Abstract

Equity crowdfunding is an emerging area of research within the broader sphere of entrepreneurship. Since 2012, research activities are steadily advancing, providing the foundation for a promising field of research. Despite ongoing scientific discussions, equity crowdfunding research is still in its infancy and scholarly knowledge remains limited and fragmented. To bring clarity to this fragmented field and to further advance the scientific process, we conduct a systematic literature review of 113 journal contributions and gray papers, published between 2012 and 2017. Based on an in-depth analysis of identified publications, we describe the landscape of the equity crowdfunding field concentrating on two aspects. First, we conduct a descriptive analysis of equity crowdfunding research to illustrate the scientific development. Second, we categorize relevant contributions into five different perspectives: capital market, entrepreneur, institutional, investor, and platform and perform a thematic analysis to reveal dominant themes and sub-themes within each perspective. Our study highlights several promising directions for encouraging further advancements in equity crowdfunding research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Equity crowdfunding, an innovative way to raise external capital for new ventures (Ahlers et al. 2015; Estrin et al. 2018; Vismara 2018a), is emerging as a promising research area within the broader sphere of entrepreneurship research (Cholakova and Clarysse 2015; McKenny et al. 2017). Since the publishing of the seminal works by Belleflamme et al. (2011) and Ahlers et al. (2012), the number of equity crowdfunding studies has increased by 620% from 2012 to 2017 (Fig. 1). Researchers, practitioners, and policy makers highlight the importance of equity crowdfunding as a viable source for financing new ventures (e.g., Bruton et al. 2015; Massolution 2015; Younkin and Kashkooli 2016). The ongoing scientific discussion of equity crowdfunding in various academic entrepreneurship journals (e.g., ET&P, JBV, Small Business Economics: An Entrepreneurship Journal, Venture Capital: An International Journal of Entrepreneurial Finance) contributes to the on-going legitimization of equity crowdfunding as a sub-field of entrepreneurial finance research. Furthermore, the integration of theories and concepts from areas like social psychology (Cholakova and Clarysse 2015), marketing (Moysidou and Spaeth 2016), as well as management and finance (e.g., Vismara 2018b, 2016; Ahlers et al. 2015; Vulkan et al. 2016) display its inherent interdisciplinary nature as a research field. In addition, the scientific debate about equity crowdfunding in peer-reviewed academic journals not dedicated to entrepreneurship (e.g., Management Science, Information, and Organization; Industrial Management & Data Systems; California Management Review; The Journal of Corporation Law) indicates the increasing significance of equity crowdfunding outside the narrow entrepreneurship research context.

However, despite the ongoing scientific and practical discourse, research on equity crowdfunding is still in its infancy, with limited and fragmented scientific knowledge (Short et al. 2017; McKenny et al. 2017; Block et al. 2018a; Cumming and Johan 2017a). The steady growth and multidisciplinary nature of the field make systematizing the current body of equity crowdfunding literature difficult, and a holistic overview of the field is needed. Thus, equity crowdfunding as a scientific field is at risk of stagnation and lacks robustness (Fayolle and Liñán 2014; Liñán and Fayolle 2015). Hence, the purpose of this study is to systematically review, categorize, and synthesize the existing body of knowledge to compile a distinct landscape of the scientific development. To provide a holistic overview of the current state of the art of equity crowdfunding research, our review is guided by the following questions:

- (1)

How has equity crowdfunding literature evolved since its establishment?

- (2)

Which perspectives dominate research on equity crowdfunding?

- (3)

What are the emerging themes that dominate equity crowdfunding research and what future research is needed?

To answer our research questions, we conduct a systematic literature review (Tranfield et al. 2003) examining 113 scientific equity crowdfunding contributions, advanced by inductive thematic coding, (Braun and Clarke 2006; Jones et al. 2011) to identify themes and sub-themes of current equity crowdfunding research. To the authors’ knowledge, there is no systematic literature review covering equity crowdfunding. Recent reviews focus on crowdfunding and equity financing in general and derive future research questions without making a clear distinction between the various forms of crowdfunding (e.g., Moritz and Block 2016; Guan 2016; Gleasure and Feller 2016; Wallmeroth et al. 2018).

However, equity crowdfunding differs significantly from other crowdfunding forms. First, equity crowdfunding contains investment decisions with a prospect of a potential return on investment. Thus, the risk-return equation of equity crowdfunding implies higher risk levels compared to reward-based crowdfunding (Bapna 2017), where funders get material or immaterial rewards for their financial support or, in case the funding limit is not reached, a refund. Second, equity crowdfunding (crowd-) investors are less experienced and face large information asymmetries when evaluating new businesses (Ahlers et al. 2015; Bapna 2017). Due to these differences, our review concentrates exclusively on equity crowdfunding and reveals potential research streams, which are of particular interest for equity crowdfunding scholars.

Our systematic review contributes to the advancement of the field in several ways. First, we analyze the development of the literature and identify current methodological approaches. Second, we highlight current research themes and provide several implications for encouraging and guiding future research activities based on the various identified themes and sub-themes. For ensuring transparency and replicability, our approach follows “best practices” in systematic entrepreneurship literature reviews (e.g., Jones et al. 2011; Pittaway and Cope 2007; Macpherson and Holt 2007; Liñán and Fayolle 2015; Thorpe et al. 2005).

Our study continues as follows. In the next section, we summarize the method applied, and also illustrate the literature search and review strategy. We then present the findings of our systematic literature review, including a descriptive analysis of the scientific development of equity crowdfunding research, the synthesized results of the thematic analysis, and emphasize possible avenues for future research. We conclude by summarizing our main findings, considering the limitations of our study, and highlighting the implications of our review for further equity crowdfunding research.

2 Methods

Systematic literature reviews offer a suitable method for conducting a scientific overview of research activities within a specific field (Petticrew and Roberts 2006). To provide a clear overview of the scientific development and emerging research themes, we apply a variation of systematic literature reviews that base the synthesis on a content-based evaluation of relevant publications (Jones et al. 2011). Therefore, we enhance the systematic review process outlined by Tranfield et al. (2003) by including an inductive approach of thematic analysis, a method commonly used in qualitative psychology (Braun and Clarke 2006; Jones et al. 2011). To ensure transparency and replicability, we follow the approach of systematic literature reviews outlined by Tranfield et al. (2003). The following section describes the adaption of these stages, adjusted to our research objective.

2.1 Planning the review

In the planning phase, we define suitable search terms for the selection of relevant contributions. We derived the search terms from different articles using various synonyms for equity crowdfunding, like “equity-based crowdfunding” or “crowdinvesting.”Footnote 1 To guarantee transparency, we base the selection of relevant contributions on specific inclusion and exclusion criteria (Tables 12, 13 in the appendix). To facilitate comparability among contributions, we include only those scientific publications with an abstract. Our sample consists of published and unpublished scientific contributions, e.g., journal articles, conference proceedings, working papers, and papers in edited volumes. Other publication forms, such as books, book chapters, industry reports, commentaries, and editorials, are not included due to restricted availability (Jones et al. 2011; Liñán and Fayolle 2015) and the absence of abstracts. For ensuring a transparent process of our review, we establish detailed protocols, including the literature research (Table 14 in the appendix).

