Abstract

Citation analysis has been a prevalent method in the field of information science, especially research on bibliometrics and evaluation, but its validity relies heavily on how the citations are treated. It is essential to study authors’ citing motivations to identify citations with different values and significance. This study applied a meta-synthesis approach to establish a new holistic classification of citation motivations based on previous studies. First, we used a four-step search strategy to identify related articles on authors’ citing motivations. Thirty-eight primary studies were included after the inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied and appraised using the Evidence-based Librarianship checklist. Next, we decoded and recoded the citing motivations found in the included studies, following the standard procedures of meta-synthesis. Thirty-five descriptive concepts of citation motivations emerged, which were then synthesized into 13 analytic themes. As a result, we proposed a comprehensive classification, including two main categories of citing reasons, i.e., “scientific motivations” and “tactical motivations.” Generally, the citations driven by scientific motivations serve as a rhetorical function, while tactical motivations are social or benefit-oriented and not easily captured through text-parsing. Our synthesis contributes to bibliometric and scientific evaluation theory. The synthesized classification also provides a comprehensive and unified annotation schema for citation classification and helps identify the useful mentions of a reference in a citing paper to optimize citation- based measurements.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Citation analysis has been a prevalent method for quantitative scientific evaluation since citation datasets became accessible through the Scientific Citation Index. Most current evaluations of scholars, publications, journals, projects, and institutions are based on citation criteria (e.g., citation counts, journal impact factor, and h index). However, the debate over the application of this approach for evaluating citations is ongoing. According to one camp, the methods used to evaluate citations are already suitable for scientific evaluation, although they hold diverse opinions on what types of scientific results can be assessed by these indices. For example, Shadish et al. (1995) argued that a work with a higher citation count has been used more frequently and has higher impact. Hu et al. (2017) argued that for scientific articles, being highly cited is regarded as a signal of high quality. Tang and Safer (2008) also attached the citation count to the importance of a publication. Nevertheless, Garfield (1979) concluded that people tend to use words, such as “importance” or “impact,” in a pragmatic sense to represent “utility,” when indicating what citation counts could measure.

The other camp doubts the reliability of scientometrics indices since they treat all citations with equal significance and ignore the function of each citation (Zhu et al. 2015). However, not all citations reflect the value of scientific research (Vinkler 1987). For instance, publications could be cited out of politeness, policy, or piety (Ziman 1968). Slipshod, incomplete, or dishonest citation practices, and taking citations at their face value could also lead to errors (Kaplan 1965). Moreover, the contributions of a citation to the citing paper vary across specific motives even if the paper is cited for substantive scientific purposes. For example, papers cited out of a confirmative motive (e.g., praising) can be more valuable than those cited for negational purposes (e.g., criticizing) (Moravcsik and Murugesan 1975). In addition, some work can be over-recognized due to the Matthew effect of citations (Small 2004).

Previous researchers have attempted to discriminate citations using two tracks. One is the syntactic content-based citation analysis (Ding et al. 2014), applying the characteristics of citations such as their locations and frequency with which they are mentioned in a single paper (See reviews of Jones et al. 2012, Ding et al. 2014, and Hernández-Alvarez and Gomez 2016 for more details). These characteristics have been found to play a significant role in assessing citations (e.g., McCain and Turner 1989; Hu et al. 2017; Jones et al. 2012; Jones and Hanney 2016; Ding et al. 2013), and Zhu et al. (2015) concluded that the best assessment was the number of mentions. In addition, some studies have suggested combining the locations and the number of mentions. For example, Zhao and Strotmann (2020) found that researchers can exclude citations in the background and review sections and those mentioned only once in the introduction section, to provide a balance between filtration and error rates.

The other track is semantic content-based citation analysis (Ding et al. 2014), exploring the relationships between documents connected by citations. An essential work of this track is to identify the motives or functions of citations (Ding et al. 2014). Studies on citing motivations can provide “a more subtle and nuanced understanding of quantitative citation analysis” (Erikson and Erlandson 2014, p. 626) and avoid drawing misleading conclusions (Oppenheim 1996). In addition, the motives cannot be fully explained by syntactic features of citations. For example, Thelwall (2019) suggested that “citation counts reveal nothing about the reasons why an article has been cited” and the “head sections are partly unreliable to be used as the citation context” (p. 658). Therefore, it is necessary to investigate the authors’ citing motivations as a complement for the syntactic content-based citation analysis to identify the value of citations.

Early studies related to citation motivations generally relied on observations and analysis of facts or literature (e.g., manually analyze the citation contents) without empirical research on citing behavior (Moravcsik and Murugesan 1975; Oppenheim and Renn 1978; Frost 1979). Interview and postal survey methods have also been applied for citing motivation research (Vinkler 1987; Case and Miller 2011; Fazel and Shi 2015). Recently, machine learning technology such as Support Vector Machine and Convolutional Neural Networks has been employed to conduct the automatic classification of large-scale citations from the perspective of citation functions (Hernández-Alvarez et al. 2017; Bakhti et al. 2018). Although rich results have been found, the various research perspectives have led to considerable differences across studies. Thus, it is necessary to synthesize differences and form a unified interpretation of the citing motivations. Erikson and Erlandson (2014) summarized researchers’ citing practices and presented a taxonomy of citation motivations, including argumentation, social alignment, mercantile alignment, and data. However, applying this coarse-grained typology to analyze the citation content or conduct scientific evaluations may not adequately distinguish the value of citations among the references. A more systematic approach is needed to synthesize and propose a comprehensive classification of reasons for citing.

Research objectives

This study aims to conduct a comprehensive classification of citers’ motivations and illustrate the complexity of citing purposes using the meta-synthesis method. Meta-synthesis, an approach used to analyze and integrate qualitative research, can help researchers synthesize the differences among primary studies, allowing for the construction of a framework for a holistic interpretation that goes beyond the original studies (Finfgeld-Connett 2018). Furthermore, according to Bornmann and Daniel (2008), there is evidence that citers’ motivations are not overly different or “randomly given,” which suggests the theoretical feasibility of synthesizing citation motivations using a meta-synthesis approach. The guiding research questions of this research are as follows.

-

RQ1 What are authors’ motivations to cite?

-

RQ2 What are the characteristics of each type of motivation?

