Abstract

This study sought to explore the existing academic literature on female entrepreneurship to assess how this field of research is organized in terms of publications, authors, and periodicals and/or sources. In addition, the research focused on mapping knowledge networks through citation and co-citation analysis and identifying natural clusters of the main keywords used. The study also examined the challenges (i.e., opportunities and difficulties) the literature reveals for the study of female entrepreneurship. That is, the knowledge gained from the bibliometric study (i.e., what has already been researched and the limits of these studies) was used to identify what research opportunities are present in this area. The articles gathered in the search were submitted to a bibliometric analysis using VOSviewer and TreeCloud software. The results obtained from the analysis of document citations reveal three clusters: (1) entrepreneurial profile, (2) gender identity and theoretical conceptualizations, and (3) the entrepreneurial process context. By studying the articles’ citation profile, this study’s findings contribute to a better understanding of the flow of production and research-related practices in this stimulating area of research, which is still in its infancy phase.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Entrepreneurship can involve multiple realities, but all of these have the defining characteristic of actions that create something different and valuable. Entrepreneurs dedicate the necessary time and effort, assume the financial, psychological, and social risks inherent in these actions, and, simultaneously, receive the resultant rewards of economic and personal satisfaction. However, entrepreneurship development depends on a set of structuring factors, including, among others, the availability of finance, state-sponsored support policies and programs, the quality and content of education and training, the transfer of the results of R&D from the scientific to the business community, access to commercial and physical infrastructures, the internalization of innovation attitudes and creative practices in the key professions, the openness of target markets, and the influence of social of social and cultural norms, among others.

Due to the limited research published so far on the specificities of women entrepreneurs’ interactions with the scientific community, the present study focused primarily on female entrepreneurship in general. Indeed, while already represented by a considerable number of articles in journals, book chapters and conference papers, research in female entrepreneurship can be considered to be still in its infancy (Henry et al. 2015). To date, most research in this field has viewed gender as a variable affecting individual intentions and performance, rather than as a multifaceted context, and has mainly focused on the downstream links in the value chain connecting science to the market and, in particular, on the business start-up process. Even in studies of the “multiple helix” of research, education, business, state and community organizations that make up the regional innovation system, little specific emphasis has been placed on gender aspects of the mediated interface between those producing science and those applying it. Moreover, despite the existence of regional, national and international policy instruments designed to ensure that new technologies and innovation processes empower women rather than exacerbating gender inequalities, gender obstacles continue to impact negatively on women in the “formal” business community. Recently, however, the findings of pioneering studies of the meso-and macro-level impacts of gender inequality have started to become available (see e.g. Galindo and Ribeiro 2011; Díaz-García et al. 2016; Bijedic et al. 2016; Birkner et al. in press).

When entrepreneurship is analyzed from a gender perspective, female entrepreneurship is characterized by different experiences which in turn shape women’s entrepreneurial attitudes, since stereotypes of gender traits and inter-gender relations continue to persist, along with concrete practices of discrimination (e.g., Henry et al. 2015; Santos et al. 2016). Explicitly or more subtly, these practices are manifested in both the job market and in society—more in practice than in speech. This discrimination can often translate, for example, into unequal gender access to institutional and financial resources, important market players, and key professional organizations, creating myriad barriers that are difficult to circumvent.

The first publication on female entrepreneurship appeared in a management journal accredited by the Social Science Citation Index [SSCI] in 1976 (i.e. Schwartz’s “Entrepreneurship—New Female Frontier” in the Journal of Contemporary Business). However, articles on female entrepreneurship only began to appear in greater numbers in the 1980s. 10 years passed before another study was published in the Academy of Management Review, this time by Bowen and Hisrich (1986): “The Female Entrepreneur—A Career-Development Perspective.” Today, the findings of studies carried out in this field are reported on by a multitude of researchers from around the world and from different disciplinary fields, albeit mostly linked to the social sciences and mainly focused on women who embrace self-employment by creating their own businesses.

A number of previous analyses of the literature have concentrated on female entrepreneurship (e.g., Bowen and Hisrich 1986; Brush 1992; Carter et al. 2001; de Bruin et al. 2006; Brush et al. 2009; Minniti 2009; Terjesen et al. 2011; Sullivan and Meek 2012; Ahl and Marlow 2012; Jennings and Brush 2013; Henry et al. 2015, Poggesi et al. 2015; Edelman et al. 2017) and have provided a more systematic understanding of what had already been studied, as have various more narrative reviews of the literature (Birley 1989; Moore 1990; Brush 1998; Gundry et al. 2002; Ahl 2006; Carter and Marlow 2006).

Most review articles have focused on the key topics, perspectives, methodologies, and/or results of female entrepreneurship research, starting with Bowen and Hisrich’s (1986) study. Some reviews categorize the existing research by units of analysis, summarizing works at a micro, meso, and macro level (e.g., Brush 1992; Brush et al. 2009). Others classify the existing research according to the stage of the entrepreneurial process, e.g. the pre-creation, creation, and post-creation phases of firm development (e.g., Sullivan and Meek 2012). Still another subset of reviews has classified research according to their degree of originality and thematic relevance (e.g., de Bruin et al. 2007; Hughes et al. 2012; Link and Strong 2016). A final group of articles can be characterized as constructively criticizing the existing academic literature, with the main objective of encouraging researchers to apply new approaches and seek out innovative directions in this field.

Among the studies of this type of literature, Ahl’s (2006) article stands out as an important contribution. It combines feminist theory with discourse analysis to demonstrate how the prevailing research practices give precedence to certain issues and approaches rather than others. Another significant article was written by Ahl and Marlow (2012), who identified the central independent variable in this field as masculine and feminine genders, arguing that the focus of research on female entrepreneurship needs to shift from women entrepreneurs alone to the field of entrepreneurship in general—albeit from a feminist perspective.

As the above discussion shows, no systematic reviews of literature have thus far used bibliometric techniques, so the research reported on here sought to fill this gap in the research in the area of female entrepreneurship. Notably, most of the studies have limited their research to a single area—usually management. However, Poggesi et al.’s (2015) study also covers the area of sociology. Reflecting this latter trend, the present research also broadened its scope and included, in addition to business and management, other disciplinary areas related to women’s studies, such as sociology and anthropology.

Thus the rationale for the present study lies in its recognition that research on female entrepreneurship has expanded exponentially in recent years and that it is time to assess its progress and reflect on possible future directions for research, in order to gain a more detailed and profound understanding of this phenomenon and process (Poggesi et al. 2015). More specifically, a question that needs to be answered by any literature review on this subject is: have the studies carried out on women entrepreneurs over the last four decades had any impact on the general theory of entrepreneurship and on research in this larger field?

Given the importance of this topic, both in practical and theoretical terms, the present study sought to explore and describe the existing academic literature on female entrepreneurship, with the following specific objectives:

-

1.

