Abstract

Research has recently emphasized that the non-survival of entrepreneurial firms can be disaggregated into distinct exit routes such as merger and acquisition (M&A), voluntary closure, and failure. Firm performance is an alleged determinant of exit route. However, there is a lack of evidence linking exit routes to their previous growth performance. We contribute to this gap by analyzing a cohort of incorporated firms in Japan and find some puzzles for the standard view. Our empirical analysis suggests that sales growth generally reduces the probability of exit by merger, voluntary liquidation, and also bankruptcy. However, the relationship is U-shaped—such that rapid growth actually increases the probability of exit. More generally, each of the three exit routes can occur all across the growth rate distribution. Large firms are more likely to exit via merger or bankruptcy, while small firms are more likely to exit via voluntary liquidation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Moving beyond a binary distinction of survival vs failure to a richer recognition of heterogeneous exit routes is essential for an accurate understanding of firm exit and bears a number of important implications. Understanding exit routes is important for entrepreneurs and investors interested in learning about their chances of success and the self-esteem and emotional well-being of exiting entrepreneurs, as well as for policymakers in the area of second-chance restart entrepreneurship, to have an accurate understanding of the phenomenon of firm exit. Scholars and policymakers also have a keen interest in verifying the efficiency of “selection pressures” in the economy, i.e. whether the “deserving” successful firms are those that survive and grow, while unsuccessful firms decline and exit. Without distinguishing between exit routes, we may misinterpret the nature, determinants, and consequences of firm exit, which includes both failures and non-failure outcomes.

There is increasing awareness that the exits of firms and entrepreneurs are not all failures (Headd 2003; Harada 2007). An early investigation by Schary (1991) breaks down the phenomenon of firm exit into several exit routes: merger, voluntary liquidation, and bankruptcy. Relatedly, Wennberg et al. (2010) focus on the determinants of four different entrepreneurial exit routes: (1) harvest sale, (2) distress sale, (3) harvest liquidation, and (4) distress liquidation.

Although previous theorizing has suggested that performance is an important determinant of a firm’s available exit choices, previous research has not investigated in great depth the role of pre-exit growth on exit routes. For example, the influential paper by Wennberg et al. (2010) controls for several founder and firm characteristics but not for pre-exit growth. One might expect that rapid-growth firms can achieve IPOs (initial public offerings) and lucrative offers for acquisition, while low-growth or declining firms are more prone to bankruptcy. However, rapid growth may be associated with failure, if rapid growth firms struggle to balance their costs and revenues (Pe’er et al. 2016; Coad et al. 2019; Zhou and van der Zwan 2019). Voluntary exit might be unrelated to the previous growth performance, e.g. if individual’s decisions to retire are independent of the firm’s sales performance or voluntary exit might be negatively related to previous growth performance, e.g. if voluntary exit depends on satisfaction with business performance. We argue that these intuitions and expectations deserve proper investigation.

We focus on “shadow of death” effects on exit routes: in particular, how sales growth—in the years immediately before exit—varies across exit routes. We build on Griliches and Regev (1995) and define the shadow of death as the period of time (about 1–3 years) immediately before exit, for firms who are observed in the data to exit. The shadow of death is of theoretical interest because several firm-specific variables may evolve differently in the years before exit—either because these variables are the outcomes of changing market circumstances or strategic decisions or because they are the causal determinants of exit. In the case of unsuccessful exits, firm performance (as measured in terms of sales growth or profits, for example) may decline in the years prior to exit. In the case of successful exits (e.g. via IPO or through a favorable acquisition), firm performance may enjoy a spectacular take-off in the years before exit. Furthermore, firms may observe their evolving fortunes and change their behavior to choose between alternative exit routes and the option to survive. Griliches and Regev (1995) introduce the shadow of death effect with their finding that firm productivity is low in the years before exit. Almus (2004, p199) reports that German SMEs have lower growth rates when there is “the shadow of death sneaking around the corner” (p199). Subsequent research has investigated the shadow of death effect for productivity (Blanchard et al. 2014; Carreira and Teixeira 2011; Koski and Pajarinen 2015), pre-exit employment (Fackler et al. 2014), and firm performance before a succession event (Diwisch et al. 2006) or a merger (Kubo and Saito 2012).Footnote 1 Kiyota and Takizawa (2007), Kubo and Saito (2012), and Yamakawa and Cardon (2017) investigate shadow of death effects in Japan.

However, only few studies have investigated whether shadow of death effects apply to new ventures, which nevertheless seems worth investigating because new ventures have both volatile growth and also high exit rates across a variety of exit routes. Furthermore, given previous interest in the exit routes available to new ventures (Wennberg et al. 2010), there is a genuine gap in the literature regarding shadow of death effects and firm exit routes. Growth and survival are two of the most important indicators of new firm performance (Miller et al. 2013). We begin with a theoretical discussion that develops some clear and novel predictions for the “standard model” of exit routes, whereby there is a “pecking order” of exit routes, with IPO as the most desirable, followed by M&A, then voluntary liquidation, and with bankruptcy as the least favorable option. Firms with a better growth performance in recent years are eligible for more desirable exit routes. However, in reality, not all exit routes are equally available to firms with different characteristics (e.g. with different sizes). Nevertheless, the disparate availabilities of exit routes to firms of different sizes has received little attention in previous research. Furthermore, there has been little research regarding how exit routes have different meanings in different institutional contexts. In the Japanese context, we discuss that voluntary liquidation is the most relevant exit route for small firms, while large firms are more likely to undergo mergers or bankruptcies.

We contribute to the empirical literature by considering how exit routes are related to previous sales growth. In this study, we investigate shadow of death effects where death is no longer taken as a binary variable (survival vs failure, according to the stereotype) but where various exit routes are taken into account. While there is a considerable literature on exit routes, on the one hand, and shadow of death effects associated with pre-exit growth, on the other hand, nevertheless these literatures have not been combined. We also contribute evidence for the Japanese context. Japan may be an interesting empirical setting in research on exit routes. As pointed out by Peng et al. (2010), in Japan, even when financially insolvent firms decide to file for bankruptcy, courts will scrutinize the case and decide whether to allow certain firms to declare themselves bankrupt. It sometimes takes a long time from application to conclusion (Lee et al. 2007; Peng et al. 2010). In addition, it is often argued that the market for mergers and acquisitions (M&A) in Japan is unique compared with other countries, such as the USA. In Japan, M&A has been used to rescue other firms in financial distress, while it is often regarded as a way to reduce labor costs and therefore to increase profits in other countries. This study shows evidence on how such institutional contexts matter for the probabilities of exit routes.

The findings of this paper can be summarized as follows. Our empirical analysis indicates that sales growth in the years before exit is a significant predictor of exit routes. Non-parametric graphs and statistics, as well as multinomial logistic and complementary log-log regressions, suggest that lagged sales growth generally reduces the probability of exit by merger, voluntary liquidation, and also bankruptcy. However, the relationship is U-shaped—such that rapid growth actually increases the probability of exit. More generally, each of the three exit routes can occur all across the growth rate distribution. Large firms are more likely to exit via merger or bankruptcy, while small firms are more likely to exit via voluntary liquidation.

Sales growth does predict exit routes to some extent. Investors could look at sales growth to have a rough idea of a new venture’s survival prospects. However, growing firms may still exit via bankruptcy or voluntary liquidation, while declining firms still have respectable survival prospects. Our finding that rapid growth, above a certain point, actually increases the probability of exit should be a sobering reminder of the perils of growing too fast. Our results have implications for the interpretation of M&A events in Japan—they are rescue mergers rather than lucrative acquisitions. Our results also show that small firms rarely go bankrupt but are more likely to exit via voluntary liquidation. This could reflect the difficulties that entrepreneurs face if their small firms go bankrupt and could possibly indicate that smaller firms need more forgiving bankruptcy procedures if they are to engage in healthy levels of risk-taking and experimentation.