Methodology

Search strategy

We used a four-step strategy to search as many relevant studies as possible. An initial search for articles on citing motivation was conducted in Web of Science (WOS) to identify the search terms, followed by an analysis and recording of words in the titles, abstracts, and keywords. Based on this process, we formed the following search terms: citing reason* OR citation motivation* OR citer motivation* OR citing motives OR citation function OR citation purpose OR citation classif* OR citation taxonomy OR citation typology OR citation behavio* OR citation practice. We also included broader concepts such as “citation behavior” and “citation practice” to identify more related studies.

We then conducted the literature search in August 2019 in six electronic databases reflecting a broad spectrum of citation research: WOS, Elsevier ScienceDirect, Library and Information Science Abstracts, ProQuest Digital Dissertation, China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) and WanFang Data. We further hand-searched reference lists of included articles retrieved from the databases and reviews to conduct a complementary search. In addition, we tracked newly published studies in the field throughout the research to avoid omitting potential articles.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We selected studies if they met the following criteria: (1) research that examined and reported specific citing motivations with clear definitions; (2) primary empirical research that reported the number of samples; (3) research published in English or Chinese; and (4) journal article, conference paper, or thesis. Notably, the inclusion criteria were not restricted to qualitative studies because mixed methods studies can also have a qualitative component related to our topic. For example, the citing reasons listed on a questionnaire are also part of the intellectual results of researchers. The responses to open-ended questions also provide qualitative research findings. In addition, although we included papers investigating both citing motivations and criteria for selecting a specific reference, we focused only on the former. According to Tahamtan and Bornmann (2018), “the connection between the cited and citing document is established by the process from selection to citation. This process is characterized by specific reasons to cite and decision rules of selecting documents for citing” (p. 205). Specifically, citing motivations (i.e., “reasons to cite”) explain authors’ needs of citing in academic writing, while decision rules or criteria are in response to why authors choose a particular paper to cite instead of others. These rules are used for filtering when there are a number of documents that meet the authors’ needs.

Studies were excluded if they only focused on the sentiment or polarity of citations and classified them based on citation forms rather than the citing motivations or reasons. Some automatic classification studies were also excluded if they applied annotation schema completely based on previous research without modification or originality. In addition, a related preprint obtained by hand-searching reference lists was excluded, since it was not peer-reviewed.

Critical Appraisal of the Selected Papers

We used the Evidence-based Librarianship (EBL) Critical Appraisal checklist developed by Glynn (2006) to evaluate the methodological quality of the primary studies included in our study. The checklist, including 26 questions, contains four evaluation aspects of a study: population, data collection, study design, and results. If the validation score of a primary study is higher than 75%, the study is considered reliable. However, it is notable that questions that are specific to a study to be appraised may not be solved by the critical appraisal instrument, and not all the questions in the checklist are applicable to each study (Glynn 2006). For example, in the current meta-synthesis, some of the primary studies included in this research were conducted using citation content analysis or context analysis, so the EBL questions regarding population were irrelevant to those studies.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

We followed the guidance of Finfgeld-Connett (2018) and extracted two types of data from the primary studies: (1) qualitative research findings that constitute the majority of the analyzed data used for subsequent coding and categorizing; and (2) characteristics of primary qualitative research investigations (e.g., purpose, sample, methods) that help investigators become familiar with the sample and help them contextualize the research findings (Finfgeld-Connett 2018). Specifically, we extracted characteristics including the research field, method, number of subjects/papers (samples), and the citing motivations reported in the findings or discussion sections. Notably, we only focused on psychological motivations including the reasons or purposes for why the authors cited rather than the forms of citations (e.g., integral or non-integral).

When conducting a meta-synthesis, it is suggested that researchers work collaboratively to diminish bias and to enhance rigor (Finfgeld-Connett 2018). Thus, three authors of this study systematically evaluated the studies using the following five steps: (1) read, thoroughly investigated, and marked the citing motivations described in the primary research, keeping early codes that were close to the raw data; (2) recorded the citing motivations that were extracted into concise descriptive statements in a formatted coding table—within-study memos; (3) carefully compared the citing motivations discussed in different primary studies, and then gradually synthesized them into a cohesive whole according to their conceptual similarity or relevance using more abstract “metaphors” to define a new category and recording them in cross-study memos; (4) iterated the first three steps reflexively until the concepts of every citing motivation was cohesive and fully explained; and (5) formed a general and comprehensive classification of citing motivations and reported the results.

Results

Study selection

Of the 1771 studies identified, 38 met the inclusion criteria and were critically appraised. Figure 1 shows the selection process. All 38 studies scored over 0.75, indicating that they had high methodological quality and were thus selected as an original study to be synthesized. Characteristics of the 38 studies are described in Table 1. In terms of research methods, 21 studies used citation content or contexts and 17 studies used interviews or a questionnaire to collect relevant data. As for the research area, 17 studies focused on the natural sciences, while 13 studies concentrated on the social sciences. Another 8 studies covered both natural and social sciences. In addition, the majority of the studies first identified the citing articles (or citers), and then analyzed the citation content of each citation (or directly asked the citers about their reasons for citing each reference). In contrast, 5 studies first identified the cited papers, and then analyzed the functions they served in the citing papers.

A reference might be cited more than once in a single paper with different motives. Each mention of a reference might also be driven by multiple motives. Different ways of treating these overlapping issues have been used in the primary studies. For example, some studies, especially those applying automatic classification techniques (e.g., Teufel et al. 2006), analyzed each citation and categorized them into exclusive categories. In these studies, each citation was classified into a category representing the dominant orientation (e.g., Spiegel-Rösing 1977; Shadish et al. 1995). Others assigned each citation to more than one category if there was more than one motive (e.g.,Moravcsik and Murugesan 1975; Fazel and Shi 2015).

Synthesis

A total of 35 descriptive concepts were identified across the primary studies, which were then combined into 13 analytic themes. According to Petrić and Harwood (2013), the motivation to cite is slightly different from the citation functions, which “refer to the rhetorical roles citations perform in the text in which they are located (e.g., to define a term used in the text or to support an idea expressed in the text),” while “motivations tend to have a wider scope and refer to reasons for including a particular source in general (e.g., to show the citer has read a particular source)” (p. 115). Therefore, we clustered the 13 analytic themes into two categories: “scientific motivation” and “tactical motivation.” Scientific motivation refers to the purpose of citing to “acknowledge intellectual and cognitive influences of scientific peers” (Bornmann and Daniel 2008, p. 45). Ten analytic themes were assigned to scientific motivation: Background, Gap, Basis, Comparison, Application, Improvement/Modification, Evidence, Identification of originator, Further reading, and Assessment. Tactical motivation corresponds to non-scientific reasons, such as the social or utilitarian purpose that authors want to achieve through citing practices. Three themes were included in tactical motivation: Subjective norm, Advertising and Profit-seeking. Each theme was supported by several studies ranging from 6 to 28 individual studies, and up to 26 studies supported 5 or more themes.

