Abstract

This study examined the relationship between internalized misogyny and two other forms of internalized sexism, self-objectification and passive acceptance of traditional gender roles. In addition, it examined the moderating role of internalized misogyny in the link between sexist events and psychological distress. Participants consisted of 274 heterosexual women who were recruited at a large southern university in the United States and completed an online survey. Results indicated that internalized misogyny was related to, but conceptually distinct from self-objectification and passive acceptance. Findings also indicated that greater experiences of sexist events were associated with higher levels of psychological distress. In addition, internalized misogyny intensified the relationship between external sexism and psychological distress.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

According to Feminist Therapy Theory, the personal is political, that is, women’s personal problems both in the United States and abroad are influenced by the socio-cultural and political conditions in which they live and can be conceptualized as reactions to oppression (Brown 1994; Enns 2004). Because women both in the United States and abroad often live in patriarchal cultures, many women are exposed to various forms of sexism that come from a variety of places including the media, religious institutions, political and legal systems, places of work, and familial and interpersonal relationships (American Psychological Association 2007). The personal is political posits that sexism is likely to contribute to women’s mental health problems directly through experiences of sexist events and through the internalization of negative and limiting messages about being a woman. In addition, Feminist Therapy Theory postulates that internalized sexism may exacerbate or moderate the effects of sexist events on psychological distress (Brown 1994; Enns 2004; Worell and Remer 2003). Research on potential moderators of the link between sexist events and psychosocial health might identify subgroups of women for whom this link may be more pronounced, which could ultimately inform interventions targeted to these women.

Sexist Events and Psychological Distress

Sexist events have been conceptualized as gender specific, negative life events that are unique to women, socially based (e.g., they stem from relatively stable underlying patriarchal social structures, institutions, and processes beyond the individual), chronic, and cause excess stress (Klonoff and Landrine 1995; Swim et al. 1998). Two measures with good psychometric support have been developed to assess sexist events. The first, the Schedule of Sexist Events (Klonoff and Landrine 1995), assesses sexism in the forms of sexist degradation and its consequences and sexist discrimination in both close and distant relationships and in the workplace. The second, the Daily Sexist Events Scale (Swim et al. 1998; Swim et al. 2001), assesses sexism in the forms of traditional gender role stereotyping and prejudice, demeaning and derogatory comments and behaviors, and unwanted sexually objectifying comments and behaviors.

Recent research, using either the Schedule of Sexist Events (Klonoff and Landrine 1995) or the Daily Sexist Events Scale (Swim et al. 1998; Swim et al. 2001), has built support for a consistent connection between experiences of external sexism and psychological symptoms among women in general and various subgroups of women. For example, previous research has found that more experiences of sexist events are related to greater psychological distress among college women (Fischer and Holz 2007; Moradi and Subich 2002, 2004; Klonoff et al. 2000; Sabik and Tylka 2006; Swim et al. 2001; Zucker and Landry 2007), both a college and community female sample (Landrine et al. 1995), lesbian and bisexual women (Szymanski 2005; Szymanski and Owens 2009), African American females (Moradi and Subich 2003), and women who sought counseling (Moradi and Funderburk 2006). In addition, Landrine et al. found that sexist events are related to psychological distress above and beyond major and minor generic stressful life events, and Klonoff et al. (2000) found that sexist events may account for gender differences in anxious, depressive, and somatic symptoms. Moreover, this relationship between sexist events and poorer mental health holds when sexism is operationalized in other ways including experiences of childhood sexual abuse (Polusny and Follette 1995), sexual assault, rape, and domestic violence (Koss et al. 2003; Wolfe and Kimerling 1997), and workplace harassment and discrimination (Fitzgerald et al. 1997; Pavalko et al. 2003). Thus, these findings are consistent with the feminist therapy tenet of attending to sexist and oppressive power dynamics in the current contexts of women’s lives (Brown 1994; Worell and Remer 2003).

Internalized Sexism and Psychological Distress

Similar to research on external sexism, a burgeoning body of research has begun to demonstrate the negative relationship between various manifestations of internalized sexism and women’s psychosocial health. One of the most popular manifestations of internalized sexism that has been researched is the construct of self-objectification (McKinley and Hyde 1996; Noll and Fredrickson 1998). Self-objectification refers to the internalization of sexually objectifying experiences that occurs when women treat themselves as an object to be looked at and evaluated on the basis of appearance (Fredrickson and Roberts 1997). Researchers have consistently found positive correlations between self-objectification and both depression (Miner-Rubino et al. 2002; Szymanski and Henning 2007; Tiggemann and Kuring 2004) and disordered eating (McKinley and Hyde 1996; Moradi et al. 2005; Muehlenkamp and Saris-Baglama 2002; Noll and Fredrickson 1998; Tiggemann and Kuring 2004; Tiggemann and Slater 2001). In addition, Moradi et al. (2005) found that self-objectification mediated the relationships between sexually objectifying experiences and disordered eating. This finding provides evidence for the importance of looking at the influence of third variables in the link between external sexism and psychosocial distress.