2.2 Conducting the review

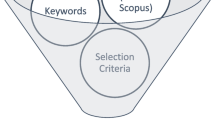

The process of our review includes several steps based on the three stages (planning, conducting, and reporting) demonstrated by Tranfield et al. (2003). As a first step, we conducted an in-depth literature search in five databases, including Babson College, EBSCO, Elsevier, Google Scholar, and Web of Science. Considering the interdisciplinary nature of equity crowdfunding, we do not concentrate our search solely on citation databases. Therefore, we include Google Scholar in our search, using the Publish or Perish software, version 4. As a multidisciplinary database, Google Scholar is not limited to ISI listed journals, it includes non-English publications, and it provides increased coverage of unpublished contributions, like working papers and conference proceedings (Harzing and van der Wal 2008; Kousha and Thelwall 2007). For each database, we used the search string “Crowdinvesting” OR “Equity Crowdfunding” OR “Equity-based Crowdfunding” within the title, abstract, and keywords. The search covered studies between 2012 and 2017 and was limited to contributions published in English or German. The database search identified 3285 possibly relevant contributions. To ensure that equity crowdfunding was the main research topic, we screened identified contributions against our search terms, by reviewing the title, abstracts, and keywords. After applying all inclusion and exclusion criteria, the review process resulted in 113 relevant contributions.Footnote 2

2.3 Data synthesis

To illustrate the distinct landscape of current research on equity crowdfunding, we conduct an inductive, interpretation-based approach of theme identification (Jones et al. 2011). For ensuring transparency and replicability, we follow a systematic procedure to identify themes, as outlined by Braun and Clarke (2006). Thematic analysis originates from psychological science and provides a suitable “method for analyzing and reporting patterns within data” (Braun and Clarke 2006, p. 79). According to Ryan and Bernard (2003), a theme illustrates the fundamental concepts of analyzed data. In our review, the data consists of scientific equity crowdfunding contributions, with themes derived inductively by reviewing each paper. Consequently, the identified themes are reflections of its content, thus representing core ideas and arguments resulting from the specific research questions and aims (Jones et al. 2011; Liñán and Fayolle 2015; Thorpe et al. 2005).

Our understanding of each publication was formed by the stated aims, research questions, results, implications, and the conclusion. To minimize subjectivity in theme identification, we based the categorization and classification of relevant contributions on the collective judgment of three researchers. Any discrepancies in theme identification were discussed and minor adjustments incorporated. In the case that a publication addressed multiple themes, the stated aim of the paper served as our decision-criteria for categorization and classification (Liñán and Fayolle 2015). For providing a precise thematic landscape, we first categorized the relevant contributions according to the different stakeholders within the equity crowdfunding ecosystem, resulting in the five categories of Capital Market Perspective, Entrepreneur Perspective, Institutional Perspective, Investor Perspective, and Platform Perspective.

3 Reporting the findings

In the following section, we illustrate the synthesis of the analyzed contributions in two successive steps. To provide a detailed “rough-cut” of the development of equity crowdfunding research, the first step consists of a descriptive analysis of the body of literature. As the next step, we report the findings resulting from our thematic analysis. Therefore, we illustrate the identified themes and sub-themes, discuss possible inconsistencies, and highlight implications and avenues for advancing further research on equity crowdfunding.

3.1 Descriptive analysis of equity crowdfunding research

Recent studies that also adopted the systematic process outlined by Tranfield et al. (2003) (e.g., Macpherson and Holt 2007; Thorpe et al. 2005; Pittaway and Cope 2007) descriptively analyze the literature concerning methodological information and geographical coverage. Our descriptive analysis is oriented on the studies above; however, we also address the distribution of publication forms as well as journals and conferences that have accepted contributions on equity crowdfunding followed by a short discussion.

3.1.1 Development of the body of literature

Since 2012, the equity crowdfunding research is growing, as reflected by a wide variety of publication forms, including books, journal articles, and working papers, among others. Figure 2 presents the distribution of research among journal articles (n = 62) and non-journal articles (n = 51). The variety of journals that so far published equity crowdfunding research is summarized in Fig. 3, and Table 1 shows the distribution of research articles within entrepreneurship journals.

3.1.2 Conferences on equity crowdfunding

In addition to the acceptance of leading entrepreneurship journals, equity crowdfunding is increasingly included in various scientific conferences. Table 2 summarizes conferences within an entrepreneurship context as well as conferences not dedicated to entrepreneurship, which so far provide an audience for equity crowdfunding research.

3.1.3 Geographical coverage

With regard to the locus of the reviewed studies, the majority of our analyzed sample fall primarily in two regions: Europe and the USA. Within Europe, the majority of studies use data from Germany, followed by the UK, and then other European countries like Austria, France, Italy, the Netherlands, Sweden, and Switzerland (see Table 3). Very few studies included data from other nations like Australia, Brazil, Canada, China, India, New Zealand, Singapore, and Taiwan.

3.1.4 Methodological information

Regarding methods applied (Table 4), 59.28% of studies in our sample are empirical studies. Then, 36.28% used quantitative designs including multivariate analysis and descriptive statistics. For observational studies, the sample size ranged from 30 to 1487 campaigns whereas survey studies varying from 136 to 610 respondents. Further, 22.12% of our sample apply qualitative designs, including single or multiple case studies, interview-based studies, or reviews. Qualitative studies vary from 6 to 68 participants. The majority of empirical studies included data from European equity crowdfunding platforms, like WiSeed (France); Companisto, Innovestment, and Seedmatch (Germany); Symbid (Netherlands); and Crowdcube and Seedrs (UK). Only a few empirical contributions use data from platforms like ASSOB from Australia; Dajiatou and Zhongchou from China; or AngelList and EquityNet from the USA.

3.1.5 Observations and implications

As a general observation, we can emphasize that equity crowdfunding is a young field of research that is currently on track to being established in the academic community. The increasing number of publications in journals dedicated to, e.g., entrepreneurship, law, information systems, and business and management, demonstrates the significance of equity crowdfunding inside and outside the narrow entrepreneurship context as well as the multidisciplinary nature of equity crowdfunding research. As a subfield of entrepreneurial finance, equity crowdfunding combines various concepts (e.g., entrepreneurship, finance, law) and led to new research avenues referring to these concepts (Cumming and Groh 2018; Cumming and Johan 2017b; Cumming and Vismara 2017). Therefore, it is not surprising that the majority of our sample is published in entrepreneurship and law journals (in each case 29.03%). However, only a few studies (4.84%) were published in finance journals (e.g., Moritz et al. 2015; Chen et al. 2016; Turan 2015), whereas the leading finance journals (e.g., Journal of Finance, Journal of Financial Economics, Review of Financial Studies, Journal of Corporate Finance) remain uncovered. Traditionally, research on entrepreneurial finance has its origin in entrepreneurship journals (e.g., ET&P, JBV), which are still dominant in publishing research activities referring to entrepreneurial finance topics (Cumming and Johan 2017b). Similar to entrepreneurial finance in general also equity crowdfunding research was first published in these entrepreneurship journals (Cumming and Johan 2017b). One possible reason for the pioneering role of entrepreneurship journals referring to equity crowdfunding publications could be the interdisciplinary nature of the field. Referring to Cumming and Johan (2017b), finance journals are disciplinary-focused and therefore tend to reject multidisciplinary research on entrepreneurial finance, i.e., equity crowdfunding. In addition, finance scholars are less likely to reference research in entrepreneurship journals, e.g., research on equity crowdfunding (Cumming and Groh 2018; Cumming and Johan 2017b; Cumming and Vismara 2017) which may lead to hurdles regarding the scientific process of equity crowdfunding. These circumstances highlight the needs for interdisciplinary exchanges between finance and entrepreneurship scholars, to reduce the risks of segmented research and stagnation (Cumming and Vismara 2017).

