Abstract

The present study explored the gender characteristics of narcissism as well as its relationship with friendship quality dimensions (i.e., trust & support, validation, and disclosure & communication) among 485 (197 boys and 288 girls) junior high and high school adolescents in a Southwest province in China. Significant gender differences were found, such that boys were more narcissistic than girls,while girls reported higher levels of friendship qualities, including validation and disclosure & communication. To examine gender moderations in the relationships between narcissism and friendship quality dimensions, multiple-group (by boys and girls) structural equation modeling were conducted. The results revealed the significant gender moderations in the associations between narcissism and friendship quality dimensions, while controlling for adolescent grade level. Specifically, narcissism significantly and positively related to the three aspects of friendship qualities (i.e., trust & support, validation, and disclosure & communication) among boys, but was not related to friendship quality among girls. Discussions are provided for an understanding of the current findings in the Chinese cultural context.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Narcissism as a normal personality trait has received much attention in recent decades. Distinctive features of narcissism include grandiose self concept, a sense of superiority and entitlement, and interpersonal exploitativeness (Morf and Rhodewalt 2001). There is extensive literature on the relationship between narcissism and psychological well-being (Sedikides et al. 2004) and aggression (Bushman et al. 2009) that have been established among U.S. adults. The complex nature of narcissism makes it especially interesting to investigate the interpersonal relationships of narcissistic individuals. It has been suggested that U.S. college students with high scores on trait narcissism are charming (Back et al. 2010), but not good at long term relationships (Paulhus 1998). Previous studies examining narcissism and social relationships were mostly conducted in the realm of general relationships and romantic relationships among the U.S. population (Paulhus 1998; Campbell et al. 2002). Moreover, although we have gained increasing knowledge about narcissism among college students and older adults in Western countries, little is known about younger narcissistic individuals’ social relationships, especially in a collectivistic culture. As a type of social relationship prominent during adolescence, friendship is highly related to adolescents’ adjustment (Hartup 1996). Therefore, investigating the relationship between narcissism and aspects of friendship quality (e.g., companionship, trust & support, disclosure & communication and validation) may have developmental significance for adolescents and enrich our knowledge about the function of narcissism in adolescents’ interpersonal relationships.

The present study aims to explore the relationship between narcissism and different aspects of friendship quality during adolescence as well as compare these relationships between Chinese adolescent boys and girls. Since friendship quality consists of different dimensions, the present study would examine companionship (e.g., playing together), trust & support (e.g., caring about feelings, giving advice), disclosure & communication (e.g., telling secrets to each other), validation (e.g., thinking each other important and special), and conflict and betrayal (e.g., quarreling). Furthermore, although many studies have revealed gender differences in narcissism with participants from different countries (e.g. Foster et al. 2003; Ryan et al. 2008), few have addressed the important question that whether narcissistic individuals’ interpersonal relationships are different across gender. Aiming to shed light on this question, our research explores gender moderation in the associations between narcissism and friendship qualities among Chinese adolescents.

Narcissism in Childhood and Adolescence

A few studies have investigated gender and age differences on narcissism during childhood and adolescence, as well as psychological adjustment of narcissistic adolescents. These studies indicate that males are more narcissistic than females among adults (Foster et al. 2003; Morf and Rhodewalt 2001) and among U.S. primary school children (Thomaes et al. 2008). Furthermore, gender is an important factor in the expression of narcissism. For instance, gender was found to moderate the relationship between narcissism and problem behaviors such that it was significantly linked to relational aggression among U.S. adolescent (Grade 5 to Grade 9) girls, but not boys (Marsee et al. 2005). These gender differences may suggest that girls’ adjustment is more negatively impacted by narcissism, which is partly due to the gender norm regarding narcissistic behaviors. Narcissistic behaviors may be more socially acceptable and adaptive for males than for females. However, it is yet to be determined whether the same gender differences in the functioning of narcissism can be extended to the interpersonal relationships among adolescents.

In addition to gender differences in narcissism, a few studies have also investigated the age-related changes in narcissism and the findings are often inconsistent depending on the age range of the samples. For instance, Forster and his colleagues (2003) found that narcissism declined in older age among a sample with ages ranging from 8 to 83. A recent longitudinal study with U.S. participants, on the other hand, showed that narcissism increases from age 14 to 18 (Carlson and Gjerde 2009). Also, some studies have found no age-related changes in narcissism among 16 to 18 year old U.S. adolescents (e.g., Barry et al. 2007). Given this findings, this study will further examine the age differences in narcissism as well as have a control for age in the examination of the associations between narcissism and friendship quality dimensions.

When investigating the relationship between narcissism and adjustment, recent research has found associations between narcissism and problem behaviors in childhood and adolescence. In comparison to those who are low on narcissism, U.S. children and adolescents with high narcissism tend to be more aggressive (Thomaes et al. 2008; Fossati et al. 2010) and have more conduct problems (Barry et al. 2009; Bukowski et al. 2009). On the other hand, studies have also found positive associations between narcissism and adjustment in late adolescence as those found in adulthood (Sedikides et al. 2004). For instance, Lapsley and Aalsma (2006) found that narcissism was positively related to Canadian adolescents’ self-worth, mastery coping, and superior adjustment, but negatively associated with depression and suicidal ideation, which suggest some adaptive significance of narcissism during adolescence.

