Abstract

This study reports on the psychometric properties of the Femininity Ideology Scale (FIS) from the responses of 407 undergraduate participants in the USA. Factor analysis supported the five factor structure. Cronbach alpha coefficients of the factors and total scale were adequate. Support for discriminant validity was found after examining the relationship between the FIS and the Bem Sex Role Inventory, which measures feminine traits. Support for convergent validity was found after examining, first, with the entire sample, the relationships between the FIS and the Male Role Norm Inventory, and second, with the female sample, the relationships between the FIS and the Feminist Identity Development Scale. We also found that FIS scores vary in relationship to the social contextual variables of race/ethnicity and sex.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Gender is a multidimensional construct (Spence and Buckner 2000; Marsh and Bryne 1991; Spence 1993). Dimensions include: gender-typed personality traits (Bem 1974, 1981), gender related interests (Lippa 2005), global sex role behaviors (Orlofsky and O’Heron 1987), masculinity ideology (Levant and Fischer 1998), gender role conflict (O’Neil et al. 1986), gender role stress (Eisler 1995), and gender role conformity (Mahalik et al. 2005). This study presents data on a new scale which measures femininity ideology, the Femininity Ideology Scale (FIS), a separate and unique construct from those measured by the abovementioned measurements.

Gender ideology refers to an individual’s internalization of cultural beliefs regarding gender roles (Levant 1996; Pleck 1995; Thompson and Pleck 1995). Research has found that the socialization of children into, and the adherence of adults to, traditional gender role norms, have negative psychological consequences by creating gender role strain (Pleck 1981, 1995). For men, factors found to be associated with the endorsement of traditional masculinity ideology include low self-esteem (Davis 1987), difficulties in intimacy (Sharpe and Heppner 1991), anxiety (Davis 1987), alexithymia (Levant et al. 2003), and depression (Good and Mintz 1990). Furthermore, empirical investigations have found men to generally endorse traditional masculinity ideology to a greater extent than their female counterparts, because traditional ideologies serve to uphold gender-based power structures, which ultimately benefit men (Levant 1996). Given the research on the association between the endorsement of traditional masculinity ideology and negative psychological consequences and also the sex differences in endorsements of masculinity ideology, it is important to study the correlates of traditional femininity ideology. However there is a lack of instruments to measure general femininity ideology in adult women.

Tolman and Porche (2000) developed the Adolescent Femininity Ideology Scale (AFIS), which measures the degree to which adolescent girls have internalized or resisted two features of traditional femininity: bringing an inauthentic self into relationships and having an objectified relationship with their bodies. Though this scale evaluates two aspects of traditional femininity ideology among adolescent girls, it differs from the FIS in that it is not a general measure of traditional femininity ideology, and has not been validated with adult women.

The Conformity to Feminine Norms Inventory (CFNI; Mahalik et al. 2005) is a related measure, which measures both conformity (as defined by self-reported behaviors, feelings, and thoughts that are consistent with traditional feminine norms) and nonconformity. Whereas a scale evaluating femininity ideology measures participants’ endorsements of beliefs about how women, in general, should act, the CFNI differs by examining the degree to which an individual woman self-reports that her own behaviors, feelings, and thoughts conform to societal rules and expectations about femininity (Mahalik et al. 2005).

Philpot, when she was a professor at the Florida Institute of Technology, developed a Femininity Ideology Scale (FIS) for adult women, and supervised a group of Masters Degree students’ theses, which studied various aspects of the FIS (Franklin 1998; Gronemeyer 1998; Lehman 2000; Omar 1998). There never was a peer-reviewed publication of this effort.

To develop the FIS, Philpot and her students generated 166 statements regarding traditional feminine norms, which focused on themes such as body image, care-taking, sexuality, family, religion, marriage, passivity, dependency and career. Responses to these 166 statements by 292 male and female participants were analyzed using principle components analysis with Varimax rotation (Lehman 2000). A five-factor solution was specified and items that had factor loadings greater than .45 on a given factor and did not load strongly on another factor were selected. The final version of the FIS is a 45-item, empirically derived instrument consisting of normative statements to which participants indicate their degree of agreement/disagreement on 5-point Likert-type scales. Higher scores on the scales indicated endorsements of traditional femininity ideology. The five factors were labeled Stereotypic Image and Activities, Dependence/Deference, Purity, Caretaking, and Emotionality. It should be noted, however, that this original statistical procedure failed to meet the requisite 5:1 case/item ratio (Myers and Well 1995), and thus needs to be replicated.

