Abstract

An influential stream of research notes the importance of the culture and attractiveness of a place in creating a supportive environment where competition, creativity, and entrepreneurship can flourish. However, what specific kind of culture is attractive and actually needed remains both unknown and controversial. While several scholars have stressed the general importance of diversity and a vibrant cultural life, this paper attempts to introduce a new and complementary perspective that puts the role of subcultural scenes at the center of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Social and economic innovations have always been pushed forward by the pioneering subgroup of “creative destructors” that share values and beliefs that are different from the establishment. Thus, we believe that, instead of culture as a whole, it might be more promising to take a closer look at subcultures and their influence on urban creative and entrepreneurial scenes. We test this hypothesis by deploying exploratory factor analysis to compare the impact of different measures of subcultural amenities compared with the traditional measures used to reflect “mainstream” culture on start-up rates in the 69 largest cities in Germany. Our findings confirm the main hypothesis posited in this paper that the co-presence of subcultural amenities is positively associated with entrepreneurship. By contrast, mainstream culture has no significant impact on local start-up rates. These findings make an important contribution to the recent controversy within the regional study literature and provide insights and guidance for thought leaders in policy and urban planning.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Regional economic development across the globe has turned to entrepreneurship as an engine for enhancing growth. Over the past decades, this has led to extensive investments by policy makers to create an environment and local context conducive to entrepreneurship and innovation. In searching for such a beneficial environment, both scholars and policy makers have shifted more and more away from “hard” physical assets towards “softer” locational factors, such as creative milieus, culture, and the role of amenities (Florida 2002; Hopp and Stephan 2012; Huggins and Thompson 2014; Moretti 2004). The basic hypothesis here is that place-based entrepreneurship is the product of the spatial concentration of a skilled “creative class” of talented people that today are highly mobile and feel especially drawn to culturally diverse and tolerant urban spaces that offer amenities and inspiring creative scenes (Fritsch and Wyrwich 2012; Florida and Mellander 2015; Lee et al. 2010). Yet, our knowledge about places’ amenities and entrepreneurship culture is still limited. While we know they matter, what exact types matter, how they look and feel, and how they should be measured remain both controversial and unknown. While an influential stream of literature has stressed the general importance of social capital and diversity for entrepreneurship culture (Florida and Gates 2003; De Carolis and Saparito 2006; Audretsch et al. 2010), others have studied the role of interesting cultural scenes and their corresponding facilities (like art galleries, bars, and opera houses) for attracting smart and entrepreneurial talents—with mixed evidence (Bauer et al. 2015; Falck et al. 2011; Evans 2009; Thiel 2015).

However, a more nuanced view has recently been posited by Peck (2005), Hollands (2008), and Pratt (2011), who suggest that smart places are not necessarily highly entrepreneurial places. Rather, they provide a compelling argument that what fuels place-based entrepreneurship is less about human capital or the creative class in general and more about the co-presence of a “creative underclass” of entrepreneurs that can transform a place into a start-up hotspot. Thus, the cultural amenities attractive to and serving as a beacon for this creative underclass of entrepreneurs may, in fact, not be the same as those for mainstream human capital and the creative class (Peck 2005; Pratt 2011; Storper and Scott 2009).

Despite this controversy in both the scholarly literature as well as among thought leaders in public policy and business, the particular type of cultural amenities that actually play an important role and serve as a beacon attracting the creative underclass has yet to be studied. This void in the entrepreneurship literature is unfortunate, because it leaves a daunting gap in the ability of both scholars and the policy community to understand what exactly attracts the creative class and underclass to a place. The purpose of this paper is to fill this gap in the literature by explicitly comparing the influence of cultural amenities versus subcultural amenities on local start-up activity.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 draws on the extant literature to develop the main hypotheses suggesting that a vibrant cultural life is conducive for attracting and retaining creative milieus, but that the particular kind of culture that is beneficial is considerably more nuanced. We develop the hypothesis that entrepreneurship activity needs some kind of “spiritus loci” for open-mindedness and experimentalism and that this cultural spirit is likely to be found in places characterized by a vibrant subcultural scene rather than mainstream culture, which, by contrast, is more likely to be conducive to formal human capital and the social establishment. Our study builds onto the recent entrepreneurship literature focusing on the impact of place-based amenities attracting creative workers on entrepreneurial activity. By testing the impact of subcultures on start-up activity, we try to shed light on a key link that has been largely overlooked and remains missing in the extant literature in entrepreneurship and regional development of exactly how culture shapes entrepreneurial networks and spillovers. This paper makes a key contribution by being the first in the literature to introduce a model of measuring subcultures and comparing their influence against measures of mainstream culture. Our research makes an important contribution to the entrepreneurship literature by identifying those factors conducive to creative places, in contrast to those factors conducive to smart places. A secondary contribution of the paper to the entrepreneurship literature is that it adds to our knowledge about entrepreneurial milieus and their preferences. Section 3 introduces the data set and methodology used to undertake our empirical analysis. Section 4 reports the results of our analysis. The fifth section discusses our findings in the backdrop of previous results in the entrepreneurship literature and the limitations of the analysis. In the last section, we provide a conclusion that highlights the main findings and provides an outlook for future research and policy implications.

2 Literature and theoretical background

An important set of studies in the regional study literature has provided a compelling link between entrepreneurship and the competitiveness of regions as being driven by the ability to exploit new knowledge via innovation and creative entrepreneurship (Acs and Varga 2002; Audretsch and Feldman 2004;. These studies have triggered an explosion of research attempting to quantify and identify the specific sources that promote high innovation and regional entrepreneurship. One major focus centers on the spatial concentration of knowledge and human creativity as measured by better educated and highly talented people (Audretsch and Feldman 2004; Berry and Glaeser 2005; Cushing et al. 2002; Florida 2002; Jacobs 1970; Moretti 2004; Rauch et al. 2013; Shapiro 2006). Talented people, of course, are not evenly distributed across geographic space. Research has identified numerous necessary conditions, ranging from local industrial clusters (Acs et al. 2013; Lehmann and Menter 2016; Porter 2000), top universities, the supply on educational attainment (Kuratko 2005; Lehmann 2015; Leydesdorff and Etzkowitz 1996), income levels (Acs et al. 2008; Glaeser et al. 2009; Wennekers et al. 2005), thick labor markets and established firms, or local accessibility (Audretsch and Belitski 2013; Caragliu et al. 2011; Glaeser et al. 2008b; Knudsen et al. 2008; Saxenian 1996), to play an important role for a high share of regional human capital. In addition to the, primarily physical, factors, which are commonly referred to as hard factors, a recent strand in research has stressed the significant role of softer, more lifestyle-oriented factors, such as the attractiveness of a place and other social characteristics, which is commonly referred to in the literature as “amenities” (Bauer et al. 2015; Falck et al. 2011; Lehmann and Seitz 2017; Rappaport 2008; Rosenthal and Strange 2008; Zheng 2016). The basic argument is that in open and post-industrial economies, talented people are highly mobile and make their locational choices principally in response to quality of life rather than solely on wages (e.g., Florida 2002; Inglehart et al. 2008; Landry 2008; Storper and Scott 2009).

2.1 Amenities, talents, and entrepreneurship culture

However, the question of which specific amenities actually make a place attractive to highly talented people and consequently entrepreneurs has recently become the focus of a widespread discussion in the literature (Bauer et al. 2015; Hirschle and Kleiner 2014; McGranahan et al. 2010; Storper and Scott 2009; Zheng 2016). Over the last several years, a number of different types of amenities have been analyzed—yet without consistent findings. The literature here can be broadly divided into two basic categories. The first category is based on econometric analysis testing the impact of the several key forces that have been posited in the literature to influence the clustering of high human capital (e.g., Berry and Glaeser 2005; Glaeser et al. 2001; Glaeser et al. 2010; Lloyd and Clark 2001). The extant literature is vast and suggests that a widely ranging set of locational amenities is particularly influential, ranging from exogenously given factors, such as weather conditions or location with close geographic proximity to a coast line or rivers, to a number of endogenous factors, such as quality of transport infrastructure, entertainment amenities, housing quality, and security considerations (e.g., Bayer et al. 2009; Berry and Glaeser 2005; Glaeser and Gottlieb 2006; Glaeser et al. 2001; Glaeser et al. 2010). In addition, there seem to be possible interactions and subsidization effects between the different types of amenities (Storper and Scott 2009). For instance, Berry and Glaeser (2005) suggest that warm, dry winters, especially the average temperature in January, matters most in explaining high levels of local human capital, but other amenities are also important and might compensate for possible shortcomings in other amenities. Thus, cold places can offset the role of a warm climate by providing safe neighborhoods, reasonable housing prices, and good school and education facilities (Berry and Glaeser 2005; Glaeser and Gottlieb 2006; Storper and Scott 2009). Nevertheless, one key insight emerging from of this line of research is that specific amenities associated with consumption opportunities, such as entertainment, restaurants, and other cultural facilities, have grown in importance across all type of places, even for those places that were originally organized around industrial production (Clark et al. 2002; Falck et al. 2011; Glaeser and Gottlieb 2006; Glaeser et al. 2001; McGranahan et al. 2010; Möller and Tubadji 2009; Rappaport 2008).

