Abstract

Using OLS regression we model predictors of housework hours for 393 Mexican origin and Anglo families from California and Arizona. Contradicting cultural theories, Mexican origin mothers performed less housework when they were employed more hours, had higher relative earnings, and when husbands had more education. Mexican origin fathers performed more housework when family income was lower, wives contributed a larger share of earnings, and fathers had more egalitarian gender ideals. Fathers’ employment hours, wives’ gender attitudes, and familism were not significantly associated with housework hours in Mexican origin families, but were significant in Anglo families. Unique features of the study include analysis of generational status, gatekeeping, and familism. Theoretical reasons for attitudes and socioeconomic status predicting housework are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Quantitative studies on the household division of labor attempt to assess how time constraints, relative resources, and gender attitudes influence the allocation of family work. These studies mainly use samples of white (Anglo) Americans and occasionally samples of African Americans, typically excluding other racial and ethnic groups or including too few individuals to make valid generalizations. As a result, we still know relatively little about how Mexican origin couples allocate household labor (Leaper and Valin 1996; Vega 1990). Simplified cultural stereotypes of machismo and marianismo have often been used to understand Mexican origin families (Denner and Dunbar 2004; Gil and Vazquez 1996; Mirandé 1997; Torres et al. 2002). Machismo is an exaggerated masculinity, which places men as the sole providers and protectors of their families (Baca Zinn 1982; Torres et al. 2002). Marianismo, the counterpart of machismo, views women’s primary roles as mothers and caretakers (Stevens 1973; Torres et al. 2002). In this study, we argue that cultural differences and gender attitudes are not the sole causes of household labor allocation in Mexican origin families. Instead, Mexican origin families in general and Mexican immigrant families in particular, should be understood in a more inclusive social context. We use interviews with Mexican Immigrant, Mexican American, and Anglo families from California and Arizona (2003) and regression analysis to examine how culture and structure are associated with household divisions of labor. We study the Mexican origin population because they are the largest (over 25 million residents) and fastest growing Latino group in the US with diverse economic and social experiences (Census 2006). In this article, we focus on the allocation of housework in the home because it is theoretically linked to economic and social processes that are particularly salient for immigrants (Baca Zinn and Wells 2003; Coltrane 1996).

Research on Divisions of Household Labor

Three “theories” dominate the empirical literature on household labor: time constraints, relative resources, and gender perspectives. In the section below, we raise questions about the extent to which these explanations are applicable to Mexican origin families.

Time Constraints

The time constraints perspective argues that housework is divided rationally according to time-related parameters, such as family composition and work schedules outside the home (Almeida et al. 1993; Coverman 1985; Hiller 1984; Shelton 1992). Family composition, like the presence of children or adults, increases household labor because additional people create more housework (Gershuny and Robinson 1998; Shelton 1992; South and Spitze 1994). Employment decreases household labor because when adults spend more time working outside of the home they have fewer hours available to dedicate to work inside the home (Blair and Lichter 1991; Demo and Acock 1993).

Time constraints are less understood for Mexican origin families because many researchers focus on cultural explanations to understand gender relations instead of structural pressures. Female employment in Latino families is often the result of extreme economic necessity (Baca Zinn and Wells 2003; Fernandez-Kelly 1990). The effects of female employment on male housework contributions are mixed in Mexican families. When Mexican origin women in the US work outside the home they ask their husbands to do more housework and childcare (Herrera and del Campo 1995; McLoyd et al. 2000). But researchers also find that female employment causes tension in US Latino families because men are likely to believe that they should be the sole financial providers (Baca Zinn and Wells 2003; Repack 1997; Zavella 1987).

Relative Resources

The relative resource perspective suggests that housework is shaped by power dynamics between husbands and wives (Blood and Wolfe 1960) and by their comparative advantage in the labor market (Becker 1991). According to this view, also labeled economic dependence or economic exchange (Gupta 2006), power relations are determined by resources brought to the partnership (Blumberg and Coleman 1989). Individuals with more resources (education, earnings, occupational prestige), relative to their spouse or the labor market, use these resources to “buy” themselves out of housework (Blair and Lichter 1991; Leaper and Valin 1996; Ross 1987).

Most researchers find that smaller gaps between husbands’ and wives’ earnings or more equal incomes are associated with more equal divisions of family labor (Blair and Lichter 1991; Kamo and Cohen 1998; Ross 1987), but this varies depending on whether earning patterns violate assumptions about male breadwinners (Bittman et al. 2003; Greenstein 2000). In addition, wives’ absolute earnings decrease their own hours of housework, but women’s earnings do not necessarily increase men’s household labor (Bittman et al. 2003; Brines 1994; Gupta 2006; Parkman 2004).

Findings on education are less consistent, with some studies finding that more educated men do less housework and have wives who do more housework (Blair and Lichter 1991) and others showing that men with higher levels of education do more (Kamo and Cohen 1998; South and Spitze 1994). Women with higher levels of education tend to perform less household labor, in part because they are generally more able to hire housework help (Coltrane 2000; South and Spitze 1994).

Mexican origin women in the United States are getting more education, but their ability to translate this into more power in the home has been mixed. Qualitative studies of Mexican origin families do not typically examine the specific effect of education on housework, but they have examined the influence of husbands’ and wives’ socioeconomic positions. Several researchers have found that a gap between the statuses of Latino men and women affects their household labor in the direction predicted by relative resource theories (Coltrane and Valdez 1993; Kamo and Cohen 1998; Pesquera 1993). Nevertheless, the prevailing assumption is that relative resources exert less influence on household labor sharing in Latino families (compared to Anglo families) because traditional gender attitudes prescribe distinct roles for mothers and fathers.

