Abstract

Microfinance institutions (MFIs) are typical examples of hybrid organisations, meaning organisations pursuing both a financial and social logic. This study examines the question of whether financial and social performance improves when an MFI’s chief executive officer (CEO) has a business education. We apply the random effects instrumental variable regression method to examine the influence of the CEO’s business education on the MFI’s financial and social performance. Our panel dataset that includes 353 MFIs from across the globe indicates that ‘only’ 55% of the MFIs have a CEO with a business education. The empirical results indicate that MFIs with CEOs who have a business education perform significantly better, financially and socially, than MFIs managed by CEOs with other types of educational backgrounds. The findings suggest that CEOs with a business education seem better at managing the much-debated tradeoff between providing small loans and producing healthy financial results.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Who should manage microfinance institutions (MFIs)? Chief executive officers (CEOs) of MFIs work with two institutional logics, i.e. development logic and banking logic (Battilana and Dorado, 2010). The banking logic requires ensuring financial sustainability, i.e. sufficient income to cover operating expenses while the development logic requires the provision of relevant banking services to poor segments of the population. Since banking services for low-income families mirror traditional banking, one would expect that CEOs with a banking background and business education are the best candidates to manage MFIs. This is, however, often not what is observed in practice. Since microfinance also has a development logic, it attracts managers with diverse educational backgrounds. In fact, the dataset applied in this paper indicates that ‘only’ 55% of the MFIs have a CEO with a business education. It is, therefore, an open empirical question as to what kind of CEO’s educational background enables the optimal management of the two logics in MFIs. In this study, we look into this problem by testing whether MFIs in which CEOs have a business education achieve better financial and social performances than MFIs managed by CEOs with other educational backgrounds. This is a relevant research question because many MFIs in the near future could be replacing their founder CEOs (Randøy et al., 2015). Moreover, MFIs are typical examples of social enterprises, often referred to as hybrid organisations, which are firms claiming to have social objectives alongside their aim of being profitable (Battilana and Dorado, 2010; Miller et al., 2012). This paper is therefore relevant also outside the microfinance setting (Lepoutre et al., 2013).

Existing empirical research on the relationship between the CEO’s business education and an organisation’s performance uses data from traditional industries and banks (Bertrand and Schoar, 2003; Gottesman and Morey, 2010). Using data from MFIs, researchers have examined the influence and association of a CEO’s founder status (Randøy et al., 2015), a CEO’s gender (Périlleux and Szafarz, 2015; Strøm et al., 2014) and the dual role of being the CEO and board chair (Galema et al., 2012) on an MFI’s performance. Thus far, a gap remains, both theoretically and empirically, when it comes to studying the association between a CEO’s type of education and an MFI’s performance.

Understanding the relationship between the CEO’s type of education and the MFI’s performance is important. The kind of education the CEO has received may be a resource that is critical for increasing the productivity and performance of organisations considered vital for the further development of the industry (Cull et al., 2007). After all, MFIs already serve more than 200 million micro-enterprises and low-income families with loans, and there is still an enormous untapped market of several billion persons (Cull et al., 2014).

This study focuses on CEOs, because they provide leadership and take a lead in decision making, and so their central role in this regard means they are critical for the success of organisations (Wittmer, 1991). Identifying whether CEO characteristics, like educational background, can enhance MFIs’ performance and outreach is thus crucial. We further argue that a CEO’s business education is an important resource for the organisation, for it provides a basic understanding of the organisation’s complexity and the institutional environment in which it operates. Thus, the type of education of the CEO influences her/his strategic choices, so that MFIs where the CEOs have a background in business education might achieve a better performance than MFIs managed by CEOs without a business education background. Similar to Randøy et al. (2015), we test this hypothesis using the random effects instrumental variable regression method on a global panel dataset consisting of 353 MFIs.

Our results suggest that MFIs managed by CEOs with a business education are more profitable and cost efficient and reach out to poorer clients. This latter finding is particularly interesting, since some might fear that letting CEOs with a business profile manage MFIs could lead to a mission drift away from serving poorer clients. Accordingly, CEOs with a business education seem better at managing the much-debated tradeoff between providing small loans and producing healthy financial results. Thus, our finding should motivate MFIs and their boards to increasingly search for candidates from traditional banks and businesses when hiring new managers.

The rest of the paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 presents existing research on the relationship between CEOs’ profiles and MFIs’ performance, while Sect. 3 lays out the theory and hypotheses we set out to test. Next, in Sect. 4, we present the data and methodology followed by Sect. 5 where we present descriptive statistics. Section 6 presents and discusses the results, and Sect. 7 concludes with theoretical and practical implications of this study.

2 Chief executive officers and MFIs’ performance

Over the last years, the microfinance industry has come under attack. In particular, the high interest rates often reaching 50% per annum and sometimes passing 100% have been criticised and considered one of the reasons why researchers struggle to identify strong evidence for a positive client impact from borrowing small amounts of money (Banerjee et al., 2015). As a consequence, there is now increased understanding of the importance of identifying factors that can improve MFIs’ efficiency and performance (Mersland and Strøm, 2010).

This paper falls into this stream of literature where searching for factors that may influence MFIs’ performance is core. In particular, researchers have tested the influence of governance on MFIs’ performance but they have generally struggled to identify coherent relationships (Hartarska, 2005; Mersland and Strøm, 2009). A few recent papers have shifted focus from governance to management and have come up with interesting results, indicating that an MFI’s performance seems to be significantly influenced by the CEO’s knowledge, background and profile. For example, Galema et al. (2012) investigated the influence of a powerful CEO, operationalised as a CEO combining the role of being the MFI’s board president/chair. The findings indicate that MFIs, particularly non-profit MFIs, with more powerful CEOs, are more likely to record poor performance. Another example is Strøm et al. (2014), who examined the influence of the CEO’s gender on an MFI’s performance. The results show that MFIs in which the CEO is female achieve better performance. They argue that the improved performance of MFIs in which the CEO is female is probably related to the focus on targeting female clients in microfinance.