Scientific motivation

Background

Nearly half of the studies reported that one of the motives for authors to cite is to summarize the general background of the research topic. Authors typically review related works to ensure completeness or the preliminary nature of the topic (Vinkler 1987). They may also directly cite an existing review paper (Case and Higgins 2000; Case and Miller 2011; Shadish et al. 1995) to provide relevant knowledge about the research topic (Shi 2010). This category mainly refers to tracing the history and showing the prevailing or important findings, which are the two most common background motivations. Tracing the history includes depicting the development of work by a researcher or in a field and ideas over time (Harwood 2009; Oppenheim and Renn 1978). In contrast, showing the prevailing findings focuses on the “state of the art of the research question under investigation” (Spiegel-Rösing 1977, p. 105). It helps “identify representatives and exemplars of different viewpoints” (Harwood 2009, p. 505) and also helps “demonstrate the knowledge of the important work” (Bonzi and Snyder 1991, p. 248). Citations showing the prevailing or important findings usually appear in the introduction or related research sections of a paper (Vinkler 1987; Ma and Wu 2009).

Some studies found that citers also refer to other broader information that is not directly related to the current research question. For example, alternative theories or research methods that were not used in the research (Chubin and Moitra 1975; Lipetz 1965; Peritz 1983) or related research in other fields (Peritz 1983) were often cited. Such citations still had particular significance for the focal research (Chubin and Moitra 1975) even though they were not closely connected to the research topic and only offered non-core information.

Gap

The results of 12 studies indicated that authors cited to identify the works that have or have not been conducted in the focal area (Cano 1989; Frost 1979; Moravcsik and Murugesan 1975; White and Wang 1997) to establish a territory for themselves (Fazel and Shi 2015; Kwan and Chan 2014). In particular, Samraj (2013) pointed out that when the citers evaluated the general state of a research area based on a literature review, the research gaps in this area emerged. The clarification of research gaps also provided an explanation for the writer’s own research topic. In other words, another role of the cited literature is to justify the writer’s choice of the topic (Altidor-Brooks 2014; Case and Higgins 2000; Case and Miller 2011; Petrić and Harwood 2013; Shadish et al. 1995).

From the perspective of the structure of scientific papers, after the research gap and research topics are identified, the specific research questions follow. Thus, the motivation to cite in this position is to formulate the current research questions through a series of citations (Kwan and Chan 2014; Peritz 1983; Spiegel-Rösing 1977).

Basis

Fourteen studies reported that the cited literature had outstanding academic contributions to the current research work. The reported contributions can be subdivided into two cases. From a macro perspective, the cited literature was the starting point or the foundation of the focal research (Cano 1989; Moravcsik and Murugesan 1975), which emphasized the global importance of the cited literature. For example, the cited literature strongly influenced the authors’ thinking on the topic and became the main source of their research ideas (Case and Higgins 2000; Case and Miller 2011; Shadish et al. 1995). The authors also used the cited work to use one of the ideas as a stepping-stone to go deeper (Frost 1979), or used it as the intellectual source of their research (Teufel et al. 2006). Sometimes, the focal research was also a continuation of the cited work, since it was almost entirely based on the cited work (Bonzi and Snyder 1991; Vinkler 1987).

In terms of a micro perspective, cited work acted as a key point in the focal research (Shi 2010). For instance, the findings, or argument of the focal work was formed on the basis of arguments in the cited paper (Shi 2010). In addition, “the source of the derivation of a fundamental equation or a detailed description of the experimental conditions” was also cited as the key part of the focal research (Chubin and Moitra 1975, p. 426). Generally, the macro perspective (starting point) focuses on the contribution of the referenced paper to the entire work, while the micro view (key point) concentrates on the critical points.

Comparison

More than half of the studies found that authors cited for comparison purposes, including two types of comparison based on the object with which the cited literature was compared: comparison between one’s own work and the cited work, and comparison between or among cited works. A total of 22 studies had a comparison of cited work with the focal research, of which 9 studies elaborated on the comparison of their findings to illustrate the consistency or contradiction (Altidor-Brooks 2014; Case and Higgins 2000; Case and Miller 2011; Kwan and Chan 2014; Mansourizadeh and Ahmad 2011; Petrić 2007; Shadish et al. 1995; Spiegel-Rösing 1977). For example, the results of an experiment using a theoretical equation were compared with the derivation of that equation in the referenced paper (Oppenheim and Renn 1978). Citations for comparison were typically in the findings section (Petrić 2007). Other components, such as research methods (Cano 1989; Moravcsik and Murugesan 1975; Teufel et al. 2006), areas (Harwood 2009), concepts (White and Wang 1997), algorithms (Tuarob et al. 2013), and experimental data (Spiegel-Rösing 1977) from the cited work were used for comparison to point out the disadvantages in the cited work, and thereby emphasize the advantages of the citing work. Nevertheless, these comparisons were sometimes used to simply indicate the similarities or differences between the two studies.

Five studies focused on a comparison of several cited works to establish links among the sources. The contents that were compared included research methods (Teufel et al., 2006), research areas, findings (Mansourizadeh and Ahmad 2011), and academic opinions (Petrić 2007). In some cases, two or more cited works were listed after the same statement in the citing works.

Application

Twenty-three studies mentioned that citers directly employed a method or technique of cited work for calculation purposes, including the application of instruments (Peritz 1983), analysis methods (Chang 2013; Hernández-Alvarez et al. 2017), algorithms (Tuarob et al. 2013), and equations (Oppenheim and Renn 1978). This type of motivation refers to the “unchanged use” of the tools proposed by the cited authors (Teufel et al. 2006) rather than the modification, optimization (Tuarob et al. 2013), or comparison of the cited work (Oppenheim and Renn 1978).