Similar evidence can be found in the urban sociology literature. For instance, Evans (2009) and Clark et al. (2002) have reported a general decline in the explanatory power of conventional variables affecting places’ growth while local attractions, such as orchestras, parks, museums, art galleries, or architecture, have raised in relevance. They argue that in post-industrial, information economies, there has been generally a great rise of leisure pursuit compared with work (Clark et al. 2002; Inglehart et al. 2008; Rappaport 2008; Zheng 2016). Leisure activities need time, money, and certain amenities to satisfy those desires. Thus, places transforming into “entertainment machines” tend to focus on attracting and retaining a modern class of affluent and highly talented people (Bauer et al. 2015; Lloyd and Clark 2001; Rappaport 2008).

Extending this first strand of the literature, the second major strand refines some of the abovementioned arguments and provides a much broader perspective. Instead of focusing on individual attractions, research here has stressed the general importance of local culture for attracting human capital (Beugelsdijk 2010; Cushing et al. 2002; Davidsson 1995; Florida 2014; Hirschle and Kleiner 2014). In contrast to the first strand of research, those studies do not have an exclusive focus on human capital, in terms of classical human capital theory, i.e., well-educated and skilled workers, but rather analyze the population movements of a specific, highly disaggregated subgroups of human capital that is associated with high creative outcomes, innovation, and entrepreneurship (Florida 2003; Lehmann and Seitz 2017; Peck 2005; Pratt 2011; Scott 2006; Zheng 2016). Most prominent here is Florida’s (2003) work on the theory of the creative class. Pioneering work is also associated with Park et al. (1925/1984) or Jacob’s (Jacobs 1970) seminal writings about the creative cities and could even date back to Marshall’s (1920) initial ideas of an “industrial atmosphere.” All approaches here suggest that a concentration of high human capital in general, but more specifically the co-presence of a creative milieu, makes places highly innovative. These milieus consist of highly talented people that are not necessarily formally well educated but work primarily in a creative, problem-solving manner (Clifton and Cooke 2009; Comunian 2010; Florida 2002; Landry 2008). These creative talents, which Florida calls “creative class,” search for other types of amenities compared with conventional human capital. Due to their work ethos, they choose place-specific cultural mindset over conventional attractions, such as museums, cinema, and housing conditions. They search for places that welcome divergent thinking and support experimentalism and tolerance for diversity (Cushing et al. 2002; Florida and Gates 2003; Hackler and Mayer 2008; Qian 2013). Therefore, providing such a cultural climate that attracts those creative talents is the key ingredient to promoting place-specific innovation and entrepreneurship activity (Boschma and Fritsch 2009; Florida 2005, 2014).

Although these various approaches often have served as blue print for development agendas across the globe, their evidence is mixed. Criticism is vast, spanning different aspects as well as both conceptual and methodological shortcomings (Donegan et al. 2008; McGranahan and Wojan 2007; Storper and Scott 2009; Zheng 2016).

The first concerns endogeneity issues. Thus, whether tolerant places are rather the cause for the clustering of highly talented people or the consequence is ambiguous. Indeed, ample evidence from various disciplines of social science suggests that the level of which communities grant individuality and show tolerance for diversity is linked to both economic development, wages, and educational level (Inglehart et al. 2008). In a similar vein, Glaeser et al. (2008a) reveal it is not primarily the cultural setting that drives regional growth, but rather the stock of human capital, industrial density, and the presence of research institutions and universities that stimulates innovation and entrepreneurship. Glaeser et al. (2010) concludes that cities with a large share of high-skilled and high-earning people also tend to have a higher willingness to pay for cultural amenities, which drives local cultural development. Möller and Tubadji (2009) have tested Florida’s concept of the creative class using panel data for 323West German regions. According to their findings, the creative class is attracted by favorable economic conditions such as employment growth and wages rather than culture. Falck et al. (2011) and Möller and Tubadji (2009) propose a strategy that partly overcomes endogeneity issues. By going back in history, the authors claim that the contemporary regional endowment of human capital is the result of cultural heritage. Using German opera houses from the baroque era to measure the cultural legacy of places, their findings reveal that culture affects the concentration of human capital employees, and these employees promote local knowledge spillovers and shift a location to a higher growth path. However, Bauer et al. (2015) demonstrate that this strategy is prone to misleading results since cultural legacy and historical cultural goods are highly correlated with other historical events.

Another weakness in the literature concerns the identification of the preferences that are held to motivate the locational choices of highly talented people (Bayer et al. 2009; Clark; Hansen and Niedomysl 2009; Pratt 2008; Storper and Scott 2009). All of them select observable locational features, e.g., diversity, density, temperature, prices, tolerance, or other cultural amenities, and then assume that these features must match with the preferences of those highly talented and skilled people that provide the source of entrepreneurship. For instance, Pratt (2011) criticizes Florida for deriving his relevant preferences simply on the basis of interviews and suggestive correlations. Storper and Scott (2009) question why tolerance, in particular, or Florida’s suggested operational expression, diversity, and open-mindedness acts as a compelling amenity serving as a beacon for those creative talents, when the very same talents “[…] who are claimed to be so motivated by tolerance and diversity […]” (p. 155) today typically share relatively homogenous lifestyles, search for each other and the same neighborhoods. Other studies have found a non-significant relationship among different measures of diversity and high growth, innovation, and entrepreneurship outcomes (Basu and Altinay 2002; Lee 2014). Thus, the most diverse places seem not necessarily to be also the most creative ones. The great melting pots around the world provide anecdotal evidence. Cities such as Frankfurt and Singapore are known for their rich and diverse culture, but not as being centers of creativity. Similarly, some recent studies even warn against possible negative effects of tolerance and diversity, while emphasizing the importance of social cohesion, safe neighborhoods, and trust (Berggren and Jordahl 2006; Hauser et al. 2007; Portes and Vickstrom 2015; Qian 2013; Smallbone et al. 2010).

Empirical approaches used in recent studies that aim to overcome previous research traps by integrating a variety of different amenities in their analysis, have also been criticized for missing some important aspects. For instance, none of these approaches provide an analytical framework that provides sufficient justification of their selection choices and why these specific amenities should play a role. Accordingly, Storper and Scott (2009) and Zheng (2016) have summarized that the different amenities seem to be randomly selected rather than theoretically developed. Others also criticize the lack of research that deploys structural techniques, such as exploratory factor analysis or structural equation models, to identify possible interactions and structural patterns among the different types of amenities (Audretsch and Belitski 2013; Bauer et al. 2015; Clark; McGranahan et al. 2010; Zheng 2016).