The paper begins with a theoretical discussion (Section 2) before presenting our data (Section 3). Non-parametric analyses in Section 4 provide a detailed first impression of the relationships between growth and exit, for the various exit routes. Parametric regressions in Section 5 complement our non-parametric results by including control variables and investigating statistical significance. Then, the implications and limitations of our findings are summarized and discussed in Section 6. Section 7 concludes.

2 Background and hypotheses development

2.1 Standard view on exit routes

Research into firm survival has emphasized that there are several distinct exit routes available to entrepreneurs: “entrepreneurs are busy examining varying exit routes” (Wennberg and DeTienne 2014, p5). Entrepreneurs make a “conscious selection of exit strategy from among multiple options” (DeTienne and Cardon 2012, p352). Entrepreneurs face a menu of exit options, among which they make their choices depending on their preferences and degree of risk-taking. Ambitious entrepreneurs who are open to risk-taking might aim for an IPO or M&A exit, while more risk-averse entrepreneurs may have more modest exit strategies (such as planning for a voluntary liquidation). “The exit path that an entrepreneur chooses is important because different paths provide different levels of risk (and thereby potential reward), complexity, and level of potential entrepreneurial engagement after exit.” (DeTienne and Cardon 2012, p355).

Instead of treating exit as a dichotomous variable, the exit routes featured in previous studies include: initial public offerings (IPO), mergers and acquisitions, management buy-outs, employee buy-outs, sale to a third party, sale to another business, voluntary or involuntary liquidation and bankruptcy (Wennberg and DeTienne 2014; Coad 2014).Footnote 2

These exit routes can be arranged into some sort of pecking order according to their desirability, according to what we might call the “standard view.” The best available option for an entrepreneurial exit is an IPO, or a lucrative acquisition (Wennberg et al. 2010, Arora and Nandkumar 2011). Some scholars highlight firm exit via acquisition as a strategic goal towards which firms aspire and that they actively court (Graebner and Eisenhardt 2004; Villalonga and McGahan 2005; Cefis and Marsili 2012). Hence, firms seeking an exit, might first aim for a merger or acquisition (M&A), and if that is not possible, either survive or go for voluntary liquidation. Voluntary liquidations can be a satisfying means for an entrepreneur to exit a business. Examples of voluntary liquidation include a founder’s retirement, a desired career change, or their withdrawal from the business due to illness or injury (Harada 2007; Wennberg et al. 2010). Beyond a certain point, however, perhaps survival and voluntary liquidation are no longer possible and bankruptcy may be the only option. Bankruptcy is a forced closure, the entrepreneur makes no financial gain from the enterprise and may face stiff legal consequences (especially in Japan). If things get so bad that the firm approaches bankruptcy, there may be no option but to quickly seek a distress sale or to voluntarily liquidate or to survive by some radical restructuring of businesses practices. Indeed, bankruptcy is at the bottom of the pecking order.

We therefore consider that firms compete for their preferred exit route, with the best-performing firms achieving the most desirable exits, and firms with worse performance experiencing relatively unattractive exits. Wennberg and DeTienne (2014, p5) write that “performance has an important impact on potential exit routes, the development of exit strategies and the process of entrepreneurial exit (Wennberg et al. 2010).” Therefore, “if researchers wish to empirically test the likelihood of exit, they also need to control for performance (e.g. earnings from self-employment on the individual level or with profitability measures on the firm level), which otherwise would constitute a severe case of omitted variable bias.” (Wennberg and DeTienne 2014, p12). In the present study, we measure performance in terms of a firm’s growth path in the years immediately before exit. Sales growth is one of the main indicators of firm performance (Miller et al. 2013). Firms facing positive sales growth would be expected to exit via more attractive routes than firms with declining sales.

To summarize, then, entrepreneurs and their firms can initially choose between a “multitude” of exit routes that are available to them. However, the exit route that they take depends on their relative performance in the years before exit. The best performing firms, i.e. those with positive sales growth, are more likely to exit via IPO or M&A, while firms with declining sales are more likely to exit via bankruptcy. Firms with stagnant sales are more likely to exit via voluntary liquidation. These notions are represented in Fig. 1.

In the standard view on exit routes, entering firms are characterized by their initial size. Initial size might well proxy for the entrepreneur’s aspiration level. If a firm’s size (e.g. in terms of sales or employees) decreases after entry, this could be perceived as unsatisfactory because firm size ends up below the entrepreneur’s aspiration level. Conversely, if firm size increases after entry, this is probably encouraging because the firm is above its aspiration level. Some fortunate firms will grow after entry, and these firms are more likely to survive. In contrast, firms that perform badly in terms of post-entry growth are more likely to exit, and in the context of economic models of industry evolution, exit is interpreted as a failure (Jovanovic 1982; Levinthal 1991; Le Mens et al. 2011; Coad et al. 2013).

Firms may arguably have more control over their entry size than their post-entry growth.Footnote 3 By this we seek to highlight two ideas: first, that entrepreneurs could potentially delay a premature entry by spending more time to amass resources and knowledge and to persuasively assemble a larger startup team and network of stakeholders; and second, that entrepreneurs seem to have surprisingly little control over their post-entry growth. Many models of industry evolution consider that post-entry growth is determined by a series of unanticipated shocks that are beyond the control of the entrepreneur (in accordance with Gibrat’s Law and Gambler’s Ruin theory, see e.g. Levinthal 1991; Le Mens et al. 2011; Storey 2011; Coad et al. 2013). These models can be generalized to take into account that entrepreneurs have different exit thresholds, such that what might be considered as a satisfactory post-entry growth performance for one entrepreneur can be considered as unsatisfactory for another entrepreneur who has attractive outside options (Gimeno et al. 1997; DeTienne et al. 2015). These models can also be generalized to take into account that entrepreneurs face a variety of exit routes. The most “successful” entrepreneurs (i.e. those with rapid post-entry growth: Jovanovic 1982, Levinthal 1991, Le Mens et al. 2011) may aspire for the most favorable exit routes, such as IPO or a lucrative acquisition, and these exit routes may even be preferable to regular survival. However, post-entry growth depends on a multitude of factors (developing production routines and capabilities, hiring employees, accumulating a customer base, building a brand through marketing, balancing the finances, etc) such that post-entry growth is overall largely unpredictable, and even if entrepreneurs have plans for their exit route, they may not be able to fulfill these ambitions. Few firms would plan to go bankrupt, but bankruptcies often happen. Firms may plan to experience a successful exit (IPO or trade sale), but these optimistic plans are somewhat out of their control and depend on the realized post-entry growth. Hence, considering that entrepreneurs may have little control over their actual post-entry growth performance (Storey 2011), the primary determinant of exit route is not necessarily the planned exit strategy, but rather the realized post-entry growth performance.

Overall, the standard view would consider that:

Proposition 1:

Successful firms have persistent positive post-entry growth and are more likely to exit via M&A or IPO.

Proposition 2:

Firms with a mediocre post-entry growth performance (neither persistent growth nor persistent decline) are more likely to exit via voluntary liquidation.

Proposition 3:

Unsuccessful firms that have persistent decline in the years after entry are more likely to exit via bankruptcy.

Proposition 2, in particular, is not precisely defined: Entrepreneurs who engage in voluntary liquidation might report feeling satisfied with their outcome (Strese et al. 2018). This is because perceived exit performance is not always evaluated solely in terms of personal financial benefits, but exit performance may also be measured in terms of other performance dimensions such as personal reputation, employee benefits, and firm mission persistence (Strese et al. 2018). Contrarily, if a business exit is framed as a successful event, this could be due to an entrepreneur’s optimism, and a desire to “snatch victory from the jaws of defeat,” rather than an objective evaluation with regard to the venture’s initial goals (Marlow et al. 2011; Coad 2014). Ries (2011) writes that entrepreneurs may be quick to repackage a failure as a “learning experience,” irrespective of whether any learning actually took place, to save face and to keep up good appearances in front of investors. We therefore consider it to be an interesting empirical question to see if voluntary liquidations are closer to bankruptcies or to M&As.

