may negatively influence women’s lives and their psychological and physical health both in the United States as well as around the world (American Psychological Association 2007). However, the majority of this research has focused on the experiences of sexism among heterosexual women (for a review, see Szymanski and Moffitt 2012). More recently, feminist and gender scholars have given increased attention to recognizing the diversity of women and their experiences (American Psychological Association 2007). As such, a small but growing body of research has begun to explore the experiences of sexual minority women within the scholarship on gender issues (c.f., Galupo 2007; Horne and Biss 2009; Lehavot et al. 2012; Szymanski 2004, 2006).

Sexual minority women often consist of those women who self-identify as lesbian, bisexual, questioning/unsure, or queer and experience romantic attractions to other women (American Psychological Association 2004; Diamond 2005). Research suggests that it is often difficult to cleanly differentiate among these sexual minority women subgroups because women’s sexual attractions, identity, and behavior are often fluid, nonexclusive, and variable (Diamond 2005, 2008). For example, Diamond’s (2005) longitudinal study found that a significant proportion of United States sexual minority women alternated between lesbian and non-lesbian labels and experienced fluctuations in their levels of attraction to other women over an 8-year period (Diamond 2005, 2008). Furthermore, research reveals that the relationships between dimensions of sexual minority identity and psychosocial health do not differ for lesbians and bisexual women (Balsam and Mohr 2007). Thus, in this study we focus on the experiences of sexual minority women living in the United States and all studies cited use United States samples unless otherwise noted.

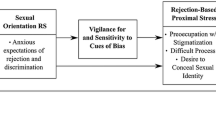

Feminist and gender scholars have also acknowledged the need to attend to women’s experiences of external and internalized sexism within the context of women’s various minority group memberships (American Psychological Association 2007). As such, empirical research is needed exploring sexual minority women’s experiences of both external and internalized heterosexism and sexism and their psychosocial correlates, as well as the potential additive influences of these multiple oppressions on their lives and mental health. Research on sexual minority women’s experiences of the cumulative, interactive, and intersectional influences of multiple oppressions is important as it may be an explanatory factor in the higher rates of psychological distress found among sexual minority women when compared to heterosexual women (Almeida et al. 2009; Cochran 2001; Meyer 2003), and in the higher rates of lifetime post-traumatic stress disorder diagnoses found among sexual minority women when compared to sexual minority men (D’Augelli et al. 2006). Furthermore, investigations are needed exploring the ways in which these multiple oppressions experienced by sexual minority women “get under the skin” (p. 707) to influence their psychosocial outcomes (Hatzenbuehler 2009). That is, what are the inter- and intra-personal psychological processes (e.g., coping, rumination, social isolation, hopelessness, negative self-schemas) through which external and internalized heterosexism and sexism may lead to poorer mental health (Hatzenbuehler 2009)? A better understanding of the mediators of the oppression-psychological distress links is needed to identify effective ways to reduce the negative effects of oppression on sexual minority women’s psychological distress and improve well-being.

Thus, the purpose of our study was to take an additive approach to the study of multiple oppressions by examining external and internalized heterosexism and sexism concurrently as predictors of psychological distress among sexual minority women. In addition, we examined coping styles as potential mediators in the links between these multiple forms of oppression and psychological distress.

External and Internalized Heterosexism

Research on external heterosexism has found that it is a prevalent experience for many lesbian, gay, and bisexual persons. For example, using a large scale national probability sample, Herek (2009) found that approximately 50 % of lesbian, gay, and bisexual persons had experienced sexual orientation-based verbal harassment, 25 % had been victims of an actual or attempted sexual orientation–based hate crime or attempted hate crime, such as physical assault, sexual assault, robbery, or vandalism, and more than 10 % reported having experienced sexual orientation-based housing or employment discrimination. Similarly, Mays and Cochran’s (2001) population based study revealed that lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults reported more discrimination and victimization experiences than their heterosexual peers. In addition, they found pervasive anti-gay discrimination with more than 50 % of lesbian, gay, and bisexual participants reporting lifetime experiences of sexual orientation-based discrimination, such as being hassled by the police, being denied or given inferior services, being fired from a job, and being prevented from renting or buying a home. In addition to external forms of heterosexism, some sexual minority women also experience internalized heterosexism, defined as the internalization by sexual minority women of negative and limiting attitudes about homosexuality that are prevalent in society (Szymanski et al. 2008a).

In terms of psychosocial correlates of heterosexism, research has consistently demonstrated that experiences of external and internalized heterosexism are related to lesbian, gay, and bisexual persons’ psychosocial distress, including lower self-esteem, less social support, loneliness, depression, suicidal ideation, substance use, anxiety, depression, global psychological distress, and post traumatic stress symptoms (for reviews, see Szymanski et al. 2008b; Szymanski and Moffitt 2012). However, most researchers examining the links between heterosexism and mental health lump sexual minority women and men together, and have taken a primary oppression perspective by examining only one form of oppression (e.g., heterosexism) as it relates to mental health outcomes (Szymanski et al. 2008a, b).

External and Internalized Sexism

Research has consistently documented that sexism is alive and well. For example, using an undergraduate sample, Fischer and Bolton Holtz (2010) found that 94 % of women reported having been forced to listen to sexist or sexually degrading jokes, 87 % reported experiencing inappropriate sexual advances, and 86 % had been called sexist names at least once in the past year. Relatedly Swim et al. (2001) found that the average college woman reported one to two sexist experiences per week over the course of a semester. However, the majority of this research has focused on the lives of heterosexual women, rendering the invisibility of sexism in the lives of sexual minority women. Only a handful of studies have examined the frequency of sexism in the lives of sexual minority women, and these studies have focused on relatively acute stressors. For example, Balsam et al. (2005) found that almost twice as many lesbian (15.5 %) and bisexual (16.9 %) women reported an experience of rape in adulthood than heterosexual women (7.9 %) with the majority of perpetrators being men. Furthermore, many women also experience internalized sexism (IS), defined as the internalization of negative and limiting attitudes about women that are prevalent in society (Downing and Roush 1985; Piggot 2004).

Research on psychosocial correlates of sexism has consistently demonstrated that experiences of external and internalized sexism are related to women’s distress, including lower self-esteem, less social support, anxiety, depression, global psychological distress, and post traumatic stress symptoms (for a review, see Szymanski and Moffitt 2012). However, most research examining the links between sexism and mental health has focused on heterosexual women and has taken a primary oppression perspective by examining only one form of oppression (e.g., sexism) as it relates to mental health outcomes (Szymanski and Moffitt 2012). Thus, research on correlates of heterosexism and sexism has primarily examined each of these forms of oppression separately rather than concurrently, although a handful of studies have begun to examine the latter among sexual minority women and will be discussed below.

Multiple Oppressions

Although the aforementioned research on heterosexism among lesbian, gay, and bisexual persons and sexism among women are important, they are limited by ignoring the complexity that comes from examining multiple sources of oppressions that sexual minority women may experience. Scholars have recently begun to shift away from the primary oppression perspective that dominated the past decade by using multiple oppression perspectives. Three such multicultural-feminist perspectives have been advanced in the literature: additive, interactionist, and intersectionality (Szymanski et al. 2008a; Szymanski and Moffitt 2012). It is important to note that although these three perspectives have nuanced distinctions among them they do not contradict each other and each offers potential value as well as limitations and challenges. In addition, each of these perspectives is likely to add unique insights into the ways in which multiple oppressions are experienced and influence the lives and psychosocial health of sexual minority women (Cole 2009; Szymanski and Moffitt 2012).

