Abstract

This article reports the results of a preliminary study of ways that self-serving biases contribute to the maintenance of the cultural stereotype of the premenstrual woman. Self-serving biases such as illusory optimism and the false uniqueness effect lead individuals to believe that they are better than average and less likely to have negative experiences. Thus, even though individual women’s premenstrual symptoms are mild to moderate, they accept the stereotype because they believe that other women’s symptoms are worse than their own. Participants were 92 undergraduate women from two small colleges in southern New England. They completed measures of optimism, locus of control, and premenstrual symptoms and answered a series of questions about the incidence of PMS. Participants showed a significant tendency to believe that other women’s premenstrual symptoms are worse than their own. In addition, women who were high in optimism were significantly less likely to believe that they could be diagnosed with PMS, and they had significantly lower scores on the pain and behavior change subscales of the Menstrual Distress Questionnaire than did those low in optimism.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

What is the stereotype of the premenstrual woman? She is portrayed in popular culture as a frenzied, raging beast, a menstrual monster, prone to rapid mood swings and crying spells, bloated and swollen from water retention, out of control, craving chocolate, and likely at any moment to turn violent (Chrisler, 2002, 2003; Chrisler & Levy, 1990). The images that support the stereotype are ubiquitous in magazines, films, television shows, greeting cards, calendars, songs, self-help books, humor books, comic strips, advertising, and other media. Although few North Americans had heard of premenstrual syndrome prior to 1980, cultural beliefs that all women are overly emotional and behave erratically just before their menstrual periods have since become absorbed into a kind of folk wisdom—things “everyone knows” (Chrisler & Johnston-Robledo, 2002).

The stereotype of premenstrual women is so exaggerated that it is ridiculous. Few, if any, women resemble the stereotype, yet most women seem to be unwilling to resist it actively. Products that promote this negative image sell well, and many women embrace the PMS label for themselves and also apply it to other women (Cosgrove & Riddle, 2003; Lee, 2002; Swann & Ussher, 1995). We are curious about how the PMS stereotype is maintained, given that individual women do not resemble it—and are unlikely to know anyone who does.

Social psychologists have developed a number of theories about belief perseverance and self-serving biases that could be applied to help us understand why women believe that severe PMS is common despite their own personal experience. These include the illusory correlation (we easily associate random events when certain relationships are expected), illusory optimism (we believe that we are less vulnerable or luckier than other people), the fundamental error of attribution (when explaining the behavior of others, we underestimate situational factors and overestimate dispositional factors), and the false uniqueness effect (we see ourselves as relatively unusual). False ideas (such as the cultural stereotype of premenstrual women) bias information processing. Therefore cultural beliefs (e.g., “most women have severe PMS”) can be maintained even in the absence of evidence (e.g., “my own symptoms are mild to moderate”). Self-serving biases lead us to believe that we are better than average (e.g., “other women’s PMS is worse than mine”), and research has shown that subjective dimensions foster greater self-serving biases than do objective, behavioral dimensions (Meyers, 1996). Many PMS symptoms (e.g., anxiety, moodiness, fatigue) are subjective, and thus may lend themselves to the mechanisms described earlier.

Social comparison theory (Festinger, 1954; Suls & Miller, 1977) predicts that people are highly motivated to compare themselves to others in order to assess their own attributes, attitudes, abilities, and behavior. Disparate needs, such as for status (e.g., I am better than others) and belongingness (e.g., I am similar to others), can be satisfied through social comparison. Thus, “there is a persistent tension in social life between the desire to be similar to other people and the desire to be unique or different” (Suls & Wan, 1987, p. 211). Researchers (Monin & Norton, 2003; Van Lange, 1991) have found that people tend to underestimate the prevalence of desirable, yet common, behaviors (i.e., the false uniqueness effect), especially when those behaviors have a moral dimension. Furthermore, people whose attributes or opinions place them in a minority believe that there are many more people like themselves than is the case; that is, they tend not to perceive their actual distinctiveness (i.e., the false consensus effect; Ross, Greene, & House, 1977). For example, Ross et al. (1977) found that depressed and irritable participants thought that depression and irritability were more common (false consensus) among their peers than did participants who were not depressed and irritable. Tabachnik, Crocker, and Alloy (1983) found that both depressed and nondepressed participants in their study underestimated the number of people who are “psychologically healthy” (e.g., not depressed, cheerful), a case of false uniqueness for those who were not depressed.

