Abstract

Are smaller firms more productive? Intuitively, while small firms have the advantage of more flexible management and lower response time to market changes, larger firms have the advantages of economies of scale, political clout and better access to government credits, contracts and licenses, particularly in developing countries. Using a panel dataset from a commercially available database of financial statements of manufacturing firms in India, we find that firms in the lowest quintile of the asset distribution that invest in research and have better liquidity are most productive. The Indian manufacturing sector, characterized by both large scale public and private firms as well as numerous smaller firms, provides an ideal setting. Our findings are robust to alternative definitions of size, alternative estimation methods and alternative estimates of total factor productivity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Should governments in developing countries protect and promote small firms or incentivize large firms? Principles of economics teach us that larger firms may benefit from economies of scale, but may suffer from inflexible and complex management. The trade-off is more complicated in developing countries characterized often by underdeveloped credit markets and corrupt bureaucratic systems like licensing. In addition to the above, small firms typically suffer from lower access to credit and necessary political clout to influence policy (Tybout 2000). Though there is evidence in the US that smaller firms generate more patents per capita, and have more flexible management style and agility to adapt to technology changes (Dhawan 2001), evidence is scant in developing countries except for a handful of studies like Bigsten and Gebreeyesus (2007).

Policymakers recognize these uneven playing fields, and economic policies around the developing world often offer incentives and protection to firms under certain threshold sizes. However, effects of such policies on aggregate productivity cannot be known unless we know if smaller firms are more productive than their larger counterparts. Therefore, size-productivity relationship at the micro level has implications for overall industry productivity, particularly in the background of these policies that often focus on threshold sizes. If small firms are more productive, these policy incentives are likely to enhance overall productivity in the host industry.

Using a large panel of Indian firms that report balance sheet information, we estimate and compare total factor productivities of large and small firms for the 1994–2008 period. Total factor productivity (henceforth, TFP), or the amount of output that is not explained by the amounts of inputs, has been identified as a key variable in explaining the heterogeneous growth performance of developing countries (Klenow and Rodriguez-Clare 1997; Hall and Jones 1999). We perform the following exercise—we divide firms in an industry into five asset quintiles and examine if the firms in the lowest quintile, the smallest ones, are more productive than their larger counterparts. We have defined size in terms of asset holdings of a firm and not in terms of employment, a more common measure. We use asset size because of lack of employment data and the fact that the official definition of firm size in India is asset-based and not employment-based.

Our main finding is that smaller firms, particularly firms in the lowest asset percentile, are more productive than the rest. This result is robust to a variety of alternative definitions of size and productivity such as using a different estimation method for TFP, using all five asset classes instead of two, and using a continuous measure of size—market share. Additionally, and somewhat puzzlingly, we find that small productive firms do not seem to grow and claim more resources to even become medium size firms. The issue of life-cycle growth of firms is beyond the scope of this paper; however, our finding is in line with other recent independent evidence such as Hsieh and Klenow (2012) who find that older and more mature Indian firms do not grow in terms of employment or output.

A second key finding is that productivity is dependent on both healthy cash flow and the propensity to invest in research and development; smaller firms that invest in research and development and/or have a healthy cash flow are more productive. This confirms the theoretical assertion later that smaller firms can be more productive if they can leverage their advantage of having flexible management and overcome liquidity constraints.

Identification is based on a combination of strategies. First, we argue that there is little inter-asset-size mobility for firms in India in the sense that only a handful of firms in the lowest quintile have moved to upper quintiles in the post-reform period. This phenomenon is not limited to our data, it is present in Indian manufacturing in general as argued above. Therefore, it is unlikely that a firm’s current or past productivity would affect its size. Second, we use industry and year fixed effects to purge our estimates of confounding time-invariant unobservable variables at various levels.

There are several reasons why a firm’s size may be instrumental in explaining its performance. Intuitively, there is a trade-off between growing bigger and gaining productivity. While small firms have the advantage of smaller and more flexible management and lower response time to market changes, larger firms can reap the benefits of economies of scale, particularly in some industries like the automobile industry. Larger firms also wield political clout and garner better access to government credits, contracts and licenses. This is especially true for developing countries. Even private financial institutions are likely to favor big firms for the latter’s better liquidity and more stable operations.

Finally, this polemic has become particularly important in the last decade or so for two more reasons. A number of economies including India have liberalized their trade and licensing regimes to allow easy entry of firms and to reduce monopolies of big private or state-owned firms. Second, much richer micro-datasets are increasingly available to empirically assess the dynamic changes in productivity.Footnote 1

The rest of the paper proceeds as follows. In the next section, we discuss the characteristics and a brief history of small scale industries in India. In Sects. 3 and 4, we discuss the theoretical underpinnings of our empirical strategy and review the empirical literature on size-productivity relationship, respectively. Section 5 discusses data with some of the details being relegated to the Appendices. The remaining sections are devoted to empirical specification, estimation and discussion of results along with some major caveats. We conclude with a brief discussion of the policy implications of our findings.

2 Background: small enterprises in India

Small and medium enterprises play an important role in economic growth by contributing to the GDP (Beck et al. 2005). In India, classification of firms by size is based on a firm’s asset size (unlike in the US and EU where it depends on employment). According to the Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises Development Act of 2006 ratified by the Government of India, micro, small and medium enterprises are defined as the production units where the investment in plant and machinery does not exceed 2.5 million rupees, 50 million rupees and 100 million rupees respectively ($1 = 50 INR approximately). This is subject to the condition that the unit is not owned, controlled or a subsidiary of any other undertaking. A set of small firms do not report their balance sheets and hence become part of the “unorganized sector” in official classification. These firms are not included in our study as the balance sheet-based database we use does not capture them.Footnote 2

Among the Asian countries, India has been unique in terms of its focus on the development of small and medium enterprises since her independence in 1947. Post-independence, the industrial development strategy in India was to set up the core capital-intensive infrastructure industries accompanied by a number of small-scale labor intensive consumer goods manufacturers. These small firms were to be spread across the nation in rural and urban locations, which would not only increase employment opportunities, but also help in industrial dispersal.