Closely linked to these questions of relevant preferences is another major criticism, which is generally concerned with endogeneity issues (Bauer et al. 2015; Glaeser et al. 2010; Peck 2005; Rappaport 2008). While most previous studies have only explored the relationship between types of amenities and a high local concentration of highly skilled and creative talents, research that explicitly measures the effect of amenities on entrepreneurship activity is scant. However, there is no serious doubt that places with a high concentration of talented people also tend to exhibit high levels of human capital, R&D, high technology, and innovations, but whether, in fact, these “smart places” are actually characterized by a high degree of entrepreneurial activity is less evident. Several recent studies provide compelling evidence that these phenomena may not necessarily be geographically co-located (Caragliu et al. 2011; Hollands 2008; Shapiro 2006). For example, Lehmann et al. (2017) found that innovative places, as measured by hard patentable output, are characterized by a rich industrial and R&D climate. By contrast, start-up cities are more likely to feature creative industries and cultural diversity. Hence, it seems to be more a matter of who the entrepreneurs actually are and what preferences they share. In a similar vein, Pratt (2011) and Morgan and Ren (2012) suggest that entrepreneurs constitute a creative underclass which demands an inspirational atmosphere that goes far beyond social diversity and open-mindedness. This idea is also reflected by Peck (2005), who argues that entrepreneurs are more likely to be an exclusive, avant-garde, and of out-of-box thinkers with preferences that distinguish them from well-educated and creative people. Empirical evidence that preferences systematically differ across distinct subpopulations of talented people is provided by Clark (2004). Analyzing 3111 US counties for 20 different amenities, Clark’s findings indicate that middle-aged highly educated workers appreciate natural and outdoor amenities, whereas young talents are more drawn to constructed “cultural” amenities, such as fine arts, bars, and museum. Engineers and high tech workers live in places with both more outdoor spaces and cultural amenities. Similarly, Florida (2014) observed a migration trend where start-up scenes move from suburban locations, like Silicon Valley or the Boston’s outskirts along the Route 128, towards more denser and walkable outlets with a vibrant street culture, like downtown San Francisco or Lower Manhattan. In his study of creative clusters in London, Singapore, and Vancouver, Hutton (2006) has also found support that many creative workers feel particularly drawn to built environments rather than natural environments. Creative people prefer locations in the city center and former industrial buildings, because they offer a stylish lifestyle and historical identity.

However, which amenities are associated with the lifestyle considerations of creative entrepreneurs, and whether these might explain high local entrepreneurship activity, has not yet been directly analyzed. Several studies claim that it would be of particular interest to see how conventional human capital, for instance highly educated employees, and creative entrepreneurs differ in their preferences towards cultural amenities and what makes places attractive to those type of creative underclass (Heebels and van Aalst 2010; Kloosterman 2014; Morgan and Ren 2012). This study aims to contribute to the extant literature by developing an expanded approach that revolves around the impact of subcultures.

2.2 Subcultures and entrepreneurship

Studies on subcultures and their impact on societies have enlivened research in the twentieth century and appear to become even more relevant in the beginning of the twenty-first century (Dhoest et al. 2015). Subcultures are defined as distinctive groups of society that are bound by alternative perceptions, values, and beliefs towards life as the establishment or socio-cultural mainstream (Hebdige 1995; Schouten and McAlexander 1995). Ever since the initial wave of research, subcultures have been seen as cradles for avant-garde lifestyles that subsequently flow into mainstream culture, thus changing dominant values (Dhoest et al. 2015; Hebdige 1995; Schouten and McAlexander 1995). For example, the beatniks of the 1950s, the hippies of the 1960s, the environmental movement of late 1970s, punk or club scene of the 1980s, the 1990s grunge, or contemporary hip hop and indie rock of the 2000s constitute prominent examples of subcultures that have influenced the “Zeitgeist,” or paradigm of the time.

Both entrepreneurship research and innovation policy research have increasingly considered the impact of subcultures over past two decades (Kloosterman 2014; Morgan and Ren 2012). It is argued that, like for all other dimensions of social life, even the entrepreneurial spirit has been influenced by a small and pioneering avant-garde subculture consisting of freaks and geeks. For instance, it was a small scene of nerdy masterminds that created Silicon Valley’s legacy as a start-up El Dorado in a garage. Starting from there, it was the legends and images crafted by visionary entrepreneurs such as Steve Jobs, Bill Gates, or Larry Ellison that diffused the hero-like perception of entrepreneurs across the USA and throughout the rest of the world. These visionary entrepreneurs served as role models for an entire generation of founders during the age of the new economy and still influence the contemporary entrepreneurial scene today.

Even though Silicon Valley is still the hub of the start-up world, we observe vibrant start-up scenes across the globe, such as in Austin, Nashville, Tel Aviv, Berlin, Moscow, Copenhagen, or Leipzig. These cities are not exclusively built on a high share of human capital or industrial production, but are globally recognized for their vibrant street and subcultural scenes.

Williams (2007) notes that the legacy of all subcultures is in protest and tolerance culture. Similarly, Fischer (1975) has studied the formation of subcultural scenes in urban areas. His findings report that subcultures constitute themselves in a culture of “being different” and having “unconventional values”—all vivid in eccentric dress styles, bars and music clubs, and consumption patterns (Hirschle and Kleiner 2014). Thus, the co-presence of a vibrant subcultural scene might encourage people to think differently and is conducive to experimentalism and creativity, inspiring entrepreneurs (Dhoest et al. 2015; Evans 1997; Hall and Jefferson 1993; Hebdige 1995). This may suggest that subcultural scenes are a better predictor for place-based entrepreneurship than are the previously tested “conventional” traits of popular cultural amenities. Thus, creative entrepreneurs might choose music clubs over operas, independent music over philharmonics, and prefer street art and culture over the fine arts and large-scale amenities, like Madame Tussaude’s and zoos, as inspirational sources and places of exchange to meet with friends (Kloosterman 2005, 2014).

However, until now, there has been no systematical research exploring the relationship between subcultures, regional development, and entrepreneurial activity. This paper aims to fill this research gap by identifying the impact of different cultural amenities on local entrepreneurship activity. In adhering to the findings of the extant literature, this paper posits that talented and entrepreneurial people are especially attached to rich cultural environments, but that the preferences for each group systematically differ. Thus, while much of human capital, in the sense of skilled and trained people, is attracted to mainstream and popular culture, such as museums, theater, or cinemas (Florida and Gates 2003; Glaeser et al. 2008a; Glaeser et al. 2010; Landry 2008), entrepreneurial people may search for other “subcultural” types of amenities.

These hypotheses have neither been posited nor subjected to empirical scrutiny in the entrepreneurship literature. In the next section, we test our hypothesis by examining the impact of different measures of cultural amenities reflecting mainstream versus alternative culture, on local start-up rates. Measuring subcultures presents a challenge, since there is no extant literature upon which to draw. We utilize exploratory factor analysis to compare the effect of different measures of subcultural amenities against measures which have traditionally been used to reflect “mainstream” culture on start-up rates. Thus, we are able to provide the first analysis of entrepreneurship with empirical strategy for measuring subcultures and identifying their different impacts on entrepreneurship.

3 Empirical analysis

3.1 Sample and data

This section submits the hypothesis that entrepreneurs are attracted to locations characterized by a vibrant subcultural life rather than mainstream culture to empirical scrutiny. These entrepreneurs self-select themselves to “hip” places that fulfill their desires for alternative sense-making, underground lifestyles, and open-mindedness. These places then emerge as entrepreneurial hotspots with higher start-up rates. Since there is no previous work to build on, capturing whether cities are more mainstream or subcultural presents a challenge. The distinction between cultural amenities that might be targeting more mainstream audiences rather than niches and subcultures is not iron glad (Kloosterman 2014). Hence, we propose a multi-dimensional approach spanning several variables from which we believe incorporate either mainstream or niche-oriented cultural patterns. In order to provide a systematical framework, we utilize exploratory factor analysis to even statistical confine measures of mainstream and subculture and test their impact on local entrepreneurship activity.

We test our hypothesis by analyzing the 69 largest urban districts (independent cities) in Germany. Given the proximity and density of social and physical capital, amenities, and necessary infrastructure conditions, scholars have found that large cities tend to be the most relevant socioeconomic and institutional unit of analysis for entrepreneurship-driven growth (Acs et al. 2013; Begg 1999; Glaeser et al. 2010; Jacobs 1970; Kloosterman 2005; Landry 2008; Meijers 2008; Moretti 2004; Pflüger and Südekum 2008; Ullman 1954). We utilize a full and comprehensive dataset of all large cities in Germany provided by the Census of 2011. Ever since the international statistical conference of 1887, large cities are defined as agglomerations with more than 100,000 inhabitants. For our purposes, we select all large German cities, of which there are 69 (for an overview, see Table 1).

We hand-collect data from several public data sources and commercial reports to construct the variables. Table 2 gives an overview and summarizes all deployed variables and their corresponding sources.