Another conceptualization of internalized sexism that has garnered empirical support is passive acceptance of traditional gender roles and unawareness or denial of cultural, institutional, and individual sexism (Bargad and Hyde 1991; Downing and Roush 1985; Fischer et al. 2000; Worell and Remer 2003). Passive acceptance has been found to be positively correlated with foreclosed identity (Fischer et al. 2000) and psychological distress (Moradi and Subich 2002) among presumably heterosexual women. However, contrary to these findings, no support was found for a relationship between passive acceptance and psychological distress among lesbians and bisexual women (Szymanski 2005). In addition, mixed findings have been found concerning symptoms of disordered eating with one study finding a positive relationship between passive acceptance and symptoms of disordered eating (Snyder and Hasbrouck 1996) and another finding no relationship between the two variables (Sabik and Tylka 2006).

Consistent with Feminist Therapy Theory, Moradi and Subich (2002) found that passive acceptance moderated the relationship between sexist events and psychological distress. That is, this form of internalized sexism exacerbated the relationship between experiences of sexist events within the past year and women’s psychological distress. Contrary to this finding, Sabik and Tylka (2006) found no support for the moderating role of passive acceptance in the link between sexist events and symptoms of disordered eating. These findings suggest that manifestations of internalized sexism might moderate the sexism-psychological distress link but not the sexism-disordered eating link. Taken together, these studies provide evidence for examining the internalized sexism-distress link among subgroups of women and for the importance of examining moderators in the link between sexism and mental health.

Although self-objectification and passive acceptance appear to be important manifestations of the ways in which sexism can be internalized, they fail to attend to a core construct of sexism which is misogyny or a hatred and devaluation of women (Szymanski and Kashubeck-West 2008). Misogyny is a cultural practice that serves to maintain power of the dominant male group through the subordination of women (Piggot 2004). Women, and their role in society, are thus devalued to increase and maintain the power of men, which results in a fear of femininity and a hatred and devaluing of women and female related characteristics (Burch 1987; O’Neil 1981; Worell and Remer 2003). The negative impact of the devaluation of something as central as gender is perpetuated not only by men but also by women who reinforce the central male culture of devaluing women through acts of horizontal oppression and omission resulting from internalized misogyny (Piggot 2004; Saakvitne and Pearlman 1993).

The only known measure assessing internalized misogyny is the Internalised Misogyny Scale (IMS; Piggot 2004). The IMS consists of 17 items which reflect three dimensions: devaluing of women, distrust of women, and gender bias in favor of men. Validity was supported by feedback from a focus group, exploratory factor analysis, cross-cultural comparisons, and correlating the IMS with measures of modern sexism, internalized heterosexism, body image, depression, self-esteem, psychosexual adjustment, and social desirability in a cross cultural sample of 803 women from Australia, the United States, Canada, Finland, and the United Kingdom. In addition, internalized misogyny assessed via the IMS has been found to related to lower self esteem, less social support, and more psychological distress among sexual minority women living in the United States (Szymanski and Kashubeck-West 2008), and to negative body image, depression, low self-esteem, and less psychosexual adjustment among lesbian and bisexual women living in five different countries; i.e., Australia, Canada, England, Finland, and the United States (Piggot 2004). However, no study has examined if the relationship between internalized misogyny and poorer psychosocial health holds true for heterosexual women.

Taken together, the results of these studies suggest that internalized sexism can manifest in very different ways. However, it is unclear how internalized misogyny is related to these other forms of internalized sexism (i.e., are they essentially measuring the same thing, are they related but conceptually distinct from one another, or are they unrelated to each other). Feminist Theory would suggest that internalized sexism can manifest in many different ways and that internalized misogyny would be related to, but conceptually distinct from self-objectification and passive acceptance. In addition, research largely supports feminist contentions that there is a direct relationship between internalized oppression and women’s mental health. However, given the more recent development and measurement of the internalized misogyny construct more research is needed to examine the relationship between internalized misogyny and the psychosocial health of heterosexual women and women from other minority groups. Furthermore, scant research has examined the potential moderating role of various manifestations of internalized sexism in the link between sexist events and women’s psychological distress.

