Abstract

Retracted publications are a crucial, yet overlooked, issue in the scientific community. The purpose of this study was to analyze the prevalence, characteristics and reasons of Malaysian retracted papers. The Web of Science and Scopus databases were queried to identify Malaysian retracted publications. Available versions of original articles and publication notices were accessed from journal websites. The publications were assessed for various characteristics, including reason for retraction, based on the Committee on Publication Ethics guidelines, and the authority calling for the retractions. From 2009 to June 2017, 125 Malaysian publications comprising (33 journal articles and 92 conference papers) were retracted. There was a spike in the prevalence of retracted articles in 2010 and 2012 with 42 articles (33.6%) and 41 articles (32.8%) respectively from the 125 retracted articles. The mean time from electronic publication to retraction was 1 year. There is no significant relationship between a journal quartile and the mean number of months to retraction (P = 0.842). The reason for retraction for conference papers was specified as “violation of publication principle”. Journal articles were retracted mainly for duplicate publication, plagiarism, compromised peer review process, and self-plagiarism. Most retracted articles do not contain flawed data; and only 2 retracted articles have been accused of scientific mistakes. The study concludes that retractions were mostly due to the authors misconduct. Despite the increases, the proportion of published scholarly literature affected by retraction remains very small, indicating that retraction represents an uncommon, yet potentially increasing and incipient, issue within Malaysian papers, which publishers as well as editors may have consistently and sufficiently addressed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In scholarly communication, a retraction. i.e. “the removal from the literature of a paper determined to be sufficiently fraudulent, falsified, mistaken or not reproducible” (Furman, Jensen and Murray 2012, p.279) indicates that the original article should not have been published and that its findings and conclusions should not be used as part of the grounds for future research. Retractions are also used to alert readers to cases of redundant publication, plagiarism, and failure to disclose a major competing interest likely to influence interpretations or recommendations (COPE 2008). The main purpose of retractions is to correct the literature and ensure its integrity. A retraction may be initiated by the publishers, journal editors, author(s) of the papers or institutions of whom the authors are affiliated to. There have been numerous examples of retracted scientific publications as highlighted on Retraction Watch (http://retractionwatch.com/), a blog that informs the readers on new retractions, publicizes the reasons and discusses general issues in relation to retractions.

Retractions are a worldwide phenomenon as authors from multiple countries of origin have been found to be involved in unethical publishing practices (Amos 2014).The number and frequency of retracted publications are important indicators of the health of the scientific enterprise, because retracted articles represent “unequivocal evidence of project failure, irrespective of the cause” (Fang et al. 2012, p. 17028). It was reported that the Web of Science (WoS), an authoritative scientific database, recorded 400 retractions in 2011, up from an average of about 30 a year a decade ago, showing that the number of retraction notices has increased ten-fold even as the literature in the WoS has expanded by 44 percent (Van Noorden 2011). About half of the retractions are for author misconduct; higher impact journals have logged more retraction notices over the past decade, but much of the increase from 2006 to 2010 came from lower impact journals. Steen et al. (2013) study also reported that the number of retracted scientific publications in PubMed has risen sharply, but it is unclear whether this reflects an increase in publication of flawed articles or an increase in the rate at which flawed articles are withdrawn.

The prevalence of retractions has been studied frequently for the past few years in specific medical fields (Almeida et al. 2016; Rosenkrantz 2016; Rai and Sabharwal 2017; Bozzo et al. 2017; Nogueira et al. 2017), to name a few, mirroring that in this research area, oversight is greatest because of “a concern for patient safety and the possibility of bodily harm caused by flawed research” (Zuckerman 1977, cited in Hesselmann et al. 2017). Unethical publishing practices cut across nations (Amos 2014) and recent studies have been conducted at the country level, especially in emerging scientifically active countries such as China (Lei and Zhang 2017), and Korea (Huh et al. 2016) where competition for jobs and resources is growing and career success is determined to some extent by research performance. This puts practically all scientists under some “pressures to publish” (van Dalen and Henkens 2012). The publication pressure has clearly become visible and has materialized in a number of practices such emphasis on publications and citations for hiring, promotion, awards and tenure decisions (Anderson et al. 2007; Franzoni et al. 2011; Walker et al. 2010). In emerging economies countries such as China, South Korea and Turkey, researchers are rewarded with cash incentives (Franzoni et al. 2011; Qiu 2010) which Franzoni et al. (2011, p. 703) arguably wrote “incentives increased competition from countries with latent capacity by altering the amount and the apparent quality of the work“that is eventually published. Lei and Zhang (2017) who found that the number of WoS retractions by Chinese researchers increased in the past two decades, concluded that the system of scientific evaluation, the “publish or perish” pressure Chinese researchers are facing, and the relatively low costs of scientific integrity may be responsible for the scientific integrity. This shows that the pressure to publish in academia might conflict with the objectivity and integrity of research, because, as clearly pointed out by Fanelli (2010) that “it forces scientists to produce ‘publishable’ results at all costs”.

