Abstract

This study was designed to investigate sexual harassment perceptions based on continuation of unwanted sexual attention following victim resistance. Participants were 504 undergraduates who responded to statements regarding a sexual harassment scenario, in which the perpetrator continued or discontinued attention, which varied in severity according to nonphysical, physical, or restraint contact. Results showed that continued attention and any type of physical contact strengthened harassment perceptions, although men’s perceptions were weaker unless restraint was present. No sex differences were observed in the restraint condition. Women had stronger perceptions than men did in the physical condition, but showed a non-significant trend toward stronger perceptions in the nonphysical condition. Findings suggest that continuation following resistance may clarify for observers that harassment is occurring. Conceptualizations of harassment severity are suggested.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Sexual harassment of women by men in the workplace is quite prevalent and can negatively impact job performance and psychological well-being (Cochran, Frazier, & Olson, 1997; Fitzgerald, Drasgow, Hulin, Gelfand, & Magley, 1997; Gutek & Koss, 1993; Hesson-McInnes & Fitzgerald, 1997; Magley, Hulin, Fitzgerald, & DeNardo, 1999; O’Donohue, Downs, & Yeater, 1998; Pryor, 1995; Satterfield & Muehlenhard, 1997; Schneider, Swan, & Fitzgerald, 1997; Stockdale, 1998). However, many ambiguous socio-sexual behaviors occur in the workplace that are intended to be flirtatious or express romantic interest and may not be intended as harmful (Gutek, Cohen, & Konrad, 1990; Williams, Giuffre, & Dellinger, 1999). To clarify that behavior is unwelcome, the US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) (1992, 1994) recommended that victims directly tell their harassers to stop, and indicated that if behavior is unwelcome and repetitive, it can be defined as sexual harassment. The US Merit Systems Protection Board (USMSPB) (1981, 1988, 1995) surveys suggest that asking a perpetrator to stop is perhaps the most effective response in diffusing harassment situations. However, studies of perceptions of harassment based on continued harassing behavior in direct response to verbal resistance from a victim are lacking.

Generally, research shows that any type of resistance from the victim, such as saying “stop,” strengthens perceptions of sexual harassment (Henry & Meltzoff, 1998; Hurt, Maver, & Hofmann, 1999; Jones & Remland, 1992; Jones, Remland, & Brunner, 1987; Remland & Jones, 1985; York, 1989). However, there may be certain situations in which saying “stop” is not sufficient to convince individuals that sexual attention is unwanted because other factors may override or counter the verbal resistance. Hence, although a victim may say “stop,” other situational factors may lead individuals to perceive that the victim is using token resistance to sexual attention, that is, saying “stop,” but truly wishing for the attention to continue. Token resistance is a concept that was originally applied to date rape (Muehlenhard & Hollabaugh, 1988), but has recently been extended to sexual harassment (Osman, 2004). Based on the idea that women do not want to be judged negatively for violating the traditional feminine role by acting too interested in sexual attention, some individuals may perceive that when a woman says “stop,” she may not truly mean it. Hence, individuals may rely more heavily on other cues to interpret her meaning. In previous research, situational factors that may lead individuals to think that verbal resistance is merely token have largely been focused on the victim’s behavior, such as the victim’s facial expression (smiling), provocative dress, and late timing of protest (Cassidy & Hurrell, 1995; Kopper, 1996; Osman, 2004; Shotland & Goodstein, 1983). On the other hand, contextual factors involving the perpetrator’s behavior may also influence perceptions of harassment when a victim says “stop.”