The five factors that emerged represent several dimensions of traditional femininity ideals. Items found in Stereotypic Image and Activities suggest that women should maintain a particular physical appearance and image that is consistent with thin body ideals. In Dependency/Deference, items reflect the notion that women should play dependent and deferent roles in relation to their husbands. Within Purity, items demonstrate a chaste ideal and reflect the ways in which women are socialized to take on passive sexual roles. Items found in Caretaking illustrate feminine ideals that motherhood should be considered women’s ultimate fulfillment. Finally, within Emotionality, items reflect the notion that women should have an emotional affinity for domestic related work and may be sensitive. Items can be found in Table 1.

Lehman (2000) found that the factors had high internal consistency, providing evidence of reliability (Lehman 2000). Lehman assessed discriminant validity by examining the correlations between the FIS total score and both the Personal Attributes Questionnaire (PAQ; Spence and Helmreich 1978) and Bem Sex Role Inventory (BSRI; Bem 1974), measures which are theoretically distinct from the FIS, and which measure desirable and stereotypical feminine personality traits thought to be essential to normal personality development rather than femininity ideology (Lehman 2000). Lehman assessed the discriminant validity of the FIS separately for men and women. He hypothesized that, for men, their FIS total score would not be significantly correlated with their score on either the BSRI or PAQ masculinity scales, or that, for women, their FIS total score would not be significantly correlated with their score on either the BSRI or PAQ femininity scales. The results supported these hypotheses.

Lehman also found significant high positive correlations between the FIS total score and the MRNI total score, which provides support for the scale’s convergent validity. Although the MRNI is focused on male role norms, it is similar to the FIS because it measures gender ideology (Lehman 2000; Pleck 1981).

Several other Masters theses explored the endorsement of traditional femininity ideology using the FIS among diverse populations. In a study comparing the responses of African-American and European-American women, African-American women endorsed traditional femininity ideology to a lesser extent than did European-Americans on the factor, Purity (Franklin 1998). A significant difference between never married and married individuals on the factor, Purity, was found by Omar (1998), with the never married participants endorsing the factor in a more traditional fashion. In a study comparing the responses of various age groups, significant differences were found between the “under 26” and “the over 55” age groups on two factors: Purity and Caretaking. The younger age group endorsed traditional femininity to a greater extent than did the older age group (Gronemeyer 1998).

The present study was designed to further evaluate the factor structure, reliability, convergent and discriminant validity, and social contextual variation of the FIS. We first performed a principle components analysis to assess the support for the five factor structure. Next, we assessed reliability by computing Cronbach alpha coefficients. To evaluate discriminant validity, the FIS was compared to the BSRI. As noted above, the BSRI is a measure of gender which is theoretically distinct from the FIS, arising from what Pleck (1981, 1995) has termed the “Gender Role Identity Paradigm”; furthermore it measures desirable and stereotypical feminine personality traits thought to be essential to normal personality development rather than traditional femininity ideology. Hence we would predict low correlations between the BSRI and the FIS. For the women, we compared their FIS scores with their BSRI Femininity scores. For the men, we theorized that the most relevant comparison would be the degree to which they self-describe as stereotypically masculine (their BSRI Masculinity scores) and their endorsement of traditional femininity ideology (which reflects their view of how women should comport themselves), both being measures of traditional views. To evaluate convergent validity, the FIS was compared to the MRNI and the Feminist Identity Development Scale (FIDS; Bargad and Hyde 1991), measures which are theoretically congruent with the FIS, arising out of the Gender Role Strain Paradigm and Feminist Psychology. As previously noted, the MRNI is a measure of masculinity ideology. We administered the MRNI to both sexes since both sexes have views about the norms for men’s roles. The FIDS is theoretically congruent with the FIS, with some FIDS scales (reflecting an individual’s lack of sense of feminist identity) expected to be positively correlated with the endorsement of traditional femininity ideology, and others (reflecting an individual’s sense of feminist identity) expected to be negatively correlated with the endorsement of traditional femininity ideology. The FIDS is a scale that is written only for women; hence we administered it only to the women.

We hypothesized that the principle components analysis will provide some support for (but not definitively test) the five-factor structure of the FIS, that the FIS and its factors will have adequate reliability (defined as Cronbach alphas over .70), that support will be found for discriminant validity (defined as low correlations with the BSRI), and that support will be found for convergent validity (defined as strong correlations with the MRNI and the FIDS). Finally, we predict that men will endorse traditional femininity ideology to a greater extent that will women, and that racial and ethnic minorities will endorse traditional femininity ideology to a greater extent that will European Americans.