Additive Models

Additive multiple oppression perspectives postulate that socio-cultural identities act separately from each other and can be added together to form experience (Warner 2008). From this approach, for each minority identity there is simply an accumulation of disadvantage, such that a sexual minority woman is doubly disadvantaged compared to a sexual minority man or a heterosexual woman (Shields 2008). Supporting this notion, Nelson and Probst (2004) found that the more minority identities an individual claimed, the more likely s/he reported experiences of discrimination and harassment. Theorists of this approach posit that each individual oppression experienced by a person with more than one minority identity (e.g., heterosexism and sexism for sexual minority women) is important and has direct effects that additively and uniquely combine to negatively influence mental health outcomes (Szymanski et al. 2008a; Szymanski and Moffitt 2012).

Several studies of sexual minority women have found support for this perspective. Szymanski and Owens (2009) found that when examined concurrently both heterosexist events and sexist events were unique and additive predictors of psychological distress among sexual minority women. Piggot (2004) with a cross-cultural sample of 803 sexual minority women from 20 countries and Szymanski and Kashubeck-West (2008) found that both internalized heterosexism and internalized sexism (i.e., devaluing of women, distrust of women, and gender bias in favor of men) were unique predictors of self-esteem and depression, and psychological distress, respectively. However, these three studies are limited by examining either external forms of oppression or internalized forms of oppression, but not both concurrently.

Szymanski (2005) found that sexual orientation-based hate crime victimization, sexist discrimination, and internalized heterosexism (but not internalized sexism) were unique predictors of psychological distress. However, the conceptualization and measurement of internalized sexism used in her study (i.e., an unawareness of sexism and passive acceptance of traditional gender roles; Fischer et al.’s 2000) has been critiqued as having limited applicability and questionable validity for sexual minority women (c.f. Szymanski and Chung 2003). In addition, this study was limited by a narrow focus on hate crime victimization and does not account for a broader range of heterosexist events (i.e., sexual orientation-based rejection, harassment, and discrimination).

Taken together, the findings from this extremely small number of studies support the additive multiple oppression perspective and suggest that diverse sources of oppression for individuals with multiple minority statuses can contribute to psychological difficulties. We extend the current literature by using measures that capture broader experiences of external heterosexism and by considering multiple coping styles as mediators.

Interactionist Models

Interactionist multiple oppression perspectives build on the additive perspective by positing an additional principle, the multiplicative effects of multiple oppressions on individual lives. Thus, in addition to direct effects on mental health, one form of oppression (e.g., heterosexism) may interact with another form of oppression (e.g., sexism) experienced by a person with more than one minority status (e.g., sexual minority women) to influence mental health outcomes (Landrine et al. 1995; Moradi and Subich 2003). While interactionist theorists recognize that sexual minority women share some commonalities with sexual minority men and heterosexual women, they also recognize sexual minority women’s unique experiences based on the interactions of sexual orientation and gender and heterosexism and sexism (Bowleg 2008). Thus, socio-cultural identities such as sexual orientation and gender, along with their corresponding oppressions, can interact to form qualitatively different meanings and experiences that cannot be explained by each alone (Warner 2008). However, studies examining interactions between different forms of oppression among sexual minority women (Szymanski and Kashubeck-West 2008; Szymanski and Owens 2008), sexual minority persons of color (Szymanski and Gupta 2009a, b; Szymanski and Meyer 2008), and African American women (Buchanan and Fitzgerald 2008; Moradi and Subich 2003; Szymanski and Stewart 2010), have largely not supported this perspective in predicting psychological distress levels.

Intersectionality Models

Finally, intersectionality multiple oppression perspectives postulate that a new and unique experience is created from the synthesis of various components of identity and oppression (e.g., the concept of gendered heterosexism) and that these unique experiences can negatively influence mental health outcomes (Cole 2009; Collins 1991; Szymanski and Moffitt 2012). However, quantitative approaches to intersectionality theory have been stunted by a lack of quality measures to assess the constructs, and most of the empirical research that does exist focuses on the experiences of external and internalized gendered racism among African American women (c.f., King 2003; Klevens 2008; Thomas et al. 2004; 2008; Woods et al. 2008). Thus, in our study we take an additive multiple oppression perspective.

Coping Styles as Mediators

In addition to personal experiences of heterosexism and sexism, a sexual minority woman’s general coping styles are also likely to influence her psychological distress. Three coping styles that sexual minority women may use to deal with life’s stressors that may be important in the oppression-distress links are reflective, suppressive, and reactive coping styles (Heppner et al. 1995). Sexual minority women using reflective coping styles tend to approach life’s stressors and problems by examining causal relationships, being systematic, planning, and engaging in behaviors that are intended to produce changes in the external situation, affective states, or cognitive processes. They tend to use coping activities that promote progress in resolving challenging life events (Heppner et al. 1995; Wei et al. 2010). Sexual minority women who use suppressive coping styles tend to approach problems with avoidance and denial; whereas, sexual minority women who use reactive coping styles tend to approach life’s challenges with strong emotional responses, impulsivity, cognitive confusion, and distortion (Heppner et al. 1995). Sexual minority women who use suppressive or reactive coping styles tend to use coping activities that prevent or hinder the resolution of stressful live events (Heppner et al. 1995; Wei et al. 2010). They tend to see themselves as ineffective problem solvers and are less trusting of others (Heppner and Lee 2002). Thus, reflective coping is an adaptive approach/engagement type of coping; whereas, suppressive and reactive coping are maladaptive avoidant/disengagement (Heppner et al. 1995) types of coping.

Our coping style measures (Heppner et al. 1995) were chosen for their ability to combat a problem of ambiguity found within previously generated measures of coping style. In contrast to other measures of coping (c.f., Carver et al. 1989), our selected measures (Heppner et al. 1995) provide specificity in item content and more clearly denote affective, behavioral, and cognitive components of a given coping activity. Additionally, our selected coping measures more effectively replicate the meaningful division of approach versus avoidant coping activities found within the coping literature. Inventory items aim at assessing whether a particular coping strategy moved a person toward or away from resolving one’s problem, thereby identifying a clearer sense of the helpfulness or harmfulness of a given coping strategy and further minimizing the primary problem of ambiguity (Heppner et al. 1995).

Some theorists have posited that the types of general coping strategies a person typically employs in life can mediate the link between experiences of oppression and psychological distress among minority group members (c.f., Clark et al. 1999; Szymanski and Obiri 2011). For sexual minority women, this means that as experiences of heterosexism and/or sexism increase there is a greater need for ways to deal with these environmental demands. Sexual minority women are likely to draw on their typical ways of coping to deal with the extra stress associated with heterosexism and sexism, and how an individual copes with these experiences can in turn influence mental health outcomes (Clark et al. 1999). Thus, more use of adaptive coping strategies, such as reflective coping, are theorized to lead to less psychological distress and the use of maladaptive coping strategies, such as suppressive and reactive coping, are theorized to lead to greater psychological distress. Despite these theoretical advances, only nine studies in a meta-analysis of 134 studies on perceived discrimination included coping variables (Pascoe and Smart Richman 2009).

Focusing specifically on internalized oppression, other scholars drawing from feminist and sexual identity theories (e.g., Cass 1979; Sophie 1987; Downing and Roush 1985) have postulated that coping styles are likely to mediate the internalized heterosexism and internalized sexism-distress links because sexual minority women with high internalized oppressions may be more likely to engage in maladaptive coping strategies, such as inhibiting sexual behavior with other women, passing or pretending heterosexuality, denying personal relevance of information regarding women, and withdrawing from other women and lesbian, gay, and bisexual persons (Szymanski et al. 2008a). In addition, reducing internalized heterosexism and internalized sexism are often important precursors to developing adaptive coping strategies such that sexual minority women with low levels of internalized oppression may be more likely to engage in adaptive coping strategies to eliminate the source of stress and actively confront heterosexism and sexism through a variety of means (e.g., confronting heterosexist and/or sexist behaviors of others; supporting lesbian, gay, and bisexual and women friendly businesses and organizations, fighting discriminatory laws; Kashubeck-West et al. 2008). Thus, coping styles would play a mediating role if internalized heterosexism and internalized sexism lead to the use of less adaptive coping styles and more maladaptive coping styles, which in turn, creates greater levels of psychological distress.

