Abstract

The Triple Helix (TH) model and its indicators are typically used for exploring university-industry-government relations prevalent in knowledge-based economies. However, this exploratory study extends the TH model, together with webometric analysis, to the musical industry to explore the performance of social hubs from the perspective of entropy and the Web. The study investigates and compares two social hubs—Daegu and Edinburgh—from the perspective of musicals by using data obtained through two search engines (Naver.com and Bing.com). The results indicate that although Daegu is somewhat integrated into the local musical industry, it is not yet fully embedded in the international musical industry, even though it is international in scope. In terms of social events (i.e., musicals), unlike Daegu, Edinburgh is fully integrated into both the local and international musical industries and attracts diverse domains over the Internet.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Since the 1988 Summer Olympics, South Korea (hereafter “Korea”) has hosted numerous social events and festivals throughout the country to boost its economy through international exposure. For example, social events such as meetings, incentive tours, conventions, and exhibitions (MICE) have been widely acknowledged in Korea as a promising new industry (Heo 2011). Given the recent downturn in the global economy, the Korean government has counted on the tourism industry to play a crucial role in revitalizing the national economy because of its potential for creating jobs and promoting economic growth. Further, the implementation of a local self-government system in the early 1990s has helped to fuel the exponential growth of Korea’s MICE industry. According to Jung (2011), Korea has hosted more than 1,000 regional festivals in the recent decade (Jung 2011). To foster regional economic growth and secure electoral support, Korean mayors and their cities have raced to host international festivals (e.g., the 2018 Winter Olympics in Pyeongchang and the 2011 World Championships in Athletics in Daegu) while developing their own international events (e.g., the Pusan International Film Festival, the Gwangjoo Biennale, and the Hi Seoul Festival).

In this regard, Daegu City (Korea) is a well-known social hub where a number of festivals and social events such as the Daegu International Musical Festival (DIMF) are held every year.Footnote 1 Outside Korea, Edinburgh (the UK), a well-known social hub, is home to the Edinburgh International Festival (EIF),Footnote 2 which represents the city’s musical spirit. Since 1947, the EIF has offered a wide range of cultural events (e.g., musicals) each year (August and September) and attracted large numbers of people from around the world. The DIMF was initiated in 2006 to be the EIF’s Asian counterpart. The primary purpose of the DIMF is to increase Korea’s international exposure and generate economic opportunities, and thus, its events focus on global audiences. In this regard, the present study is guided by the following research questions: How has Daegu’s musical industry performed at the local and international levels? Specifically, how well has Daegu been integrated into the local and international musical industries?Footnote 3 This study employs the Triple Helix (TH) model and its indicators as well as webometric analysis to address these questions.

The triple helix framework

The first TH conference was held in Amsterdam in 1996. Since then, a number of conceptual and methodological studies have measured transformation processes in innovation. These studies can be classified into three categories (Leydesdorff and Etzkowitz 1998). The first category (TH 1) focuses on institutional relationships among academia, industries, and governments and examines how interactions across otherwise closed boundaries are mediated by intermediaries activities. The second category (TH II) measures communication systems consisting of the management of technological innovation, that is, TH II measures the exchange of information among institutions (i.e., university-industry-government) involved in knowledge-based innovation activity. The last category (TH III) examines the emergence of new forms of TH systems by investigating the changing roles of the traditional functions of TH components. However, previous TH research has focused almost exclusively on the trilateral university-industry-government (UIG) relationship. However, as Leydesdorff indicated at the 2011 TH conference at Stanford University, the TH model and its indicators can be applied to various interfaces of any three nodes with different functions. For example, Zhang and Lee (2008) capitalizing on the TH theory suggested that three TH spaces, namely, knowledge, convergence, and innovation spaces are essential to boosting performance of a creative city in the knowledge-based economy (Zhang and Lee 2008).

In this regard, the present exploratory study extends the TH model, together with webometric analysis, to the musical industry (MI) to explore the performance of social hubs (i.e., Daegu and Edinburgh cities) from the perspective of entropy and the Web. The results indicated different types of relationships among TH nodes and have important theoretical and practical implications.

