Abstract

Recently, constructs related to behaving authentically in relationships have been linked to self-esteem and depression. The current study aimed to fill an important gap in the literature by identifying several social-environmental factors that may be associated with dispositional authenticity—“the unobstructed operation of one’s core or true self in one’s daily enterprise” (Kernis and Goldman 2006, p. 294)—and determining whether these factors differ for males and females. Theoretical links between dispositional authenticity and perceptions of close relationship partners as more authentic and egalitarian were empirically examined. This study expanded on relational authenticity research, which has linked behaving authentically in relationships to higher self-esteem and less depressive symptomatology, to address whether females are more likely than males to display dispositional authenticity, as well as to report low self-esteem and depression when they engage in inauthenticity. Participants were 470 U.S. college students (318 female) who were recruited from colleges across the country (41 % from a liberal arts school, 31 % from a large public university) and completed questionnaires online. Path analysis indicated that both genders report more authenticity when they perceived their mothers to be more authentic; authenticity, in turn, was related to fewer depressive symptoms and greater self-esteem for both genders. For females only, authenticity was also positively related to the perceived authenticity of important nonparental adults, and a more traditional gender ideology was related to higher self-esteem; for males only, depressive symptoms were positively related to a more traditional gender ideology. Implications and suggestions for future research are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Recent empirical and theoretical research has highlighted that a commitment to live authentically, through communicating and acting in ways that genuinely represent oneself, may protect against mental health problems (e.g., Kernis and Goldman 2006; Wood et al. 2008). Early research posited that authenticity was most important for the mental health of females due to gender expectations to be self-sacrificing and dependent compared to male gender expectations to be independent and assertive (Gilligan 1982; Miller 1986). Although recent studies have demonstrated that authenticity in relationships and well-being are linked for both males and females (e.g., Theran 2011), gender differences in dispositional authenticity, or “the unobstructed operation of one’s core or true self in one’s daily enterprise” (Kernis and Goldman 2006, p. 294), have not yet been examined. Furthermore, social-environmental factors may differentially predict whether males and females are authentic. The current study aimed to increase our understanding of authenticity in keeping with efforts to promote mental health, and elucidate associations of perceptions of others’ behavior and gendered expectations with male and female authenticity. Understanding these influences may help delineate how to promote authenticity, and ultimately the mental health of youth.

Several studies have advanced our understanding of how authenticity across relationships as well as in specific relationships (e.g., with parents, peers) is linked with mental health outcomes. Although these studies have been conducted almost exclusively in the United States (and all studies discussed were conducted in the United States unless otherwise stated), these relations have been demonstrated in samples that are diverse in terms of age and ethnicity, including boys and girls from middle school to college and samples that include students from a range of ethnic backgrounds (e.g., Harter et al. 1996; Impett et al. 2008; Theran 2010; Theran 2011). However, to better understand the association between authenticity and mental health, researchers have begun studying trait-like or dispositional differences in authenticity in U.S. and U.K. samples (Kernis and Goldman 2006; Wood et al. 2008). Past research has demonstrated a link between greater dispositional authenticity and self-esteem as well as overall well-being in samples of U.S. and U.K. undergraduate and diverse community samples (e.g., Goldman and Kernis 2002; Kernis and Goldman 2006; Wood et al. 2008). In addition, work on authenticity in relationships of participants diverse in age and ethnicity has emphasized the importance of considering gender differences (e.g., Gratch et al. 1995; Harper et al. 2006; Theran 2011). The current self-report study contributes needed research on potential gender differences in dispositional authenticity and its relation to self-esteem and depression. Furthermore, this study explored the contributing role of perceived social-environmental factors to dispositional authenticity, specifically whether perceiving close others as authentic and having egalitarian gender ideologies predicts greater dispositional authenticity. We proposed that individuals would be encouraged to employ their true selves when they perceived their close others as authentic and holding fewer gender-stereotyped views, but examined whether these associations differed based on gender. Taken together, the current study aimed to fill an important gap in the literature by increasing our understanding of gender differences in rates and predictors of dispositional authenticity, an issue of particular importance due to the mental health consequences of inauthentic tendencies.

Gender and Mental Health

Past work examining relational authenticity in demographically diverse samples has often emphasized the importance of authenticity for females in particular (e.g., Impett et al. 2008; Jack and Dill 1992; Theran 2009), in part because of well-documented gender differences in mental health, particularly depression and self-esteem. Beginning in adolescence, females report greater depressive symptomatology and lower self-esteem than males (Chubb et al. 1997; see Nolen-Hoeksema 1987 for a review). It is estimated (based on a longitudinal study in New Zealand) that by age 21, more than 40 % of females will have experienced a depressive episode (Hankin et al. 1998). In keeping with past studies (e.g., Theran 2010), we examined both depressive symptoms and self-esteem as measures of mental health. Although the two dimensions are conceptually and empirically linked, especially for women (Altman and Wittenborn 1980; Tashakkori and Thompson 1989), the absence of one does not imply the presence of the other and both are considered important indicators of mental health (e.g., Shrier et al. 2001). Therefore, both depressive symptoms and self-esteem were included as measures of mental health, although they were examined in analytic models together to account for the association between them.

Many scholars argue that these gender differences in rates of mental health problems are due in large part to societal pressures and expectations. Feminist theory posits that females are expected to adhere to standards that emphasize female dependence and submissiveness (Gilligan 1982; Miller 1986) while they are simultaneously facing conflicting pressure to succeed in domains that emphasize ambition and hard work (Hinshaw and Kranz 2009; Pipher 1994). Contrastingly, typical male gender roles emphasize independence, assertiveness, and ambition (Gilligan 1982; Miller 1986). Brown (1994) asserts that societies’ tendency to idealize male gender roles and devalue typical female gender roles contributes to increased negative mental health outcomes for females. Supporting this theory, Yakushko (2007) demonstrated that U.S. women 18 and older with traditional gender values scored lower on measures of psychological well-being. Of course, there are cultural differences in the extent to which male and female roles are valued differently (e.g., Block 1973; Denner and Dunbar 2004); of note, in the authenticity articles reviewed, unless otherwise specified, the participants were predominately Caucasian adolescents attending school in the United States.

As reviewed, feminist theory and current research provide reasons to expect that female college students will be more likely to be dispositionally inauthentic than male students. However, it is crucial to recognize that many males also struggle with low self-esteem and depression due in part to gender roles (see Good and Mintz 1990 for evidence in a sample of U.S. undergraduate males). Aspects of gender roles that males frequently experience conflict conforming to include: limiting the sharing of one’s own emotions, feeling uncomfortable with the emotional expressiveness of others, and restricting affectionate behavior with others (O’Neil et al. 1986). Indeed, research suggests that these aspects of gender role conflict, among others, predict depressive symptomatology in males. It has even been argued that violating gender roles has greater psychological consequences for males than females (Pleck 1995). In addition, evidence for gender differences in constructs related to relational authenticity has been inconsistent. Some studies suggest that males are actually more likely than females to engage in self-silencing behaviors (Gratch et al. 1995; Harper et al. 2006). Other studies have found that the nature of the gender differences depends on the particular sub-component or relational context of authentic behavior under investigation. For instance, there is evidence that females are more authentic with best friends, whereas males are more authentic with fathers (Theran 2011). In addition, two studies have found few gender differences in self-silencing or relational authenticity overall, but have found gender differences in some of the subscales, with females more often (but not always) displaying more silencing or less authenticity (e.g., Cramer and Thoms 2003; Hart and Thompson 1996 in a diverse sample of Canadian adolescents; Smolak and Munstertieger 2002). However, it is possible that gender differences in the direction that theory would predict (i.e., with females displaying less authenticity and being more affected by it in terms of mental health) will be most evident when dispositional or trait-like authenticity is examined rather than relationship-specific authenticity.