Internalized Misogyny as a Potential Moderator of the Sexist Events-Distress Link

Moderators address the question of under what circumstances does a variable most strongly predict an outcome variable (Frazier et al. 2004). Thus, moderators are variables which could potentially intensify or buffer the relationship between sexism and mental health. Feminist Theory postulates an augmenting or synergistic effect of various aspects of internalized sexism in the relationship between sexist events and mental health (Brown 1994; Enns 2004; Worell and Remer 2003). That is, as the level of internalized misogyny (i.e., the moderator) increases, the relationship between sexist events and psychological distress becomes stronger. Internalized sexism represents a form of self-blame and thus may intensify the relationship of sexist events and mental health. That is, an experience of sexist discrimination is more painful when the victim agrees with the sexist attitudes conveyed by the victimization event. Furthermore, oppressive experiences many be more harmful to women who have negative evaluations of women in general and of oneself as a woman than those who hold positive evaluations (Moradi and Subich 2002, 2004).

Summary of the Current Study

In sum, the purpose of this study is to examine: (a) the relationship between internalized misogyny and self-objectification and passive acceptance to determine if these constructs are related but conceptually distinct forms of internalized sexism, (b) the independent and concurrent relationships of sexist events and internalized misogyny to psychological distress, and (c) the potential moderating role of internalized misogyny in the external sexism-distress link in a sample of undergraduate heterosexual women living in the United States. More specifically, the following hypotheses will be examined:

-

Hypothesis 1:

Internalized misogyny will be significantly correlated with self-objectification and passive acceptance.

-

Hypothesis 2:

Sexist events and internalized misogyny will be significantly correlated with psychological distress.

-

Hypothesis 3:

When examined concurrently, both sexist events and internalized misogyny will be significantly related to psychological distress.

-

Hypothesis 4:

Internalized misogyny will moderate the relationship between sexist events and psychological distress.

Hierarchical multiple regression will be used to examine whether internalized misogyny moderates the relationship between sexist events and psychological distress because it is recognized as the best method to detect the presence or absence of moderating effects (Aiken and West 1991; Frazier et al. 2004). In this analysis, the predictor (i.e., sexist events) and proposed moderator variable (i.e. internalized misogyny) are entered at Step 1. Next, at Step 2, the interaction term (i.e., sexist events X internalized misogyny) is entered. Evidence for a moderator effect is noted at Step 2 by a statistically significant increment in R² and beta weight.

Method

Participants

Participants consisted of 274 self-identified heterosexual women who were recruited via undergraduate psychology courses at a large southern university in the United States. Two participants who identified as lesbian and one participant who identified as not sure about her sexual orientation were dropped from the sample and not included in any of the analyses. Participants ranged in age from 18 to 31 years, with a mean age of 18.88 years (SD = 1.44). The sample was 68% (n = 187) 1st year undergraduates, 21% (n = 58) Sophomore, 7% (n = 20) Junior, and 3% (n = 9) Senior. The sample was 11% (n = 29) African American/Black, 1% (n = 4) Asian American/Pacific Islander, 84% (n = 230) European American/White, 2% (n = 5) Hispanic/Latina, 1% (n = 2) Native American, 1% (n = 2) multiracial, and 1% (n = 2) other. Twenty four percent (n = 65) were single and not dating, 46% (n = 126) were single and dating, and 30% (n = 83) were married, partnered, or in a committed relationship. Due to rounding percentages may not add up to 100%.

Measure

Sexist events were assessed via the Daily Sexist Events Scale (Swim et al. 1998; Swim et al. 2001), which consists of 26 items assessing sexism in the forms of traditional gender role stereotyping and prejudice and unwanted sexually objectifying comments and behaviors. We chose to use the Daily Sexist Events Scale in our study because it was developed using a series of daily diary studies to examine the incidence and nature of sexist events specifically experienced by college students. Participants are asked to indicate how often during the previous semester they experienced a variety of sexist events. Example items include “Had people shout sexist comments, whistle, or make catcalls at me” and “Heard someone express disapproval of me because I exhibited behavior inconsistent with stereotypes about my gender.” Each item is rated using a 5-point Likert scale with the following response options: 1 (never), 2 (about once during the last semester), 3 (about once a month during the last semester), 4 (about once a week during the last semester), and 5 (about two or more times a week during the last semester). Mean scores were used with higher scores indicating the experience of more sexist events. Content and construct validity was supported via a series of daily dairy studies of sexist experiences, exploratory factor analyses, findings indicating that women reported more sexist events than men, correlations demonstrating that more experiences of sexist events was related to more anger, greater depression, decreased comfort, and less self-esteem among women, and that sexist events was not related to neuroticism (Swim et al. 1998; Swim et al. 2001). Alpha for scores in the current sample was .95.