Gender Perspectives

Gender perspectives, sometimes called gender display, doing gender, or deviance neutralization (Gupta 2007) criticize both the time constraints and relative resource perspectives because they argue that housework is not divided rationally, but on the basis of cultural notions of proper gender relations (Bianchi et al. 2000; Coltrane 1989; Fenstermaker and West 2002; Ferree 1990; Greenstein 1996, 2000; South and Spitze 1994; West and Zimmerman 1987). As such, household work does not have a neutral meaning, but expresses gender relations and power dynamics within households. Moreover, the effect of time constraints, like the presence of children, differs for men and women. For example, children create more work in the home, but women usually make additional time for this new work. Men, on the other hand, do not necessarily respond to the additional demands made by children (Bianchi et al. 2000; Brines 1994; Coltrane 2000). Similarly, the effect of resources, like income, differs for men and women. Men’s housework can decrease when their wife’s income exceeds theirs; presumably because they use minimal housework to assert their masculinity (Bittman et al. 2003; Brines 1994; Hochschild and Machung 2003).

There is mixed support for the connection between gender attitudes and household behaviors (Deutsch 1999; Franco et al. 2004; Hochschild and Machung 2003). Research shows that men with more conventional (segregated) attitudes do less housework than men with more egalitarian attitudes, while women with more conventional (segregated) attitudes do more housework than women with more egalitarian attitudes (Coltrane 2000), but studies rarely specify how ethnicity or generational status might influence such patterns.

One issue that receives attention in qualitative studies, but is neglected in most quantitative housework studies, is women’s role in regulating men’s family involvement, typically labeled gatekeeping. An emerging literature (Allen and Hawkins 1999; Beitel and Parke 1998) shows that mothers play an important role in recruiting men into family work as well as restricting their participation. For example, too much involvement by fathers when family ideals do not support involvement can be interpreted as interference rather than helpfulness. Few researchers have looked at how cultural ideals in immigrant families have led women to encourage or discourage men’s participation in family labor. Familism or family loyalty can draw Mexican American men into child care, typically through segregated gender roles (Coltrane et al. 2004). Few studies have explored whether gatekeeping or familism would influence divisions of labor in both Mexican origin and Anglo families.

Ethnic Variations in Housework and Gender Relations

Scholars using ethnographic and historical data (e.g., Baca Zinn and Wells 2003; Segura 1992) argue that traditional family research ignores the salience of race and ethnicity in gender relations. Gender and ethnicity are not only categorical statuses, but also “dynamic intersectional accomplishments” (Segura 1992:164). These scholars argue that people simultaneously present themselves as belonging to, reaffirming, reproducing, and representing the categories of both gender and race/ethnicity. Family patterns in Mexican origin households are affected by a myriad of factors including national origin and generational status (Landale and Oropesa 2007). As noted above, research on Mexican families often assumes that Mexican cultural ideals of “machismo” and “marianismo” shape rigid gender roles within families, but recently scholars have questioned whether gender roles in Mexican origin families are as rigid and inflexible as the cultural stereotypes imply (Denner and Dunbar 2004; Gil and Vazquez 1996; Mirandé 1997; Torres et al. 2002). High levels of family commitment, obligation and cohesion in Mexican families are also assumed to reinforce different family roles for men and women, though this can vary by generational status (Buriel 1993; Coltrane and Valdez 1993). And contrary to stereotypes of Mexican immigrant men as macho and uninvolved in domestic activities, some studies show that first generation Mexican origin fathers are more likely to supervise and interact with children than less acculturated Mexican origin men (Coltrane et al. 2004).

Some suggest that Mexican immigrant families derive strength from a unique emphasis on familism and adherence to conventional gender ideals, whereas others suggest that these emphases are common in many immigrant groups, reflecting similar family adjustment processes (Berry et al. 2006). Later generations are the most likely to resemble other (Anglo) Americans in terms of gender egalitarian values (Adams et al. 2007; Baca Zinn and Wells 2003; Portes and Rumbaut 2001). Segura (1992) found that some traditional cultural ideals affect housework; for example, she found that Mexican women viewed housework as an expression of Mexican culture. Women reported feeling responsible for maintaining Chicano cultural traditions through their roles as wives and mothers—in other words, caretaking work in the household was their expression of Mexican culture as well as a site for expressing appropriate gendered identities (Fenstermaker and West 2002; Segura 1992; West and Zimmerman 1987). In addition, while Mexican origin women have been found to do more housework and to be more likely to approve of unequal distributions of household labor between men and women than other ethnic groups (Coltrane 2000; McLoyd et al. 2000), they often want their husbands to do more of it (Segura 1992). Paralleling findings for African American couples, some researchers find slightly more equal divisions of housework in Mexican origin families compared to Anglo families (Mirandé 1997; Shelton and John 1993), whereas some find that divisions of labor are slightly more segregated (Coltrane and Valdez 1993; Golding 1990).

In summary, theoretical and ethnographic literature suggests that divisions of household labor in Mexican origin families, compared to Anglo households, might be influenced more by cultural ideals of segregated gender spheres and strong familistic attitudes. In contrast, the literature on the division of labor in Anglo households suggests that structural factors such as education, time constraints and relative resources might exert more influence in household labor sharing. This focuses our attention on whether social structural conditions linked to social class (such as income, education and employment) versus cultural conditions linked to immigration history and ethnic identity (such as language use, generational status, familism, gender ideals, and gatekeeping) are the determining factors shaping housework allocation in these families.