Inauthentic Behavior and its Mental Health Consequences

Societal pressures often encourage gender-stereotyped behavior, which can theoretically encourage inauthentic behavior (e.g., Harper et al. 2006; Impett et al. 2008). Recent research has emphasized that individuals suffer when they act in inauthentic ways. Inauthentic behaviors have been termed “false self behavior,” (Harter 1997, p. 82), “silencing the self,” (Jack and Dill 1992, p. 98), or “inauthentic self in relationships,” (Tolman and Porche 2000, p. 367). These terms address the incongruence between what a person thinks and how s/he behaves in a relationship (Impett et al. 2008), with a greater discrepancy reflecting greater relational inauthenticity.

Past research has emphasized self-silencing and relational inauthenticity as processes particularly common and detrimental for females that result in increased depressive symptomatology beginning in adolescence (e.g., Jack 1991; Impett et al. 2008; Theran 2009). Indeed, there is evidence that, for early adolescent girls (of Caucasian and Latina backgrounds), comfort speaking honestly about their thoughts in relationships relates to increases in self-esteem over time; interestingly, girls who report greater increases in relational authenticity over time also show an increase in self-esteem (Impett et al. 2008). However, recent research with middle school (Theran 2011), high school (Harper et al. 2006), and college students (Cramer and Thoms 2003 in a Canadian sample; Gratch et al. 1995 in a racially/ethnically diverse sample) has demonstrated the implications of self-silencing and relational inauthenticity for males as well. These studies indicate that overall, males self-silence or engage in relationally inauthentic behavior to a similar extent as or even greater extent than females, with the same mental health repercussions. Similarly, for both male and female adolescents (of diverse ethnic backgrounds), “voice,” or a willingness to share one’s true opinions, has been positively linked with relational self-esteem (Harter et al. 1998) and relational authenticity with parents is predictive of depressive symptomatology (Theran 2011).

Though there is a growing body of research on gender, mental health, and relational authenticity, gender differences in dispositional authenticity are not well understood. Whereas relational authenticity is how one’s behavior in close relationships reflects his/her true thoughts and feelings, dispositional authenticity is the trait-like tendency to behave authentically across contexts and levels of functioning (Kernis and Goldman 2006; Wood et al. 2008). Kernis and Goldman (2006) argue that authentic living is not confined to a person’s behavior or tendencies within relationships. Rather, authentic living also involves awareness and acceptance of one’s multifaceted self-tendencies, the willingness to process self-relevant information in an open, non-defensive way and without distorting it, and behavior in accordance with one’s needs. Therefore, dispositional authenticity includes general behavior and behaviors in relationships in addition to internal processes like unbiased processing of situations and relationships and awareness of one’s ‘true self.’

In U.S. and U.K. samples that are diverse in terms of age, ethnicity, and gender, both relational and dispositional authenticity have been linked with various indices of mental health and well-being, including higher self-esteem and life-satisfaction and lower negative affect and depressive symptoms (e.g., Goldman and Kernis 2002; Harter et al. 1996; Theran 2011; Wood et al. 2008). Evidence for a link between dispositional authenticity and mental health has been documented in samples of males and females, but gender differences have not been examined. Therefore, it is not clear whether there are gender differences in dispositional authenticity, its mental health correlates, or both. It is important to understand whether authentic behavior has stronger links to less depressive symptomatology and higher self-esteem for one gender as compared to the other. Although past research about gender differences in authenticity and related constructs is mixed, it is again possible that gender differences in authenticity may be more likely when trait-like rather than relationship-specific authenticity is under investigation. Therefore, given theoretical arguments about the particular importance of authenticity for females’ functioning, it was hypothesized that the association between authenticity and depression as well as self-esteem would be stronger for females than for males.

Potential Contributions to Authenticity

Because inauthenticity has been linked to lower self-esteem and higher depressive symptoms in samples that include participants from middle school to college-age and across ethnic backgrounds (e.g., Goldman and Kernis 2002; Kernis and Goldman 2006; Impett et al. 2008; Harter et al. 1996; Jack 1991; Theran 2011), research has begun to identify factors that may contribute to its development. Given that the way an individual feels about him or herself largely depends upon the context in which an individual lives and the relationships that an individual has (Jordan 2005), we focused on two aspects of important relationships with close others: perceived authenticity and gender ideology.

Considering that psychological development occurs in the context of relationships (e.g., Jordan 2005) and individuals often model the behavior of their close relationship partners (e.g., Bandura et al. 1961), it was hypothesized that individuals would be more likely to behave authentically across contexts when they perceived close others to be authentic. Although past research has not examined the authenticity of close others, it has provided evidence that relationships with close others are important to consider when examining the predictors of constructs related to authenticity. Middle and high school adolescents who perceive that their parents and peers provide more and higher quality support display lower levels of false self behavior, an effect mediated by hope to receive future support (Harter et al. 1996). Furthermore, in a study with an ethnically diverse sample of eighth grade girls, willingness to share one’s true opinions with authority figures was predicted by the security of the parent-adolescent attachment relationship (Theran 2009). The behavior of close others is important for adults as well: women and men who perceive their partners to be less validating report more inauthentic behavior when resolving conflicts within their relationship (Neff and Harter 2002), and greater dispositional authenticity is linked with positive relationship outcomes and individual well-being (Brunell et al. 2010).

In regards to gender ideology, preliminary research with females from early adolescence to college-age has linked more traditional beliefs about gender (Jasser 2008) as well as femininity ideology (Tolman and Porche 2000) with inauthentic behavior. No known studies have addressed the potential link between traditional gender ideology and authenticity in males. Given that males experience societal expectations and pressures (e.g., limiting emotion sharing, restricting emotions; O’Neil et al 1986), albeit different from the pressures that females are exposed to, it is reasonable to expect that internalized traditional views will encourage adherence to those expectations and in turn result in inauthenticity. Therefore, it was hypothesized that both males and females would be less likely to be authentic when they perceived close others as endorsing gender stereotypical beliefs. The current study focused on how perceptions of close others predict authenticity, specifically addressing important aspects of parents, friends, and important nonparental adults.

Parents

Beginning early in life, parents model behaviors that children can observe and imitate (Williams et al. 1985). Social learning theory suggests that children may employ certain behavioral strategies that they observe performed by adults (Bandura et al. 1961; Grych and Fincham 1990). Boys and girls may be most likely to engage in behavior that is similar to their same-gender parent (Snyder 1998). However, some research suggests that females may be more likely than males to model their same-gender parent (e.g., see Snyder 1998 for a review; also Underwood et al. 2008 with an ethnically diverse sample).

For example, Hartup (1962) presented children with a father and mother puppet who made different decisions. Children were then shown a child puppet (the same gender as the participant), and were asked what the child puppet would do in that scenario. Girls consistently chose the same decision as the mother puppet; this pattern was not observed in boys, who showed no preference for the mother or father puppet’s decision. In addition, Underwood et al. (2008) found, in an ethnically diverse sample of 9–10 year olds, that the marital conflict strategies that mothers used were associated with girls’ social and physical aggression with their peers. Namely, if mothers used more positive strategies with their partners, girls were more likely to employ positive strategies with their peers; however, if mothers used negative strategies, girls were more likely to engage in negative conflict resolution strategies with peers. Again, this pattern was not displayed by boys, whose behavior was not associated with maternal or paternal conflict strategies. Findings such as these provide reasons to expect that the predictors of authenticity may differ for males and females.

