Abstract

The purpose of the present research was to test the mediating roles of body shame and appearance anxiety in the relation between self-surveillance and self-esteem; and to investigate whether gender (male, female) and stereotypical gender roles (masculinity, femininity) moderated the proposed mediation model. Canadian undergraduate university men and women (n = 198) completed measures of self-surveillance, gender, gender roles, body shame, appearance anxiety, and self-esteem. Regression analyses demonstrated that greater self-surveillance predicted lower self-esteem, and this relation was fully mediated by body shame and appearance anxiety. With the exception of masculinity interacting with self-surveillance to predict body shame and appearance anxiety, neither gender nor stereotypical gender roles moderated the proposed paths. Implications are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In western culture, people are bombarded with sexualized images of women (Bartky 1990; Kilbourne 2002; Stankiewicz and Rosselli 2008; Wolf 1991). The socialization of women as sexualized objects in this cultural context can encourage self-objectification in women, that is, to perceive oneself from a third-person perspective (Frederickson and Roberts 1997). Empirical research has demonstrated that self-objectification is related to more negative mental health outcomes among women (Moradi and Huang 2008). Some research implies that self-objectification might also be harmful to men (e.g., Fredrickson et al. 1998; Hebl 2004; Smolak and Murnen 2008; Tiggemann and Kuring 2004). Like other western nations, body image dissatisfaction is prevalent among young Canadian women (McCreary Centre Society 1999) and men (McCreary and Sasse 2000). The present research studied links between self-objectification and global appraisals of self-worth in a sample of Canadian undergraduate men and women. Based on objectification theory, we tested body shame and appearance anxiety as mediators of the anticipated negative association between self-objectification and self-esteem. We also examined whether the proposed mediation paths were moderated by gender or stereotypical gender roles, as women and men’s unique socialization experiences might impact perceptions of the self related to the body, and more general perceptions of self-worth.

Objectification Theory

According to Frederickson and Roberts’ (1997) objectification theory, socio-cultural contexts in which women are presented as sex objects socialize girls and women to view themselves from an observer’s vantage—one in which women are perceived as objects, valued for their physical appearance. Fredrickson and Roberts labelled the internalization of a third-person perspective ‘self-objectification’. Self-objectifying is characterized by habitual body-monitoring, self-surveillance, and self-evaluation (see also McKinley and Hyde 1996), and is thought to relate to several mental health problems. Over a decade of research, conducted primarily on American and Australian women, has provided considerable support for objectification theory (for a review, see Moradi and Huang 2008), demonstrating that higher self-objectification among women is associated with disordered eating (Calogero et al. 2005; Greenleaf 2005; Greenleaf and McGreer 2006; Noll and Frederickson 1998; Slater and Tiggemann 2002), depression (Grabe et al. 2007; Szymanski and Henning 2007; Tiggemann and Kuring 2004), and sexual dysfunction (Calogero and Thompson 2009; Impett et al. 2006; Sanchez and Kiefer 2007; Steer and Tiggemann 2008).

In proposing objectification theory, Frederickson and Roberts (1997) extended Cooley (1990) assertion that perceptions of the self correspond to an individual’s notion of how other people see them. For women, ‘sense of self’ has a great deal to do with evaluations of the body. Indeed, previous research has shown that greater dissatisfaction with one’s physical appearance is related to a compromised view of one’s more global sense of self-worth (Friestad and Rise 2004; Ganem et al. 2009; Tiggemann 2005)—typically measured in terms of self-esteem (Baumeister et al. 2003; Robins et al. 2001; Rosenberg 1965). As such, women who self-objectify might have a particularly poor sense of their self-worth, as reflected in poor self-esteem. Consistent with these ideas, a number of researchers have documented a negative association between self-objectification and self-esteem among American and Australian women (Lowery et al. 2005; McKinley 2006; Strelan et al. 2003; but see Strelan and Hargreaves 2005). Thus, although the original formulation of objectification theory focused on the associated mental health challenges (e.g., depression, disordered eating), self-objectification might also have broad implications for women’s self-concepts, including their self-esteem.

Self-Objectification: A Problem for Women Only?

Objectification theory was originally proposed to explain the experiences of girls and women living in a culture characterized by pervasive sexual objectification of women. According to Frederickson and Roberts (1997), sexual objectification of women occurs in several social arenas, the most ominous being media. Men, too, are increasingly being objectified in western media (Leit et al. 2001; Pope et al. 2001), with the idealized male image becoming more muscular and unattainable (Olivardia et al. 2004). Related evidence indicates that men are less satisfied with their bodies than they were in the past (e.g., Garner 1997). Objectification theory, therefore, might provide a theoretical framework for understanding how men might come to self-objectify, and what the potential outcomes might be (see also Morrison et al. 2003; Strelan and Hargreaves 2005). If men become increasingly socialized toward greater self-objectification, for example, this could lead to negative mental health outcomes as well as compromised views of self-worth. In support of these notions, researchers have found that greater self-objectification among American and Australian men is associated with disordered eating (Tiggemann and Kuring 2004), depression (Grabe et al. 2007), and lower self-esteem (McKinley 2006; Strelan and Hargreaves 2005; but see Lowery et al. 2005).

Primary Mediators: Body Shame and Appearance Anxiety

In addition to delineating potential negative mental health outcomes associated with self-objectification, objectification theory also specifies various processes thought to be responsible for these associations. According to Frederickson and Roberts (1997), links between self-objectification and mental health problems can be attributed to a variety of mediating mechanisms. Specifically, self-objectification is proposed to foster body shame, appearance anxiety, interrupted flow (i.e., reduced concentration in activities), and reduced awareness of internal bodily states. These processes, in turn, are theorized to foster mental health consequences including disordered eating, depression, and sexual dysfunction. Of these purported mediators, body shame and appearance anxiety have received the most attention and empirical support (Moradi and Huang 2008).