The triple helix framework and the musical industry

The usefulness of the TH framework in the study of the festival industry is rather straightforward from the perspective of some social science theories. According to organizational isomorphism theory (DiMaggio and Powell 1983), the late adopter (i.e., Daegu) is likely imitate the behavior of the early adopter (i.e., Edinburgh) to avoid uncertain social and economic penalties. During this process, the early adopter may make similar efforts to follow competitors’ patterns of behavior for fear of losing their competitive advantage. Therefore, actors with similar functions can be easily compared, and they must continue competing with one another to prevent being replaced by others (for a review of social comparison theory, see (Festinger 1954)). These mutually relevant actors (in this case, events) are those whose “social identity” (Turner and Oakes 1989) is the same as that of individuals wishing to form a network with them. This suggests that the festival industry is based on a complex set of communication relationships among overlapping spheres that increasingly blur the boundaries between actors who are increasingly able to take over the role of others. Because competition tends to create a communication channel through which individuals are exposed to information, the occurrence and co-occurrence of competing actors (e.g., Edinburgh and Daegu) associated with an event (e.g., a musical), when identified through TH indicators, can represent the salience of public perceptions and opinions (Fig. 1).

Methodology

TH indicators

This study analyzes the TH of the MI by using the probability distribution of the terms Daegu (D), Edinburgh (E), and Musical (M). The probability distribution for the MI components (i.e., Daegu, Edinburgh, and Musical) is measured by the mutual information (transmission T) derived from Shannon’s formulas (Shannon 1948). The T-value represents the uncertainty when the probability distributions are combined. For example, according to Shannon (1948) and Shannon and Weaver (1949), the amount of information conveyed by the occurrence of an event is inversely proportional to the probability of that event occurring (Shannon and Weaver 1949), and thus, if the discrepancy is considered to be a probability distribution (Σ i p i ), then the uncertainty associated with the distribution (H) can be defined as follows:

Similarly, the two-dimensional distribution (H ij ) can be written as

where H ij is the sum of the uncertainty associated with the two dimensions of mutual information contained in each probability distribution, that is, the two variations overlap in their covariation and condition each other in remaining variations.

Assume that “d,” “e,” and “m” stand for “Daegu,” “Edinburgh,” and “Musical,” respectively. Then, using information theory, we can write the mutual information in two dimensions by using “T,” the “transmission” between two probability distributions, e.g., Daegu–Musical (DM), as follows:

In Eq. 3, Hdm is zero for completely independent distributions and positive for dependant distributions (Theil 1972). Similarly, the mutual information in three dimensions can be defined as follows (Abramson 1963, p. 129):

Note that the T-values for two dimensions—T(dm), T(de), and T(em) values—are, by definition, positive and that bilateral terms reduce uncertainty, whereas trilateral terms increase it (which prevails at the system level). Further, note that in the case of three dimensional T-values, a negative T-value (i.e., dme) indicates a decrease in uncertainty and an increase in the dynamics of the MI, i.e., the stability of the MI. However, in the case of positive or zero three-dimensional T-values, the stability of the system (in this case, the MI) is not indicated (Leydesdorff 2003; Park and Leydesdorff 2010). There is a decrease in uncertainty when D, E, and M occurs more frequently, which indicates a stable MI.

In the present study, we measured the information available in two (e.g., Daegu–Musical) and three dimensions (Daegu–Musical–Endinburgh) by using the formula provided in Eqs. 3 and 4 (for a detailed mathematical definition, please see Leydesdorff 2006, pp. 238–243). For this, we used the hit counts of the three TH components (i.e., “Edinburgh,” “Daegu,” and “Musical”). As Leydesdorff (2006, p. 243) indicated, search results with the terms reflecting some TH system—together with Boolean operators (e.g., AND and NOT) and advanced options for geographic locations, languages, and domains—can provide relatively straightforward data for applying TH indicators to complex social systems (Leydesdorff 2006) such as the MI.

Webometric impact analysis

In addition to using TH indicators, we conducted a webometric impact analysis (Thelwall 2009) of the MI. Webometric impact analysis is a well established, convenient, and effective tool for examining the effects of a phenomenon over the Internet (Thelwall 2009; Park 2010).

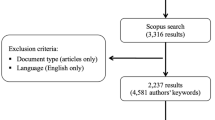

Data

The data were collected using two search engines: Naver.com for testing the Korean MI in the Korean context and Bing.com for testing the Korean MI in the international context. For the former, the data were collected from two types of web sources—webpages and news media sites—because Naver.com provided this categorization. For the latter, no such distinction was made.