2.2 The Japanese context on exit routes

A drawback of the standard model is that not all exit routes are relevant for all firms at the same time. The reality is more complex. To suggest that firms have a choice between exit routes (such as M&A, voluntary liquidation, and failure) is rather like supposing that individuals have a choice between getting married, entering retirement, or dying of a drug overdose, respectively. Yes, individuals face these choices, but they tend not to be susceptible to all options at the same time. Firms engaging in different exit routes differ quite clearly in terms of characteristics such as size. Hence, not all possible exit routes will be simultaneously available to all firms because the availability of exit routes depends on a firm’s circumstances.Footnote 4 In Cefis and Marsili (2012; Table 1), firms that exit by M&A have about twice as many employees, on average, as those that exit via failure, and about half as many employees, as those that exit via restructuring.

Another limitation is that the standard view on exit routes cannot be directly applied to the Japanese case because the institutional context in Japan provides an illustration that exit routes can have different meanings in different institutional contexts. For example, in Japan, bankruptcy is prohibitively punitive for small firms, and many acquisition events are “rescue mergers.” This is no doubt related to the Japanese business culture, which seeks to resolve disputes through dialog rather than recourse to the law (Lansing and Wechselblatt 1983). As a result, firms maneuvering in the shadow of death would seek to settle disputes on amiable terms (e.g. voluntary liquidation or a rescue merger) rather than by facing formal bankruptcy procedures.

Broadly speaking, all of our observed exit routes (merger, voluntary liquidation, and bankruptcy) are considered as “bad news” in the Japanese context because they are closer to failures than successes. Indeed, exit routes have different meanings in different cultural and institutional contexts (Wennberg and DeTienne 2014).

In our dataset, the exit routes are merger, voluntary liquidation, bankruptcy, and a small number of cases of IPO. In the following subsections, we discuss the cases of M&A, voluntary liquidation, and bankruptcy, in the Japanese context. Japan has bank-based rather than equity-based finance for new ventures. IPOs are quite rare, especially for firms (such as those in our sample) aged less than 10 years.

2.2.1 Mergers and acquisitions in Japan

The desirability of selling the firm in the context of an acquisition is not always clearcut. Wennberg et al. (2010) distinguish between a harvest sale and a distress sale. Successful firms get acquired, in which case we might expect rapid sales growth in the years before acquisition. However, distress sales (i.e. acquisition of underperforming firms that are being badly managed) also occur, in which case we might expect a disappointing sales growth in the years before acquisition.

M&As in Japan differ in nature compared with M&As in the USA. Indeed, the significance of merger events varies across countries (Kubo and Saito 2012). Successful exit strategies via M&A are much rarer in Japan than in, for example, the USA (Honjo and Nagaoka 2018). M&As in Japan vary a lot over the business cycle, while bankruptcy is more constant over the business cycle (Kiyota and Takizawa 2007, Fig. 1), and M&As in Japan are countercyclical, whereas in the USA, they are procyclical (Mehrotra et al. 2008). This is because M&As occur to salvage distressed firms, rather than aggressive expansion during economic booms. These are usually not considered to be successful outcomes. In the Japanese context, the term “rescue merger” is often used (Ito 2011; Kubo and Saito 2012) to refer to situations where a merger is set up to recover a distressed firm, after a disappointing performance in the latter that may be due to indisputable mismanagement or incontrovertible strategic mistakes. Indeed, there are many rescue mergers in Japan, more so than elsewhere. In some countries, the category “M&A” refers primarily to acquisitions (e.g., Cefis and Marsili 2012, footnote 4), but in our data, M&A refers primarily to (rescue) mergers. For large firms in Japan, survival is generally considered to be the best outcome.

Firm size is an important dimension when it comes to M&A. M&A events usually involve large firms, not small firms. Small firms in Japan simply do not engage in M&A. According to the Annual Report on Japanese Start-up Business 2016 by Venture Enterprise Center, the number of M&As as an exit mode is much smaller than that of IPOs for Japanese start-ups. One reason why the market for M&A is virtually nonexistent in Japan is because regulations make takeover bids quite difficult (Porter and Sakakibara 2004). In addition, while a merger can be an effective way to reduce labor costs and therefore to increase profits in some countries such as the USA, wage renegotiations after a merger can be difficult and expensive for Japanese firms because of the rigid labor market characterized by long-term employment and seniority-based pay (Kubo and Saito 2012).

We therefore hypothesize:

-

Hypothesis 1: In the Japanese context, (large) firms with mediocre post-entry growth performance are more likely to exit via M&A.

2.2.2 Voluntary liquidation in Japan

In Japan, as elsewhere, there may be a variety of reasons of voluntary liquidation. For example, some managers may want to dissolve their businesses before facing insolvency because they recognize that their businesses are no longer going well (e.g. if sales are in decline). Other managers may be forced to close their companies because they are approaching retirement age and cannot find any successor. In addition, managers that have alternative employment opportunities with higher wages may voluntarily dissolve their businesses. Harada (2007) investigated the reasons for exits of small firms in Japan. The most important reason for voluntary exit was “despairing perception of further business” (Harada 2007; Table 1). He found that while 40% of the exits are economically driven, others are not caused by economic reasons. Among a variety of non-economic-forced exits, aging of managers is the most common reason for exit, followed by illness or injury of the manager.

Perhaps the largest difference in the meaning of voluntary liquidation in Japan, compared with other countries, is that bankruptcy of small businesses is very rare, and therefore the category of voluntary liquidation could include a larger proportion of unsuccessful businesses (“almost bankruptcies”) that are closed shortly before bankruptcy.

We therefore hypothesize:

-

Hypothesis 2: In the Japanese context, (small) firms with a mediocre post-entry growth performance are more likely to exit via voluntary liquidation.

2.2.3 Bankruptcy in Japan

In Japan, there are some cases of firms without solvency that applied for court protection under the Bankruptcy Law, as well as some that applied for it under the Corporate Rehabilitation Law, and the Civil Rehabilitation Law enacted in April 2000 in Japan. In addition, firms whose bills are no longer honored by banks are regarded as bankruptcy even if they are not necessarily judged as bankruptcy by a court. Not only firms legally declared as bankrupt, but also inactive firms from an economic viewpoint, are regarded as bankrupt in Japan. In general, firms try to avoid this, for example, by declaring voluntary liquidation before they get to the point of bankruptcy and by negotiating with creditors to forgive debts and/or to form restructuring plans, with these negotiations being led by the main Japanese banks (Porter and Sakakibara 2004). Large companies can afford bankruptcy, which is a process that takes time and entails high transaction costs of court-adjudicated procedures (Porter and Sakakibara 2004) that may have a considerable fixed-cost component, but bankruptcy is not a reasonable option for small firms (Harada 2007). Since bankruptcy has strong legal implications, small firms do everything they can to avoid it (Kato and Honjo 2015), and they usually opt for voluntary liquidation instead (Harhoff et al. 1998).

The business culture in Japan prioritizes social harmony and often seeks to resolve disputes through dialog instead of taking formal recourse to the law. On the one hand, this is because, for historical reasons, a monopoly on the training and graduation of lawyers, prosecutors, and judges has led to a dearth of lawyers, which discourages the use of the Japanese legal system, and means that many individuals do not appear to have recourse to the law (Lansing and Wechselblatt 1983). On the other hand, being defined as a bankrupt entrepreneur can have strong implications of failure, and the Japanese culture prefers compromise or conciliation to being defined as a failure or loser (Lansing and Wechselblatt 1983).

To summarize, in the Japanese context, survival is the best option for large firms as well as small firms. For small firms, acquisitions as a successful strategic exit are rare in Japan, rarer than exit via IPO, and rescue mergers are not relevant if the firm is small. Small firms seek to avoid bankruptcy at all costs. Instead, the only appealing exit option for small firms would be voluntary liquidation. For large firms, rescue mergers can be a useful option to sell their assets if the firm encounters difficulties, and bankruptcy is the worst possible outcome. For large firms, voluntary liquidation is not really an option because it essentially involves selling the (huge collection of) assets in a deal that would resemble a rescue merger.