Most studies of perceptions of harassment present participants with a perpetrator’s initial socio-sexual behavior and then ask participants to respond to sexual harassment-related measures (Baker, Terpstra, & Larntz, 1990; G. L. Blakely, E. H. Blakely, & Moorman, 1995; Burgess & Borgida, 1997; Corr & Jackson, 2001; Dougherty, Turban, Olson, Dwyer, & Lapreze, 1996; Gervasio & Ruckdeschel, 1992; Icenogle, Eagle, Ahmad, & Hanks, 2002; Loredo, Reid, & Deaux, 1995; Matsui, Kakuyama, Onglatco, & Ogutu, 1995; McKinney, 1992; Soloman & Williams, 1997; Tata, 1993; Terpstra & Baker, 1987; Williams, Brown, Lees-Haley, & Price, 1995). A smaller number of studies concern perceptions of harassment based on the victim’s response to the perpetrator’s harassing behavior (Henry & Meltzoff, 1998; Hurt et al., 1999; Jones & Remland, 1992; Jones et al., 1987; Remland & Jones, 1985; York, 1989). Whereas researchers have manipulated initial harassing behavior and victims’ responses to those behaviors, investigations of perceptions of harassment based on the perpetrator’s behavior immediately following the victim’s resistance are lacking in the literature. Based on the EEOC’s definition of sexual harassment as repetitive, it is important to understand how individuals may perceive harassment based on a perpetrator’s ongoing behavior after a victim resists. If certain situational factors are powerful enough to convince individuals that when a victim says “stop,” she really wishes for the sexual attention to continue, then whether or not that attention actually continues in direct response to victim resistance may also influence perceptions of harassment.

Theory on social influence predicts that individuals are more likely to look to others for how to interpret less clear situations than they are in situations in which the interpretations are easy and obvious (Baron, Vandello, & Brunsman, 1996). Therefore, when making judgments about ambiguous socio-sexual situations regarding the meaning of a woman’s resistance, perhaps individuals look to a perpetrator’s behavior following the resistance for a cue to help them to determine whether or not the situation is harassment. If the perpetrator continues his socio-sexual behavior, it may be inferred that he believes the victim wants the attention, which may influence others also to adopt his interpretation.

Continuation of Harassment

Although some studies have included scenarios in which harassment occurs despite the victim’s refusal, the immediate continuation of harassment after a victim resists has never been systematically manipulated (Baker et al., 1990; De Judicibus & McCabe, 2001; Foulis & McCabe, 1997; Rhodes & Stern, 1994; Sheets & Braver, 1999; Summers, 1991; Summers & Myklebust, 1992; Tata, 2000). Studies that have concerned the frequency of harassment are perhaps the most relevant in this regard. Generally, the more frequent the harassing behavior, the more likely the behavior is to be perceived as inappropriate and sexually harassing (Ellis, Barak, & Pinto, 1991; Hurt et al., 1999; Thomann & Weiner, 1987). Two such investigations included scenarios that manipulated the perpetrator’s harassing behavior and the victim’s response, in addition to the frequency of the harassing behavior. After describing a perpetrator’s socio-sexual behavior, Hurt et al. (1999) presented some scenarios that described its frequency (“he has done this several times before”), followed by the victims’ response (“ignores his behavior and changes the subject”). However, it is not clear that the victim ever directly asked the perpetrator to stop on any occasion. After a description of a victim’s immediate response to a perpetrator’s harassing behavior, Thomann and Weiner (1987) provided information on the frequency of the harassment (“this was the only time such an incident occurred” or “this was one of many such occurrences, and she has never complied with his requests”). However, the nature of this previous non-compliance in the frequent condition was not described, and the subsequent harassing incidents seemed to be on separate occasions. Hence, there is a need for research on the immediate continuation of harassing behavior following verbal resistance from a victim.

