Abstract

The current rise in research on entrepreneurial ecosystems notes that many questions are still unanswered. We, therefore, theorize about a unique paradox for entrepreneurs trying to establish legitimacy for their new ventures within and beyond an entrepreneurial ecosystem; that is, when pursuing opportunities with high levels of technological or market newness, entrepreneurs confront a significant challenge in legitimizing their venture within an entrepreneurial ecosystem, while those entrepreneurs pursuing ventures using existing technologies or pursuing existing markets have a much easier path to garnering legitimacy within that ecosystem. However, the diffusion of that legitimacy beyond the ecosystem will be wider and more far-reaching for those pursuing the newer elements compared to those using existing technologies or pursuing existing markets, thus, creating a paradox of venture legitimation. Prior research outlines approaches for new venture legitimacy but it is unclear when these approaches should be applied within and beyond an entrepreneurial ecosystem. To address this paradox, we integrate ideas from the entrepreneurship and innovation literature with insights from the legitimacy literature to describe how different types of venture newness employ different legitimation strategies which results in different levels of legitimacy diffusion beyond an ecosystem. We conclude with a discussion of our concepts and offer suggestions for future research efforts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Entrepreneurship is now regarded as the “pioneership” on the frontier of business (Kuratko 2017). However, scholars warn that a complete understanding of entrepreneurship can be elusive (Audretsch, Kuratko, & Link 2015). The impact of entrepreneurial activity is felt in all sectors and at all levels of society, especially as it relates to innovation, competitiveness, productivity, wealth generation, job creation, and formation of new industry (Morris et al. 2015). Newer entrepreneurial ventures—some of which did not exist 20 years ago—have collectively created millions of new jobs during the past decade, among many notable examples, consider Facebook, Twitter, Google, LinkedIn, and YouTube.

Amidst the energy and excitement of the entrepreneurial movement has been the rise of “entrepreneurial ecosystems” as coordinated attempts to establish environments that are conducive to the probabilities of success for new ventures following their launch. However, the rise of many ecosystem approaches has left many questions unanswered. As Stam (2015: 1763) so clearly pointed out, “Seductive though the entrepreneurial ecosystem concept is, there is much about it that is problematic, and the rush to employ the entrepreneurial ecosystem approach has run ahead of answering many fundamental conceptual, theoretical and empirical questions”.

What exactly is an entrepreneurial ecosystem? Stam (2015: 1764) defines an entrepreneurial ecosystem as “a set of interdependent actors and factors coordinated in such a way that they enable productive entrepreneurship.” He goes on to point out that these entrepreneurial ecosystems differ from other concepts (such as clusters, innovation systems, or industrial districts) “by the fact that the entrepreneur, rather than the enterprise, is the focal point. The entrepreneurial ecosystem approach thus begins with the entrepreneurial individual instead of the company, but also emphasizes the role of the entrepreneurship context (Stam: 1761)”.

If these entrepreneurial ecosystems are focused on creating environments conducive to the success of entrepreneurs and their new ventures, there still exists a challenge for these entrepreneurs to establish their credibility or legitimacy within and beyond that ecosystem for further advancement. The newness of entrepreneurial venture means that such ventures are initially not known and are usually poorly understood within an ecosystem, causing them to lack legitimacy with other individuals and organizations in an ecosystem. New ventures that lack legitimacy struggle to access much needed resources and support (Fisher, Kotha, & Lahiri 2016), are less likely to forge partnerships or strategic alliances with other organizations (Singh, Tucker, & House 1986), struggle to garner attention from the media (Pollack & Rindova 2003), and risk being overlooked for new contracts (Starr & MacMillan 1990). We, therefore, believe that exploring the strategies for an entrepreneur to legitimize his/her new venture is one conceptual element of importance for entrepreneurs within an entrepreneurial ecosystem. Prior research outlines possible approaches for fostering new venture legitimacy (e.g., Navis & Glynn 2011; Zimmerman & Zeitz 2002) but it is unclear when these approaches should be applied and what the implications of each approach are for the diffusion of new venture legitimacy within and beyond an entrepreneurial ecosystem. As entrepreneurs begin to execute on their new venture concepts, what specific strategies must be considered to effectively convey some legitimacy within the entrepreneurial ecosystem and more significantly in trying to move beyond the ecosystem for success? If entrepreneurs are the focus of these ecosystems, then the quest for attaining legitimacy of their ventures remains a missing link in the current studies.

To address this gap in the ecosystem literature, we proceed with our paper as follows. First, we explore the evasive domain of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Second, we then integrate ideas from three different literatures—entrepreneurship and innovation (to articulate a model for describing relative newness of entrepreneurial ventures), the legitimacy literature (relating different legitimation strategies), and the legitimacy diffusion literature (describing how different types of venture newness and different legitimation strategies result in different levels of legitimacy diffusion). Third, we highlight a key paradox for entrepreneurs within an entrepreneurial ecosystem. That is, when pursuing opportunities with high levels of technological or market newness, entrepreneurs confront a significant challenge in legitimizing their venture within an entrepreneurial ecosystem, while those entrepreneurs pursuing ventures using existing technologies or pursuing existing markets have a much easier path to garnering legitimacy within that ecosystem. However, the diffusion of that legitimacy beyond the ecosystem will be wider and more far-reaching for those pursuing the newer elements compared to those using existing technologies or pursuing existing markets, thus, creating a paradox of venture legitimation. Finally, we conclude with a discussion of our concepts and offer suggestions for future research efforts.

2 The elusive domain of entrepreneurial ecosystems

While fast becoming popular entities to promote entrepreneurship and foster new venture creation, entrepreneurial ecosystems are not clearly understood as to their exact meaning because they have been defined in a number of ways with differing elements purported to be important. Besides the definition provided by Stam (2015) that was mentioned earlier, Acs, Autio, and Szerb (2014: 479) define an entrepreneurial ecosystem as a “dynamic, institutionally embedded interaction between entrepreneurial attitudes, abilities, and aspirations, by individuals which drives the allocation of resources through the creation and operation of new ventures.” In a study of innovation networks, Rampersad, Quester, and Troshani (2010: 794) define those networks as “a loosely tied group of organizations that may comprise of members from government, university, and industry continuously collaborating to achieve common innovation goals.” Another popular way to define entrepreneurial ecosystems is based on location within communities or geographic regions (Nambisan & Baron 2013; Cohen 2006). An ecosystem in this context is defined as an agglomeration of interconnected individuals, entities, and regulatory bodies in a given geographic area (Isenberg 2010; Malecki 2011). Participants in an entrepreneurial ecosystem may include venture start-ups, banks, venture capitalists, incubators, accelerators, universities, professional service providers, and government agencies that support entrepreneurial activity. These varying perspectives motivated Stam (2015) to claim that there is no widely shared definition of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Isenberg (2010) also noted that there is no exact formula for creating an entrepreneurial ecosystem.

Another way to examine this phenomenon is through the elements that are considered most important to an entrepreneurial ecosystem. According to Isenberg (2011), these ecosystems consist of six general domains: a conducive culture, enabling policies and leadership, availability of appropriate finance, quality human capital, venture-friendly markets for products, and a range of institutional and infrastructural supports. Stam (2015) points to nine attributes: leadership, intermediaries, network density, government, talent, support services, engagement, companies, and capital. The World Economic Forum (2013) offers eight pillars for a successful entrepreneurial ecosystem: accessible markets, human capital/workforce, funding and finance, support systems/mentors, education and training, major universities as catalysts, and cultural support. Isenberg (2010) also developed nine principles important to the building of an ecosystem: not emulating Silicon Valley; shaping the ecosystem around local conditions; engaging the private sector from the start; stressing the roots of new ventures; emphasizing ambitious entrepreneurship; favoring high potentials; getting a big win; tackling cultural change head-on; and reforming legal, bureaucratic, and regulatory frameworks.