To describe how this field of research is organized in terms of publications, authors, and journals and/or sources;

-

2.

To identify the main terms (i.e., keywords) used and to what extent they are grouped (i.e. keyword clusters);

-

3.

To discuss to what extent the literature challenges (i.e. exposes opportunities and difficulties in) hitherto conventional approaches to female entrepreneurship and, based on the knowledge produced by this bibliometric study (i.e. on what has already been studied and the limitations of such research), the future research opportunities that may exist in this area.

A systematic approach was adopted in the literature review, following a rigorous protocol and definition of steps to perform the search for and analysis of the literature in this field, based on research-based articles indexed in the Web of Science. The articles identified as focusing on female entrepreneurship were subjected to bibliometric and lexical analyses, producing a classification of articles reflecting the various objectives of this study. Both the bibliometric and lexical analyses contributed significantly to exploring and describing the existing academic literature on female entrepreneurship.

This paper is structured as follows. The above introduction, in which the work to be developed is presented, is followed by a retrospective evaluation of the past 40 years of research on female entrepreneurship, summarizing the work carried out from the 1980s to 2016, addressing each of the themes under scrutiny. The third section describes the methods and tools used. The fourth section discusses the mapping of knowledge networks and presents the results of the research. The final section offers the main conclusions reached, as well as suggestions for future research.

Female entrepreneurship over the last 40 years

The first studies in the area of female entrepreneurship emerged in the United States in the mid-1970s, focusing on the differences between men and women entrepreneurs with regard to their psychological and sociological characteristics (Schwartz 1976). This research area was a departure from previous purely exploratory and descriptive studies, moving toward more specialized studies (Carter and Shaw 2006). Since then, this topic has become one of the main focuses of academics, politicians, and other stakeholders connected to entrepreneurship (Henry 2007).

Initially, all entrepreneurs encounter challenges such as obtaining funding and concerns over business growth, but researchers have concluded that the obstacles faced by entrepreneurial women are, as a rule, larger than those encountered by men (Brush and Gatewood 2008). This is in part because entrepreneurship has, since the beginning, largely been connoted with the male domain. According to Brush and Gatewood (2008), the first entrepreneurship studies were based only on samples of male entrepreneurs, concentrating on characteristics and behaviors related to entrepreneurship that were typically considered masculine, such as rationality, risk propensity, the desire for autonomy, the capacity to identify business opportunities (McClelland 1961; Collins and Moore 1964).

In sociological terms, women are raised to pursue careers as employees in the caring professions—ranging from teaching, nursing, child-care, to a wide variety of personal retail services, rather than being encouraged to start their own businesses (Brush 1992; Mueller and Dato-On 2008). Brush and Gatewood (2008) point out that gender perceptions have their roots in the messages emanating from society in general and from the organizational ecology surrounding entrepreneurial decisions, both of which influence the way men and women develop their careers. Women’s professional ambitions and the roles they are expected to fulfill are influenced by parents, peers, schools, media, and various other dimensions of the external environment, among other stimuli. Often these factors give rise to stereotypes about the types of roles that men and women are able to and/or should assume and how, in general, they should act in society. As noted in Eagly and Steffen (1984) and Gupta et al.’s (2014) studies, gender discrimination persists, with women still being stereotyped in general and new stereotypes being ascribed to business-women in particular; the result is that, if contemporary female entrepreneurs are to survive and prosper, they must overcome not only the pre-existing social constraints on women’s achievements, but also the newly-erected barriers against their acceptance into the business community as equals.

Mueller and Dato-On (2008) cite the argument advanced 30 years earlier by Chodorow (1978) that women’s relational and empathy skills are instilled and their identities forged within family relationships. In contrast, men are encouraged to develop independence and organizational capacities (Chodorow 1978, cited in Mueller and Dato-On 2008). More recent empirical research on socialization still generally supports the proposition that women are more cooperative, have more empathy and tend to emphasize interpersonal relationships more than men (Kelly 1991), though the source of these behaviors is now recognized as being complex and plural rather than simply family-based (Jennings and McDougald 2007). Nevertheless, these traits can differentiate women’s business performance—to their detriment and/or benefit—from that of men.

The potential conflict between work and family was an important factor identified by Kahn et al. as early as 1964. Consistent with role theory, researchers have assumed that entrepreneurs have personal and professional roles both of which are critical to their business performance (Kahn et al. 1964). When the demands of one role intersect and interfere with those of another, conflicts between work and family arise (Greenhaus and Beutell 1985). This theme has been extensively developed over the last 40 years, and now has a vast literature (see e.g., Ford et al. 2007; Shelton et al. 2008; Eddleston and Powell 2012; Mari et al. 2016).

What appears clear from this literature is that the responsibility for establishing and maintaining a balance between the demands of family and business is typically seen as the role of women (Marlow 1997), both from a material perspective (i.e., how much time is dedicated to each set of activities) and a psychological standpoint (e.g., the feelings, desires, and fears that each set of activities evokes). Some studies have suggested that, for mothers, entrepreneurship provides greater flexibility than wage-employment for professional and domestic responsibilities to be combined (Caputo and Dolinsky 1998). Women thus seek to organize their time in order to avoid a conflict between their roles as entrepreneurs and mothers and/or wives.

Meeting the obligations of one domain reduces the time and energy available for another, tending to create conflict when individuals try to effectively fulfil all their roles in multiple domains (Ruderman et al. 2002). Some factors that contribute to the professional and family demands examined by Byron (2005) include the hours spent at work and outside work, the flexibility of working hours, professional and family stress, professional and family support, and professional and family involvement. Additional factors are the number and age of children, intra-family availability of childcare, spouses’ professional and marital statuses, as well as demographic variables such as age, gender, and income. Notably, Powell and Eddleston (2013) report that family is no longer considered only women’s responsibility and that family is considered primarily an important asset.

Numerous studies have examined the motivations of entrepreneurial women (e.g., Hisrich and Brush 1984; Stokes et al. 1995; Kelley et al. 2011; Coleman and Robb 2012; Poggesi et al. 2015). These researchers have concluded that women, unlike men, predominately respond to push factors such as the existence of frustration and distress in their previous jobs, lower pay compared to men, and longer career breaks. In addition, women from a certain level onward do not progress to top positions, i.e. are held back by the “glass ceiling.” Larwood and Gattiker (1989) suggest that women’s professional careers cannot be fully understood if they are analyzed in the light of men’s standards, pointing out that men usually give priority to their career, while women have to distribute their investment of time and energy between their family and professional life.