Method

Participants

A total of 407 undergraduate students (192 men, 210 women and 5 sex not reported) participated in the research as one of several options to fulfill a course requirement for their General Psychology course. Of the 407 participants, 89.7% were between the ages of 17 and 20 years old, 7.5% were between the ages of 21 and 24 years old, and 1.1% were between the ages of 25 and 45 years old. Five participants did not answer this question.

Sexual orientation was measured on a scale of 1 to 7 (1 being totally attracted to the same sex and 7 being totally attracted to the other sex). Of the sample of 407 students, 3.4% (N = 14) identified themselves as totally attracted to the same sex, 6% of students (N = 25) identified themselves between the two ends of the continuum, and 89.2% (N = 363) identified themselves as totally attracted to the other sex. Five participants did not answer this question.

Race/Ethnicity categories were divided into European-American, African American, Latina/o, Asian American, and other. European-American students comprised 81.3% (N = 331) of the sample, African Americans comprised 10.1% (N = 41), Latina/o’s comprised 2.5% (N = 10), and Asian Americans comprised 2.5% (N = 10). Those students that identified as other comprised 2.5% (N = 10) of the sample. Five participants did not answer this question.

Married students comprised 3.9% (N = 16) of the sample, single students 56.3% (N = 229), divorced students .5% (N = 2), and seriously dating students comprised 38.1% (N = 155). Five participants did not answer this question.

Students whose parents earned an income under 20,000 dollars comprised 6.1% (N = 25) of the sample, earnings between $20,001 and $40,000 comprised 11.3% (N = 46), earnings between $40,001 and $60,000 comprised 14.7% (N = 60), earnings between $60,001 and $80,000 comprised 15.5% (N = 63), earnings between $80,001 and $100,000 comprised 20.4% (N = 83), and earnings over 100,000 dollars comprised 28.0% (N = 114). Sixteen participants did not answer this question.

In the sample, 1% (N = 4) identified themselves as lower class, 6.6% (N = 27) identified themselves as lower middle class, 42.3% (N = 172) identified themselves as middle class, 43.2% (N = 176) identified themselves as upper middle class, and 4.9% (N = 20) identified themselves as upper class. Eight participants did not answer this question.

Procedure

In accordance with the requirements for research on human participants, informed consent was obtained. The FIS was administered to all participants along with the MRNI and the BSRI. The female participants were also administered the FIDS. The FIS was always presented first. The other three measures were randomly ordered following the FIS. A page requesting demographic information was always included last. Participants were reminded that the results would be kept confidential.

Measure

Femininity Ideology Scale

The Femininity Ideology Scale (FIS; Lehman 2000) is designed to assess the degree to which respondents endorse traditional femininity ideology (beliefs about how women should act). The measure contains 45 normative statements to which participants indicate their agreement or disagreement on a 5-point-Likert-type scale, where a score of 1 would represent strong disagreement with traditional norms and a score of 5 would represent strong agreement with traditional norms. There are five factors derived from a principle components analysis (Lehman 2000). For the current study, the number of items for each factor and alphas were: Stereotypic Image and Activities, 11, .89; Dependence/Deference, 10, .83; Purity, 9, .85; Caretaking, 7, .80; and Emotionality, 5, .82. For the total scale, the alpha was .93. To obtain factor scores, first compute a raw score by adding up the scores on the items for that subscale and then divide the raw score by the number of items for that subscale. To obtain the Total Traditional Score, add up the raw scores on the five traditional factors and divide by 45.

Bem Sex Role Inventory

The Bem Sex Role Inventory (BSRI; Bem 1974) was used to assess discriminant validity in this study. The BSRI is a 60-item instrument measuring personality traits associated with men and women, using a 7 point-Likert scale where a score of 1 would represent never or almost never true and a score of 7 would represent almost always true. Internal consistency is assessed separately for males and females for both the F score (expressivity) and the M score (instrumentality; Bem 1974). For the current study, the number of items for each subscale and alphas were: F score: items = 20, female alpha = .84, males alpha = .82; M score: items = 20, female alpha = .90, male alpha = .88.

