Abstract

This study examined a pathway to heterosexual women’s experience of anger and anxiety in response to lesbian interactions. Participants were 149 18–30 year old heterosexual female undergraduates (56% African American) from a southeastern United States university. Participants completed measures of female gender role beliefs, sexual prejudice, and state affect, viewed a video depicting relationship behavior between a female–female or male–female dyad, and again completed a measure of state affect. Results indicated that traditional beliefs about women were associated with higher levels of sexual prejudice toward lesbians. In turn, higher levels of sexual prejudice predicted increased anger (not anxiety) in response to the female–female, but not the male–female, dyad. Findings elucidate determinants of heterosexual women’s anger, and potentially aggression, toward lesbians.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Aggression and discrimination toward sexual minorities is a widespread phenomenon observed in numerous countries and cultures (NCAVP 2007; Takács 2006). Given that the majority of research in this domain has involved male samples, the present study was designed to examine a potential pathway to heterosexual women’s experience of anger and anxiety to lesbians. A racially diverse sample of heterosexual, undergraduate women (56% African American) was recruited from a southeastern United States university. An experimental design was employed to manipulate participants’ exposure to relationship behavior between a male–female or a female–female dyad. Theory pertinent to gender role socialization and identity misclassification guided our aim to determine whether sexual prejudice mediated the effect of female gender role beliefs on anger and anxiety in response to female–female, but not male–female, relationship interactions. This research represented the first experimental test of this pathway in a sample of young women and has direct implications for women’s perpetration of aggression toward lesbians. Also, because of the diverse sample, this research provided the opportunity to evaluate whether racial differences between African American and Caucasian women moderated the expression of anti-lesbian anger and anxiety.

A large body of research has examined sex differences in attitudes toward sexual minorities (for a review, see Kite 1984; Kite and Whitley 2003; Whitley and Kite 1995). These studies have consistently demonstrated that heterosexual men, relative to heterosexual women, report more negative attitudes (i.e., higher sexual prejudice) toward gay men than toward lesbians (Gentry 1987; Herek 1988; Kite 1994; Lim 2002; Whitley 1987). Research also indicates that heterosexual women, compared to heterosexual men, report more negative attitudes toward lesbians (Gentry 1987; Whitley 1987, 1990), although other studies have shown that men and women hold similar attitudes toward lesbians (Herek 1988; Kite 1984; Kite and Whitley 1996). Nevertheless, heterosexual men’s attitudes toward gay men tend to be more negative than heterosexual women’s attitudes toward lesbians (Herek 2002; Kite and Whitley 1996). These findings, which are based largely upon collegiate samples, have been replicated in national adult samples (Herek and Capitanio 1995, 1996).

Numerous explanations for these differences have been advanced, including sex differences in one’s defensiveness surrounding homosexuality (Herek 1986, 1988), the eroticization of lesbians by heterosexual men (Louderback and Whitley 1997), and sex differences in interpersonal contact with gay men or lesbians (Herek and Capitanio 1996). Most notably, however, socialization pressures to adhere to traditional gender roles are believed to elicit higher levels of sexual prejudice in men and women (Herek 1986; Kite and Whitley 1996, 1998). For example, Herek (1984, 1986, 1988) posited that one function of sexual prejudice is to make clear distinctions between male and female gender roles. In short, sexual prejudice serves a social-expressive function that differentiates an individual’s heterosexual in-group from the homosexual out-group (Herek 1986). This effect is thought to be especially pronounced among heterosexual men, because gender norms are more rigidly prescribed for, and adhered to by, men than women (Bosson et al. 2006; Herek 1986; Hort et al. 1990). Indeed, theorists agree that heterosexual men’s repudiation of feminine attributes in other men (e.g., holding negative attitudes toward gay men) functions largely to affirm heterosexual masculine identity (Franklin 1998; Hamner 1990; Kimmel 1997; Kite and Whitley 1998). In accordance with this view, research on heterosexual men suggests that sexual prejudice is likely a product of masculine socialization (Shields and Harriman 1984), especially endorsement of an antifemininity theme within the male role (Parrott et al. 2002; Thompson et al. 1985).

A better understanding of heterosexual men and women’s attitudes toward sexual minorities, and the function of those attitudes, is clearly important. However, the extent to which these attitudes translate into negative emotional or behavioral responses toward sexual minorities is of equal, if not greater, social importance. To this end, research indicates that endorsement of traditional male gender role beliefs predicts increased anger and aggression toward gay, but not heterosexual, men (Parrott and Zeichner 2008). Similarly, experimental and correlational studies have demonstrated that heterosexual men’s self-reported sexual prejudice predicts increased anger and bias-motivated aggression toward gay men (Bernat et al. 2001; Franklin 2000; Parrott and Zeichner 2005; Patel et al. 1995; Roderick et al. 1998). These studies suggest that men who endorse traditional beliefs about the male gender role and higher levels of sexual prejudice are particularly likely to express anti-gay anger and aggression.