By 2003–2004, the Small Scale Industry (SSI) units accounted for more than 40 % of gross value of output in the manufacturing sector and about 34 % of total exports. It is the highest employment-providing sector after the agricultural sector. Though 87 % of the SSI units are unregistered, the registered units account for 72 % of the total SSI production and 87 % of total SSI exports.Footnote 3

However, in spite of the policy rhetoric and 40 % contribution to gross value of output, small enterprises have been weighed down by inadequate working capital, delay in sanction of working capital, poor and obsolete technology, inadequate demand and other marketing problems and infrastructural constraints. The credit squeeze faced by the small firms is made worse by the central bank’s monetary sterilization policy. In order to hold on to its monetary target, the central bank tries to sterilize the increase in foreign direct investment and portfolio investment. This leads to a credit squeeze, which is distributed unevenly in the economy, with the small firms feeling the credit constraint more.Footnote 4

3 Theoretical priors

Even though small and medium enterprises are omnipresent in both the developing and developed world, the link between size and productivity has rarely been modeled at the firm level. Since theoretical priors are ambiguous for reasons discussed below, it essentially remains an empirical question that is likely to be resolved in the context of the relevant economies.

Large firms benefit from economies of scale. In developing countries, where institutions are typically weak, they also enjoy other benefits such as access to license, finance and government contracts. On the contrary, large firms can also be constrained by the complexity of management and their inflexibility to change. In one of the earliest papers, Williamson (1967) captured this trade-off in a model of hierarchical control, where the benefits of increasing returns from growing in size are countervailed by the increasing cost of managerial complexity. The models that followed built on this advantage of small firms—leaner and more flexible management. Further, small firms can be more receptive and adaptive to new technology. One advantage of having a smaller scale is that the production process is less deeply entrenched in existing technology. Dhawan (2001) provides an excellent summary of the theoretical arguments for small firms being more productive.

Jovanovic (1982) proposed an early theorization of small firms being more efficient. In his model, price-taking firms enter the industry knowing the distribution of cost, but ignorant about their individual draws. After the idiosyncratic efficiency draw is made, a firm discovers whether it is efficient enough to survive and grow or not. Firms with bad draws leave the industry, leaving more efficient firms to operate. As a result, in the observed data, small firms appear most efficient. However, this line of research focuses on entry, survival and growth of firms and not on the relationship of the size of firm and its total factor productivity.

Idson and Oi (1999) argue that workers in large firms reap the benefits of increasing returns (brought in by big volumes) by having less idled time and producing more. There is some related literature on Gibrat’s Law, which states that firms grow at rates that are independent of their sizes. However, there is no implication for productivity. Tybout (2000) also attributes the (potential) higher productivity of large firms in developing countries to variables like increasing returns and lobbying power.

There are two strands of related literature that emphasize a firm’s size in influencing variables that potentially affect productivity. The first is access to credit. Information asymmetries and underdeveloped financial markets, common in developing countries, limit small firms’ access to finance. In a firm-level survey of 54 countries Beck et al. (2005) found that financial, legal and corruption problems limit the growth of the small firms. This provides a channel through which size may matter for productivity. A second channel is the link between investment in research, innovation and productivity. While large firms are financially able to invest in research and development at a large scale, there is evidence that research investment by smaller firms is more efficient, for example, in terms of generation of number of patents.

4 Size-productivity relationship around the world

Empirical evidence on size-performance relationship too has been mixed. A summary of the extant literature is also complicated by the fact that a wide variety of measures of productivity and firm size have been used in the literature. For instance, the most popular metric of firm size has been employment, regardless of its output, asset or market share. Similarly, labor productivity has often been used instead of total factor productivity. Finally, apart from productivity, a variety of indicators of performance such as profit rate, employment, survival and growth have been used.

For firms in the United States, Dhawan (2001) found results that are largely similar to those of ours—smaller firms are more productive, but are less likely to survive compared to their larger counterparts. Baily et al. (1996) found that if we measure a firm’s size in terms of employment, then firms growing smaller (in other words, downsizing) did not gain productivity.

Size heterogeneity in developing countries too is a pervasive phenomenon. Industries within the manufacturing sectors in developing countries have been characterized by size-heterogeneity of such high degree that Tybout (2000) calls it a form of ‘dualism’. Unfortunately, the evidence in terms of size and performance in these countries is limited in nature. This is not surprising, because many developing countries either lack a significant manufacturing sector, or dependable data, or both. Fortunately, with both growth in industry and better data collection, new research is burgeoning.

In Asia, studying Taiwanese firms, Aw (2002) found that small firms are no less productive than their larger counterparts. In a related study, Aw et al. (2001) also found that small and medium size firms contribute a significant amount to the productivity growth of the industries they belong to. In Africa, analyzing manufacturing firms in nine African countries, Van Biesebroeck (2005) found that large firms are more productive and have higher growth rates. However, Bigsten and Gebreeyesus (2007) find that small firms in Ethiopia actually grow faster than the larger ones. All these papers use the employment definition of size. In the Indian context, Mazumdar (2009) finds an existence of a dualism in Indian firms. Employment is concentrated in the smallest and the largest firm size-groups. He also finds that the firms in the smallest size group are the least productive. He measures productivity as value-added per unit of labor and not total factor productivity and measures the size of firms in terms of employment.