Another 9 studies found that the cited literature was used as a data source, i.e., the citers utilized the data contained in the cited literature (Bakhti et al. 2018; Hernández-Alvarez et al. 2017; Oppenheim and Renn 1978; Spiegel-Rösing 1977; Tang and Safer 2008; Teufel et al. 2006; Wang et al. 2016) and conducted subsequent testing and analysis. For example, the cited work was a statistical report and the citers used the original statistical data (White and Wang 1997). The experimental results in the cited literature were also used as the raw data for secondary research such as a meta-analysis.

Improvement/modification

Except for “unchanged use,” 7 studies reported that one of the citing motivations was to “use with adaptations.” Specifically, the citers adapted or expanded the method such as an algorithm or experimental technique introduced in the cited study. In addition, the referenced work was sometimes cited for data adjustment, such as changing the precision or the scope of an application (plus or minus) (Lipetz 1965).

Evidence

Using the cited works as evidence to support the current research was one of the most common citing motivations. There are five main types of evidence. The first one is to support the opinion/claim/hypothesis of the citers. For example, citations were used to support the formulation of new hypotheses and conjectures tested in the citing work (Peritz 1983). It has also been reported that citations can support “an opinion or factual statement on the specific literary that author(s) or work(s) discussed in the citing work” (Frost 1979, p. 405). In some cases, citations were used to “help define or explain a concept or approach” (Altidor-Brooks 2014, p. 36).

Another type of evidence motivation is to justify the research design. For example, citers offered factual information to justify some methodological decisions through references (Peritz 1983), and they also used citations in the experiment section “to provide support for the procedures and the materials used in the study” (Mansourizadeh and Ahmad 2011, p. 155).

Cited works were also used to explain or substantiate the findings of the focal study, which usually appeared in the discussion section of a paper. Authors tended to “draw on previous research to interpret their findings or to provide support for interpretations of their findings” (Samraj 2013, p. 305), especially unexpected findings. In addition, citations have also been used “to qualify the acceptability/validity of a numerical result” (Kwan and Chan 2014, p. 37).

Several studies reported that citers used the references to alleviate limitations or highlight the contributions of the focal study (Kwan and Chan 2014; Tang and Safer 2008) or support suggestions for further research, i.e., justifying the research recommendations given in the citing research (Kwan and Chan 2014; Peritz 1983; Samraj 2013; Tang and Safer 2008; Tuarob et al. 2013). Scholars, such as Thompson (2001) and Petrić (2007), also found that citations driven by evidence motivations often presented distinctive linguistic features such as “for example” or “e.g.,” especially when they were used as exemplification.

Identification of the originator

We coded the citing motivation of identification of the originators from 13 studies and found that this type of citation has been used for different purposes. Six studies mentioned that the use of a specific reference was to identify the original publications in which the idea, concept, or method first appeared (Chang 2013; Frost 1979; Ma and Wu 2009; Thompson 2001), such as “Griffith’s law” (Oppenheim and Renn 1978). White and Wang (1997) also argued that “participants considered this type of citation important in documenting earlier attention to the acknowledged idea, in part to indicate the long-term importance of the concept, theory or analytical approach he was using” (p. 131).

Another purpose for citing the original work is to pay homage to pioneers. For example, Oppenheim and Renn (1978) stated that “the references…that the author of the cited paper was the first person to work in the field, that is, those which are simply paying homage to pioneers” (p. 226). Apart from showing respect for the pioneers, original work has also been cited to show respect to “great predecessors of prestigious contemporaries” (Vinkler 1987, p. 64) and to those who have been widely cited (Wang et al. 2016).

Some studies also analyzed the purpose of acknowledging priority. For example, citations were used to acknowledge terms, ideas, or methods in the cited works to clarify their priority (Altidor-Brooks 2014; Bonzi and Snyder, 1991; Harwood 2009; Ma and Wu 2009; Petrić 2007). Frost (1979) also stated that “the citation explicitly acknowledges intellectual indebtedness to a cited work or states that the cited work has been of particular value” (p. 408). Harwood (2009) noted that “this debt was sometimes expressed in terms of ‘paying respect’ to the sources, at other times informants foreground a ‘self-defence’ motivation, the citation making clear they, the citer, are not claiming to be the originator of the citee’s concept” (p. 504).

Further reading

A few studies reported another type of citing motivation is to highlight “further reading.” Generally, the citations referred the readers to further reading material, which was usually located in parentheses or a footnote, preceded by “see” (Brooks 1985; Chang 2013; Petrić 2007; Thompson 2001). This type of citation can be separated into three purposes. The first is alerting the reader to new and different sources to highlight other relevant and interesting papers (Brooks 1986; Harwood 2009). The citations also referred readers to more complete details. For instance, to indicate the “complete descriptions of the body of data used or (more rarely) to data which are submitted to secondary analysis” (Peritz 1983, p. 305). The last purpose of using this type of citation was to save space (Harwood 2009). Mansourizadeh and Ahmad (2011) pointed out that further reading citations “allow the author to be concise especially where there is limited space to include all the information” (p. 155).

Assessment

Most studies mentioned the motivation of assessing the cited research, namely, expressing the citer’s opinions on the ideas, statements, methods, or findings of the cited works. This type of citation can be used to “strengthen either the positive or negative evaluation presented” (Samraj 2013, p. 306). According to the evaluation results, these citations could be divided into three groups: to criticize, affirm the cited works, or show a mixed opinion.

Twenty-five studies claimed that the motivation of citers was to criticize the cited works to varying degrees. For example, citers referred to previous papers to dispute the data (Spiegel-Rösing 1977) or findings (Case and Higgins 2000; Case and Miller 2011; Shadish et al. 1995), express their own disagreement with a previous opinion or statement (Altidor-Brooks 2014; Frost 1979; Ma and Wu 2009; Petrić 2007), identify the limitations of a method/procedure (Harwood 2009; Hernández-Alvarez et al. 2017; Oppenheim and Renn 1978; Teufel et al. 2006), point out inaccuracies in a cited work (Cano 1989; Moravcsik and Murugesan 1975; Vinkler 1987) and sometimes to correct errors (Bonzi and Snyder 1991; Brooks 1985; Chubin and Moitra 1975; Tang and Safer 2008). In particular, Harwood (2009) stated that “a ‘mild’ engaging citation may appear when authors simply argue that an otherwise excellent source suffers from a minor flaw; the harsher type identifies a more serious flaw or may even baldly state that the source is wrong” (p. 506).