With respect to body shame, individuals who self-objectify are thought to compare themselves to an internalized cultural ideal; any perceived discrepancy in which the actual self is thought to be inferior to the desired self promotes body shame (Frederickson and Roberts 1997; Frederickson et al. 1998). Given that the idealized female body is almost universally unattainable (Wolf 1991), the majority of women are likely to experience some degree of body shame; however, body shame should be especially likely among those who self-objectify. Similarly, as the male ideal portrayed in the media becomes increasingly physically stereotyped and unattainable, greater self-objectification might be linked with greater body shame among men. Consonant with these proposals, self-objectification has been linked with greater body shame among both women and men in western nations (Calogero 2009; Grabe et al. 2007; Knauss et al. 2008; McKinley 1998). Greater body shame has also been shown to explain the relations between self-objectification and disordered eating among American, Australian, and British women (e.g., Calogero 2009; Frederickson et al. 1998; Noll and Frederickson 1998; Prichard and Tiggemann 2005), and between self-objectification and depressive symptoms among both women and men (e.g., Grabe et al. 2007). Further, in a study of American women only, Mercurio and Landry (2008) showed that body shame accounted for the relation between higher self-objectification and poorer self-esteem.

Importantly, although we surmise that these processes could be relevant to the experiences of women and men, it is clear that women in western cultures self-objectify to a greater degree than do men, and tend to experience higher levels of body shame (e.g., Calogero 2009; Frederickson et al. 1998; Grabe et al. 2007; Hebl et al. 2004; Lindberg et al. 2007; Lowery et al. 2005; McKinley 1998; Knauss et al. 2008; Strelan and Hargreaves 2005; Tiggemann and Kuring 2004). Additional gender differences have emerged in the patterns of associations, including the directions and magnitudes of the correlations among self-objectification, body shame, and mental health outcomes (Calogero 2009; Lindberg et al. 2007; McKinley 1998; Tiggemann and Kuring 2004). Yet several studies have also shown that many of these relations are similar for men and women from western nations (e.g., Calogero 2009; Grabe et al. 2007; Knauss et al. 2008; Lindberg et al. 2007; McKinley 1998, 2006). Thus, even though research has illustrated that body shame can account for the relations between self-objectification and mental health problems, there exists evidence for both consistency and divergence between women and men in these relations.

The mediating role of appearance anxiety, in contrast to body shame, is relatively less studied in the literature on objectification theory. Self-objectifying is theorized to promote anxiety specific to when and how one’s body and appearance might be judged (Frederickson and Roberts 1997). Several studies report associations between greater self-objectification and greater appearance anxiety among American and Australian women (Greenleaf and McGreer 2006; Slater and Tiggemann 2002; Szymanski and Henning 2007; Tiggemann and Kuring 2004) and among Australian men (Hallsworth et al. 2005; Tiggemann and Kuring 2004). However, whereas some researchers have found associations between appearance anxiety and both disordered eating and depression among women (e.g., Greenleaf and McGreer 2006; Szymanski and Henning 2007; Tiggemann and Kuring 2004), as well as between appearance anxiety and depression among men (Tiggemann and Kuring 2004), others have not (e.g., Muehlenkamp et al. 2005; Slater and Tiggemann 2002). Further, appearance anxiety has not been investigated as a potential mediating mechanism between self-objectification and self-esteem for either women or men. Thus, the mediating role of appearance anxiety is less well established.

Self-Objectification and Stereotypical Gender Roles

According to objectification theory (Frederickson and Roberts 1997), it is the socialized internalization of an observer’s perspective that is harmful to the mental health of women. That is, the unique socialization experiences of women in western cultures are thought to be responsible for their poorer mental health. Consequently, previous research on objectification theory has tended to focus exclusively on the moderating role of gender (i.e., self-identification as female or male). Importantly, though, gender roles instruct individuals on how to think, feel, and behave as women or men in a specific cultural context. Stereotypical feminine and masculine gender role characteristics can be assessed using measures of communion and agency, respectively (Bakan 1966; Ghaed and Gallo 2006; Spence et al. 1975). Although women tend to score higher on communion and men higher on agency, both women and men vary in terms of their reported femininity and masculinity (e.g., Ghaed and Gallo 2006). Consequently, dimensional measures of stereotypical feminine and masculine gender roles are not redundant with categorical measures of gender. As such, an examination of both gender and gender roles seems particularly relevant to understanding the consequences of self-objectification.

In their objectification theory, Frederickson and Roberts (1997) highlight the central role of gendered socialization experiences. Given this, the extent of internalization of cultural standards related to gender roles, in particular, should moderate the link between self-objectification and outcomes, such as self-esteem. Highly feminine individuals possess characteristics such as being concerned with how others are doing and feeling, as well as kindness and helpfulness. As such, individuals who strongly subscribe to stereotypical feminine gender roles may be most vulnerable to self-objectification, and thus most susceptible to its negative effects. In contrast, people who strongly endorse stereotypical masculine gender roles possess traits such as independence, self-confidence, and a sense of agency. Such individuals may be relatively less vulnerable to self-objectification and the associated negative outcomes, because the socialization pressures to view oneself as an object to be used by others should be lower. Further still, gender could interact with gender roles. In particular, if the socialized internalization of an observer’s perspective is more typical of the experiences of young girls and women (compared to boys and men), then women who strongly endorse stereotypical feminine gender roles might be particularly likely to engage in self-objectification and, therefore, may be at greatest risk for negative outcomes, including a compromised sense of self-worth.

Summary

Consistent with objectification theory, greater self-objectification among women has been linked with a range of negative mental health outcomes among women. Such outcomes might also include a compromised sense of global self-worth. Although objectification theory was originally developed to address women’s experiences, similar processes—and potential negative outcomes—could be increasingly relevant to men’s socialization experiences. The possible utility of objectification theory for understanding men’s experiences, however, is not well understood. With respect to the mechanisms identified by objectification theory as linking self-objectification with negative outcomes, research has illustrated that body shame can account for the relations between self-objectification and mental health problems, as well as self-esteem—particularly among women. In contrast, the mediating role of appearance anxiety is unclear. Few published studies have examined these hypothesized mediators jointly in studies of self-objectification among women and men. Finally, whereas objectification theory is concerned with gendered socialization experiences, researchers to date have examined gender, rather than the degree of internalization of stereotypical feminine or masculine gender roles. In this regard, understanding an individual’s gender and her or his beliefs about stereotypical gender roles seems particularly pertinent to objectification theory.