Narcissism and Interpersonal Relationships

Research on narcissism and interpersonal relationships reveals interesting but inconsistent findings. Numerous studies have indicated that narcissistic individuals have difficulties with interpersonal relationships. Narcissism is inversely related to self-reported empathy (Bushman et al. 2003) and forgiveness (Eaton et al. 2006) as revealed in U.S. populations. Additionally, narcissistic U.S. individuals are aggressive (Bushman et al. 2009) and are likely to be disliked by others in the long run (Paulhus 1998). Even in close relationships (e.g., romantic relationship), narcissism is related to certain deficiencies (Campbell et al. 2002). On the other hand, positive functions of narcissism in social relationships have also been found. For example, narcissistic U.S. college students are attractive to observers at first sight because of characteristics such as fancier clothing, more charming facial expressions, more self-assured body movements, and more verbal humor (Back et al. 2010).

Theories have been proposed to reconcile the paradox of narcissistic individuals’ social relationships. According to the dynamic self-regulatory processing model (Morf and Rhodewalt 2001), narcissistic individuals try to regulate their behavior and operate on their social environments to create and maintain their positive self-view. On one hand, they might regulate their behavior attractively to obtain positive feedback from others that enhances their self-worth. On the other hand, since these individuals’ primary goal is to maintain self-worth and not to obtain to closeness to others, their selfishness and devaluing of others might bring difficulties to their social relationships.

Although many studies have been conducted to investigate the association of narcissism and interpersonal relationship, not many studies have explored narcissistic the close interpersonal relationships, such as friendship, among adolescents. Only one study found that narcissistic U.S. college students prefer social goals promoting positive outcomes in friendship (e.g., having fun; Foster et al. 2009). Given the importance of friendship in adolescents’ development (Hartup 1996), exploring the associations between narcissism and adolescents’ friendship quality can help us understand how narcissism functions to influence interpersonal relationship development. Such examinations also allow us to examine how previous theoretic models may be applied to a different type of social relationship at a younger age.

Narcissism in the Chinese Culture

In the present literature, our knowledge about narcissism and its relation to social relationships primarily comes from studies conducted in Western cultures. Some research suggests that people in individualistic cultures are more narcissistic than those in collectivistic cultures (Foster et al. 2003). Although within cultural variations exist, China is a typical collectivistic country (Oyserman et al. 2002). The traditional cultural values suggest that Chinese are modest and downplay the significance of the self. However, inconsistent findings also exist in the literature suggesting that Chinese are more narcissistic than Americans (Fukunishi et al. 1996; Kwan et al. 2009). Song and Li (2010) found that Chinese narcissists are usually described as having a high sense of superiority, self-love and authority. These views about narcissism are similar to those found in Western cultures. In addition, studies have revealed that narcissism is positively related to self-esteem and aggression, and negatively correlated with anxiety among Chinese college students (Zhou et al. 2009; Li and Gao 2011). These results are consistent with findings in Western samples (Sedikides et al. 2004; Bushman et al. 2009).

Limited research has investigated whether findings about narcissism in interpersonal relationships found in Western countries can be extended to narcissistic individuals in collectivistic countries. However, many previous studies have suggested that positive self-view is associated with positive peer relationships among both Western (Parker et al. 2005) and Chinese (Lai et al. 2006) adolescents. In addition, some empirical evidence has revealed that narcissists in collectivistic cultures show similar interpersonal relationships with those in Western countries (Tanchotsrinon et al. 2007). With a sample from Thailand, Tanchotsrinon et al. (2007) found similar results to those reported in Western countries: Narcissism still predicted attraction to targets who offered the potential for self-enhancement. However, both narcissists and non-narcissists in their study showed a higher overall attraction to caring targets, which was inconsistent with the results found in Western cultures. This finding may suggest that, although findings from Western countries may be extended to narcissistic individuals in collectivistic countries, cultural context might influence the functioning of narcissism in interpersonal relationships. According to the dynamic self-regulatory processing model of narcissism (Morf and Rhodewalt 2001), the self-concept of narcissistic individuals is grandiose but vulnerable. Narcissists often use special self-regulatory strategies to maintain their grandiose views of themselves. In individualistic cultures, people value agent traits, which may be an important source for Western self-view. Thus, narcissistic individuals in Western cultures may perceive themselves as attractive, intelligent, extroverted, and successful in order to maintain positive self concepts. However, in China, the quality of one’s social relationships is a strong determinant of one’s self-worth and well-being (Bond and Wang 1983). It is possible that narcissistic individuals in Eastern culture might value harmonious relationships with others in order to improve their self-view. Therefore, in collectivistic countries, such as China, narcissism might be associated with quality interpersonal relationships, such as friendship.

