Abstract

Self-objectification is often understood as a consequence of internalizing unrealistic media ideals. The consequences of self-objectification have been well studied and include depression and self-harm. We argue that body surveillance, a component of self-objectification that involves taking an observer’s perspective on oneself, is conceptually related to dissociation, a variable related to depression and self-harm. We hypothesized that the normative experience of self-objectification may increase the risk that young women dissociate in other contexts, providing an additional indirect path between self-objectification, depression, and self-harm. Snowball sampling begun with postings on Facebook was used to recruit 160 women, believed to be primarily from the U.S., to complete an online survey about the effects of media on young women. All participants ranged in age from 18–35 (M = 23.12, Median = 22, Mode = 21). Using this sample, we tested a path model in which internalization of media ideals led to body surveillance and body shame, body surveillance led to dissociation and body shame, body shame and dissociation led to depression, and dissociation and depression led to self-harm. This model, in which we controlled for the effects of age, had good fit to the data. Our findings suggest that self-harm and dissociation, both outcomes associated with the literature on trauma, are related to self-objectification. These relationships are discussed in terms of conceptualizing objectification and self-objectification as a form of insidious trauma or microaggression. Clinical implications are also discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In a society, such as the United States, that is largely based on appearance, women are taught that how their bodies look may be more important than their emotional state or physical capabilities (McKinley and Hyde 1996). Objectification involves a view of the female body that reduces the value of a woman to that of an object (Fredrickson and Roberts 1997). A major component of Fredrickson and Roberts’ (1997) objectification theory suggests that women are socialized to evaluate themselves based on their bodies and/or their outer appearance. One consequence of living in an objectified culture is that women tend to self-objectify, which involves taking an outsider’s view of oneself, also known as engaging in body surveillance (Fredrickson and Roberts 1997; McKinley and Hyde 1996). The negative effects of self-objectification have been well documented in samples from the U.S., Australia, and many countries in Europe (for a review see Moradi and Huang 2008), and we argue that being exposed to objectified images and engaging in self-objectification, or body surveillance, can be considered somewhat traumatic experiences. Thus, we hoped to extend the understanding of the negative effects of self-objectification by looking at self-harm, a variable more commonly associated with trauma, as a distal outcome. Furthermore, as body surveillance involves a distancing from the body, we proposed that dissociation, another variable commonly associated with trauma, may be a mechanism by which some of the negative effects occur. By conceptualizing the effects of self-objectification, or body surveillance, as akin to the effects of mild trauma, this research importantly points to potential predictors of serious clinical outcomes that are commonplace and experienced by large numbers of women worldwide. This research was conducted in the United States using an online survey. However, the consequences of objectification (see Moradi and Huang 2008 for a review of research from many countries in Europe as well as the U.S. and Australia) and the predictors of self-harm (see Fliege et al. 2009 for a review of research from many countries including the U.S., U.K., Canada, and Turkey) have been studied in a wide variety of countries, and findings have been relatively consistent across samples. Thus, the findings of the present study would likely be of interest to a broad, international audience.

It has been suggested that the media is a primary way through which objectifying culture spreads by portraying women’s bodies in objectified and sexualized manners (Fredrickson and Roberts 1997). Furthermore, a content analysis of media images from the U.S. has confirmed that the media displays women in an objectifying manner (Conley and Ramsey 2011). However, it is not just exposure to objectifying media, but internalization of the objectifying messages from the media, as indicated by research conducted in the United States, that may cause women to self-objectify (Aubrey 2006a, b). Calogero et al. (2005) found that internalization of media ideals was a significant predictor of self-objectification in a U.S. sample of women in a residential treatment program for eating disorders. They concluded that women may vary in the extent to which they internalize the media’s messages and that the individual difference variable of media internalization has important clinical consequences. Other research including both undergraduates and adolescent participants from the U.K. (Calogero and Thompson 2009) and Switzerland (Knauss et al. 2008) has confirmed the link between the extent to which young women internalize of media ideals and their propensity to engage in body surveillance. Thus, internalization is likely a factor involved in the constant viewing of oneself as a sexual object and can be conceptualized as a precursor to experiencing the negative effects of self-objectification.

Research conducted in the United States with both undergraduate women and their mothers has suggested that the primary mechanism through which self-objectification, or body surveillance, has its negative effects is through the experience of body shame (McKinley and Hyde 1996). This occurs when the habitual body monitoring associated with body surveillance reveals that one’s body does not live up to societal standards of beauty and thinness (McKinley and Hyde 1996). In a number of studies including participants from the U.S. (Chen and Russo 2010; McKinley and Hyde 1996) and Australia (Tiggemann and Slater 2001; Tiggemann and Kuring 2004; Tiggemann and Williams 2012) involving women ranging in age from undergraduates to older women, surveillance has been linked to body shame. Furthermore, in U.S. (Hurt et al. 2007) and Australian (Tiggemann and Kuring 2004; Tiggemann and Slater 2001; Tiggemann and Williams 2012) samples including both undergraduates and older women, body shame has been found to be a significant mediator between body surveillance and both disordered eating and depression.

A review of a wide variety of literature conducted by the American Psychological Association and including samples primarily, although not exclusively, from the United States concluded that being exposed to objectifying images of women, internalizing these images, and experiencing self-objectification are normative for young women today (APA 2007). However, a literature review spanning literature from the U.S., Australia, and many countries from Europe strongly concluded that the negative effects of self-objectification are serious (Moradi and Huang 2008). We propose that the effects of objectification could be conceptualized as somewhat traumatic. Indeed, some of the consequences of self-objectification are similar to the consequences of experiencing more overt forms of trauma such as sexual harassment or assault. For example, body shame has been found to be related to negative affect and depression in U.S. (Hurt et al. 2007) and Australian undergraduate women (Tiggemann and Kuring 2004; Tiggemann and Williams 2012). A review article covering literature from the many countries in Europe as well as both the U.S. and Australia, has concluded that depression commonly occurs after the experience of overt traumatic experiences which invoke fear or helplessness and involve the threat of bodily injury or death (Laugharne et al. 2010).