Similar to the critical motivation, citers show affirmed evaluation in two aspects. One is to claim the correctness or strengths of the cited work (Cano 1989; Moravcsik and Murugesan 1975), e.g., giving positive credit to the material in the references (Brooks 1985) and the other is to express agreement with the argument/idea of the citers (Petrić 2007).

Frost (1979) and Wang et al. (2016) also found a mixed opinion of the citing authors to the cited work, e.g., “the citing author identifies a statement about which he has a mixed opinion; he agrees with the cited work only to a point or accepts another's work with some reservations” (Frost 1979, p. 409).

Tactical motivation

Subjective norm

According to the findings of several studies that examined the citing motivations of students, it was critical for them to conform to the lecturer’s expectations (Chang 2013). Therefore, students tended to follow the professors’ suggestion (Altidor-Brooks 2014; Fazel and Shi 2015) and choose a source that they believed the lecturer required, preferred, or considered important (Petrić and Harwood 2013; Shi 2010), although sometimes they did not read the source carefully (Fazel and Shi 2015).

Ma and Wu (2009) also found that the citers cited specific literature to meet the “requirements of scientific journal editors” or to “increase the impact factor of the journal” (p. 39). In some cases, the citing authors reportedly felt the stress from self-constraint due to the perception of an academic norm or responsibility. For example, “the participants felt the need to cite these papers not because the papers directly contributed to their research but because they felt a responsibility to alert readers to other literature” (White and Wang 1997, p. 131), and thus, they cited to prevent an accusation of plagiarism (Petrić and Harwood 2013). We generalized these motivations as a “subject norm,” because these motivations involve self-perceived pressure from teachers, journal editors, reviewers, and readers, which resonate with the definition of subjective norms in the theory of reasoned action (Ajzen 1991).

Advertising

Advertising motivation includes claiming one’s own competence and publicly promoting the cited works. Seven studies reported that citers cited a work to display their knowledge of the research field, their ability to conduct research, and that their studies or they themselves were concerned with the newest and most important topic in the area. For example, references were cited “to claim competence by aligning oneself with other researchers or citing one's own previous research…where writers highlight their capability to carry out the proposed research and suitability for receiving the grant” (Fazel and Shi 2015, p. 210).

A few other studies found that the citing authors hoped to make readers aware of earlier works (Harwood 2009) that were sometimes useful but “poorly disseminated, poorly indexed, or never cited” (Ma and Wu 2009, p. 33). For example, Wang et al. (2016) reported that the “author calls on others to test or otherwise more critically evaluate Butler (1980)” (p. 2). However, since the cited work was one of the studies of the citing authors, they wanted to publicize the cited paper (Vinkler 1987) and establish their own authority (Bonzi and Snyder 1991).

Profit-seeking

We identified other purposes including expecting to obtain a professional or personal benefit as a profit-seeking motivation. Several studies suggested that citing authors adopt specific citation strategies to increase the possibility of their own papers being accepted (speculation). For example, “it is difficult for manuscripts to get published without any references or with too few references” (Ma and Wu 2009, p. 39). Therefore, authors may include more references which are, in fact, not necessary (Vinkler 1987). Citing authors may also expect to attract the “attention of a cited author (who happens to be the editor of an important journal)” (Vinkler 1987, p. 64) by citing his/her own works.

Four studies pointed out that one of the citing motivations of authors is to mask that they are unfamiliar with the knowledge in the field, by (1) citing famous and authoritative works (Fazel and Shi 2015; Petrić and Harwood 2013); (2) citing works that have been cited by others (Vinkler 1987); and (3) emulating other writers (Fazel and Shi 2015). For example, “references are made because of no other reason than an unspecified and vague perception of a consensus in a field of study…we make some citations because we think our colleagues think they are important and we want to show we know that” (Brooks 1985, p. 226).

Another few studies mentioned that the citation purpose is social contact. For example, citations were made because “the cited paper was written by persons on whom you depend in some way (professionally, financially, etc.)” (Vinkler 1987, p. 55), and for the purpose of “showing friendship to the cited author” (Ma and Wu 2009, p. 39). This type of motivation was particularly significant when the citing author relied on the cited writer for professional or economic reasons (Vinkler 1987).

Finally, there were some more direct citations. For example, the authors cited their previous work to “increase the citation count of one’s own work” (Ma and Wu 2009, p. 39).

Discussion

Research methods

The related research on citing motivation has used the citation content, context, or textual analysis to investigate and code the reasons authors cite, by analyzing and interpreting the rhetorical function of citations related to the specific position of papers. However, it is challenging to precisely capture the real intention for citing based on the text because the text may not transparently and clearly reflect the citing motivation of the authors (Petrić and Harwood 2013). Therefore, the conclusions may be somewhat subjective (Prabha 1983). For instance, the “miscitation” category of citers’ motivation proposed by Wang et al. (2016) was defined because the citing author did not cite anything that was actually contained in the cited work. This is a typical case that makes it difficult for coders to find a direct link between the cited and citing works, and hence, they do not to know the real citing purpose of the citers based on the text. Some citations may also be used for tactical purposes, which are opaque and ambiguous in the text. The existence of “neutral” or “other” categories in some primary studies (Petrić 2007; Teufel et al. 2006) support the limitation of applying citation content/context or textual analysis because the researchers in these studies cannot differentiate what functions the citations have only based on the obscure relationship between the citing sentences and citations.

Directly asking the authors why they cited using a self-report questionnaire or face-to-face interviews is considered a more accurate method to identify citing motivations (Taşkın and Al 2018). Not only can it alleviate the risk of being overly subjective, but it can also capture more non-scientific (e.g., social or economic purpose) and authentic motivations. Nevertheless, it has some limitations. Bonzi and Snyder (1991) and Shadish et al. (1995) listed the motivations of “political pressure” and to “raise the citation count” as well as 4 types of “citations for social reasons” in the questionnaires, but none of the participants admitted to these citing motivations.