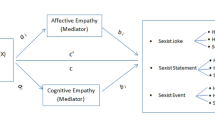

Pertinent literature sheds light on a potential pathway by which adherence to traditional male gender norms and sexual prejudice may translate into aggression toward gay men. Recent research with heterosexual men suggests that sexual prejudice mediates the association between traditional male gender role beliefs and anger in response to gay men (Parrott et al. 2008) and that the experience of anger in response to gay men accounts for the association between sexual prejudice and aggression toward gay men (Parrott and Peterson 2008). Taken together, these findings suggest that men’s adherence to traditional male gender norms elicits sexual prejudice, sexual prejudice facilitates the experience of anger in response to gay men, and anti-gay anger motivates aggression toward gay men. Like sexual prejudice, these emotional and behavioral anti-gay responses (e.g., anger, aggression) presumably function to affirm heterosexual masculine identity and are motivated by societal pressure on men to maintain boundaries between male and female gender roles (Herek 1986).

Notably, pertinent research also suggests that sexually prejudiced men’s experience of anxiety in response to gay men activates an anger-related cognitive bias that may also facilitate anti-gay aggression (Parrott et al. 2006). Given that the experience of anxiety in response to gay men has been associated with subsequent aggression toward gay, but not heterosexual, men (Bernat et al. 2001), this cognitive bias may represent another important determinant of aggression toward gay men. In sum, the collective literature suggests that the experience of anger and anxiety in response to gay men are important precursors of male-perpetrated anti-gay aggression.

Gender Role Ideology and Anti-Lesbian Responses: A Similar Mechanism in Women?

The reviewed literature suggests that the link between gender role socialization and negative attitudes toward sexual minorities, anger and anxiety, and anti-gay aggression is largely a male phenomenon. Indeed, data from national samples indicate that heterosexual men are the most likely perpetrators of aggression toward sexual minorities and that men who identify as gay, bisexual, or a person of male-to-female transgender experience are the most common victims of these attacks (National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs 2007; Federal Bureau of Investigation 2006). However, it would be unreasonable to presume that heterosexual women are not sexually prejudiced, that women do not experience negative emotions in response to sexual minorities, or that women do not discriminate or aggress toward sexual minorities. Indeed, relative to sex differences in attitudes toward gay men and lesbians, sex differences in attitudes toward homosexual behavior are less pronounced (Kite and Whitley 1996). Thus, men and women may evince somewhat similar emotional and behavioral reactions to homosexual behavior. Moreover, meta-analytic research suggests that endorsement of traditional gender role beliefs, regardless of one’s gender, is the most important predictor of attitudes toward gay men and lesbians (Herek 1988; Kite and Whitley 1996; Whitley 2001).

Collectively, these data suggest that, like heterosexual men (e.g., Parrott et al. 2008), heterosexual women’s endorsement of traditional gender role ideology may be a critical precursor of negative attitudes and emotional reactions toward sexual minorities. This research is consistent with pertinent theories that emphasize gender role socialization and anti-gay or anti-lesbian attitudes as determinants of negative emotional or behavioral responses toward gay men and lesbians (Herek 1986; Kite and Whitley 1996, 1998). In addition, this research is consistent with identity misclassification theory (Bosson et al. 2005), which refers to a person’s “misclassification into a devalued social group on the basis of their role-violating behaviors, interests, or pursuits” (pg. 552). According to this view, social pressures to conform to gender role norms facilitate heterosexual men and women’s adherence to those norms. As a result, the anticipation of being mistakenly classified as homosexual leads to an aversive state when exposed to relevant gender role violations. Recent research supports this hypothesis in both men and women (Bosson et al. 2006). Indeed, the experience of negative affect may be the “emotional foundation” for subsequent feelings of anger and anxiety (Berkowitz 1990). Unfortunately, research to date has not directly examined the extent to which females’ gender role beliefs or anti-lesbian attitudes predict anti-lesbian emotional responses in response to actual lesbian behavior. Indeed, the need for more research on determinants of negative responses toward sexual minorities has been echoed in the extant literature (e.g., Kite and Whitley 2003). Without theoretically-driven research in this area, researchers’ ability to make informed predictions regarding a woman’s risk of anti-lesbian discrimination and aggression will remain limited.

Thus, the next logical step in this line of research is to determine whether heterosexual women’s endorsement of traditional gender role ideology is a precursor of sexual prejudice and negative emotional reactions (e.g., increases in anger and anxiety) in response to lesbians. Upon establishing determinants of emotional responses to lesbians, subsequent research will be better equipped to identify salient factors and interrelationships among those factors that may provoke anti-lesbian aggression in female assailants.

The Present Study

The overarching aim of the present investigation was to evaluate a theoretically-based pathway to heterosexual women’s experience of negative emotion in response to lesbians. As reviewed above, pertinent theory has linked adherence to traditional gender norms and sexual prejudice in men and women (e.g., Herek 1986; Kite and Whitley 1996, 1998). Moreover, research has demonstrated that endorsement of traditional gender norms and sexual prejudice are critical precursors to anti-gay anger, anxiety, and aggression among heterosexual men (e.g., Bernat et al. 2001; Parrott and Peterson 2008; Parrott et al. 2008). Based on this literature, it was hypothesized that traditional female gender role beliefs would be associated with higher levels of sexual prejudice toward lesbians. In turn, higher levels of sexual prejudice were expected to predict increased anger and anxiety in response to female–female, but not male–female, relationship behavior.

In summary, the present study advanced the following three hypotheses consistent with a moderated mediation effect:

-

Hypothesis 1

Traditional female gender role beliefs should be associated with increased anger and anxiety, and this effect should not be moderated by video condition.

-

Hypothesis 2

Traditional female gender role beliefs should be associated with higher levels of sexual prejudice toward lesbians.