We therefore hypothesize:

-

Hypothesis 3: In the Japanese context, (large) firms with severe post-entry decline are more likely to exit via bankruptcy.

Figure 2 summarizes the hypothesized exit routes available to small and large firms in the Japanese context.

3 Data

The data used in this study comes from COSMOS2 based on credit investigation by Teikoku Databank Ltd. (TDB). This data source covers more than half of incorporated firms in Japan. Sole proprietorships are not included in the dataset because the credit investigation company relies on the official register of corporations and thus does not include sole proprietors. Instead, the sample focuses on joint-stock companies, which generally account for a disproportionately large economic contribution in comparison with sole proprietors. COSMOS2 has some advantages over other data sources. For example, COSMOS2 contains detailed information on firms’ exit routes. In particular, information on voluntary liquidation is not available from other databases, including government statistics.Footnote 5 In addition, COSMOS2 includes firm-level variables such as annual sales and founder’s personal attributes.

Firms in the dataset are from manufacturing, software and information services, other services, movie and video production, and postal and telecommunication services sectors and are founded between 2003 and 2010. The dataset includes information on the survival and exit of such firms from their year of entry until the end of 2013. Firms founded in 2003 are therefore visible in all periods until 2013 (unless they exit before 2013 and hence leave the sample early), while companies founded in 2010 are only included in the data for a maximum of 4 years (because the sample ends in 2013).

3.1 Dependent variables: Exit routes

The data provides information not only on whether a firm exits, but also its exit route (merger, voluntary liquidation, and bankruptcy). However, some firms may leave the sample during the observation period for a variety of reasons. For example, some firms may refuse investigation by the credit investigation company. These firms are included in the sample until the year before they are censored. Besides information on survival and exit, this source provided information on founder-, firm-, industry-, and region-level characteristics, such as the founder’s educational background, the firm’s sales, industry code, and location. Previous work using the same database includes Kato et al. (2017).

As for exit route, we classify exits into three routes—merger, voluntary liquidation, and bankruptcy, using the classifications in COSMOS2. Merger describes the situation in which a firm disappears owing to a merger with another firm. Voluntary liquidation indicates the situation where firms voluntarily dissolve their businesses without insolvency. A number of reasons may exist for voluntary liquidation, although their precise definition can be difficult. Bankruptcy is the situation in which firms cannot repay their debt and thus cease operations, and includes firms that apply for court protection under the Bankruptcy Law, as well as those that apply for it under the Corporate Rehabilitation Law or the Civil Rehabilitation Law. Additionally, when banks stop providing credit to service bills payable, firms are considered bankrupt even in the absence of a court judgment. That is, we here define bankruptcy to include not only firms legally declared bankrupt but also those that are inactive economically.

3.2 Independent variable: lagged growth

Our data includes information on a firm’s annual sales, although these numbers for annual sales may be approximated by rounding.Footnote 6Lagged growth is measured in terms of sales by taking log-differences from 1 year to the next (Törnqvist et al. 1985). The greater granularity of total sales, compared with number of employees, helps the precision of our estimations (Shepherd and Wiklund 2009).

3.3 Control variables

Firm size has long been known to have an effect on survival (Levinthal 1991), with the benefits of size being especially crucial for small firms (variables log sales and log sales2). Size as well as growth have an influence on survival, although it has been observed that the effect of size on survival decreases when taking lagged growth into account, suggesting that dynamism matters more than sheer size for survival (Cefis and Marsili 2005; Coad et al. 2013). Similarly, firm age is known to affect survival because young firms face various “liabilities of newness” (Stinchcombe 1965). Founder age is expected to have an overall positive relationship with new venture survival (Baù et al. 2017), with survival rates being lowest among the young and inexperienced (Parker 2018). Hence, we control for founder age as well as founder age2 to control for possible decreasing returns to experience (de Jong and Marsili 2015). The gender of the founder is controlled for (Male founder) because of suggestions that gender affects new venture survival (Klotz et al. 2014). Founder’s education may reflect differences in human capital and entrepreneurial skills and capabilities, and therefore it is controlled for to recognize its potential influence on survival rates (Parker 2018). Region and industry dummies (Region and Industry) are included in our regressions (Ahlers et al. 2015) to control for region-specific and industry-specific components of survival and firm performance (e.g., Dencker et al. 2009; Botham and Graves 2011). Furthermore, to control for the possible influence of time-varying macroeconomic shocks on survival, we include cohort dummies (Sedlacek and Sterk 2017).

4 Non-parametric analysis

4.1 Summary statistics on exit routes

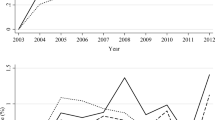

Table 1 shows the exit events from the first year onwards.Footnote 7 Exit events are generally quite rare in our data. Previous research has shown that up to 50% of firms exit after their first 3 years (e.g., Bartelsman et al. 2005; Coad 2018). One reason for the low exit rate in our data is that COSMOS2 is based on the company register that does not include sole proprietorships. Our sample is limited to joint-stock companies that are relatively large compared to firms analyzed in previous literature. For none of the exit routes does the number of exit events peak in the first year. Exits in the first year are rare for each of the three exit routes. Instead, an initial “honeymoon” period is seen for each exit route. Merger and bankruptcy both peak in the 3rd year. Voluntary liquidation peaks in the 4th year.

4.2 Exit events and firm size

We pursue our analysis with some exploratory non-parametric quantitative analysis, which can be a useful tool for entrepreneurship researchers who are interested in the phenomenon at hand (i.e. sales growth and exit routes) rather than with a narrow focus on theory testing (Wennberg and Anderson 2019). Exploratory quantitative analysis can help to clearly visualize underlying relationships and to appreciate the potential relevance of outliers.

Figure 3 presents a preliminary non-parametric perspective on the relationship between exit routes and firm size, to investigate whether certain exit routes are more relevant for small firms or large firms (as highlighted in Fig. 2). Figure 3 shows how the exit routes vary according to size. The main finding is that the option of merger is only relevant for firms that are relatively large. Voluntary liquidation is more relevant for the smallest firms.

4.3 Rapid growth and type of exit

It is theoretically interesting to investigate whether the probability of survival varies over the growth rate distribution. Firms facing rapid decline may be more likely to exit on unfavorable terms. Growth may be positively related with survival, overall. However, excessive growth could lead to financial problems (such as difficulties in keeping a balance between incoming cashflow and rising costs), possibly suggesting that rapid growth could increase the likelihood of an exit on unfavorable terms.

An important methodological choice relates to the relevant number of years of growth history. Are 2 years sufficient, or would 4 years be better? Or perhaps all years since start-up? There is a tradeoff between having longer growth history (fewer observations) and focusing on a shorter history (if longer lags are not significant). Overall, we select a model with 2 lags of annual growth rates, in keeping with previous literature (e.g., Kubo and Saito 2012). The 3rd lag of sales growth is not statistically significant in our analysis (Fig. A1 in the Appendix).

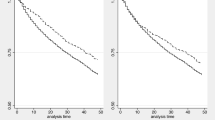

Figure A2 in the Appendix shows the growth rate distribution. Most firms have a growth rate of close to zero, although some firms have relatively rapid growth or decline, and the “tent-shape” suggests a good fit to the Laplace (or symmetric exponential) density. Figure 4 shows that the probability of exit varies over the growth rate distribution.Footnote 8 Bankruptcy is more likely for firms experiencing rapid decline, in line with expectations, although it is interesting that the probability of bankruptcy is positive across the growth rate distribution, such that even firms with moderate or rapid growth are vulnerable to exit via bankruptcy. Indeed, even rapid-growth firms face risks of bankruptcy, if they struggle to maintain a balance between their costs and their incoming revenues (Brännback et al. 2014).

The results for voluntary liquidation are similar to those for bankruptcy: exit routes are higher for firms experiencing rapid decline but are positive across the growth rates distribution. With regard to merger, the probability of exit is remarkably constant across the growth rates distribution. It seems that exit by merger is quite unrelated to a firm’s recent growth performance. This is puzzling from the perspective of our theorizing in Sections 2.1 and 2.2.