Supporting these theoretical assertions, Szymanski and Owens (2009) found that avoidant coping (but not problem solving coping) partially mediated the relationship between internalized heterosexism and psychological distress among sexual minority women. Although we could not find any studies examining the mediating role of coping styles between heterosexist events, sexist events, and internalized sexism and psychological distress, research on external and internalized racism provide some evidence for these links. For example, experiences of racist events among African American persons are positively correlated with the use of problem solving, support seeking and avoidant coping styles (Utsey et al. 2000), and with more positive and negative religious coping (Szymanski and Obiri 2011). In terms of mediation, culturally specific avoidant or negative coping partially mediated the relationship between gendered racism and African American women’s psychological distress (Thomas et al. 2008). In addition, Szymanski and Obiri (2011) found that negative religious coping (but not positive religious coping) partially mediated the relationship between racist events and internalized racism and African American persons’ psychological distress. Consistent with these findings, other research examining links between coping style and psychological outcomes suggests that maladaptive/negative coping styles are more important than adaptive/positive coping styles in predicting mental health outcomes (c.f ., Dyson and Renk 2006; Lehavot 2012; Pargament et al. 1998, 2000; Nyamathi et al. 1993; Szymanski and Owens 2009; Utsey et al. 2000). For example, Lehavot (2012) found that maladaptive coping strategies, especially disengagement and self-blame, were significantly associated with poorer mental health among sexual minority women, and maladaptive coping was generally a stronger predictor of mental health than adaptive coping. Thus, generalizing these findings to oppression among sexual minority women, it seems that suppressive and reactive coping styles might mediate the links between external and internalized heterosexism and sexism and psychological distress but reflective coping will not.

Age

Findings from both cross-sectional and longitudinal studies reveal that negative emotional experiences, such as psychological distress, decrease with age (for a review see Charles and Carstensen 2007). Some developmental models, such as the Strength and Vulnerability Integration model (Charles 2010), suggest that these decreases may be due to age-related enhancement in the use of strategies that serve to avoid or limit exposure to negative stimuli and to the use of more mature coping behaviors that result from gaining experience and practice in navigating life’s problems over time. Supporting theses notions, several studies have found evidence for effects of age on people’s coping processes. For example, Aldwin (1991) found that older adults and younger adults differed in the types of problems they faced, stress appraisals, attributions, and the use of escape as a coping strategy. Relatedly, Diehl et al. (1996) found that older adults used strategies indicative of greater impulse control and tendencies to positively appraise situations of conflict, while younger adults responded with more aggressive coping strategies that indicated lower levels of impulse control and self-awareness. Other developmental findings reveal that as people move from adolescence to late middle-age, they move in the direction of more adaptive and less maladaptive coping and defense strategies (Diehl et al. 2013; Folkman et al. 1987). Given this array of evidence that coping strategies and their effectiveness are affected by age, we included age as a covariate in our analysis.

Current Study

In sum, additive approaches to multiple oppressions have garnered some support as they relate to the mental health of sexual minority women. However, more research in this area is needed. Thus, the purpose of our study was to examine concurrently external and internalized heterosexism and sexism as it relates to sexual minority women’s psychological distress. In addition, we examined the mediating effects of three coping styles on the relations of heterosexist events, sexist events, internalized heterosexism, and internalized sexism and psychological distress. Because coping strategies and their effectiveness are affected by age, we included age as a covariate in our analyses. Our specific hypotheses were:

-

Hypothesis 1: When examined concurrently in a regression analysis that controls for age, heterosexist events, sexist events, internalized heterosexism and internalized sexism will have direct, positive, and unique links to psychological distress.

-

Hypothesis 2: After controlling for age, reactive coping and suppressive coping will mediate the relationships between heterosexist events, sexist events, internalized heterosexism, and internalized sexism and psychological distress. Reflective coping is not expected to mediate the relationships between heterosexist events, sexist events, internalized heterosexism, and internalized sexism and psychological distress.

To test hypothesis 1, a simultaneous multiple regression was conducted using age as a covariate.

To test hypothesis 2, bootstrap analyses for multiple mediation were conducted and age was entered as a covariate (Mallinckrodt et al. 2006; Preacher and Hayes 2008). Mediation analysis experts increasingly recommend bootstrap confidence intervals, which do not erroneously assume normality in the distribution of the mediated effect (c.f., Mallinckrodt et al. 2006; Preacher and Hayes 2008; Shrout and Bolger 2002). In addition, bootstrapping frees up power to assess multiple mediation models, reduces the number of tests, and controls for Type I error rates (Preacher and Hayes 2008).

Method

Participants

The initial sample comprised 496 participants who completed an online survey. One self-identified heterosexual participant, three self-identified male participants, one 16 year old participant, eight participants who resided outside the United States, one participant who did not report her age, and nine participants who left at least one measure completely blank were eliminated from the dataset, which resulted in a final sample of 473 participants.

Sixty two percent of participants identified themselves as lesbian, 33 % as bisexual, and 5 % as not sure. Consistent with Diamond’s (2005, 2008) work on the fluidity, variability and non-exclusivity of sexual minority women’s identity, attractions, and behavior, there was some discrepancy between participants’ self-identification of their sexual identity and their description of their current feelings of romantic/sexual attraction, with 39 % attracted only to women (0); 39 % attracted more to women than men, 11 % attracted equally to both sexes, 10 % attracted more to men than women, and 0 % attracted only to men.

Participants ranged in age from 18 to 74 years, with a mean age of 33.46 years (SD = 14.11). Age had acceptable normality levels with skewness = .839 and kurtosis = −.413. The sample was 3 % African American/Black, 5 % Asian American/Pacific Islander, 5 % Hispanic/Latina, 1 % Native American, 81 % White, 4 % Multiracial, and 2 % Other. Forty seven percent (n = 224) of participants were currently enrolled in a college or university, with 14 % being 1st year undergraduates, 19 % Sophomores, 13 % Juniors, 17 % Seniors, 34 % graduates students, and 4 % Other. Of the 53 % who were not currently students (n =249), 1 % attained less than high school diploma, 4 % attained a high school diploma, 12 % attained a two-year college degree, 31 % attained a four-year college degree, and 52 % attained a graduate/professional degree. Self-reported social class was 2 % Wealthy, 15 % Upper-Middle Class, 48 % Middle Class, 28 % Working Class, and 7 % Poor. Participants resided in the Midwest (21 %), Northeast (34 %), South (23 %), and West (22 %). Percentages may not add up to 100 % due to rounding.

Of those participants who were included in the study, some had missing data. Analysis of the patterns of missing data revealed that less than .24 % of all items for all cases were missing, and 40.56 % of the items were not missing data for any case. Considering individual cases, 77.17 % of participants had no missing data. Finally, no item had 2.2 % or more of missing values. In addition, Little’s Missing Completely at Random analysis revealed an insignificant chi-square statistic, X 2 (11593) = 11638.089, p = .38, indicating that the data was missing completely at random. Given the very small amount of missing data, we used available case analyses procedures to address missing data points. When dealing with low-level item –level missingness, available case analysis is preferred over mean substitution because the latter can produce inflation of correlation coefficients among items (Parent 2013).