-

Hypothesis 3

An interactive effect of sexual prejudice and video condition will predict anger and anxiety. Specifically, higher levels of sexual prejudice should predict increased anger and anxiety in response to female–female, but not male–female, relationship behavior.

To test each hypothesis, separate linear regression models were computed in accordance with guidelines put forth by Muller et al. (2005). In the first model (Hypothesis 1), the outcome variable (i.e., change in anger, change in anxiety) was regressed on the predictor (i.e., female gender role beliefs), the moderator (i.e., video), and the female gender role beliefs X video interaction. In the second model (Hypothesis 2), the mediating variable (i.e., sexual prejudice) was regressed on female gender role beliefs, video, and the female gender role beliefs X video interaction. In the third model (Hypothesis 3), change in anger (or anxiety) was regressed on female gender role beliefs, video, the female gender role beliefs X video interaction, sexual prejudice, and the sexual prejudice X video interaction. In order to demonstrate the overarching hypothesis of moderated mediation, the effect of female gender role beliefs must be significant (Model 1), the effect of the female gender role beliefs X video interaction term must not be significant (Model 1), and female gender role beliefs (Model 2) and the sexual prejudice X video interaction (Model 3) must be significant.

Method

Participants

Self-identified heterosexual women (n = 224) between the ages of 18–30 were recruited from the Department of Psychology research participant pool at Georgia State University. Participants responded to an announcement titled “Cultural Differences and Social Attitudes.” From this sample, a heterosexual orientation was determined further via participants’ responses to the Kinsey Heterosexuality-Homosexuality Rating Scale (KRS; Kinsey et al. 1948). As recommended by Savin-Williams (2006), sexual orientation is most reliably assessed when multiple components of sexual orientation are congruent. Moreover, it is suggested that the highest priority be given to indices of sexual arousal rather than self-identification and reports of sexual behavior. Indeed, these latter components of sexual orientation are more susceptible to social context effects, self-report biases, and variable meanings. Thus, among self-identified heterosexual participants, a heterosexual orientation was confirmed by endorsement of exclusive sexual arousal to males (i.e., no reported sexual arousal to females) and sexual experiences that occurred mostly or exclusively with men. Using these criteria, 72 non-heterosexual participants were removed from subsequent data analyses. In addition, two participants experienced equipment malfunctions and one participant reportedly failed to watch the stimulus video. Removing these three women from subsequent data analyses left a final sample of 149 heterosexual women. All participants received partial course credit for their participation. This study was approved by the Georgia State University Institutional Review Board. See Table 1 for sample characteristics.

Experimental Design

The present study had three predictor variables: female gender role beliefs, sexual prejudice, and video exposure. Pertinent literature indicates that artificial dichotomization of quantitative measures may produce numerous negative consequences, including loss of information about individual differences, loss of effect size and statistical power, and loss of measurement reliability (MacCallum et al. 2002). Consequently, female gender role beliefs and sexual prejudice scores were not dichotomized and regression analyses were utilized to analyze these constructs as continuous variables. All participants were randomly assigned to view a video that depicted female–female (n = 69) or male–female (n = 80) relationship activity (see below). The female–female video condition was comprised of 35 African-Americans, 25 Caucasians, three Asian-Americans, and six individuals who identified themselves as from another racial category. The male–female video condition was comprised of 48 African-Americans, 22 Caucasians, seven Asian-Americans, and three individuals who identified themselves as from another racial category. A chi-square analysis did not detect a significant difference in the racial composition of the two video conditions.

Materials

Demographic Form

This self-report form obtained information such as age, self-identified sexual orientation, race, relationship status, years of education, and average family yearly income.

Kinsey Heterosexual-Homosexual Rating Scale (KRS; Kinsey et al. 1948)

A modified version of this scale was used to assess prior sexual arousal and experiences. On this 7-item scale, participants rate their sexual arousal and behavioral experiences from “exclusively heterosexual” to “exclusively homosexual.” In accordance with the previously noted recommendations of Savin-Williams (2006), only participants who endorsed exclusive heterosexual arousal and that “all” or “most” of their behavioral experiences occurred with men were included in the analyses.

Attitudes Toward Women Scale (ATWS; Spence and Hahn 1997)

This 15-item Likert-type scale measures attitudes toward women’s gender roles, responsibilities, and rights. Responses may range from 0 (agree strongly) to 3 (disagree strongly), with lower scores indicating more traditional beliefs regarding the female gender role. Sample items include “Women should worry less about their rights and more about becoming good wives and mothers” and “A woman should not expect to go to exactly the same places or to have quite the same freedom of actions as a man.” In the present sample, average item scores (M = 2.32, SD = .35) were comparable to a meta-analysis of Southern women’s average item scores (M = 2.37) (Spence and Hahn 1997). Previous research indicates internal consistency coefficients for female respondents that exceed .80 (Daugherty and Dambrot 1986; Spence and Helmreich 1978; Spence and Hahn 1997). These findings are consistent with the present sample (α = .77).

Attitudes Toward Lesbian Scale (ATLS; Herek 1988)

This 10-item Likert-type scale measures heterosexuals’ attitudes held specifically about lesbians. Total scores range from 10 (extremely positive attitudes) to 90 (extremely negative attitudes). Sample items include “Female homosexuality is an inferior form of sexuality” and “Lesbians are sick.” The author reported that internal consistency coefficients for this scale typically exceed .85, which was consistent with the present sample (α = .87).