In countries currently on the “periphery of the scholarly endeavor” such as Malaysia (Abrizah et al. 2015), productivity and impact are formally built into promotion criteria, and this may have forced scientists to publish continuously and successfully to maintain their careers. The more science policy focuses on research influence, the more researchers and institutions are confronted with evaluations based on publications and citations. The rising frequency of retractions of Malaysian papers on Retraction Watch (http://retractionwatch.com/category/by-country/malaysia/) and its database (http://retractiondatabase.org/RetractionSearch.aspx) has recently elicited concern of the scientific community following wide-ranging postings on social media that questioned the integrity of the researchers. However, there is little hard evidence of the extent of the issue and reasons for retractions have not been investigated for a periphery country. Therefore, we intend to make a start by investigating one country currently on the “periphery of the scholarly endeavor”. This means we shall not only be able to determine how retractions from the periphery characterize, but also to determine the reasons for the retractions. Hence, retractions are worthy of rigorous and systematic study. The empirical part of this study focuses on one non-Western periphery country, Malaysia, which has a developed and well-defined international scientific industry based in its universities. Therefore, the objective of this study is to identify the reasons and the authorities calling for retractions and the Malaysian retracted scholarly publications. In particular, this paper examines four research questions:

-

(a)

How prevalent is retractions of Malaysian papers?

-

(b)

What characterize Malaysian retracted papers?

-

(c)

What are the reasons for retractions of Malaysian papers?

-

(d)

Who is the authority calling for the retractions?

Literature review

A considerable amount of literature has been published on retractions, and there are evidences that the proportion of published studies that are being retracted from the scientific literature is rapidly increasing. Scholarly publications are retracted for a number of reasons and a few studies of retraction notices (Amos 2014; Huh et al. 2016; Moylan and Kowalczuk 2016) and bibliographic information of retractions from citation database (Lei and Zhang 2017; Nogueira et al. 2017) shed lights on the common reasons why the papers are retracted. Steen (2011) who analysed 788 English language research papers retracted from the PubMed database between 2000 and 2010 suggested that error is more common than fraud as a cause of retraction. Fang et al. (2012) who reviewed 2047 biomedical and life-science research articles indexed as retracted by PubMed revealed that only 21.3 percent of retractions were attributable to error. In contrast, 67.4 percent of retractions were attributable to misconduct, including fraud or suspected fraud (43.4%), duplicate publication (14.2%), and plagiarism (9.8%). Using data retrieved from MEDLINE, Wager and Williams (2011) observed that the most common reasons for retraction were honest errors, redundant publication and plagiarism. Using the same database, Damineni et al. (2015) studied the various parameters associated with retraction of 155 scientific articles in 2012 and 2013 and found that the most cited reasons for retraction were again mistakes (honest errors), plagiarism, and duplicate submission. Fabricated data, author disputes and other ethical issues were also identified in a small number of publications. Huh et al. (2016) found that the most common reason for retractions published in Korean medical journals indexed in KoreanMed database is duplicate publication, followed by authorship dispute and scientific errors. Rai and Sabharwal (2017) who studied the prevalence, characteristics and trends of retracted publications in orthopedics found that the most cited reasons for retraction were plagiarism, misconduct (27%), redundant publication, and miscalculation or experimental error. In a recent study of Chinese retracted papers, Lei and Zhang (2017) revealed that misconduct such as plagiarism, fraud, and faked peer review explained approximately three quarters of the retractions. A a large proportion of the retractions seemed typical of thoughtful fraud, which might be evidenced by retractions authored by repeat offenders of data fraud and those due to faked peer review.