The Present Work

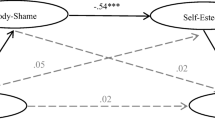

In the present research, we examined the link between self-surveillance (a manifestation of self-objectification) and self-esteem in a sample of Canadian undergraduate women and men. We extended current literature by testing body shame and appearance anxiety jointly as mediators of the anticipated negative relation between self-surveillance and self-esteem among women and men. Also unique to the present study, we investigated whether gender, gender roles, and the interaction between gender and gender roles moderated the hypothesized mediation model linking self-surveillance and self-esteem via body shame and appearance anxiety (see Fig. 1). Consistent with the approach to testing moderated mediation outlined by Baron and Kenny (1986), nine hypotheses were examined.

Hypothesis 1

Consistent with objectification theory and previous research showing that the experience and effects of self-objectification are more severe for women than for men (e.g., Calogero 2009; Frederickson et al. 1998; Lindberg et al. 2007), we predicted that women would report higher self-surveillance, higher body shame, greater appearance anxiety, and lower self-esteem compared to men.

Hypotheses 2 to 5—Mediation Testing

In line with objectification theory and previous research (e.g., Frederickson and Roberts 1997; Lowery et al. 2005; McKinley 2006; Mercurio and Landry 2008), we hypothesized that higher self-surveillance would predict lower self-esteem (Hypothesis 2). Further, we predicted that greater self-surveillance would be related to the two proposed mediators: greater body shame and greater appearance anxiety (Hypothesis 3). We also anticipated that—independent of self-surveillance—greater body shame and greater appearance anxiety would be associated with lower self-esteem (Hypothesis 4). Moreover, we hypothesized that body shame and appearance anxiety would mediate the proposed negative association between self-surveillance and self-esteem (Hypothesis 5).

Hypotheses 6 to 9—Moderated Mediation

We hypothesized that gender would moderate the mediation model shown in Fig. 1, such that all of the predictive paths would be stronger for women than for men (Hypothesis 6). We further anticipated that gender roles would also moderate the proposed mediation model such that the predictive paths would be stronger among women and men who endorsed a greater stereotypical feminine gender role (Hypothesis 7) and weaker for those who endorsed a greater stereotypical masculine gender role (Hypothesis 8). Finally, we anticipated an interaction, such that, of the possible combinations of gender and gender roles, the predictive paths in the mediation model would be especially strong among women who greatly endorsed a stereotypical feminine gender role (Hypothesis 9).

Method

Participants and Procedure

Participants were undergraduate women and men (N = 200) from a mid-sized city in Ontario, Canada who participated in exchange for course credit or $20. Data from two men who provided inconsistent responses were excluded resulting in a final sample of 100 women and 98 men (M age = 19.8; SD = 2.17, range 18 to 32). These participants were part of a larger investigation on sexuality and individual differences (see Pozzebon et al. 2009; Visser et al. 2010). The average body mass index (BMI) among the female participants was in the normal range (World Health Organization Global Database on Body Mass Index 2010; M = 24.56; SD = 4.65). The majority of participants who indicated their ethnicity identified themselves as White/Caucasian (86.6%), followed by Asian (4.8%), East Indian (4.2%), Black (3.7%) and Other (0.5%). In small same-gender groups, two female experimenters seated participants at individual cubicles where a curtain was drawn. Participants first read and signed consent forms, and then completed the study survey which included measures (in the following order) of: demographics, appearance anxiety, self-esteem, self-surveillance, body shame, and gender roles. Written debriefing was provided.

Measures

Self-Surveillance

To measure self-surveillance, participants completed the Surveillance subscale of the Objectified Body Consciousness Scale (OBCS; McKinley and Hyde 1996). Construct validity has been established in previous research (see McKinley and Hyde 1996). Participants responded to eight items (e.g., “I often worry about whether the clothes I am wearing make me look good”) from 1 (strongly agree) to 6 (strongly disagree). Scores were created by averaging the items. Higher scores indicated greater self-surveillance (α = .83 for women; .85 for men).

Body Shame

Body shame was assessed with the Body Shame subscale of the Objectified Body Consciousness Scale (OBCS; McKinley and Hyde 1996). Construct validity has been established previously (see McKinley and Hyde 1996). Participants indicated their agreement with eight items (e.g., When I’m not the size I think I should be I feel ashamed) on a scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). Scores were created by averaging the items, with higher scores signifying greater body shame (α = .84 for women,.79 for men).

Appearance Anxiety

To measure appearance anxiety, participants completed the Appearance Anxiety Scale (Dion et al. 1990). Individuals scoring high on the appearance anxiety scale have been shown to report public self-consciousness and dissatisfaction with ones appearance (Dion et al. 1990). Participants responded to 14 items (e.g., I worry about how others are evaluating how I look) on a scale from 0 (never) to 4 (almost always). Scores were computed by averaging the items, with higher scores indicating greater anxiety about one’s physical appearance (α = .89 for women; .90 for men).

Self-Esteem

Rosenberg’s (1965) 10-item self-esteem inventory was administered. Rosenberg’s self-esteem scale has been widely used and shown validity in a diversity of samples. On a 4-point scale from 1 (strongly agree) to 4 (strongly disagree) participants indicated the extent to which each statement (e.g., I feel that I have a number of good qualities) represented their feelings toward themselves. Scores were computed by averaging the items, with higher scores indicating higher self-esteem (α = .86 for women; .83 for men).

Gender

Participants indicated whether they were female (coded as 0) or male (1).

Gender Roles

To measure stereotypical masculine and feminine gender roles, participants completed the extended version of the Personal Attributes Questionnaire (EPAQ, Spence et al. 1973). For purposes of the present study, we were interested in the two subscales that assessed stereotypical masculine and feminine gender roles (see Ghaed and Gallo 2006): Agency and Communion, respectively. Participants indicated the extent to which each item described them on a scale from A (not at all) to E (very); these ratings were recoded as numeric scores ranging from 1 to 5. The eight agency (e.g., independent) items were averaged and the eight communion (e.g., emotional) items were averaged to create scores for each subscale; higher scores indicated greater stereotypical masculine (i.e., agency; α = .68 for women; .66 for men) and feminine (i.e., communion; α = .77 for women; .73 for men) gender roles.