Male Role Norms Inventory-49

There are several versions of the Male Role Norms Inventory (MRNI; Levant et al. 1992; Levant and Richmond 2007). This study used the MRNI-49 (Berger et al. 2005). The MRNI-49, developed to measure traditional masculinity ideology, consists of normative statements to which subjects indicate their degree of agreement/disagreement on 7-point Likert-type scales, where a score of 1 would represent strong disagreement with traditional norms and a score of 7 would represent strong agreement with traditional norms. The items are grouped into seven theoretically derived subscales. The test as a whole is a Total Traditional Masculinity Ideology Scale. The number of items for each subscale and the total scale and alphas for this study were: Avoidance of Femininity 7, .88; Fear and Hatred of Homosexuals 8, .87; Self-Reliance 7, .73; Aggression 5, .77; Achievement/Status 7, .82; Non-Relational Attitudes Toward Sex 8, .76; Restrictive Emotionality 7, .85; and Total Traditional Masculinity Ideology 49, .96. Data supporting the discriminant and convergent validity of the MRNI were reported by Levant and Fischer (1998).

Feminist Identity Development Scale

The Feminist Identity Development Scale (FIDS; Bargad and Hyde 1991) is a 39-item instrument consisting of closed questions to which participants indicate their agreement/disagreement on a 5-point-Likert-type scale where a score of 1 would represent strongly disagree and a score of 5 would represent strongly agree. A factor and reliability analysis revealed five subscales that are consistent with the five stages of this feminist identity development model. Subscale one, Passive Acceptance (e.g., “I think that most women will feel fulfilled being a wife and mother”), consists of 12 items and yielded an alpha coefficient in this study of .82. Subscale two, Revelation (e.g., “I am angry that I have let men take advantage of me”), consists of seven items and yielded an alpha coefficient of .72. Subscale three, Embeddedness-Emanation (e.g., “Being a part of a woman’s community is important to me”), consists of seven items and yielded an alpha coefficient of .84. Subscale four, Synthesis (e.g., “I feel that some men are sensitive to women’s issues”), consists of five items and yielded an alpha coefficient of .70. Lastly, subscale five, Active Commitment (e.g., “I want to work to improve women’s status”), is made up of eight items and yielded an alpha coefficient of .77.

Results

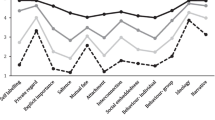

Descriptive data on how male and female participants responded to the each of the measures is presented in Table 1. As can be seen, significant sex differences were found on all subscales, except for two subscales within the Femininity Ideology Scale. These subscales were Caretaking and Emotionality.

The 45-items of the Femininity Ideology scale were subjected to principal components analysis. Prior to the analysis, the suitability of data for factor analysis was assessed. Inspection of the correlation matrix revealed the presence of many coefficients of .45 and above, which meets the assumption that the data are suitable for factor analysis. The Kaiser–Meyer–Oklin value was .86, which exceeds the suggested value of .6 (Kaiser 1974). The Barlett’s Test of Sphericity (Bartlett 1954) was statistically significant, again further supporting the factorability of the correlation matrix.

Principal components analysis revealed the presence of five components with eigen values exceeding 1.5, accounting for 11.46%, 10.80%, 10.40%, 8.26% of the variance, and 7.60% of the variance, respectively. The total variance accounted for was 50.39. Loadings above .40 were considered the minimum loading allowable and no items were removed because of cross-loading problems. Variables that loaded up to .32 on a second component would have been removed had there been any. An inspection of the scree plot revealed a break after the fifth component. Using Catell’s (1966) scree test, it was decided to retain five components for further investigation. Thus we retained components with eigen values exceeding 1.5. We are aware that the convention is to use a cut-off of eigen values exceeding 1.0, but this fit our data better.

To aid in the interpretation of these components, Varimax rotation was performed. As demonstrated in Table 2, five components showed a number of strong loadings. These components are the same as Stereotypic Image and Activities, Dependency/Deference, Purity, Caretaking, and Emotionality found by Philpot and students, thus providing additional support (but not definitive testing) for that component structure, as hypothesized. Though we utilized the five component model in the remaining analyses, it should be noted that the principal component analysis is, in fact, exploratory and does not test that five factors are present.

Evaluation of internal consistency for the FIS factors and the Total Traditional Femininity Ideology scale yielded Cronbach alphas above .70, which is the conventional cutoff score used in previous gender ideology research. For the women only, the Cronbach alphas were Stereotypic Image and Activities (.79), Dependency/Deference (.76), Purity (.85), Caretaking (.80), Emotionality (.81), and Total Traditional Femininity (.92). For the men only, the Cronbach alphas were Stereotypic Image and Activities (.84), Dependency/Deference (.85), Purity (.84), Caretaking (.72), Emotionality (.79), and Total Traditional Femininity (.93). Hence, as hypothesized, the FIS and its factors have adequate reliability.