Despite the infant state of equity crowdfunding research, the existing diversity of empirical studies is somewhat surprising. Numerous studies empirically analyze the behavior of market participants and the underlying mechanisms, thus serving as a base for the further development of equity crowdfunding research. However, the majority of empirical studies are observational studies. Only three studies employ an experimental design. Thus, for further advancing equity crowdfunding as a research field, we encourage scholars to apply experimental designs. Equity crowdfunding is characterized by interactions between various stakeholders, conditions of uncertainty, and asymmetric information. Therefore, equity crowdfunding seems to be well suited for employing experimental research designs. While results based on observations could be affected by unobserved variables, conducting experiments could lead to the disclosure of causalities (Azoulay et al. 2013). Within an equity crowdfunding context, experiments could confirm, if not extend, the results of observational studies (e.g., Ahlers et al. 2015; Vismara 2018b, 2016; Vulkan et al. 2016; Li et al. 2016) to quantify possible causal-effects. As a bonus, results based on experimental designs are more replicable (Manzi 2012).

3.2 Thematic analysis

In this section, we report the findings resulting from our thematic analysis. To navigate through the complexity, we present and discuss our results along the identified perspectives. The 113 relevant contributions can be divided into 5 different categories: Capital Market Perspective, Entrepreneur Perspective, Institutional Perspective, Investor Perspective, and Platform Perspective. For each perspective, we present the synthesis of each theme and possible opportunities for further advancing equity crowdfunding research. Within each perspective, several themes and subthemes emerged, which we highlighted in italics.

3.2.1 Capital market perspective

In this section, we report the synthesis of contributions that analyze the potential relevance for the early-stage venture capital market. In sum, we assign 14 publications (Table 5) to this category addressing two themes: functioning and development and the potential role of equity crowdfunding alongside traditional finance alternatives. Two studies provide a review of existing literature.

Functioning and development of equity crowdfunding

For analyzing the functioning of equity crowdfunding, some studies (Grüner and Siemroth 2016; Kumar et al. 2015) develop a theoretical model. Based on a Bayesian investment game, Grüner and Siemroth (2016) investigate theoretically, which circumstances lead to an efficient allocation of capital to new ventures. The authors argue that an efficient capital allocation can be achieved when the difference between income and wealth among investors is rather small, and all investors are wealthy enough to invest. In other words, wealth inequality among investors will lead to inefficient capital allocation, because investments only reflect preferences of investors who are wealthy enough to invest, but not the future demand. In a similar setting, Kumar et al. (2015) analyze the design of an optimal crowdfunding contract. The authors develop a theoretical model where a monopoly wants to raise funds via equity crowdfunding. Based on this model, Kumar et al. (2015) suggest that a specific funding target and a pre-sales price determine an optimal crowdfunding contract. For an efficient functioning of equity crowdfunding (e.g., fraud preventing), it is also crucial to find ways to mitigate potential risks for stakeholders. Two studies (Tomboc 2013; Turan 2015) address potential risks from a stakeholder’s perspective. To solve the risk of asymmetric information, Tomboc (2013) explores the rationales for a “lemons problem” in equity crowdfunding. He concludes that reputation systems—like on eBay or Amazon—friendship networks, and discussion boards have the potential to signal quality to potential investors and thus effectively reduce information asymmetries. Turan (2015) classifies potential risk factors stakeholders are facing into five different categories: financial, regulatory, operational, reputational, and strategic risks. He argues that to reach its fullest potential, equity crowdfunding needs to mitigate these risks by implementing specific risk reduction measures, like establishing a secondary market for shares, investor education, or third party judges to evaluate the quality of ventures. Pelizzon et al. (2016) provide a descriptive overview of the development of equity crowdfunding and distinguish between the various forms existing.

3.2.2 Potential role of equity crowdfunding

With regard to the potential role of equity crowdfunding within the entrepreneurial finance landscape, seven studies address this subject. Nascimento and Querette (2013) review various contexts in which equity crowdfunding has been applied to derive its potential for Brazilian entrepreneurs. The authors argue that equity crowdfunding could promote micro-businesses in Brazil, due to mitigating financial constraints. Hornuf and Schiwenbacher (2016) and Borello et al. (2015) study the question, whether equity crowdfunding will complement or substitute traditional financing forms. By comparing equity crowdfunding practices of different countries with angel financing (Hornuf and Schwienbacher 2016) and analyzing the business models and organizational structure of 119 European crowdfunding platforms (Borello et al. 2015), both studies conclude that no clear answer exists. Due to differences in platform designs and regulatory frameworks in some countries, equity crowdfunding might play both roles, as a complement and a substitute. Abdullah and Oseni (2017) examine the potential of equity crowdfunding in Islamic finance. By analyzing six equity crowdfunding platforms registered in Malaysia, the authors highlight the need for a Shari’ah compliant financing platform for halal SMEs. Based on the principles of Islamic finance, Abdullah and Oseni (2017) provide an equity crowdfunding model to facilitate access of halal SMEs to equity crowdfunding. Mokhtarrudin et al. (2017) analyze the potential role of equity crowdfunding as a funding alternative for Malaysian micro businesses. Based on a survey of 202 micro-entrepreneurs, the authors highlight that micro businesses are less likely to prefer equity crowdfunding due to the higher risks associated with equity crowdfunding. Kim and Moor (2017) illustrate the potential of equity crowdfunding for social enterprises. The authors argue that due to the increased difficulties of receiving external capital from traditional financiers, equity crowdfunding might be a promising alternative to meet the financing needs of small social enterprises.

Dilger et al. (2017) analyze the suitability of equity crowdfunding for energy co-operatives. Based on a multiple case study approach (22 cases), the authors illustrate that equity crowdfunding can be a financial alternative for energy co-operatives. In addition, equity crowdfunding is seen as an appropriate add-on referring to strengthening network ties and acquire more potential members.

3.2.3 Review

Two studies in this category provide a literature review on crowdfunding research. Moritz and Block (2016) review 92 crowdfunding contributions, including all forms of crowdfunding. The authors classify the literature according to the main actors (capital seekers, capital providers, intermediaries) and highlight future research streams referring to all crowdfunding. Similarly, Gleasure and Feller (2016) review 120 crowdfunding contributions, as well including all forms and provide further research areas.

3.2.4 Discussion and future research avenues for the capital market perspective

The majority of publications in this perspective are conceptual and theorize about the role of equity crowdfunding as a complement to, or substitute for, entrepreneurial finance. Since some studies argue that equity crowdfunding can play a supporting role in reducing the early stage gap (e.g., Hagedorn and Pinkwart 2016; Moritz and Block 2016), it is astonishing that no study examines how this could function. Therefore, turning to future research avenues, we strongly support the notion of Block et al. (2018a) to explore how, and to what extent, can equity crowdfunding contribute to reducing the early- stage-financing gap? In line with this, scholars need to clarify to what extent equity crowdfunding can complement established forms of early-stage venture financing, such as bank loans or business angel investments. As some authors argue that equity crowdfunding serves as a complement to conventional funding sources (Gabison 2014; Bruton et al. 2015; Lukkarinen et al. 2016; Short et al. 2017), interested scholars could examine how does equity crowdfunding interact with traditional financing forms? Some studies provide evidence, that the proportion of successful equity crowdfunded ventures is higher compares to ventures receiving venture capital (Ahlers et al. 2015; Cumming et al. 2018a; b). Thus it might be of interest if a successful campaign can also serve as a signal for professional investors to provide subsequent financing. Professional investors might be interested in equity crowdfunded ventures due to the reason of portfolio diversification (Cumming et al. 2018a). More precisely, does the use of equity crowdfunding increase the probability of subsequent financing (e.g., business angels, venture capitalists, etc.)? How do successful equity crowdfunding campaigns influence the behavior of VC and BA when considering crowdfunded ventures as investment opportunities? What are the potential barriers for professional investors to consider successful equity crowdfunded ventures as an investment opportunity?