Results

A small number of missing values (1%) were replaced with the sample means. Means, standard deviations, and zero-order correlations among study variables are shown in Table 1 for women and men. The correlation between femininity and masculinity was non-significant among men and women, consistent with previous research (Helgeson and Fritz 1999). To test for mean-level differences between women and men (Hypothesis 1), a one-way multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was run with participant gender as the independent variable and self-surveillance, body shame, appearance anxiety, and self-esteem as (unstandardized) dependent variables. The multivariate effect for gender was significant; F (6, 191) = 6.25, p < .001, η 2 = .16. In support of Hypothesis 1, the follow-up univariate tests showed that women, compared to men, reported greater self-surveillance, greater body shame, greater appearance anxiety, and lower self-esteem (see Table 1).

A series of hierarchical regression analyses were conducted to test the proposed mediation model (see Fig. 1) following the steps outlined by Baron and Kenny (1986). Regression models were run to determine whether greater self-surveillance predicted lower self-esteem (Hypothesis 2); greater self-surveillance predicted greater body shame and appearance anxiety (Hypothesis 3); greater body shame and appearance anxiety, independent of self-surveillance, predicted lower self-esteem (Hypothesis 4); and body shame and appearance anxiety mediated the anticipated negative association between self-surveillance and self-esteem (Hypothesis 5). To test the hypothesized moderating roles of gender and gender roles in this mediation model (Hypothesis 6 through 9), two-way and three-way statistical interactions involving gender and gender roles were included in each regression model, as detailed below. Note that although our hypotheses were limited to a subset of these interactions, all two-way interaction effects were included in each model in order to ensure unbiased estimates of the three-way interactions involving gender and gender roles. In all regression analyses, standardized variables were used and interaction terms were computed using these standardized values (see Aiken and West 1991).

In the first hierarchical regression model, self-esteem was regressed onto self-surveillance in step 1, followed by the proposed moderators (gender, femininity, masculinity) in step 2, and the interactions involving self-surveillance and the moderators in step 3 (see Table 2). As shown in Table 2, consistent with Hypothesis 2, at each step greater self-surveillance predicted lower self-esteem. In addition, at steps 2 and 3, greater masculinity predicted greater self-esteem, whereas gender and femininity were non-significant. Further, contrary to Hypotheses 6, 7, 8, and 9, each of the interactions were non-significant at step 3, demonstrating that gender and gender roles did not moderate the link between self-surveillance and self-esteem.

Second, to assess the relations between self-surveillance and the proposed mediating variables, two regressions were run in which body shame and appearance anxiety were regressed onto self-surveillance in step 1, followed by the proposed moderators (gender, femininity, masculinity) in step 2, and the interactions involving the moderators in step 3 (see Table 3). As displayed in Table 3, consistent with Hypothesis 3, greater self-surveillance predicted greater body shame and appearance anxiety at each step. At step 2, lower masculinity predicted greater body shame, and at step 3, lower femininity predicted greater body shame; gender was not significant at either step. In addition, at steps 2 and 3 in the model predicting appearance anxiety, lower masculinity predicted greater appearance anxiety, whereas gender and femininity were non-significant. Further, contrary to Hypotheses 6 and 7, but supporting Hypothesis 8, at step 3 of the models predicting body shame and appearance anxiety, the interaction between masculinity and self-surveillance was significant. Additionally, the interaction between gender and femininity predicting body shame was significant. The remaining interactions were non-significant in both models, demonstrating that, with two exceptions, gender and gender roles did not moderate the links between self-surveillance and body shame and appearance anxiety.

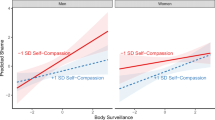

To explore the nature of the interactions between masculinity and self-surveillance predicting body shame and appearance anxiety, simple slopes analyses were run (see Aiken and West 1991). Simple slopes were probed at 1 SD above and 1 SD below the mean on masculinity. For the regression of body shame on self-surveillance, the simple slope was positive and statistically significant at high and low levels of masculinity, but the slope was weaker at high levels of masculinity, b = .43, p < .001; than at low levels of masculinity, b = .68, p < .001. Similarly, for the regression of appearance anxiety on self-surveillance, the simple slope was positive and statistically significant at high and low levels of masculinity, but the slope was weaker at high levels of masculinity, b = .30, p = .009; than at low levels of masculinity, b = .61, p < .001. That is, the less individuals characterized themselves as stereotypically masculine, the stronger the positive relation between self-surveillance with body shame and appearance anxiety.

To explore the nature of the interaction between gender and femininity predicting body shame, a simple slopes analysis was run. Simple slopes were probed at the values of 0 (women) and 1 (men) for gender. For the regression of body shame on femininity, the simple slope was negative and statistically significant among women, b = −.21, p = .034; however, among men, the simple slope was not significant, b = .16, p = .090. That is, the more that women characterized themselves as stereotypically feminine, the lower their body shame; whereas, the more that men characterized themselves as stereotypically feminine, the greater the body shame.

A third hierarchical regression analysis was performed to determine the unique association between the hypothesized mediators and self-esteem, as well as whether these mediators explained the relation between self-surveillance and self-esteem. To do so, self-esteem was regressed onto self-surveillance in step 1, followed by body shame and appearance anxiety in step 2, followed by gender and gender roles in step 3, followed by the interactions involving gender and gender roles in step 4 (see Table 4). As shown in Table 4, greater self-surveillance predicted lower self-esteem at step 1, whereas self-surveillance dropped to non-significance at step 2 after the addition of body shame and appearance anxiety—both of which were significant at steps 2, 3, and 4, consistent with Hypothesis 4. These results indicate that body shame and appearance anxiety fully mediated the relation between self-surveillance and self-esteem, supporting Hypothesis 5. Further, greater masculinity predicted higher self-esteem at steps 3 and 4, whereas the effects of gender and femininity were non-significant. Finally, contrary to Hypotheses 6, 7, 8, and 9, each of the interactions were statistically non-significant at step 4, indicating that gender, gender roles, and their interactions did not moderate the mediation model involving self-surveillance, body shame, appearance anxiety, and self-esteem.