Consistent with this rationalization, undergraduate females who reported that their mothers hold gender-stereotyped opinions were more likely to endorse those opinions themselves; these gender-stereotyped views in turn predicted more relationally inauthentic behavior (Jasser 2008). A recent meta-analysis further supports that parental gender schemas are significantly related to offspring gender schemas (Tenenbaum and Leaper 2002). Nevertheless, previous research suggests that adolescents’ gender ideological beliefs may begin to diverge from their parents’, which are typically more traditional, after leaving for college and typically gaining increased exposure to egalitarian ideas (Myers and Booth 2002). This finding is especially true for females, as researchers found that female adults’ gender ideological beliefs were directly influenced by their experiences and only indirectly influenced by their parents’ beliefs. In contrast, males’ gender ideologies were predominately and directly influenced only by their parents’ beliefs (Myers and Booth 2002). Findings such as these, especially in regards to environmental influences, emphasize that the authenticity of male and female college students may be differentially related to the perceived gender beliefs of their parents. Therefore, the gender ideology of parents may indirectly influence authenticity through its influence on the gender ideology of offspring; however, it is reasonable to also expect that perceiving parents to have traditional gender beliefs may contribute to inauthenticity over and above the influence of one’s own beliefs, in part because individuals may feel pressured to act in accord with their parents’ beliefs even if those beliefs are no longer aligned with their own.

Given the studies reviewed above, both perceived authenticity and perceived gender ideology of parents may be important for the self-authenticity of college students; it was hypothesized that both male and female students would report more authenticity when their mothers and fathers were perceived to be authentic and egalitarian themselves. However, based on the research just reviewed, perceptions of mothers’ authenticity and gender ideology may be especially important for the development of authenticity for adolescent girls. Males, though theorized to act in the same ways as their fathers, may show this behavior to a lesser extent (Snyder 1998; Underwood et al. 2008). Therefore, it was hypothesized that perceptions of the same-gender parent may be more important than perceptions of the other gender parent in the development of authenticity. As supported by the majority of the previous research reviewed, this pattern may be especially true for females in comparison to males.

Friends

Although parents are crucial to psychosocial development in adolescence, there are many other important contributors to individual growth. Relationships with people other than parents become increasingly important as children transition into adolescence. Relational Cultural Theory (RCT) provides an additional theoretical explanation for the unique importance of relationships with friends. RCT emphasizes the importance of mutuality in relationships; in particular, this theory posits that psychological growth occurs when two people are mutually engaged in a relationship (Jordan 2005). Though healthy parent-child relationships are mutual, they are usually highly asymmetrical in regards to power. Individuals experience the greatest amount of mutuality in peer relationships. In addition, it is well-documented that individuals act in similar ways as their friend groups. For example, adolescents from the longitudinal and ethnically diverse National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (AddHealth) study with friends who smoked tobacco or drank alcohol were more likely to also engage in these behaviors (Ali and Dwyer 2009; Ali and Dwyer 2010), whereas, in a Canadian sample, adolescents with friends who engaged in prosocial behavior were more likely to display similar behaviors (Linden-Andersen et al. 2009). Furthermore, the gender ideology of adolescent peer groups are important predictors of adolescent behavior, such as sexual risk-taking (Laub et al. 1999), particularly because peers play an essential role in the cultural (re)production of gender roles and gendered behavior (e.g., Eder and Parker 1987). However, there is some evidence that males and females are differentially affected by exposure to peers; for instance, males are more affected by delinquent peers than are females (Mears, Ploeger, & Warr, 1998), which at least partially explains gender differences in delinquency. Therefore, the current study tested whether the authenticity of males and females is related in similar ways to the perceived beliefs and behaviors of their friends. It was hypothesized that college-aged males and females with friends who they perceive to hold egalitarian gender ideological beliefs and act authentically will think and behave similarly.

However, it is possible that there will be gender differences in the predictive utility of friend behavior in terms of participant authenticity. Relationships are clearly important for the psychological development of both males and females. Nevertheless, many have argued that males and females interact in peer relationships differently and consequently relationships may serve different functions for each gender (Maccoby 1990). For instance, studies rooted in the ‘gender differences (or cultures) hypothesis’ have provided theoretical and empirical evidence that girls engage in more collaboration, support, and cooperation in peer relationships than boys, who are more likely to engage in competitive or controlling behavior (e.g., Hibbard and Buhrmester 1998; Leaper 1994; Maltz and Borker 1982). Furthermore, adolescent males’ and females’ friendships (particularly those that are same-sex) are often argued to meet different kinds of needs. Male friendships may meet agentic needs mostly through actions, and female friendships may meet communal needs mostly via self-disclosure (Buhrmester 1990, 1996; Buhrmester and Furman 1987). Therefore, it was hypothesized that perceptions of friend behavior may be more strongly associated with the authenticity of females as compared to males.

Important Nonparental Adults

Past research has highlighted the influential role of “very important nonparental adults” or VIPs. These individuals were originally thought to uniquely benefit at-risk children; however, Beam, Chen, and Greenberger (2002) demonstrated that 82 % of a sample of ethnically diverse 11th grade students indicated that they had a close relationship with another adult besides their parents. Having positive relationships with VIPs—like mentors or teachers—is associated with lower incidences of behaviors like violence and suicide across high school (Resnick et al. 1993). Similar to friend relationships and in contrast to relationships with parents, relationships with nonparental adults are typically voluntary and more balanced in power. Evidence supporting this mutuality is provided by the finding that most VIPs indicate that they would be greatly upset if their relationship with the adolescent ended, demonstrating that adolescents seem to provide something important to the VIPs as well (Beam et al. 2002). Adolescents also indicate that they are very likely to turn to these adults in times of distress when they do not feel comfortable turning to their parents (Beam et al. 2002). In these moments, it may be critical that the nonparental adult is able to provide a safe environment for the adolescent to act and communicate authentically.

In addition to creating a safe environment for acting authentically, the intimate nature of relationships between nonparental adults and adolescents may contribute to similar modeling tendencies seen with parents and children. In support of this notion, research has demonstrated that adolescent perceptions of VIPs’ participation in illegal behavior uniquely predicts male adolescents’ own misconduct behavior; VIPs’ warmth and acceptance uniquely predict female depressive symptomatology (Greenberger et al. 1998 in an ethnically diverse sample). Some researchers have argued that close relationships with people other than parents and peers may be especially likely to encourage sharing of true thoughts and feelings because that sharing is less likely to threaten these relationships (e.g., Harter 1997). Because of the demonstrated association between nonparental adults’ conduct and adolescent conduct through modeling positive or negative behavior, it was hypothesized that individuals would be more likely to act authentically if they perceive their VIP(s) as behaving authentically and not holding strong gender-stereotyped views. However, as with the other potential environmental factors that may predict dispositional authenticity, the patterns of associations between self-authenticity and VIP gender ideology and authenticity may differ based on adolescent gender. There is some evidence that females bond more easily with adults than do boys (e.g., Darling et al. 1994), and that the mentoring relationships of girls may be more authentic, engaged, and empathetic than the mentoring relationships that boys experience (Liang et al. 2002). Therefore females may report perceptions of VIPs’ gender ideology and authenticity that are more similar to their own than males may report. Given the intimate nature of these relationships, compared to males, female adolescents may be more likely to either seek out VIPs that share views similar to their own or begin to adopt some of their VIPs beliefs and behaviors.

The Current Study

The goal of the current study was to expand our understanding of authenticity, particularly to fill gaps in the literature regarding potential gender differences in the mental health correlates of, as well as potential contributors to, dispositional authenticity. Past research has linked dispositional authenticity with mental health outcomes, but has not explored gender differences in these patterns. In addition, there is evidence that characteristics of close relationships are correlated with relational authenticity (e.g., Harter et al. 1998; Theran 2009). However, this was the first study to examine the role that the perceived gender ideology and authentic behavior of several types of close relationship partners play in predicting dispositional authenticity for both males and females. Understanding potential contributors to dispositional authenticity is crucial due to the association between this construct and self-esteem and depressive symptomatology (e.g., Goldman and Kernis 2002; Kernis and Goldman 2006; Wood et al. 2008).