This study builds on small-sample exploratory research on women’s paid and unpaid work in Latino families (e.g., Coltrane and Valdez 1993; Fernandez-Kelly 1990; Herrera and del Campo 1995; Pesquera 1993; Zavella 1987) by including almost four hundred families and conducting interviews with fathers as well as mothers. This research extends previous quantitative studies on Latino men’s domestic labor in at least three ways: (1) by focusing on housework rather than time spent in parenting activities (cf. Hofferth 2003); (2) by comparing housework in Latino families to housework in Anglo families (cf. Coltrane et al. 2004); and (3) by including a wide range of predictor variables theoretically linked to family, gender and labor processes in Latino families (cf. Shelton and John 1993). In so doing, this study provides a rare test of the relative contributions of social structural variables to divisions of labor in Mexican origin families compared to the contributions of variables based on culture—the most common assumed predictor of asymmetrical housework distribution in this ethnic group. Previous studies of household labor have rarely included enough Mexican origin families to conduct subgroup analyses, and few studies include variables measuring language usage, generational status, gender attitudes, familism, gatekeeping, and related economic and demographic variables on both mothers and fathers. This research also moves beyond most prior studies by including such measures and structuring our analyses so that we might assess the relative contributions of structure versus culture in shaping divisions of housework for Mexican and Anglo families. We are also able to assess absolute contributions to housework (as assessed by mothers) for both men and women, as well as assess the relative contributions of spouses within the marital dyad. Moreover, since gender inequality in the home has mainly been studied through the experience of Anglo Americans we examine other ways of seeing household labor that may be part of Mexican families’ experience.

Research Questions and Hypotheses

Based on the above literature review, we derived two general research questions, each with additional competing hypotheses:

-

1.

Is the division of core household labor in Mexican origin and Anglo families associated with similar structural (e.g. time constraints, relative resources) and cultural factors (e.g. segregated gender role attitudes)?

-

a.

Structural factors (e.g. time constraints and resources) will influence housework for Mexican and Anglo men and women. Greater time constraints should decrease housework for Mexican and Anglo men and women and increased resources (especially relative to their spouse’s resources) should decrease housework for Mexican and Anglo men and women.

-

b.

Cultural factors (e.g., segregated gender role attitudes) will influence housework similarly in Mexican origin and Anglo families, even though mean levels will differ. Belief in segregated gender roles will be stronger in Mexican families (than Anglo families), but Mexican origin men with stronger belief in segregated gender roles will perform less housework and Mexican origin women with stronger belief in segregated gender roles will perform more housework. Gender attitudes will be less segregated in Anglo families, but within-family associations will be similar, with Anglo men’s segregated gender attitudes associated with less housework and Anglo women’s segregated gender attitudes associated with more housework.

-

a.

-

2.

Are factors not traditionally considered in housework analyses, such as gatekeeping, ethnicity, generational status, and familism, associated with divisions of household labor?

-

a.

Gatekeeping by wives will influence the amount of housework completed by Mexican and Anglo men, with women higher on gatekeeping having husbands who perform less housework.

-

b.

Ethnicity will influence time spent on household labor for men and women, with Mexican origin women performing more housework and Mexican origin men performing less relative housework than their Anglo peers.

-

c.

For Mexican origin families, generational status will be associated with the amount of housework completed. For men, first generation status will be associated with less time on housework compared to second generation men, and for women, first generation status will be associated with more time on housework compared to second generation women.

-

d.

Stronger familism ideals will be associated with higher levels of housework for Mexican men and women (and perhaps for Anglo men and women as well).

-

a.

Method

Participants

The data for these analyses come from a larger longitudinal study of 393 Mexican origin (N = 194) and European American (N = 199; referred to as Anglo) families focused on the meaning of fatherhood and stepfatherhood. Participant families with a child in the 7th grade were recruited on a volunteer basis through cooperating school districts in California and Arizona. Districts identified target schools with high concentrations of Latino and Anglo students and worked with us to recruit families meeting the sampling criteria related to ethnicity and family type. This dual-site study collected the first wave of interviews in 2003 with seventh grade students and their mothers and fathers/stepfathers, each interviewed separately. All three family members participating in the study were required to be of the same ethnic origin, either Mexican or Anglo. This resulted in 194 interviews with Mexican origin fathers, 194 interviews with Mexican origin mothers, 199 interviews with Anglo fathers, and 199 interviews with Anglo mothers (total of 786 mothers and fathers). The two hour in-person interviews were administered and portions were tape recorded by interviewers. Respondents were also given self-administered questionnaires to report sensitive information. Respondents in California and Arizona completed surveys with identical items. Respondents were interviewed in English or in Spanish depending on their level of English fluency. Two out of three eligible families contacted agreed to participate in the study. Sample demographics are similar to those of the local population. In a separate analysis (not shown), age, education, employment status, and income characteristics for families in the populations of six school districts did not differ significantly from those of the sampled families. However, the sample did contain a greater proportion of Spanish speakers than in the general population.

Measure

Housework

Our focus in this analysis is mother’s and father’s participation in household labor. We focus on the most time consuming and repetitive household tasks, labeled “core housework,” including those that are least optional and less able to be postponed (Blair and Lichter 1991; Coltrane 2000; Robinson and Godbey 1997). We use household hours derived from the following question asked of mothers, based on items from the National Survey of Families and Households (Sweet and Bumpass 1996): How many hours in an average week (do you/does spouse) do the following? Tasks included (1) cooking or meal preparation, (2) meal clean-up and dishwashing, (3) laundry including washing, drying, and ironing clothes, (4) cleaning house, and (5) grocery shopping. We initially created two dependent variables: mother’s total hours of housework and father’s total hours of housework. Because the total hours spent on housework by individuals tells us little about the distribution of the work between spouses, we created a third dependent variable which measures father’s proportion of total couple hours. In Table 1, we present the distribution of housework for Mexican Immigrant (MI), Mexican American (MA), and Anglo mothers and fathers.