Figure 4 motivates the inclusion of a quadratic term for growth in our exit regressions, in keeping with previous studies (e.g., Coad et al. 2019; Zhou and van der Zwan 2019) because the relationship between growth and survival displays an inverted-U relationship, with a peak in the center of the growth rate distribution.

4.4 Growth paths analysis

Table 2 below shows the pre-exit growth paths and survival rates for each exit route (following the methodology in Coad et al. 2013). Two consecutive periods of decline (below-median growth) are associated with highest frequencies of all exit events: merger, voluntary liquidation, and bankruptcy. The highest survival rates are associated with two consecutive periods of above-median growth for each of the exit routes (Fig. A3 in the Appendix). However, exits are observed for each configuration. Even firms with consistent above-average growth can sometimes exit via merger, voluntary liquidation, or bankruptcy. This is a reminder that bankruptcy is not necessarily brought on by decline, but instead it occurs because of an imbalance between revenues and costs.

One observation from the analysis in Table 2 is that we have many medians (growth = 0). This is due to the nature of the data collection. Another issue is that the proportion of firms exiting is rather low, which may be seen as a limitation of the dataset, although previously published work has used this data to investigate firm survival and exit routes (e.g., Kato et al. 2017).

5 Parametric analysis

5.1 Regression analysis: All firms

We examine the effects of lagged sales growth on subsequent survival according to exit route. We begin with a regression for all exit routes pooled together. This is done using a logit duration model (Wiklund et al. 2010; Coad et al. 2013), where the dependent variable is a dummy variable for survival or non-survival. Our regressions for the competing risks of having different exit routes are done using discrete-time survival models in the form of multinomial logit regressions (Schary 1991; Wennberg et al. 2010; Cefis and Marsili 2011, 2012; Ponikvar et al. 2018),Footnote 9 where the dependent variable corresponds to either survival, or one of the three exit routes (merger, voluntary liquidation, and bankruptcy).

Our main independent variables of interest are lagged sales growth, including also the quadratic term because our non-parametric analysis (in Fig. 4) suggested that the relationship between sales growth and exit is non-linear. We include a fairly standard set of control variables, in an attempt to control for possible confounding influences on the relationship between growth and exit route. These control variables include firm size (proxied by the logarithm of sales, including also its quadratic term), firm age, founder age (and its quadratic term), gender, and founder’s education; and also cohort, region, and sector dummies. The previous literature has shown that these variables are associated with firm exit rates, and therefore we control for them in our regressions. Table A1 in the Appendix presents information on the definitions of the variables, and Table A2 in the Appendix presents some summary statistics. Table A3 in the Appendix shows the correlation matrix of variables. Table A4 in the Appendix shows summary statistics for the independent variables according to exit status (survival, merger, voluntary liquidation, and bankruptcy).

It is possible that one exit route will censor the firm from experiencing a different type of exit route. Hence, an assumption is that the probability of any exit route is independent of experiencing a competing exit route. This assumption has been made in the previous literature and is especially reasonable in our case because the probabilities of each exit route are all quite low (exit events are rare in our data).

Table 3 reports the baseline regression results using the multinomial logit model for different exit routes. The explanatory power is rather low (the pseudo-R2 is around 0.06), which suggests that it is not easy to predict exit routes using our variables. In our first model (Table 3 columns (i)–(iii)), the only significant result for the first lag of growth is that growth reduces the likelihood of voluntary liquidation.Footnote 10 Regarding lag selection, the results in Table 3 show that the second lag is statistically significant (most notably the second lag of growth reduces the chances of exit by merger), but further investigation shows that the 3rd and 4th lags are not significant (results not shown in detail here). It suggests, at least in our sample, that the growth history going back 2 years (not more) is sufficient to estimate a firm’s survival chances and exit route. In addition, the results suggest that there is a U-shaped relationship between lagged sales growth and exit. For lagged sales growth, log sales, and founder age, we confirmed that the peaked points in the U-shaped relationship fall in the relevant range based on the significant coefficients of linear and quadratic terms.Footnote 11

5.2 Regression analysis: small vs large firms

This subsection more directly tests the ideas in Fig. 2. We distinguish between large and small firms in terms of whether they are above or below the median size (in terms of number of employees) in the first period of observation.Footnote 12 Table A5 in the Appendix shows some summary statistics for the subsamples.

Table 4 presents the results of multinomial logit regressions that show how lagged growth relates to the various exit routes for subsamples of below-median and above-median initial size. For the below-median subsample, Table 4 shows that the second lag of growth is negatively associated with voluntary liquidation,Footnote 13 while no such effect exists for the subsample of larger firms. This is consistent with our hypothesized relationship in Fig. 2 because voluntary liquidation is an exit route that is more relevant for smaller firms and that smaller firms can stave off this threat if they are able to grow. The growth rates of large firms are negatively associated with bankruptcy, which indicates that large firms that experience declining sales are particularly vulnerable to bankruptcy. No such linear effect was found for small firms, although a positive coefficient on the quadratic term for the second lag of growth suggests that small firms that have either rapid decline or excessively-fast growth are more likely to exit via bankruptcy. In addition, Table 4 shows some evidence that growth rate is negatively related to exit via merger in both subsamples.

Finally, Table 4 shows that firm age reduces the probability of exit only in the case of exit by voluntary liquidation, not for the cases of merger or bankruptcy. Older firms are therefore less likely to exit by voluntary liquidation. We can contrast our results with the propositions of the “standard model” discussed in Section 2. Proposition 1 is not supported because merger rates seem to be higher among declining firms than among growing firms. There is more support for propositions 2 and 3 because the exit rates for voluntary liquidation and bankruptcy are higher for firms experiencing decline in the years before exit. Moreover, voluntary liquidation does not seem to correspond to a particularly “successful” outcome.

The R2 statistics in Table 4 are quite low, ranging from 6 to 9%. Although we have found some interesting predictors of exit routes, nevertheless there is a lot of unexplained variation in exit routes.

5.3 Robustness analysis

The robustness of our results was verified in a number of ways. First, we repeat our previous regressions with an alternative independent variable “growth since startup” as a replacement for the first and second lags of a firm’s growth rate. “Growth since startup” is calculated as the overall post-entry growth (i.e. the log-difference of final size and initial size), scaled down by the number of years.Footnote 14 Our theoretical discussion suggested that, after a firm has entered an industry, its post-entry growth performance provides information on the exit routes available to entrepreneurs. Firms that consistently grew rapidly since entry may be eligible for a successful exit such as a lucrative M&A (or perhaps an IPO), whereas firms that declined since entry may be vulnerable to bankruptcy or perhaps a voluntary liquidation on unfavorable terms. However, it was not theoretically clear whether it is a strong track record of consistently high growth since startup, or growth in the most recent years (which is the approach taken in the “shadow of death” literature, e.g. Griliches and Regev 1995), that is the most important for exit routes.

Tables 5 and 6 present these regression results. Multinomial logit regressions in Table 5 show that positive growth rates since startup will reduce the probability of an exit via merger. This suggests that exit via merger is an unfavorable exit route in our sample. Table 6 disaggregates by firm size (below-median vs above-median start-up size) and further investigates the relationship between post-entry growth and exit. For small firms, there is a statistically significant quadratic effect for post-entry growth and exit via bankruptcy, which seems to explain the quadratic effect for bankruptcy found in Table 5. Small firms are more likely to go bankrupt if they experience either rapid decline or rapid growth—instead moderate growth allows small firms to avoid bankruptcy. Table 6 also shows that growth since startup is negatively associated with exit via merger, in the subsample of relatively large firms.

Second, we explored whether longer lags of growth were significantly associated with exit routes. We repeated the regressions with 3rd and 4th lags of growth rates, but these longer lags were not statistically significant. Third, we repeated the analysis by dropping observations of sales growth in the first year because of concern about possible partial year effects (Bernard et al. 2017). The results were qualitatively unchanged. Fourth, we complemented our multinomial logistic regressions with a complementary log-log model (Cefis and Marsili 2012). The results, presented in Table A6 in the Appendix, are generally consistent with those using the multinomial logit model.