Steen (2011) hypothesised that fraudulent authors target journals with a high impact factor, which may be attributed to the prevailing culture in science which disproportionately rewards scientists for publishing large number of papers and getting them published in prestigious journals. Studies of retractions have also found that retractions for fraud are positively associated with the journal’s impact factor (Cokol et al. 2007; Fang and Casadevall 2011; Fang et al. 2012). Fang et al. (2012) offered two possible explanations for this association, that (a) authors are more likely to risk getting caught for breaking ethical rules in order to obtain the career rewards from publication in high-impact journals; and (b) papers published in high-impact journals are more likely to draw scrutiny that leads to the discovery of fraudulent research that requires retraction. Resnik et al. (2015) found that the majority of high-impact journals in the sciences had a retraction policy or adopted ones provided by COPE or other organizations, as the editors and publishers have become aware of the importance of dealing with retractions and almost all of them would retract an article without the authors’ consent. However, Lei and Zhang (2017) found that the majority of Chinese fraudulent authors seemed to aim their articles which contained a possible misconduct at low-impact journals, regardless of the types of misconduct. Nogueira et al. (2017) also found that retractions that were mostly due to the authors’ malpractice were more frequently related to journals with less impact.

When retraction notices were consulted, Grieneisen and Zhang’s (2012) study of 4449 scholarly publications retracted from 1928 to 2011 revealed that over half (56.1%) mentioned either some or all of the authors; and a similar percentage (59.5%) explicitly mentioned either the publisher, “the journal” or editor(s). In contrast, a small percentage mentioned investigations by non-institutional watchdog agencies, such as the US Department of Health and Office of Research Integrity (ORI).

Huh et al. (2016) addressing the retraction of 114 papers in Korea also revealed that the majority of retractions were issued by the authors, followed by jointly issued (author, editor, and publisher), and from editors. A small percentage of retractions were dispatched by institutions.

Materials and method

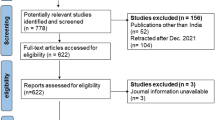

Consistent with Grieneisen and Zhang (2012), we consider a retracted paper to be the one that is explicitly “retracted” or “withdrawn” via a notice, an erratum, corrigendum, editorial note, rectification, or other such as editorial notification vehicle. A search of two citation databases i.e. Clarivate Analytics’ WoS and Elsevier’s Scopus was conducted to identify all papers published by Malaysian-based authors using queries indicated in Table 1. These data sources were chosen as they represent the broad scope scholarly works databases with comprehensive sources that focus on wide range of disciplines. The search was run on 30 July 2017.

The full bibliographic information on retracted publications were stored in an Excel spreadsheet and basic descriptive statistics were generated. Only the article with “(Retraction of)” or “(Retracted”) were selected. Each retracted article citation in the results output was matched up with the citation for its corresponding retraction notice based on either data from the WoS and Scopus records or consultation of the notice to determine which article(s) it retracted. The list of paired retracted article/notice citations was grouped together. All results were manually screened against the retracted article list from two databases. After cleaning the data (i.e. removal of duplicates), a total of 125 articles were used for further analysis.

The reasons for retraction and authority calling for the retractions were manually identified from the retraction notices for the papers, and to the lesser extent the papers themselves, through the journals publisher website. A retraction notice is issued to alert readers when a published study is no longer scientifically valid or trustworthy. Each article was classified according to the cause of retraction, using the published retraction notices. Papers were classified based on the reason for retraction identified in the retraction notices, and each paper was assigned to only one category. An internet search using the Google search engine was also performed to seek additional information regarding retracted articles for which the reason for retraction remained unclear, and included the blog Retraction Watch, news media, and other public records. Each classification decision was independently reviewed by all authors and any discrepancies were resolved.