Friendship Quality in Adolescence

A critical interpersonal relationship in adolescents’ lives is friendship, which is closely related to their social and emotional development. Friendship includes many aspects such as having friends, the identity of one’s friends, and the quality of the friendships (Hartup 1996). Among these aspects, friendship quality is particularly important (Berndt 2002). Most theorists perceive friendship quality as multidimensional, addressing both positive (e.g., companionship, trust & support, disclosure & communication and validation) and negative (e.g., conflict and betrayal) aspects of the relationship (Parker and Asher 1993). Among different aspects of friendship quality, only the positive aspects can predict adjustment of U.S. adolescents (Demir and Urberg 2004). High-quality friendships may enhance adolescents’ self-esteem and psychological health (Berndt and Keefe 1995). Moreover, as shown by research among U.S. populations, friendship quality can buffer against adjustment problems when a child is not well accepted or has fewer friends (Waldrip et al. 2008), and moderates the effect of parenting on children’s internalizing symptoms (Gaertner et al. 2010).

Several research studies have revealed age-related changes and gender differences in adolescents’ friendship qualities. From middle to late adolescence, friendship qualities improve among U.S. adolescents (Way and Greene 2006). Cross-cultural similarities have been found on gender differences in friendship. When interacting with a friend, girls’ interactions are more positive than boys among Western (Youngblade and Belsky 1992) and Chinese (Zou et al. 1998) adolescents. Furthermore, researchers have also found gender differences in the relations between friendship quality and behaviors among U.S. adolescents (e.g. Fanti et al. 2009). Research among Chinese primary school students also shows that relational regression was positively related to girls’ friendship qualities, while negatively related to boys’ friendship qualities (Wei et al. 2011). These findings suggest that behaviors in keeping with children’s gender role may be associated with positive friendship quality.

In addition to the gender and age related findings, previous research has examined the contributing factors for friendship quality, such as attachment styles, aggressive and prosocial behaviors (e.g., Youngblade and Belsky 1992; Cillessen et al. 2005; Lansford et al. 2006). Despite advances in research, little is known about how personality traits, such as narcissism, may relate to adolescents’ friendship quality.

Present Study

This study aims to address how narcissism and friendship qualities are related during adolescence as well as how these associations vary by adolescents’ gender using a sample of Chinese adolescents. We aim to explore the relationships between narcissism and different aspects of friendship quality, because narcissism may differently relate to various aspects of friendship quality. Previous studies involving U.S. adults have found that narcissists are motivated to get positive outcomes from friendship (Foster et al. 2009). These findings suggest that narcissism may be associated with positive friendship quality. Drawing on the dynamic self-regulatory processing model of narcissism (Morf and Rhodewalt 2001), narcissistic individuals’ primary motivation is to create or maintain a grandiose self-concept or a positive self-view. Having quality friendship may help adolescents achieve this goal by validating their self-worth. Because validation from friends is a way to enhance one’s self-worth, we expect narcissism to positively relate to the validation aspect of friendship quality. Additionally, because having harmonious and close social relationships is important to the self-concepts of Chinese (Bond and Wang 1983), satisfactory friendship qualities such as those reflected by the trust & support, disclosure & communication, and companion & entertainment dimensions, may especially improve the self-view of Chinese adolescents who endorse narcissism. Therefore, it is predicted that narcissism will be positively linked to these aspects of friendship qualities among Chinese adolescents. On the other hand, the negative dimension of friendship quality, conflict and betrayal, would be likely to negatively relate to narcissism.

Furthermore, the relationships between narcissism and friendship qualities may vary as a function of adolescents’ gender. Illuminated by previous research (Foster et al. 2003; Thomaes et al. 2008), we first expect that narcissism is more normative in Chinese adolescent boys such that they will report higher narcissism than girls. Furthermore, research on gender socialization suggests that social behaviors in accordance with gender role are associated with positive psychological adjustment (Grotpeter and Crick 1996). Cross-cultural similarities in this view have also been observed among Chinese children (Wei et al. 2011). Since some components of narcissism (e.g., uniqueness and authority) are also considered as masculine (Bem 1975; Zhang et al. 2001), narcissistic behaviors may be more socially acceptable and adaptive for males than for females. Given these theoretical and empirical considerations, we expect that the association between narcissism and positive friendship qualities will be stronger for boys than for girls in the current sample of Chinese adolescents. Furthermore, given that age may be related to narcissism (Carlson and Gjerde 2009; Foster et al. 2003), it is necessary to control for age in the association analysis to obtain a clear delineation of relationships between narcissism and friendship quality dimensions for Chinese adolescent boys and girls.

Method

Participants

Participants were 485 (197 boys and 288 girls) students from a Southwest province in China. Specifically, there were 228 students from Grade 1 to Grade 3 in junior high school, aged from 12 to 16 years and 257 students from Grade 1 to Grade 3 in high school, aged from 16 to 19 years old. The mean age of these students was 15.91 (SD = 1.92). All the participants were recruited from one secondary school. After obtaining permission from the school and parents, research assistants surveyed the participating students in one class session in the students’ classrooms. Most of these students came from low to middle class families. About 72 % of these students’ fathers and 78 % of their mothers had an education level of junior high school or below.

Measures

Narcissism

Narcissistic Personality Inventory for Chinese (NPIC; Zhou et al. 2009) was used in the present study. This inventory was developed based on the Narcissistic Personality Inventory (Raskin and Terry 1988; Emmons 1984, 1987) and validated in China. This inventory showed satisfactory reliability and validity among Chinese (Zhou et al. 2009). Participants rated on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all true) to 6 (completely true). The higher scores on this inventory indicate higher levels of narcissism. The original inventory consists of 34 items, and 2 items (“I am eager to power/我对权力有强烈的欲望”, “I seldom depend on others/我很少依靠别人来完成事情”) were excluded due to low correlations with the total scale score (for the remaining 32 items, see Appendix I). The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the overall inventory was .92.