Local data

Among local search engines, Naver.com provides the best local representation of the EIF and the DIMF. Naver.com is the most popular internet portal in Korea. Further, among many search engines in Korea, Naver.com provides advanced search options that can generate time series data by using Boolean operators. Thus, we collected hit counts for the three TH components (i.e., “Edinburgh,” “Daegu,” and “Musical”) by using Naver.com with Boolean operators. More specifically, we used Webonaver, a webometric tool for Naver.com developed by the World Class University Webometrics Institute (Lim and Park 2011; Sams et al., forthcoming). Webonaver parses and organizes results returned from Naver.com to provide social scientists with easy access to publicly available data on the Web. Although Google.co.kr has become popular in the Korean mobile market and Microsoft’s Bing.com has established itself as a business partner of Daum.net (the second largest search engine in Korea), Naver.com has maintained its position as the most prominent search engine, attracting approximately 80% of the local traffic. Further, the simultaneous use of an international search engine (i.e., Bing.com) and Naver.com was expected to capture diverse dimensions of communication.

International data

To examine the extent to which Daegu integrated itself into the international MI, we used Bing.com (the global, not local, version) to collect data on the TH components on July 27, 2011. For this, we used Webometric Analyst (a new version of LexiURL), which was developed for social scientists by Thelwall (Zuccala and Thelwall 2006). Bing.com, together with Naver.com, allowed for a convenient analysis of the representation of the Daegu MI at the global level. Bing.com is the only search engine that can automatically process various search queries free of charge and is the primary data-gathering tool embedded in Webometric Analyst.

Results

Korean musical industry: a triple helix analysis (local)

Hit counts: the webpage category

Table 1 show the number of webpages for various combinations of the search terms—i.e., Daegu (D), Edinburgh (E), and Musical (M)—by year. As clearly shown by the table, the number of hits for DM increased gradually from 13 in 2001 to 2,216 in 2010 (the peak). The number of hits for DM increased sharply from 88 in 2005 to 125 in 2006, when the DIMF began. Further, there was a big jump from 125 in 2006 to 2,216 in 2010 (as shown by the bold values). This may reflect people’s increasing interest in the DIMF as well as the DIMF organizer’s efforts to promote the event through the Internet. In 2010, the festival offered four musicals from abroad and six locally organized performances, a twofold increase from 2009 (http://www.imaeil.com/sub_news/sub_news_view.php?news_id=27782&yy=2010). This increased the popularity of the DIMF. The number of hits declined in mid 2011, but this may be because the 2011 data were collected soon after the DIMF ended in 2010. Thus, this decline may be natural. To verify the trend, we collected news articles by using the same queries (Table 2). As shown in Table 1, it is clear that the EIF did not attract much attention from Koreans, that is, EM received far fewer hits than DM.

Hit counts: news media

As shown in Table 2, news articles showed a similar pattern as webpages. For example, the number of hits for DM increased steadily from 614 in 2006 to 3,673 in 2010 (as shown by the bold values). There were no substantial differences in the occurrence and co-occurrence of the other terms (i.e., ED, EM, and EDM).

T-values: testing for systemness in the musical industry

The webpage and news media categories

As mentioned in the Methodology section, we used TH indicators to calculate T-values for the MI. Figures 2 and 3 show the T-values for hit counts for the webpage and news media categories, respectively. The T-values for DM for the webpage category increased steadily from 2006 (when the DIMF started) to 2010, peaking at 0.83 mbits. The other T-values were minimal. The news media category showed a similar pattern. These results indicate that the Korean MI was relatively stable. However, in terms of the three-dimensional probability distribution (i.e., EDM), the T-values were close to zero, indicating no uncertainty in the MI.

Korean musical industry: a webometric impact analysis (local)

The webpage category

Tables 3 and 4 show the results of the webometric impact analysis of Daegu and Edinburgh as musical hubs in the Korean context. The two tables list second- and top-level domains (STLDs) of webpages matching two different queries generated using Naver.com. The first domain column shows the percentage of domains returned by the query “Edinburgh Musical (Daegu)” for the given STLD, and the second domain column summarizes the distribution of domains returned by the query “Daegu Musical (Edinburgh)”. Domains are domain name segments, that is, the part of the URL after “http://” and before the first subsequent slash (e.g., www.bbc.co.uk). We used Webometric Analyst (Zuccala and Thelwall 2006; Park 2010) to process the returned samples of estimated pages to generate a standard webometric report.