Internalized misogyny was assessed using the Internalised Misogyny Scale (IMS; Piggot 2004), which consists of 17 items reflecting three factors: distrust of women, devaluing of women, and valuing men over women. We chose the IMS measure to assess internalized misogyny because it is the only known measure assessing this form of internalized sexism, has good psychometric support, and was developed using an international sample so it may have more utility in use with both United States and non-United States samples. Example items include “Sometimes other women bother me by just being around,” “It is generally safer not to trust women too much,” and “Generally, I prefer to work with men.” Each item is rated on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Mean scores were used with higher scores indicating more internalized misogyny. Reported alpha for scores on the IMS were .88 full scale, .82 Distrust of Women Subscale, .83 Devaluing Women subscale, and .74 Valuing Men subscale. Validity was supported by feedback from a focus group, exploratory factor analysis, cross-cultural comparisons, and correlating the IMS with measures of modern sexism, internalized heterosexism, body image, depression, self-esteem, psychosexual adjustment, and social desirability in a cross cultural sample of 803 sexual minority women (Piggot 2004). Alpha for full scale scores in the current sample was .90.

Self-objectification was assessed using the Self-Objectification Questionnaire (Noll and Fredrickson 1998), which consists of ten items pertaining to physical attributes that reflect the physical self-concept of the respondent. Five items concern attributes that are appearance-based (i.e., physical attractiveness, sex appeal, weight, firm/sculpted muscles, and measurements), and five items concern attributes that are competence-based (i.e., health, energy level, physical coordination, physical fitness level, and strength). Each item is rank ordered by the respondent from most important (rank 1) to least important (rank 10). Scores were computed by summing the ranks for the appearance and competence attributes separately, then computing a difference score. Higher scores reflect a greater emphasis on appearance, thus greater self-objectification. Validity was supported by correlating the Self-Objectification Questionnaire with measures of body dissatisfaction, body shame, appearance anxiety, neuroticism, and negative affect (Noll & Fredrickson; Miner-Rubino et al. 2002).

Passive acceptance was assessed using the passive acceptance subscale of Bargad and Hyde’s (1991) Feminist Identity Development Scale (FIDS), which consists of ten items assessing passive acceptance of traditional gender roles and unawareness or denial of cultural, institutional, and individual sexism. Example of items include “I think that rape is sometimes the woman’s fault” and “I think that men and women had it better in the 1950s when married women were housewives and their husbands supported them.” Each statement is rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Mean scores were used with higher scores indicating more passive acceptance of traditional gender roles. Reported alpha for scores on the passive acceptance subscale was .85 (Bargad and Hyde 1991). Validity was supported via theoretically predicted significant score changes in pre-post comparisons of students enrolled in women’s studies courses (Bargad and Hyde 1991), and significant correlations between extent of exposure to women’s issues in graduate psychology programs and less passive acceptance (Worell et al. 1999). Alpha for scores in the current sample was .80.

Psychological distress was assessed using the Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL; Derogatis et al. 1974), which consists of 58 items reflecting psychological distress across five symptom dimensions: depression, somatization, interpersonal sensitivity, anxiety, and obsessive compulsive. We chose to use the HSCL in our study because several studies examining the relationships between external and internalized sexism and psychological distress have used the HSCL (e.g., Klonoff et al. 2000; Landrine et al. 1995; Szymanski 2005; Szymanski and Kashubeck-West 2008) or derivations of it (e.g., (Moradi and Funderburk 2006; Moradi and Subich 2002, 2003, 2004) in their studies. Examples of items include “Feeling easily annoyed or irritated” and “Feeling blue.” Participants indicate how often they have felt each symptom during the past several days using a 4-point Likert scale from 1 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). Mean scores were used with higher scores indicating more psychological distress. Reported alpha for scores on the HSCL ranged from .84 to .87. Test-retest reliability ranged from .75 to .84. Validity of the HSCL was supported by studies reflecting the factorial invariance of HSCL symptom dimensions, between group differences, and the HSCL’s sensitivity to the use of psychotherapeutic drugs.

Reviews of the literature suggest that all versions of the widely used Symptom Checklist, including the HSCL used in the current study as well as the commercially published Symptom Checklist-90-R (SCL-90-R) appear to measure a general distress factor (Cyr et al. 1985). Inter-correlations between HSCL subscales in the current study (r’s ranged from .67 to .83) support this assertion. In addition, a global distress measure was used in several studies (e.g., Corning 2002; Klonoff et al. 2000; Landrine et al. 1995; Moradi and Funderburk 2006; Moradi and Subich 2002, 2003, 2004; Szymanski 2005; Szymanski and Kashubeck-West 2008) examining the relationship between external and/or internalized sexism and mental health, so we chose to use the HSCL full scale scores so we could make better and cleaner comparisons to previous studies. Alpha for scores in the current sample was .97.