Friendship Quality

The Chinese version of the Friendships Quality Questionnaire (FQQC; Zou et al. 1998) was used in the present study. Adolescents mentioned a best same-gender friend in their class and then rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = not true at all; 5 = completely true) for how true a particular quality was for their friendship with this specific best same-gender peer. This questionnaire was adapted from the widely used measure, Friendships Quality Questionnaire (Parker and Asher 1993) among Chinese adolescents (Zou et al. 1998). This questionnaire originally includes five subscales: trust & support, companion & entertainment, validation, disclosure & communication, and conflict & betray. To validate this questionnaire among Chinese adolescents, Zou et al. had two psychology graduate students translate the original 40-item English version questionnaire into Chinese; then, asked an English major student to translate the Chinese version back to English. Seven hundred and sixty three adolescents from Grade one in junior high school to Grade three in high school finished the Chinese version FQQ. Exploratory factor analysis extracted five factors. The alpha coefficients of the five factors were .88, .73, .80, .80, and .67 respectively in the scale validation study. In addition, this friendship quality measured could predict adolescents’ loneliness (Zou et al. 1998). Above information suggested that the FQQC had satisfactory reliability and validity.

In the present study, two of the subscales (i.e., companion & entertainment and conflict & betrayal) showed low reliabilities (alpha < .65) and thus these two dimensions were excluded from subsequent analysis. The final questionnaire included 16 items to measure the three dimensions of friendship, trust & support, validation, and disclosure & communication (see Appendix II). A CFA indicated that the measurement of this 16-item scale was adequate (χ 2 /df = 2.32, RMSEA = .05, CFI = .97, NFI = .95, NNFI = .97). The standardized factor loadings of items on the three dimensions of friendship quality ranged from .34 to .69. The Cronbach’s alphas of the trust & support, validation, and disclosure & communication friendship quality dimensions were .72, .67 and .69, respectively.

Results

Descriptive Analysis

To examine grade and gender differences in participants’ narcissism and friendship quality dimensions, a MANOVA was conducted with students’ adolescent grade level and gender as independent variables and narcissism as well as the three domains of friendship quality as dependent variables. Table 1 shows the means and standard deviations for narcissism and subscales of friendship quality for boys and girls in each grade.

Significant multivariate effects were observed for gender, Wilks’ Lambda = .89, F(4, 467) = 15.15, p < .001, η = .12, and for grade, Wilks’ Lambda = .90, F (15, 1550) = 2.37, p < .001, η = .03. The interaction of gender and grade was not significant, Wilks’ Lambda = .96, F (20, 1550) = 1.12, p = .32, η = .01. Examination of the univariate effects revealed that boys (M = 3.65, SD = .81) were more narcissistic than girls (M = 3.45, SD = .75), F (1, 470) = 7.16, p < .01, η = .02. In addition, compared to adolescent boys, adolescent girls reported higher levels of validation (M = 3.76, SD = .65 for females; M = 3.61, SD = .69 for males), F (1, 473) = 7.14, p < .01, and disclosure & communication (M = 4.12, SD = .64 for females; M = 3.73, SD = .74 for males), F (1,473) = 39.87, p < .001. No significant gender differences were found in trust & support. Furthermore, examination of the univariate effects revealed significant grade differences on all three domains of friendship quality, F (5, 470) = 2.69, p < .05 for trust and support, F (5,470) = 3.98, p < .01 for validation, and F (5, 470) = 4.99, p < .001 for disclosure & communication. Tukey’s HSD analysis indicated that students in high school generally reported higher friendship qualities than those in junior high school (see Table 1). No age difference was found for narcissism, F (5, 470) = .89, p = .66.

The Relationship Between Narcissism and Friendship Quality

We hypothesized that narcissism would be positively related to friendship quality dimensions and these associations were expected to be stronger for boys than girls. Consistent with our hypothesis, narcissism was positively correlated with the all three friendship quality dimensions for boys (see Table 2). In contrast, there was no significant correlation between narcissism and girls’ friendship quality dimensions.

To examine gender moderations in the relationships between narcissism and friendship quality dimensions while having a control of the correlated dependent variables (i.e., friendship quality dimensions), multiple-group (by boys and girls) structural equation modeling were conducted using LISREL. We also controlled for participants’ grade to clearly delineate the associations between narcissism and friendship quality dimensions. To specify the model, the items in the friendship quality subscales served as indicators for each friendship quality latent construct. Due to the large amount of items for narcissism, three parcels were created to form the indicators of the narcissism latent construct. Measurement invariance was established before the model comparison (between M1 and M2), Δχ 2(15) = 15.41,p > .05. To examine the gender moderations in the associations, model comparisons were conducted on each path from narcissism to friendship quality. As Table 3 shows, all structural models fit the data adequately.