Note that in the final step of this regression model, two interaction terms, self-surveillance by femininity and body shame by femininity, had high multicollinearity with the other predictors (i.e., VIF values of 11 and 15 respectively). Although multicollinearity is not uncommon when multiple interaction terms derived from the same set of predictors are examined simultaneously (Aiken and West 1991), condition indices suggested that multicollinearity was not a serious problem in our data. Further details are available from the first author.

Discussion

Extending previous research on self-objectification (Frederickson and Roberts 1997; for a review, see Moradi and Huang 2008), we tested whether the link between self-surveillance and self-esteem was mediated by body shame and appearance anxiety. Novel to the objectification theory literature, we tested gender, gender roles (femininity and masculinity), and their interaction, as potential moderators of the proposed mediation model.

Self-Objectification and Self-Esteem

Frederickson and Roberts (1997) asserted that women’s sense of self is largely dependent on how they feel about their bodies; as such, we predicted that those who self-objectify would report a poor sense of self-worth. Consistent with this hypothesis, we found that greater self-surveillance predicted lower self-esteem. The link between self-surveillance and self-esteem in the present study was consistent between women and men (see also McKinley 2006).

The present research, in combination with other works (e.g., Choma et al. 2007; Choma et al. 2009; McKinley 1999; Mercurio and Landry 2008; Sinclair and Myers 2004), suggests that the negative effects of self-objectification extend to (less) positive psychological functioning. According to Keyes’ notion of ‘complete mental health’ (Keyes 2005, 2007), mental illness and mental health are related but distinct phenomenon that both need to be considered. Although Fredrickson and Roberts did not address implications of self-objectification for positive psychological functioning per say, objectification theory might serve as a useful framework for understanding why those who self-objectify exhibit low levels of positive mental health (e.g., self-esteem), in addition to psychological disorders.

The Mediating Roles of Body Shame and Appearance Anxiety

A central purpose of the present research was to test body shame and appearance anxiety as mediators simultaneously. As expected (Hypothesis 3), higher body shame and appearance anxiety each uniquely predicted higher self-surveillance, as well as lower self-esteem (Hypothesis 4). Of greater interest, the relation between higher self-surveillance and poorer self-esteem was fully mediated by body shame and appearance anxiety, supporting Hypothesis 5, and consistent with Frederickson and Roberts (1997).

Interestingly, the magnitude of the link between appearance anxiety and self-esteem was comparable to the link between body shame and self-esteem. This could suggest that appearance anxiety and body shame might be equally useful predictors of other outcomes linked with self-objectification. Because researchers have tended to focus primarily on body shame as a mediator, however, it is unclear whether appearance anxiety similarly mediates negative mental health outcomes highlighted by objectification theory, such as depression and disordered eating. Studying the relative roles of these mediators simultaneously in future studies examining various mental health outcomes would enhance our understanding of the potential processes linking greater self-objectification with poorer mental health.

The (Non-Significant) Moderating Role of Gender

Contrary to previous research (e.g., Lowery et al. 2005; Strelan and Hargreaves 2005; Tiggemann and Kuring 2004), the predicted paths linking self-surveillance, body shame, appearance anxiety, and self-esteem were not stronger among women compared to men (Hypothesis 6). One potential explanation for the discrepancy with previous works is that we used a statistical approach (see also Grabe et al. 2007) to assess whether gender moderated the paths of the mediation model. In contrast, previous researchers have tended to rely on descriptive inspection only, or comparisons based solely on the p-values associated with individual associations. The primary disadvantage of both of these latter approaches is that associations among variables could appear to differ between genders, even if such differences are not statistically significant. Addressing these considerations, a statistical moderation approach provides greater confidence in the reliability of the findings when differential associations are hypothesised between genders. Thus, we encourage researchers to test moderating effects of gender in relations involving self-objectification using well-established and methodologically sound statistical approaches (e.g., Aiken and West 1991; and as illustrated in the present work).

The conceptual relevance of our findings concerning the non-significant moderating role of gender also bears consideration. The increase of objectification of men, in the media at least (e.g., Leit et al. 2001; Morrison et al. 2004; Pope et al. 2001), in combination with the lack of evidence for moderation by gender in our research, provides some evidence that objectification theory might be, in part, applicable to men (see also Morrison et al. 2003; Strelan and Hargreaves 2005). In the absence of a comprehensive theory for understanding men’s objectification experiences, future research testing objectification theory might include large samples (with equal numbers) of men and women so that statistical comparisons can be made across genders; also, the potential relevance of the tenets of objectification theory for men’s experiences could be evaluated. Greater specification of which self-objectification-related processes and relations are particularly relevant to either (or both) genders would be valuable to delimiting the boundaries of objectification theory with respect to describing the shared versus unique experiences of women and men.

Even though the pattern of relations among the factors examined in the present work was similar for men and women, the degree of self-objectification and associated experiences was more severe among women than men. Thus, our results provide additional evidence that self-objectification and related negative experiences are more severe among women than men (Hypothesis 1). Given these robust patterns of mean-level gender differences, researchers might devote additional attention to factors that heighten self-objectification among women versus men. Indeed, even though it is evident that women are more prone to, and more affected by, self-objectification, relatively little is known concerning what can be done to minimize the tendency to self-objectify. Dispositional and socio-cultural variables such as the media and male gaze (Calogero 2004) may differentially relate to self-objectification in men and women. Investigations of this nature could provide valuable insights concerning potential avenues for reducing self-objectification.

Stereotypical Gender Roles as Moderators

Contrary to our prediction (Hypothesis 7), femininity did not moderate the relation between self-surveillance and self-esteem, or between self-surveillance and the mediating variables body shame and appearance anxiety. Stereotypical femininity can be defined by traits such as awareness of other’s feelings and devoting the self to others (Spence et al. 1973). It is possible, therefore, that femininity might be more likely to moderate associations between self-objectification and factors such as internal awareness (Frederickson and Roberts 1997) and variables dealing with the needs or wants of others, rather than how one perceives one’s body (e.g., body shame, appearance anxiety).