Likewise, Périlleux and Szafarz (2015) examined female leadership and social performance in microfinance cooperatives. They found that female managers reporting to male-dominated boards issue larger loan sizes than female managers reporting to female-dominated boards. The study by Hartarska (2005), which is a corporate-governance study, also includes the CEO’s experience as an explanatory variable. She found that there is a positive relationship between the CEO’s years of experience and the MFI’s financial performance. Finally, Randøy et al. (2015) found that MFIs in which the CEO is also the founder of the MFI achieve better performance, both socially and financially, than MFIs managed by hired CEOs. Thus, they argue that CEOs who are also founders are intrinsically motivated to fulfil the organisation’s mission.

With this background, we find it interesting to further deepen our understanding of how the CEO, in this case his/her educational background, may influence an MFI’s performance. Moreover, this study is relevant not only for the microfinance industry but also for the rapid growing phenomenon of ‘hybrid organisations’. In a type of business that is aimed at pursuing social performance alongside financial performance, it is not obvious how CEOs with a business education will balance the conflicting goals.

3 Theoretical background and hypotheses

Recent research on MFIs indicates that human resources have a great influence on how the organisations pursues and balances the banking logic and development logic (Battilana and Dorado, 2010). Nevertheless, thus far, there has been no literature on how resource endowments like the CEO’s business education influences MFIs’ performance. The CEO’s business education represents a resource endowment in the form of human capital (Barney, 1991; Lindorff and Jonson, 2013; Soriano and Castrogiovanni, 2012). It may differentiate one organisation’s competitivenessFootnote 1 from another in terms of knowledge, skills and abilities (Baptista et al., 2014; Boone and van Witteloostuijn, 1996; Watson et al., 2003).

Boards of MFIs should, therefore, be concerned with the type of education a candidate should have when looking to replace a CEO (Hoffman et al., 2004; Kaplan et al., 2012). The boards may be inclined to follow, for example, Ghoshal (2005) suggestion that CEOs with a business education are primarily concerned about financial profits. Hence, these CEOs may put less effort into implementing the development logic of the organisation. There is, however, a stream of empirical research that refutes such claims, because business education is also supposed to instil moral reasoning in the individual. It suggests that a CEO with a business education may well implement the MFI development logic because business education knowledge induces altruistic behaviour (Francois, 2000; Neubaum et al., 2009).

Furthermore, proponents of normative isomorphism from the institutional theory, e.g. Dimaggio and Powell (1983, pp. 152–153), suggest that hiring and socialisation induce the commitment of employees to the organisation’s mission. Hence, we argue that business education could nurture altruistic behaviour, which is having a basic understanding of the complexity of transactions between stakeholders and the environment in which the organisation operates (Finkelstein, 1992; Neubaum et al., 2009). Subsequently, it influences the CEO’s strategic choices through her/his ability to apply competencies that result not only in economic benefits for the firms they manage but also in sustaining social development.

However, whether a CEO with a business education determines the better or worse performance of a hybrid organisation—in this case an MFI—is an unanswered question and deserves to be studied. In particular, the hiring of CEOs stands out as one of the most decisive issues when it comes to meeting the objectives of both financial sustainability and having a social mission. This paper is thus an empirical response to Battilana and Dorado (2010) who, based on two case studies, claim that the profile of top managers to a large extent decides whether an MFI manages to balance the two institutional logics. Using business education as a profile for CEOs, this paper also responds to documented challenges that MFIs face when it comes to balancing the two institutional logics (Hermes and Lensink, 2007).

Existing empirical research on small private firms and publicly traded firms have generally found a positive financial effect of having a business-educated CEO. For example, mutual funds managed by CEOs with business education are operated efficiently and achieve superior performance (Golec, 1996; Gottesman and Morey, 2006). Likewise, Bertrand and Schoar (2003) found evidence that managers of large publicly traded organisations in the USA with business education achieve a high return on assets, and the profitability and productivity of small and medium enterprises increase when the CEO has acquired a business education (Soriano and Castrogiovanni, 2012).

On the other hand, Henle (2006) found that business education enhances the understanding of ethical considerations that need to be incorporated when making strategic decisions. The ethical considerations may well apply to the development logic of MFIs. Lewis et al. (2014) examined CEOs’ degrees (e.g. MBA) and organisations’ compliance with environmental disclosure. Their findings indicate that firms managed by CEOs with a business education comply, largely, with the institutional pressure of environmental disclosure. Although Ghoshal (2005) claims that CEOs with a business education are primarily concerned about financial profits, recent empirical evidence found that firms in which the CEO has a business education implement activities that are not only financially beneficial to the firm but are also socially responsible (Slater and Dixon-Fowler, 2010). Moreover, Neubaum et al. (2009) show that having a business education induces moral reasoning that could promote the altruistic behaviour (Francois, 2000 ) of the individual, which should be positive for the social development mission of the MFI. Following the theoretical and empirical discussion in the previous sections we, therefore, hypothesise that:

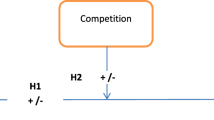

Hypothesis 1

MFIs managed by CEOs with a business education achieve better financial performance than MFIs managed by CEOs without a business education.

Hypothesis 2

MFIs managed by CEOs with a business education achieve better social performance than MFIs managed by CEOs without a business education.