Procedures

Participants were recruited via undergraduate psychology courses through a psychology department’s research website at a large southern university. Potential participants used a hypertext link to access the survey website. After reading an informed consent, participants were instructed to complete the online survey, which included the aforementioned measures. As an incentive to participate, all participants were given course credit for their undergraduate psychology class and were eligible to enter a participant raffle awarding $100 each to five randomly selected participants.

Procedures for this website survey were based on published suggestions (Buchanan and Smith 1999; Michalak and Szabo 1998; Schmidt 1997). Methods for protecting confidentiality included having participants access the research survey via a hypertext link rather than e-mail to ensure participant anonymity and the use of a separate course credit database so there was no way to connect a person’s on-line raffle submission with her submitted survey. Methods used for ensuring data integrity included using “cookies” to identify problems associated with multiple submissions of data from the same computer, and use of a secure server protected with a firewall to prevent tampering with data and programs by “hackers” and inadvertent access to confidential information by research participants. Gosling et al. (2004) reported that results from Internet studies are consistent with findings obtained from traditional pen-and-paper methods.

Results

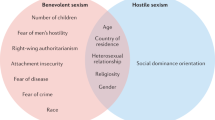

Possible range, means, standard deviations, and inter-correlations among all continuous variables assessed in this study are shown in Table 1. To test hypothesis 1, correlations between internalized misogyny and self-objectification and passive acceptance were conducted to determine if internalized misogyny was a related but conceptually distinct form of internalized sexism. Low to moderate correlations between internalized misogyny and self-objectification (r = .12; p < .05) and passive acceptance (r = .53; p < .05) supported this assertion.

To test hypothesis 2, correlations between sexist events and internalized misogyny and psychological distress were conducted. As expected sexist events (r = .44, p < .05; medium effect size) and internalized misogyny (r = .12, p < .05; small effect size) were significantly positively correlated with psychological distress. To test hypothesis 3, a simultaneous multiple regression was conducted to test the unique contributions of sexist events and internalized misogyny in predicting psychological distress. The results of this analysis were significant, R² = .197, F (2, 263) = 31.915, p < .001, and revealed that sexist events (β = .43; t = 7.696; p < .001) was a significant and unique predictor of psychological distress but internalized misogyny was not (β = .065; t = 1.161; p > .05).

To test hypothesis 4, a hierarchical multiple regression was conducted to test the moderator effects of internalized misogyny in sexism-distress link. Scores for sexist events and internalized misogyny were centered to reduce multicollinearity between the interaction terms and other predictor variables (Aiken and West 1991; Tabachnick and Fidell 2001). Multicollinearity is a problem that occurs when variables are redundant and too highly correlated which results in an inflation of the size of error terms and weakens an analysis (Tabachnick and Fidell 2001). Absolute value correlations below .90, condition indexes below 30, and variance inflation factors below ten indicate that multicollinearity is not a problem (Myers 1990; Tabachnick and Fidell 2001). Correlations between the predictor variables (r = .13), condition index values (range = 1.00 to 1.19), and variance inflation factors (range = 1.01 to 1.03) revealed that multicollinearity was not a problem for the current analysis. Main effects were entered at Step 1 and interaction effects at Step 2. A significant change in R² for the interaction term indicated a significant moderator effect (see Table 2). That is, the interaction between sexist events and internalized misogyny (β = .13) was a significant predictor of psychological distress scores and accounted for 1.6% beyond the variance accounted for by sexist events and internalized misogyny (R² Change = .016; F Change = 5.380; Significant F Change = .021).

To interpret the statistically significant interaction, regression lines were plotted using an equation which included terms for the two main effects (sexist events and internalized misogyny), and the interaction term (sexist events X internalized misogyny, along with the corresponding unstandardized regression coefficients and regression constant (Aiken and West 1991; Cohen and Cohen 1983). As recommended by Aiken and West (1991), psychological distress scores for sexist events scores of one standard deviation below and above the mean and low internalized misogyny (one standard deviations below the mean) versus high internalized misogyny (one standard deviations above the mean) were plotted on a graph. Aiken and West’s (1991) simple slope analysis showed that sexist events predicted psychological distress for women with low internalized misogyny, β = .327, t (260) = 4.606, p < .001, and for women with high internalized misogyny, β = .531, t (260) = 7.544, p < .001, indicating that sexist events predicts psychological distress for women with both low and high levels of internalized misogyny but this relationship is stronger for those with high internalized misogyny scores. As shown in Fig. 1, the difference between the two internalized misogyny groups occurs at the higher levels of sexism when women who have more internalized misogyny have more psychological distress.