Another promising research avenue could lie in the analysis of how country-specific differences can influence equity crowdfunding outcomes. Some studies show that equity crowdfunding practices differ due to various country-specific regulationsFootnote 3 (Hornuf and Schwienbacher 2016; Borello et al. 2015). Thus, to explore the effects of country-specific characteristics, it might be of scholarly interest to analyze how contextual conditions can influence equity crowdfunding outcomes. Since McKenny et al. (2017, p. 8) claim, “we need to understand the higher-level antecedents, consequences, and contexts of crowdfunding,” we see great potential in examining how, e.g., socio-cultural factors can affect funding outcomes in specific countries? Analyzing socio-cultural factors can be a first step toward understanding why funding performance differs across nations (McKenny et al. 2017).

With regard to mitigate potential risks for various stakeholders in equity crowdfunding, few studies conclude that risk reduction measures like comments or discussion boards or the implementation of a secondary market might have the potential to overcome informational and finance risks (Tomboc 2013; Turan 2015). Since the UK platform Seedrs announced in May 2017, the introduction of a secondary market for trading equity crowdfunding shares,Footnote 4 future research can explore how this implementation can influence equity crowdfunding performance. To the knowledge of the authors, before the Seedrs announcement, only the German platform Innovestment maintains a second price auction similar to a secondary market. Since no study investigates the design and possible effect of a secondary market in equity crowdfunding, we strongly support the call of McKenny et al. (2017) to analyze the development, design, and impact of secondary markets. Since literature on mitigating information asymmetries also remains quite limited, exploring the mechanisms for reducing information asymmetries in equity crowdfunding is a promising avenue of research. As compared to other forms, investors in equity crowdfunding have limited possibilities to reduce information asymmetries through contracts, pre-investment screening, and post-investment monitoring. As nearly all-active equity crowdfunding boards already implemented investor discussion boards, interested scholars could investigate to what extent platform provided discussion boards are suitable to mitigate information asymmetries. More precisely, can active discussions lead to a reduction of perceived information asymmetries?

3.3 Entrepreneur perspective

The studies in this category address issues relevant for the entrepreneur as an actor within the equity crowdfunding eco-system. In sum, we identify 26 contributions (Table 6) that can be clustered into three themes: rationales for equity crowdfunding, determinants of campaign success, and gender issues.

3.3.1 Rationales for equity crowdfunding

As equity crowdfunding evolves as a viable source of external capital for young and innovative ventures (Cholakova and Clarysse 2015; Vismara 2018b), it is essential to shed light on the driving forces that determine the utilization of equity crowdfunding. We find six publications in this area.

Some studies (Belleflamme et al. 2014; Blaseg and Koetter 2015; Brown et al. 2015; Miglo 2016) analyze the rationales of capital-seeking entrepreneurs for choosing equity instead of reward-based crowdfunding as a funding source. Belleflamme et al. (2014), as one of the first studies on equity crowdfunding, and Miglo (2016) build a theoretical model to determine the conditions under which entrepreneurs prefer equity instead of reward-based crowdfunding. The results suggest that entrepreneurs tend to choose equity crowdfunding if a more substantial amount of capital is needed. In addition, Belleflamme et al. (2014) show that equity crowdfunding is preferred if information asymmetries are high, whereas Miglo (2016) suggests that the presence of information asymmetries lead to a favored use of reward-based crowdfunding. Beyond that, Miglo (2016) shows that entrepreneurs prefer crowdfunding to traditional forms of finance when the funding goal is rather small (reward-based) or entrepreneurs want to trigger and grow potential future demand of their product or service (equity-based). Blaseg and Koetter (2015) empirically examine the effects of external shocks on banks (e.g., bank instability, credit crunch) on the probability of choosing equity crowdfunding rather than bank loans. Based on regressions, the authors indicate that bank-related ventures affected by external shocks tend to use equity crowdfunding when seeking external capital. Brown et al. (2015) focus on the drivers of UK-based entrepreneurs to engage in equity crowdfunding. By conducting interviews with 42 successful equity crowdfunded ventures, the authors find that the adoption of equity crowdfunding is influenced by factors like a perceived lack of funding alternatives, funding speed, increasing attention by potential customers, the maximum level of autonomy, media presence, and feedback received. Other studies (Brem et al. 2014; Dorfleitner et al. 2014) empirically discuss the suitability of equity crowdfunding for capital-seeking ventures. Based on six interviews with German cooperatives, Brem et al. (2014) show that equity crowdfunding could have an increased potential for financing cooperatives. In addition, Dorfleitner et al. (2014) argue that equity crowdfunding seems to be most suitable for rather small ventures in Germany.

3.3.2 Determinants of campaign success

Equity crowdfunding has a significant impact on early-stage venture funding in various countries (Massolution 2015; Vulkan et al. 2016). To extend the significance, it is essential to identify potential factors that influence the performance of equity crowdfunding campaigns. For facilitating campaign success, capital-seeking entrepreneurs need to reduce information asymmetries (Vismara 2018c). Therefore, it is crucial that entrepreneurs find ways to signal quality and credibility to potential investors. We identified 19 publications that empirically examine the effectiveness of signals, predominantly based on signaling-theory, for illustrating credibility and high quality. Ahlers et al. (2015) provide the first study exploring the significance of signals in equity crowdfunding. Based on 104 offerings from the Australian platform ASSOB, Ahlers et al. (2015) investigate what information disclosed by entrepreneurs can influence funding performance. The authors indicate that information about risk factors (e.g., financial projections), planned exit strategy, human capital (e.g., size and educational degree of the management team), and the amount of equity retained can be interpreted as quality signals that significantly increase campaign success, whereas social (e.g., alliances) and intellectual capital (e.g., patents) have no significant effect on funding success. In a UK-based study of 271 equity crowdfunded ventures, Vismara (2016) empirically confirms that the amount of equity retained is linked to campaign success. Additionally, Vismara (2016) highlights that ventures with a more extensive social network have a higher probability of funding success. In contrast to Ahlers et al. (2015), Vismara (2016) shows that disclosing information about planned exit strategies has no significant effect. Based on a cross-platform analysis of four European equity crowdfunding platforms, Nitani and Riding (2017) also confirm the relevance of an extensive social network, the amount of equity retained, entrepreneur’s management experience, and education as well as financial information on campaign success. In addition, the authors highlight that more compelling disclosure requirements and risk warnings are not significant for the success of campaigns.

In a Chinese equity crowdfunding context, Li et al. (2016) empirically confirm the relevance of human capital (team size and experience) by analyzing 49 successful equity crowdfunding campaigns from Dajiatou. In addition, based on an elaboration likelihood model and regressions, Li et al. (2016) emphasize the importance of project updates and information about lead investors as success drivers. Similarly, Block et al. (2018b) support the positive effect of updates by examining the content of updates, posted by 71 German equity crowdfunded ventures. Based on a mixed methods approach, the authors first use a qualitative coding system to categorize the updates according to their content. Subsequently, by using regression analysis, the authors examine the content of updates and find that updates containing information about new funding sources, business development processes, and marketing campaigns influence funding success in particular. In contrast, updates informing investors about the team and product development have no significant effect. Based on the coding system developed by Block et al. (2018b), Dorfleitner et al. (2017) analyze the communication behavior of start-ups during and after the campaign. By analyzing 168 campaigns of German ventures (97 update data set, 71 investor data set), the authors provide evidence that entrepreneurs’ use updates strategically to increase investments. More precisely, entrepreneurs post updates with linguistic styles that enhance group identity and cohesion as well as updates containing information about business development. In addition, the authors show that ventures post more updates during than after the campaign.