Severity of Harassment and Sex of Participant

Generally, perceptions of harassment are weaker when harassing behaviors are more ambiguous and less severe (Burgess & Borgida, 1997; Ellis et al., 1991; Jones & Remland, 1992; Terpstra & Baker, 1987; Williams et al., 1995). This seems logical given that ambiguous situations are more vulnerable to interpretation than are more obvious and severe incidents of sexual harassment. Also, women tend to have stronger perceptions of harassment than men do in more ambiguous situations (Blakely et al., 1995; Burgess & Borgida, 1997; Burian, Yanico, & Martinez, 1998; Frazier, Cochran, & Olson, 1995; Gutek, 1995; Johnson, Benson, Teasdale, Simmons, & Reed, 1997; Tata, 1993; Williams et al., 1995). For example, one dimension on which the severity of the perpetrator’s behavior has been defined involves whether or not the unwanted attention is physical or verbal in nature. Overall, physical attention has been perceived as more severe and more likely than verbal attention to be harassment, and sex differences in perceptions are more consistent when the attention is verbal (Burgess & Borgida, 1997; Johnson et al., 1997; Osman, 2004; Williams et al., 1995). Studies of the frequency of harassment seem to support these sex differences as well. For example, although Hurt et al. (1999) found that women more than men judged situations as harassing, Thomann and Weiner (1987) found that sex was not a significant predictor of harassment judgments. However, Hurt et al. presented many behaviors that seemed more ambiguous (e.g., “asks for help with work,” “comments on suit,” “asks for phone number,” “puts arm around while explaining work”) than did Thomann and Weiner (e.g., “asked her to go out for drinks so that they could get to know each other better” or “asked her to go to a motel”). Thus, sex differences in perceptions of sexual harassment appear to depend on the severity of the perpetrator’s actions.

Rationale

The present study builds on existing research on initial harassing behavior and victim responses by investigating perceptions of harassment based on continuation of harassing behavior following victim resistance. In certain situations, victim resistance may be perceived as token, so that individuals may think that the attention is wanted and, thus, not harassment. Continuation of a perpetrator’s harassing behavior may be a situational variable that also influences perceptions of sexual harassment. In terms of perpetrator behaviors, it has been shown that severity of unwanted attention, such as whether it is verbal or physical, influences perceptions of harassment. Individuals more clearly view more severe behaviors as harassment. Less severe behaviors are not as clearly perceived as harassment, especially by men. Furthermore, with ambiguous behaviors, individuals may be more likely to rely on other people’s social cues to help to clarify how the situation should be interpreted. If a perpetrator continues his behavior after victim resistance, it may serve as a situational cue that the victim truly wants the attention and, hence, perceptions of harassment may weaken. Similarly, the discontinuation of the perpetrator’s behavior may be seen as evidence that the victim meant it when she said “stop,” and, hence, perceptions of harassment may strengthen. When the harassment is more severe there may be less need to look to others for social cues regarding whether or not the attention is wanted. Therefore, it was predicted that when the least severe attention continues, perceptions of sexual harassment will be weaker than when harassment does not continue, whereas more severe harassing behaviors (i.e., those that include physical attention) will be perceived as harassment regardless of whether the behavior is continued (Hypothesis 1).

Because women are more likely than men to perceive less severe attention as harassment, it was also predicted that women will have stronger perceptions of sexual harassment than men unless physical attention is present (Hypothesis 2). Lastly, because physical attention tends to be perceived as more harassing than verbal attention, it was predicted that perceptions of harassment will be stronger when the harassing behavior includes physical attention than when it does not (Hypothesis 3).

Method

Participants

Participants were 181 male and 323 female undergraduate students. Although participants were students, 98% reported employment experience (at least 84% reported part-time experience and 30% reported full-time experience). The large majority reported that they were single (99%) and 17–22 years old (96%). European Americans accounted for 83% of the sample, 10% were African Americans, 2% were Asian Americans, and 3% were Hispanic Americans. Religious affiliation was 36% Catholic, 8% Protestant, 14% Methodist, 7% Baptist, 6% Lutheran, 15% Atheist, and 3% Jewish. Sixty-two percent were raised in a suburban area, 23% in a rural area, and 15% in an urban area.

Procedure and measures

Participation took approximately 20 min and occurred in a classroom setting. Participants responded to questionnaires that requested demographic information and contained statements pertaining to a series of scenarios that described situations involving men and women. The pertinent scenario involved a socio-sexual interaction in the workplace between Jodi and Eric, who worked for the same company. In each of the six versions of this scenario, as Eric walked up from behind and passed Jodi in the hall, he targeted her with one of three types of sexual attention with increasing degrees of severity, which was the first independent variable. “As Eric passes” either (1) “Jodi sees him look briefly at her rear as he says, ‘Nice body’” (nonphysical condition), or (2) “he pats her on the rear and says, ‘Nice body’” (physical condition), or (3) “he suddenly presses her against the wall with his body as he grabs her rear and says, ‘Nice body’” (restraint condition). These behaviors were adapted from previous research, in which the perceived severity of the behaviors was established in pilot testing (Cohen & Gutek, 1985; Williams et al., 1995). To verify that the behaviors used in the present study differed in perceived severity, a manipulation check was included. Participants responded on a Likert-type scale that ranged from 1—strongly agree to 7—strongly disagree that “Eric’s behavior was severe.” Subsequent analyses confirmed that each scenario significantly differed from the others in degree of severity in the expected directions from least severe to most severe (nonphysical, M = 5.03, SD = 1.6; physical, M = 3.6, SD = 1.8; restraint, M = 2.6, SD = 1.6), p’s < 0.0001. (Lower scores indicate more severe behavior).