Social comparison processes can be used by individuals to normalize stigmatized behavior or justify immoral behavior by assuming that many people do it (false consensus); whereas people who do not engage in such behaviors can feel better about themselves (more competent, higher in self-esteem) if they assume that they are among the minority of people who refrain from engaging in the behavior in question (false uniqueness) (Sherman, Presson, & Chassin, 1984; Suls & Wan, 1987). PMS is an interesting example of a condition that is both highly stigmatized and considered so common as to be women’s typical experience. It makes sense, then, that women who experience severe symptoms during the premenstrual phase would believe that most women share their experience, whereas women who experience mild (or no) symptoms would think that they are unique.

PMS also has a moral dimension. Feminist theorists (Laws, 1983; Chrisler & Caplan, 2003; Cosgrove & Riddle, 2003) have pointed out that the stereotypic premenstrual woman violates the feminine gender role. It is impossible simultaneously to be warm, open, kind, and nurturing (i.e., feminine) and depressed, angry, irritable, and otherwise unapproachable (i.e., stereotypically premenstrual). From girlhood, women have been taught to aspire to an idealized form of femininity in which they are calm, patient, cheerful, content with their lives, always willing to place others’ needs before their own, and able to make others feel calm and safe (Chrisler & Caplan, 2003; Cosgrove & Riddle, 2003). Women who are closer to the ideal are considered “good women” (who might feel even better if they believe that there are few others like them), whereas those who are further away from it are considered “bad women” (who might feel better about their inability to approximate the ideal if they believe that no one can be “good” all month). Self-help books promote the notion that women with PMS are “bad” (i.e., crazy or physiologically and behaviorally dysfunctional), but could become “good” with proper medical (or nutritional or psychiatric) treatment (Chrisler, 2003). There is even a self-help book for religious women that makes morality explicit. The author (Frangipane, 1992) states that premenstrual women’s emotional experiences are not symptoms, but sins; PMS is caused by Satan, who finds it easier to tempt vulnerable women when their hormones are “imbalanced.”

An important component of the PMS stereotype is the notion that PMS can cause women to spin “out of control,” that is, lose control of themselves in ways that violate the feminine gender role. Self-help books (Chrisler, 2003) and qualitative studies (Cosgrove & Riddle, 2003; Lee, 2002; Swann & Ussher, 1995) provide evidence that women fear that they will lose control of their emotions (e.g., become enraged), their appetites (e.g., eat too much), and their impulses (e.g., voice unacceptable thoughts, hit someone). The ability to remain “in control” is highly valued in most industrialized societies (Martin, 1988), and Van Lange (1991) found that, in addition to believing that they are better than others, people tend to believe that their own behavior is more controllable than others’ behavior. Women with mild (or no) symptoms may believe that they are better able to control themselves than are women with severe symptoms of PMS.

Locus of control (Rotter, 1966) is a popular theory about how people think about what happens to them in their daily lives. Those with internal locus of control believe that they exert sufficient influence on people and things in their environment to control both the good and the bad consequences (i.e., reinforcements, punishments) of their behavior. Those with external locus of control believe that consequences of their behavior have less to do with themselves than with luck, fate, or powerful people or institutions. Although the medical explanations of PMS place its cause within individual women (i.e., because of physiological or biochemical dysfunction), the pattern of dualistic discourse (Jekyll and Hyde, “me/not me,” “my PMS-self/my real self” (Chrisler, 2003; Chrisler & Caplan, 2003; Cosgrove & Riddle, 2003; Swann & Ussher, 1995) that permeates both the self-help literature and women’s explanations of their own behavior suggests that women experience PMS as external, that is, as not part of the self or as a sort of monster that “takes over” and controls the self for several days each month. Thus, women with external locus of control may be more likely to accept the dualistic discourse and more likely to report premenstrual symptoms than those with an internal locus of control. Because the inability to control oneself is perceived negatively by Americans, women with external locus of control may be more likely than those with internal locus of control to believe that most women have PMS.