Masculinity, in contrast, moderated the relations between self-surveillance and the mediating variables: Among those higher in masculinity, the relations between self-surveillance and body shame, and self-surveillance and appearance anxiety, were positive, but weaker, as predicted (Hypothesis 8). Why might masculinity attenuate shame about one’s body and anxiety about one’s appearance? Stereotypical masculinity is characterized by qualities such as independence and self-confidence (Spence et al. 1973), as well as a stronger sense of personal agency. Accordingly, individuals who are highly self-confident might be less likely to experience shame and anxiety about the self, or more likely to feel physically self-assured. Agency is also characterized by an ability to cope well under pressure; thus, individuals high in masculinity might be better equipped to resist socialization pressures linked with self-objectification, body shame, and appearance anxiety.

Contrary to hypotheses, neither gender role moderated the predictive effects of self-surveillance, body shame, and appearance anxiety on self-esteem. Furthermore, gender did not interact with gender roles, contrary to Hypothesis 9. One possibility, therefore, is that stereotypical gender roles might be relevant to only some parts of the network of relations involving self-objectification, in particular, with respect to links involving body-related factors (e.g., appearance anxiety, body-esteem), rather than more global indicators of functioning, such as self-esteem. Future research is needed to explore each of these possibilities.

Unexpectedly, among women (but not men), those who strongly endorsed feminine gender roles reported experiencing less body shame. We speculate that compared to women who weakly endorse feminine gender roles, women who strongly subscribe to cultural expectations governing women might adhere to these guidelines and work towards the ideal. As such, it is possible that they also perceive themselves as being closer to the ideal—not necessarily in body shape and size, but in dress and use of cosmetics, for example. If so, femininity might have a protective effect, at least, in relation to experiencing shame about one’s body. Future research might explore whether this relation is specific to body shame when measured with items covering stereotypically unfeminine, yet positive, attributes, such as physical strength, rather than items restricted to weight, as with the OBCS (McKinley and Hyde 1996) used in the present research.

Limitations

Several limitations of the present research should be noted. First, although we focused on self-objectification as an individual difference, an induced state of self-objectification also promotes body shame and negative outcomes (e.g., Frederickson et al. 1998; Martins et al. 2007). Future research is needed to explore the effects of state self-objectification on self-esteem, and assess potential gender differences (e.g., Hebl et al. 2004).

Second, because our design was correlational, we cannot assess causation. Longitudinal works and experimental designs are necessary for determining whether self-objectification causes body shame and appearance anxiety, and whether the body shame and appearance anxiety resulting from self-objectification cause poorer self-esteem. Whereas there is evidence that self- surveillance predicts negative outcomes over time (e.g., McKinley 2006), the mediating roles of body shame and appearance anxiety, and the possible moderating effects of gender and gender roles, have yet to be tested.

Third, we measured self-surveillance, a manifestation of self-objectification. Frederickson and Roberts (1997) original conceptualization specified a temporal ordering in which self-objectification leads to habitual body monitoring or self-surveillance. Body monitoring, therefore, is likely to be closer (conceptually and psychologically) to the hypothesized mediating and outcome factors. Consistent with this notion, Calogero (2009) modeled self-objectification as predicting body surveillance, which in turn predicted body shame. Although the present findings are consistent with these patterns, we did not assess self-objectification and body surveillance in the same study. Examining both self-objectification and body monitoring in a multiple-wave longitudinal study to test the implied temporal ordering would provide a more comprehensive test of objectification theory.

Fourth, objectification theory (Frederickson and Roberts 1997) proposes four potential mediating factors between self-objectification and mental health: body shame, appearance anxiety, flow, and internal awareness. In the present research, we extended previous works by exploring appearance anxiety in addition to body shame. However, our understanding of the effects of self-objectification in the context of objectification theory would benefit from designs that include all four mediators.

Summary and Conclusion

In summary, in the present study examining self-objectification among women and men, greater self-surveillance predicted lower self-esteem and this link was fully mediated by body shame and appearance anxiety. Further, although self-objectification and associated experiences were more severe among women than men, the mediation model linking self-surveillance and self-esteem via body shame and appearance anxiety did not differ across genders. Some evidence was found, however, for the moderating role of stereotypical gender roles—particularly masculinity as a buffer between self-surveillance and both body shame and appearance anxiety. These findings highlight the potential for objectification theory to inform the processes linking self-objectification and global self-worth, as well as the potential similarities and differences in the socialization experiences of women and men.

References

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park: Sage Publications.

Bakan, D. (1966). The duality of human existence: Isolation and communion in Western man. Boston: Beacon.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182.

Bartky, S. L. (1990). Femininity and domination: Studies in the phenomenology of oppression. New York: Routledge.

Baumeister, R. F., Campbell, J. D., Krueger, J. I., & Vohs, K. D. (2003). Does high self-esteem cause better performance, interpersonal success, happiness, or healthier lifestyles? Psychological Sciences in the Public Interest, 4, 1–44. doi:10.1111/1529-1006.01431.

Calogero, R. M. (2004). A test of objectification theory: The effect of the male gaze on appearance concerns in college women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 28, 16–21. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.2004.00118.x.

Calogero, R. M. (2009). Objectification processes and disordered eating in British women and men. Journal of Health Psychology, 14, 394–402. doi:10.1177/135910530912192.

Calogero, R. M., & Thompson, J. K. (2009). Sexual self-esteem in American and British college women: Relations with self-objectification and eating problems. Sex Roles, 60, 160–173. doi:10.1007/s11199-008-9517-0.

Calogero, R. M., Davis, W. N., & Thompson, J. K. (2005). The role of self-objectification in the experience of women with eating disorders. Sex Roles, 52, 43–50. doi:10.1007/s11199-005-1192-9.

Choma, B. L., Foster, M. D., & Radford, E. (2007). Use of objectification theory to examine the effects of a media literacy intervention on women. Sex Roles, 56, 581–591. doi:10.1007/s11199-007-9200-x.