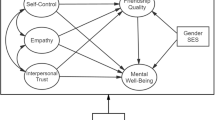

As Figure 1 shows, narcissism was significantly related to all three aspects of friendship quality only for boys (β = .35, p < .01 for trust & support; β = .49, p < .01 for validation; β = .37, p < .01 for disclosure & communication). The paths from narcissism to girls’ friendship qualities were not significant. Model comparisons showed that the path coefficients from narcissism to each aspect of friendship quality were significantly different between boys and girls, Δχ 2 (1) = 6.95, p < .01 for trust & support (between M2 and M3), Δχ 2 (1) = 6.42, p < .01 for validation (between M2 and M4), and Δχ 2 (1) = 9.90, p < .01 for disclosure & communication (between M2 and M5).

Standardized path coefficients for the latent structural model for boys (a) and girls (b). Trust = trust & support; Disclosure = disclosure & communication. To facilitate reading, the path coefficients for the grade covariate were omitted. Dashed lines were used for non-significant path. ***p < .001, **p < .01, *p < .05. a Latent structural model for boys. b Latent structural model for girls

Discussion

The present study examined the associations between narcissism and aspects of friendship quality as well as the gender moderations in these relationships among Chinese adolescents. We found significant gender moderations such that narcissism was positively associated with friendship qualities only among Chinese adolescent boys. These findings highlight the gender-dependent functioning of narcissism in adolescents’ social adjustment. The cultural implications of the current findings are provided.

Narcissism and Friendship Qualities

The present study indicates that narcissism positively relates to friendship qualities, especially for boys. These findings lend support to the dynamic self-regulatory processing model of narcissism (Morf and Rhodewalt 2001), which posits that the primary goal of narcissists is to maintain self-esteem and/or preserve positive self-worth. The validation component of friendship quality may provide an important source of confirmation to one’s self-worth. Therefore, it is not surprise to observe that adolescents with higher narcissistic traits reported more validation from friends. In addition, previous studies have revealed narcissists are charming, extroversive and socially confident (Holtzman and Strube 2010; Paulhus 2001; Wink 1991). These characteristics may help narcissistic adolescents develop supportive relationships and communicate well with others, which positively contributes to friendship quality. These findings indicate cross-cultural similarities such that Chinese narcissistic individuals like their Western counterparts (Morf and Rhodewalt 2001) employ the self-regulated strategies to enhance self views.

On the other hand, the results also suggest that culture may influence the function of narcissism. Theories and studies have showed that narcissistic individuals in Western cultures often perceive themselves positively in reference to agent domains (e.g., intelligence, extroversion, and status), but not in communal domains (e.g., kindness, cooperation, and morality) (Campbell et al. 2007). The present study found that narcissistic adolescents in China also reported positive perceptions of interpersonal relationships in communal domains (i.e., trust & support and disclosure & communication in friendship). These findings imply that the theoretic model developed in Western populations (i.e., dynamic self-regulatory processing model of narcissism) can be applied to the Chinese culture. However, culture also has an influence on the behaviors of narcissistic individuals. In Western countries, individuals highly value independence, and thus narcissistic persons try to maintain their positive self view through enhancing their agentic traits, such as intelligence and status. In collectivistic cultures, people highly value harmonious social relationships (Bond and Wang 1983). Thus, narcissistic adolescents in China may use communal traits or behaviors (i.e., building friendship qualities) to maintain their positive self-view.

The Moderating Effects of Gender

Consistent with previous research (Foster et al. 2003), the current study of Chinese adolescents showed that males were more narcissistic than females, indicating a higher norm of narcissism among males. Western literature has also illustrated that males displayed greater “stereotypically narcissistic” behaviors than females (Rhodewalt et al. 2006; Morf and Weir 2000). For instance, narcissism is more strongly related to overt aggression in boys than in girls (Marsee et al. 2005).

The results of the present studies revealed that narcissism was associated with positive friendship qualities only in boys, which provided the empirical evidence that narcissistic behavior might be more socially acceptable in males than in females. Theorists have suggested that boys and girls in childhood tend to socialize in sex-segregated groups (Maccoby 1990, 1998). Specifically, boys in same sex groups would be expected to engage in more agentic behaviors, such as striving for mastery and power, whereas girls in all-girls groups would be expected to engage in more communal behaviors, such as striving for intimacy and connectedness. For instance, Suh et al. found that men with male friends were more dominant and women with female friends were more agreeable (Suh et al. 2004). In addition, studies also indicated that behaviors in accordance with gender roles tend to be adaptive (Fanti et al. 2009; Wei et al. 2011). Narcissism as a personality trait is characterized by features such as grandiose self-worth, uniqueness, authority, entitlement and self-admiration. These characteristics are typical agentic traits, and some of which (e.g., uniqueness, authority) are considered signs of masculinity (Bem 1975; Zhang et al. 2001). These masculine traits are more acceptable in male groups, and found more in male–male friendship (Suh et al. 2004). Thus, boys’ narcissistic behaviors are consistent with their gender role and are likely to be positively perceived. For example, within friendship, powerful peers are perceived as more supportive by boys, but not by girls (De Goede et al. 2009). In sum, the findings of the present study provide support to the perspective that behaviors and traits consistent with the gender norm are more acceptable and adaptive.