Self-harm involves deliberate harm to one’s body without the intent of suicide (Klonsky et al. 2003) and, although it is a symptom of borderline personality disorder (APA 2000), has been found to occur in non-clinical populations. One study utilizing male and female military recruits from the U.S. found that 4 % endorsed deliberately engaging in harming behavior (Klonsky et al. 2003). However, more recent research suggests that self-injury may be even more common. A meta-analysis including data from 20 countries showed that, in non-clinical populations, 12.2 % endorsed engaging in self-injurious behavior when asked with a single item, and 31.4 % indicated engaging in such behavior when multi-item behavioral measures were used (Muehlenkamp et al. 2012). Thus, many adolescents and young adults have engaged in this behavior. Data from high school students in the U.S. also indicate that the prevalence of self-harm is higher in women, and women are more likely to engage in behaviors such as cutting and scratching (Sornberger et al. 2012).

Self-harm has been explicitly theoretically linked to the experience of overtly traumatic experiences and seen as a way that individuals experiencing trauma can release emotion or re-enact the original trauma (Connors 1996). However, in a mixed gender Canadian college student sample, overt experiences of trauma did not differentiate those who self-injured from those who did not (Heath et al. 2008). Although it is not entirely clear what could precipitate the need to self-injure among women who have not experienced overt trauma, we propose that the commonplace negative consequences of self-objectification may be one precipitating factor. Self-harm may be both an expression of the negative affect associated with body shame as well as a way to punish bodies for not living up to the standards of body perfection that young women have seen in the media and subsequently internalized (Flett et al. 2012). One study using undergraduate women from the United States found that self-objectification had an indirect effect on self-harm through its relationship with negative body regard and depressive symptoms (Muehlenkamp et al. 2005). Another study using male and female undergraduates from the U.S. found a direct correlational relationship between engaging in self-harming behaviors and both surveillance and shame (Nelson and Muehlenkamp 2012).

Another variable that has been associated with trauma and may be linked to self-objectification is dissociation. Since self-objectification, or body surveillance, is considered to be a psychological distancing from one’s body (Calogero et al. 2005), it can be argued that women who self-objectify may also experience a level of detachment from their normal stream of consciousness. One potential mental consequence of this disconnection between oneself and one’s body is the development of dissociative tendencies (Murray and Fox 2005). Dissociation involves a period of time in which thoughts, feelings, and experiences are not integrated into one’s memory and everyday stream of consciousness the way they normally would be (Bernstein and Putnam 1986). Dissociation has been linked to self-reported accounts of physical abuse or punishment, sexual abuse, psychological abuse, neglect, and negative home atmosphere in research using U. S. samples (Chu and Dill 1990; Sanders and Giolas 1991; van der Kolk et al. 1991). It has been hypothesized that self-injury may be one mechanism to relieve the negative effects associated with dissociation (Connors 1996). Despite the importance of experiencing overt trauma in the development of dissociation, research conducted with adults in the United States has indicated that it does not seem to be necessary for dissociation to occur (Briere 2006). Given this, we propose that self-objectification may lead to dissociation in some individuals. Dissociation has been linked to depression (e.g., Maaranen et al. 2008 using a Finnish sample), which is one of the most common consequences of self-objectification as found in both adolescent and adult samples from the U.S. (Grabe et al. 2007; Szymanski and Henning 2007) and Australia (Tiggemann and Kuring 2004). Whether or not the depression seen as a consequence of self-objectification is mediated by dissociation was one question we sought to answer with the present study.

Dissociation may share a commonality with self-objectification in that women who engage in body surveillance tend to have a decreased awareness of their physical and emotional internal bodily states, a concept known as interoceptive awareness (Fredrickson and Roberts 1997). This has been found in college student samples of women from the U.S. (Myers and Crowther 2008; Tylka and Hill 2004) and with both male and female college students from Australia (Tiggemann and Kuring 2004). Studies conducted among female college students in the U.S. have found that low interoceptive awareness mediated the relationship between body surveillance and both disordered eating (Muehlenkamp and Saris-Baglama 2002; Myers and Crowther 2008) and depression (Peat and Muehlenkamp 2011). On the other hand, one study of both male and female adults conducted in the U.K. found that individuals who reported out-of-body experiences did not differ on surveillance and body shame from those who had not (Murray and Fox 2005). Thus, the relationship between dissociation and self-objectification is conceptually justified and supports an understanding of self-objectification as a somewhat traumatic experience. However, the existence and nature of the relationship has not been clearly established.

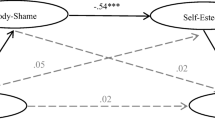

The goal of the current study was to investigate whether media internalization and self-objectification could be conceptualized as somewhat traumatic experiences by investigating their relationship to variables that have been more commonly viewed as consequences of trauma, namely dissociation and self-harm. This was done by testing a path model (see Fig. 1). Research undertaken with an Australian sample of women aged 20 to 84 indicated that self-objectification and the consequences thereof decreased over the course of the lifespan (Tiggemann and Lynch 2001). Given this, we chose to control for the effects of age on all the endogenous variables when testing our hypothesized model.

Path model of the relationships among the variables of interest, χ 2(7) = 5.35, p = .62; CFI = 1.00; RMSEA < .001. Standardized path coefficients are reported, and standard errors for the path coefficients are reported in parentheses. The effects of age on each of the endogenous variables were controlled for; as no significant relationships were found, we have not modeled these paths for the sake of readability. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001

Our model began with the internalization of media ideals. This variable was hypothesized to predict both body surveillance, an operationalization of self-objectification, (hypothesis 1) and body shame (hypothesis 2), connections that have been supported in previous research (e.g., Calogero et al. 2005; Calogero and Thompson 2009; Knauss et al. 2008). We also hypothesized that body surveillance would predict both body shame (hypothesis 3), as has been found in much prior research (e.g., Moradi et al. 2005; Tiggemann and Kuring 2004; Tylka and Hill 2004), and dissociation (hypothesis 4), a variable that has not been previously examined in the context of self-objectification. Given that body surveillance involves a disconnection from one’s body that could predispose an individual to experiencing additional symptoms of dissociation, we hypothesized a direct relationship between body surveillance and dissociation. We then hypothesized that depressive symptomatology would be predicted by both body shame (hypothesis 5; e.g., Hurt et al. 2007; Szymanski and Henning 2007) and dissociation (hypothesis 6; e.g., Maaranen et al. 2008). Finally, we hypothesized that engaging in self-harm behaviors would be predicted by both depression (hypothesis 7; e.g., Briere and Gil 1998; De Klerk et al. 2011) and dissociation (hypothesis 8; e.g., Gratz et al. 2002; Polk and Liss 2007; Tolmunen et al. 2008).