Measures

Heterosexist Events

Heterosexist events were assessed using the sexual minority women’s version of the Heterosexist Harassment, Rejection, and Discrimination Scale (Szymanski 2006), which consists of 14 items reflecting the frequency with which sexual minority women report having experienced heterosexist harassment, rejection, and discrimination. Participants were asked to report the frequency of heterosexist events that occurred within the past 6 months. Example items include “How many times have you been made fun of, picked on, pushed, shoved, hit, or threatened with harm because you are a lesbian/bisexual woman?” and “How many times have you been rejected by family members because you are a lesbian/bisexual woman?” Each item is rated on a 6-point Likert scale from 1 = the event has never happened to you to 6 = the event happened almost all the time (more than 70 % of the time). Mean scores were used with higher scores indicating greater experiences of heterosexist harassment, rejection, and discrimination in the past 6 months. Reported alpha for scores on the Heterosexist Harassment, Rejection, and Discrimination Scale with a sexual minority female sample was .90. Validity was supported by exploratory factor analysis, by significant positive correlations with measures assessing depression, anxiety, interpersonal sensitivity, somatization, obsessive compulsiveness, and overall psychological distress, and by demonstrating that the Heterosexist Harassment, Rejection, and Discrimination Scale was conceptually distinct from internalized heterosexism (Szymanski 2006). Cronbach alpha for the current sample was .91.

Sexist Events

Sexist events were assessed using the Daily Sexist Events Scale (Swim et al. 1998), which consists of 26 items assessing sexism in the forms of traditional gender role stereotyping and prejudice and unwanted sexually objectifying comments and behaviors. Participants were asked to indicate how often during the past 6 months they experienced a variety of sexist events. Example items include “Heard someone express disapproval of me because I exhibited behavior inconsistent with stereotypes about my gender,” and “Had people shout sexist comments, whistle, or make catcalls at me.” Participants were asked to report the frequency of sexist events that occurred within the past 6 months using the following 5-point Likert scale: 1 (never), (2) about once during the past during past 6 months, (3) about once a month during the past 6 months, (4) about once a week during the past 6 months, and (5) about two or more times a week during the past 6 months. Mean scores were used with higher scores indicating the experience of more sexist events. Reported alpha for scores on the Daily Sexist Events Scale with a lesbian and bisexual female sample was .95 (Szymanski and Owens 2009). Content and construct validity were supported by a series of daily dairy studies of sexist experiences; exploratory factor analyses; findings indicating that women reported more sexist events than men; correlations demonstrating that more experiences of sexist events were related to more anger, greater depression, decreased comfort, and less self-esteem among women; and that sexist events were not related to neuroticism (Swim et al. 1998, 2001). Cronbach alpha for the current sample was .95.

Internalized Heterosexism

Internalized heterosexism was assessed using the Internalized Homophobia Scale (Herek et al. 2000; Martin and Dean 1987), which consists of nine items reflecting the extent to which sexual minority women reject their sexual orientation, seek to avoid attractions and romantic feelings to other women, and are uncomfortable about their sexual desires toward other women. Example items include “I have tried to stop being attracted to women in general” and “If someone offered me the chance to be completely heterosexual, I would accept the chance.” Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Mean scores were used with higher scores indicating greater internalized heterosexism. Reported alpha for scores on the Internalized Homophobia Scale with a lesbian/bisexual female sample was .71 (Herek et al. 1998). Validity of scores was supported by correlating the Internalized Homophobia Scale with other internalized heterosexism scales, measures assessing self-esteem, depression, connection with and feelings toward the lesbian, gay, and bisexual community, degree of outness, and perceived stigma related to being lesbian, gay, or bisexual (Frost and Meyer 2009; Herek et al. 1998, 2000; Szymanski and Kashubeck-West 2008; Szymanski and Owens 2008). Cronbach alpha for the current sample was .87.

Internalized Sexism

Internalized sexism was assessed using the Internalized Misogyny Scale (Piggot 2004), which consists of 17 items reflecting three dimensions: devaluing of women, distrust of women, and valuing men over women. Example items include “It is generally safer not to trust women too much” and “I prefer to work for a male boss.” Each item is rated on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Mean scores were used with higher scores indicating greater internalized sexism. Reported alpha for scores on the Internalized Misogyny Scale with a sexual minority female sample was .88. Validity of Internalized Misogyny Scale scores was supported by feedback from a focus group, exploratory factor analysis, and correlating it with measures of modern sexism, internalized heterosexism, depression, self-esteem, psychosexual adjustment, and body image (Piggot 2004). Cronbach alpha for the current sample was .88.

Coping Styles

Individual coping styles were assessed using the Problem Focused Style of Coping Scale (Heppner et al. 1995), which consists of 18 items reflecting three individual coping style factors: reflective, suppressive, and reactive. Example items for each factor respectively include “I think my problems through in a systematic way,” “I avoid even thinking about my problems,” and “I act too quickly, which makes my problems worse.” Each item is rated using a 5-point Likert scale from (1) almost never to (5) almost all the time. Higher mean scores indicate more frequent endorsement of respective coping styles.

Heppner et al. (1995) reported alphas for scores on the reflective style ranged from .77 to .80; for the suppressive style .76 to .77; and reactive style .67 to .73. Estimated three-week test-retest reliability for the factors were .67 (reflective style), .65 (suppressive style), and .71 (reactive style). Validity of scores on the Problem Focused Style of Coping Scale was supported by exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses, by correlating the Problem Focused Style of Coping Scale with other measures of coping and measures assessing amount of personal problems, depression, anxiety, global psychological distress, and locus of control, and by demonstrating that it was conceptually distinct from social desirability and neuroticism (Heppner et al. 1995). Cronbach alphas for the current sample were .85 (reflective style), .87 (suppressive style), and .84 (reactive style).

Psychological Distress

Psychological distress was assessed using the Hopkins Symptom Checklist (Derogatis et al. 1974), which consists of 58 items reflecting psychological distress across five symptom dimensions: anxiety, depression, interpersonal sensitivity, somatization, and obsessive compulsiveness. Examples of items include “Nervousness or shakiness inside,” “Feeling no interest in things,” and “Thoughts of ending your life”. Participants indicate how often they have felt each symptom during the past several days using a 4-point Likert scale from 1 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). Mean scores were used with higher scores indicating greater psychological distress. Reported alpha for scores on the Hopkins Symptom Checklist ranged from .84 to .87 in the scale development studies. Test-retest reliabilities ranged from .75 to .84. Reported alpha for scores on the Hopkins Symptom Checklist with a sexual minority female sample was .97 (Szymanski and Kashubeck-West 2008). Validity of the Hopkins Symptom Checklist scores was supported by studies reflecting the factorial invariance of the Hopkins Symptom Checklist symptom dimensions, between group differences, and the Hopkins Symptom Checklist’s sensitivity to the use of psychotherapeutic drugs (Derogatis et al. 1974). Cronbach alpha for the current sample was .97.

Procedures

A web-based Internet survey was used to collect the data. As an incentive to participate, all participants were given the chance to enter a raffle drawing of $100 awarded to one person. Procedures for this website survey were based on published suggestions for internet surveys in general (Buchanan and Smith 1999; Michalak and Szabo 1998; Schmidt 1997) and with lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations specifically (Riggle et al. 2005). Methods for protecting confidentiality (i.e., having participants access the research survey via a hypertext link rather than e-mail to ensure participant anonymity and the use of a separate raffle database so there was no way to connect a person’s on-line raffle submission with her submitted survey) and ensuring data integrity (i.e., use of a secure server protected with a firewall to prevent tampering with data and programs by “hackers” and inadvertent access to confidential information by research participants) were used. Gosling et al. (2004) reported that results from Internet studies are not adversely affected by repeat or non-serious responders and are consistent with findings obtained from traditional pen-and-paper methods.

Participants were recruited via an e-mail announcement of the study sent to a variety of general lesbian and bisexual female-related listservs, groups, and organizations primarily found through internet searches of Gayyellowpages.com, Yahoo Groups, and university and community lesbian, gay, and bisexual centers. The email announcements were sent to an individual on the website listed as either “listserv owner” or “contact person.” This person was then asked to forward the research announcement to their listserv and to eligible colleagues and friends. Thus, sending the research announcement to a designated contact person or listserv owner provided the individual with the opportunity to determine whether or not she/he felt the research study was appropriate or of interest to his/her members (Riggle et al. 2005).