Independent Variables

The main independent variables in this analysis fall into three areas: (1) time constraints, (2) resources and (3) attitudes. We also include ethnic/racial background or generational status of respondents as a predictor of housework. Time constraints are measured by the number of paid employment hours per week that mothers and fathers report for themselves. The total number of adults in the home and the total number of children in the home are also included as continuous variables. Several measures of resources are also included: (1) total household income is log transformed to normalize its distribution; (2) mother’s proportion of couple income is computed by dividing mother’s earnings by total couple earnings, and (3) father’s and mother’s education are measured by highest year of education completed.

Segregated Gender Role Attitudes

Mothers’ and fathers’ gender attitudes are measured using five items (1–5 below) about separate work and family roles for men and women (Knight et al., submitted), seven items (6–12) about masculinity ideals for men (Pleck et al. 1994), and two items (13–14, designed for this study) on provider role ideals for fathers. All items assess respondents’ endorsement of segregated gender roles and fathers and mothers were asked the same questions:

-

1.

Men should earn most of the money for family so women can stay home and take care of the children and home.

-

2.

It is important for the man to have more power in the family than the woman.

-

3.

Mothers are the main person responsible for raising children.

-

4.

A wife should always support her husband’s decisions, even if she doesn’t agree with him.

-

5.

A man should help in the house, but housework and child care should mainly be a woman’s job.

-

6.

It is essential for a man to get respect from others.

-

7.

It bothers me when a guy acts like a girl.

-

8.

I admire a man who is totally sure of himself.

-

9.

A man will lose respect if he talks about his problems.

-

10.

A young man should be physically tough.

-

11.

A man always deserves the respect of his wife and children.

-

12.

I don’t think a husband should have to do housework.

-

13.

Supporting your family financially is the most important thing you do as a father (your partner does as a father).

-

14.

Working extra hours shows that you are a good father (your partner is a good father).

Items 1–5 range from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5); items 6–12 range from strongly agree (1) to strongly disagree (4), recoded so that higher scores reflect stronger endorsement of segregated gender roles; and items 13–14 range from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (4). The combined gender scale scores for fathers’ and mothers’ range from 14 to 60, with higher scores reflecting preference for more segregated gender roles. (Fathers: α = .80; mothers: α = .75).

Gatekeeping

We constructed a ten-item gatekeeping scale, based on prior work by Allen and Hawkins (1999) and Beitel and Parke (1998), asking both mothers and fathers about the mother’s regulation and assessment of men’s family work. Items for the gatekeeping scale (mother’s version) include: (1) “In the past 3 months, you frequently re-did some household tasks that your (husband/partner) had not done well,” (2)“You had higher standards than your (husband/partner) did for how well cared-for the house should be,” (3)“You had higher standards than your (husband/partner) did for how well cared-for the children should be,” (4) “You liked being in charge when it came to household tasks and caring for the children,” and (5) “You scheduled household tasks and childcare for your (husband/partner).” Fathers’ items were slightly reworded, for example, “In the past 3 months, your (wife/partner) frequently re-did some household tasks that you had not done well.” Values for mothers’ and fathers’ items ranged from 1 = Very false to 4 = Very true (with very true reflecting high level of mothers’ gatekeeping). Mothers’ and fathers’ scores for these items were combined because they report couple level behaviors, resulting in scale scores ranging from 10 to 40, with high scores on the scale indicating that mothers are strong gate keepers (gatekeeping: α = .73).

Familism

Two subscales from the Mexican American Cultural Values Scale (Knight et al., submitted), familism-support and familism-obligation, were used to create the 10 item familism scale used in this analysis. Representative items include: “It is always important to be united as a family,” “Children should be taught that it is their duty to care for their parents when their parents get old,” and “It is important to have close relationships with aunts/uncles, grandparents and cousins.” Respondents’ answers to these items ranged from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. The total scale scores range from 10 to 50, with higher scores reflecting a stronger belief in familism (fathers: α = .75; mothers: α = .78).

Generational Status

To determine generational status, we used respondents’ place of birth, parent’s place of birth, and age at arrival to US Respondents were classified into (1) Mexican Immigrant and (2) Mexican American categories. Mexican Immigrants are first generation; they were born in Mexico and arrived in the US after the age of eight (MI fathers N = 122, MI mothers = 126). Mexican Americans include 1.5, second, and third generations. The 1.5 generation was born in Mexico, but arrived in the US before age 8; the second generation was born in the US but their parents were born in Mexico; and the third generation was born in the US and their parents were born in the US (MA fathers N = 72, MA mothers = 68).

Analysis

In this analysis, we provide descriptive statistics for Mexican Immigrant, Mexican American, and Anglo families to show the group differences on various structural and cultural variables; Tukey tests show significant differences in the mean characteristics of Mexican origin and Anglo families (Table 1). For the regressions analysis, we group Mexican American and Mexican Immigrant respondents to examine the effect of generational status on housework. After pooling Mexican origin families, we run separate regressions for Mexican origin and Anglo men and women which allows us to analyze whether potential predictors of housework are similar across ethnic groups (Tables 2 and 3). Pooled regressions are included for several reasons. First, in pooled regressions ethnicity is included as a control variable to examine the direct effect of ethnicity on housework. Second, in pooled regressions we test ethnic and generational interactions with the independent variables (we find only one significant interaction with mothers’ proportion of couple income, included in Table 2).

Results

Descriptive Findings

The descriptive results in Table 1 show marked differences between Mexican origin and Anglo families. The first two columns report characteristics of Mexican immigrant and Mexican American families. The third column reports the characteristics of Anglo families. The fourth and fifth columns present the analysis of variance F-statistics and the Tukey post hoc test for significant mean differences among the three groups. Mexican Immigrant mothers are likely to do more housework compared to Mexican American and Anglo mothers. This result fits with their likelihood to work fewer hours, have more adults and children in the home, have lower incomes, and be less educated, compared to Mexican American and Anglo mothers. In addition, Mexican immigrant mothers have higher segregated gender role attitudes, gatekeeping attitudes, and familism attitudes compared to Mexican American and Anglo mothers. Mexican American mothers also spend more hours on housework; have larger household sizes, less income, less education, and more segregated gender attitudes compared to Anglo mothers.