4 Data and methodology

4.1 Data

The dataset applied is an extended version of the one used by Randøy et al. (2015). The sample consists of data from publically available MFIs’ rating reports between 1996 and 2011. The data exclude some of the largest commercial MFIs that are typically rated by traditional rating agencies like Standard & Poor (S&P) or Moody. Consequently, we restrict MFIs to those rated by the top five rating agencies specialised in microfinance, namely MicroRate, Microfinanza, Planet Rating, Crisil and M-Cril. Their assessment reports are available on the rating agencies’ websites or other websites such as www.ratingfund2.org. The Rating Fund of the Consultative Group to Assist the Poor (CGAP) has approved the rating agencies. The rating reports contain information about the MFI and its governance, management, financial profile and operations. The final sample includes 353 MFIs from 76 countries that have all willingly chosen to become rated.

4.2 Measurement of variables

4.2.1 Dependent variables

The literature on MFIs applies two logics to assess performance; first, financial performance that encompasses the banking logic and second social performance that assesses the development logic. Table 1 presents the dependent variables and their definitions. The variables are those typically included in empirical microfinance research (Cull et al., 2007; Hermes et al., 2011; Randøy et al., 2015; Strøm et al., 2014). The return on assets (ROA) indicates an MFI’s bottom-line performance. In microfinance, ROA is often considered a better proxy than the return on equity (ROE), since debt leverage levels vary considerably across MFIs. Nevertheless, as a robustness check we also include the ROE.

Another important financial performance variable is loan default. After all, microfinance became an alternative to public credit schemes in the 1950–1970s, when default rates of 50% or more were common (Hulme and Mosley, 1996). Mersland and Strøm (2010) argue that controlling operational costs should be core in the management of MFIs. Thus, we include the operational costs ratio as well as the personnel expense variable. We also include the MFI’s financial expense ratio. Furthermore, we apply a logarithm transformation to the personnel costs and loan defaults because their residuals are right skewed (MacKinnon and Magee, 1990; Zarembka, 1990).

Table 1 further lists our social performance proxies. The most used social performance measurement in microfinance research is average loan size (Ahlin et al., 2011; Cull et al., 2007; Mersland and Strøm, 2009).

Although researchers are well aware that some MFIs combine larger loans with smaller loans, thereby increasing their average loan sizes (Armendáriz and Szafarz, 2011), it is still considered the best available proxy because the MFI that offers smaller loans is on average assumed to reach poorer clients, since they cannot afford large loans. Moreover, average loan size is the most used social performance benchmark monitored by social investors in microfinance (Mersland and Strøm, 2010).

In addition to reaching as many poor clients as possible, often called depth of outreach, the development logic in microfinance also has a ‘breadth of outreach’ dimension. A socially oriented MFI should serve as many clients as possible. Thus, we use growth in total number of clients as our second social performance proxy. To test the robustness of our results, we also include outreach to women (D’espallier et al., 2013; Gutiérrez-Nieto et al., 2009) and total number of credit clients (Randøy et al., 2015) as additional proxies for social performance.

Next, Table 2 presents the independent and control variables. To measure the independent variable, we extract from the rating reports information about the type of education of the CEO. Although information about the education type of the CEO in the rating report is not mandatory, the rating agencies report education type when the CEO has a university degree. Hence, the independent variable is a dummy variable, indicating one if the CEO has the minimum of a 3-year university degree in business or banking-related field, and zero if otherwise. We call this business education. In the rating reports, the zero categories (the non-business education CEOs) normally have a university degree but not in the field of business. Furthermore, rating reports that did not contain information about the CEOs’ education were not included in the dataset. Generally, there was no clear pattern for rating agencies to include or not include information about the CEOs’ education in their reports, and so included rating reports in the dataset seemed random.

We include sets of control variables and follow the procedure of applying a logarithmic transformation to any variable that is right skewed (Box and Cox, 1964; Emerson and Stoto, 1983). We include board size, a control variable commonly applied in microfinance research (Galema et al., 2012). We control for economies of scale in MFIs using MFI size (measured as the natural logarithm of total assets) (Hartarska et al., 2013). We include CEO tenure. The tenure of the CEO is important because experience can probably offset educational background. We apply a self-constructed index based on information in the rating report, indicating, on a 1–7 scale, the level of market competition the MFI is facing to control for competition. We control for ownership form with a dummy variable indicating one if the MFI is owned by shareholders, and zero if otherwise. We follow Gottesman and Morey (2010) who included leverage and liquidity when they studied the relationship between the CEO’s educational background and the firm’s performance. We control for banking regulations with a dummy variable indicating one if the MFI is regulated by local banking authorities or zero if otherwise. Lastly, because we apply a global dataset, we control for macroeconomic factors using the Human Development Index (HDI), which ranks countries according to their health, education and income levels. Furthermore, we include regional control variables (omitting Africa as the reference category), rating agency indicators (excluding one agency; M-cril) and year indicators. Table 2 presents the independent and control variables and their definitions.

4.3 Method

We assume that an individual CEO at particular time t works in a specific MFI i. However, we understand that this assumption is too simple, as a CEO in a specific MFI i may influence its performance based on the strategic decisions made by a predecessor CEO in time t-1. In this section we address this issue as well as other sources of endogeneity using the instrumental variables approach.

The presence of a CEO with business education in an MFI may be a potential source of endogeneity. An MFI that performed well in the past performance could retain the current CEO with business education, or one that performed strongly could attract a candidate with business education to apply for the CEO position. This suggests the reverse causality in the CEO-performance relationship, and so interpreting the results becomes more challenging. To consider this, we use the instrumental variables (IV) approach.

We follow Randøy et al. (2015) procedure to document the CEO’s business education using a time variable, MFI age. Concerning the IV conditions, first, one cannot associate current MFI performance with MFI age. Therefore, the instrument is exogenous as the number of years of operating as an MFI is not likely to have a direct influence on MFI performance (Randøy et al., 2015).Footnote 2 Second, we expect a positive correlation between the respective instrument and the CEO’s business education, because as the MFI get older, the more their business becomes specialised and larger, and so it is more likely to hire a CEO with business education. Accordingly, the CEO with business education in this setting is an endogenous variable.