Surprisingly, inside Korea, the term “Edinburgh Musical” attracted more STLDs than the term “Daegu Musical” (Table 3). For example, “Edinburgh Musical” was mentioned by 37 co.kr domains, whereas, “Daegu Musical,” by only 17 co.kr domains. In addition, “Edinburgh Musical” attracted diverse domains such as go.kr, re.kr, and ac.kr (Tables 3, 4). Although the hits for these domains were minimal, the results indicate Koreans’ growing interest in international festivals and reflect Edinburgh’s long history as a social hub for musicals. In comparison to Edinburgh, Daegu is a relative newcomer to the festival industry.

The news media category

Edinburgh also led Daegu within Korea in the news media category. As shown in Tables 5 and 6, “Edinburgh Musical” was mentioned by 11.com domains and 6 co.kr domains. “Daegu Musical” was mentioned by only 3.com domains and 2 co.kr domains. Table 6 lists the top 10 news domains for Daegu and Edinburgh. In addition, Table 6 demonstrates the diversity of domains for “Edinburgh Musical.” Given the historical importance of Edinburgh as a social hub, these results are not surprising. However, they also indicate a lack of interest among news outlets in terms of local musical events (i.e., the DIMF) and their tendency to cover international musical events.

Korean musical industry: an international comparison

Webometric impact analysis

Table 7 shows the results of the webometric impact analysis of Daegu and Edinburgh as musical hubs in the international context. The table lists the STLDs of webpages matching two different queries generated using Bing.com. The first domain column shows the percentage of domains returned by the query “Edinburgh Musical (Daegu)” for the given STLD, and the second domain column summarizes the distribution of domains returned by the query “Daegu Musical (Edinburgh).” The results clearly demonstrate Edinburgh’s superiority as a musical hub at the international level. As shown in Table 7, .com accounted for 47.40% of domains for “Edinburgh Musical” and 83.10% for “Daegu Musical.” “Edinburgh Musical” and “Daegu Musical” were mentioned by 249 and 195 domains, respectively. Unlike Daegu, Edinburgh attracted considerable attention from domains inside the UK (83 co.uk domains). “Daegu Musical” (10) attracted more.net domains than “Edinburgh Musical” (5). In addition, “Edinburgh Musical” attracted a diverse range of domains.

In terms of the domains for the query “Edinburgh Musical (Daegu)” (detailed results are omitted because of space limitations), most of the 118.com domains were global Web 2.0 sites and local media outlets. The main.com sites were youtube.com (9 URLs), amazon.com (8) and edinburghtheatreguide.com (8), followed by gumtree.com (5), a famous local media site, and superbreak.com (5), a tour information site. Others included social networking sites such as scribd.com (4), flickr.com (2), and myspace.com (2). In addition, .co.uk, which had the second largest number of domains, included local news media sites such as telegraph.co.uk (9), guardian.co.uk (5), and edinburghfestival.list.co.uk (5), the popular Scottish magazine. Other sites included qype.co.uk (5), adtrader.co.uk (4), and Independent.co.uk (3). The remaining sites included en.wikipedia.org (28), music.ed.ac.uk (17), archive.org (16), entertainment.stv.tv (3), eums.org.uk (3), tripadvisor.com (3), pleasance.co.uk (2), ianrankin.net (2), amazon.co.uk (2), entertainment.timesonline.co.uk (2), getmein.com (2), ticketsoup.com (2), edinburghplayhouse.org.uk (2), graemeepearson.co.uk (2), allgigs.co.uk (2), musicalcriticism.com (2), ed.ac.uk (2), matttiller.com (2), edinburgh-life.com (2), thistle.com (2), ediranfest.co.uk (2), ryanair.com (2), and en.allexperts.com (2).

However, the EIF’s official site, eif.co.uk, and its accompanying site www.edfringe.com retrieved only once. This is not surprising because the query was not very specific to the EIF. The query “Edinburgh International Festival” returned 47.4 million hits, and the number of returned webpages at the URL level was 198. The most frequently indexed URLs were news.scotsman.com (16 URLs, 8.1%), www.eif.co.uk (15 URLs, 7.6%), and www.endiburghguide.com (13 URLs, 6.6%).