In addition to our hypotheses about the overall path model, we were interested in testing a number of specific indirect relationships among modeled variables in order to specifically determine whether both media ideals and body surveillance predicted clinical relevant variables through the mediating variables of body shame, dissociation, and depression. First, we tested whether self-objectification, operationalized as body surveillance, had an indirect effect on depression through dissociation (hypothesis 9), a relationship not previously studied. Given that surveillance is well known to have an effect on depression through the mediating variable of body shame (see Moradi and Huang 2008 for a review), we hoped to determine whether a secondary path could be delineated wherein surveillance may lead to depression due to the negative effects of dissociation.

We also tested two indirect effects that represented replications and extensions of relationships found in previous studies. The relationship between self-objectification and self-harm has been found to go through depression in one prior study conducted in the U. S. (Muehlenkamp et al. 2005). We sought to replicate this by testing the indirect effect of body surveillance on self-harm through body shame and depression (hypothesis 10). Finally, we sought to extend research on the predictors of self-harm by determining whether internalization of media ideals had an indirect effect on self-harm through surveillance, shame, and depression (hypothesis 11).

Method

Participants

One hundred and sixty women participated in this study. Participants ranged in age from 18 to 35 (M = 23.12, SD = 3.69, Median = 22, Mode = 21). Eleven percent of participants were high school graduates, 39 % had some college or an Associate’s degree, 25 % were college graduates, 13 % had some graduate school, 9 % had a master’s degree, and 2 % had a doctoral degree. Participants were primarily Caucasian (94 %) with an additional 1 % identifying themselves as African American, 1 % Asian, .5 % Latina, 1 % multiracial, and 2 % other. The breakdown of their self-identified socioeconomic status was as follows: 3 % poverty, 13 % working class, 57 % middle class, 26 % upper-middle class, and 1 % wealthy. Additionally, the majority of the sample identified as heterosexual (94 %), although 3 % identified as bisexual, 2 % as homosexual, and 1 % considered themselves “non-labeled.”

Procedure

Participants were recruited online using snowball sampling to complete an anonymous online survey through the SurveyGizmo website. Snowball sampling was begun by the researchers posting links to the survey as status updates on the social networking site Facebook on their pages. Two of the posters were faculty while the third poster was a senior undergraduate student; all were members of a psychology department that heavily uses facebook for communication. The survey was described as being about “the effects of women’s exposure to the media on their attitudes and behaviors” in these initial Facebook posts. The posts also included a request for people to share the link with other women they thought might be interested in the study and to re-post the link to the survey on Facebook and other social networks to which they belonged. Given this, it is unclear where, other than Facebook, the link to our survey was posted or whether all of the participants in this study were from the United States. Given that snowball recruitment was begun online by individuals in the U.S. with social networks dominated by others in the U.S., it is likely that the sample for the present study was comprised predominately by those from the United States. Recruitment messages specified that participants should be women over the age of 18.

When potential participants clicked on the survey link, they were taken to an informed consent page where they learned about the study. They were again informed about the general topic, told that the survey would take 20–30 min to complete, and were informed that the study had received IRB approval. As part of the consent page, participants were told that their responses would remain completely anonymous, that they could skip questions, and that they could terminate their session at any time. When participants finished the survey, they were taken to a debriefing page where they were given more information about the research questions guiding the study. Participants were also given contact information for the researchers and the chair of the IRB in case they had questions or concerns about the study.

Measures

Internalization of Media Ideals

The general internalization subscale of the Sociocultural Attitudes Towards Appearance Scale-3 (Thompson et al. 2004) was used to assess the extent to which participants internalized the ideal body image presented in the media (e.g., “I compare my body to the bodies of people who are on TV”). Participants responded to items on a scale ranging from 1 (definitely disagree) to 5 (definitely agree). Mean scores were calculated as long as participants did not have missing data on more than one item; no participants exceeded this criterion. Cronbach’s alpha in the original study was .93 and was .94 in the present study.

Self-objectification

The surveillance (e.g., “During the day, I think about how I look many times”) and body shame (e.g., “I feel ashamed of myself when I haven’t made the effort to look my best”) subscales of the Objectified Body Consciousness Scale (OBCS; McKinley and Hyde 1996) were used to assess the extent to which participants viewed their bodies as an outsider and the level of shame they experienced when their bodies did not conform to society’s standards. The control subscale of the OBCS was not included as it is traditionally used in relation to eating attitudes (e.g., Mazzeo et al. 2006), a construct we did not assess. Participants indicated their level of agreement with each statement on a scale from 1 (disagree strongly) to 6 (agree strongly); no “not applicable” option was given to participants. Mean scores for each subscale were calculated as long as participants did not have missing data on more than one item per scale, and scores were able to be calculated for all participants. Cronbach’s alpha in the original study was .79 for both the surveillance and body shame scales. The present study revealed Cronbach’s alphas of .87 for surveillance and .85 for shame.

Dissociation

Degree of dissociation was measured using the Dissociative Experiences Scale (Bernstein and Putnam 1986) which describes 28 situations that may happen in life and asks individuals to assign a percentage from 0 to 100 % in increments of 10 % for the frequency with which they experience each situation while they are not under the influence of drugs or alcohol (e.g., “Some people have the experience of driving a car and suddenly realizing that they don’t remember what has happened during all or part of the trip”). Mean scores were again calculated as long as participants did not exceed our missing data criterion of one missing item, and scores were able to be calculated for all participants. Cronbach’s alpha was .84 in the original study and .91 in the present study.