As can be seen, there are many factors offered that describe or prescribe what a successful entrepreneurial ecosystem entails.

The very idea of an ecosystem is predicated on the interdependence of these elements. Ecosystems, however, are inherently complex and little is known about how the different components interact with each other, making it challenging for new ventures seeking legitimacy within that ecosystem. Morris, Neumeyer, and Kuratko (2015) point out that there is a divergence of financial, social, and human capital resources that entrepreneurs have access to in different ecosystems. Comparing entrepreneurial ventures in Silicon Valley to those in Detroit, MI, there is quite a difference in which entrepreneurs confront more adverse conditions that limit their overall economic productivity and how that differs depending on the attributes of the venture they are creating. However, all types of new ventures confront the initial challenge of newness (Kuratko, Morris, & Schindehutte 2015) and the associated legitimacy hurdles that make it difficult for such ventures to access resources (Fisher et al. 2016). If, as promoted in Isenberg’s (2010) principles, emphasizing ambitious entrepreneurship, favoring high potentials, and getting a big win are important for those involved in building an entrepreneurial ecosystem, then the challenge of gaining legitimacy for an entrepreneur’s venture concept may be a key factor for success within and beyond an entrepreneurial ecosystem. Yet, because legitimacy barriers pertain to a venture’s newness, gaining legitimacy can be difficult when developing “new” (i.e., novel) concepts. Thus, the element of “newness” with ventures must be considered.

3 Newness and legitimacy

Newness, which is a hallmark of entrepreneurship, is recognized as both an asset and liability for new ventures (e.g., Navis & Glynn 2011). Entrepreneurial ventures derive competitive advantage over incumbent organizations by introducing novel technologies into the market and by developing innovative business models that give rise to new market categories (Christensen 1997; Schumpeter 1934). But, new ventures simultaneously confront a “liability of newness” (Stinchcombe 1965: 148) because their lack of performance history and consequent relative illegitimacy serves as a burden when they seek to acquire resources and enter into exchange relationships (Aldrich & Fiol 1994). New ventures therefore confront a paradoxical challenge in that a primary source of competitive advantage—technological or market newness—can also serve as a significant liability.

To overcome the liability of newness associated with a new venture, an entrepreneur can work to strategically establish organizational legitimacy by materially and symbolically manipulating elements of the venture (e.g., Delmar & Shane 2004; Martens et al. 2007; Navis & Glynn 2011; Sine, David, & Mitsuhashi 2007; Zimmerman & Zeitz 2002; Zott & Huy 2007). Legitimacy is derived from the perception that a new venture is “desirable, proper, or appropriate within some socially constructed system of norms, values, beliefs, and definitions” (Suchman 1995: 574). Prior literature has described the actions that entrepreneurs can take to strategically establish the legitimacy of a new venture. Strategies employed to establish organizational legitimacy include conforming to existing rules and norms, selection of favorable contexts, manipulation of cultural environments, and creation of new social contexts (Zimmerman & Zeitz 2002). There is however little guidance on when each of these strategies should be employed and how the different legitimation strategies impact the spread or diffusion of new venture legitimacy within and beyond an existing ecosystem.

Hence, we seek to conceptually address the following research questions in this paper: First, when are different legitimation strategies employed to legitimize a new venture within an ecosystem? Second, how do the legitimation strategies employed relate to the diffusion of new venture legitimacy beyond an existing entrepreneurial ecosystem?

To address these questions, we integrate ideas from three different literatures. First, because legitimation is related to newness, we utilize the entrepreneurship and innovation literatures (e.g., Benner & Tushman 2003) to articulate a model for describing relative newness of entrepreneurial ventures. Second, we build on ideas from the legitimacy literature (e.g., Zimmerman & Zeitz 2002) to relate venture newness to different legitimation strategies thereby explaining when and why different new venture legitimation strategies are employed. Third, we integrate ideas from the legitimacy diffusion literature (e.g., Johnson et al. 2006; Tost 2011) to describe how different types of venture newness and different legitimation strategies result in different rates and levels of legitimacy diffusion within and beyond an entrepreneurial ecosystem. The conceptual insights that emerge from the integration of these literatures highlight a key challenge for new ventures within an entrepreneurial ecosystem: entrepreneurs that pursue opportunities leveraging high levels of technological and market newness confront the greatest challenge in legitimizing their venture; but if they can clear a legitimacy threshold, their ventures will experience higher levels of legitimacy diffusion beyond their existing entrepreneurial ecosystem compared to ventures with lower levels of technological and market newness. Conversely, entrepreneurs that create new organizations embracing existing technology for an existing market category have an easier time legitimizing their venture within their ecosystem but the diffusion of new venture legitimacy beyond their existing ecosystem is more limited.

4 Innovation newness: Dimensions and level

Innovation is a driving force in the entrepreneurial process (Drucker 1985). While numerous definitions of innovation have surfaced in the research over the years (see Crossan & Apaydin 2010), we focus on innovation as the generation and implementation of new ideas, processes, products, or services (Garcia & Calantone 2002).

Schumpeter (1934) stressed the novelty or “newness” aspects of innovation such as new markets, new goods, new methods, and new structures. New market opportunities (Mueller et al. 2012) and new technological developments (Eckhardt & Shane 2011) produce significant entrepreneurial opportunities. Mueller et al. (2012) describe market pioneering as a particular form of entrepreneurial behavior whereby an organization proactively creates a new product-market arena that others have not recognized or actively sought to exploit. Organizations that consistently exhibit such market pioneering behaviors are able to capitalize on potential first-mover advantages (Garrett, Covin, & Slevin 2009; Covin, Slevin, & Heeley 2000). Eckhardt and Shane (2011) evaluated 201 industries over a 15-year period to validate that technological innovation is a key determinant of entrepreneurial opportunity. Past research therefore suggests that the newness of innovations can broadly be distinguished on two key dimensions: (1) technology newness and (2) market newness (Abernathy & Clark 1985 ; Benner & Tushman 2003; Zhou et al. 2005). Technology newness represents technological advances while market newness represents efforts to establish a new product-market arena to nurture new customers for a product or service (Benner & Tushman 2003; Zhou et al. 2005).

Innovations that are exploited within an entrepreneurial venture also vary in the level of newness that they encapsulate; the terms incremental and radical innovation have been used to describe differing levels of newness (Tushman & Anderson 1986; Henderson & Clark 1990). Incremental innovations are minor changes in existing technology, simple product improvements, or line extensions that fit within or minimally alter an existing market category. In contrast, radical innovations are novel advances that substantially shift a technological trajectory and/or establish the basis for a new market category (Zhou et al. 2005; Wind & Mahajan 1997).

4.1 Newness framework

Entrepreneurs have the option to exploit opportunities by leveraging incremental or radical technological advances to provide a good or service with incremental or radical market disruption (Lumpkin & Dess 1996; Navis & Glynn 2011). Linking the different dimensions of innovation newness—technology newness and/or market newness—with the level of innovation newness—incremental versus radical innovations—provides a framework for broadly classifying the overall newness of an innovation within an entrepreneurial venture (See Fig. 1).