Methodology

A general search of the literature on female entrepreneurship using any academic search engine or referential database reveals an extensive but fragmented field and the presence of studies in various disciplines and research areas (e.g., sociology, women’s studies, anthropology, economics, and management). Therefore, in order to avoid frequent deviations from the main topic when a large amount of literature needs to be analyzed, a systematic review can be used to focus on developing an exhaustive summary of the most relevant and internationally recognized literature (Tranfield et al. 2003). This methodology has been widely used in the social sciences in different areas of research (e.g., Crossan and Apaydin 2010; Teixeira 2011; Keupp et al. 2012; Jennings and Brush 2013; Meyer et al. 2014; Henry et al. 2015; Liñán and Fayolle 2015; Poggesi et al. 2015). Many systematic reviews have been based on an explicitly quantitative meta-analysis of the available data, but a smaller number have used more qualitative analyses (i.e. content analysis) (Thomas et al. 2004).

Figure 1 shows how this process can comprise as many as five steps. Steps 1 and 3 are largely objective in nature, and Steps 1, 4, and 5 are predominantly subjective. In the present study, the methodology included Steps 1, 2, and 3.

In order to identify articles on female entrepreneurship, a search was carried out (see Table 1) in the main collection of the Web of Science indexed database. This database contains information from the beginning of the twentieth century, with weekly updates, and the database is one of the most important in terms of academic journals. This source has one of the largest bibliometric database for the past 40 years, containing a set of indexes associated with it (e.g., SSCI, Science Citation Index Expanded [SCI-Expanded], and, more recently, the Emerging Sources Citation Index [ESCI]). A search was carried out for articles published between 1900 and 2016 with the terms “wom?n entrepreneur* (i.e. containing the words woman entrepreneur or women entrepreneurs),” “female entrepreneur*,” or “gender entrepreneur*,” in the title. The preliminary search results showed that the first publication appeared in 1976 and included 771 documents.

The search was further refined in order to consider only articles, leaving out books, book chapters, working papers, and comments, among other documents, which resulted in 411 documents. Since this literature review sought to provide a comprehensive view of research undertaken across various distinct disciplines, the search was carried out in the SSCI, the SCI-Expanded, and ESCI indexes of Web of Science. The focus was not only on the area of management but also on other areas, such as women’s studies, psychology, ethnic studies, and social work, in order to systematize the literature review and broaden the scope of knowledge about the field of female entrepreneurship. After excluding areas outside those mentioned previously, the search was reduced to the areas listed in Table 1 above, resulting in a final sample of 347 articles. Thus, all the analyses carried out in this systematic review, such as co-citation or lexical analyses, were carried out on this database of 347 documents.

Co-citation analysis, according to McCain (1990), uses co-citation counts to construct measures of similarity between documents, authors, or journals and/or sources. Co-citation is defined as the frequency with which two units are cited together (Small 1973), and different types of co-citation can be used depending on the unit of analysis: document co-citation analysis, author co-citation analysis (White and Griffith 1981; McCain 1990; White and McCain 1998), and journal and/or source co-citation analysis (McCain 1991). In the present study, the co-citation analysis included all three aspects, with different inclusion criteria considered according to the number of citations. All bibliometric analysis was carried out using the software VOSviewer (van Eck and Waltman 2010).

This systematic review thus had three differentiating aspects. First, it adopted a thematic approach to the analysis of the 347 selected papers, thus contributing to filling a gap in the literature on female entrepreneurship. Second, this review applied insights from a management perspective and other areas related to women’s studies (e.g., cultural, social, geographical, and anthropological research), thus responding to recent calls for more interdisciplinary approaches. Last, it adopted a more inclusive research criterion i.e. not limiting itself to a specific group of journals, thereby facilitating the construction of a more comprehensive picture of research on the phenomenon of female entrepreneurship.

Characterization of articles under study

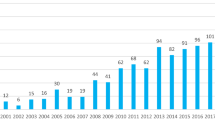

As can be seen from the results presented in Fig. 2, female entrepreneurship research has achieved significant importance. The graph confirms that the increase in items published per year has not been consistent, with an especially accentuated increase in 2007. Between 2008 and 2010, there was a decrease, returning again to consistent growth from 2011 to 2016. The year with the highest concentration of publications was 2015, with 62 publications in the study sample. These results reveal that more widespread interest on the issue in question is relatively recent and that, over the last 10 years, female entrepreneurship has become a topic of research and discussion among more researchers in the field. Notably, 56 articles (16.1%) were published in the 28 years from 1976 to 2004, 168 articles (48.4%) in the 10 years from 2005 to 2014, and 123 articles (35.5%) in just 2 years from 2015 to 2016. This shows that publication on the subject has substantially increased, particularly in the most recent past.

Table 2 presents the top eight most-cited articles of the final sample, with over 100 citations. This was the first part of step three of the bibliometric review process. The most cited article, with a total of 182 citations, was written by Wilson, Kickul, and Marlino, in 2007, and published in the journal Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice. In order to contextualize better the most cited articles, a brief characterization of these eight publications is provided below.

Gender, Entrepreneurial Self-Efficacy, and Entrepreneurial Career Intentions: Implications for Entrepreneurship Education

Wilson et al. (2007) examined the relationships between gender, entrepreneurial self-efficacy, and entrepreneurial intentions for two samples: one of adolescents and one of masters of business administration (MBA) students. Similar gender effects were found with regard to entrepreneurial self-efficacy for both groups. In addition, the impacts of entrepreneurship education in MBA programs on entrepreneurial self-efficacy are stronger for women than for men.

Family Matters: Gender, Networks, and Entrepreneurial Outcomes

In this article, Renzulli et al. (2000) examined several factors that may have an effect on business creation, with a focus on possible gender differences. The association between male and female social capital (conceptualized as inherent in the relationships between individuals) and the probability of starting a business was examined. The authors highlight two aspects of respondents’ social capital: the extent of heterogeneity in their business discussion networks and the proportion of family members in those networks. This study found that, regardless of gender, a high proportion of family members and homogeneity in networks are critical disadvantages for potential entrepreneurs.

A Theoretical Overview and Extension of Research on Sex, Gender, and Entrepreneurship

This research analyzed Finland’s performance in high-growth entrepreneurship and used Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) data to compare Finland with other European countries. Finland’s prevalence rate in high-growth entrepreneurship is well below that of most of its European counterparts and all its Scandinavian counterparts. Fischer et al. (1993) describe this result as a paradox since, while Finland shows poor performance in high-growth entrepreneurship, it is simultaneously a world leader in per capita investment in R&D. The reasons underlying Finland’s poor performance are unclear. The cited authors suggest that explanations can be sought in cultural contexts, industrial traditions, and systemic experiences in high-growth entrepreneurship.