Discussion

Consistent with Feminist Therapy Theory and previous research, the findings of this study suggest that sexist events are positively related to psychological distress in an undergraduate sample of heterosexual women. In addition, the medium effect size (r = .44) found in this study is consistent with previous research examining the sexism-distress link (c.f., Fischer and Holz 2007; Moradi and Subich 2002, 2003, 2004; Szymanski 2005; Szymanski and Owens 2009). Thus, feminist psychologists are encouraged to assist their female clients in recognizing the potentially negative impact of sexism on their lives, help them see their problems in a contextual light in order to reduce shame and victim blame, and teach them skills for dealing with and confronting oppression. In addition, it provides empirical support to validate feminist psychologists’ social justice efforts aimed at eradicating sexism.

The results of our study also support the need to focus on internalized misogyny or a devaluation and distrust of women as well as a belief in male superiority, as a manifestation of internalized sexism that is related to, but conceptually distinct from self-objectification and passive acceptance of traditional gender roles and an unawareness of sexism. The results of the current study indicated a small effect size (r = .12) for the relationship between internalized misogyny and psychological distress among a heterosexual female sample. Although consistent with Feminist Therapy Theory and the relations found among sexual minority women, the effect size found in the current study is smaller than that reported for sexual minority women (i.e., r = .24 for depression; Piggot 2004; and r = .26 for psychological distress; Szymanski & Kashubeck-West 2008). Furthermore, when sexist events and internalized misogyny were examined concurrently, only sexist events emerged as a unique predictor of psychological distress. In addition, the moderator analysis indicated that the interaction of sexism and internalized misogyny was also a unique predictor of psychological distress. This suggests that both main effects and the moderated effects of internalized misogyny in the link between external sexism and psychological distress may be important when working with heterosexual female clients.

The moderated effect of internalized misogyny in the sexism-distress links is consistent with studies demonstrating the moderating role of passive acceptance of traditional gender roles and an unawareness of sexism (Moradi and Subich 2002) and self-esteem in the relationship between external sexism and psychological distress (Corning 2002; Moradi and Subich 2004). The findings of our moderated model suggest that internalized misogyny exacerbates the relationship between sexist events and psychological distress among heterosexual women. Thus, practitioners working with clients with high experiences of sexist events might use therapeutic strategies aimed to decrease their client’s internalized misogyny as a way to possibly mute the potentially unfavorable influence of sexist events on their mental health.

This study is limited by sampling method (undergraduate students enrolled in a course at a Southern University in the United States), self-report measures, a correlational design, and a predominately young adult White sample. Respondents recruited from enrollment in undergraduate psychology courses may be biased in some way (e.g., being more homogeneous than the larger target population and having lower levels of internalized misogyny than the larger target population). As is true with all self-report data, participants may not have responded honestly to survey items and results could be due to method variance or a general tendency to respond negatively. In addition, individual differences are likely to exist in judgments about what constitutes a sexist event. Inferences about causality cannot be made due to the cross-sectional and correlational nature of this study. For example, sexist events might result in greater psychological distress, psychological distress might result in more frequent perceptions of sexist events, or a circular relationship might exist between sexist events and psychological distress.

Generalizability of this study is limited by the lack of age and racial/ethnic diversity in the sample. It is possible that the relationships between external and internalized sexism and psychological distress become weaker as women age and develop more cognitive, emotional, and/or social resources to buffer themselves from sexism (Szymanski and Henning 2007). It is also important to consider that the experience of both external and internalized sexism may be different for women of color because it is often fused with their experiences of external and internalized racism. Thus, future research examining the sexism-distress links, and potential moderators of these links, with older women, racial/ethnic minority women, and women outside the United States is warranted. Research on other potential moderators, such as resilience, hardiness, cognitive ability, social support, coping styles and strategies, and involvement in feminist activism, that might weaken or intensify the link between sexist events and psychosocial health is also needed. Longitudinal research is necessary to provide stronger evidence that sexist events have deleterious consequences for women. Finally, future research might identify the types of therapeutic experiences that reduce the strength of the relationship between sexist events and poor mental health.

In conclusion, the current study adds to the accumulating body of research demonstrating the potential negative impact that sexism can have on women’s lives. This study extends prior research by examining internalized misogyny as a third variable that might explain the relationship between sexism and women’s psychological distress. Results indicated that internalized misogyny is an important manifestation of internalized sexism that intensifies the relationship between external sexism and psychological distress.