Fathers spend less time on housework compared to mothers. There are no statistically significant mean differences in fathers’ absolute housework hours, but fathers’ proportionate share of housework differs significantly among Mexican immigrant, Mexican American, and Anglo fathers. Mexican immigrant men contribute the smallest proportion to housework, followed by Mexican American, and Anglo men. This housework difference does not appear to be a result of differences between fathers’ hours of paid work. However, there are significant differences across the three groups in income, education, and attitudes.

These descriptive findings point to the power of structure and culture to shape the division of labor and call attention to significant differences between Mexican immigrant and Mexican American families that might be explained by generational status.

Regression Analysis

Tables 2 and 3 test hypotheses about the influence of structure and culture on housework hours for Mexican and Anglo men and women. Table 2 examines predictors for mother’s housework hours. Because previous research suggests father’s relative contributions are best captured using a proportionate measure, Table 3 includes father’s proportion of total couple housework in addition to the absolute hours of housework he performs. In both tables, there are separate models for Mexican and Anglo men and women, and pooled models that allow us to test hypotheses about ethnic differences in housework. To test hypotheses about the effects of generational status on housework, generational status was included as a predictor in regression models for Mexican origin families.

We find some support for the effect of structural factors on housework (Hypothesis 1a) since time constraints, such as paid work and the number of children have significant and marginally significant effects on housework for Mexican origin and Anglo men and women. Mother’s paid hours of work is associated with fewer hours of housework for women and father’s paid hours of work is associated with fewer hours of housework for men in both ethnic groups. Also, the number of children in the home has marginal effects on women’s housework and no effects on men’s. Another structural factor, resources, is associated with housework. In particular there are marginal effects of log income for mother’s housework. In models predicting father’s housework, log income is associated with fewer hours of father’s housework. Supporting relative resource theories, mother’s proportion of couple income is consistently associated with housework for men and women. It appears that women with higher relative resources in income can decrease their housework and increase the housework of their spouses. Education, on the other hand, only has some marginal influence on housework for women. In models predicting housework for men, education did not significantly affect father’s housework.

We find mixed support for Hypothesis 1b that cultural factors influence housework similarly for Mexican origin and Anglo families. Mothers’ segregated gender role attitudes did not influence their housework hours (Table 2), but Anglo mothers living with men who held more segregated gender attitudes did less housework and also performed a greater proportion of total housework hours (Table 3). In addition, Mexican origin fathers’ segregated gender role attitudes are associated with fewer hours of housework by these men. In a separate analysis, not shown here, we included an interaction term for segregated gender role attitudes and father’s housework in the models for all fathers and it did not reach statistical significance.

We also find some support for hypotheses associated with our second research question about new factors to consider in household labor studies. Regarding Hypothesis 2a, gatekeeping was not associated with mother’s housework, but was associated with father’s housework (both hours and proportion of housework in models for all fathers: see Table 3). Although the effects of gatekeeping did not reach statistical significance in the separate models by ethnicity for fathers, the significant finding for the pooled sample of all fathers suggests that gatekeeping is a predictor of housework that needs further consideration in future research.

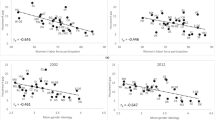

We find mixed support for Hypothesis 2b, as ethnicity was a significant predictor of mothers’ housework hours in the model for all mothers (Table 2) but was not related to fathers’ hours of housework or fathers’ proportion of housework (Table 3). There is additional support for the influence of ethnicity on housework when we test for ethnic differences across the models by including interaction effects with various independent variables (Hypothesis 2b). There are significant ethnic differences in the effect of mother’s proportion of income on mother’s household labor (Table 2). Mother’s proportion of couple income has different effects on housework for Mexican origin and Anglo women. Housework for Mexican origin women decreases at a greater rate compared to Anglo women as their proportion of couple income increases (Fig. 1).

In support of Hypothesis 2c, first generation Mexican immigrant women did more absolute hours and proportion of housework than second and later generation Mexican Americans (Table 1). Although first generation Mexican immigrant men did less housework than second and later generation Mexican Americans these differences did not reach statistical significance (Table 1). In regression models for Mexican origin families we also include generational status as a predictor of housework, in part because there are mean differences in structural and cultural factors by generational status among Mexican families. Our analysis shows that when controlling for these other structural and cultural factors, differences in generational status did not significantly affect housework for Mexican men or women. In a separate analysis (not shown here), we tested for interaction effects between generational status and independent variables. We did not find significant interactions between generational status and the independent variables. However, the lack of difference may be an artifact of the sample size of Mexican Americans relative to Mexican Immigrants.

Finally, regarding Hypothesis 2d, there is mixed support for the effect of familism on housework. Familism ideals are associated with increased housework in regression models for Anglo fathers (Table 3), but we did not find that mothers’ housework is significantly associated with higher levels of familism. Also, in pooled regressions for all mothers (Tables 2), mothers’ familism ideals are significantly associated with higher levels of housework. Similarly, in models for all fathers (Table 3), increased father’s familism ideals are associated with higher levels of father’s household hours and father’s proportion of housework hours. These findings counter previous assumptions about the strong role of familism in Mexican families and its weak role in Anglo families.