Optimism refers to a general expectation that one will have good luck, that difficult situations will turn out for the best. Health psychologists (e.g., Sheir & Carver, 1985) have shown that optimism mobilizes people to cope with stressors and that it is associated with better outcomes and adjustment to major stressors, such as illness. Often, however, people are optimistic with little reason to be (e.g., the odds are against them, the situation cannot be controlled by an individual) because of the belief that they are less vulnerable or luckier than other people. It appears not to matter whether people’s optimism is rational or illusory; in either case it is beneficial to physical and mental health (Taylor & Brown, 1988). PMS is itself a stressor, and the severity of its symptoms is associated with women’s stress levels (Beck, Gevirtz, & Mortola, 1990; Gallant, Popiel, Hoffman, Chakraborty, & Hamilton, 1992). Therefore, we might expect women high in optimism to report more mild symptoms of PMS than those low in optimism.

Some early studies (Clarke & Ruble, 1978; Parlee, 1974), which were conducted long before the stereotypical image became ubiquitous, have shown that girls and women believe that others’ premenstrual symptoms are worse than their own. The fundamental error of attribution and the illusory correlation may explain the tendency of the participants in Koeske & Koeske’s (1975) classic study to attribute a vignette character’s negative affect to PMS even when the situation was described as unpleasant. Other than a few studies of PMS as a form of self-handicapping (Bates & Beck, 1991; Mello-Goldner & Jackson, 1999) and as predicted by external locus of control (O’Boyle, Severino, & Hurt, 1988), PMS does not seem to have been actively studied by researchers interested in social cognition. The present study represents a preliminary attempt to consider optimism and the false uniqueness effect in relation to personal symptom reports and beliefs about the incidence of severe PMS. We also examined locus of control as a predictor of both own symptoms and incidence beliefs.

Hypotheses

-

1.

Women high in optimism were expected to report milder premenstrual symptoms than women low in optimism.

-

2.

Women with internal locus of control were expected to report milder premenstrual symptoms than women with external locus of control.

-

3.

The majority of participants were expected to believe that other women’s premenstrual symptoms are worse than their own.

-

4.

The majority of participants were expected to believe that other women are likely to be diagnosed with PMS.

-

5.

The more external a woman’s locus of control, the more likely she was expected to believe that most women have PMS.

Methods

Participants

Participants were 92 undergraduate women from two small colleges in southern New England. They ranged in age from 18 to 48 years (M=22.34, SD=5.62). The majority of the students described themselves as White (78.3%), heterosexual (90.2%), and middle to upper-middle class (80.4%).

Measures

The Life Orientation Test (Scheir & Carver, 1985) is a 10 item measure of optimism. Participants rate each item on a 5-point Likert-type scale that ranges from 1 – strongly disagree to 5 – strongly agree. Sample items include “In uncertain times I usually expect the best” and “If something can go wrong for me it will.” High scores indicate high optimism.

The I-E Scale (Rotter, 1966) is a forced choice measure of locus of control that consists of 29 pairs of items. Participants must choose the one of each pair that best represents their view of the world. A sample pair is “Many of the unhappy things in people’s lives are partly due to bad luck” and “People’s misfortunes result from the mistakes they make.” Scores are computed by counting the number of choices that represent internal and external locus of control.