Results and discussions

Prevalence and characteristics of retractions

The search for retracted papers between 2009 and August 2017 retrieved 125 of 168,950 WoS-indexed and 248,558 Scopus-indexed Malaysian publications (2 per 10,000 articles indexed in WoS; 4 per 10,000 articles indexed in Scopus). Out of the 125 articles, 92 (73.6%) are conference paper and 33 (26.4%) are journal articles. Overall result shows fluctuation number of retracted articles over the years from 2009 to 2017 as shown in Fig. 1. There was a spike in the prevalence of retracted articles in 2010 (42 conference papers) and 2012 (41 papers, comprising 39 conference papers and 2 journal articles). The spike was due to the retractions of conference papers that were found to be in violation of IEEE’s publication principles, retracted “after a careful and considered review of the content of the paper by a duly constituted expert committee” (as stated in the IEEE Xplore, http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/).

We explored how long it takes for a journal to act over the years, and it was found that the time between identifying a problem to retracting the paper varies. Retractions take time and the year gap of publication and retraction was from 0 to 6 years with 101 articles (91 conference proceeding and 10 journal article) were published and retracted in the same year (2009–2012 and 2014–2016) as shown in Table 2. The earliest retraction year is in 2009 for articles in the same publication year (7 articles). Articles published in 2007 were retracted in 2013 (2 articles). A total of 7 articles published in 2014–2016 were retracted in the current year (2017). For the past three recent years (2015, 2016, 2017) the frequency of retractions increased. Due to the time-lag between publication and retraction, only seven retractions were identified in 2017 at the time of the literature search. However, the data do not show any retractions for papers published in the current year (2017). From these observations, we conclude that retraction rates are still on the rise, and the mean time from electronic publication to retraction was 1 year.

The retractions recorded a total of 14 publishers, with the highest percentage of retracted articles were published by IEEE Computer Society (91 articles; 73.4%), followed by Springer (12 articles; 9.6%) and Pergamon-Elsevier Science Ltd (6 articles; 4.8%), Elsevier Science (4 articles, 3.2%), MDPI AG (2 articles, 1.6%) and one each (8%) from 10 other publishers. It is apparent that commercial scientific publishers recorded more retractions (122 articles) as compared to society journals (3 articles).

The retracted articles include 33 journal articles from 26 journals, and 92 conference papers from 21 conference proceedings. To identify if retracted articles are mainly published in journals with a high impact factor, the impact for the 26 journal titles were determined. Because impact indicators such as Journal Impact Factor (JIF) in WoS and SCImago Journal Rank (SJR) are incomparable across different research disciplines, field-normalized journal impact have been used. Journal Quartile is the commonly used one, and it is intended to reflect the place of a journal within its field, the relative difficulty of being published in that journal, and the prestige associated with it. Journals are categorized into four different quartiles, namely Q1, Q2, Q3 and Q4, which indicate their quality or tier in ranking. The Journal Quartile for each journal from both WoS and Scopus were identified, however a higher quartile was taken and used for analysis. A total of 14 (43.4%) retractions papers were identified in Q1 journals, 10 (30.3%) retractions in Q2 journals, 6 (18.2%) in Q3 and 3 (9.1%) in Q4. Figure 2 presents the distribution of the retractions based on the journal quartile, which may indicate that retractions are associated with the journal’s impact factor.

Fisher’s exact test was used to study the relationship between journal quartile and mean number of month to retraction due to small sample sizes. The result indicates that there is no significant relationship between journal quartile and mean number of months to retraction (P = 0.842). Table 3 presents the contingency table comparing the relationship between the frequency and percentage for the joint distribution of journal quartile and mean number of month to retraction.

One element of the characteristic of retraction addressed was subject discipline of the papers. The retracted papers were coming from sciences subject field with the highest percentage is 40 percent (50 articles). This is followed by Engineering and Technology (38.4%; 48 articles). Table 4 shows the broad subject category of the retracted articles. The 33 subject categories identified from WoS and Scopus were re-categorized into five broad subjects based on Malaysian Citation Centre (MCC) (http://www.myjurnal.my/public/about.php) classification.