At one extreme, entrepreneurs can exploit a radical new technology to provide a product or service intended to radically disrupt the market through the creation of a new product-market space. Such an entrepreneur embraces the highest level of innovation newness relative to other alternatives. The members of the venture need to participate in the establishment of the new market category they are creating and in so doing they need to develop a base of knowledge and foster public acceptance and recognition of the emergent category (Aldrich & Fiol 1994; Navis & Glynn 2010, 2011). Furthermore, because they are exploiting radical technology, they confront high levels of technological uncertainty and they need to help the market understand, accept, and embrace a new technological advance (see Quadrant D in Table 1). At the other extreme, entrepreneurs that create an organization to exploit or incrementally improve on an existing technology and seek to operate within an established market category confront the lowest levels of innovation newness relative to other alternatives (see Quadrant A in Table 1).

Between these two extremes, some entrepreneurs may create and exploit a radical new technology to establish a venture to compete in an existing market category (Quadrant C in Table 1). Also between the two extremes, a new venture may exploit and incrementally improve on an existing technology but participate in the establishment of a new market category (Quadrant B in Table 1).

In the past, the dimensions of newness (technological and market) and the levels of newness (radical and incremental) have provided a basis for understanding how a firm’s market orientation is related to successful breakthrough innovation (Zhou et al. 2005). The dimensions and levels of newness have also been outlined as elements to consider in making decisions with respect to a firm’s innovation portfolio (Day 2007) and for understanding the link between project evaluation criteria and project success (Carbonell-Foulquie, Munuera-Aleman, & Rodriguez-Escudero 2004). Therefore, the concepts of newness dimensions and levels have been useful in understanding links between innovation and firm performance, but to date these dimensions have not been jointly utilized to evaluate legitimacy pressures on new ventures and to consider potential responses to those pressures.

In addressing our research questions, the different levels and dimensions of “innovation newness” provide a basis to consider how different legitimation strategies may help overcome the liability of newness associated with new venture creation. This may be particularly important within an entrepreneurial ecosystem seeking to focus on the entrepreneur and yet trying to elevate the “winners” for eventual success. Next, we reflect on the theory pertaining to legitimacy judgments to connect innovation newness with new venture legitimation within and beyond an entrepreneurial ecosystem.

5 New venture legitimation strategies

Prior research indicates that successful legitimation of new ventures partially explains many positive entrepreneurial outcomes including organizational emergence (Tornikoski & Newbert 2007), venture survival (Delmar & Shane 2004; Sine et al. 2007), access to venture capital (Zott & Huy 2007), and firm valuation (Martens et al. 2007).

A lack of legitimacy is a crippling problem, particularly for new ventures within an entrepreneurial ecosystem that develop a radical new technology or seek to disrupt a market by creating a new category (Aldrich & Fiol 1994; Navis & Glynn 2011). Since the activities of such a venture are not widely known or well-understood, the ecosystem partners and supporters are less likely to accept and support what they are doing, meaning that the entrepreneurial ecosystem cannot fulfill its purpose of enabling and fostering productive entrepreneurship. Because of the challenge that entrepreneurs confront in fostering legitimacy for a new venture, some scholars have proposed strategies that can be employed to foster new venture legitimacy. These strategies are particularly relevant within the context of an entrepreneurial ecosystem because they focus on a venture’s relatedness to its external environment. Zimmerman and Zeitz (2002) suggest there are four basic legitimation strategies available to new ventures—conformance, selection, manipulation, and creation. We highlight each as follows:

Conformance strategy

A new venture that conforms does not question, change, or violate the social structure but rather “follows the rules.” A conformist strategy signals allegiance to the cultural order and poses few challenges to established institutional logics (Meyer & Rowan 1977; Suchman 1995). Thus, it is a strategy of fitting into the local ecosystem context of firms to be seen as legitimate. Zimmerman and Zeitz (2002) point out that conformance is a widely used legitimation strategy for new ventures.

Selection strategy

A selection strategy involves locating in a favorable environment such as an entrepreneurial ecosystem (Scott 1995; Suchman 1995). For the new venture, selection allows for the choice of an environment that is consistent with and advantageous for the new venture. If an entrepreneur has the insight and resources to select a favorable environment, then the selection strategy can be highly effective for attaining legitimacy (Zimmerman & Zeitz 2002).

Manipulation strategy

Manipulation is the attempt to make changes in the current ecosystem environment to achieve consistency between an organization and its environment (Zimmerman and Zeitz 2002). This may involve getting rules and regulations changed so that a new venture can legitimately engage in an activity that was previously disallowed. Because manipulation involves changing some of the scripts, rules, norms, values, logics, or models that exist in a particular ecosystem, it requires more effort and is more strategic than selection and compliance legitimation strategies (Zimmerman and Zeitz 2002).

Creation strategy

A creation legitimation strategy requires that an entrepreneur create a new social context by creating new rules, norms, values, scripts beliefs, models, etc. New ventures, especially those in new industries or attempting to establish new market categories, “often uncover new domains of operations that lack existing scripts, rules, norms, values, and models” (Zimmerman and Zeitz 2002: 422). Therefore, the basis from which new ventures derive legitimacy may not necessarily be established, requiring a creative entrepreneur to act as a pioneer in order to establish the basis of legitimacy for those that come after it (Anderson & Zeithaml 1984; Miller & Dess 1996). Creation is the most strategic of the four new venture legitimation strategies in that it offers an entrepreneur the most latitude in deciding what he/she will do to legitimate a new venture, yet it is also the most challenging to achieve a positive outcome (Zimmerman & Zeitz 2002).

The four legitimation strategies are conceptualized to sit on a punctuated continuum from less strategic to more strategic. Conformance is the least strategic, requiring the lowest level of intervention and no enactment of change in the external environment, and the creation strategy is the most strategic as it requires a high level of intervention and the establishment of a new external environment. Selection falls toward the conformance end of the continuum and manipulation toward the creation end. The more strategic a legitimation strategy, the costlier it is for an entrepreneur to implement (Zimmerman & Zeitz 2002). Conformance as the least strategic legitimation strategy is also the least costly to implement because it requires the lowest level of change within an existing ecosystem. Creation, as the most strategic legitimation strategy, is the costliest to implement because it requires the highest level of change within an existing ecosystem, potentially even the establishment of a new ecosystem. Selection is less costly than manipulation and creation, but costlier than conformance, while manipulation is less costly than creation, but costlier than conformance or selection.

Although the existing research provides useful descriptions of and insight into the different legitimation strategies available to entrepreneurs, there is no theory predicting when each of the respective strategies should be used, especially when developing a venture within an entrepreneurial ecosystem. Zimmerman and Zeitz (2002: 428) suggest that researchers should “look at the conditions under which each strategy is most effective”. To address this issue, we consider how the dimensions and levels of innovation newness in entrepreneurial ventures relate to the legitimation strategies employed, to foster legitimacy within an entrepreneurial ecosystem. We focus on identifying the most effective cost-benefit trade-off of different legitimation strategies in different scenarios. We strive to isolate the legitimation strategy that is most likely to allow for a new venture to be perceived as legitimate within an entrepreneurial ecosystem at the most effective cost to an entrepreneur.

6 Innovation newness and legitimation strategies

The framework we described earlier (Fig. 1) provides a basis for classifying the market and technological newness within an entrepreneurial venture. In this section, we consider how the innovation newness within a venture is related to the legitimation strategy employed. We work through the four quadrants in Fig. 1 to link innovation “newness” to the appropriate legitimation strategy.