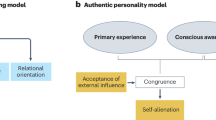

Based on the preceding review of the literature, we developed the conceptual model shown in Fig. 1. We hypothesized that males would report higher levels of authenticity than females (H1). In addition, we hypothesized that perceptions of close others (mothers, fathers, VIPs, and peers) as authentic (H2) and egalitarian (H3) would be associated with greater dispositional authenticity; we examined gender differences in the potential predictors of authenticity and predicted that perceptions of same-gender compared to other-gender parents would be more strongly linked with dispositional authenticity (H4). We also hypothesized that dispositional authenticity would be associated with lower depression (H5) and higher self-esteem (H6), and that authenticity would be more strongly associated with the depressive symptoms and self-esteem of females as compared to males (H7). Finally, we hypothesized that perceptions of close others as egalitarian would be associated with a more egalitarian gender ideology (H8) and that students with a more egalitarian gender ideology would also report more dispositional authenticity (H9).

Method

Participants

Participants were 470 individuals (68 % female) currently enrolled in colleges and universities across the country, ranging in age from 18 to 22 years old. Students were enrolled at Macalester College (41 %), a small liberal arts college in the Midwest, the University of California, Irvine (UCI), a large public university (31 %), or a variety of 54 U.S. colleges or universities that ranged in size (28 %, the full list of schools is available from the authors upon request). Macalester students were approximately evenly divided between males (56 %) and females (44 %); however, UCI (83 %) and other schools (64 %) were predominately female.

To determine if there were demographic differences based on school and gender (see Table 1), 2 X 3 ANOVAs were conducted in relation to age and year of school; multinomial logistic regression analyses were conducted to determine if gender and school were related to the categorical race/ethnicity variable (Caucasian, Asian American, and Other). On average, there were significant differences in age and year in school based on college, Fs(2, 458) > 16.55, ps < .001; Macalester students were significantly younger than both UCI students and students attending other colleges. UCI students were significantly older and farther along in school than students attending other colleges. There were no gender differences in age or year in school, Fs(1, 458) < 3.32, ps > .07. However, there were significant college by gender interactions in relation to both age and year in school, Fs(2, 458) > 3.04, ps < .049. Females were older and farther along in school at both Macalester and other colleges, however, males were older and farther along in school at UCI. There were no gender (ps > .59) or gender X college interactions (ps > .09) in relation to ethnicity; however, there were main effects of college. Compared to students at other colleges, significantly more UCI students were Asian American (b = -3.04, SE = .47, p < .001) and of other/mixed ethnicities (b = -2.19, SE = .41, p < .001) than students at other colleges. There were no differences in ethnicity between students at Macalester and students at other colleges, bs < .78, ps > .21.

Recruitment was completed using a snowball sampling method. The first author sent emails to class lists, lists for student groups (e.g., student athletes), and through social networking sites (primarily Facebook); in the email, people were given the option to participate and/or email the study link to anyone they knew in college. Participants were told the study was on college students’ thoughts and behaviors and how they perceived the thoughts of the people they are close with, like mothers, fathers, important nonparental adults and friends. There was no compensation for participation, except extra credit for those at the University of California, Irvine.

Procedures

All of the following questionnaires were administered online, via SurveyMonkey®. Participants were first given a brief description of the study and were allowed to participate after they had given consent. Participants were encouraged to answer all questions to the best of their ability; however, if they were completely unsure, they were given the option to skip the question. Before taking the questionnaires, participants were asked the last digit of their telephone number. This information determined the order in which the following questionnaires were given. Participants always completed the questionnaire containing “general information,” self-authenticity, and self gender ideology first and completed questions about their self-esteem and depressive symptoms last. The other questionnaires were answered in a random order based on the reported telephone digit.

Measures

General Information

Participants were asked to provide information about gender, race and ethnicity, age, and year in school. In addition, participants were asked questions similar to those asked by Beam et al. (2002) to identify important nonparental adults (VIPs). These questions asked participants to think of an adult who is important to them now and is not a parent or peer (probably older than 22). They were told to pick someone who has had a significant influence on them or whom they can count on in times of need. The same procedure was used to encourage participants to identify a specific friend. For both VIPs and friends, participants were asked to type the first name of the individual and to indicate “how important is this person in your life” given five options ranging from “not really all that important” to “truly key” (Beam et al. 2002). Participants were also asked to indicate how often they are in contact with the VIP and friend. Data suggested that participants were answering questions about close others who were in fact important and active in their lives: 84 % and 97 % of participants indicated that their VIP and friend, respectively, were “important” to “truly key.” Furthermore, 90 % of participants indicated that they were in contact with their VIP a minimum of every few months; 96 % of participants were in contact with their close friend with this frequency.

Authenticity of Self

Participants’ dispositional authenticity was assessed using a variation of the Authenticity Inventory 3 (AI-3; Kernis and Goldman 2006; see Appendix A). The original inventory includes 45 questions consisting of four subscales of authenticity; this version had acceptable internal consistency, retest reliability, and convergent validity. For the current study, a modified version was used that included 12 total items shown to be representative of the subscales in a pilot study. Items measured awareness of one’s feelings and motives (e.g., “For better or for worse I am aware of who I truly am”) and unbiased processing, which includes not denying or distorting knowledge or internal experiences (e.g., “I’d rather feel good about myself than objectively assess my personal limitations and shortcomings,” reverse scored), as well as the extent to which individuals act according to their own needs as opposed to acting to please others (e.g., “I try to act in a manner that is consistent with my personally held values, even if others criticize or reject me for doing so”) and the extent to which a person values openness and truthfulness in close relationships (e.g., “If asked, people I am close to can accurately describe what kind of person I am”). All questions were assessed on a 5-point scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). A mean of all of these items (with reverse scoring when appropriate) was calculated to represent dispositional authenticity; higher scores represent more authenticity (Cronbach’s alpha = .67, M = 3.49, SD = .43).

Perceived Authenticity of Others

Participants used a modified version of the abbreviated AI-3 (see Appendix A) that was used to assess self-authenticity (Kernis and Goldman 2006) to indicate their perception of their mothers’, fathers’, important nonparental adults’, and friends’ authenticity. A modified version of each of the 12 questions that was used when assessing self-authenticity was asked for each type of relationship, yielding 48 total questions about the perceived authenticity of close others. Examples of modified questions from the awareness subscale included: “For better or for worse my mother is aware of who she truly is,” and “My close nonparental adult tries to act in a manner that is consistent with his/her personally held values, even if others criticize or reject him/her for doing so.” Perceived authenticity measures were created by averaging the items of each scale for each close other (Mothers: Cronbach’s alpha = .81, M = 3.56, SD = .60; Fathers: Cronbach’s alpha = .80, M = 3.52, SD = .60; VIPs: Cronbach’s alpha = .78, M = 3.79, SD = .51; Friends: Cronbach’s alpha = .75, M = 3.59, SD = .53).

Gender Ideology

Participants completed a questionnaire to assess their opinions about appropriate roles for men and women (Lucas-Thompson and Goldberg 2012; see Appendix B). The scale included single items used in prior national survey studies including the National Longitudinal Study of Youth (NLSY), the National Survey of Families and Households, the International Social Survey Programme, and the General Social Surveys; also included were items from studies by Blankenhorn (1995), Ferree (1991), Glass et al. (1986), Moen et al. (1997), and Wilkie et al. (1998). These items were combined in order to have a multidimensional measure of gender ideology; an 11-item abbreviated version of the full form was utilized. Participants rated their agreement with a series of statements about roles of men and women on a 5-point scale from strongly agree to strongly disagree. Domains and sample items include: roles in the home (“women should take care of running their homes and leave running the country up to men”), employment (“a wife who carries out her full family responsibilities doesn’t have time for outside employment”), decision-making (“regardless of who earns more money, husbands and wives should make decisions about the family together”), political and religious involvement (“women should be allowed to be pastors, ministers, priests or rabbis”), division of labor (“whether or not she has a job, taking care of the housework should really be the wife’s responsibility”), and parenting (“parents should encourage just as much independence in their daughters as in their sons”). A mean of the items (with appropriate reverse scoring) was calculated to represent participant gender ideology; higher scores represent more traditional beliefs about gender roles (Cronbach’s alpha = .72, M = 1.50, SD = .45).