Discussion

This article investigates several aspects of the division of household labor. The three aspects are a) structural effects on household labor b) cultural effects on household labor c) and possible ethnic differences in household labor between Mexican origin and Anglo families. We find few ethnic differences in structural (e.g. time constraints and resources) and cultural (e.g. gender segregated attitudes) predictors of housework. Even though many previous findings about Mexican origin families used culture-centered explanations to explain gender roles (Denner and Dunbar 2004; Gil and Vazquez 1996; Mirandé 1997; Torres et al. 2002), we find that for Mexican origin families, housework responds to structural factors in a similar fashion as for Anglo families (Hypothesis 1a). Even though previous research points to culture as the primary determinate of housework for Mexican families, we find that culture (at least in the form of segregated gender role attitudes) does not influence housework differently for Mexican and Anglo families. In other words, Mexican and Anglo families respond similarly to practical demands, like time constraints and resources, when dividing household labor.

We did discover one provocative ethnic difference: mother’s relative income had stronger effects on mothers’ housework hours for Mexican origin than for Anglo mothers. In our analysis, women’s greater relative earnings worked in their favor because it is associated with less time spent on housework (see Gupta 2007), but also because it is associated with more housework on the part of their husbands. As noted, this effect is most evident for Mexican origin women (see Fig. 1). When Mexican origin women earn more of the couple income, they do less housework and their male partners do more housework, resulting in significantly more equal divisions of domestic labor. This finding contradicts previous assumptions that relative resources exert less influence on household labor sharing in Latino families compared to Anglo families. This also supports previous studies which suggest that small gaps in the statuses of men and women create more egalitarian divisions of housework (Coltrane and Valdez 1993; Kamo and Cohen 1998; Pesquera 1993). In our analysis, wife’s time demands are not associated with husbands’ housework, but greater income levels compared to husband earnings carries more bargaining power. These differences do not appear to be a result of cultural attitudes about appropriate gender roles for men and women. Perhaps this ethnic difference in the effect of relative income is a result of differences in Mexican origin men’s labor force participation or income and such questions are worthy of further study.

One of the most interesting findings of this study is that cultural differences, for the most part, do not influence housework differently for Mexican origin and Anglo families (Hypothesis 1b). Compared to Anglo families, Mexican origin families do have more traditional cultural values, but there is little evidence to suggest that these differences determine their household division of labor. Since culture is used as the default explanation for household labor in Mexican origin families, these findings point to the importance of including structural variables related to time use, employment and income for both men and women. We caution readers, however, to not interpret this finding as reason to exclude culture from future housework analysis. Our cultural findings may reflect differential salience of segregated gender role attitude measures in Mexican origin families compared to Anglos, especially for mothers. Our results suggest that there are cultural differences as well as structural differences in Mexican and Anglo experiences, particularly related to men’s gender attitudes, and this is an area of study that requires much more detailed analysis.

Finally, this study also suggests that it is useful to include factors that are not traditionally considered in housework analyses. Previous research on the household divisions of labor has not systematically examined the effects of gatekeeping, ethnicity, generational status, and familism on housework. Although our findings are tentative and somewhat mixed, we find support for the idea that gatekeeping by wives is associated with less housework by husbands. As suggested by the gender perspective, housework does not have a neutral meaning, but expresses gender relations in the home, and gatekeeping is a means to “do gender” on a routine basis (Fenstermaker and West 2002). Although there are few significant differences in the effect of independent variables and ethnicity on housework, we did find that including ethnicity is important in predicting housework for women. Net of all predictors, Mexican women spend more time on household labor compared to Anglo women. This finding is both intriguing and perplexing because our analyses control for many variables related to different home environments for Mexican origin and Anglo women. The different environments in and of themselves did not account for the housework differences between Mexican and Anglo women. Structural differences had consistent effects on women’s housework and explain some of the differences in Mexican origin women’s increased housework. Cultural differences may be less evident in our analysis because there is less variance in gender attitudes among Mexican origin women and higher support for the idea that women should be the primary person to care for home and family. Mexican women may have more traditional gender role attitudes, but at the same time structural differences are especially salient (e.g. less income, more children, and less education), so they may see increased household labor as a necessity they cannot avoid. In this analysis we did not find a strong connection between generational status and housework, but future research should strive to include greater numbers of Mexican American compared to Mexican Immigrant respondents to increase statistical power. Our findings may also reflect the fact that cultural ideals alone do not drive divisions of domestic labor. Mexican immigrant families may respond to a myriad of practical pressures in maintaining their homes and raising their children just like Mexican American families.

Finally, we find some support for our hypothesis about familism. Our original hypothesis predicted a positive relationship between familism and housework for Mexican origin families, and perhaps Anglo families (Hypothesis 2d). Our findings are surprising because we did not find strong direct effects of housework on Mexican origin families, but we did find direct effects of familism for Anglo families. This finding is important for several reasons. First, this finding shows that emphasizing familism only as important for Mexican origin families is too narrow. Previous research (Coltrane et al. 2004) suggests that Mexican origin families have a unique sense of familism and adherence to conventional gender ideals. We did not find the effect of familism to be unique to Mexican origin families. In fact, the role of familism in housework, at least in this analysis, has similar affects for Mexican and Anglo families suggesting that both respond to cultural ideals of family loyalty in a similar manner. Second, according to previous research, high levels of familism create a more unequal distribution of household labor. However, we find that increased levels of familism are associated with higher levels of housework for men as well as women. If cultural ideals of family loyalty draw families into more family cooperation, then it is likely that increased housework will be part of this cooperation. Third, these findings suggest that we should continue to examine the role of familism to better understand its effects on housework.