Stimulus Material

Previous research on emotional responses to sexual minorities has employed sexually graphic stimuli as an analogue for real life exposure to gay men or lesbians (e.g., Bernat et al. 2001; Mahaffey et al. 2005). Although results from these studies made significant contributions to this literature, these stimuli possess low ecological validity. Realistically, heterosexual men and women are unlikely to put themselves in situations where they would be exposed to sexually graphic male–male or female–female behavior, respectively. Because of this limitation, it is unclear whether findings from these investigations stem from the essence of same-sex relationship behavior or the graphic sexual nature of the stimuli. To address this limitation and increase the ecological validity of the stimuli, the present study employed more widespread depictions of lesbian and heterosexual behavior. Specifically, participants watched a 160 s color video depicting intimate relationship behavior between a female–female or a male–female couple. Each video portrayed intimate relationship activity (e.g., hand holding, kissing) and concluded in a marriage ceremony. With the exception of public displays of affection, these videos did not depict any explicit sexual contact between these dyads.

Emotional Assessment

Participants’ experience of anger and anxiety was assessed with the Anger-Hostility and Fear subscales, respectively, from the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule—Expanded Form (PANAS-X; Watson and Clark 1994). These subscales were administered in conjunction with the 20-item Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS; Watson et al. 1988). Participants rated the extent to which they experienced each descriptor on a 5-point Likert-type scale from 1 (very slightly) to 5 (extremely). The authors reported internal consistency coefficients for these subscales that exceeded .80. In the present study, alpha reliability coefficients for administrations of both subscales ranged between .76 and .80.

Procedure

Upon arrival to the laboratory, participants were greeted by an experimenter and led to a private experimental room. Participants provided informed consent and were told that the purpose of the experiment was to assess the relation between cultural differences, social attitudes, and relationship behavior. Next, the demographic form, KRS, ATWS, ATLS, and PANAS subscales were administered. Participants then watched one of two stimulus videos (female–female or male–female) on a television monitor located at their desk. The experimenter controlled the video from a DVD player located in the control room. After viewing the video, participants again completed the PANAS subscales. Participants were then fully debriefed, compensated with course credit, and thanked for their participation.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Random group assignment was expected to ensure that experimental groups did not differ on pertinent demographic or dispositional variables. Nonetheless, prior to hypothesis testing, it was necessary to confirm this assumption. As such, a series of one-way ANOVAs were performed with pertinent demographic characteristics, female gender role beliefs, and sexual prejudice as the dependent variables. No significant group differences were found for age (F(1, 148) = .06), years of education (F(1, 148) = 1.72), female gender role beliefs (F(1, 148) = .83), or sexual prejudice (F(1, 148) = .07). As noted above, a chi-square analysis did not detect a significant difference in the racial composition of the two video conditions. Finally, Pearson product-moment correlation coefficients were computed between predictor variables (Table 2). Inspection of the Variance Inflation Factor for these correlations did not reveal a factor greater than five, which suggests that multicollinearity was not a concern.

Regression Analyses

The principal aim of the present investigation was to evaluate a theoretically based pathway to heterosexual women’s experience of negative emotion in response to lesbians. It was hypothesized that traditional female gender role beliefs would be associated with higher levels of sexual prejudice. In turn, higher levels of sexual prejudice were expected to predict increased anger and anxiety in response to female–female, but not male–female, relationship behavior. As reviewed previously, this overarching hypothesis of moderated mediation was tested by computing three regression models (Muller et al. 2005).

Prior to computing regression models, raw scores for female gender role beliefs and sexual prejudice scores were first converted to z-scores. To standardize the categorical variable (i.e., videotape condition), dummy coding was employed. Standardizing these first-order variables automatically centers the values (i.e., deviation scores with a mean of zero) which reduces multicollinearity between interaction terms and their constituent lower-order terms (Aiken and West 1991). Interaction terms were then calculated by obtaining cross-products of pertinent first-order variables. The parameter estimates for interaction terms are reported as unstandardized bs, whereas those for main effects and simple slopes are reported as standardized βs. According to the procedures put forth in Aiken and West (1991), significant interaction terms were interpreted by plotting the effect and testing to determine whether the slopes of the simple regression lines differed significantly from zero. To compute criterion variables (i.e., changes in anger and anxiety), participants’ anger and anxiety scores on the PANAS at baseline were subtracted from their corresponding scores immediately following the stimulus video

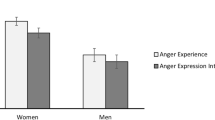

Effects of Female Gender Role Beliefs, Sexual Prejudice, and Video on Change in Anger

The first model was significant, F(3, 145) = 13.24, p < .001, R 2 = .22. Female Gender Role Beliefs (β = −.22, p < .05) and Video (β = −.41, p < .001) were the only significant effects in this model. This indicated that more traditional beliefs about the female gender role and viewing female–female relationship behavior were independently associated with greater increases in anger. Importantly, the relation between female gender role beliefs and anger was not moderated by the type of video (i.e., female–female, male–female) that participants viewed. These findings were consistent with Hypothesis 1.

The second model was also significant, F(3, 145) = 8.99, p < .001, R 2 = .16. Female Gender Role Beliefs (β = −.40, p < .001) was the only significant effect in this model. Consistent with Hypothesis 2, this indicated that more traditional beliefs about the female gender role were associated with higher levels of sexual prejudice and that this relation was not moderated by the type of video that participants viewed.