In each condition, Jodi responded to Eric’s attention by saying “Stop it!” The second independent variable was whether or not Eric continued the harassment by targeting her with the same attention again or discontinued his behavior. (1) In the nonphysical condition “Eric looks briefly at her rear again and replies, ‘But you really do have a nice body,’ and he continues on his way down the hall” (continued harassment), or he “continues on his way down the hall” (discontinued harassment). (2) In the physical condition, “Eric pats her rear again and replies, ‘But you really do have a nice body,’ and he continues on his way down the hall” (continued harassment), or he “continues on his way down the hall” (discontinued harassment). (3) In the restraint condition, “Eric, continuing to press her against the wall and grab her rear, replies, ‘But you really do have a nice body.’ Then he backs away from Jodi and continues on his way down the hall” (continued harassment), or “he backs away from Jodi and continues on his way down the hall” (discontinued harassment).

Participants then indicated their agreement with five statements to measure perceptions of sexual harassment. Degree of agreement was measured on Likert-type scales that ranged from 1—strongly agree to 7—strongly disagree. The statements were “Jodi wanted this attention from Eric,” “Jodi welcomed this attention from Eric,” “Jodi enjoyed this attention from Eric,” “Eric violated Jodi’s rights,” and “Eric sexually harassed Jodi.” The ratings of the last two statements were reverse scored, and then the ratings of the five statements were summed for a total, so that higher scores indicated stronger agreement that the situation was sexual harassment. These statements were adapted from previous research on perceptions of harassment, in which the Cronbach alpha was 0.90 (Osman, 2004). The Cronbach alpha in the present sample was 0.84.

Results

A 2 × 3 × 2 ANOVA (continuation of harassment × severity of harassment × sex of participant) was performed on the perceptions of sexual harassment scores. The expected interaction between continuation and severity of harassment was not significant, F(5, 498) = 0.143, p = 0.87, partial η 2 = 0.001, although there was a main effect for continuation of harassment, F(1, 502) = 5.96, p = 0.015, partial η 2 = 0.012. Perceptions of harassment when the attention continued (M = 30.27, SD = 5.44) were stronger than when it discontinued (M = 28.89, SD = 5.67). Therefore, Hypothesis 1 was not supported.

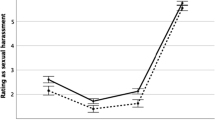

Regarding Hypothesis 2, as expected, there was a significant interaction between severity of harassment and sex of participant, F(5, 498) = 3.26, p = 0.039, partial η 2 = 0.013. To test this hypothesis more specifically, pairwise comparisons were performed using Dunn’s procedure to control for experimentwise Type I error (with a 0.004 significance level needed for each comparison made in this study; Kirk, 1995). Consistent with expectations, harassment perceptions of men and women did not differ in the most severe restraint condition, p = 0.830. However, there were some unexpected patterns. Although there was a tendency for women to have stronger perceptions of harassment than men did in the least severe nonphysical condition, p = 0.035, they did not differ at the required level. Also, men and women did significantly differ in the physical condition, p < 0.0001.

Men’s perceptions of harassment in the restraint condition were stronger than in both the nonphysical and physical conditions (p’s < 0.001), and there was no difference between the latter two. As for women, perceptions of harassment in the nonphysical condition were weaker than in both the physical and restraint conditions (p’s < 0.0001), and there was no difference between these latter two. See Table 1 for summary of means, standard deviations, and pairwise comparisons for severity of harassment and sex of participant interaction.