Our analysis shows that relying exclusively on cultural explanations to explain gender roles can be misleading. A cultural view suggests that Mexican families maintain rigid gendered behaviors in which women take on the role of mother and caretaker and men assume the roles of financial provider and family head (Baca Zinn 1982; Stevens 1973; Torres et al. 2002). Segregated gender role attitudes, in this view, largely determine family roles. However, in this analysis, we did not find evidence that attitudes are stronger determinants of women’s housework than other factors. In fact, we find that Mexican Immigrant and Mexican American families respond to practical concerns like time constraints and relative resources rather than automatically responding to normative cultural pressures.

Limitations of the present study include a focus on just Anglo and Mexican origin families (rather than all Latino groups) and on two-parent families rather than other family forms. Another limitation is that we have mother’s reports on father’s housework and lack father’s own reports of housework, even though we have fathers’ reports about parenting and socioeconomic variables. This might lead to an underestimation of housework participation for fathers. In addition, our sample includes a preponderance of first generation Mexican Immigrant families, and this group might possess specific characteristics that are not generalizable to other groups. In addition, we focus on core repetitive housework tasks that reflect gender differences and gender equity imbalance, rather than on traditional masculine contributions that might make divisions of family labor seem more balanced. We do so, however, because of the prevailing assumption that divisions of labor in Mexican origin families are predetermined by rigid gender dichotomies and patriarchal family arrangements. In contrast to such theories and popular ideals, we find that overall income levels, household composition, and relative spousal contributions to earnings are the best predictors of housework sharing in Mexican origin families. Although culture clearly matters in these families, our findings suggest that structure exceeds culture in its influence on dividing the mundane tasks of family life.

References

Adams, M., Coltrane, S., & Parke, R. D. (2007). Cross-ethnic applicability of the gender-based attitudes toward marriage and child rearing scales. Sex Roles, 56, 325–339.

Allen, S. M., & Hawkins, A. J. (1999). Maternal gatekeeping: Mothers beliefs and behaviors that inhibit greater father involvement in family work. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 61, 199–212.

Almeida, D. M., Maggs, J., & Galambos, N. (1993). Wives’ employment hours and spousal participation in family work. Journal of Family Psychology, 7, 233–244.

Baca Zinn, M. (1982). Chicano men and masculinity. The Journal of Ethnic Studies, 10, 29–44.

Baca Zinn, M., & Wells, B. (2003). Diversity within latino families: New lessons for family social science. In A. S. Skolnick, & J. H. Skolnick (Eds.), Family in transition(12th ed.). Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

Becker, G. S. (1991). A treatise on the family (Enl. ed.). Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.

Beitel, A., & Parke, R. D. (1998). Parental involvement in infancy: The role of maternal and paternal attitudes. Journal of Family Psychology, 12, 268–288.

Berry, J. W., Phinney, J. P., Sam, D. L., & Vedder, P. (2006). Immigrant youth in cultural transition: Acculturation, identity, and adaptation across national contexts. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Bianchi, S. M., Milkie, M. A., Sayer, L. C., & Robinson, J. P. (2000). Is anyone doing the housework?: Trends in the gender division of household labor. Social Forces, 79, 191–228.

Bittman, M., England, P., Sayer, L. C., Folbre, N., & Matheson, G. (2003). When does gender trump money? Bargaining and time in household work. American Journal of Sociology, 109, 186–214.

Blair, S., & Lichter, D. (1991). Measuring the division of household labor: Gender segregation of housework among American couples. Journal of Family Issues, 12, 91–113.

Blood, R. O., & Wolfe, D. M. (1960). Husbands and wives: The dynamics of married living. Glencoe, Ill: Free Press.

Blumberg, R. L., & Coleman, M. T. (1989). A theoretical look at the gender balance of power in the American couple. Journal of Family Issues, 10, 225–250.

Brines, J. (1994). Economic dependency, gender, and the division of labor at home. American Journal of Sociology, 100, 652–688.

Buriel, R. (1993). Childrearing orientations in Mexican American families: The influence of generation and sociocultural factors. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 55, 987–1000.

Census, U. S. B. (2006). American Community Survey 2004, Retrieved March 24, 2006, from http://factfinder.census.gov/.

Coltrane, S. (1989). Household labor and the routine production of gender. Social Problems, 36, 473–490.

Coltrane, S. (1996). Family man: fatherhood, housework, and gender equity. New York: Oxford University Press.

Coltrane, S. (2000). Research on household labor: Modeling and measuring the social embeddedness of routine family work. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62, 1208–1233.

Coltrane, S., Parke, R. D., & Adams, M. (2004). Complexity of father involvement in low-income Mexican-American Families. Family Relations, 53, 179–189.

Coltrane, S., & Valdez, E. O. (1993). Reluctant compliance: Work-family role allocation in dual-earner Chicano families. In J. C. Hood (Ed.), Men, Work, and Family (pp. 151–175). Newbury Park: Sage.

Coverman, S. (1985). Explaining husbands’ participation in domestic labor. The Sociological Quarterly, 26, 81–97.

Demo, D. H., & Acock, A. C. (1993). Family diversity and the division of domestic labor: How much have things really changed? Family Relations, 42, 323–331.

Denner, J., & Dunbar, N. (2004). Negotiating femininity: Power and strategies of Mexican American girls. Sex Roles, 50, 301–314.

Deutsch, F. (1999). Halving it all: How equally shared parenting works. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Fenstermaker, S., & West, C. (2002). Doing gender, doing difference: Inequality, power, and institutional change. New York: Routledge.

Fernandez-Kelly, P. (1990). Delicate transactions: Gender, home, and employment among Hispanic women. In F. Ginsberg, & A. L. Tsing (Eds.), Uncertain terms: Negotiating Gender in American Culture (pp. 183–195). Boston: Beacon.

Ferree, M. M. (1990). Beyond separate spheres: Feminism and family research. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 52, 866–884.

Franco, J. L., Sabattini, L., & Crosby, F. J. (2004). Anticipating work and family: Exploring the associations among gender-related ideologies, values, and behaviors in Latino and white families in the United States. The Journal of Social Issues, 60, 755–766.