Furthermore, evidences from many previous studies have indicated that whether narcissism is adaptive depends on what aspects of narcissism are considered (Raskin and Terry 1988; Barry et al. 2007) and what kinds of relationships are investigated (Paulhus 1998; Jonason et al. 2009). This research did not differentiate different aspects of narcissism, but suggested that whether narcissism is adaptive depends on the gender of the narcissistic individuals in the friendship realm. It is possible that gender moderation can also be observed with narcissism sub-dimensions in friendship or other relationships, which warrants future investigation.

Limitations and Future Directions

Findings of this study enrich our knowledge of narcissistic self-regulatory strategies in social relationships during adolescence, and call attention to the examination of gender differences and cultural influences regarding social adjustment of narcissistic adolescents. However, several limitations of this study should be noted. First, all data were obtained from self-reported measures, which might have overestimated the positive associations between friendship quality and narcissism. Previous studies have found narcissistic individuals tend to perceive events positively and are capable of defending against negative feedback from others (Foster and Campbell 2005; Rhodewalt and Eddings 2002). Thus, it is possible that the more narcissistic participants might report higher friendship qualities than what was accurate. Nevertheless, the gender variation in the associations between narcissism and friendship qualities has provided some support to the validity of this method: Positive self-bias was not present among all adolescents or perhaps was not strong. Future methodology improvement is greatly needed to determine the extent of positive self-bias in narcissistic adolescents’ self-reports of relationship quality. Future research should use multiple informants and multiple methods to assess both narcissism and friendship quality, such as including peer reports, teacher reports, and observation. In addition, the present study employed a cross-sectional design to investigate narcissism and friendship quality. Thus, we could not examine the causal or long-term relationship between narcissism and adolescents’ adjustment. Future research may use a longitudinal design to examine the development of narcissism and its associations with social adjustment.

In summary, this study examines the gender variations in narcissism and in the relations between narcissism and friendship qualities in adolescents. We found that adolescent boys were more narcissistic than girls. Furthermore, we found that narcissism was related to positive friendship qualities in Chinese adolescent boys, but not girls. Findings of this study contribute to our understanding of the functioning of narcissism in social relationships among adolescents and suggest future research to take gender and cultural background into consideration when investigating narcissism in adolescent development.

References

Back, M. D., Schmukle, S. C., & Egloff, B. (2010). Why are narcissists so charming at first sight? Decoding the narcissism-popularity link at zero acquaintance. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 98, 132–145. doi:10.1037/a0016338.

Barry, T. D., Thompson, A., Barry, C. T., Lochman, J. E., Adler, K., & Hill, K. (2007). The importance of narcissism in predicting proactive and reactive aggression in moderately to highly aggressive children. Aggressive Behavior, 33, 185–197. doi:10.1002/ab.20198.

Barry, C. T., Pickard, J. D., & Ansel, L. L. (2009). The associations of adolescent invulnerability and narcissism with problem behaviors. Personality and Individual Differences, 47, 577–582. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2009.05.022.

Bem, S. L. (1975). Sex role adaptability: One consequence of psychological androgyny. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 31, 634–643. doi:10.1037/h0077098.

Berndt, T. J. (2002). Friendship quality and social development. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 11, 7–10. doi:10.1111/1467-8721.00157.

Berndt, T. J., & Keefe, K. (1995). Friends influence on adolescents adjustment to school. Child Development, 66, 1312–1329. doi:10.2307/1131649.

Bond, M. H., & Wang, S. (1983). China: Aggressive behavior and the problem of maintaining order and harmony. In A. P. Goldstein & M. H. Segall (Eds.), Aggression in global perspective (pp. 58–74). New York: Pergamon.

Bukowski, W. M., Schwartzman, A., Santo, J., Bagwell, C., & Adams, R. (2009). Reactivity and distortions in the self: Narcissism, types of aggression, and the functioning of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis during early adolescence. Development & Psychopathology, 21, 1249–1262. doi:10.1017/S0954579409990149.

Bushman, B. J., Bonacci, A. M., Van Dijk, M., & Baumeister, R. F. (2003). Narcissism, sexual refusal, and aggression: Testing a narcissistic reactance model of sexual coercion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 1027–1040. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.84.5.1027.

Bushman, B. J., Baumeister, R. F., Thomaes, S., Ryu, E., Begeer, S., & West, S. G. (2009). Looking again, and harder, for a link between low self-esteem and aggression. Journal of Personality, 77, 427–446. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2008.00553.x.

Campbell, W. K., Foster, C. A., & Finkel, E. J. (2002). Does self-love lead to love for others? A story of narcissistic game playing. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 83, 340–354. doi:10.1037//0022-3514.83.2.340.

Campbell, W. K., Bosson, J. K., Goheen, T. W., Lakey, C. E., & Kernis, M. H. (2007). Do narcissists dislike themselves “deep down inside”? Psychological Science, 18, 227–229. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01880.x.

Carlson, K. S., & Gjerde, P. F. (2009). Preschool personality antecedents of narcissism in adolescence and young adulthood: A 20-year longitudinal study. Journal of Research in Personality, 43, 570–578. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2009.03.003.

Cillessen, A. H. N., Jiang, X. L., West, T. V., & Laszkowski, D. K. (2005). Predictors of dyadic friendship quality in adolescence. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 29, 165–172. doi:10.1080/01650250444000360.