The Entrepreneurial Propensity of Women

This article states that entrepreneurship is becoming an increasingly important source of employment for women in many countries. The level of female involvement in entrepreneurship, however, is still significantly lower than that of men. Langowitz and Minniti (2007) used a behavioral economics approach and a large sample of individuals from 17 countries to investigate which variables influence women’s entrepreneurial propensity and whether these variables have a significant correlation with gender differences. In addition to demographic and economic variables, the study included a number of perceived variables. The results reveal that subjective perceptual variables have a crucial influence on women’s entrepreneurial propensity and contribute heavily to the difference between men and women. More specifically, in all 17 countries, women tend to perceive themselves, as well as their entrepreneurial environments, in a less favorable way than men do in all 17 countries. The results also suggest that variables of perception can be universal factors that significantly influence entrepreneurial behavior.

Doing Gender, Doing Entrepreneurship: An Ethnographic Account of Intertwined Practices

The traditional literature and research on entrepreneurship are based on a supposedly universal model of economic rationality that fails to take gender in account. Bruni et al. (2004) describe the processes that place individuals as “men” and “women” in entrepreneurial practices and as “entrepreneurs” in gender practices, based on an ethnographic study conducted in small companies in Italy. Five processes of the symbolic construction of gender and entrepreneurship are highlighted, among which is managing work-family roles.

Women’s Organizational Exodus to Entrepreneurship: Self-Reported Motivations and Correlates with Success

Buttner and Moore (1997) examined the reasons why 129 executive women left large organizations to become entrepreneurs and how they measure their own success. The results show that these women’s main motivations are the desire for challenge and self-determination and the need to find a balance between family and professional responsibilities. Obstacles to career advancement in large organizations are also important, including discrimination and organizational dynamics. These entrepreneurs measure success in terms of self-realization and achievement of goals. Profits and business growth, although important, are given less weight than personal success.

All Credit to Men? Entrepreneurship, Finance, and Gender

The availability and access to finance is a critical element for start-ups and, consequently, for the performance of any new company. Thus, barriers or impediments to access at appropriate levels or to sources of funding have a lasting negative impact on the performance of the companies involved. Although the results were somewhat inconsistent, Marlow and Patton (2005) found support for the notion that women who become self-employed entrepreneurs are disadvantaged by their gender. This argument was further tested with theoretical gender analysis, using the example of access to formal and informal funding sources to illustrate how this issue affects self-employed women.

Female and Male Entrepreneurs—Psychological Characteristics and Their Role in Gender-Related Discrimination

Previous studies had shown that both genders possess the necessary characteristics for effective performance as managers. However, Sexton and Bowman-Upton (1990) showed that negative attitudes persist toward women administrators. Trace analysis studies found more similarities than differences between the two gender groups. However, a gap still exists between perceptions of male and female entrepreneurs and their real traits, and this difference is even more significant when considering the impact of characteristics on occupational choices. The study showed that the psychological propensities of female and male entrepreneurs are more similar than different. It is unlikely that the few differences observed affect individuals’ ability to run a growing business.

Characterization of journals and/or sources under study

Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice is the most cited journal with 894 citations, corresponding to 14 articles published, followed by the Journal of Business Venturing with 818 citations for 13 papers. Notably, Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice is one of the most sought-after journals for researchers in the area of entrepreneurship, showing an impact factor in 2015 of 3.414. Table 3 presents the journals and/or sources with the highest number of citations, as well as the corresponding number of articles and the journals’ impact factor in 2015.

The Academy of Management Annals (2015 impact factor = 9.741) is the number one publication in the SSCI ranking for the management category. This journal is ranked among the 10 most frequently-cited, with a high impact factor. Among other articles, this journal published “Research on Women Entrepreneurs: Challenges to (and from) the Broader Entrepreneurship Literature?” in 2013, whose authors are Jennings and Brush, from Canada and the United States, respectively.

Regarding the research area of the articles under study, 74.9% are associated with business economics. The present bibliometric study sought to be as inclusive as possible to provide a broad and heterogeneous overview of the subject under study, which is why other areas that include female entrepreneurship were included. The results of the analysis show that 11.1% of articles are in women’s studies; 7.7% in psychology and other related topics in the social sciences; 6.6% in sociology; and 5.4% in geography, in addition to other less represented areas (see Fig. 3).

With regard to the authors, Brush is the author with the highest number of articles published, followed by Welter, and then Thurik—who is a man—and Verheul, as can be seen in Table 4. Notably, research in the area of female entrepreneurship is carried out, in general, by women (Ahl and Nelson 2010).

In terms of authors’ countries of origin, most are from the United States (38.62%), followed by the United Kingdom (9.80%), Canada (6.92%), and Spain (6.34%), as can be seen in Table 5. The cutoff point was 10 articles per country.

In addition, the analyses included origin of author by continent, as can be seen in Fig. 4. The continent with the largest representation of authors is Europe with 193 (55.6%) articles, followed by The Americas with 167 (48.1%).

Mapping knowledge networks: results

At this point, the study sought to deepen the knowledge acquired about the area of female entrepreneurship through lexical and co-citation analyses. These were used to map the knowledge networks in this field, reaching back to the genesis of this research stream.

Lexical network of words analysis

In order to gain a fuller understanding of the dominant themes in the 347 articles on female entrepreneurship in the sample, a lexical analysis was performed on the most frequently found words in titles and abstracts. This procedure generated a tree of words (see Fig. 5) consisting of those that occur most frequently in these texts. The analysis was carried out using TreeCloud software (Gambette and Veronis 2010), which generates “trees” in which the words occurring in the texts under analysis are grouped according to their semantic proximity.

Based on the results of the analysis of the keywords in the 347 articles’ titles and abstracts, three clusters were identified. The first cluster groups together studies focused on the “I” (i.e., female entrepreneur) from a micro and/or individual perspective, in which the motivations, activities, finances, economic development, businesses, and work-family relationships of female entrepreneurs are addressed. The second cluster brings together studies more focused on the creation and management of companies (i.e., a company or meso perspective) while taking into account gender differences in relation to these companies’ organization and results. The third cluster groups together studies with a macro perspective, in which context and knowledge transfer, education, and entrepreneurship are the dimensions under study.

Journal and/or source co-citation analysis

Based on a minimum of 35 citations, a co-citation analysis was conducted on journals and/or sources. Five clusters were obtained for a total of 59 items (see Fig. 6). The central blue cluster has 13 sources, among which stand out Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice and the Journal of Business Venturing as the two most cited journals. Another cluster in red contains 20 sources that include, among others, Small Business Economics, Gender and Society, and Strategic Management Journal. A third cluster in green contains 14 sources, among them Entrepreneurship and Regional Development and Women in Management Review. In the fourth yellow cluster with 12 sources, the Journal of Small Business Management is highlighted, and, finally, a fifth cluster has only two journals: Sociology Ruralis and the Journal of Rural Studies.

Co-citation analysis by first author

An analysis of the co-citation networks by first author (see Fig. 7) verified that 58 authors with a minimum of 30 citations are grouped into three clusters. A strong relationship of internal co-citation connections is evident in the three clusters, and a co-citation network between the three clusters was noted. The red cluster includes Brush, Carter, and Shane. In the blue cluster, Ahl, Marlow, and Bruni stand out. In the green cluster, the most cited authors are Minniti and Verheul.