The findings for women and the significant main effect for severity of harassment, F(2, 501) = 42.83, p < 0.0001, partial η 2 = 0.148, support Hypothesis 3. As predicted overall, follow-up pairwise comparisons for this main effect revealed that perceptions in the nonphysical condition (M = 26.61, SD = 5.89) were weaker than perceptions of harassment in both the physical (M = 30.47, SD = 5.03) and restraint conditions (M = 31.66; SD = 4.49), p’s < 0.0001. The latter two conditions did not differ at the required level, p = 0.023. In addition to the main effects for continuation and severity, there was also a significant main effect for sex of participant, F(1, 502) = 13.85, p < 0.0001, partial η 2 = 0.027. Overall, men (M = 28.33, SD = 6.11) had weaker perceptions of sexual harassment than women (M = 30.28, SD = 5.16) did. See the summary of main effect findings in Table 2. Other than the expected interaction between severity of harassment and sex of participant, no other interactions were significant (p’s > 0.05).

Discussion

This was perhaps the first study to examine perceptions of harassment based on a perpetrator’s immediate continuation of harassing behavior following a victim’s verbal resistance to unwanted sexual attention. Contrary to expectations, it was found that, if the perpetrator’s behavior continued following the victim’s resistance, perceptions of harassment were strengthened regardless of harassment severity. If the behavior stopped, perceptions of harassment were weakened. This finding supports the EEOC’s (1992, 1994) guideline that, if sexual attention is repeated after a victim offers verbal resistance, it can be defined as harassment. Continuation of unwanted sexual behavior after a victim says “stop” may help clarify that the behavior is occurring against a woman’s will and strengthen perceptions of harassment. In contrast, if the perpetrator discontinues the unwanted behavior, as requested by the victim, it may serve as a situational cue that the behavior was not intended as harmful and, thus, weaken perceptions of sexual harassment. In the least severe, most ambiguous situation, findings were the opposite of the prediction based on the rationale that respondents may look to the perpetrator’s behavior for a cue regarding his interpretation of the situation and then adopt that perception as well. Thus, if he continued his behavior, it might be inferred that he thinks the victim’s resistance was token. However, it may be that individuals do not consider the perpetrator to be a reliable source for the correct interpretation of the woman’s verbal resistance given his role as the potential offender.

Overall, women had stronger perceptions of harassment than men did, and, consistent with expectations and the results of previous research (Williams et al., 1995), there was no sex difference in perceptions of the most severe condition that included physical restraint. However, women had stronger perceptions of harassment than men did in the relatively less severe physical condition, and, although women had a tendency toward stronger perceptions, they did not significantly differ from men in the least severe nonphysical condition. Women followed the overall expected pattern; they showed no differences between the two conditions that involved physical attention, and had stronger harassment perceptions in these two conditions than in the nonphysical condition. On the other hand, men in the most severe restraint condition had stronger perceptions of harassment than did men in each of the other conditions, between which there was no difference. Perhaps men and women have different thresholds for types of physical contact that influence their harassment judgments. It may not be the simple presence of physical contact, but rather the severity of that particular physical contact that differentiates men’s and women’s perceptions. Whereas men were less convinced than women that a pat on the rear was harassment, both seemed to agree that bodily restraint did constitute harassment.

Although men and women tended to differ in the nonphysical condition, severity of behavior may also explain why there was no significant sex difference after the adjustment for multiple comparisons. Perhaps the specific behavior of a brief look and sexual comment (“You have a nice body”) is on the less severe end of the socio-sexual behavior continuum, so that men and women were more in agreement regarding their perceptions of harassment. It is possible that this particular behavior was viewed by both men and women as an honest opinion, compliment, flattery, and/or harmless flirtation. Therefore, whereas previous researchers have reported that sex differences in perceptions of harassment disappear as harassing behavior becomes more severe, the present results support that general trend and additionally suggest that sex differences may also disappear as harassing behavior becomes far less severe.