References

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

American Psychological Association. (2007). Guidelines for Psychological Practice with Girls and Women. American Psychologist, 62, 949–979.

Bargad, A., & Hyde, J. S. (1991). Women’s studies: A study of feminist identity development in women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 15, 181–201.

Brown, L. S. (1994). Subversive dialogues. New York: Basic Books.

Buchanan, T., & Smith, J. L. (1999). Using the Internet for psychological research: Personality testing on the World Wide Web. British Journal of Psychology, 90, 125–144.

Burch, B. (1987). Barriers to intimacy: Conflicts over power, dependency, and nurturing in lesbian relationships. In Boston Lesbian Psychologies Collective (Ed.), Lesbian psychologies: Explorations and challenges, pp. 126–141. Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

Cohen, J., & Cohen, P. (1983). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Corning, A. F. (2002). Self-esteem as a moderator between perceived discrimination and psychological distress among women. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 49, 117–126.

Cyr, J. J., McKenna-Foley, J. M., & Peacock, E. (1985). Facture structure of the SCL-90-R: Is there one? Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 571–578.

Derogatis, L. R., Lipman, R. S., Rickets, K., Uhlenhuth, E. H., & Covi, L. (1974). The Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL): A self-report symptom inventory. Behavioral Science, 19, 1–14.

Downing, N., & Roush, K. (1985). From passive acceptance to active commitment: A model of feminist identity development for women. The Counseling Psychologist, 13, 695–709.

Enns, C. Z. (2004). Feminist theories and feminist psychotherapies: Origins, themes, and Diversity (2nd ed.). New York: Haworth.

Fischer, A. R., & Holz, K. B. (2007). Perceived discrimination and women’s psychological distress: The roles of collective and personal self-esteem. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 54, 154–164.

Fischer, A. R., Tokar, D. M., Mergl, M. M., Good, G. E., Hill, M. S., & Blum, S. A. (2000). Assessing women’s feminist identity development: Studies of convergent, discriminant, and structural validity. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 24, 15–29.

Fitzgerald, L. F., Drasgow, F., Hulin, C. L., Gefand, M. J., & Magley, V. J. (1997). Antecedents and consequences of sexual harassment in organizations: A test of an integrated model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82, 578–589.

Frazier, P. A., Tix, A. P., & Barron, K. E. (2004). Testing moderator and mediator effects in counseling psychology research. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 51, 115–134.

Fredrickson, B. L., & Roberts, T. (1997). Objectification theory: Toward understanding women’s lived experiences and mental health risks. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21, 173–206.

Gosling, S. D., Vazire, S., Srivastava, S., & John, O. P. (2004). Should we trust web-based studies: A comparative analysis of six preconceptions about Internet questionnaires. American Psychologist, 59, 93–104.

Klonoff, E. A., & Landrine, H. (1995). The Schedule of Sexist Events: A measure of lifetime and recent sexist discrimination in women’s lives. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 19, 439–472.

Klonoff, E. A., Landrine, H., & Campbell, R. (2000). Sexist discrimination may account for well-known gender differences in psychiatric symptoms. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 24, 93–99.

Koss, M. P., Bailey, J. A., Yan, N. P., Herrera, V. M., & Lichter, E. L. (2003). Depression and PTSD in survivors of male violence: Research and training initiatives to facilitate recovery. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 27, 130–142.

Landrine, H., Klonoff, E. A., Gibbs, J., Masnning, V., & Lund, M. (1995). Physical and psychiatric correlates of gender discrimination: An application of the Schedule of Sexist Events. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 19, 473–492.

McKinley, N. M., & Hyde, J. S. (1996). The Objectified Body Consciousness Scale: Development and validation. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 20, 181–215.

Michalak, E. E., & Szabo, A. (1998). Guidelines for internet research: An update. European Psychologist, 3(1), 70–75.

Miner-Rubino, K., Twenge, J. M., & Fredrickson, B. L. (2002). Trait self-objectification in women: Affective and personality correlates. Journal of Research in Personality, 36, 147–172.

Moradi, B., & Funderburk, J. R. (2006). Roles of perceived sexist events and perceived social support in the mental health of women seeking counseling. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53, 464–473.

Moradi, B., & Subich, L. M. (2002). Perceived sexist events and feminist identity development attitudes: Links to women’s psychological distress. The Counseling Psychologist, 30, 44–65.

Moradi, B., & Subich, L. M. (2003). A concomitant examination of the relations of perceived racist and sexist events to psychological distress for African American women. The Counseling Psychologist, 31(4), 451–469.

Moradi, B., & Subich, L. M. (2004). Examining the moderating role of self-esteem in the link between experiences of perceived sexist events and psychological distress. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 51, 50–56.