To examine the relationship between the FIS factors, we calculated Pearson correlation coefficients for factors and the total scale. As shown in Table 3, the coefficients for the correlations between factors Stereotypic Image and Activities, Dependency, Purity, Caring, and Emotionality range from .31–.60. Each factor correlated more highly with the FIS total score than with the other factors, ranging from .75–.83. This pattern of results suggests that the factors measure somewhat different aspects of the same broad construct.

To evaluate discriminant validity, we calculated the correlation coefficients of the FIS and its factors with the BSRI. The FIS (Total Traditional Scale) was not significantly related to the BSRI (for females, r = .07 with the F, or Femininity Scale; for males, r = .06 with the M, or Masculinity Scale). Subsequent analyses demonstrated that, for the male participants, all FIS factors were not related to the Masculinity Scale on the BSRI. For the female participants, the FIS factor, Caretaking, was significantly but modestly related to the Femininity Scale on the BSRI (r = .20, p < .01). For the female participants, all other FIS factors were not significantly related to the Femininity Score on the BSRI. Hence, as hypothesized, support has been found for discriminant validity of the FIS.

To evaluate convergent validity, first, correlations of the FIS and its factors with the MRNI-49 total scale and its subscales were examined using both men and women in the sample. The FIS Total Traditional Femininity Score was strongly correlated with the MRNI-49 Total Traditional Scale (for the women, r = .69; p < .01; for the men, r = .64; p < .01). Furthermore, an analysis of the pattern of factor-subscale correlations revealed that only one of the FIS factors did not correlate significantly with all of the MRNI-49 subscales. The FIS factor Dependency/Deference did not correlate with the MRNI subscale Aggression for men. Pearson correlation coefficients ranged from .14 to .65, as shown in Table 4. Second, correlations of the FIS Total Traditional Score with the FIDS subscales were examined for the women only. Consistent with our hypotheses, the FIS total score was significantly positively correlated with the FIDS Passive Acceptance Stage, Stage 1 (r = .37, p < .001) and the FIDS Revelation Stage, Stage 2 (r = .14, p < 001). The FIS total score was significantly negatively correlated with the FIDS Active Commitment Stage, Stage 5 (r = .16, p < .001). Table 5 shows the relationship between the FIS factors and the FIDS stages, which follows the pattern of correlations between the FIS total score and the FIDS subscales, and supports the hypotheses. Hence, as hypothesized, support has been found for convergent validity of the FIS.

To assess the extent to which the endorsement of traditional femininity ideology as measured by the FIS varies in relationship to the social contextual variables of race/ethnicity and sex, we performed a series of analyses of covariance. Prior studies of gender ideology, which have examined how race and gender affect endorsements of ideology have also found that demographic variables other than gender and race/ethnicity tend to be correlated with the ideology measure, and that a clearer picture of the gender and race/ethnicity differences emerge when their associations with ideology are partialed out via an ANCOVA procedure. To identify the covariates, we first calculated the Pearson correlation coefficients of the demographic variables other than race/ethnicity and sex (e.g., age, relationship status, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, and income) with the FIS factors and the Total Traditional Scale. The demographic variables that correlated with the FIS factors and the Total Traditional Scale were relationship status, sexual orientation, and income (the Pearson correlation coefficients for the Total Scale, were, respectively −.22, .10, −.14). The data were then analyzed using a 4 (race/ethnicity) × 2 (sex) factorial analysis of covariance, with the FIS Total Traditional Scale as the dependent variable and the demographic variables that were correlated with the FIS Total Traditional Scale (relationship status, sexual orientation, and income) as covariates. The main effect of sex was significant—F(1, 358) = 12.44, p < .01. The main effect of race/ethnicity was significant—F(4, 370) = 2.56, p < .05. The interaction between race/ethnicity and sex was not significant—F(4, 358) = 0.23, p = .92.

Sex has a larger effect size than race/ethnicity. Using the Total Traditional scale, the partial eta squared (portion of the variance of the Total Traditional score accounted by the specific independent variable) for sex was .04 and for race/ethnicity was .02, both of which are small effect sizes (Cohen 1977).