As the policy to protect and promote small and medium enterprises in India is based on the asset size definition, it is important to study the relationship between firm productivity and firm size in the context of asset size. It is this gap in the literature that we address in this paper.

To summarize, we have the following testable hypotheses: (1) Ceteris paribus, small firms, appropriately defined, are more productive than their larger counterparts (i.e. after controlling for alternative explanations such as ownership, age, research and development), and (2) size-productivity relationship transmits through other variables such as research and development (henceforth R&D) and availability of liquidity in the form of cash and bank balances.

5 Data

The data used in this research has been procured from the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy’s (henceforth, CMIE) PROWESS database. CMIE compiles this data from the audited financial results of listed and unlisted firms. The firms in Prowess account for almost 75 % of all corporate taxes and over 95 % of excise duty collected by the Government of India.

We use an unbalanced panel data of manufacturing firms for the period 1994–2008. The choice of time period has been dictated by the intention to keep the most recent data and avoid having a sample including years containing too few firms. The number of firms covered in the PROWESS database has jumped steeply in 1994 and remained within the band of 10 % more or less until 2008.

The data has detailed information on financial and non-financial variables including assets, liabilities, income and expenses. All variables have been deflated by the wholesale price index. Since the database contains information on only the wage bill and not on employment, we infer the amount of labor by deflating the wage bill by average industry wages. The data on wage per worker has been taken from the Central Statistical Organization’s (CSO) Annual Survey of Industries (ASI) database.Footnote 5 The PROWESS data has firms from 22 NIC-2 digit industries. We were unable to identify the firms officially registered as small enterprises in our data. Consequently, we constructed this measure from the data.

For each industry and year, firms have been categorized into five quintiles according to their asset sizes. Therefore, each industry has its own size-distribution for each year. This makes the size variable comparable across industries and over time. Consequently, a firm is deemed to be small or large with reference to its peers not just within the industry, but also across the sector. A mining firm may belong to the lowest quintile within the mining industry, but a firm in the textile industry with the same value of assets may belong to a higher quintile. The variable SMALL is created as a binary variable that assumes value one if a firm belongs to the lowest quintile in its industry, that is, the lowest 20 % of the firms by asset size and zero otherwise.

We have also used a number of other variables in our empirical analysis. Table 1 summarizes them.

As mentioned earlier, the dataset is an unbalanced panel. For our main analysis, we tried to retain as much data as possible, so there is no active sample selection. Having cleaned the data and removed outliers, we were left with roughly 39,751 data points spanning 15 years and 16 industries. The details of variable construction and explanation are provided in the Appendix.

6 Empirical strategy

6.1 Specification

In order to estimate the effects of a firm’s size on its productivity, we start with the following reduced form baseline specification (Eq. 1):

The dependent variable is the total factor productivity of a firm I, in industry j and period t. The calculation of total factor productivity using the traditional method of ordinary least square may suffer from simultaneity bias. For example, with a positive shock to productivity, the use of inputs also increases. The residual will therefore be a biased estimate of productivity.

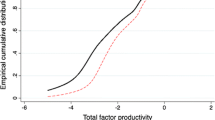

To overcome this simultaneity issue, Levinsohn and Petrin (2003) use intermediate inputs as instruments to control for the correlation between input levels and unobserved productivity shocks. Conditional on capital, profit-maximizing behavior leads more productive firms to use more intermediate inputs. We use the Levinsohn–Petrin estimation as the main measure of TFP in this paper.

Wooldridge (2009) shows how proxy variables used for controlling unobserved productivity can be implemented by using the generalized method of moments estimation.Footnote 6 We use Wooldridge’s modification of the Levinsohn–Petrin method as another measure for TFP for our robustness check.Footnote 7

As discussed above, SMALL is a binary variable that is equal to unity if the relevant firm belongs to the smallest asset class in its industry and zero otherwise. \( \beta_{s} \) is our coefficient of interest. The rest of the control variables in Eq. (1) have been chosen to ameliorate the omitted variable bias. The choice of variables is driven mostly by either previous literature or theoretical prediction. A firm importing from other countries is likely to gain in terms of productivity. This gain can be in terms of quality embodied in the imported goods or by the learning-by-doing phenomenon. Moreover, this gain in productivity would be more pronounced if the firm imports intermediate goods or capital goods. The imports variable is defined as total imports as a percentage of sales. Total imports include imports of raw material, finished goods, spares and capital goods.

To be able to export, a firm needs to invest in developing a product that not only caters to the international market but is also better than those produced by other firms world-wide. This encourages the firm to invest in product development activities and improve the quality of the product or improve the production process. Both Melitz (2003) and Bernard et al. (2003) explain the phenomenon of how exporting firms are more productive than the non-exporting ones. Exports are also estimated as percentage of sales in our estimation.

Being part of a business group has important externalities for a firm. Loosely defined, a business group or business house is a conglomerate with a number of nominally independent firms under its umbrella such that the firms have unique identities but operate under a common administrative or financial management. Most of these business houses are family-owned. Business houses provide institutional infrastructure to the firms under its umbrella. The advantages of belonging to a business house ranges from being able to get low cost internal funds to business reputation and government ties. The concentrated ownership could provide long-term perspective on R&D investment (Claessens et al. 2000). It is therefore reasonable to assume that ownership by a business house could influence a firm’s productivity. The business- house ownership variable is an indicator variable that takes unit value if the firm belongs to a business house and zero otherwise.

Type of ownership (government, foreign, private) can also have important implications for productivity. This is particularly true for India between 1994 and 2008 as various economic reform measures and its effects were spreading across industries. While privatization shifted ownership from government to private entities, liberalization of foreign investment policies implied greater ownership by foreign firms. There is a body of work on the effects of ownership—both government versus private and domestic versus foreign. In what follows, we will estimate various versions of this baseline specification.