On the research announcement and consent form, participants were informed that the survey was part of “an empirical study examining attitudes, feelings, and experiences associated with being a woman who experiences attraction to members of the same sex. Historically, researchers have neglected the lives of lesbian and bisexual women, and very little research has looked specifically at attitudes and experiences that sexual minority women have based on both their sexual orientation and gender. This survey will ask questions about feelings, thoughts, and experiences you may have had as a sexual minority person and as a woman, ways you cope with life's challenges, psychosocial well-being, and demographics.” Potential participants used a hypertext link to access the survey website. After reading and acknowledging the informed consent page, participants were instructed to complete the online survey, which included the aforementioned measures which were randomly ordered.

Results

Frequency of External and Internalized Heterosexism and Sexism

The means and frequencies for the items on both the heterosexist events (Ms ranged from 1.23 to 2.09) and sexist events (Ms ranged from 1.21 to 3.26) measures were low in comparison to the maximum point on the scales used to assess these constructs, suggesting that participants did not encounter a great deal of heterosexism and sexism during the past 6 months. However, a closer inspection revealed that, although the frequency of occurrence was not high, reports of heterosexist harassment, rejection, and discrimination and sexist events occurring at least once during the past 6 months were fairly common. Across the various specific experiences of heterosexist events, 12 % (denied a raise, a promotion, tenure, a good assignment, a job, or other such thing at work) to 52 % (treated unfairly by strangers) reported experiencing the event at least once in awhile. In addition, 39 % reported being treated unfairly by co-workers, 45 % reported being called a heterosexist name, and 41 % reported being treated unfairly by people in service jobs at least once in awhile in the past 6 months. Furthermore, 51 % heard anti-gay remarks from family members, 48 % reported being treated unfairly by their family, and 36 % reported being rejected by family members at least once in awhile within the past 6 months.

Across the various specific experiences of sexist events, 17 % (been the victim of male violence) to 91 % (heard sexist jokes about women) reported experiencing the event at least once in the past 6 months. In addition, 65 % reported hearing disapproval for exhibiting behavior that was inconsistent with female gender stereotypes, 61 % reported being called a sexist name, 61 % reported hearing sexist comments about their body parts or clothing, and 46 % reported being threatened sexually at least once in the past 6 months.

Similar to experiences of external heterosexism and sexism, the means and frequencies for the items on both the internalized heterosexism (Ms ranged from 1.11 to 2.00) and internalized sexism (Ms ranged from 1.17 to 2.83) measures were low in comparison to the maximum point on the scales used to assess these constructs, suggesting that participants did not internalize a lot of heterosexism and sexism. However, a number of these participants did endorse some levels of internalized oppression. For example, endorsing either agreed or strongly agreed, 24 % reported trying to become more attracted to men, 22 % reported having tried to stop their attractions to other women, and 9 % reported feeling alienated from oneself because of being a sexual minority woman. Endorsing either slightly, moderately or strongly agree, 26 % reported that they are sometimes bothered by other women just being around them, 19 % believed that “Women are too easily offended,” 16 % believed that “Women exaggerate problems they have at work,” and 12 % reported preferring to work with men.

External and Internalized Heterosexism and Sexism and Psychological Distress

Means, standard deviations, and inter-correlations among all variables assessed in this study are shown in Table 1. Examination of skewness (range = .26 – 1.84) and kurtosis (range = −.20 – 4.12) for each variable indicated sufficient normality (i.e., skewness < 3, kurtosis < 10; Weston and Gore 2006). Consistent with the notion that coping strategies and their effectiveness are likely to be affected by age, age was significantly positively related to reflective coping and negatively related to suppressive and reactive coping and psychological distress (see Table 1). This finding underscores the need to include age as a covariate in the analyses.

To test hypothesis 1, a simultaneous multiple regression was conducted using age as a covariate. Thus, age was entered at Step 1, and the external and internalized heterosexism and sexism variables were added at Step 2. Before running the regression analysis several indices were examined to evaluate whether multicollinearity among predictor variables was a problem. Tabachnick and Fidell (2001) suggested that absolute value correlations below .90 and condition indexes below 30 indicate that multicollinearity is not problematic. Myers (1990) suggested that variance inflation factors below 10 also indicate that multicolinearity is not a problem. The highest absolute value correlation between predictor variables was .51, highest condition index value was 16.44, and highest variance inflation factor was 1.21 indicating that multicollinearity was not problematic. The results of the simultaneous regression analysis were significant, R 2 = .25, F (5, 467) = 30.70, p < .001. Supporting our hypothesis, heterosexist events (β = .21), sexist events (β = .15), internalized heterosexism (β = .15), and internalized sexism (β = .20) were all unique predictors of psychological distress (See Table 2).

To test the multiple mediation effects expressed in hypothesis 2, we used the Preacher and Hayes (2008) macro to create 1,000 bootstrap samples from the original data. We conducted one model with multiple independent variables and multiple mediators in predicting our dependent variable, psychological distress. Age was entered as a covariate, and the 1,000 bootstrap samples were run with the bias-corrected percentile method to estimate the path coefficients. Point estimates of the magnitude of the indirect effect, that is, the products of the alpha path (i.e., from the independent variable to the mediator) and beta path (i.e., from the mediator to the dependent variable), together with the associated 95 % confidence interval were also estimated through the same 1,000 bootstrap samples. If the confidence interval does not contain zero, one can conclude that mediation is significant and meaningful (Mallinckrodt et al. 2006; Preacher and Hayes 2008).

Supporting our hypothesis, suppressive coping and reactive coping mediated the external heterosexism-distress, internalized heterosexism-distress, and internalized sexism-distress links. Contrary to our hypothesis, suppressive coping and reactive coping did not mediate the external sexism-distress link. Supporting our hypothesis, reflective coping did not mediate the relations between external and internalized heterosexism and sexism and psychological distress (see Table 3). Finally, the variables in the model accounted for 54 % of the variance in psychological distress scores.

Discussion

The findings of the present study suggest that many sexual minority women experienced heterosexist and sexist events at least once during the past 6 months. A number of participants also indicated some level of internalized oppression. These findings support minority stress (Meyer 2003) and insidious trauma (Root 1992; Balsam 2003) theorists’ assertions that individuals from stigmatized social categories experience negative life events and excess stress because of their marginalized status or statuses. In addition, these theorists posit that low level, everyday heterosexist and sexist stressors constitute chronic stressors that may have a cumulative effect on the health and well-being of sexual minority women.

The present study aimed to contribute to the small but growing body of research focused on the relationships between multiple oppressions and mental health. Our findings revealed that when examined concurrently heterosexist events, sexist events, internalized heterosexism, and internalized sexism were significant and unique predictors of psychological distress. These findings lend additional support for the additive multiple oppression perspective as it pertains to sexual minority women. Our results also found that suppressive coping and reactive coping mediated the external heterosexism-distress, internalized heterosexism-distress, and internalized sexism-distress links but did not mediate the external sexism-distress link. Reflective coping also did not mediate the relations between external and internalized heterosexism and sexism and psychological distress.

Our findings are consistent with past research on the mediating roles of maladaptive coping in the link between internalized heterosexism and psychological distress (Szymanski and Owens 2009), while extending this mediational influence to the relations between heterosexist events and internalized sexism and psychological distress among sexual minority women. Our findings suggest that external heterosexism and both internalized heterosexism and sexism influence psychological distress indirectly through the use of suppressive and reactive coping.