Concerning human capital signals, Piva and Rossi-Lamastra (2017) validate the influence of entrepreneurs’ education and experiences on campaign success. Based on 129 campaigns listed on the Italian platform SiamoSoci, the authors illustrated the significant impact of an entrepreneur’s business education (i.e., management and economics) and previous entrepreneurial experiences on campaign success. In a US context, Giga (2017) also supports the importance of human capital signals on campaign performance. Based on 1487 campaigns listed on EquityNet, the author examines the relative significance of human capital signals compared to business characteristics. In line with Piva and Rossi-Lamastra (2017), the results also illustrate a positive relationship of previous entrepreneurial experiences, as a dimension of management experience, to capital raising. In contrast, business characteristics have no significant impact on campaign performance. By conducting nine interviews with German start-ups and platforms, Angerer et al. (2017) confirm the relevance of team quality and an active communication strategy as drivers for campaign success. In addition, Angerer et al. (2017) highlight that a comprehensive pre-campaign preparation including the development of a roadmap (marketing strategy) and the mobilizing of friends and family as pioneer investors is crucial for a successful campaign. Some studies (Bapna 2017; Ralcheva and Roosenboom 2016) empirically analyze the effect of signals from third parties on overall funding success. By employing a randomized field experiment, Bapna (2017) examines the individual and combined causal effects of various signals that reduce uncertainty (e.g., of product certification, cooperation with well-known organizations, and the behavior of preceding investors) on campaign success. The results indicate that only a combination of the signals product certification and prominent affiliate or product certification and social proof affect funding success significantly. Ralcheva and Roosenboom (2016) introduce certification theory in equity crowdfunding and explore the effect of third-party signals on campaign success by analyzing 541 campaigns listed on Crowdcube. Based on regressions, the authors suggest that third-party signals like investors as partners, project awards, grants, and intellectual property rights have a positive impact on overall campaign success.

A few studies (Vulkan et al. 2016; Lukkarinen et al. 2016) focus on the effect of specific campaign characteristics on funding performance. Vulkan et al. (2016) analyze 636 ventures listed on the UK platform Seedrs. Based on regressions, the authors show that the amount of capital received in the first week, the largest single investment, and a large number of investors have a positive effect on overall funding success. Only a relatively high stated funding goal is negatively associated with campaign success. In the Finnish context, Lukkarinen et al. (2016) support the relevance of various campaign characteristics. By analyzing 60 campaigns listed on Invesdor, the authors show that investment criteria traditionally used by VC and BA are not relevant in equity crowdfunding. Instead, (crowd-) investors seem to base investment decisions on easily observable features like the previous funding amount collected from entrepreneurs’ private networks, social media networks, minimum investment amount, campaign duration, and a B2C orientation of ventures. Feola et al. (2017) explore the effect of a social orientation of ventures on campaign success. Based on a case study of the Italian social venture Paulownia Social Project s.l.r, the authors show that equity crowdfunding can meet the financing needs of social-oriented ventures. In their research in progress paper, Nevin et al. (2017) explore how the conveyance of a ventures’ social identity influence campaign performance. Based on social identity theory, Nevin et al. (2017) developed a theoretical model of how different campaign characteristics (e.g., communication, social media usage, etc.) influence the average investment size of ventures. However, their empirical model has not yet been tested.

With regard to post campaign success factors, Di Pietro et al. (2017) analyze the relation of non-monetary inputs offered by the crowd on ventures later performance. Based on interviews with 60 successfully European equity crowdfunded ventures, the authors show that equity crowdfunding investors can contribute to ventures later performance (i.e., survival rates, fundraising achievements) by providing product and market knowledge as well as network ties with relevant stakeholders (e.g., investors, potential employees, etc.). Especially less experienced entrepreneurs, in terms of industry and management experience, are more interested in involving the crowd as a source of non-monetary inputs. Hornuf and Schmitt (2017) examine the determinants of follow-up funding and firm survival of 426 German and UK firms that successfully obtained capital through equity crowdfunding. By analyzing 505 equity crowdfunding campaigns,Footnote 5 the authors illustrate significant differences between German and UK equity crowdfunded firms. In contrast to UK ventures, German ventures have a higher likelihood of obtaining subsequent financing from BAs or VCs. By including a temporal component to the analysis, German ventures have a 50% probability of receiving additional capital through BAs/VCs 36 month after a successful campaign, whereas UK firms only have a 20% likelihood. However, with regard to firm survival, the authors show that UK firms have a lower chance of failure (5%) 36 month after the campaign, while the probability of firm failure of German ventures is 24%. Referring to determinants of follow-up funding and firm survival, the authors indicate that a higher number of TMT members, a successful second equity crowdfunding campaign, and the presence of VC investors increases the probability of follow-up funding. In addition, a successful subsequent equity crowdfunding campaign decreases the chance of firm failure.

Concerning the innovation level of ventures, one study (Le Pendeven 2016) explores the impact of ventures innovation degree in three dimensions (market, technology, and business model) on overall funding success. By analyzing 39 ventures from the French platform Anaxogo, the results indicate that more innovative ventures (technology, ventures with patents) raise higher amounts of capital and account for a higher number of investors than less innovative ones.

Concerning institutional factors/institutions, one study (Kshetri 2015) investigates equity crowdfunding from an institutional perspective. By adopting institutional theory, Kshetri (2015) examines how institutions affect funding success. The author argues that formal (regulatory framework) and informal (e.g., trade associations) institutions support the establishment of equity crowdfunding campaigns and, therefore, positively affects the campaign outcome.

3.3.3 Gender issues

It is widely recognized that female entrepreneurship plays a significant role concerning the economic development in various countries (Minniti et al. 2005; Langowitz and Minniti 2007). However, some studies show that women are less involved in entrepreneurial activities than men (Delmar and Davidsson 2000; Minniti et al. 2005; Langowitz and Minniti 2007). We identify one study (McGuire 2016) that empirically emphasizes the potential role of equity crowdfunding in minimizing the gender gap in entrepreneurship. By analyzing 15.605 companies from CrunchBase, McGuire (2016) argues that the implementation of the US JOBS Act significantly influences female entrepreneurs seeking external capital because it improves the chances for women to receive external funding.

3.3.4 Discussion and future research activities for the entrepreneur perspective

Several themes emerge for equity crowdfunding researchers interested in issues surrounding the entrepreneur perspective. In sum, we identify three themes, while the main emphasis of scholars lies on the investigation of drivers that facilitate campaign success. Thereby, campaign success is predominantly defined as the achievement of the funding target and the number of investors at the end of a campaign. The most relevant determinants for campaign success (Table 7) are similar to those used in more professional equity investment contexts, e.g., Venture Capital and Business Angel financing.