These cases reveal two limitations of applying the survey method to investigating citing motive. The first one is the honesty of respondents when they are answering. Bonzi and Snyder (1991) believed that it is not surprising that none of the participants chose to admit such motivations because given the unflattering nature of these motivations, respondents are unlikely to reveal their true motivations even though they may be aware that they had such motivations. The participants may also avoid responding to the motivation of “demonstrating knowledge” out of modesty (Bonzi and Snyder 1991). The risk of subjects’ dishonest answers is more serious in face-to-face interviews than in anonymous questionnaire surveys (Case and Higgins 2000), because the participants might be influenced by the “familiar narrative constructs” when commenting on their citation contents. For example, “some students might have hesitated to comment on their textual borrowing for fear that the interviewer would disagree with their citation practices” (Shi 2010, p. 22). The other limitation is the risk of lacking completeness and exhaustiveness of motivations. For example, to avoid material omission, Bonzi and Snyder (1991) even listed some motivations that were not easy to access in a questionnaire.

The accuracy of participants’ recall is also affected by time. The motives for citations obtained through questionnaires or interviews are the result of retrospective descriptions of respondents. Therefore, they might fail to fully and accurately remember the reasons for citing due to the time difference between the citing decision and data collection. Considering the timing of data collection, White and Wang (1997) conducted interviews as soon after publication as possible. A similar strategy was adopted by Fazel and Shi (2015). Instead of conducting post-decision research, it would be better to go deep into the interviewee's writing process to reveal the authentic motivation of the citer in a behavioral-observation way.

Tactical motivation

Tactical motivations are socially and beneficially oriented so corresponding citations might have no substantial contribution to the citing research, except for citations that have more than one function. Take students for example. Petrić and Harwood (2013) stated that “grounded in reading around the topic” and “showing knowledge of the literature” are key features of “a good essay”; thus, students may cite many references to be in line with the lecturers’ expectations to ensure a high score. In addition, Fazel and Shi (2015) focused on the citation behavior of doctoral students in grant writing and found that their citation behavior represented their emerging scholarly identity. As academic newcomers, they are not yet equipped with the same academic writing savvy and prowess as established scholars. Therefore, they may tend to rely on or resort to various schemes to package themseleves.

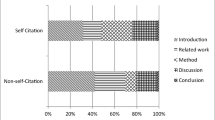

Some tactical motivations are also related to self-citations, including self-promotion, claiming knowledge, and increasing one’s own citation count. A few scholars show a negative attitude towards self-citations, because they make citation-based scientific evaluation indicators easy to manipulate. For instance, Taşkın and Al (2018) identified three cases of academic misconduct that are often exposed due to a high self-citation rate. Boyack et al. (2018) found that self-citing papers were likely to be mentioned multiple times in the citing work. Lievers and Pilkey (2012) also concluded that self-citations would increase the frequency, which measures the general degree of any reference that might be cited N or more times within a single document. As for journals, Tasy (2006) found that a journal with a higher self-citing rate was inclined to be cited more by itself, which shows a positive circle effect. Therefore, self-citations are thought to undermine the validity of citation evaluations. As a result, Shadish (1995) deliberately excluded self-citations when analyzing citing motivations. However, self-citations are an inappreciable threat. For example, Garfield (1979) claimed that it is impossible to inflate one’s citation count through self-citations without being conspicuous, given the strict referee system of journals today and the abnormally high self-citation count that is easily identified. Glänzel and Thijs (2004) also revealed that only a small part of the increase of overall citation counts could be due to self-ciations. Moreover, there is a certain inevitability to self-citation for researchers, because “as time passes a researcher’s output resembles an inverted pyramid. If you are a major contributor, it’s difficult to avoid citing yourself” (Bonzi and Snyder 1991, p. 251). In addition, self-citations make up a large propotion of the cited papers that are of central importance to the citing paper (Jones et al. 2016).

The existence of a non-scientific tactical citing motivation does not imply the lack of value of citation analysis. According to the handicap principle (Nicolaisen 2007), citers would honestly credit their ideas to the sources to a tolerable degree to keep the scientific communication system from collapsing. Studies have also confirmed that only a small portion of citations are made based on tactical motivations (Vinkler 1987). Tactical motivations are usually ignored in existing research on automatic citation classification, given the small portion and the characteristics of this type of motivation that are not easily identified, especially by third-party researchers. Nevertheless, tactical motivations can be applied when large corpus annotated by citing authors is available.

Citation string

A “citation string” is a common citation form. It is manifested as a group of references sharing the same citation context. We labeled this form of citation a “citation string.” For instance:

It is often mentioned in migration studies that the loss of the breadwinner role deteriorates men’s status within the family and community (Al-Ali 2002; Kibria 1990; Matsuoka and Sorenson 1999; McSpadden 1999) (Petrić 2007, p. 246).

The citing reasons for a citation string can be interpreted from two perspectives. As for the individual reference in a citation string, the citing motivation could be any category synthesized in the study, such as describing the background of the research topic, supporting one’s argument, and comparing findings with other studies. In terms of the citing functions of a citation string, the motivation may be establishing a link among the cited works (Mansourizadeh and Ahmad 2011; Petrić 2007), i.e., establishing a connection between an individual work and similar research topics, arguments, or findings.

Scholars hold different opinions about citation strings. For example, Chubin and Moitra (1975) defined it as a “perfunctory citation” because citations in a string have no additional comment. It is also believed that this form of citations only shows that there is related work in the field. These citations are considered redundant since citations are cited due to their mere existence but not necessarily because they contribute to the progress of science (Moravcsik and Murugesan 1975). However, Petrić (2007) noted that this type of citation attests to the author’s ability to detect common knowledge in the field. Similarly, Mansourizadeh and Ahmad (2011) argued that it allows writers to show their competence in the area and thus strengthen the acceptability of their statements. Therefore, it is interesting and meaningful to further investigate the overall citing motivations of citation strings and their value in evaluating scientific works.

Conclusion

This research utilized meta-synthesis to synthesize the findings of 38 primary studies related to citing motivations. Focusing on the citing stage in the process of citation practices, we analyzed two main types of motivations, “scientific motivations” and “tactical motivations,” both of which included several subcategories. Citations driven by scientific motivations usually serve as rhetorical functions in the text, while tactical motivations are social or profit-oriented and are not easily identified through text parsing.

This study is one of the first attempts to apply meta-synthesis to integrate authors’ motivations to cite. We proposed a comprehensive and general classification model of citing motivations, which has both theoretical and practical implications. Our classification supports the basis for subsequent theoretical reasoning on citing practices and provides new insights for the development of evaluation theory. Our classification can also be adopted as a tool for empirical studies. For example, the synthesized framework could provide a comprehensive annotation schema for automatic citation classification. Furthermore, empirical studies are encouraged to distinguish the value of citations (e.g., importance and impact) according to the different types of motivations.