The Menstrual Distress Questionnaire (Moos, 1968) is a 47 item Likert-type scale that measures the extent to which various signs and symptoms are experienced during three phases of the menstrual cycle. Participants rate each item on a 6-point Likert-type scale that ranges from 1 – no experience of this sign or symptom to 6 – severe and partially disabling experience. The items are divided into eight subscales: Pain (e.g., headache), Concentration (e.g., forgetfulness), Behavior Change (e.g., take naps or stay in bed), Autonomic Reactions (e.g., excitement), Water Retention (e.g., painful or tender breasts), Negative Affect (e.g., crying), and Control (symptoms unassociated with the menstrual cycle per se, e.g., buzzing or ringing in the ears). High scores indicate strong experiences of the symptoms associated with the subscales. The scale was modified for the present study so that only premenstrual ratings were requested. Participants rated their own average experience of each item and then their estimate of the average adult North American woman’s experience of each item.

Participants were furnished with the following definition of PMS: “Premenstrual syndrome (PMS) is characterized by the cyclic recurrence of certain physical, psychological, and behavioral symptoms that begin in the week before menstruation and disappear within a few days of the beginning of the menstrual period. The term PMS is used to describe the experience of symptoms that are severe enough to interfere with a woman’s daily life.” They were then asked five questions, which they answered on a 5-point Likert scale that ranged from 1 – very unlikely to 5 – very likely. The questions were: (1) How likely is it that you could be diagnosed with PMS?; (2) How likely is it that the average woman student at your college could be diagnosed with PMS?; (3) How likely is it that the average woman your age could be diagnosed with PMS?; (4) How likely is it that the average adult woman in the United States could be diagnosed with PMS?; (5) How likely is it that the average woman professor at your college could be diagnosed with PMS? Participants were also asked “What percentage of women in the United States do you think have PMS?”

Procedure

Participants completed the questionnaire packet in small groups. The questionnaires were always presented in the same order: LOT, I-E, MDQ, PMS questions, demographic questions. Participants signed a consent form, which informed them that they could drop out of the study at any time without penalty. Some received course credit for their participation.

Results and Discussion

The median split method was used to divide participants into high and low optimism groups (median=22). Women high in optimism were significantly less likely to believe that they could be diagnosed with PMS, F(1, 83)=6.77, p < .05, and they had significantly lower scores on the pain, F(1, 83) = 4.82, p < .05, and behavior change, F(1, 83)=5.62, p < .05, subscales of the MDQ than did those low in optimism, which provides support for our first hypothesis. The subscales on which women high in optimism differed from women who were low in optimism describe signs and symptoms that may be particularly amenable to the types of problem-focused coping that have been associated with better illness outcomes.

Although others (O’Boyle, Severino, & Hurt, 1988) have found locus of control to predict severity of premenstrual symptoms, there was no support for our second or fifth hypothesis. Locus of control did not differentiate between mild and strong reports of premenstrual symptoms, nor were those with external LOC more likely to believe that other women could be diagnosed with PMS. Perhaps a better way to examine the issues discussed earlier would be to ask women less about their experience of premenstrual changes and more about how they think about those changes and how they cope with them. Perhaps external locus of control manifests itself in the belief that symptoms are less controllable and in a greater tendency to use dualistic discourse.

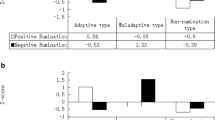

The participants showed a significant tendency to believe that other women’s PMS is worse than their own (false uniqueness effect; see Table 1). They expected that other women’s pain, concentration, behavior change, autonomic reactions, water retention, and negative affect would be worse than their own, which provides strong support for our third hypothesis. Note that all estimates are within the no experience to mild experience range. Although participants believed that other women’s symptoms are worse than their own, they still thought that other women would not be as bad off as the stereotype of premenstrual women suggests is the case.

Estimates of the percentage of women in the United States who have PMS ranged from 5 to 100%; the average estimate was that 62.58% (i.e., the majority) of women in the United States could be diagnosed with premenstrual syndrome. The mean percentage estimate is striking because the definition we provided stated that “the term PMS is used to describe symptoms that are severe enough to interfere with a woman’s daily life” (original emphasis), and experts estimate that only 5–10% of women actually experience debilitating symptoms (Taylor & Colino, 2002). Thus, this may be taken as further evidence of the false uniqueness effect: participants believed that other women’s (severe) symptoms are worse than their own (none to mild) symptoms.