Depressive Symptomatology

The 20-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (Radloff 1977), which was designed for use with a general population, was used to assess the frequency of depressive symptoms that participants experienced in the previous week. Participants indicated the frequency with which each symptom was experienced on a scale ranging from 1 (rarely or none of the time) to 4 (most or all of the time; e.g., “I felt hopeless about the future.”). Sum scores were calculated for each participant. If a participant chose not to respond to an item, no numerical value for that item was included in the final score. Cronbach’s alpha was .80 in the original study and .94 in the present study.

Self-harm

The Deliberate Self-Harm Inventory (DSHI; Gratz 2001) was used to measure intentional, non-suicidal self-harm behaviors. As is standard with the DSHI, specific definitions for each type of self-harming behavior were provided, and it was specified in the overall instructions for this measure that behaviors not be suicidal in intent or accidental. Participants were given statements to which they responded yes or no (e.g., “Have you ever intentionally cut your wrist, arms, or other area(s) of your body (without intending to kill yourself)?”). If a participant chose not to respond to a particular item, it was assumed that they had not engaged in that type of self-harming behavior. The majority of the sample reported never having engaged in self-harming behaviors (69 %). Given this, we coded self-harm as a dichotomous variable where a score of one represented engaging in self-harm while a score of zero represented having never engaged in self-harm. Participants were also asked how often they had engaged in each type of self-harming behavior, if relevant.

Results

The means, standard deviations, and ranges for participants’ scores for all continuous variables are presented in Table 1. On average, participants had moderate levels of dissociation and depression. Thirty one percent of individuals scored in the clinical range for depression using a score of 16 or above as a marker (Breslau 1985). Twenty-six percent scored in the range for high dissociation using 15 as a cutoff (Foote et al. 2006) while 2.5 % had scores of 30 or above, an alternative suggestion for a marker of high dissociation (Carlson and Putnam 1993).

As stated above, 69 % of the sample reported never having engaged in self-harming behavior. Of those who did, 44 % reported engaging in only one type of self-harming behavior, 18 % reported engaging in two types, 20 % reported engaging in three types, and 18 % reported engaging in four or more types. The most common forms of self-harm were cutting (54 %) and scratching (36 %). Using the frequency categories employed by Heath et al. (2008), of those who reported how often they had engaged in self-harming behavior, 11 % reported doing so one time, 22 % reported doing so 2–4 times, 31 % reported doing so 5–10 times, 28 % reported doing so 11–50 times, 3 % reported doing so 51–100 times, and 6 % reported doing so more than 100 times.

Table 2 shows the correlations among the measured variables. All of the variables included in the hypothesized model were significantly positively intercorrelated with three exceptions. Media internalization was not significantly related to dissociation, and the dichotomized self-harm variable was not significantly correlated with either body surveillance or dissociation. We also looked at the correlations between age, a variable controlled for in our model, and the modeled variables. Age was significantly negatively correlated with all of the variables except for body shame and self-harm.

Prior to undertaking path analysis, we tested for potential problems with multicolinearity. Tolerance values ranged from .49 to .91; scores at or below .2 have been suggested as indicating multicolinearity (Menard 1995), and our scores were above this marker. Additionally, VIF levels ranged from 1.10 to 2.05; scores at or above 10 are suggestive of multicolinearity (Myers 1990), and our scores were below this level.

M-plus version 6.12 (Muthén and Muthén 1998, 2010) with weighted least squares estimation was used to test all hypotheses. The hypothesized model had good fit, χ 2(7) = 5.35, p = .62; CFI = 1.00; RMSEA < .001. Age was not a significant predictor of any of the endogenous variables. All hypothesized paths, with the exception of the path from dissociation to self-harm, were statistically significant and are provided with their standard errors in Fig. 1. Thus, hypotheses 1 through 7 were supported, but hypothesis 8 was not. This model accounted for 48 % of the variance in surveillance, 38 % in shame, 5 % in dissociation, 21 % in depressive symptomatology, and 13 % in self-harm.

In addition to testing the fit of the overall model, we also had hypotheses about specific indirect effects. First, we tested whether dissociation mediated the relationship between body surveillance and depression (hypothesis 9). While this result did not meet traditional standards for statistical significance, the data indicated that dissociation may mediate the relationship between surveillance and depression, z = 1.73, p = .08. Next, we tested the indirect effect of surveillance on self-harm through both body shame and depression (surveillance to shame to depression to harm; hypothesis 10). This indirect effect was statistically significant, z = 2.59, p = .01. Finally, we tested the indirect effect of media internalization on self-harm through surveillance, shame, and depression (internalization to surveillance to shame to depression to harm; hypothesis 11) and found it to be significant, z = 2.47, p = .01.

Discussion

The goal of this study was to determine whether media internalization and self-objectification could be conceptualized as somewhat traumatic by testing their relationships to dissociation and self-harm, variables that have been conceptualized as consequences of trauma (e.g., Connors 1996). Our model showed good fit to the data, and all of the hypothesized paths, except the path between dissociation and self-harm, were significant. Our model replicated findings from previous research conducted on college women in both the U.S. (Aubrey 2006a, b; Moradi et al. 2005) and the U. K. (Calogero and Thompson 2009) as well as with adolescents in Switzerland (Knauss et al. 2008) that has shown that internalization of media ideals can lead to self-objectification, in the form of surveillance and shame (see Moradi and Huang 2008 for a review). Our model also replicated the frequently found relationship in which body surveillance is a predictor of body shame (e.g., Chen and Russo 2010, with U.S. college women; Tiggemann and Williams 2012, with Australian college women). Finally, we replicated the finding that body shame mediated the relationship between surveillance and depression (e.g., Hurt et al. 2007, with U.S. college women; Tiggemann and Kuring 2004, with Australian college students). Although our sample was limited to women aged 35 and younger, these relationships have been seen in women of all ages (e.g., Tiggemann and Lynch 2001, research conducted in Australia).