Incremental technology and incremental market innovation

Entrepreneurs that incrementally advance existing technology and operate a venture in an existing market category (Quadrant A in Fig. 1) can link the explanation of what they are doing to existing institutional structures within an ecosystem in an effort to attain legitimacy (Aldrich & Fiol 1994; Navis & Glynn 2011). To garner legitimacy for the venture, the technology can be described with reference to existing products or services that utilize similar technology and the product or service can be compared to other products or services in the same market category or ecosystem. As Suchman (1995: 587) points out, “this type of adaptation does not require [entrepreneurs] to break out of prevailing cognitive frames (Oliver, 1990); rather, the conformist can turn a liability into an asset, taking advantage of being a cultural ‘insider.’” Because the existing rules, norms, values, beliefs, and models are well-established (for that particular entrepreneurial ecosystem), an entrepreneur merely needs to comply with the rules and expectations of the partners in that ecosystem to garner legitimacy for the venture. Using an example from the transportation community, Luxgen—the Taiwanese car manufacturer launched in 2009—leveraged existing automobile technology to compete in the established SUV and sedan automobile categories in China. Luxgen was able to conform to the established practices and norms of the transportation community to be perceived as legitimate; Luxgen cars were made to look very similar to the models of existing car brands within the automobile ecosystem, they were distributed through a network replicating existing industry practices, and their showrooms looked very similar to competitors’ (http://www.gtplanet.net/forum/). By conforming to industry and ecosystem norms and “fitting in” with the expectations of the transportation community, Luxgen was quickly able to quickly and cost effectively acquire legitimacy. The preceding arguments suggest the following:

Proposition 1

When launching a new venture with incremental technological advancements to enter an existing market category, a conformance legitimation strategy will likely provide the most valuable cost-benefit trade-off for attaining legitimacy within an entrepreneurial ecosystem, compared to other alternatives.

Conformance is the most frictionless means for an entrepreneur to acquire legitimacy for a new venture because it does not require the entrepreneur to change anything in the institutional environment (e.g., the entrepreneurial ecosystem). The focus of a conformance strategy is on fitting in with the norms and standards of an existing entrepreneurial ecosystem; hence, the entrepreneur has to do very little institutional work to attain legitimacy (Lawrence & Suddaby 2006; Suchman 1995). Because conformance requires limited institutional work with an ecosystem, adopting such a strategy minimizes the costs and risks of attaining new venture legitimacy. As such, entrepreneurs will tend to default to a conformance strategy where it is possible to do so, but in some cases, it is not possible to merely conform because aspects of the venture do not naturally fit within the established ecosystem. In such cases, an entrepreneur must adopt either a selection, manipulation, or creation legitimation strategy.

Radical technology and incremental market innovation

New ventures that develop a new technology to enter an existing market category (Quadrant B in Fig. 1) face an increased legitimacy hurdle because the audience within an entrepreneurial ecosystem is likely unfamiliar with and, therefore, uncertain about the new technology being introduced by the venture. The development of a new technology therefore exacerbates the liability of newness of an entrepreneurial venture. While the development of a new technology increases the legitimacy liability for the venture within an ecosystem, by operating in an existing market category, an entrepreneur can link aspects of the venture to existing institutional infrastructure to attain legitimacy (Aldrich & Fiol 1994; Navis & Glynn 2011). The venture can readily be compared to other products or services in the category. Because social objects are evaluated via categories, fitting in with an existing category confers meaning and order, thereby enhancing the legitimacy of an object being evaluated. Zuckerman (1999) referred to this as the “categorical imperative.” Under such conditions, an entrepreneur can enhance new venture legitimacy by carefully selecting a market category, ecosystem, and/or an early customer base for the new product or service (Zimmerman & Zeitz 2002). By selecting a market category, ecosystem, and/or a customer base made up of “early adopters” for whom trying out a new innovation is normal and appealing (Rogers 2010), an entrepreneur can allow a venture with a new technology to quickly gain acceptance. For example, returning to the transportation community, Tesla Motors—the new electric car manufacturer that emerged in early 2003—first produced an electric “sports car.” Tesla focused on developing “innovative battery and charging technology” to gain “a substantial lead in making batteries cheaper and recharging quicker than its competitors” (http://www.technologyreview.com). But, Tesla also created vehicles that looked somewhat similar to and compete with other high-end, luxury sports cars thereby fitting into an existing market category. The legitimacy of Tesla was strategically managed by locating the company on the West Coast of the USA (e.g., Silicon Valley) where innovation and novelty are embedded in that regional ecosystem (Saxenian 1996). If Tesla Motors had been located in an area with fewer early adopters where innovation is less readily embraced, then it would likely not have gained legitimacy so quickly or it would have been much costlier for it to do so. This example and the preceding arguments suggest the following proposition:

Proposition 2

When launching a new venture with radical new technology to enter an existing market category, a selection legitimation strategy will likely provide the most valuable cost-benefit trade-off for attaining legitimacy within an entrepreneurial ecosystem, compared to other alternatives.

The legitimation strategy of selection takes more effort and comes with more risk than mere conformance because the entrepreneur needs to find an appropriate ecosystem and figure out how to operate in that ecosystem; therefore, selection will only be used when the entrepreneur does not have the option to merely conform as a means to gain venture legitimacy. Yet, the selection strategy is less costly and less risky than manipulation or creation. Therefore, entrepreneurs will use a selection strategy more readily than manipulation or creation where possible. However, there are situations when the newness of the venture necessitates that an entrepreneur utilizes manipulation or creation strategies to overcome the legitimacy hurdles confronting the venture.

Incremental technology and radical market innovation

New ventures that exploit existing technology to radically disrupt a market by creating a new market category (Quadrant C in Fig. 1) operate in an institutional void because the norms and expectations of their context are not yet established. The venture’s product or service does not fit into an existing category; therefore, it is difficult for audiences to evaluate it, and as such, the legitimacy of the new venture is questioned (Zuckerman 1999). Although the venture leverages an existing technology, which increases understanding and acceptance of the organization, that technology is being used in a new way to create a new market category; therefore, the entrepreneur needs to change the perception of the audience within an ecosystem about how the technology should be applied. Therefore, the entrepreneur needs to manipulate people’s perceptions of the technology so that they can view it in a new way. For example, once again in the transportation community, Zipcar—the car-sharing venture launched in 2001—utilized existing automotive and wireless technology to create a service that would be at the forefront of the new car-sharing market category in the USA (Hart, Roberts, & Stevens 2005). The Zipcar founders needed to manipulate the transportation community’s perceptions about car ownership and motor vehicle use to get them to embrace the concept of car sharing. To do so, Zipcar agents worked to help them understand that the norms associated with traditional car rentals could be changed to make it appealing to a very different audience (Hart et al. 2005). Thus, they were required to manipulate perceptions and norms of those within their ecosystem to gain legitimacy for the venture. As part of educating the public and other stakeholders, the media can play a significant role especially when a market is emerging (Rindova, Petkova, & Kotha 2007). In these situations, entrepreneurs need to be especially cognizant of managing their message. Hence, we propose:

Proposition 3

When launching a new venture that uses existing technology to create a new market category, a manipulation legitimation strategy will likely provide the most valuable cost-benefit trade-off for attaining legitimacy within an entrepreneurial ecosystem, compared to other alternatives.

Manipulation as a legitimation strategy requires entrepreneurs to make changes to their environment to achieve consistency between the organization and its environment; yet, changing the environment is difficult. When dealing within an entrepreneurial ecosystem, it is very difficult for the entrepreneur to spend the time and money convincing the different constituents to understand the new market category. Zimmerman and Zeitz (2002: 425) explain that a “single new venture, by itself, generally lacks the money or power to significantly manipulate its environment (Brint & Karabel, 1991; DiMaggio & Powell, 1983; Fligstein, 1991; Meyer & Rowan, 1977; Powell, 1991).” Because of the challenges associated with a manipulation legitimation strategy within an entrepreneurial ecosystem, entrepreneurs will only employ the effort and incur the cost to adopt such a strategy if a conformance or selection manipulation strategy will not suffice. Yet, in some extreme cases, where entrepreneurs are launching a venture that seeks to develop a new technology that will create a new market category, a manipulation strategy may not suffice and a creation strategy may be required to achieve venture legitimacy.