6.2 Relationship between size, productivity and firm capabilities

There is a body of research on the link between firm size and the various aspects of research and development. Firm size has been linked either to the investment in R&D (in terms of patent-to-expenditure ratio; Acs and Audretsch 1990; Bound et al. 1982; Cohen and Klepper 1996; Hausman et al. 1984; Kim et al. 2009; Syrneonidis 1996) or to the magnitude of investment (Acs and Audretsch 1987; Bound et al. 1982; Scherer 1986). A natural extension to this literature is to examine if size-productivity relationship is mediated by R&D expenditure of a firm.Footnote 8

Apart from R&D, other firm capabilities, such as human capital, technology gap and development expenditure of the industry, play important roles in productivity determination (Blalock and Gertler 2009). We focus on a variable that is particularly relevant in the context of developing countries like India. We test a firm’s cash flow proxying for liquidity, as a predictor of productivity. This strategy is motivated by the recent dual-evidence that firms are credit-constrained, and that credit constraint influences firm performance and investment decisions (Nagaraj 2012). In an environment characterized by imperfect credit markets, small firms suffer from liquidity constraints because of the lack of political clout and economic collateral that they can offer. Cash flow has been defined as cash in hand (including bank balance) as a proportion of the firm size measured by total assets. We estimate a modified Eq. (1) that includes cash flow, R&D and their interaction with size respectively.

6.3 Identification and endogeneity concerns

Equation (1) captures the relationship between (small) size and total productivity. For identification of the causal effect of smallness, we rely on the random effects specification. For observational data, the choice of specification between fixed and random effects is complicated by the fact that both random effects specification (which assumes that firm-specific unobserved heterogeneities λ I are uncorrelated with time-invariant firm-specific unobserved variables) and fixed-effects specification (that assumes that those two are correlated) have advantages and drawbacks. Fixed-effects models are particularly unsuitable for the situations where the main explanatory variable of interest does not change over time. Since SMALL is our main variable of interest, we need variations in the values of SMALL to identify its relationship with productivity using fixed effects estimators. Our choice is also bolstered by the fact that we have a rich dataset and can control for a large number of firm-characteristics that the extant literature specifies, alleviating the concerns of omitted variables to a large extent. Additionally, we have controlled for time fixed effects to capture the effects of any overall economy-wide changes in policy, and industry fixed effects to capture industry-specific unobserved characteristics.

There are still concerns with reverse causality—how do we know that size determines productivity and not the other way around? If this is the case, we will see that productive firms would grow in size. However, In India, one of the peculiar characteristics of the manufacturing sector is that there is very little size mobility over time. This is true in our sample and is also found out independently by other researchers. In our sample, inter-asset size mobility is limited—only 5 % of the firms move up in the size ladder within a year and 7 % do in a window of 2 years. Hsieh and Klenow (2012) have also recently documented how surviving Indian plants exhibit little growth in terms of either employment or output. Therefore, higher TFP firms do not necessarily grow in size. This is a recent and active area of research and the present paper is not about growth of firms, but this pattern ameliorates the endogeneity concern. To show it empirically, we estimate the following model:

Does getting productivity shock in period t lead to a movement from the lowest quintile to the higher ones? We investigate how TFP can potentially drive mobility in a regression framework. Table 9 shows results of the regression of the upward mobility of a firm on the lagged values of TFP along with other potentially influencing variables such as age (older firms may have a higher tendency of moving up), liquidity and profits. Here upward mobility is a binary variable which is equal to unity if a firm has moved from quintile 1 to a higher quintile and zero otherwise. The first column shows us how two period lagged TFPs affect firm mobility. From the t statistics and the corresponding p values, we can see that TFP is not a significant predictor of firm mobility. The second column introduces more control variables. In this specification also, TFP does not turn out to be a significant predictor of firm mobility.

Finally, the dynamic estimator that we use below provides additional checks for tests for the robustness of our main results in the presence of potential endogeneity. Endogeneity might arise due to the time-dependency of TFP (Syverson 2011). Hence we also consider dynamic models developed by Arellano and Bond (1991), Arellano and Bover (1995) and Blundell and Bond (1998), referred to as ABB henceforth. These models further improve upon our specification in the following ways. First, in the absence of exogenous instruments, ABB estimators use lagged values of the control variables as instruments. This treats the endogenous variables as pre-determined and, therefore, not correlated with the error term in Eq. (1). Second, the first-differenced GMM estimator naturally removes time-invariant firm characteristics, thus preserving the benefits of using a fixed effects model. Moreover, if TFP is indeed correlated with its past values, then the static model produces inconsistent estimates because the regressor(s) will be mechanically correlated with the error term. ABB-style system GMM controls for this by using past values as instruments. Finally, as Roodman (2006) notes, for a short time (T), long units (N) panel, there is less likelihood that correlation of the lagged dependent variable with the error term will decline over time to be rendered eventually insignificant. ABB estimators are particularly relevant for these cases.

7 Main results

7.1 Firm sizes and total factor productivity

Table 2 summarizes the main results of the paper. The columns of Table 2 present results from the estimation of four variations of Eq. (1). We start from estimating the simplest relationship between size and productivity with no controls [column (1)]. We see that there is a strong positive correlation between belonging to the lowest asset quintile and productivity. The smallest firms are 7 % more productive than their larger counterparts.