The third model was significant, F(5, 143) = 10.22, p < .001, R 2 = .26. The Sexual Prejudice X Video interaction term was significant (b = −1.11, p < .01), whereas the previously significant effect of Female Gender Role Beliefs was reduced to a non-significant level (β = −.07, p = n.s.). A plot of this interaction indicated that after viewing the male–female relationship video, the association between sexual prejudice and change in anger was not significant (β = −.04). However, after viewing the female–female relationship video, a significant positive association was detected between these variables (β = .36, p < .001). Consistent with Hypothesis 3, these findings indicated that higher levels of sexual prejudice were associated with greater increases in anger in response to female–female, relative to male–female, relationship behavior (see Fig. 1). Collectively, these results indicated that sexual prejudice mediated the effect of traditional female gender role beliefs on increases in anger in response to female–female, but not male–female, intimate relationship behavior (See Table 3).

Effects of Female Gender Role Beliefs, Sexual Prejudice, and Video on Changes in Anxiety

The first model was not significant, F(3, 145) = 2.11, p < .07, R 2 = .04. The effect of Female Gender Role Beliefs was not significant in this model (β = .03, p = n.s.). Because the first criterion for moderated mediation was not met in this first model (i.e., Hypothesis 1), subsequent regression models are not reported here (see Table 3).

Post-hoc Analyses

Although racial differences were not included in our a priori hypotheses, the diversity of the present sample permitted us to examine whether the observed pattern of findings varied within the two most represented racial groups in our sample (African American and Caucasian women). This opportunity was deemed important because little data exists on racial differences, or lack thereof, in the prediction of anti-lesbian anger or anxiety. Thus, the analytic plan described above was repeated by adding race and all pertinent race interactions (e.g., Female Gender Role Beliefs X Race, Video X Race) as predictors in Models 1, 2, and 3. Because these analyses were repeated only with African American (n = 83) and Caucasian women (n = 47), 19 participants of other racial backgrounds were excluded. Results did not detect any significant interactions involving race. These data suggest that the aforementioned pattern of findings did not vary between African American and Caucasian women in the present sample.

The present investigation utilized relatively stringent criteria to identify a heterosexual sample of women, in that only self-identified heterosexual women who reported exclusive heterosexual arousal to males and sexual experiences that occurred predominantly with males (i.e., infrequent sexual contact with females) were included in the analyses performed above. It may be argued that this sample is not directly comparable to typical undergraduate women. With this in mind, analyses were repeated using less stringent criteria. Specifically, we expanded the inclusion criteria to include self-identified heterosexual women who reported sexual arousal that occurred predominately to males (i.e., infrequent sexual arousal to females) and sexual experiences that occurred mostly with males (i.e., a fair amount of sexual contact with females). This change added 58 participants to the “heterosexual” sample (n = 207). The aforementioned findings for anger and anxiety did not change when analyses were performed with this more inclusive sample.

Discussion

Theoretical and empirical literature based on heterosexual men has established a pathway to anti-gay aggression. Specifically, data indicate that traditional male gender role beliefs give rise to sexual prejudice, which in turn predicts anger in response to gay men (Parrott et al. 2008). Consistent with these data, the threat of being mislabeled as homosexual (Bosson et al. 2005) might constitute the social pressures that facilitate heterosexual men’s strong adherence to the male gender role and, in turn, increase negative emotions in response to gay men. Moreover, research suggests that anger in response to gay men mediates the association between sexual prejudice and anti-gay aggression (Parrott and Peterson 2008). Similar research has found that sexually prejudiced men also experience heightened anxiety in response to gay men. Interestingly, this fear response has been shown to promote anger-related biases in cognitive processing that may underlie subsequent aggression toward gay men (Bernat et al. 2001; Parrott et al. 2006). Collectively, this literature points to anger and anxiety in response to gay men as important emotional determinants of male-perpetrated anti-gay aggression.

Based on this empirically supported model in men, a similar hypothesis was tested in the present sample of women. Specifically, it was hypothesized that traditional female gender role beliefs would be associated with higher levels of sexual prejudice toward lesbians. In turn, higher levels of sexual prejudice were expected to predict increased anger and anxiety in response to female–female, but not male–female, relationship behavior. Results supported the hypothesis for anger but not for anxiety.

In the first step of the analyses for anger, it was established that traditional female gender role beliefs predicted increases in anger in response to the female–female and male–female relationship videos. This relation was not moderated by the type of video that participants viewed. While it was expected that traditionally minded women would experience anger in response to the female–female video, it is less obvious why they reported higher levels of anger in response to the male–female video. Potential explanations include self-reflection by non-married, traditionally minded women prompted by another woman getting married or perceived equality between the male–female couple. Nevertheless, although traditionally minded women reported increased anger in response to both videos, the importance of exposure to lesbian, relative to heterosexual, couples in the elicitation of anger was illustrated in subsequent analyses.

The second step of the analyses revealed that traditional female gender role beliefs were associated with higher levels of sexual prejudice. This relation was not moderated by the type of video that participants viewed. This result is consistent with prior research on the link between traditional gender role beliefs and sexual prejudice in both men and women (Herek 1988; Kite and Whitley 1996; Whitley 2001). The third step of the analyses indicated that sexual prejudice predicted significant increases in anger among heterosexual women who viewed the female–female, but not the male–female, video. In addition, the association between female gender role beliefs and anger was reduced to a non-significant level.