Perceived Gender Stereotyped Views of Others

Participants also answered the same questions from the Gender Ideology Scale in regards to how they perceive their mothers’, fathers’, important nonparental adults’, and friends’ gender ideological views (Mothers: Cronbach’s alpha = .81, M = 1.76, SD = .63; Fathers: Cronbach’s alpha = .86, M = 2.16, SD = .80; VIPs: Cronbach’s alpha = .85, M = 1.75, SD = .67; Friends: Cronbach’s alpha = .83, M = 1.73, SD = .65).

Depressive Symptomatology

Participants completed the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression (CES-D) Scale (Radloff 1977), a widely used, reliable, and valid measure of depressive symptoms. The scale consists of 20 questions that assess depressive symptoms from the last week. The scale is on a four-point scale, ranging from 0 (rarely or none of the time) to 3 (most or all of the time). A depression score was created by summing all 20 items (after appropriate reverse scoring); higher scores represent more depressive symptoms (Cronbach’s alpha = .90, M = 14.80, SD = 9.31). Scores of 16 or above are considered to be clinically significant depression. This criterion was met by 141 participants (30 %).

Self-Esteem

Participants completed the Rosenberg Self-Esteem (RSE) scale, which has 10 items (e.g., “At times I think I am not good at all”) and has a 4-point scale ranging from 1 “strongly disagree” to 4 “strongly agree” (Rosenberg 1979). The RSE scale is reliable and valid (e.g., Rosenberg 1979). A sum of the items was calculated to represent self-esteem (after appropriate reverse scoring), with higher scores representing higher self-esteem (Cronbach’s alpha = .82, M = 22.90, SD = 4.37).

Results

Before conducting the primary analyses of interest, the potential role of college and gender, as well as college by gender interactions, were examined (see Table 2). A MANOVA revealed significant college, F(24, 636) = 5.23, p < .001, gender, F(12, 317) = 4.30, p < .001, and college X gender, F(24, 636) = 1.56, p = .043 effects across all primary variables of interest.

In terms of college differences, there were significant univariate differences for self gender ideology and all perceptions of close others. Examination of post-hoc tests revealed that Macalester students were significantly less traditional than all other students; UCI students were significantly more traditional than students at other schools. In addition, students at Macalester and other schools perceived their close others to be significantly more authentic than did students at UCI; Macalester students perceived their close others to be significantly more egalitarian than all other students, and UCI students perceived their close others to be significantly more traditional than students at other schools.

In terms of gender differences, there were significant univariate differences for self gender ideology, as well as perceptions of the ideology of all close others’ except fathers. Males were significantly more traditional than females, and also perceived their close others to be significantly more traditional. Finally, the college X gender interaction was only significant at the univariate level for perceptions of maternal authenticity. Females attending UCI perceived their mothers to be more authentic than did males; at all other schools, males perceived their mothers to be more authentic than did females.

Hypothesis (H) 1: Males will report higher levels of authenticity than females.

The analyses reported above revealed that there were no significant differences in participant authenticity based on gender.

H2-H9: Testing the conceptual model in Figure 1.

Correlations were examined to test the bivariate relations represented in Fig. 1 (see Table 3). Then, to test the conceptual model in Fig. 1 and each of the corresponding hypotheses, path analysis with manifest variables was performed using SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina; PROC CALIS using the CARDS statement, using the maximum likelihood method of parameter estimation). Analyses were conducted separately for males and females. Path analysis is best conducted with samples of at least 200 participants; therefore, the sample of males was smaller than ideal to conduct path analysis. However, the size of the male sample exceeded the minimum number of participants necessary (based on the ratio of at least 5 participants for each parameter to be estimated, e.g., Hatcher 1994). School was included in the path model as a predictor of gender ideology and correlate of perceptions of close others because of its relation to several of the primary variables of interest.

The results of the path analyses are presented for females (Fig. 2) and males (Fig. 3); non-significant paths are presented because their exclusion/inclusion did not significantly affect the fit of the overall models. Overall, goodness of fit indices suggested that these models provided an adequate fit to the data (based on non-significant χ2 values, and normed fit index or NFI, non-normed fit index or NNFI, and comparative fit index or CFI, values of over .9; Bentler 1989; Bentler and Bonett 1980). Discussed in detail below are the results corresponding to the specific hypotheses tested in the conceptual model.

Path analysis for females. * p < .05 ** p < .01 *** p < .001 Note: Fit indices, χ2(23) = 33.09, p = .08; NNI: .97; NFI: .97; CFI: .99. Values represent standardized estimates. R2 values indicate the percentage of variance in the variable that is accounted for in the model. a 1 = Student attended a liberal arts school; 0 = Students did not attend a liberal arts school. Variable was allowed to covary in the model with each of the perceptions of others’ authenticity and gender ideology variables

Path analysis for males. + p < .10 * p < .05 ** p < .01 *** p < .001 Note: Fit indices, χ2(23) = 14.67, p = .91; NNI: 1.06; NFI: .97; CFI: 1.00. Values represent standardized estimates. R2 values indicate the percentage of variance in the variable that is accounted for in the model. a 1 = Student attended a liberal arts school; 0 = Students did not attend a liberal arts school. Variable was allowed to covary in the model with each of the perceptions of others’ authenticity and gender ideology variables

-

H2, H3, and H4. Perceptions of close others (mothers, fathers, friends, and VIPs) as authentic (H2) and egalitarian (H3) will be associated with greater dispositional authenticity. Perceptions of same-gender compared to other-gender parents will be more strongly linked with dispositional authenticity (H4).

At the bivariate level, for females, higher levels of authenticity were predicted by: higher perceived close others’ authenticity as well as more egalitarian self gender ideologies. For males, higher levels of authenticity were predicted by: higher perceived maternal and friend authenticity, as well reports of a more egalitarian self and perceptions of a more egalitarian mother and father gender ideology.

In the path model, female participants reported more authenticity when they perceived their mothers and VIPs to also be more authentic. However, there were no associations between perceptions of father or friend authenticity and self-authenticity. Furthermore, there were no associations between the perceived gender ideology of close others and dispositional authenticity. Male participants reported more authenticity when they perceived their mothers to be more authentic, but this path was only significant at trend levels. In addition, there was no significant association between authenticity and any other perceived authenticity or ideology characteristic of the close others.

-

H5, H6, and H7: Dispositional authenticity will be associated with lower depression (H5) and higher self-esteem (H6); these associations will be more strongly associated with the depressive symptoms and self-esteem of females as compared to males (H7).

At the bivariate level, authenticity was significantly correlated with depressive symptoms and self-esteem for both females and males, such that more authenticity was associated with fewer depressive symptoms and higher self-esteem. The same pattern was evident in the path model. For female college students, higher levels of authenticity were significantly associated with fewer depressive symptoms and greater self-esteem. Like with female students, male students reported fewer depressive symptoms and greater self-esteem with higher levels of authenticity. The size of the standardized estimates of the relation between authenticity and depressive symptoms as well as self-esteem were comparable in size, suggesting that authenticity was not associated more strongly with female than male mental health.

-

H8 and H9: Perceptions of close others as egalitarian will be associated with a more egalitarian gender ideology (H8) which, in turn, will be associated with higher levels of dispositional authenticity (H9).