Column (2) introduces year and industry fixed effects to control for unobserved industry and time variability. Interestingly, the coefficient estimate standard errors remain almost unchanged. This shows that the relationship is strong across industries and over time. Columns (3) and (4) present results from the random effects (generalized least square) models having included the control variables. Column (4) includes industry dummies; column (3) does not. For both these columns, we see that being small means more productive and significantly so. Coefficient estimates go down slightly when we introduce controls to our estimation. These results are obtained after controlling for a large number of firm characteristics such as government versus private versus foreign ownership, import and export behavior, research and development expenditure and liquidity.

7.2 Firm characteristics and productivity

Table 3 examines which variables are potentially responsible for driving productivity for small firms. The three columns report results from random effects estimation of Eq. (1). Column (1) shows the effect of size interacted with a measure of research and development expenditure. The positive and significant coefficient provides evidence that small firms that invest more in R&D are more productive. The second column reports results from specification where firm size is interacted with a measure of liquidity, cash-in-hand, and shows that small firms with lower liquidity constraints are more productive. Finally, the third column controls for both and shows that both liquidity and R&D are important drivers of productivity for small firms.

The summary message from Table 3 is that being small may have advantages in terms of leaner and more agile management and more flexible operation, but it is also important to invest in research and be able to maintain enough liquidity to be productive. As we will see later, liquidity is an important variable in determining firm survival and exit too.

7.3 Robustness checks

This section checks the robustness of our key results reported in Table 2. We use an alternative definition of TFP, alternative measures of size, both categorical and continuous, and with a different sample.Footnote 9

7.3.1 Dynamic estimation

To exploit the longitudinal data, we dynamize this model by including the lagged dependent variable on the right hand side and by using the lagged values of exports and R&D as instruments of themselves as proposed in Arellano and Bond (1991), and Arellano and Bover (1995) and applied in TFP estimation by Fernandes (2003) and Khandelwal and Topalova (2010), among others.

One of the channels through which endogeneity problems may affect our estimators is the time-dependency of TFP (Syverson 2011). Therefore, we also consider dynamic models developed by Arellano and Bond (1991), Arellano and Bover (1995) and Blundell and Bond (1998). As discussed in Sect. 6.3, the dynamic model ameliorates endogeneity concerns in our estimation.

As column (5) of Table 2 shows, the dynamic model gives us the best fit. All regressors are significant. The first and second lags of the dependent variable TFP are significant and less than unity. Even in this case, small firms turn out to be significantly more productive, though both coefficient estimate and standard errors are less in the case of the dynamic model.

7.3.2 Results with an alternative definition of TFP

Despite its widespread use, the Levinsohn–Petrin method of TFP estimation has been criticized as being inappropriate under certain conditions, notably by Ackerberg et al. (2006), who argue that total factor productivity may not be identified separately from the labor productivity as the former is a deterministic function of the latter. Wooldridge (2009) gets around this problem by proposing a GMM method that uses multiple lags, yielding multiple moment conditions for identification. He goes on to show that even if labor were a deterministic function of productivity, one can still identify and estimate productivity.

Results using TFP estimates derived from the Wooldridge method are presented in Table 4. Only specifications from Table 2 have been used, as they are our main results. From row 1, we can see that using an alternative definition of TFP does not change our core results. Small firms are still significantly more productive than their counterparts.

7.3.3 Results with all five size categories

In this section we use all five size categories with the smallest size as base category. This specification allows us to see whether all larger categories are more productive than the smallest category, or if there is some discontinuity in that relationship.

Rows 1–4 of Table 5 repeat the key results of row 1 in Table 2, controlling for the same variables. From the sign and significance pattern of the coefficients of all the other size categories, we see that firms belonging to all four categories of firms larger than the smallest category are (statistically) significantly less productive than the smallest category, the base category in this specification. To recall, this base category is the same as our SMALL category in the previous specification. Therefore, the message from this table is that bigger firms are significantly less productive irrespective of how much bigger the firm is relative to the smallest size. This test provides a more transparent picture of the nature of size-productivity relationship than that reported in Sect. 7.2 above.

7.3.4 Results with balanced panel

Table 2 reports estimation results of Eq. (1) with an unbalanced panel of firms allowing for entry and exit of firms. Firms enter and leave industries all the time. However, as discussed in the earlier section, some exit behavior may bias the sample towards firms with higher productivity. Therefore, we restrict the sample to firms that stayed on throughout the sample period of 1994–2007 to form a balanced panel of firms. The results from estimating the same set of models (except for the single-regressor regressions to avoid clutter) are presented in Table 6.

Except for the first two columns, Table 6 is organized in the same way as Table 2. Evidence in this table also confirms our earlier results from an unbalanced panel of firms that small firms are significantly more productive than their larger counterparts. The sign and significance pattern of the other control variables confirm that entry and exit of firms do not seem to affect the results in any particular way.

7.3.5 Results with a continuous measure of size

Even though size of an enterprise is defined in terms of assets in India, it will be interesting to investigate how other measures of size are related to productivity. One such measure is market share—share of a firm’s sales within the industry to which it belongs. Therefore, instead of a binary variable as SMALL, we now have a continuous variable market share in Eq. (1). The rest of the equation is left unchanged. Results from the estimation of this modified equation are presented in Table 7.