Collectively, these findings are the first to demonstrate a pathway from traditional gender role beliefs to anti-lesbian anger in heterosexual women. Specifically, traditional beliefs about the female gender role appear to give rise to sexual prejudice toward lesbians. In turn, higher levels of sexual prejudice elicit increased anger, but only among women exposed to a lesbian interaction. This finding is generally consistent with research that links traditional male gender role beliefs (Parrott et al. 2008; Parrott and Zeichner 2008) and male sexual prejudice (Bernat et al. 2001; Parrott and Zeichner 2005; Parrott et al. 2006) to increased anger in response to gay men.

Results from the present study suggest that similar processes account for sexually prejudiced men and women’s experience of anger in response to same-sex behavior. Consistent with past research in men (Parrott et al. 2002; Thompson et al. 1985; Shields and Harriman 1984), these results support the idea that socialization pressure to adhere to traditional gender roles produces stronger anti-lesbian attitudes in women. A source of this social pressure may be found in the perceived threat that one will be mislabeled as homosexual (Bosson et al. 2005). Indeed, prior research has shown that the anticipation of being misclassified as lesbian was positively associated with heterosexual women’s self-report of negative affect during gender role violations (Bosson et al. 2006). While it is recognized that this effect may be more pronounced in men relative to women, our data indicate that the consequences of this effect in women cannot be disregarded. Indeed, research indicates that heterosexual men’s anger in response to gay men predicts subsequent aggression toward gay men (Bernat et al. 2001; Parrott and Peterson 2008; Parrott and Zeichner 2005). Thus, future research is needed to determine whether heterosexual women’s anger in response to lesbians similarly predicts aggression toward lesbians or other sexual minorities.

The present data did not support female gender role beliefs or sexual prejudice as significant determinants of increased anxiety in response to lesbians. This outcome may stem from a ceiling effect for our measure of female gender role beliefs. Over the past 30 years, women have endorsed increasingly more liberal beliefs about the female gender role on the Attitudes Toward Women Scale (Spence and Hahn 1997). Consistent with this trend, women in the present sample endorsed relatively liberal female gender role beliefs. Even so, the present findings highlight a potentially important difference in men and women’s emotional responses to gay men and lesbians, respectively. As previously noted, recent studies with men indicate a positive link between sexual prejudice and anti-gay anxiety (Bernat et al. 2001; Parrott and Zeichner 2005), potentially because of the threat that gay men represent to heterosexual sexuality (Herek 1986, 1988). In addition, the experience of anxiety in response to gay men has been shown to facilitate an anger-related cognitive bias in sexually prejudiced men (Parrott et al. 2006). While this cognitive bias has been posited to underlie anti-gay aggression, research has not yet confirmed this hypothesis. Nevertheless, the lack of a relation between female sexual prejudice and anti-lesbian anxiety may portend the absence of an associated anger-related cognitive bias because, unlike heterosexual men, heterosexual women perceive lesbians as a minimal threat to their sexuality. Though speculative, it is possible that these differences in cognition may account for the disproportionate number of male, relative to female, perpetrators of aggression toward sexual minorities (NCAVP 2007). Until these questions are answered, implications of the present findings on female-perpetrated anti-lesbian aggression should be interpreted with caution.

In summary, the present investigation demonstrated in a sample of heterosexual women that sexual prejudice accounted for the relation between traditional female gender role beliefs and anger, but not anxiety, in response to lesbians. These differences in emotional responding may explain observed gender differences in rates of violence against sexual minorities. However, it is worth noting that other individual or situational factors may also influence heterosexual women’s negative emotional responses to lesbians and engagement in anti-lesbian aggression. For example, factors other than sexual prejudice (e.g., peer dynamics, thrill seeking) have also been linked to anti-gay and anti-lesbian emotional and behavioral responses (Franklin 1998, 2000; Parrott and Peterson 2008). It should be stressed that results from this study do not necessarily generalize to these other motivations for aggression toward sexual minorities. As such, future research with men and women is sorely needed to investigate the extent to which these other motivations might facilitate anger and aggression toward sexual minorities. In addition, the present sample was relatively diverse, with 56% of participants identifying as African-American. While the diversity of the sample may be viewed as a strength, it should also be noted that sexual prejudice is believed to be more prevalent in the African-American community relative to society at large (Brandt 1999). This view is supported by recent data (Lewis 2003). Thus, future research is needed to examine whether the present findings are maintained within specific racial or ethnic groups or, alternatively, whether race or ethnicity moderate these effects.

Although the current study sheds new light on determinants of anti-lesbian anger in heterosexual women, several limitations merit discussion. First, the present study did not assess participants’ aggression toward lesbians. While results provide a basis to direct this work, it is important for future research to establish a link between heterosexual women’s anti-lesbian attitudes, anti-lesbian emotional responses, and acts of anti-lesbian aggression. Second, despite the racial diversity of the present sample, it was nonetheless comprised exclusively of female undergraduate students. Inclusion of non-university participants (e.g., known anti-gay or anti-lesbian offenders, high school students) would have increased the external validity of these findings. Indeed, in considering the mean level of sexual prejudice obtained in the present sample, it can be argued that truly “pathological” levels of sexual prejudice were not adequately represented. Third, although the video manipulation appeared to be effective, incorporating exposures to female homosexuality (e.g., use of a confederate, popular media reports) that are more personally relevant to participants might increase the external validity of future research. Indeed, such efforts will bridge the gap between laboratory- and survey-based literatures. Finally, the present study did not assess participants’ attitudes or emotional responses toward gay men. This limitation highlights the need for researchers to examine men and women’s attitudes and affective responses toward opposite sex, sexual minority targets.