Table 8 shows the results for the query “Daegu Musical-(Edinburgh).” The URL column lists the number of URLs returned by the query for the given domain. Consistent with the results for “Edinburgh Musical (Daegu),” most of the 162.com domains were global Web 2.0 sites and local media outlets, including youtube.com (44), amazon.com (15), and scribd.com (13). In addition, wikipedia.org (28) and nymf.org (7) accounted for most of the.org domains. Unlike Endiburgh, Daegu attracted few global social networking sites: myspace.com (3), scribd.com (13), facebook.com (5), and myspace.com (3).

Noteworthy is that, consistent with the results for Edinburgh, the DIMF’s official website, dimf.or.kr, attracted only 2 URLs. The official site had relatively low international visibility. When the search was made more specific through the query “Daegu International Musical Festival,” dimf.or.kr URL did not appear on the URL list. The results of a comparison between eif.co.uk (380,000 hits) and dimf.or.kr (51 hits) based on searches using the two sites as input queries clearly provide a contrasting picture. Table 8 shows other domains together with URLs.

Korean musical industry: a triple helix analysis (international)

Hit counts

Table 9 shows the results of a TH-based search using the terms “Edinburgh,” “Daegu,” and “Musical” for Bing.com. There were 19,735,770 mentions of the EIF but only 105,320 mentions of the DIMF across all domains. There were 63,611 co-occurrences of EMF across all domains. Within the UK, Daegu was approximately 10 times less likely to be mentioned in the UK than in all English-speaking regions combined (2,200 vs. 20,500). This indicates that the DIMF was far less competitive than the EIF at the international level.

T-values: testing for systemness in the musical TH system

To test for the systemness in the musical TH system, we organized the data into two- and three-dimensional array. Figure 4 summarize the interaction between the EIF and the DIMF based on TH indicators. Unlike the bilateral T-values, trilateral T-values were always negative. The absolute values for T(edm) decreased rapidly from the Korean webosphere to international cyberspace. Note that the more negative the three-dimensional T-value, the more dynamic and less uncertain the TH system is, thus it is useful to consider absolute values instead of negative values when interpreting three-dimensional results.

The uncertainty of T(edm) values (measured by English-speaking websites) was −0.018011989 mbits. However, the T(edm) value decreased steadily across all international domains, including.com and.net. Worse, this decrease was −0.004339314 for the UK, which was 10 times less than the highest T-values for Korea (−0.069425565). The rapid and sharp decline in the T-value from the global environment to the UK indicates that the complex social system of international musical festivals on the Web was influenced and reshaped by the addition of a new node: the Korean MI. The negative entropy at the network level did not reduce the level of uncertainty within the system. That is, the inclusion of the Korean MI increased the level of uncertainty on the Web by disrupting the equilibrium centered on Edinburgh. These results indicate that the interaction among Edinburgh, Daegu, and Musical may lead to new means of communication and that the Korean MI has yet to achieve competitiveness at the global level.

Discussion and conclusion

This study makes innovative use of the TH model and its indicators by applying them to the musical industry. More specifically, the study compares the Korean MI (Daegu) with an international musical industry (Edinburgh) by replacing the traditional TH relationship (i.e., university–industry–government) with the Daegu–Edinburgh–Musical relationship.

This study contributes to the literature by applying the TH model and its indicators to different interfaces of the three nodes of TH model with different functions. That is, unlike previous research, which has typically focused exclusively on the traditional university-industry-government relationship, this study extends the TH model and its indicators to the musical industry by using Daegu, Edinburgh, and Musical as the primary nodes.

The results indicate that Daegu was somewhat integrated into the local MI but that it was yet to be fully embedded in the international MI, although the organizers designed it to be international in scope. On the other hand, Edinburgh was well integrated into both the local and international MIs. Further, Daegu’s musical attractiveness was limited to few domains, i.e., it lacked diversity. However, Edinburgh attracted diverse domains from a wide range of communities. For example, DIMF attracted only one.co (i.e., corporation) domain within Korea, whereas EIF attracted several.co domains within the UK This indicates that attracting corporate attention can facilitate MI success.

The differences between Daegu and Edinburgh can be attributed mainly to historical differences between the two cities. That is, Edinburgh has a long history as a social hub, whereas Daegu has only recently promoted various social events to facilitate economic growth by attracting international attention. However, these results have useful implications for organizers of social events, particularly musical events. For example, to maximize the economic and social impact of an event, the organizer should target a diverse range of websites (e.g., social networking sites and commercial sites) as well as some specific domains (e.g., .co).