Analysis by document

At this point, an analysis was conducted on the 115 articles with a minimum of 10 citations, which were grouped into three clusters. A summary of each of the clusters’ characteristics was also developed. Figure 8 represents the three co-citation clusters analyzed by their documents, which are described in the subsections below.

Cluster one: entrepreneurial profile

Cluster one, labeled “Entrepreneurial Profile,” consists of 44 articles predominately from the 1980s (14) and the 1990s (18). The most represented journals are the Journal of Small Business Management with a total of 12 articles (27.2%)—eight of which were published in the 1980s—and the Journal of Business Venturing with a total of 14 articles (31.8%), of which nine appeared in the 1990s (see "Appendix A").

With respect to the authors, only Buttner has three articles; Birley, Carter, Chaganti, and Cromie wrote two articles; and the other authors have an article apiece (see "Appendix A"). Regarding the topics studied, these relate to the differences in characteristics between women and men, including, among other individual attributes, their inherent specificities and profiles, as well as the differences between men and women in company management.

This cluster, which represents the genesis of the female entrepreneurship research stream, encompasses the initial themes related to entrepreneurial characteristics. The articles address issues such as developing profiles based on psychological characteristics (Hisrich and Brush 1984) and motivations in terms of push and pull factors (Buttner and Moore 1997), as well as the work-family dichotomy (i.e., the impact of family responsibilities) (Cromie 1987). Another significant topic is finance, essentially examining companies’ financing and analyzing statistically the main similarities and differences in entrepreneurs’ relationships with credit institutions (Carter and Rosa 1998).

However, these scholars also researched whether women are more risk-averse (Masters and Meier 1988), as well as their management and business strategies, with the authors reporting that women are more conservative in terms of growth expectations. Researchers further found that female entrepreneurs have more modest plans for growth and expansion (Chaganti 1986; Cliff 1998), greater time constraints largely due to family responsibilities (Lee-Gosselin and Grisé 1990), and less robust and more informal business networks than men (Cromie and Birley 1992; Greene et al. 1999). Another research topic is company performance, producing articles in which the authors infer that women value factors such as personal fulfillment, the quest for flexibility, and the desire to serve their community, rather than solely economic indicators (Anna et al. 2000). Table 6 presents more information on the five articles of this cluster with the greatest co-citation weights in the group.

Cluster two: gender identity and theoretical conceptualizations

Cluster two, given the label “Gender Identity and Theoretical Conceptualizations,” consists of 38 articles predominantly (27) published in the 2000s. The journals most frequently appearing are Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, with a total of 12 articles, of which seven appeared in the 2000s, and the Journal of Business Venturing, with four articles. Regarding the authors, only Marlow has three articles, while Ahl, Bruni, de Bruin, and Jennings all published two articles and the other authors only one (see "Appendix B"). The topics of this cluster’s articles include theories, conceptualization of frameworks, future directions for research, new themes or perspectives, along with approaches to networks, the family’s influence on networks, and the glass ceiling, as well as gender differences. In short, these papers largely reflect upon family, structural, and cultural contexts.

At this stage, studies began to focus on consolidating this area of research by using poststructuralist feminist theories in particular. Concurrently, conceptual models were proposed and applied to adapt the concept of female entrepreneurship to new economic contexts (e.g. during financial crises and in developing countries), including the relevance of women’s roles in the global economy both as consumers and entrepreneurs (e.g., Brush et al. 2014).

Cluster two comprises articles of a more conceptual nature, in some cases using less common research methods such as content and discourse analyses (Ahl 2006) or ethnographic studies (Bruni et al. 2004). In general, the authors’ perception was that female entrepreneurship had been analyzed in terms of male entrepreneurship and that the field lacked an approach that gave adequate and autonomous consideration to women’s characteristics. A common practice in these articles was to refer to diverse feminist theories and explain entrepreneurial processes in the light of these theories (Mirchandani 1999; Bruni et al. 2004; Ahl 2006; de Bruin et al. 2007).

In addition, cluster two includes some proposals for new theoretical frameworks, such as Brush et al.’s (2009) article, who stress the importance of the family context (i.e., motherhood) and society’s expectations (i.e., the macro level), as well as of intermediary structures and institutions (i.e., the meso level) in terms of the “3Ms” (i.e., markets, money and management) necessary for entrepreneurs to launch and grow their businesses. Table 7 present the five articles in cluster two with the heaviest weights of co-citations within this group.

Cluster three: the entrepreneurial process context

Cluster three was labeled “The Entrepreneurial Process Context.” This grouping comprises 33 articles, predominately (19) from the 2000s. The most represented journals are Entrepreneurship: Theory & Practice with a total of 11 articles, of which six appeared in the 2000s, and Small Business Economics with a total of 14 articles, including nine published in the 1990s. With regard to the authors, only Norris has three articles, Wilson has two articles, and the other authors have one (see "Appendix C").

This cluster addresses issues of entrepreneurship, stereotypes, cross-country policies, education policies, self-efficacy, entrepreneurial intent, behaviors, opportunity identification, the GEM, countries, entrepreneurial potential, economic growth, and gender differences. Researchers focused on company management, namely, defining strategies for company performance and competitiveness that took into account that markets were becoming more global.

Cluster three contains comparative studies of entrepreneurship between several countries (e.g., Smallbone and Welter 2001; Zhao et al. 2005; Verheul et al. 2006; Langowitz and Minniti 2007), as well as the recognition of opportunities (DeTienne and Chandler 2007; Langowitz and Minniti 2007). Other researchers examined gender perceptions and entrepreneurial intentions (Liñán and Chen 2009; Shinnar et al. 2012). Table 8 presents the five articles of cluster three with the greatest weight of co-citations within the group.

Final considerations

The results of the above analyses of the 347 research-related articles on female entrepreneurship provide a solid theoretical basis for a fuller understanding of this field of research—both worldwide and over the last four decades (i.e., from 1976 to 2016). In general, publication of studies on this topic has increased in the last 10 years and, despite being a small percentage of the universe of all articles published on entrepreneurship, this research has appeared in periodicals of high quality in the field. The articles in question tend to be highly cited, which confirms Jennings and Brush’s (2013) findings.

The results reveal a trend in the last five years toward studies in developing countries, which examine how geographical regions and socioeconomic, cultural, religious, and political aspects (i.e., the context) define the rate of female entrepreneurship and its success. Overall, the challenges faced by women entrepreneurs have been discussed as an issue that is attracting interest in various countries.