Fifth, we attempt to correct for potentially large heterogeneity between startup experiences. A limitation of this database is the inability to distinguish between entry modes, such as comparing independent startups and spinoff startups. Spinoffs may well be expected to start larger than independent startups. Therefore, we check the robustness of our results after dropping the largest companies. Start-up size is approximately lognormally distributed, with no clear threshold at which a distinct category of “large firms” appears. We therefore undertake robustness analysis by dropping the largest 5% of firms. The results obtained are similar.

6 Discussion

6.1 Summary of the results

There is growing recognition that entrepreneurial exit events are not all failures but that there are different categories of exit events and that some correspond to successful “harvest”-type exits (e.g., Wennberg et al. 2010). These exit routes are assumed to depend on pre-exit performance. However, there is a lack of evidence on how firm performance evolves in the years immediately before exit, for different exit routes. Is it possible to detect early signals of whether a firm will be acquired or bankrupt? Can cases of voluntary liquidation be predicted in advance? We contribute to the literature by investigating how sales growth evolves in the years before exit.

We begin by formulating what we call the standard view on pre-exit growth across exit routes. According to this view, there is a pecking order of exit strategies, chief among which is an IPO exit, followed by M&A, then voluntary liquidation, and the least desirable exit is via bankruptcy. Firms seek the best available exit, and firms with the best post-entry growth performance are more likely to experience more favorable exits. We then adjust this standard model to the case of Japan. Indeed, we reiterate previous suggestions that the cultural and institutional context matters with regard to interpreting the significance of exit routes (Wennberg and DeTienne 2014). In the Japanese context, all of the exit routes (merger, voluntary liquidation, and bankruptcy) are generally considered to be bad news—being closer to failure than to success.

Sales growth in the recent past is more important for explaining exit routes than the average growth since startup. Our analysis suggests that focusing on the 2 years before exit is sufficient for capturing the main shadow of death effects in our context. Adding further lags does not help to significantly predict exit routes in our sample. This casts doubt on the idea that entrepreneurs can formulate and implement long-term strategies for growth paths and exit routes. Instead, it suggests that firms react to their observed growth path by opportunistically re-evaluating their exit route options. Non-parametric graphs and statistics, as well as multinomial logistic and complementary log-log regressions, suggest that sales growth generally reduces the probability of exit by merger, voluntary liquidation, and also bankruptcy. However, the relationship is U-shaped—such that rapid growth actually increases the probability of exit. More generally, each of the three exit routes can occur all across the growth rate distribution. Large firms are more likely to exit via merger or bankruptcy, while small firms are more likely to exit via voluntary liquidation. Firm age reduces the probability of exit only in the case of exit by voluntary liquidation.

Our analysis suggests that, overall, sales growth in the years before exit is a significant predictor of exit routes. Merger and voluntary liquidation are overall closer to “failures” than successful exit strategies in our dataset and in our institutional context. Growing firms have overall lower chances of bankruptcy, as might be expected. Overall, the growth performance of firms can help predict which exit route a firm will take, taking into account that not all exit routes are relevant for all firms at the same time and also that the interpretation of exit strategies differs across cultural and institutional contexts.

6.2 Practical implications

Some practical implications can be mentioned. By taking into account exit routes, we provide evidence on how rapid growth relates to exit routes. It is important for entrepreneurs and investors, as well as for policymakers in the area of second-chance restart entrepreneurship, to have an accurate understanding of the phenomenon of firm exit. In contrast to the standard view on exit routes, our findings suggest that growing fast generally reduces the probability of exit regardless of the exit route. Our findings also indicate that rapid growth increases the probability of exit through merger or bankruptcy. As discussed earlier, successful exit strategies via M&As are much rarer in Japan than in the USA (Honjo and Nagaoka 2018). Rapid-growth firms are less likely to exit via M&As in Japan. From a viewpoint of public policy, a market for M&As should be developed to provide entrepreneurs with more incentives to expand their businesses. In addition, our findings suggest that new firms with rapid growth often go bankrupt, perhaps because they face a lack of cash to balance costs (including wages) with revenues. While it may take some time to get cash from sales, rapid-growing firms cannot obtain enough capital to cover their costs from the capital market. This suggests that there is a room for policy interventions to improve capital market imperfections. The Annual Report on Japanese Start-up Business 2016 by Venture Enterprise Center shows that the scale of venture capital (VC) investments in Japan is much smaller than in the USA, while VC plays an important role in funding entrepreneurs at the seed and early stages. Developing the markets for start-up financing, including VC funding, could foster the emergence of high-growth firms.

In addition, the findings of this study indicate that there are sharp differences in exit options between large and small firms in the Japanese context. For large firms, on one hand, rescue mergers can be a useful option to sell their assets if the firm encounters difficulties, and bankruptcy is the worst possible outcome. However, voluntary liquidation is not really an option for large firms. For small firms, on the other hand, the only exit option may be voluntary liquidation. Survival is the best option both for large and small firms. These findings suggest that the cost of entrepreneurial exit in smaller firms is higher compared with larger firms. While bankruptcy laws that reduce the cost of entrepreneurial exit may increase the level of entrepreneurship in a country, bankruptcy laws that increase the cost of such exit may reduce the level of entrepreneurship in a country (Lee et al. 2007, 2011). To achieve economic growth through entrepreneurship, policy makers should consider entrepreneur-friendly bankruptcy laws especially in countries (such as Japan) with a low start-up rate (e.g., Honjo 2015).

6.3 Limitations and future avenues of research

While this study showed that lagged sales growth is an important predictor of exit routes in new firms, it has some limitations. In this study, IPO as a route to exit is not analyzed in regressions, while it is an important exit strategy for a small number of high-impact new firms in Japan (Honjo and Nagaoka 2018). Further analysis including IPO as an alternative exit route would help our understanding of factors determining exit routes since little is known about how IPO differs from the other exit routes. Also, there may be concerns about the external validity of our results, for two reasons. First, this study focused on new incorporated firms in Japan, and sole proprietorships were not included in the sample. Second, the institutional context in Japan may differ from that of other countries, which may affect the nature of the exit routes (as discussed in detail in Section 2.2). Replication studies using data including sole proprietorships are therefore warranted to reinforce the findings of this study. Replication studies from other countries are also welcome because the institutional context has a large impact on the nature and characteristics of exit routes. For example, harsh bankruptcy laws in Japan may pressurize smaller firms into exiting via voluntary liquidation instead of bankruptcy, whereas in other countries, bankruptcy may be more tolerated and more common. Furthermore, M&A events in Japan often correspond to rescue mergers of struggling giants, whereas in other countries (such as the USA), M&A events are often lucrative exit routes offered to high-potential technology firms.

This study examined the role of sales growth on subsequent exit route. Sales is a well-established indicator for the analysis of firm size and firm growth (Shepherd and Wiklund 2009). However, alternative indicators of pre-exit performance are worth investigating. It is conceivable that sales could grow while profits and productivity decrease. Entrepreneurs with an interest in wealth generation (and the associated exit routes) may prioritize growth of profits rather than growth of sales. In contrast, it could be the case that ambitious entrepreneurs with transformative opportunities need to make large-scale investments before being able to reap the benefits, therefore experiencing temporary low profits alongside attractive longer-term prospects (as reflected by the firm’s potential on IPO or acquisition markets). Therefore, future research could investigate how productivity growth and profits growth relate to subsequent exit routes.

Another potential limitation relates to our low predictive power. Our regressions showed that some variables—including a prominent role for previous growth—help to explain a firm’s exit route. Overall, however, the predictive power of the regression models—as reflected by the pseudo-R2 statistics of model fit—is rather low. We interpret this as evidence that firms are heterogeneous with regard to how their growth paths are linked to their exit strategies. Within the category of failed entrepreneurs, for example, there are heterogeneous subcategories each with their own behaviors and strategies (Khelil 2016). Within the category of M&A, there are heterogeneous subcategories ranging from lucrative acquisitions of high-potential startups to fire-sale mergers of distressed corporate giants.