The endogenous explanatory variable of the CEO’s business education has a value of one if the CEO has a university degree in business education and zero if otherwise. The dummy independent variable of the CEO’s business education requires us to apply Heckman’s dummy endogenous explanatory variable (Heckman, 1978). In the following section, we develop a model that addresses the problem of endogeneity in the relationship between a CEO’s business education and the MFI’s performance.

4.3.1 Model estimation

As noted in the previous discussion, the educated in business CEO (EBCEO) is endogenous. We can remove the endogeneity problem if we find an appropriate instrument for EBCEO. Accordingly, we can infer a causal relationship between the presence of the CEO with business education and the performance of MFI. To account for the endogeneity of EBCEO, we apply the Heckman (1978) dummy endogenous variable estimation. To implement the dummy endogenous model, Wooldridge (2010) outlines IV regression procedures that involve instrument generation. Hence, we estimate the following model;

Using generated IV from;

Whereas;

- y i :

-

Represents the financial and social performance dependent variables

- EBCEO:

-

Represents the endogenous explanatory variable

- Controls:

-

Represents board size, MFI size, CEO tenure, competition, ownership type, leverage, liquidity, regulations, human development index, regional dummies, agency indicators and year indicators.

- ξ :

-

Is the natural logarithm of MFI age (Randøy et al., 2015).

According to Wooldridge (2010), Ζ is the generated instrument. To obtain the generated instrument Z, Wooldridge (2010) recommends the following steps. The first step is to form a conditional probability as follows.

Note: The control variables in the conditional probability equation include all variables except firm size. We run the following logit regression model:

From the logit regression, we obtain the fitted values and use them in the instrumental variable regression (Wooldridge, 2010, p. 939). This procedure of estimating the model P(EBCEO) is robust as there is no need to correctly specify the model, because it is a linear projection that we need. The second step is to estimate Eq. (1) with the instrumental variable method using generated instrument Z for EBCEO. Although Randøy et al. (2015) follow a similar procedure, the difference is that the endogenous variable is the entrepreneur CEO, while this study has education in business CEO as the endogenous variable.

The binary nature of some of the variables, for example EBCEO, restricts us to using random effects instrumental variable models (Wooldridge, 2010). The fixed-effect instrumental variable model is not an option in this case because the binary variables drop away in the fixed-effect model during transformation.

Furthermore, the validity of the IV requires non-correlation with the random error term u. Likewise, the IV should have a non-zero coefficient, that is, it should be partially correlated with the instrumented endogenous explanatory variable once other explanatory exogenous variables are netted out (Wooldridge, 2010). The exogenous explanatory control variables include board size, MFI size, CEO tenure, competition, ownership type, leverage, liquidity, regulations, HDI, regional dummies, agency indicators and year indicators. We test this assumption using the Wald test, a procedure outlined by Wooldridge (2010, pp. 352–353).

5 Descriptive statistics

Table 3 reports descriptive statistics for the variables included in the study. ROA is 2% and ROE 8%, illustrating that on average MFIs are financially sustainable, although they generally do not make much of a profit. On average, the operating expense ratio in the sample is 28%, and the average annual cost per staff member is US$3765. Financial expenses on average make up 3% of the loan portfolio, indicating that MFIs are still mainly funded by equity or subsidised loans (Mersland and Urgeghe, 2013). The portfolio at risk for loans overdue for more than 30 days is 6%, indicating that microfinance clients tend to repay their loans on time. The average loan size is US$820 and 63% of the clients are female, illustrating the ‘micro’-aspect and the focus on women in microfinance. The typical MFI serves 17,062 credit clients.

While many may think that a banking business like microfinance will be managed by CEOs with a business education, Table 3 indicates that only around 55% of the MFIs have a CEO with a business-related university degree. Compared with regular banking, this is a low percentage (Göhlmann and Vaubel, 2007). This illustrates that hybrid organisations, in this case MFIs, do not necessarily follow traditional business patterns when hiring their CEOs, further illustrating the importance of this paper.

The CEO has been in the position for approximately 6 years, and 34% of MFIs are owned by shareholders (the remainder are either member-based cooperatives or Non-Governmental Organisations). An MFI board, in average, is composed of seven members, and the average total assets of an MFI are approximately US$12 million. The 67% leverage ratio illustrates that MFIs on average still do not mirror banks, i.e. they do not mainly intermediate other people’s money. Nevertheless, the ratio reflects that MFIs do access and need external financing to fund their loan portfolios. Liquidity (cash and short-term investment) consists of 16% of total assets. The self-composed competition index, based on information in the rating reports, has a score of 4.43 on a scale of one to seven, signalling that MFIs are now increasingly competing against each other. The sample indicates that 31% of the MFIs are regulated by national banking authorities. On a scale of zero to one, the average human development index for the countries where MFIs operate is 0.61. Most of the MFIs in the sample are located in Latin America and the Caribbean (39%), while 24% are located in Africa, 18% in Eastern Europe and Central Asia, 9% are located in South Asia, 6% in East Asia and the Pacific and lastly 4% are located in the Middle East and North Africa.

In Table 4, the highest correlation is between shareholders firm and regulations (0.52). This is considered a low level and should not pose a problem in our estimations (Hair et al., 2010). Likewise, the results from Multicollinearity Diagnostic Criteria indicate that 2.58 is the highest variance inflation factor (results not reported) against a cut-off point of 10, which rules out the possibility of multicollinearity. The correlation between the CEO with business education and CEO tenure is low (−0.06), showing that these aspects measure different aspects of CEO characteristics.