For females, gender ideology was not significantly associated with authenticity or depressive symptoms, but females did report significantly higher levels of self-esteem when they also reported a more traditional gender ideology. In addition, as hypothesized, gender ideology was predicted in the model by the perceived gender ideology of mothers, friends, and VIPs. For males, gender ideology was not associated with authenticity or self-esteem; however, males who reported more traditional ideas about gender also reported more depressive symptoms (significant only at trend levels). As with females, gender ideology was predicted by the perceived gender ideology of friends; however, it was not related to the perceived gender ideology of mothers, fathers, or VIPs.

Discussion

The current study was the first to examine potential gender differences in dispositional authenticity and its mental health correlates, specifically depressive symptoms and self-esteem, as well as theoretically suggested but previously unexplored predictors of authenticity. These issues were examined in a U.S. sample of undergraduate students. Past research had linked dispositional authenticity with mental health outcomes in U.S. and U.K. samples (e.g., Goldman and Kernis 2002; Wood et al. 2008), but had not examined whether there are gender differences in these patterns, despite evidence from relational authenticity studies that gender is an important characteristic to consider when studying authenticity-related constructs (e.g., Gratch et al. 1995; Harper et al. 2006; Theran 2011). This study extends those findings to reveal no gender differences in dispositional authenticity or its mental health correlates; most males and females reported fewer symptoms of depression and better self-esteem when they also reported more dispositional authenticity. Furthermore, this study was the first to examine the role that the perceived authentic behavior and gender ideology of several types of close relationship partners play in predicting authenticity for both males and females. This study suggests that both males and females behave more authentically when they perceive their mothers to be more authentic, although this pathway was significant for males only at trend levels; the same pattern is seen for VIPs, or important nonparental adults, for females but not males.

Previous research has highlighted behaviors related to authenticity as primarily female schemas (e.g., Jack 1991; Jack and Dill 1992), with more important consequences for the well-being of females because of gender differences in socialization and the function of close relationships. Research has suggested that, compared to males, females are more likely to form intimate relationships (Maccoby 1990) and use social support as a coping mechanism (Rose and Rudolph 2006). However, in keeping with past research suggesting that both males and females display similar levels of self-silencing and relational authenticity (Gratch et al. 1995; Harper et al. 2006; Theran 2011), the current study suggests that males and females report similar levels of dispositional authenticity, and that both males and females who act authentically report higher levels of well-being. These findings extend past research by providing new information about the rates and consequences of dispositional authenticity for both males and females.

This study also supports previous findings that holding more traditional gender role beliefs is related to depressive symptoms in males (Good and Mintz 1990); males reported more depressive symptoms when they were inauthentic and endorsed traditional gender roles. These findings are consistent with past research that suggests that male inauthenticity may be driven by thinking and behaving in accord with more socially valued masculine behavior (Crawford 2006). However, this pattern of adhering to traditional masculine gender roles appears to be detrimental to the well-being of males. Interestingly, gender ideology was related to the self-esteem of females: those with a more traditional ideology reported higher self-esteem. This finding, however, is likely a product of females in this sample predominately ranging from strongly to moderately egalitarian in their gender ideological views, with few having highly traditional views. As Yakushko (2007) found, females with more feminist and moderate values had better subjective well-being than those with more traditional values. The relationship between more moderate egalitarian views and better self-esteem is likely complex, but may in part be due to the balance of having views that are more socially acceptable while maintaining the feelings of self-efficacy that accompany egalitarian views.

Past research has highlighted that relational authenticity is related to characteristics of parent and peer relationships (Harter et al. 1996; Jasser 2008; Theran 2009). However, this study was the first to examine contributors to dispositional authenticity and broaden the scope of important contributors to include qualities of relationships with mothers, fathers, friends, and VIPs. The results support the theoretical importance of close relationships for the development of behaviors like authenticity, particularly for females. Perceived increases in maternal authenticity were predictive of increased authenticity for both females and males (the latter at trend levels). Although past research has highlighted the potency of same-gender role models, this study suggests that perceptions of maternal authenticity are more strongly linked to the authentic traits of both females and males than are perceptions of paternal authenticity. Despite recent gains in equality between the genders in out-of-home employment (e.g., The U.S. Census Bureau 2011), mothers are still the more frequent primary caregiver (e.g., Work and Family Program 2004). It is possible that the perceived authenticity of the primary caregiver may be a more important contributor to self-authenticity than the perceived authenticity of the other parent. Whatever the reason, the results of this study suggest that the characteristics of close others’ are indirect predictors of mental health. These findings are in line with arguments that how individuals feel about themselves depends in large part upon the relationships that an individual has (e.g., Jordan 2005). Although effect sizes were small, the findings underscore the importance of perceptions of close relationship partners for psychosocial development and mental health.

Furthermore, females reported that they behaved more authentically when they also reported that a VIP behaved more authentically. This evidence corroborates the findings of Greenberger et al. (1998), who found that VIPs have an active and influential role in the positive development of adolescents, and that the value of these close relationships continues after adolescence. However, the current study suggests that perceptions of VIPs may be more important for the authentic behavior of females, even though both males and females rated their VIPs as an important and frequent contact. There are several potential explanations for this gender difference. Females may be more influenced by the authentic behavior of their VIP, perhaps because the females’ VIP relationships are more supportive or positive in a way that is more likely to encourage similar levels of authenticity. For instance, females report fewer problems measuring up to a mentor’s standards (Ensher and Murphy 2011 in a sample of predominately Caucasian adults) and report receiving more psychosocial support from their mentor (see O’Brien et al. 2010 for a meta-analysis). In addition, VIPs are likely to be of the same gender as their teens (Greenberger et al. 1998), and female mentors also report providing more psychosocial support than male mentors (O’Brien et al. 2010). Female undergraduates are also more comfortable than male undergraduates disclosing to intimate relationship partners (Stokes et al. 1980). Together, these factors may encourage sharing and similarity in female VIP relationships. Alternatively, females may be more likely to choose to develop close relationships with adults who display behaviors similar to their own, perhaps in part because of a greater importance of relationships to female well-being (e.g., Lazarus and Folkman 1984). Finally, it is also possible that the smaller samples of males utilized in the current study resulted in the lack of significant findings related to VIPs, particularly because our power to detect small effects was limited and the variance in authenticity explained by perceptions of close others was quite small. In addition, several potential predictors were correlated at the bivariate level with male and female authenticity but lost significance in the path models. It is crucial for future research to examine predictors of male authenticity in larger samples with better power to detect small effects.

Although the correlational, self-report nature of the current study’s design does not permit causal inferences, these findings suggest that authenticity may have developmental implications. In particular, finding that the perceived authenticity of mothers predicts self-authenticity raises the possibility that modeling authenticity for children will predict more dispositional authenticity as children age and, as a result, better mental health. In childhood, parents and other adults tend to emphasize characteristics like honesty and respect in relation to how children should treat other people and objects. However, adults do not always stress the importance of communicating how one truly feels within relationships (Bronson and Merryman 2009). In fact, parents are frequently proud of their children for telling “white lies,” like saying they like a gift when they truly do not; this behavior is seen as being polite, not as lying (Bronson and Merryman 2009). In childhood, these requests may be benign in nature; however, as children move into adolescence these encouragements to appease others may conflict with their developing identity. Our findings suggest that it may be important for adults to communicate and demonstrate the importance of conveying one’s true self and acting in accord with one’s values. Future research should attempt to replicate these findings using longitudinal designs with multiple reporters to better understand the potential implications of being encouraged to and observing others be authentic.

Limitations and Future Directions

This study had several limitations. First, the sample size for males was small and did not result in ideal power to detect small effects. This lack of power resulted in difficulty interpreting whether unique predictors for females were due to reduced power for analyses with males. Thus, future studies should focus on increasing power to better understand the contributors of authenticity in males. In addition, although the sample was relatively diverse in terms of ethnicity, participants were all attending college in the U.S., with the majority attending two different colleges or universities. Thus, these findings may not be representative of all college students or all young adults. For instance, the finding that perceived VIP authenticity predicts female authenticity may be a product of participants attending college and living further away from their parents. Therefore, future studies should address whether these results are found with a more representative population of young adults, including those not attending college.