3.2 Dependent variables

Entrepreneurship is a creative process of innovation encompassing high risks and propensity for failure. Thus, entrepreneurial initiatives and actions need a cultural environment, which is, at least to a certain degree, tolerant towards failure and experimentation while supporting curiosity and creative problem-solving (Kerr et al. 2014). We attempt to measure the local culture for entrepreneurship by drawing on local start-up rates. A vast body of studies within the entrepreneurship literature have used the number of new business registrations in general, or start-up rates related to certain sectors in particular, as a proxy for local creativity and entrepreneurship outcomes. In line with recent studies, we choose new firm births in the ICT sector as a measure for local entrepreneurship culture. In comparison with high-tech and R&D-driven entrepreneurship, the ICT sector is characterized by relatively low initial investments (e.g., lab equipment, instruments, and material) and low barriers for market entry. Hence, the only things that are typically needed are a good idea and expertise in coding and programming. Thus, we believe accounting for start-up rates related to the ICT sector captures the type of basic cultural spirit needed to encourage entrepreneurial creativity. We use the number of start-ups listed in 2015 for each city by Gründerszene.de. The online platform Gründerszene.de is the leading German online news magazine for entrepreneurs, start-ups, and investors providing information about new opportunities and developments, along with daily news for the digital economy. To measure local start-up intensity, we construct a location quotient measuring the geographic concentration of start-up activity.

3.3 Explanatory variables

Measuring culture has always been a difficult task in empirical research. Over the past decades, research has tried to measure culture using different operationalization strategies, including value-based survey data (Beugelsdijk 2010; Inglehart 2004), population data and ethnic diversity (Florida and Gates 2003; Lee 2014; Smallbone et al. 2010), and the geographical distribution of personality traits or religious affiliations (Adamczyk and Pitt 2009; Obschonka et al. 2013; Obschonka et al. 2015). Within the entrepreneurship literature, capturing the cultural vibrancy via local cultural amenities has become quite common in recent times (Albouy 2016; Landry 2008; Mellander et al. 2011; Zheng 2016). It is assumed that location-specific characteristics reflect the consumption preferences of individuals (Glaeser and Gottlieb 2006; Rappaport 2008; Roback 1982). Moreover, those locations that successfully attract talent are able to meet the preferences for overall quality of life and cultural attainment (Clark et al. 2002). Thus, a rich supply of cultural scenes and amenities is not only supposed to be an indicator for a large local stock of talent, but also reflects a certain type of local culture. Previous studies have tried to measure local culture via various dimensions of cultural amenities, e.g., artistic scenes, museums, theaters, bars, cafes, and art galleries and cinemas (Bauer et al. 2015; Clark; Clark et al. 2002; Falck et al. 2011; Kloosterman 2014; Rappaport 2008). We also follow this tradition. In order to reduce possible selection bias, we draw on several variables which we believe best reflects the conventional or traditional mainstream culture. Considerable empirical work has assumed that theaters and museums not only reflect the unique cultural identity and vibrancy of a particular city, but also are important features for attracting talent and spurring urban growth (Bauer et al. 2015; Breznitz and Noonan 2014; Clark; Falck et al. 2011; Kloosterman 2014; Polèse 2012). Therefore, we use both the number of museums and the number of local theaters as measures of mainstream cultural vibrancy. However, several studies note that museums and theaters are generally more associated with the fine and high arts (Lee et al. 2010). Within this line, several studies suggest that the local supply of cultural amenities, such as museums and theaters, is more likely to be the consequence of, than the cause for, urban growth (Storper and Scott 2009). Hence, arts and culture tend to develop after cities attain a higher standard of living that enables purchasing power for consuming cultural amenities (Bauer et al. 2015; Falck et al. 2011; Glaeser and Gottlieb 2006; Glaeser et al. 2001). Within the same context, other studies provide a compelling argument that the distribution of high arts and culture is historically path-dependent and therefore more likely to be exogenous to the variations of high human capital (Bauer et al. 2015; Falck et al. 2011). In order to control for possible biases, we thus expand our analysis by including the number of cinemas as an additional factor for measuring mainstream culture. Several studies before have drawn on the number of movie theaters for measuring the attractiveness of a place (Clark et al. 2002; Lloyd and Clark 2001). We follow this approach and assume that since museums and theaters might reflect more of a high and niche cultural amenity, they might be more likely to be associated highly educated people. By contrast, movies and cinema might be more likely to reflect of mainstream culture, which might be less sensitive towards incomes or historical trajectories.

No previous research has attempted to measure local subcultural vibrancy; thus, in accordance with the procedure used above to measure the cultural mainstream, we follow a multi-dimensional operationalization strategy for measuring subcultural attainment. Subcultures have always been tightly linked to art and music scenes (Bader and Scharenberg 2010; Hall and Jefferson 1993; Hebdige 1995). We select population data for all self-employed artists and freelance authors and publicists that are locally registered at the German federal health insurance program for artists, the Künstlersozialkasse (KSK). The KSK is part of the statutory social security insurance. Since 2007, all self-employed artists and publicists are required to register with the KSK database. Measuring local cultural vibrancy through employment data in creative industries is not new and has been done in numerous studies. For example, Florida’s (2004) renowned work about the “rise of the creative class” has triggered numerous studies using population data of artists to measure the local spirit of particular locations. However, contrary to those previous approaches, we measure self-employed artists. By taking into account whether they are self-employed or not, we attempt to reduce potential interrelations with variables that might reflect the cultural mainstream rather than subcultures, e.g., number of theaters, newspapers, etc.

Nevertheless, there still might be a statistical overlap between the number of self-employed artists and freelance publicists. Therefore, we include a measure of the local concentration of independent record labels. Independent labels compensate for market failures since they publish music for small and avant-garde niche markets that are commercially uninteresting for major labels. Usually, when they have proved their potential for the big mainstream audience, music bands switch to larger labels that have the financial power to boost their careers. Thus, the presence of independent music labels may be a suitable measure of avant-garde and vibrant subcultural life.

Veganism has recently emerged as a hot trend among young urban hipsters across the globe (Cherry 2006). Contrary to the vegetarian diet, the vegan philosophy rejects all kinds of animal products for nutrition, and sometimes even clothing. It is much more radical and extreme than the vegetarian movement, which had once also started as a subcultural, eco-conscious movement, but now is indubitably mainstream. To test whether veganism affects start-up activity, we use a measure of the local number of vegan restaurants listed by PETA (People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals), the largest and most globally renowned association for protecting animal rights. Finally, we measure the extent of alternative medicine treatments as a new subcultural trend (Badley and Canizares 2016). Since the 1980s, health care, beauty, and wellness services have enjoyed a great reception in some urban areas, resulting in highly profitable markets. Similarly, alternate methods of treatment, such as ancient Chinese medicine, acupuncture, or “au natural” treatments, are enjoying a rise in popularity (Badley and Canizares 2016; Barnes et al. 2004; Tindle et al. 2005). However, in comparison with mainstream medical practices, medicine and alternate methods of treatment remain a prominent priority health-conscious subgroups. Thus, drawing on data of the number of practices offering naturopathy seems to be a reasonable way to measure the presence of alternative milieus.

3.4 Control variables

There are other important factors influencing entrepreneurial activity in addition to culture. Examples include the role of cluster structures (Lehmann and Menter 2016; Porter 1998; Zhang 2003), human capital and educational attainment (Kuratko 2005; Lee et al. 2010), and venture and social capital (Bertoni et al. 2011; Beugelsdijk and Van Schaik 2005; Obschonka et al. 2015; Samila and Sorenson 2011). Thus, we control for several common variables that have been found to consistently influence entrepreneurial activity. In his seminal work about the creative class, Florida (2004) argues that entrepreneurship and culture flourish in open-minded, social diverse, and tolerant local networks that spur creativity and knowledge. These networks usually occur in places with a high share of creative people (Florida 1995). Correspondingly, we use occupational data from employees working in creative industries, such as media, publication, and design to control for the influence of the creative class on start-up rates. Further, we consider urban density and levels of social diversity as possible influences on entrepreneurial activity (Knudsen et al. 2008; Rappaport 2008). A vast stream of research on social capital emphasizes the crucial role played by heterogeneous, weak, and open social ties for regional entrepreneurship (Hauser et al. 2007; Letki 2008; Portes and Vickstrom 2015; Westlund and Adam 2010). In accordance with previous studies, we use data about immigrants as a measure of social diversity in cities (Hackler and Mayer 2008; Qian 2013).