6 Results and discussion

6.1 Are MFIs with business-educated CEOs different?

The mean comparison t test (Table 5) provides initial evidence for the relationship between the CEO with business education and the MFI’s performance. Interestingly, Table 5 indicates that MFIs in which the CEO has a business education has a significantly higher mean of return on assets. Table 5 also shows a significantly higher mean on return on equity for MFIs in which the CEO has a business education than MFIs in which the CEO has no business education. Moreover, the results of all the other financial performance indicators indicate that having a CEO with a business education is positive for the MFI. The operational costs ratio, personnel expenses ratio, financial expense ratio and portfolio at risk ratio consistently and significantly demonstrates that MFIs managed by a CEO with a business education perform financially better than MFIs managed by a CEO without a business education. Thus, these initial t tests give reason to believe that the type of education has an influence on an MFI’s financial performance.

When it comes to social performance, Table 5 further shows that MFIs managed by business-educated CEOs reach poorer clients (lower average loan sizes) and more credit clients than MFIs managed by CEOs without a business education. The two categories of CEOs seem to be equal when it comes to their focus on female clients, while MFIs managed by CEOs without a business education obtain higher growth rates than MFIs managed by business-educated CEO. This latter finding is interesting since growth can also be considered a risk proxy, and from this perspective, CEOs with a business education seem to be more prudent.

6.2 Instrument generation

To implement the Heckman (1978) model, we first run the random effects logit model (Eq. 2). Second, we generate the instrument by forming a fitted probability to obtain the instrument Z. Third, we run a random effects instrument variable (IV) regression using Eq. 1. Table 6 presents the random effects logit regression. The results in Table 6 show that the coefficient on the time variable (MFI age) is positive and significantly related to whether the MFI is managed by a CEO with a business education.

6.3 Business-educated CEOs and MFIs’ financial performance

Table 7 reports the random effects IV regression for the effect of CEO business education on ROA and ROE. The effect of CEO business education on both the ROA and ROE is positive and significant (models 1 and 2). This is in line with Bertrand and Schoar (2003), who found that firms in which the CEO has a business education are associated with improved financial performance. In Table 7, we further observe that the larger the MFI is, the better its performance, which is in line with Hartarska et al. (2013).

We also notice that being regulated has a positive influence on the ROA and ROE, while high liquidity ratios will naturally drive down the performance of the MFI. It is also interesting to see that MFIs operating in more developed markets (HDI) obtain better results. Hence, although microfinance is a banking model tailored for less-developed markets, the business model works better, in terms of financial performance, when operating in more developed settings.

The ROA and ROE are composite measures often referred to as bottom-line performance. It is therefore interesting to look more closely into the aspects of performance where education may actually have an effect. Are CEOs with a business education better at obtaining cheaper funding and improved repayment or do they achieve higher efficiency? Thus, in Table 7, we also report the random effects IV regression for the effects of CEO business education on several cost variables that all have an influence on an MFI’s bottom-line performance. Interestingly, the results indicate that having a business education is associated with improved performance on all the tested cost variables. Compared with MFIs managed by CEOs without a business education, MFIs managed by business-educated CEOs have significantly lower operational costs, lower personnel costs, lower funding costs and lower loan losses (par30). Thus, taken together, the evidence is clear that having a CEO with a business education has a positive effect on all the aspects of an MFI’s financial performance.

6.4 Business-educated CEO and MFI’s social performance

While the evidence seems clear when it comes to the effect of business education on an MFI’s financial performance, we now turn to the MFI’s social performance. Table 8 reports the results of the random effects IV regressions for the effect of the CEO with a business education and other control variables on an MFI’s social performance. First, we observe that the relationship between the CEO with a business education and average loan size, the most used proxy for social performance in microfinance research, is negative and significant. The result is in line with the claim that managers in MFIs care about serving poor clients with smaller average loan sizes because this social performance metric is normally used by stakeholders to assess the extent to which a particular MFI fulfils its social mission objective (D’Espallier et al., 2016).

Second, the effect of a CEO with a business education on the percentage of female clients is positive but not significant. The results suggest that MFIs which have business-educated CEOs do not necessarily serve more female clients. As a social performance metric, reaching out to more female clients is an important empowerment objective for most MFIs. However, when female clients represent a clear majority of customers, an even higher percentage may not reflect the social performance accomplishment (Mersland et al., 2013). Hence, it might be that the business-educated CEO is a bit more pragmatic when it comes to the share of portfolio allocated to female clients, because a further increase in this share might not necessarily be beneficial for the institution (Mersland et al., 2013).

Although the effect of CEOs with a business education on the growth in total clients’ base is positive, as expected, though not significant, its effect on total number of credit clients is positive and significant. The non-significant result of the growth in total clients’ base suggests that business-educated CEOs hesitate to go for strong growth because of the risks related to such a strategy. Overall, the results on average loan size and total number of credit clients suggest that MFIs in which the CEO also has a business education cares about reaching more poor clients with small average loan sizes (D’Espallier et al., 2016).