Overall, perceptions of harassment were stronger for physical attention than for verbal attention, which is generally consistent with past research (Burgess & Borgida, 1997; Johnson et al., 1997; Osman, 2004; Williams et al., 1995). Note, however, that Dougherty et al. (1996) was one exception to these general findings. They found that a man’s behavior directed toward a woman was rated more negatively when it consisted of verbal comments than when it included physical touch. However, the authors suggested that this may have been due to the less severe type of physical harassment that they implemented (arm around shoulder) versus the more severe types of physical attention described in the present and other studies (physical contact with buttocks or breasts). Therefore, specific behaviors are important to consider in addition to their categorizations, such as physical or verbal.

An important theoretical application of the present study is that, although the victim always asked the perpetrator to “stop” his behavior, the meaning of this resistance may not always have been interpreted similarly. Two situational factors involving perpetrator behavior that influenced perceptions of harassment in the face of victim resistance were severity and continuation of sexual attention. Less severe harassing behavior may be a situational factor that leads individuals to perceive that a victim who says “stop” may not really mean it. Again, perhaps ambiguous socio-sexual behavior is perceived as flattery, and, hence, the victim’s verbal resistance is perceived as token. On the other hand, when a perpetrator’s behavior is on the more extreme end of the severity continuum, the nature of that behavior may cue individuals to understand that “stop” means “stop” and that the behavior is unwanted (Osman, 2004). Continuation of sexual attention following victim resistance resulted in stronger perceptions of sexual harassment than discontinued behavior did. Perhaps the meaning of “stop” becomes clearer when the perpetrator acts against it, and, thus, the harassment becomes more salient. Another possibility is that the continuation of unwanted sexual attention may be another dimension on which to conceptualize severity of behavior. Engaging in harassing behavior one time may be viewed as less severe than engaging in that same behavior a second time. As the behavior continues repeatedly, it may be considered more severe. The point on the severity continuum of socio-sexual behavior at which the perceived meaning of resistance changes may depend on other individual characteristics in addition to sex, such as beliefs and attitudes.

Although these findings help to clarify the role of perpetrator continuation and severity of unwanted sexual attention in perceptions of harassment, several important directions remain for future research in this area. Future investigators might consider harassment judgments based on the social influence of other observer’s reactions rather than perpetrator reactions to ambiguous socio-sexual behavior. Future researchers should also continue to disentangle sex differences in perceptions of harassment with regard to particular behaviors and their levels of severity. Furthermore, situational factors related to either the perpetrator’s or victim’s behavior that may influence perceptions of victim resistance and sexual harassment should continue to be considered.

References

Baker, D. D., Terpstra, D. E., & Larntz, K. (1990). The influence of individual characteristics and severity of harassing behavior on reactions to sexual harassment. Sex Roles, 22, 305–325.

Baron, R. S., Vandello, J. A., & Brunsman, B. (1996). The forgotten variable in conformity research: Impact of task importance on social influence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71, 915–927.

Blakely, G. L., Blakely, E. H., & Moorman, R. H. (1995). The relationship between gender, personal experience, and perceptions of sexual harassment in the workplace. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 8, 263–274.

Burgess, D., & Borgida, E. (1997). Sexual harassment: An experimental test of the sex-role spillover theory. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 23, 63–75.

Burian, B. K., Yanico, B. J., & Martinez, C. R. (1998). Group gender composition effects on judgments of sexual harassment. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 22, 465–480.

Cassidy, L., & Hurrell, R. M. (1995). The influence of victim’s attire on adolescents’ judgment of date rape. Adolescence, 30, 319–323.

Cochran, C. C., Frazier, P. A., & Olson, A. M. (1997). Predictors of responses to unwanted sexual attention. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21, 207–226.

Cohen, A. F., & Gutek, B. A. (1985). Dimensions of perceptions of social-sexual behavior in a work setting. Sex Roles, 13, 317–327.

Corr, P. J., & Jackson, C. J. (2001). Dimensions of perceived sexual harassment: Effects of gender and status/liking of protagonist. Personality and Individual Differences, 30, 525–539.

De Judicibus, M., & McCabe, M. P. (2001). Blaming the target of sexual harassment: Impact of gender role, sexist attitudes, and work role. Sex Roles, 44, 401–417.