Research also has identified the importance of knowledge and human capital for entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurs search for both “thick” labor markets with highly qualified workers and, on the demand side, customers with high incomes (Isenberg 2011; Mack and Mayer 2015; Möller and Tubadji 2009). Thus, in order to control for the effect of human capital, we use data on the share of employees that have obtained at least a tertiary level of education, according to International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED). We also control for the standard of living in the city by including per capita income.

R&D intensity has also been directly linked to entrepreneurship through knowledge spillovers (Acs et al. 2013; Audretsch and Feldman 2004; Leydesdorff and Etzkowitz 1996). We use the share of employees working in R&D to measure the potential for knowledge spillover entrepreneurship.

3.5 Methodology

To analyze our dataset, we rely on a cross-city comparison with time-lagged effects. Because of Germany’s special political history, we have to consider possible biases due to the former socialist regions and cities of Eastern Germany. Our complete sample of the 69 largest urban districts (> 100,000 inhabitants) includes nine ex-socialist cities (Dresden, Erfurt, Halle/Saale, Jena, Leipzig, Magdeburg, Potsdam, Rostock, Chemnitz); however, the results show no evidence that having a socialist heritage makes a significant difference in the average start-up rates. This is inconsistent with recent findings suggesting that socio-cultural heritages persist over a long period of time and even endures institutional shocks, e.g., the broke down of Soviet Union (Fritsch and Wyrwich 2012); but nevertheless, it appears to be reasonable in the context of our small, but full, dataset.

Table 3 reports the correlation matrix. Most variables correlate from very slight to moderate (0.009 ≤ r ≥ 0.5). The correlation between the level of income per capita, R&D, and social diversity is higher, suggesting additional attention (max r ≤ 0.69). However, testing for multi-collinearity reveals inconspicuous values for variance inflation factor (VIF < 10) along all deployed variables.

The challenge for this paper is how to measure and operationalize some kind of subcultural spirit and street culture and delineate it from “mainstream culture.” Previous research within the intersection of culture and entrepreneurship has outlined that findings are mixed and quite sensitive towards measurement issues and the role of context (Thomas and Mueller 2000; Torjman and Worren 2010). Thus, we choose and rely on a multi-dimensional approach including several proxies for which we believe either characterize mainstream culture and subcultures. These variables include amenities, such as the number of museums, theaters, and seats in movie theaters, freelance artists and publicists, the number of independent music labels, vegan restaurants, and health-conscious alternative medical practitioners. We perform exploratory factor analysis with the independent variables to determine the variables related to mainstream or subcultural lifestyles. Exploratory factor analysis is a commonly used statistical technique to identify latent constructs and relevant structural patterns between measured variables. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) studies the covariance aim to summarize a set of variables (Kim and Mueller 1978; Thompson 2004). In our case, we first confine whether there is a statistical relationship between our independent variables and whether these can be systematically summarized into two factors either reflecting mainstream culture or subcultural vibrancy. Subsequently, we use the resulting factor loadings as regressors and estimate their effect on local entrepreneurship and start-up rates. We run the following regression models.

The first equation (model 1) enables a test of our main hypothesis. Accordingly, the presence of subcultural scene explains high rates of start-up activity.

In the next step, we contrast this thesis by estimating the impact of “traditional” culture on entrepreneurship rates (model 2). In order to consider whether there might be a complementary effect of culture and subculture on entrepreneurship, we estimate model 3:

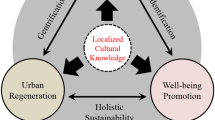

Recent studies on “entrepreneurship ecosystems” reveal particular elements and factor conditions conducive to create a culture for entrepreneurship. In particular, it is the interplay of factors, rather than their just their existence that is important (Malecki 2011; Stam 2015). To test this hypothesis, we estimate model 4 with an interaction between both factor variables.

4 Results

Table 4 reports the results of our factor analysis. First, we investigated what is the optimal number of factors summarizing our suggested measures of cultural attainment versus subcultural life. Considering only factors that the minimum equals an eigenvalue over 1, Table 4 suggests best loading variables for two factors (for factor 1 eigenvalue = 2.03; factor 2 eigenvalue = 1.04; Table 4). The very slight difference between the eigenvalue of factor 1 and factor 2, while the large spread between factor 2 and the factor 3, further supports weighting of our variable only onto two factor loadings. Table 4 also suggests how the variables weigh for each factor and displays the correlation between each variable and factor. The number of museums, theaters, and movie theaters ought to capture mainstream culture, while independent music labels, the number of self-employed artists and freelance publicists, vegan restaurants, and the local supply of alternative medical treatments should be a proxy reflecting subcultures rather than mainstream culture.

Thus, we rotate factor loadings in order to test whether the measures are consistent with our distinction. Factor loadings for the varimax orthogonal rotation show strong correlations between record labels and artists with factor 1 that might reflect subcultural vibrancy. Nevertheless, alternative medical treatment has no significant correspondence when limiting observations to a correlation coefficient minimum equal r = 0.3. Surprisingly, vegan restaurants correspond to factor 2 (r = 0.55), suggesting that they belong to the cultural mainstream rather than subcultures. This might not be as surprising as it looks at first glance. Originally started as a consumer-conscious counter-movement (Cherry 2006, 2015), veganism has garnered considerable resonance and recently evolved to the mainstream stage. Today, vegan meals are available in almost every café, canteen, and super market or even on the menus of legacy airlines. A recent survey by YouGov and the Institute for Opinion Polls (Allensbach 2015) reveals that more than 10% of Germans now live a vegetarian lifestyle and almost 2% are vegans (YouGov 2014).

Alternatively, we deploy promax oblique factor loading rotation to control for the results. In contrast to varimax orthogonal rotation, promax uses oblique rotation loadings that allow factors to be correlated to better approximate structures and improve the interpretability of factors (Abdi 2003; Osborne et al. 2008). Correlations using promax have similar factor loadings except for the number of theaters; these are yet neither loaded to factor 1 nor factor 2. Therefore, promax factor solution comes close to our idea of subculture vs traditional culture. Thus, for the following regression analysis, we deploy factor loadings correspondingly to the results provided by promax oblique rotation, i.e., factor 1 for subculture attainment and factor 2 for mainstream culture.

Table 5 reports the results of our regression analyses. The first model supports our main hypothesis. The factor variable associated with subcultural attainment shows a positive and highly significant impact on start-up rates. This relationship is robust and remains statistically significant when controlling for all other influences. Model 2 tests our alternative hypothesis: The basic linear model finds a significant link between cultural attainment and entrepreneurship, measures by ICT start-ups. However, this effect is for a very poor model fit (pseudo R-squared of 0.015) and becomes insignificant when including all control variables. Model 3 contrasts both factor variables and supports our main hypothesis more strongly. Thus, when including both variables, subculture has a significant impact on start-up rates, indicating that a strong subcultural scene drives creative entrepreneurship, but mainstream cultural attainment does not.

We also controlled for the joint impact of culture and subculture. The results suggest that even after controlling for a possible interaction between both factors, subculture remains significantly related to start-up rates while the influence of culture remains negligible. More interestingly, by including the interaction term, the coefficient of the mainstream culture variable changes sign from positive to negative. However, this effect is not statistically significant. All findings of model 3 and model 4 remain robust when including all controls.

Small sample sizes are generally sensitive to extremes. Nevertheless, most of our regression results continue to be robust when controlling for possible outliers. For example, Baron (2017) and Audretsch and Lehmann (2016) describe how Berlin attracts thousands of would-be entrepreneurs, not only from other parts of Germany but also from the UK and the USA. In our sample, Berlin reports a number of start-ups that is three times higher (n = 545) than the second most entrepreneurial city in Germany, Munich, which has 165 ICT start-ups. However, even when dropping Berlin out of our regression analysis, the findings of model 1, model 3, and model 4 remain robust and display the same levels of significance and signs. Due to low levels of model fit (pseudo R-squared < 0.02), the basic model 2 is sensitive towards outliers. Thus, by dropping Berlin, the factor variable for traditional culture shows no significant impact on start-up rates.