Furthermore, in this study we were limited to examining college students’ reports of their perceptions of close others. Remaining to be seen is how accurate these perceptions are, especially because participants reported their perceptions of internal processes like unbiased processing, or if ‘actual’ authenticity and/or gender ideology of parents, friends, and VIPs is also related to emerging adult authenticity. Future work should examine correspondence between these perceptions and personal reports of authenticity and gender ideology in family and friends, as well as examine which are better predictors of youth authenticity and mental health. Attempts to do so could include use of other measures of dispositional authenticity (e.g., Wood et al. 2008) that might result in more desirable psychometric properties than those utilized in this study. Finally, this study established a correlational link between authenticity and depression in males and females. To better understand causation, and rule out potential directionality or third variables problems, future studies may want to utilize longitudinal examinations of the predictors and consequences of authenticity, as well as potential experimental manipulations, such as attempts to increase authenticity in individuals with clinical depression to assess the potential mental health benefits. If counseling aimed at increasing authenticity results in a relief of depressive symptoms it would establish a causal link between authenticity and depression. There is evidence from work with predominately Caucasian middle school students that interventions can effectively improve relational qualities including authenticity, particularly for males (e.g., Liang et al. 2008); future research should explore whether interventions such as these are also effective at improving mental health.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the current study demonstrates that higher levels of dispositional authenticity are related to more self-esteem and fewer depressive symptoms in females and males. Furthermore, the perceived authenticity of close others, particularly mothers (females and males) and important nonparental adults (VIPs; females only), appears to predict the authenticity of college-aged students. Findings highlight the importance of perceptions of close relationship partners for the dispositional authenticity of emerging adults, and suggest that adults should display and encourage authentic behavior in youth as authentic awareness, behavior, assessment of oneself, and communication are associated with better mental health.

References

Ali, M. M., & Dwyer, D. S. (2009). Estimating peer effects in adolescent smoking behavior: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Adolescent Health, 45, 402–408. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.02.004.

Ali, M. M., & Dwyer, D. S. (2010). Social network effects in alcohol consumption among adolescents. Addictive Behaviors, 35, 337–342. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.12.002.

Altman, J. H., & Wittenborn, J. R. (1980). Depression-prone personality in women. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 89, 303–308. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.89.3.303.

Bandura, A., Ross, D., & Ross, S. A. (1961). Transmission of aggression through imitation of aggressive models. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 63, 575–82. doi:10.1037/h0045925.

Beam, M. R., Chen, C., & Greenberger, E. (2002). The nature of adolescents’ relationships with their “very important” nonparental adults. American Journal of Community Psychology, 30, 305–325. doi:10.1023/A:1014641213440.

Bentler, P. M. (1989). EQS structural equations program manual. Los Angeles: BMDP Statistical Software.

Bentler, P. M., & Bonett, D. G. (1980). Significance tests and goodness-of-fit in the analysis of covariance structures. Psychological Bulletin, 88, 588–606. doi:10.1037//0033-2909.88.3.588.

Blankenhorn, D. (1995). Fatherless America: Confronting our most urgent social problem. New York: Basic Books.

Block, J. H. (1973). Conceptions of sex role: Some cross-cultural and longitudinal perspectives. American Psychology, 28, 512–526. doi:10.1037/h0035094.

Bronson, P. O., & Merryman, A. (2009). Nurture shock: New thinking about children. New York: Grand Central Publishing.

Brown, L. S. (1994). Subversive dialogues: Theory in feminist therapy. New York: Basic Books.

Brunell, A. B., Kernis, M. H., Goldman, B. M., Heppner, W., Davis, P., Cascio, E. V., & Webster, G. D. (2010). Dispositional authenticity and romantic relationship functioning. Personality and Individual Differences, 48, 900–905. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2010.02.018.

Buhrmester, D. (1990). Intimacy of friendship, interpersonal competence, and adjustment during preadolescence and adolescence. Child Development, 61, 1101–1111. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02844.

Buhrmester, D. (1996). Need fulfillment, interpersonal competence, and the developmental contexts of early adolescent friendship. In W. Bukowski, A. Newcomb, & W. Hartup (Eds.), The company they keep: Friendship in childhood and adolescence (pp. 158–185). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Buhrmester, D., & Furman, W. (1987). The development of companionship and intimacy. Child Development, 58, 1101–1113. doi:10.2307/1130550.

Chubb, N. H., Fertman, C. I., & Ross, J. L. (1997). Adolescent self-esteem and locus of control: A longitudinal study of gender and age differences. Adolescence, 32, 113–129.

Cramer, K. M., & Thoms, N. (2003). Factor structure of the Silencing the Self Scale in women and men. Personality and Individual Differences, 35, 525–535. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(02)00216-7.

Crawford, M. (2006). Transformations: Women, gender & psychology. Boston: McGraw Hill.

Darling, N., Hamilton, S. F., & Niego, S. (1994). Adolescents’ relations with adults outside the family. In P. Montemayor, G. Adams, & T. Gullotta (Eds.), Personal relationships during adolescence. Advances in adolescent development: An annual book series (pp. 216–235). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Denner, J., & Dunbar, N. (2004). Negotiating femininity: Power and strategies of Mexican American girls. Sex Roles, 50, 301–314. doi:10.1023/B:SERS.0000018887.04206.d0.

Eder, D., & Parker, S. (1987). The cultural production and reproduction of gender: The effect of extracurricular activities on peer-group culture. Sociology of Education, 60, 200–213. doi:10.2307/2112276.

Ensher, E. A., & Murphy, S. E. (2011). The Mentoring Relationship Challenges scale: The impact of mentoring stage, type, and gender. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 79, 253–266. doi:10.1016/j.jvb.2010.11.008.

Ferree, M. (1991). The gender division of labor in two-earner marriages. Journal of Family Issues, 12, 158–180. doi:10.1177/01925139101200200212,156.

Glass, J., Bengtson, V. L., & Dunham, C. C. (1986). Attitude similarity in three-generation families: Socialization, status inheritance, or reciprocal influence? American Sociological Review, 51, 685–98. doi:10.2307/2095493.

Gilligan, C. (1982). In a different voice. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Goldman, B. M., & Kernis, M. H. (2002). The role of authenticity in healthy psychological functioning and subjective well-being. Annals of the American Psychotherapy Association, 5, 18–20.

Good, G. E., & Mintz, L. B. (1990). Gender role conflict and depression in college men: Evidence for compounded risk. Journal of Counseling and Development, 69, 17–21. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6676.1990.tb01447.x.

Gratch, L. V., Bassett, M. E., & Attra, S. L. (1995). The relationship of gender and ethnicity to self-silencing and depression among college students. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 19, 509–515. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.1995.tb00089.x.

Greenberger, E., Chen, C., & Beam, M. R. (1998). The role of “very important” nonparental adults in adolescent development. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 27, 321–343. doi:10.1023/A:1022803120166.

Grych, J. H., & Fincham, F. D. (1990). Marital conflict and children’s adjustment: A cognitive-contextual framework. Psychological Bulletin, 108, 267–290. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.108.2.267.

Hankin, B. L., Abramson, L. Y., Moffitt, T. E., Silva, P. A., McGee, R., & Angell, K. E. (1998). Development of depression from preadolescence to young adulthood: Emerging gender differences in a 10-year longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 107, 128–140. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.107.1.128.

Harper, M. S., Dickson, J. W., & Welsh, D. P. (2006). Self-silencing and rejection sensitivity in adolescent romantic relationships. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 35, 459–467. doi:10.1007/s10964-006-9048-3.