The microfinance literature recognises that measuring the social performance of MFIs is challenging, and in particular, average loan size should be used with care (Armendáriz and Szafarz, 2011). Thus recently, other metrics such as interest rate on loans charged to borrowers add to the understanding of whether a particular MFI is performing well socially (Ghosh, 2011). Therefore, in unreported results, we proxy interest rates with portfolio yield and find positive effects on portfolio yield of MFIs in which the CEO has a business education. Generally, the result suggests that MFIs with CEOs with a business education could receive more in interest payments when serving poor borrowers with small average loan sizes. The overall results on social performance are therefore not as strong as for financial performance.Footnote 3

We also run a set of additional unreported checks to see if both our financial and social performance results are robust. First, in each model, we include subsidies measured as donated equity/total equity (D’Espallier et al., 2016). Secondly, we included a dummy for whether the CEO had prior experience in business and/or banking as an additional control variable. A third check was done by adding an interaction variable of CEO business education with a large board because large boards mitigate agency costs in complex organisations like MFIs with competing logics (Galema et al., 2012). Lastly, a robustness check was done using an interaction variable of CEO business education with geographical regions as additional control variables. None of these alternative model specifications renders results that alter our former conclusions.Footnote 4

7 Conclusions

The microfinance industry is still young, and many MFIs are still managed by their founders (Randøy et al., 2015). In the years to come, many MFIs will replace their CEOs. At the same time, the industry struggles with relatively poor performance and high operational costs (Mersland and Strøm, 2012). Studies searching for a relationship between the profile of the CEO and the MFI’s performance, like this study, should therefore be relevant and in high demand. Moreover, MFIs are typical examples of hybrid organisations pursuing social objectives alongside financial objectives. In such organisations, it is not necessarily clear that typical business managers, i.e. those having a business education, will outperform managers with a different educational background. As far as we know, our study is the first to test whether having a business education is of benefit when managing hybrid organisations.

An interesting finding in itself in our dataset is that only 55% of the MFIs in the sample are actually managed by CEOs with a business education. This is a much lower percentage than that found in traditional banking, and it illustrates that boards in hybrid organisations, in this case MFIs, seem to consider a wider set of expertise when hiring their CEOs.

Using an unbalanced panel dataset covering 16 years and including 353 MFIs from across the globe, we tested for the relationship between MFIs’ performance and the educational background of their CEOs. Because of the reversed causality problem, we applied the instrument variable random effects regression method in our analysis. To develop our hypotheses, we drew on existing literature and the resource-based view and institutional theories. Thus, we hypothesised that having a business education should have a positive effect on both the financial and social performance of the MFI.

Our findings clearly support our hypotheses. MFIs managed by CEOs with a business education have a significantly better financial performance and also a better social performance than MFIs managed by CEOs with different educational backgrounds. Our findings are robust for all the tested financial performance proxies, namely ROA, ROE, operational costs, personnel costs, funding costs and default ratios. As for social performance, our findings are significant for average loan size and number of credit clients served. Taken together, the MFI benefits from having a CEO with a business education. In line with theory and former evidence on the effects of having a business education, we suggest that better performance is a result of the CEO’s ability to make better strategic choices and induce moral reasoning in the organisation. Our results support the literature that claims that business education creates profit-minded CEOs (Bertrand and Schoar, 2003; Ghoshal, 2005), who are also able to pursue social objectives (Slater and Dixon-Fowler, 2010). Our study is thus in line with several empirical studies upholding the importance of business education for those in managerial positions (Hansen et al., 2010; Terjesen and Willis, 2016).

When boards hire CEOs, they take, of course, much more into account than simply the educational background of the candidate. Networks, personality, experience and many other kinds of expertise are evaluated together with the candidate’s education. Nevertheless, it must be relevant for boards of hybrid organisations to know that hiring CEOs with a business education will, on average, enhance not only their financial performance but also give them the potential to have a positive influence on their social performance. Our study should therefore be of practical importance for MFIs in particular and hybrid organisations in general. Furthermore, as noted by Stuart (2011), MFIs interested in serving more clients, i.e. being more social, need to be profitable in order to attract investors.

Several microfinance industry reports have highlighted the risks in the industry relating to the often poorly qualified human resources operating MFIs, and, in particular, the thin labour market for top-level managers (CSFI, 2011, 2014). A reason for the thin labour market for managers is maybe because the boards of MFIs fear for their social mission if they were to hire bankers and candidates with a business background. We suggest that our study should motivate MFIs and their boards to increasingly search for candidates from traditional banks and businesses when hiring new managers.

In this study, we measure CEO business education as a formal university degree in fields like accounting, management, economics, banking or MBA. Such a proxy is relevant, although it has its limitations. For example, it may not well capture CEOs’ ability that may drive their desire for achievement (Pfeffer, 1992). Thus, our investigation focuses only on the general dimension of CEO business education; we do not claim that all types of business education are equally associated with better MFI performance. Equally, we do not differentiate between the various levels (undergraduate or postgraduate) achieved by the CEO in business education and the quality of business school the CEO attended, so future studies could look into a more disentangled operationalisation of the CEO business education (Gottesman and Morey, 2006). The operationalisation of business education in our study also has a limitation because our dataset does not allow us to differentiate between those CEOs who received their business education after working as CEOs and those who went direct to business school without prior work experience. We leave future studies to examine the moderating effects of the CEO’s prior work experience on the relationship between CEO business education and the performance of MFIs (Soriano and Castrogiovanni, 2012).

Moreover, although employees drawn to work in microfinance (e.g. CEOs) could be motivated by the organisations’ mission (Besley and Ghatak, 2005), the literature on traditional firms suggests a positive relationship between university/college degrees and wage levels (Cole and Mehran, 2016). Therefore, we leave future studies to examine whether there is a tradeoff between the CEO’s type of education and the CEO’s wage level as well as the overall wage level in the MFI (Kuhn and Weinberger, 2002). Similarly, what aspects of business education result in superior management skills and whether educational background influences altruistic behaviour are relevant research questions, both generally and specifically, for the microfinance industry (Besley and Ghatak, 2005; Francois, 2000; Hermes and Lensink, 2007; Neubaum et al., 2009). Finally, the fact that we use a global dataset is not only a benefit. Country studies comparing the microfinance industry with other local industries would be interesting. For example, such studies would reveal whether MFIs actually have fewer or more CEOs with a business education than NGOs, local banks or other local industries. Altogether, we think there is scope for much more research when it comes to the managerial parts of operating MFIs in particular and hybrid organisations in general.