5 Discussion

The results of our analysis strongly confirm our hypothesis that subcultural vibrancy is a prerequisite for more robust start-up activity. This effect appears to be consistent across all models and controls. Our findings also reveal that “traditional” cultural amenities, such as measures of museums and others, are only related to entrepreneurship rates when excluding the role of subcultures and all control variables. This points to a severe limitation in previous research (Bauer et al. 2015; Falck et al. 2011; Rappaport 2008; Zheng 2016). It seems that start-up hotspots co-evolve with subcultures rather than mainstream and cultural amenities in general. Subsequent research might suggest that subcultural amenities together with indie music and artistic scenes serve as a vital source of inspiration and creativity spillovers while providing laboratories for entrepreneurs and their ideas. Therefore, we confirm the results from previous studies finding that vivid creative scenes play an important role in creating a “local buzz” of place-based innovation and entrepreneurship (Asheim and Gertler 2005; Jacobs 1970; Polèse 2012). A vast body of research confirms that density in general, as well as the concentration of skilled and well-educated human capital in particular, is conducive to local entrepreneurship (Dakhli and De Clercq 2004; Meijers 2008; Saxenian 1996; Storper and Scott 2009). Our results support that human capital and urban density are related to high start-up activity. Nevertheless, we find no evidence that high levels of local R&D are conducive to high local start-up activity. Although this seems contradictory to previous research at first glance (Acs et al. 2009), it is barely surprising because our dependent variable measures the rate of start-ups affiliated with the ICT sector, and R&D efforts are usually associated with high-tech innovations and “hard,” patentable industrial research. However, ICT industries require “softer,” i.e., smarter and creative, problem-solving than formal research and development (Acs et al. 2016; Lehmann et al. 2017). An influential stream in the literature has highlighted the particular relationship between human capital, tolerance for diversity, and entrepreneurship-driven growth. In our study, tolerance as reflected by a measure of cultural diversity shows a negative correlation with local start-up rates. This is contradictory to previous estimations (Rutten and Gelissen 2008), but is however consistent with recent studies suggesting that (a) tolerance-entrepreneurship is more nuanced in a context of social trust and economic variables and (b) tolerance is not synonymous with cultural diversity (Beugelsdijk and Klasing 2013; Qian 2013; Welter 2012).

Our empirical analysis bears several limitations regarding our sample. We are aware of the challenges that merge with small sample sizes in terms of reliability and interpretation of the results. Nevertheless, at the same time, our data have a number of unique advantages. First, our measures of subculture are unique and have not, to date, been available for analysis in any country context. Second, entrepreneurship capacity differs in scale and scope across countries, regions, and cities due to national and regional institutions and other socio-cultural constraints (Acs and Szerb 2007; Autio and Acs 2007; Carree and Thurik 2003; Wennekers et al. 2005). Thus, comparing cites within the same country context reduces biases and complexity, and hence improves overall interpretability.

Research on local quality of life and economic development has always been suspected of endogeneity issues (Glaeser 2005; Rappaport 2008). Although there has emerged a broad literature suggesting strategies to account for and identify causal linkages (Bauer et al. 2015; Möller and Tubadji 2009), whether cultural scenes and the attractiveness of a place are the consequence or the cause of economic development is still an open question. However, while our study is also unable to solve the chicken-or-the-egg problem, it is able to contribute to the literature in several ways. First, we provide evidence for the relationship between local cultures and place-based entrepreneurship activity. Therefore, we confirm the findings of previous studies within the entrepreneurship literature. Second, we take a step further and compare different types of local cultures on local start-up activity. We are able to introduce a model for measuring urban subcultures against the mainstream. Third, our findings suggest that not all types of cultures have the same impact on entrepreneurship. Therefore, we partly confirm the findings of previous research highlighting that an inspirational atmosphere of open-mindedness and tolerance is crucial for creating local start-up scene, but they are not necessarily found in places with mainstream people and amenities; rather, it is urban subcultural life that effects local entrepreneurship culture. Fourth, the study adds to our knowledge about the entrepreneurial underclasses and their location preferences. Focusing on subculture rather than the creative class is therefore a useful way to overcome the ongoing contradictions regarding empirical evidence and theorizing about the creative class and the role of culture in entrepreneurship ecosystems.

6 Conclusion and implications

Considerable interest regarding culture has emerged in the regional studies literature, because of its role in attracting the creative class and spurring entrepreneurship. However, the empirical evidence is mixed and fraught with ambiguities and contradictions. This paper has attempted to unravel those ambiguities by drawing on conceptual literature emphasizing the heterogeneous nature of culture. Rather than being represented as a single measure, the heterogeneity inherent in culture is better served by distinguishing between different types of cultures. In particular, this paper developed new and previously untested hypotheses linking this specific type of subculture, as well as the more typical measure of culture, to regional entrepreneurial activity.

The empirical evidence generally provides compelling support for the main hypotheses posited in the paper. Most importantly, it is the subculture, and not necessarily mainstream culture, that is particularly important in generating new firm start-ups in the ICT sector. The implications for public policy may be that it does not suffice to focus on culture in a broad sense as an instrument to spur entrepreneurship. While, in fact, culture does matter, the results of this paper suggest that it may be the particular type of culture, or more specifically subculture, that is the key ingredient for generating entrepreneurial activity. It may not suffice to simply invest in culture generally but rather the particular type of subculture that is conducive to entrepreneurship.

While this paper is the first to provide different measures reflecting disparate types of culture to entrepreneurship within a spatial context, probing other dimensions reflecting the heterogeneity inherent in culture could prove fruitful in subsequent research. We would anticipate future research to build on the results presented in this paper by decomposing culture into key salient components reflecting place-specific idiosyncrasies. In the quest to identify those key elements of an inherently heterogeneous culture that provides a catalyst for entrepreneurship, future research is more likely to identify that those particular types of culture spurring entrepreneurial activity may depend upon characteristics of both the region but also the specific type of entrepreneurship. Still, this paper has made a good start in unravelling the perplexing findings in the extant literature by learning that it may not be culture that matters for entrepreneurship but a particular type, or subculture which spurs entrepreneurial activity.

Within the literature of entrepreneurship, creative class and human capital theory has garnered indisputable attention. Nevertheless, evidence is mixed and has resulted in criticism and widespread discussions across academia. This study aimed to review the main critical arguments and develop an expanded approach that revolves around the impact of subcultures. We argued that an inspirational atmosphere of open-mindedness and social tolerance attracts creative talents, but they are not necessarily found in places with a high share of diversity and an abundance of cultural amenities; however, it is subcultural life that attracts creative and entrepreneurial minds; thus, subcultures rather than mainstream culture drive local start-up activity.

References

Abdi, H. (2003). Factor rotations in factor analyses. Encyclopedia for Research Methods for the Social Sciences (pp. 792–795). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Acs, Z. J., & Szerb, L. (2007). Entrepreneurship, economic growth and public policy. Small Business Economics, 28(2–3), 109–122.

Acs, Z. J., & Varga, A. (2002). Geography, endogenous growth, and innovation. International Regional Science Review, 25(1), 132–148.

Acs, Z. J., Desai, S., & Hessels, J. (2008). Entrepreneurship, economic development and institutions. Small Business Economics, 31(3), 219–234.

Acs, Z. J., Braunerhjelm, P., Audretsch, D. B., & Carlsson, B. (2009). The knowledge spillover theory of entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 32(1), 15–30.

Acs, Z. J., Audretsch, D. B., & Lehmann, E. E. (2013). The knowledge spillover theory of entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 41(4), 757–774.

Acs, Z. J., Audretsch, D. B., Lehmann, E. E., & Licht, G. (2016). National systems of entrepreneurship. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 1–12.

Adamczyk, A., & Pitt, C. (2009). Shaping attitudes about homosexuality: the role of religion and cultural context. Social Science Research, 38(2), 338–351.

Albouy, D. (2016). What are cities worth? Land rents, local productivity, and the total value of amenities. Review of Economics and Statistics, 98(3), 477–487.

Allensbach (2015). Allensbacher UmfrageZahlen Vegetarier. AWA Allensbacher Markt- und Werbeträgeranalysen.

Asheim, B., & Gertler, M. (Eds.). (2005). The geography of innovation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Audretsch, D. B., & Belitski, M. (2013). The missing pillar: the creativity theory of knowledge spillover entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 41(4), 819–836.

Audretsch, D. B., & Feldman, M. P. (2004). Knowledge spillovers and the geography of innovation. Handbook of Regional and Urban Economics, 4, 2713–2739.