Hart, B. I., & Thompson, J. M. (1996). Gender role characteristics and depressive symptomatology among adolescents. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 16, 407–426. doi:10.1177/0272431696016004003.

Harter, S. (1997). The personal self in social context: Barriers to authenticity. In R. D. Ashmore & L. J. Jussim (Eds.), Self and identity: Fundamental issues (pp. 81–105). New York: Oxford University Press.

Harter, S., Marold, D. B., Whitesell, N. R., & Cobbs, G. (1996). A model of the effects of perceived parent and peer support on adolescent false self behavior. Child Development, 67, 360–374. doi:10.2307/1131819.

Harter, S., Waters, P. L., Whitesell, N. R., & Kastelic, D. (1998). Level of voice among female and male high school students: Relational context, support, and gender orientation. Developmental Psychology, 34, 892–901. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.34.5.892.

Hartup, W. W. (1962). Some correlates of parental imitation in young children. Child Development, 33, 85–96.

Hatcher, L. (1994). A step-by-step approach to using SAS® for factor analysis and structural equation modeling. Cary: SAS Institute Inc.

Hibbard, D. R., & Buhrmester, D. (1998). The role of peers in the socialization of gender-related social interaction styles. Sex Roles, 39, 185–202. doi:10.1023/A:1018846303929.

Hinshaw, S. P., & Kranz, R. (2009). The triple bind: Saving our teenage girls from today’s pressures. New York: Ballantine.

Impett, E. A., Sorsoli, L., Schooler, D., Henson, J. M., & Tolman, D. L. (2008). Girls’ relationship authenticity and self-esteem across adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 44, 722–733. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.44.3.722.

Jack, D. C. (1991). Silencing the self: Women and depression. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Jack, D., & Dill, D. (1992). The Silencing the Self Scale: Schemas of intimacy associated with depression in women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 16, 97–106. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.1992.tb00242.x.

Jasser, J. L. (2008). Inauthentic self in relationship: The role of attitudes toward women and mother's nurturance (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Gainesville, Florida: University of Florida.

Jordan, J. V. (2005). Relational resilience in girls. In S. Goldstein & R. B. Brooks (Eds.), Handbook of resilience in children (pp. 79–90). New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers.

Kernis, M. H., & Goldman, B. M. (2006). A multicomponent conceptualization of authenticity: Theory and research. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 38, 283–357. doi:10.1016/S0065-2601(06)3800-9.

Laub, C., Somera, D. M., Gowen, L. K., & Díaz, R. M. (1999). Intervention for youth targeting “risky” gender ideologies: Constructing a community-driven, theory-based HIV prevention. Health Education & Behavior, 26, 185–199. doi:10.1177/109019819902600203.

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Spring Publishing Company.

Leaper, C. (1994). Exploring the consequences of gender segregation on social relationships. In C. Leaper (Ed.), Childhood gender segregation: Causes and consequences (pp. 67–86). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Liang, B., Tracy, A., Kenny, M., & Brogan, D. (2008). Gender differences in the relational health of youth participating in a social competency program. Journal of Community Psychology, 36, 499–514. doi:10.1002/jcop.20246.

Liang, B., Tracy, A. J., Taylor, C. A., & Williams, L. M. (2002). Mentoring college-age women: A relational approach. American Journal of Community Psychology, 30, 271–288. doi:10.1023/A:1014637112531.

Linden-Andersen, S., Markiewicz, D., & Doyle, A. (2009). Perceived similarity among adolescent friends. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 29, 617–637. doi:10.1177/0272431608324372.

Lucas-Thompson, R. G., & Goldberg, W. A. (2012). The importance of gender ideology for college students’ current gendered behavior and expected work-family roles. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Maccoby, E. E. (1990). Gender and relationships: A developmental account. American Psychologist, 45, 513–520. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.45.4.513.

Maltz, D. N., & Borker, R. A. (1982). A cultural approach to male-female miscommunication. In J. Gumperz (Ed.), Language and Social Identity (pp. 195–216). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Mears, D. P., Ploeger, M., & Warr, M. (1998). Explaining the gender gap in delinquency: Peer influence and moral evaluations of behavior. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 35, 251–266.

Miller, J. B. (1986). Toward a new psychology of women. Boston: Beacon Press.

Moen, P., Erickson, M. A., & Dempster-McClain, D. (1997). Their mother’s daughters? The intergenerational transmission of gender attitudes in a world of changing roles. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 59, 281–293. doi:10.2307/353470.

Myers, S. M., & Booth, A. B. (2002). Forerunners of change in nontraditional gender ideology. Social Psychology Quarterly, 65, 18–37. doi:10.2307/3090166.

Neff, K. D., & Harter, S. (2002). The authenticity of conflict resolutions among adult couples: Does women’s other-oriented behavior reflect their true selves? Sex Roles, 47, 403–417. doi:10.1023/A:1021692109040.

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (1987). Sex differences in unipolar depression: Evidence and theory. Psychological Bulletin, 101, 259–82. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.101.2.259.

O’Brien, K. E., Biga, A., Kessler, S. R., & Allen, T. D. (2010). A meta-analytic investigation of gender differences in mentoring. Journal of Management, 36, 537–554. doi:10.1177/0149206308318619.

O’Neil, J. M., Helms, B. J., Gable, R. K., Davis, L., & Wrightsman, L. (1986). Gender Role Conflict Scale: College men’s fear of femininity. Sex Roles, 14, 335–350. doi:10.1007/BF00287583.

Pipher, M. (1994). Reviving Ophelia: Saving the lives of adolescent girls. New York: Ballantine Books.

Pleck, J. H. (1995). The gender role strain paradigm: An update. In R. F. Levant & W. S. Pollack (Eds.), A new psychology of men (pp. 11–32). New York: Basic Books.

Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385–401. doi:10.1177/014662167700100306.

Resnick, M. D., Harris, L. J., & Blum, R. W. (1993). The impact of caring and connectedness on adolescent health and well being. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 29, S3–S9. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1754.1993.tb02257.x.

Rose, A. J., & Rudolph, K. D. (2006). A review of sex differences in peer relationship processes: Potential trade-offs for the emotional and behavioral development of girls and boys. Psychological Bulletin, 132, 98–131. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.98.

Rosenberg, M. (1979). Conceiving the self. New York: Basic Books.

Shrier, L. A., Harris, S. K., Sternberg, M., & Beardslee, W. R. (2001). Associations of depression, self-esteem, and substance use with sexual risk among adolescents. Preventative Medicine, 33, 179–189. doi:10.1006/pmed.2001.0869.

Smolak, L., & Munstertieger, B. F. (2002). The relationship of gender and voice to depression and eating disorders. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 26, 234–241. doi:10.1111/1471-6402.t01-1-00006.

Snyder, J. R. (1998). Marital conflict and child adjustment: What about gender? Developmental Review, 18, 390–420. doi:10.1006/drev.1998.0469.

Stokes, J., Fuehrer, A., & Childs, L. (1980). Gender differences in self-disclosure to various target persons. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 27, 192–198. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.27.2.192.

Tashakkori, A., & Thompson, V. D. (1989). Gender, self-perception, and self-devaluation in depression: A factor analytic study among Iranian college students. Personality and Individual Difference, 10, 341–354. doi:10.1016/0191-8869(89)90108-6.

Tenenbaum, H. R., & Leaper, C. (2002). Are parents’ gender schemas related to their children’s gender-related cognitions? A meta-analysis. Developmental Psychology, 38, 615–630. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.38.4.615.

Theran, S. A. (2009). Predictors of level of voice in adolescent girls: Ethnicity, attachment, and gender role socialization. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38, 1027–1037. doi:10.1007/s10964-008-9340-5.

Theran, S. A. (2010). Authenticity with authority figures and peers: Girls’ friendships, self-esteem, and depressive symptomatology. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 519–534. doi:10.1177/0265407510363429.