Univariate analyses (4 × 2 factorial ANCOVAs) performed separately for the main effect of sex resulted in significant F values on the factors Stereotypic Image and Activities, Dependency and Purity, with males endorsing the factors Stereotypic Image and Activities, Dependency and Purity in a more traditional direction than females. These results are displayed in Table 1. Hence, as hypothesized, men have been found to endorse traditional femininity ideology to a greater extent that do women.

Univariate analyses (4 × 2 factorial ANCOVAs) performed separately for the main effect of race/ethnicity resulted in significant F values on the factors Stereotypic Image and Activities, Dependency, Emotionality, and the Total Traditional Score as shown in Table 6. Because the sample sizes of the non-European American groups were so small we did not attempt to further determine the significance of the differences between these means using post hoc tests. Thus we could not test the hypothesis that racial and ethnic minorities will endorse traditional femininity ideology to a greater extent that will European Americans.

Discussion

The hypotheses were supported. Principle components analysis provides support (but does not definitively test) Lehman’s (2000) five factor solution for the FIS. Results also demonstrate that the FIS has adequate reliability, discriminant and convergent validity, and that the factors are moderately correlated with each other. The FIS factors correlated more highly with the FIS total score, suggesting that the factors measure somewhat different aspects of the same broad construct.

The FIS was also found to differ in theoretically meaningful ways in relationship to participants’ sex. The gender role strain paradigm predicts that men will endorse traditional femininity ideology to a greater extent than their female counterparts, because traditional ideologies serve to uphold gender-based power structures, which ultimately benefit men (Levant 1996). Overall, participants did not endorse traditional views of femininity ideology, with females endorsing less traditional views than males, as hypothesized.

Interestingly, the same pattern of endorsement emerged among both women and men, with the traditional norm of Caretaking being endorsed most strongly by both men and women, followed by Purity, Emotionality, Stereotypical Feminine Roles, and Dependency/Deference, respectively. These findings are consistent with research on family work. Although the feminist movement has made great strides in creating opportunities for women to enter into the work force (Padavic and Reskin 2002), the expectation for women to be the main caretaker for children and other family members has remained a bedrock criterion of the modern feminine role. In general, US married women spend much more time in family work than their husbands, as reflected in Hochschild’s (1997) data, that show that US married women have 15 h less leisure time each week than their husbands, and have an average of 1,482 h of unpaid family work in a year. Results of the present study demonstrate that though women and men endorse traditional femininity ideology less in certain domains of the traditional feminine role, they are both likely to endorse to the traditional feminine norm of Caretaking.

Differences between the four racial/ethnic groups were found on three of the five factors (Stereotypic Image and Activities, Dependence/Deference, and Emotionality) and on the Total Traditional scale. Because the sample sizes of the non-European American groups were small we did not attempt to further determine the significance of the differences between these means and could not test the hypothesis that racial and ethnic minorities will endorse traditional femininity ideology to a greater extent that will European Americans. However, this is an important area for future research, which should take into account the following considerations from the literature.

First, with regard to African Americans, African American women have not historically been held to traditional feminine norms. During slavery, African American women developed multiple roles, encompassing both stereotypical masculine and feminine characteristics, as a coping mechanism to enable survival (Burgess 1994). Interestingly, previous research found that while African-Americans endorsed traditional femininity ideology to a lesser extent than did European-Americans (Franklin 1998), African Americans endorsed traditional masculinity ideology to a greater extent than did European Americans (Pleck et al. 1994; Levant and Majors 1997; Levant et al. 1998). Future research should examine the relationship between the endorsement of masculinity and femininity ideologies among African American and European American participants to better understand these differences.

Second, according to Bradshaw (1994), Asian American women are exposed to conflicting gender stereotypes, compounded by sexism and racism. On the one hand, popular media have depicted Asian women as sexual labor for the US military, tourism, and commercial activities. Simultaneously, however, Asian American women are stereotyped as androgynous, asexual, submissive, and domesticated. Furthermore, Asian cultures, based on Confucius philosophy, tend to be particularly oppressive toward women (Bradshaw 1994). Hence it would be very interesting to investigate femininity ideology among Asian Americans.

Third, prior research on traditional masculinity ideology shows that Latino/a participants tend to endorse traditional masculinity ideology to a greater extent than their European American counterparts (Abreau et al. 2000; Levant et al. 2003). The Mexican term “marianismo,” which derives from Spanish influence, is the opposite of the more popular term “machismo” (Torres 1998). Marianismo describes the female gender role, as she is expected to be pure, submissive, passive, maternal, and lacking of sexual desires. Stevens (1994) states that expectations of marianismo influence the socialization practices of most Latin families, including those in the USA. Future research should further explore endorsements of traditional femininity ideology among Latino/a participants.