The results confirmed our hypothesis that body surveillance was related to dissociation and, as such, may be a precursor to more generalized dissociative experiences. Furthermore, our hypothesis that body surveillance would have an indirect effect on depression through dissociation received some support, although the finding did not meet traditional standards for statistical significance. When a woman takes a third person perspective on her body, she must actually step out of her body which puts her at risk for feelings of dissociation and the negative consequences of dissociative experiences. Dissociation may be related to low interroceptive awareness, a variable that has been linked to self-objectification among undergraduate women in the U.S. (e.g., Peat and Muehlenkamp 2011) but was not measured as part of the current study. Our results are in contrast to those from one study conducted in the U. K. that found no difference in body surveillance between male and female adults who reported out-of-body experiences and those who did not (Murray and Fox 2005). Out-of-body experiences, however, represent an extreme form of dissociation and may have different precursors than types of dissociation assessed in the current study. The relationship between body surveillance and dissociation is potentially important for understanding the psychological consequences of self-objectification. Although the relationship between body surveillance and depression has been well established, the depressing effects of body surveillance are generally conceptualized as going through body shame (see Moradi and Huang 2008 for a review). This study indicates that dissociation may be a secondary pathway through which the negative effects of body surveillance may occur.

This model also included self-harm as a potential distal outcome of self-objectification. Self-objectification and self-harm have been found to be linked before, both directly (Nelson and Muehlenkamp 2012) and indirectly through negative body regard and depression (Muehlenkamp et al. 2005). Our results are consistent with the findings from these studies conducted on undergraduate women and men in the United States. We found that body surveillance had a significant indirect effect on self-harm through body shame and depression. We also found that media internalization had a significant indirect effect on self-harm through body surveillance, body shame, and depression. Our data extends these findings by finding them among a slightly older, non-predominately undergraduate sample. Self-harming behavior has been conceptualized as a response to unbearable negative emotional affect (Gratz 2007), and data from people in the United States who self-injure suggests that this is one of the most common reasons for engaging in this behavior (Briere and Gil 1998; Polk and Liss 2009). Our data suggest that one source of the negative affect that can lead to self-harming behavior is a sense of shame about one’s body that stems from internalizing media messages about beauty ideals and engaging in habitual self-monitoring or body surveillance.

Both dissociation and self-harm behaviors are generally thought of as consequences of psychological trauma (e.g., Connors 1996), and this has been supported, for example, with research from a sample of U.S. adolescents (Sanders and Giolas 1991). Nevertheless, it is clear that direct physical or sexual abuse need not have happened for these psychological outcomes to occur as shown, for example, with research conducted with Canadian college students (Heath et al. 2008) as well as with a randomly selected nationally recruited sample from the U.S. (Briere 2006). Our study supports the conceptualization of media internalization and self-objectification as somewhat traumatic experiences. Although media internalization and self-objectification are not typically conceptualized within the trauma literature, the constant media focus on objectified images of women and an unrealistic and often unattainable body ideal (Sypeck et al. 2004) could be understood as a type of insidious trauma (Root 1992). Insidious trauma shapes one’s world view and is associated with being a member of a social group that is devalued (Root 1992). Women, as a social group, are displayed in devalued, objectified, and sexualized ways (see APA 2007; Conley and Ramsey 2011), and our data suggest that the effects of this may be somewhat traumatic.

Similarly, researchers have examined microaggressions, which are common experiences, either intentional or unintentional, that communicate a hostile or derogatory view of an oppressed or marginalized group (Sue 2010). A taxonomy of gender microaggressions has been proposed (Sue and Capodilupo 2008), and sexual objectification was found to be the one most commonly reported in a qualitative study conducted in the U. S. with both undergraduates and community members (Capodilupo et al. 2010). Our data suggest that the psychological consequences of experiencing gender microaggressions, in the form of objectification and self-objectification, may be similar to the consequences of experiencing more direct forms of trauma. The conceptual link between self-objectification, trauma, and self-harm have been made before. For example, Shaw (2002) suggested that self-harm could be thought of as a physical replication of the cultural objectification that women encounter.

Individuals may be at an even greater risk of these negative consequences of self-objectification and dissociation if they have had prior direct trauma experiences including sexual or physical abuse, variables we did not assess in the current study. Sexual abuse and sexual victimization have been found to predict negative attitudes about one’s body in a U.S. sample of female sexual abuse survivors (Wenninger and Heiman 1998). Kearney-Cooke and Striegel-Moore (1994) suggested that abuse victims see their bodies as a source of vulnerability and shame and may view their bodies as deficient. This seems to parallel the experiences of women who feel they do not live up to cultural standards and begin to self-objectify. Thus, trauma survivors may be at an increased risk of self-objectifying, dissociating, and developing maladaptive behaviors. Future research should examine the interplay between more direct forms of trauma, insidious trauma, self-objectification, and negative outcomes including depression, dissociation, and self-harm.

The generalizability of our results is limited by the homogenous nature of our sample. Our participants primarily self-identified as Caucasian, heterosexual, and middle or upper-middle class. The relationships among these variables may be different in women from different social groups. We did, however, include participants who ranged in age from 18 to 35, giving us some diversity in terms of this demographic variable. In our study, the covariate of age was not significant, indicating that age did not significantly predict any of the endogenous variables in our model. Nevertheless, it may well be the case that the modeled relationships work differently for older women than for younger women given that research conducted in Australia with women ranging in age from 20 to 84 has suggested that the consequences of objectification decrease as women age (Tiggemann and Lynch 2001). The mean age of our participants was 23, so the results of this study should be generalized to older women cautiously. Given this, future research should explicitly examine the nature of these relationships with an older adult sample. Additionally, although this was a non-clinically recruited sample, we did not specifically assess whether participants had been diagnosed with a clinical disorder.