Audretsch, D. B., & Lehmann, E. E. (2016). The seven secrets of Germany: economic resilience in an era of global turbulence. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Audretsch, D., Dohse, D., & Niebuhr, A. (2010). Cultural diversity and entrepreneurship: a regional analysis for Germany. The Annals of Regional Science, 45(1), 55–85.

Autio, E., & Acs, Z. J. (2007). Individual and country-level determinants of growth aspiration in new ventures. Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research,27(19), 2.

Bader, I., & Scharenberg, A. (2010). The sound of Berlin: subculture and the global music industry. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 34(1), 76–91.

Badley, E., & Canizares, M. (2016). SAT0579 trends in use of physiotherapists, chiropractors and complementary and alternative medicine practitioners for arthritis over time and across generations. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 75(Suppl 2), 879–879.

Barnes, P. M., Powell-Griner, E., McFann, K., & Nahin, R. L. (2004, June). Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults: United States, 2002. Paper presented at the Seminars in Integrative Medicine. (Vol. 2, No. 2, pp. 54-71). WB Saunders.

Baron, T. (2017). The impact of diaspora ventures on the dynamics of the start-up ecosystem Berlin. Wiesbaden: Springer Gabler.

Basu, A., & Altinay, E. (2002). The interaction between culture and entrepreneurship in London’s immigrant businesses. International Small Business Journal, 20(4), 371–393.

Bauer, T. K., Breidenbach, P., & Schmidt, C. M. (2015). “Phantom of the Opera” or “Sex and the City”? Historical amenities as sources of exogenous variation. Labour Economics, 37, 93–98.

Bayer, P., Keohane, N., & Timmins, C. (2009). Migration and hedonic valuation: the case of air quality. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 58(1), 1–14.

Begg, I. (1999). Cities and competitiveness. Urban Studies, 36(5–6), 795–809.

Berggren, N., & Jordahl, H. (2006). Free to trust: economic freedom and social capital. Kyklos, 59(2), 141–169.

Berry, C. R., & Glaeser, E. L. (2005). The divergence of human capital levels across cities. Papers in Regional Science, 84(3), 407–444.

Bertoni, F., Colombo, M. G., & Grilli, L. (2011). Venture capital financing and the growth of high-tech start-ups: disentangling treatment from selection effects. Research Policy, 40(7), 1028–1043.

Beugelsdijk, S. (2010). Entrepreneurial culture, regional innovativeness and economic growth Entrepreneurship and Culture (pp. 129–154). New York: Springer.

Beugelsdijk, S., & Klasing, M. J. (2013). Cultural diversity. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2336045 or https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2336045. Accessed May 5 2019

Beugelsdijk, S., & Van Schaik, T. (2005). Social capital and growth in European regions: an empirical test. European Journal of Political Economy, 21(2), 301–324.

Boschma, R. A., & Fritsch, M. (2009). Creative class and regional growth: empirical evidence from seven European countries. Economic Geography, 85(4), 391–423.

Breznitz, S. M., & Noonan, D. S. (2014). Arts districts, universities, and the rise of digital media. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 39(4), 594–615.

Caragliu, A., Del Bo, C., & Nijkamp, P. (2011). Smart cities in Europe. Journal of Urban Technology, 18(2), 65–82.

Carree, M. A., & Thurik, A. R. (2003). The impact of entrepreneurship on economic growth Handbook of Entrepreneurship Research (pp. 437–471): Springer.

Cherry, E. (2006). Veganism as a cultural movement: a relational approach. Social Movement Studies, 5(2), 155–170.

Cherry, E. (2015). I was a teenage vegan: motivation and maintenance of lifestyle movements. Sociological Inquiry, 85(1), 55–74.

Clark, T. N. (Ed.). (2003). Urban amenities: lakes, opera, and juice bars: do they drive development?. In The city as an entertainment machine (pp. 103-140).Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Clark, T. N., Lloyd, R., Wong, K. K., & Jain, P. (2002). Amenities drive urban growth. Journal of Urban Affairs, 24(5), 493–515.

Clifton, N., & Cooke, P. (2009). Creative knowledge workers and location in Europe and North America: a comparative review. Creative Industries Journal, 2(1), 73.

Comunian, R. (2010). Rethinking the creative city: the role of complexity, networks and interactions in the urban creative economy. Urban Studies, 48(6), 1157–1179. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098010370626.

Cushing, R., Florida, R., & Gates, G. (2002). When social capital stifles innovation. Harvard Business Review, 80(8), 20.

Dakhli, M., & De Clercq, D. (2004). Human capital, social capital, and innovation: a multi-country study. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 16(2), 107–128.

Davidsson, P. (1995). Culture, structure and regional levels of entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 7(1), 41–62.

De Carolis, D. M., & Saparito, P. (2006). Social capital, cognition, and entrepreneurial opportunities: a theoretical framework. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 30(1), 41–56.

Dhoest, A., Malliet, S., Haers, J., & Segaert, B. (2015). The borders of subculture: resistance and the mainstream: Routledge.

Donegan, M., Drucker, J., Goldstein, H., Lowe, N., & Malizia, E. (2008). Which indicators explain metropolitan economic performance best? Traditional or creative class. Journal of the American Planning Association, 74(2), 180–195.

Evans, C. (1997). Street style, subculture and subversion. Costume, 31(1), 105–110.

Evans, G. (2009). Creative cities, creative spaces and urban policy. Urban Studies, 46(5–6), 1003–1040.

Falck, O., Fritsch, M., & Heblich, S. (2011). The phantom of the opera: cultural amenities, human capital, and regional economic growth. Labour Economics, 18(6), 755–766.

Fischer, C. S. (1975). Toward a subcultural theory of urbanism. American Journal of Sociology, 80(6), 1319–1341.

Florida, R. (1995). Toward the learning region. Futures, 27(5), 527–536.

Florida, R. (2002). The rise of the creative class and how it’s transforming work, leisure, community and everyday life (Paperback Ed.). New York: Basic Books.

Florida, R. (2003). Entrepreneurship, creativity, and regional economic growth. In The Emergence of Entrepreneurship Policy (pp. 39–58).

Florida, R. (2005). Cities and the creative class. London: Routledge.

Florida, R. (2014). The creative class and economic development. Economic Development Quarterly, 28(3), 196–205.

Florida, R., & Gates, G. (2003). Technology and tolerance: the importance of diversity to high-technology growth. Research in Urban Policy, 9(1), 199–219.

Florida, R., & Mellander, C. (2015). Talent, cities, and competitiveness. In The Oxford handbook of local competitiveness (pp. 34–53). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Fritsch, M., & Wyrwich, M. (2012). The long persistence of regional entrepreneurship culture: Germany 1925–2005. DIW Berlin Discussion Paper No. 1224. Available at SSRN:http://ssrn.com/abstract=2111984.

Glaeser, E. L. (2005). Edward L. Glaeser, Review of Richard Florida’s The Rise of the Creative Class. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 35(5), 593–596.

Glaeser, E. L., & Gottlieb, J. D. (2006). Urban resurgence and the consumer city. Urban Studies, 43(8), 1275–1299.

Glaeser, E. L., Kolko, J., & Saiz, A. (2001). Consumer city. Journal of Economic Geography, 1(1), 27–50.

Glaeser, E. L., Gyourko, J., & Saiz, A. (2008a). Housing supply and housing bubbles. Journal of Urban Economics, 64(2), 198–217.

Glaeser, E. L., Kahn, M. E., & Rappaport, J. (2008b). Why do the poor live in cities? The role of public transportation. Journal of Urban Economics, 63(1), 1–24.

Glaeser, E. L., Resseger, M., & Tobio, K. (2009). Inequality in cities. Journal of Regional Science, 49(4), 617–646.

Glaeser, E. L., Rosenthal, S. S., & Strange, W. C. (2010). Urban economics and entrepreneurship. Journal of Urban Economics, 67(1), 1–14.

Hackler, D., & Mayer, H. (2008). Diversity, entrepreneurship, and the urban environment. Journal of Urban Affairs, 30(3), 273–307.

Hall, S., & Jefferson, T. (1993). Resistance through rituals: youth subcultures in post-war Britain. London: Psychology Press.

Hansen, H. K., & Niedomysl, T. (2009). Migration of the creative class: evidence from Sweden. Journal of Economic Geography, 9(2), 191–206.