One of the limitations of our study is that we only included the primary studies published in English and Chinese due to the researchers’ restricted language proficiency in other languages, which partly results in the omission of broader research samples. Our study is also limited by the details reported in the primary studies, the findings of which compose our analyzed data.

We propose several directions for future research: (1) investigate why authors use citation strings; (2) explore the distribution of each type of motivation; and (3) provide a more targeted typology of motivations for different disciplines or subgroups, guided by our classification. We also suggest that researchers pay attention to the following two aspects when undertaking an empirical study: (1) fully evaluate the accessible research conditions and choose an appropriate method with a reasonable research design; and (2) investigate the selection criteria of references and citing motivations separately instead of mixing them.

References

Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior & Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T.

Altidor-Brooks, A. G. (2014). Citation use and identity construction: Discourse appropriation in advanced academic literacy practices (Order No. 1603891). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global A&I: The Humanities and Social Sciences Collection. (1739002297). https://search.proquest.com/docview/1739002297?accountid=41288

Bakhti, K., Niu, Z., Nyamawe, A. S. (2018). A new scheme for citation classification based on convolutional neural networks. In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Software Engineering and Knowledge Engineering. doi: https://doi.org/10.18293/SEKE2018-141

Bonzi, S., & Snyder, H. W. (1991). Motivations for citation: A comparison of self citation and citation to others. Scientometrics, 21(2), 245–254. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02017571.

Bornmann, L., & Daniel, H. D. (2008). What do citation counts measure? A review of studies on citing behavior. Journal of Documentation, 64(1), 45–80. https://doi.org/10.1108/00220410810844150.

Boyack, K. W., Van Eck, N. J., Colavizza, G., & Waltman, L. (2018). Characterizing in-text citations in scientific articles: A large-scale analysis. Journal of Informetrics, 12(1), 59–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2017.11.005.

Brooks, T. A. (1985). Private acts and public objects: An investigation of citer motivations. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 36(4), 223–229. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.4630360402.

Brooks, T. A. (1986). Evidence of complex citer motivations. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 37(1), 34–36. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.4630370106.

Cano, V. (1989). Citation behavior: Classification, utility, and location. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 40(4), 284–290. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-4571(198907)40:4%3c284::AID-ASI10%3e3.0.CO;2-Z.

Case, D. O., & Higgins, G. M. (2000). How can we investigate citation behavior? A study of reasons for citing literature in communication. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 51(7), 635–645. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-4571(2000)51:7%3c635::AID-ASI6%3e3.0.CO;2-H.

Case, D. O., & Miller, J. B. (2011). Do bibliometricians cite differently from other scholars? Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 62(3), 421–431. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.21466.

Chang, Y. W. (2013). The influence of Taylor’s paper, question-negotiation and information-seeking in Libraries. Information Processing and Management, 49(5), 983–994. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ipm.2013.03.003.

Chubin, D. E., & Moitra, S. D. (1975). Content analysis of references: Adjunct or alternative to citation counting? Social Studies of Science, 5(4), 423–441. https://doi.org/10.1177/030631277500500403.

Ding, Y., Liu, X., Guo, C., & Cronin, B. (2013). The distribution of references across texts: Some implications for citation analysis. Journal of Informetrics, 7(3), 583–592. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2013.03.003.

Ding, Y., Zhang, G., Chambers, T., Song, M., Wang, X., & Zhai, C. (2014). Content-based citation analysis: The next generation of citation analysis. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 65(9), 1820–1833. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.23256.

Erikson, M. G., & Erlandson, P. (2014). A taxonomy of motives to cite. Social Studies of Science, 44(4), 625–637. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312714522871.

Fazel, I., & Shi, L. (2015). Citation behaviors of graduate students in grant proposal writing. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 20, 203–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2015.10.002.

Finfgeld-Connett, D. (2018). A guide to qualitative meta-synthesis. NewYork: Routledge.

Frost, C. O. (1979). The use of citations in literary research: A preliminary classification of citation functions. The Library Quarterly, 49(4), 399–414. https://doi.org/10.1086/600930.

Garfield, E. (1979). Is citation analysis a legitimate evaluation tool? Scientometrics, 1(4), 359–375. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02019306.

Glänzel, W., & Thijs, B. (2004). Does co-authorship inflate the share of self-citations? Scientometrics, 61(3), 395–404. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:SCIE.0000045117.13348.b1.

Glynn, L. (2006). A critical appraisal tool for library and information research. Library Hi Tech, 24(3), 387–399. https://doi.org/10.1108/07378830610692154.

Harwood, N. (2009). An interview-based study of the functions of citations in academic writing across two disciplines. Journal of Pragmatics, 41(3), 497–518. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2008.06.001.

Hernández-Alvarez, M., & Gomez, J. M. (2016). Survey about citation context analysis: Tasks, techniques, and resources. Natural Language Engineering, 22(3), 327–349. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1351324915000388.

Hernández-Alvarez, M., Gomez Soriano, J. M., & Martínez-Barco, P. (2017). Citation function, polarity and influence classification. Natural Language Engineering, 23(4), 561–588. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1351324916000346.

Hu, Z., Lin, G., Sun, T., & Hou, H. (2017). Understanding multiply mentioned references. Journal of Informetrics, 11(4), 948–958. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2017.08.004.

Jha, R., Jbara, A., Qazvinian, V., & Radev, D. (2017). NLP-driven citation analysis for scientometrics. Natural Language Engineering, 23(1), 93–130. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1351324915000443.

Jones, T. H., Donovan, C., & Hanney, S. (2012). Tracing the wider impacts of biomedical research: A literature search to develop a novel citation categorisation technique. Scientometrics, 93(1), 125–134. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-012-0642-8.

Jones, T. H., & Hanney, S. (2016). Tracing the indirect societal impacts of biomedical research: Development and piloting of a technique based on citations. Scientometrics, 107(3), 975–1003. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-016-1895-4.

Kaplan, N. (1965). The norms of citation behavior: Prolegomena to the footnote. American Documentation, 16(3), 179–184. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.5090160305.

Kwan, B. S. C., & Chan, H. (2014). An investigation of source use in the results and the closing sections of empirical articles in Information systems: In search of a functional-semantic citation typology for pedagogical purposes. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 14, 29–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2013.11.004.