The present study adopted a more inclusive search criterion since a systematic review of this field of research cannot be limited to a selection from a predetermined set of periodicals in business and economics. Thus, the results of this literature review provide a comprehensive view of interdisciplinary research on female entrepreneurship not only in the area of management but also other fields of study (e.g., sociology, psychology, and other social sciences) that have addressed this subject since 1976. This approach was applied in order to systematize the literature review and broaden the current understanding of female entrepreneurship.

In part, the increasing academic interest in this topic at the international level can be explained by the higher rate of female entrepreneurship in developing countries; obviously, it is also related—among other factors—to other variables including the impact of the cycle of boom and slump on employment, the growing number of women conducting academic research, and the emergence of more specialized journals (in some of which women play more prominent editorial/refereeing roles). In these economies, women often face multiple barriers to entering the formal job market (e.g., De Vita et al. 2014; Marques et al. 2017). On a social level, the choice to engage in entrepreneurship not only allows individuals and families to escape poverty but also can help women to exploit the emancipatory power of creating their own businesses. This allows women to establish their own identity through professional achievement (Hughes et al. 2012).

On the basis of the results of the co-citation analysis summarized in the three clusters presented above, it is possible to map out three major thematic areas with strong potential for defining future paths of research. Based on the Entrepreneur Profile cluster (i.e., cluster one), a deeper understanding can be acquired of the individual characteristics that have long constituted a dynamic area of knowledge, as they apply (or do not apply) to women’s entrepreneurial intentions and the subsequent success of female-led firms. The Gender Identity and Theoretical Conceptualization cluster (i.e., cluster two) reveals an emerging area that seeks to consider female entrepreneurs holistically as both entrepreneurs and women. The associated articles advocate new theories developed with reference to poststructuralist feminist theories that consider family, networks and culture as differentiating factors. The Entrepreneurial Process Context cluster (i.e., cluster three) comprises studies that address the themes inherent to entrepreneurial processes in different contexts. These include research at the country level, different regions within the same country, and different economies, producing insights that facilitate the implementation of new policies.

This study was restricted to the Web of Science since this is a research database of international articles, including the field of female entrepreneurship. However, this is only one of many possible approaches to bibliometric research, and the present study can be replicated and widened by selecting other databases on the subject to be studied (e.g., Scopus and ScienceDirect). Furthermore, alternative or additional keywords could be selected, and the research domain and/or the disciplinary areas covered could be extended or restricted.

Though the bibliometric analysis reported on here focuses on women’s entrepreneurship in general, rather than on the specificities of innovation in female-led firms, we consider that an assessment of female entrepreneurship from the standpoint of innovation could be of particular value and relevance; indeed, future studies of the interaction between various components of the knowledge value-chain could reveal to what extent gender inequalities limit, distort and/or deflect the ways in which businesses, public enterprises, NGOs and community organizations convert new scientific ideas into practical applications. We also believe that it would also be pertinent to extend the focus beyond the high technology sectors that have already been relatively extensively studied, to women’s entrepreneurship in the creation of media content, in events organization, agri-food production, and health-related and other personal services.

In conclusion, we recognize that, over the last four decades, much has been learned through research on women entrepreneurs, both seen alone and as compared to men. However, just as in the case of women’s entrepreneurship itself, this field of study still has a long way to go.

References

Ahl, H. (2006). Why research on women entrepreneurs needs new directions. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, 30(5), 595–621.

Ahl, H., & Marlow, S. (2012). Exploring the dynamics of gender, feminism and entrepreneurship: Advancing debate to escape a dead end? Organization, 19(5), 543–562.

Ahl, H., & Nelson, T. (2010). Moving forward: institutional perspectives on gender and entrepreneurship. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship, 2(1), 5–9.

Anna, A. L., Chandler, G. N., Jansen, E., & Mero, N. P. (2000). Women business owners in traditional and non-traditional industries. Journal of Business Venturing, 15(3), 279–303.

Bijedic, T., Brink, S., Ettl, K., Kriwoluzky, S., & Welter, F. (Eds.). (2016). Women’s innovation in Germany: Empirical facts and conceptual explanations. Research Handbook on Gender and Innovation. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Bird, B., & Brush, C. (2002). A gendered perspective on organizational creation. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 26(3), 41–66.

Birkner, S., Ettl, K., Ebbers, I., & Welter, F. (eds). (in press). Women’s entrepreneurship in Europe: Multidimensional research and case study insights. London/Heidelberg: Springer FGF Studies in Small Business and Entrepreneurship.

Birley, S. (1989). Female entrepreneurs: Are they really any different? Journal of Small Business Management, 27(1), 7–31.

Bowen, D., & Hisrich, R. (1986). The female entrepreneur: a career development perspective. Academy of Management Review, 11(2), 393–407.

Bruni, A., Gherardi, S., & Poggio, B. (2004). Doing gender, doing entrepreneurship: An ethnographic account of intertwined practices. Gender, Work and Organization, 11(4), 406–429.

Brush, C. G. (1992). Research on women business owners: Past trends, a new perspective and future directions. Entrepreneurship, Theory and Practice, 16(4), 5–30.

Brush, C. G. (1998). A resource perspective on women’s entrepreneurship: Research, relevance and recognition. In Proceedings of the organization for economic cooperation and development (OECD) conference on women entrepreneurs in small and medium sized enterprises: A major force in innovation and job creation (pp. 155–168).

Brush, C. G., de Bruin, A., & Welter, F. (2009). A gender-aware framework for women’s entrepreneurship. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship, 1(1), 8–24.

Brush, C. G., de Bruin, A., & Welter, F. (2014). Advancing theory development in venture creation: Signposts for understanding gender. In Women’s entrepreneurship in the 21st century: An international multi-level research analysis (vol. 11).

Brush, C., & Gatewood, E. (2008). Women growing businesses: Clearing the hurdles. Business Horizons, 51, 175–179.

Buttner, E. H., & Moore, D. P. (1997). Women’s organizational exodus to entrepreneurship: Self-reported motivations and correlates with success. Journal of Small Business Management, 35(1), 34.

Byron, K. (2005). A meta-analytic review of work-family conflict and its antecedents. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 67(2), 169–198.

Caputo, R. K., & Dolinsky, A. (1998). Women’s choice to pursue self-employment: The role of financial and human capital of household members. Journal of Small Business Management, 36(3), 8–17.

Carter, S., Anderson, S., & Shaw, E. (2001). Women’s business ownership: A review of the academic, popular and internet literature. New York: Report to the Small Business Service.

Carter, S., & Marlow, S. (2006). Female entrepreneurship: Empirical evidence and theoretical perspectives. In N. Carter, C. Henry, B. O’Cinniede, & K. Johnston (Eds.), Female entrepreneurship: Implications for education, training and policy (pp. 11–36). London: Routledge.

Carter, S., & Rosa, P. (1998). Indigenous rural firms: farm enterprises in the UK. International Small Business Journal, 16(4), 15–27.