It should also be noted that our data was collected online through postings made on Facebook by the authors and links to the survey shared through snowball sampling. Thus, our participants were comfortable online and likely had some interest in the topics under investigation. Furthermore, we did not collect information from participants about citizenship or country of origin. This coupled with our use of snowball sampling and an anonymous survey means that we cannot be certain the extent to which our sample was comprised of those from the U.S., something research should look at in the future. Finally, our path model specified relationships in a specific direction based on theory, but some of the relationships (such as that between body shame and depression) could, however, work in the other direction (e.g., more depressed participants feel more body shame). Longitudinal and experimental research would be needed to fully understand the directionality of the hypothesized relationships.

Eating attitudes and behaviors were not a focus in this study, although they have been shown to be linked to self-harming behavior in research on women with eating disorders conducted in Belgium (Claes et al. 2012; Muehlenkamp et al. 2011) and have been widely researched within the self-objectification literature (see Moradi and Huang 2008 for a review). Research has found that many of the variables in our study are also elevated among women who have been diagnosed with eating disorders. These include media internalization (Calogero et al. 2005 from the U.S) and dissociation (Schumaker et al. 1995 from Australia; Waller et al. 2001 from the U.K.). Furthermore, self-harm has been linked to negative eating attitudes among both college students in the U. K. (Mahadevan et al. 2010) and high school students in Canada (Ross et al. 2009). Thus, future research would benefit from including measures of disordered eating. Furthermore, low interoceptive awareness is conceptually related to dissociation and has been linked with disordered eating and depression in U.S. undergraduate samples (Muehlenkamp and Saris-Baglama 2002; Myers and Crowther 2008; Peat and Muehlenkamp 2011) and may be a variable of interest for future research in this area. Finally, it may be useful to better untangle whether exposure to unrealistic media images is sufficient for these negative effects to occur or whether it is the internalization of these ideals that is necessary.

Clinicians working with young women who engage in self-harm behaviors would be well served to include the negative effects of media internalization and self-objectification into their case formulations. Including an assessment of media internalization as well as the extent of body surveillance and shame could assist clinicians in better understanding whether symptoms of depression and self-harm experienced by their clients may partially stem from these commonly experienced precursors. Such assessments could be included along with those for more direct forms of trauma and may provide some insight into the causes of negative affect among young women who do not report a history of direct trauma. Furthermore, the relationship between body surveillance and dissociation is important for clinicians to understand. A great many women are potentially at risk for experiencing dissociation, and the negative consequences thereof, due to the everyday, normative experience of body surveillance. Self-harming behavior may be more commonly experienced among young women than was previously understood (see Kerr et al. 2010 for a review), and traditional risk factors such as direct trauma do not sufficiently predict engaging in these behaviors as found, for example, in a study of Canadian high school students (Heath et al. 2008). All women, however, are at risk for experiencing self-objectification as objectified images of women are a common part of our cultural landscape. Clinicians can assist women in developing the tools they need to fight the internalization of these media ideals and the subsequent experience of self-objectification. In doing so they may be able to help relieve symptoms of dissociation, depression, and self-harm.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed., text rev.). Washington, DC: Author.

American Psychological Association & Task Force on the Sexualization of Girls. (2007). Report of the APA task force on the sexualization of girls. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Retrieved from www.apa.org/pi/women/programs/girls/report.aspx.

Aubrey, J. S. (2006a). Effects of sexually objectifying media on self-objectification and body surveillance in undergraduates: Results of a 2-year panel study. Journal of Communications, 56, 366–386. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2006.00024.x.

Aubrey, J. S. (2006b). Exposure to sexually objectifying media and body self-perceptions among college women: An examination of the selective exposure hypothesis and the role of moderating variables. Sex Roles, 55, 159–172. doi:10.1007/s11199-006-9070-7.

Bernstein, E. M., & Putnam, F. W. (1986). Development, reliability, and validity of a dissociation scale. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 174, 727–735. doi:10.1097/00005053-198612000-00004.

Breslau, N. (1985). Depressive symptoms, major depression, and generalized anxiety: A comparison of self-reports on CES-D and results from diagnostic interviews. Psychiatry Research, 15, 219–229. doi:10.1016/0165-1781(85)90079-4.

Briere, J. (2006). Dissociative symptoms and trauma exposure: Specificity, affect dysregulation, and posttraumatic stress. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 194, 78–82. doi:10.1097/01.nmd.0000198139.47371.54.

Briere, J., & Gil, E. (1998). Self-mutilation in clinical and general population samples: Prevalence, correlates, and functions. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 68, 427–432. doi:10.1037/h0080369.

Calogero, R. M., & Thompson, J. K. (2009). Potential implications of the objectification of women’s bodies for women’s sexual satisfaction. Body Image, 6, 145–148. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2009.01.001.

Calogero, R. M., Davis, W. N., & Thompson, J. K. (2005). The role of self-objectification in the experience of women with eating disorders. Sex Roles, 52, 43–50. doi:10.1007/s11199005-11929.

Capodilupo, C. M., Nadal, K. L., Corman, L., Hamit, S., Lyons, O. B., & Weinberg, A. (2010). The manifestation of gender microaggressions. In D. W. Sue (Ed.), Microaggressions and marginality: Manifestation, dynamics, and impact (pp. 193–216). Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons.

Carlson, E. B., & Putnam, F. W. (1993). An update on the dissociative experiences scale. Dissociation, 6, 16–26.

Chen, F. F., & Russo, N. F. (2010). Measurement invariance and the role of body consciousness in depressive symptoms. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 34, 405–417. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.2010.01585.x.

Chu, J. A., & Dill, D. L. (1990). Dissociative symptoms in relation to childhood physical and sexual abuse. American Journal of Psychiatry, 147, 887–892.

Claes, L., Soenens, B., Vansteenkiste, M., & Vandereycken, W. (2012). The scars of the inner critic: Perfectionism and nonsuicidal self-injury in eating disorders. European Eating Disorders Review, 20, 196–202. doi:10.1002/erv.1158.

Conley, T. D., & Ramsey, L. R. (2011). Killing us softly? Investigating portrayals of women and men in contemporary magazine advertisements. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 35, 469–478. doi:10.1177/0361684311413383.

Connors, R. (1996). Self-injury in trauma survivors: 1. Functions and meanings. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 66, 197–206. doi:10.1037/h0080171.