Future research could also investigate the intentions of entrepreneurs regarding post-entry growth and exit strategies. Our analysis shows some interesting associations between growth paths and subsequent exit routes, but it does not measure the intentions of entrepreneurs. Can entrepreneurs plan ahead for rapid growth? Can firms develop an exit strategy on the basis of their intended post-entry growth? Regarding the relevant time scale, can firms plan their exit routes from their first day of operations? We suspect that firms choose among the available exit routes after having observed what their post-entry growth has been, in line with theories that post-entry growth is approximately a random walk (Jovanovic 1982; Levinthal 1991; Coad et al. 2013). However, future work could more closely focus on the causal link from entrepreneur’s intentions to observed exit routes.

7 Conclusions

We analyzed a cohort of incorporated firms in Japan and find some puzzles for the standard view. In the Japanese context, not all exit routes are available to all firms: small firms do not realistically face the options of M&A or bankruptcy but essentially face a choice between survival and voluntary liquidation. Our empirical analysis indicated that sales growth in the years before exit is a significant predictor of exit routes. Non-parametric graphs and statistics, as well as multinomial logistic and complementary log-log regressions, suggest that lagged sales growth generally reduces the probability of exit by merger, voluntary liquidation, and also bankruptcy. However, the relationship is U-shaped—such that rapid growth actually increases the probability of exit. More generally, each of the three exit routes can occur all across the growth rate distribution. Large firms are more likely to exit via merger or bankruptcy, while small firms are more likely to exit via voluntary liquidation.

Notes

The literature has even invented the concept of an “involuntary exit strategy,” although we doubt that something truly strategic can also be involuntary.

Given the scope of this paper, however, we do not investigate the determinants of startup size, but take startup size as given, and focus on post-entry growth and exit routes.

To be fair, this idea has been hinted at in the previous literature, e.g. Wennberg and DeTienne (2014, p9): “the type of exit routes available and the willingness to exit may differ significantly between lifestyle entrepreneurs and growth entrepreneurs.”

Moreover, we have another advantage to use COSMOS2 that firms’ status can be traced after firms’ relocation. In contrast, firms’ relocation is often regarded as exit from a region and entry into another region in government statistics, partly because the surveys are done by prefecture.

The credit investigation company asks the managers about the numbers for total annual sales, number of employees, profits etc., although the managers do not necessarily disclose the exact amount. So, the investigators usually attempt to obtain such information by a number of means, for example, by asking whether the number is same as the previous year. This explains why the number for sales is sometimes identical to the previous year (i.e. change of zero yen from one year to the next), and why we have a likely over-representation of annual growth rates of sales of exactly zero.

Note that the earliest years are not included in the regressions because these observations are lost due to the inclusion of lagged growth as independent variable.

For discussion of advantages of a discrete-time survival model, see Wiklund et al. (2010).

Regarding the effect size: Table 3 column (2) shows that if lagged growth increases by one standard deviation, then the change in the odds of exit via voluntary liquidation (compared to the benchmark case of survival) is 0.052 x (exp(−0.359) = 0.0363.

See Haans et al. (2016) for critical issues in theorizing and testing of quadratic relationships.

There is no clear cut-off point to distinguish between small and large firms because the firm size distribution in our sample is a continuous and approximately lognormal distribution (see Figure A1 in the Appendix). Therefore, we distinguish between small and large size subsamples by referring to the median size.

This effect is only found in the specification without quadratic terms for the second lag of growth. When quadratic terms are added, the coefficient is no longer statistically significant.

One potential drawback, however, of this alternative independent variable is that growth is measured over different growth periods across firms (e.g. time from startup to exit could be 2 years for one firm, and 6 years for another), and averaging over periods of different lengths could introduce bias. This could make it problematic to compare firms whose growth unfolds over different timescales (e.g. if rapid growth is harder to sustain over longer periods). This possible measurement error should be kept in mind.

References

Ahlers, G. K., Cumming, D., Günther, C., & Schweizer, D. (2015). Signaling in equity crowdfunding. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 39, 955–980.

Almus, M. (2004). The shadow of death - an empirical analysis of the pre-exit performance of new German firms. Small Business Economics, 23, 189–201.

Arora, A., & Nandkumar, A. (2011). Cash-out or flameout! Opportunity cost and entrepreneurial strategy: theory, and evidence from the information security industry. Management Science, 57, 1844–1860.

Bartelsman, E., Scarpetta, S., & Schivardi, F. (2005). Comparative analysis of firm demographics and survival: evidence from micro-level sources in OECD countries. Industrial and Corporate Change, 14, 365–391.

Baù, M., Sieger, P., Eddleston, K. A., & Chirico, F. (2017). Fail but try again? The effects of age, gender, and multiple-owner experience on failed entrepreneurs’ reentry. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 41, 909–941.

Bernard, A. B., Massari, R., Reyes, J. D., & Taglioni, D. (2017). Exporter dynamics, firm size and growth, and partial year effects. American Economic Review, 107, 3211–3228.

Blanchard, P., Huiban, J. P., & Mathieu, C. (2014). The shadow of death model revisited with an application to French firms. Applied Economics, 46, 1883–1893.

Botham, R., & Graves, A. (2011). Regional variations in new firm job creation: the contribution of high growth startups. Local Economy, 26, 95–107.

Brännback, M., Carsrud, A. L., & Kiviluoto, N. (2014). Understanding the myth of high growth firms: the theory of the greater fool. New York, Heidelberg, Dordrecht & London: Springer Science & Business Media. Springer.

Carreira, C., & Teixeira, P. (2011). The shadow of death: analysing the pre-exit productivity of Portuguese manufacturing firms. Small Business Economics, 36, 337–351.

Cefis, E., & Marsili, O. (2005). A matter of life and death: innovation and firm survival. Industrial and Corporate Change, 14, 1167–1192.

Cefis, E., & Marsili, O. (2011). Born to flip. Exit decisions of entrepreneurial firms in high-tech and low-tech industries. Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 2, 473–498.

Cefis, E., & Marsili, O. (2012). Going, going, gone. Exit forms and the innovative capabilities of firms. Research Policy, 41, 795–807.

Coad, A. (2014). Death is not a success: reflections on business exit. International Small Business Journal, 32, 721–732.

Coad, A., Frankish, J., Roberts, R., & Storey, D. (2013). Growth paths and survival chances: an application of Gambler’s ruin theory. Journal of Business Venturing, 28, 615–632.

Coad, A., Frankish, J. S., & Storey, D. J. (2019). Too fast to live? Effects of growth on survival across the growth distribution. Journal of Small Business Management, forthcoming.

Coad, A. (2018). Firm age: a survey. Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 28, 13–43.

de Jong, J. P., & Marsili, O. (2015). Founding a business inspired by close entrepreneurial ties: does it matter for survival? Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 39, 1005–1025.

Dencker, J. C., Gruber, M., & Shah, S. K. (2009). Pre-entry knowledge, learning and the survival of new firms. Organization Science, 20, 516–537.

DeTienne, D. R., & Cardon, M. S. (2012). Impact of founder experience on exit intentions. Small Business Economics, 38, 351–374.

DeTienne, D. R., McKelvie, A., & Chandler, G. N. (2015). Making sense of entrepreneurial exit strategies: a typology and test. Journal of Business Venturing, 30, 255–272.

Diwisch, S., Voithofer, P., & Weiss, C. (2006). The ‘shadow of succession’: a non-parametric matching approach. Mimeo.

Fackler, D., Schnabel, C., & Wagner, J. (2014). Lingering illness or sudden death? Pre-exit employment developments in German establishments. Industrial and Corporate Change, 23, 1121–1140.

Gimeno, J., Folta, T. B., Cooper, A. C., & Woo, C. Y. (1997). Survival of the fittest? Entrepreneurial human capital and the persistence of underperforming firms. Administrative Science Quarterly, 42, 750–783.