There was little variability among the ratings of how likely the various categories of women were to be diagnosed with PMS. Most were rated as being between three (the midpoint) and four (likely to be diagnosed). Participants rated their own likelihood of diagnosis as 3.40, other women students at their college at 3.41, women professors at their college at 3.42, other women their age at 3.55, and the average adult woman at 3.68. The trend in the ratings seems to be greater likelihood of diagnosis as the targets’ closeness to the participants diminishes. Although the range is narrow, it suggests that participants might feel luckier and less vulnerable to PMS than the average adult woman, who was probably perceived as older than most of our participants. The original plan was to ask “What percent of the following categories of women do you think have PMS?” That question might have been better than the one we asked, as participants could not safely hover around the midpoint.

Conclusion

The results of this study provide support for the theory that self-serving biases help to maintain the cultural stereotype of the premenstrual woman. Participants believed that the average woman’s premenstrual experience on six of the eight subscales of the MDQ is worse that their own experience. The two scales for which the pattern did not hold are arousal (which can be considered positive “symptoms”) and control (which contains symptoms not actually associated with menstruation). Our participants also greatly overestimated the percentage of women whose premenstrual symptoms are severe enough to interfere with daily life, which suggests that they accept the stereotype of premenstrual women even though it does not describe them or the people they know well (e.g., other women students at their college).

Illusory optimism also may play as role, as participants who were higher in optimism rated themselves as less likely to be diagnosed with PMS and as having less pain and exhibiting less behavior change than did those lower in optimism. Our young participants appear to feel luckier and less vulnerable than the average woman and thus less likely to have severe PMS. They may also be exhibiting the false uniqueness effect, in that they see themselves as relatively unusual, which they certainly are if the standard to which they compare themselves is the cultural stereotype.

Although all of our hypotheses were not supported, we did find sufficient evidence to encourage future research on the role of social cognition in the maintenance of the stereotype of premenstrual women. Next steps might include questionnaire or focus group studies to discover which aspects of the stereotype participants accept and which they reject and vignette studies of the social perception of women who exhibit (or admit) premenstrual symptoms.

References

Bates, C. A., & Beck, B. L. (1991, April). PMS as an excuse? The effects of dispositional handicapping, premenstrual syndrome, and success contingency on situational self-handicapping. Poster presented at the meeting of the Eastern Psychological Association, New York.

Beck, L. E., Gevirtz, R., & Mortola, J. F. (1990). The predictive role of psychosocial stress on symptom severity in premenstrual syndrome. Psychosomatic Medicine, 52, 536–543.

Chrisler, J. C. (2002). Hormone hostages: The cultural legacy of PMS as a legal defense. In L. H. Collins, M. R. Dunlap, & J. C. Chrisler (Eds.), Charting a new course for feminist psychology (pp. 238–252). Westport, CT: Praeger.

Chrisler, J. C. (2003, November). How to regain your control and balance: The “pop” approach to PMS. Paper presented at the meeting of the Mid-Atlantic Popular Culture Association, Wilmington, DE.

Chrisler, J. C., & Caplan, P. (2003). The strange case of Dr. Jekyll and Ms. Hyde: How PMS became a cultural phenomenon and a psychiatric disorder. Annual Review of Sex Research, 13, 274–306.

Chrisler, J. C., & Johnston-Robledo, I. (2002). Raging hormones? Feminist perspectives on premenstrual syndrome and postpartum depression. In M. Ballou & L. S. Brown (Eds.), Rethinking mental health and disorder (pp. 174–197). New York: Guilford.

Chrisler, J. C., & Levy, K. B. (1990). The media construct a menstrual monster: A content analysis of PMS articles in the popular press. Women & Health, 16(2), 89–104.

Clarke, A. E., & Ruble, D. N. (1978). Young adolescents’ beliefs concerning menstruation. Child Development, 49, 231–234.