It may be that sexual minority women who frequently use suppressive and/or reactive coping strategies believe that they cannot do anything about sexual orientation and gender-based oppression. Greater use of suppressive coping necessitates cognitive attempts to minimize the meaning or impact of heterosexism and/or internalized sexism and behavioral efforts to withdraw from it (Heppner et al. 1995). Thus, suppressive coping might increase passivity in response to heterosexist events, internalized heterosexism and/or internalized sexism; whereas, reactive coping might increase rumination and dwelling on how one is negatively affected by oppression which may in turn influence psychological distress levels (Wei et al. 2008). It is notable to mention that at least in this sample, sexual minority women experiencing higher levels of heterosexist events and/or sexist events were not more likely to utilize reflective coping, as Clark et al.’s (1999) theory would suggest. It may be that sexual minority women who experience heterosexist and/or sexist events may be more likely to utilize community/group-level coping, which was not accounted for within the present study. It is also interesting that suppressive coping and reactive coping did not mediate the sexist events and psychological distress link. Perhaps other mechanisms, such as silencing the self, social support, hope, and rumination, might be at play when experiencing sexism. In addition, the finding that reflective coping did not mediate the external and internalized heterosexism and sexism-distress links, underscores previous research (c.f., Szymanski and Obiri 2011; Szymanski and Owens 2009; Thomas et al. 2008) suggesting that employing problem-solving coping may be less important than eliminating maladaptive coping methods in relation to psychological distress.

Limitations

While the present study provides a valuable step forward in examining the additive affects of external and internalized heterosexism and sexism on sexual minority women’s mental health, including an additional investigation of the mediating role of coping styles within such links, there are four main study limitations to acknowledge: 1) self-selective sample and recruitment methods, 2) lengthy, self-reported data, 3) homogeneity of the sample, and 4) correlational and cross-sectional study design.

Our sample consisted of sexual minority women, recruited predominantly through listservs of lesbian, gay, and bisexual organizations and community resource programs, who self-selected to participate. Such women may possess greater degrees of outness and/or may be more connected to community/group-level coping resources which in turn promote lower levels of psychological distress, wider use of adaptive coping styles, and a buffering effect against external and internalized heterosexism and sexism. The sample may fail to accurately represent closeted women and those less connected to the lesbian, gay, and bisexual community who might exhibit wider use of maladaptive coping skills, while being isolated from any buffering effect that the lesbian, gay, and bisexual community might offer against external and internalized heterosexism and sexism.

Study data were collected through lengthy survey measures (e.g., the full survey would likely take about 30 min to complete) which collected self-reported information. Sexual minority women who chose to offer significant time by participating may be more motivated and less cognitively and affectively disheartened than non-participants. Furthermore, some participant data may reflect dishonest answers or be confounded by individual differences in conceptualizations about what constitutes instances of heterosexism and sexism. However, it is important to note that subjective perceptions reflect reality for our participants.

In concordance with other research samples of lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals, participants in this study were primarily White, well-educated women who self-identified as lesbian or bisexual. The homogeneity of the sample diminishes its representativeness and prohibits full generalizability to sexual minority women with differing social identities. While the additive model used within this study is an important advancement in exploring the effects of multiple minority identities, it does not account for other racial/ethnic, socio-economic and socio-cultural statuses. In addition, it fails to attend to the unique experiences of external and internalized bisexism that bisexual women may experience.

Although our theorizing and mediation analyses imply causal ordering, our study was correlational and cross-sectional, which precludes the ability to determine causality. We have captured a snapshot of oppression processes, found support for our model, and offered interpretations that are theoretically reasonable. Nevertheless, as with any study, other models could potentially explain relationships in the data. For example, it might be that sexual minority women with historical patterns of suppressive and reactive coping may be more susceptible to perceiving heterosexist events and to internalizing sexual orientation and gender-based oppressive experiences which in turn influences mental health outcomes. Alternatively, psychological distress could potentially shape perceptions and coping. Furthermore, it is possible that other, unmeasured variables such as lifetime and recent traumatic and stressful experiences that are not related to sexual orientation and gender might play a role in the relationships among variables in our study.

Future Research

Future research is needed to address more fully how various aspects of heterosexism and sexism impact sexual minority women’s lives. The present study focused on heterosexist and sexist events that are overt and occur primarily at the individual and interpersonal levels. Assessments of exposure to subtler forms of sexual orientation and gender based micro-aggressions, as well as to institutional and cultural forms of heterosexism and sexism are needed. Scales capturing the ways that external and internalized forms of heterosexism intersect with externalized and internalized sexism also need to be developed. Our study did not examine interactionist and intersectionality models, and these should be further addressed to enhance understanding of multiple forms of oppression.

This study examined coping styles as possible mediators in the multiple oppression-distress links. Considering coping styles as moderators might help shed more light on under what circumstances sexual minority women are susceptible to greater distress. For example, in our study adaptive coping was not supported as a mechanism that explains the relationship between oppression and mental health, but it could very well still be a moderator, wherein sexual minority women who are high in reflective coping experience less psychological distress in response to oppressive experiences compared to those low in reflective coping. Future research might examine other potential mediators (and moderators) in the multiple oppression-distress links, such as connection with the feminist community, connection with the sexual minority community, resilience, hardiness, cognitive ability, sexual identity development, feminist identity development, salience of sexual orientation and gender identity to the self, and attachment styles. In addition, the influence of external and internalized heterosexism and sexism on other outcomes variables, such as well-being and workplace outcomes is needed. Studies using prospective longitudinal designs would contribute to a better understanding of the causal relations among measures of external and internalized heterosexism and sexism, coping styles, and psychological distress.

Additional research is needed focusing on sexual minority women who may be less out and/or less connected to the lesbian, gay, and bisexual community and sexual minority women with additional minority identities (i.e. race, class, education, etc.) in order to capture the wider population of sexual minority women beyond the homogenous White, well-educated women of our sample. This aim may be accomplished by targeting women’s health facilities and community agencies, especially those serving women of minority racial identity and of low socioeconomic status. Finally, future research might identify the types of therapeutic experiences that reduce the strength of the relationship between multiple oppressions and poor mental health. Future research may address this important target area by executing preliminary qualitative methods within individual and group therapy with sexual minority women focused on heterosexism, sexism, coping styles, and psychological distress.

Clinical Implications

Most generally, our findings illustrate how gender and sexuality socialization influence sexual minority women through exposure to heterosexism and sexism, which in turn influences coping responses and psychological distress. Educators and counselors working with sexual minority women must be able to detect, explore, and challenge the variety of ways that heterosexist events, sexist events, internalized heterosexism, and internalized sexism influence their students’ and clients’ lives. In addition, they might help sexual minority women understand and recognize their experiences with external and internal heterosexism and sexism, as well as the relationship between these forms of oppression and their current problems. Helping sexual minority women explore affective and cognitive facets of sexual minority and gender oppression, and empowering them to detect and challenge these experiences may be particularly useful.

Based on the mediational findings within the present study, coping styles are valuable targets of intervention when working with sexual minority women. For example, mental health professionals might help sexual minority women clients understand how their experiences of external heterosexism and both internalized heterosexism and sexism may influence their use of maladaptive coping strategies and thereby influence their symptoms of distress. In addition, utilizing techniques designed to decrease levels of suppressive and reactive coping might be particularly helpful in reducing psychological distress.

Given that heterosexist and sexist events are experienced as individuals interface with others and institutions, interventions seeking to decrease psychological distress experienced by sexual minority women must encompass societal change. Efforts by educators, researchers, and clinicians to advocate for social justice may help to decrease the occurrence of heterosexist and sexist events. The lessening of such systemic and pervasive socio-cultural forces may alleviate levels of internalized heterosexism and internalized sexism by improving social equity for sexual minority women and lowering levels of heterosexist and sexist messages available for internalization (Szymanski and Obiri 2011).

Conclusions

In conclusion, the findings of our study provide further support for the additive multiple oppression perspective, and underscore the importance of attending to both heterosexism and sexism in the lives and mental health of sexual minority women. It extends previous research by suggesting that these positive relationships exist because external heterosexism, internalized heterosexism, and internalized sexism lead sexual minority women to use more suppressive and reactive coping styles, which in turn negatively influence their psychological health. Finally, the multiple oppression and coping variables accounted for a large amount of variance in psychological distress scores.