De Goede, I. H. A., Branje, S. J. T., & Meeus, W. H. J. (2009). Developmental changes and gender differences in adolescents’ perceptions of friendships. Journal of Adolescence, 32, 1105–1123. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.03.002.

Demir, M., & Urberg, K. A. (2004). Friendship and adjustment among adolescents. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 88, 68–82. doi:10.1016/j.jecp.2004.02.006.

Eaton, J., Struthers, C., & Santelli, A. G. (2006). Dispositional and state forgiveness: The role of self-esteem, need for structure, and narcissism. Personality & Individual Differences, 41, 371–380. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2006.02.005.

Emmons, R. A. (1984). Factor analysis and construct validity of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory. Journal of Personality Assessment, 48, 291–300. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa4803_11.

Emmons, R. A. (1987). Narcissism: Theory and measurement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 11–17. doi:0022-3514/87/S00.75.

Fanti, K. A., Brookmeyer, K. A., Henrich, C. C., & Kuperminc, G. P. (2009). Aggressive behavior and quality of friendships: Linear and curvilinear associations. Journal of Early Adolescence, 29, 826–838. doi:10.1177/0272431609332819.

Fossati, A., Borroni, S., Eisenberg, N., & Maffei, C. (2010). Relations of proactive and reactive dimensions of aggression to overt and covert narcissism in nonclinical adolescents. Aggressive Behavior, 36, 21–27. doi:10.1002/ab.20332.

Foster, J. D., & Campbell, W. K. (2005). Narcissism and resistance to doubts about romantic partners. Journal of Research in Personality, 39, 550–557. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2004.11.001.

Foster, J. D., Campbell, W., & Twenge, J. M. (2003). Individual differences in narcissism: Inflated self-views across the lifespan and around the world. Journal of Research in Personality, 37, 469–486. doi:10.1016/S0092-6566(03)00026-6.

Foster, J. D., Misra, T. A., & Reidy, D. E. (2009). Narcissists are approach-oriented toward their money and their friends. Journal of Research in Personality, 43, 764–769. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2009.05.005.

Fukunishi, I., Nakagawa, T., Nakamura, H., Li, K., Hua, Z. Q., & Kratz, T. S. (1996). Relationships between type A behavior, narcissism, and maternal closeness for college students in Japan, the United States of America, and the People’s Republic of China. Psychological Reports, 78, 939–944. doi:10.2466/pr0.1996.78.3.939.

Gaertner, A., Fite, P., & Colder, C. (2010). Parenting and friendship quality as predictors of internalizing and externalizing symptoms in early adolescence. Journal of Child & Family Studies, 19, 101–108. doi:10.1007/s10826-009-9289-3.

Grotpeter, J. K., & Crick, N. R. (1996). Relational aggression, overt aggression, and friendship. Child Development, 67, 2328–2338. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.1996.tb01860.x.

Hartup, W. W. (1996). The company they keep: Friendships and their developmental significance. Child Development, 67, 1–13. doi:10.2307/1131681.

Holtzman, N. S., & Strube, M. J. (2010). Narcissism and attractiveness. Journal of Research in Personality, 44, 133–136. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2009.10.004.

Jonason, P. K., Li, N. P., Webster, G. W., & Schmitt, D. P. (2009). The Dark Triad: Facilitating short-term mating in men. European Journal of Personality, 23, 5–18. doi:10.1002/per698.

Kwan, V. S. Y., Kuang, L. L., & Hui, N. H. H. (2009). Identifying the sources of self-esteem: The mixed medley of benevolence, merit, and bias. Self and Identity, 8, 176–195. doi:10.1080/15298860802504874.

Lai, J., Zheng, G., & Liu, F. (2006). 中学生同伴关系对自尊影响的研究 [The Effect of Peer Relationship on Self-esteem of Middle School Students]. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 16, 74–76.

Lansford, J. E., Putallaz, M., Grimes, C. L., Schiro-Osman, K. A., Kupersmidt, J. B., & Coie, J. D. (2006). Perceptions of friendship quality and observed behaviors with friends: How do sociometrically rejected, average, and popular girls differ? Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 52, 694–719. doi:10.1353/mpq.2006.0036.

Lapsley, D. K., & Aalsma, M. C. (2006). An empirical typology of narcissism and mental health in late adolescence. Journal of Adolescence, 29, 53–71. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2005.01.008.

Li, D. Y., & Gao, X. M. (2011). Research on the relationship between covert narcissism and aggression. Health Medicine Research and Practice, 8(3), 29–31.

Maccoby, E. E. (1990). Gender and relationships: A developmental account. American Psychologist, 45, 513–520. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.45.4.513.

Maccoby, E. E. (1998). The two sexes: Growing up apart, coming together. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Marsee, M. A., Silverthorn, P., & Frick, P. J. (2005). The association of psychopathic traits with aggression and delinquency in non-referred boys and girls. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 23, 803–817. doi:10.1002/bsl.662.

Morf, C. C., & Rhodewalt, F. (2001). Unraveling the paradoxes of narcissism: A dynamic self-regulatory processing model. Psychological Inquiry, 12(4), 177–196. doi:10.1207/S15327965PLI1204_1.