Notes

Barney (1991) argues that the business education of a manager can be acquired in the market, and so it cannot represent a competitive advantage. However, the argument may not apply to this study since, obviously, some MFI boards opt to hire CEOs without a business education, and we therefore compare MFIs in which the CEO has a business education and those MFIs with CEOs without a business education.

Some may find it strange that the performance of the MFI is not influenced by the age of the MFI. However, in microfinance research, MFI experience is often included in empirical studies and researchers have not found a coherent significant relationship between the two (e.g. Hartarska, 2005; Mersland and Strøm, 2009). A reason for this might be because MFIs are often subsidized during their first years by donors (Hudon and Traca, 2011). As a robustness check, we have run the model with number of branch offices as an alternative instrument variable and the results remain the same as those reported using MFI age as an instrument.

The result on portfolio yield should be interpreted with care since default levels may perturbate the accounted yield making it less fit to proxy the interest rate charged by the MFI.

The results from the robustness checks are available from the authors upon request.

References

Ahlin, C., Lin, J., & Maio, M. (2011). Where does microfinance flourish? Microfinance institution performance in macroeconomic context. Journal of Development Economics, 95(2), 105–120.

Armendáriz, B., & Szafarz, A. (2011). On mission drift in microfinance institutions. In B. Armendariz & M. Labie (Eds.), The handbook of microfinance (pp. 341–366). Singapore: World scientific publishing Co. Pte. Ltd..

Banerjee, A., Karlan, D., & Zinman, J. (2015). Six randomized evaluations of microcredit: introduction and further steps. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 7(1), 1–21.

Baptista, R., Karaöz, M., & Mendonça, J. (2014). The impact of human capital on the early success of necessity versus opportunity-based entrepreneurs. Small Business Economics, 42(4), 831–847.

Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99.

Battilana, J., & Dorado, S. (2010). Building sustainable hybrid organizations: the case of commercial microfinance organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 53(6), 1419–1440.

Bertrand, M., & Schoar, A. (2003). Managing with style: the effect of managers on firm policies. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118(4), 1169–1208.

Besley, T., & Ghatak, M. (2005). Competition and incentives with motivated agents. American Economic Review, 95(3), 616–636.

Boone, C., & van Witteloostuijn, A. (1996). Industry competition and firm human capital. Small Business Economics, 8(5), 347–364.

Box, G. E. P., & Cox, D. R. (1964). An analysis of transformations. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series B (Methodological), 211–252.

Cole, R. A., & Mehran, H. (2016). What do we know about executive compensation at small privately held firms? Small Business Economics, 46(2), 215–237.

CSFI. (2011). Microfinance Banana Skins 2011: losing its fair dust (pp. 1–56).

CSFI. (2014). Microfinance Banana Skins 2014: facing reality. The CSFI Survey of Microfinance Risk (pp. 1–57).

Cull, R., Demirgüç-Kunt, A., & Morduch, J. (2007). Financial performance and outreach: a global analysis of leading microbanks. The Economic Journal, 117(517), 107–133.

Cull, R., Demirgüç-Kunt, A., & Morduch, J. (2014). Banks and microbanks. Journal of Financial Services Research, 46(1), 1–53.

D’espallier, B., Guerin, I., & Mersland, R. (2013). Focus on women in microfinance institutions. The Journal of Development Studies, 49(5), 589–608.

D’Espallier, B., Hudon, M., & Szafarz, A. (2016). Aid Volatility and Social Performance in Microfinance. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly.

Dimaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited—institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147–160.

Emerson, J. D., & Stoto, M. A. (1983). Transforming data. In D. C. Hoaglin, F. Mosteller & J. W. Tukey (Eds.), Understanding robust and exploratory data analysis (pp. 97–128). New York.

Finkelstein, S. (1992). Power in top management teams: dimensions, measurement, and validation. Academy of Management Journal, 35(3), 505–538.

Francois, P. (2000). ‘Public service motivation’ as an argument for government provision. Journal of Public Economics, 78(3), 275–299.

Galema, R., Lensink, R., & Mersland, R. (2012). Do powerful CEOs determine microfinance performance? Journal of Management Studies, 49(4), 718–742.

Ghosh, S. V. T. E. (2011). Microfinance and competition for external funding. Economics Letters, 112(2), 168–170.

Ghoshal, S. (2005). Bad management theories are destroying good management practices. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 4(1), 75–91.

Göhlmann, S., & Vaubel, R. (2007). The educational and occupational background of central bankers and its effect on inflation: an empirical analysis. European Economic Review, 51(4), 925–941.

Golec, J. H. (1996). The effects of mutual fund managers’ characteristics on their portfolio performance, risk and fees. Financial Services Review, 5(2), 133–147.

Gottesman, A. A., & Morey, M. R. (2006). Manager education and mutual fund performance. Journal of Empirical Finance, 13(2), 145–182.

Gottesman, A. A., & Morey, M. R. (2010). CEO educational background and firm financial performance. Journal of Applied Finance, 2, 70–82.

Gutiérrez-Nieto, B., Serrano-Cinca, C., & Molinero, C. M. (2009). Social efficiency in microfinance institutions. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 60(1), 104–119.

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis: a global perspective (7th ed.). Upper Saddle River, N.J: Pearson.

Hansen, M. T., Ibarra, H., Peyer, U., von Bernuth, N., & Escallon, C. (2010). The best-performing CEOs in the world. Harvard Business Review, 88(1/2), 104–113.

Hartarska, V. (2005). Governance and performance of microfinance institutions in central and eastern Europe and the newly independent states. World Development, 33(10), 1627–1643.

Hartarska, V., Shen, X., & Mersland, R. (2013). Scale economies and input price elasticities in microfinance institutions. Journal of Banking & Finance, 37(1), 118–131.

Heckman, J. J. (1978). Dummy endogenous variables in a simultaneous equation system. Econometrica, 46(4), 931–959.