De Klerk, S., van Noorden, M. S., van Giezen, A. E., Spinhoven, P., den Hollander-Gijsman, M. E., Gittay, E. J., et al. (2011). Prevalence and correlates of lifetime deliberate self-harm and suicidal ideation in naturalistic outpatients: The Lieden routine outcome monitoring study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 133, 257–264. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2011.03.021.

Flett, G. L., Goldstein, A. L., Hewitt, P. L., & Wekerle, C. (2012). Predictors of deliberate self-harm behavior among emerging adolescents: An initial test of a self-punitiveness model. Current Psychology: Research & Reviews, 31, 49–64. doi:10.1007/s12144-012-9130-9.

Fliege, H., Lee, J.-R., Grimm, A., & Klapp, B. F. (2009). Risk factors and correlates of deliberate self-harm behavior: A systematic review. Journal of psychosomatic Research, 66, 477–493. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2008.10.013.

Foote, B., Smolin, Y., Kaplan, M., Legatt, M. E., & Lipschitz, D. (2006). Prevalence of dissociative disorders in psychiatric outpatients. American Journal of Psychiatry, 163, 623–629. doi:10.1542/peds.103.3.e36.

Fredrickson, B. L., & Roberts, T.-A. (1997). Objectification theory: Toward understanding women’s lived experiences and mental health risks. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21, 173–206. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997.tb00108.x.

Grabe, S., Hyde, J. S., & Lindberg, S. M. (2007). Body objectification and depression in adolescents: The role of gender, shame, and rumination. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 31, 164–175. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.2007.00350.x.

Gratz, K. L. (2001). Measurement of deliberate self-harm: Preliminary data on the Deliberate self-harm inventory. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 23, 253–263. doi:10.1023/A:1012779403943.

Gratz, K. L. (2007). Targeting emotion dysregulation in the treatment of self-injury. Journal of Clinical Psychology: In Session, 63, 1091–1103. doi:10.1002/jclp.20417.

Gratz, K. L., Conrad, S. D., & Roemer, L. (2002). Risk factors for deliberate self-harm among college students. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 72, 128–140. doi:10.1037/0002-9432.72.1.128.

Heath, N. L., Toste, J. R., Nedecheva, T., & Charlebois, A. (2008). An examination of nonsuicidal self-injury among college students. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 30, 137–156.

Hurt, M. M., Nelson, J. A., Turner, D. T., Haines, M. E., Ramsey, L. R., Erchull, M. J., et al. (2007). Feminism: What is it good for? Feminine norms and objectification as the link between feminist identity and clinically relevant outcomes. Sex Roles, 57, 355–363. doi:10.1007/s11199-007-9272-7.

Kearney-Cooke, A., & Striegel-Moore, R. H. (1994). Treatment of childhood sexual abuse in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: A feminist psychodynamic approach. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 15, 305–319. doi:10.1002/eat.2260150402.

Kerr, P. L., Muehlenkamp, J. J., & Turner, J. M. (2010). Nonsuicidal self injury: A review of current research for family medicine and primary care physicians. The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, 23, 241–259. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2010.02.090110.

Klonsky, E. D., Oltmanns, T. F., & Turkheimer, E. (2003). Deliberate self-harm in a nonclinical population: Prevalence and psychological correlates. American Journal of Psychiatry, 160, 1501–1508. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.160.8.1501.

Knauss, C., Paxton, S. J., & Alsaker, F. D. (2008). Body dissatisfaction in adolescent boys and girls: Objectified body consciousness, internalization of the media body ideal and perceived pressure from media. Sex Roles, 59, 633–643. doi:10.1007/s11199-008-9474-7.

Laugharne, J., Lillee, A., & Janca, A. (2010). Role of psychological trauma in the cause and treatment of anxiety and depressive disorders. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 23, 25–29. doi:10.1097/YCO.0b013e3283345dc5.

Maaranen, P., Tanskanen, A., Hintikka, J., Honkalampi, K., Haatainen, K., Koivumaa-Honkanen, H., et al. (2008). The course of dissociation in the general population: A 3-year follow-up study. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 49, 269–274. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2007.04.010.

Mahadevan, S., Hawton, K., & Casey, D. (2010). Deliberate self-harm in Oxford University students, 1993–2005: A descriptive and case–control study. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 45, 211–219. doi:10.1007/s00127-009-0057-x.

Mazzeo, S. E., Trace, S. E., Mitchell, K. S., & Gow, R. W. (2006). Effects of a reality TV cosmetic surgery makeover program on eating disordered attitudes and behaviors. Eating Behaviors, 8, 390–397. doi:10.1016/j.eatbeh.2006.11.016.

McKinley, N. M., & Hyde, J. S. (1996). The objectified body consciousness scale. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 20, 181–215. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.1996.tb00467.x.

Menard, S. (1995). Applied logistic regression analysis. Sage university paper series on quantitative applications in the social sciences, 07–106. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Moradi, B., Dirks, D., & Matteson, A. V. (2005). Roles of sexual objectification experiences and internalization of standards of beauty in eating disorder symptomatology: A test and extension of objectification theory. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52, 420–428. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.52.3.420.

Moradi, B., & Huang, Y.-P. (2008). Objectification theory and psychology of women: A decade of advances and future directions. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 32, 377–398. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.2008.00452.x.

Muehlenkamp, J. J., Claes, L., Havertape, L., & Plener, P. L. (2012). International prevalence of adolescent non-suicidal self-injury and deliberate self-harm. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 6, 1–9. doi:10.1186/1753-2000-6-10.

Muehlenkamp, J. J., Claes, L., Smits, D., Peat, C. M., & Vendereycken, W. (2011). Non-suicidal self-injury in eating disordered patients: A test of a conceptual model. Psychiatry Research, 188, 102–108. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2010.12.023.

Muehlenkamp, J. J., & Saris-Baglama, R. (2002). Self-objectification and its psychological outcomes for college women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 26, 371–379. doi:10.1111/1471-6402.t01-1-00076.