Carter, S., & Shaw, E. (2006). Women’s Business Ownership. Finance, 1, 1–96.

Chaganti, R. (1986). Management in women-owned enterprises. Journal of Small Business Management, 24(4), 19–29.

Chodorow, N. (1978). The reproduction of mothering. Berkeley: University of California.

Cliff, J. E. (1998). Does one size fit all? Exploring the relationship between attitudes towards growth, gender, and business size. Journal of Business Venturing, 13(6), 523–542.

Coleman, S., & Robb, A. (2012). Gender-based firm performance differences in the United States: Examining the roles of financial capital and motivations. In K. D. Hughes & J. E. Jennings (Eds.), Global women’s entrepreneurship research: Diverse settings, questions and approaches (pp. 75–94). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Collins, O. F., & Moore, D. G. (1964). The enterprising man. East lansing: Bureau of business and economic research. East Lansing: Graduate School of Business Administration, Michigan State University.

Cromie, S. (1987). Motivations of aspiring male and female entrepreneurs. Journal of Occupational Behaviour, 8(3), 251–261.

Cromie, S., & Birley, S. (1992). Networking by female business owners in Northern Ireland. Journal of Business Venturing, 7(3), 237–251.

Crossan, M. M., & Apaydin, M. (2010). A multi-dimensional framework of organizational innovation: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Management Studies, 47(6), 1154–1191.

de Bruin, A., Brush, C. G., & Welter, F. (2006). Introduction to the special issue: Towards building cumulative knowledge on women’s entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 30(5), 585–593.

de Bruin, A., Brush, C. G., & Welter, F. (2007). Advancing a framework for coherent research on women’s entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 31(3), 323–339.

DeTienne, D. R., & Chandler, G. N. (2007). The role of gender in opportunity identification. Entrepreneurship theory and practice, 31(3), 365–386.

De Vita, L., Mari, M., & Poggesi, S. (2014). Women entrepreneurs in and from developing countries: Evidences from the literature. European Management Journal, 32(3), 451–460.

Díaz-García, C., Brush, C. G., Gatewood, J., & Welter, F. (Eds.). (2016). Women’s entrepreneurship in global and local contexts. Diana International research network series no 5. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Eagly, A. H., & Steffen, V. J. (1984). Gender stereotypes stem from the distribution of women and men into social roles. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46(4), 735.

Eddleston, K. A., & Powell, G. N. (2012). Nurturing entrepreneurs’ work–family balance: A gendered perspective. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36(3), 513–541.

Edelman, L. F., Manolova, T. S., & Brush, C. G. (2017). Angel investing: A literature review. Foundations and Trends® in Entrepreneurship, 13(4–5), 265–439.

Fischer, E. M., Reuber, A. R., & Dyke, L. S. (1993). A theoretical overview and extension of research on sex, gender, and entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Venturing, 8(2), 151–168.

Ford, M. T., Heinen, B. A., & Langkamer, K. L. (2007). Work and family satisfaction and conflict: A meta-analysis of cross-domain relations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(1), 57–80.

Galindo, M. A., & Ribeiro, D. (Eds.). (2011). Women’s entrepreneurship and economics: New perspectives, practices, and policies. New York: Springer.

Gambette, P., & Veronis, J. (2010). Visualising a text with a tree cloud. In H. Locarek-Junge & C. Weihs (Eds.), Classification as a tool for research (pp. 561–569). Berlin: Springer.

Greene, P., Brush, C., Hart, M., & Saparito, P. (1999). Exploration of the venture capital industry: Is gender an issue. In P. D. Reynolds, W. D. Bygrave, S. Manigart, C. M. Mason, G. D. Meyer, H. J. Sapienza, & K. G. Shaver (Eds.), Frontiers of entrepreneurship research (pp. 168–181). Wellesley: Babson College.

Greenhaus, J. H., & Beutell, N. J. (1985). Sources of conflict between work and family roles. Academy of Management Review, 10(1), 76–88.

Gundry, L. K., Ben-Yoseph, M., & Posig, M. (2002). Contemporary perspectives on women’s entrepreneurship: A review and strategic recommendations. Journal of Enterprising Culture, 10(01), 67–86.

Gupta, V. K., Goktan, A. B., & Gunay, G. (2014). Gender differences in evaluation of new business opportunity: A stereotype threat perspective. Journal of Business Venturing, 29(2), 273–288.

Gupta, V. K., Turban, D. B., Wasti, S. A., & Sikdar, A. (2009). The role of gender stereotypes in perceptions of entrepreneurs and intentions to become an entrepreneur. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(2), 397–417.

Henry, C. (2007). Women Entrepreneurs. In C. Wankel (Ed.), 21st century management: A reference handbook (Vol. 1, pp. 51–59). London: SAGE Publications.

Henry, C., Foss, L., & Ahl, H. (2015). Gender and entrepreneurship research: A review of methodological approaches. International Small Business Journal, 34, 217.

Hisrich, R. D., & Brush, C. G. (1984). Women and minority entrepreneurs: A comparative analysis. In J. A. Hornaday, E. B. Shils, J. A. Timmons, & K. H. Vesper (Eds.), Frontiers of entrepreneurship research (pp. 566–587). Wellesley: Babson Center for Entrepreneurial Studies.

Hughes, K. D., Jennings, J. E., Brush, C. G., Carter, S., & Welter, F. (2012). Extending women’s entrepreneurship research in new directions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36(3), 429–442.

Jennings, J., & Brush, C. (2013). Research on women entrepreneurs: Challenges to (and from) the broader entrepreneurship literature? Academy of Management Annals, 7(1), 663–715.

Jennings, J. E., & McDougald, M. S. (2007). Work-family interface experiences and coping strategies: Implications for entrepreneurship research and practice. Academy of Management Review, 32(3), 747–760.

Kahn, R., Wolfe, D., Quinn, R., Snoek, J., & Rosenthal, R. (1964). Organizational stress: Studies in role conflict and ambiguity. Oxford: Wiley.

Kalleberg, A. L., & Leicht, K. T. (1991). Gender and organizational performance: Determinants of small business survival and success. Academy of Management Journal, 34(1), 136–161.

Kelley, D., Brush, C., Greene, P., & Litovsky, Y. (2011). The global entrepreneurship monitor: 2010 women’s report. Wellesley: Babson College and GERA.

Kelly, R. M. (1991). The Gendered Economy. Newbury Park: Sage Publications.

Keupp, M. M., Palmié, M., & Gassmann, O. (2012). The strategic management of innovation: A systematic review and paths for future research. International Journal of Management Reviews, 14(4), 367–390.

Krueger, N. F., Reilly, M. D., & Carsrud, A. L. (2000). Competing models of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Business Venturing, 15(5), 411–432.

Langowitz, N., & Minniti, M. (2007). The entrepreneurial propensity of women. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 31(3), 341–364.