References

Aldwin, C. M. (1991). Does age affect the stress and coping process? Implications of age differences in perceived control. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences, 46, 174–180. doi:10.1093/geronj/46.4.P174.

Almeida, J., Johnson, R. M., Corliss, H. L., Molnar, B. E., & Azrael, D. (2009). Emotional distress among LGBT youth: The influence of perceived discrimination based on sexual orientation. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38, 1001–1014. doi:10.1007/s10964-009-9397-9.

American Psychological Association (2004). Answers to your questions about sexual orientation and homosexuality. Retrieved from http://www.apa.org/pubinfo/answers.html

American Psychological Association. (2007). Guidelines for psychological practice with girls and women. American Psychologist, 62, 949–979. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.62.9.949.

Balsam, K. F. (2003). Traumatic victimization in the lives of lesbian and bisexual women: A contextual approach. Journal of Lesbian Studies, 7, 1–14. doi:10.1300/J155v07n01_01.

Balsam, K. F., & Mohr, J. J. (2007). Adaptation to sexual orientation stigma: A comparison of bisexual and lesbian/gay adults. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 54, 306–319. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.54.3.306.

Balsam, K. F., Rothblum, E. D., & Beauchaine, T. P. (2005). Victimization over the life span: A comparison of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and heterosexual siblings. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73, 477–487. doi:10.1037//0022-006X.73.3.477.

Bowleg, L. (2008). When African American + lesbian + woman ≠ African American lesbian woman: The methodological challenges of qualitative and quantitative intersectionality research. Sex Roles, 59, 312–325. doi:10.1007/s11199-008-9400-z.

Buchanan, N. T., & Fitzgerald, L. F. (2008). Effects of racial and sexual harassment on work and the psychological well-being of African American women. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 13, 137–151. doi:10.1037/1076-8998.13.2.137.

Buchanan, T., & Smith, J. L. (1999). Using the Internet for psychological research: Personality testing on the World Wide Web. British Journal of Psychology, 90, 125–144. doi:10.1348/000712699161189.

Carver, C. S., Scheier, M. F., & Weintraub, J. K. (1989). Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56, 267–283. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.56.2.267.

Cass, V. C. (1979). Homosexual identity formation: A theoretical model. Journal of Homosexuality, 4, 219–235. doi:10.1300/J082v04n03_01.

Charles, S. T. (2010). Strength and vulnerability integration (SAVI): A model of emotional well-being across adulthood. Psychological Bulletin, 13, 1068–1091. doi:10.1037/a0021232.

Charles, S. T., & Carstensen, L. L. (2007). Emotion regulation and aging. In J. J. Bross (Ed.), Handbook of emotion regulation (pp. 307–327). New York: Guilford.

Clark, R., Anderson, N. B., Clark, V. R., & Williams, D. R. (1999). Racism as a stressor for African Americans: A biopsychosocial model. American Psychologist, 54, 805–816. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.54.10.805.

Cochran, S. D. (2001). Emerging issues in research on lesbians’ and gay men’s mental health: Does sexual orientation really matter? American Psychologist, 56, 931–947. doi:10.1037/0003-066x.55.12.1440.

Cole, E. R. (2009). Intersectionality and research in psychology. American Psychologist, 64, 170–180. doi:10.1037/a0014564.

Collins, P. H. (1991). African American feminist thought: Knowledge, consciousness, and the politics of empowerment. New York: Routledge.

D’Augelli, A. R., Grossman, A. H., & Starks, M. T. (2006). Parents’ awareness of lesbian, gay, and bisexual youths’ sexual orientation. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67, 474–482. doi:10.1177/0886260506293482.

Derogatis, L. R., Lipman, R. S., Rickets, K., Uhlenhuth, E. H., & Covi, L. (1974). The Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL): A self-report symptom inventory. Behavioral Science, 19, 1–14. doi:10.1002/bs.3830190102.

Diamond, L. M. (2005). A new view of lesbian subtypes: Stable versus fluid identity trajectories over an 8-year period. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 29, 119–128. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.2005.00174.x.

Diamond, L. M. (2008). Female bisexuality from adolescence to adulthood: Results from a 10- year longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology, 44, 5–14. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.44.1.5.

Diehl, M., Coyle, N., & Labouvie-Vief, G. (1996). Age and sex differences in strategies of coping and defense across the life span. Psychology and Aging, 11, 127–139. doi:10.1037/0882-7974.11.1.127.

Diehl, M., Chui, H., Hay, E. L., Lumley, M. A., Grühn, D., & Labouvie-Vief, G. (2013). Change in coping and defense mechanisms across adulthood: Longitudinal findings in a European American sample. Developmental Psychology. doi:10.1037/a0033619. Advance online publication.

Downing, N., & Roush, K. (1985). From passive acceptance to active commitment: A model of feminist identity development for women. The Counseling Psychologist, 13, 695–709. doi:10.1177/0011000085134013.

Dyson, R., & Renk, K. (2006). Freshmen adaptation to university life: Depressive symptoms, stress, and coping. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 62, 1231–1244. doi:10.1002/jclp.20295.

Fischer, A. R., & Bolton Holtz, K. (2010). Testing a model of women’s personal sense of justice, control, well-being, and distress in the context of sexist discrimination. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 34, 297–310.

Fischer, A. R., Tokar, D. M., Mergl, M. M., Good, G. E., Hill, M. S., & Blum, S. A. (2000). Assessing women’s feminist identity development: Studies of convergent, discriminant, and structural validity. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 24, 15–29. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.2000.tb01018.x.

Folkman, S., Lazarus, R. S., Pimley, S., & Novacek, J. (1987). Age differences in stress and coping processes. Psychology and Aging, 2, 171–184. doi:10.1037/0882-7974.2.2.171.

Frost, D. M., & Meyer, I. H. (2009). Internalized homophobia and relationship quality among lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 56, 97–109. doi:10.1037/a0012844.

Galupo, M. P. (2007). Women’s close friendships across sexual orientation: A comparative analysis of lesbian-heterosexual and bisexual-heterosexual women’s friendships. Sex Roles, 56, 473–482. doi:10.1007/s11199-007-9186-4.

Gosling, S. D., Vazire, S., Srivastava, S., & John, O. P. (2004). Should we trust web-based studies: A comparative analysis of six preconceptions about Internet questionnaires. American Psychologist, 59, 93–104. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.59.2.93.

Hatzenbuehler, M. L. (2009). How does sexual minority stigma “get under the skin?”: A psychological mediation framework. Psychological Bulletin, 135, 707–730. doi:10.1037/a0016441.

Heppner, P. P., & Lee, D. (2002). Problem solving appraisal and psychological adjustment. In C. R. Snyder & S. J. Lopez (Eds.), Handbook of positive psychology (pp. 288–298). New York: Oxford University.

Heppner, P. P., Cook, S. W., Wright, D. M., & Johnson, W. C., Jr. (1995). Progress in resolving problems: A problem focused style of coping. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 42, 279–293. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.42.3.279.

Herek, G. M. (2009). Hate crimes and stigma-related experiences among sexual minority adults in the United States: Prevalence estimates from a national probability sample. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 24, 54–74. doi:10.1177/0886260508316477.

Herek, G. M., Cogan, J. C., Gillis, J. R., & Glunt, E. K. (1998). Correlates of internalized homophobia in a community sample of lesbians and gay men. Journal of the Gay and Lesbian Medical Association, 2, 17–25. doi:10.1016/0145-2134(92)90011-f.

Herek, G.M., Cogan, J.C., & Gillis, J.R. (2000). Psychological well-being and commitment to lesbian, gay, and bisexual identities. Paper presented in G.M. Herek (Chair), Identity, community, and well-being among lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association

Horne, S. G., & Biss, W. J. (2009). Equality discrepancy between women in same-sex relationships: The mediating role of attachment in relationship satisfaction. Sex Roles, 60, 721–730. doi:10.1007/s11199-008-9571-7.