Row (1) in Table 7 summarizes the main results for the coefficient of interest here. Market share has a negative and significant impact across all specifications. This is in line with the previous results with asset size. Since smaller firms are likely to have lower market share, the positive small-size high-TFP relationship is likely to translate to negative market share—productivity relationship.Footnote 10

8 Caveats, conclusions and policy implications

In this paper, we have used firm level panel data to estimate the differences in the productivity of large and small firms in the manufacturing sector in India. Such exercise has been motivated by several stylized, theoretical, empirical and policy observations. Firm size heterogeneity is widespread among developing countries. Mammoth firms coexist with smaller firms and continue to produce similar products. However, theoretically both small and large firms have productivity advantages and disadvantages such as scale economies versus smaller and more flexible management structure. Empirical evidence from the US and the rest of the world has been piecemeal and mixed. Finally, several countries including India have been pursuing policies to promote small and medium enterprises. With the availability of new firm-level micro data, new evaluation of the size-productivity relationship contributes to both researchers’ and policymakers’ understanding of the implications of firm size heterogeneity for productivity and growth of the economy. We have calculated total factor productivity by using both the Levinsohn–Petrin method and its modification proposed by Wooldridge to control for simultaneity between input choice and productivity shocks. In estimating our main results, we use a variety of specifications. Our results are also robust to a variety of alternative definitions. Finally, we investigated if firm size mobility is driven by lagged productivity and found no evidence of such behavior.

There are some limitations in the data that will affect the interpretation of our results. First, we do not have a measure of the human capital of a firm in terms of education and training of its employees. Therefore, the measure of capital solely represents physical capital. Though such information can be found in census-based surveys, such surveys have other issues of misreporting that a balance sheet-based database does not.

Second, we cannot provide a complete analysis of exit (and entry). It has been noted elsewhere also that the PROWESS database does not allow tracking entering and exiting firms with precision. We can only define exit if a firm disappears from the dataset. However, firms may drop out from our database for a variety of reasons. It may become so small that it may not have to report; it may adopt a different name, may shift into informality or may actually shut down.

Similarly, firms may exit and reappear in the database not because they closed down and reopened again, but simply because they resumed reporting their balance sheet results (and PROWESS database records them again). However, there is no evidence of this discrepancy in our sample. The main problem exit behavior creates is that in retrospect, we may have a selected sample—only the firms that are more efficient survive and if most of the entrant firms are small, which is a reasonable assumption, then our results will be biased upward because we are looking at the more efficient firms selectively. This problem is present in survey-based measures too. To tackle this problem, we look at the exit behavior of firms. The results are reported in Table 8.

The main question here is whether lower-productivity firms are more likely to exit. That is, we examine the effects of lagged productivity on the binary variable EXIT that equals unity when a firm ceases to exist in a particular year conditional on the fact that it was in operation in the previous year. We also control for other plausible explanations such as size, age, age-squared, net profit, cash flow and leverage, the last two variables being the proportion of cash in hand and short-term debt to total assets, respectively. Columns (1) and (2) report estimated results from the linear probability model and probit model, respectively.

Table 8 shows us that TFP is not a driving force behind firm exit. However, small firms do exit at a higher rate, which is consistent with findings in the literature. Similarly, older firms tend to exit less, another common finding in the literature. However, firms fail to survive because of their low cash balance. Capital market in India, despite the recent liberalization, is still relatively underdeveloped. Firms that generate enough cash flow and earn and reinvest profit survive in their respective industries. Hence, we fail to find evidence that positive productivity-based selection is driving our results (Table 9).

Subject to these caveats, our findings provide support for policies that aim at encouraging small firms. However, this does not mean that large firms need to be broken up or firm growth should be stifled or firms should be stopped from being merged or acquired. A paradoxical result that remains to be explored in future studies is this—despite the productivity advantage, firm growth is largely absent. The answer may lie in various institutional details such as availability of government subsidies and incentives being limited to only smaller firms and lack of quality workers and difficulty of expanding in size in an unfriendly regulatory environment. Small firms may not necessarily have to grow; more small firms may thrive in the industry, raising overall productivity.

Notes

Though it is more usual to estimate productivity at the plant level, firm-level productivity is more appropriate in our context as size-restriction is imposed at the firm-level and not the plant-level. Admittedly, they are not identical as a firm may have several plants, and as Winter (1999) shows firm financials may affect plant productivity. Using balance sheet data is a more modern trend, partly because of availability of such databases. One example is Khandelwal and Topalova (2010), who use the same database to estimate TFP.

The unorganized sector accounts for about 45 % of the employment in the manufacturing sector and contributes to about 44 % of the GDP as estimated by the Central Statistical Organisation, India. The data we use does include firms which are not publicly traded. A detail discussion of the informal manufacturing sector in India is beyond the scope of this paper.

Source: Development Commission (SSI), Third Census, Government of India.

Morris and Basant (2006) present a detailed discussion of the financial constraints faced by small firms in India.

We use one more source of data for robustness checks. There is some evidence that large firms pay higher wages (Idson and Oi [1999], Brown and Medoff [1989]). If this is systematically the case, then our calculation of labor is biased, as we use an industry-wide deflator. This will underestimate the TFP of larger firms affecting our regression results. Since firm-level wage data is missing for a large majority of firms, we cannot deal with this directly as it will lead to a drastic loss of sample size. Therefore, we deal with this in a couple of indirect ways. First, we see if, given the limited data, there is any evidence that large firms systematically pay more. We do not find such evidence. We next look at a roughly comparable database on the Indian manufacturing sector, the Annual Survey of Industries, and estimate the average wage premium between small and large firms (Chamarbagwala and Sharma [2012]). The average wage rate of firms in the fifth quintile is approximately three times that in the first quintile. That is, large firms pay almost three times the wage an average small firm pays. We recalibrate our wages to account for this wage premium and then recalculate labor and TFP. On estimating our various specifications, we find that the small firms still have significantly higher TFP than the larger firms, though the coefficients become smaller. The details of these exercises are available upon request.

Please refer to Van Beveren (2012) for a detailed discussion on the various measures of TFP.

For brevity, we exclude the details of TFP estimations. The authors will be happy to make them available upon request.