Dougherty, T. W., Turban, D. B., Olson, D. E., Dwyer, P. D., & Lapreze, M. W. (1996). Factors affecting perceptions of workplace sexual harassment. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 17, 489–501.

Ellis, S., Barak, A., & Pinto, A. (1991). Moderating effects of personal cognitions on experienced and perceived sexual harassment of women at the workplace. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 21, 1320–1337.

Fitzgerald, L. F., Drasgow, F., Hulin, C. L., Gelfand, M. J., & Magley, V. J. (1997). Antecedents and consequences of sexual harassment in organizations: A test of an integrated model. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82, 578–589.

Frazier, P. A., Cochran, C. C., & Olson, A. M. (1995). Social science research on lay definitions of sexual harassment. Journal of Social Issues, 51, 21–37.

Foulis, D., & McCabe, M. P. (1997). Sexual harassment: Factors affecting attitudes and perceptions. Sex Roles, 37, 773–798.

Gervasio, A. H., & Ruckdeschel, K. (1992). College students’ judgments of verbal sexual harassment. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 22, 190–211.

Gutek, B. A. (1995). How subjective is sexual harassment? An examination of rater effects. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 17, 447–467.

Gutek, B. A., Cohen, A. G., & Konrad, A. M. (1990). Predicting social-sexual behavior at work: A contact hypothesis. Academy of Management Journal, 33, 560–577.

Gutek, B. A., & Koss, M. P. (1993). Changed women and changed organizations: Consequences of and coping with sexual harassment. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 42, 28–48.

Henry, J., & Meltzoff, J. (1998). Perceptions of sexual harassment as a function of target’s response type and observer’s sex. Sex Roles, 39, 253–271.

Hesson-McInnis, M. S., & Fitzgerald, L. F. (1997). Sexual harassment: A preliminary test of an integrative model. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 27, 877–901.

Hurt, J. L., Maver, J. A., & Hofmann, D. (1999). Situational and individual influences on judgments of hostile environment sexual harassment. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 29, 1395–1415.

Icenogle, M. L., Eagle, B. W., Ahmad, S., & Hanks, L. A. (2002). Assessing perceptions of sexual harassment behaviors in a manufacturing environment. Journal of Business and Psychology, 16, 601–616.

Johnson, J. D., Benson, C., Teasdale, A., Simmons, S., & Reed, W. (1997). Perceptual ambiguity, gender, target intoxication: Assessing the effects of factors that moderate perceptions of sexual harassment. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 27, 1209–1221.

Jones, T. S., & Remland, M. S. (1992). Sources of variability in perceptions of and responses to sexual harassment. Sex Roles, 27, 121–142.

Jones, T. S., Remland, M. S., & Brunner, C. C. (1987). Effects of employment relationship, response of recipient, and sex of rater on perceptions of sexual harassment. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 65, 55–63.

Kirk, R. E. (1995). Experimental design procedures for the behavioral sciences. Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole.

Kopper, B. A. (1996). Gender, gender identity, rape myth acceptance, and time of initial resistance on the perception of acquaintance rape blame and avoidability. Sex Roles, 34, 81–91.

Loredo, C., Reid, A., & Deaux, K. (1995). Judgments and definitions of sexual harassment by high school students. Sex Roles, 32, 29–45.

Magley, V. J., Hulin, C. L., Fitzgerald, L. F., & DeNardo, M. (1999). Outcomes of self-labeling sexual harassment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 84, 390–402.

Matsui, T., Kakuyama, T., Onglatco, M., & Ogutu, M. (1995). Women’s perceptions of social sexual behavior: A cross-cultural replication. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 46, 203–215.

McKinney, K. (1992). Contrapower sexual harassment: The effects of student sex and type of behavior on faculty perceptions. Sex Roles, 27, 627–643.

Muehlenhard, C. L., & Hollabaugh, L. C. (1988). Do women sometimes say no when they mean yes? The prevalence and correlates of women’s token resistance to sex. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 872–879.