Radical technology and radical market innovation

New ventures that develop a radical new technology and utilize it to create a new market category (Quadrant D in Fig. 1) face the greatest legitimacy challenge. The norms and expectations of their market context are not established and the technology underlying the venture is unfamiliar. Hence, an entrepreneur creating a venture of this nature faces the challenge of having to create new rules, norms, values, beliefs, or models. Not only do they need to explain a new technology to the ecosystem audience, but they also need to create the language and terminology to provide such explanations. In certain instances, the entrepreneur may actually be required to create a new ecosystem around their venture, to support what they are doing. The construction of a new market for a venture with a new technology thus depends on the entrepreneur drawing on characteristics of other fields that contain descriptions evoking the “new” message of the entrepreneur (Stringfellow, Shaw, & Maclean 2014). As Zimmerman and Zeitz (2002) point out: “Creation is especially evident in the introductory stage of new industries. It is the most strategic of the four strategies.” For example, SpaceX is a new venture that extends the transportation industry into space exploration, thereby, creating a new category of travel. To do this, SpaceX “designs, manufactures and launches advanced rockets and spacecraft…. [The venture] was founded to revolutionize space technology, with the ultimate goal of enabling people to live on other planets” (http://www.spacex.com/about). In so doing, SpaceX has to create the rules, norms, and models for civilian space travel if they are to be perceived as a legitimate organization to the entrepreneurial ecosystem. Furthermore, because SpaceX leverages cutting-edge technology, the entrepreneurs behind the venture have to develop the advanced technology and provide (or even create) ecosystem partners with an understanding of how it works. This example illustrates how entrepreneurs exploiting a new technology to enter or create a new market category need to create the social context for such ventures and therefore the creation legitimation strategy must dominate. Thus, we propose:

Proposition 4

When launching a new venture with a radical new technology that is used to create a new market category, a creation legitimation strategy will likely provide the most valuable cost-benefit trade-off for attaining legitimacy within an entrepreneurial ecosystem, compared to other alternatives.

Because of the costs, risks, and challenges associated with creation as a legitimation strategy, entrepreneurs only employ it when the other legitimation strategies of conformance, selection, and manipulation are not viable or are unlikely to have the desired effect. As the most strategic and costly of the legitimation strategies (Zimmerman and Zeitz 2002), it creates the most work for entrepreneurs; hence, they should only adopt it when they have no other choice.

Having described the link between the dimensions and levels of innovation newness and the legitimation strategies utilized in such ventures, we now consider how utilizing each of these legitimacy strategies may impact the spread of legitimacy for a new venture beyond an entrepreneurial ecosystem. The spread of legitimacy is a key issue for entrepreneurs with new ventures because it provides a basis for them to become known and accepted within an ecosystem more broadly and thereby provides a basis for the firm to acquire resources and access customers within and beyond an existing entrepreneurial ecosystem. Legitimacy diffusion is thus an antecedent to venture growth, and because venture growth is a key concern in entrepreneurship research and practice (Gilbert, McDougall, & Audretsch 2006; McKelvie & Wiklund 2010), the diffusion of new venture legitimacy beyond an entrepreneurial ecosystem is a highly pertinent issue.

7 Legitimacy assessment and audience diversity

Since legitimacy assessments represent social judgments that reside in the eye of the beholder (Ashforth & Gibbs 1990; Bitektine, 2011), such assessments are audience dependent (Suchman 1995). It is conceivable that technology and market newness may be perceived differently by different actors in the ecosystem and beyond. For example, what may seem to be incremental newness to one actor familiar with a certain technology may be deemed more radical by those outside of the technological sphere. The same may hold true for a market. One actor who may be quite familiar with a market could perceive the market newness as incremental yet someone with less understanding of that market may deem it a far more radical approach. We therefore recognize that entrepreneurs must manage new venture legitimacy judgments across diverse audiences with different interpretations of technology and market newness in an entrepreneurial ecosystem, so as to appear legitimate to garner needed resources for venture survival and growth.

Recently, scholars have highlighted that different new venture supporters likely operate with contrasting institutional logics, and thus, an institutional logics perspective provides a theoretically meaningful basis to distinguish between different categories of new venture audiences (Pahnke, Katila, & Eisenhardt 2015). Using institutional logics that characterize different new venture audience groups as a basis for uncovering how and why the legitimacy criteria for a new technology venture may vary depending on the audience, Fisher, Kuratko, Bloodgood, and Hornsby (2017) identified the varying logics of different actors important to new ventures. For example, crowdfunding backers tend to operate primarily with a community logic, government agents with a state logic, angel investors with a market logic, venture capitalists with a professional logic, and corporate venture capitalists with a corporate logic.

Fisher et al. (2017) utilized research on framing to describe how technology entrepreneurs may use emphasis framing to deal with the challenge of establishing new venture legitimacy with different audiences operating with different institutional logics and thereby improve their chances of accessing critical resources for venture survival and growth. They demonstrated that emphasis frames enable entrepreneurs to quickly and strategically adjust salient elements of their presentations, pitches, videos, documents, or meeting discussions to emphasize specific legitimacy mechanisms that align with the institutional logic of the focal audience.

Therefore, while the acknowledgment of different perceptions by different actors in an entrepreneurial ecosystem is important, the research suggests that by strategically framing the presentation of their venture to differing actors, entrepreneurs can be effective garnering legitimacy within and beyond an entrepreneurial ecosystem.

8 New venture legitimacy diffusion

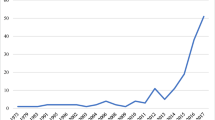

Past research has examined the general legitimacy diffusion process of a social object (Johnson et al. 2006; Tost 2011). This research describes legitimacy diffusion as a phased process beginning with innovation, followed by local validation, diffusion, and general validation (Johnson et al. 2006). Along these lines, we outline how new ventures move through a similar phased process of legitimation and legitimacy diffusion. The first phase is the innovation phase in which different dimensions and levels of newness—technology and/or market newness—are injected into a new venture. The second phase is the strategy phase in which an entrepreneur adopts a strategy to garner legitimacy for a venture. This may be a conformance, selection, manipulation, or creation strategy. The third phase is the local-validation phase in which individuals in an existing entrepreneurial ecosystem judge the legitimacy of a new venture. Individuals making legitimacy judgments may do so passively or they may engage in more of an active evaluation process (Tost 2011). The final phase is the diffusion phase in which the knowledge and understanding of a venture spreads beyond a local entrepreneurial ecosystem to a broader population and is more generally validated. Broad diffusion, beyond an existing ecosystem, is measured in terms of reach, narrow to wide. Reach reflects how far knowledge and acceptance of a venture disperses. The columns of Table 1 reflect the different phases of the legitimacy diffusion process for new ventures and the contents of each column highlight the various input and output of legitimacy diffusion.

Column 1 reflects the different categorizations of innovation newness in new ventures ranging from lower levels of newness to very high levels of newness. Column 2 reflects the legitimation strategies associated with the different levels of newness as described in Propositions 1–4. Column 3 reflects the nature of local legitimacy judgments within an entrepreneurial ecosystem. Column 4 reflects the reach of legitimacy diffusion beyond an entrepreneurial ecosystem. The columns of Table 1 are integrated into the process diagram in Fig. 2. Figure 2 highlights the key phases and relationships between constructs in the various phases of new venture legitimation within and beyond an entrepreneurial ecosystem. The local validation phase and legitimacy diffusion phase are the focus of the next portion of our theorizing.