It is recognized that women do not perpetrate the majority of hate crimes toward sexual minorities. Nevertheless, women do represent approximately 15% of identified perpetrators of aggression toward sexual minorities (NCAVP 2007) and may engage in other forms of bias-motivated aggression toward sexual minorities that go unreported (e.g., verbal aggression, property damage). Indeed, aggression is a multifaceted construct that may be expressed in a variety of forms and for numerous reasons (Parrott and Giancola 2007). Therefore, it is important for future research to carefully examine pathways to various forms of female-perpetrated anti-lesbian aggression. The present study represents a first step in this regard by supporting one theoretically based route to women’s anti-lesbian anger and, perhaps, aggression. By continuing to elucidate this and other pathways, researchers will be better equipped to develop intervention programs with the goal of decreasing violence toward sexual minorities.

References

Aiken, L., & West, S. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park: Sage.

Berkowitz, L. (1990). On the formation and regulation of anger and aggression: A cognitive neoassociationistic analysis. American Psychologist, 45, 494–503.

Bernat, J. A., Calhoun, K. S., Adams, H. E., & Zeichner, A. (2001). Homophobia and physical aggression toward homosexual and heterosexual individuals. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 110, 179–187.

Bosson, J. K., Prewitt-Freilino, J. L., & Taylor, J. N. (2005). Role rigidity: A problem of identity misclassification? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89, 552–565.

Bosson, J. K., Taylor, J. N., & Prewitt-Freilino, J. L. (2006). Gender role violations and identity misclassification: The roles of audience and actor variables. Sex Roles, 55, 13–24.

Brandt, E. (1999). Dangerous liaisons: Blacks, gays, and the struggle for equality. New York: New Press.

Daugherty, C. G., & Dambrot, F. H. (1986). Reliability of the attitudes toward women scale. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 46, 449–453.

Federal Bureau of Investigation (2006). Uniform crime reports: Hate crime statistics, 2005. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

Franklin, K. (1998). Unassuming motivations: Contextualizing the narratives of antigay assailants. In G. M. Herek (Ed.) Stigma and sexual orientation: Understanding prejudice against lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals (pp. 1–23). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Franklin, K. (2000). Antigay behaviors among young adults. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 15, 339–362.

Gentry, C. S. (1987). Social distance regarding male and female homosexuals. Journal of Social Psychology, 127, 199–208.

Hamner, K. M. (1990). Gay-bashing: A social identity analysis of violence against lesbians and gay men. In G. M. Herek, & K. T. Berrill (Eds.) Hate crimes: Confronting violence against lesbians and gay men (pp. 179–190). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Herek, G. M. (1984). Beyond “homophobia”: A social psychological perspective on attitudes toward lesbians and gay men. Journal of Homosexuality, 10, 39–51.

Herek, G. M. (1986). On heterosexual masculinity: Some psychical consequences of the social construction of gender and sexuality. American Behavioral Scientists, 29, 563–577.

Herek, G. M. (1988). Heterosexuals’ attitudes toward lesbians and gay men: Correlates and gender differences. The Journal of Sex Research, 25, 451–477.

Herek, G. M. (2002). Heterosexuals’ attitudes toward bisexual men and women in the United States. The Journal of Sex Research, 39, 264–274.

Herek, G. M., & Capitanio, J. P. (1995). Black heterosexuals’ attitudes toward lesbians and gay men in the United States. The Journal of Sex Research, 32, 95–105.

Herek, G. M., & Capitanio, J. P. (1996). “Some of my best friends”: Intergroup contact, concealable stigma, and heterosexuals’ attitudes toward gay men and lesbians. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 22, 412–424.

Hort, B. E., Fagot, B. I., & Leinbach, M. D. (1990). Are people’s notions of maleness more stereotypically framed than their notions of femaleness? Sex Roles, 23, 197–212.

Kimmel, M. S. (1997). Masculinity as homophobia: Fear, shame, and silence in the construction of gender identity. In M. M. Gergen, & S. N. Davis (Eds.) Toward a new psychology of gender (pp. 223–242). New York: Routledge.

Kinsey, A. C., Pomeroy, W. B., & Martin, C. E. (1948). Sexual behavior in the human male. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders.

Kite, M. E. (1984). Sex differences in attitudes toward homosexuals: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Homosexuality, 10, 69–81.

Kite, M. E. (1994). When perceptions meet reality: Individual differences in reactions to lesbians and gay men. In B. Greene, & G. M. Herek (Eds.) Contemporary perspectives on gay and lesbian psychology (pp. 25–33). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Kite, M. E., & Whitley, B. E. (1996). Sex differences in attitudes toward homosexual persons, behavior, and civil rights: A meta-analysis. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 22, 336–353.