The majority of subsequent studies confirm the results of previous studies regarding the significance of signals used by entrepreneurs, i.e., human capital, third party, and posted updates. However, we find contradictory evidence concerning the impact of intellectual property rights on campaign success. Whereas Ralcheva and Roosenboom (2016) indicate that ventures holding intellectual property rights (e.g., patents, trademarks, copyrights) are more likely to succeed in equity crowdfunding campaigns, some studies (Ahlers et al. 2015; Vismara 2018b) imply that intellectual capital is not per se a significant factor for predicting campaign success. Rather, intellectual capital seems to be an important factor increasing the probability of follow-up financing (Signori and Vismara 2018). These contradicting outcomes may occur due to various reasons. First of all, the sample size of Ralcheva and Roosenboom (2016) is nearly five times larger compared to Ahlers et al. (2015) and Vismara (2016), which provides more room for the significance of intellectual capital. Second, the studies differ regarding the operationalization of the intellectual capital variable. Whereas Ahlers et al. (2015) and Vismara (2016) use patents as the most common predictor of intellectual capital, Ralcheva and Roosenboom (2016) summarize patents, trademarks, and copyrights as intellectual property rights. Another possible explanation for these differences might be that the individual effect of intellectual property rights is not strong enough to convince investors. Gompers and Lerner (Gompers and Lerner 2001) argue that intellectual capital may only become significant when combined with signals of feasibility, i.e., processes or technologies that intellectual property rights involved. As such a signal, Audretsch et al. (2012) analyze the individual and combined effect of a developed prototype and intellectual capital (i.e., patents) on obtaining capital. The results suggest that ventures with patents and a developed prototype are more likely to obtain capital from investors. Since the majority of crowdfunded ventures are IT ventures (Bapna 2017), a similar study in an equity crowdfunding context might provide clarity regarding the role of intellectual property rights for campaign success. In addition, such research activities will enhance our so far limited knowledge about the complementarity of signals in equity crowdfunding. More precisely, do intellectual property rights (e.g., patents) only become significant in combination with a developed prototype? Which other types of signals are likely to complement each other? A further promising research area could be to differentiate the effect of specific signals according to campaign stages. Since Vismara (2016) indicates that specific quality signals (i.e., patents) are significant for early investors, it might be of scholarly interest to analyze if dynamic signals during the campaign (e.g., updates, funding speed, amount of capital received, number of investors) mitigate the significance of pre-campaign signals induced by entrepreneurs. For example, do dynamic during campaign signals (e.g., updates, funding speed and amount, number of investors) mitigate the significance of pre-campaign signals? Another potential research area referring to signals used in equity crowdfunding could be the relation of a venture’s industry classification and quality signals used. None of the studies in our sample compiles a comparative analysis of ventures industry characteristics and signaling strategies. Hence, we encourage interested scholars to investigate if the significance of signals used differs according to the specific industry classification of the ventures. Essentially, do technology ventures in equity crowdfunding use the same signals as non-technology ones? Is the significance of signals used by ventures across all industry sectors the same? Since some studies (Block et al. 2018b; Li et al. 2016; Dorfleitner et al. 2017) provide insights that communication strategies affect funding performance, we see great potential in analyzing how the language used in updates and project proposals relates to campaign success. More specifically, how does entrepreneurial rhetoric influence crowd participation, thus facilitating campaign success? The studies of Lounsbury and Glynn (2001), Martens et al. (2007), and Allison et al. (2013, 2015) can serve as inspiration for interested scholars. Lounsbury and Glynn (2001) analyze the effect of entrepreneurial storytelling on forming ventures’ identity, whereas Martens et al. (2007) investigate the influence of entrepreneurial narratives to secure external venture capital. By applying warm-glow theoryFootnote 6 in the context of microlending investments, Allison et al. (2013) find that credit applications using a language style that creates warm-glow effects have a positive effect on funding performance. In a follow-up study, Allison et al. (2015) show that narratives framed as an opportunity to help other instead of a business opportunity are more likely to attract supporters.

With regard to the post-campaign performance of ventures, we see great potential to complement the work of Di Pietro et al. (2017) and Hornuf and Schmitt (2017). Since Di Pietro et al. (2017) indicate the potential value of non-monetary benefits provided by the crowd regarding product and market knowledge and network ties, it might be worth investigating what other additional benefits are provided by the crowd and how do these relate to a ventures’ later performance. More precisely, does equity crowdfunding act as a knowledge sharing tool between investors and entrepreneurs? In what other ways are (crowd-) investors involved in the day-to-day business of ventures? Hornuf and Schmitt (2017) indicate that German equity crowdfunding ventures have lower survival rates compared to the UK-based ventures. Due to this circumstance, we strongly support the notion of Vismara (2018c) to analyze if the signals which are significant for campaign success are also predictors to overall venture performance after the campaign. More precisely, does a successful equity crowdfunding campaign positively influence post-campaign performance indicators (growth of sales and profit, subsequent financing, innovation degree)?

Further fruitful research streams could also derive from empirical studies of other crowdfunding contexts. In reward-based crowdfunding contexts, for instance, some studies show (e.g., Thürridl and Kamleitner 2016; Hobbs et al. 2016) the influence of various rewards as strategic assets on campaign success. Since the UK platform, Crowdcube offers entrepreneurs additionally the possibility to include rewards in campaigns; it might be of scholarly interest to analyze how these rewards can facilitate campaign success (individual funding amounts?). More specific, to what extent can additional rewards in equity crowdfunding campaigns influence campaign success? What types of rewards (involving vs. haptic rewards) seem most promising for overall funding success?

As claimed by Welter (2012), trust is essential for starting a new venture. However, as no single studies within the entrepreneur perspective investigate trust-building opportunities of entrepreneurs, we see a strong need to examine this subject. In equity crowdfunding, investors rely solely on the integrity of information disclosed by entrepreneurs. Consequently, entrepreneurs need to find ways to be trustworthy to increase the probability of a successful campaign. Therefore, we suggest research on how entrepreneurs can build and maintain trust in equity crowdfunding? Exemplary, Ba et al. (2003)and Bammens and Collewaert (2014) provide insights into trust-building opportunities for e-businesses and online markets, thus serving as an orientation for interested scholars.

Knowledge about female entrepreneurial activities is somewhat limited in equity crowdfunding. However, by investigating the supply-side of female entrepreneurs, Vismara (2016) indicates that women-led ventures receive less capital compared to male-led ones. Future research could analyze the rationales for this circumstance by highlighting possible differences between male- and female-led firms. On this basis, future studies can evaluate opportunities to increase the participation of women in equity crowdfunding, both as investors and entrepreneurs, thus helping to reduce the gender gap in entrepreneurship.

3.4 Institutional perspective

The institutional perspective category comprises publications examining the legal conditions for equity crowdfunding in different countries. In total, we identified 38 publications (Table 8) applying a legal lens to equity crowdfunding, addressing three themes: impact of laws, comparison of legal conditions, contracting practices.

3.4.1 Impact of laws

The majority of contributions (26 publications) investigate the possible impact of laws on stakeholders in various jurisdictions. With regard to the US JOBS Act, Whitbeck (2012) discusses the requirements for participating parties and highlights the potential positive impact of these regulations on capital formation and investor protection. Similarly, by reviewing the JOBS Act, Jeng (2012) mirrors the positive potential impact on capital formation and investor protection. Malach et al. (2015) analyze 452 stakeholder comments (issuers, investors, intermediaries) regarding the rules proposed by the SEC on equity crowdfunding to examine the main issues raised by affected parties. Their analysis results in 16 issue categories. Among these categories, the most important ones for stakeholders are investor and issuer limits, due diligence/disclosure, and financial reporting. The results suggest that stakeholders are aware of the importance and thoroughness of financial disclosure for investor protection and capital formation. However, stakeholders concerns about potential fraud in equity crowdfunding seem only to be minor.

In contrast, some studies provide a critical analysis of the JOBS Act. Urien and Groshoff (2013), Groshoff et al. (2014), Groshoff (2016), Hogan (2014), McAllister Shepro (2014), and Oranburg (2015) highlight various shortcomings (fraud potential, insufficient capital limit, increased costs of compliance) of the Act. The authors suggest amendments (e.g., higher capital limits, reduced compliance costs for small ventures, increased investor protection) to facilitate equity crowdfunding as a viable funding source for new ventures. In addition, Oranburg (2015) highlights the need for an increased capital-raising limit, between 1 and 5 million US Dollars so that ventures can use equity crowdfunding as a bridge funding opportunity. Dorff (2014) provides another critical analysis of the JOBS Act. The author argues that despite the disclosure requirements and investor protection mechanisms, equity crowdfunding should exclude unaccredited investors, because of the risk of losing money. Dorff (2014) concludes that ventures which can raise capital through professional investors (BA, VC) will not use equity crowdfunding. Thus equity crowdfunding will be likely used by rather unpromising ventures. Chen (2017) shows that current regulations in the JOBS Act (i.e., Title III) are unsuitable for resolving the “lemons problem” (Akerlof 1970) in equity crowdfunding. Based on a theoretical model, enhanced by an empirical analysis of 461 crowdfunding filings of firms and 133 successful campaigns, Chen (2017) provides evidence that the Title III equity crowdfunding market is not suitable for the funding of high-quality firms regarding revenues and profitability. Chen (2017) shows that the Title III market predominantly consists of small low profitable ventures from sectors associated with lower information asymmetries, e.g., food, beverages, and restaurants.