8.1 Local validation

Recent research recognizes that a social object’s legitimacy is not only dependent on the strategies employed to foster legitimacy but also on how individual evaluators assess the output from such strategies (Tost 2011). As Suchman points out: “[Organizational legitimacy] represents a relationship with an audience, rather than being a possession of the organization” (Suchman 1995: 594). Hence, the quest for new venture legitimacy typically involves managing and satisfying the expectations of individual members of an organization’s immediate audience.Footnote 1 Therefore, if the legitimacy of a venture is to diffuse, a local audience first needs to validate the venture (Johnson et al. 2006; Tost 2011). For a new venture, the local audience consists of the individuals within an entrepreneurial ecosystem that come into direct contact with the venture and its founders as it becomes established. As the individual members of an entrepreneurial ecosystem are exposed to a new venture, they assess its component parts to consider whether it fits with their expectations to validate it as legitimate. The level of cognitive effort employed to make such assessments can range from passive (i.e., unconscious, intuitive) to active (i.e., effortful, engaging) (Kahneman 2011; Tost 2011).

Passive assessments

At the passive extreme of legitimacy assessments, individuals within an ecosystem may automatically validate a venture as legitimate because it immediately aligns with their cultural expectations (Tost 2011). They engage in very little effort to understand exactly what the venture does or how the different elements of the venture relate to one another. Rather, they just assume the venture is legitimate because nothing about the venture conflicts with their expectations. Legitimacy judgments are made in this way because, as prior research highlights, individuals prefer not to engage in effortful cognitive work if they can avoid it (Fiske & Taylor 1984; Kahneman 2011). Therefore, if there is no identifiable reason to expect that a venture may be illegitimate within an entrepreneurial ecosystem, then the automatic individual response may be to validate it as legitimate. As Johnson et al. explain, sometimes legitimacy may be acquired “simply by not being implicitly or explicitly challenged” (2006: 60).

Active assessments

The active end of the assessment continuum reflects effortful attempts on the part of individuals within an entrepreneurial ecosystem to validate the legitimacy of a new venture (Tost 2011; Kahneman 2011). At this extreme, an individual is motivated or compelled to consciously invest time and energy into constructing a legitimacy judgment. Research indicates that individuals typically need to have a reason to engage in such cognitive effort; some feature of the situation needs to demand that they carefully consider the judgment that they are making, otherwise, they will revert to a passive mode of assessment (Kahneman 2011).

The legitimation strategies adopted by an entrepreneur to legitimate a new venture may serve as a prompt for active legitimacy assessment by individuals within an entrepreneurial ecosystem. If a conformance strategy is adopted to legitimate a new venture, then the venture is positioned to just “fit in” with its institutional context, and there is nothing to prompt a local audience to question its reason for being within the ecosystem. However, as the legitimation strategy of an entrepreneur becomes more strategic, local evaluators within an entrepreneurial ecosystem need to think more carefully about whether the features of the venture is appropriate (Tost 2011). As described earlier, the legitimation strategies fall on a punctuated continuum from least strategic (conformance) to most strategic (creation). The more an entrepreneur tends toward the highly strategic end of the continuum, the more the individuals making legitimacy judgments within an ecosystem will be forced to confront something new or unexpected when evaluating the venture; therefore, the higher the likelihood that they will shift from a passive to active assessment mode (Tost 2011).

A conformance legitimation strategy results in a passive validation because conformance means that nothing new or unexpected is introduced for the local ecosystem audience to consider. When a conformance legitimation strategy is employed, the venture immediately appears legitimate because everything is aligned with the venture’s environment (Zimmerman & Zeitz 2002). Thus, when a conformance strategy is employed, the local validation of new venture legitimacy within an entrepreneurial ecosystem is most likely a passive assessment. Conversely, at the other end of the legitimation strategy continuum, a creation legitimation strategy involves significant change and divergence for an evaluator to process. A creation strategy means that an entrepreneur attempts to develop “something that did not already exist in the environment” (Zimmerman & Zeitz 2002, p. 425: new “rules, norms, values, beliefs (and) models” (p. 423). Because of the high level of newness and lack of familiarity associated with the creation strategy, those within an ecosystem judging the legitimacy of a new venture need to carefully and deliberately assess the venture and its relatedness to the environment to judge whether it is legitimate. Therefore, when a creation strategy is used to foster new venture legitimacy, then the local ecosystem audience most likely engages in an active assessment process to validate the legitimacy of a venture, so as to process and comprehend the new, unfamiliar information associated with the creation strategy.

Proposition 5

As the legitimation strategies adopted in a new venture become more strategic, the local validation of new venture legitimacy within an entrepreneurial ecosystem will most likely shift from passive to active assessment.

9 Legitimacy brokering and diffusion

When an evaluator makes a legitimacy judgment about a new venture, they may inform others within their social network of their views (Davies & Prince 2005). The sharing of information between actors in a social network is referred to as information brokering. There is a cost to information brokering to both the initiator and the receiver (Burt 2005). The costs include potentially losing trust if brokered information turns out to be useless or damaging plus the opportunity costs of not engaging in other activities (including giving or receiving information in other brokering situations). A benefit for an initiator might come from reputational and status enhancements within the network if the brokered information is meaningful (Berger 2013) or from getting others to do something the initiator wants done. For recipients of information brokering, the benefits might involve receiving unique or affirming information (Burt 2005). For social actors to actively engage in information brokering activities, they need to perceive that the benefits from brokering outweigh the costs.

Brokering activities are critical for the spread of information about new ventures beyond their local entrepreneurial ecosystem. Direct interaction between members of a network provides an opportunity for sharing legitimacy views (Burt 1987). Often, public sources of information about new ventures are relatively scarce, so any information coming from more private sources, such as network connections, is valued (Sorenson & Stuart 2001). Ongoing communications with network members also provide learning opportunities for network members whereby they can reconsider their views and potentially assimilate toward other members’ viewpoints (Alexy & George 2013). Moreover, network members are a more trusted source of new information compared to sources outside one’s network (Stuart & Sorenson 2007). Networks, especially dense ones that may have strong ties, provide sanctions as well as rewards, and thus, provide an incentive to members to share valuable information so that members will not be perceived as withholding valuable information or promoting disingenuous information. However, not all information is considered worthy of sharing with others. If there is nothing surprising or interesting about new information, then it is less likely to be shared within a social network (Berger 2013). Research in the marketing literature suggests that novel and distinguishable information is more likely to be shared within a network, even though it can be more difficult to explain (Elfring & Hulsink 2003), because such information provides “social currency” for the broker—people like to share things that make them look good (Berger 2013). Novel and distinguishable information is more likely to make a broker look good because it signifies the introduction of new value and insight into a network.

Relating this back to new venture legitimacy judgments, where individuals have made passive judgments about the legitimacy of a venture, they are less likely to be conscious of novel and distinguishing features of the venture. Passive judgments are associated with conformance legitimation strategies (see Proposition 5) and, in the process of making passive legitimacy judgments, the features and dimensions of the venture are not consciously accounted for (Tost 2011); therefore, information about the venture is unlikely to be brokered with others outside of an entrepreneurial ecosystem. Conversely, where an individual evaluator within an ecosystem has engaged in a conscious and active assessment of a new venture’s legitimacy, they are more likely aware of its unique and distinguishing features. Moreover, active evaluation is associated with entrepreneurial ventures that engage in a creation strategy to foster legitimacy (Proposition 5) and such ventures are likely to encapsulate the highest level of innovation newness (Proposition 4). Therefore, where an individual has to engage in a very active evaluation process to assess a new venture’s legitimacy, it means that the new venture likely has technology and or market features that are novel and distinguishable which are more likely to be shared with others outside of an entrepreneurial ecosystem, because information about the venture serves as social currency for the broker (Berger 2013).