Kite, M. E., & Whitley, B. E. (1998). Do heterosexual women and men differ in their attitudes toward homosexuality? A conceptual and methodological analysis. In G. M. Herek (Ed.) Stigma and sexual orientation: Understanding prejudice against lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals (pp. 39–61). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Kite, M. E., & Whitley Jr., B. E. (2003). Do heterosexual women and men differ in their attitudes toward homosexuality? A conceptual and methodological analysis. In L. Garnets, & D. Kimmel (Eds.) Psychological perspectives on lesbian, gay, and bisexual experiences (pp. 165–187, 2nd ed.). New York: Columbia University Press.

Lewis, G. B. (2003). Black-white differences in attitudes toward homosexuality and gay rights. Public Opinion Quarterly, 67, 59–78.

Lim, V. K. (2002). Gender differences and attitudes towards homosexuality. Journal of Homosexuality, 43, 85–97.

Louderback, L. A., & Whitley, B. E. (1997). Perceived erotic value of homosexuality and sex-role attitudes as mediators of sex differences in heterosexual college students’ attitudes toward lesbians and gay men. Journal of Sex Research, 34, 175–182.

MacCallum, R. C., Zhang, S., Preacher, K. J., & Rucker, D. D. (2002). On the practice of dichotomization of quantitative variables. Psychological Methods, 7, 19–40.

Mahaffey, A. L., Bryan, A., & Hutchison, K. E. (2005). Sex differences in affective responses to homoerotic stimuli: Evidence for an unconscious bias among heterosexual men, but not heterosexual women. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 34, 537–545.

Muller, D., Judd, C. M., & Yzerbyt, V. Y. (2005). When moderation is mediated and mediation is moderated. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89, 852–863.

National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs (2007). Anti-lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender violence in 2006. New York: NCAVP.

Parrott, D. J., Adams, H. E., & Zeichner, A. (2002). Homophobia: Personality and attitudinal correlates. Personality and Individual Differences, 32, 1269–1278.

Parrott, D. J., & Giancola, P. R. (2007). Addressing “the criterion problem” in the assessment of aggressive behavior: Development of a new taxonomic system. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 12, 280–299.

Parrott, D. J., & Peterson, J. L. (2008). What motivates hate crimes based on sexual orientation?: Mediating effects of anger on antigay aggression. Aggressive Behavior.

Parrott, D. J., Peterson, J. L., Vincent, W., Bakeman, R. (2008). Correlates of anger in response to gay men: Effects of male gender role beliefs, sexual prejudice and masculine gender role stress. Psychology of Men and Masculinity.

Parrott, D. J., & Zeichner, A. (2005). Effects of sexual prejudice and anger on physical aggression toward gay and heterosexual men. Psychology of Men and Masculinity, 6, 3–17.

Parrott, D.J., & Zeichner, A. (2008). Determinants of anger and physical aggression based on sexual orientation: An experimental examination of hypermasculinity and exposure to male gender role violations. Archives of Sexual Behavior.

Parrott, D. J., Zeichner, A., & Hoover, R. (2006). Sexual prejudice and anger network activation: The mediating role of negative affect. Aggressive Behavior, 32, 7–16.

Patel, S., Long, T. E., McCammon, S. L., & Wuensch, K. L. (1995). Personality and emotional correlates of self-reported antigay behaviors. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 10, 354–366.

Roderick, T., McCammon, S. L., Long, T. E., & Allred, L. J. (1998). Behavioral aspects of homonegativity. Journal of Homosexuality, 36, 79–88.

Savin-Williams, R. C. (2006). Who’s gay? Does it matter? Psychological Science, 15, 40–44.

Shields, S. A., & Harriman, R. E. (1984). Fear of male homosexuality: Cardiac responses of low and high homonegative males. Journal of Homosexuality, 10, 53–67.

Spence, J. T., & Hahn, E. D. (1997). The attitudes toward women scale and attitude change in college students. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21, 17–34.

Spence, J. T., & Helmreich, R. L. (1978). Masculinity and femininity: Their psychological dimensions, correlates and antecedents. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Takács, J. (2006). Social exclusion of young lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender (LGBT) people in Europe. Brussels, Belgium: ILGA Europe.

Thompson, E. H., Grisanti, C., & Pleck, J. H. (1985). Attitudes toward the male role and their correlates. Sex Roles, 13, 413–427.

Watson, D., & Clark, L. A. (1994). Manual for the positive and negative affect schedule (expanded form). Unpublished manuscript, University of Iowa, Iowa City.

Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 1063–1070.

Whitley, B. E. (1987). The relationship of sex-role orientation to heterosexuals’ attitudes toward homosexuals. Sex Roles, 17, 103–113.

Whitley, B. E. (1990). The relationship of heterosexuals’ attributions for the causes of homosexuality to attitudes toward lesbians and gay men. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 16, 369–377.

Whitley, B. E. (2001). Gender-role variables and attitudes toward homosexuality. Sex Roles, 45, 691–721.

Whitley, B. E., & Kite, M. E. (1995). Sex differences in attitudes toward homosexuality: A comment on Oliver and Hyde (1993). Psychological Bulletin, 117, 146–154.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This research was supported by grant R01-AA-015445 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. We thank Bronwyn Dowling and Lauren Walther for their assistance with data collection.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Parrott, D.J., Gallagher, K.E. What Accounts for Heterosexual Women’s Negative Emotional Responses to Lesbians?: Examination of Traditional Gender Role Beliefs and Sexual Prejudice. Sex Roles 59, 229–239 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-008-9436-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-008-9436-0