The goal of the study was to assess the psychometric properties of the FIS in order to advance research informed by the gender role strain paradigm. Results indicate that the FIS is a reliable and valid measure of traditional femininity ideology and thus comparable to the MRNI. Furthermore, the findings suggest that participants varied in terms of sex and race/ethnicity regarding their endorsement of traditional femininity ideology. Limitations include the nearly homogenous convenience sample in terms of race/ethnicity and the use of self-report measures. Additionally, we were unable to obtain test–retest data and we recommend that future studies address this limitation. However, with these data as a foundation, the FIS could be useful tool to investigate traditional and non-traditional ideology as it relates to measures of gender role stress, conflict, conformity, as well as indices of health and mental health.

References

Abreau, J. M., Goodyear, R. K., Campos, A., & Newcomb, M. D. (2000). Ethnic belonging and traditional masculinity ideology among African Americans, European Americans, and Latinos. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 1, 75–86.

Bargad, A., & Hyde, J. (1991). Women’s studies: A study of feminist identity development in women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 15, 181–201.

Bartlett, M. S. (1954). A note on the multiplying factors for various chi square approximations. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B, 16, 296–298.

Bem, S. (1974). The measurement of psychological androgyny. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 42, 155–162.

Bem, S. (1981). Gender schema theory: A cognitive account of sex-typing. Psychological Review, 88, 354–364.

Berger, J. M., Levant, R. F., McMillan, K. K., Kelleher, W., & Sellers, A. (2005). Impact of gender role conflict, traditional masculinity ideology, alexithymia, and age on men’s attitudes toward psychological help seeking. Psychology of Men and Masculinity, 6, 73–78.

Bradshaw, C. K. (1994). Asian and Asian American women: Historical and political considerations in psychotherapy. In L. Comas-Diaz & B. Greene (Eds.), Women of color: Integrating ethnic and gender identities in psychotherapy (pp. 72–113). New York: Guilford.

Burgess, N. J. (1994). Gender role revisited: The development of the woman’s place among African American women in the United States. Journal of Black Studies, 24, 391–401.

Catell, R. B. (1966). The scree test for the number of factors. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 1, 245–276.

Cohen, J. (1977). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (revised edition). New York: Academic.

Davis, F. (1987). Antecedents and consequents of gender role conflict: An empirical test of sex role strain analysis (Doctoral dissertation, Ohio State University). Dissertation Abstracts International, 48(11), 3443.

Eisler, R. M. (1995). The relationship between masculine gender role stress and men’s health risk: The validation of a construct. In R. F. Levant & W. S. Pollack (Eds.), A new psychology of men (pp. 207–225). New York: Basic Books.

Franklin, A. V. (1998). A comparative analysis of African Americans and European-Americans perceived gender roles using the Femininity Ideology Scale. Master’s thesis, Florida Institute of Technology.

Good, G. E., & Mintz, L. B. (1990). Gender role conflict and depression in college men: Evidence for compounded risk. Journal of Counseling and Development, 69, 17–21.

Gronemeyer, K. M. (1998). Age-related differences in endorsement of traditional femininity roles using the femininity ideology scale. Master’s thesis, Florida Institute of Technology.

Hochschild, A. (1997). The second shift: Working parents and the revolution at home. New York, NY: Viking.

Kaiser, H. F. (1974). An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrika, 39, 31–36.

Lehman, P. (2000). A validity study of the femininity ideology scale. Master’s thesis, Florida Institute of Technology.

Levant, R. (1996). The new psychology of men. Professional Psychology, 27, 259–265.

Levant, R. F., & Fischer, J. (1998). The male role norms inventory. In C. M. Davis, W. H. Yarber, R. Bauserman, G. Schreer, & S. L. Davis (Eds.), Sexuality-related measures: A compendium, 2nd edn (pp. 469–472). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Levant, R. F., Hirsch, L., Celentano, E., Cozza, T., Hill, S., MacEachern, M. (1992). The male role: An investigation of norms and stereotypes. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 14, 325–337.

Levant, R., & Majors, R. (1997). An investigation into variations in the construction of the male gender role among young African-American and European-American women and men. Journal of Gender, Culture and Health, 2, 33–43.