Due to the delayed implementation of the JOBS Act, a few studies (Mitchell 2015; Pierce-Wright 2016; de la Vina and Black 2016) compare intrastate crowdfunding laws relying on SEC rule 504 to the JOBS Act. Mitchell (2015) and Pierce-Wright (2016) suggest that, due to high registration requirements and insufficient investor protection mechanisms, individual intrastate laws are inappropriate to meet the capital-raising needs of ventures. In addition, Pierce-Wright (2016) proposes amendments (e.g., scaled per-investor limits, tiered disclosure requirements) to facilitate investor protection. In contrast, de la Vina and Black (2016) show that intrastate regulations are more appropriate in facilitating equity crowdfunding due to the allowance of more small investors to participate and a higher number of total investments. With regard to German equity crowdfunding regulations, Klöhn et al. (2016a) explore the impact of the German Small Investor Protection Act. The authors highlight the need to improve investor protection further and propose investor education and communication as viable mechanisms. In a Canadian context, three studies analyze the impact of regulations on capital formation and investor protection. Cumming and Johan (2013) empirically explore how market participants would design equity crowdfunding regulations. Based on 144 surveys from various stakeholders, the authors show that entrepreneurs prefer less restriction referring to the amount of capital raised in each year. More precisely, portals prefer fewer disclosure requirements and tradeable shares, and investors favor greater restrictions, e.g., greater portal due diligence and limits on amounts entrepreneurs can raise to mitigate risks. Figliomeni (2014) and Anand (2014) suggest that the regulatory framework proposed by the Ontario Securities Commission will benefit capital formation and investor protection. In addition, based on a case study about the movie “age of the stupid,” Figliomeni (2014) shows the benefits of equity crowdfunding for the entertainment/cultural sector. Martins Pereira (2017) analyses the Portuguese regulatory framework on investor protection and capital formation. The author suggests that further improvements are necessary to ensure the long-term success of equity crowdfunding. More precisely, Martins Pereira (2017) recommends additional monitoring responsibilities of platforms and the implementation of an investors’ discussion board, to reduce information asymmetries. In a Taiwanese context, Tsai (2015, 2016) examines the impact of Taiwanese regulations that have its origin in the US JOBS Act. Based on interviews with equity crowdfunding stakeholders, Tsai (2015, 2016) shows that the implementation of regulations based on the US model would lead to increased investor protection, which adversely affects capital formation. With regard to Singaporean regulations, Ying (2015) analyses the impact of legal regulations formulated by the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS). The author concludes that the MAS approach to open equity crowdfunding only for professional investors combined with high disclosure requirements will decrease the potential of equity crowdfunding. For facilitating equity crowdfunding in Singapore, Ying (2015) proposes new regulations on prospectus requirement and investor protection. By analyzing the potential impact of regulatory conditions in India, Majumdar (2015) mirrors the result of Ying (2015). Ancev (2015) explores equity crowdfunding regulations in Australia. The author states that existing Australian securities and financial service laws are inappropriate to balance the development of equity crowdfunding and investor protection effectively. For facilitating the initial development and gain further information to determine an optimal framework in the long term, the author proposes a decentered experimental regulation approach predominantly based on platform activities to establish and control specific codes of conduct for equity crowdfunding participants. More precisely, Ancev (2015) suggests limiting the annual investment amount of investors and imposing investor education mechanisms as tools for investor protection. In contrast to Ancev (2015), Nehme (2017) suggests that a limit on investment amounts could hinder the development of equity crowdfunding in Australia. Instead, the author suggests a more active role of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) in monitoring and controlling ventures to facilitate trust of investors in equity crowdfunding and enhance investor protection. In addition, Nehme (2017) recommends a step-by-step capital raising model where capital raising thresholds (e.g., every AUD$ 100.000) are linked to specific milestones. Only when these milestones are achieved, the venture has the justification to raise more money for next milestones. Murray (2015) and Keeper (2016) focus on laws regulating equity crowdfunding in New Zealand. Murray (2015) shows that New Zealand ventures face fewer disclosure requirements but are limited in opportunities for secondary trading of shares, whereas Keeper (2016) concludes that current regulations are not able to appropriately balance investor protection and capital formation.

3.4.2 Comparison of legal conditions

Nine studies focus on a comparison of legal conditions in different countries. Klöhn and Hornuf (2012) compare and discuss German and US equity crowdfunding regulations and highlight differences between them. Another study (Wilson and Testoni 2014) also illustrates the differences and similarities in, by comparing the US and European regulations. Similarly, Hornuf and Schwienbacher (2017) compare and examine the impact of equity crowdfunding regulations in seven European countries. Based on a mathematical model in which a small firm considers raising capital either from professional investors (BA and VC) or equity crowdfunding, the authors derive three implications: greater investor protection has a negative effect on capital formation; the benefits of using equity crowdfunding are lower in the presence of a well-developed VC and BA market; and equity crowdfunding needs tailored regulations to reach its fullest potential. Gabison (2014) compares different regulations in Europe, the USA, and Australia and highlights that each country focuses on different actors (entrepreneurs, investors, platforms). US and UK regulations concentrate more on investor protection, whereas the Italian CONSOB focuses on entrepreneurs and platforms. The same applies to French regulations. To show the positive impact of implemented UK regulations for capital seeking ventures, the author analyzes 68 successful campaigns from Crowdcube. Gabison (2014) illustrates that the number of investors and the amount raised in equity crowdfunding increased since the implementation of UK regulations. Pekmezovic and Walker (2015) compare legal regulations in various OECD countries, including the UK, USA, Germany, Italy, and New Zealand. The authors point out that policy makers should focus on managing the tradeoff between disclosure requirements and investor protection. Ho (2016) compares US and UK regulations on equity crowdfunding and evaluates their suitability exemplary for Hong Kong. The author suggests following the more cautious US approach to prevent potential investors through imposing investment limits based on the income. Similarly, due to the absence of a specified equity crowdfunding regulation in China, Duoqi and Mingyu (2017) analyze the suitability of Chinas legal framework of private equity investments for equity crowdfunding. The author suggests that these regulations are inappropriate for equity crowdfunding and highlight the need to follow the equity crowdfunding regulations of other countries, e.g., US and UK regulations. In addition, Lin (2017) recommends increasing responsibilities of Chinese platforms concerning due diligence or background checks of entrepreneurs to verify the risks of the investment and enhance investor protection.

Lombardi et al. (2016) compare Italian regulatory conditions to other European regulations and the JOBS Act and illustrate the differences and similarities of these frameworks. Similarly, Đurđenić (2017) illustrates similarities between European (UK, France, Germany, Italy) and US regulations to current Croatian laws.

3.4.3 Contracting practices

Three studies in our sample examine contracting practices in the USA (Wroldsen 2016), China (Li 2016), and Germany (Klöhn et al. 2016b). Wroldsen (2016) analyzes the contractual terms of the first 39 campaigns since the legalization of equity crowdfunding. The author argues that these contracts are similar to those used by professional investors (VC) but more standardized and simplified in their design. The author explains that due to this simplicity, these contracts are not adequate for investor protection. Li (2016) explores the contractual agreements of 53 campaigns from the Chinese platform Renrentou and shows that the primary purpose of contracts is to secure the right of investors to get a monetary return. Based on a content analysis of deals from 255 campaigns from German platforms, Klöhn et al. (2016b) highlight characteristics of equity crowdfunding contracts. The authors reveal that contracts include a minimum duration between 6 and 8 years, offer investors a fixed interest payment and exit participation, contain no veto rights, and the common contract type is a subordinated profit-participating loan.