Muehlenkamp, J. J., Swanson, J. D., & Brausch, A. M. (2005). Self-objectification, risk taking, and self-harm in college women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 29, 24–32. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.2005.00164.x.

Murray, C. D., & Fox, J. (2005). Dissociational body experiences: Differences between respondents with and without prior out-of-body experiences. British Journal of Psychology, 96, 441–456. doi:10.1348/000712605X49169.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998–2010). Mplus user’s guide (6th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.

Myers, R. (1990). Classical and modern regression with applications (2nd ed.). Boston: Duxbury.

Myers, T. A., & Crowther, J. H. (2008). Is self-objectification related to interoceptive awareness? An examination of potential mediating pathways to disordered eating attitudes. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 32, 172–180. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.2008.00421.x.

Nelson, A., & Muehlenkamp, J. J. (2012). Body attitudes and objectification in non-suicidal self-injury: Comparing males and females. Archives of Suicide Research, 16, 1–12. doi:10.1080/13811118.2012.640578.

Peat, C. M., & Muehlenkamp, J. J. (2011). Self-objectification, disordered eating, and depression: A test of meditational pathways. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 35, 441–450. doi:10.1177/0361684311400389.

Polk, E., & Liss, M. (2007). Psychological characteristics of self-injurious behavior. Personality and Individual Differences, 43, 567–577. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2007.01.003.

Polk, E., & Liss, M. (2009). Exploring the motivations behind self-injury. Counseling Psychology Quarterly, 22, 233–241. doi:10.1080/09515070903216911.

Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385–401. doi:10.1177/014662167700100306.

Root, M. P. P. (1992). Reconstructing the impact of trauma on personality. In L. S. Brown & M. Ballou (Eds.), Personality and psychopathology: Feminist reappraisals (pp. 229–265). New York: The Guildford Press.

Ross, S., Heath, N. L., & Toste, J. R. (2009). Non-suicidal self-injury and eating pathology in high school students. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 79, 83–92. doi:10.1037/a0014826.

Sanders, B., & Giolas, M. H. (1991). Dissociation and childhood trauma in psychologically disturbed adolescents. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 148, 50–54. doi:10.1111/j.1744-6163.1991.tb00350.x.

Schumaker, J. F., Warren, W., Carr, S., Schreiber, G. S., & Jackson, C. (1995). Dissociation and depression in eating disorders. Social Behavior and Personality, 23, 53–57. doi:10.2224/sbp.1995.23.1.53.

Shaw, S. N. (2002). Shifting conversations on girls’ and women’s self-injury: An analysis of the clinical literature in historical context. Feminism & Psychology, 12, 191–219. doi:10.1177/0959353502012002010.

Sornberger, M. J., Heath, N. L., Toste, J. R., & McLouth, R. (2012). Nonsuicidal self-injury and gender: Patterns of prevalence, methods, and locations among adolescents. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 42, 266–278. doi:10.1111/j.1943-278X.2012.00088.x.

Sue, D. W. (2010). Microaggressions in everyday life: Race, gender, and sexual orientation. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons.

Sue, D. W., & Capodilupo, C. M. (2008). Racial, gender, and sexual orientation microaggressions: Implications for counseling and psychotherapy. In D. W. Sue & D. Sue (Eds.), Counseling the culturally diverse: Theory and practice (5th ed., pp. 105–130). Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons.

Sypeck, M. F., Gray, J. J., & Ahrens, A. H. (2004). No longer just a pretty face: Fashion magazines’ depictions of ideal female beauty from 1959–1999. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 36, 342–347. doi:10.1002/eat.20039.

Szymanski, D. M., & Henning, S. L. (2007). The role of self-objectification in women’s depression: A test of objectification theory. Sex Roles, 56, 45–53. doi:10.1007/s11199-006-9147-3.

Thompson, J. K., van den Berg, P., Roehrig, M., Guarda, A. S., & Heinberg, L. J. (2004). The Sociocultural Attitudes Towards Appearance Scale-3 (SATAQ-3): Development and validation. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 35, 293–304. doi:10.1002/eat.10257.

Tiggemann, M., & Kuring, J. K. (2004). The role of self-objectification in disordered eating and depressed mood. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 43, 299–311. doi:10.1348/0144665031752925.

Tiggemann, M., & Lynch, J. E. (2001). Body image across the life span in adult women: The role of self-objectification. Developmental Psychology, 37, 243–252. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.37.2.243.

Tiggemann, M., & Slater, A. (2001). A test of objectification theory in former dancers and non dancers. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 25, 57–64. doi:10.1111/1471-6402.00007.

Tiggemann, M., & Williams, E. (2012). The role of self-objectification in disordered eating, depressed mood, and sexual functioning among women: A comprehensive test of objectification theory. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 36, 66–75. doi:10.1177/0361684311420250.

Tolmunen, T., Rissanen, M. L., Hintikka, J., Maaranen, P., Honkalampi, K., Kylma, J., et al. (2008). Dissociation, self-cutting, and other self-harm behavior in a general population of Finnish adolescents. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 196, 768–771. doi:10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181879e11.

Tylka, T. L., & Hill, M. S. (2004). Objectification theory as it relates to disordered eating among college women. Sex Roles, 51, 719–730. doi:10.1007/s11199-004-0721-2.

van der Kolk, B. A., Perry, J. C., & Herman, J. L. (1991). Childhood origins of self-destructive behaviors. American Journal of Psychiatry, 148, 1665–1671.

Waller, G., Ohanian, V., Meyer, C., Everill, J., & Rouse, H. (2001). The utility of dimensional and categorical approaches to understanding dissociation in eating disorders. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 40, 387–397. doi:10.1348/014466501163878.

Wenninger, K., & Heiman, J. R. (1998). Relating body image to psychological and sexual functioning in child sexual abuse survivors. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 11, 543–562. doi:10.1023/A:1024408830159.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Erchull, M.J., Liss, M. & Lichiello, S. Extending the Negative Consequences of Media Internalization and Self-Objectification to Dissociation and Self-Harm. Sex Roles 69, 583–593 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-013-0326-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-013-0326-8