Choma, B. L., Shove, C., Busseri, M. A., Sadava, S. W., & Hosker, A. (2009). Assessing the role of body image coping strategies as mediators or moderators of the links between self-objectification, body shame, and well-being. Sex Roles, 61, 699–713. doi:10.1007/s11199-009-9666-9.

Cooley, C. H. (1990). Human nature and the social order. Excerpted in A. G. Halberstadt & S. L. Ellyson (Eds.), Social psychology readings: A century of research (pp. 61–67). New York: McGraw-Hill (Original work published 1902).

Dion, K. L., Dion, K. K., & Keelan, J. P. (1990). Appearance anxiety as a dimension of social-evaluative anxiety: Exploring the ugly duckling syndrome. Contemporary Social Psychology, 14, 220–224.

Frederickson, B. L., & Roberts, T.-A. (1997). Objectification theory: Toward understanding women’s lived experiences and mental health risks. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21, 173–206.

Frederickson, B. L., Noll, S. M., Roberts, T.-A., Quinn, D. M., & Twenge, J. M. (1998). That swimsuit becomes you: Sex differences in self-objectification, restrained eating, and math performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75, 269–284.

Friestad, C., & Rise, J. (2004). A longitudinal study of the relationship between body image, self-esteem and dieting among 15–21 year olds in Norway. European Eating Disorders Review, 12, 247–255. doi:10.1002/erv.570.

Ganem, P. A., de Heer, H., & Morera, O. F. (2009). Does body dissatisfaction predict mental health outcomes in a sample of predominantly Hispanic college students? Personality and Individual Differences, 46, 557–561. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2008.12.014.

Garner, D. M. (1997). The 1997 body image survey results. Psychology Today, 30, 30–44.

Ghaed, S. G., & Gallo, L. C. (2006). Distinctions among agency, communion, and unmitigated agency and communion according to the interpersonal circumplex, five-factor model, and social-emotional correlates. Journal of Personality Assessment, 86, 77–88. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa8601_09.

Grabe, S., Hyde, J. S., & Lindberg, S. M. (2007). Body objectification and depression in adolescents: The role of gender, shame, and rumination. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 31, 164–175. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.2007.00350.x.

Greenleaf, C. (2005). Self-Objectification among physically active women. Sex Roles, 52, 51–62. doi:10.1007/s11199-005-1193-8.

Greenleaf, C., & McGreer, R. (2006). Disordered eating attitudes and self-objectification among physically active and sedentary female college students. Journal of Psychology: Interdisciplinary and Applied, 140, 187–198. doi:10.3200/JRLP.140.3.187-198.

Hallsworth, L., Wade, T., & Tiggemann, M. (2005). Individual differences in male body-image: An examination of self-objectification in recreational body builders. British Journal of Health Psychology, 10, 453–465. doi:10.1348/135910705X26966.

Hebl, M. R., King, E. B., & Lin, J. (2004). The swimsuit becomes us all: Ethnicity, gender, and vulnerability to self-objectification. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30, 1322–1331. doi:10.1177/0146167204264052.

Helgeson, V. S., & Fritz, H. L. (1999). Unmitigated agency and unmitigated communion: Distinctions from agency and communion. Journal of Research in Personality, 33, 131–158. doi:10.1006/jrpe.1999.2241.

Impett, E. A., Schooler, D. S., & Tolman, D. L. (2006). To be seen and not heard: Femininity ideology and adolescent girls’ sexual health. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 35, 131–144. doi:10.1007/s10508-005-9016-0.

Keyes, C. L. M. (2005). Mental health and/or mental illness? Investigating axioms of the complete state model of health. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73, 539–548. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.73.3.539.

Keyes, C. L. M. (2007). Promoting and protecting mental health as flourishing: A complementary strategy for improving national mental health. The American Psychologist, 62, 96–108. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.62.2.95.

Kilbourne, J. (Producer). (2002). Killing Us Softly III: Advertising’s image of women [Motion picture]. Available from Media Education Foundation, Northampton, MA 01060.

Knauss, C., Paxton, S. J., & Alsaker, F. D. (2008). Body dissatisfaction in adolescent boys and girls: Objectified body consciousness, internalization of the media body ideal and perceived pressure from media. Sex Roles, 59, 633–643. doi:10.1007/s11199-008-9474-7.

Leit, R. A., Pope, H. G., & Gray, J. J. (2001). Cultural expectations of muscularity in men: The evolution of playgirl centerfolds. The International Journal of Eating Disorders, 29, 90–93. doi:10.1002/1098-108X(200101)29:1<90::AID-EAT15>3.0.CO;2-F.

Lindberg, S. M., Grabe, S., & Hyde, J. S. (2007). Gender, pubertal development, and peer sexual harassment predict objectified body consciousness in early adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 17, 723–742. doi:10.1111/j.1532-7795.2007.00544.x.

Lowery, S. E., Kurpius, S. E. R., Befort, C., Blanks, E. H., Sollenberger, S., Nicpon, M. F., et al. (2005). Body image, self-esteem, and health-related behaviours among male and female first year college students. Journal of College Student Development, 46, 612–623.

Martins, Y., Tiggemann, M., & Kirkbride, A. (2007). Those speedos become them: The role of self-objectification in gay and heterosexual men’s body image. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 33, 634–647. doi:10.1177/0146167206297403.

McCreary Centre Society. (1999). Adolescent health survey II: Province of British Columbia. Vancouver: McCreary Centre Society.

McCreary, D. R., & Sasse, D. K. (2000). An exploration of the drive for muscularity in adolescent boys and girls. Journal of American College Health, 48, 297–304. doi:10.1080/07448480009596271.

McKinley, N. M. (1998). Gender differences in undergraduates’ body esteem: The mediating effect of objectified body consciousness and actual/ideal weight discrepancy. Sex Roles, 39, 113–123. doi:10.1023/A:1018834001203.

McKinley, N. M. (1999). Women and objectified body consciousness: Mothers’ and daughters’ body experience in cultural, developmental, and familial context. Developmental Psychology, 35, 760–769. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.35.3.760.