In terms of authorship, only 8.9 percent (11 articles) from the 125 retractions are from single authored papers. The remaining 91.1 percent (113 articles) are collaborative works with co-authors from national (73 articles) and international (40 articles) affiliations. Table 5 shows 18 international collaborative countries of the retracted articles with the highest percentage are Iran (19.0%, 8 articles), followed by Pakistan, Saudi Arabia with 5 articles for each country and Australia (9.5%, 4 articles). With much research is engaged internationally collaborative, problems can arise when scientific fraud or mistake is committed within a cross-border partnership. Our finding on the collaborative and multi-authored characteristic of Malaysian retracted papers raised the following sub-research questions: Do Malaysian authors play a major contribution in retracted papers? When analyzed based on authorship, Malaysian authors show the highest percentage as reprint author for the retracted articles (90.4%, 113 articles), followed by Australia and India, with 2 articles each (Table 6). The reprint (or corresponding author) in practice, takes the ownership for compliance, pre and post-publication with all journal policies and would be the final decision maker on behalf of all authors for any actions that need to be taken. In the context of Malaysian scholarly publishing, reprint author is now used to indicate seniority and leadership of the research work, and it has been used as an indicator in research assessment (Noorhidawati et al. 2017). As Malaysian (or Malaysian based) authors were reprint authors to at least 90 percent of the retracted papers, it is safe to conclude that Malaysian authors, to a large extent, are major contributors to the retractions.

While compiling the list of authors, we noticed that a substantial numbers of retracted articles were associated with a single corresponding author. Since the dataset is small, corresponding author names yielding more than two times were then extracted to determine how many articles were attributable to a single individual based on institutional affiliation. Of the 4 corresponding authors who are considered as “repeat offenders” (Steen 2011), one had 6 retractions, and another three had 4, 3 and 2 respectively. They are collectively responsible for 12 percent of the retractions.

Reasons for retractions and authority calling for retractions

Justifications for retractions stated in the notices consulted are outlined in Table 7. The reason for retraction was stated in all cases. The highest percentage of reason for retraction is “violation of publication principle” (73.6%; 92 articles)—the statement provided in the retraction notice. In these 92 cases, the specific reason for retraction was not stated and thus it could not be confirmed in these cases as to whether the error was accidental (mistake) or intended (misconduct). Looking further at the data, these retracted articles came from 21 conference proceedings, with the conferences hosted by IEEE Computer Society having the most retractions (50 articles). From the 33 retractions that clearly defined the reasons, 12 (9.6%) were attributed to duplicate publication, of which 9 of them came from “repeat offenders”. Plagiarism accounted for 6 (4.8%) retracted articles, followed by compromised peer review process and self-plagiarism, with 4 retracted articles respectively (3.2%)—all associated with misconduct. Retraction was classified as being due to misconduct (or presumed misconduct) only if the statement of retraction clearly admits to wrongdoing on the part of one or more of the authors (Budd et al. 1998). Another 4 retractions were also due to misconduct—data used without permission; duplicate publication and author dispute; and copyright issue. Scientific mistakes accounted for only 2 retractions.

To better understand the roles of various authorities in the retraction of articles, for each case where the retraction notice was obtained the authorities specifically mentioned in the notice were recorded. Table 8 shows six retraction authorities stated in the notices consulted. The highest authority are publisher with 79.0 percent (98 articles) followed by editor(s) with 16.0 percent (16 articles), and both editors and publisher (4 articles, 3.2%). Only 1 article was retracted by author(s). Although a single paper may be retracted for multiple reasons (Steen et al. 2013), all 125 papers were retracted for a single infraction.

Comparison was made between retraction reason and authority as shown in Table 9. Publisher retracted a total of 92 articles due to publication violation. In addition, 2 articles were retracted for duplication by publisher, editor(s) and publishers. In general, the finding shows publisher and editor are the main authorities to retract articles for various misconducts such as duplication, self-plagiarism, plagiarism and fraudulent reviewer. On the other hand, author(s) retracted their articles because of duplicate publication. Therefore, in the present study, it was found that retractions were most often issued by the publisher and editor(s). This result was very different from the findings by Budd et al. (1998) and Wager and Williams (2011) where articles were mainly retracted by authors. Editors, publishers or funding agencies can decide to retract a paper, but the usual policy is that the authors themselves must retract (Editorial 2003). Only in extreme circumstances would an editor retract a paper without the agreement of the authors, although it is very rare that authors will voluntarily retract as reflected from this study. Authors are reluctant to voluntarily withdraw their material, even if the error is merely due to an honest mistake (van Noorden 2011).

