Abstract

I challenge a finding reported recently in a paper by Sotudeh et al. (Scientometrics, 2015. doi:10.1007/s11192-015-1607-5). The authors argue that there is a citation advantage for those who publish Author-Pay Open Access (Gold Open Access) in journals published by Springer and Elsevier. I argue that the alleged advantage that the authors report for journals in the social sciences and humanities is an artifact of their method. The findings reported about the life sciences, the health sciences, and the natural sciences, on the other hand, are robust. But my finding underscores the fact that epistemic cultures in the social sciences and humanities are different from those in the other fields.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Sotudeh et al. (2015) conduct a much needed study to determine if the author-pay model of publishing Open Access that is now used in some scholarly journals leads to a paper being cited more frequently. This is an important issue with implications for research assessment that could affect researchers’ careers. Consequently, Sotudeh et al.’s research deserves our attention and critical scrutiny.

In this short response piece, I argue that there appears to be no benefit for scholars publishing in Author-Pay Open Access journals in the social sciences and humanities. The apparent benefit Sotudeh et al. (2015) report is an artifact of their method of measuring impact. If the single most cited paper is removed from the sample, the reported effect disappears. Thus, social scientists and scholars in the humanities should be reticent to publish Open Access in the author-pay model. There is insufficient evidence that the Author-Pay Model of Open Access is a worthwhile investment for social scientists and scholars in the humanities.

Background

In the Author-Pay Model of Open Access, an author has the opportunity to pay a fee to have their paper published Open Access immediately, even before the paper appears in a print version of the journal. Author-Pay Open Access is often referred to as Gold Open Access. It is contrasted with Green Open Access Published. With Green Open Access Publishing, an author does not pay a fee, but they must wait some period of time stipulated in the Copyright Agreement with the publisher before they make their publication accessible in a personal website or institutional archive. Often the embargo on archiving is 18 months or 2 years. The Author-Pay Model of Open Access Publishing feeds off the hunger of researchers to get cited, both early and often.

As Sotudeh et al. (2015) note, Springer and Elsevier are leaders in implementing this publishing model. But there are now, in addition, many predatory publishers who promise Open Access to authors for a fee, but do not have the reputation that Springer and Elsevier have in academic publishing (see Sotudeh et al. 2015). Importantly, the fees associated with the Author-Pay Open Access model are often quite steep. The Springer journal Synthese, a leading journal in philosophy, for example charges US$3000 or €2200 to publish Open Access. And the Springer journal Social Indicators Research, a social science journal, has the same fees (see http://www.springer.com/gp/open-access/springer-open-choice). In the Humanities and the Social Sciences, researchers often have meager funding to support their research. So such a costly investment would need to yield results if it is to be worthwhile.

Sotudeh et al. (2015) seek to determine if Author-Pay Open Access Publishing is worth the money that authors must pay for it. More precisely, they aim to determine if papers published in this format receive more citations than papers that are not published in this format. Their study focuses on articles published in Springer and Elsevier journals as these publishers publish (1) papers that are Author-Pay Open Access and (2) papers that are not, in the same journal. This provides a control group of sorts for their study.

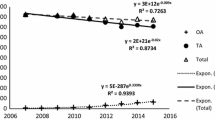

I do not want to recount the details of their study, but it is worth noting that there were greater benefits in the Health Sciences, the Life Sciences, and the Natural Sciences, than in the Social Sciences and Humanities. In fact, Sotudeh et al. (2015) report that there is only a 3.14 % increase in the citations to papers published Author-Pay Open Access in the social sciences and humanities. This finding is grim news for those authors who have bothered to pay the non-negligible fee in order to have their paper published Open Access. The social sciences and humanities do not compare well with other fields. In the Life Sciences, there is an 8.26 % increase in citations for Author-Pay Open Access Publications. In the Health Sciences the increase in citations is 33.29 % for Author-Pay Open Access. And in the Natural Sciences, the increase is 35.95 % for Author-Pay Open Access.

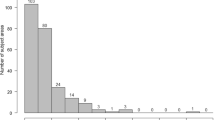

The problem

My concern is that the news is actually even worse than Sotudeh et al. (2015) imply. They report the mean number of citations to papers published Author-Pay Open Access, as well as the number of citations to those papers. They also report the maximum number of citations to a single paper published Author-Pay Open Access. The maximum number of citations to an Author-Pay Open Access Publication in the social sciences and humanities in the authors’ sample is 681 (see Sotudeh et al. 2015, Table 3). The mean number of citations to an Author-Pay Open Access Published paper in the social sciences and humanities in the authors’ sample is 5.92 (see Sotudeh et al. 2015, Table 3).