McKinley, N. M. (2006). The developmental and cultural contexts of objectified body consciousness: A longitudinal analysis of two cohorts of women. Developmental Psychology, 42, 679–687. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.42.4.679.

McKinley, N. M., & Hyde, J. S. (1996). The objectified body consciousness scale. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 20, 181–215. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.1996.tb00467.x.

Mercurio, A. E., & Landry, L. J. (2008). Self-objectification and well-being: The impact of self-objectification on women’s overall sense of self-worth and life satisfaction. Sex Roles, 58, 458–466. doi:10.1007/s11199-007-9357-3.

Moradi, B., & Huang, Y. (2008). Objectification theory and psychology of women: A decade of advances and future directions. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 32, 377–398. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.2008.00452.x.

Morrison, T. G., Kalin, R., & Morrison, M. A. (2004). Body-image evaluation and body-image investment among adolescents: A test of sociocultural and social comparison theories. Adolescence, 39, 571–592.

Morrison, T. G., Morrison, M. A., & Hopkins, C. (2003). Striving for bodily perfection? An exploration of the drive for muscularity in Canadian men. Psychology of Men and Muscularity, 4, 111–120. doi:10.1037/1524-9220.4.2.111.

Muehlenkamp, J. J., Swanson, J. D., & Brausch, A. M. (2005). Self-objectification, risk taking, and self-harm in college women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 29, 24–32. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.2005.00164.x.

Noll, S. M., & Frederickson, B. L. (1998). A mediational model linking self-objectification, body shame, and disordered eating. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 22, 623–636. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.1998.tb00181.x.

Olivardia, R., Pope, H. G., Jr., Borowiecki, J. J., III, & Cohane, G. H. (2004). Biceps and body image: The relationship between muscularity and self-esteem, depression, and eating disorder. Psychology of Men and Muscularity, 5, 112–120. doi:10.1037/1524-9220.5.2.112.

Pope, H. G., Olivardia, R., Borowiecki, J. J., & Cohane, G. H. (2001). The growing commercial value of the male body: A longitudinal survey of advertising in women’s magazines. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 70, 182–192. doi:10.1159/000056252.

Pozzebon, J. A., Visser, B. A., & Bogaert, A. F. (2009). What makes you think you’re so sexy, tall, and thin? The prediction of self-rated attractiveness, height, and weight. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Prichard, I., & Tiggemann, M. (2005). Objectification in fitness centers: Self-objectification, body dissatisfaction, and disordered eating in aerobic instructors and aerobic participants. Sex Roles, 53, 19–28. doi:10.1007/s11199-005-4270-0.

Robins, R. W., Hendin, H. M., & Trzesniewski, K. H. (2001). Measuring global self-esteem: Construct validation of a single-item measure and the Rosenberg self-esteem scale. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27, 151–161. doi:10.1177/0146167201272002.

Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Sanchez, D. T., & Kiefer, A. K. (2007). Body concerns in an out of the bedroom: Implications for sexual pleasures and problems. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 36, 808–820. doi:10.1007/s10508-007-9250-0.

Sinclair, S. L., & Myers, J. E. (2004). The relationship between objectified body consciousness and wellness in a group of college women. Journal of College Counseling, 7, 150–161.

Slater, A., & Tiggemann, M. (2002). A test of objectification theory in adolescent girls. Sex Roles, 46, 343–349. doi:10.1023/A:1020232714705.

Smolak, L., & Murnen, S. K. (2008). Drive for leanness: Assessment and relationship to gender, gender role and objectification. Body Image, 5, 251–260. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2008.03.004.

Spence, J. T., Helmreich, R. L., & Stapp, J. (1973). The personal attributes questionnaire: A measure of sex role stereotypes and masculinity-femininity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 32, 29–39.

Spence, J. T., Helmreich, R., & Stapp, J. (1975). Ratings of self and peers on sex role attributes and their relation to self-esteem and conceptions of masculinity and femininity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 32, 29–39. doi:10.1037/h0076857.

Stankiewicz, J. M., & Rosselli, F. (2008). Women as sex objects and victims in print advertisements. Sex Roles, 58, 579–589. doi:10.1007/s11199-007-9359-1.

Steer, A., & Tiggemann, M. (2008). The role of self-objectification in women’s sexual functioning. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 27, 205–225. doi:10.1521/jscp.2008.27.3.205.

Strelan, P., & Hargreaves, D. (2005). Reasons for exercise and body esteem: Men’s responses to self-objectification. Sex Roles, 53, 495–503. doi:10.1007/s11199-005-7137-5.

Strelan, P., Mehaffey, S. J., & Tiggemann, M. (2003). Self-objectification and esteem in young women: The mediating role of reasons for exercise. Sex Roles, 48, 89–95. doi:10.1023/A:1022300930307.

Szymanski, D. M., & Henning, S. L. (2007). The role of self-objectification in women’s depression: A test of objectification theory. Sex Roles, 56, 45–53. doi:10.1007/s11199-006-9147-3.

Tiggemann, M. (2005). Body dissatisfaction and adolescent self-esteem: Prospective findings. Body Image, 2, 129–135. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2005.03.006.

Tiggemann, M., & Kuring, J. K. (2004). The role of body objectification in disordered eating and depressed mood. The British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 43, 299–311. doi:10.1348/0144665031752925.

Visser, B. A., Pozzebon, J. A., Bogaert, A. F., & Ashton, M. C. (2010). Psychopathy, sexual behavior, and esteem: It’s different for girls. Personality and Individual Differences, 48, 833–838. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2010.02.008.

Wolf, N. (1991). The beauty myth. New York: William Morrow.

World Health Organization, Global Database on Body Mass Index (2010). Global Database on Body Mass Index. Retrieved from http://apps.who.int/bmi/index.jsp?introPage=intro_3.html.

Acknowledgement

The present study was part of a larger investigation supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council and a Brock University Chancellor’s Chair for Research Excellence award to Anthony F. Bogaert.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Choma, B.L., Visser, B.A., Pozzebon, J.A. et al. Self-Objectification, Self-Esteem, and Gender: Testing a Moderated Mediation Model. Sex Roles 63, 645–656 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-010-9829-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-010-9829-8