Kashubeck-West, S., Szymanski, D. M., & Meyer, J. (2008). Internalized heterosexism: Clinical implications and training considerations. The Counseling Psychologist, 36, 615–630. doi:10.1177/0011000007309634.

King, K. R. (2003). Racism or sexism? Attributional ambiguity and simultaneous membership in multiple oppressed groups. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 33, 223–247. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2003.tb01894.x.

Klevens, C. L. (2008). Coping style as a moderator between gendered racism and emotional eating and binge eating in African American women. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering, 68(10-B), 6968.

Landrine, H., Klonoff, E. A., Alcaraz, R., Scott, J., & Wilkins, P. (1995). Multiple variables in discrimination. In B. Lott & D. Maluso (Eds.), The social psychology of interpersonal discrimination (pp. 193–224). New York: Guilford.

Lehavot, K. (2012). Coping strategies and health in a national sample of sexual minority women. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 82, 494–504. doi:10.1111/j.1939-0025.2012.01178.x.

Lehavot, K., Molina, Y., & Simoni, J. M. (2012). Childhood trauma, adult sexual assault, and adult gender expression among lesbian and bisexual women. Sex Roles, 67, 272–284. doi:10.1007/s11199-012-0171-1.

Mallinckrodt, B., Abraham, W. T., Wei, M., & Russell, W. (2006). Advances in testing the statistical significance of mediation effects. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53, 372–378. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.53.3.372.

Martin, J.L., & Dean, L.L. (1987). Ego-dystonic homosexuality scale. Unpublished manuscript, Columbia University. Available at: http://psychology.ucdavis.edu/rainbow/html/ihpitems.html

Mays, V. M., & Cochran, S. D. (2001). Mental health correlates of perceived discrimination among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the United States. American Journal of Public Health, 91, 1869–1876. doi:10.2307/2676322.2001-10008-004.

Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129, 674–697. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674.

Michalak, E. E., & Szabo, A. (1998). Guidelines for internet research: An update. European Psychologist, 3, 70–75. doi:10.1027//1016-9040.3.1.70.

Moradi, B., & Subich, L. M. (2003). A concomitant examination of the relations of perceived racist and sexist events to psychological distress for African American women. The Counseling Psychologist, 31, 451–469. doi:10.1177/0011000003031004007.

Myers, R. (1990). Classical and modern regression with application (2nd ed.). Boston: Duxbury.

Nelson, N. L., & Probst, T. M. (2004). Multiple minority individuals: Multiplying the risk of workplace harassment and discrimination. In J. L. Chin (Ed.), The psychology of prejudice and discrimination (pp. 193–217). Westport: Praeger.

Nyamathi, A., Wayment, H. A., & Dunkel-Schetter, C. (1993). Psychosocial correlates of emotional distress and risk behavior in African-American women at risk for HIV infection. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping: An International Journal, 6, 133–148. doi:10.1080/10615809308248375.

Parent, M. C. (2013). Handling item-level missing data: Simpler is just as good. The Counseling Psychologist, 41, 568–600. doi:10.1177/0011000012445176.

Pargament, K. I., Smith, B. W., Koenig, H. G., & Perez, L. (1998). Patterns of positive and negative religious coping with major life stressors. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 18, 710–724. doi:10.2307/1388152.

Pargament, K. I., Koenig, H. G., & Perez, L. (2000). The many methods of religious coping: Development and initial validation of the RCOPE. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 56, 519–543. doi:10.1177/0011000003031004007.

Pascoe, E. A., & Smart Richman, L. (2009). Perceived discrimination and health: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 135, 532–554. doi:10.1037/a0016059.

Piggot, M. (2004). Double jeopardy: Lesbians and the legacy of multiple stigmatized identities. Unpublished thesis, Psychology Strand at Swinburne University of Technology, Australia.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40, 879–891. doi:10.3758/BRM,40.3.879.

Riggle, E. D. B., Rostosky, S. S., & Reedy, C. S. (2005). Online surveys for LGBT research: Issues and techniques. Journal of Homosexuality, 49, 1–21. doi:10.1300/J082v49n02_01.

Root, M. P. (1992). Reconstructing the impact of trauma on personality. In L. S. Brown & M. Ballou (Eds.), Personality and psychopathology: Feminist reappraisals (pp. 229–265). New York: Guilford.

Schmidt, W. C. (1997). World-Wide Web survey research: Benefits, potential problems, and solutions. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 2, 274–279. doi:10.3758/BF03204826.

Shields, S. A. (2008). Gender: An intersectionality perspective. Sex Roles, 59, 301–311. doi:10.1007/s11199-008-9501-8.

Shrout, P. E., & Bolger, N. (2002). Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 7, 422–445. doi:10.1037/1082-989X.7.4.422.

Sophie, J. (1987). Internalized homophobia and lesbian identity. Journal of Homosexuality, 14, 53–65. doi:10.1300/J082v14n01_05.

Swim, J. K., Cohen, L. L., & Hyers, L. L. (1998). Experiencing everyday prejudice and discrimination. In J. K. Swim & C. Stangor (Eds.), Prejudice: The target’s perspective (pp. 37–60). San Diego: Academic.

Swim, J. K., Hyers, L. L., Cohen, L. L., & Ferguson, M. J. (2001). Everyday sexism: Evidence for its incidence, nature, and psychological impact from three daily diary studies. Journal of Social Issues, 57, 31–53. doi:10.1111/0022-4537.00200.

Szymanski, D. M. (2004). Relations among dimensions of feminism and internalized heterosexism in lesbians and bisexual women. Sex Roles, 51, 145–159. doi:10.1023/B:SERS.0000037759.33014.55.

Szymanski, D. M. (2005). Heterosexism and sexism as correlates of psychological distress in lesbians. Journal of Counseling & Development, 83, 355–360. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2005.tb00355.x.

Szymanski, D. M. (2006). Does internalized heterosexism moderate the link between heterosexist events and lesbians’ psychological distress? Sex Roles, 54, 227–234. doi:10.1007/s11199-006-9340-4.

Szymanski, D. M., & Chung, Y. B. (2003). Feminist attitudes and coping resources as correlates of lesbian internalized heterosexism. Feminism & Psychology, 13, 369–389. doi:10.1177/0959353503013003008.

Szymanski, D. M., & Gupta, A. (2009a). Examining the relationship between multiple oppressions and Asian American sexual minority persons’ psychological distress. Journal of Gay and Lesbian Social Services, 21, 267–281. doi:10.1080/10538720902772212.

Szymanski, D. M., & Gupta, A. (2009b). Examining the relationship between multiple internalized oppressions and African American lesbian, gay, and bisexual persons’ self- esteem and psychological distress. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 56, 110–118. doi:10.1037/a0013317.

Szymanski, D. M., & Kashubeck-West, S. (2008). Mediators of the relationship between internalized oppressions and lesbian and bisexual women’s psychological distress. The Counseling Psychologist, 36, 575–594. doi:10.1177/0011000007309490.

Szymanski, D. M., & Meyer, D. (2008). Racism and heterosexism as correlates of psychological distress in African American sexual minority women. Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling, 2, 94–108. doi:10.1080/15538600802125423.

Szymanski, D. M., & Moffitt, L. B. (2012). Sexism and heterosexism. In N. A. Fouad (Ed.), Handbook of counseling psychology: Volume 2 Theories, Practice, training, and policy (pp. 361–390). Washington: American Psychological Association.

Szymanski, D. M., & Obiri, O. (2011). Do religious coping styles moderate or mediate the external and internalized racism-distress links? The Counseling Psychologist, 39, 438–462. doi:10.1177/0011000010378895.