Conclusion

Both retraction numbers and rates are important for assessing the extent of publication practices in countries. Exploring reasons for retractions across countries contributes to understanding of publication ethics and integrity, however investigating country-based rates of retraction and the reasons, however, offered a different perspective. We conclude that although retractions may represent a small fraction of a percent of all Malaysian publications indexed in the WoS and Scopus, they occurred mainly due to misconduct, and this is a matter of major concern in the scientific world. Given that most scientific work is publicly funded and that “retractions because of misconduct undermine science and its impact on society” (Fang et al. 2012), the surge of retractions suggests a need to reevaluate the incentives driving this phenomenon, most probably due to the following reasons: (a) the increase in the Malaysian scientific publications for the past 10 years; (b) common incidences of infractions; (c) infractions are now detected more quickly; and (d) lack of awareness of publishing ethics and integrity or tolerance of the problem. The misconduct in retractions was mainly attributed to duplication and plagiarism, and both lower-income countries and non-English speaking countries have a higher risk of retractions than other countries because of these issues (Stretton et al. 2012). Therefore, the general hypothesis that national contexts might influence the incidence of scientific misconduct (Hesselmann et al. 2017) seems plausible.

The work reported here has several limitations. While the search methodology aimed to be inclusive as possible, we acknowledge that it may not have captured all Malaysian retracted articles. Another limitation of our study is that it covers only retractions in WoS and Scopus, which have specific filters for retracted articles, where other journal databases do not have. Therefore, the extent of retractions for Malaysian publications, particularly Malaysian-based journals that are not indexed in these databases are not known. It should also be noted that this study focuses on work that has been acknowledged to be based on mistake or misconduct. The question remains as to how much erroneous or fraudulent work goes undetected or unacknowledged. That is a larger question that should be addressed by the scientific community; the evidence provided by this study suggests that it is a thoughtful question with profound implications for research. Therefore, continuing this research with a larger sample; considering differences among journals in the amount of literature published; and investigating the numbers of authors involved, and not only journals, would shed further light on the scope of the problem.

References

Abrizah, A., Badawi, F., Zoohorian-Fooladi, N., Nicholas, D., Jamali, H., & Norliya, A. K. (2015). Trust and authority in the periphery of world scholarly communication: A Malaysian focus group study. Malaysian Journal of Library & Information Science, 20(2), 67–83.

Almeida, R. M. V. R., Catelani, F., Fontes-Pereira, A. J., & Gave, N. S. (2016). Retractions in general and internal medicine in a high-profile scientific indexing database. Sao Paola Medical Journal, 134(1), 74–78. https://doi.org/10.1590/1516-3180.2014.00381601.

Amos, K. A. (2014). The ethics of scholarly publishing: exploring differences in plagiarism and duplicate publication across nations. Journal of Medical Library Association, 102(2), 87–91.

Anderson, M. S., Ronning, E. A., De Vries, R., & Martinson, B. C. (2007). The perverse effects of competition on scientists’ work and relationships. Science and Engineering Ethics, 13(4), 437–461.

Bozzo, A., Bali, K., Evaniew, N., & Ghert, M. (2017). Retractions in cancer research: A systematic survey. Research Integrity and Peer Review. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41073-017-0031-1.

Budd, J. M., Sievert, M., Schultz, T. R., & Scoville, C. (1998). Effects of article retraction on citation and practice in medicine. Bulletin of the Medical Library Association, 87(4), 437–443.

Cokol, M., Iossifov, I., Rodriguez-Esteban, R., & Rzhesky, A. (2007). How many scientific papers should be retracted? EMBO Reports, 8(5), 422–423.

COPE. (2008). Code of Conduct. Committee on Publication Ethics. Available at: https://publicationethics.org/files/2008%20Code%20of%20Conduct.pdf.

Damineni, R. S., Sardiwal, K. K., Waghle, S. R., & Dakshyani, M. B. (2015). A comprehensive comparative analysis of articles retracted in 2012 and 2013 from the scholarly literature. Journal of International Society of Preventive & Community Dentistry. https://doi.org/10.4103/2231-0762.151968.

Editorial, (2003). The long road to retraction. Nature Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm0903-1093.

Fanelli, D. (2010). Do pressures to publish increase scientists’ bias? An empirical support from US states data. PLoS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0010271.