Lievers, W. B., & Pilkey, A. K. (2012). Characterizing the frequency of repeated citations: The effects of journal, subject area, and self-citation. Information Processing & Management, 48(6), 1116–1123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ipm.2012.01.009.

Lin, C. S. (2018). An analysis of citation functions in the humanities and social sciences research from the perspective of problematic citation analysis assumptions. Scientometrics, 116(2), 797–813. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-018-2770-2.

Lin, C. S., Chen, Y. F., & Chang, C. Y. (2013). Citation functions in social sciences and humanities: Preliminary results from a citation context analysis of Taiwan’s history research journals. Proceedings of the ASIST Annual Meeting. https://doi.org/10.1002/meet.14505001134.

Lipetz, B. A. (1965). Improvement of the selectivity of citation indexes to science literature through inclusion of citation relationship indicators. American Documentation, 16(2), 81–90. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.5090160207.

Liu, M. (1993). A study of citing motivations of Chinese scientists. Journal of Information Science, 19(1), 13–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/016555159301900103.

Ma, F., & Wu, Y. S. (2009). A survey study on motivations for citation. Journal of Intelligence, 28(6), 9–14.

Mansourizadeh, K., & Ahmad, U. K. (2011). Citation practices among non-native expert and novice scientific writers. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 10(3), 152–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2011.03.004.

McCain, K. W., & Turner, K. (1989). Citation context analysis and aging patterns of journal articles in molecular genetics. Scientometrics, 17, 127–163. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02017729.

Moravcsik, M. J., & Murugesan, P. (1975). Some results on the function and quality of citations. Social Studies of Science, 5(1), 86–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/030631277500500106.

Nicolaisen, J. (2007). Citation analysis. Annual Review of Information Science and Technology, 41(1), 609–641. https://doi.org/10.1002/aris.2007.1440410120.

Oppenheim, C. (1996). Do citations count? Citation indexing and the research assessment exercise (RAE). Serials, 9(2), 155–161.

Oppenheim, C., & Renn, S. P. (1978). Highly cited old papers and the reasons why they continue to be cited. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 29(5), 225–231. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.4630290504.

Peritz, B. C. (1983). A classification of citation roles for the social sciences and related fields. Scientometrics, 5(5), 303–312. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02147226.

Petrić, B. (2007). Rhetorical functions of citations in high- and low-rated master’s theses. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 6(3), 238–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2007.09.002.

Petrić, B., & Harwood, N. (2013). Task requirements, task representation, and self-reported citation functions: An exploratory study of a successful L2 student’s writing. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 12(2), 110–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2013.01.002.

Prabha, C. G. (1983). Some aspects of citation behavior: A pilot-study in business administration. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 34(3), 202–206. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.4630340305.

Samraj, B. (2013). Form and function of citations in discussion sections of master’s theses and research articles. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 12(4), 299–310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2013.09.001.

Shadish, W. R., Tolliver, D., Gray, M., & Gupta, S. K. S. (1995). Author judgements about works they cite: Three studies from psychology journals. Social Studies of Science, 25(3), 477–498. https://doi.org/10.1177/030631295025003003.

Shi, L. (2010). Textual appropriation and citing behaviors of university undergraduates. Applied Linguistics, 31(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amn045.

Small, H. (2004). On the shoulders of robert merton: Towards a normative theory of citation. Scientometrics, 60(1), 71–79. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:SCIE.0000027310.68393.bc.

Spiegel-Rösing, I. (1977). Science studies: Bibliometric and content analysis. Social Studies of Science, 7(1), 97–113. https://doi.org/10.1177/030631277700700111.

Tahamtan, I., & Bornmann, L. (2018). Core elements in the process of citing publications: Conceptual overview of the literature. Journal of Informetrics, 12(1), 203–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2018.01.002.

Tang, R., & Safer, M. A. (2008). Author-rated importance of cited references in biology and psychology publications. Journal of Documentation, 64(2), 246–272. https://doi.org/10.1108/00220410810858047.

Taşkın, Z., & Al, U. (2018). A content-based citation analysis study based on text categorization. Scientometrics, 114(1), 335–357. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-017-2560-2.

Tasy, M. Y. (2006). Journal self-citation study for semiconductor literature: Synchronous and diachronous approach. Information Processing and Management, 42(6), 1567–1577. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ipm.2006.03.020.

Teufel, S., Siddharthan, A., & Tidhar, D. (2006). Automatic classification of citation function. In: Proceedings of the Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing.

Thelwall, M. (2019). Should citations be counted separately from each originating section? Journal of Informetrics, 13(2), 658–678. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2019.03.009.

Thompson, P. (2001). A pedagogically-motivated corpus-based examination of PhD theses: Macrostructure, citation practices and uses of modal verbs (Order No. U148090). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global A&I: The Humanities and Social Sciences Collection. (301595734). https://search.proquest.com/docview/301595734?accountid=41288

Tuarob, S., Mitra, P., & Giles, C. L. (2013). A classification scheme for algorithm citation function in scholarly works. Proceedings of the ACM/IEEE Joint Conference on Digital Libraries. https://doi.org/10.1145/2467696.2467754.

Vinkler, P. (1987). A quasi-quantitative citation model. Scientometrics, 12, 47–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02016689.

Wang, X., Weaver, D. B., Li, X., & Zhang, Y. (2016). In Butler (1980) we trust? Typology of citer motivations. Annals of Tourism Research, 61, 213–267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2016.07.004.

White, M. D., & Wang, P. (1997). A qualitative study of citing behavior: Contributions, criteria, and metalevel documentation concerns. Library Quarterly, 67(2), 122–154. https://doi.org/10.1086/629929.

Zhao, D., & Strotmann, A. (2020). Deep and narrow impact: Introducing location filtered citation counting. Scientometrics, 122(1), 503–517. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-019-03280-z.

Zhu, X., Turney, P., Lemire, D., & Vellino, A. (2015). Measuring academic influence: Not all citations are equal. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 66(2), 408–427. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.23179.

Ziman, J. M. (1968). Public knowledge: An essay concerning the social dimension of science. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Social Science Foundation of China Grant (17BTQ014).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author have declared no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lyu, D., Ruan, X., Xie, J. et al. The classification of citing motivations: a meta-synthesis. Scientometrics 126, 3243–3264 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-021-03908-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-021-03908-z