The authors also provide comparable data for the papers published in the same journals that were not published Author-Pay Open Access. The maximum number of citations to a paper that was not an Author-Pay Open Access Publication in the social sciences and humanities in the authors’ sample is 432 (see Sotudeh et al. 2015, Table 3). The mean number of citations to a paper that was not published Author-Pay Open Access in the social sciences and humanities in the authors’ sample is 5.74 (see Sotudeh et al. 2015, Table 3).

My concern is as followings. I was struck by the fact that the means were so similar, and yet the maximums were so far from the means for both populations. I suspected that the citation advantage that Sotudeh et al. (2015) report may be an artifact of the most cited paper, and not an indication of a citation bonus to either all or most papers published Author-Pay Open Access. That is, the maximums appear to be extreme outliers. They are data points that the typical researcher deciding whether to pay for Open Access should be reticent to consider relevant to their own situation.Footnote 1

To test this hypothesis, I subtracted the value of the single most cited articles in the two groups of publications, Author-Pay Open Access and Traditional, and then recalculated the mean. My calculations are below. The data are drawn from Table 3 in Sotudeh et al. (2015).

-

Author-Pay Open Access

-

13069 citations − 681 citations = 12388 citations

-

2207 papers − 1 paper = 2206 papers

-

Mean citations per paper = 12388 ÷ 2206 = 5.62 citations/paper

-

Traditional

-

233040 citations − 432 citations = 232608 citations

-

40617 papers − 1 paper = 40616 papers

-

Mean citations per paper = 232608 ÷ 40616 = 5.73 citations/paper

As the calculations show, once the most highly cited paper is eliminated from the data set, Author-Pay Open Access papers in the social sciences and humanities are cited on average less often than those that are not published Open Access. This suggests that the apparent citation advantage that Sotudeh et al. (2015) report was just an artifact of the methods they employed.

Incidentally, I made similar calculations for the other fields as well, the life sciences, the health sciences, and the natural sciences. In all those cases the result reported by Sotudeh et al. (2015) was robust. That is, removing the most highly cited paper did not reverse the citation advantage, as it did in the case of the social sciences and humanities.

Discussion

In an earlier study of Open Access Publication, Xia (2010) found that scholars had concerns about this model of publishing (2010, 622). Specifically, they were concerned that such papers were not properly or thoroughly refereed, and that their peers would perceive research published Open Access to be of lesser quality than research published in traditional journals (2010, 622). These attitudes do not in fact accurately reflect the reality of the culture of Open Access Publishing. In fact, as noted above, the notion of Open Access Publishing is applied to a variety of different practices, one of them being the Author-Pay model. And despite the negative attitudes reported by researchers in Xia’s study, more and more researchers are publishing Author-Pay Open Access (2010, 622).

As mentioned above, there are alternative models to the so-called Gold Open Access model, that is, the Author-Pay model. There is what is referred to as “Green Open Access.” In the Green Open Access model “articles that were published in top-tier journals … were converted into OA scholarship because they were self-archived on the authors’ personal websites and/or in institutional repositories” (see Atchison and Bull 2015, 129). In this model the author gets the benefits of having their papers widely accessible without the costs associated with the Author-Pay Open Access model. In fact Antelman (2004) found that in philosophy, political science, mathematics, and electrical and electronic engineering “freely available articles do have greater research impact” (2004, 372).

The Scholarly Publishing and Academic Research Coalition of Europe (SPARC Europe) posts a list of studies investigating “The Open Access Citation Advantage” (see http://sparceurope.org/oaca_table/). There are 15 studies that include data on the social sciences and humanities. Only seven studies report unequivocal citation advantages, whereas six studies suggest that there is no such advantage.Footnote 2

It may seem that Green Open Access is the obvious solution to the problem of ensuring that research is widely read and reaches its intended audience, at least from the researchers’ point of view. But, even the Green Open Access model of publishing is not without its problems. Atchison and Bull note “a large percentage (45 %) of the OA articles … have been posted in violation of the publisher’s copyright and self-archiving policies” (2015, 134). Rightly, journal publishers are far less enamored to this model. It is undermining their revenue, and it fails to recognize the value that academic publishers add to research articles.