Fang, F. C., & Casadevall, A. (2011). Retracted science and the retraction index. Infection and Immunity, 79(10), 3855–3859.

Fang, F. C., Steen, R. G., & Casadevall, A. (2012). Misconduct accounts for the majority of retracted scientific publications. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1212247109.

Franzoni, C., Scellato, G., & Stephan, P. (2011). Changing incentives to publish. Science, 333(6043), 702–703.

Furman, J. L., Jensen, K., & Murray, F. (2012). Governing knowledge in the scientific community: Exploring the role of retractions in biomedicine. Research Policy, 41(2), 276–290.

Grieneisen, M. L., & Zhang, M. (2012). A comprehensive survey of retracted articles from the scholarly literature. PLoS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0044118.

Hesselmann, F., Graf, V., Schmidt, M., & Reinhart, M. (2017). The visibility of scientific misconduct: A review of the literature on retracted journal articles. Current sociology, 65(6), 814–845.

Huh, S., Kim, S. Y., & Cho, H. M. (2016). Characteristics of retractions from Korean medical journals in the KoreaMed database: A bibliometric analysis. PLoS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0163588.

Lei, L., & Zhang, Y. (2017). Lack of improvement in scientific integrity: An analysis of WoS retractions by Chinese researchers (1997–2016). Science and Engineering Ethics. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-017-9962-7.

Moylan, E. C., & Kowalczuk, M. K. (2016). Why articles are retracted: A retrospective cross-sectional study of retraction notices at BioMed Central. British Medical Journal Open. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-012047.

Nogueira, T. E., Gonçalves, A. S., Leles, C. R., Batista, A. C., & Costa, L. R. (2017). A survey of retracted articles in dentistry. BMC Research Notes. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-017-2576-y.

Noorhidawati, A., Aspura, M. K. Y. I., & Abrizah, A. (2017). Characteristics of Malaysian highly cited papers. Malaysian Journal of Library & Information Science, 22(2), 85–99.

Qiu, J. (2010). Publish or perish in China. Nature. https://doi.org/10.1038/463142a.

Rai, R., & Sabharwal, S. (2017). Retracted publications in orthopaedics. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.16.01116.

Resnik, D. B., Wager, E., & Kissling, G. E. (2015). Retraction policies of top scientific journals ranked by impact factor. J Med Libr Assoc. https://doi.org/10.3163/1536-5050.103.3.006.

Retraction (2017). Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Retraction.

Rosenkrantz, A. B. (2016). Retracted publications within radiology journals. American Journal of Roentgenology, 206(2), 231–235. https://doi.org/10.2214/AJR.15.15163.

Steen, R. G. (2011). Retractions in the scientific literature: do authors deliberately commit research fraud? Journal of Medical Ethics, 37(2), 113–117.

Steen, R. G., Casadevall, A., & Fang, F. C. (2013). Why has the number of scientific retractions increased? PLoS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0068397.

Stretton, S., Bramich, N. J., Keys, J. R., Monk, J. A., Ely, J. A., Haley, C., et al. (2012). Publication misconduct and plagiarism retractions: A systematic, retrospective study. Current Medical Research and Opinion, 28(10), 1575–1583.

van Dalen, H. P., & Henkens, K. (2012). Intended and Unintended consequences of a publish-or-perish culture: A worldwide survey. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 63(7), 1282–1293.

van Noorden, R. (2011). Science publishing: The trouble with retractions. Nature. https://doi.org/10.1038/478026a.

Wager, E., & Williams, P. (2011). Why and how do journals retract articles? An analysis of medline retractions 1988–2008. Journal of Medical Ethics, 37, 567–570.

Walker, R. L., Sykes, L., Hemmelgarn, B. R., & Quan, H. (2010). Authors’ opinion on publication in relation to annual performance assessment. BMC Medication Education, 10, 21.

Zuckerman, H. (1977). Deviant behaviour and social control in science. In E. Sagarin (Ed.), Deviance and Social Change (pp. 87–138). SAGE: Beverly Hills.

Acknowledgements

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for profit sectors. The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Aspura, M.K.Y.I., Noorhidawati, A. & Abrizah, A. An analysis of Malaysian retracted papers: Misconduct or mistakes?. Scientometrics 115, 1315–1328 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-018-2720-z

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-018-2720-z