O’Donohue, W., Downs, K., & Yeater, E. A. (1998). Sexual harassment: A review of the literature. Aggression and Violent Behaviour, 3, 111–128.

Osman, S. L. (2004). Victim resistance: Theory and data on understanding perceptions of sexual harassment. Sex Roles, 50, 267–275.

Pryor, J. B. (1995). The phenomenology of sexual harassment: Why does sexual behavior bother people in the workplace? Consulting Psychology Journal, 47, 160–168.

Remland, M. S., & Jones, T. S. (1985). Sex differences, communication consistency, and judgments of sexual harassment in a performance appraisal interview. Southern Speech Communication Journal, 50, 156–176.

Rhodes, A. K., & Stern, S. E. (1994). Ranking harassment: A multidimensional scaling of sexual harassment scenarios. Journal of Psychology, 129, 29–39.

Satterfield, A. T., & Muehlenhard, C. L. (1997). Shaken confidence: The effects of an authority figure’s flirtatiousness on women’s and men’s self-rated creativity. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21, 395–416.

Schneider, K. T., Swan, S., & Fitzgerald, L. F. (1997). Job-related and psychological effects of sexual harassment in the workplace: Empirical evidence from two organizations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82, 401–415.

Sheets, V. L., & Braver, S. L. (1999). Organizational status and perceived sexual harassment: Detecting the mediators of a null effect. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 25, 1159–1171.

Shotland, R. L., & Goodstein, L. (1983). Just because she doesn’t want to doesn’t mean it’s rape: An experimentally based causal model of the perception of rape in a dating situation. Social Psychology Quarterly, 46, 220–232.

Soloman, D. H., & Williams, M. L. M. (1997). Perceptions of social-sexual communication at work: The effects of message, situation, and observer characteristics on judgments of sexual harassment. Journal of Applied Communications Research, 25, 196–216.

Stockdale, M. S. (1998). The direct and moderating influences of sexual-harassment pervasiveness, coping strategies, and gender on work-related outcomes. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 22, 521–535.

Summers, R. J. (1991). Determinants of judgments of and responses to a complaint of sexual harassment. Sex Roles, 25, 379–392.

Summers, R. J., & Myklebust, K. (1992). The influence of a history of romance on judgments and responses to a complaint of sexual harassment. Sex Roles, 27, 345–357.

Tata, J. (1993). The structure and phenomenon of sexual harassment: Impact of category of sexually harassing behavior, gender, and hierarchical level. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 23, 199–211.

Tata, J. (2000). She said, he said: The influences of remedial accounts on third-party judgments of coworker sexual harassment. Journal of Management, 26, 1133–1156.

Terpstra, D. E., & Baker, D. D. (1987). A hierarchy of sexual harassment. Journal of Psychology, 12, 599–605.

Thomann, D. A., & Wiener, R. L. (1987). Physical and psychological causality as determinants of culpability in sexual harassment cases. Sex Roles, 17, 573–591.

US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (1992). Questions and answers about sexual harassment. Cincinnati, OH: EEOC Publications Center.

US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (1994). Facts about sexual harassment. Cincinnati, OH: EEOC Publications Center.

US Merit Systems Protection Board (1981). Sexual harassment of federal workers: Is it a problem? Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office.

US Merit Systems Protection Board (1988). Sexual harassment in the federal government: An update. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office.

US Merit Systems Protection Board (1995). Sexual harassment in the federal workplace: Trends, progress, continuing challenges. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office.

Williams, C. W., Brown, R. S., Lees-Haley, P. R., & Price, J. R. (1995). An attributional (causal dimensional) analysis of perceptions of sexual harassment. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 25, 1169–1183.

Williams, C. L., Giuffre, P. A., & Dellinger, K. (1999). Sexuality in the workplace: Organizational control, sexual harassment, and the pursuit of pleasure. Annual Review of Sociology, 25, 73–93.

York, K. M. (1989). Defining sexual harassment in workplaces: A policy-capturing approach. Academy of Management Journal, 32, 830–850.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Osman, S.L. The Continuation of Perpetrator Behaviors that Influence Perceptions of Sexual Harassment. Sex Roles 56, 63–69 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-006-9149-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-006-9149-1