Moradi, B., Dirks, D., & Matteson, A. V. (2005). Roles of sexual objectification experiences and internalization of standards of beauty in eating disorder symptomatology: A test and extension of Objectification Theory. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 52, 420–428.

Muehlenkamp, J. J., & Saris-Baglama, R. N. (2002). Self-objectification and its psychological outcomes for college women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 26, 371–379.

Myers, R. (1990). Classical and modern regression with application (2nd ed.). Boston: Duxbury.

Noll, S. M., & Fredrickson, B. L. (1998). A mediational model linking self-objectification, body shame, and disordered eating. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 22, 623–636.

O’Neil, J. (1981). Patterns of gender role conflict and strain: Sexism and fear of femininity in men’s lives. The Personnel and Guidance Journal, 60, 203–210.

Pavalko, E. K., Mossakowski, K. N., & Hamilton, V. J. (2003). Does perceived discrimination affect health? Longitudinal relationships between workplace discrimination and women’s physical and emotional health. Journal of Health and social Behavior, 43, 18–33.

Piggot, M. (2004). Double jeopardy: Lesbians and the legacy of multiple stigmatized identities. Psychology Strand at Swinburne University of Technology, Australia: Unpublished thesis.

Polusny, M. A., & Follette, V. M. (1995). Long-term correlates of child sexual abuse: Theory and review of the empirical literature. Applied and Preventive Psychology, 4, 143–166.

Saakvitne, K. W., & Pearlman, L. A. (1993). The impact of internalized misogyny and violence against women on feminine identity. In E. P. Cook (Ed.), Women, relationships, and power: Implications for counseling. Alexandria. VA: American Counseling Association.

Sabik, N. J., & Tylka, T. L. (2006). Do feminist identity styles moderate the relation between perceived sexist events and disordered eating? Psychology of Women Quarterly, 30, 77–84.

Schmidt, W. C. (1997). World-Wide Web survey research: Benefits, potential problems, and solutions. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments & Computers, 2, 274–279.

Snyder, R., & Hasbrouck, L. (1996). Feminist identity, gender traits, and symptoms of disturbed eating among college women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 20, 593–598.

Swim, J. K., Cohen, L. L., & Hyers, L. L. (1998). Experiencing everyday prejudice and discrimination. In J. K. Swim & C. Stangor (Eds.), Prejudice: The target's perspective (pp. 37–60) San Diego. CA: Academic Press.

Swim, J. K., Hyers, L. L., Cohen, L. L., & Ferguson, M. J. (2001). Everyday sexism: Evidence for its incidence, nature, and psychological impact from three daily diary studies. Journal of Social Issues, 57, 31–53.

Szymanski, D. M. (2005). Heterosexism and sexism as correlates of psychological distress in lesbians. Journal of Counseling & Development, 83, 355–360.

Szymanski, D. M., & Henning, S. L. (2007). The role of self- objectification in women’s depression: A test of Objectification Theory. Sex Roles, 56, 45–53.

Szymanski, D. M., & Kashubeck-West, S. (2008). Mediators of the relationship between internalized oppressions and lesbian and bisexual women’s psychological distress The Counseling Psychologist, 36, 575–594.

Szymanski, D. M., & Owens, G. P. (2009). Group level coping as a moderator between heterosexism and sexism and psychological distress in sexual minority women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 33, 197–205.

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2001). Using multivariate statistics (4th ed.). Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Tiggemann, M., & Kuring, J. K. (2004). The role of body objectification in disordered eating and depressed mood. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 43, 299–311.

Tiggemann, M., & Slater, A. (2001). A test of objectification theory in former dancers and non- dancers. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 25, 57–64.

Wolfe, J., & Kimerling, R. (1997). Gender issues in the assessment of posttraumatic stress disorder. In J. P. Wilson & T. M. Keane (Eds.), Assessing psychological trauma and PTSD, pp. 192–238. New York: Guilford.

Worell, J., & Remer, P. (2003). Feminist perspectives in therapy: Empowering diverse women (2nd ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Worell, J., Stilwell, D., Oakley, D., & Robinson, D. (1999). Educating about women and gender: Cognitive, personal, and professional outcomes. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 23, 797–811.

Zucker, A. N., & Landry, L. J. (2007). Embodied discrimination: The relation of sexism and distress to women’s drinking and smoking behaviors. Sex Roles, 56, 193–203.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Szymanski, D.M., Gupta, A., Carr, E.R. et al. Internalized Misogyny as a Moderator of the Link between Sexist Events and Women’s Psychological Distress. Sex Roles 61, 101–109 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-009-9611-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-009-9611-y