Gershuny, J., & Robinson, J. P. (1998). Historical shifts in the household division of labor. Demography, 25, 537–553.

Gil, R. M., & Vazquez, C. I. (1996). The Maria paradox: How Latinas can merge Old World traditions with New World self-esteem. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons.

Golding, J. M. (1990). Division of labor, strain, and depressive symptoms among Mexican American and Non-Hispanic whites. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 14, 103–117.

Greenstein, T. N. (1996). Husbands’ participation in domestic labor: Interactive effects of wives’ and husbands’ gender ideologies. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 58, 585–595.

Greenstein, T. N. (2000). Economic dependence, gender, and the division of labor in the home: A replication and extension. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62, 322–335.

Gupta, S. (2006). Her money, her time: Women’s earnings and their housework hours. Social Science Research, 35, 975–999.

Gupta, S. (2007). Autonomy, dependence, or display? The relationship between married women’s earnings and housework. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 69, 399–417.

Herrera, R. S., & del Campo, R. L. (1995). Beyond the superwoman syndrome: Work satisfaction and family functioning among working-class, Mexican-American women. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 17, 49–60.

Hiller, D. V. (1984). Power dependence and division of family work. Sex Roles, 10, 1003–1019.

Hochschild, A. R., & Machung, A. (2003). The second shift. New York: Penguin Books.

Hofferth, S. L. (2003). Race/Ethnic differences in father involvement in two-parent families: Culture, context, or economy. Journal of Family Issues, 21, 185–215.

Kamo, Y., & Cohen, E. L. (1998). Division of household work between partners: A comparison of black and white couples. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 29, 131–136.

Landale, N. S., & Oropesa, R. S. (2007). Hispanic families: Stability and change. Annual Review of Sociology, 33, 381–405.

Leaper, C., & Valin, D. (1996). Predictors of Mexican American mothers’ and fathers’ attitudes toward gender equality. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 18, 343–355.

McLoyd, V. C., Cauce, A. M., Takeuchi, D., & Wilson, L. (2000). Marital processes and parental socialization in families of color: A decade review of research. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62, 1070–1093.

Mirandé, A. (1997). Hombres y machos: Masculinity and latino culture. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Parkman, A. M. (2004). Bargaining over housework—The frustrating situation of secondary wage earners. American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 63, 765–794.

Pesquera, B. M. (1993). “In the beginning he wouldn’t lift even a spoon”: The division of household labor. In A. de la Torre, & B. M. Pesquera (Eds.), Building with our hands: New Directions in Chicana Studies (pp. 181–198). Berkeley: University of California Press.

Pleck, J. H., Sonenstein, F. L., & Ku, L. C. (1994). Attitudes toward male roles among adolescent males: A discriminant validity analysis. Sex Roles, 30, 481–501.

Portes, A., & Rumbaut, R. G. (2001). Legacies: The story of the immigrant second generation. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Repack, T. A. (1997). New rules in a new landscape. In M. Romero, P. Hondagneu-Sotelo, & V. Ortiz (Eds.), Challenging fronteras: Structuring Latina and Latino lives in the U.S. (pp. 247–257). New York: Routledge.

Robinson, J. P., & Godbey, G. (1997). Time for life: The surprising ways Americans use their time. University Park, Pa: Pennsylvania State University Press.

Ross, C. E. (1987). The division of labor at home. Social Forces, 65, 816–833.

Segura, D. A. (1992). Chicanas in white-collar jobs: You have to prove yourself more. Sociological Perspectives, 35, 163–182.

Shelton, B. A. (1992). Women, men, and time: Gender differences in paid work, housework, and leisure. New York: Greenwood.

Shelton, B. A., & John, D. (1993). Ethnicity, race, and difference: A comparison of white, black, and Hispanic man’s household labor time. In J. C. Hood (Ed.), Men, work, and family (pp. 131–150). Newbury Park: Sage.

South, S. J., & Spitze, G. (1994). Housework in marital and nonmarital households. American Sociological Review, 59, 327–347.

Stevens, E. P. (1973). Machismo and marianismo. Society, 10, 57–63.

Sweet, J. A., & Bumpass, L. L. (1996). The national survey of families and households—waves 1 and 2: Data description and documentation.

Torres, J. B., Solberg, V. S., & Carlstrom, A. H. (2002). The myth of sameness among Latino men and their machismo. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 72, 163–181.

Vega, W. (1990). Hispanic families in the 1980s: A decade of research. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 52, 1015–1024.

West, C., & Zimmerman, D. (1987). Doing gender. Gender & Society, 1, 125–151.

Zavella, P. (1987). Women’s work & Chicano families: Cannery workers of the Santa Clara Valley. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press.

Acknowledgements

Support for this project was provided by grants from NIH: MH 64828, “Effects and Meaning of Fathers for Adolescents: UCR Site” (Scott Coltrane, principal investigator), and “Effects and Meaning of Fathers for Adolescents: ASU Site” (Sanford Braver, principal investigator). We thank the UC Riverside Center for Family Studies and the ASU Prevention Intervention Research Center for technical and material support. We especially thank Ross Parke, Ernestine Avila and Kate Luther for valuable conceptual and practical assistance, Leisy Abrego, Gloria Gonzalez, and Roberto Montenegro for careful reading of a previous version of this manuscript, Jennifer C. Chang for editorial assistance, and the anonymous reviewers of Sex Roles for their constructive comments. We also express our profound gratitude to the many families who shared their experiences by participating in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pinto, K.M., Coltrane, S. Divisions of Labor in Mexican Origin and Anglo Families: Structure and Culture. Sex Roles 60, 482–495 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-008-9549-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-008-9549-5