We also use a more popular definition of size, as discussed above—size by quintiles of employment. As mentioned in the data section, we do not have data on employment and impute the same by dividing the wage bill by average wage rate. The imputed employment is then divided into quintiles by year and by industry. We once again find a positive and significant relation between being small by this definition and being productive. However, as this imputation of labor is an imprecise method of measuring employment, we relegate it to the “Appendix”.

We obtain similar results when we define size in terms of quintiles of market share instead of assets. This is expected, as asset-based measure of size and sales-based measure of size are likely to be very similar. These results are available upon request from the authors.

References

Ackerberg, D. A., Caves, K., & Frazer, G. (2006). Structural identification of production functions. Los Angeles: UCLA Department of Economics.

Acs, Z. J., & Audretsch, D. B. (1987). Innovation, market structure, and firm size. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 69(4), 567–574.

Acs, Z. J., & Audretsch, D. B. (1990). Innovation and small firms. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Arellano, M., & Bond, S. (1991). Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. The Review of Economic Studies, 58(2), 277–297.

Arellano, M., & Bover, O. (1995). Another look at the instrumental variable estimation of error-components models. Journal of Econometrics, 68(1), 29–51.

Aw, B. Y. (2002). Productivity dynamics of small and medium enterprises in Taiwan. Small Business Economics, 18(1), 69–84.

Aw, B. Y., Chen, X., & Roberts, M. J. (2001). Firm-level evidence on productivity differentials and turnover in Taiwanese manufacturing. Journal of Development Economics, 66(1), 51–86.

Baily, M. N., Bartelsman, E. J., & Haltiwanger, J. (1996). Downsizing and productivity growth: Myth or reality? Small Business Economics, 8(4), 259–278.

Beck, T., Demirgüç-Kunt, A., & Maksimovic, V. (2005). Financial and legal constraints to growth: Does firm size matter? The Journal of Finance, 60(1), 137–177.

Bernard, A. B., Eaton, J., Jensen, J. B., & Kortum, S. (2003). Plants and productivity in international trade. The American Economic Review, 93(4), 1268–1290.

Bigsten, A., & Gebreeyesus, M. (2007). The small, the young, and the productive: Determinants of manufacturing firm growth in Ethiopia. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 55, 813–840.

Blalock, G., & Gertler, P. J. (2009). How firm capabilities affect who benefits from foreign technology. Journal of Development Economics, 90(2), 192–199.

Blundell, R., & Bond, S. (1998). Initial conditions and moment restrictions in dynamic panel data models. Journal of Econometrics, 87(1), 115–143.

Bound, J., Cummins, C., Griliches, Z., Hall, B. H., & Jaffe, A. B. (1982). Who does R&D and who patents? NBER working paper.Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Brown, C., & Medoff, J. (1989). The employer size-wage effect. The Journal of Political Economy, 97(5), 1027–1059.

Chamarbagwala, R., & Sharma, G. (2011). Industrial de-licensing, trade liberalization, and skill upgrading in India. Journal of Development Economics, 96(2), 314–336.

Claessens, S., Djankov, S., & Lang, L. H. P. (2000). The separation of ownership and control in East Asian corporations. Journal of Financial Economics, 58(1–2), 81–112.

Cohen, W. M., & Klepper, S. (1996). A reprise of size and R and D. The Economic Journal, 106(437), 925–951.

Dhawan, R. (2001). Firm size and productivity differential: Theory and evidence from a panel of US firms. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 44(3), 269–293.

Fernandes, A. M. (2003). Trade policy, trade volumes, and plant-level productivity in Colombian manufacturing industries. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Hall, R. E., & Jones, C. I. (1999). Why do some countries produce so much more output per worker than others? The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 114(1), 83–116.

Hausman, J. A., Hall, B., & Griliches, Z. (1984). Econometric models for count data with an application to the patents-R&D relationship. Econometrica, 52(4), 909–938.

Henderson, R. (1993). Underinvestment and incompetence as responses to radical innovation: Evidence from the photolithographic alignment equipment industry. The Rand Journal of Economics, 24(2), 248–270.

Hsieh, C.-T., & Klenow, P. (2012). The life cycle of plants in India and Mexico. Working paper 18133. UK: DFID.

Idson, T. L., & Oi, W. Y. (1999). Workers are more productive in large firms. American Economic Review, 89(2), 104–108.

Jovanovic, B. (1982). Selection and the evolution of industry. Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society, 50(3), 649–670.

Khandelwal, A., & Topalova, P. (2011). Trade liberalization and firm productivity: The case of India. Review of Economics and Statistics, 93(3), 995–1009.

Kim, J., Lee, S. J., & Marschke, G. (2009). Relation of firm size to R&D productivity. International Journal of Business, 8(1), 7–19.

Klenow, P. J., & Rodriguez-Clare, A. (1997). The neoclassical revival in growth economics: Has it gone too far? In B. Bernanke & G. Rotemberg (Eds.), NBER macroeconomics annual 1997 (pp. 73–102). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Levinsohn, J., & Petrin, A. (2003). Estimating production functions using inputs to control for unobservables. Review of Economic Studies, 70(2), 317–341.

Mazumdar, D. (2009). A comparative study of the size structure of manufacturing in Asian countries. Manila: Asian Development Bank (processed).

Melitz, M. J. (2003). The impact of trade on intra-industry reallocations and aggregate industry productivity. Econometrica, 71(6), 1695–1725.

Ministry of Law and Justice, Government of India. (2006). The Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises Development Act, 2006.

Morris, S., & Basant, R. (2006). Small-scale industries in the age of liberalization, INRM Policy Brief No. 11: Asian Development Bank.

Nagaraj, P. (2012). Essays on firm behavior. Order No. 3525915. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses, 105, City University of New York. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.gc.cuny.edu/login?