Hauser, C., Tappeiner, G., & Walde, J. (2007). The learning region: the impact of social capital and weak ties on innovation. Regional Studies, 41(1), 75–88.

Hebdige, D. (1995). Subculture: the meaning of style. Critical Quarterly, 37(2), 120–124.

Heebels, B., & van Aalst, I. (2010). Creative clusters in Berlin: entrepreneurship and the quality of place in Prenzlauer Berg and Kreuzberg. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography, 92(4), 347–363.

Hirschle, J., & Kleiner, T.-M. (2014). Regional cultures attracting interregional migrants. Urban Studies, 51(16), 3348–3364.

Hollands, R. G. (2008). Will the real smart city please stand up? Intelligent, progressive or entrepreneurial? City, 12(3), 303–320.

Hopp, C., & Stephan, U. (2012). The influence of socio-cultural environments on the performance of nascent entrepreneurs: community culture, motivation, self-efficacy and start-up success. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 24(9–10), 917–945.

Huggins, R., & Thompson, P. (2014). Culture, entrepreneurship and uneven development: a spatial analysis. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 26(9–10), 726–752.

Hutton, T. A. (2006). Spatiality, built form, and creative industry development in the inner city. Environment and Planning, 38(10), 1819–1841.

Inglehart, R. (2004). Human beliefs and values: a cross-cultural sourcebook based on the 1999–2002 values surveys: Siglo XXI.

Inglehart, R., Foa, R., Peterson, C., & Welzel, C. (2008). Development, freedom, and rising happiness: a global perspective (1981–2007). Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3(4), 264–285.

Isenberg, D. J. (2011). The entrepreneurship ecosystem strategy as a new paradigm for economic policy: principles for cultivating entrepreneurship. Presentación ante el Instituto de Asuntos Internacionales u Europeos.

Jacobs, J. (1970). The economy of cities. New York: Random House.

Kerr, W. R., Nanda, R., & Rhodes-Kropf, M. (2014). Entrepreneurship as experimentation. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 28(3), 25–48.

Kim, J.-O., & Mueller, C. W. (1978). Factor analysis: statistical methods and practical issues (Vol. 14). London: Sage.

Kloosterman, R. C. (2005). Come together: an introduction to music and the city. Built Environment, 31(3), 181–191.

Kloosterman, R. C. (2014). Cultural amenities: large and small, mainstream and niche—a conceptual framework for cultural planning in an age of austerity. European Planning Studies, 22(12), 2510–2525.

Knudsen, B., Florida, R., Stolarick, K., & Gates, G. (2008). Density and creativity in U.S. regions. Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 98(2), 461–478.

Kuratko, D. F. (2005). The emergence of entrepreneurship education: development, trends, and challenges. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 29(5), 577–598.

Landry, C. (2008). The creative city: a toolkit for urban innovators. Sterling: Dunstan House.

Lee, N. (2014). Migrant and ethnic diversity, cities and innovation: firm effects or city effects? Journal of Economic Geography. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbu032.

Lee, S. Y., Florida, R., & Gates, G. (2010). Innovation, human capital, and creativity. International Review of Public Administration, 14(3), 13–24.

Lehmann, E. E. (Ed.). (2015). The role of universities in local and regional competitiveness. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lehmann, E. E., & Menter, M. (2016). University-industry collaboration and regional wealth. Journal of Technology Transfer, 41(6), 1284–1307.

Lehmann, E. E., & Seitz, N. (2017). Creativtiy and entrepreneurship: culture, subcultures and the impact on new venture creation. State-of-the-art and some descriptive statistics and data. In M. Wagner, J. W. Pasola, & T. Burger-Helmchen (Eds.), Global Management of Creativity (pp. 97–120). London: Routhledge.

Lehmann, E. E., Seitz, N., & Wirsching, K. (2017). Smart finance for smart places to foster new venture creation. Economia e Politica Industriale, 44(1), 51–75.

Letki, N. (2008). Does diversity erode social cohesion? Social capital and race in British neighbourhoods. Political Studies, 56(1), 99–126.

Leydesdorff, L., & Etzkowitz, H. (1996). Emergence of a triple helix of university—Industry—government relations. Science and Public Policy, 23(5), 279–286.

Lloyd, R., & Clark, T. N. (2001). The city as an entertainment machine. Critical Perspectives on Urban Redevelopment, 6(3), 357–378.

Mack, E., & Mayer, H. (2015). The evolutionary dynamics of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Urban Studies, 53(10), 2118–2133.

Malecki, E. J. (2011). Connecting local entrepreneurial ecosystems to global innovation networks: open innovation, double networks and knowledge integration. International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation Management, 14(1), 36–59.

Marshall, A. (1920). Industry and trade.

McGranahan, D. A., & Wojan, T. (2007). Recasting the creative class to examine growth processes in rural and urban counties. Regional Studies, 41(2), 197–216.

McGranahan, D. A., Wojan, T. R., & Lambert, D. M. (2010). The rural growth trifecta: outdoor amenities, creative class and entrepreneurial context. Journal of Economic Geography, 11(3), 529–557.

Meijers, E. (2008). Summing small cities does not make a large city: polycentric urban regions and the provision of cultural, leisure and sports amenities. Urban Studies, 45(11), 2323–2342.

Mellander, C., Florida, R., & Stolarick, K. (2011). Here to stay—the effects of community satisfaction on the decision to stay. Spatial Economic Analysis, 6(1), 5–24.

Möller, J., & Tubadji, A. (2009). The creative class, bohemians and local labor market performance: a micro-data panel study for Germany 1975—2004. Jahrbücher für Nationalökonomie und Statistik, 270–291.

Moretti, E. (2004). Human capital externalities in cities. In G. Duranton, J. V. Henderson, & W. C. Strange (Eds.), Handbook of regional and urban economics (Vol. 5, pp. 2243–2291).

Morgan, G., & Ren, X. (2012). The creative underclass: culture, subculture, and urban renewal. Journal of Urban Affairs, 34(2), 127–130.

Obschonka, M., Schmitt-Rodermund, E., Silbereisen, R. K., Gosling, S. D., & Potter, J. (2013). The regional distribution and correlates of an entrepreneurship-prone personality profile in the United States, Germany, and the United Kingdom: a socioecological perspective. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 105(1), 104.

Obschonka, M., Stuetzer, M., Gosling, S. D., Rentfrow, P. J., Lamb, M. E., Potter, J., & Audretsch, D. B. (2015). Entrepreneurial regions: do macro-psychological cultural characteristics of regions help solve the “knowledge paradox” of economics? PLoS One, 10(6), e0129332.

Osborne, J. W., Costello, A. B., & Kellow, J. T. (2008). Best practices in exploratory factor analysis. Best Practices in Quantitative Methods, 86–99.

Park, R. E., Burgess, E. W., & McKenzie, R. D. (1925/1984). The city. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Peck, J. (2005). Struggling with the creative class. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 29(4), 740–770.

Pflüger, M., & Südekum, J. (2008). A synthesis of footloose-entrepreneur new economic geography models: when is agglomeration smooth and easily reversible. Journal of Economic Geography, 8(1), 39–54.

Polèse, M. (2012). The arts and local economic development: can a strong arts presence uplift local economies? A study of 135 Canadian cities. Urban Studies, 49(8), 1811–1835.

Porter, M. E. (1998). Clusters and the new economics of competition (Vol. 76). Boston: Harvard Business Review.

Porter, M. E. (2000). Location, competition, and economic development: local clusters in a global economy. Economic Development Quarterly, 14(1), 15–34.

Portes, A., & Vickstrom, E. (2011). Diversity, social capital, and cohesion. Annual review of sociology, 37, 461-479.

Pratt, A. C. (2008). Creative cities: the cultural industries and the creative class. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography, 90(2), 107–117.

Pratt, A. C. (2011). The cultural contradictions of the creative city. City, Culture and Society, 2(3), 123–130.

Qian, H. (2013). Diversity versus tolerance: the social drivers of innovation and entrepreneurship in US cities. Urban Studies, 50(13), 2718–2735.

Rappaport, J. (2008). Consumption amenities and city population density. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 38(6), 533–552.

Rauch, A., Frese, M., Wang, Z.-M., Unger, J., Lozada, M., Kupcha, V., & Spirina, T. (2013). National culture and cultural orientations of owners affecting the innovation–growth relationship in five countries. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 25(9–10), 732–755.