Levant, R., Majors, R., & Kelley, M. (1998). Masculinity ideology among young African-American and European-American women and men in different regions of the United States. Cultural Diversity and Mental Health, 4, 227–236.

Levant, R. F., & Richmond, K. (2007). A program of research on masculinity ideologies using the male role norms inventory. Journal of Men’s Studies, 15, 130–146.

Levant, R. F., Richmond, K., Majors, R., Inclan, J. E., Rossello, J. M., Heesacker, M., et al. (2003). A multicultural investigation of masculinity ideology and alexithymia. Psychology of Men and Masculinity, 4, 91–99.

Lippa, R. A. (2005). Subdomains of gender-related occupational interests: Do they form a cohesive bipolar M-F dimension? Journal of Personality, 73, 693–730.

Mahalik, J., Morray, E., Coonerty-Femiano, A., Ludlow, L., Slattery, S., & Smiler, A. (2005). Development of the conformity to feminine norms inventory. Sex Roles: A Journal of Research, 52, 417–435.

Marsh, H. W., & Bryne, B. M. (1991). The differentiated additive androgyny model: Relations between masculinity, femininity and multiple dimensions of self-concept. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61, 811–828.

Myers, J., & Well, A. (1995). Research design & statistical analysis. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

O’Neil, J. M., Helms, B. J., Gable, R. K., David, L., & Wrightsman, L. S. (1986). Gender role conflict scale: College men’s fear of femininity. Sex Roles, 14, 335–350.

Omar, G. A. (1998). Marital and parental status as variables in perceived gender roles using the femininity ideology scale. Master’s thesis, Florida Institute of Technology.

Orlofsky, J. L., & O’Heron, C. A. (1987). Stereotypic and nonstereotypic sex role trait and behavior orientations: Implications for personal adjustment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 1034–1042.

Padavic, I., & Reskin, B. (2002). Women and man at work. London: Pine Forge.

Pleck, J. H. (1981). The myth of masculinity. Cambridge, MA: MIT.

Pleck, J. H. (1995). The gender role strain paradigm: An update. In R. F. Levant & W. S. Pollack (Eds.), A new psychology of men (pp. 11–31). New York: Basic Books.

Pleck, J. H., Sonenstein, F. L., & Ku, L. C. (1994). Attitudes toward male roles: A discriminate validity analysis. Sex Roles, 30, 481–501.

Sharpe, M. J., & Heppner, P. P. (1991). Gender role, gender-role conflict, and psychological well-being in men. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 38, 323–330.

Spence, J. T. (1993). Gender-related traits and gender ideology: Evidence for a multifactorial theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64, 624–635.

Spence, J. T., & Buckner, C. E. (2000). Instrumental and expressive traits, trait stereotypes, and sexist attitudes: What do they signify? Psychology of Women Quarterly, 24, 44–53.

Spence, J. T., & Helmreich, R. L. (1978). Masculinity and femininity: Their psychological dimensions, correlates, and antecedents. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Stevens, E. (1994). Marianismo: The other face of machismo in Latin America. In G. M. Yeager (Ed.), Confronting change, challenging tradition: Women in Latin American history. Wilmington: Jaguar Books.

Thompson, E. H., & Pleck, J. H. (1995). Masculinity ideology: A review of research instrumentation on men and masculinities. In R. F. Levant & W. S. Pollack (Eds.), A new psychology of men (pp. 129–163). New York: Basic Books.

Tolman, D., & Porche, M. (2000). The adolescent femininity ideology scale: Development and validation of a new measure for girls. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 24, 365–376.

Torres, J. B. (1998). Masculinity and gender roles among Puerto Rican men: machismo on the U.S. mainland. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 68, 16–26.

Acknowledgement

Ronald Levant and Katherine Richmond contributed nearly equally to this research project and the order of authorship between them was determined by a coin toss. We also want to acknowledge the contributions of Dr. Carol Philpot, who, when she was a professor at the Florida Institute of Technology, organized a group of Master’s students that developed the Femininity Ideology Scale (FIS) and reported work on it in their theses. Finally, we want to acknowledge the help with statistical analysis of our late friend and colleague, Dr. Al Sellers.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Levant, R., Richmond, K., Cook, S. et al. The Femininity Ideology Scale: Factor Structure, Reliability, Convergent and Discriminant Validity, and Social Contextual Variation. Sex Roles 57, 373–383 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-007-9258-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-007-9258-5