Morf, C. C., & Weir, C. (2000). Narcissism and intrinsic motivation: The role of goal congruence. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 36, 424–438. doi:10.1006/jesp.1999.1421.

Oyserman, D., Coon, H. M., & Kemmelmeier, M. (2002). Rethinking individualism and collectivism: Evaluation of theoretical assumptions and meta-analyses. Psychological Bulletin, 128, 3–72. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.128.1.3.

Parker, J. G., & Asher, S. R. (1993). Friendship and friendship quality in middle childhood: Links with peer group acceptance and feelings of loneliness and social dissatisfaction. Developmental Psychology, 29, 611–621. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.29.4.611.

Parker, J. G., Walker, A. R., Low, C. M., & Gamm, B. K. (2005). Friendship. Jealousy in young adolescents: Individual differences and links to sex, self-esteem, aggression, and social adjustment. Developmental Psychology, 41, 235–250. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.41.1.235.

Paulhus, D. L. (1998). Interpersonal and intrapsychic adaptiveness of trait self-enhancement: A mixed blessing? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 1197–1208. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.74.5.1197.

Paulhus, D. L. (2001). Normal narcissism: Two minimalist accounts. Psychological Inquiry, 12, 228–230.

Raskin, R., & Terry, H. (1988). A principal-components analysis of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory and further evidence of its construct validity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 890–902. doi:10.1037//0022-3514.54.5.890.

Rhodewalt, F., & Eddings, S. K. (2002). Narcissus reflects: Memory distortion in response to ego relevant feedback in high and low narcissistic men. Journal of Research in Personality, 36, 97–116. doi:10.1006/jrpe.2002.2342.

Rhodewalt, F., Tragakis, M. W., & Finnerty, J. (2006). Narcissism and self-handicapping: Linking self-aggrandizement to behavior. Journal of Research in Personality, 40, 573–597. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2005.05.001.

Ryan, K., Weikel, K., & Sprechini, G. (2008). Gender differences in narcissismand courtship violence in dating couples. Sex Roles, 58, 802–813. doi:10.1007/s11199-008-9403-9.

Sedikides, C., Gregg, A. P., Rudich, E. A., Kumashiro, M., & Rusbult, C. (2004). Are normal narcissists psychologically healthy? Self-esteem matters. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87, 400–416. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.87.3.400.

Song, G. W., & Li, J. W. (2010). 大学生自恋内隐观研究 [College students’ implicit views about narcissism]. Educational Research and Experiment, 5, 89–92.

Suh, E. J., Moskowitz, D. S., Fournier, M. A., & Zuroff, D. C. (2004). Gender and relationships: Influences on agentic and communal behaviors. Personal Relationships, 11, 41–59. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6811.2004.00070.x.

Tanchotsrinon, P., Maneesri, K., & Campbell, W. K. (2007). Narcissism and romantic attraction: Evidence from a collectivistic culture. Journal of Research in Personality, 41, 723–730. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2006.08.004.

Thomaes, S., Bushman, B. J., Stegge, H., & Olthof, T. (2008). Trumping shame by blasts of noise: Narcissism, self-esteem, shame, and aggression in young adolescents. Child Development, 79, 1792–1801. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01226.x.

Waldrip, A. M., Malcolm, K. T., & Jensen-Campbell, L. A. (2008). With a little help from your friends: The importance of high-quality friendships on early adolescent adjustment. Social Development, 17, 832–852. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9507.2008.00476.x.

Way, N., & Greene, M. L. (2006). Trajectories of perceived friendship quality during adolescence: The patterns and contextual predictors. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 16, 293–320. doi:10.1111/j.1532-7795.2006.00133.x.

Wei, H., Fan, C. Y., Zhou, Z. K., Tian, Y., & Yuan, Y. L. (2011). 不同性别儿童的关系攻击友谊质量和孤独感的关系 [Relationships of relational aggression, friendship quality and loneliness in children of different gender]. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 19, 681–683.

Wink, P. (1991). Two faces of narcissism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61, 590–597. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.61.4.590.

Youngblade, L., & Belsky, J. (1992). Parent–child antecedents of five-year-olds’ close friendships: A longitude analysis. Developmental psychology, 28, 700–713. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.28.

Zhang, J., Norvilitis, J. M., & Jin, S. (2001). Measuring gender orientation with the Bem Sex Role Inventory in Chinese culture. Sex Roles, 44, 237–2511. doi:10.1023/A:1010911305338.

Zhou, H., Zhang, B., Chen, L. W., & Ye, M. Y. (2009). 自恋人格问卷的编制及信效度检验 [Development and validation of Narcissistic Personality Inventory for Chinese]. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 17, 5–7.

Zou, H., Zhou, H., & Zhou, Y. (1998). 中学生友谊、友谊质量与同伴接纳的关系 [The relationships among middle school students’ friendship, friendship quality and peer acceptance]. Journal of Beijing Normal University (Social Science), 1, 43–50.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities from China.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix I

Appendix II

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, H., Li, Y., Zhang, B. et al. The Relationship Between Narcissism and Friendship Qualities in Adolescents: Gender as a Moderator. Sex Roles 67, 452–462 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-012-0169-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-012-0169-8