Roodman, D. (2006). How to do xtabond2. Paper presented at the North American Stata Users’ Group Meetings 2006, Boston, MA.

Scherer, F. M. (1986). Innovation and growth: Schumpeterian perspectives (Vol. 1). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Shefer, D., & Frenkel, A. (2005). R&D, firm size and innovation: An empirical analysis. Technovation, 25(1), 25–32.

Syrneonidis, G. (1996). Innovation, firm size and market structure: Schumpeterian hypotheses and some new themes. OECD Economic Studies, 27, 35–70.

Syverson, C. (2011). What determines productivity? Journal of Economic Literature, American Economic Association, 49(2), 326–365.

Tybout, J. R. (2000). Manufacturing firms in developing countries: How well do they do, and why? Journal of Economic Literature, 38(1), 11–44.

Van Beveren, I. (2012). Total factor productivity estimation: A practical review. Journal of Economic Surveys, 26(1), 98–128.

Van Biesebroeck, J. (2005). Firm size matters: Growth and productivity growth in African manufacturing. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 53, 545–583.

Williamson, O. E. (1967). Hierarchical control and optimum firm size. The Journal of Political Economy, 75(2), 123–138.

Winter, J. K. (1999). Does firms’ financial status affect plant-level investment and exit decisions? Publications 98-48, University of Mannheim.

Wooldridge, J. M. (2009). On estimating firm-level production functions using proxy variables to control for unobservables. Economics Letters, 104(3), 112–114.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Sangeeta Pratap, Jonathan Conning, Russell Green, and seminar participants at the New York State Economic Association Annual Meeting, The City College of New York and North American Productivity Workshop (NAPW), 2012 for comments and suggestions; and Institute for Study of Industrial Development, New Delhi, India for their support with the data. Gunjan Sharma also gracefully provided data. Support for this project was provided by a PSC-CUNY Award, jointly funded by The Professional Staff Congress and The City University of New York. Priya Nagaraj acknowledges financial support from the Graduate Center, CUNY and NAPW.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: construction of variables from the PROWESS database

Appendix: construction of variables from the PROWESS database

1.1 Output

Output is deflated sales adjusted for change in inventory and purchase of finished goods. In PROWESS, purchase of finished goods is defined as finished goods purchased from other manufacturers purely for resale purpose. It therefore needs to be subtracted from sales to arrive at the firms’ manufactured output. An increase in inventory is added to sales to arrive at output and a decrease subtracted.

1.2 Value added and input

Value added is defined as the difference between output and inputs. The variable input is defined as the sum of material, fuel, packaging and distribution expenses. Value added is used in the calculation of TFP.

1.3 Total factor productivity (TFP)

TFP is calculated by the Levinsohn–Petrin method that uses material as the proxy variable. Both labor and fuel are considered as freely varying inputs. TFP has been calculated using both output and value added as the dependent variable.

1.4 Labor employment

Labor is calculated by dividing the compensation to employees by emoluments per employee. Emoluments per employee are the all industry average emoluments per employee as given by the Central Statistical Organization (CSO). CSO is a part of the Ministry of Statistics and Planning of the Government of India.

1.5 Capital stock

Capital stock has been constructed by adding current period investment to last period’s capital stock net of depreciation. Capital has been depreciated at the rate of 10 %.

1.6 Ownership

PROWESS defines ownership broadly as Government owned (either Central or State), private sector owned, cooperative sector and joint sector. The private sector comprises Indian private sector and foreign private sector. Both Indian and foreign private sector are further divided into Private (Indian/foreign) and Business groups (Indian/foreign). We have combined the last two categories, Indian business groups and foreign business houses into one indicator for ownership by a large business group. The variable takes unit value if the firm is owned by a large Indian business group or by a foreign business house and zero otherwise. The category, foreign business houses, includes NRI business houses like the Hinduja group and the Ispat (Mittal) group. Indicator for Export participation: The indicator for export participation takes the value 1 when value of exports for the year exceeds zero. The value of exports is the sum of exports of goods and services.

1.7 Classification of NIC-2 digit industry

Prowess gives the National Industrial Classification (NIC) of the firms in it dataset. NIC classification is consistent with the ISIC rev.3. The classification in some cases is only two digits while in others it is 5-digits. We have therefore maintained a 2-digit classification. The dataset saves this classification in text format and not as number. As a consequence, some of the classifications are incorrect as the zero is missing. On careful examination of the company name and economic activity I found 19 such codes which were to be preceded by a zero. The NIC codes were then converted to 2-digit.

1.8 Research and development

This refers to the firm’s expenditure on research and development as a proportion of sales. The expenditure on research and development includes expenditure on royalties, technical know how and license fees other than expenses on research and development activities. Fewer small firms, around 9 %, spend on R&D activities as compared to around 63 % of the largest firms (the fifth quintile). However, small firms spend a larger proportion of their sales on research than the largest firms (2.86 % as compared to 1.14 % by the largest).

1.9 Cash flow

Cash flow is total cash in hand plus cash in bank as reported in the balance sheet.

1.10 Classification of industry as manufacturing

PROWESS classifies the firms as manufacturing or non-manufacturing. Careful examination showed five NIC codes which had been wrongly coded as non-manufacturing. We have changed those to manufacturing maintaining conformity to ISIC rev3. There are some firms who purchase more finished goods than sell. The variable purchase of finished goods is greater than sales. These firms have been classified as manufacturing though they seem to be traders. We have classified these as non-manufacturing and therefore they have been removed from the dataset.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

De, P.K., Nagaraj, P. Productivity and firm size in India. Small Bus Econ 42, 891–907 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-013-9504-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-013-9504-x