Cosgrove, L., & Riddle, B. (2003). Constructions of femininity and experiences of menstrual distress. Women & Health, 38(3), 37–58.

Festinger, L. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations, 7, 117–140.

Frangipane, D. (1992). Deliverance from PMS. Cedar Rapids, IA: Arrow Publications.

Gallant, S. J., Popiel, D. A., Hoffman, D. M., Chakraborty, P. K., & Hamilton, J. A. (1992). Using daily ratings to confirm premenstrual syndrome/late luteal phase dysphoric disorder II: What makes a “real” difference? Psychosomatic Medicine, 54, 167–181.

Koeske, R. K., & Koeske, G. F. (1975). An attributional approach to moods and the menstrual cycle. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 31, 474–478.

Laws, S. (1983). The sexual politics of premenstrual tension. Women’s Studies International Forum, 6, 19–31.

Lee, S. (2002). Health and sickness: The meaning of menstruation and premenstrual syndrome in women’s lives. Sex Roles, 46, 25–35.

Martin, E. (1988). Premenstrual syndrome: Discipline, work, and anger in late industrial societies. In T. Buckley & A. Gottlieb (Eds.), Blood magic: The anthropology of menstruation (pp. 161–181). Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Mello-Goldner, D., & Jackson, J. (1999). Premenstrual syndrome (PMS) as a self-handicapping strategy. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality, 14, 607–616.

Meyers, D. G. (1996). Social psychology (5th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Monin, B., & Norton, M. I. (2003). Perceptions of a fluid consensus: Uniqueness bias, false consensus, false polarization, and pluralistic ignorance in a water conservation crisis. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29, 559–567.

Moos, R. H. (1968). The development of a Menstrual Distress Questionnaire. Psychosomatic Medicine, 30, 853–867.

O’Boyle, M., Severino, S. K., & Hurt, S. W. (1988). Premenstrual syndrome and locus of control. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine, 18, 67–74.

Parlee, M. B. (1974). Stereotypic beliefs about menstruation: A methodological note on the Moos Menstrual Distress Questionnaire and some new data. Psychosomatic Medicine, 36, 229–240.

Ross, L., Greene, D., & House, P. (1977). The false consensus effect: An egocentric bias in social perception and attribution processes. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 13, 279–301.

Rotter, J. B. (1966). Generalized expectancies for internal vs. external control of reinforcement. Psychological Monographs, 80(1).

Scheir, M. F., & Carver, C. S. (1985). Optimism, coping, and health: Assessment and implications of generalized outcome expectancies. Health Psychology, 4, 219–247.

Sherman, S. J., Presson, C. C., & Chassin, L. (1984). Mechanisms underlying the false consensus effect: The special role of threats to the self. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 10, 127–138.

Suls, J., & Miller, R. L. (Eds.). (1977). Social comparison processes: Theoretical and empirical perspectives. Washington, DC: Hemisphere.

Suls, J., & Wan, C. K. (1987). In search of the false uniqueness phenomenon: Fear and estimates of social consensus. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 211–217.

Swann, C. J., & Ussher, J. M. (1995). A discourse analytic approach to women’s experiences of premenstrual syndrome. Journal of Mental Health, 4, 359–367.

Tabachnik, N., Crocker, J., & Alloy, L. (1983). Depression, social comparison, and the false consensus effect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45, 688–699.

Taylor, D., & Colino, S. (2002). Taking back the month. New York: Penguin.

Taylor, S. E., & Brown, J. D. (1988). Illusion and well-being: A social psychological perspective on mental health. Psychological Bulletin, 103, 193–210.

Van Lange, P. A. M. (1991). Being better but not smarter than others: The Muhammad Ali effect at work in interpersonal situations. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 17, 689–693.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chrisler, J.C., Rose, J.G., Dutch, S.E. et al. The PMS Illusion: Social Cognition Maintains Social Construction. Sex Roles 54, 371–376 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-006-9005-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-006-9005-3