3.4.4 Discussion and future research avenues for the institutional perspective

Most studies within this perspective investigate the influence of implemented legal frameworks for regulating equity crowdfunding on participating stakeholders. Since most legal frameworks are relatively new (e.g., the German Small Investor Protection Act, the US JOBS Act), only one study (Gabison 2014) examines the actual impact of UK regulations. To shed light on the effect of implemented rules on equity crowdfunding in other countries, we want to encourage interested scholars to analyze to what extent did implemented legal regulations promote funding for small businesses? In line with this, some studies (e.g., Hornuf and Schwienbacher 2017) reveal country-specific differences according to the regulation of equity crowdfunding participants. Therefore, it might be of scholarly interest to investigate whether country-specific characteristics lead to differences in funding performance between countries. More specific, to what extent do country-specific attributes in regulations affect equity crowdfunding performance?

Since governments and institutions play a central role in developing an entrepreneur-friendly environment, the so-called entrepreneurial ecosystems (Isenberg 2010; Hechavarria and Ingram 2014), it might be of scholarly interest to examine how governments and policies can shape such an environment. More specifically, how can government/policy interventions promote an equity crowdfunding ecosystem for fostering and sustaining venturing? How can cooperation’s between the state, universities, incubators, and equity crowdfunding platforms create a crowdfunding friendly entrepreneurial ecosystem? So far, evidence about the interplay of various financing forms and equity crowdfunding as well as the effect of successful campaigns on scaling-up subsequent finance is rather scarce. As one exemption, Cumming et al. (2018a) analyze the interaction of numerous forms of finance, including equity crowdfunding, and highlight possible positive and negative externalities on scaling-up. Cumming et al. (2018a) highlight that one of the significant barriers that can impede the attraction of subsequent investors is ownership dilution (Signori and Vismara 2018). Therefore, in line with Cumming et al. (2018a), future studies could analyze how policy interventions need to be formed to facilitate the scaling-up of equity crowdfunded ventures? However, government and policy approaches need to develop over time. To guarantee a proper and a mutually beneficial functioning of the equity crowdfunding market, government interventions (e.g., legal improvements) need to adjust to the continuous changes in equity crowdfunding.

3.5 Investor perspective

Within equity crowdfunding, investors play a crucial role. Capital-seeking entrepreneurs rely solely on the investment behavior of a multitude of investors. Therefore, it is of great importance to gain a deeper understanding of the investors’ behavior in equity crowdfunding. In sum, we identify 21 articles (Table 9) that contribute to a better understanding of investor decision making. Our review reveals five thematic areas within this cluster: motives for investing, investment evaluation, investor type, investment dynamics, and return on investment.

3.5.1 Motives for investing

Exploring (crowd-) investors’ motives is one significant step to foster a detailed understanding of investor behavior in an equity crowdfunding context. We identify four publications that analyze the motivational structure of investors in equity crowdfunding. Cholakova and Clarysse (2015) provide the first evidence regarding the motivation of equity crowdfunding investors. Grounded on self-determination theory and cognitive evaluation theory, Cholakova and Clarysse (2015) examine the interplay between financial and non-financial motives in equity and reward-based crowdfunding. By conducting a quasi-experiment including 155 participants from Symbid, the authors analyze how the existence of both campaign-types for the same project influences the decision to invest or to pledge. The results suggest that financial motives (expected reward or return) play a significant role for both crowdfunding types (expected reward or return), whereas non-financial motives (e.g., helping others, support ideas) only have a small impact on the decision to invest. Similarly, Moysidou and Spaeth (2016) confirm the results of Cholakova and Clarysse (2015). Based on consumption value theory, Moysidou and Spaeth (2016) conduct a factorial survey of 309 crowdfunding supporters. The authors illustrate that decision-making differs across the various forms of crowdfunding and highlight the significance of financial, respectively rational motives for investors in equity-based crowdfunding. In contrast, Bretschneider and Leimeister (2017) emphasize the importance of various non-financial motives in equity crowdfunding. Based on 300 surveys, the authors show that in addition to the (financial) reward motive, other motives like receiving recognition from others (recognition motives), the liking of specific ventures (liking motive), to be well regarded by others (image motive), and influencing the fruition of specific projects (lobbying motivation) are relevant for equity crowdfunding investors. Daskalakis and Yue (2017) in part support the results of Bretschneider and Leimeister (2017). Based on 317 surveys of European fundersFootnote 7, the authors show that non-financial motives, i.e., interest and excitement, are the highest rated drivers of respondents in equity crowdfunding.

3.5.2 Investment evaluation

To advance our understanding of investor behavior in equity crowdfunding, it is of great importance to uncover the factors that influence the evaluation process of (crowd-) investors. A stream of publications examines the decision-making process of equity crowdfunding investors, predominantly in the German context.

Based on a survey of 221 German students, Brem and Wassong (2014) find that primarily rational factors (e.g., management competencies, venture stage, USP, perceived return on investment) significantly affect the investor’s decision-making process. With regard to the flow of information in equity crowdfunding, Moritz et al. (2015) investigate how investor communication affects the decision-making process. Based on 17 interviews with various market participants (investors, platforms, entrepreneurs, experts), the results suggest that third-party communication (e.g., other investors, experienced investors, experts, and customers) are especially valued as quality signals and influence investors’ evaluation process. Günther et al. (2015) focus on the due diligence of crowd investors and analyze whether the amount invested correlates with the thoroughness of the evaluation process. By evaluating 136 surveys of investors listed on Seedmatch, the results suggest that (crowd-) investors assess business ideas with regard to their specific expertise, experience, and effort spent on the due diligence process. In addition, Günther et al. (2015) show that a higher degree of industry and financial expertise of equity crowdfunding investors positively affects the amount invested. Zunino et al. (2017) examine the consequence of failure experience by entrepreneurs, as a negative quality signal, on investor decision making. Based on an online experiment with 328 participants, the authors compare the individual effect of past entrepreneurial failure to a combination of past entrepreneurial failure and a quality signal on the probability to invest. The results suggest that compared to past entrepreneurial success, investors discriminate entrepreneurs who have experienced past entrepreneurial failure. However, this effect is diminished by a provision of failure experience combined with a positive quality signal of entrepreneurial skill.

Hornuf and Neuenkirch (2017) analyze 44 campaigns from Innovestment to investigate the pricing of cash flow rights. In contrast to other equity crowdfunding platforms, “Innovestment runs a multiunit sealed bid second price auction where backers can specify the price they are willing to pay” (Hornuf and Neuenkirch 2017, p. 807). As a result, investors have the opportunity to outbid each other for specific shares. By analyzing this unique auction mechanism, Hornuf and Neuenkirch (2017) indicate that campaign characteristics (e.g., funding goal, initial price), herding momentums, a ventures funding progress, and stock market volatility influence the pricing of cash flow rights. By examining fundraiser-related, project-related, and platform-related characteristics on a Chinese equity crowdfunding platform, Kang et al. (2016) analyze the potential impact of trust between the entrepreneurs and investors on investment decisions. The authors show that various project-related (e.g., network externality, perceived informativeness), platform-related (e.g., perceived accreditation, third-party seal), and fundraiser-related factors (e.g., social interaction) facilitate calculus-based (on individual knowledge) and relationship (build through social exchange) trustFootnote 8 and, therefore, affect the decision of individual equity crowdfunding investors to invest.

3.5.3 Investor type

The composition of the crowd is another crucial aspect for advancing a common understanding of investor behavior in equity crowdfunding. In sum, we identify seven publications that analyze investor behavior according to different investor types in equity crowdfunding.