This study has some limitations. Like citations, web mentions of social events cannot be considered a comprehensive measure of their intrinsic quality but can indicate the level of public awareness for a particular phenomenon (Park 2011). In addition, the occurrence and co-occurrence of search terms were estimated values, and the search engines generally do not provide accurate hit counts. Therefore, the T-values, which used only hit counts, were only statistically valid. However, relatively small errors are randomized for large data sets, and this study’s focus is on demonstrating the use of the TH model and its indicators for the musical industry. Further, we classified Daegu’s local and international presence as two separate phenomena on the Internet by using local and international search engines for the classification. However, because the Internet is a global phenomenon, such a classification method may not produce accurate hit counts for some terms.

Finally, the results suggest that the TH model and its indicators can be applied to various interfaces of any three nodes of TH model with different functions.

Notes

For more information on the DIMF visit: http://tour.daegu.go.kr/eng/event/regular_event/1190488_2507.asp.

For more information on the EIF visit: http://www.eif.co.uk/about-festival/about-festival.

The festival industry may have several types of social events, but we are interested only in musicals taking place in Daegu and Edinburgh (e.g., the DIMF and EIF). Thus, we refer to it as the musical industry (MI).

References

Abramson, N. (1963). Information theory and coding. New York: McGraw-Hill.

DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147–160.

Festinger, L. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations, 7, 117–140.

Heo, J.-O. (2011). The analysis on the difference between participant’s motivation and selection attributes for convention venues. Journal of the Korean Data Analysis Society, 13(3B), 1615–1629. (written in Korean).

Jung, D.-I. (2011). The diffusion and institutionalization of commercialized regional festivals in Korea, 1991–2009. Korean Journal of Sociology, 45(3), 73–99. (written in English).

Leydesdorff, L. (2003). The mutual information of university-industry-government relations: An indicator of the Triple Helix dynamics. Scientometrics, 58(2), 445–467.

Leydesdorff, L. (2006). The knowledge-based economy: Modeled, measured, simulated. Boca Raton, FL: Universal-Publishers.

Leydesdorff, L., & Etzkowitz, H. (1998). The triple helix as a model for innovation studies. Science & Public Policy, 25(3), 195–203.

Lim, Y. S., & Park, H. W. (2011). How do congressional members appear on the web? Tracking the web visibility of South Korean politicians. Government Information Quarterly. doi:10.1016/j.giq.2011.02.003.

Park, H. W. (2010). Mapping the e-science landscape in South Korea using the webometrics method. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 15, 211–229.

Park, H. W. (2011). How do social scientists use link data from search engines to understand internet-based political and electoral communication? Quality & Quantity. doi:10.1007/s11135-010-9421-x.

Park, H. W., & Leydesdorff, L. (2010). Longitudinal trends in networks of university-industry-government relations in South Korea: The role of programmatic incentives. Research Policy, 39(5), 640–649.

Sams, S., Lim, Y. S., & Park, H. W. (forthcoming). E-research applications for tracking online socio-political capital in the Asia-Pacific region. Asian Journal of Communication.

Shannon, C. E. (1948). A mathematical theory of communication. Bell System Technical Journal, 27, 379–423. 623–656.

Shannon, C. E., & Weaver, W. (1949). The mathematical theory of communication. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Theil, H. (1972). Statistical decomposition analysis. Amsterdam: North-Holland Publishing Company.

Thelwall, M. (2009). Introduction to webometrics: Quantitative web research for the social sciences. San Rafael, CA: Morgan & Claypool Publishers.

Turner, J. C., & Oakes, P. J. (1989). Self-categorization theory and social influence. In P. B. Paulus (Ed.), Psychology of group influence (pp. 233–275). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Zhang, M., & Li, X. (2008). The research on creative city based on the triple helix mode. In Proceedings of the 2008 international conference on information management, innovation management and industrial engineering (Vol. 03, pp. 430–433). Washington, DC: IEEE Computer Society.

Zuccala, A., & Thelwall, M. (2006). LexiURL web link analysis for digital libraries. In Poster abstract in Proceedings of the joint conference on digital libraries. Chapel Hill: North Carolina.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the 2011 Yeungnam University Research Grant.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Co-first author—Seong Eun Cho.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Khan, G.F., Cho, S.E. & Park, H.W. A comparison of the Daegu and Edinburgh musical industries: a triple helix approach. Scientometrics 90, 85–99 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-011-0504-9

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-011-0504-9