Thus, when new technologies and/or markets are the primary focus of a venture, there is much for individuals within an entrepreneurial ecosystem to accentuate when interacting with others outside of the existing ecosystem. And this new information and knowledge can be highly sought after by those outside of an entrepreneurial ecosystem (Bae, Wezel, & Koo 2011). This will enhance the level of information brokering about the venture. Conversely, when a new venture focuses on existing technologies and markets, there is little for actors to share with others about the venture and this can limit brokering.

Proposition 6

Active evaluation of new venture legitimacy is positively related to new venture legitimacy brokering activities with others outside of an existing entrepreneurial ecosystem resulting in legitimacy diffusion.

The diffusion of legitimacy for new ventures beyond an entrepreneurial ecosystem is analogous to a viral and self-reinforcing process in that as more and more actors beyond an entrepreneurial ecosystem perceive a venture as legitimate, so do other connected actors assume the venture is appropriate and begin to take it for granted (Shepherd & Zacharakis 2003). This in turn causes other organizations to imitate it (Davis 1991; Westphal, Gulati, & Shortell 1997) thereby further reinforcing the original entity’s legitimacy outside of its ecosystem.

To the extent that a number of the characteristics of an entrepreneurial ecosystem and environments external to it are consistent with those that describe a network, it is important to examine how networks can influence new venture legitimacy. It is likely that entrepreneurial ecosystems will vary in the structural and relational dimensions of their networks. For example, some ecosystems will have more interactions and closer ties than others. In fact, by design in many cases, the interactions, support, and relationship building that occur in entrepreneurial ecosystems provide the opportunity for the creation of denser and stronger ties among the members of the ecosystem that can help entrepreneurs. Networks beyond those found in an ecosystem can have a variety of structural and relational dimensions. Baum et al. (2003) found small-world network structures existing in the Canadian investment bank industry. These structures are characterized by cliques of highly connected organizations that have a small number of intermediary organizations that connect the cliques. The cliques may have a large number of strong ties that promote internal information sharing, but the separation of cliques within a larger network can be illustrative of a more open network that is sparse with weak ties.

Thus, an entrepreneur who is seeking legitimacy for his or her new venture within their ecosystem likely faces a somewhat different environment than when he or she tries to get the new venture legitimacy to spread beyond the ecosystem. Within an ecosystem, an entrepreneur may partner with high-status actors in the ecosystem and such ties can serve as venture legitimation signals to other actors in the ecosystem (Elfring & Hulsink 2003). A visible tie with a high-status actor within an entrepreneurial ecosystem suggests that the venture has been vetted by the high-status actor (Rindova, Petkova, & Kotha 2007) and others within the ecosystem will lend credence to such judgments. Outside the ecosystem, an entrepreneur may find a large variety of networks that may be indifferent or even hostile to the new venture. Actors from outside an entrepreneurial ecosystem are much less likely to be aware of the status or reputation of venture partners from within the ecosystem, hence, ties to such partners no longer serve as strong legitimating mechanisms when a venture moves beyond the ecosystem. For example, if the entrepreneur seeks legitimacy with organizations that are members of a dense network beyond the original ecosystem in which the venture was founded, the network members are more likely to be reliant on their strong network ties (Suarez 2005) and closed-minded to different approaches unless those approaches’ perceived value surpasses the network members’ desire for internal conformity and to work within their trusted network. Even in more open networks outside the ecosystem, there are likely to be network members who must be convinced of the pragmatic benefits of working with a new venture before they are willing to consider changing their current approaches.

Jensen (2008) uses the terms exclusion and inclusion to refer to the extent that organizations in other networks are willing to collaborate with a new venture. Exclusion means that an organization prefers to not work with a new venture and inclusion means that an organization prefers to work with a new venture. Often times, these decisions are made for pragmatic, self-serving reasons as well as a reaction to the social embeddedness of the organization within their own network. Moving outside of an ecosystem is similar to moving beyond a network whereby the natural uncertainty of a new venture’s products and services is compounded by the lack of familiarity these organizations have with the new venture (e.g., information asymmetry (Williamson 1975, output quality (Podolny 2001)). Thus, outside the entrepreneurial ecosystem, new venture legitimacy evaluations initially occur without the benefit of the connections found within the ecosystem. This can make it more difficult for the entrepreneur to gain positive legitimacy judgments outside the ecosystem; however, a relatively more active and strategic approach may enhance potential success. Legitimacy diffusion may be more successful in a closed network with strong ties because the closeness of the network members enables enhanced trust and information sharing, from brokering, for instance, than that which would be found among more sparsely connected organizations with weaker ties. In an approach similar to that of van Wijk et al. (2013), who describe how an innovation can lead to field change, knowledge about a new venture that is transmitted between network members with strong ties is more likely to be believed and result in less uncertainty thereby giving new venture legitimacy a stronger base for ongoing diffusion.

Proposition 7

New venture legitimacy brokering activities with others outside of an existing entrepreneurial ecosystem will result in greater legitimacy diffusion in dense networks with strong ties than in sparse networks with weak ties.

Bringing all this together highlights the paradox in the diffusion of new venture legitimacy. Individual legitimacy assessments about new ventures in the judgment phase are likely to be rapid and passive when a firm leverages existing technology to enter an existing market category and the entrepreneur uses a conformance strategy to legitimate the venture. However, such judgments are not likely to be relayed to others beyond an existing ecosystem. Therefore, the legitimacy of such ventures fails to spread across a population in the broad diffusion phase. Conversely, individual legitimacy assessments about a venture developing a new technology to create a new market category are likely to be slow and critical in the judgment phase as individual actors struggle to make sense of what the venture is doing and how it fits in because of all the newness embedded in the venture. Yet, after favorable legitimacy judgments, the diffusion of legitimacy about such ventures beyond the initial entrepreneurial ecosystem is likely to be rapid as actors within that ecosystem perceive it to be beneficial to share information about the novel and distinguishing features of the venture with others outside of the ecosystem. These paradoxical differences in the judgment and diffusion of new venture legitimacy are reflected in Table 1.

10 Discussion

An entrepreneurial ecosystem is orientated toward creating an environment conducive to the success of new entrepreneurial ventures. However, new ventures confront the challenge of establishing their credibility or legitimacy within and beyond that ecosystem. The concept of newness serves as both a source of competitiveness and as a liability for new ventures. Newness serves as a source of advantage in that new ventures often introduce new technologies and create new market categories to unlock new sources of value (Christensen 1997; Schumpeter 1934). But, newness is also a liability because the lack of performance history and consequent illegitimacy of new ventures serves as a burden when acquiring resources and when entering into ecosystem relationships (Aldrich & Fiol 1994; Stinchcombe 1965). To overcome the illegitimacy burden, entrepreneurs engage in various approaches to legitimate a new venture including partnering with better-known organizations (Rindova et al. 2007) and employing strategies such as conformance, selection, manipulation, and creation (Zimmerman & Zeitz 2002). While these legitimation strategies are useful for understanding how entrepreneurs may overcome their illegitimacy challenges, existing literature provides little guidance on when each of these strategies is used in a productive way. Each of the various legitimation strategies is associated with different levels of cost and risk and hence it is important to understand when each is likely to be productively employed. Overall, our theorizing indicates that as the level of technological and market newness within a new venture increases, the strategies to foster legitimacy within an entrepreneurial ecosystem should become more strategic.