We have little reason to believe that there is a citation advantage for publishing papers Author-Pay Open Access in the social sciences and humanities. Perhaps this should not surprise us. The research practices, publication practices, and citation practices in the social sciences and humanities are different from those in the natural sciences, life sciences, and health sciences (for the humanities, see, for example, Wray and Bornmann 2015; for the social sciences see Wray 2015 and Cole 1992, Chapter 5). Social scientists and scholars in the humanities should save their money and resist the temptation to buy into the Author-Pay Open Access Publishing model, a model that may serve other scientific fields well. The traditional publishing model seems to serve social scientists and scholars in the humanities well. Though there is some promise in Green Open Access, the legal issues will need to be resolved.

Notes

It is unfortunate that the authors do not provide either the standard deviations or the means to calculate them. Further, the authors do not provide calculations of the quartiles so that a Box Plot could be constructed. Consequently, when I describe the maximums as extreme outliers I am not using this term in its most technical narrow sense, where extreme outliers are “any measurements beyond the outer fences” in a Box Plot (see, for example, Mendenhall et al. 1999, 78). But studies of citation patterns suggest that the most highly cited papers are outliers. Price (1965), for example, found that “in any given year, about 35 % of all existing papers are not cited at all, and another 49 % are cited only once” (511). In fact, only 1 % of papers are cited six or more times (511).

Two of the studies report the same data, collected by M. Norris for a Ph.D. thesis, and subsequently reported (again) in an article authored with C. Oppenheim and F. Rowland. Though it is one of the 15 studies examining the social sciences and humanities, I only counted it as one study in support of the advantage. One study, by Xu, Liu, and Fang, reports an advantage for most disciplines, but not for the humanities. I did not count it as either finding an advantage or not finding one. The quality of studies varies as well. One of the studies that found there was an advantage, by Zhang, drew data from only two journals in Communication Studies.

References

Antelman, K. (2004). Do open-access articles have a greater research impact? College & Research Libraries, 65(5), 372–382.

Atchison, A., & Bull, J. (2015). Will open access get me cited? An analysis of the efficacy of Open Access Publishing in political science. PS: Political Science & Politics, 48(1), 129–137.

Cole, S. (1992). Making science: Between nature and society. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Mendenhall, W., Beaver, R. J., & Beaver, B. M. (1999). Introduction to probability and statistics (10th ed.). Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole Publishing Company.

Price, D. S. (1965). Networks of scientific papers: The pattern of bibliographic references indicates the nature of the scientific research front. Science, 149, 510–515.

Sotudeh, H., Ghasempour, Z., & Yaghtin, M. (2015). The citation advantage of author-pays model: The case of Springer and Elsevier OA journals. Scientometrics,. doi:10.1007/s11192-015-1607-5.

Springer. http://www.springer.com/gp/open-access/springer-open-choice Accessed on August 12, 2015.

SPARC Europe. http://sparceurope.org/oaca_table/ Accessed December 8, 2015.

Wray, K. B. (2015). History of Epistemic Communities and Collaborative Research. In J. D. Wright (Ed.), International encyclopedia of the social and behavioral sciences (2nd ed., Vol. 7, pp. 867–872). Oxford: Elsevier.

Wray, K. B., & Bornmann, L. (2015). Philosophy of science viewed through the lense of ‘Referenced Publication Years Spectroscopy’ (RPYS). Scientometrics, 102(3), 1978–1996.

Xia, J. (2010). A longitudinal study of scholars [sic] attitudes and behaviors toward open-access journal publishing. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 61(3), 615–624.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks the referees for their astute comments. One referee in particular played a crucial role in making recommendations for the whole paper, but especially the Discussion section. I completed the final revisions to the paper while I was a Visiting Scholar in the Department of Linguistics and Philosophy at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. I thank M.I.T. for their hospitality, and I thank the State University of New York, Oswego, for supporting my sabbatical leave for the 2015–2016 academic year.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

I serve on the editorial board for PLOS ONE, the largest on-line only journal, which exclusively uses the Author-Pay Open Access model. I am an Academic Editor for the journal. I also serve as one of the editors for the Springer journal Metascience, which offer contributors the option of Gold Open Access.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wray, K.B. No new evidence for a citation benefit for Author-Pay Open Access Publications in the social sciences and humanities. Scientometrics 106, 1031–1035 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-016-1833-5

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-016-1833-5