Henle, C. A. (2006). Bad apples or bad barrels? A former CEO discusses the interplay of person and situation with implications for business education. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 5(3), 346–355.

Hermes, N., & Lensink, R. (2007). The empirics of microfinance: what do we know? Economic Journal, 117(517), F1–F10.

Hermes, N., Lensink, R., & Meesters, A. (2011). Outreach and efficiency of microfinance institutions. World Development, 39(6), 938–948.

Hoffman, J. J., Schniederjans, M. J., & Sebora, T. C. (2004). A multi-objective approach to CEO selection. Infor, 42(4), 237–255.

Hudon, M., & Traca, D. (2011). On the efficiency effects of subsidies in microfinance: an empirical inquiry. World Development, 39(6), 966–973.

Hulme, D., & Mosley, P. (1996). Finance against poverty (vol. 2). Psychology Press.

Kaplan, S. N., Klebanov, M. M., & Sorensen, M. (2012). Which CEO characteristics and abilities matter? The Journal of Finance, 67(3), 973–1007.

Kuhn, P., & Weinberger, C. J. (2002). Leadership skills and wages.

Lepoutre, J., Justo, R., Terjesen, S., & Bosma, N. (2013). Designing a global standardized methodology for measuring social entrepreneurship activity: the global entrepreneurship monitor social entrepreneurship study. Small Business Economics, 40(3), 693–714.

Lewis, B. W., Walls, J. L., & Dowell, G. W. S. (2014). Difference in degrees: CEO characteristics and firm environmental disclosure. Strategic Management Journal, 35(5), 712–722.

Lindorff, M., & Jonson, E. P. (2013). CEO business education and firm financial performance: a case for humility rather than hubris. Education and Training, 55(4), 461–477.

MacKinnon, J. G., & Magee, L. (1990). Transforming the dependent variable in regression models. International Economic Review, 315–339.

Mersland, R., D’espallier, B., & Supphellen, M. (2013). The effects of religion on development efforts: evidence from the microfinance industry and a research agenda. World Development, 41, 145–156.

Mersland, R., & Strøm, R. Ø. (2009). Performance and governance in microfinance institutions. Journal of Banking & Finance, 33(4), 662–669.

Mersland, R., & Strøm, R. Ø. (2010). Microfinance mission drift? World Development, 38(1), 28–36.

Mersland, R., & Strøm, R. Ø. (2012). The past and future of innovations in microfinance. In D. Cumming (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of entrepreneurial finance. USA: Oxford University Press.

Mersland, R., & Urgeghe, L. (2013). Performance and international investments in microfinance institutions. Strategic Change: Briefings in Entrepreneurial Finance, 22(1–2), 17–29.

Miller, T. L., Grimes, M. G., McMullen, J. S., & Vogus, T. J. (2012). Venturing for others with heart and head: how compassion encourages social entrepreneurship. Academy of Management Review, 37(4), 616–640.

Neubaum, D. O., Pagell, M., Drexler, J. J. A., McKee-Ryan, F. M., & Larson, E. (2009). Business education and its relationship to student personal moral philosophies and attitudes toward profits: an empirical response to critics. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 8(1), 9–24.

Périlleux, A., & Szafarz, A. (2015). Women leaders and social performance: evidence from financial cooperatives in Senegal. World Development, 74, 437–452.

Pfeffer, J. (1992). Understanding power in organizations. California Management Review, 34(2), 29–50.

Randøy, T., Strøm, R. Ø., & Mersland, R. (2015). The impact of entrepreneur-CEOs in microfinance institutions: a global survey. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 39(4), 927–953.

Slater, D. J., & Dixon-Fowler, H. R. (2010). The future of the planet in the hands of MBAs: an examination of CEO MBA education and corporate environmental performance. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 9(3), 429–441.

Soriano, D. R., & Castrogiovanni, G. J. (2012). The impact of education, experience and inner circle advisors on SME performance: insights from a study of public development centers. Small Business Economics, 38(3), 333–349.

Strøm, R. Ø., D’Espallier, B., & Mersland, R. (2014). Female leadership, performance, and governance in microfinance institutions. Journal of Banking & Finance, 42, 60–75.

Stuart, G. (2011). Micorfinance—a strategic management framework. In B. L. Armendariz, Marc (Ed.), The Handbook of Microfinance (pp. 251–266). Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd.

Terjesen, S., & Willis, A. (2016). Experimental economics and business education: an interview with Nobel laureate Vernon Lomax Smith. Small Business Economics, 47(1), 261–275.

Watson, W., Stewart, W. H., & BarNir, A. (2003). The effects of human capital, organizational demography, and interpersonal processes on venture partner perceptions of firm profit and growth. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(2), 145–164.

Wittmer, D. (1991). Serving the people or serving for pay: reward preferences among government, hybrid sector, and business managers. Public Productivity & Management Review, 14(4), 369–383.

Wooldridge, J. M. (2010). Econometric analysis of cross section and panel data (2 ed.). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Zarembka, P. (1990). Transformation of variables in econometrics. Springer.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank participants at the CERMi research day 24th May 2014 at the University of Mons, Belgium; the 55th Annual Meeting of the Academy of International Business, 3rd–6th July 2013 Istanbul, Turkey; the third European Research Conference on Microfinance 10th–12th June 2013 Kristiansand, Norway; the 5th International Research Workshop on Microfinance Management and Governance, 18th–19th October 2012, Oslo, Norway; and the NFB-PhD research network conference 16th–17th August 2012, Kristiansand, Norway.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pascal, D., Mersland, R. & Mori, N. The influence of the CEO’s business education on the performance of hybrid organizations: the case of the global microfinance industry. Small Bus Econ 49, 339–354 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-016-9824-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-016-9824-8