For a new venture to grow and to be able to access resources from a broader population beyond an entrepreneurial ecosystem, the perceptions of new venture legitimacy need to diffuse. Although scholars have begun to consider how the legitimacy of a social object diffuses to a broad population (e.g., Johnson et al. 2006; Tost 2011), the nuances of legitimacy diffusion for new ventures operating in an entrepreneurial ecosystem have not yet been addressed. It is unclear how the strategies used to foster legitimacy for a new venture (e.g., conformance, selection, manipulation, and creation (Zimmerman & Zeitz 2002)) impact the diffusion of legitimacy beyond an entrepreneurial ecosystem. Therefore, although the diffusion of legitimacy is critical for a new venture to be fully legitimated, the antecedents of diffusion are not well-understood. To examine this issue, we consider how individual judgments of new venture legitimacy are made and we assess the impact that such modes of judgment will have on whether information about the new venture is brokered across social networks extending beyond an existing entrepreneurial ecosystem. Overall, our theorizing indicates that as the strategies to foster legitimacy become more strategic, individuals will engage in more active judgment of new venture legitimacy and, in turn, are more likely to share their legitimacy judgments with others beyond an entrepreneurial ecosystem, leading to higher levels of legitimacy diffusion.

This research integrates ideas from and adds to three different literatures. First, we describe a model reflecting the relative newness of entrepreneurial ventures thereby building on and adding to the literature at the intersection of entrepreneurship and innovation (e.g., Benner & Tushman 2003). Second, we utilize and extend concepts from the new venture legitimacy literature (e.g., Zimmerman & Zeitz 2002) to relate new venture newness to different legitimation strategies thereby explaining when and why different new venture legitimation strategies are productively employed within an entrepreneurial ecosystem. Third, we integrate ideas from the legitimacy diffusion literature (e.g., Johnson et al. 2006; Tost 2011) to extend the applications of this literature to the new venture domain and, in so doing, describe how different types of new venture newness and different legitimation strategies result in different levels of legitimacy diffusion beyond an entrepreneurial ecosystem.

The conceptual insights emerging from the integration of these literatures highlight an important challenge for new ventures: entrepreneurs that pursue opportunities exploiting technological and market newness confront the greatest challenge in legitimizing their venture within an entrepreneurial ecosystem; but, if they can clear a legitimacy threshold, information about their venture will spread more broadly and rapidly beyond the ecosystem in which it was established, resulting in high levels of legitimacy diffusion. Conversely, entrepreneurs that create new organizations utilizing existing technology for an existing market category have an easier time legitimizing their venture with individuals within their ecosystem but the diffusion of new venture legitimacy beyond the borders of the ecosystem is likely to be limited.

The process model and framework created in this manuscript point to a number of significant theoretical implications. First, new ventures that leverage new technologies and establish new market categories confront more significant legitimacy challenges than new ventures leveraging existing technology, entering an established market category or both. Leveraging new technology and establishing a new market category require more effort, cost, and risk on the part of an entrepreneur to meet the legitimacy threshold for new ventures. From a theoretical standpoint, it is useful to isolate dimensions that affect new venture newness to more readily recognize the legitimacy challenges confronted by such ventures.

Second, strategies employed to garner legitimacy for new ventures have an impact on how passive or active the judgment of the new venture legitimacy is, which in turn impacts the likelihood that information about the venture will be brokered beyond an entrepreneurial ecosystem. Establishing an explicit connection between efforts to legitimate new ventures by those controlling the venture and legitimacy judgments of new ventures by those evaluating the venture is an important advancement for research on new venture legitimacy. Tost (2011) integrated institutional theory and social psychology to outline a useful framework for considering factors impacting legitimacy judgments. We extend the ideas put forward by Tost (2011) by considering how they integrate with existing literature on new venture legitimacy. In so doing, we are able to relate how the strategies employed by entrepreneurs to legitimate new ventures translate into legitimacy judgments by key audience members (within an entrepreneurial ecosystem). Although the link between legitimation activities and legitimacy judgments has been assumed in the literature on new venture legitimacy (e.g., Aldrich & Fiol 1994; Navis & Glynn 2011; Zimmerman & Zeitz 2002), the nature of this link has not yet been articulated. We theorize a specific set of relationships between legitimation strategies and legitimacy judgments to provide a useful theoretical connection between ventures and evaluators.

Third, if new ventures are to access resources and enter into exchange relationships with those beyond the entrepreneurial ecosystem, then they need to be perceived as legitimate by a broader population beyond the ecosystem. For this to happen, new venture legitimacy needs to diffuse. In our theorizing, we describe how information brokering between actors in a social network is associated with the diffusion of new venture legitimacy beyond an existing ecosystem. Furthermore, we outline why information about some new ventures is more likely to be shared than others, thereby theorizing about which new ventures will experience higher and lower rates of legitimacy diffusion. Although the process of legitimacy diffusion has been the focus of recent theoretical advancements (e.g., Johnson et al. 2006), new venture legitimacy diffusion has not yet been considered, especially within the context of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Explicitly linking new venture legitimacy diffusion with legitimacy judgments and new venture legitimation strategies is a significant advancement in the literature on new venture legitimacy as well as the emerging literature on entrepreneurial ecosystems.

From a practical standpoint, there are a number of considerations that arise for entrepreneurs launching new ventures. First, by recognizing and understanding that technology and market newness impact legitimation efforts, revolutionary entrepreneurs—those creating ventures with radical new technologies and/or establishing new market categories—can more readily prepare to confront legitimation challenges as they embark on the process of establishing a new venture within an entrepreneurial ecosystem. They need to ensure that they have the resources and capacity to engage the legitimation effort required to meet the more challenging legitimation challenge immediately confronting their organization, and the recognition that once the initial legitimacy hurdle is passed the venture may have an easier time keeping the legitimation process going. In addition, as the legitimation process unfolds, the ecosystem incumbents may also begin to engage in mutual adaptation with the new venture (Van Wijk et al. 2013), and this can create conditions whereby the acceptance of the new venture becomes even more pronounced. This is likely to be positively influenced by repeated interactions between the new venture and ecosystem members (Cattani et al. 2008). On the other hand, entrepreneurs with ventures that rely more on existing technologies and markets should understand that the increased likelihood of early legitimacy means they can save some of their resources for later periods when the legitimation process slows down.

Second, the theory outlined here suggests that entrepreneurs should aim to select and enact an appropriate legitimation strategy relative to the technology and market newness embedded in their venture. By fully assessing technology and market newness embedded in a venture and recognizing the linkage between such newness and legitimation strategies, entrepreneurs can ensure that there is appropriate alignment between the nature of the venture and the primary type of legitimation strategy adopted. If the legitimation strategy is out of alignment with the nature of the venture, then entrepreneurs may end up not investing enough in legitimation efforts thereby never allowing their venture to clear the appropriate legitimacy threshold within an entrepreneurial ecosystem. Alternatively, if entrepreneurs invest too heavily in legitimation efforts, they may squander valuable resources that are needed for other things in the development of a new venture.

Third, because diverse actors make legitimacy assessments in an entrepreneurial ecosystem, they may invoke different institutional logics to determine legitimacy criteria and they may have different perceptions of what newness means with respect to technologies or markets. Actors familiar with certain technologies or certain markets may categorize certain ventures as far less new than those actors outside of those spheres. Thus, entrepreneurs may benefit from developing an understanding of the differing institutional logics and newness perceptions that characterize the new venture audience groups within and beyond an entrepreneurial ecosystem. Once identified, entrepreneurs can potentially utilize emphasis framing to quickly and strategically adjust salient elements of their presentations, pitches, videos, documents, or meeting discussions to emphasize specific legitimacy mechanisms that align with the institutional logic of the focal audience.