Larwood, L., & Gattiker, U. (1989). A comparison of the career paths used by successful men and women. In B. Gutek & L. Larwood (Eds.), Women’s career development (pp. 129–156). Newbury: Sage Publications.

Lee-Gosselin, H., & Grise, J. (1990). Are women owner–managers challenging our definitions of entrepreneurship? An in-depth survey. Journal of Business Ethics, 9(4), 423–433.

Liñán, F., & Chen, Y. W. (2009). Development and Cross-Cultural application of a specific instrument to measure entrepreneurial intentions. Entrepreneurship theory and practice, 33(3), 593–617.

Liñán, F., & Fayolle, A. (2015). A systematic literature review on entrepreneurial intentions: Citation, thematic analyses, and research agenda. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 11, 1–27.

Link, A. N., & Strong, D. R. (2016). Gender and entrepreneurship: An annotated bibliography. Foundations and Trends® in Entrepreneurship, 12(4–5), 287–441.

Mari, M., Poggesi, S., & De Vita, L. (2016). Family embeddedness and business performance: Evidences from women-owned firms. Management Decision, 54(2), 476–500.

Marlow, S. (1997). Self-employed women—New opportunities, old challenges? Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 9, 199–210.

Marlow, S., & Patton, D. (2005). All credit to men? Entrepreneurship, finance, and gender. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 29(6), 717–735.

Marques, C. S., Leal, C. T., Santos, G., Marques, C. P., & Alves, R. (2017). Why do some women micro-entrepreneurs decide to formalise their businesses? International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, 30(2), 241–258.

Masters, R., & Meier, R. (1988). Sex differences and risk-taking propensity of entrepreneurs. Journal of Small Business Management, 26(1), 31–35.

McCain, K. W. (1990). Mapping authors in intellectual space: A technical overview. Journal of the American society for information science, 41(6), 433–443.

McCain, K. W. (1991). Mapping economics through the journal literature: An experiment in journal cocitation analysis. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 42(4), 290–296.

McClelland, D. (1961). The achieving society. Princeton: Van Nostrand.

Meyer, M., Libaers, D., Thijs, B., Grant, K., Glänzel, W., & Debackere, K. (2014). Origin and emergence of entrepreneurship as a research field. Scientometrics, 98(1), 473–485.

Minniti, M. (2009). Gender issues in entrepreneurship. Foundations and Trends® in Entrepreneurship, 5(7–8), 497–621.

Mirchandani, K. (1999). Feminist insight on gendered work: New directions in research on women and entrepreneurship. Gender, Work and Organization, 6(4), 224–235.

Moore, D. P. (1990). An examination of present research on the female entrepreneur—Suggested research strategies for the 1990’s. Journal of Business Ethics, 9, 275–281.

Mueller, S. L., & Dato-On, M. C. (2008). Gender-role orientation as a determinant of entrepreneurial self-efficacy. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, 13(01), 3–20.

Poggesi, S., Mari, M., & De Vita, L. (2015). Family and work–life balance mechanisms: What is their impact on the performance of Italian female service firms? The International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation, 16(1), 43–53.

Powell, G. N., & Eddleston, K. A. (2013). Linking family-to-business enrichment and support to entrepreneurial success: Do female and male entrepreneurs experience different outcomes? Journal of Business Venturing, 28(2), 261–280.

Renzulli, L. A., Aldrich, H., & Moody, J. (2000). Family matters: Gender, networks, and entrepreneurial outcomes. Social Forces, 79(2), 523–546.

Ruderman, M. P., Ohlott, K., Panzer, K., & King, S. (2002). Benefits of multiple roles for managerial women. Academy of Management Journal, 45(2), 369–387.

Santos, F. J., Roomi, M. A., & Liñán, F. (2016). About gender differences and the social environment in the development of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Small Business Management, 54(1), 49–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12129.

Schwartz, E. B. (1976). Entrepreneurship: A new female frontier. Journal of Contemporary Business, 5, 47–76.

Sexton, D. L., & Bowman-Upton, N. (1990). Female and male entrepreneurs: Psychological characteristics and their role in gender-related discrimination. Journal of Business Venturing, 5(1), 29–36.

Shelton, L. M., Danes, S. M., & Eisenman, M. (2008). Role demands, difficulty in managing work–family conflict, and minority entrepreneurs. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, 13(03), 315–342.

Shinnar, R. S., Giacomin, O., & Janssen, F. (2012). Entrepreneurial perceptions and intentions: The role of gender and culture. Entrepreneurship theory and practice, 36(3), 465–493.

Small, H. (1973). Co-citation in the scientific literature: A new measure of the relationship between two documents. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 24(4), 265–269.

Smallbone, D., & Welter, F. (2001). The distinctiveness of entrepreneurship in transition economies. Small business economics, 16(4), 249–262.

Stokes, J., Riger, S., & Sullivan, M. (1995). Measuring perception of the working environment for women in corporate settings. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 19(4), 533–549.

Sullivan, D. M., & Meek, W. R. (2012). Gender and entrepreneurship: A review and process model. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 27(5), 428–458.

Teixeira, A. A. (2011). Mapping the (in) visible college (s) in the field of entrepreneurship. Scientometrics, 89(1), 1–36.

Terjesen, S., Elam, A., & Brush, C. G. (2011). Gender and new venture creation. Handbook of research on new venture creation (pp. 85–98). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Thomas, J., Harden, A., Oakley, A., Oliver, S., Sutcliffe, K., Rees, R., et al. (2004). Integrating qualitative research with trials in systematic reviews. British Medical Journal, 328, 1010–1012.

Tranfield, D., Denyer, D., & Smart, P. (2003). Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of systematic review. British Journal of Management, 14, 207–222.

van Eck, N. J., & Waltman, L. (2010). Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics, 84(2), 523–538.

Verheul, I., Stel, A. V., & Thurik, R. (2006). Explaining female and male entrepreneurship at the country level. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 18(2), 151–183.

White, H. D., & Griffith, B. C. (1981). Author cocitation: A literature measure of intellectual structure. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 32(3), 163–171.

White, H. D., & McCain, K. W. (1998). Visualizing a discipline: An author co-citation analysis of information science, 1972–1995. Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 49(4), 327–355.

Wilson, F., Kickul, J., & Marlino, D. (2007). Gender, entrepreneurial self-efficacy, and entrepreneurial career intentions: Implications for entrepreneurship education. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 31(3), 387–406.

Zhao, H., Seibert, S. E., & Hills, G. E. (2005). The mediating role of self-efficacy in the development of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of applied psychology, 90(6), 1265–1272.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix A

Appendix B

Appendix C

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Santos, G., Marques, C.S. & Ferreira, J.J. A look back over the past 40 years of female entrepreneurship: mapping knowledge networks. Scientometrics 115, 953–987 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-018-2705-y

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-018-2705-y