Graebner, M. E., & Eisenhardt, K. M. (2004). The seller's side of the story: acquisition as courtship and governance as syndicate in entrepreneurial firms. Administrative Science Quarterly, 49, 366–403.

Griliches, Z., & Regev, H. (1995). Firm productivity in Israeli industry 1979–1988. Journal of Econometrics, 65, 175–203.

Haans, R. F., Pieters, C., & He, Z. L. (2016). Thinking about U: theorizing and testing U-and inverted U-shaped relationships in strategy research. Strategic Management Journal, 37, 1177–1195.

Harada, N. (2007). Which firms exit and why? An analysis of small firm exits in Japan. Small Business Economics, 29, 401–414.

Harhoff, D., Stahl, K., & Woywode, M. (1998). Legal form, growth and exit of west German firms—empirical results for manufacturing, construction, trade and service industries. Journal of Industrial Economics, 46, 453–488.

Headd, B. (2003). Redefining business success: distinguishing between closure and failure. Small Business Economics, 21, 51–61.

Honjo, Y. (2015). Why are entrepreneurship levels so low in Japan? Japan and the World Economy, 36, 88–101.

Honjo, Y., & Nagaoka, S. (2018). Initial public offering and financing of biotechnology start-ups: evidence from Japan. Research Policy, 47, 180–193.

Ito, T. (2011). Reform of financial supervisory and regulatory regimes: what has been achieved and what is still missing. International Economic Journal, 25, 553–569.

Jovanovic, B. (1982). Selection and the evolution of industry. Econometrica, 50, 649–670.

Kato, M., & Honjo, Y. (2015). Entrepreneurial human capital and the survival of new firms in high-and low-tech sectors. Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 25, 925–957.

Kato M, Onishi K, Honjo Y, (2017). Does patenting always help new-firm survival? Discussion paper series no. 159, School of Economics, Kwansei Gakuin University.

Khelil, N. (2016). The many faces of entrepreneurial failure: Insights from an empirical taxonomy. Journal of Business Venturing, 31, 72–94.

Kiyota, K., & Takizawa, M. (2007). The shadow of death: pre-exit performance of firms in Japan. Discussion paper series no.204, Hitotsubashi University.

Klotz, A. C., Hmieleski, K. M., Bradley, B. H., & Busenitz, L. W. (2014). New venture teams: a review of the literature and roadmap for future research. Journal of Management, 40, 226–255.

Koski, H., & Pajarinen, M. (2015). Subsidies, the shadow of death and labor productivity. Journal of Industry, Competition and Trade, 15, 189–204.

Kubo, K., & Saito, T. (2012). The effect of mergers on employment and wages: evidence from Japan. Journal of the Japanese and International Economies, 26, 263–284.

Lansing, P., & Wechselblatt, M. (1983). Doing business in Japan: the importance of the unwritten law. The International Lawyer, 17, 647–660.

Lee, S. H., Peng, M. W., & Barney, J. B. (2007). Bankruptcy law and entrepreneurship development: a real options perspective. Academy of Management Review, 32, 257–272.

Lee, S. H., Yamakawa, Y., Peng, M. W., & Barney, J. B. (2011). How do bankruptcy laws affect entrepreneurship development around the world? Journal of Business Venturing, 26, 505–520.

Le Mens, G., Hannan, M. T., & Polos, L. (2011). Founding conditions, learning, and organizational life chances: age dependence revisited. Administrative Science Quarterly, 56, 95–126.

Levinthal, D. A. (1991). Random walks and organizational mortality. Administrative Science Quarterly, 36, 397–420.

Marlow, S., Mason, C., & Mullen, H. (2011). Advancing understanding of business closure and failure: a critical re-evaluation of the business exit decision. Paper presented at the Institute for Small Business and Entrepreneurship Conference 2011, Sheffield, 9–10 November, 2011.

Mehrotra, V., van Schaik, D., Spronk, J., & Steenbeek, O. W. (2008). Impact of Japanese mergers on shareholder wealth: an analysis of bidder and target companies. Erasmus Research Institute of Management (ERIM) Report Series, ERS-2008-032-F&A.

Miller, C. C., Washburn, N. T., & Glick, W. H. (2013). The myth of firm performance. Organization Science, 24, 948–964.

Parker, S. C. (2018). The economics of entrepreneurship. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Pe'er, A., Vertinsky, I., & Keil, T. (2016). Growth and survival: the moderating effects of local agglomeration and local market structure. Strategic Management Journal, 37, 541–564.

Peng, M. W., Yamakawa, Y., & Lee, S. H. (2010). Bankruptcy laws and entrepreneur–friendliness. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 34, 517–530.

Ponikvar, N., Kejžar, K. Z., & Peljhan, D. (2018). The role of financial constraints for alternative firm exit modes. Small Business Economics, 51, 85–103.

Porter, M. E., & Sakakibara, M. (2004). Competition in Japan. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 18(1), 27–50.

Ries, E. (2011). The lean startup: how today’s entrepreneurs use continuous innovation to create radically successful businesses. Crown Books.

Schary, M. A. (1991). The probability of exit. RAND Journal of Economics, 22, 339–353.

Sedlacek, P., & Sterk, V. (2017). The growth potential of startups over the business cycle. American Economic Review, 107, 3182–3210.

Shepherd, D., & Wiklund, J. (2009). Are we comparing apples with apples or apples with oranges? Appropriateness of knowledge accumulation across growth studies. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33, 105–123.

Stinchcombe, A. (1965). Social structure and organizations. In J. March (Ed.), Handbook of organizations (pp. 142–193). Chicago: Rand McNally.

Storey, D. J. (2011). Optimism and chance: The elephants in the entrepreneurship room. International Small Business Journal, 29, 303–321.

Strese, S., Gebhard, P., Feierabend, D., & Brettel, M. (2018). Entrepreneurs' perceived exit performance: conceptualization and scale development. Journal of Business Venturing, 33, 351–370.

Tornqvist L., Vartia P., Vartia Y.O. (1985). How Should Relative Changes Be Measured? American Statistician 39, 43–46.

Villalonga, B., & McGahan, A. M. (2005). The choice among acquisitions, alliances, and divestitures. Strategic Management Journal, 26, 1183–1208.

Wennberg, K., & Anderson, B. S. (2019). Editorial: enhancing quantitative exploratory entrepreneurship research. Journal of Business Venturing, forthcoming.

Wennberg, K., & DeTienne, D. R. (2014). What do we really mean when we talk about ‘exit’? A critical review of research on entrepreneurial exit. International Small Business Journal, 32, 4–16.

Wennberg, K., Wiklund, J., Detienne, D. R., & Cardon, M. S. (2010). Reconceptualizing entrepreneurial exit: divergent exit routes and their drivers. Journal of Business Venturing, 25, 361–375.

Wiklund, J., Baker, T., & Shepherd, D. (2010). The age-effect of financial indicators as buffers against the liability of newness. Journal of Business Venturing, 25, 423–437.

Yamakawa, Y., & Cardon, M. S. (2017). How prior investments of time, money, and employee hires influence time to exit a distressed venture, and the extent to which contingency planning helps. Journal of Business Venturing, 32, 1–17.

Zhou, H., & van der Zwan, P. (2019). Is there a risk of growing fast? The relationship between organic employment growth and firm exit. Industrial and Corporate Change, forthcoming.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Giulio Bottazzi, Elena Cefis, Masaru Karube, Francesco Lamperti, Sadao Nagaoka, Alessandro Nuvolari, and seminar participants at the Sant’Anna School of Advanced Studies (Pisa, Italy), the Innovation Economics Workshop, Hitotsubashi University (Tokyo, Japan), and University of Bergamo (Bergamo, Italy) for many helpful comments and discussions. Any remaining errors are ours alone.

Funding

Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) (No. 26285060) and (C) (No.18K01639), Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Coad, A., Kato, M. Growth paths and routes to exit: 'shadow of death' effects for new firms in Japan. Small Bus Econ 57, 1145–1173 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-020-00341-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-020-00341-z